Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Synthesis of exopolysaccharides with a higher surface area, complex chemical structure, and enriched with different functional groups whose role is to leach from the biotope and supply to the microbial cell with macro and microelements needed in their metabolism;

- Metabolic products of the specific oxidation process carried out by microbial cells and secreted into the microenvironment, including organic acids, alcohols, amino acids, CO2, ammonia, and cyanide;

- Complex enzyme systems related to the detoxification of secondary products formed due to the use of oxygen as a final acceptor of electrons in microbes with aerobic respiration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Copper Slag Samples Collection and Characterisation

2.2. Sulphuric Acid Consumption of Copper Slag and pH-Dependent Leaching of Base Metals

2.3. Microorganisms and Cultivation

2.4. Non-Ferrous Metals Bioleaching from Copper Slag with Spent Medium

2.5. Analyses

3. Results and Discussions

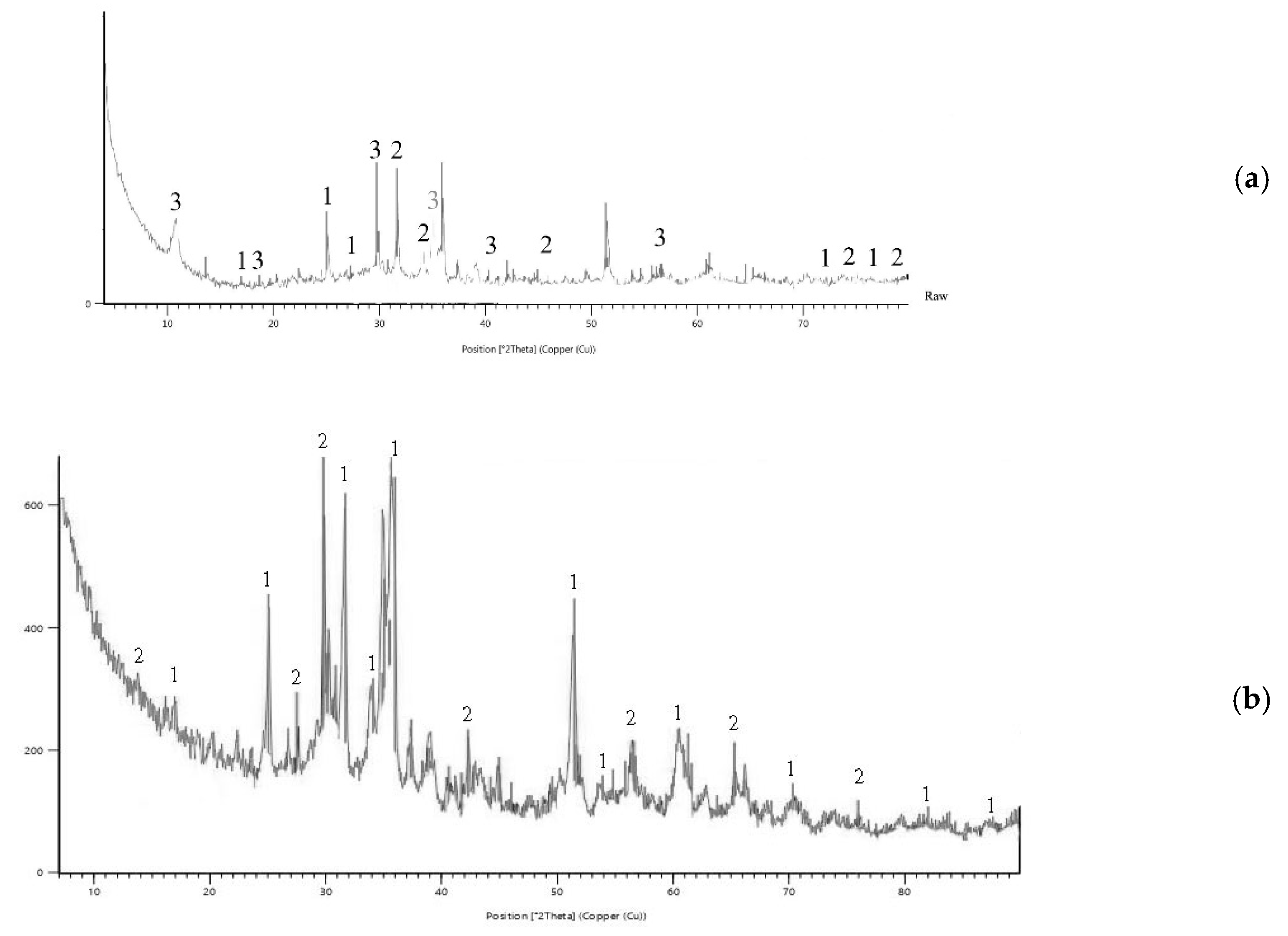

3.1. Chemical Content and Mineralogy

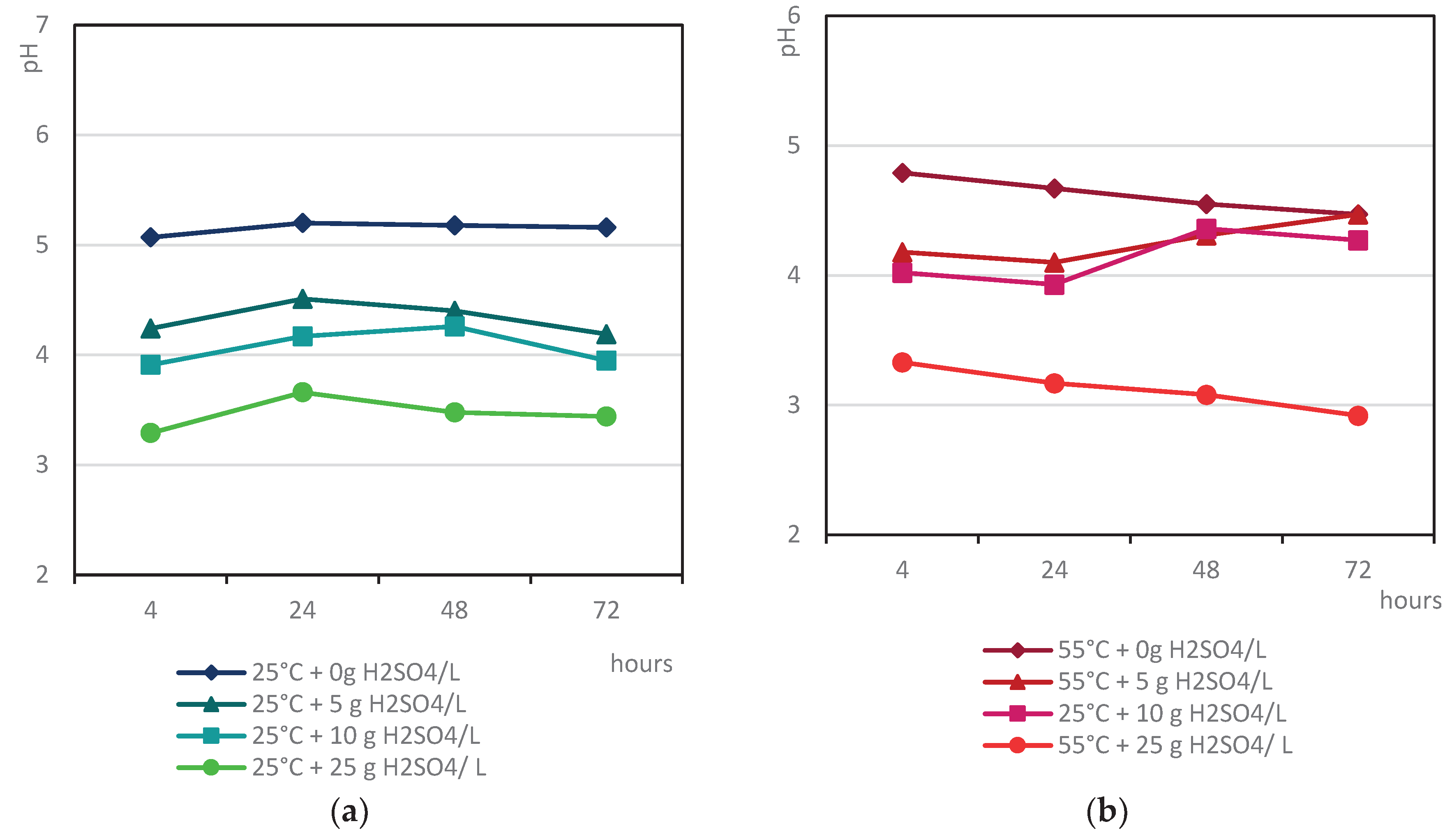

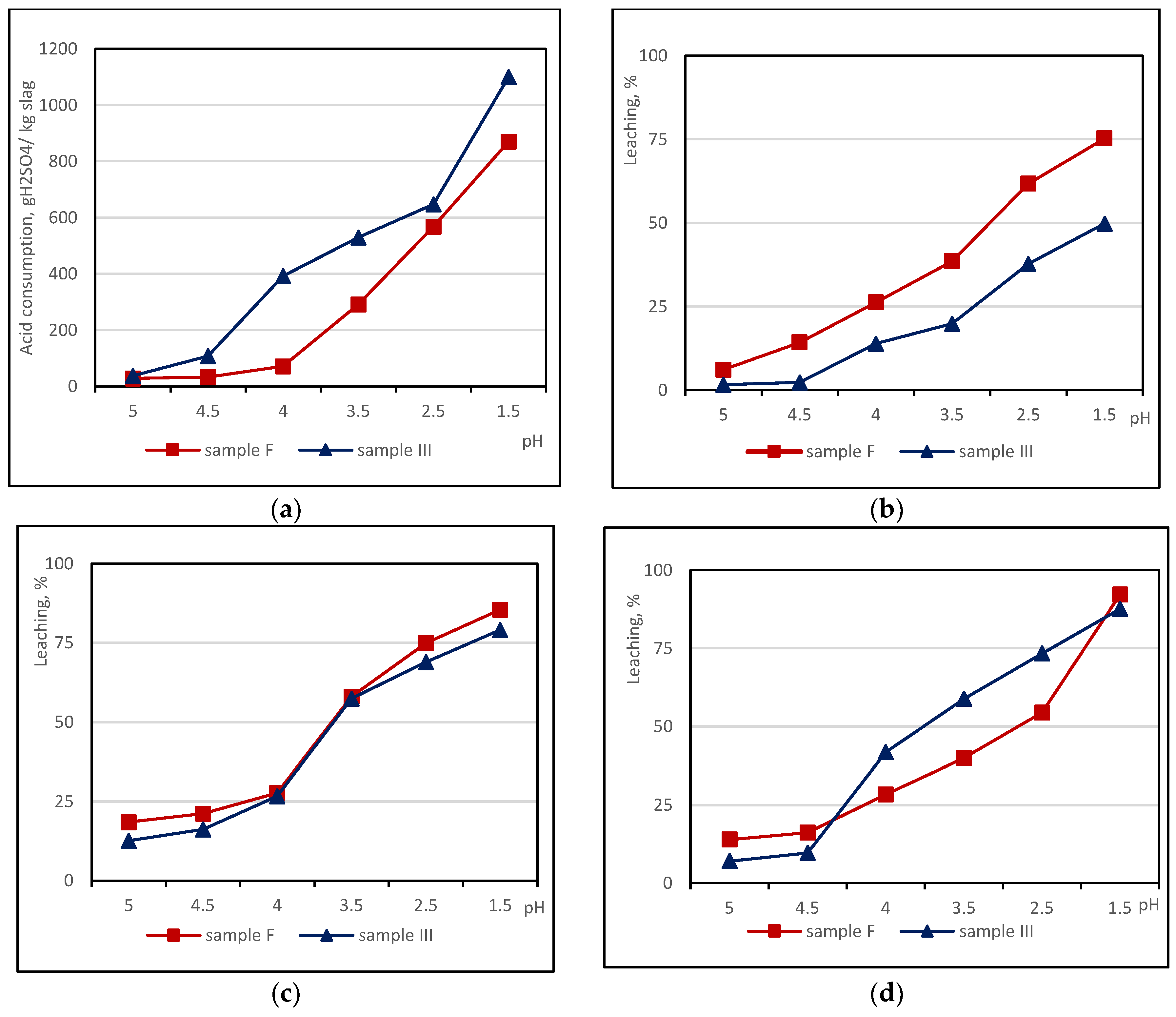

3.2. Sulphuric Acid Consumption and pH-Dependent Leaching of Base Metals from Copper Slags

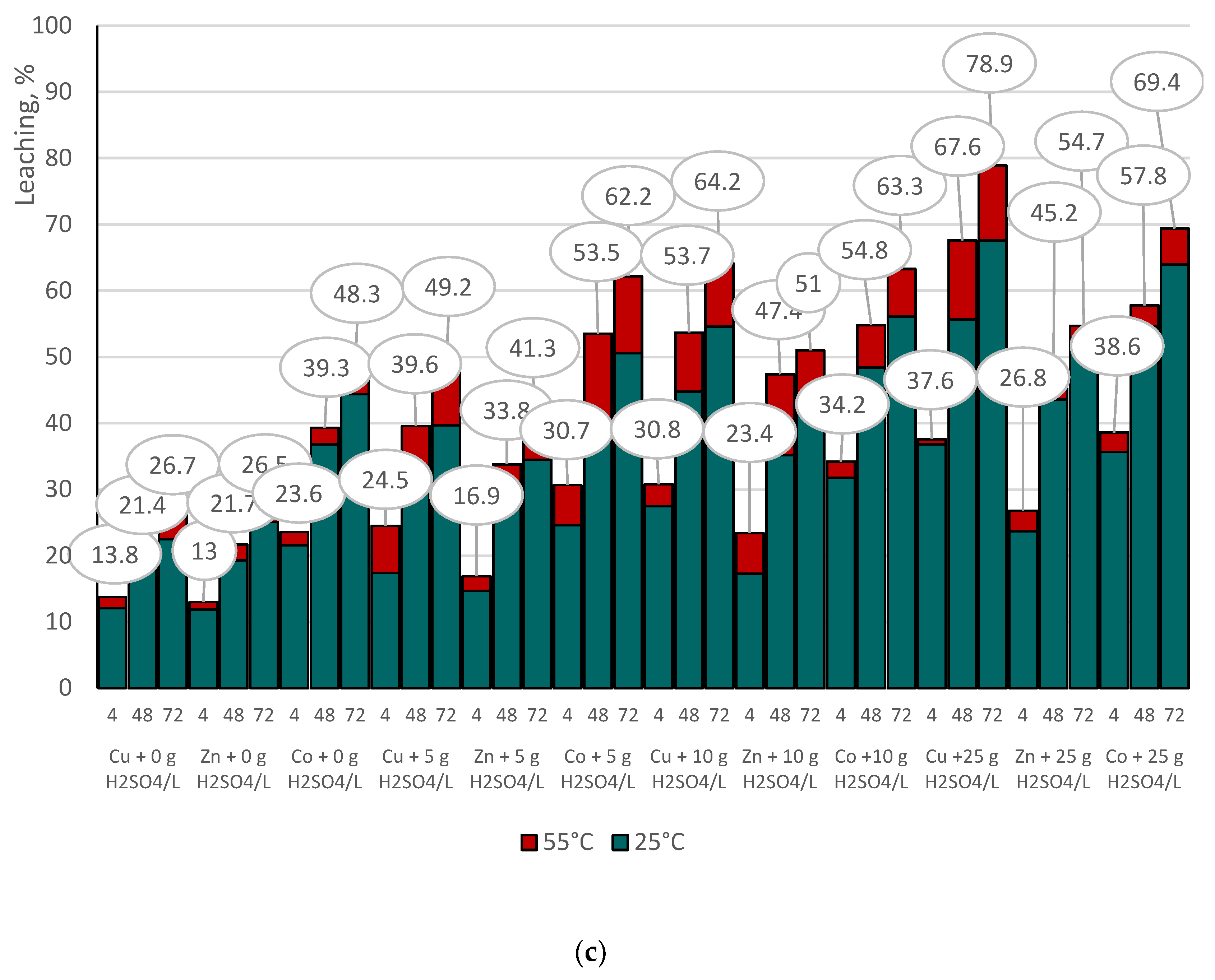

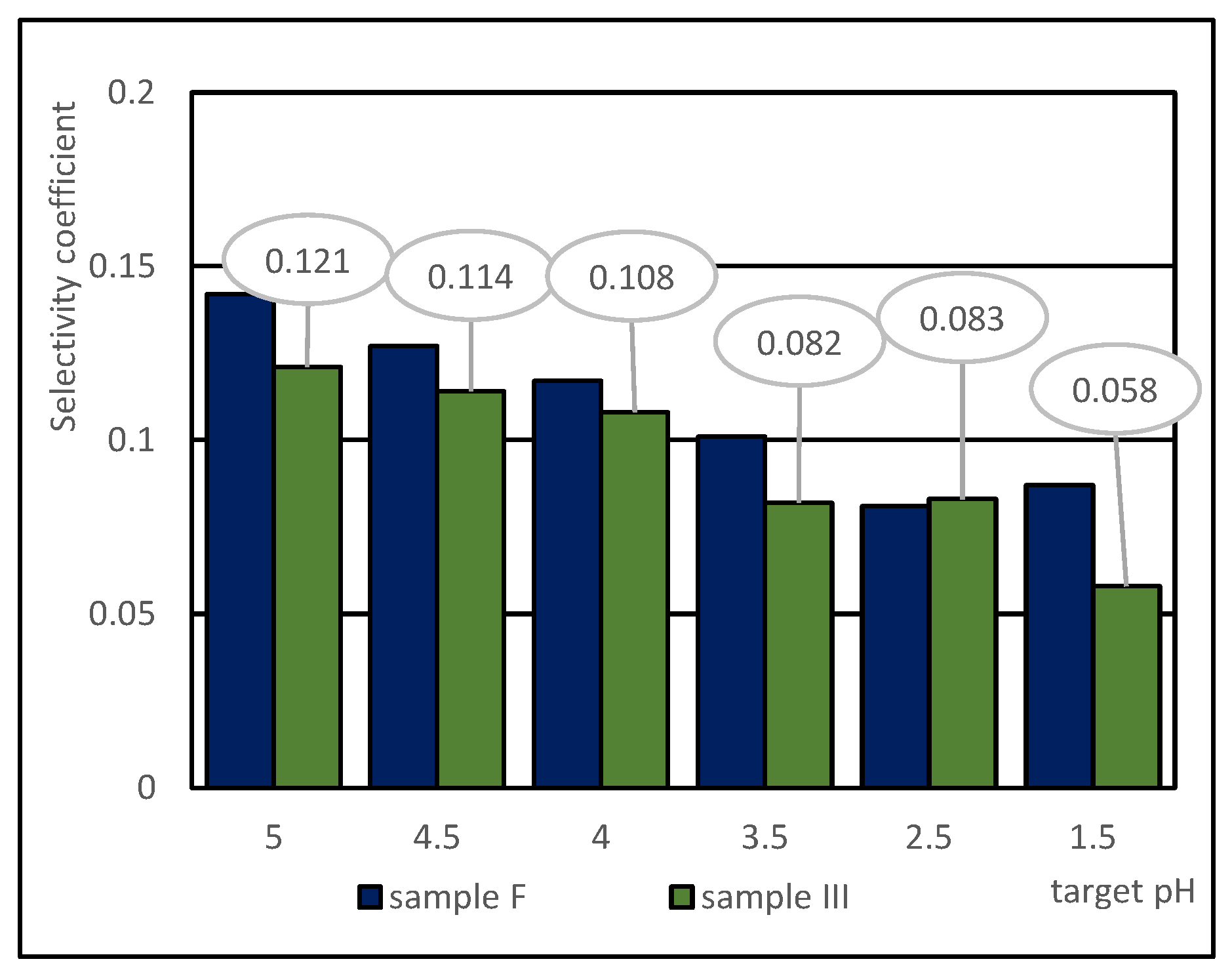

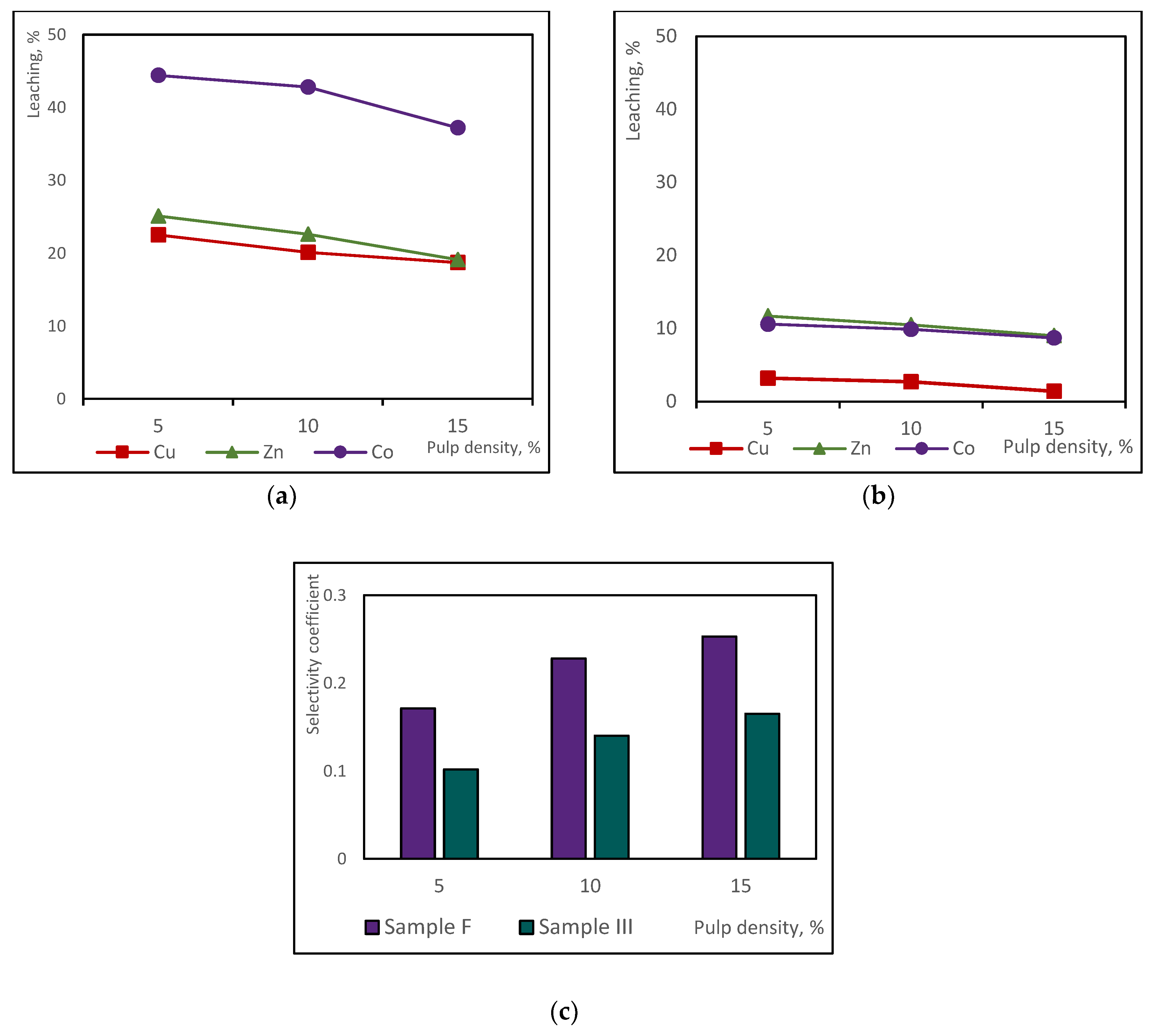

3.3. Selectivity of the Non-Ferrous Metal Chemical Leaching from Copper Slag Using Sulphuric Acid

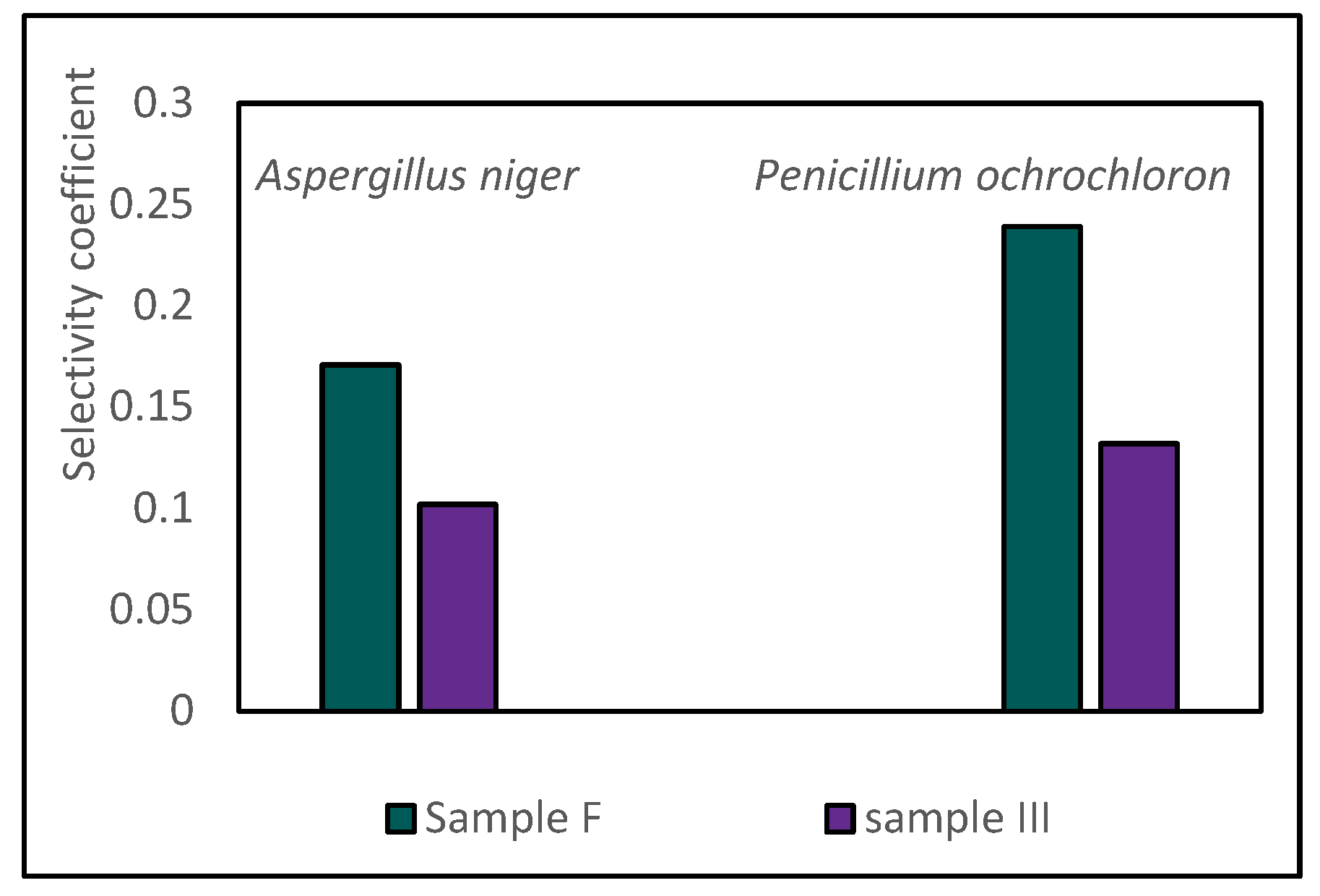

3.4. Indirect Copper Slag Bioleaching with Spent Medium of Aspergillus niger and Penicillium ochrochloron

- Deprotonation of organic acids:(COOH)2 → (C2O4)2- + 2H+

- Proton attack and mineral acidolysis:Fe2SiO4 + 4H+ → 2Fe2+ + H4SiO4

- Formation of complexes between cations and organic anions, which possess different solubilities (complexolysis):Zn2+ + 3C6H707- → Zn(C6H7O7)3-Cu2+ + C2O42- + nH2O→ CuC2O4.nH2O↓

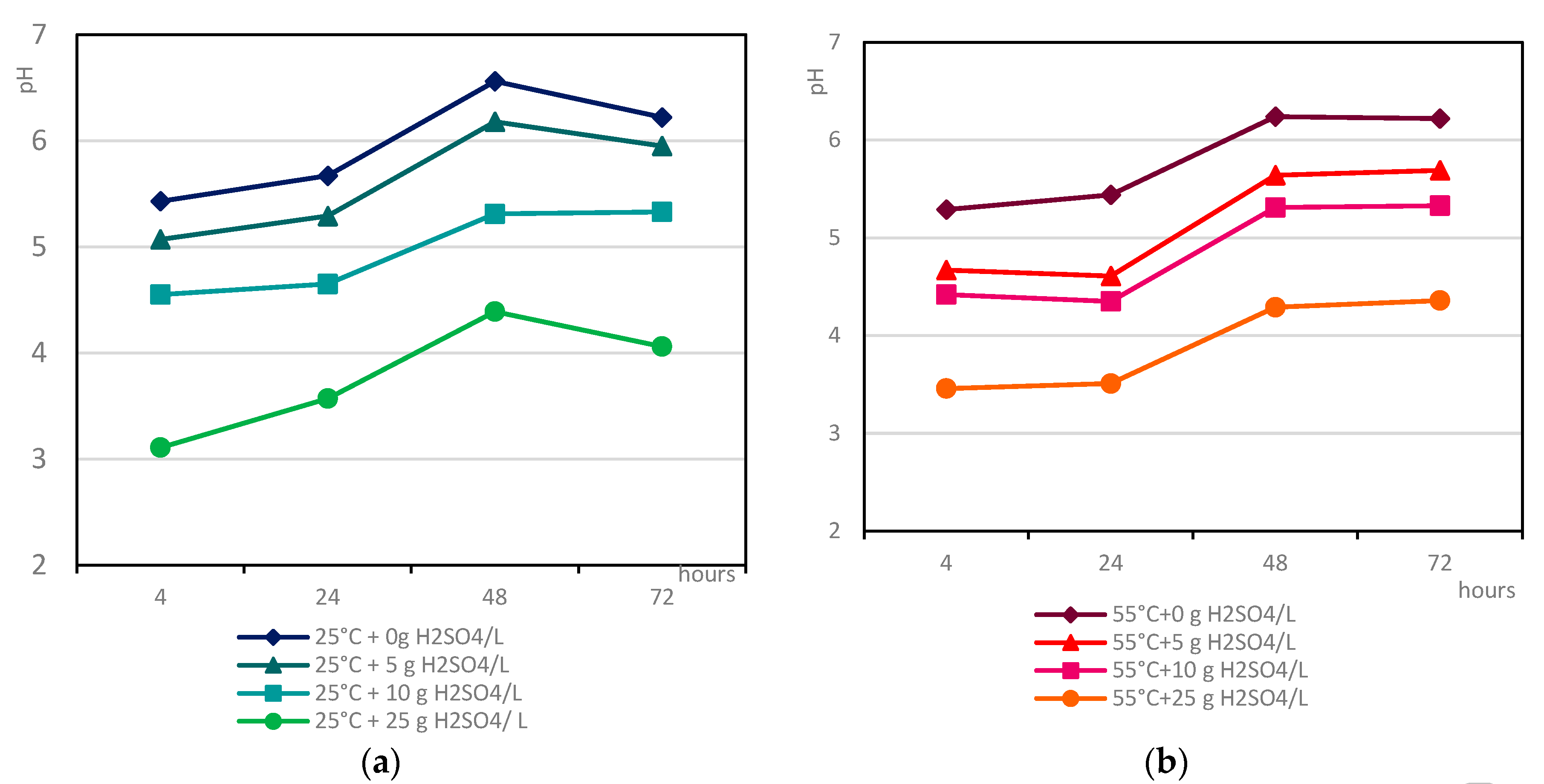

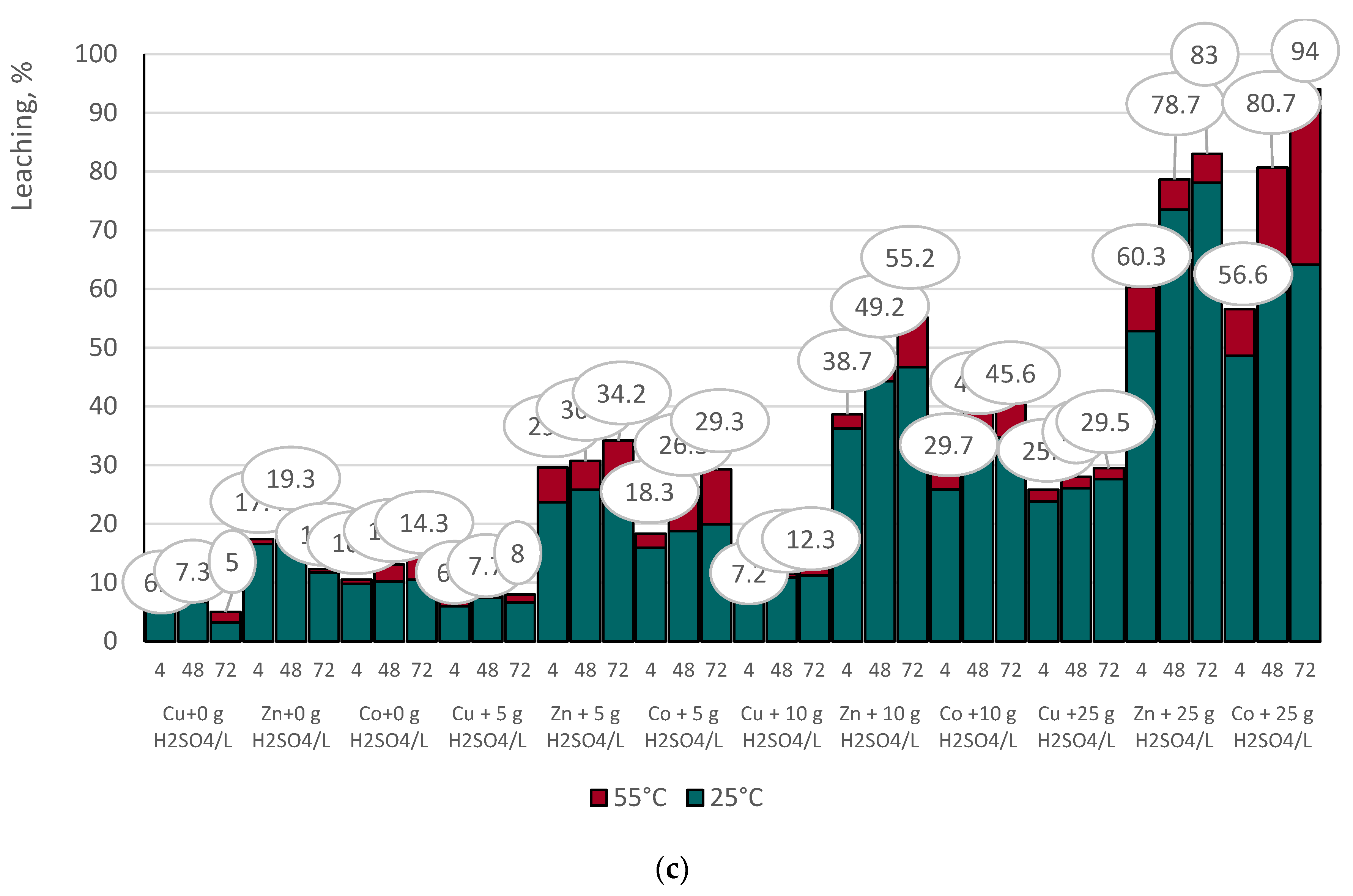

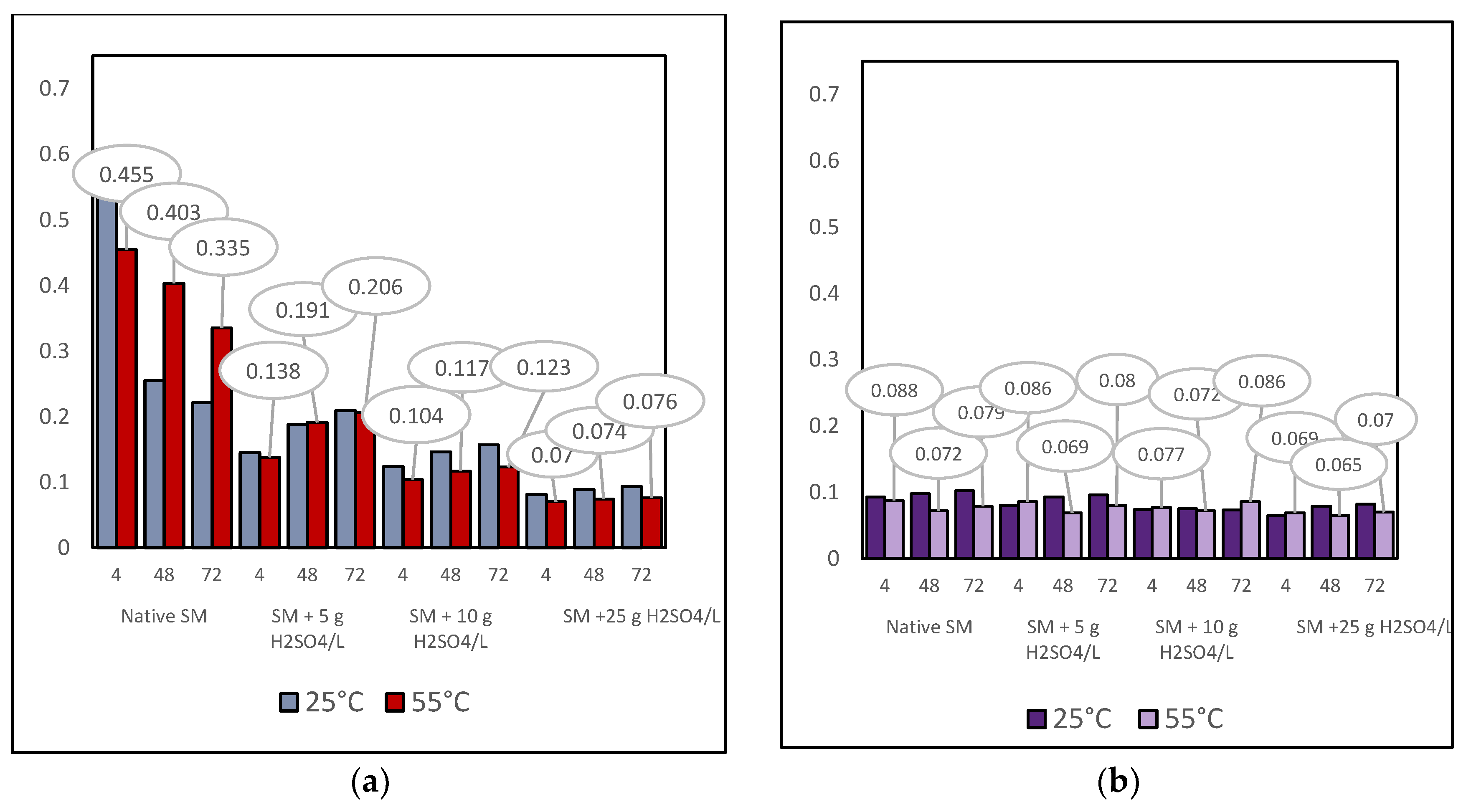

3.4.1. Indirect Copper Slags Bioleaching with Spent Medium of A. niger at 25°C /55 °C and Supplemented with Different Dosages of Sulphuric Acid

- The acidity of the spent medium (native or supplemented with sulphuric acid), but not the temperature, was the main crucial factor that controlled the efficiency of base metal extraction from the studied copper slags;

- The insignificant difference in the selectivity values of base metal extraction at the tested temperatures indicated that copper slag III was more refractory to leaching, considering the extent of base metal extraction from sample F.

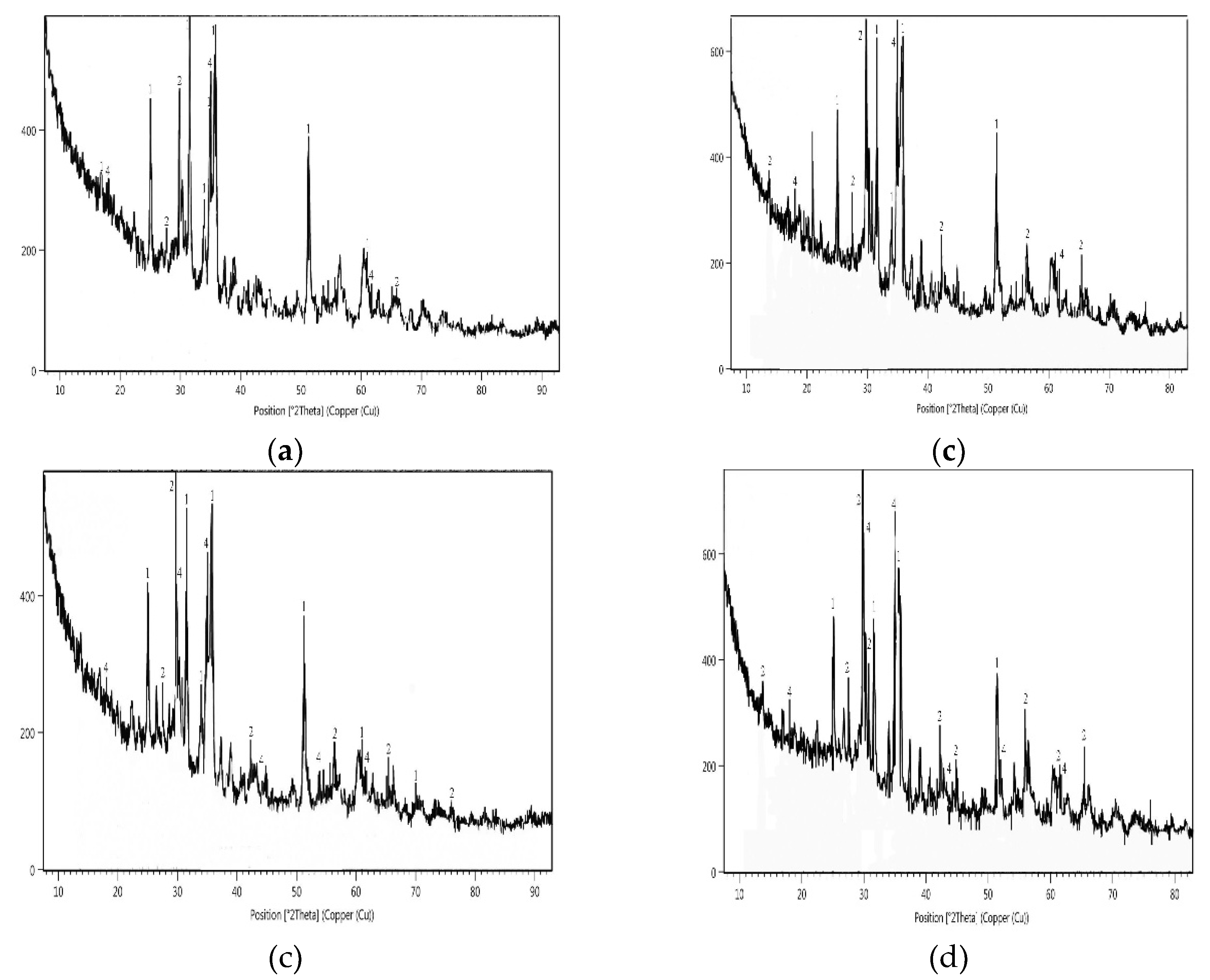

3.5. XRD Diffractograms of Copper Slag Leaching Residues

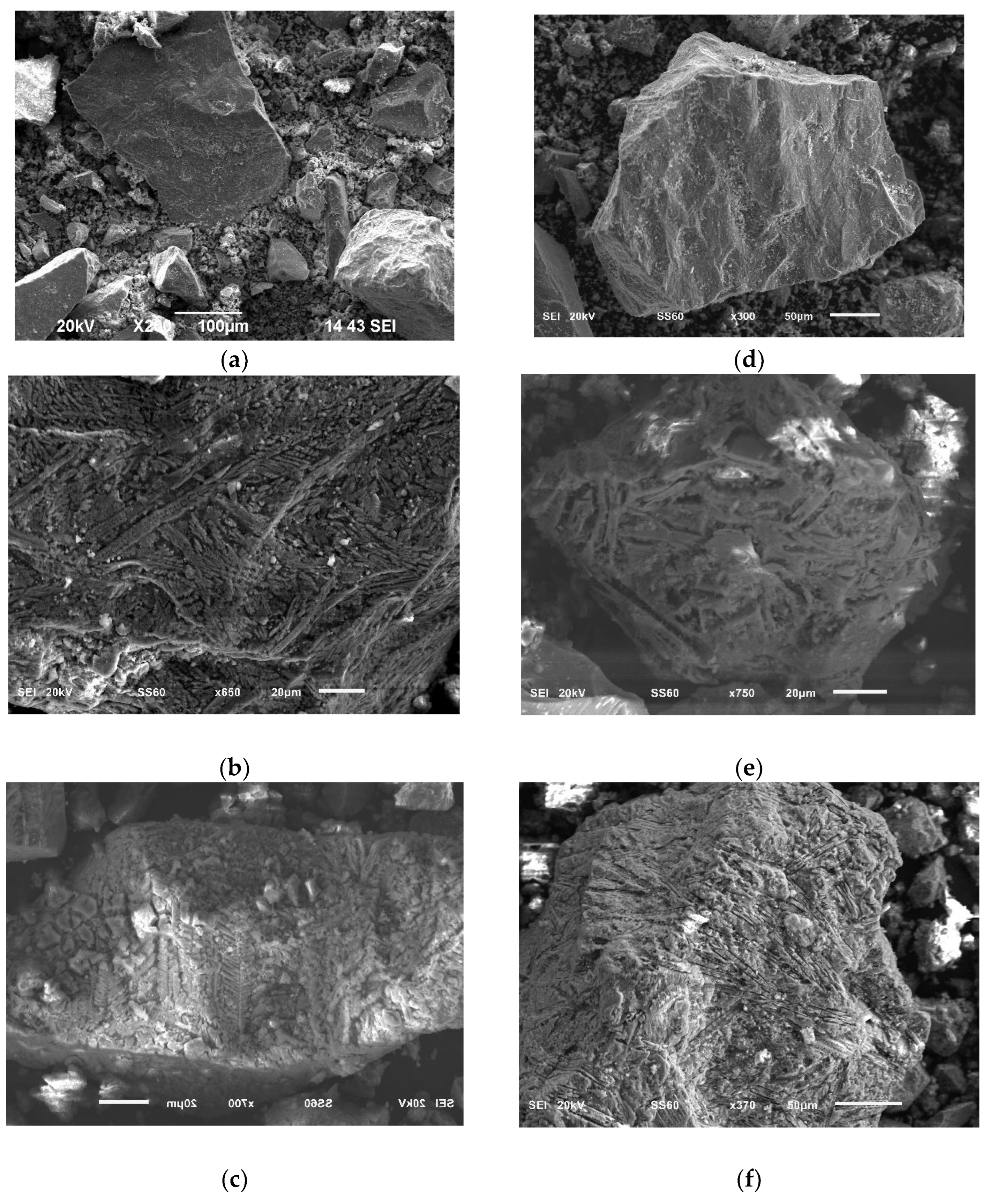

3.6. Morphological Analysis of Copper Slag Leaching Residues

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorai, B., Jana, R.K., Premchand. Characteristics and utilization of copper slag-a review. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling 2003, 39(4), 299-313. [CrossRef]

- Phiri, T., Singh, P, Nikoloski, A.N. The potential for copper slag waste as a resource for a circular economy. A review – part I. Minerals Engineering 2022, 180, 107474. [CrossRef]

- Potysz, A., van Hullebusch, E.D., Kierczak, J., Grybos, M., Lens, P.N.L., Guibaud, G. Copper Metallurgical Slags – Current Knowledge and Fate: A review. Critical Review in Environmental Science and Technology 2015, 45(22), 2424–2488. [CrossRef]

- Piatak, N.M. Environmental characteristics and utilization potential of metallurgical slags. In Environmental Geochemistry, 2nd ed., De Vivo B., Belkin, H.E., Lima, A., Eds., Publisher: Elsevier, 2018, pp. 487-519. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhang, G. Effective separation and recovery of valuable metals from copper slag: A comprehensive review. Environmental Research 2025, 283, 122145. [CrossRef]

- Sethurajan, S., van Hullebusch, E.D., Nancharaih, Y.V. Biotechnology in management and resource recovery from metal bearing solid wastes: Recent advances. Journal of Environmental Management 2018, 211, 138-153. [CrossRef]

- Srichandan, H., Mohapatra, R. K., Parhi, P. K., & Mishra, S. Bioleaching Approach for Extraction of Metal Values from Secondary Solid Wastes: A Critical Review. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 189, 105122. [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, P., Hedrich, S. Biotechnological strategies to recover value from waste. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 222, 106182. [CrossRef]

- He, R., Zhang, S., Zhang, X., Zhang, Z., Zhao, Y., Ding, H. Copper slag: The leaching behavior of heavy metals and its applicability as a supplementary cementitious material. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 105132. [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, P., Das, Wyss, G., Young, C. Recovery of metal values from copper slag and reuse of residual secondary slag. Waste Management 2017, 70, 272-281. [CrossRef]

- Mansourkiyaei, S., Golzary, A. Innovative approaches for circular economy in copper slag management: Maximizing resource efficiency and sustainability. Results in Engineering 2025, 27, 106903. [CrossRef]

- Deng, T., Ling, Y. Processing of copper converter slag for metals reclamation. Part I: Extraction and recovery of copper and cobalt. Waste Manag. Res. 2007, 25(5), 440-448. [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H., Särijärvi, S., Peuraniemi, E., Junnikkala, S., Puhakka, J.A., & Tuovinen, O.H. Metal biorecovery in acid solutions from a copper smelter slag. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 168, 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Pang, L., Wand, D., Wang, H., An, M., Wang, Q. Occurrence and leaching behavior of heavy-metals elements in metallurgical slags. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 330, 127268. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Li, H., Wei, L., Li, C., Sun, S. The Recovery of Copper from Smelting Slag by Flotation Process. In Applications of Process Engineering Principles in Materials Processing, Energy and Environmental Technologies. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series; Wang, S., Free, M., Alam, S., Zhang, M., Taylor, P., Eds., Publisher: Springer, Cham, 2017; pp. 231-237. [CrossRef]

- Kart, E.U., Yazgan, Z.H., Gümüssoy, A. Investigation of iron selectivity behavior of copper smelter slag flotation tailing with hemetitization baking and base metals leaching methods. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Proces 2021, 57(5), 164-175. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrievic, M.D., Urosevic, D.M., Jankovic, Z.D., Milic, S.M. Recovery of copper from smelting slag by sulphation roasting and water leaching. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2016, 52(1), 409-421. [CrossRef]

- Gargul, K. Ammonia leaching of slag from direct-to-blister copper smelting technology. AIMS Materials Science 2020, 7(5), 565-580. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.K., Hamuyuni, J., Agarwal, V., Pihlasalo, J., Haapalainen, M., Lundström, M. Sulphuric acid leaching for capturing value from copper rich converter slag. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 215, 1005-1013. [CrossRef]

- Shi, G., Liao, Y., Su, B., Zhang, Y., Wang, W., Xi, J. Kinetics of copper extraction from copper smelting slag by pressure oxidative leaching with sulphuric acid. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 241, 116699. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Zeng, Q., Feng, Y., Wang, R., Huang, W., Wang, F., Liu, Z., Recovery of valuable elements from copper slag through low-temperature sulphuric acid curing and water leaching. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 114880. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Zhu, N., Mao, F., Zhang, J., Huang, X., Li, F., Li, X., Wu, P., Dang, Z. A novel strategy for harmlessness and reduction by alkali disaggregation of fayalite (Fe2SiO4) coupling with acid leaching. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123791. [CrossRef]

- Nadirov, R.K., Syzdykova, L.I., Zhussupova, A.K., Usserbaev, M.T. Recovery of value metals from copper smelter slag by ammonium chloride treatment. International Journal of Mineral Processing 2013, 124, 145-149. [CrossRef]

- Sun J., Zhang, T., Shan, P., Liu, D., Dong, L. Kinetic analysis of copper extraction from copper smelting slag by sulphuric acid oxidation leaching. Minerals Engineering 2024, 216, 108886. [CrossRef]

- Ospanova, A., Kokibasova, G., Kadirbekova, A., Sadykov, T., Sydykanov, M., Ospanova, G. Study on the leaching process for copper from the production waste of the Balkhash copper smelter with the addition of an oxidizing agent. Journal of the University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy 2025, 60(5), 3, 861-868. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Rui-lin, M., Wang-dong, N., Hui, W. Selective leaching of base metals from copper smelter slag. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 103, 25-29. [CrossRef]

- Mussapyrova, L., Nadirov, R., Baláž, P., Rajnák, M., Bureš, R., Baláž, M. Selective room temperature leaching of copper from mechanically activated copper smelter slag. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 12, 2011–2025. [CrossRef]

- Carranza, F., Romero, R., Mazuelos, A., Iglesias, N., Forcar, O. Biorecovery of copper from converter slags: Slag characterization and exploratory ferric leaching tests. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 97, 39-45. [CrossRef]

- Babaian, I., Chen, J., Shevchenko, M., Shishin, D., Jak, E. Characterization of slag leachability in support of slag recycling: Development of experimental methodology. Sustainable Materials and Technology 2025, 44, e01409. [CrossRef]

- Potysz, A., Kierczak, J., Fuchs, Y., Grybos, M., Guibaud, G., Lens, P.N.L., van Hullebusch, E.D. Characterization and pH-dependent leaching behavior of historical and modern copper slags. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2016, 160, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H., Särkijärvi, S., Puhakka, J.A., Peuraniemi, E., Junnikkala, S., Tuovinen, O.H. Chemical and bacterial leaching of metals from a smelter slag in acid solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 159, 46-53. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, P., Spasova, I., Groudeva, V., Nicolova, M., Spasova, I., Lazarova, A., Iliev, M., Ilieva, R., Groudev, S. Bioleaching of valuable components from a pyrometallurgical final slag. Solid State Phenomena 2017, 262, 696-699. [CrossRef]

- Jarosikova, A., Ettler, V., Mihaljevic, M., Kribek, B., Mapani, B. The pH-dependent leaching behavior of slags from various stages of copper smelting process; environmental implications. Journal of Environmental Management 2017, 187, 178-186. [CrossRef]

- Harimana, J., Makangila, M., Mundike, J., Maseka, K.K. Effect of particle size, pH, and residence time on mobility of copper and cobalt from copper slag. Scientific African 2024, 23, e02117. [CrossRef]

- Weng, W., Lan, Y., Tang, D., Chen, H., Xia, J., Chen J., Zhong, S. Acid leaching of copper from copper slag based on machine leaching analysis. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 379(3), 135025. [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H., Lavonen, L., Kuusenaho, M., Kolli, A., Närhi, H., Vestola, E., Puhakka, J.A., Tuovinen, O.H. Bioleaching and recovery of metals from final slag waste of the copper smelting industry. Minerals Engineering 2011, 24, 1113-1121. [CrossRef]

- Potysz, A., Lens, P.N.L., van de Vossenberg, J., Rene, E.R., Grybos, M., Guibaud, G., Kierczak, J., van Hullebusch, E.D. Comparison of Cu, Zn, and Fe bioleaching from Cu-metallurgical slags in the presence of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Applied Geochemistry 2016, 68, 39-52. [CrossRef]

- Mikoda, B., Potysz, A., Kmiecik, E. Bacterial leaching of critical metal values from Polish copper metallurgical slags using Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 236, 436-445. [CrossRef]

- Groudeva, V.I., Krumova, K., Groudev, S.N. Bioleaching of a rich-in-carbonates copper ore at alkaline pH. Advanced Materials Research 2007, 20-21, 103-106. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.W., Santos, R.M., Monballiu, A., Gryselbrecht, K., Martens, J.A., Matos, M.L.T., Gerven, T.V., Meesschaert, B. Effect of bioleaching on the chemical, mineralogical and morphological properties of natural and waste-derived alkaline materials. Minerals Engineering 2013, 48, 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., Singh, G., Dwivedi, S.K. Application of bioleaching for metal recovery. In Resource Recovery in Industrial Waste Waters, 1st ed.; Sillanpää, M.K.., Khadir, A., Gurung, K., Eds.; Publisher: Elsevier, 2023, pp. 295-318. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C. & Pandey, B.D. (2012). Bio-processing of solid wastes and secondary resources for metal extraction — A review. Waste Management, 2012, 32 (1), 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Potysz, A., Grybos, M., Kierczak, J., Guibaud, G., Lens, P.N.L., van Hullebusch, E.D. Bacterially-mediated weathering of crystalline and amorphous Cu-slags. Applied Geochemistry 2016, 64, 92-106. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh S, Paul AK. Bioleaching of nickel by Aspergillus humicola SKP102 isolated from Indian lateritic overburden. J. Sust. Min, 2016;15(3), 108-114. [CrossRef]

- Dusengemungu, L., Kasali, G., Gwanama, C., Mubemba, B. Overview of fungal bioleaching of metals. Environmental Advances 2021, 5, 100083. [CrossRef]

- Marier, J. & Boulet, M. Direct determination of citric acid in milk with an improved pyridine acetic anhydride method. Journal of Dairy Science 1958, 41, 1683. [CrossRef]

- Bergermann, J. & Elliot, J.S. (1955). Method for direct colourimetric determination of oxalic acid. Analytical Chemistry 1955, 27(6), 101401015. [CrossRef]

- Mihailova, I., Mehandjiev, D. Characterization of fayalite from copper slags. Journal of the University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy 2010, 45, 3, 317-326.

- Bosshard, P.P., Bachofen, R., & Brandl, H. Metal leaching of fly ash from municipal waste incineration by Aspergillus niger. Environmental Science & Technology 1996, 30, 3066-3070. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Li, H., Tian, W., Wang, X., Wang, X., Jia, X., Shi, B., Song, G., & Tang, Y. (2015). Leaching of valuable metals from red mud via batch and continuous processes by using fungi. Minerals Engineering 2015, 81, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Hausrath, E.M., Navarre-Sitchler, A.K.N., Sak, P.B., Steefel, C.I., Brantley, S.L. Basalt weathering rates on Earth and the duration of liquid water on the plains of Gusev Crater Mars. Geology 2008, 36(1), 67-70. [CrossRef]

- Turan, M.D., Sari, Z.A., Nizamoglu, H., Özcan, T. Dissolution behavior and kinetics of copper slag under oxidative conditions. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2024, 205, 324-334. [CrossRef]

- Panda, S., Mishra, S., Rao, D.S., Pradhan, N., Mohapatra, U., Angadi, S., Mishra, B.K. Extraction of copper from copper slag: Mineralogical insights, physical beneficiation and bioleaching studies. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2015, 32, 667-676. [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, A.H., Särkijärvi, S., Puhakka, J.A., Peuraniemi, E., Junnikkala, S., Tuovinen, O.H. Solid phase changes in chemically and biologically leached copper smelter slag. Minerals Engineering 2017, 106, 97-101. [CrossRef]

- Elomoa, H., Seisko, S., Lethola, J., Lundström, M. A study on selective leaching of heavy metals vs. from fly ash. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management 2019, 21, 1004-1013. [CrossRef]

- Sukla, L.B., Kar, R.N. & Panchanadikar, V. Leaching of copper converter slag with Aspergillus niger culture filtrate. Biometals 1992, 5, 169–172. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, P., Nicolova, M., Spasova, I., Iliev, M., Ilieva, R., Groudeva, V., & Groudev, S. Bioleaching of magnesium and non-ferrous metals from nickel-silicate ore. In: Proceedings of XIX Mineral Processing Congress; Kelmendi, S., Basholli, H., Demi, G., Fetahu, K., & Domi, S., Eds., Publisher: Institute of raw materials processing, energetics and environment, Prishtine. Kosove, 2023, pp. 45-53. ISBN 978-9951-9138-0-5.

- Safari, H., Rezaee, M., Chelgani, S.C. Ecofriendly leaching agents for copper extraction-An overview of amino and organic acid applications. Green and Smart Mining Engineering 2024, 1, 336-345. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, P., Nicolova, M., Spasova, I., Iliev, M., Ilieva, R. Biological leaching of copper, zinc, and cobalt from pyrometallurgical copper slags using Aspergillus niger and Penicillium ochrochloron. Journal of Ecological Engineering 2025, 26(12), 197-213. [CrossRef]

- Meshram, P., Bhagat, L., Prakash, U., Pandey, B.D., Abhilash. Organic acid leaching of base metals from copper granulated slag and evaluation of mechanisms. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly 2017, 56(2), 168-178. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, P., Nicolova, M., Spasova, I., Iliev, M., Ilieva, R. Non-ferrous metals extraction from copper slags by bioleaching with Aspergillus niger. Journal of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy (accepted for publication).

- Qu, Y., Li, H., Wang, X., Tian, W., Shi, B., Yao, M., Cao, L., Yue, L. Selective parameters and bioleaching kinetics for leaching vanadium from red using Aspergillus niger and Penicillium tricolor. Minerals, 2019, 9, 697. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S., Dey, R., Mukherjee, S., Banerjee, P.C. Bioleaching of nickel and cobalt from lateritic chromite overburden using the culture filtrate of Aspergillus niger. Applied Biochemistry & Biotechnology, 2013, 170, 1547-1559. [CrossRef]

| Chemical element, % | Sample F | Sample III |

|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.36 | 0.47 |

| Zn | 1.93 | 1.34 |

| Co | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Fe | 27.2 | 36.3 |

| Si | 15.9 | 16.0 |

| Ca | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| Mn | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Al | 2.78 | 2.58 |

| P | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| S | 0.91 | 1.06 |

| pH (H2O) | 7.95 | 8.81 |

| Chemical element, % | Sample F | Sample III |

|---|---|---|

| Fayalite (Fe2SiO4) | 33 | 56 |

| Pyroxene group (XY(Si,Al)2O6): | ||

|

10 | - |

|

- | 44 |

| Protomangano-ferro-anthophyllite ( ) | 56 | - |

| Index | Penicillium ochrochloron | Aspergillus niger |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 3.24 | 2.58 |

| Citric acid, g/L | 18.9 | 24.8 |

| Oxalic acid, g/L | 10.9 | 8.1 |

| Acidity, g/L | 0.65 | 0.94 |

| Fungal biomass, g/L | 7.92 | 9.75 |

| Index | Penicillium ochrochloron | Aspergillus niger | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample F | Sample III | Sample F | Sample III | |

| pH | 5.27 | 7.19 | 4.39 | 6.03 |

| Cu leached, mg/kg | 715 | 97 | 810 | 151 |

| Cu leaching, % | 19.9 | 2.1 | 22.5 | 3.2 |

| Zn leached, mg/kg | 4490 | 1407 | 4850 | 1568 |

| Zn leaching, % | 23.3 | 10.5 | 25.1 | 11.7 |

| Co leached, mg/kg | 345 | 61 | 400 | 69 |

| Co leaching, % | 38.3 | 12.2 | 44.4 | 13.8 |

| Copper slag/copper slag residue | Relative content, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fayalite |

Pyroxene group | Proto- mangano-ferro-anthophyllite |

Magnetite |

|||

| Clinopyroxene | Diopside | Augite | ||||

| Sample F | ||||||

| Raw sample | 50 | 20 | - | - | 30 | - |

| Leaching with the spent medium at 55 °C | 60 | - | - | 37 | - | 3 |

| Leaching with the spent medium supplementation with 5 g H2SO4/L at 55 °C | 40 | - | - | 28 | - | 32 |

| Sample III | ||||||

| Raw sample | 65 | - | 35 | - | - | - |

| Leaching with the spent medium at 55 °C | 40 | - | - | 32 | - | 25 |

| Leaching with the spent medium supplementation with 5 g H2SO4/L at 55 °C | 33 | - | - | 45 | - | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).