1.1. Morphology

An analysis of the anodizing temperature influence on the geometric parameters of porous AAO formed using H

2SeO

4 electrolyte was carried out.

Figure 1 shows surface images of AAO obtained at various oxide formation temperatures.

The sample formed at a current density of 5 mA/cm

2 in 0.5 M H

2SeO

4 at 5 °C represents porous layer in hexagonal order. It strives to the structure where one porous cell contains one large pore (

Figure 1a). Moreover, it is clearly seen that the cell consists of 2 layers: the brighter inner layer and darker out layer. Such structure corresponds to the descriptions of a double-layer porous cells reported in [

23,

24,

25], where it was noted that the inner layer has a compact, low-defect structure, while the outer layer is spongy, and it contains embedded electrolyte ions.

The raising of the anodization temperature to 25 °C results in the disordering of the porous structure, with the formation of multiple small-diameter pores within a single porous cell (

Figure 1b). Additionally, the diameter of the porous cell decreases (a trend similar to that observed with a reduction in current density [

2]). The double-layer structure is maintained. With a further increase in temperature, the porous cell diameter continues to decrease, while the pore diameter increases due to the higher etching rate of the pore walls. Consequently, the thickness of the outer layer reduces significantly (

Figure 1c).

The same trends, but more pronounced, are observed for the anodization temperature increasing in more concentrated electrolytes, such as 1.5 M H

2SeO

4 (

Figure 2). It is worth noting that with increasing concentration, the current density 3 times higher was set, as it is well known that current density increasing leads to the oxide growth rate increase and contributes to maintain a sufficient value of mechanical stress in the films, which leads to the formation of an ordered porous structure [

8,

21]. As a result, the ordered nanostructures have been formed under the technological parameters: 15 mA/cm

2, 1.5 M H

2SeO

4 at 5 °C (

Figure 2a). The increase of the temperature to the 25 °C has led to the disordering of the porous structure, with the formation of numerous small-diameter pores (

Figure 2b). Also, the cell diameter has decreased significantly (from 84 ± 7 nm to 52 ± 5 nm). Upon raising the temperature to 40 °C (

Figure 2c and 3a), destructive etching of the pore walls occurs in the upper part of the oxide (

Figure 2c). Consequently, the oxide has been divided into an upper layer (individual filament-like fibers,

Figure 2c and

Figure 3a) and a porous layer (cylindrical pores,

Figure 3b). The further cell diameter decreasing is observed, the outer layer becomes visually undistinguishable (

Figure 3).

The results of the morphology investigation of AAO samples formed under various technological parameters in H

2SeO

4 solutions are presented in

Table 1.

Based on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results, it was established that the porosity of oxide matrices obtained in 0.5 M H2SeO4 varies from 1.5% (for the samples formed at 5 °C) to 16.5% (for the samples formed at 40 °C). An increase in the electrolyte concentration significantly enhances the chemical etching of pore walls. The porosity varies from 1.7% to unmeasurable values, as the porous structure in the upper part of the oxide is completely etched away, causing oxide disintegration into fibers.

Since the trends observed with the electrolyte temperature increasing were the same for samples obtained both at electrolyte concentrations of 0.5 M and 1.5 M, but its variation was stronger for the samples obtained in 1.5 M H2SeO4, the further results are presented only for the samples formed in 1.5 M H2SeO4.

1.1. Chemical and Crystal Structure

To determine the elemental composition and chemical bonds, an investigation was conducted using the XPS method. Typical XPS spectra of AAO formed in selenic acid solution is presented in

Figure 4.

The spectra of the samples formed at different temperature do not vary significantly, although the intensity of the peaks related to Se slightly decreases with the anodization temperature increasing. Atomic concentrations were determined by the method of relative elemental sensitivity factors from the survey spectrum, using the integrated intensities of the following lines: C 1s, O 1s, Al 2p and Se 3d. These results are shown in

Table 2.

According to XPS data, Se content is higher on the surface of the samples. Thus, the presence of selenium is partially caused by its adsorption from the electrolyte on the AAO surface and its incomplete removal during washing. It can be noted, that Se may exist both in the form of selenates and in the form of elemental selenium, as during the anodic oxidation, the selenic acid partially disproportionates into selenide anions and even Se

0 species [

7,

15]. Se content decreases with anodization temperature from 2 at.% to less than 1 at.%.

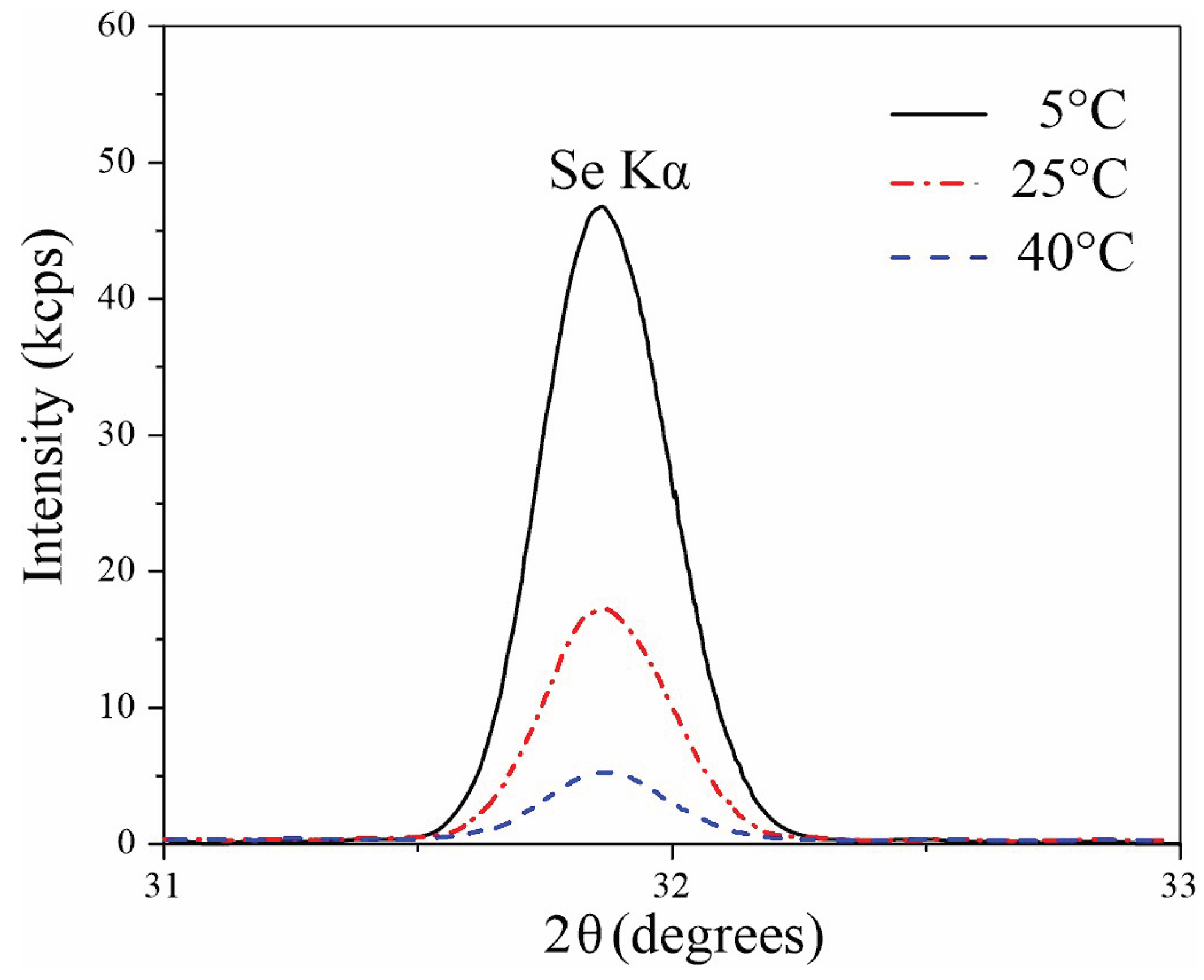

Since the obtained selenium concentration values are close to the detection limit, especially for the sample formed at 40 °C, additional WDXRF investigation was performed to determine the ratio of selenium in films obtained at different synthesis temperatures (

Figure 5). WDXRF studies showed a distinct selenium peak at 2θ = 31.87 degrees. The WDXRF results are consistent with the XPS data: as the electrolyte temperature increases, the intensity of selenium peak decreases. The intensity of Se peaks in the samples formed at 5 °C is 2.6 and 7.5 times higher than intensity of AAO formed at 25 °C and 40 °C, respectively.

To our knowledge, studies of AAO composition for the samples, fabricated at different synthesis temperatures, have not been conducted by other researchers yet. However, we can compare our results for 5 °C sample with similar samples. Results of our XPS and WDXRF (1-2%) analyses are equal to the values obtained by Kamnev et al. for Al

2O

3/ZrO

2 and Al

2O

3/NbO

2 composites although these objects are different: composites are formed by interaction of growing ZrO

2 or NbO

2 nanocolumns with the narrow outer part of AAO, which is more contaminated by Se [

11,

15]. Se content for AAO, obtained in 0.3 M H

2SeO

4 at 5 °C is 1.6 at.% overall (EDX), that correlates with our data, without taking into account the difference in Se content on the surface and in depth of the AAO, demonstrated in our investigation. Nevertheless, Se content in AAO formed at 0 °C determined by EDX in [

14] varied depending on the anodization voltage from 9 to 25 at.%, which is sufficiently higher. Most likely, this difference is caused by lower temperature of AAO synthesis (and it correlates with our data that Se concentration is higher at lower temperatures) and anodization in “hard anodization” regimes. It is also important to keep in mind that since the K and L X-ray emission lines of Al and Se are estimated in the same energy range (~1.4 kV), this significantly complicates the task of correctly identifying these overlapping peaks [

26].

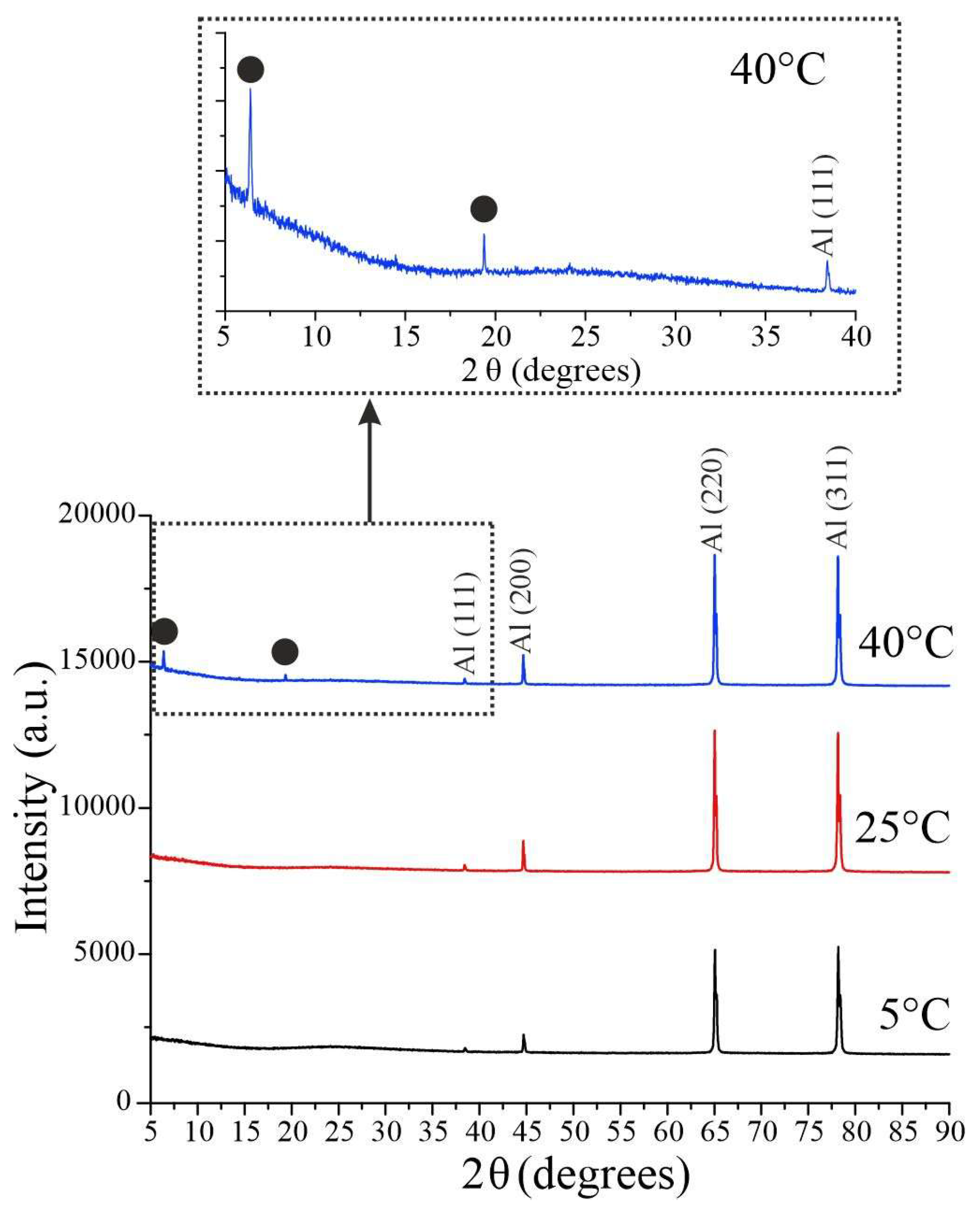

Figure 6 shows the diffraction patterns of samples prepared at different electrolyte temperatures. All peaks detected in the spectra for anodization temperatures of 5 °C and 25 °C relate to the aluminum substrate and correspond to JCPDS Card No.04-0787. Porous AAO samples are amorphous. Interestingly, when the temperature increases to 40 ℃, two peaks appear at 6.41, 19.36 degrees, which could be attributed to γ-Al

2O

3 JCPDS Card No.29-0063 that may indicate the beginning of crystallization of the aluminum oxide film. The effect is reproduced on both similar substrates and substrates of different thicknesses and grades. This effect for AAO samples synthesized in H

2SeO

4 is discovered for the first time.

Previously, researchers noted that porous aluminum oxide, predominantly an anion-free oxide layer, can be crystallized by electron beam irradiation of the sample, for example, during its examination in the scanning electron microscope. And although the presence of crystalline alumina in coatings was not proved for porous alumina films formed in phosphoric, oxalic and sulfuric acids, it was found that anodizing in mixture of sulfuric and chromic acid can result in amorphous alumina with traces of γ-Al

2O

3 [

27]. Such features of the crystalline structure were observed for samples synthesized at 20 °С; therefore, the emergence of a crystalline phase in samples obtained in electrolytes heated up to 40 °C is also possible.

1.1. Luminescent Properties and Paramagnetic Centers

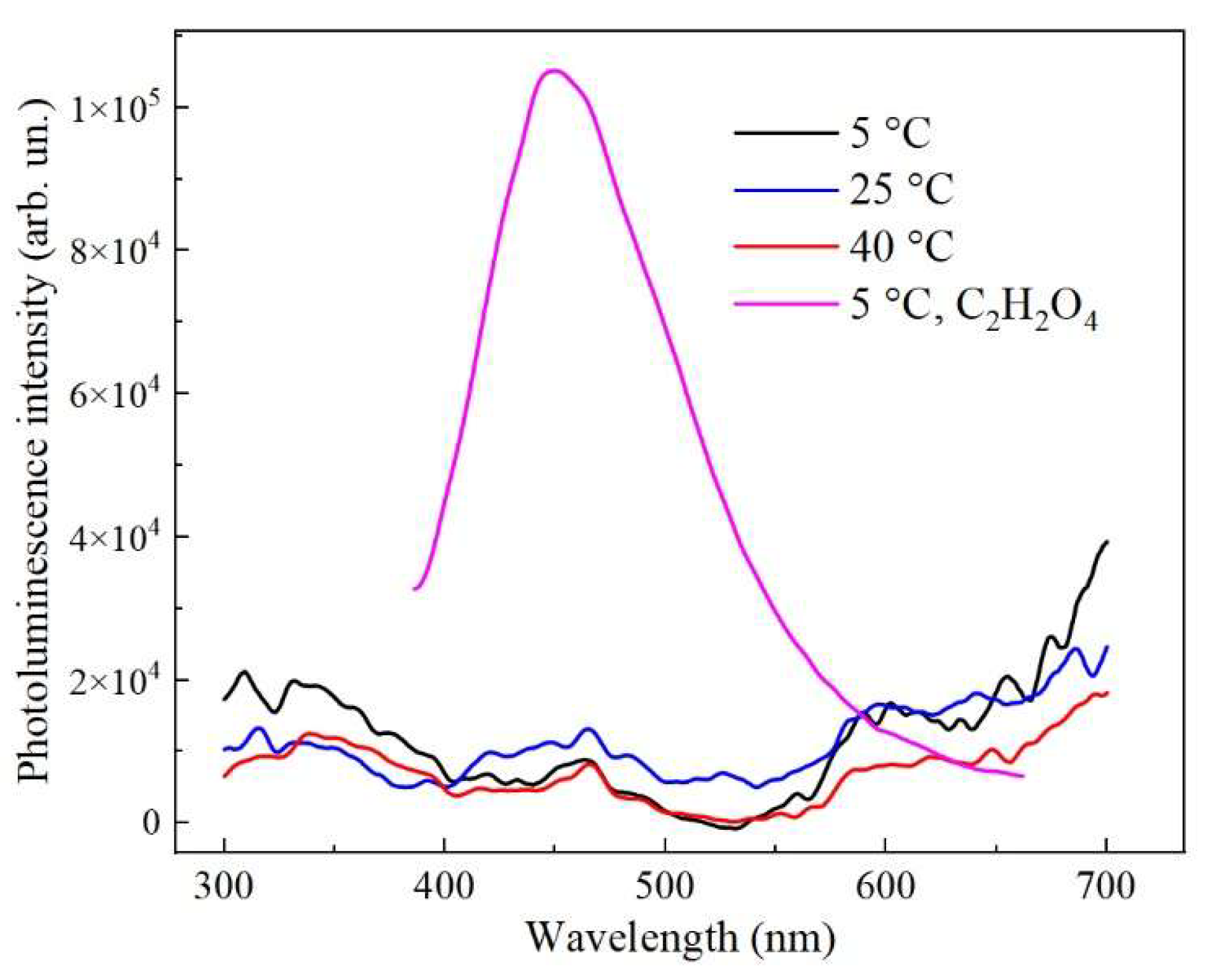

Figure 7 shows the photoluminescence spectra of porous AAO samples formed at 5-40 °C in 1.5 M H

2SeO

4. The samples exhibit weak luminescence at the noise level, without pronounced peaks or photoluminescence (PL) bands. Changes in the anodization temperature do not lead to crucial changes in the PL spectra of the samples.

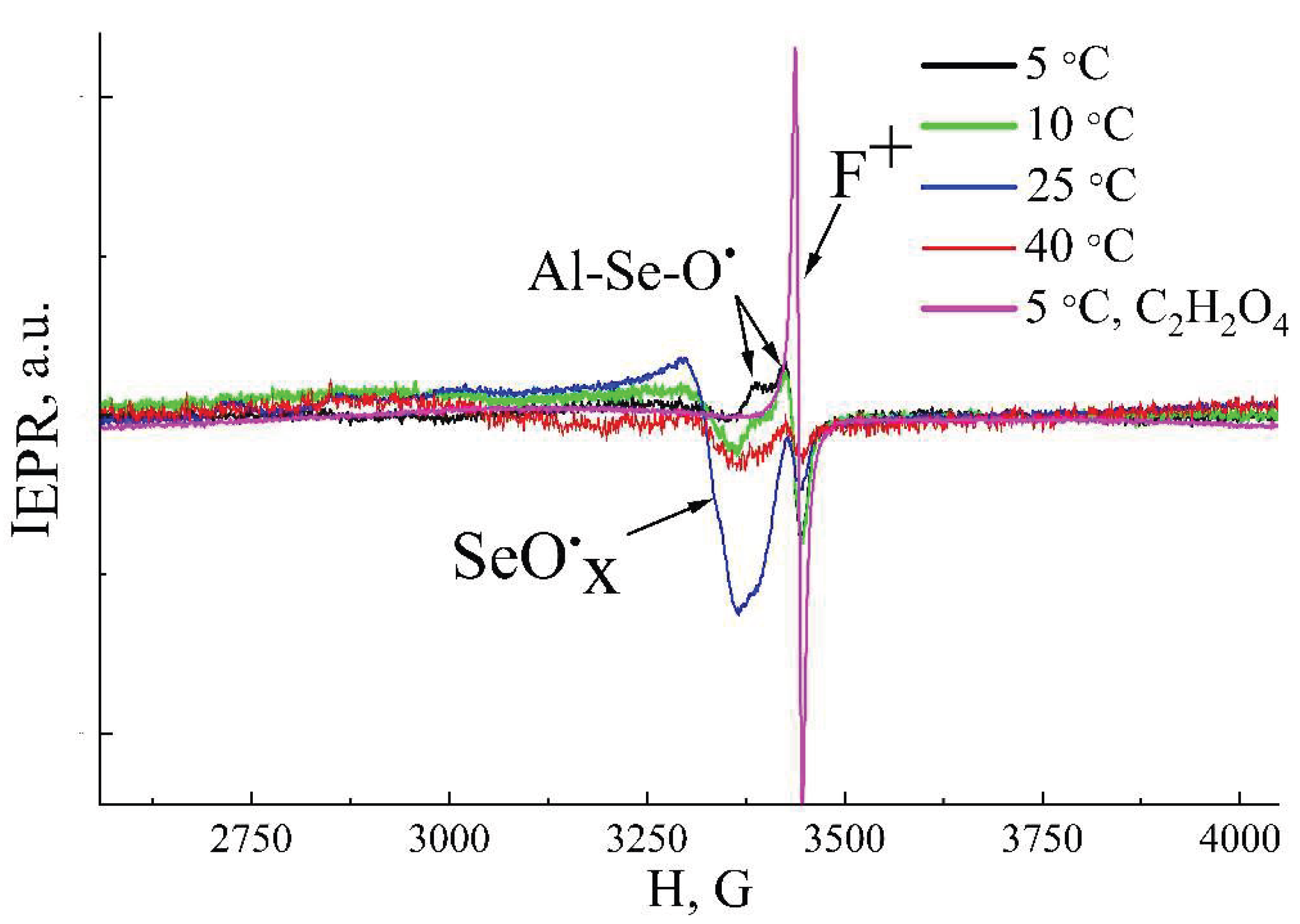

The EPR spectra for the samples prepared at different temperatures are presented in the

Figure 8. It can be noted, that all EPR spectra have a complex shape due to the presence of several different signals, indicating several types of paramagnetic centers. All samples exhibit lines with g

I = 2.0024±0.0005. This signal has been repeatedly observed previously in the EPR spectra of AAO obtained in different electrolytes and it is attributed to oxygen vacancies with the unpaired electrons (F

+-centers) in aluminum oxide [

18,

19,

20,

28].

The line, associated with F

+ centers, overlaps with the EPR signal of anisotropic shape with g

II1 = 2.0322±0.0005, g

II2 = 2.0081±0.0005. Such a g-factor values suggest that the electron belongs to an oxygen atom in configuration similar to O

−, and such paramagnetic centers were detected previously in the structure of different metal oxides [

29]. Thus, it is assumed that this EPR signal is related to an oxygen radical that has one unpaired bond, while the second bond pairs it with another atom. Since the EPR signal is observed only in samples formed in selenic acid and it is not detected for AAO synthesized in other electrolytes, it can be assumed that the oxygen is bonded to a selenium atom (>Al-Se-O*). Moreover, since the EPR signal persists even after additional etching, washing, and complete drying, and disappears only upon almost complete etching of the porous structure walls, it can be concluded that it corresponds to ions embedded in the oxide rather than residual electrolyte. As this radical is not characteristic for samples formed in sulfuric acid (the electrolyte with the structure similar to selenic acid, but it does not decompose to sulfides), it can be hypothesized that it may be a decomposition product of selenic acid (to selenides). A third type of EPR signal with g

III=2.0735±0.0005 is also identified. This EPR signal is detected in AAO samples prepared at anodizing temperatures starting from 10 °C, and it reaches its maximum intensity in samples anodized at 25 °C. The signal is similar to the signal detected in oxides formed in sulfuric acid, associated with sulfate complexes [

30]. Since the molecules of sulfuric and selenic acids have similar structures, and, in addition, similar g-factor values are observed for the SeO

4− radicals in Na

2SeO

4 samples [

31], we believe that the EPR signal with such a g-value is associated with a selenate-like radical with an oxygen atom containing an unpaired electron.

The intensity of EPR signal, attributed to F

+ centers, decreases with anodization temperature increasing. The maximum concentration of F

+-centers is Nₛ

F=8.2·10

15 g

-1 in AAO samples, obtained at 5 °C. The highest concentration of paramagnetic centers with g

II=2.0322 (associated with >Al-Se-O*centers) is calculated as Nₛ

O=10

17 g

-1 for samples formed at low temperatures (5–10 °C), and the signal decreases with the anodization temperature increasing. The intensity of the signal with g

III=2.0735±0.0005 increases with the anodization temperature increasing up to 25 °C. At this anodization temperature, the EPR intensity increases sharply, and the concentration of paramagnetic centers reaches the value Nₛ

S=6·10

18 g

-1. For samples synthesized at 40 °C, the intensities of all EPR signals and, accordingly, the defect concentrations decrease sharply (

Figure 8).

It is also worth mentioned that since the PL of the samples has an extremely weak intensity, which does not change significantly with a change in the synthesis temperature in the range of 5-40 °C (

Figure 7), this indicates that various oxygen related radicals (defects with g

II=2.0322 and g

III=2.0735) are not PL centers. Oxygen vacancies (F

+-centers) are reported to determine PL in porous alumina [

18,

19,

20,

28]. However, in our samples F

+-centers concentration is rather low (does not exceed significantly 10

16 g

-1), which can explain low PL intensity (

Figure 7). To test this hypothesis, we synthesized AAO samples in oxalic acid for comparison, since such structures are known to have intense PL [

18,

19,

26]. Indeed, the obtained AAO samples formed in C

2H

2O

4 have intense PL (

Figure 7). These samples were also investigated by the EPR method. The oxygen vacancies are detected (

Figure 8), and its concentration (N

sF=2·10

17 g

-1) is an order of magnitude higher than the concentration of vacancies in the samples obtained in selenic acid. At the same time, an increase in the concentration of oxygen-containing radicals up to 6·10

18 g

-1 in samples formed in H

2SeO

4 does not affect the PL spectra. Thus, the PL intensity correlates with the concentration of F

+ centers and its intensity can be controlled by the electrolyte variation.

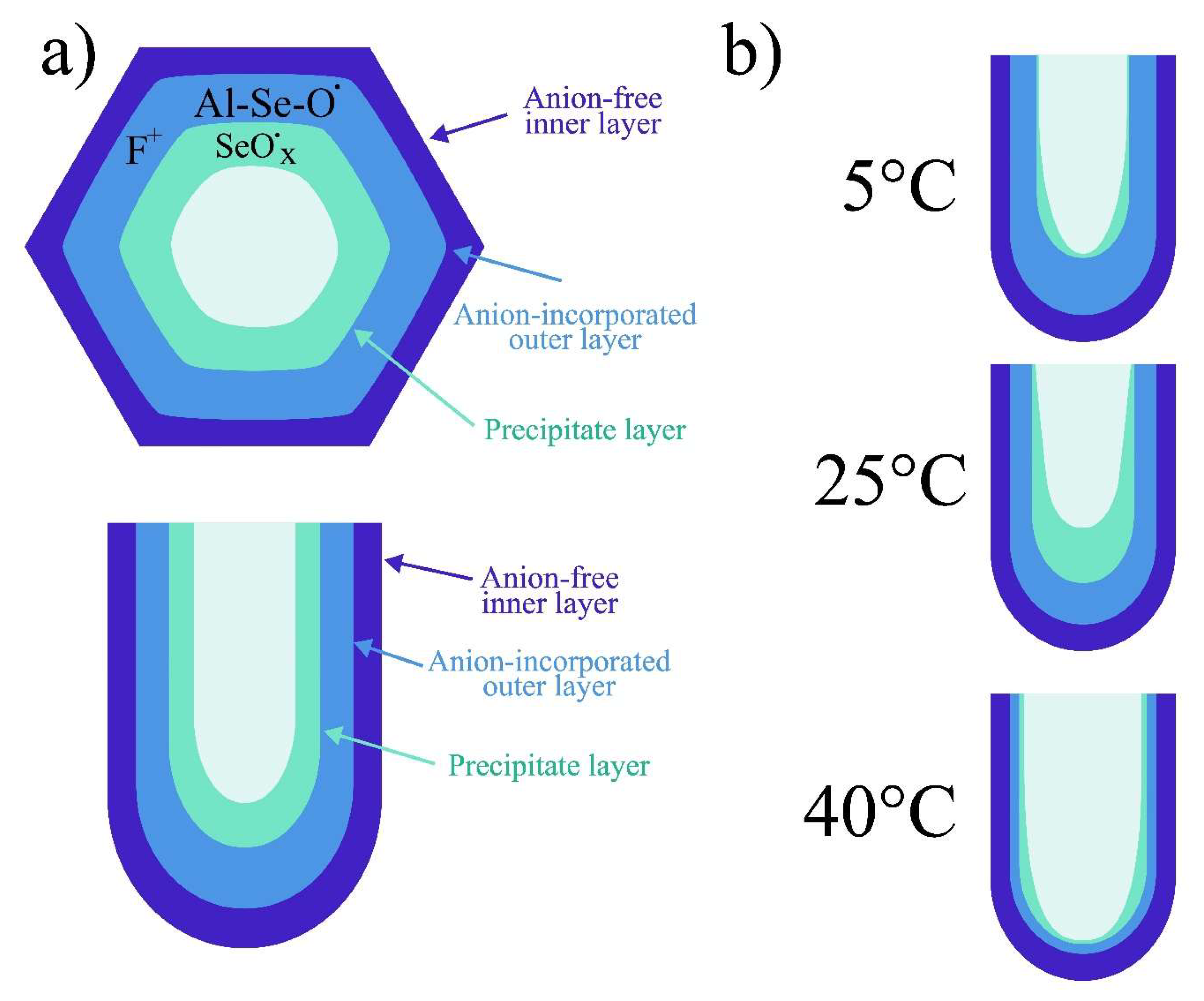

To explain the behavior of paramagnetic centers observed for samples formed at different anodization temperatures, schematic representation of the AAO cell structure showing different paramagnetic centers location is given in

Figure 9.

As it was mentioned in section 3.1 «Morphology», the synthesis temperature increasing leads to the etching of oxide walls. This, eventually, leads to decrease in the proportion of the anion-incorporated outer layer of the AAO compared to its total volume. The concentration of oxide defects with signals gI and gII gradually decreases with the reduction of the outer layer thickness, both as a result of the synthesis temperature increase from 5° to 40° and due to the thinning of the outer layer during additional post-etching of the sample. This indicates that the gI and gII defects are located in the outer layer of the oxide and they are uniformly distributed throughout it.

The most challenging is to understand the g

III EPR signal. Its intensity begins to increase with AAO synthesis temperature rising, but only up to 25 °C. XPS and WDXRF compositional analysis methods do not reveal a significant increase in the concentration of Se in a different valence state compared to the sample synthesized at 5 °C. However, the samples used for these methods are significantly thinner. It is possible that the signal is associated with precipitates in the thin surface layer of the AAO (

Figure 9b). At lower temperatures, the chemical activity of the electrolyte is lower, and the pore size is larger, which may result in fewer adsorbed particles on the oxide wall surfaces. As the temperature increases, the activity of the electrolyte rises, and the pores become narrow, that could lead to more active species precipitation. In samples with a thickness of several micrometers, the oxide is rinsed more effectively compared to the samples with thicknesses of tens of micrometers. Therefore, XPS and WDXRF do not detect any substantial changes in composition that could explain the emergence and increase of the g

III signal. However, in thicker samples, the precipitates remain and are detected by EPR, which, among other things, is the most sensitive method for detecting changes in sample composition.

The decrease of concentration of all types of centers at 40 °C can be explained by the significant etching of the porous structure walls, which removes the defective layer containing both embedded ions, other species, and vacancies. As a result, a more perfect, near-crystalline layer of aluminum oxide remains at the samples, which is confirmed by XRD results. The total concentration of defects in this layer tends to zero (

Figure 9c).

Conclusions

Based on a comprehensive study of AAO films formed in selenic acid at different anodizing temperatures, we can draw a number of important conclusions from both fundamental and practical points of view. It has been established that with an increase of the synthesis temperature, the diameter of the AAO cells decreases. Meanwhile AAO walls etching increases, causing pore diameter increasing, and even leading to etching of AAO formed in 1.5 M H2SeO4 to individual fibers at 40 °C. The concentration of selenium in the samples does not exceed 2 at.%. When the temperature increases to 40 ℃, two peaks appear in the XRD spectrum at 6.41, 19.36 degrees, which may indicate the beginning of crystallization of the aluminum oxide. The samples exhibit very weak luminescence without pronounced PL bands. In AAO formed in a selenic acid electrolyte, different paramagnetic centers were discovered: F+ centers; for the first time ˗ centers in which the electron belongs to an oxygen atom in configuration similar to O− centers (>Al-Se-O*), and paramagnetic defects structurally similar to selenates (gIII=2.0735±0.0005). Using test experiments with AAO samples synthesized in oxalic acid, it was established that of all the defects found in AAO synthesized in selenic acid, only F+ centers are responsible for luminescence. With an increase of the electrolyte temperature, the selenium content, luminescence intensity, concentration of F+ centers and (>Al-Se-O*)-centers decrease. Concentration of all types of centers decreases drastically at 40 °C. These tendencies can be explained by the significant etching of the porous structure walls, which removes the defective outer layer containing both embedded impurities from the electrolyte and oxygen vacancies. As a result, only inner alumina layer, with anion-free near-crystalline structure remains, which is confirmed by XRD results. A geometric model is proposed that explains the results obtained in the set of AAO samples synthesized at different temperatures. The obtained results are new and original and can be purposefully used for the manufacturing of AAO with specified optical properties.