1. Introduction

Online Social Networks (OSNs) have become central platforms for public discourse on sensitive geopolitical and humanitarian issues, including irregular migration. Platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram play a crucial role in disseminating migration-related content — from breaking news and eyewitness reports to grassroots commentary. However, the informal style, linguistic diversity, and rapid diffusion of content on these platforms pose significant challenges for computational detection and monitoring of such discourse.

The detection of irregular migration narratives is particularly complex in multilingual environments, where resources for language-specific Natural Language Processing (NLP) remain limited, and annotated training data is often scarce. While prior research in hate speech and misinformation detection has made progress, much of it focuses on high-resource languages and overlooks emerging platforms like Telegram.

Recent advances in transformer-based architectures, including mBERT, XLM-RoBERTa, and mT5, have enabled robust cross-lingual generalization in low-resource settings. These models capture syntactic and semantic structures across languages and have proven effective for multilingual classification tasks. Nonetheless, their application to Telegram and low-resource migration-related corpora remains underexplored, revealing a methodological gap in the literature.

This paper addresses these challenges by introducing a multilingual classification pipeline for detecting online discourse related to irregular migration, including unauthorized border-crossing, asylum-seeking, detention, and other relevant narratives, across five under- and mid-resourced languages: English, French, Greek, Turkish, and Arabic. The pipeline integrates rule-based annotation, language-specific preprocessing, and model benchmarking, and is tested on content from both X and Telegram.

This study builds upon our previous work [

1], which focused on the classification of tweets across four languages (English, French, Turkish, Arabic), by extending it in four major directions:

Cross-platform expansion through the integration of Telegram data.

Wider linguistic coverage with the addition of Greek.

Refined keyword-based annotation, combining TF-IDF with expert validation.

Comparative model benchmarking including traditional ML and modern transformer-based approaches, as well as Large Language Models (LLMs).

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

Development of a multilingual corpus spanning two OSNs (X and Telegram) and covering both Western and non-Western languages.

Comparative evaluation of classification models, including Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, Neural Networks, SetFit, mBERT, and ChatGPT LLM (version GPT-4o).

Exploration of language-specific vs unified (mixed-language) models, assessing their relative performance across monolingual and cross-lingual setups.

Empirical insights into the performance of transformer-based models in low-resource language settings relevant to migration discourse.

To this end, we investigate the following research question: Can LLMs, such as ChatGPT, reliably detect irregular migration discourse across under- and mid-resourced languages in a zero-shot setting, and how do they compare to fine-tuned transformer models and traditional classifiers?

By combining keyword-based annotation, multilingual preprocessing, and a comparative evaluation of classification models, this study contributes an interpretable, cross-platform NLP framework applicable to low-resource digital migration contexts.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on multilingual text classification and migration discourse detection.

Section 3 presents the data collection and preprocessing pipeline.

Section 4 reports experimental results across languages and models.

Section 5 discusses thematic insights and limitations of the study. Finally, section 6 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

The intersection of migration, hate speech, and digital discourse has drawn increasing scholarly attention, particularly in the context of multilingual and low-resource environments. This section surveys relevant literature across three thematic axes: migration-focused hate speech detection, multilingual NLP approaches in OSNs, and methods for sentiment and discourse analysis in irregular migration contexts.

2.1. Hate Speech Detection Targeting Migrants

Online hostility toward migrants has been a recurring topic of study within computational social science. Recent advances have leveraged transformer-based models to detect hate speech targeted at migrants. SocialHaterBERT, a model combining textual cues with user metadata for binary hate speech classification, was introduced [

2]. Hybrid methods and contrastive learning techniques for hate content detection were examined [

3].

A semi-supervised generative model for multilingual hate speech detection was proposed [

4]. Regional case studies offer important context. Discursive patterns around illegal immigration in Northeast India were analyzed [

5], revealing the entwinement of local dialects and nationalistic narratives. Such observations underline the sociolinguistic intricacy and contextual variability of migration discourse across regions.

2.2. Multilingual NLP for Social Media Classification

Multilingual NLP presents unique challenges, especially in domains with informal and cross-lingual user input. Prior work has tackled the issue via supervised models tailored to detect hate speech across languages, often using engineered features or translation pipelines. Multilingual hate speech targeting migrants and women on X was analyzed [

6], highlighting the importance of language-specific preprocessing. Behavioral tracking approaches were proposed [

7] to detect anti-immigration discourse using user-level social media data.

SemEval-2019 Task 5 underscored the challenges of multilingual hate speech detection in English and Spanish, especially in low-resource scenarios [

8]. Transformer models such as BERT and its multilingual variants (e.g., mBERT) have increasingly been adopted as viable alternatives [

9].

Open-and closed-source LLMs were evaluated [

10] for low-resource classification, revealing architecture-level trade-offs in generalization and robustness. Multilingual immigration discourse during sociopolitical crises was examined [

11], demonstrating the need for language-specific modeling and framing awareness.

2.3. Sentiment and Migration Discourse Analysis

A related direction explores sentiment analysis and topic modeling for migration narratives. The authors of [

12] proposed a lexicon-enhanced sentiment classifier for illegal immigration tweets, combining affective lexicons and contextual embeddings. In [

13], shifts in public sentiment toward immigration during the COVID-19 pandemic were tracked using data from X (formerly Twitter).

A multilingual analysis of sentiment and stance in European migration coverage was conducted in [

14], revealing cross-cultural differences in framing. In [

15], disinformation and politically sensitive migration-related narratives were identified across X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram using Large Language Models (LLMs).

2.4. Methodological Gaps and Contributions

Despite growing interest in multilingual and migration-related NLP, two major methodological gaps persist:

The under-representation of non-Western and low-resource languages (e.g., Arabic, Greek, Turkish) in publicly available datasets.

The limited use of alternative platforms such as Telegram, which play an increasingly central role in real-time crisis communication and grassroots reporting.

A multilingual offensive language identification framework for resource-poor settings was proposed in [

16], leveraging label-efficient architectures for improved performance.

To address these research gaps, our study contributes (i) a multilingual dataset combining messages from X and Telegram built upon our previous work [

1], (ii) a rule-based labeling framework based on TF-IDF keyword identification [

17], and (iii) an evaluation of multiple classification models (traditional, transformers, LLMs) across language-specific and mixed corpora. Building upon these gaps, the following section outlines the methodology adopted to construct, annotate, and classify multilingual social media content related to irregular migration. This integrated approach addresses the identified gaps and frames the design of our classification pipeline in

Section 3.

3. Methodology

This section outlines the OSN data collection process, dataset construction and labeling procedure, and the classification pipeline used to detect irregular migration-related discourse across multiple languages and platforms.

3.1. Data Collection from X and Telegram

The dataset used in this study was constructed from two OSNs: X and Telegram. Our objective was to capture real-world, multilingual discourse related to irregular migration across both mainstream and niche digital environments.

We collected a total of 174 tweets using the Orange Data Mining toolkit [

18] and the official X API [

19]. This process builds on our earlier methodology in [

1], where we also used keyword-based querying for multilingual migration content. In the current study, we developed an expanded seed list of migration-relevant keywords in English (e.g., “boat”, “illegal”, “immigrant”, “border”), sourced through expert consultation and prior research. To ensure multilingual coverage, all English keywords were translated into Arabic, Turkish, Greek, and French. The translations were conducted manually by bilingual annotators and verified using automated translation tools (DeepL, Google Translate) to preserve semantic consistency and cultural relevance.

In addition to X content, 119 short-form messages were extracted from five public Telegram channels with explicit focus on migration-related themes. These channels were selected after screening an initial pool of 20 candidates, excluding those focused on unrelated topics (e.g., terrorism, religious proselytism). As with the X dataset, a TF-IDF-based keyword extraction process was applied to the collected Telegram texts, resulting in 12 additional migration-related terms. One duplicate was removed during manual filtering. These new terms were used to label the messages via a rule-based binary classification process, yielding the final Telegram subset.

The resulting corpus comprises 293 unique messages, consisting of 174 tweets (59.4%) and 119 Telegram messages (40.6%), all contributing to the final dataset.

Table 1 presents the distribution of messages across the six detected languages. Notably, although Farsi appeared in the Telegram dataset (78 messages, approximately 65.5% of that content), it was excluded from downstream modeling and classification, due to (a) lack of linguistic expert support for reliable keyword translation, and (b) inability to ensure consistent manual annotation. Thus, the classification experiments focus exclusively on the five aforementioned target languages: English, Arabic, Turkish, Greek, and French.

This natural imbalance reflects both the platform-specific prominence of migration narratives and the inherent linguistic diversity found in user-generated content.

3.1.1. Keyword Extraction and Language Inclusion

Although Farsi content was present in the Telegram dataset, it was not included in model training or evaluation, since the original keyword list was not translated into Farsi. Moreover, there was no available bilingual expert for validation. Rather than risk introducing inconsistencies, we opted to exclude Farsi as a source language. However, all messages (including those originally in Farsi) were translated into the five target languages using DeepL and Google Translate to ensure semantic consistency. As a result, the final dataset comprises 293 unique OSN messages, each translated into all five supported languages, resulting in a total of 1,465 language-specific instances used for training and evaluation.

Τo avoid introducing semantic noise and potential bias, we consciously excluded Farsi from multilingual evaluation due to the absence of reliable linguistic validation; a decision informed by both methodological and ethical considerations.

3.2. Dataset Labeling

To annotate the dataset, we employed a rule-based binary labeling scheme designed to ensure thematic consistency across languages, similarly to our previous work [

1]. An OSN message was labeled as migration-related if it contained at least two of the 31 domain-specific keywords, which were initially identified using a TF-IDF-based extraction process applied to the raw corpus and subsequently validated by two domain experts. Messages with fewer than two keyword matches were labeled as irrelevant.

The distribution of binary labels across the translated datasets is summarized in

Table 2. The full list of multilingual keywords used for rule-based annotation, including their source languages and verified translations, is provided in

Table 3. These terms were manually translated and semantically validated across the five target languages (English, French, Arabic, Greek, and Turkish). The resulting multilingual keyword sets were used to build language-specific matchers, enabling consistent rule-based detection across all translated corpora.

All keywords were compiled into multilingual lookup lists and integrated during preprocessing to enable pattern matching in short-form texts. As already mentioned, Farsi messages, although present in the initial corpus, were excluded from multilingual evaluation due to lack of translated keywords and low representational coverage.

The label distribution per language, as summarized in

Table 2, reflects the output of this annotation process after translation. All 293 original messages were translated into each of the five target languages, and each translated subset was independently annotated using the same keyword-based rules. This approach ensured cross-lingual comparability, even when some languages had limited original representation (e.g., Greek).

To enhance semantic interpretability and ensure conceptual consistency across languages, the 31 multilingual migration-related keywords were manually grouped into 13 thematic categories (e.g., Migration, Smuggling, Border, Transport, Authorities, Victims). This mid-level categorization facilitated the understanding and thematic validation of the keyword-based annotation schema without introducing label bias. The full keyword-to-category mapping along with additional insights are discussed in

Section 5.

3.3. Classification Pipeline

The classification pipeline, illustrated in

Figure 1, consists of five main stages: data input, preprocessing, vectorization, model training and evaluation. Each stage incorporates language-specific considerations to support robust multilingual classification.

During preprocessing, we first applied language detection using the langdetect [

20] library to ensure proper routing of each message to the correct processing stream. This was followed by tokenization and stop-word removal, implemented via NLTK [

21] modules tailored to each target language. For English, we applied lemmatization using WordNet [

22], whereas for Greek and French, we used the Snowball [

23] stemmer. Due to the morphological complexity of Arabic and Turkish, no lemmatization or stemming was performed, in order to avoid semantic distortion in short-form texts. In all languages, non-textual noise such as URLs, emojis, and user mentions was removed, and for Greek, additional diacritic normalization was applied to standardize character representations.

Following preprocessing, two vectorization strategies were employed. For traditional ML models, we used TF-IDF representations. This included the application of Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, and Random Forest classifiers. In parallel, for transformer-based architectures, we utilized sentence embeddings generated by two model families: SetFit [

24] which builds on MiniLM-L12-v2 [

25], MiniLM-L6-v2 [

26] and MPNet [

27], and Multilingual BERT (mBERT) [

9], which was fine-tuned both per language and on the combined multilingual corpus.

For training and evaluation, each model was trained using an 80/20 train-test split, and its performance was assessed using standard classification metrics: Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Given that the English and French subsets exhibited slight class imbalance, random oversampling was applied to the minority class in both cases to mitigate bias. Moreover, a multilingual (denoted as “Mixed”) corpus was constructed by aggregating all five language-specific subsets. This allowed for evaluating each model’s ability to generalize across languages under cross-lingual conditions.

The complete classification workflow is summarized in

Figure 1, which depicts the five main stages in sequence: data input, preprocessing, vectorization, training, and model evaluation.

4. Evaluation and Results

To evaluate model performance, we used standard classification metrics: Precision, Recall, and F1-score. All models were trained using an 80/20 train-test split and performance was evaluated separately for each of the five languages (English, French, Arabic, Turkish, Greek) and on a combined multilingual corpus (denoted as “Mixed”).

4.1. Performance on the Combined Multilingual Dataset

We begin with an overview of model performance on the “Mixed” multilingual corpus, where each model was evaluated based on its ability to generalize across five languages. As shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5, ChatGPT (version GPT-4o) LLM achieved the highest F1-score (0.86), outperforming SetFit MiniLM-L12-v2 (0.85), the traditional Neural Network (0.82), and fine-tuned mBERT (0.81). This highlights the strong zero-shot multilingual generalization capabilities of modern LLMs without requiring task-specific fine-tuning. In

Table 4 and

Table 5, the best performance metric in each column is highlighted in bold, whereas the second-best is underlined.

As expected, traditional ML classifiers (e.g., Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, Neural Networks) achieved lower performance overall, especially in terms of recall, which negatively impacted their F1-scores. Nevertheless, their inclusion provides useful baselines for evaluating the gains achieved by modern transformer-based and LLM approaches.

These findings confirm that LLMs, such as ChatGPT (version GPT-4o), can serve as reliable multilingual classifiers, even in challenging contexts, and demonstrate state-of-the-art performance across both high-resource and low-resource languages.

4.2. Per-Language Results

This section presents a detailed per-language performance comparison between four model categories: traditional ML classifiers (Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, Neural Network), SetFit few-shot sentence embedding models, the multilingual transformer mBERT, and a zero-shot LLM approach using ChatGPT (version GPT-4o).

Among traditional ML classifiers, only the best-performing model per language is included in each table for clarity and brevity. The ChatGPT-based classification was conducted via prompting: each message was fed to the model with a simple binary labeling instruction (“Is this message related to irregular migration?”). No fine-tuning or training was involved.

To enable a fair comparison with the zero-shot LLM evaluation, a manually labeled evaluation subset of 50 messages per language (25 related, 25 unrelated) was constructed. The messages were sampled from the translated dataset to match the original label distribution and thematic diversity. While this subset differs from the train-test splits used in supervised models, it ensures consistent cross-lingual comparison in a controlled and interpretable setup. This approach aligns with prior LLM evaluation protocols in low-resource settings, where labeled data is scarce.

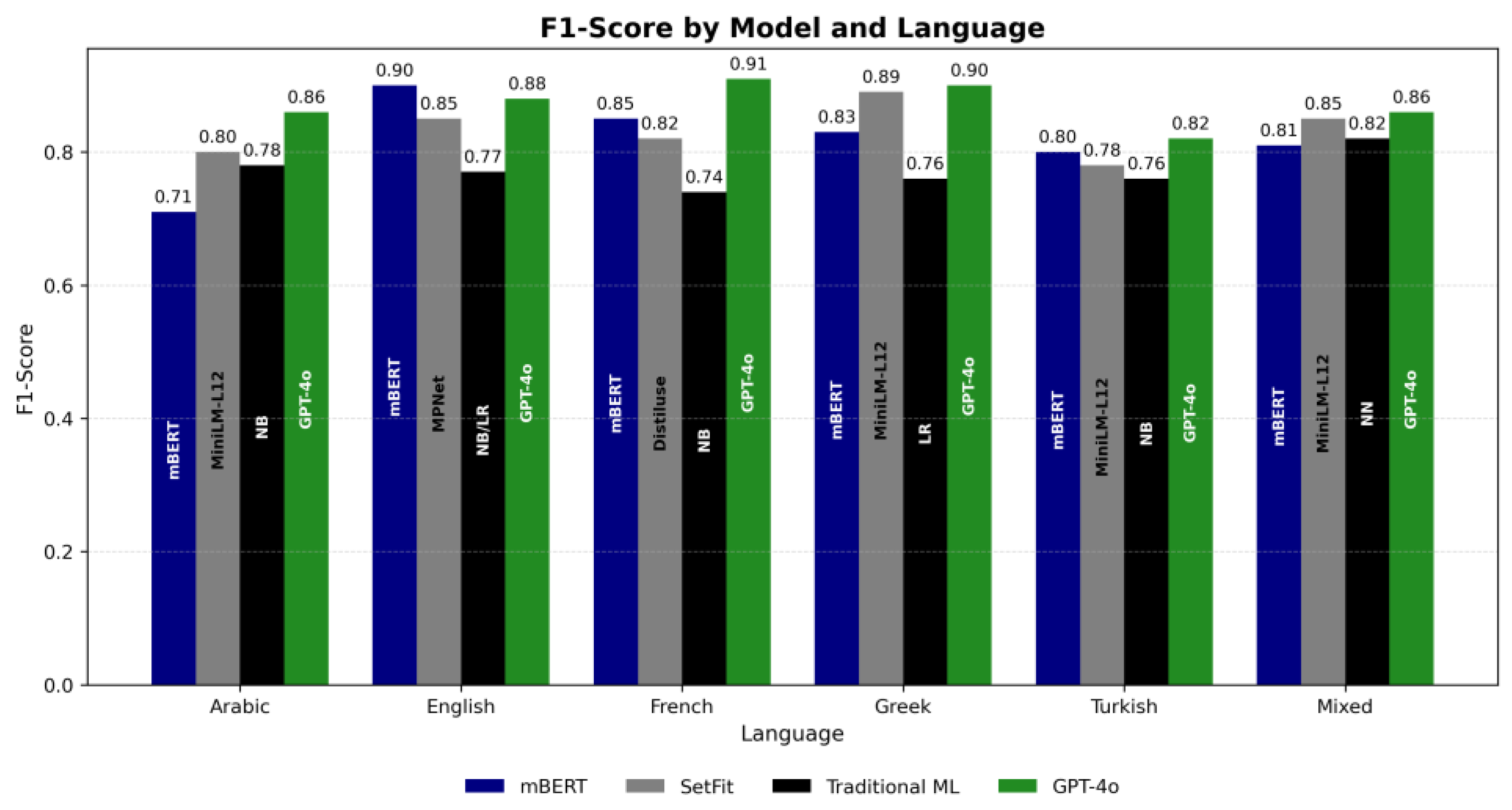

In the subsequent language-specific evaluations, ChatGPT (version GPT-4o) achieved the best F1-score in four out of five individual languages: French (0.91), Greek (0.90), English (0.88), and Arabic (0.86), and shared top performance in Turkish (0.82). These results indicate that LLMs can successfully handle diverse linguistic structures, even in low-resource or morphologically rich languages.

SetFit also performed competitively, particularly in Greek and Arabic, and maintained consistent results across all languages. mBERT showed strong performance in English and French, but its results were less robust in languages like Arabic and Turkish, possibly due to morphological challenges and limited original training data for those languages.

In the English subset, mBERT achieved the highest F1-score (0.90), followed closely by ChatGPT (version GPT-4o) (0.88) and SetFit (0.85), as presented in Table 6. Both LLM and transformer models significantly outperformed traditional classifiers.

In the French subset, as presented in Table 7, ChatGPT outperformed all other models, reaching an F1-score of 0.91, with excellent recall. mBERT (0.85) and SetFit (0.82) also performed well, while Naive Bayes remained behind.

In Arabic, ChatGPT again led with an F1-score of 0.86, outperforming SetFit (0.80) and mBERT (0.71), as presented in Table 8. Despite Arabic’s morphological richness, ChatGPT showed strong generalization in this zero-shot setting.

In Turkish, ChatGPT delivered the best performance (0.82), slightly above mBERT (0.80) and SetFit (0.78), as presented in Table 9. This suggests that LLMs can handle agglutinative languages well in multilingual zero-shot tasks.

In the Greek subset, ChatGPT reached an F1-score of 0.90, narrowly surpassing SetFit (0.89) and mBERT (0.83), as presented in Table 10. Despite Greek being a low-resource language in NLP, the LLM performed exceptionally well.

This comprehensive evaluation shows that zero-shot prompting with ChatGPT is a powerful alternative to supervised training and fine-tuning, particularly when labeled data is scarce or unavailable across languages. In

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10, the best performance metric in each column is highlighted in bold, whereas the second-best is underlined.

4.3. Key Observations

Figure 2 illustrates the comparative performance (F1-score) of all evaluated models, Traditional ML, SetFit, mBERT, and ChatGPT LLM (version GPT-4o), across each language and the multilingual corpus. Several key observations emerge:

ChatGPT (LLM) achieved the highest F1-score in four out of five individual languages (French, Greek, English, Arabic) and on the Mixed corpus, confirming its strong zero-shot generalization capabilities in multilingual and low-resource contexts. It consistently demonstrated high recall, especially in French (0.96) and English (0.92), indicating strong sensitivity in detecting migration-related messages.

SetFit performed competitively, particularly in Greek and Arabic, where it closely matched or slightly trailed ChatGPT. Its few-shot learning structure and pretrained sentence embeddings enabled reliable performance even with small datasets.

mBERT showed strong results in high-resource languages (English, French) but underperformed in Arabic, likely due to morphological complexity and pretraining limitations. It was also outperformed by ChatGPT on the “Mixed” corpus.

Traditional ML models (Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, Neural Network) were consistently outperformed across all settings, particularly due to lower precision or low recall, which limited their F1-scores despite being fast and interpretable.

Random oversampling was effective in correcting minor class imbalance in English and French, improving recall and F1-score for traditional models in those subsets.

Language-specific preprocessing, such as diacritic normalization in Greek, was applied to enhance text consistency and may have contributed to improved performance, particularly for rule-based and embedding-based models.

These findings suggest that LLMs like ChatGPT offer a scalable, training-free alternative for multilingual content classification tasks, especially in low-resource environments where annotated data is limited or expensive to obtain.

5. Discussion

In this section, we reflect on the thematic keyword classification proposed in

Section 3.2 and its implications for multilingual discourse analysis on irregular migration.

A preliminary breakdown of the positively labeled messages by thematic category (as shown in

Table 11) reveals that “Migration,” “Smuggling,” and “Border” dominate across languages, with “Smuggling” more prominent in Arabic and Turkish content. This suggests potential variation in discourse framing across linguistic communities. This categorization enables a more granular understanding of the types of migration-related narratives that appear across platforms and languages.

The grouping of 31 multilingual keywords into 13 thematic categories, such as Migration, Smuggling, Transport, Border, Victims, and Authorities, offers a mid-level abstraction that bridges raw lexical indicators and high-level semantic interpretations. This structure facilitates not only improved interpretability of the annotation schema but also supports comparative linguistic analysis across languages. For instance, one could examine whether certain themes (e.g., “Smuggling” or “Victims”) are overrepresented in specific language communities or platforms, which may reveal culturally-embedded framing patterns or targeted propaganda.

This trend is further illustrated in the aggregated keyword-category distribution. The aggregated keyword-category distribution highlights this trend. Preliminary distributional analysis shows that “Migration,” “Border,” and “Smuggling” were the most frequent categories associated with positive labels (i.e., messages deemed relevant to irregular migration). This indicates that OSN discourse often concentrates around border control and criminal framing. Future studies could explore the correlation between thematic category distribution and sentiment, stance, or bot activity, deeper insight into how migration is framed across languages and platforms.

Furthermore, this thematic taxonomy paves the way for future work on fine-grained or multi-label classification of migration-related discourse. While the present study focuses on binary relevance detection, integrating thematic classes could enable a more nuanced classification system capable of distinguishing between different narrative intents (e.g., humanitarian, securitized, or criminalized framings). This approach could also assist policymakers, media monitors, or NGOs in identifying shifts in public discourse and in detecting coordinated campaigns in specific thematic areas.

Finally, such mid-level categorization supports explainability in ML pipelines by providing a conceptual scaffold for interpreting model predictions. This aligns with the growing need for interpretable AI in sensitive domains like migration and security.

To support interpretability and transparency, each of the 31 multilingual keywords was manually assigned to one of 13 thematic categories based on semantic similarity and relevance to the irregular migration context. This grouping was carried out through an iterative labeling process, informed by prior literature on migration narratives, policy frameworks, and manual validation from bilingual coders. Categories such as “Smuggling,” “Border,” “Victims,” and “Authorities” were chosen to reflect core dimensions of migration discourse, both in media and institutional communication.

While the results are promising, this study has certain limitations. First, the annotated dataset remains relatively small, particularly for languages like Greek and Turkish, which may constrain model generalization. Second, keyword-based rule annotation, although validated, may miss nuanced references to migration discourse, especially in informal or sarcastic language. Third, automatic translation was used to generate multilingual instances, which may introduce semantic drift in some cases. Finally, the evaluation of ChatGPT relied on prompting and manual scoring, which, although controlled, could be complemented by larger-scale, user-agnostic benchmarking in future research.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study builds upon our previous work [

1] by proposing a multilingual NLP framework for detecting irregular migration-related discourse across two widely used platforms: X and Telegram. Our main contributions include the integration of rule-based keyword annotation, language-specific preprocessing pipelines, and comparative benchmarking of four model families: traditional ML classifiers (Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, Neural Networks), transformer-based models (SetFit and mBERT), and general-purpose LLMs, such as ChatGPT. Importantly, we incorporated underrepresented languages (Greek, Turkish, Arabic), as well as Telegram data, which remains underexplored in computational social science despite its growing relevance for decentralized communication in migration contexts.

A key contribution of this work is the empirical demonstration that transformer-based approaches outperform traditional ML methods across all evaluated settings. Fine-tuned mBERT performed best in high-resource languages such as English and French, while SetFit showed superior performance in low-resource settings including Arabic and Greek. The ChatGPT (version GPT-4o) based classification yielded the highest F1-scores overall, reaching 0.91 in French, 0.90 in Greek, and 0.86 in Arabic, highlighting the feasibility of using prompt-based LLMs in multilingual discourse classification without supervised fine-tuning.

Looking forward, future research may focus on enriching the multilingual corpus with additional underrepresented languages and regional dialects, especially from key migration corridors. There is also scope to experiment with large multilingual foundation models such as XLM-RoBERTa or mT5, and to explore few-shot or zero-shot classification scenarios using in-context learning. Moreover, forging collaborations with institutional actors such as FRONTEX or the European Union Asylum Support Office could support the operational deployment of this framework in applications like early warning systems and strategic communication monitoring.

By addressing both methodological and empirical gaps, this study lays the groundwork for more inclusive and linguistically diverse research on irregular migration discourse and supports scalable NLP applications in multilingual crisis informatics.

Overall, this work offers a robust multilingual NLP foundation for detecting migration-related narratives across diverse platforms and languages, and holds promise for operational deployment in early warning systems, strategic communication monitoring, and policy response mechanisms across the EU and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D. Taranis, G. Razis and I. Anagnostopoulos; methodology, D. Taranis and G. Razis; software, D. Taranis; validation, G. Razis and I. Anagnostopoulos; formal analysis, D. Taranis; investigation, D. Taranis; resources, G. Razis and I. Anagnostopoulos; data curation, D. Taranis; writing—original draft preparation, D. Taranis; writing—review and editing, G. Razis and I. Anagnostopoulos; visualization, D. Taranis; supervision, G. Razis and I. Anagnostopoulos; project administration, D. Taranis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study cannot be shared publicly due to platform restrictions and privacy obligations associated with X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram. Processed datasets and analysis code are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, version GPT-4o, accessed July 2025) exclusively as a zero-shot large language model baseline in the experimental evaluation (Section 4). All manuscript text, analysis, and figures were produced independently by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| BERT |

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| EU |

European Union |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| LLMs |

Large Language Models |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| mBERT |

Multilingual Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| NLTK |

Natural Language Toolkit |

| OSN |

Online Social Network |

| OSNs |

Online Social Networks |

| TF-IDF |

Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency |

| X |

X (formerly Twitter) |

References

- Taranis, D.; Razis, G.; Anagnostopoulos, I. Immigration Detection in Multilanguage Tweets Using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. AIAI 2025; Maglogiannis, I., Iliadis, L., Andreou, A., Papaleonidas, A., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 757, pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle-Cano, G.; Quijano-Sanchez, L. SocialHaterBERT: Dichotomous Detection of Hate Speech. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 216, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Kumar, S.; Samant, S.S. Hate Speech Detection in Social Media: Techniques, Recent Trends, and Future Challenges. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2024, 16, e1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnassri, K.; Farahbakhsh, R.; Crespi, N. Multilingual Hate Speech Detection: A Semi-Supervised Generative Adversarial Approach. Entropy 2024, 26, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.A. A Study on Illegal Immigration into North-East India: The Case of Nagaland. IDSA Occasional Paper No. 8; Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses: New Delhi, India, 2009. Available online: http://eprints.nias.res.in/150/1/A_Study_on_Illegal_Immigration_into_North-East_India_The_Case_of_Nagaland.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Garibo i Orts, Ó. Multilingual Detection of Hate Speech against Immigrants and Women in Twitter at SemEval-2019 Task 5: Frequency Analysis Interpolation for Hate Speech Detection. In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2019), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 6–7 June 2019; pp. 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitropakis, N.; Kokot, K.; Gkatzia, D.; Ludwiniak, R.; Pitropakis, N. Monitoring Users’ Behavior: Anti-Immigration Speech Detection on Twitter. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2020, 2, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Bosco, C.; Fersini, E.; Nozza, D.; Patti, V.; Rangel Pardo, F.M.; Rosso, P.; Sanguinetti, M. SemEval-2019 Task 5: Multilingual Detection of Hate Speech against Immigrants and Women in Twitter. In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2019), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 6–7 June 2019; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT 2019), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nazi, Z.; Hossain, M.R.; Al Mamun, F. Evaluation of Open- and Closed-Source LLMs for Low-Resource Language with Zero-Shot, Few-Shot and Chain-of-Thought Prompting. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2025, 10, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French Bourgeois, L.; Esses, V.M. Using Twitter to Investigate Discourse on Immigration: The Role of Values in Expressing Polarized Attitudes toward Asylum Seekers during the Closure of Roxham Road. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 2, 1376647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Y.; Balakrishnan, V. An Enhanced Lexicon-Based Approach for Sentiment Analysis: A Case Study on Illegal Immigration. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 1097–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, F.; Mahony, M.; Graells-Garrido, E.; Rango, M.; Sievers, N. Using Twitter to Track Immigration Sentiment during Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Data Policy 2021, 3, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, R.; Popescu, M. Migration Reframed? In A Multilingual Analysis of Stance and Sentiment in European News. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023 (WWW ’23), Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 2893–2903. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.02813 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Papageorgiou, E.; Chronis, C.; Varlamis, I.; Himeur, Y. A Survey on the Use of Large Language Models (LLMs) in Fake News. Future Internet 2024, 16, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, F.T.J.; Baniata, L.H.; Kang, S. Investigating the Predominance of Large Language Models in Low-Resource Bangla Language over Transformer Models for Hate Speech Detection: A Comparative Analysis. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.E. Understanding Inverse Document Frequency: On Theoretical Arguments for IDF. J. Doc. 2004, 60, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsar, J.; Curk, T.; Erjavec, A.; Gorup, C.; Hocevar, T.; Milutinovic, M.; Mozina, M.; Polajnar, M.; Toplak, M.; Staric, A.; Stajdohar, M.; Umek, L.; Žagar, L.; Zbontar, J.; Žitnik, M.; Zupan, B. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013, 14, 2349–2353. Available online: http://jmlr.org/papers/v14/demsar13a.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- X (Developer). X API Documentation. n.d. Available online: https://developer.x.com/en/docs/x-api (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Mimino Danilák, M. langdetect [Python Library]. n.d. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/langdetect/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Bird, S.; Klein, E.; Loper, E. Natural Language Processing with Python; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.nltk.org (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: A Lexical Database for English. Commun. ACM 1995, 38, 39–41. Available online: https://wordnet.princeton.edu/ (accessed on 17 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.F. Snowball: A Language for Stemming Algorithms. 2001. Available online: https://snowballstem.org/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Tunstall, L.; Reimers, N.; Seo, U.J.E.; Bates, L.; Korat, D.; Wasserblat, M.; Pereg, O. Efficient Few-Shot Learning without Prompts (SetFit). arXiv arXiv:2209.11055, 2022. [CrossRef]

- HuggingFace. all-MiniLM-L12-v2 [Model]. n.d.a. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L12-v2 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- HuggingFace. all-MiniLM-L6-v2 [Model]. n.d.b. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- HuggingFace. paraphrase-mpnet-base-v2 [Model]. n.d.c. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/paraphrase-mpnet-base-v2 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).