Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Those who identify as both religious and spiritual (RAS) will have the best mental health (i.e., the lowest levels of depression and anxiety) as compared with those who are Spiritual but not Religious (SBNR), Religious but not Spiritual (RBNS), or Neither Spiritual nor Religious (NSNR).

- Those who are neither religious nor spiritual (NRNS) will have the worst mental health.

- Those who identify as either religious but not spiritual (RBNS), or spiritual but not religious (SBNR) will demonstrate levels of mental health between their two counterparts.

- Identifying as Spiritual but not Religious may be detrimental to mental well-being.

2. Results

2.1. Demographics

2.2. Baseline Depression/Anxiety Levels

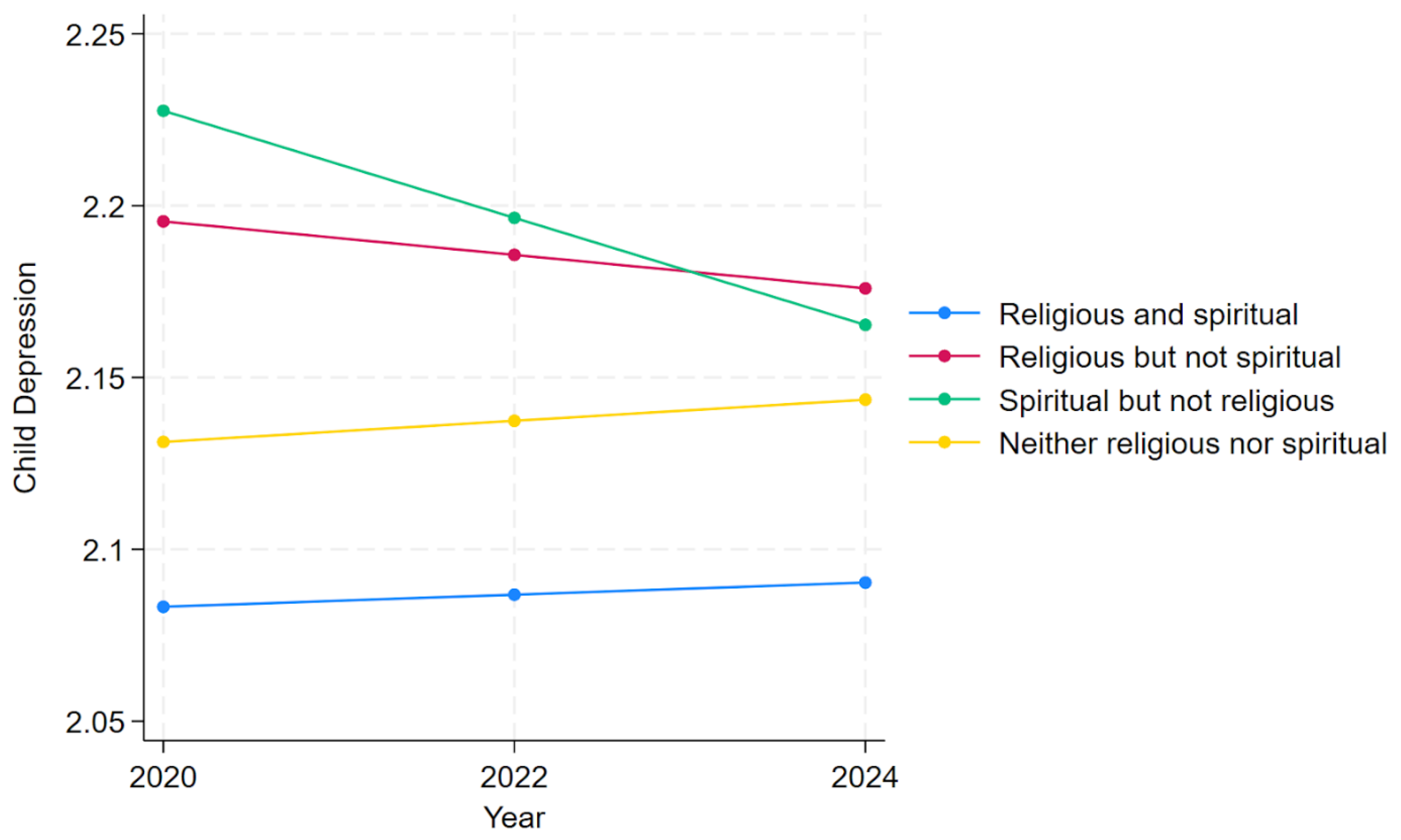

2.3. Child Depression Over Time

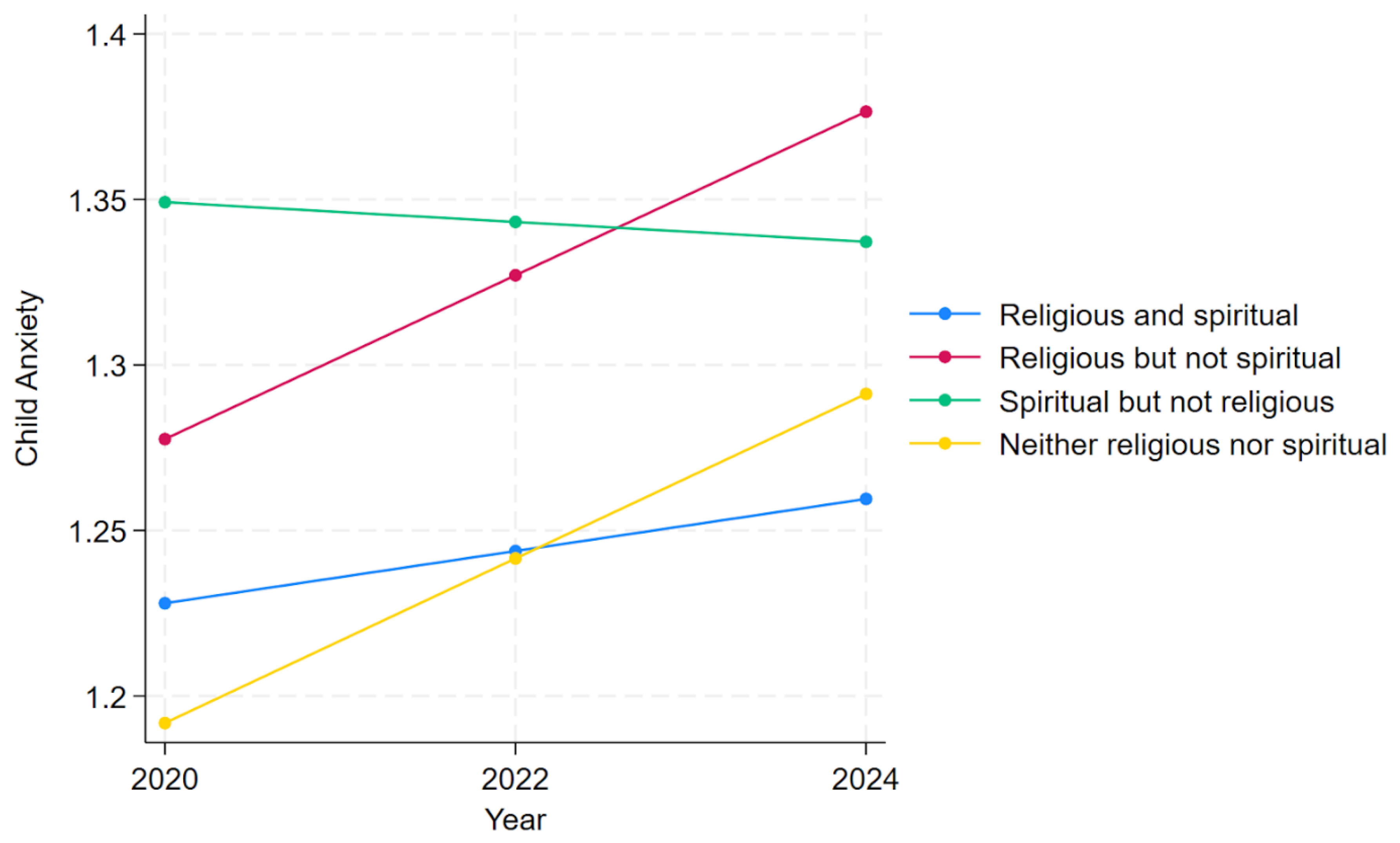

2.4. Child Anxiety Over Time

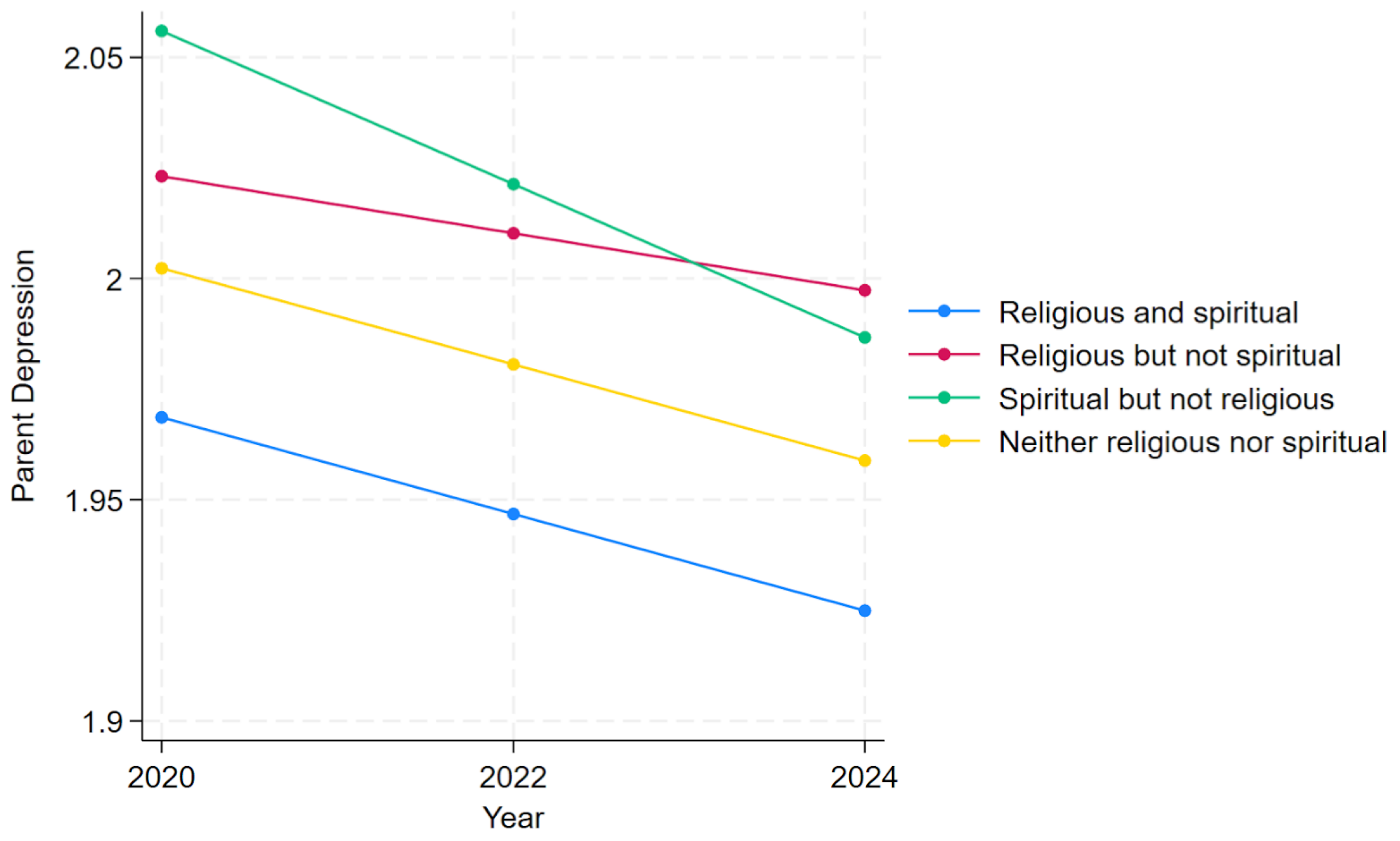

2.5. Parent Depression Over Time

2.6. Parent Anxiety Over Time

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SBNR | Spiritual but Not Religious |

| RBNS | Religious but Not Spiritual |

| RAS | Religious and Spiritual |

| NRNS R/S |

Neither Religious nor Spiritual Religiosity/Spirituality |

References

- Aggarwal, S., J. Wright, A. Morgan, G. Patton, and N. Reavley. 2023. “Religiosity and Spirituality in the Prevention and Management of Depression and Anxiety in Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Psychiatry 23 (1).

- Ai, A. L., C. Peterson, T. N. Tice, B. Huang, W. Rodgers, and S. F. Bolling. 2007. “The Influence of Prayer Coping on Mental Health among Cardiac Surgery Patients: The Role of Optimism and Acute Distress.” Journal of Health Psychology 12 (4): 580–96. [CrossRef]

- Ai, A. L., T. N. Tice, C. Peterson, and B. Huang. 2005. “Prayers, Spiritual Support, and Positive Attitudes in Coping with the September 11 National Crisis.” Journal of Personality 73 (3): 763–91. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Edited by text rev.; DSM-5-TR 5th. American Psychiatric Association. [CrossRef]

- Björgvinsson, T., S. J. Kertz, J. S. Bigda-Peyton, K. L. McCoy, and I. M. Aderka. 2013. “Psychometric Properties of the CES-D-10 in a Psychiatric Sample.” Assessment 20: 429–36.

- Boelens, P. A., R. R. Reeves, W. H. Replogle, and H. G. Koenig. 2009. “A Randomized Trial of the Effect of Prayer on Depression and Anxiety.” International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 39 (4): 377–92. [CrossRef]

- Boelens, P. A., R. R. Reeves, W. H. Replogle, and H. G. Koenig. 2012. “The Effect of Prayer on Depression and Anxiety: Maintenance of Positive Influence One Year after Prayer Intervention.” International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 43 (1): 85–98. [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, R., R. E. Dew, H. G. Koenig, D. H. Rosmarin, and S. Vasegh. 2012. “Religious and Spiritual Factors in Depression: Review and Integration of the Research.” Depression Research and Treatment 2012: 96286. [CrossRef]

- Brody, Debra, and Jeffery Hughes. 2025. Prevalence of Depression in Adolescents and Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). [CrossRef]

- Burge, Ryan P. 2021. The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going. Fortress Press. [CrossRef]

- Burns, D. D. 1989. The Feeling Good Handbook. William Morrow & Co.

- Byrd, K. R., and A. Boe. 2001. “The Correspondence between Attachment Dimensions and Prayer in College Students.” International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 11 (1): 9–24. [CrossRef]

- Captari, L. E., J. N. Hook, W. Hoyt, D. E. Davis, S. E. McElroy-Heltzel, and E. L. Worthington Jr. 2018. “Integrating Clients’ Religion and Spirituality within Psychotherapy: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 74 (11): 1938–51. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L. K., and M. F. Steger. 2010. “Race and Religion: Differential Prediction of Anxiety Symptoms by Religious Coping in African American and European American Young Adults.” Depression and Anxiety 27 (3): 316–22. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ying, Eric S Kim, and Tyler J VanderWeele. 2020. “Religious-Service Attendance and Subsequent Health and Well-Being throughout Adulthood: Evidence from Three Prospective Cohorts.” International Journal of Epidemiology 49 (6): 2030–40. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, Andrea, Toshi A Furukawa, Georgia Salanti, et al. 2018. “Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of 21 Antidepressant Drugs for the Acute Treatment of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet 391 (10128): 1357–66. [CrossRef]

- Cloninger, C. R. 2006. “The Science of Well-Being: An Integrated Approach to Mental Health and Its Disorders.” World Psychiatry 5 (2): 71–76.

- Dehghani, K. H., R. A. Zare, Z. Pourmovahed, H. Dehghani, A. Zarezadeh, and Z. Namjou. 2012. “The Effect of Prayer on Level of Anxiety in Mothers of Children with Cancer.” [Journal Not Specified].

- Ellison, C. G., A. M. Burdette, and T. D. Hill. 2009. “Blessed Assurance: Religion, Anxiety, and Tranquility among US Adults.” Social Science Research 38 (3): 656–67. [CrossRef]

- Flannelly, K. J., K. Galek, C. G. Ellison, and H. G. Koenig. 2010. “Beliefs about God, Psychiatric Symptoms, and Evolutionary Psychiatry.” Journal of Religion and Health 49 (2): 246–61. [CrossRef]

- Foley, E., A. Baillie, M. Huxter, M. Price, and E. Sinclair. 2010. “Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Individuals Whose Lives Have Been Affected by Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78 (1): 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Ford, K., and F. Garzon. 2017. “Research Note: A Randomized Investigation of Evangelical Christian Accommodative Mindfulness.” Spirituality in Clinical Practice 4 (2): 92–92.

- Harber, Ian. 2024. “TikTok: Now Serving Deconstruction.” Endeavor With Us, September 4. https://www.endeavorwithus.com/deconstructing-faith-on-tiktok.

- Hasin, D. S., A. L. Sarvet, and J. L. Meyers. 2018. “Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States.” JAMA Psychiatry 75 (4): 336–46. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K., R. Motley, and J. Hovey. 2010. “Anxiety, Depression and Students’ Religiosity.” Mental Health, Religion & Culture 13 (3): 267–71. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I. J. 2019. “Spirituality and Religion: Relevance and Assessment in the Clinical Setting.” Current Psychiatry Research and Reviews 15 (2): 80–87.

- King, M. 2014. “The Challenge of Research into Religion and Spirituality Keynote1Keynote1.” Journal for the Study of Spirituality 4 (2): 106–20. [CrossRef]

- King, Michael, Louise Marston, Sally McManus, Terry Brugha, Howard Meltzer, and Paul Bebbington. 2013. “Religion, Spirituality and Mental Health: Results from a National Study of English Households.” British Journal of Psychiatry 202 (1): 68–73. [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H. G., L. S. Berk, N. S. Daher, et al. 2014. “Religious Involvement Is Associated with Greater Purpose, Optimism, Generosity and Gratitude in Persons with Major Depression and Chronic Medical Illness.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 77 (2): 135–43. [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H. G., L. K. George, D. G. Blazer, and J. T. Pritchett. 1993. “The Relationship between Religion and Anxiety in a Sample of Community-Dwelling Older Adults.” Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 26 (1): 65–93.

- Koenig, H. G., D. E. King, and V. B. Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford University Press.

- Koenig, H. G., T. VanderWeele, and J. R. Peteet. 2023. Handbook of Religion and Health. Edited by 3. Oxford University Press.

- Koenig, Harold G. 2008. “Concerns About Measuring ‘Spirituality’ in Research.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 196 (5): 349–55. [CrossRef]

- Koszycki, D., K. Raab, F. Aldosary, and J. Bradwejn. 2010. “A Multifaith Spiritually Based Intervention for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Pilot Randomized Trial.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 66 (4): 430–41. [CrossRef]

- Koukl, Greg. 2022. “Social Media Has Amplified Deconstruction.” Stand to Reason, November 14. https://www.str.org/w/social-media-has-amplified-deconstruction.

- Li, S., O. I. Okereke, S. C. Chang, I. Kawachi, and T. J. VanderWeele. 2016. “Religious Service Attendance and Lower Depression among Women: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 50 (6): 876–84. [CrossRef]

- Little, Todd D. 2024. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Publications.

- McConnell, K. M., K. I. Pargament, C. G. Ellison, and K. J. Flannelly. 2006. “Examining the Links between Spiritual Struggles and Symptoms of Psychopathology in a National Sample.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 62 (12): 1469–84. [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Almeida, A., F. L. Neto, and H. G. Koenig. 2006. “Religiousness and Mental Health: A Review.” Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 28 (3): 242–50. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Mental Health. 2021. “Anxiety Disorders.” National Institute of Mental Health, June. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/anxiety-disorders.

- National Institute of Mental Health. 2022. “Major Depression.” National Institute of Mental Health, June. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.

- Ng, G. C., S. Mohamed, A. H. Sulaiman, and N. Z. Zainal. 2017. “Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Patients: The Association with Religiosity and Religious Coping.” Journal of Religion and Health 56 (2): 575–90. [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, M., K. Solati, S. Heidari Soureshjani, et al. 2018. “Effect of Group Religious Intervention on Spiritual Health and Reduction of Symptoms in Patients with Anxiety.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 12 (11): VC06–9. [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K. I., H. G. Koenig, N. Tarakeshwar, and J. Hahn. 2004. “Religious Coping Methods as Predictors of Psychological, Physical and Spiritual Outcomes among Medically Ill Elderly Patients: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Health Psychology 9 (6): 713–30. [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K. I., and J. W. Lomax. 2013. “Understanding and Addressing Religion among People with Mental Illness.” World Psychiatry 12 (1): 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Paukert, A. L., L. Phillips, J. A. Cully, S. M. Loboprabhu, J. W. Lomax, and M. A. Stanley. 2009. “Integration of Religion into Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Geriatric Anxiety and Depression.” Journal of Psychiatric Practice 15 (2): 103–12. [CrossRef]

- Peterman, J., D. R. LaBelle, and L. Steinberg. 2014. “Devoutly Anxious: The Relationship between Anxiety and Religiosity in Adolescence.” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6 (2): 113–22. [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2023. Spirituality among Americans. Religion & Public Life Project. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2023/12/07/spirituality-among-americans/.

- Ramirez, S. P., D. S. Macêdo, P. M. Sales, et al. 2012. “The Relationship between Religious Coping, Psychological Distress and Quality of Life in Hemodialysis Patients.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 72 (2): 129–35. [CrossRef]

- Razali, S. M., C. I. Hasanah, K. Aminah, and M. Subramaniam. 1998. “Religious—Sociocultural Psychotherapy in Patients with Anxiety and Depression.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 32 (6): 867–72.

- Rosmarin, D. H., J. S. Bigda-Peyton, D. Öngur, K. I. Pargament, and T. Björgvinsson. 2013. “Religious Coping among Psychotic Patients: Relevance to Suicidality and Treatment Outcomes.” Psychiatry Research 210 (1): 182–87. [CrossRef]

- Rosmarin, D. H., and H. G. Koenig. 2020. Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health. Edited by 2. Academic Press.

- Rosmarin, D. H., E. J. Krumrei, and G. Andersson. 2009. “Religion as a Predictor of Psychological Distress in Two Religious Communities.” Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 38 (1): 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Rosmarin, D. H., K. I. Pargament, S. Pirutinsky, and A. Mahoney. 2010. “A Randomized Controlled Evaluation of a Spiritually Integrated Treatment for Subclinical Anxiety in the Jewish Community, Delivered via the Internet.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 24 (7): 799–808. [CrossRef]

- Sappenfield, Olivia, Cinthyia Alberto, Jessica Minnaert, Julie Donney, Lydie Lebrun-Harris, and Reem Ghandour. n.d. Adolescent Mental and Behavioral Health, 2023. National Survey of Children’s Health Data Briefs [Internet]. Health Resources & Services Administration. Accessed October 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK608531/.

- Schaefer, C. A., and R. L. Gorsuch. 1991. “Psychological Adjustment and Religiousness: The Multivariate Belief-Motivation Theory of Religiousness.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30 (4): 448–61. [CrossRef]

- Schieman, S., T. Pudrovska, L. I. Pearlin, and C. G. Ellison. 2006. “The Sense of Divine Control and Psychological Distress: Variations across Race and Socioeconomic Status.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45 (4): 529–49. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, A. C., T. G. Plante, S. Simonton, U. Latif, and E. J. Anaissie. 2009. “Prospective Study of Religious Coping among Patients Undergoing Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32 (1): 118–28. [CrossRef]

- Silton, N. R., K. J. Flannelly, K. Galek, and C. G. Ellison. 2014. “Beliefs about God and Mental Health among American Adults.” Journal of Religion and Health 53 (5): 1285–96. [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian. 2025. Why Religion Went Obsolete. Oxford University Press.

- Sternthal, M. J., D. R. Williams, M. A. Musick, and A. C. Buck. 2010. “Depression, Anxiety, and Religious Life: A Search for Mediators.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51 (3): 343–59. [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, E. P., and B. Zablotsky. 2024. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among Adults: United States, 2019 and 2022. National Health Statistics Reports, no. 213. [CrossRef]

- Trenholm, P., J. Trent, and W. C. Compton. 1998. “Negative Religious Conflict as a Predictor of Panic Disorder.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 54 (1): 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, G. E. 2013. “Psychiatry, Religion, Positive Emotions and Spirituality.” Asian Journal of Psychiatry 6 (6): 590–94. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, A. R. T., E. Castro-Costa, J. d. O. A. Firmo, M. F. Lima-Costa, and A. I. d. Loyoola Filho. 2018. “Religiousness, Social Support and the Use of Antidepressants among the Elderly: A Population-Based Study.” Ciencia & Saude Coletive 23 (3): 963–71. [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, Luciano Magalhães, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Frederico Camelo Leão, Homero Vallada, and Mario Fernando Prieto Peres. 2018. “The Association between Spirituality and Religiousness and Mental Health.” Scientific Reports 8 (1): 17233. [CrossRef]

- Wachholtz, A. B., and K. I. Pargament. 2005. “Is Spirituality a Critical Ingredient of Meditation? Comparing the Effects of Spiritual Meditation, Secular Meditation, and Relaxation on Spiritual, Psychological, Cardiac, and Pain Outcomes.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 28 (4): 369–84. [CrossRef]

- Wachholtz, A. B., and K. I. Pargament. 2008. “Migraines and Meditation: Does Spirituality Matter?” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 31 (4): 351–66. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A. H., M. Gbedemah, A. M. Martinez, D. Nash, S. Galea, and R. D. Goodwin. 2018. “Trends in Depression Prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: Widening Disparities in Vulnerable Groups.” Psychological Medicine 48 (8): 1308–15. [CrossRef]

- Wells, Georgia. 2025. “‘Exmo’ Influencers Mount a TikTok War against the Mormon Church: The Church Is Facing a 21st-Century Reckoning, Driven by Social Media—and It Is Racing to Counter the Narrative.” The Wall Street Journal, September 2. https://www.wsj.com/tech/ex-mormon-tiktok-creators-e9a5b00e.

- Widaman, Keith F., Emilio Ferrer, and Rand D. Conger. 2010. “Factorial Invariance Within Longitudinal Structural Equation Models: Measuring the Same Construct Across Time.” Child Development Perspectives 4 (1): 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Sylia, and Nathalie M. Dumornay. 2022. “Rising Rates of Adolescent Depression in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities in the 2020s.” Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (3): 354–55. [CrossRef]

| Child Depression | Child Anxiety | Parent Depression | Parent Anxiety | |

| Religious and spiritual (RAS) | 2.07All | 1.22SBNR | 1.93RBNS,SBNR | 1.52RBNS,SBNR |

| Religious but not spiritual (RBNS) | 2.17RAS,SBNR | 1.23SBNR | 2.01RAS | 1.64RAS,NRNS |

| Spiritual but not religious (SBNR) | 2.24All | 1.37All | 1.99RAS | 1.61RAS,NRNS |

| Neither religious nor spiritual (NRNS) | 2.13RAS,SBNR | 1.17SBNR | 1.97 | 1.50RBNS,SBNR |

| Child Depression | Child Anxiety | Parent Depression | |

| b(se) | b(se) | b(se) | |

| R/S Groupingsa | |||

| Religious but not spiritual (RBNS) | 0.13(.03)*** | 0.02(.05) | 0.05(.04) |

| Spiritual but not religious (SBNR) | 0.18(.03)*** | 0.14(.05)** | 0.10(.02)*** |

| Neither religious nor spiritual (NRNS) | 0.05(.03) | -0.07(.05) | 0.03(.03) |

| Survey Wave | 0.00(.00) | 0.02(.01)* | -0.02(.00)*** |

| R/S Identification X Wavea | |||

| Religious but not spiritual (RBNS) | -0.01(.01) | 0.03(.02) | 0.01(.01) |

| Spiritual but not religious (SBNR) | -0.03(.01)*** | -0.02(.02) | -0.01(.01)* |

| Neither religious nor spiritual (NRNS) | 0.00(.01) | 0.03(.02)* | 0.00(.01) |

| Male | -0.10(.01)*** | -0.34(.02)*** | -0.01(.02) |

| Income | 0.00(.00)* | 0.00(.00) | -0.01(.00)*** |

| Family Statec | |||

| Arizona | -0.02(.02) | -0.04(.03) | 0.00(.01) |

| California | -0.03(.02) | -0.05(.03) | 0.00(.01) |

| White d | -0.02(.02) | -0.04(.03) | 0.02(.02) |

| Constant | 2.20(.03)*** | 1.45(.04)*** | 2.08(.02)*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).