Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Memory Effect in Spacetime

3. Sanchez’s Quantum Gravity and Conformal Cyclic Cosmology

4. Sanchez’s Quantum Gravity

4.1. Cosmological Constant

4.2. Traces of the Post-Planckian Universe

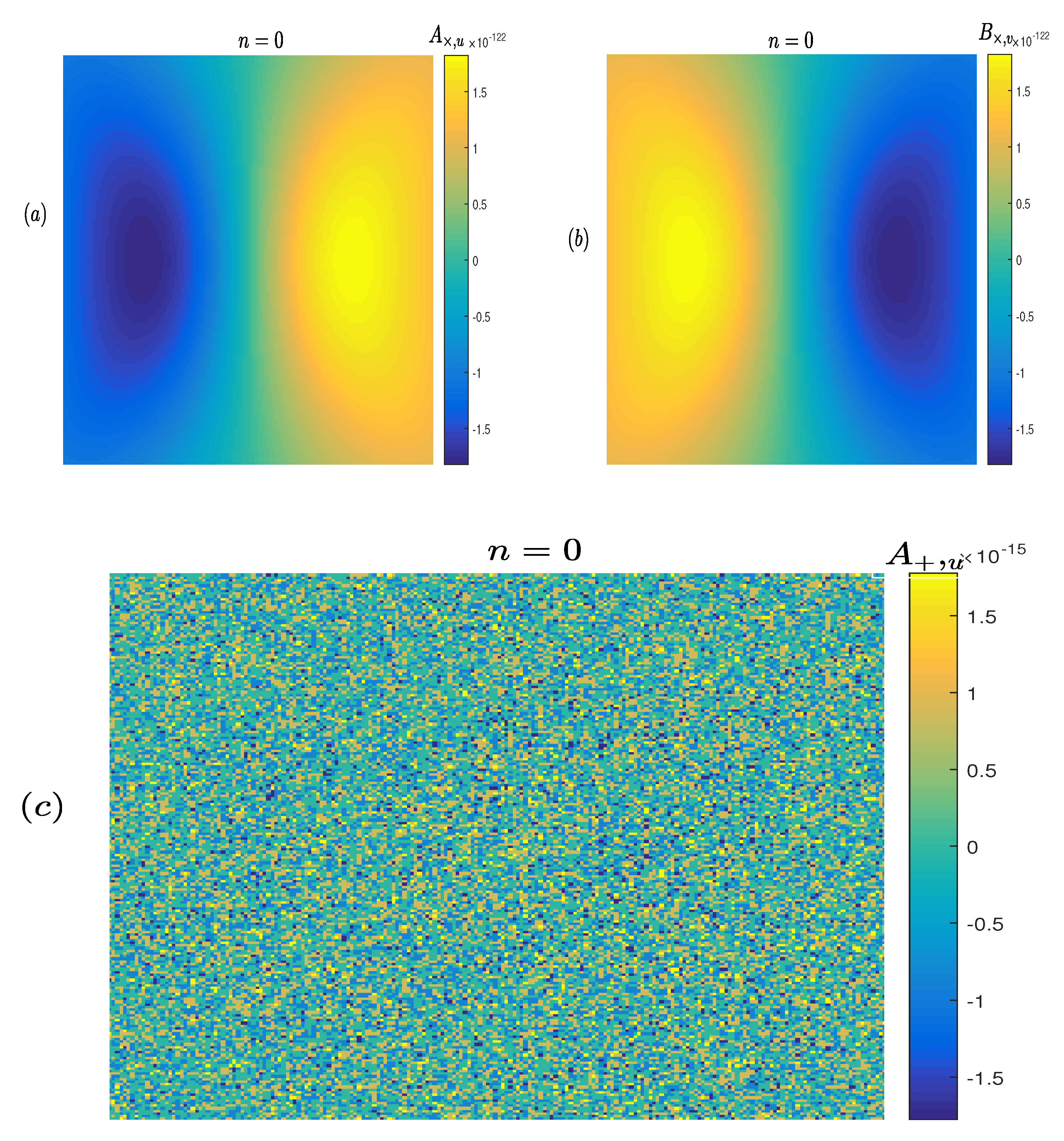

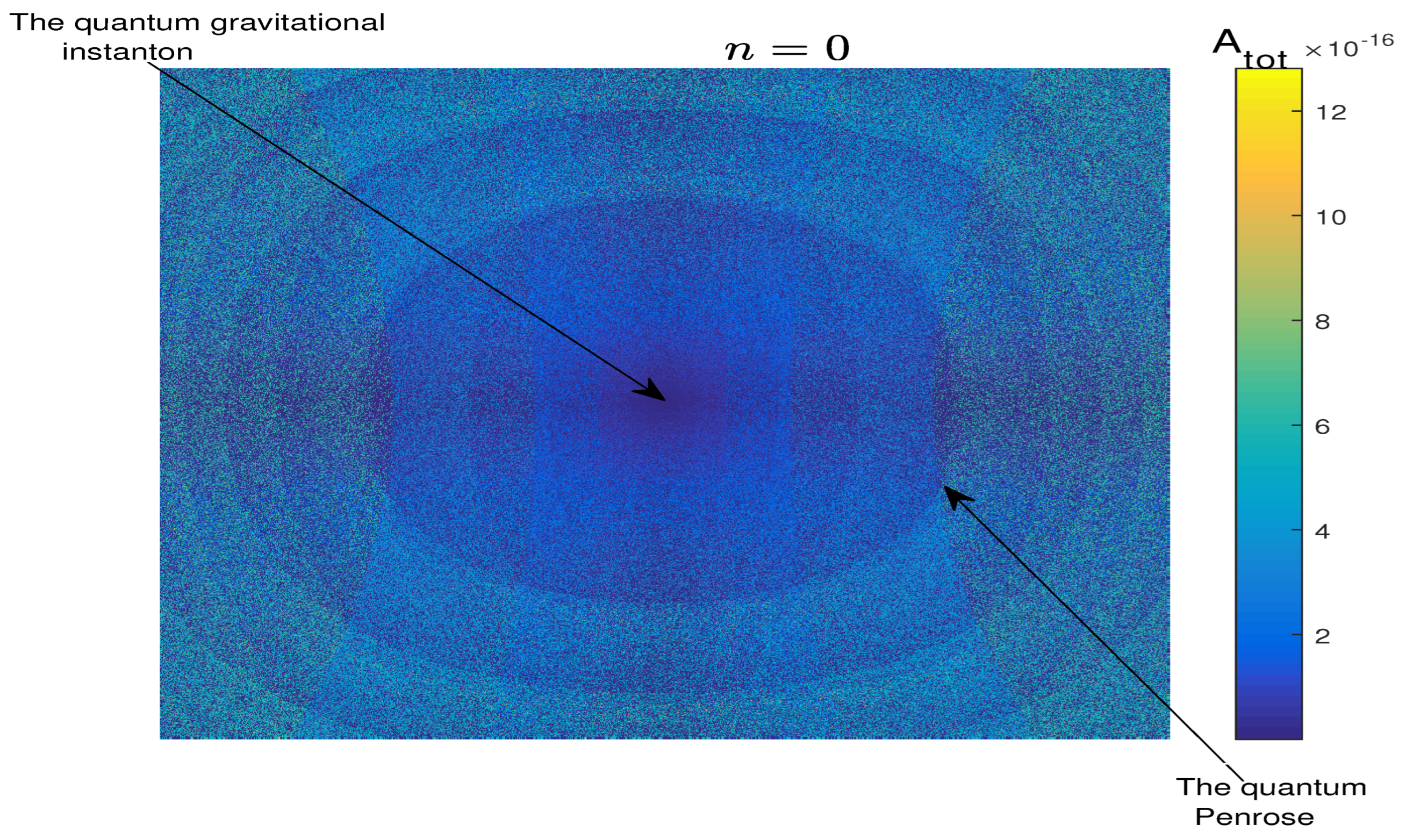

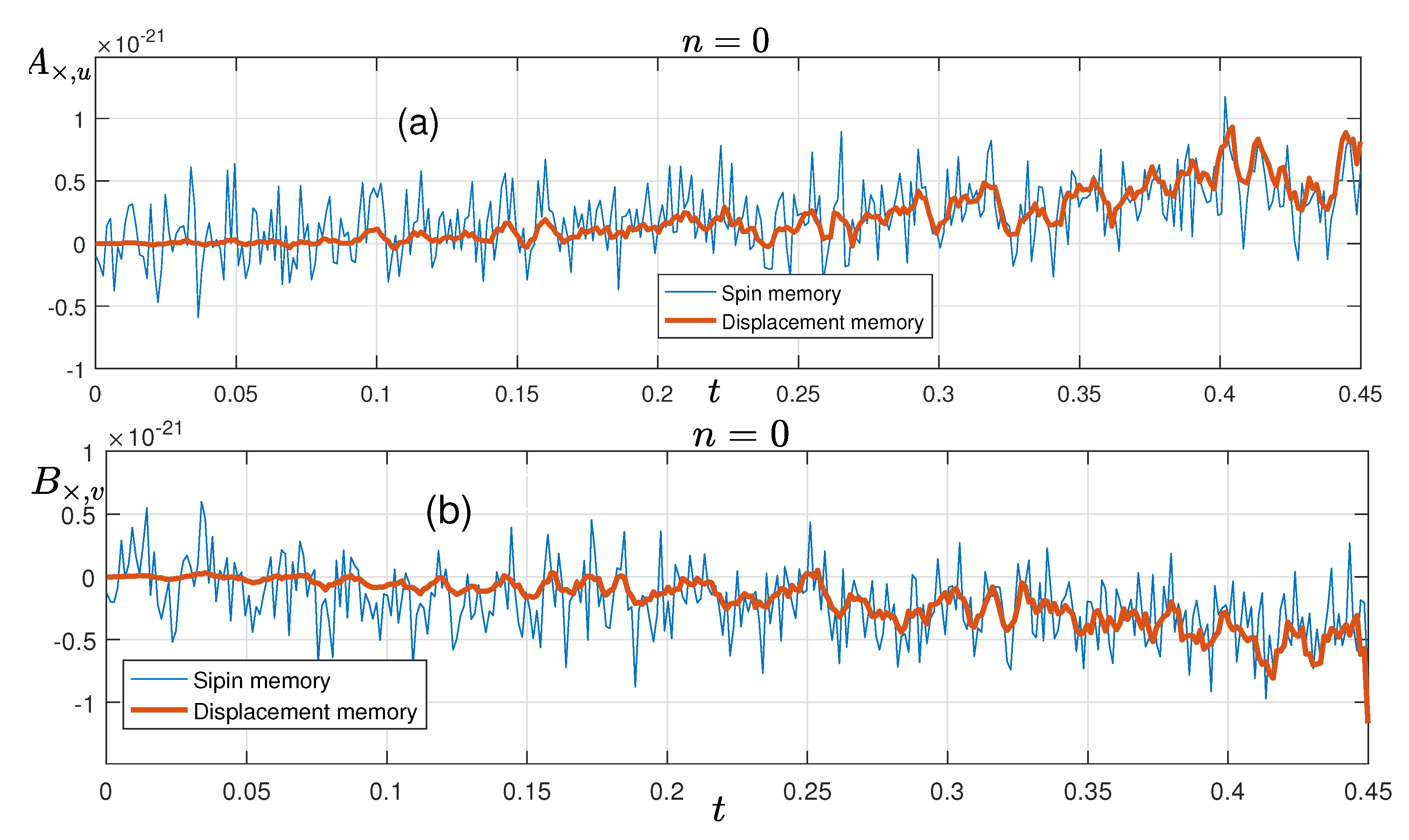

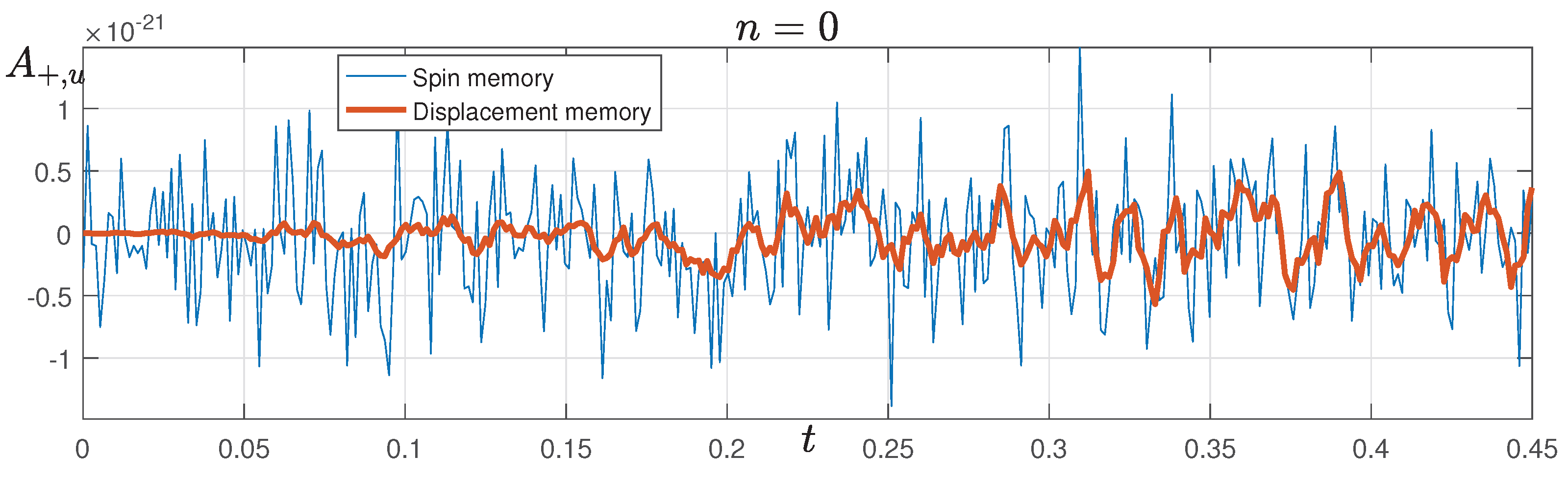

4.3. Gravitational Wave Memory Signal (LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA-LISA)

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- J. Binney, R. J. Binney, R. Mohayaee, J. Peacock and S. Sarka, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 383 20240036 (2025).

- C. arXiv:2111.07828 . arXiv:2111.07828.

- J. Harada, Phys. Rev. D108044031 (2023).

- M. Violaris et al, Nature644867 ( 2025).

- N. Sanchez, Phys. Rev. D107126018 (2023).

- N. Sanchez, Unifying quantum mechanics with Einsteins general relativity.

- N. Sanchez, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D .283 (2019).

- N. Sanchez, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A .3427 (2019).

- N. arXiv:1910.13382v1. arXiv:1910.13382v1.

- N. Sanchez, 10.20944/preprints202411.0679.

- D. An et al, arXiv:1808.01740. arXiv:1808.01740.

- V. Gurzadyan and R. arXiv:1011.3706. arXiv:1011.3706.

- R. Penrose, Found. Phys. 44: 873-890 (2014).

- R. Penrose, Found. Phys. 48: 11771190 (2018).

- Cheung et al, Class. Quantum Grav.41115010 (2024).

- K. Quantum Grav. 41 223001 ( 2024.

- L. Bieri and A. Polnarev, Class. Quantum Grav. 41 135012 (2024).

- A. Grant, Class. Quantum Grav.41175004 (2024).

- A. Sen, Class. Quantum Grav.41143002 (2024).

- F. R. Villatoro, Nonlinear Systems, Vol. 1, Understanding Complex Systems (V. Carmona et al. (eds. 2018.

- M. Parikh, F. M. Parikh, F. Wilczek, and G. arXiv:2005.07211. arXiv:2005.07211.

- R. Roshan and G. White, arXiv:2401. 0438.

- B. Goncharov, L. B. Goncharov, L. Donnay and J. Harms, Phys. Rev. Lett.132 241401 (2024).

- J. Defo and K. Kuetche, arXiv:2506. 1005.

- J. Defo and K. Kuetche, JETP.1353 (2022).

- J. Defo, V. J. Defo, V. Kuetche and T. Bouetou, 10.20944/preprints202508.1276.

- Chakraborty and S. Kar, arXiv:2202.10661. arXiv:2202.10661.

- K. Meissner and R. Penrose, arXiv:2503.24263. arXiv:2503.24263.

- M. Parikh, F. M. Parikh, F. Wilczek, and G. Zahariade, Phys. Rev. Lett 127 081602 (2021).

- S. Hayward, arXiv:gr-qc/0504038.

- S. Hayward, Phys. Rev. Lett96031103 (2006).

- S. Hayward, arXiv:gr-qc/0504037.

- S. Tomizawa and T. Mishima, Phys. Rev. D 91 124058 (2015).

- I. Chakraborty, S. I. Chakraborty, S. Jana, and S. arXiv:2402.18083. arXiv:2402.18083.

- S. Bhattacharya and S. arXiv:2309.04130. arXiv:2309.04130.

- C. Viermann et al, arXiv:2202.10399. arXiv:2202.10399.

- T. Islam, G. T. Islam, G. Khanna and S. arXiv:2407.16989. arXiv:2407.16989.

- K. Mitman et al, arXiv:2007.11562. arXiv:2007.11562.

- S. Pasterski, A. S. Pasterski, A. Strominger and A. arXiv:1502.06120. arXiv:1502.06120.

- D. Lyth, arXiv:hep-ph/9606387.

- Z. Cao, X. He and Z. Zhao, Phys. Lett. B847138313 (2023).

- R. Haasteren and Y. Levin, arXiv:0909.0954. arXiv:0909.0954.

- N. Jokela, K. N. Jokela, K. Kajantie and M. arXiv:2204.06981. arXiv:2204.06981.

- L. Zwick, A& A,694, A95 (2025).

- L. Mertens et al, arXiv:2206.08041. arXiv:2206.08041.

- N. Deppe et al, arXiv:2502.20584. arXiv:2502.20584.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).