Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

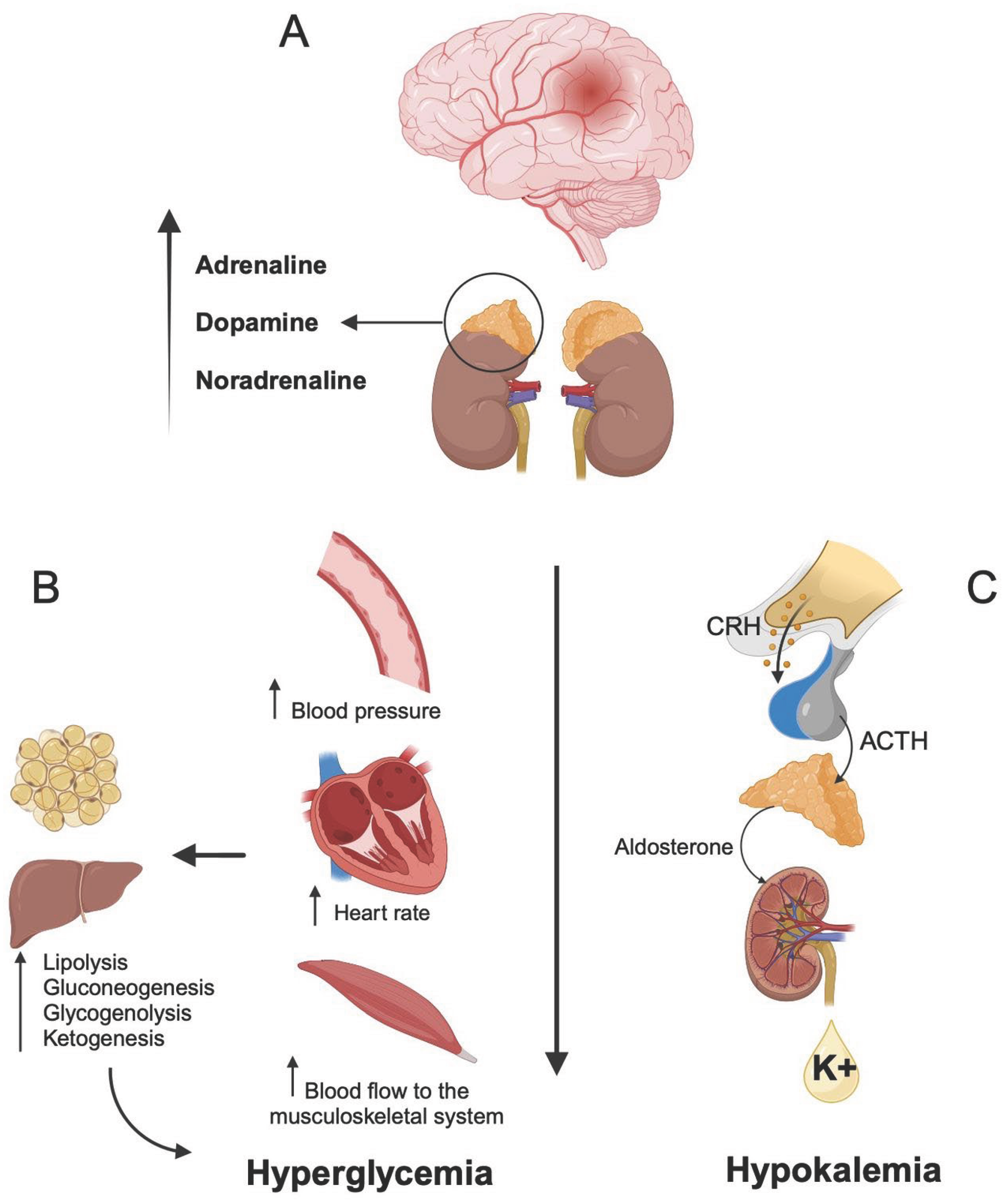

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a life-threatening cerebrovascular event with high mortality and long-term morbidity. While clinical grading scales such as Hunt and Hess or the WFNS score aid in prognosis, their applicability is limited in sedated or unconscious patients. Biomarkers offer an alternative approach for risk stratification. This review examines the prognostic value of the glucose/potassium ratio (GPR) in patients with aneurysmal SAH and its potential integration into future predictive models. A literature review of retrospective studies assessing the association between GPR and clinical outcomes in SAH was conducted. Evidence on the pathophysiological basis of stress-induced hyperglycemia and hypokalemia in SAH is presented, along with findings from five key clinical studies evaluating GPR in relation to mortality, vasospasm, delayed cerebral ischemia, and functional outcomes. Elevated GPR levels were consistently associated with poor short- and long-term outcomes in SAH patients. Studies reported significant correlations between GPR and 30-day mortality, poor Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores, increased incidence of cerebral vasospasm, and higher rates of rebleeding. The optimal GPR cutoff for predicting adverse outcomes was greater than 37 mg/dL, with multivariate analyses confirming GPR as an independent prognostic factor. GPR is a promising, cost-effective biomarker that integrates two stress-response parameters (glucose and potassium), both of which are independently associated with SAH prognosis. Its incorporation into future predictive models may enhance early risk stratification and guide clinical decision-making. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate its utility and standardize its clinical application.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology

3. Development of Glucose/Potassium Index

4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| CeVD | Cerebrovascular disease |

| WFNS | World Federation of Neurological Surgeons |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| HR | Heart rate |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| GPR | Glucose/potassium ratio |

| GOS | Glasgow Outcome Scale |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| SAH-PDS | Subarachnoid hemorrhage Physiologic Derangement Score |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

References

- Bian, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Hussain, M.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Hyperglycemia within day 14 of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage predicts 1-year mortality. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013, 115, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alışkan, H.; Kılıç, M.; Ak, R. Usefulness of plasma glucose to potassium ratio in predicting the short-term mortality of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e38199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohamadi, M.; Saghafinia, M.; Alikhani, F.; Danial, Z.; Shirani, M.; Amirjamshidi, A. Impact of electrolyte imbalances on the outcome of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A prospective study. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016, 11, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Orto, Z.C.; da Silveira, I.V.; Torres França, L.S.; Ferreira Medeiros, M.S.; Cardoso Gomes, T.; Alves Pinto, B.; et al. The Role of Sodium and Glucose in the Prognosis of Patients with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Literature Review of New Evidence. Arq Bras Neurocir. 2024, 43, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminam, N.; Chang, H.S.; Hackenberg, K.; de Rooij, N.K.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; et al. Worldwide Incidence of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage According to Region, Time Period, Blood Pressure, and Smoking Prevalence in the Population. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Cruz-Góngora, V.; Chiquete, E.; Gómez-Dantés, H.; Cahuana-Hurtado, L.; Cantú-Brito, C. Trends in the burden of stroke in Mexico: A national and subnational analysis of the global burden of disease 1990-2019. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022, 10, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.; Mitchell, P. Serum potassium and sodium levels after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg. 2016, 30, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzalegui-Bazán, C.; Durán-Pecho, A.; Botello-Gonzales, D.; Acha-Sánchez, J.L.; Cabanillas-Lazo, M. Association of serum glucose/potassium index levels with poor long-term prognosis in patients with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2024, 247, 108609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, Y.; Matano, F.; Mizunari, T.; Murai, Y.; Tateyama, K.; Koketsu, K.; et al. Serum glucose/potassium ratio as a clinical risk factor for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2018, 129, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beseoglu, K.; Steiger, H.J. Elevated glycated hemoglobin level; and hyperglycemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017, 163, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvela, S.; Siironen, J.; Kuhmonen, J. Hyperglycemia, excess weight, and history of hypertension as risk factors for poor outcome and cerebral infarction after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2005, 102, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, O.; Becker, R.; Benes, L.; Wallenfang, T.; Bertalanffy, H. Initial hyperglycemia as an indicator of severity of the ictus in poor-grade patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2000, 102, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, J.F.; Figueroa, B.E.; DeShane, R.; Blau, S.A.; McAllen, K.J. High glucose variability increases cerebral infarction in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Crit Care. 2013, 28, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruyt, N.D.; Biessels, G.J.; DeVries, J.H.; Luitse, M.J.A.; Vermeulen, M.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; et al. Hyperglycemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potentially modifiable risk factor for poor outcome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010, 30, 1577–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajatia, N.; Topcuoglu, M.A.; Buonanno, F.S.; Smith, E.E.; Nogueira, R.G.; Rordorf, G.A.; et al. Relationship between hyperglycemia and symptomatic vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorhout Mees, S.M.; van Dijk, G.W.; Algra, A.; Kempink, D.R.J.; Rinkel, G.J.E. Glucose levels and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2003, 61, 1132–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerner, A.; Schlenk, F.; Sakowitz, O.; Haux, D.; Sarrafzadeh, A. Impact of hyperglycemia on neurological deficits and extracellular glucose levels in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Neurol Res. 2007, 29, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenk, F.; Vajkoczy, P.; Sarrafzadeh, A. Inpatient Hyperglycemia Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Relation to Cerebral Metabolism and Outcome. Neurocrit Care. 2009, 11, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Donkelaar, C.E.; Dijkland, S.A.; van den Bergh, W.M.; Bakker, J.; Dippel, D.W.; Nijsten, M.; et al. Early Circulating Lactate and Glucose Levels After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Correlate With Poor Outcome and Delayed Cerebral Ischemia: A Two-Center Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2016, 44, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruyt, N.D.; Biessels, G.J.; de Haan, R.J.; Vermeulen, M.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; Coert, B.; et al. Hyperglycemia and Clinical Outcome in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage A Meta-Analysis. Stroke. 2009, 40, e424–e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajun, Z.; Diqing, O.; Xingwei, L.; Liuyang, T.; Xiaofeng, Z.; Xiaoguo, L.; et al. High levels of blood lipid and glucose predict adverse prognosis in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e38601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T.; Hifumi, T.; Kawakita, K.; Shishido, H.; Ogawa, D.; Okauchi, M.; et al. Blood Glucose Variability: A Strong Independent Predictor of Neurological Outcomes in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Intensive Care Med. 2018, 33, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadan, O.; Feng, C.; Vidakovic, B.; Mei, Y.; Martin, K.; Samuels, O.; et al. Glucose Variability as Measured by Inter-measurement Percentage Change is Predictive of In-patient Mortality in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2020, 33, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, R.H.; Pouratian, N.; Zuo, Z.; Scalzo, D.C.; Dobbs, H.A.; Dumont, A.S.; et al. Strict Glucose Control Does Not Affect Mortality after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Anesthesiology. 2009, 110, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Nie, X.; Yao, W.; et al. Association between hyperglycemia at admission and mortality in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2022, 103, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGirt, M.J.; Woodworth, G.E.; Ali, M.; Than, K.D.; Tamargo, R.J.; Clatterbuck, R.E. Persistent perioperative hyperglycemia as an independent predictor of poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2007, 107, 1080–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.M.; Paik, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Hong, D.Y. Association of Plasma Glucose to Potassium Ratio and Mortality After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 661689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matano, F.; Fujiki, Y.; Mizunari, T.; Kokeysu, K.; Tamaki, T.; Murai, Y.; et al. Serum Glucose and Potassium Ratio as Risk Factors for Cerebral Vasospasm after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019, 28, 1951–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, W.; Gao, H. Elevated Glucose-Potassium Ratio Predicts Preoperative Rebleeding in Patients With Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2022, 12, 795376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, W.E.; Hess, R.M. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1968, 28, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.S.; Macdonald, R.L. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Grading Scales A Systematic Review. Neurocrit Care. 2005, 2, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, C.G. Report of World Federation of Neurological Surgeons Committee on a Universal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Grading Scale. J Neurosurg. 1988, 68, 985–986. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, D.S.; Macdonald, R.L. Grading of subarachnoid hemorrhage: modification of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies scale on basis of data for a large series of patients. Neurosurgery. 2004, 54, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claassen, J.; Vu, A.; Kreiter, K.T.; Kowalski, R.G.; Du, E.Y.; Ostapkovich, N.; et al. Effect of acute physiologic derangements on outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2004, 32, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | N | Age | Sex | Primary outcome | OR (95% CI), p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujiki 2017 [9] | aSAH | None | 565 | 61.5 | Female (63.2%) | 3 months poor outcome | *, 0.009 |

| Matano 2019 [28] | aSAH | Patients who refused surgery, postoperative angiography, and DWI-MRI | 333 | 59.7 | Female (63.1%) | Cerebral vasospasm | *, 0.018 |

| Jung 2021 [27] | Non-traumatic aSAH admitted to the ED within 24 h of symptom onset | History of neurological diseases, diabetes, acute or chronic renal failure, malignancy, and liver cirrhosis | 553 | 56 (46-63) | Female (57.5%) | 3 months mortality | 1.070 (1.047-1.093), <0.001 |

| Wang 2022 [29] | aSAH and rebleeding within 72 h | Diabetes, neurological diseases, multiple intracranial aneurysms, acute or chronic renal failure, malignancy, and liver cirrhosis | 744 | 54.8 ± 11.3 | Female (60.5%) | 90 days poor outcome | 0.572 (0.347-0.944), 0.029 |

| Alişkan 2024 [2] | aSAH with a mRS score of ≤2 before | Diabetes, and acute or chronic renal failure | 134 | 65.9 ± 16.7 | Female (50.7%) | All cause 30-day mortality | 4.041 [1.450-26.147), 0.043 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).