1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of industrialization and urbanization has led to increasingly severe environmental pollution, resulting in a significant rise in the frequency of foggy weather conditions. Foggy weather, caused by combined effects of air pollution and meteorological factors, presents substantial challenges for transportation systems and environmental monitoring. Despite complex atmospheric conditions, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) remain a widely used method employed in fields such as traffic surveillance, disaster assessment, border security, and environmental monitoring due to their flexibility and efficiency in aerial monitoring [

1,

2]. However, fog-induced phenomena such as light scattering, reduced contrast, color distortion, and texture blurring severely degrade image quality, thereby impairing the performance of conventional object detection algorithms and limiting the operational effectiveness of UAVs. Consequently, developing robust object detection methods specifically tailored for UAV applications in foggy environments has become an urgent necessity.

Object detection, a fundamental task in UAV visual perception, has evolved from traditional methods based on hand-crafted features and machine learning classifiers [

3,

4,

5] to deep learning-based approaches. Traditional algorithms typically follow a multi-stage process involving candidate region generation, feature extraction, and classification, but suffer from poor robustness and low computational efficiency in complex weather conditions, limiting their suitability for real-time deployment. With the advent of deep learning, convolutional neural network (CNN)-based object detectors have achieved significant breakthroughs, generally categorized into two classes, two-stage based and one-stage based detectors. Two-stage detectors, such as the R-CNN family [

6,

7,

8], achieve high accuracy by separately proposing regions and performing classification and regression, but their relatively slow inference speed hampers real-time applications. By contrast, one-stage detectors, such as YOLO [

9,

10,

11] and SSD [

12] based detectors, directly perform classification and localization in a unified framework, offering faster detection speeds and better real-time performance and making them more suitable for edge computing platforms like UAVs. Recently, various improvements such as feature pyramid networks (FPN) [

13] and attention mechanisms [

14] have been also introduced to enhance feature representation. However, existing models still face issues under foggy weather conditions, including vulnerability to noise interference, insufficient feature enhancement for small and blurred objects, and limited generalization capability.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a lightweight and robust detection framework, termed Hazy-Aware YOLO (HA-YOLO), specifically designed for UAV object detection in foggy environments. Built upon the YOLOv11 backbone, HA-YOLO introduces two key modules that enhance the network’s robustness and feature extraction capabilities:

C3K2-H module — a wavelet convolution-based feature enhancement module designed to emphasize local image details and suppress fog-induced feature degradation.

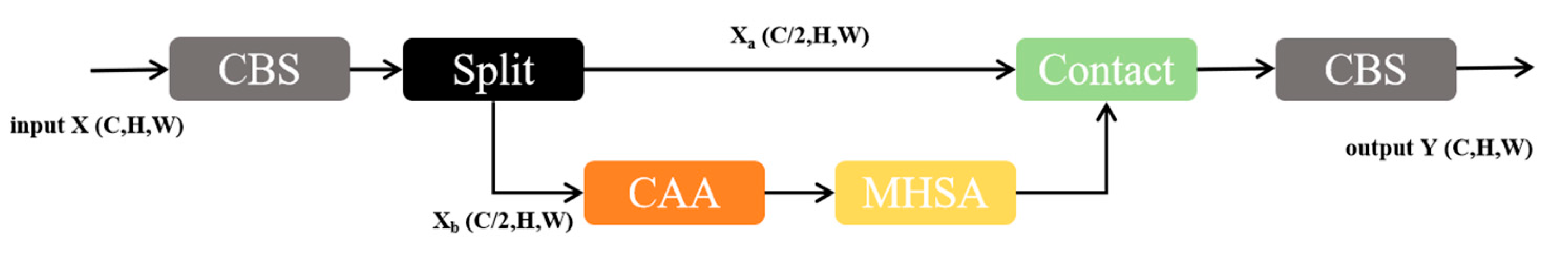

CEHSA (Context-Enhanced Hybrid Self-Attention) module — a hybrid attention mechanism that sequentially integrates Context Anchor Attention (CAA) and Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) to jointly capture local structural information and global semantic relationships, thereby improving the detection of various scales and blurred targets.

Extensive experiments conducted on the HazyDet [

15] and RDDTS datasets validate the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed method, demonstrating superior detection performance compared with several mainstream object detection models.

The objective of this study is to develop a fog-robust UAV detection framework that achieves high detection accuracy and real-time performance without relying on external dehazing or image enhancement modules. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

A wavelet convolution-based feature enhancement module is developed to improve robustness against fog-induced degradation.

A novel hybrid attention mechanism (CEHSA) is proposed to jointly enhance local detail extraction and global context modeling under foggy conditions.

Comprehensive experiments demonstrate that HA-YOLO achieves state-of-the-art performance on challenging UAV foggy weather datasets, maintaining an optimal balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

2. Related Work

2.1. UAV-Based Object Detection

In recent years, object detection in UAV imagery has become a research hotspot in the fields of computer vision and remote sensing, with widespread applications in urban surveillance, emergency rescue, intelligent transportation, and other scenarios. Due to the aerial top-down perspective of UAVs, the captured images often exhibit characteristics such as small object sizes, large scale variations, and dense object distributions, making the detection task highly challenging.

To meet the lightweight and real-time requirements of UAV platforms, researchers have primarily adopted one-stage detection algorithms, such as the YOLO series. For instance, Yang et al. [

16] proposed a lightweight algorithm, L-YOLO, by integrating the GhostNet module into the YOLOv5 architecture to replace conventional convolution operations. This modification not only reduced the number of model parameters but also enhanced the network's ability to detect small objects. Li et al. [

17] added dedicated small-object detection layers to YOLOv7 and employed a Biform Feature Pyramid to extract features at multiple scales, aiming to alleviate the challenges of detecting small objects in UAV images. Gao et al. [

18] introduced the Triplet Attention mechanism into the YOLO backbone to improve detection accuracy and suppress background interference. Shao et al. [

19] replaced the original Conv module in YOLOv8 with GSConv and the C2f module with C3 to reduce parameters, expand the receptive field, and improve computational efficiency, thereby enhancing the model’s suitability for UAV deployment. Fan et al. [

20] proposed a new multi-scale feature fusion strategy by incorporating upsampling operations in both the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) and Progressive Feature Pyramid Network (PFPN) to address feature degradation during propagation and interaction. They also applied model compression techniques to make the network more suitable for deployment on UAV edge devices.

In addition, numerous lightweight detection networks specifically designed for remote sensing or UAV scenarios have been developed, such as RRNet [

21] and DroNet [

22]. Based on the characteristics of UAV application scenarios, this study adopts YOLOv11 as the baseline model to explore an object detection algorithm tailored for UAVs operating in foggy weather conditions.

2.2. Object Detection and Image Enhancement Algorithms in Foggy Conditions

Foggy weather, as a common type of adverse weather condition, often leads to reduced image contrast, blurred edges, and color distortion, which severely interferes with the feature extraction process of object detection algorithms. To address this issue, a widely adopted approach is to perform image dehazing as a preprocessing step before object detection. For instance, methods based on the Dark Channel Prior (DCP) [

23], atmospheric scattering models [

24], and Retinex theory [

25] have been extensively applied to image dehazing, achieving improvements in detection performance in certain tasks. However, these methods typically suffer from low inference efficiency and poor coupling with detection models, making them unsuitable for UAV applications that require real-time performance.

To overcome these limitations, recent studies have explored embedding image enhancement modules directly into detection networks. For example, IA-YOLO [

26] proposed an image processing module that is jointly trained with YOLOv3 in an end-to-end manner, enabling the module to adaptively process images under both normal and adverse weather conditions by predicting degradation characteristics. Qiu et al. [

27] introduced IDOD-YOLOv7, which integrates an image dehazing module (IDOD) with the YOLOv7 detection framework through joint optimization. By combining image enhancement and dehazing within the IDOD module, the network improves image quality, suppresses artifacts in low-light and foggy images, and enhances perception performance for autonomous driving under such challenging conditions. Wan et al. [

28] proposed the MS-FODN network, which incorporates a dehazing module to support object detection and introduces a multi-scale attention-based feature fusion mechanism, improving the network's ability to handle scale variations in remote sensing imagery.

However, despite their effectiveness, these methods still exhibit suboptimal performance in foggy UAV detection scenarios. The integration of image enhancement or dehazing modules not only introduces considerable training and computational overhead but also limits their suitability for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. In contrast, this study aims to enhance the model’s intrinsic feature extraction and fusion capabilities under foggy conditions, thereby improving detection accuracy in hazy environments while maintaining high inference efficiency and real-time performance.

2.3. Application of Attention Mechanism to Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images

With the rapid advancement of remote sensing technology, the spatial resolution of remote sensing imagery has significantly improved, resulting in data characterized by high dimensionality, large-scale scenes, and multiple targets. Accurately extracting critical features from such complex imagery has long been a core challenge in remote sensing object detection. In recent years, attention mechanisms have been widely applied in remote sensing object detection tasks due to their ability to highlight key regions and important features, thereby enhancing detection performance in complex scenes.

Channel attention mechanisms (e.g., SE [

29], ECA [

30]) focus on modeling the importance of different channels within feature maps, thereby enhancing useful channels through weighting. These methods have demonstrated strong performance, particularly in small object detection tasks in remote sensing imagery. Spatial attention mechanisms (e.g., CBAM [

31]), on the other hand, focus on spatial locations where objects are likely to appear, thereby improving the localization of dense or regionally clustered targets. Such mechanisms have been widely embedded in remote sensing detection frameworks such as YOLO and Faster R-CNN [

32,

33].

Following the success of Transformers in natural language processing and computer vision, researchers have begun integrating them into remote sensing object detection tasks. The self-attention mechanism, which captures long-range dependencies between different spatial locations, is particularly suitable for remote sensing imagery characterized by large-scale scenes and dispersed targets. For example, DETR [

34] has been adapted for remote sensing object detection, demonstrating improved performance in accurately locating and delineating objects. In addition, the Swin Transformer [

35], which introduces a local window-based self-attention mechanism, effectively balances global context modeling and computational efficiency, and has been increasingly applied to enhance remote sensing object detection [

36].

In summary, attention mechanisms have become an essential tool for improving model performance in remote sensing image understanding. Future research may further explore directions such as lightweight design, cross-modal fusion, and multi-scale perception, to better integrate attention mechanisms with multi-source remote sensing data (e.g., optical imagery, SAR, infrared), thereby enabling more accurate and robust remote sensing image analysis. In this work, considering the characteristics of foggy UAV imagery, we combine local spatial attention with multi-head attention to enhance the model’s ability to detect blurred objects.

3. Proposed Method

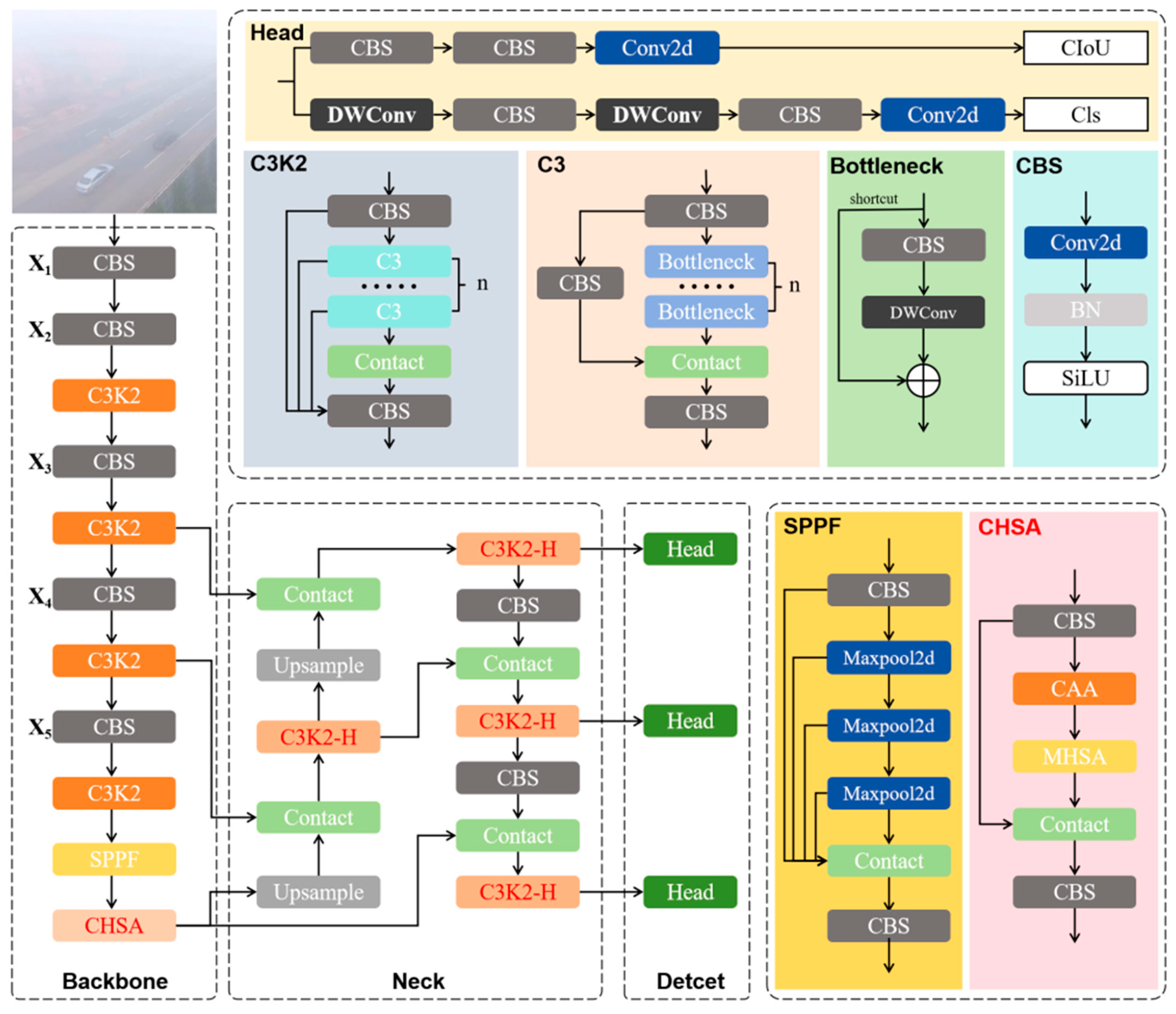

The overall structure of HA-YOLO is shown in

Figure 1 where the model consists of three main components: the backbone, neck, and detection head. Given an input image

,the backbone first processes the input image, extracting hierarchical features

( i =1,2,3,4,5) through downsampling. These feature maps are then passed through the SPPF module before being input into the CEHSA module for attention computation. Next, the neck fuses multi-scale feature maps

( i =3,4,5). To enhance the network’s denoising and feature fusion capabilities, wavelet convolution is introduced into the C3K2 modules in the neck. Finally, the fused feature maps

( i =3,4,5) are extracted from the neck and processed by three detection heads for object localization and classification. In

Figure 1, the upper-right section illustrates some fundamental network components, with red-marked parts indicating the proposed modifications. The following sections will provide a detailed explanation of the C3K2-H module and CEHSA module.

The detailed computation process of the HA-YOLO is outlined in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: HA-YOLO for UAV Foggy Target Detection |

| Input: |

|

|

|

Output:

|

|

- 2.

-

Extract feature maps using the backbone and output multi-scale feature maps (P3, P4, and P5)

//downsample and extract features

|

- 3.

-

Fuse features across multi-scale feature maps using the neck network (P3, P4, and P5).

//upsampling, channel concatenation, and downsampling

|

- 4.

-

Pass the fused features through the detection head to obtain preliminary predictions:

B_pred, C_pred = DetectionHead(F_fused)

|

- 5.

-

Apply Non-Maximum Suppression:

B, C = NMS(B_pred, C_pred)

|

- 6.

Return B,C

|

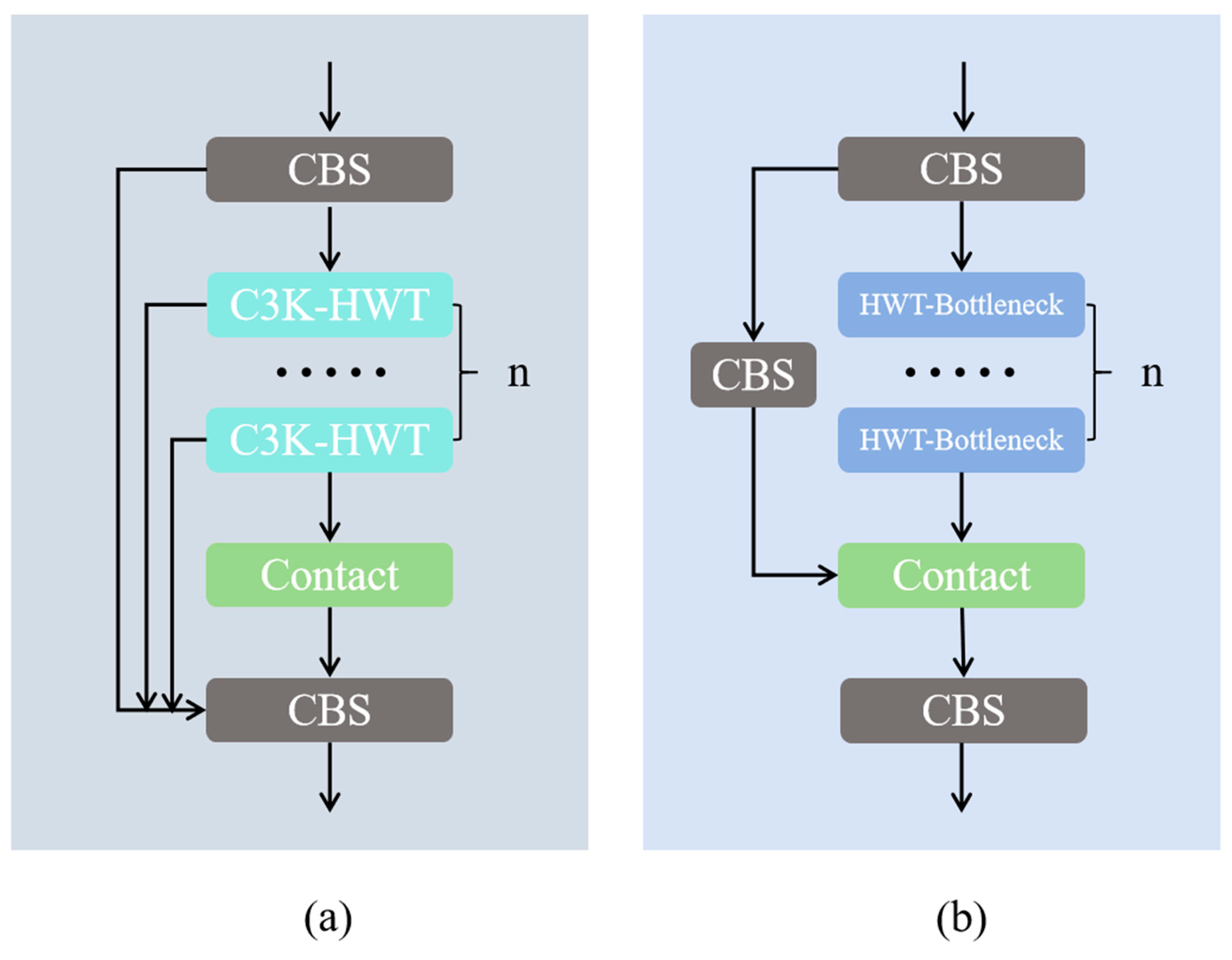

3.1. C3K2-H Module

The C3K2 module is an improved bottleneck structure in YOLO11, designed to enhance feature extraction capability. The traditional C3K2 mainly consists of multiple C3 modules, which incorporate 1×1 and 3×3 convolutions to achieve efficient information interaction. However, in foggy environments, standard convolutions have limited ability to capture object edge information and are susceptible to low contrast and blurring effects. To address this issue, we optimize the C3K2 module by introducing Wavelet Convolution (WTConv) [

37] into the bottleneck structure, forming the C3K2-H module. The overall structure of C3K2-H is illustrated in

Figure 2. While maintaining the bottleneck design, we replace the depthwise separable convolution with wavelet convolution (using the Haar wavelet basis). By decomposing the input features through wavelet convolution, the model learns high-frequency and low-frequency information separately, allowing it to better preserve edges, contours, and other high-frequency details while reducing the blurring effects caused by foggy environments.

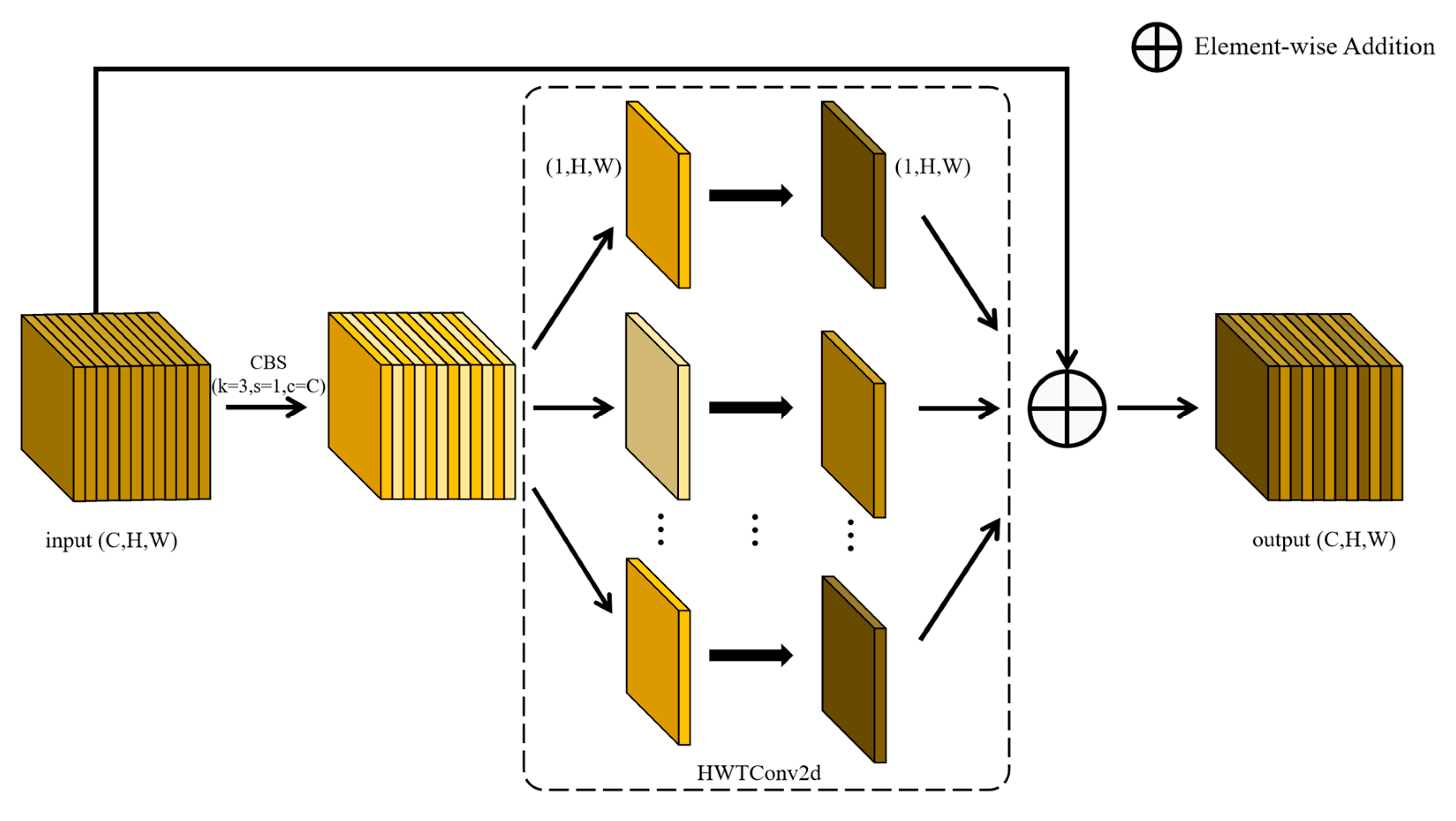

The detailed calculation process of HWT-Bottleneck is illustrated in

Figure 3. The input feature map

undergoes a 3×3 convolution to fuse channel information while simultaneously integrating local spatial features:

Here, X represents the input feature map with dimensions C×H×W. Conv2d denotes a standard convolution, BN refers to batch normalization, and SiLU is the activation function. Next, the output feature map is processed using wavelet convolution, which enables independent learning of high-frequency and low-frequency information across channels:

Finally, the input feature map is connected to the original feature map through a residual connection, preserving the original information while preventing gradient vanishing issues during training. The final output feature map is represented as:

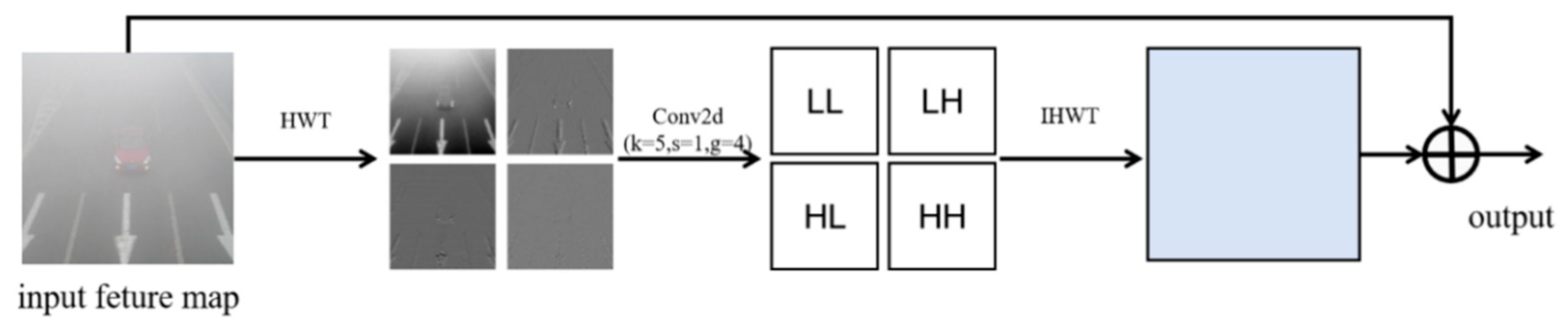

WTConv (Wavelet Transform Convolution) is a module that integrates wavelet transform with convolution operations, aiming to enhance the model’s ability to extract multi-scale features, particularly for object detection tasks in complex environments. Considering the deployment constraints of edge UAV devices, this work adopts the Haar wavelet basis for wavelet convolution, ensuring high computational efficiency while improving the model’s ability to detect objects in foggy conditions. Similar to depthwise separable convolution, HWTConv2d operates channel-wise, followed by concatenation along the channel dimension, significantly reducing computational costs. The specific process of wavelet convolution is illustrated in

Figure 4, where we take a single-channel computation as an example.

First, for the input feature map

the Haar wavelet transform can decompose it into four sub-bands using four filters:

Here,

is a low-pass filter, and

are high-pass filters in different directions. These filters are used as a set of depthwise convolution kernels to perform a depthwise convolution with a stride of 2 on the input feature map. This operation produces four downsampled feature maps:

Here, X

LL, X

LH, X

HL, X

HH represent the low-frequency component and the three high-frequency components in different directions of X, each with a resolution of half of the original input. Next, a depthwise convolution operation is applied to the four components, and an inverse wavelet transform is performed to restore the feature maps to the same resolution as the input feature map. Finally, the output feature map is connected to the original input feature map through a residual connection, and the final output feature map can be represented as:

Here, IHWT refers to the inverse Haar wavelet transform. Since the Haar wavelet basis is an orthogonal wavelet basis, the output feature maps can be restored to their original size through the inverse wavelet transform.

3.2. CEHSA Module

Due to the varying flight altitudes of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and the complexity of their imaging environments, the captured images often exhibit significant variations in object scale and complex background information. In such scenarios, incorporating attention mechanisms to model and refine feature maps can effectively highlight key object regions and enhance detection performance. However, in adverse conditions such as foggy weather, targets in the images tend to appear blurred, with low contrast and indistinct edges. This degrades the performance of conventional attention mechanisms—such as Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA)—in modeling fine-grained details, thereby limiting the model’s ability to perceive fuzzy targets.

To address this issue, we propose a Context-enhanced Hybrid Self-Attention (CEHSA) module to improve detection robustness under complex environments. The CEHSA module integrates Context Anchor Attention (CAA) [

38] with MHSA, combining local detail sensitivity with global semantic modeling. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the architecture consists of two branches: a residual branch and an attention-enhancement branch. This design aims to implement a residual learning mechanism. X

a serves as the identity mapping path, preserving the original feature information to ensure network training stability and alleviate the gradient vanishing problem. X

b, on the other hand, flows through the attention enhancement path, where the CAA and MHSA modules extract attention features rich in contextual information. Finally, the features from the two paths are summed, enhancing key features without losing fundamental information, thereby achieving improved robustness under complex foggy conditions.

The input feature map

first passes through a convolutional layer and is then split into two parts:

The first part, is retained as residual information to reinforce the original feature representation. The second part, , is fed into the attention pathway to enhance the features through attention modeling.

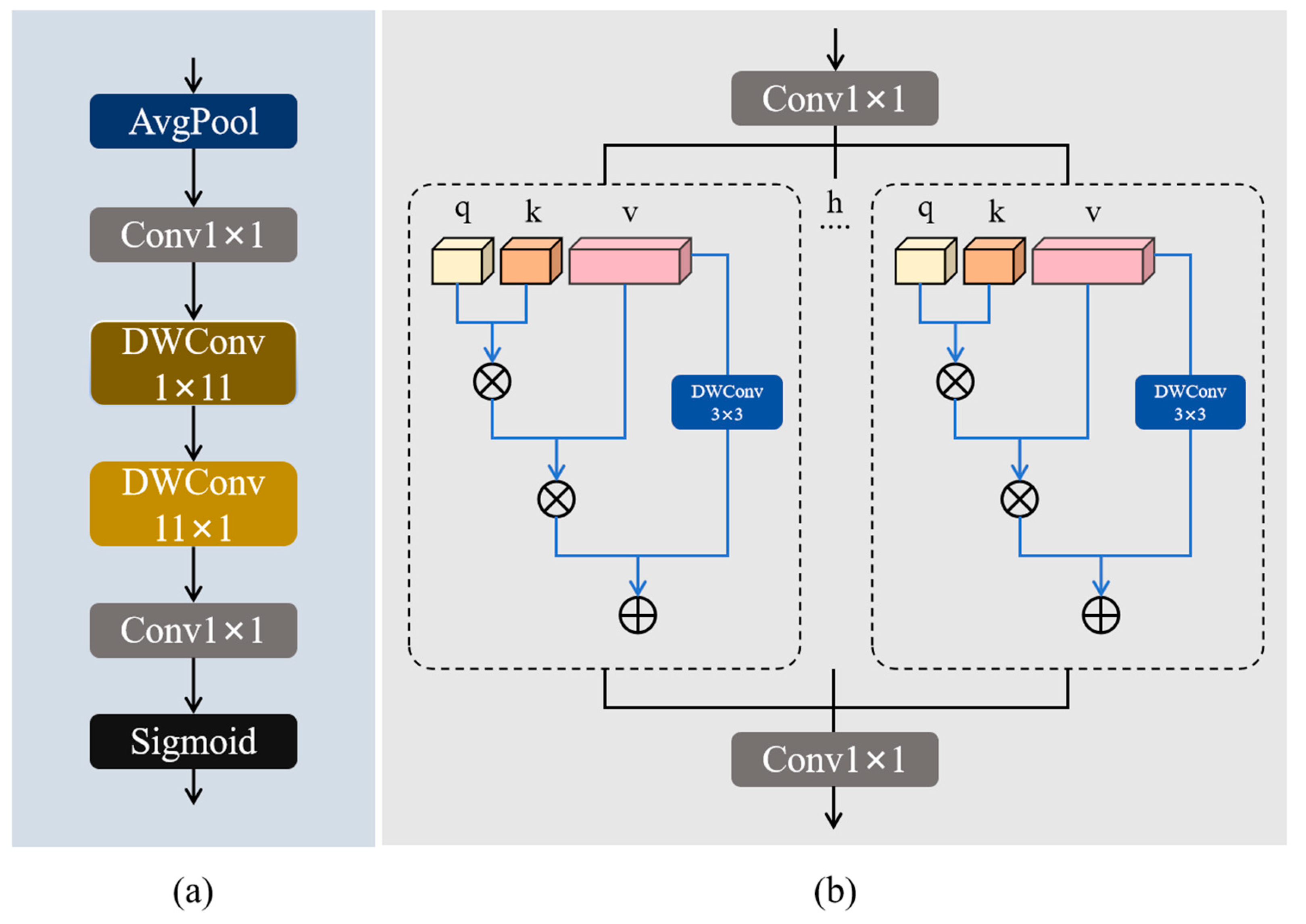

3.2.1. CAA Module

The CAA module is a lightweight context-aware attention mechanism that is well-suited for object detection tasks in remote sensing imagery. As a convolutional attention mechanism, it enhances the ability to capture local details, effectively compensating for the limitations of MHSA when handling blurred targets. As shown in

Figure 6a, the computation process of CAA consists of three main components: horizontal convolution, vertical convolution, and channel attention weighting.

First, local features are obtained through average pooling followed by a 1×1 convolution:

Here, Pavg denotes the average pooling operation. Then, two depthwise separable strip convolutions are used to simulate a large standard convolution kernel in a depthwise separable manner, enabling effective extraction of contextual information:

Finally, a 1×1 convolution followed by a Sigmoid activation function is applied to generate the attention weights:

3.2.2. MHSA Module

MHSA is employed to capture the global contextual information from the input feature map, and its detailed computation process is illustrated in

Figure 6b. The core steps involve projecting the input into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) representations, computing the attention scores, and aggregating the outputs accordingly. The specific computation is as follows:

Let the input feature map be denoted as

. First, three separate 1×1 convolutions are applied to generate the query (Q), key (K), and value (V) representations:

Here, C denotes the number of channels, while H and W represent the height and width of the feature map, respectively. The above features are divided into h attention heads, with each subspace having a dimensionality of:

Here, r represents the compression ratio of the key (set to 0.5 in this paper) to reduce computational complexity. After flattening the feature map, the attention weights for each head in MHSA are computed using the scaled dot-product as follows:

The output representation is obtained by weighting V using the attention weights as follows:

Then, relative positional information is introduced to V using a 3×3 depthwise separable convolution:

Finally, the output global attention representation is

The CEHSA module addresses the issue of insufficient target recognition in blurry images by employing a "local-global" collaborative attention mechanism. This design effectively leverages the CAA's ability to capture local contextual information and the MHSA's capability to model global semantics, enhancing detection performance under low-visibility conditions such as heavy fog.

4. Experimental Validation and Analysis

This section presents a comprehensive study and comparative analysis on our proposed model against existing state-of-the art methods. The evaluation involves a set of indicators designed to quantitatively assess the effectiveness of the model. Among these, the most critical metrics include Recall (R), Precision (P), F1-Score, Average Precision (AP), and Mean Average Precision (mAP) — each offering insights into different aspects of the model’s performance.

Precision measures the ratio between correctly detected target samples and all predicted target samples, while Recall quantifies the proportion of correctly detected target samples among all annotated ground truth samples. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a balanced measure of both metrics. The calculation formulas are as follows:

Here, TP (True Positive) refers to the number of correctly detected positive samples. FP (False Positive) denotes the number of samples that are incorrectly detected as positive. FN (False Negative) represents the number of positive samples that are incorrectly classified as negative.

In object detection average precision (AP) has been one of most commonly used metrics to evaluate model performance. It refers to the area under the precision-recall (P-R) curve and reflects the model's detection capability across different threshold settings. In practice, AP is typically approximated by integrating a set of discretely sampled points on the P-R curve, and is calculated as follows:

where

Pn denotes the precision at the n-th point, R

n denotes the recall at the

nth point, and N is the total number of recall variation points.

Average Precision (AP) evaluates the detection performance of a single class under a specific Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold. To comprehensively assess the model's performance across multiple classes, the mean Average Precision (mAP) is introduced, which is the mean of the AP values over all categories. It is calculated as follows:

where

N denotes the total number of categories, and AP

irepresents the AP of the

ith class.

mAP@0.5 refers to the mAP calculated under a fixed Intersection over Union (IoU) using the threshold value of 0.5, where a prediction is considered correct if the IoU between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth exceeds 0.5. This metric evaluates the model’s detection accuracy under a relatively lenient matching criterion. mAP@0.5:0.95 is a more comprehensive evaluation metric. It computes the mean of AP values across multiple IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05 (i.e., at 0.5, 0.55, 0.6, ..., 0.95), thus assessing the model's performance under increasingly strict localization requirements. The calculation is given by:

Together, these evaluation metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of object detection model performance. They reflect the model’s accuracy, recall ability, and overall balance, offering valuable insights into its strengths and limitations across various detection scenarios. This, in turn, guides subsequent improvements and optimizations in model design.

4.1. Data Set Used for Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of HA-YOLO, the HazyDet dataset which was collected by the Army Engineering University of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, Nankai University, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, and Nanjing University of Science and Technology and released at the end of September 2024, was used for a series of experiments. This dataset contains 11,600 drone images, composed of both real-world foggy drone images and artificially synthesized foggy drone images. It includes 383,000 real-world instances and, in addition to the training, validation, and test sets, a separate real-hazy drone detection testing set (RDDTS) was also created to evaluate the performance of a detector under real-world conditions.

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 provide details of the HazyDet data set, computer environment, training parameters used in experiments where the area of small targets is less than 0.1% of the image area, the areas of medium targets range from 0.1% to 1%, and the areas of large targets exceed 1%.

Figure 7 shows some examples from the HazyDet data set.

4.2. Ablation Experiments

4.2.1. Module Comparison Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of the C3K2-H module when integrated into different parts of the network, we replaced the original C3K2 modules in the YOLO11n architecture with C3K2-H modules at three locations: the Backbone, the Neck, and the entire network. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 4, with the best-performing results highlighted in bold.

It can be observed that incorporating the C3K2-H module consistently enhances the model’s detection performance to varying degrees, confirming the effectiveness of wavelet convolution in improving detection under hazy conditions. Notably, applying the C3K2-H module to both the Backbone and Neck achieves the highest detection accuracy, but this comes at the cost of 8.1% increase in Parameters and a noticeable decrease in inference speed. In contrast, integrating C3K2-H only into the Neck results in a 1.9% reduction in Parameters, with only a slight performance drop on the validation set and even the best performance on the test set.

Table 5 presents the results of the ablation study on the selection of wavelet bases. The Haar (db1) wavelet consistently outperforms other bases (e.g., Db4, Db6) across key metrics, achieving the highest mAP@0.5 (0.702) and FPS (670.7). While smoother bases like Db4 offer better frequency localization, their increased computational complexity does not translate into accuracy gains for the foggy detection task. Consequently, Haar is adopted as the default wavelet base in our C3K2-H module.

Considering the constraints of edge deployment scenarios, which demand compact and efficient models, our final proposed model incorporates the C3K2-H module exclusively in the Neck to balance accuracy, model size, and inference speed.

4.2.2. Attention Comparison Experiments

To validate the rationality of the CEHSA module design, ablation experiments were conducted to compare it with two individual attention mechanisms and their structural variants: (1) Reversed structure (MHSA→CAA) - where MHSA is applied before CAA; (2) Parallel structure - where the outputs of CAA and MHSA are concatenated along the channel dimension and then fused. All experiments were performed based on the YOLO11n architecture, and the results are presented in

Table 6.

As shown in the table, the proposed CEHSA module achieves the best performance on both the HazyDet validation and test sets, with mAP@0.5-95 scores of 48.6% and 50.2%, representing improvements of 1.7% and 1.6% over MHSA, respectively. In addition, CEHSA demonstrates higher recall and precision, indicating its stronger capability in identifying blurred and low-contrast targets. Meanwhile, the “MHSA → CAA” structure performs significantly worse than the baseline model, suggesting that under foggy conditions with a low signal-to-noise ratio, performing global attention aggregation first tends to amplify noise or distract attention. Consequently, the subsequent local enhancement module (CAA) struggles to effectively recover the already degraded detail information, ultimately leading to reduced performance.

Meanwhile, to further verify the effectiveness of the CEHSA module, we conducted ablation experiments on the YOLOv8n and YOLOv5n models. As shown in

Table 7, the detection performance of both models improved on the test set and the RDDTS dataset after integrating the CEHSA module. Notably, the YOLOv8n model achieved a 2.6% increase in mAP on the test set.

These results confirm that CEHSA effectively integrates the local modeling strength of CAA with the global context modeling ability of MHSA, achieving greater robustness and generalization in challenging environments such as foggy weather.

4.2.3. Module Ablation Experiments

Considering the lightweight deployment requirements of UAV platforms, we conducted ablation studies using YOLO11n and YOLO11s as baseline models to evaluate the contribution of each proposed module. The experimental results are shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9.

As observed, progressively integrating the proposed modules into the network leads to consistent improvements in Precision, Recall, and mAP on both the validation and test sets. Specifically, introducing either the C3K2-H module or the CEHSA module individually yields notable performance gains. Among them, the CEHSA module shows more significant improvements in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95. On the test set, YOLO11n+CEHSA achieves increases of 1.7% and 1.6%, respectively, over the baseline, while YOLO11s+CEHSA improves by 1.2% and 1.1%.

The C3K2-H module also brings stable gains in Recall and detection accuracy. When both C3K2-H and CEHSA are integrated simultaneously, the overall performance reaches the best level. On the test set, HA-YOLOn achieves mAP@0.5 of 71.2% and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 50.6%, improving by 2.2% and 2.0% over the baseline, respectively. HA-YOLOs reaches 76.0% and 55.8%, outperforming the baseline by 1.5% for both metrics.

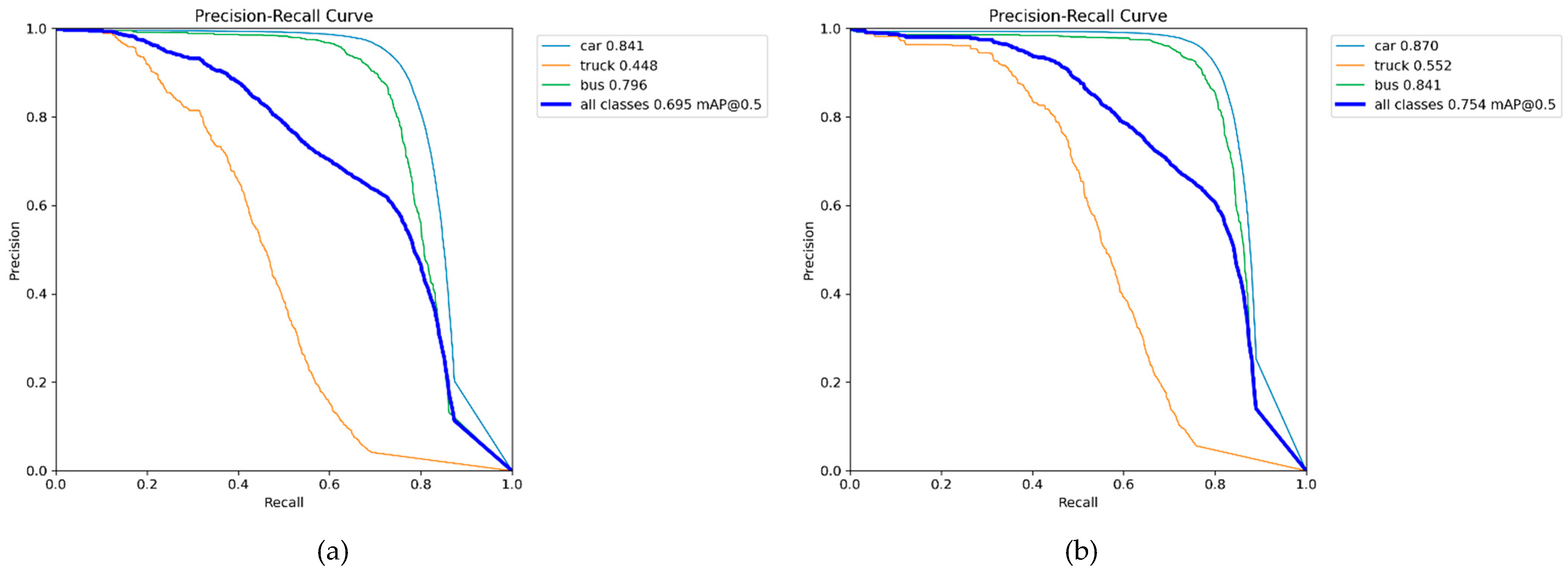

Figure 8 illustrates the P-R curves of HA-YOLOn and HA-YOLOs on the HazyDet dataset, demonstrating that both models achieve promising detection performance under foggy conditions. Specifically, the average precision for cars reaches 84.1% and 87%, and for buses, 79.6% and 84.1%, respectively, while the performance for trucks is significantly lower, with average precision of only 44.8% and 55.2%. This performance gap can be attributed to the relatively regular shapes and consistent structural features of cars and buses, which remain more distinguishable even in foggy environments, making it easier for the model to learn effective discriminative representations. In contrast, trucks exhibit considerable intra-class variation due to diverse types such as tankers, box trucks, and construction vehicles, which complicates feature learning. Additionally, the large physical size of trucks increases the likelihood of occlusion and truncation, and under foggy conditions, their boundaries often become blurred, further impairing the model’s ability to accurately localize and classify them.

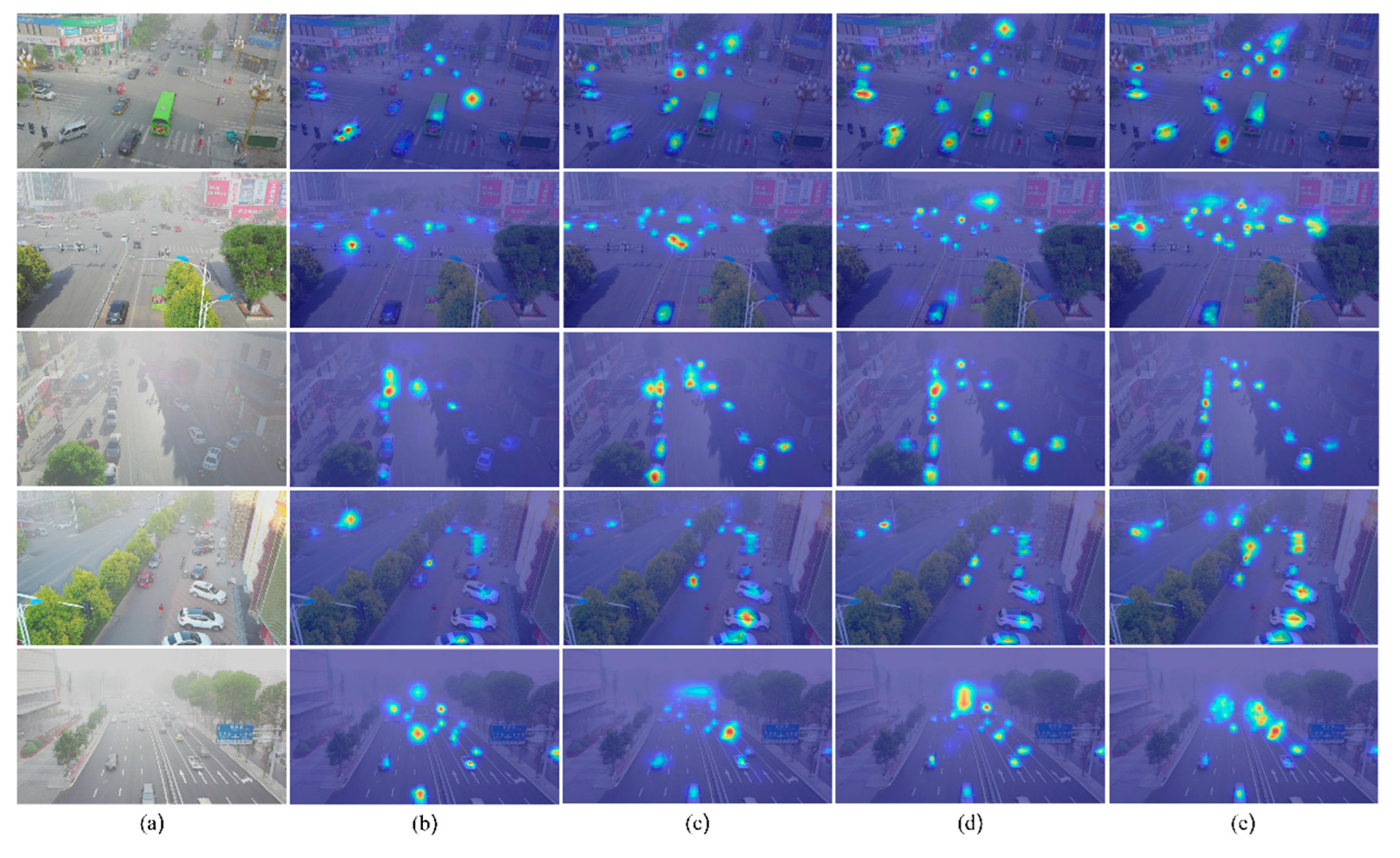

To more intuitively demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method,

Figure 9 presents a heatmap comparison between the baseline models YOLO11n and YOLO11s and the improved models HA-YOLOn and HA-YOLOs under foggy conditions. In heavy fog scenarios, distant targets often exhibit more blurred contours and lower signal-to-noise ratios, which pose greater challenges for feature extraction and recognition. As shown in the figure, the original YOLO11n and YOLO11s models exhibit dispersed attention regions and weak heatmap responses, especially for distant targets in blurred backgrounds, where background interference makes it difficult to accurately localize objects. In contrast, after integrating the CEHSA and C3K2-H modules, the improved HA-YOLOn and HA-YOLOs models demonstrate significant advantages: the target regions in the heatmaps show stronger activation, with attention more focused on the objects themselves rather than surrounding redundant areas, indicating enhanced target perception capabilities.

As shown in

Table 10, we further analyzed the detection performance for targets of different scales (small, medium, and large) on the RDDTS dataset. Among all models, HA-YOLOs achieved the best performance across all target scales, with an AP

s of 15.8% for small targets, an AP

m of 36.4% for medium targets, and an AP

l of 50.2% for large targets. Compared with the baseline model YOLO11s, HA-YOLOs demonstrated a significant improvement, particularly for large targets, where AP

l increased from 0.456 to 50.2%—representing a relative improvement of approximately 10.1%. It is worth noting that, compared with their respective baseline models, both HA-YOLOn and HA-YOLOs exhibited enhanced detection capability across all target scales. This verifies the effectiveness of the proposed module in handling targets commonly affected by haze in UAV imagery. Moreover, the improvement in small-target accuracy (AP

s) indicates that the model’s robustness is achieved without sacrificing its ability to detect fine details.

Figure 10 presents a comparison of detection results between HA-YOLOs and YOLO11s on the RDDTS dataset. As shown in

Figure 10a, HA-YOLO achieves more accurate detection of small, distant targets under foggy conditions compared with the baseline model. In addition, the truck category exhibits visual characteristics similar to buildings, and its limited representation in the dataset significantly increases the detection difficulty. Compared with the baseline, HA-YOLOs demonstrate higher precision in detecting trucks, while the baseline model shows both missed detections and false positives, as illustrated in

Figure 10b,c.

The combined results of the ablation studies and visualization analysis further validate the effectiveness and practical adaptability of the proposed method in real-world UAV remote sensing scenarios.

4.3. Comparisons with Other Object Detection Networks

To further validate the generalization capability of the proposed HA-YOLO under complex weather conditions, we conducted comparative experiments against several state-of-the-art real-time object detection models on both the HazyDet test set and the RDDTS dataset. The corresponding results are shown in

Table 11 and

Table 12, respectively. Notably, RDDTS was collected under real-world heavy fog conditions, making it more representative of practical deployment scenarios and inherently more challenging.

On the HazyDet test set, both HA-YOLOn and HA-YOLOs achieved superior detection performance across multiple object categories. In particular, HA-YOLOs achieved AP scores of 87.5% for car, 56.6% for truck, and 83.8% for bus, with an overall mAP@0.5 of 76.0%. This represents a significant improvement over YOLO11s and YOLOv12s [

39], while maintaining a high inference speed of 446 FPS—demonstrating an excellent balance between accuracy and real-time performance.

Furthermore, the HA-YOLO series also performed robustly on the RDDTS dataset. Compared to baseline models, HA-YOLOn and HA-YOLOs achieved mAP@0.5 improvements of 2.9% and 3.7%, respectively. Taking HA-YOLOs as an example, it attained AP scores of 82.0% for car, 20.6% for truck, and 43.5% for bus, with a mAP@0.5 of 48.7% and mAP@0.5:0.95 reaching 32.7%. These results highlight the model's stability and superior performance across diverse categories. In contrast, models from the DETR series [

40], all of which have computational costs exceeding 97.2 GFLOPs, failed to deliver competitive detection performance under challenging weather conditions and for small objects—thereby limiting their applicability in foggy UAV target detection tasks.

As shown in

Table 13, when compared with detection networks specifically designed for foggy environments, these models typically integrate a defogging module within the network architecture for joint training, which considerably increases the number of parameters and training cost. The results indicate that the HA-YOLO model has significantly fewer parameters and lower GFLOPs than IDOD-YOLOv7 and IA-YOLO, while achieving notably better detection performance than IA-YOLO. This provides strong evidence that enhancing internal feature representations is a more effective strategy for improving robustness in foggy UAV detection tasks than relying on integrated defogging modules.

To more intuitively demonstrate the detection performance of HA-YOLO in foggy UAV scenarios, we selected several representative foggy images from the RDDTS dataset and conducted qualitative comparisons with other detection algorithms. The results are shown in

Figure 11. As illustrated, all models exhibit varying degrees of false detections and missed targets under dense fog conditions. In contrast, HA-YOLO demonstrates a significantly stronger ability to accurately detect objects obscured by fog, with fewer false positives and omissions.

In conclusion, the HA-YOLO series consistently delivers high detection accuracy and fast inference speeds across various foggy environments. These findings confirm that the proposed improvements not only enhance the network's ability to perceive blurred and low-contrast targets, but also provide strong generalization capabilities and practical value for real-world UAV-based applications.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, HA-YOLO is presented which is a lightweight object detection framework tailored for challenging remote sensing scenarios under adverse weather conditions, with a particular focus on detecting small and distant objects in UAV imagery captured in heavy fog. Several main conclusions are summarized as follows:

Based on YOLOv11, a hybrid attention module, CEHSA is designed to integrate CAA and MHSA and effectively fuses local detail features with global semantic information, enhancing the saliency representation of targets—especially beneficial for detecting small and blurred objects. Additionally, the C3K2-H module with wavelet convolution introduced into YOLOv11 can boost the model's ability to capture fuzzy edges and fine-grained features. These two modules jointly work together to significantly enhance the model's robustness in complex remote sensing imagery.

Ablation studies also demonstrate that CEHSA and C3K2-H can individually improve detection performance alone. However, when they are coupled with each other, their joint performance consistently yield best results among different YOLO11 lightweight variants. In particular, for the YOLO11n architecture, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 improve by 2.2% and 2.0%, respectively, confirming the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed modules.

Compared with state-of-the-art detection models such as YOLOv8, YOLOv12, and RT-DETR, as well as models specifically designed for foggy object detection, HA-YOLO demonstrates superior detection accuracy on both synthetic datasets and real-world foggy remote sensing datasets, while maintaining low computational cost and high inference speed. Notably, in tests on the real-world RDDTS dataset, HA-YOLO achieves an average mAP that is 2.9% higher than YOLOv11 and YOLOv12, highlighting its strong potential for practical applications.

Heatmap visualizations further illustrate that HA-YOLO produces more focused and accurate activation regions for small, distant, and blurry targets which also validate the effectiveness of CEHSA in enhancing the representation of ambiguous objects. Compared to the baseline model, HA-YOLO better highlights key regions, resulting in stronger perceptual capabilities overall.

In future work, we plan to explore extending HA-YOLO to a broader range of adverse conditions, including nighttime, rain, and snow, while further optimizing lightweight architectures and attention mechanisms to enable real-time UAV deployment in challenging environments.

References

- Outay, F.; Mengash, H. A.; Adnan, M. Applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) in Road Safety, Traffic and Highway Infrastructure Management: Recent Advances and Challenges. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. A Vision-Based Target Detection, Tracking, and Positioning Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 5565589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid Object Detection Using a Boosted Cascade of Simple Features. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; Volume 1, pp. 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzenszwalb, P.F.; Girshick, R.B.; McAllester, D.; Ramanan, D. Object Detection with Discriminatively Trained Part-Based Models. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 32, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L.S. Soft-NMS—Improving Object Detection with One Line of Code. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5561–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23-28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7-13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NIPS 2015); Cortes, J., Lawrence, N., Lee, D., Sugiyama, M., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C. Y.; Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot Multibox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–16 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Cheng, M.-M.; Dai, Y.; Fu, Q. HazyDet: Open-Source Benchmark for Drone-View Object Detection with Depth-Cues in Hazy Scenes. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19833. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, J.; Shang, X.; et al. A Lightweight Small Target Detection Algorithm with Multi-Feature Fusion. Electronics 2023, 12, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; et al. SOD-UAV: Small Object Detection for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images via Improved YOLOv7. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Korea (South), 14–19 April 2024; pp. 7610–7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; et al. YOLO-TSL: A Lightweight Target Detection Algorithm for UAV Infrared Images Based on Triplet Attention and Slim-Neck. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 141, 105487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. Aero-YOLO: An Efficient Vehicle and Pedestrian Detection Algorithm Based on Unmanned Aerial Imagery. Electronics 2024, 13, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Li, Y.; Deveci, M.; et al. LUD-YOLO: A Novel Lightweight Object Detection Network for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Inf. Sci. 2025, 686, 121366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Q.; et al. RRNet: A Hybrid Detector for Object Detection in Drone-Captured Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Seoul, Korea (South), 27–28 October 2019; pp. 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrkou, C.; Plastiras, G.; Theocharides, T.; et al. DroNet: Efficient Convolutional Neural Network Detector for Real-Time UAV Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Dresden, Germany, 19–23 March 2018; pp. 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single Image Haze Removal Using Dark Channel Prior. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. AOD-Net: All-in-One Dehazing Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4770–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhuang, P.; Huang, Y.; et al. A Retinex-Based Enhancing Approach for Single Underwater Image. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Paris, France, 27–30 October 2014; pp. 4572–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ren, G.; Yu, R.; et al. Image-Adaptive YOLO for Object Detection in Adverse Weather Conditions. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. IDOD-YOLOV7: Image-Dehazing YOLOV7 for Object Detection in Low-Light Foggy Traffic Environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, L.; et al. Collaboration of Dehazing and Object Detection Tasks: A Multi-Task Learning Framework for Foggy Image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5600815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; et al. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, J.; Zheng, H.; et al. Efficient Object Detection Method Based on Aerial Optical Sensors for Remote Sensing. Displays 2022, 75, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Optical Remote Sensing Ship Recognition and Classification Based on Improved YOLOv5. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; et al. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; et al. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Feng, Z.; Cao, C.; et al. An Improved Swin Transformer-Based Model for Remote Sensing Object Detection and Instance Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finder, S. E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet Convolutions for Large Receptive Fields. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2024; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Lai, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Poly Kernel Inception Network for Remote Sensing Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 27706–27716. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; et al. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; et al. Dab-DETR: Dynamic anchor boxes are better queries for DETR. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; et al. Deformable DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Overall Framework of HA-YOLO.

Figure 1.

Overall Framework of HA-YOLO.

Figure 2.

(a) Structure of C3K2-H (b) Structure of C3K-HWT.

Figure 2.

(a) Structure of C3K2-H (b) Structure of C3K-HWT.

Figure 3.

Detailed Computation Process of HWT-Bottleneck.

Figure 3.

Detailed Computation Process of HWT-Bottleneck.

Figure 4.

Detailed Computation Process of HWTConv2d.

Figure 4.

Detailed Computation Process of HWTConv2d.

Figure 5.

The structure of CEHSA module.

Figure 5.

The structure of CEHSA module.

Figure 6.

(a) Detailed Computation Process of CAA (b) Detailed Computation Process of MHSA.

Figure 6.

(a) Detailed Computation Process of CAA (b) Detailed Computation Process of MHSA.

Figure 7.

Samples from the HazyDet Dataset.

Figure 7.

Samples from the HazyDet Dataset.

Figure 8.

Precision-Recall (P-R) Curves of the Models. (a) P-R curve of HA-YOLOn. (b) P-R curve of HA-YOLOs.

Figure 8.

Precision-Recall (P-R) Curves of the Models. (a) P-R curve of HA-YOLOn. (b) P-R curve of HA-YOLOs.

Figure 9.

Heatmaps Before and After Improvement(a) Original Image (b) YOLO11n Heatmap (c) HA-YOLOn Heatmap (d)YOLO11s Heatmap (e)HA-YOLOs Heatmap.

Figure 9.

Heatmaps Before and After Improvement(a) Original Image (b) YOLO11n Heatmap (c) HA-YOLOn Heatmap (d)YOLO11s Heatmap (e)HA-YOLOs Heatmap.

Figure 10.

Detection results of HA-YOLOs and the baseline model on the RDDTS dataset. From left to right: ground truth, baseline model, and HA-YOLOs detection results. Red boxes indicate failed detections.

Figure 10.

Detection results of HA-YOLOs and the baseline model on the RDDTS dataset. From left to right: ground truth, baseline model, and HA-YOLOs detection results. Red boxes indicate failed detections.

Figure 11.

Real-World Foggy Detection Results. (a) RT-DETR-l Results (b) YOLOv8n Results (c) YOLO11n Results (d) YOLOv12n Result (e) HA-YOLOn Results.

Figure 11.

Real-World Foggy Detection Results. (a) RT-DETR-l Results (b) YOLOv8n Results (c) YOLO11n Results (d) YOLOv12n Result (e) HA-YOLOn Results.

Table 1.

Partitioning of the HazyDet data set.

Table 1.

Partitioning of the HazyDet data set.

| Split |

Images |

Objects |

Class |

Object Size |

| Small |

Medium |

Large |

| Training |

8,000 |

264,511 |

car |

159,491 |

77,527 |

5,177 |

| truck |

4,197 |

6,262 |

1,167 |

| bus |

1,990 |

7,879 |

861 |

| Validation |

1,000 |

34,560 |

car |

21,051 |

9,881 |

630 |

| truck |

552 |

853 |

103 |

| bus |

243 |

1,122 |

125 |

| Test |

2,000 |

65,322 |

car |

38,910 |

19,860 |

1,256 |

| truck |

881 |

1,409 |

263 |

| bus |

473 |

1,991 |

279 |

| RDDTS |

600 |

19,296 |

car |

8,167 |

8,993 |

1,060 |

| truck |

112 |

290 |

87 |

| bus |

69 |

363 |

155 |

Table 2.

Computer configurations and environment.

Table 2.

Computer configurations and environment.

| Environment |

Parameter |

| CPU |

Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-10850K @3.60GHz |

| GPU |

NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 |

| Memory capacity |

32GB |

| Language |

Python 3.10.16 |

| Frame |

Pytorch 2.5.1 |

| CUDA Version |

12.4 |

Table 3.

Training parameters used in experiments.

Table 3.

Training parameters used in experiments.

| Training parameters |

Configuration |

| Optimizer |

SGD |

| Image size |

640×640 |

| Learning rate |

0.01 |

| Epoch |

300 |

| Batch size |

16 |

| Patience |

20 |

| NMS IoU |

0.7 |

| Weight-Decay |

5e-4 |

Table 4.

Results of Adding C3K2-H at Different Positions in YOLO11n.

Table 4.

Results of Adding C3K2-H at Different Positions in YOLO11n.

| Data |

Backbone |

Neck |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

Para(M) |

FPS |

| Val |

× |

× |

0.802 |

60.5 |

0.690 |

0.674 |

0.469 |

2.58 |

599.1 |

| √ |

× |

0.796 |

0.612 |

0.692 |

0.679 |

0.467 |

2.57 |

554.6 |

| × |

√ |

0.814 |

0.607 |

0.695 |

0.680 |

0.475 |

2.53 |

571.0 |

| √ |

√ |

0.791 |

0.622 |

0.696 |

0.683 |

0.481 |

2.79 |

521.6 |

| Test |

× |

× |

0.805 |

0.623 |

0.702 |

0.690 |

0.486 |

2.58 |

669.3 |

| √ |

× |

0.828 |

0.626 |

0.713 |

0.698 |

0.492 |

2.57 |

656.9 |

| × |

√ |

0.815 |

0.638 |

0.716 |

0.702 |

0.495 |

2.53 |

670.7 |

| √ |

√ |

0.822 |

0.631 |

0.714 |

0.700 |

0.490 |

2.79 |

590.4 |

Table 5.

Results on the test set using different wavelet bases in the neck network.

Table 5.

Results on the test set using different wavelet bases in the neck network.

| Wavelet bases |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

mAP@0.5 |

mAP@0.5:0.95 |

Params (M) |

FPS |

| Haar (db1) |

0.815 |

0.638 |

0.716 |

0.702 |

0.495 |

2.53 |

670.7 |

| Db4 |

0.809 |

0.631 |

0.709 |

0.695 |

0.487 |

2.61 |

650.4 |

| Db6 |

0.806 |

0.629 |

0.707 |

0.692 |

0.485 |

2.68 |

623.1 |

| Sym4 |

0.811 |

0.633 |

0.711 |

0.698 |

0.490 |

2.60 |

663.5 |

| Coif1 |

0.808 |

0.630 |

0.708 |

0.694 |

0.486 |

2.57 |

659.8 |

Table 6.

Ablation results of the CEHSA module and its variants on YOLO11n.

Table 6.

Ablation results of the CEHSA module and its variants on YOLO11n.

| Data |

Attention |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

Para(M) |

FPS |

| Val |

MSHA (baseline) |

0.802 |

0.605 |

0.690 |

0.674 |

0.469 |

2.58 |

599.1 |

| CAA |

0.811 |

0.616 |

0.700 |

0.687 |

0.482 |

2.56 |

600.9 |

| MSHA→CAA |

0.77 |

0.592 |

0.669 |

0.660 |

0.457 |

2.57 |

590.0 |

| CAA+MSHA(Parallel) |

0.805 |

0.622 |

0.702 |

0.689 |

0.483 |

2.68 |

569.9 |

| CEHSA |

0.825 |

0.616 |

0.705 |

0.692 |

0.486 |

2.57 |

595.4 |

| Test |

MSHA (baseline) |

0.805 |

0.623 |

0.702 |

0.690 |

0.486 |

2.58 |

669.3 |

| CAA |

0.812 |

0.642 |

0.717 |

0.705 |

0.499 |

2.56 |

671.3 |

| MSHA→CAA |

0.798 |

0.606 |

0.689 |

0.673 |

0.467 |

2.57 |

673.2 |

| CAA+MSHA (Parallel) |

0.815 |

0.631 |

0.711 |

0.702 |

0.498 |

2.68 |

654.4 |

| CEHSA |

0.824 |

0.641 |

0.721 |

0.707 |

0.502 |

2.57 |

675.1 |

Table 7.

Ablation results of the CEHSA module on other models.

Table 7.

Ablation results of the CEHSA module on other models.

| Data |

Model |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

| Test |

YOLOv5n |

0.804 |

0.592 |

0.682 |

0.666 |

0.461 |

| YOLOv8n |

0.794 |

0.599 |

0.683 |

0.662 |

0.46 |

| YOLOv5n+CEHSA |

0.807 |

0.608 |

0.694 |

0.678 (+1.2%) |

0.473 (+1.2%) |

| YOLOv8n+CEHSA |

0.807 |

0.621 |

0.702 |

0.688 (+2.6%) |

0.484 (+1.8%) |

| RDDTS |

YOLOv5n |

0.494 |

0.397 |

0.440 |

0.388 |

0.248 |

| YOLOv8n |

0.527 |

0.38 |

0.442 |

0.399 |

0.252 |

| YOLOv5n+CEHSA |

0.547 |

0.386 |

0.453 |

0.408 (+2.0%) |

0.26 (+1.2%) |

| YOLOv8n+CEHSA |

0.580 |

0.381 |

0.460 |

0.418 (+1.9%) |

0.268 (+1.6%) |

Table 8.

Ablation Experiment of HA-YOLOn.

Table 8.

Ablation Experiment of HA-YOLOn.

| Data |

C3K2-H |

CEHSA |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

Para(M) |

FPS |

| Val |

× |

× |

0.802 |

0.605 |

0.690 |

0.674 |

0.469 |

2.58 |

599.1 |

| √ |

× |

0.814 |

0.607 |

0.695 |

0.68 |

0.475 |

2.53 |

571.0 |

| × |

√ |

0.810 |

0.618 |

0.701 |

0.692 |

0.484 |

2.57 |

595.4 |

| √ |

√ |

0.812 |

0.627 |

0.708 |

0.695 |

0.487 |

2.56 |

588.2 |

| Test |

× |

× |

0.805 |

0.623 |

0.702 |

0.69 |

0.486 |

2.58 |

680.0 |

| √ |

× |

0.815 |

0.638 |

0.716 |

0.702 |

0.495 |

2.53 |

670.7 |

| × |

√ |

0.824 |

0.641 |

0.721 |

0.707 |

0.502 |

2.57 |

675.1 |

| √ |

√ |

0.837 |

0.642 |

0.727 |

0.712 |

0.506 |

2.56 |

649.5 |

Table 9.

Ablation Experiment of HA-YOLOs.

Table 9.

Ablation Experiment of HA-YOLOs.

| Data |

C3K2-H |

CEHSA |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

Para(M) |

FPS |

| Val |

× |

× |

0.849 |

0.679 |

0.754 |

0.740 |

0.537 |

9.41 |

388.7 |

| √ |

× |

0.845 |

0.682 |

0.755 |

0.749 |

0.541 |

9.16 |

384.5 |

| × |

√ |

0.841 |

0.679 |

0.751 |

0.748 |

0.541 |

9.32 |

394.2 |

| √ |

√ |

0.866 |

0.679 |

0.761 |

0.754 |

0.551 |

9.21 |

382.4 |

| Test |

× |

× |

0.847 |

0.681 |

0.755 |

0.745 |

0.543 |

9.41 |

455 |

| √ |

× |

0.853 |

0.677 |

0.755 |

0.751 |

0.547 |

9.16 |

444.2 |

| × |

√ |

0.860 |

0.683 |

0.761 |

0.757 |

0.554 |

9.32 |

456.0 |

| √ |

√ |

0.859 |

0.686 |

0.763 |

0.760 |

0.558 |

9.21 |

446.0 |

Table 10.

Comparison of detection performance at different object scales (small, medium, large) between HA-YOLO and the baseline model on the RDDTS dataset.

Table 10.

Comparison of detection performance at different object scales (small, medium, large) between HA-YOLO and the baseline model on the RDDTS dataset.

| Methods |

APs

|

APm

|

APl

|

MaxDets |

| YOLO11n |

0.110 |

0.313 |

0.402 |

100 |

| YOLO11s |

0.145 |

0.331 |

0.456 |

100 |

| HA-YOLOn |

0.124 (+1.2%) |

0.328 (+2.2%) |

0.455(+5.3%) |

100 |

| HA-YOLOs |

0.158 (+1.1%) |

0.364 (+3.3%) |

0.502(+4.6%) |

100 |

Table 11.

Comparison with Other Algorithms on the Test Set.

Table 11.

Comparison with Other Algorithms on the Test Set.

| model |

mAP50 |

map50-95 |

GFLOPS |

FPS |

Para(M) |

| car |

truck |

bus |

all |

| DAB DETR [41]* |

0.368 |

0.151 |

0.423 |

0.313 |

- |

97.2 |

- |

43.70 |

| RT-DETR-l [40] |

0.757 |

0.203 |

0.667 |

0.542 |

0.330 |

103.4 |

121.3 |

31.99 |

| Deform DETR [42]* |

0.588 |

0.341 |

0.629 |

0.519 |

- |

192.5 |

- |

40.01 |

| YOLOv5n |

0.833 |

0.404 |

0.762 |

0.666 |

0.461 |

7.1 |

714.1 |

2.50 |

| YOLOv5s |

0.865 |

0.515 |

0.808 |

0.729 |

0.526 |

23.8 |

464.4 |

9.11 |

| YOLOv8n |

0.831 |

0.394 |

0.762 |

0.662 |

0.460 |

8.1 |

673.0 |

3.00 |

| YOLOv8s |

0.867 |

0.506 |

0.807 |

0.727 |

0.527 |

28.4 |

443.0 |

11.13 |

| YOLOv12n [39] |

0.841 |

0.431 |

0.776 |

0.682 |

0.478 |

6.3 |

265.2 |

2.56 |

| YOLOv12s [39] |

0.859 |

0.505 |

0.812 |

0.726 |

0.524 |

21.2 |

228.0 |

9.23 |

| YOLO11n |

0.840 |

0.449 |

0.781 |

0.690 |

0.486 |

6.3 |

680.0 |

2.58 |

| YOLO11s |

0.874 |

0.539 |

0.823 |

0.745 |

0.547 |

21.3 |

455.0 |

9.41 |

| HA-YOLOn |

0.849 |

0.488 |

0.800 |

0.712 |

0.506 |

6.3 |

649.5 |

2.56 |

| HA-YOLOs |

0.875 |

0.566 |

0.838 |

0.760 |

0.554 |

21.1 |

446.0 |

9.21 |

Table 12.

Comparison with Other Algorithms on the RDDTS Dataset.

Table 12.

Comparison with Other Algorithms on the RDDTS Dataset.

| model |

mAP50 |

map50-95 |

GFLOPS |

FPS |

Para(M) |

| car |

truck |

bus |

all |

| DAB DETR [41]* |

0.222 |

0.023 |

0.112 |

11.7 |

- |

97.2 |

- |

43.70 |

| RT-DETR-l [40] |

0.696 |

0.062 |

0.187 |

0.315 |

0.178 |

103.4 |

117.3 |

31.99 |

| Deform DETR [42]* |

0.463 |

0.112 |

0.219 |

0.265 |

- |

192.5 |

- |

40.01 |

| YOLOv5n |

0.744 |

0.123 |

0.297 |

0.388 |

0.248 |

7.1 |

404.3 |

2.50 |

| YOLOv5s |

0.788 |

0.194 |

0.38 |

0.454 |

0.303 |

23.8 |

330.8 |

9.11 |

| YOLOv8n |

0.754 |

0.144 |

0.300 |

0.399 |

0.252 |

8.1 |

389.1 |

3.00 |

| YOLOv8s |

0.798 |

0.178 |

0.362 |

0.446 |

0.298 |

28.4 |

332.8 |

11.13 |

| YOLOv12n [39] |

0.764 |

0.144 |

0.303 |

0.404 |

0.259 |

6.3 |

160.0 |

2.56 |

| YOLOv12s [39] |

0.802 |

0.200 |

0.392 |

0.465 |

0.314 |

21.2 |

144.0 |

9.23 |

| YOLO11n |

0.764 |

0.144 |

0.337 |

0.415 |

0.272 |

6.3 |

371.2 |

2.58 |

| YOLO11s |

0.813 |

0.173 |

0.365 |

0.450 |

0.303 |

21.3 |

310.0 |

9.41 |

| HA-YOLOn |

0.779 |

0.165 |

0.389 |

0.444 |

0.289 |

6.3 |

355.7 |

2.56 |

| HA-YOLOs |

0.820 |

0.206 |

0.435 |

0.487 |

0.327 |

21.1 |

303.5 |

9.21 |

Table 13.

Comparison with other fog-specific detectors.

Table 13.

Comparison with other fog-specific detectors.

| Method |

Para(M) |

GFLOPS |

AP on Test-set |

AP on RDDTS |

| car |

truck |

bus |

mAP |

car |

truck |

bus |

mAP |

| IDOD-YOLOv7 [27]* |

46.5 |

93.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| IA-YOLO [26]* |

62.5 |

75.3 |

0.441 |

0.222 |

0.486 |

0.383 |

0.419 |

0.08 |

0.173 |

0.224 |

| HA-YOLOn |

2.56 |

6.3 |

0.849 |

0.488 |

0.800 |

0.712 |

0.779 |

0.165 |

0.389 |

0.444 |

| HA-YOLOs |

9.21 |

21.1 |

0.875 |

0.566 |

0.838 |

0.760 |

0.820 |

0.206 |

0.435 |

0.487 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).