1. Introduction

Cancer patients commonly experience several symptoms linked to the disease and the side effects of treatments, which negatively impact their quality of life (QoL). Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms reported by patients and can profoundly affect QoL and physical functioning [

1,

2]. Several strategies have been employed to counteract CRF, such as corticosteroids, progestins, physical therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapy, acupuncture, nutrition counseling, and a wide range of oral supplements [

3,

4].

Levo-arginine (l-Arg) is an oral supplement with ergogenic properties that promotes muscle hypertrophy and strength gains in healthy individuals while preventing muscle wasting in conditions that lead to atrophy, such as aging or periods of disuse [

5]. L-Arg is a dibasic, cationic, semi-essential amino acid synthesized endogenously from glutamine, glutamate, and proline. It intervenes in various metabolic functions, including protein synthesis, immune system support, and circulation enhancement [

6,

7]. L-Arg is an intermediate in the urea cycle and a precursor for protein, polyamines, and creatine. Additionally, it is the sole precursor for the biosynthesis of the multifunctional messenger nitric oxide (NO), which biological effects are complex and depend on various regulatory factors. L-Arg can be metabolized into NO and L-citrulline by inducible nitric oxide synthase or into urea and L-ornithine by the type 1 isoform of cytosolic arginase, which is primarily expressed in the liver as part of the urea cycle [

6,

7]. NO has vasodilator activity, enhancing circulation and enabling the delivery of more oxygen and nutrients to the muscular tissues, which may lower weariness, particularly during physical activity. Improved sleep quality is one possible indirect benefit, as enhanced circulation and nutrient delivery support the body’s rest and recovery, which can help reduce asthenia. L-Arg supplementation may improve physical performance and recovery by diminishing exercise-induced fatigue [

5]. However, individual health issues, dietary preferences, and physical activity levels can all affect the outcomes. L-Arg is classified among supplements with evidence B level, i.e., mixed evidence and/or few randomized clinical trials, suggesting caution since high doses (3- 20 gr/day) may cause gastrointestinal side effects and decrease arterial blood pressure [

8].

While NO was initially identified in endothelial cells, it is now recognized as being produced by various cell types, including several tumor cell lines and solid human tumors. L-Arg has complex relationships with cancer metabolism and is still under research [

9,

10]. Unfortunately, the precise role of NO in cancer remains poorly understood; however, some evidence suggests that it may influence tumor initiation, promotion, progression, tumor-cell adhesion, apoptosis, angiogenesis, differentiation, chemosensitivity, radiosensitivity, and tumor-induced immunosuppression. L-Arg may also support immune function, which is crucial for combating cancer cells [

10]. In fact, l-Arg is involved in several cellular functions, including immunomodulation, which regulates T-lymphocyte and natural killer cell activity, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, and the anti-tumor response [

11,

12,

13]. L-Arg-induced NO production enhances immune cells’ ability to target and kill cancer cells. L-Arg depletion can impair T-cell response in the tumor microenvironment, while L-Arg supplementation may enhance the anti-tumor immune response. Moreover, L-Arg is involved in the urea cycle and helps remove ammonia from the body, potentially reducing fatigue and improving energy levels.

In medical literature, clinical research on L-Arg, specifically for CRF, is limited. Most evidence derives from its general effects on energy metabolism and physical performance. This exploratory, basket paper examines the impact of l-Arg combined with vitamin C in a cohort of cancer patients with CRF undergoing antineoplastic treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a prospective observational study on the effect of l-Arg arginine plus vitamin C (l-Arg/Vit-C) on cancer-related fatigue, quality of life, and appetite. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kore University of Enna, Enna, Italy. Six institutions participated in the study. The primary endpoint included evaluating the effect of l-Arg/liposomal vitamin C on CRF starting from the basal first evaluation of fatigue before beginning treatment (T0) and after 15 (T1), 30, and 60 days (T2, T3). CRF is characterized by an overwhelming sense of tiredness and exhaustion that doesn’t improve with rest or sleep. It’s a distressing, persistent, and subjective experience that interferes with daily activities and overall functioning. Unlike normal fatigue, CRF is often not proportional to recent activity and can affect physical, emotional, and cognitive well-being. The effects of QoL and appetite were evaluated at basal, T2 and T3.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible patients had to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: diagnosis of advanced solid tumor undergoing chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy, age ≥18 years, absence of heart failure, chronic breathing impairment requiring oxygen supplementation, end-stage renal disease, severe intestinal inflammatory diseases, uncontrolled metabolic, neurological or psychiatric diseases, hemoglobin level >10 gr/dl or known allergy to soy.

2.3. Treatment

Patients received 1.66 g of oral L-Arg and 500 mg of vitamin C in 20 ml oral solution twice daily. They were required to electronically report all adverse events, such as increased stool frequency or diarrhea.

2.4. Activity Evaluation

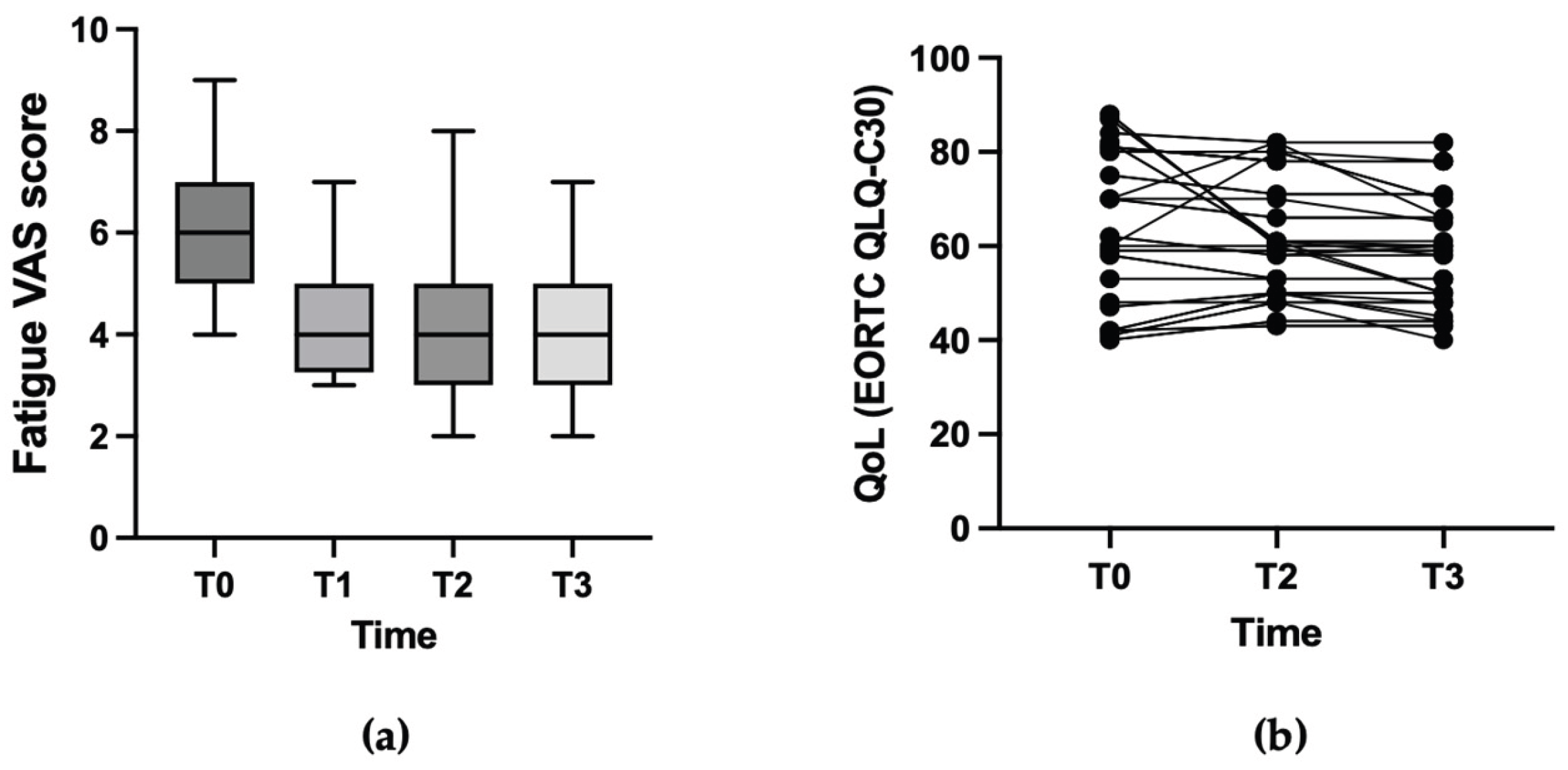

The treating oncologists prescribed visits at their discretion, evaluating each case individually. The single-question assessment is the most used and valuable methodology; therefore, enrolled patients self-evaluated their fatigue using the fatigue visual analog scale (VAS), scoring it from 0 - no fatigue to 10 – extreme fatigue, as previously described (

Figure 1). A variation of 1 point on the fatigue VAS was considered a minimally significant difference (MID) for symptom improvement. The treating oncologist, nurse, or data manager administered the VAS to patients during control visits before (T0), after 2 weeks (T1), and after 4 and 8 weeks (T2, and T3).

Health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire, which includes five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), nine symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties), and global health status/QoL. HR-QoL was assessed using a standardized score for global health status/QoL, ranging between 0 and 100, with a high standardized score representing a high HR-QoL level. The minimal significant difference (MID) was defined as a change of 10 points, with an increase of at least 10 points considered a clinically significant improvement in HR-QoL at both the individual and group levels [

13,

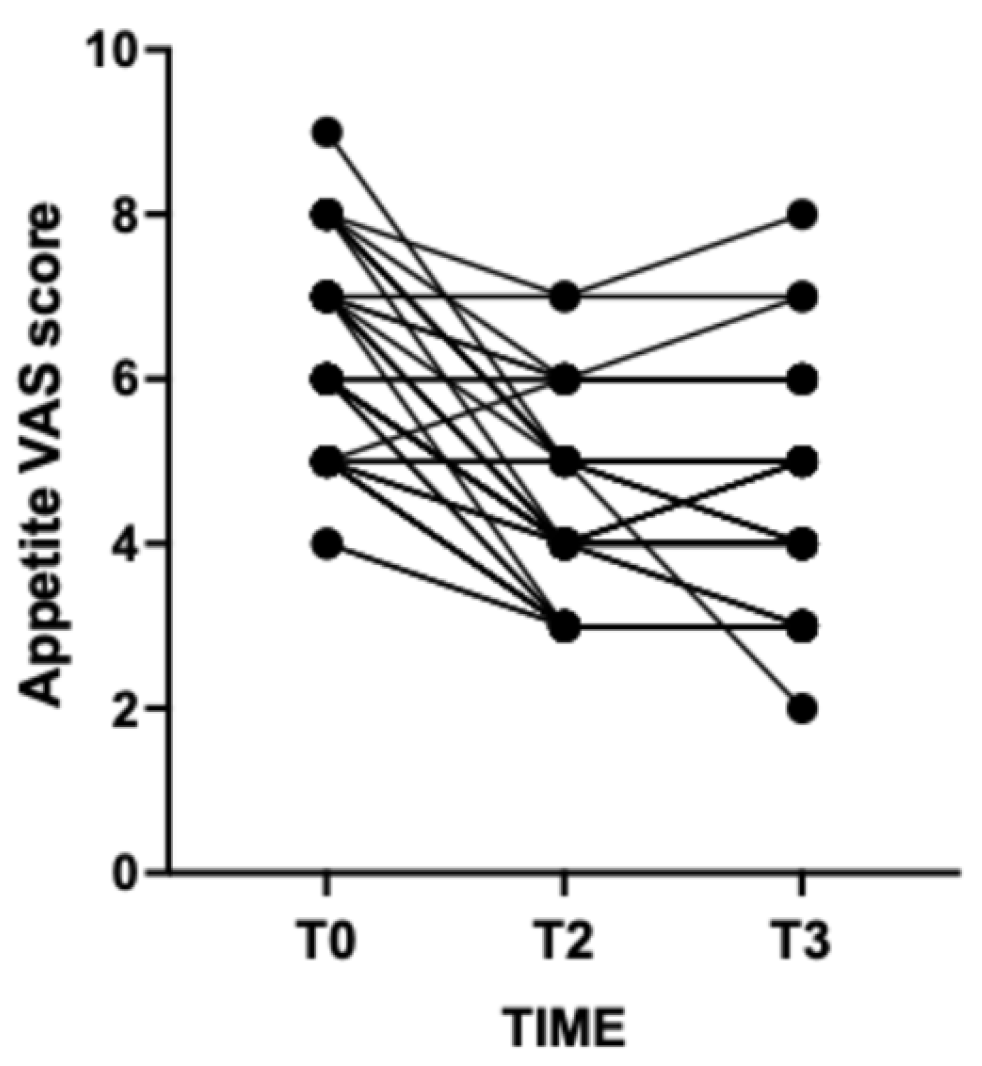

18]. A VAS ranging from 0 (not hungry at all) to 10 (very hungry) was employed to measure self-reported patients’ appetite at T0, T2, and T3. Patients and their caregivers were asked to report their satisfaction regarding the effect of oral supplementation (unsatisfied, mild satisfaction, highly satisfied).

2.5. Statistics

Descriptive data were reported as absolute numbers with their relative percentages rounded to the nearest unit or, in the case of intermediate values, to the highest one. Comparison between points was carried out employing a one-way Anova test, with mean adjusted to the nearest decimal unit A GraphPad statistical software (GraphPad, Boston, MA, USA) was employed for statistical analysis and graph creation.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

Table 1 shows the main clinical and demographic characteristics of enrolled patients. Briefly, there were 44 patients enrolled in 5 different institutions from January to June 2024. Patients were 20 males and 24 females with a median age of 59 years (range 28-79) and a median ECOG performance status of 1 (range 1-2). Primary tumors included breast cancer (45%), 10 lung cancer (23%), prostatic cancer (18%), colorectal cancer (9%), and renal carcinoma (5%). Anticancer treatments concomitant to oral supplementation with l-Arg/Vit-C included chemotherapy in 27 patients (61%), tyrosine kinase inhibitors in 4 patients (0.9%), simultaneous chemoradiation in 2 patients (5%), androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSI) in 4 cases (0.9%) and immunotherapy in 3 cases (7%).

Table 1 shows also all treatment regimens employed.

3.2. Activity of L-Arginine/Vitamin C

Figure 1 shows the activity of l-Arg

ARG/vitamin C on CRF and on HrQoL. Basal mean fatigue score according to the VAS scale was 6.3 (range 4-9). After 15 days (T1), 30 days (T2), and 60 days (T3) fatigue score was 4.4 (range 3-7), 4.3 (range 2-8), and 3.9 (range 2-7) respectively. The variation between points was statistically significant (p<0.001). Mean basal HrQoL score was 64.3 (range 40-88). At T2 and T3 mean HrQoL scores were 61.4 (range 43-82), and59.3 (range 40-82). Despite a slight decrease, the observed difference was not statistically significant (p=0.2658). Therefore l-Arg/vitamin C supplementation was not associated to a deterioration in quality of life.

Figure 2 shows the effect of l-Arg/vitamin C on self-reported patients’ appetite. Basal appetite score was 6.27 (range 4-9). At T2 and T3 appetite score was 4.36 (range 3-7), and 4.29 (range 2-8) respectively. Appetite score remained stable or slightly improved in 8 patients (18%), while decreased in 82% of cases. Overall, 50% of patients and their primary caregiver reported to be highly satisfied, and 16% to be dissatisfied.

3.3. Safety

No patient reported any significant side-effect. Looser stools were reported by 2 patients only treated with capecitabine (5%). Cancer treatment-related toxicity was within the expected range without any suspicious reaction.

4. Discussion

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a common and debilitating symptom that most cancer patients experience during treatment and often for significant periods afterward [

1]. The impact of CRF on patients’ psychosocial and cognitive functioning and quality of life has led to the development of a wide array of assessment tools for screening and diagnosing CRF [

3]. A comprehensive and critical review of CRF identified more than 20 different fatigue measures that investigate unidimensional or multidimensional aspects of the issue [

14]. Unidimensional measures typically consist of single-question scales designed to capture the incidence and severity of CRF. In contrast, multidimensional measures assess its impact across various physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive domains [

14].

Despite the recommendations of most international guidelines for patients to receive information and education about CRF before starting treatment—screening and assessing which should be done using rating scales or questionnaires—patients remain poorly informed about this issue [

3,

15,

16]. Exercise or regular physical activity is the most employed method to alleviate CRF, often motivated by individual initiative rather than medical advice, which typically favors prescribing pharmacological agents like steroids, whose chronic use can lead to severe toxicity. Other mindfulness practices or physical therapy are only occasionally implemented, and psychological support alone seems ineffective.

Patients with cancer exhibit systemic inflammation, which increases protein catabolism and encourages the release of free amino acids to assist muscle protein remodeling and metabolism [

17,

18]. Malnutrition is a result of inflammation linked to tumor growth, and this raises the risk of cachexia and is related to fatigue. Therefore, nutritional therapies have gained popularity as a prophylactic strategy to manage cachexia caused by cancer [

19]. Hence, the rationale for using oral supplementation is the assumption that oral nutritional supplements may confer an ergogenic effect and enhance exercise capacity above and beyond that received through diet food ingestion alone [

20].

In some clinical settings, such as infection, burns, and surgery, the demand for arginine cannot be fully met by de novo synthesis and regular dietary intake. Arginine and glutamine may act by reducing inflammation and infection progression, thus promoting improvements in food intake [

18,

20,

21]. Creatine exerts anabolic activity, acting as an immediate energy substrate to support muscle contraction and further increase lean mass, mainly due to greater water uptake by the muscle. Orally supplemented l-Arg has been shown to improve endothelial dysfunction and reduce respiratory support and length of in-hospital stay versus placebo in patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19 [

22,

23]. A prospective study examined the effects of two l-Arg-based supplements on 500 patients with COVID-19 infection-related fatigue [

24]. The fatigue level assessed by the Fatigue Assessment Scale significantly decreased, suggesting that supplements with l-Arg may be proposed as a remedy to restore physical and mental performance affected by the fatigue burden in people with COVID-19. Perioperative immune-nutrition with added l-Arg significantly reduces the length of hospital stay and the incidence of infectious complications in cancer patients [

25,

26]

Several recent studies have indicated that Vit-C alleviates cancer and chemotherapy-related symptoms, such as fatigue, insomnia, loss of appetite, nausea, and pain [

27]. Improvements in physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning and overall health were also observed. Therefore, Vit-C is a potential partner for l-Arg. It has been reported that high NO levels in endothelial cells can enhance exercise performance. In murine models, supplementation with a combined extract containing l-Arg (along with L-glutamine, vitamin C, vitamin E, folic acid, and green tea extract) significantly increased serum NO levels in a dose-dependent manner and reduced fatigue [

28].

In the medical literature the reports of the role of l-Arg supplementation in cancer patients is limited. Eighty-eight patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck, esophageal, and cervical cancer were randomized to receive either a standard diet or a diet supplemented with l-Arg, glutamine, and fish oil [

29]. Patients who received the supplements had a higher therapy completion rate, less grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities, and longer survival compared to those who did not receive l-Arg.

Saligan et al. measured FACT-F fatigue scores before and during treatment and plasma arginase type 1 gene expression in 30 patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer receiving external-beam radiation therapy [

30]. Fatigue significantly worsened from baseline to the end of treatment, and its intensity was linked to the upregulation of plasma arginase type 1 gene expression. In contrast, genes associated with the adaptive immune functional pathway (CD28, CD27, CCR7, CD3D, CD8A, and HLA-DOB) were significantly downregulated. Radiation-induced upregulation of the plasma arginase type 1 gene may be crucial in intensifying fatigue through arginine deficiency and suppressing T-cell proliferation pathways.

The present non-comparative study demonstrates a statistically significant positive effect of oral l-Arg/vitamin C supplementation on CRF and HR-QoL scores. On the other hand, there was no positive effect oral l-arginine/vitamin C supplementation on appetite but in a minority of cases. However, our study has some limitations. The patient sample is relatively small and includes various tumor types, disease stage, and type of antineoplastic treatments, which are confounding factors since they may influence different responses to supplementation with l-Arg/vitamin C. Therefore, we are planning to test l-Arg/vitamin C supplementation in larger series selected for specific oncological diseases with more standardized entry criteria.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, above reported data support the use of l-Arg/vitamin C in counteracting CRF maintaining quality of life. This agent is very well tolerated and accepted by patients and their caregivers. However, further studies are needed in patients’ populations homogeneous for cancer type, antitumor therapy, clinical setting, and comorbid diseases such as diabetes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and M.R.V.; methodology, V.G.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, I.F., P.D., M.R.V., M.G., A.D.; data curation, V.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.G. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, V.G. and M.R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee, Kore University of Enna, Italy (protocol code P11/2023, and date of approval in November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made. available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRF |

Cancer-Related Fatigue |

| l-Arg |

Levo-Arginine |

| HR-QoL |

Health-Related Quality of Life |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Curt, G.A.; Breitbart, W.; Cella, D.; Groopman, J.E.; Horning, S.J.; Itri, L.M.; Johnson, D.H.; Miaskowski, C.; Scherr, S,L,; Portenoy, R.K.; Vogelzang, N.J. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist, 2000; 5, 353–360.

- Kang, Y.E.; Yoon, J.H.; Park, N.H.; Ahn, Y.C.; Lee, E.J.; Son, C.G. Prevalence of cancer-related fatigue based on severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN Cancer-related fatigue version 2, 2025. www.nccn.org/guidelines.

- Stone, P.; Candelmi, D.E.; Kandola, K.; Montero, L.; Smetham, D.; Suleman, S.; Fernando, A.; Rojí, R. Management of Fatigue in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2023, 24, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Morales, J.S.; Emanuele, E.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Lucia, A. Supplements with purported effects on muscle mass and strength. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 2983–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.N.; Jiang, Y.F.; Ru, N.; Lu, J,H,; Ding, B.; Wu, J.Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, A,J. Amino Acid Nutrition and Metabolism in Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.I.; La Bounty, P.M.; Roberts, M. he ergogenic potential of arginine. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2004, 1, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, D.S. Arginine and cancer. J. Nutr. 2004, 134 (10 Suppl), 2837S–2841S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szefel, J.; Danielak, A.; Kruszewski, W.J. Metabolic pathways of L-arginine and therapeutic consequences in tumors. Adv. Med. Sci. 2019, 64, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Quiceno, D.G.; Ochoa, A.C. L-arginine availability regulates T- lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood, 2007; 109, 1568–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte, V.; Zanovello, P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol, 2005; 5, 641–54. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, R.; Rieckmann, J.C.; Wolf, T.; et al. L-Arginine Modulates T Cell Metabolism and Enhances Survival and Anti-tumor Activity. Cell, 2016; 167, 829–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Pierre, P.; Figueroa-Moseley, C.D.; Kohli, S.; Fiscella, K., Palesh, O.G. Morrow GR. Assessment of cancer-related fatigue: implications for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Oncologist. 2007;12 Suppl 1:11-21.

- Di Meglio, A.; Charles, C.; Martin, E.; Havas, J.; Gbenou, A.; Flaysakier, J.D.; Martin, A.L.; Everhard, S.; Laas, E.; Chopin, N.; Vanlemmens, L.; Jouannaud, C.; Levy, C.; Rigal, O.; Fournier, M.; Soulie, P.; Scotte, F.; Pistilli, B.; Dumas, A.; Menvielle, G.; André, F.; Michiels, S.; Dauchy, S.; Vaz-Luis, I. Uptake of Recommendations for Posttreatment Cancer-Related Fatigue Among Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw, 2022; 7, 20(13). [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Bergbold, S.; Hermann, S.; Steindorf, K. Knowledge, perceptions, and management of cancer-related fatigue: the patients’ perspective. Support. Care. Cancer. 2021, 29, 2063–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragni, M.; Fornelli, C.; Nisoli, E.; Penna, F. Amino Acids in Cancer and Cachexia: An Integrated View. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.D.P.; Howell, S.L.; Teixeira, F.J. Pimentel GD. Dietary Amino Acids and Immunonutrition Supplementation in Cancer-Induced Skeletal Muscle Mass Depletion: A Mini-Review. Curr. Pharm. Des, 2020; 26, 970–978. [Google Scholar]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Laird, B.; Larsson, M.; Laviano, A.; Mühlebach, S.; Oldervoll, L.; Ravasco, P.; Solheim, T.S.; Strasser, F.; de van der Schueren, M.; Preiser, J.C.; Bischoff, S.C. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddon-Jones D, Børsheim E, Wolfe RR. Potential ergogenic effects of arginine and creatine supplementation. J Nutr. 2004, 134 (10 Suppl), 2888S-2894S; discussion 2895S.

- Buijs, N.; Luttikhold, J.; Houdijk, A.P.; van Leeuwen, P.A. The role of a disturbed arginine/NO metabolism in the onset of cancer cachexia: a working hypothesis. Curr. Med. Chem, 2012; 19, 5278-86. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino, G.; Coppola, A.; Izzo, R.; Annunziata, A.; Bernardo, M.; Lombardi, A.; Trimarco, V.; Santulli, G.; Trimarco, B. Effects of adding L-arginine orally to standard therapy in patients with COVID-19: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Results of the first interim analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 2021; 40, 101125. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan, J.; Kashyap, S.P.; Jacob, M.; Ollapally, A.; Idiculla, J.; Raj, J.M.; Thomas, T.; Kurpad, A.V. The effect of l-arginine supplementation on amelioration of oxygen support in severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2022; 52, 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Turcu-Stiolica, A.; Ionele, C.M.; Ungureanu, B.S.; Subtirelu, M.S. The Effects of Arginine-Based Supplements on Fatigue Levels following COVID-19 Infection: A Prospective Study in Romania. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arribas-López, E.; Zand, N.; Ojo, O.; Snowden, M.J.; Kochhar, T. The Effect of Amino Acids on Wound Healing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Arginine and Glutamine. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Y. The Effect of immunonutrition in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC. Cancer. 2023, 23, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Vissers, M.C.; Cook, J.S. The effect of intravenous vitamin C on cancer- and chemotherapy-related fatigue and quality of life. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Li, H.; Chiu, Y.S.; Huang, C.C.; Chen, W.C. Supplementation of L-Arginine, L-Glutamine, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Folic Acid, and Green Tea Extract Enhances Serum Nitric Oxide Content and Antifatigue Activity in Mice. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2020, 2020, 2020, 8312647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitapanarux, I.; Traisathit, P.; Chitapanarux, T.; Jiratrachu, R.; Chottaweesak, P.; Chakrabandhu, S.; Rasio, W.; Pisprasert, V.; Sripan, P. Arginine, glutamine, and fish oil supplementation in cancer patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A randomized control study. Curr. Probl. Cancer. 2020, 44, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saligan, L.N.; Lukkahatai, N.; Zhang, Z.J.; Cheung, C.W.; Wang, X.M. Altered Cd8+ T lymphocyte Response Triggered by Arginase 1: Implication for Fatigue Intensification during Localized Radiation Therapy in Prostate Cancer Patients. Neuropsychiatry (London). 2018, 8, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).