Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

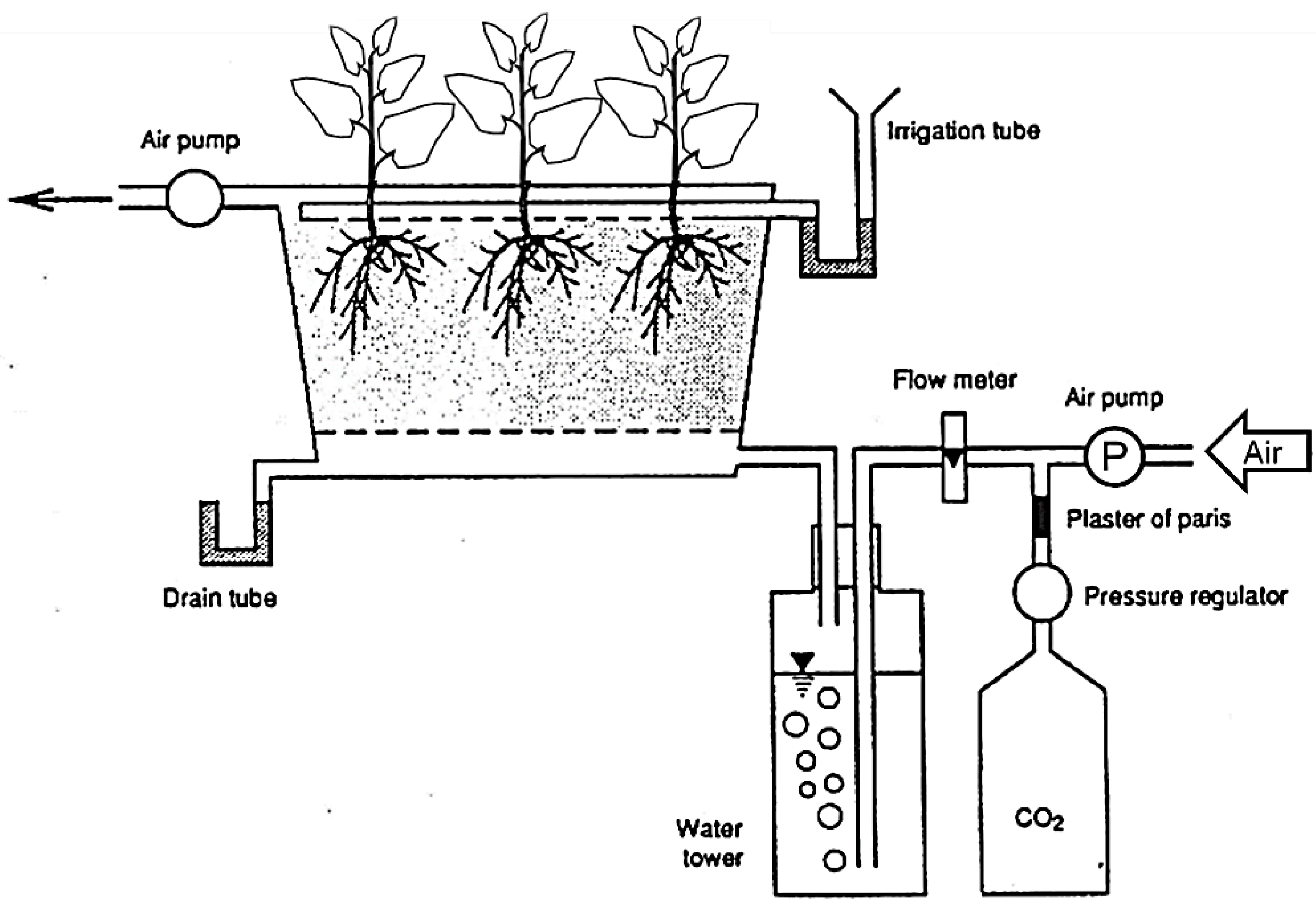

2.1. Effect of CO2 in the Rooting Zone on Net Photosynthetic Rate and Leaf Conductance

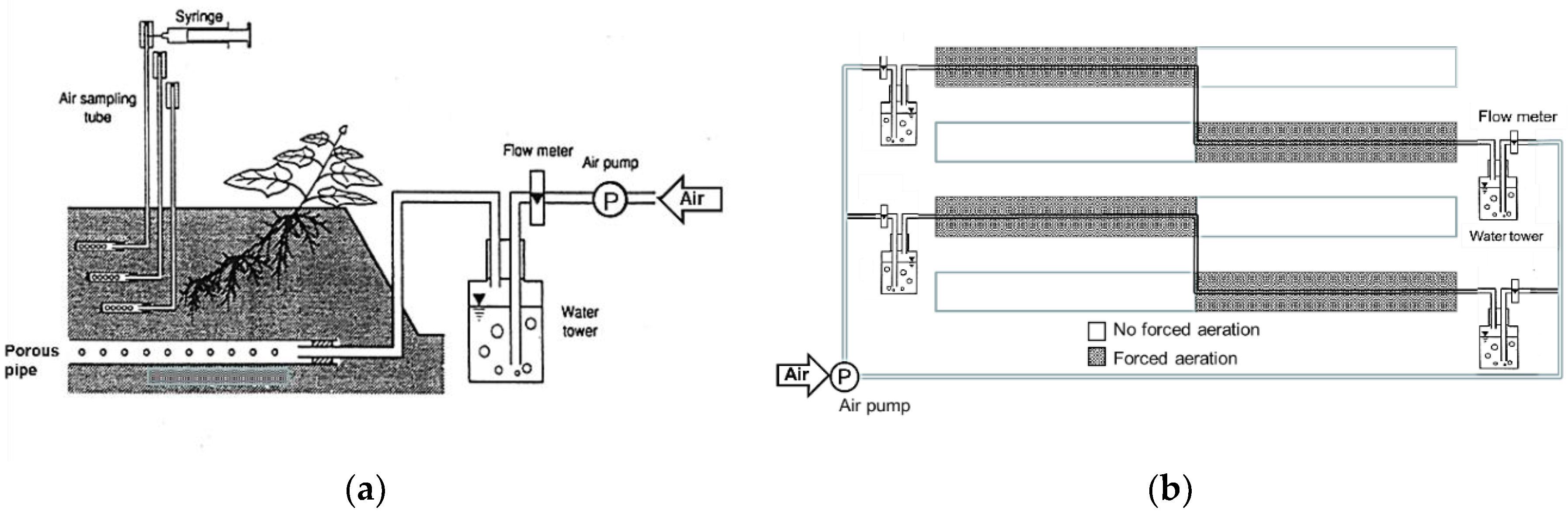

2.2. Effect of Forced Aeration on Sweet Potato Growth in Cultivation Ridges

2.3. Effect of Forced-Aeration Airflow Rates on Sweet Potato Growth in Cultivation Ridges

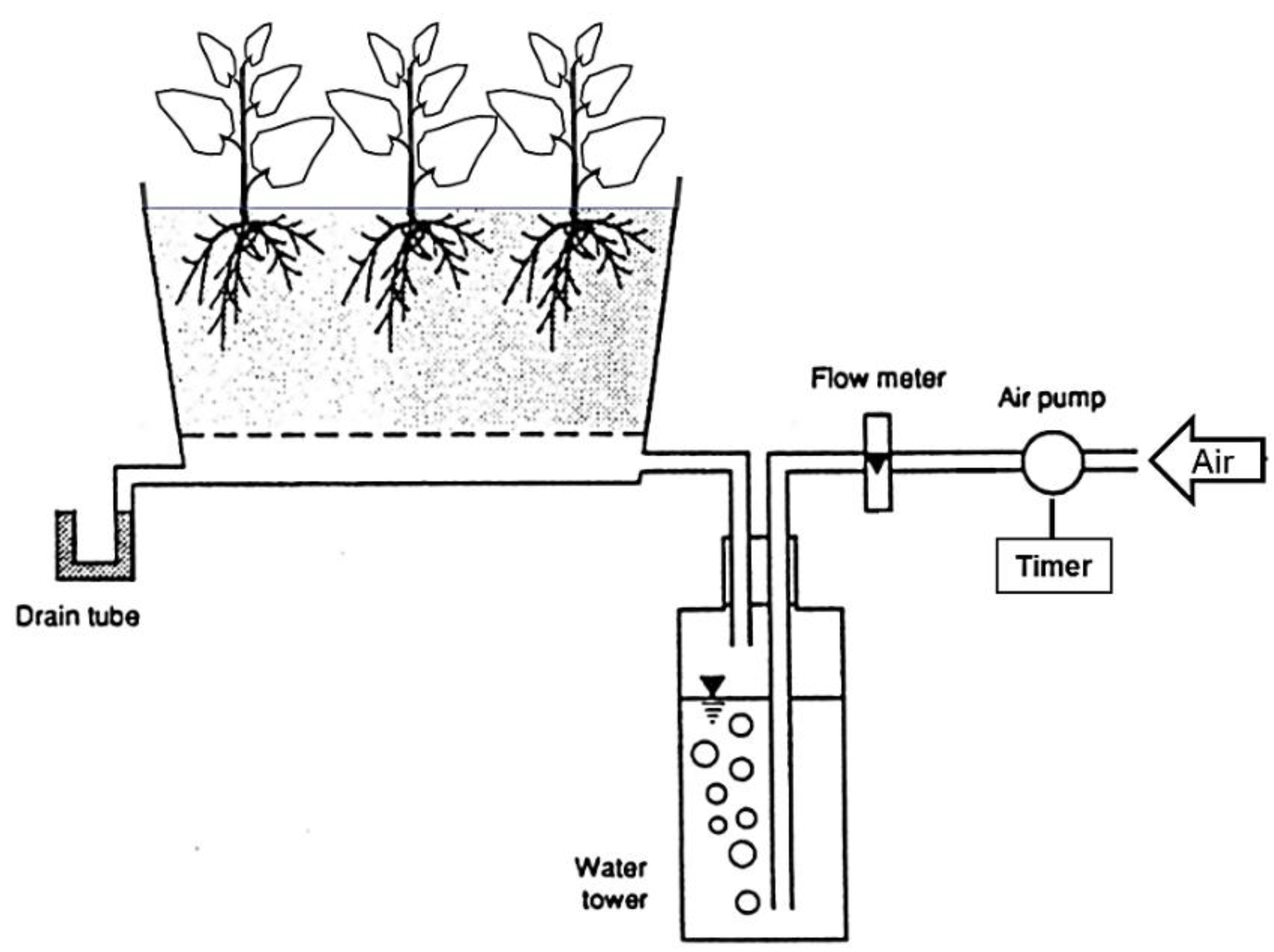

2.4. Effect of Forced-Aeration Time Intervals in the Rooting Zone on Sweet Potato Growth

3. Results

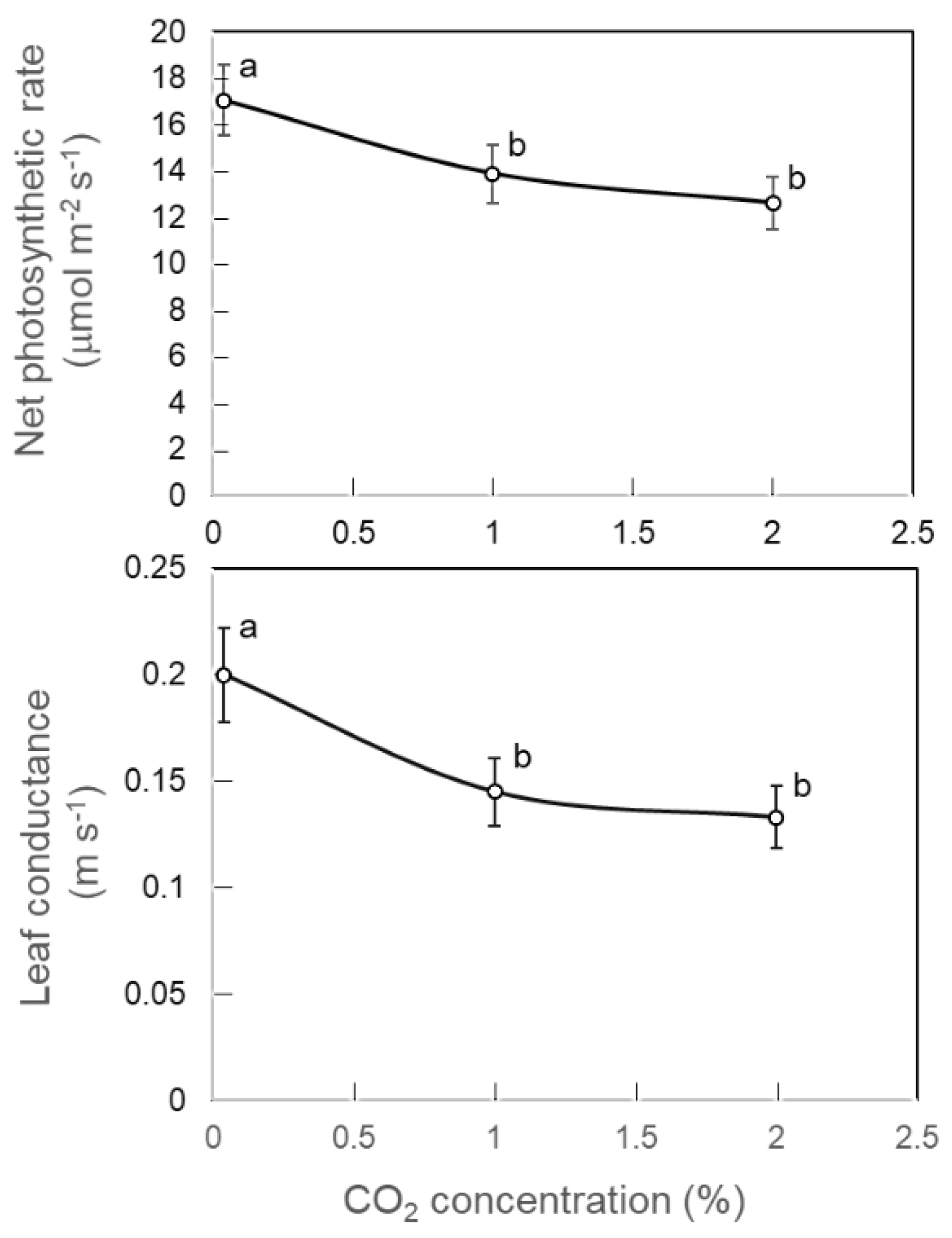

3.1. Effect of CO2 in the Rooting Zone on Net Photosynthetic Rate and Leaf Conductance

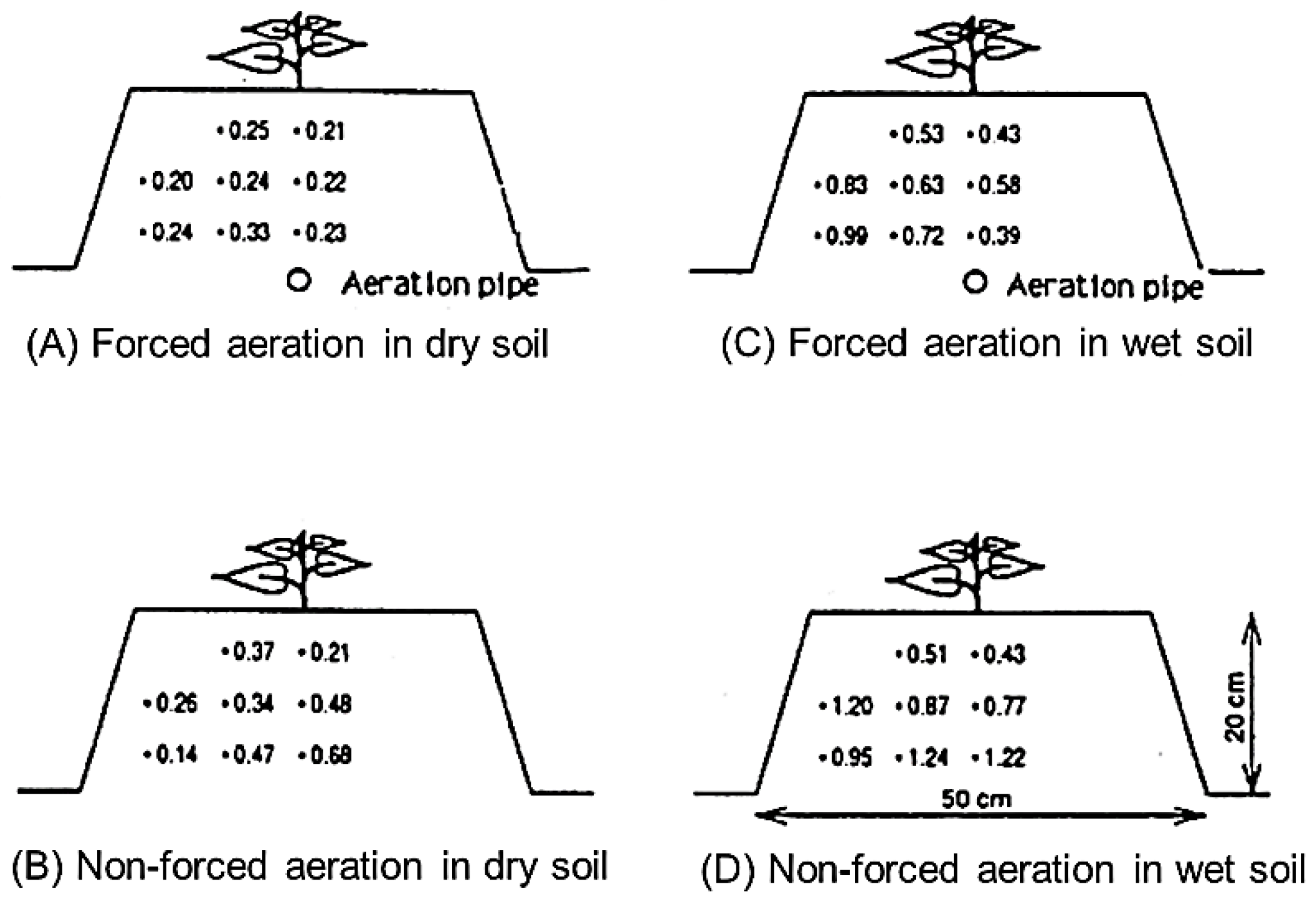

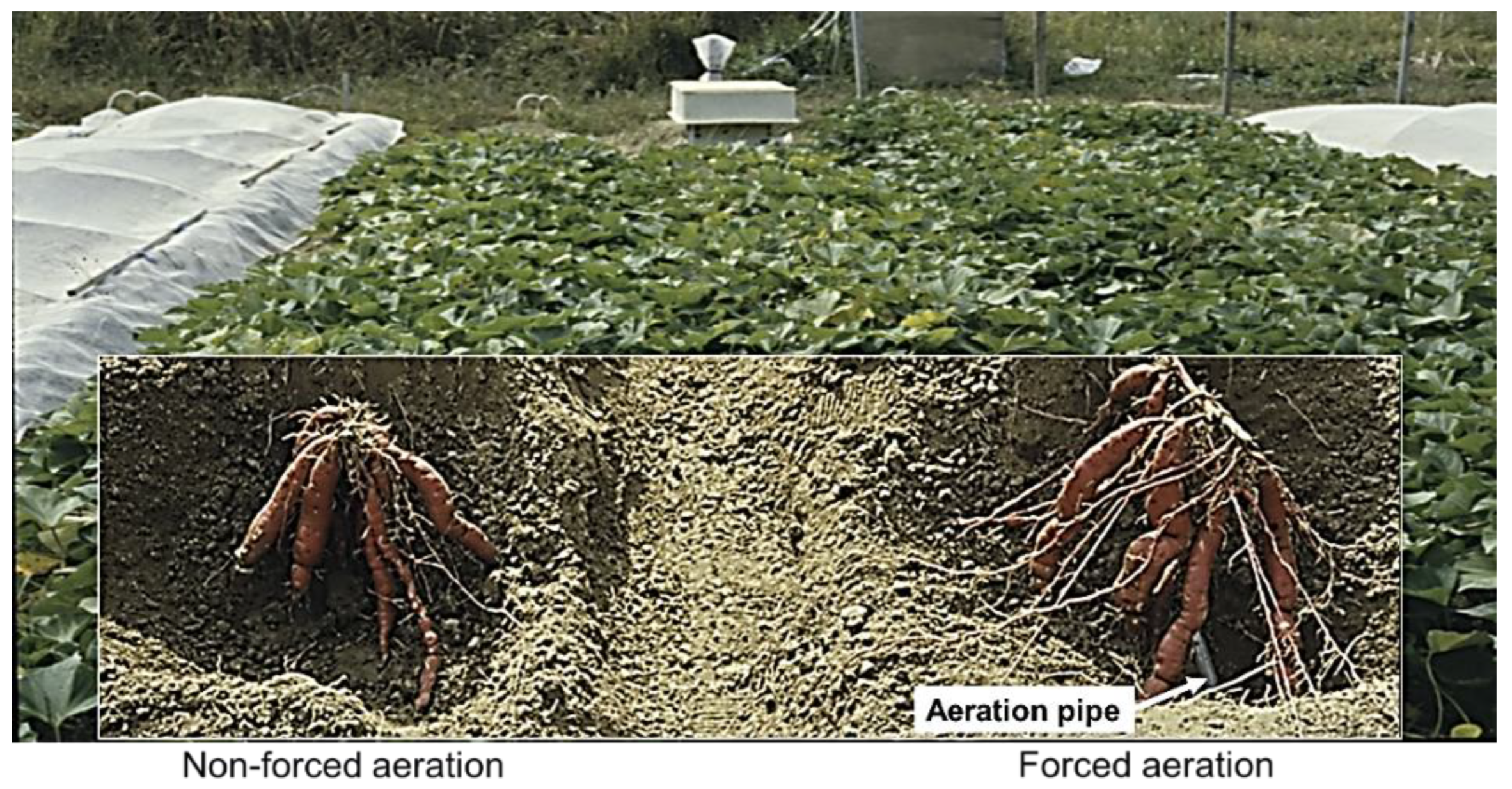

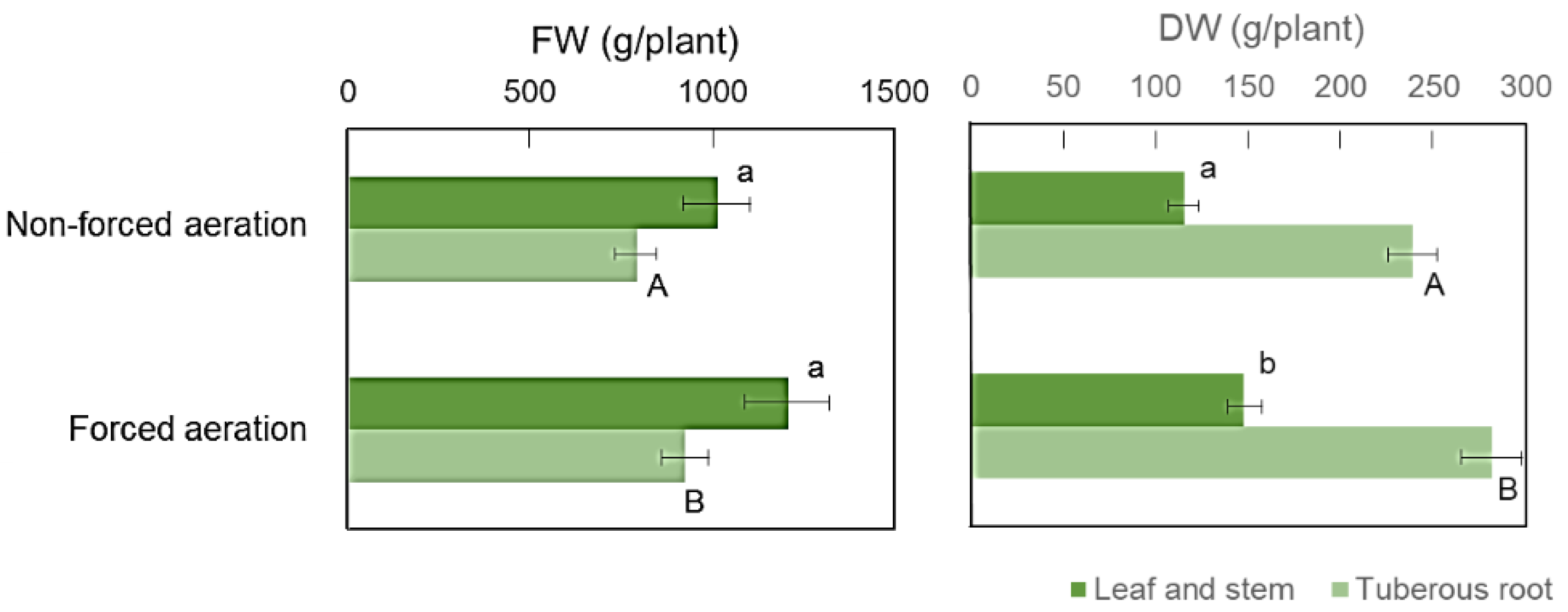

3.2. Effect of Forced Aeration in the Rooting Zone on Sweet Potato Growth

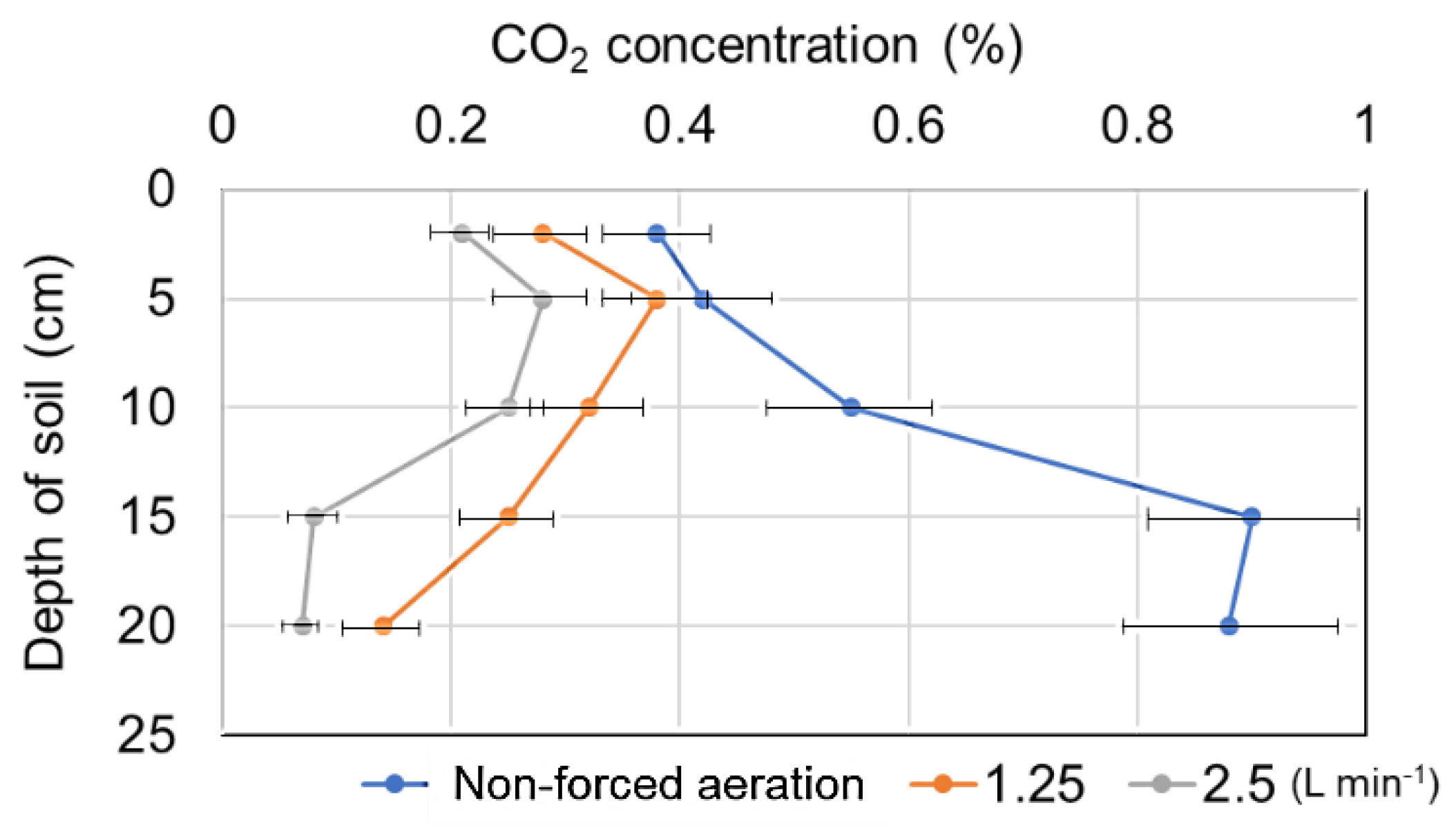

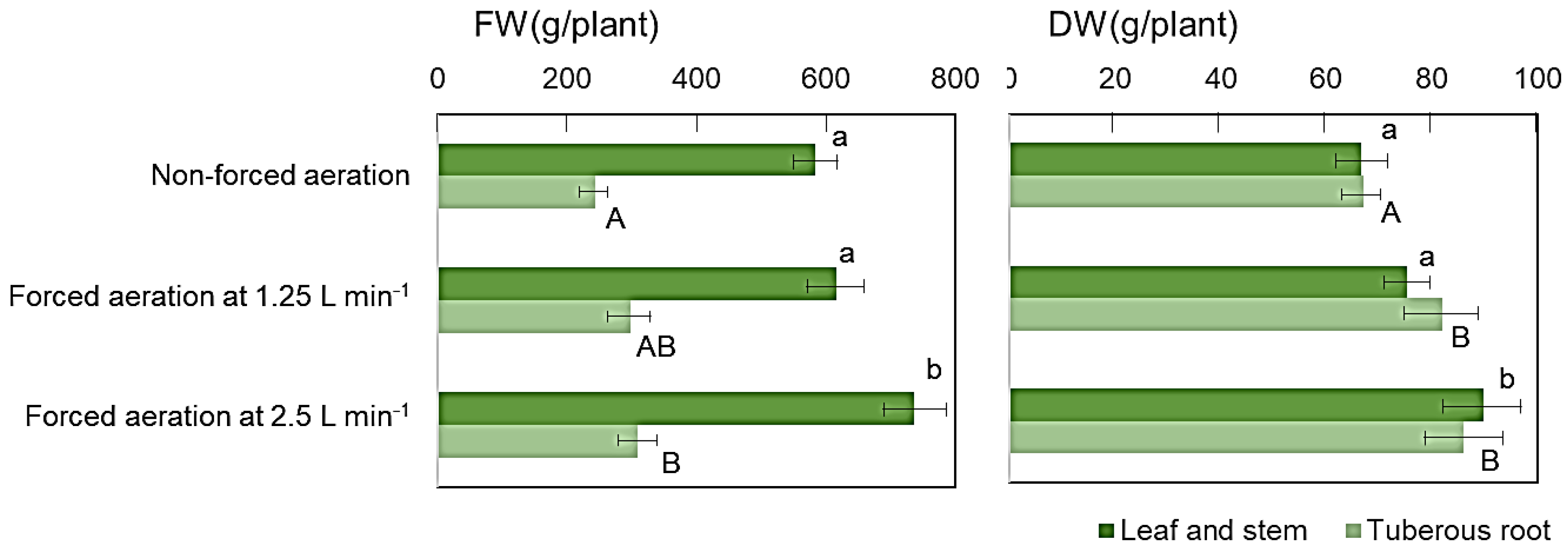

3.3. Effect of Forced Aeration Airflow Rates on Sweet Potato Growth in Cultivation Ridges

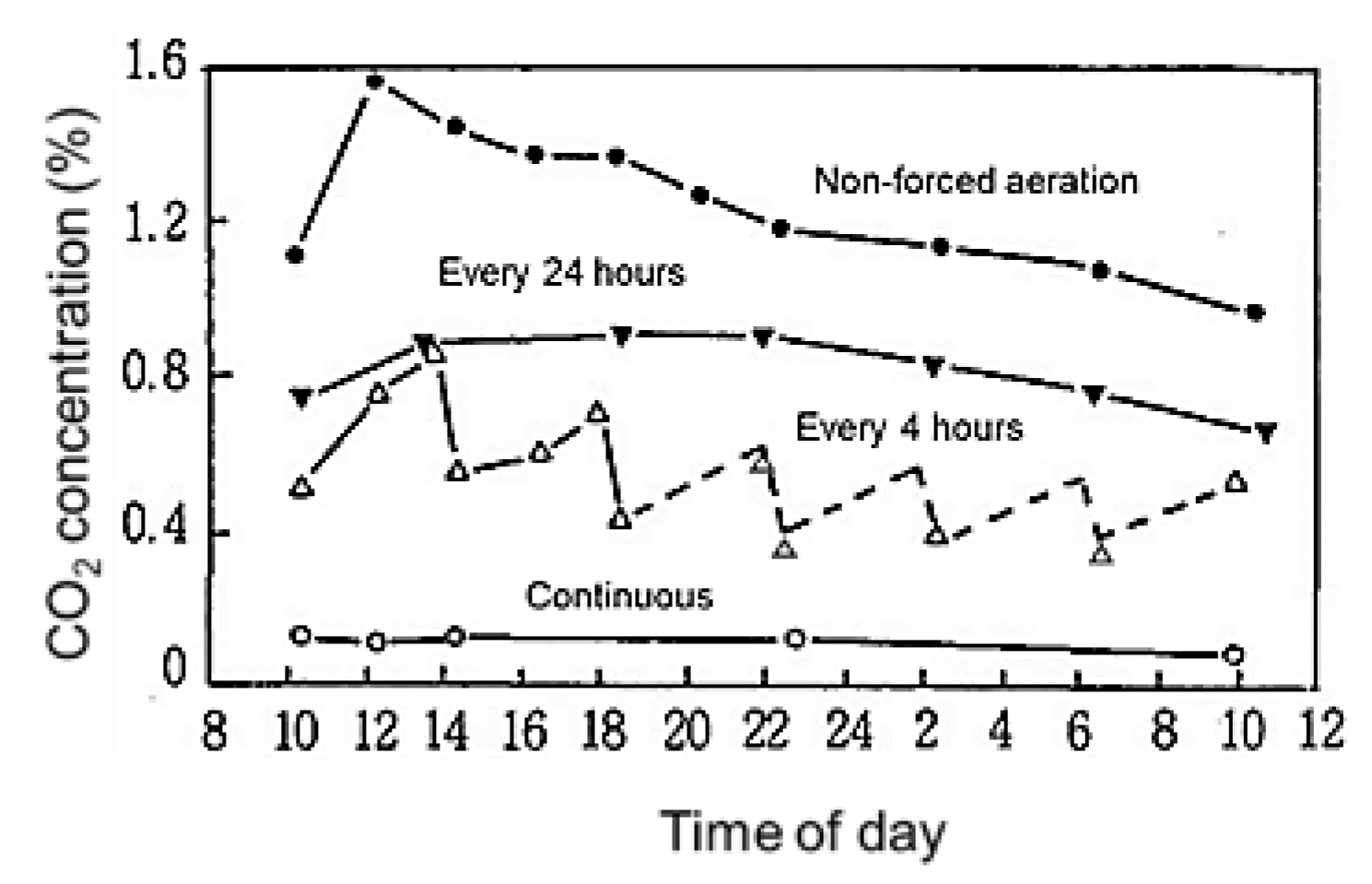

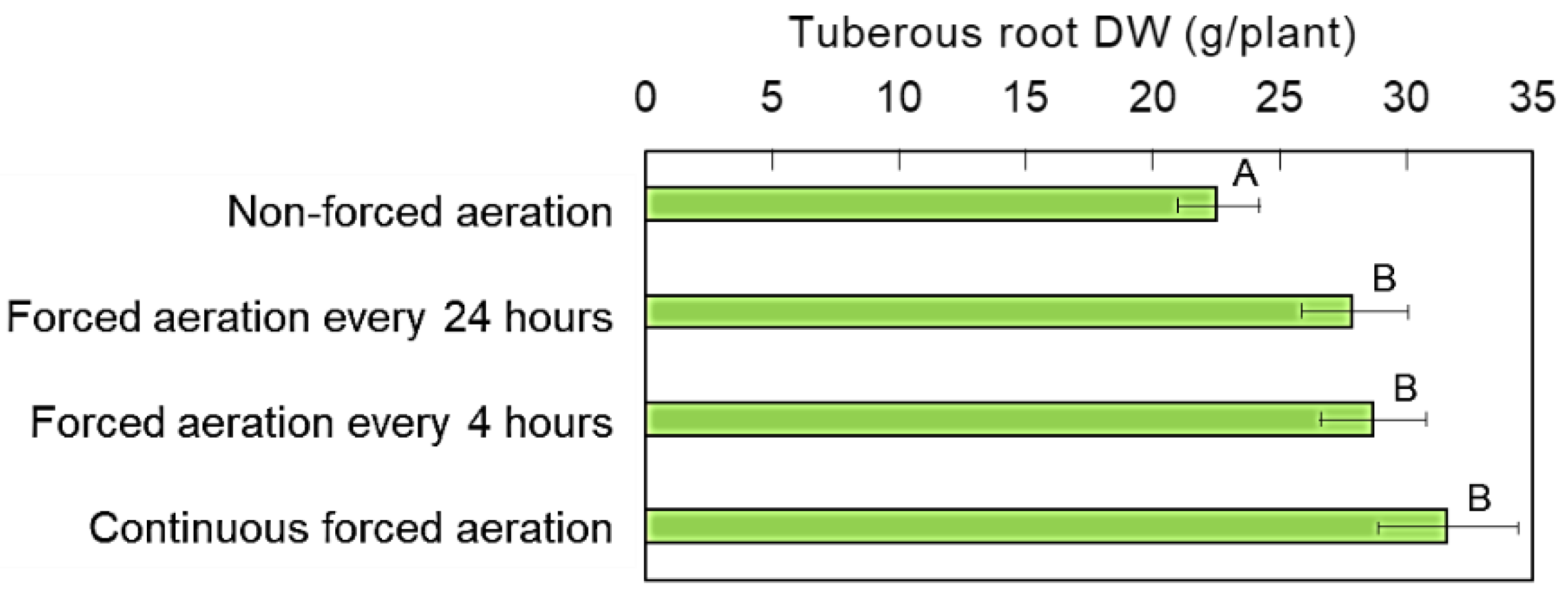

3.4. Effects of Forced-Aeration Time Intervals in the Rooting Zone on Sweet Potato Growth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2025: Monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization. 2025.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/11189609-7fd0-49c7-b234-eef18ab7ed17/content.

- Cheung, J. T. H.; Lok, J.; Gietel-Basten, S.; Koh, K. The food environments of fruit and vegetable consumption in East and Southeast Asia: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, L.; Rahman, S.; Sriboonchitta, S. Agricultural productivity growth and its determinants in south and southeast asian countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Avula, R.Y.; Pecota, K.V.; Yencho, G.C. Sweetpotato production, processing, and nutritional quality. Handbook of vegetables and vegetable processing; 2018; pp. 811-838.

- Alam, M.K.A. comprehensive review of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L. Lam): Revisiting the associated health benefits. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, D.; de Almeida Moreira, B. R.; Júnior, M. R. B.; Maeda, M.; da Silva, R. P. Sustainable management of sweet potatoes: A review on practices, strategies, and opportunities in nutrition-sensitive agriculture, energy security, and quality of life. Agricultural Systems 2023, 210, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Jaarsveld, P.J.; Faber, M.; Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Nestel, P.; Lombard, C.J.; Benadé, A.J.S. β-Carotene–rich orange-fleshed sweet potato improves the vitamin A status of primary school children assessed with the modified-relative-dose-response test 1–3. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Mounika, V.; Gowd, T.Y. M.; Lakshminarayana, D.; Krishna, G.V.; Reddy, I.V.; Soumya, B.K. Reddy, P.M. Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam): a comprehensive review of its botany, nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, health benefits, and future prospects. European Food Research and Technology 2025, 1-15.

- Motsa, N.M.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) as a drought tolerant and food security crop. South African J. Sci. 2015, 111, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfe, 1992Woolfe, J. A. Sweet potato: an untapped food resource. Cambridge University Press. 1992.

- Ahn, Y.S.; Jeong, B.C.; Oh, Y.B. Production and utilization of sweet potato in Korea. In “Proceedings of International workshop on sweet potato production system toward the 21st century”. National Agricultural Experiment Station in Kyushu, Japan, 1998, pp. 137-147.

- Amagloh, F.C.; Yada, B.; Tumuhimbise, G.A.; Amagloh, F.K.; Kaaya, A.N. The potential of sweet potato as a functional food in sub-Saharan Africa and its implications for health: a review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2971. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.F.M.S.; Kitaya, Y.; Hirai, H.; Yanase, M.; Mori, G.; Kiyota, M. Growth characteristics and yield of sweet potato grown by a modified hydroponic cultivation method under field conditions in a wet lowland. Environ. Control in Biol. 1997, 35, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro, K.; Yoshimoto, M. Content of the eye-protective nutrient lutein in sweet potato leaves: Concise Papers of the Second International Symposium on sweet potato and Cassava. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2005, pp. 213–214.

- Yoshimoto, M. Sweet potato as a multifunctional food. Proceedings of International work shop on sweet potato production system toward the 21st century, Kyushu National Agricultural Experiment Station, Japan, 1998, pp. 273-283.

- Drew, M.C. Oxygen Deficiency and Root Metabolism: Injury and Acclimation under Hypoxia and Anoxia Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 1997, 48, 223-250.

- Bunnell, B. T.; McCarty, L. B.; Hill, H. S. Soil gas, temperature, matric potential, and creeping bentgrass growth response to subsurface air movement on a sand-based golf green. HortScience 2004, 39, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, Y.; Yabuki, K.; Kiyota, M. Studies on the control of gaseous environment in the rhizosphere. (2) Effect of carbon dioxide in the rhizosphere on the growth of cucumber. J. Agr. Met. 1984, 40, 119–124, (in Japanese with English abstract, tables, and figures). [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Kitaya, Y.; Shibuya, T.; Kiyota, M. Effects of soil gas composition on transpiration and leaf conductance Journal of Agricultural Meteorology 2005, 60, 845-848.

- Islam, A.F.M.S.; Kitaya, Y.; Hirai, H.; Yanase, M.; Mori, G.; Kiyota, M. Growth characteristics and yield of carrots grown in a soil ridge with a porous tube for soil aeration in a wet lowland. Scientia horticulturae 1998, 77, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A. F. M. S.; Kitaya, Y.; Hirai, H.; Yanase, M.; Mori, G.; Kiyota, M. Growth characteristics and yield of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) grown by a modified hydroponic cultivation method under field conditions in a wet lowland Environment Control in Biology 1997, 35, 123-129.

- Siqynbatu; Kitaya, Y.; Hirai, H.; Endo, R.; Shibuya, T. Effects of water contents and CO2 concentrations in soil on growth of sweet potato. Field Crops Research 2013, 152, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, T. J.; Nielsen, K. L.; Eissenstat, D. M.; Lynch, J. P. Soil CO2 concentration does not affect growth or root respiration in bean or citrus. Plant, Cell & Environment 1997, 20, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.F.M.S.; Kitaya, Y.; Hirai, H.; Yanase, M.; Mori, G.; Kiyota, M. Effects of placing rice straw, wheat straw, and rice husks in soil ridges on growth, morphological characteristics, and yield of sweet potato in wet lowlands. J. Agric. Meteorol. 1997, 53, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.F.M.S.; Kitaya, Y.; Hirai, H.; Yanase, M.; Mori, G.; Kiyota, M. Sweet potato cultivation with rice husk charcoal as a soil aerating material under wet lowland field conditions. Environ Control in Biol. 1998, 36, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Ozaki, K.; Yashiki, T. Studies on the Effects of Soil Physical Conditions on the Growth and Yield of Crop Plants: VII. Effects of soil air composition and soil bulk density and their interaction on the growth of sweet potato. Japanese Journal of Crop Science 1968, 37, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, B.T.; McCarty, L.B.; Hill, H.S. Soil gas, temperature, matric potential, and creeping bentgrass growth response to subsurface air movement on a sand-based golf green. HortScience 2004, 39, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Li, Y. Management of flooding effects on growth of vegetable and selected field crops. Philippine Journal of Crop Science 2003, 3, 610–616. [Google Scholar]

- Pardales, J.J.; Escalante, M.C. The effect of various water table depths on the growth and yield of sweet potato. Philippine Journal of Crop Science 1978, 3, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P. G.; Smittle, D. A.; Hall, M. R. Relationship of sweetpotato yield and quality to amount of irrigation. HortScience 1992, 27, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, Y.; Yabuki, K. Studies on the Control of Gaseous Environment in the rhizosphere. (1) Changes in CO2 concentration and gaseous diffusion coefficient in soils after illigation. J. Agr. Met. 1984, 40, 1–7, (in Japanese with English abstract, tables, and figures). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).