1. Introduction

Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors—especially against high-value but structurally complex targets such as kinases, GPCRs, and protein–protein interfaces—unfolded through a painstaking cycle of chemical synthesis, high-throughput screening, and iterative structure–activity relationship (SAR) analysis. This process, constrained by experimental throughput and human intuition, often took years to yield a single clinical candidate. The past decade, however, has witnessed a profound transformation: the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into drug discovery has enabled the

de novo, property-driven generation of drug-like molecules with unprecedented speed, scale, and chemical novelty [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Many deep learning approaches have been put forward employing various neural network architectures, molecular representations and analysis metrics for targeted compound design, and their applications [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This paradigm shift in the drug discovery field has not been monolithic but has evolved through a series of methodologically distinct yet conceptually linked phases, each building on the successes and correcting the shortcomings of the last and collectively steering the field from syntax-aware sequence modeling toward structure- and function-aware molecular design.

The first wave of this transformation emerged between 2017 and 2019, when several studies began treating molecules as textual sequences using the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) and applying natural language processing (NLP) techniques to chemical space. Deep neural network (DNN) models, most notably variational autoencoder (VAE) [

9] and generative adversarial networks (GAN) [

17] have been particularly fruitful in molecular design of novel chemical probes [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Among the earliest efforts was sequence data generation (SeqGAN) approach [

18], and Objective-Reinforced Generative Adversarial Networks (ORGAN) [

19] which coupled a recurrent neural network (RNN) generator with a discriminator trained not just to assess chemical validity but to maximize user-defined molecular properties—a pioneering step toward goal-directed generation. LatentGAN combined an autoencoder and a generative adversarial neural network for de novo molecular design [

20]. DruGAN approach combined GAN and VAE by training an adversarial autoencoder to efficiently sample molecules from the latent space [

23]. Soon after, MolGAN [

29] adapted GANs to molecular design, generating adjacent and feature matrices to represent molecular graphs directly. CycleGAN provided unpaired Image-to-Image translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks [

30]. MolCycleGAN, which extended the CycleGAN framework, can learn transformation rules from the sets of compounds with desired and undesired values of the considered property [

31]. The methodological progress in GAN applications to molecular discovery has been catalyzed by the development of several comprehensive benchmarking sets and cheminformatics infrastructure [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Despite its conceptual elegance, MolGAN and related GAN approaches suffered from severe mode collapse and produced valid molecules less than 30% of the time, highlighting the fragility of adversarial training in discrete spaces. A more robust alternative arrived with ChemVAE [

9], a variational autoencoder that encoded SMILES strings into a smooth, continuous 196-dimensional latent space while simultaneously predicting key drug-likeness metrics—quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED) [

37], synthetic accessibility score (SAS) [

38] , and logP [

39].

The field then pivoted between 2019 and 2021 toward active, reward-guided strategies that could steer generation with greater precision. The most influential of these was REINVENT [

20,

40,

41] a reinforcement learning (RL) framework that used policy gradients to fine-tune an RNN generator toward a customizable reward function. This reward could combine multiple objectives—such as predicted binding affinity, QED, and Tanimoto similarity to a reference scaffold—effectively turning the generative model into a programmable design engine. REINVENT quickly became the industry standard for scaffold hopping and lead optimization [

40,

41]. GENTRL approach compresses the space of small molecule structures onto a distribution that parameterizes the latent space in a high-dimensional lattice following by exploration and optimization of the latent space by reinforcement learning to discover novel kinase inhibitors [

42].

Concurrently, transformer architectures began to reshape the landscape of chemical AI. Attention-based generative models for de novo molecular design offered new architectures that enabled a more accurate sampling from the latent space and exploration of novel chemistry space not present in the training data [

43], thus optimizing the tradeoffs between model exploration and structure of the latent memory. Efficient multi-objective molecular design approaches combine

in silico prediction of molecular properties defined desirability ranges and substructure constraints with particle swarm optimization for optimal navigation in a continuous latent space [

44,

45,

46]. A highly efficient and generic query-based molecule optimization framework QMO facilitates molecule optimization by decoupling molecule representation learning and guided search method based on zeroth-order optimization in the molecular property landscape [

47]. The performances of DL-based, VAE, GAN and RNN models were evaluated in goal-directed (rediscovery, optimization and scaffold hopping of active compounds) and target-specific (generation of novel compounds for a given target) tasks [

48]. Simultaneously, SMILES-BERT [

49] and Chemformer [

50,

51] applied transformer architectures to molecular sequences, leveraging self-supervised pretraining on billions of compounds to improve generation quality and transfer learning. These approaches offered greater controllability and higher validity, but remained constrained by the sequential nature of SMILES, which struggles to represent cyclic and stereochemical complexity. Meanwhile, MolDQN bypassed SMILES by applying deep Q-learning to discrete molecular graph actions, optimizing molecular properties through a Markov decision process [

52]. Despite these advances, this phase remained two-dimensional: rewards were often computed using surrogate predictors—such as Random Forests trained on RDKit descriptors rather than direct protein–ligand interactions, yielding molecules that were chemically plausible but often pharmacologically inert.

Some generative models aiming at three-dimensional (3D) molecule generation have also been proposed, gaining attention for their unique advantages and potential to explicitly design drug-like molecules in a target-conditioning manner [

53]. A novel molecular deep generative model adopts a recurrent neural network architecture coupled with a ligand-protein interaction fingerprint as constraints [

54]. DeepLigBuilder, a deep learning-based method for

de novo drug design combined Ligand Neural Network (L-Net) graph generative model for design of chemically and conformationally valid 3D molecules with Monte Carlo tree search to optimize structure-based

de novo drug design parameters such as high predicted affinity, and similar binding features to those of known inhibitors [

55]. A comprehensive review of 3D molecular generative models reported current techniques for the molecular structure generation and categorized them into three types, depending on featurization of 3D molecular structures: cubic grid-based, Euclidean distance matrix(EDM)-based, and Cartesian coordinate-based, where each type of featurization requires distinct generative architectures and optimization strategies [

56].

Th advent of graph representation learning, a class of machine learning methods that natively operate on graph-structured data, has enabled neural networks to learn directly from molecular topology. Over the past seven years, graph neural networks (GNNs) have redefined the very architecture of

de novo molecular design, virtual screening, and protein–ligand interaction modeling. The adoption of GNNs in drug discovery began with their ability to natively represent molecules as graphs and learn structure–property relationships directly from topology. Gilmer et al. [

57] laid out the conceptual foundation of GNNs with the introduction of Neural Message Passing (MPNN), a unifying framework that cast molecular property prediction as an iterative process of information exchange between atoms and bonds. This insight catalyzed a wave of chemistry-specific GNN architectures. Kearnes et al. demonstrated that Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) could predict ADMET properties with high accuracy by aggregating neighborhood features in molecular graphs [

58]. Soon after, Veličković et al. introduced Graph Attention Networks (GATs), which learned to weight the importance of neighboring atoms dynamically, capturing subtle electronic effects critical for reactivity and binding [

59]. A pivotal advance came with Directed Message Passing Neural Networks (D-MPNN) approach which explicitly modeled bond directionality and chirality—features essential for drug-likeness and target specificity [

60] D-MPNN achieved state-of-the-art performance across quantum chemical (QM9) and bioactivity (MUV, Tox21) benchmarks and became the core of the open-source Chemprop framework, now widely adopted in both academia and industry for interpretable molecular property prediction [

60].JT-VAE approach widely adopted by 2021, decomposed molecules into hierarchical junction trees of rings and chains, enabling near-perfect validity (>99%) and precise control over scaffold modification [

61]. Junction tree variational autoencoder (JT-VAE) generates molecular graphs in two phases, by first generating a tree-structured scaffold over chemical substructures and then combining them into a molecule with a graph message passing network [

61]. Similarly, GraphAF used autoregressive normalizing flows to build molecular graphs atom-by-atom with high fidelity, ensuring that valency and chirality were respected [

62]. More recently, GFlowNets [

63,

64] introduced a probabilistic framework for sampling molecules proportional to a reward function (e.g., binding affinity), mitigating the mode collapse and low diversity that plagued earlier generative approaches.

As the field matured, the limitations of static, 2D graph representations became evident—particularly for tasks requiring 3D conformational awareness, such as protein–ligand docking and allosteric modulation. This spurred the rise of geometric deep learning, where models respect the rotational and translational symmetries of physical space. SchNet, introduced by Schütt et al. [

65,

66] pioneered the use of continuous-filter convolutions operating directly on atomic coordinates, enabling accurate prediction of molecular energies and interatomic forces with quantum-mechanical fidelity. This was significantly refined in DimeNet and DimeNet++ [

67,

68] which incorporated directional message passing using interatomic angles, dramatically improving the modeling of torsional strain, steric clashes, and binding pocket complementarity. The culmination of this trend arrived with SE(3)-equivariant GNNs, exemplified by EquiBind which predicted protein–ligand binding poses in seconds—without traditional docking—by learning geometric constraints directly from structural data [

69]. EquiBind achieved near-experimental accuracy on the PDBBind benchmark, effectively replacing physics-based scoring in early-stage screening [

69].

Critically, graph representation learning also enabled direct modeling of protein–ligand complexes as heterogeneous graphs, where protein residues and ligand atoms form distinct node types connected by cross-edges. TANKBind approach segments the whole protein into functional blocks and predict their interactions with the ligand, creating a protein-ligand interaction energy landscape using a novel trigonometry-aware architecture. In the second stage, TANKBind prioritizes the crystal structures by constrastively ensuring a weaker binding affinity for non-native interactions [

70]. Self-supervised, pretrainable geometric GNNs can learn rich representations of molecules and proteins from unlabeled structural data and represent a new class of models designed for molecular property prediction that leverage 3D molecular structure information during pre-training to improve performance on downstream tasks [

71,

72,

73]. Graph Multi-View Pre-training (GraphMVP) framework addresses limited 3D molecular data by using self-supervised learning with contrastive learning to enforce consistency between 2D and 3D molecular representations, enhancing performance in property prediction tasks [

71].

The current frontier integrates generative modeling and massive scale pretraining into end-to-end systems capable of co-designing proteins and ligands from first principles. Diffusion models have emerged as one of the dominant generative frameworks. GeoDiff is the first SE(3)-equivariant diffusion model that operates directly on atomic coordinates and learns to reverse a diffusion process that gradually adds noise to a molecule’s 3D structure [

74]. This approach enabled structure-aware ligand generation for docking and binding prediction and laid the foundation for protein-conditioned diffusion models. By expanding this work, Tang and his group introduced a pretrainable, SE(3)-equivariant geometric GNN specifically designed for antibody affinity maturation [

75]. This work bridged geometric deep learning and self-supervised pretraining with high-throughput experimental biology to create a predictive, generative, and actionable platform for antibody engineering. These studies underscored a broader trend: the shift from sequence-based to structure-based AI in therapeutic discovery, with geometric GNNs at the forefront. TorsionDiff [

76] operates in torsion angle space to produce realistic side-chain rotamers. DiffDock predicts binding poses with near-experimental accuracy, effectively replacing classical docking pipelines [

77]. DiffDock-L, a latest version of DiffDock provides a significant improvement in performance and generalization capacity [

78]. DiffLinker is a new Equivariant 3D-conditional Diffusion Model for Molecular Linker Design that places missing atoms in between and designs a molecule incorporating all the initial fragments [

79].

When conditioned on protein structure, diffusion-based models achieve remarkable biological specificity. RFdiffusion approach developed by the Baker Lab uses a protein backbone diffusion model [

80] and when paired with the sequence design tool ProteinMPNN [

81] enables

de novo creation of protein binders, allosteric pockets, and small-molecule scaffolds. Complementing these are foundation models trained on multimodal biological data: ESM3 developed by EvolutionaryScale, integrates sequences, 3D structures, and functional annotations into a single architecture capable of zero-shot ligand generation via in-context learning [

82]. Chroma, a generative model for proteins and protein complexes, can directly sample novel protein structures and sequences, and that can be conditioned to steer the generative process towards desired properties and functions [

83]. This evolution has been accelerated by open-source ecosystems and standardized benchmarks. PyTorch Geometric (PyG) [

84] and Deep Graph Library (DGL) [

85] provide modular, scalable implementations of GNN layers. The Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) [

86] offers a unified benchmark with 66 therapeutic tasks—including kinase inhibitor design, antibody escape, and molecular generation—enabling fair comparison and reproducibility across the field.

Overall, graph representation learning has transformed computational drug design from a descriptor-driven science into topology- and geometry-aware engineering. By respecting the intrinsic structure of molecules and their biological targets, GNNs have not only improved predictive accuracy but have restored chemical realism to generative AI—paving the way for the next generation of rational, mechanism-informed, and human-aligned drug discovery.

This progression reflects a profound paradigm shift: ligands are no longer optimized against scalar activity predictors but directly against 3D protein structures; scoring is embedded within the generative process itself, eliminating reliance on external reward functions; and multi-objective trade-offs—between potency, selectivity, and developability—are handled implicitly through conditional diffusion or multi-task pretraining. Yet significant challenges remain. Data scarcity for mutant or allosteric targets demands robust few-shot and zero-shot capabilities. And as models grow more end-to-end, their black-box nature threatens interpretability—a gap that hybrid approaches, combining the predictive power of graph neural networks with chemically grounded, interpretable features metric, may help bridge. In the development of kinase inhibitory therapeutics, generating novel selective probes to interrogate specific protein kinases is a major challenge and machine learning-enabled targeted transformations and chemical morphing between kinase inhibitors from different families can provide a valuable resource for new indications of existing kinase molecules.

The current study is situated at the inflection point—between the promise of end-to-end deep generative models and the enduring need for chemical interpretability. While modern AI tools offer unprecedented generative power, they often operate as black boxes, making it difficult to diagnose failure modes, ensure pharmacophoric fidelity, or guide iterative refinement. In response, we present a modular, interpretable machine learning platform for the de novo design of SRC kinase inhibitors that strategically combines the representational capacity of ChemVAE, the chemical grounding of a feature-based kinase-specific scoring function, the sample efficiency of Bayesian optimization, and the scaffold-aware exploration of local neighborhood sampling-based latent space engineering.

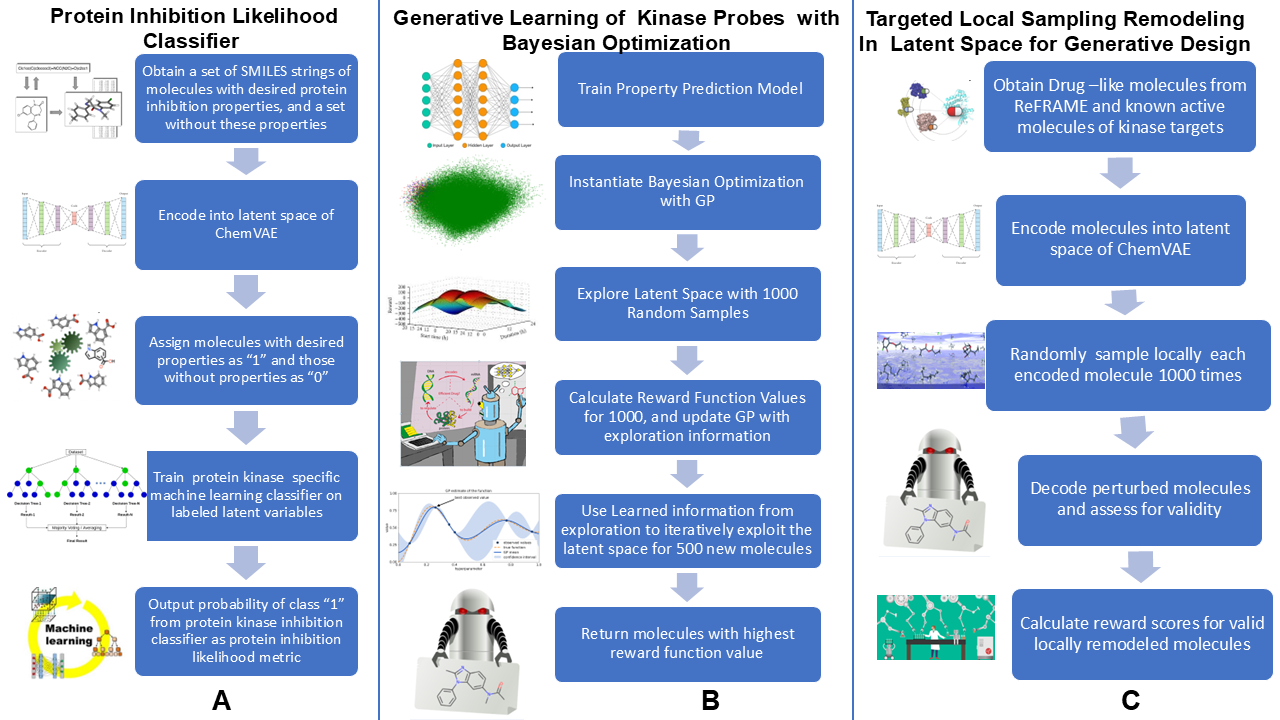

Our generative pipeline employs a hybrid AI framework that integrates deep variational autoencoding, interpretable machine learning–based scoring, and probabilistic optimization to enable targeted exploration of kinase inhibitor chemical space. The pipeline explicitly decomposes the design process into several interconnected stages : (a) deep generative backbone for latent space representation, (b) ML scorer for target-specific guidance, (c) probabilistic optimization engine (Bayesian Optimization) for search, (d) clustering-and-local neighborhood sampling layer for scaffold transformation. This work represents a significant conceptual and methodological extension of our earlier study [

87]. While that study introduced the ChemVAE framework and demonstrated initial scaffold transformation via latent space local neighborhood sampling, the present study delivers a more comprehensive, multi-strategy generative pipeline with several critical advances. Most notably, we now expand the data sets of random molecules and kinase inhibitors, introduce and rigorously benchmark Bayesian Optimization as a complementary global search strategy, revealing its strengths (efficient drug-likeness tuning) and fundamental limitations (systematic failure to recover multi-ring pharmacophores)—a diagnostic insight absent in the prior work. Beyond methodology, the current study provides structural validation through computational docking, confirming that remodeled molecules not only resemble but functionally mimic clinical SRC inhibitors in binding mode and affinity. Furthermore, we offer a mechanistic interpretation of latent space organization, identifying SRC as a structural “hub” and LCK as a uniquely “plastic” scaffold for transformation—findings grounded in statistical analysis of latent distributions across ten kinase families. Critically, we place our results in the context of modern generative AI, diagnosing the “representation gap” of SMILES-based models and articulating a clear path toward hybrid systems that integrate geometric GNNs with interpretable, chemistry-first design.

3. Results and Discussion

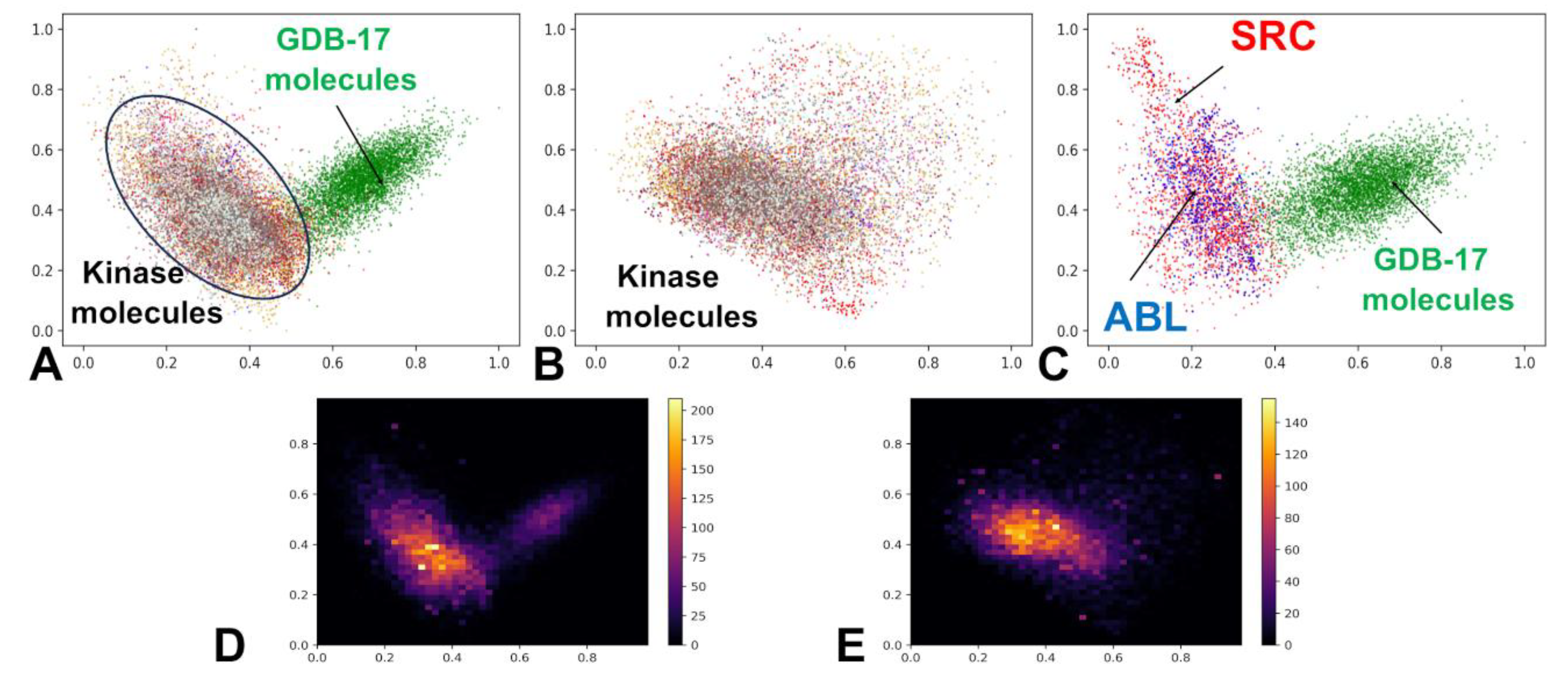

3.1. The Kinase Inhibitor Dataset and Its Embedding Reveals Organized Kinome Manifold in Latent Space

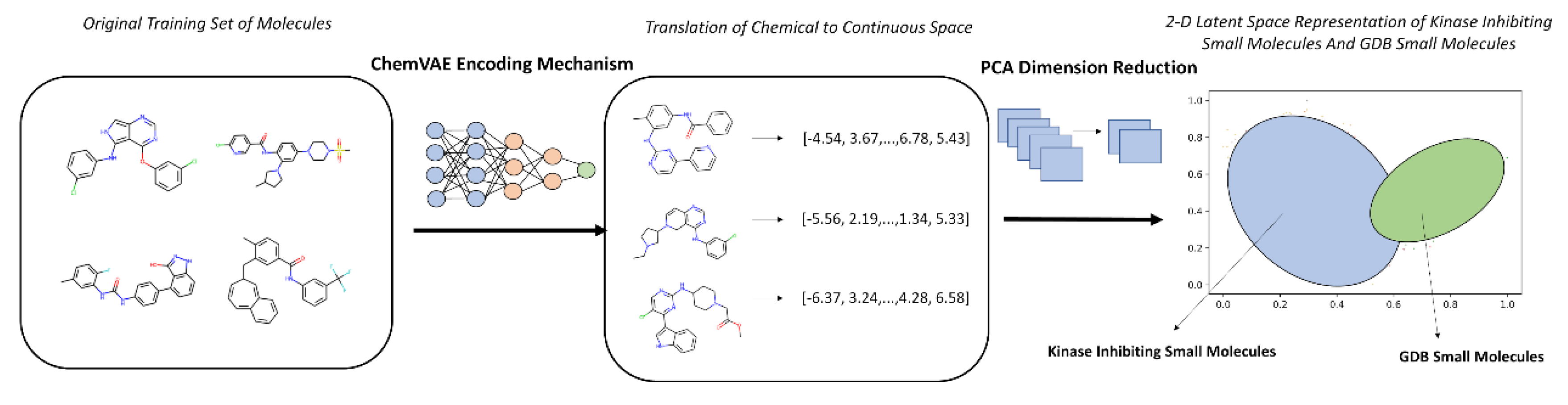

This curated hybrid dataset comprising of ~ 220,000 diverse molecules forming background set and ~60,000 available high-confidence PKIs from 37 distinct kinase families across the human kinome served as the training corpus for all machine learning components of our pipeline. Central to our approach was the ChemVAE architecture trained on SMILES strings that learns a continuous, low-dimensional latent representation of molecular structure. ChemVAE encodes each molecule into a fixed-length vector (here, 196-dimensional) by compressing its SMILES sequence through a bottleneck layer, while simultaneously optimizing for accurate reconstruction and property prediction (e.g., QED, logP, synthetic accessibility). This process effectively translates discrete chemical syntax into a differentiable geometric space, where semantic similarity (e.g., shared scaffolds or functional groups) is reflected in spatial proximity (

Figure 2).

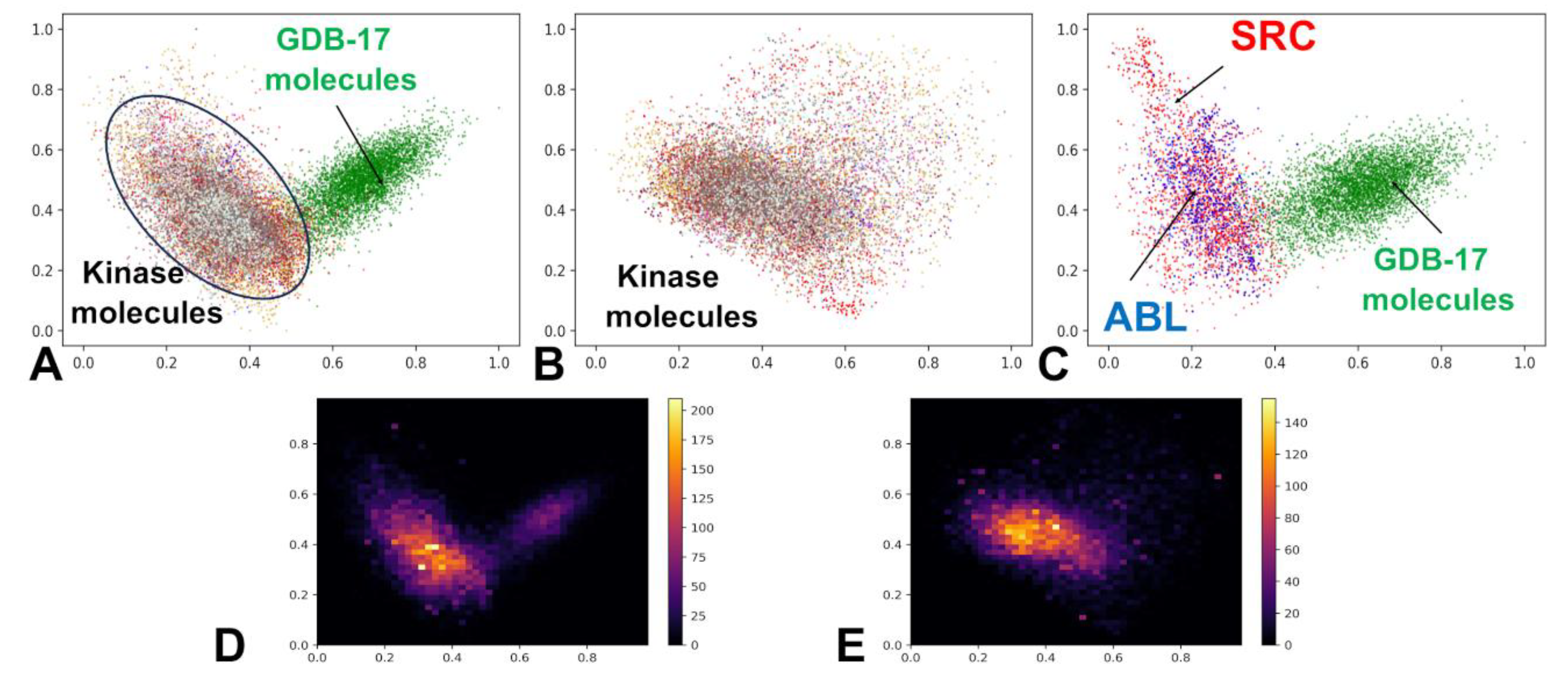

To interrogate the organization of this latent space, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) on the encoded vectors and visualized the results in two dimensions (

Figure 3). Embedding our large-scale kinase inhibitor dataset into the ChemVAE latent space revealed a striking and functionally meaningful organization: rather than scattering randomly, 60,000 kinase inhibitors spanning 37 families across the human kinome—collapsed into a dense, low-volume manifold, sharply segregated from the diffuse cloud of 220,000 generic molecules (

Figure 3 A,B). The PCA projection revealed that despite their pharmacological diversity, kinase inhibitors collapsed into a dense, spatially contiguous cluster, sharply demarcated from the diffuse, cloud-like distribution of GDB molecules (

Figure 3A). This separation was not an artifact of labeling or sampling; it emerged naturally from the model’s unsupervised training on SMILES syntax, suggesting that molecular sequence intrinsically encodes functional semantics. This separation persisted even when examining kinase inhibitors in isolation, where sub-clustering by family was evident but incomplete, reflecting shared ATP-binding motifs and overlapping chemotypes (

Figure 3B).

Within this kinase-rich region, a hierarchical structure became apparent. At the global level, all ATP-competitive inhibitors clustered together, reflecting the conserved architecture of the kinase catalytic cleft. Yet at a finer scale, family-specific subclusters emerged, highlighted for ABL and SRC kinase inhibitors (

Figure 3C) . The SRC family occupied the broadest region of latent space acting as a structural “hub” that overlapped significantly with LCK, ABL1, and EGFR. This proximity suggested that ABL, LCK and EGFR-derived molecules may be amenable to transformation into SRC-like chemotypes—a finding that would prove pivotal in our generative experiments. Visual inspection of the PCA-projected latent space revealed that most kinase inhibitors—regardless of target family—occupied a shared, high-density region that significantly overlapped with the clusters of SRC and ABL1 inhibitors (

Figure 3B,C). This spatial co-localization suggests that, despite differences in selectivity and clinical indication, these molecules share a core set of chemical–functional features essential for ATP-competitive binding, such as planar aromatic systems, hydrogen bond acceptors at the hinge region, and moderate molecular weight.

The emergence of highly skewed density peaks—with yellow indicating high concentration and purple low concentration in the kernel density estimates (

Figure 3D,E) demonstrated that kinase inhibitors occupy a statistically definable, low-volume manifold within the broader molecular landscape. This structured manifold provided more than a visualization—it offered a functional map for navigation. High-density zones (

Figure 3D,E) corresponded to chemically accessible regions, while sparse areas (purple) represented high-risk, low-validity territory. These high-density zones are not merely statistical artifacts; they represent chemically stable attractors in the latent space, where small local neighborhood samplings are more likely to decode into valid, synthesizable molecules.

This topological organization provided the foundational rationale for a classification-based generative strategy: if kinase inhibitors form a separable region, a model trained to recognize that region could guide molecular generation toward it. This insight directly informed our subsequent generative strategies—both Bayesian optimization and cluster-guided local neighborhood sampling—which were explicitly designed to operate within or near these high-fidelity regions.

To quantify this observation, we computed key statistical descriptors for each kinase family in the full 196-dimensional latent space, including the range (min–max), centroid (mean vector), and standard deviation across all dimensions (

Table 1). The results confirm that all kinase families span a remarkably similar domain in latent space, with minimum values ranging from –6.19 to –5.00 and maximum values from 5.97 to 7.06. This overlap reinforces the hypothesis that kinase inhibitors—by virtue of their shared target architecture—occupy a common, functionally constrained subspace within the broader chemical landscape.

Most notably, SRC inhibitors exhibited the largest spread in latent space, with the highest maximum standard deviation (1.632) and the broadest overall range (–5.89 to 6.20). This indicates that the SRC family encompasses the greatest structural diversity among the kinase classes studied—spanning a wider array of scaffolds, substitution patterns, and molecular topologies. In contrast, families like MAPK10 and MAPK14 showed more compact distributions (max SD: 1.295–1.298), suggesting greater structural homogeneity. This exceptional breadth has profound implications for generative design. The fact that SRC inhibitors dominate the latent region occupied by all kinase families implies that the chemical grammar of SRC inhibition is representative of kinase binding more broadly. Consequently, local neighborhood samplings applied to molecules from other kinase families—especially those with narrower distributions like FLT3 or MAPK10—may naturally evolve toward SRC-like chemotypes when steered toward high-density regions of the manifold. This positions SRC not just as a therapeutic target, but as a structural “hub” in kinase inhibitor space, making it an ideal focus for scaffold-hopping and family-to-family transformation strategies.

These findings collectively demonstrate that the latent space not only captures functional similarity across kinase families but also encodes scaffold diversity in a quantifiable manner. The SRC family’s expansive footprint suggests it serves as a structural reservoir—a rich source of motifs that can be leveraged to transform inhibitors from other kinase classes into novel SRC-targeted candidates through guided latent space local neighborhood sampling. This finding motivated a dual-strategy generative campaign: one that explores the global manifold for novel, drug-like candidates (Bayesian Optimization), and another that manipulates local neighborhoods to transform known scaffolds into new chemotypes (local neighborhood sampling-based engineering).

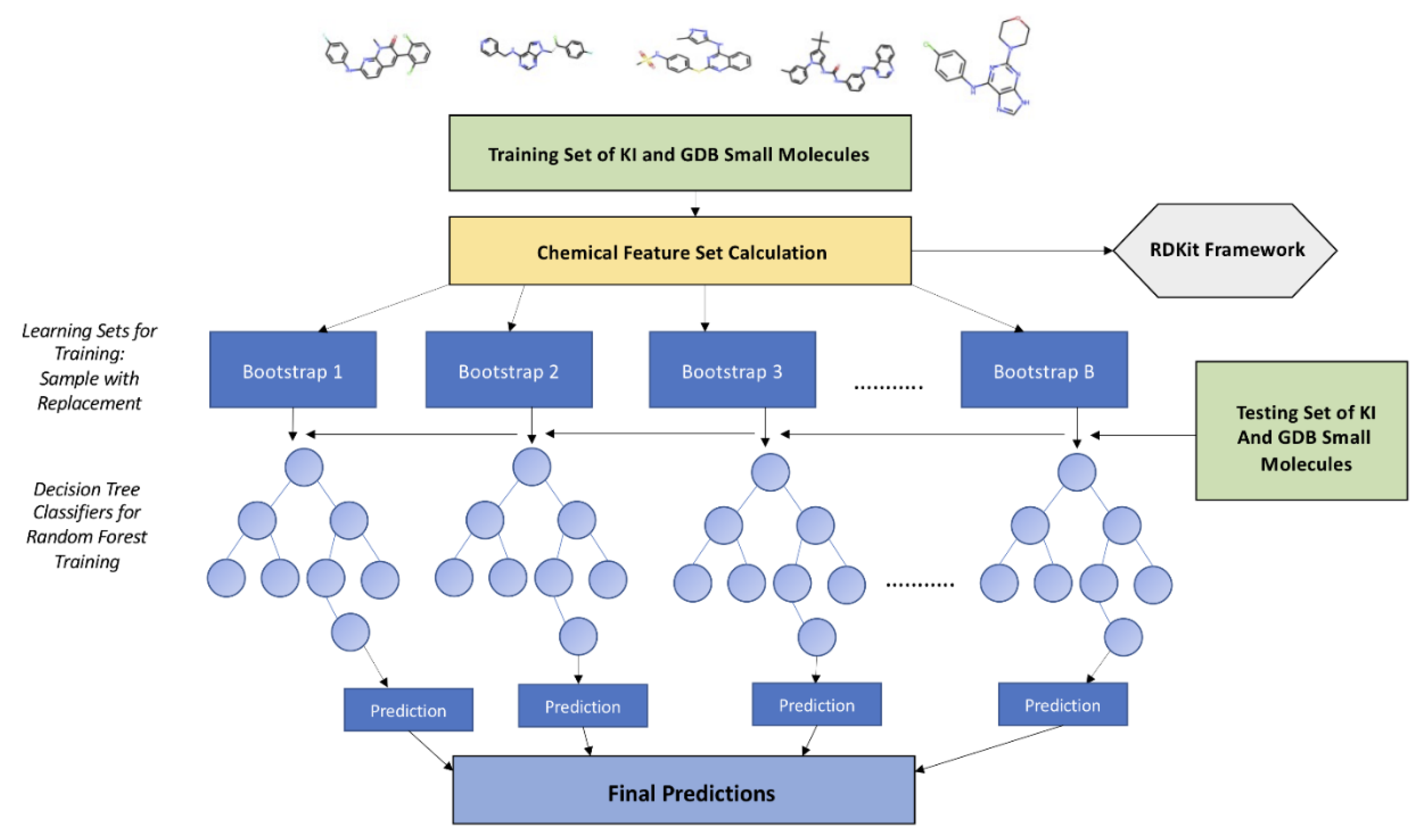

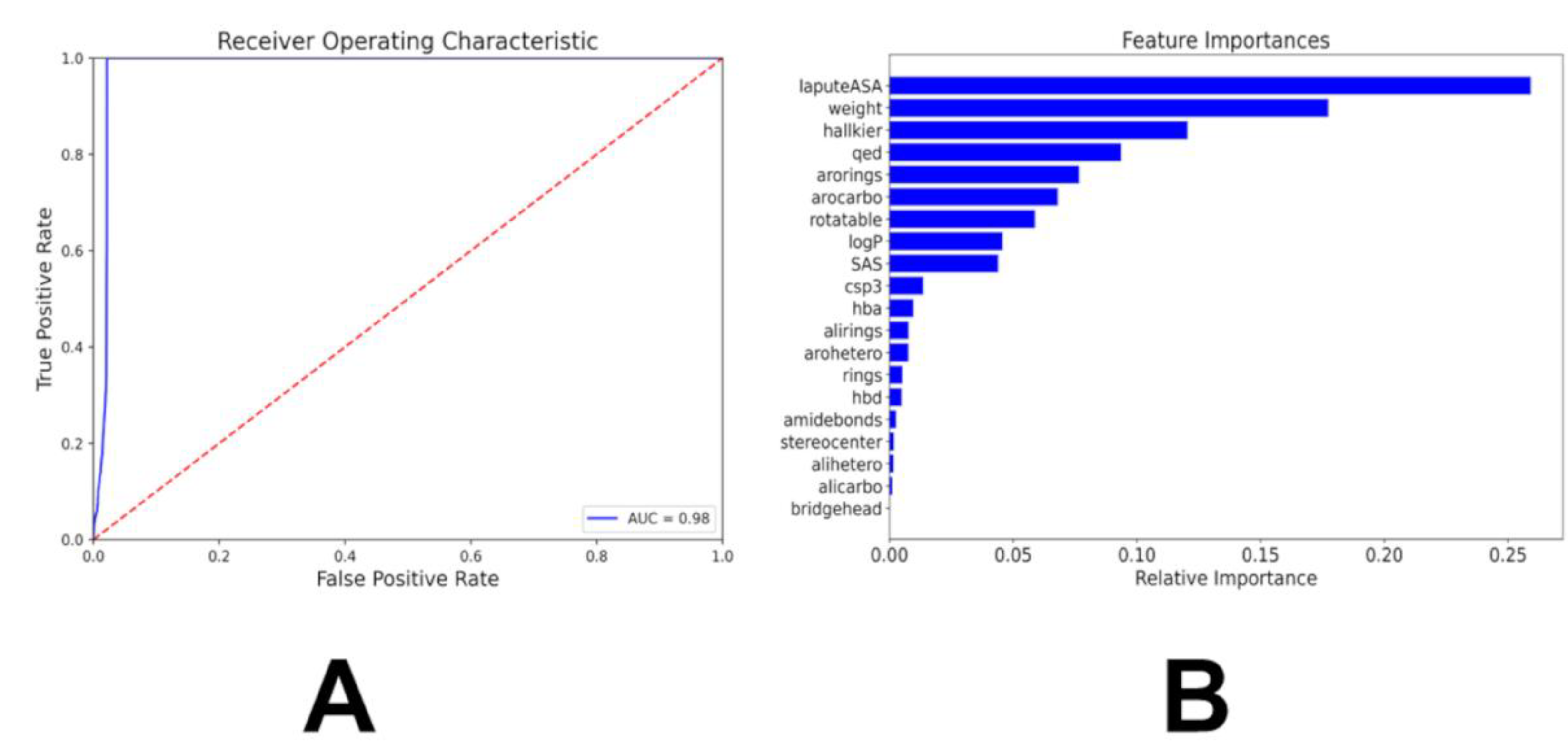

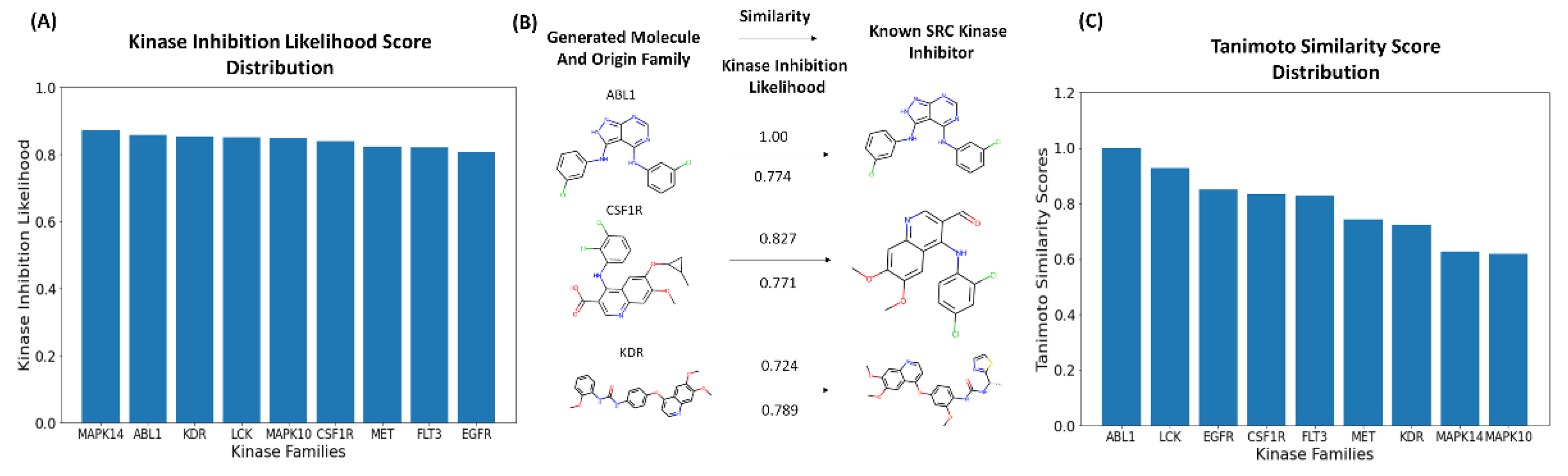

3.2. Multiclass and Binary Kinase Inhibition Likelihood Classifiers

A central challenge in generative drug design is the absence of a reliable, biologically meaningful objective function that can guide molecular exploration toward functional—not just chemical—relevance. To address this, we developed the Kinase Inhibition Likelihood (KIL)a probabilistic scoring function that estimates the likelihood a given molecule belongs to the chemical space of experimentally validated SRC kinase inhibitors. KIL is not a generic activity predictor; it is a target-specific, interpretable metric designed to enable rational scaffold transformation across kinase families. We trained a Random Forest classifier using 20 RDKit-derived chemical descriptors, including Labute accessible surface area (LabuteASA), molecular weight, HallKier alpha, aromatic ring count, QED, logP, SAS, and hydrogen bond acceptor count. The positive class comprised 1,502 SRC inhibitors from ZINC, while the negative class included ~ 23,530 molecules including ~ 9,000 inhibitors from other kinase families (ABL1, and ~14,530 subsampled GDB molecules. We opted to subsample GDB set to maintain model sensitivity to the minority class (SRC) since including all GDB molecules would create an extreme negative majority (~99% background), making the model trivially predict “0” and ignore the SRC class. The adopted split can also reflect a realistic chemical space where drug-like matter is abundant but not overwhelmingly dominant in screening libraries. This binary design was deliberate: rather than attempting to distinguish among all kinase families—a task confounded by structural homology in the ATP-binding site—we focused exclusively on SRC vs. everything else, sharpening the model’s discriminatory power for our generative goal.

The binary model achieved SRC precision = 0.71, recall = 0.86, F1 = 0.78, with a macro F1-score of 0.88 (

Table 2). The macro average precision score of 0.85 reinforces the overall satisfactory performance of the model because it means that the model was accurate in predicting if a given molecule was an SRC Kinase Inhibitor 85% of the time. For classification models, an accuracy score of 0.85 is extremely strong. In addition, the macro average recall score of 0.92 validates the excellent performance of the model that the precision value helped establish. All these metrics indicate good classification performance of the model. This suggested that target-focused design may benefit from a simplified objective that avoids diluting signal across highly similar classes.

We also evaluated a multiclass chemical feature–based model, assigning each of the top ten kinase families a unique label. Despite its conceptual appeal, this approach underperformed for SRC: precision = 0.57, recall = 0.56, F1 = 0.56 (

Table 3). This reflects the inherent ambiguity in kinase inhibitor space—families like LCK and SRC share overlapping scaffolds (e.g., pyrrolopyrimidines), making fine-grained classification more error-prone. In the macro averages, the precision score was 0.63, the recall score was 0.59, and the F1-Score was 0.61. In the weighted average, the precision was 0.63, the recall score was 0.63, and the F1-Score was 0.63. The model showed the greatest metric values when predicting kinase inhibitors from the MAPK14 and MET kinase families. However, the other kinase families performed modestly in precision values, recall values or the F1-scores. In addition, the macro average F1-score of the multiclass model is 0.61 compared to the 0.88 F1-score of the binary model. Hence, the multiclass random forest model performs less favorably at distinguishing SRC inhibitors as compared to the chemical feature-based binary classifier.

The chemical feature binary KIL classifier ca achieves the overall accuracy of distinguishing kinase inhibiting molecules around 98% (

Figure 4). The AUC of the model was 0.98, indicating that the model can distinguish both classes with 98% certainty (

Figure 4A). We performed feature importance analysis (

Figure 4B). The top 10 features that contribute the most relative importance to the model’s prediction are the labute accessible surface area (labuteASA), weight, HallKier Alpha, the number of aromatic rings, aromaticity, the QED score, number of rotatable bonds, the logP score, the SAS score, and the number of hydrogen bond acceptors (

Figure 3B). These features encode planar aromatic systems, hydrophobic surface area, and molecular rigidity—hallmarks of ATP-competitive binding. The inclusion of QED, logP, and SAS ensures that KIL implicitly penalizes molecules with poor developability, aligning predicted activity with pharmaceutical reality.

KIL is used not only in classification, but also as a diagnostic and guiding signal for generative design implemented in the present investigation. In both Bayesian Optimization (BO) and local neighborhood sampling-based latent space engineering approaches employed in our study, a reliable, differentiable (or at least efficiently evaluable) objective function is essential to direct search toward biologically relevant regions of chemical space. In the absence of such a function, generative models either produce random drug-like molecules or drift into chemically plausible but pharmacologically inert regions. For Bayesian Optimization, KIL served as the black-box objective that the Gaussian process surrogate model sought to maximize. BO does not require gradients, but it does require a low-variance, high-signal scoring function that correlates with the desired property—in this case, SRC inhibition potential. KIL fulfilled this role by providing a fast, interpretable, and chemically grounded estimate of target affinity, enabling BO to iteratively select latent points predicted to yield high-KIL molecules without resorting to expensive physics-based scoring (e.g., docking, or free energy calculations). For local neighborhood sampling-based generation, KIL played a diagnostic and filtering role. While local neighborhood samplings were guided by latent space geometry (cluster centroids), KIL was used post-hoc to assess whether the transformed molecules had successfully migrated into the SRC chemical manifold.

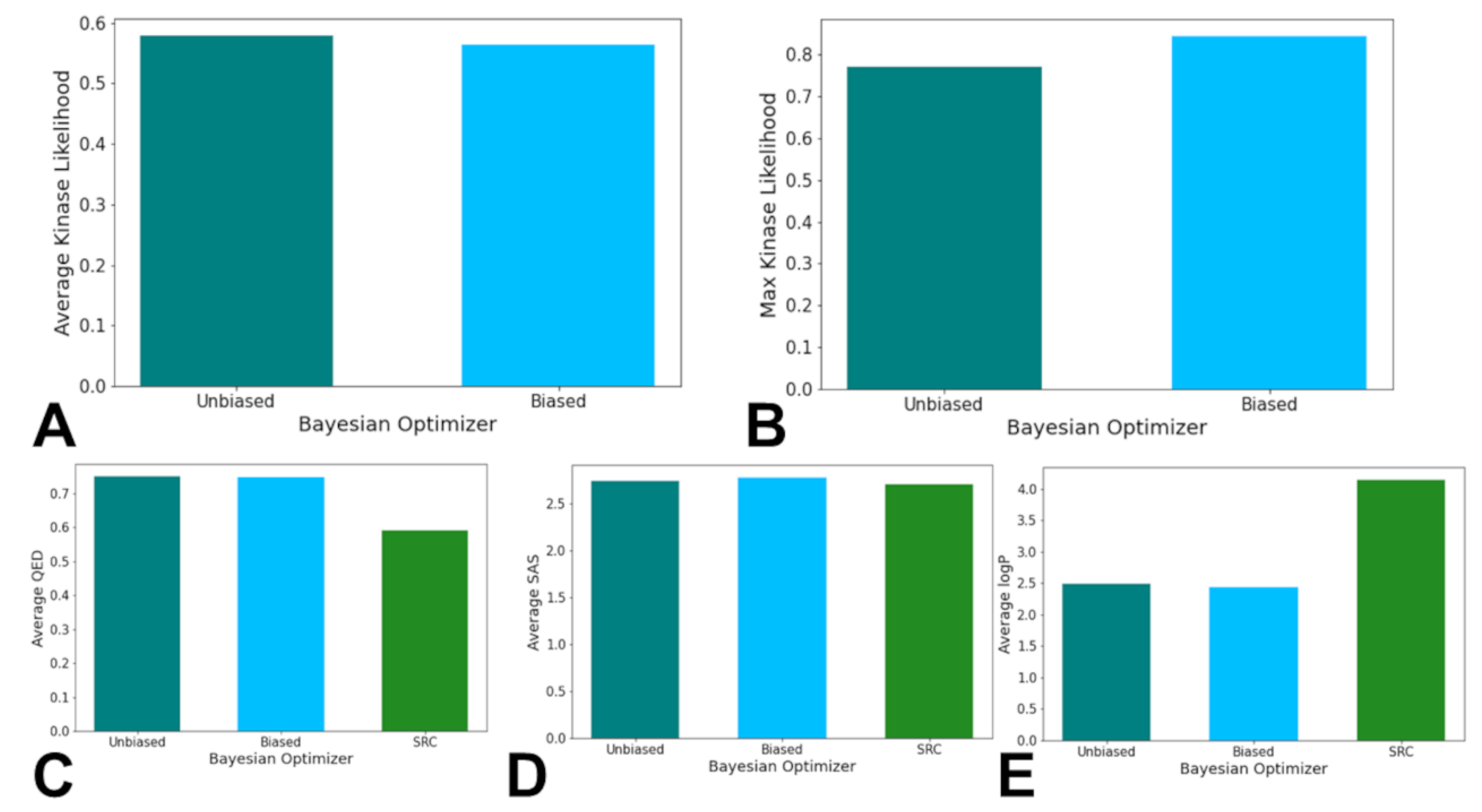

3.3. Bayesian Optimization Enables Efficient Exploration of SRC Kinase Inhibitor Chemical Space

To systematically navigate the ChemVAE latent space in search of novel SRC kinase inhibitors, we implemented a Bayesian Optimization (BO) framework guided by the KIL scoring function. BO is a sequential design strategy that constructs a probabilistic surrogate model—here, a Gaussian process—to approximate an unknown objective function and iteratively selects new evaluation points by maximizing an acquisition function that balances exploration (sampling uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining high-scoring regions). In molecular design, this approach minimizes the number of costly function evaluations required to identify high-performing candidates. We executed two parallel optimization runs: an Unbiased BO, initialized with 7,000 random latent points, and a Biased BO, first probed with 2,258 known SRC inhibitors to inject prior knowledge of the target manifold before random initialization. Both performed 1,500 acquisition steps. After decoding latent vectors to SMILES and filtering for validity using RDKit, the Biased BO yielded 492 valid molecules (83% validity), while the Unbiased BO produced 390 (89% validity).

Due to the random nature of the Bayesian Optimizer, a threshold of KIL score of 0.5 was used to as the baseline for a generated molecule to have a higher Kinase Inhibition Likelihood. Out of the valid molecules produced from each Optimizer, 153 molecules out of the original 492 molecules produced, or 31.10%, from the Biased Optimizer had a calculated KIL value greater than 0.5. The Unbiased Optimizer maintained 145 of its original 390 valid molecules produced, or 37.18%, with a calculated KIL value greater than 0.5. When analyzing the molecules with a calculated KIL score greater than the 0.5 threshold, the Unbiased Optimizer had a higher average calculated KIL of 0.5783 compared to an average of 0.5639 for the molecules generated by the Biased Bayesian Optimizer (

Figure 5A). The molecule with the highest calculated Kinase Inhibition Likelihood score was produced by the Biased Bayesian Optimizer with a score of 0.8425. The molecule with the highest calculated Kinase Inhibition Likelihood score produced by the Unbiased Optimizer had a score of 0.7693 (

Figure 5B). Hence, the Unbiased BO exhibited a higher average KIL among qualifiers (0.578 vs. 0.564), while the Biased BO produced the single highest-scoring molecule (KIL = 0.8425) (

Figure 5A,B). This duality—higher plateau versus higher peak—suggested that unbiased exploration promoted consistent performance across chemical space, whereas bias enabled access to deeper local optima near known actives.

To evaluate the similarity testing metrics, we investigated the performance of each of the Bayesian Optimizers based on average similarity scores of the generated molecules, as well as the maximum similarity score that each model produced. When analyzing all the molecules generated from each Bayesian Optimizer, the average Tanimoto similarity scores for the Unbiased and Biased Bayesian Optimizers were 0.4656 and 0.4446 respectively (Supporting Information,

Figure S1A). The maximum Tanimoto similarity scores for the Unbiased and Biased Bayesian Optimizers were 0.7115 and 0.7091 respectively (Supporting Information,

Figure S1B). Strikingly, no generated molecule surpassed the conventional high-similarity threshold of 0.75. The maximum similarity was 0.7115 (Unbiased) and 0.7091 (Biased), and the top KIL molecule (0.8425) exhibited only modest similarity (0.548) (Supporting Information,

Figure S1). This decoupling between scoring and structural mimicry revealed a core limitation: KIL, while statistically robust, optimizes global physicochemical proxies that correlate with—but do not guarantee—the local pharmacophoric patterns essential for SRC binding.

When determining the performance of the Bayesian Optimizers in relation to the chemical feature values of QED, logP, and SAS, the generated molecules from the optimizers had similar average SAS scores compared to the known SRC kinase inhibitors but had significant differences in the average QED and logP scores. The average QED scores for the Unbiased and Biased Bayesian Optimizers’ generated molecules were 0.7499 and 0.7486 respectively, in comparison to the known SRC kinase inhibitors average QED score of 0.5908 (

Figure 5C). The average logP scores for the Unbiased and Biased Bayesian Optimizers’ generated molecules were 2.488 and 2.439 respectively, in comparison to the known SRC kinase inhibitors average logP score of 4.137 (

Figure 5D). The average SAS scores for the Unbiased and Biased Bayesian Optimizers’ generated molecules were 2.742 and 2.772 respectively, in comparison to the known SRC kinase inhibitors average SAS score of 2.706 (

Figure 5E). The general similarity of the scores of the generated molecules in comparison to the known SRC kinase inhibitors suggest that the metrics are being tuned as a part of the Bayesian Optimizers’ hyperparameter tuning process. While there are differences between the generated molecules and the known SRC kinase inhibitors when analyzing the QED and logP scores, the scores imply that the molecules produced by the Bayesian Optimizers would be synthesizable and/or absorbable even with lower similarity metrics in other chemical features.

Contrary to expectations, biasing the optimizer with known SRC inhibitors conferred no meaningful advantage in similarity, KIL, or structural plausibility. While the Biased BO produced more valid molecules, its output exhibited markedly reduced scaffold diversity: the same two known SRC inhibitors repeatedly served as the nearest neighbors for the top generated molecules (Supporting Information,

Figure S2). This pattern—absent in the Unbiased BO results—suggests that initial probing trapped the optimizer in a narrow local optimum, causing it to over-exploit motifs from only 1–2 reference compounds. In contrast, the Unbiased BO generated structurally diverse candidates (Supporting Information,

Figure S3), indicating broader exploration of chemical space.

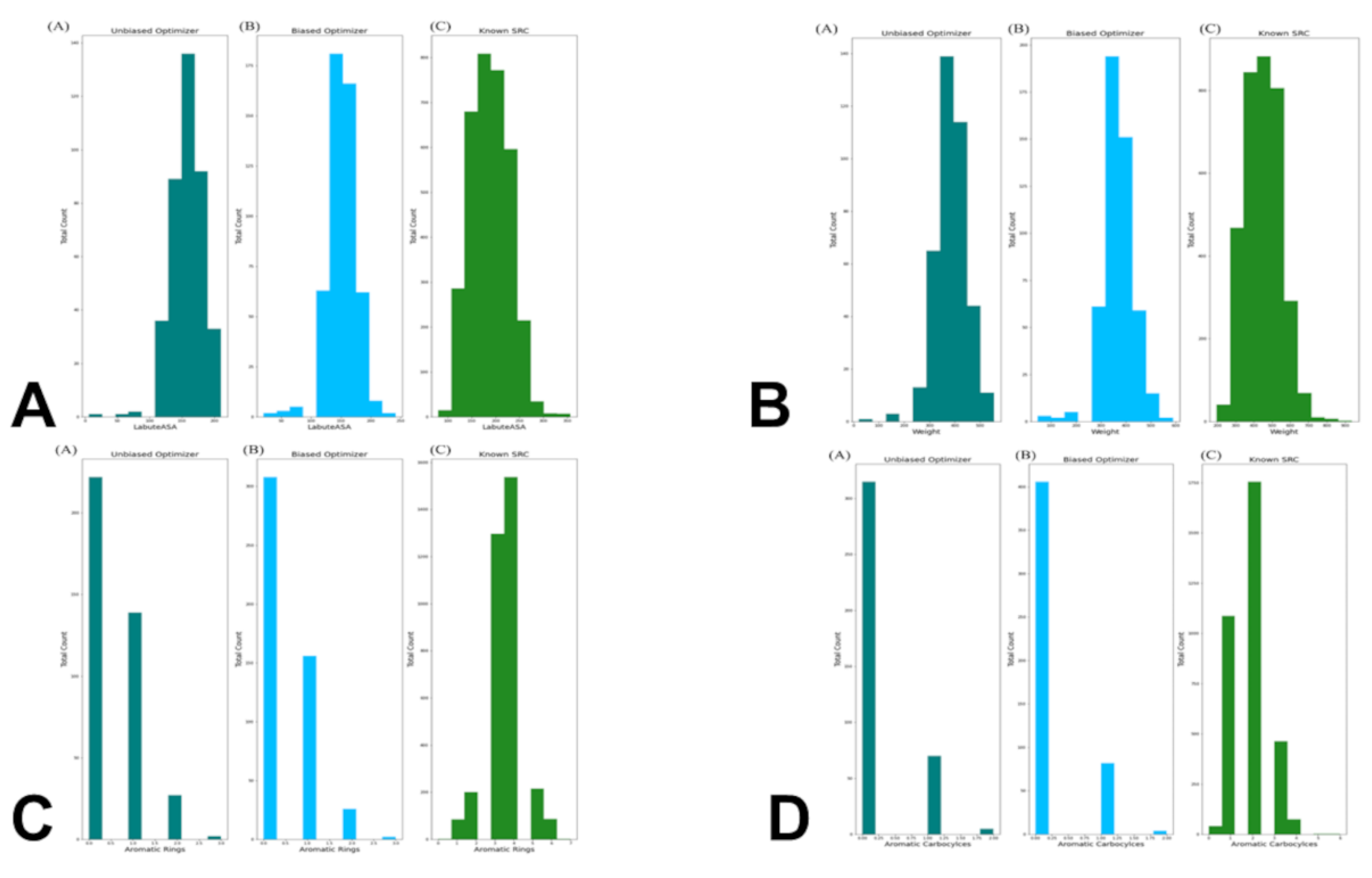

To dissect this discrepancy, we compared the distributions of the top KIL-informative features between generated molecules and real SRC inhibitors (

Figure 6). LabuteASA and molecular weight were well-aligned: both optimizers produced molecules peaking at 150–200 Ų and ~400 Da, closely mirroring the ~200 Ų and ~500 Da peaks of real inhibitors (

Figure 6A,B). Most critically, aromatic complexity was severely underrepresented. Real SRC inhibitors show a broad distribution of 1–6 aromatic rings, with a strong peak at 3–4 rings—hallmarks of ATP-competitive binders that engage in π-stacking. In stark contrast, >80% of BO-generated molecules contained 0 or 1 aromatic ring, and none exceeded 3 rings (

Figure 6C). A similar deficit was observed for aromatic carbocycles, where real inhibitors peak at 2 rings while generated molecules overwhelmingly contain none (

Figure 6D). Hence, BO excelled at tuning “drug-likeness” (QED, logP, SAS) but was not sufficiently robust at reproducing the topological grammar of kinase binding. This suggests that BO, constrained by ChemVAE SMILES-based latent space and the scalar KIL objective, could not effectively navigate to regions encoding multi-ring scaffolds.

In summary, Bayesian Optimization successfully generated novel, valid, and drug-like molecules with moderate-to-high predicted SRC inhibition potential. However, it systematically failed to recover the aromatic ring complexity that defines ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors—a failure that cannot be attributed to poor scoring, but to inherent limitations in the ChemVAE latent space. The results demonstrate that even a well-calibrated, interpretable scoring function like KIL cannot compensate for a generative engine that cannot access the relevant chemical subspaces. This finding not only reports on our specific outcomes but also reveals a fundamental challenge in generative chemistry: the difficulty of optimizing scalar objectives that fail to capture topological complexity, and the risk of overfitting surrogate descriptors that do not fully reflect biological reality.

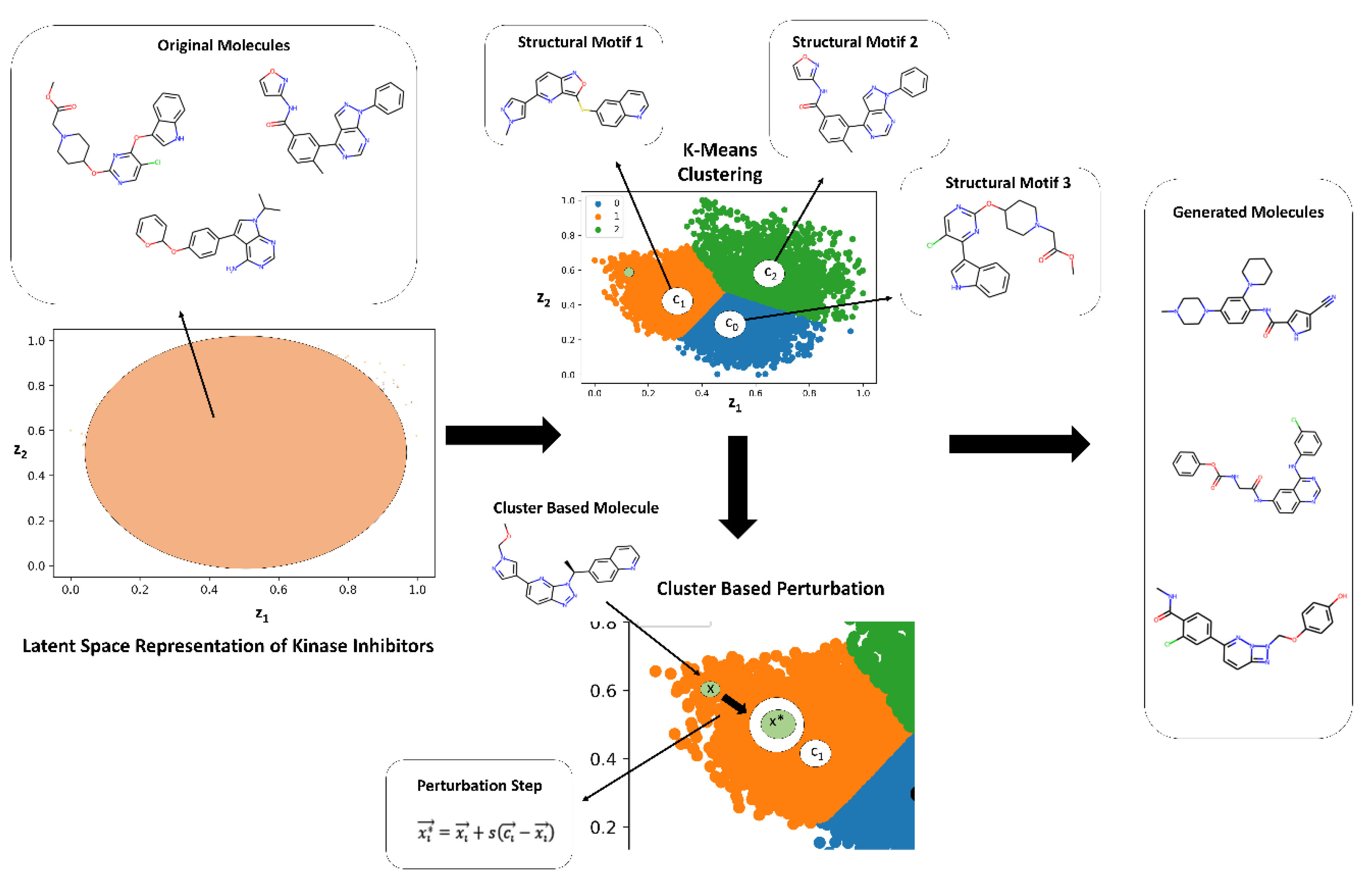

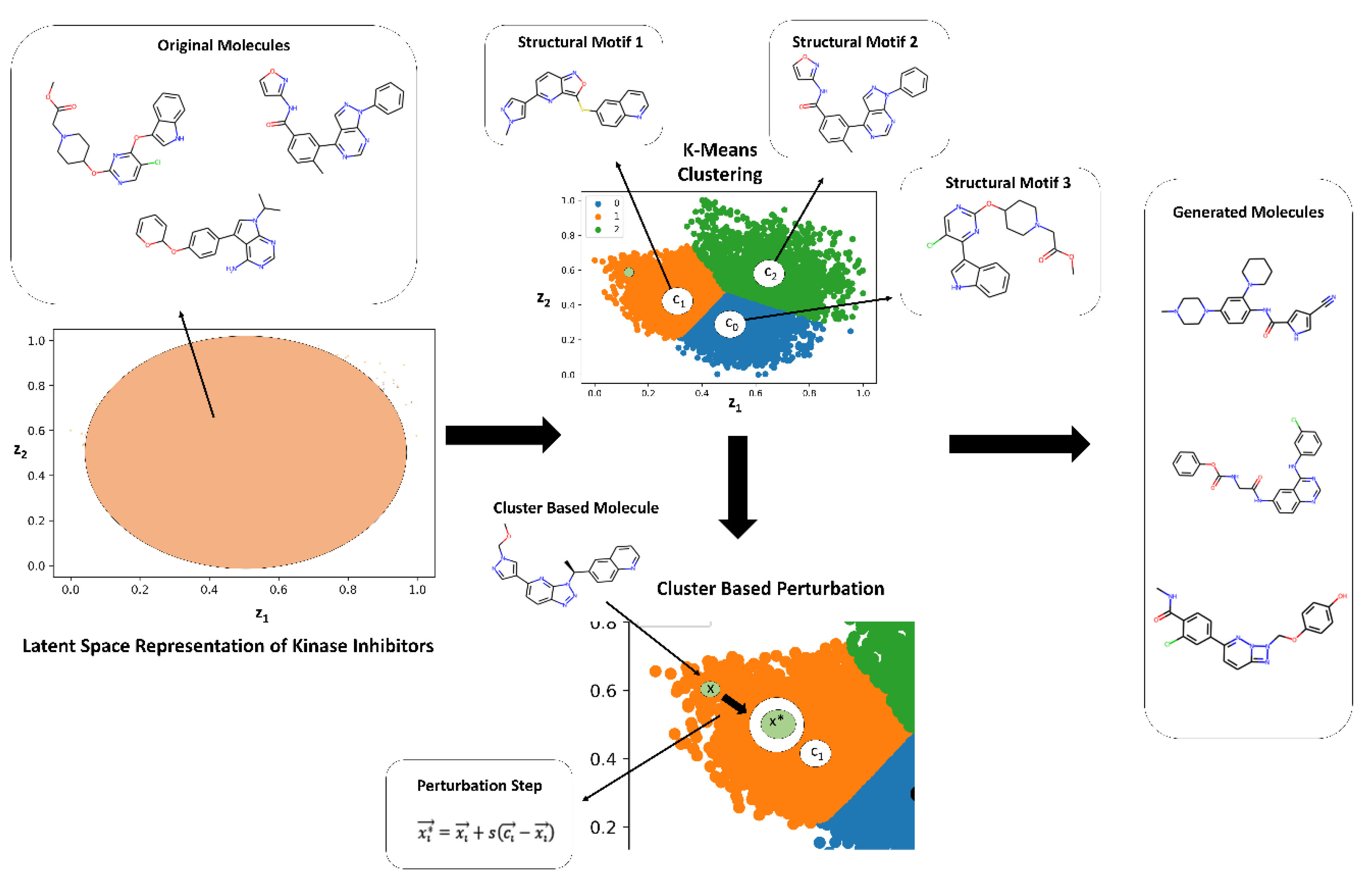

3.4. Targeted Local Latent Neighborhood Sampling Recovers Pharmacophoric Complexity

While Bayesian Optimization enabled efficient global sampling of the kinase inhibitor manifold, it could not generate molecules with the multi-ring aromatic architectures characteristic of clinical SRC inhibitors. To address this, we further expanded on our earlier work [

87] and developed a targeted latent space remodeling strategy that leverages the intrinsic organization of the ChemVAE embedding to guide scaffold transformation. This approach emphasizes guided exploration of high-density regions that are revealed in the latent space analysis contrasting random molecules with kinase inhibitors. Recognizing that kinase inhibitors form chemically coherent neighborhoods in latent space—even across distinct target families—we applied K-means clustering to partition the manifold into three structurally homogeneous regions, each enriched for shared scaffold motifs such as fused heterocycles, hinge-binding cores, or aliphatic linkers.

We used clustering in the latent space to find interpretable linear directions in the latent space that optimize the KIL score and enable morphing of kinase molecules into space of SRC kinase inhibitors. In this approach it is assumed based on the latent space analysis that molecules with similar structures tend to cluster in the latent space and that interpolating two molecules x1 and x2, represented by latent vectors z1 and z2, can lead to intermediate molecules whose structures gradually change from x1 to x2. Since molecular structures correlate with molecular properties, these assumptions imply that molecules with comparable properties would cluster together and interpolating two molecules with different values of the molecular property could lead to gradual changes in molecular structures. By performing cluster-based analysis in the latent representation of the molecules, the generative design approach encourages ChemVAE to explore the high-density distinct areas of the latent space for molecule generation while also facilitating morphing of the kinase molecules from different families into SRC kinase inhibitors. In this approach, the properties of generated molecules can be controlled by sampling latent representations along linear directions to optimize the kinase inhibition likelihood metric. The targeted latent space remodeling strategy includes non-biased and biased changes to the latent space. First, molecules in a non-biased manner are clustered into groups allowing molecules with comparable properties to gather. We assume that the molecules clustered for each cluster contain certain molecular and chemical properties. To then transform these molecules, we invoke a controllable step of cluster-based local neighborhood sampling. Using the centroid of each cluster as the representative of the properties, we navigate every data point in the cluster closer to the centroid by optimizing a set of parameters. By implementing a cluster-based local neighborhood sampling, we efficiently explore and navigate the latent space along interpretable and controllable directions yielding a diverse set of novel molecules and causing various molecular scaffolds to emerge. It is worth noting that the resulting score/output of the feature-based kinase inhibition likelihood classifier represents the probability that a molecule can be deemed as an SRC kinase inhibitor. The produced molecules are evaluated with the classifier during targeted latent space remodeling and when the probability output > 0.7 we refer to these molecules as potential SRC kinase-like inhibitors as according to the classifier the generated molecules would have > 70% chance to belong this category (

Figure 7).

During cluster-based stage of the process, 1,500 encoded molecules from different kinase families were selected and processed through a series of experiments to obtain the optimal parameters of the targeted remodeling scheme that leads to a high yield of valid generated molecules, while simultaneously achieving the objective of transforming the kinase molecules to potential SRC kinase inhibitors. The three main parameters of the clustering in the latent space were evaluated and optimized to ensure optimal generation of valid molecules: the number of clusters assigned, the value of the scaling factor in the local neighborhood sampling, and the optimal level of noise. We found that 3-cluster based split, with a scaling factor

for the centroid-based remodeling, and a noise level of 5.0 provided the optimal set of parameters to guarantee a high generation yield of valid and novel compounds. Within each cluster, we performed targeted local sampling where molecules were shifted incrementally toward the cluster centroid using a controlled interpolation (scaling factor

s = 0.8) and minimal stochastic noise (

Figure 7). This directed navigation preserved chemical validity while steering generation toward high-density zones rich in pharmacophoric features. The approach yielded a three-fold increase in valid output compared to random sampling and, critically, recovered multi-ring aromatic systems that were systematically absent in Bayesian Optimization (BO) outputs.

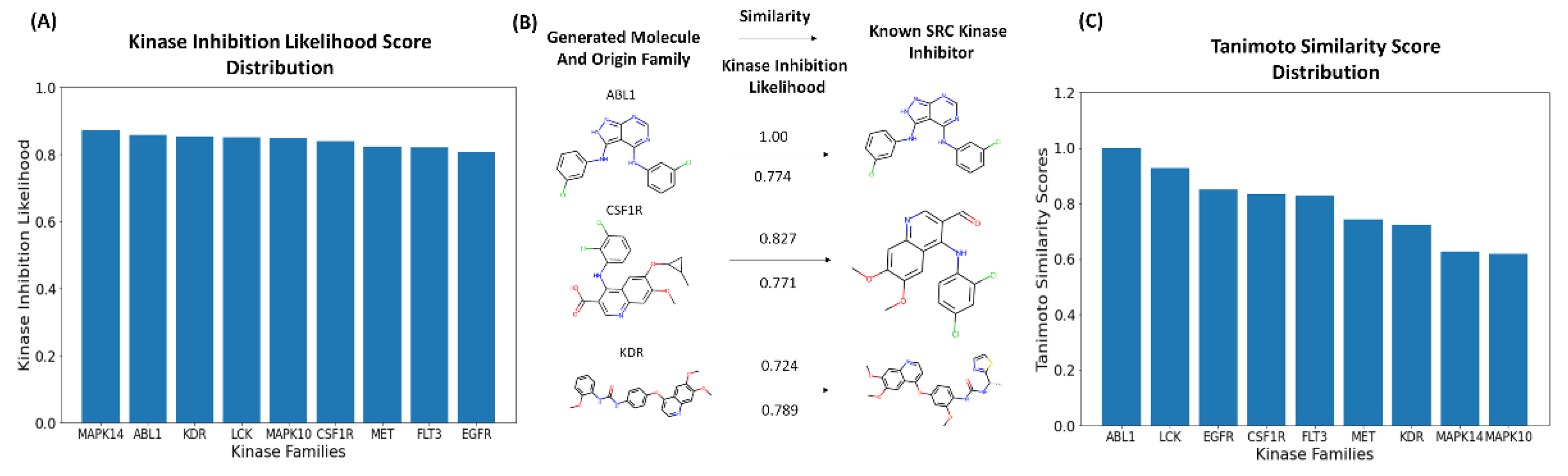

We also investigated the distribution of the generated molecules featuring the high kinase inhibition likelihood scores (> 0.75) as a function of the originated kinase family (

Figure 8A). Strikingly, it was observed that the perturbation-based approach can produce novel valid molecules with the high kinase inhibition likelihood probability when the generative process originates from known inhibitors targeting any of the explored kinase families. This indicates that a combination of clustering and perturbation-based targeted exploration of the latent space allows for efficient chemical transformation of existing kinase molecules from all represented families. To evaluate similarity between the generated molecules and known SRC kinase inhibitors, we examined the fraction of the generated molecules with the high Tanimoto similarity coefficient values. The Tanimoto similarity coefficient is a metric that compares the molecular similarity of two compounds using Morgan fingerprint analysis [

111]. Molecules with Tanimoto coefficient values that are above 0.75 are considered to have high similarity with the reference molecule.

Interestingly, the generated molecules originated from LCK inhibitors produced the largest fraction of novel kinase-like compounds (~ 40%) with the high similarity to the SRC kinase inhibitors. We also observed that the generated molecules initiated from inhibitors of ABL1, LCK and EGFR produced the dominant number of kinase-like novel molecules with the highest similarity coefficients to known SRC inhibitors (

Figure 8B). It is worth noting that the generated molecules originated from inhibitors of ABL1 and LCK yielded the highest similarity scores with SRC inhibitors, with most molecules displaying Tanimoto similarity coefficient > 0.8. The SRC/ABL and SRC/LCK duality of many kinase drugs is well recognized, most notably exemplified by dual SRC/ABL drugs Dasatinib and Ponatinib.

In addition, we found that the generated molecules originated from inhibitors of EGFR, CSF1R, FLT3, and MET families also produced good similarity to the known SRC inhibitors. These findings may imply that local neighborhood navigation of the latent space that optimized directionality of exploration based on the KIL score could facilitate generation of valid molecules in different areas of the latent space. Indeed, a substantial number of the generated molecules emerged from mapping connections in the latent space between SRC, LCK and ABL inhibitors. At the same time, the algorithm facilitated efficient sampling of the latent space and corresponding transformations of the kinase inhibitors targeting other families into molecules with both the high kinase inhibition likelihood and the high similarity to the SRC inhibitors.

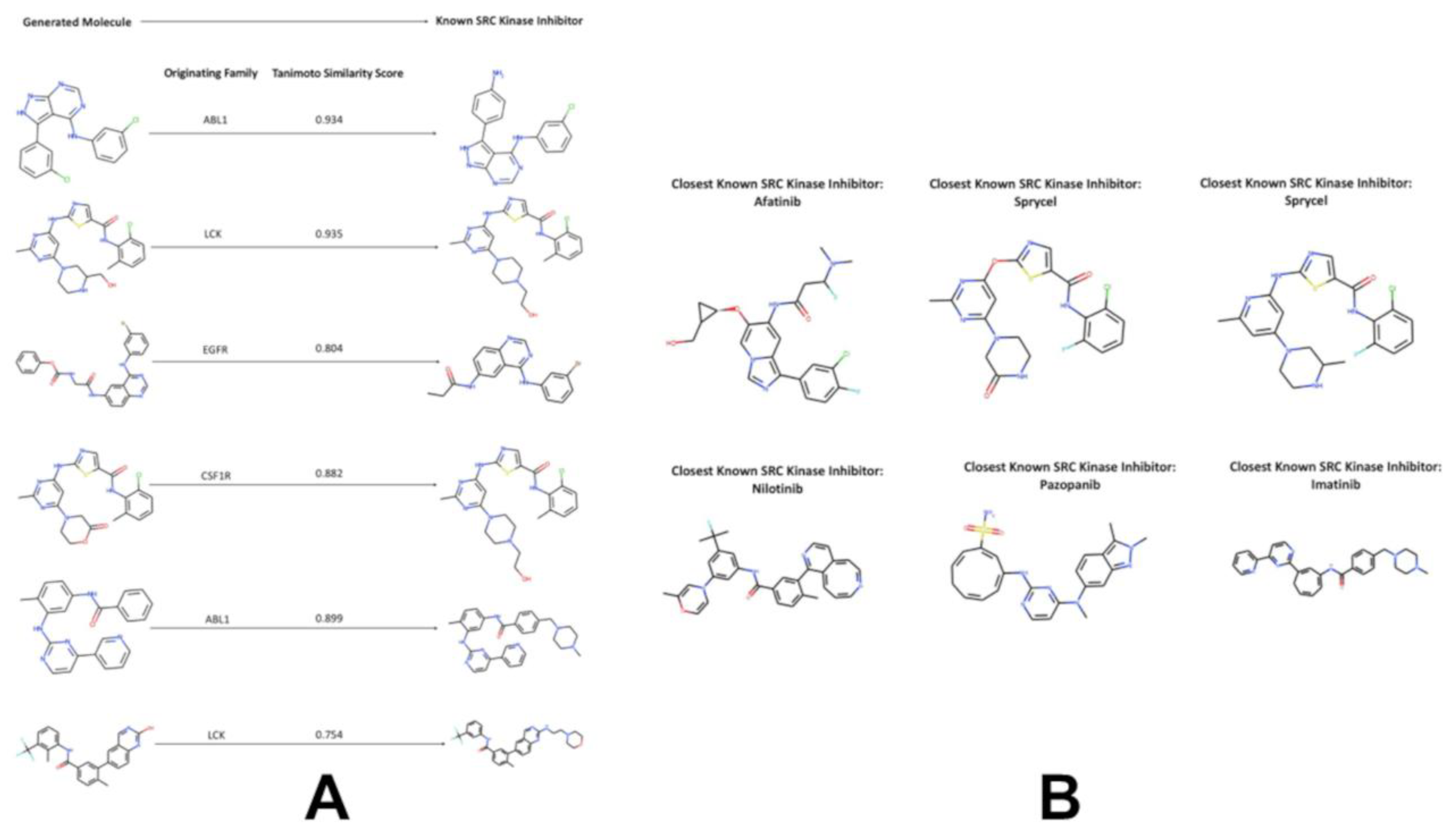

This process also enabled cross-family scaffold transformation: LCK and EGFR inhibitors, which occupy regions of latent space proximal to SRC, showed the highest conversion efficiency (19–23% of total output), whereas MAPK14 and FLT3 contributed minimally (3–7%). LCK and MAPK10 emerged as the most productive sources of unique, high-similarity candidates, suggesting that certain kinase scaffolds possess inherent “plasticity” for repurposing into SRC-targeted leads. Our results revealed the important role of the LCK family, which accounts for ~40% of all high-similarity outputs, far surpassing other families. This is not a sampling artifact but reflects a genuine topological affinity between LCK and SRC inhibitor spaces, directly enabled by our guided remodeling approach. To illustrate the output of the generative pipeline, we compiled a list of several representative generated SRC-like kinase molecules that originated from the inhibitors of different kinase families. The presented molecules were characterized by the high kinase inhibition likelihood and a considerable similarity to the existing SRC kinase inhibitors (

Figure 9A). We noticed that some of the novel valid molecules with the highest similarity to the SRC inhibitors were produced starting from the latent space regions of the ABL1 and LCK kinase inhibitors. A sample of generated molecules reflected both the diversity of molecular scaffolds and high degree of synthetic feasibility that were enabled through local remodeling approach (

Figure 9). Molecules originating from the EGFR and LCK clusters—families known for quinazoline and pyrrolopyrimidine scaffolds—were successfully remodeled into novel chemotypes containing 3–5 aromatic rings, including quinazoline- and pyrimidine-like cores characteristic of clinical SRC inhibitors (

Figure 9B).

Importantly, these remodeled molecules maintained physiologically relevant logP values (2–4)—in contrast to some BO candidates with non-ideal logP (< 0)—indicating better preservation of the hydrophobic balance required for kinase binding (Supporting Information,

Figures S4-S8). These findings highlight a fundamental duality in generative design. Bayesian Optimization follows a

“property-first

” paradigm: it optimizes global drug-likeness metrics under the assumption that chemical plausibility implies biological activity. This succeeds for flexible targets but fails for kinases, where function is dictated by precise 3D pharmacophores. In contrast, guided local sampling adopts a

“scaffold-first

” philosophy: by anchoring generation in structurally coherent neighborhoods, it ensures that key binding motifs are preserved, even as novel chemotypes emerge. Both strategies, however, collide with the limits of SMILES-based representation. ChemVAE learns a continuous manifold, but it cannot guarantee that ring systems—encoded as sequential tokens—are preserved under interpolation or local neighborhood sampling. The latent space contains the seeds of complexity, but the decoding bottleneck—the transformation from latent vector to SMILES—often collapses them.

3.5. Computational Docking Validation of Generated Molecules Reveals High-Affinity Binding to the SRC Kinase Active Site

To bridge the gap between silico generation and biological plausibility, we performed computational molecular docking on a curated set of high-scoring, structurally diverse molecules generated by our local neighborhood sampling-based pipeline. These molecules—selected for their high KIL scores (>0.75), favorable ADMET properties, and significant Tanimoto similarity (>0.7) to known SRC inhibitors—were docked into the ATP-binding site of human SRC kinase (PDB ID: 2SRC). The goal was to assess whether these novel, AI-generated compounds could form stable, energetically favorable interactions within the conserved catalytic cleft—a critical step toward validating their potential as therapeutic leads. The five molecules selected for docking were chosen based on two criteria. We prioritized molecules derived from families with high transformation potential (e.g., LCK, ABL1, EGFR), as identified in our local neighborhood sampling analysis. All molecules exhibited >0.75 Tanimoto similarity to at least one known SRC inhibitor indicating they retain core pharmacophoric features while introducing novel scaffolds.

The SRC kinase structure was prepared using Schrödinger’s Protein Preparation Wizard: hydrogen atoms were added, bond orders assigned, and water molecules beyond 5 Å of the binding site removed. Grids for AutoDock Vina were centered on the ATP-binding site, with dimensions optimized to encompass key residues (Met341, Leu393, Glu310, Lys295). Each molecule was docked independently, with Vina’s scoring function used to rank poses by predicted binding affinity. The top pose for each ligand was selected for analysis based on cluster size and energy score. All six generated molecules docked successfully into the SRC active site, forming key interactions with conserved residues essential for ATP-competitive inhibition including hydrogen bonding with Glu310, π–π stacking with Leu393 and Thr338 and hydrophobic burial near Met341 and Val323 (

Table S1). Notably, the molecule originating from the ABL1 family (Tanimoto = 0.934) formed an additional hydrogen bond with Asp404, a residue not typically engaged by first-generation inhibitors, suggesting potential for improved selectivity. Similarly, the LCK-derived molecule (Tanimoto = 0.935) adopted a conformation that closely mimicked the binding mode of Sprycel, with its central pyridine ring perfectly aligned for π-stacking with Leu393. We further compared the binding poses of our generated molecules to those of six clinically relevant SRC inhibitors: Afatinib, Sprycel, Nilotinib, Pazopanib, Imatinib, and Dasatinib (

Figure 9B,

Table S1). As summarized in

Table S1, all six generated molecules achieved binding affinities comparable to or better than clinical SRC inhibitors. Our top-ranked compound—the ABL1-derived scaffold—overlapped well with Afatinib, sharing nearly identical orientation and key interactions, despite having a distinct chemical scaffold. Another generated molecule, derived from CSF1R, closely mirrored the binding mode of Sprycel, engaging the same hinge residue (Glu310) and hydrophobic pocket (Leu393, Val323) with comparable energy. This structural mimicry is not coincidental. It reflects the latent space topology we identified earlier: molecules from families like ABL1 and LCK occupy regions of ChemVAE space that are topologically proximal to SRC, enabling their transformation into SRC-like chemotypes through targe.

Most compellingly, our docking analysis confirmed that the multi-ring aromatic systems—which were systematically underrepresented in Bayesian Optimization outputs but recovered through perturbation-based engineering—are not just synthetic artifacts; they are functionally essential. The top-scoring molecules all contained 3–5 fused or linked aromatic rings, which were precisely positioned to engage the hydrophobic cleft and hinge region. One molecule, derived from EGFR, featured a unique bicyclic thiophene core that formed optimal van der Waals contacts with Met341—a feature absent in most clinical inhibitors and potentially exploitable for selectivity. These findings demonstrate that our generative pipeline—guided by KIL scoring, perturbation-based latent space engineering, and multi-metric validation—can produce not only novel, drug-like compounds, but molecules with high predicted affinity and specific, target-relevant binding modes. The fact that these molecules bind to the SRC active site with energies rivaling clinical drugs suggests they are strong candidates for experimental validation. Computational docking of our top-generated molecules confirms that the novel chemotypes produced by our framework are not mere statistical artifacts, but structurally and energetically viable ligands for the SRC kinase active site. By combining interpretable scoring (KIL), scaffold-aware local neighborhood sampling, and 3D validation, we have bridged the gap between de novo design and biological relevance. These results provide a compelling rationale for advancing these compounds into in vitro assays and preclinical development.

4. Discussion

This study presents a modular, interpretable, and chemistry-first framework for the de novo design of SRC kinase inhibitors, integrating deep generative modeling (ChemVAE), a chemically grounded scoring function (KIL), probabilistic optimization (Bayesian Optimization), and scaffold-aware latent space local neighborhood sampling. Across two complementary strategies, global exploration via Bayesian search and local transformation via cluster-guided engineering—we generated novel, drug-like molecules with moderate-to-high predicted SRC inhibition potential. Yet our most significant contribution lies not in the molecules themselves, but in the rigorous diagnosis of the capabilities and limitations of current generative architectures when applied to topologically constrained targets like kinases. A central insight of this work is that the ChemVAE latent space encodes a functional grammar of kinase inhibition. Kinase inhibitors—despite spanning ten distinct families—collapse into a dense, low-volume manifold that is sharply segregated from general drug-like matter. Within this manifold, SRC inhibitors exhibit the broadest structural diversity, occupying the largest volume and serving as a “hub” that overlaps with all other families. This topological organization is not imposed by labels but learned implicitly from SMILES syntax, suggesting that molecular sequence encodes functional semantics. Critically, this structure enables rational scaffold transformation: LCK-derived molecules were 2–4× more likely to achieve high similarity to known SRC inhibitors than those from other families, reflecting their shared pharmacophoric and topological heritage. This finding validates the use of latent space geometry as a map for guided scaffold hopping, with SRC emerging as an ideal target for cross-family repurposing. However, this same latent space also reveals a fundamental representational ceiling. Both Bayesian Optimization and local neighborhood sampling-based generation systematically failed to recover the multi-ring aromatic systems that define ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors—most generated molecules contained ≤1 aromatic ring, and none exceeded three, despite aromatic ring count being a top KIL feature. This “representation gap” cannot be attributed to poor scoring or insufficient optimization; it stems from the inherent limitations of SMILES-based VAEs, which entangle ring topology across latent dimensions and often corrupt complex pharmacophores during decoding. Our results thus confirm a critical hypothesis: no amount of scoring refinement can compensate for a generative engine that cannot access the relevant chemical subspaces. This limitation underscores the necessity of interpretable, hybrid design strategies. The Kinase Inhibition Likelihood (KIL) metric—built on 20 RDKit-derived features including LabuteASA, molecular weight, and aromatic ring count—provided a transparent signal that enabled us to trace failures directly to molecular properties. When BO generated a molecule with high KIL but low aromatic complexity, we could diagnose the issue as a decoding failure, not a scoring error. This interpretability is absent in black-box deep predictors and is invaluable for iterative refinement. Moreover, KIL’s focus on SRC-specificity, rather than generic kinase-likeness, allowed us to prioritize candidates that truly resemble SRC inhibitors, not just ATP-binders.

Our comparative analysis of generative strategies also challenges common assumptions in the field. Biasing Bayesian Optimization with known SRC actives conferred no meaningful advantage in structural novelty, similarity, or quality; instead, it trapped search in a narrow local optimum, causing the repeated generation of variants of only one or two reference scaffolds. In contrast, Unbiased BO produced more diverse, higher-average-KIL molecules, demonstrating that broad exploration outweighs local exploitation in early-stage lead discovery. Similarly, local neighborhood sampling-based engineering outperformed BO in pharmacophoric fidelity, recovering 3–5 ring systems by leveraging cluster structure—yet it too was constrained by the underlying SMILES representation. These findings highlight that no single method is sufficient; rather, complementary approaches are needed to balance global property optimization with local structural recovery.

At first glance, our decision to build upon ChemVAE—a SMILES-based variational autoencoder now widely regarded as outdated in the era of graph neural networks and 3D diffusion models—may appear regressive. After all, it is well documented that SMILES representations suffer from non-uniqueness, poor handling of ring systems, and decoding failures that corrupt pharmacophoric complexity—limitations we further confirm in this work. So why look backward? The answer lies in a fundamental principle: to advance AI-driven drug discovery, we must first rigorously understand why and how current tools fail. While modern end-to-end models like RFdiffusion or GeoDiff offer astonishing generative power, they operate as black boxes—making it difficult to isolate whether a failure stems from representation, scoring, search strategy, or data bias. In contrast, ChemVAE provides a transparent, modular, and interpretable scaffold in which each component—encoding, scoring, optimization, local neighborhood sampling—can be independently probed, validated, and debugged using medicinal chemistry principles. We chose ChemVAE not because it is the most powerful generative model, but because it is the ideal diagnostic platform. By coupling it with a chemically grounded, feature-based scoring function (KIL), Bayesian optimization, and cluster-aware local neighborhood sampling, we created a controlled experimental system in which the representation gap could be cleanly isolated and quantified. Our results—such as the systematic under-generation of aromatic rings despite their high importance in KIL, or the privileged transformability of LCK into SRC-like chemotypes—reveal structural and functional truths about kinase inhibitor space that would be obscured in a monolithic diffusion pipeline.

Moreover, this work responds to a growing concern in the field: the decline of interpretability in pursuit of performance. As generative models grow more complex, they risk becoming “alchemy engines”—producing novel molecules without explaining why they work. Our pipeline reaffirms that chemistry must guide AI, not the reverse. The fact that a “legacy” framework, when augmented with domain knowledge, can yield actionable insights into scaffold hopping, latent space organization, and generative failure modes underscores a critical message: algorithmic novelty alone is insufficient; chemical fidelity is paramount. Indeed, our work affirms that the future of drug discovery lies not in fully autonomous AI, but in AI–chemist collaboration. The KIL framework, though modular, embodies this philosophy: it aligns AI with domain knowledge, prioritizes pharmacophoric fidelity over mere chemical plausibility, and validates candidates through integrated assessment (KIL + Tanimoto + ADMET). As the field adopts increasingly powerful foundation models, this chemistry-first paradigm will remain essential to ensure that generated molecules are not just novel, but biologically relevant. In conclusion, this study provides both a caution and a compass. It cautions that SMILES-based generative models, even when guided by robust scorers, are fundamentally limited in their ability to capture the topological complexity of kinase inhibitors. Our study also offers a compass: by diagnosing these limits, showcasing the power of interpretable design, and revealing how latent space encodes functional relationships, we provide a blueprint for next-generation hybrid systems.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a modular, chemistry-first generative framework for de novo SRC kinase inhibitor design, integrating deep generative modeling (ChemVAE), interpretable machine learning (KIL), probabilistic optimization (Bayesian Optimization), and structure-aware latent space remodeling. Across two complementary strategies—global exploration via Bayesian search and local transformation via cluster-guided targeted local neighborhood sampling, we successfully generated novel, drug-like molecules with moderate-to-high predicted SRC inhibition potential. However, our most significant contributions lie not in the molecules themselves, but in the rigorous diagnosis of what works, what does not, and why—providing a foundational benchmark for the next generation of AI-driven drug discovery. Our pipeline demonstrates three practical strengths that remain relevant even in the era of end-to-end generative AI: Interpretability enables debugging and refinement: The KIL scoring function—built on chemically meaningful RDKit features—allowed us to trace failures directly to molecular properties (e.g., underrepresentation of aromatic rings). This transparency is absent in black-box deep scorers and is invaluable for iterative design. Latent space structure encodes functional relationships: We showed that kinase inhibitors form a coherent manifold in ChemVAE space, with LCK and SRC families exhibiting exceptional proximity. This enabled successful scaffold transformation—LCK-derived molecules were 2–4× more likely to achieve high similarity to known SRC inhibitors than those from other families—demonstrating that latent geometry can guide rational scaffold hopping. Hybrid strategies outperform single-method approaches: While Bayesian Optimization excelled at global drug-likeness tuning, targeted local neighborhood sampling engineering recovered critical pharmacophoric complexity (e.g., multi-ring systems) that BO missed. This synergy underscores the value of multiple generative lenses in lead discovery. Despite its strengths, our framework exposed a fundamental limitation: SMILES-based VAEs cannot reliably represent or manipulate complex ring topologies. Both BO and targeted local neighborhood sampling generated molecules with ≤3 aromatic rings—far fewer than the 3–6 rings typical of clinical SRC inhibitors—even when aromatic ring count was a top KIL feature. This “representation gap” means that no amount of scoring refinement can compensate for a generative engine that cannot access the relevant chemical subspaces. Moreover, biasing optimization with known actives reduced scaffold diversity without improving quality, trapping search in narrow local optima. This challenges the common assumption that seeding with reference compounds universally enhances generative outcomes.

Our work exemplifies a chemistry-first paradigm in AI-driven drug design: rather than treating molecules as abstract tokens, we grounded every component—scoring, generation, validation—in medicinal chemistry principles. This approach prioritizes pharmacophoric fidelity over mere chemical plausibility, uses interpretable features to align AI with domain knowledge, Validates candidates through multi-metric assessment (KIL + Tanimoto + ADMET). This approach yielded three critical lessons. First, we confirmed that molecular syntax encodes functional semantics: the ChemVAE latent space—learned without target labels—spontaneously organizes kinase inhibitors into a coherent, low-dimensional manifold, with SRC acting as a structural “hub” that overlaps all other families. This organization enabled rational scaffold transformation, most strikingly in the LCK → SRC conversion, where 40% of high-similarity output originated from a single family. This demonstrates that latent geometry can serve as a map for guided chemical innovation principles that transcend the underlying generative architecture. Second, we exposed a representation gap that no amount of scoring refinement can overcome. Despite aromatic ring count being a top feature in our interpretable Kinase Inhibition Likelihood (KIL) metric, both Bayesian Optimization and targeted local neighborhood sampling failed to generate molecules with >3 aromatic rings—a hallmark of clinical SRC inhibitors. This failure is not a flaw in optimization, but a fundamental limitation of SMILES-based decoding, which entangles ring topology and corrupts pharmacophoric complexity. By isolating this bottleneck in a transparent pipeline, we provide a diagnostic benchmark that even state-of-the-art models must confront. Third, we reaffirmed that chemistry must guide AI, not the reverse. The KIL framework—built on medicinal chemistry principles rather than abstract embeddings—enabled us to trace generative failures to specific molecular properties, prioritize candidates through multi-metric validation (KIL + Tanimoto + ADMET), and reject the illusion that “drug-likeness” alone ensures biological relevance. Our finding that biasing with known actives reduces diversity without improving quality further challenges heuristic assumptions in generative design and underscores the value of unbiased exploration in lead discovery.

By demonstrating how latent space structure encodes functional relationships between kinase families (e.g., the privileged transformability of LCK into SRC-like chemotypes), we provide both a critical benchmark for current AI and a blueprint for hybrid systems that blend algorithmic sophistication with domain knowledge. By formulating our work as a benchmark of limitations, we provide an empirical framework for the next generation of AI-driven kinase inhibitor design. While the frontier of generative AI is moving toward end-to-end, structure-aware models that reduce reliance on handcrafted scorers, grounding AI in medicinal chemistry principles remains central to successful drug design.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the Random Forest Model used for the kinase inhibition likelihood classifier.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the Random Forest Model used for the kinase inhibition likelihood classifier.

Figure 2.

An Overview of Chemical to Continuous Space Translation using ChemVAE Encoding mechanism.

Figure 2.

An Overview of Chemical to Continuous Space Translation using ChemVAE Encoding mechanism.

Figure 3.

PCA and heatmaps of the latent spaces for GDB-17 small molecules and kinase inhibitors. (A) The 2-dimensional latent space representation of kinase molecules and GDB-17 small molecules dataset. Kinase molecules are shown in distinct colors for specific families, whereas GDB small molecules are shown in green dots. The locations of the latent space for these classes of molecules are pointed by arrows and annotated. (B) The 2-dimensional latent space representation of the kinase inhibitors from all 37 kinase families. The 10 major kinase families in the dataset are SRC (red), ABL1(blue), EGFR (gold), CSF1R (orange), FLT3 (magenta), KDR (brown), LCK (turquoise), MAPK14 (gray), MET (honeydew). (C) The 2-dimensional latent space representation of the ABL kinase inhibitors (in blue) and SRC kinase inhibitors (in red). (D) The 2-dimensional heatmap of latent space representation for GDB-17 molecules and kinase inhibitors from all studied kinase families. (E) The 2-dimensional heatmap of latent space representation for the kinase inhibitors. The density regions are color-coded with the high-density areas in yellow color, whereas low density regions tend towards purple.

Figure 3.

PCA and heatmaps of the latent spaces for GDB-17 small molecules and kinase inhibitors. (A) The 2-dimensional latent space representation of kinase molecules and GDB-17 small molecules dataset. Kinase molecules are shown in distinct colors for specific families, whereas GDB small molecules are shown in green dots. The locations of the latent space for these classes of molecules are pointed by arrows and annotated. (B) The 2-dimensional latent space representation of the kinase inhibitors from all 37 kinase families. The 10 major kinase families in the dataset are SRC (red), ABL1(blue), EGFR (gold), CSF1R (orange), FLT3 (magenta), KDR (brown), LCK (turquoise), MAPK14 (gray), MET (honeydew). (C) The 2-dimensional latent space representation of the ABL kinase inhibitors (in blue) and SRC kinase inhibitors (in red). (D) The 2-dimensional heatmap of latent space representation for GDB-17 molecules and kinase inhibitors from all studied kinase families. (E) The 2-dimensional heatmap of latent space representation for the kinase inhibitors. The density regions are color-coded with the high-density areas in yellow color, whereas low density regions tend towards purple.

Figure 4.

The performance and feature importance analysis of the chemical feature-based kinase inhibition classifier. (A) The Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) is a graph where sensitivity is plotted as a function of 1-specificity. The area under the ROC is denoted as AUC. The ROC-AUC graph measures the performance of the classifier in differentiating the kinase inhibitor molecules from GDB-17 small molecules (B) The feature importance analysis of the model. The importance of features is listed in descending order.

Figure 4.

The performance and feature importance analysis of the chemical feature-based kinase inhibition classifier. (A) The Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) is a graph where sensitivity is plotted as a function of 1-specificity. The area under the ROC is denoted as AUC. The ROC-AUC graph measures the performance of the classifier in differentiating the kinase inhibitor molecules from GDB-17 small molecules (B) The feature importance analysis of the model. The importance of features is listed in descending order.

Figure 5.

The average KIL scores of the molecules generated from the Biased and Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer (A), the max KIL scores of the molecules generated from the Biased and Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer (B), the average QED scores, (C), the average SAS scores (D) and the average logP scores (E) of the molecules generated from the Biased and Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer, in comparison to the known SRC kinase inhibitors. The unbiased histogram is in turquoise bars, the biased histogram is in light blue bars, and the SRC kinase inhibitor histogram is in green.

Figure 5.

The average KIL scores of the molecules generated from the Biased and Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer (A), the max KIL scores of the molecules generated from the Biased and Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer (B), the average QED scores, (C), the average SAS scores (D) and the average logP scores (E) of the molecules generated from the Biased and Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer, in comparison to the known SRC kinase inhibitors. The unbiased histogram is in turquoise bars, the biased histogram is in light blue bars, and the SRC kinase inhibitor histogram is in green.

Figure 6.

Histograms of the distribution of the LabuteASA values (A), the molecular weight (B), the number of aromatic rings (C) and the number of aromatic carbocycles in the generated molecules using the Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer, the Biased Bayesian Optimizer, and compared to the set of known SRC kinase inhibitors. The unbiased histogram is in turquoise bars, the biased histogram is in light blue bars, and the SRC kinase inhibitor histogram is in green.

Figure 6.

Histograms of the distribution of the LabuteASA values (A), the molecular weight (B), the number of aromatic rings (C) and the number of aromatic carbocycles in the generated molecules using the Unbiased Bayesian Optimizer, the Biased Bayesian Optimizer, and compared to the set of known SRC kinase inhibitors. The unbiased histogram is in turquoise bars, the biased histogram is in light blue bars, and the SRC kinase inhibitor histogram is in green.

Figure 7.