1. Introduction

The term "technical textiles" refers to textile goods that are used for performance or functional elements rather than aesthetic qualities. This is what is meant when we talk about "technical textiles" in their most general sense. The development of "Technical Textiles" is the term used to describe this trend in the textile industry. Although the technical textiles industry has only been around recently, it is currently increasing at a rate that is substantially faster than that of the traditional garment and home textile sectors. The utilization of technical textiles is attributed to their extensive range of applications. The product forms of technical textiles can vary depending on the manufacturer, encompassing fiber, textiles (such as fabrics), units, parts that utilize textiles, or a combination of these three elements(Matsuo, 2008). Technical textiles, which serve diverse applications such as medical textiles, protective clothing, and industrial fabrics, have traditionally relied on synthetic materials and resource-intensive manufacturing methods. However, increasing environmental concerns and stringent regulations have driven the need for sustainable alternatives.

It was projected that each person on the planet used 12.7 kg worth of textile materials in 2014, including those used for clothes, home textiles, carpets, and technical textiles. The volume of synthetic fibers climbed by 5.7% to 54.4 million metric tons in 2014, primarily as a result of a rise in the production of polyester and polyamide. On the other hand, the volume of cellulosic fibers increased by 10.4%, which is equivalent to approximately 6 million metric tons. In comparison, the demand for cotton in 2014 rose by a marginal 0.9%, reaching a total of 23.6 million metric tons. Cotton stocks around the world have reached an all-time high, surpassing 20 million metric tons for the first time (this is primarily due to hoarding in China), which is sufficient to meet 85 percent of current demand(Avadanei et al., 2020). In 2014, synthetic fibers prevailed in the market due to their economic efficiency, although cellulosic fibers witnessed significant growth, presumably fueled by a rising interest in sustainability; concurrently, cotton demand remained stagnant, resulting in an oversupply problem, mainly attributed to substantial inventories in China. Existing research has explored various sustainable fibers, including biodegradable polymers, recycled materials, and bio-based textiles. However, challenges remain in balancing sustainability with performance, durability, and cost-effectiveness. Many studies focus on specific material innovations, yet a holistic approach integrating eco-friendly raw materials, energy-efficient production, and waste reduction strategies is still lacking.

In response to escalating environmental concerns, sustainability has become a central focus for the textile and garment industry(Jahana et al., 2022). Manufacturers are progressively emphasizing sustainable raw materials, creative production methods, and effective recycling systems to mitigate environmental impact(Kumar et al., 2017). The utilization of plant-based fibers like hemp, flax, and bamboo presents a feasible substitute for synthetic fibers, diminishing reliance on petroleum-derived resources and improving biodegradability. Moreover, waste treatment and recycling technologies are essential for reducing textile waste and fostering circularity within the sector. Innovations in sustainable manufacturing methods, such as supercritical CO₂ dyeing and enzymatic textile processing, offer effective strategies for minimizing water and chemical consumption, hence enhancing resource efficiency in textile production.

Despite extensive research on sustainable fibers, manufacturing technologies, and waste reduction measures individually, a comprehensive examination of sustainability over the entire lifecycle of technical textiles is still lacking. Specifically, there is a lack of critical assessment regarding how materials, processes, and disposal pathways collectively impact sustainability outcomes. This review seeks to fill this gap by integrating contemporary research on sustainable materials, production innovations, and circular methodologies, providing a thorough roadmap for the transition to environmentally responsible technical textiles.

2. The Components of Textile Sustainability That Pertain to Technical Textiles

The advancement of technical textiles is progressively influenced by sustainability concepts, which seek to enhance resource efficiency, reduce environmental impact, and ensure product durability without sacrificing performance. The fundamental elements of sustainability in this context comprise:

2.1. Sustainability of Materials

The utilization of natural and regenerated fibers, including jute, flax, hemp, wool, and regenerated cellulose (e.g., lyocell, viscose), diminishes reliance on non-renewable resources and enhances biodegradability at the end of life.

Recycled Materials: Pre-consumer and post-consumer textile waste, along with recycled synthetic materials such as PET, mitigate landfill trash and diminish the environmental impact of raw material production(Luján-Ornelas et al., 2020).

2.2. Chemical and Energy Sustainability

Reduction of Chemical Inputs: Transitioning to less hazardous and biodegradable chemicals (e.g., enzymatic replacements) facilitates safer processing and disposal.

Water and Energy Conservation: Technologies like supercritical CO₂ dyeing markedly diminish water and energy consumption in finishing processes(Hossain et al., 2024).

2.3. Production and Waste Reduction

Cleaner Production Techniques: Enhanced manufacturing minimizes industrial waste and pollutants.

Circular Design and Recycling: Creating for recyclability and establishing take-back procedures enables closed-loop material recovery(Hossain et al., 2024).

2.4. Product Durability and Serviceability

Prolonged Durability: Technical textiles are frequently designed for an extended lifespan, minimizing the necessity for regular replacements.

Repair and Reuse Potential: Facilitating repairability can extend the lifespan of objects, thereby reducing overall material consumption.

2.5. Strategies for End-of-Life

Biodegradability: Selecting biodegradable materials enables textiles to decompose organically at the end of their life cycle.

Recyclability: The use of mono-materials or modular components in design enhances disassembly and recycling efficiency(Luján-Ornelas et al., 2020).

Waste Disposal: Sustainable techniques prioritize the reduction of incineration and landfill disposal by enhancing sorting, collection, and material recovery methods(Edirisinghe et al., 2024).

Although these elements collectively establish the sustainable framework for technical textiles, execution remains uneven throughout the industry. Discussions often focus on material innovation, but the realization of energy-efficient production and ethical disposal is less common. Addressing these disparities necessitates comprehensive lifespan analysis and interdisciplinary cooperation among designers, producers, recyclers, and policymakers.

3. Aspects of Sustainability and Action Plans for Technical Textiles

3.1. Achieving Sustainability in Raw Materials – Textile Fibers

The technical textile industry has traditionally relied on synthetic fibers, such as polyester, polyamide, polypropylene, acrylic, aramid, glass, and carbon fibers, which constitute over 80% of the textile materials employed in diverse applications. While these fibers offer exceptional durability, strength, and performance, they also contribute to considerable carbon emissions, resource depletion, and microplastic contamination, underscoring the need to shift toward sustainable alternatives.

Figure 1 illustrates the diverse kinds of sustainable fibers employed in technical textiles, classified into three main types: recycled synthetic fibers, renewable resources, and regenerated fibers. Using recycled, renewable, and regenerated fibers shows a move toward sustainable production, which means using fewer non-renewable resources and having less of an impact on the environment(Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022a).

-

(a)

Recycled Synthetic Fibers

In 2016, the fiber produced from PET flakes constituted a substantial 44 percent of the total market share among end users(Piribauer & Bartl, 2019). Recycled synthetic fibers are generally sourced from PET bottles, textile remnants, and various consumer waste materials. These fibers facilitate the diversion of waste from landfills and diminish reliance on virgin petroleum-derived inputs. Recycled PET (rPET) is increasingly favored for its reduced energy and water consumption, along with its comparable mechanical strength to virgin PET.

Table 1.

Performance & Environmental Benefits of Recycled PET Fibers(Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022b).

Table 1.

Performance & Environmental Benefits of Recycled PET Fibers(Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022b).

| Property |

Virgin PET |

Recycled PET |

| Energy Consumption |

High |

30-50% lower |

| CO₂ Emissions |

High |

Reduced by 60% |

| Mechanical Strength |

High |

Slightly lower |

| Water Usage |

High |

90% lower |

Although rPET provides environmental advantages, it may experience diminished fiber strength after many recycling processes, limiting its use in high-stress technical applications(Begum et al., 2023a).

-

(b)

Renewable Natural Fibers

Plant-based fibers generated from natural sources, like jute, hemp, flax, and kenaf, are both renewable and biodegradable. These fibers necessitate reduced pesticide and water inputs relative to cotton, rendering them environmentally superior. Animal-derived fibers like wool provide durability and biodegradability, making them appropriate for insulation and protective uses. The biodegradability, renewability, and low carbon impact of natural fibers, including jute, flax, hemp, wool, and kenaf, are contributing to their rising appeal. Recent research highlights their prospective uses in agro textiles, geotextiles, medicinal textiles, and insulating materials(Begum et al., 2023a). Jute is increasingly employed in agricultural textiles, soil erosion prevention, and thermal insulation due to its robust tensile strength and natural biodegradability. Studies indicate that jute agrotextiles can improve soil moisture retention by 35% and increase crop output by up to 185.6%(Sarkar et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Thermal Insulation Properties of Jute(Begum et al., 2023b).

Table 2.

Thermal Insulation Properties of Jute(Begum et al., 2023b).

| Material |

Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

| Jute fiber |

0.0372 – 0.0418 |

| Rock wool |

0.030 – 0.045 |

| Glass wool |

0.032 – 0.040 |

| Polyurethane |

0.025 – 0.040 |

These values underscore jute's significant potential as a sustainable alternative to synthetic insulating materials(Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022a).

-

(c)

Regenerated Cellulose Fibers

Regenerated fibers, including viscose, lyocell, and modal, are derived from cellulose sources such as wood pulp or agricultural byproducts. Contemporary manufacturing techniques—especially closed-loop systems—facilitate solvent reclamation and mitigate environmental pollution(Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022a). Regenerated fibers, although merging the advantages of natural and synthetic materials, possess an environmental profile that is significantly influenced by sustainable forestry practices, energy consumption, and chemical recovery efficiencies.

A significant constraint in the transition to sustainable fibers is the compromise in performance. Natural and recycled fibers frequently exhibit subpar performance in situations requiring high durability or sensitivity to moisture. If we don't acquire and treat certain regenerated fibers sustainably, excessive energy consumption and deforestation negate their environmental advantages. Consequently, advancements in fiber modification and composite design are imperative.

3.2. Sustainable Manufacturing Processes for Technical Textiles

Sustainable manufacturing is essential for minimizing the environmental impact of technical textiles. Traditional textile processing is resource-demanding, characterized by significant water usage, energy consumption, and chemical emissions. Innovative technologies, such as supercritical CO₂ dyeing and enzyme-based processing, provide efficient alternatives, facilitating a transition to cleaner and more sustainable manufacturing models.

3.2.1. Supercritical CO₂ Dyeing

In response to environmental concerns, the textile industry has intensified initiatives to minimize or eradicate water usage in all aspects of yarn production, dyeing, and finishing. The supercritical fluid dyeing technique possesses the capability to achieve this goal in numerous commercial textile applications globally, both presently and in the future(Montero et al., 2000).

Supercritical fluids differ from water in several important ways that can significantly impact the wet processing of textiles when used in place of water. These fluids have densities and the ability to dissolve things like liquid solvents, but they also have viscosities and diffusion coefficients like gases. These qualities make supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO₂) one of the most beneficial and eco-friendly solvents used in modern manufacturing processes. Thus, commercial textile procedures employing SC-CO₂ are anticipated to have several benefits compared to conventional aqueous approaches. The cost-effectiveness of dyeing and other textile chemical processes will improve when SC-CO₂ processing is widely used. This is because it will eliminate the need for wastewater discharges, energy consumption, drying, and air emissions. Thus, the application of SC-CO₂ is expected to make textile processing more economical and environmentally sustainable(Hendrix, 2001).

Figure 2.

Advantages of Supercritical CO2(SC-CO₂) and the disadvantages of the traditional aqueous process in technical textiles.

Figure 2.

Advantages of Supercritical CO2(SC-CO₂) and the disadvantages of the traditional aqueous process in technical textiles.

The incorporation of supercritical CO₂ (SC-CO₂) technology in technical textile processing represents a pivotal advancement in attaining sustainability within the sector(Oliveira et al., 2024). Technical textiles, essential in industries such as healthcare, defense, automotive, and filtration, necessitate sophisticated manufacturing methods that reconcile performance with environmental sustainability. The utilization of SC-CO₂ eradicates water usage, diminishes chemical waste, and decreases energy requirements, directly tackling the sustainability issues in technical textile manufacturing. SC-CO₂ technology improves efficiency, minimizes environmental impact, and guarantees the sustainability of technical textiles by substituting traditional wet processing processes in a swiftly changing market(Buckley & John, 2024). This breakthrough establishes SC-CO₂ as a groundbreaking option for addressing sustainability concerns, providing a scalable and environmentally beneficial method for the future of technical textiles.

Notwithstanding its ecological benefits, the extensive use of SC-CO₂ technology is presently constrained by substantial capital expenditure, limited fiber compatibility (predominantly polyester), and restrictions on dye solubility(Buckley & John, 2024). Ongoing research and development are required to extend its application to natural and mixed fibers.

3.2.2. Enzymatic Processing for Sustainable Technical Textiles

The textile industry may benefit from environmentally favorable processes that are facilitated by enzyme-based biotechnology(Shen & Smith, 2015). Enzymes function as a sustainable alternative to the hazardous, toxic compounds that are employed in the textile industry. Enzymes function optimally under moderate temperature and pH conditions, resulting in decreased energy consumption and, hence, lower greenhouse gas emissions. The utilization of enzymes in textile manufacturing reduces both water usage and waste generation(Roy Choudhury, 2014).

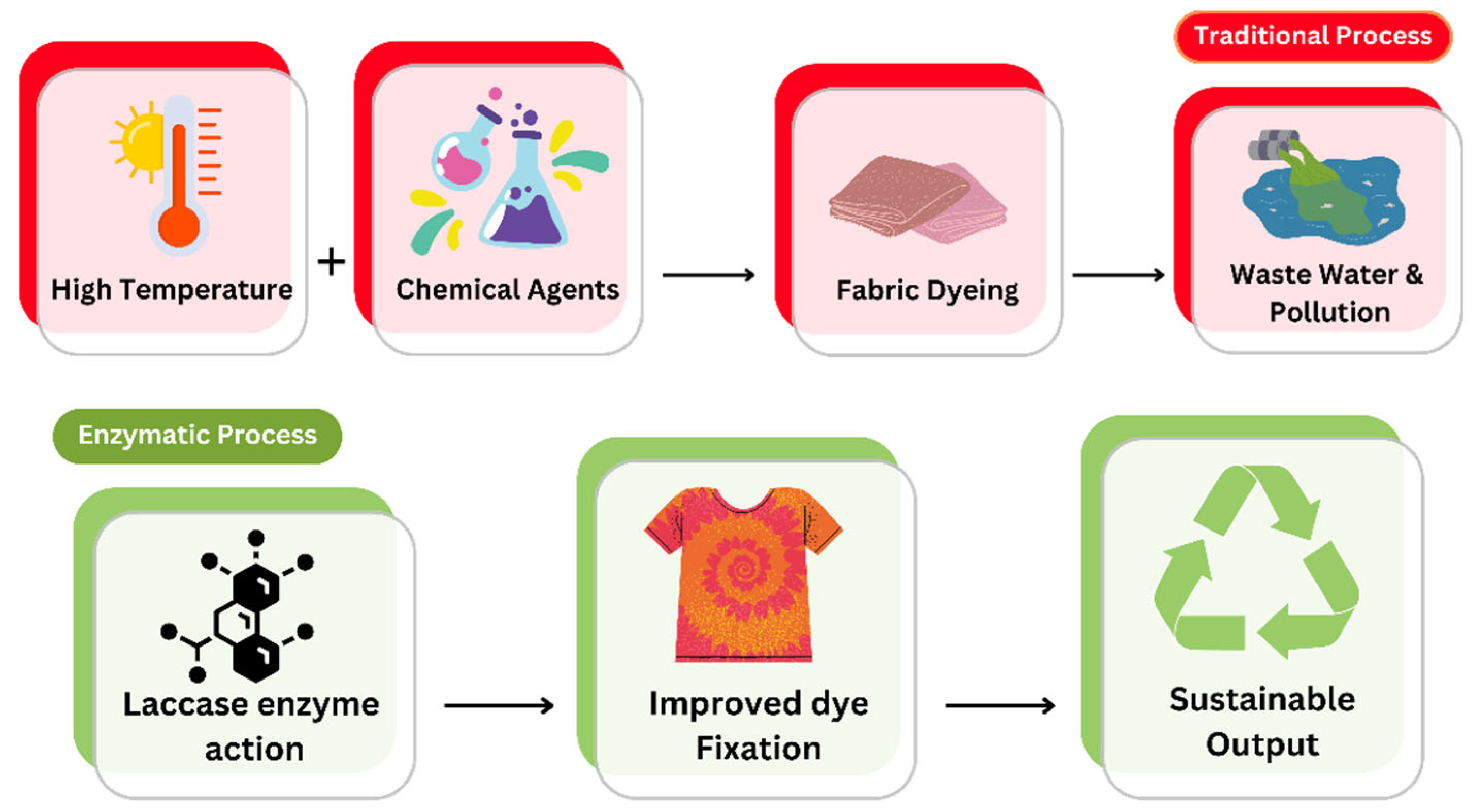

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the traditional process and the Enzymatic process.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the traditional process and the Enzymatic process.

Enzymatic processing enhances sustainability in technical fabrics in the following manner:

Hazardous halogenated substances are frequently employed in flame-retardant fabrics, which can result in environmental and health hazards. Due to their ability to impede the propagation of heat and combustion, chlorine- and bromine-based compounds are the most prevalent halogenated flame retardants(Horrocks et al., 2001). The final category of flame retardants is composed of phosphorus-based flame retardants, which are frequently combined with nitrogen compounds. During the conflagration, these substances release ammonia, which induces diffusion in the gaseous phase, and phosphoric acid, which facilitates char production(Wang et al., 2018).

There is an absolute necessity for the development of innovative and less hazardous alternative flame-retardant compounds. Natural substances, such as phytic acid and cyclodextrin, have been proven to be effective(Feng et al., 2011). Casein and hydrophobins exhibit fire-retardant potential owing to their structural phosphoserine and cysteine concentration, which releases phosphoric acid, ammonia, and sulfuric acid, capable of mitigating fire spread(Alongi et al., 2014).

Enzymatic processing facilitates the creation of environmentally sustainable, flame-retardant fabrics that preserve breathability and flexibility, rendering them suitable for fire-resistant personal protective equipment, military apparel, and aerospace applications.

Traditional polyester dyeing requires elevated temperatures (~130°C) and potent dispersing agents, which results in significant energy use and chemical contamination. The environmental and industrial safety conditions have heightened the possibility of using textile processing enzymes to guarantee eco-friendly output. The formulation of laccase enzymes has been utilized in textile processing for several applications, including biobleaching, dyeing, scouring, finishing, neps removal, printing, wash-off treatment, dye synthesis, and effluent treatment. Laccase enzymes do not impact fiber polymers, resulting in minimal fabric damage post-processing. The advancement of laccase enzymes represents a significant progression in environmentally sustainable processing(Garje, 2011).

Laccase enzymes oxidize synthetic dyes, improving dye fixing at reduced temperatures. Laccase facilitates the oxidation of phenolic chemicals in natural dyes, generating reactive radicals that enhance binding to polyester fibers, thereby securing the color of the fabric(El-Hennawi et al., 2012). Enzymatic textile processing reduces energy consumption, eliminates the necessity for harmful heavy-metal mordants by minimizing chemical usage, and improves color fastness and dye penetration.

Although enzyme therapies are very effective and environmentally benign, they exhibit substrate specificity and are frequently more costly than traditional chemical alternatives. Furthermore, storage temperatures, enzyme deactivation, and reaction durations must be meticulously regulated to guarantee reproducibility at an industrial scale.

Despite the substantial reduction of environmental impacts by supercritical CO₂ and enzymatic techniques, their adoption is constrained by economic and technological limitations. Numerous small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) lack access to these technologies, necessitating regulatory incentives or subsidies to promote their use. Additionally, further advancement is required to modify these processes for natural, mixed, and synthetic fibers beyond polyester.

3.3. Sustainable Waste Management and Recycling: Technical Textiles

The increasing need for technical textiles in industries such as healthcare, automotive, construction, and defense has intensified environmental concerns. Unlike traditional textiles, technical textiles are meticulously designed for functional characteristics, sustainability, and performance, often utilizing composite materials, specialist coatings, and synthetic fiber complexes that complicate recovery and disposal(BUCIȘCANU & PRUNEANU, 2021). The escalation of both production and consumption will significantly augment waste generated during manufacturing and post-consumption, hence requiring sustainable waste management strategies(BUCIȘCANU & PRUNEANU, 2021). Discontinuing technical weaving and incineration may lead to considerable environmental challenges, including greenhouse gas emissions from burning and micro-pollution in the ecosystem. The relentless extraction of basic materials leads to water depletion and the exhaustion of natural resources(Yasin & Sun, 2019). Effective waste management systems should focus on reducing volume, recovering materials, and ensuring environmental safety.

3.3.1. Environmental Concerns and Lifecycle Impacts

Technical textiles are specifically designed for enhanced durability and performance. Consequently, they are disposed of just when they cease to be functionally beneficial, resulting in erratic waste streams and prolonged product lifetimes. Their composite structure—typically consisting of polyester, aramid, polyamide, and coated layers—complicates mechanical or chemical separation and recycling.

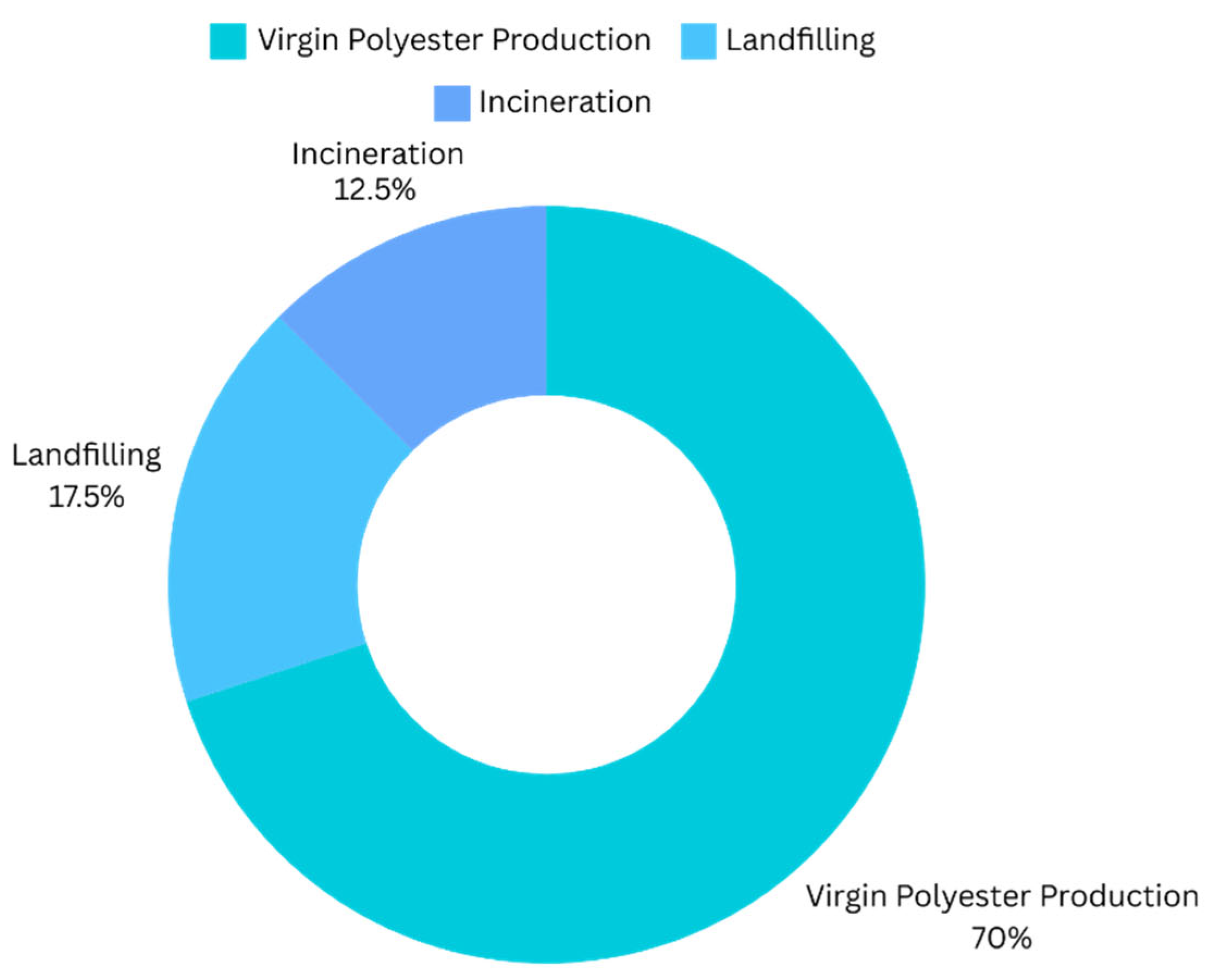

Life cycle assessment (LCA) research examining several textile fibers revealed that the production of virgin fibers emitted significantly more CO₂ equivalents per kilogram than the disposal of old fibers in landfills. The production of polyester emits 2.8 kilograms of CO₂ equivalent, while landfilling results in 700 kilograms of CO₂ equivalent(Yasin & Sun, 2019). Furthermore, the incineration of technical textiles, while effective for waste reduction and energy recovery, raises concerns due to the release of toxic compounds such as polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans.

Figure 4.

Comparing CO₂ Emissions from Different Textile Disposal Methods.

Figure 4.

Comparing CO₂ Emissions from Different Textile Disposal Methods.

3.3.2. Constraints of Existing Disposal and Recycling Techniques

Addressing sustainability in technical textiles poses numerous problems, chiefly owing to their extended lifespan and complex material composition. Unlike fashion textiles, which are frequently discarded due to shifting trends, technical textiles are generally disposed of only when they no longer serve a functional purpose, resulting in irregular availability of recyclable materials. Furthermore, their intricate composition—comprising polyester, polyamide, polypropylene, aramid, and other coatings—renders the separation and recovery of fibers challenging. The robust adhesion between the fiber and the matrix in carbon fiber-reinforced composites is particularly pronounced, which impedes recycling initiatives.

Landfilling is the predominant approach; nonetheless, it adds to methane emissions and groundwater contamination.

Incineration decreases trash volume but releases hazardous gases, particularly from flame-retardant and nanoparticle-treated fabrics (e.g., NOₓ, SO₂, and silver nanoparticle residues) (Abu-Qdais et al., 2021).

Chemical coatings and laminates utilized in personal protective equipment and protective textiles impede recyclability.

The environmental consequences of flame-retardant textiles and fabrics infused with nanoparticles are a critical concern. Wool treated with flame retardants, frequently employed in theaters, stadiums, and cinemas, degrades at high temperatures, resulting in the emission of nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) and sulfur dioxide (SO₂) into the atmosphere, thus intensifying the effects of combustion. Healthcare facilities utilize silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in antimicrobial fabrics, which present the risk of persistent contamination. After roughly ten washes, wastewater treatment systems capture almost 60% of the released silver (Limpiteeprakan et al., 2016). These facilities eliminate 90-95% of AgNPs, but they persist in the sludge and eventually end up in landfills.

3.3.3. Categories of Recycling Methods

The environmental consequences of flame-retardant textiles and fabrics infused with nanoparticles are a considerable concern. Wool treated with flame retardants, frequently employed in theaters, stadiums, and cinemas, degrades at high temperatures, resulting in the emission of nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) and sulfur dioxide (SO₂) into the atmosphere, thus intensifying the effects of combustion. Healthcare facilities utilize silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in antimicrobial fabrics, which present the risk of extended contamination. After roughly ten washes, wastewater treatment systems capture almost 60% of the released silver.

Table 3.

The following table summarizes the key differences between these methods (Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022b):.

Table 3.

The following table summarizes the key differences between these methods (Bucişcanu & Pruneanu, 2022b):.

| Recycling Method |

Effectiveness |

Cost |

Environmental Impact |

Key Benefit |

| Mechanical |

Medium |

Low |

Medium |

Retains fiber properties |

Chemical

|

High |

High |

Low |

Best for blended textiles |

Thermal

|

Low |

Medium |

High |

Convert waste to energy |

3.3.4. Transition to Circular Economy

To address these difficulties, we need to shift from a linear economy (produce–use–dispose) to a circular economy. Circular design concepts emphasize:

Design for disassembly and recyclability.

Utilization of mono-materials to facilitate separation.

Integration of modular building methodologies.

Implementation of take-back systems and eco-labeling to enhance traceability and facilitate reuse.

Eco-design principles prioritize the creation of textiles that are disassemblable, recyclable, or biodegradable. An illustration is modular textiles, designed for efficient fiber separation post-use. Notwithstanding advancements, circularity continues to be a theoretical framework in numerous technical textile industries. Technological, economic, and regulatory obstacles constrain its implementation. To amplify circular practices, we need enhanced policy frameworks, investment in recycling infrastructure, and inter-industry collaboration.

Effective waste control in technical textiles necessitates a multifaceted approach. A combination of design innovation, material simplification, and policy support is necessary to complete the cycle. Chemical recycling has potential for composite materials; yet, scalability and affordability continue to be major hurdles. A successful shift to circularity requires the backing of both technological advancements and legislative frameworks.

4. Conclusions

Technical textile production and use have a negative environmental impact; hence, sustainability strategies must be reviewed. To address consumer awareness, sustainability, and circular economy demands, technical textiles must innovate quickly and adapt to environmentally friendly modern technologies.

This review emphasizes sustainability in technical textiles, concentrating on eco-friendly raw materials, textile recycling, and advanced manufacturing methods. The study primarily concentrates on theoretical frameworks rather than experimental validation. The cost-effectiveness of sustainable textile solutions is not extensively discussed. Future research should prioritize the development of biodegradable protective textiles for industrial applications and personal protective equipment (PPE). Additionally, researchers can conduct real-world wear trials to evaluate the performance of sustainable textiles.

Sustainability in technological textiles transcends mere material concerns; it becomes a systemic challenge necessitating innovation in design, production, utilization, and disposal. Collaboration across material science, engineering, business, and politics will be crucial for scaling genuinely sustainable solutions.

References

- Abu-Qdais, H. A. , Abu-Dalo, M. A., & Hajeer, Y. Y. (2021). Impacts of Nanosilver-Based Textile Products Using a Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability, 13, 6. [CrossRef]

- Alongi, J. , Carletto, R. A., Bosco, F., Carosio, F., Di Blasio, A., Cuttica, F., Antonucci, V., Giordano, M., & Malucelli, G. (2014). Caseins and hydrophobins as novel green flame retardants for cotton fabrics. Polymer Degradation and Stability 99, 111–117.

- Avadanei, M. , Olaru, S., Ionescu, I., Ciobanu, L., Alexa, L., Luca, A., Ursache, M., Olmos, M., Aslanidis, T., & Belakova, D. (2020). ICT new tools for a sustainable textile and clothing industry. Industria Textila 71(5), 504–512.

- Begum, M. S. , Kader, A., & Milašius, R. (2023a). Flame-Retardance Functionalization of Jute and Jute-Cotton Fabrics. Polymers, 15, 11, 2563. [CrossRef]

- Begum, M. S. , Kader, A., & Milašius, R. (2023b). Flame-Retardance Functionalization of Jute and Jute-Cotton Fabrics. Polymers, 15, 11, 2563. [CrossRef]

- BUCIȘCANU, I.-I. , & PRUNEANU, M. (2021). KEY ELEMENTS OF SUSTAINABILITY IN THE FIELD OF TECHNICAL TEXTILES. [CrossRef]

- Bucişcanu, I.-I. , & Pruneanu, M. (2022a). Key Elements of Sustainability in the Field of Technical Textiles. In R. Harpa, C. Piroi, & A. Buhu (Eds.), International Symposium “Technical Textiles—Present and Future” (pp. 122–129). Sciendo. [CrossRef]

- Bucişcanu, I.-I. , & Pruneanu, M. (2022b). Key Elements of Sustainability in the Field of Technical Textiles. In International Symposium “Technical Textiles—Present and Future” (pp. 122–129). Sciendo. [CrossRef]

- Buckley, N. W., & John, A. (2024). Optimizing Supercritical ScCO2 Dyeing Conditions for Polyester-Cotton and Nylon-Wool Blends: A Sustainable Alternative to Conventional Aqueous Dyeing. Mari Papel Y Corrugado, 1, 79–88.

- Edirisinghe, L. G. L. M. , Alwis, A. A. P. de, & Wijayasundara, M. (2024). Sustainable circular practices in the textile product life cycle: A comprehensive approach to environmental impact mitigation. Environmental Challenges, 16, 100985. [CrossRef]

- El-Hennawi, H., Ahmed, K. A., & El-Thalouth, I. (2012). A novel bio-technique using laccase enzyme in textile printing to fix natural dyes. Indian Journal of Fibre and Textile Research, 37, 245–249.

- Feng, J., Su, S., & Zhu, J. (2011). An intumescent flame retardant system using β-cyclodextrin as a carbon source in polylactic acid (PLA). Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 22(7), 1115–1122.

- Garje, A. N. (2011). Green Revolution in Textile Processing by using Laccases. https://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/5480/green-revolution-in-textile-processing-by-using-laccases.

- Hendrix, W. A. (2001). Progress in Supercritical Co2Dyeing. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 31, 1, 43–56. [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, A. R., Price, D., & Price, D. (2001). Fire retardant materials. woodhead Publishing.

- Hossain, M. T., Shahid, M. A., Limon, M. G. M., Hossain, I., & Mahmud, N. (2024). Techniques, applications, and challenges in textiles for a sustainable future. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(1), 100230. [CrossRef]

- Jahana, N. , Ferdusha, J., Ahmeda, S., Himuc, H. A., & Arad, I. (2022). Sustainable Dyeing of Jute Fabric with Natural Dye Sources by Cold Pad Batch. Journal of Natural Science and Textile Technology 1, 1.

- Kumar, V. , Agrawal, T. K., Wang, L., & Chen, Y. (2017). Contribution of traceability towards attaining sustainability in the textile sector. Textiles and Clothing Sustainability, 3, 1. [CrossRef]

- Limpiteeprakan, P. , Babel, S., Lohwacharin, J., & Takizawa, S. (2016). Release of silver nanoparticles from fabrics during the course of sequential washing. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23(22), 22810–22818. [CrossRef]

- Luján-Ornelas, C. , Güereca, L. P., Franco-García, M.-L., & Heldeweg, M. (2020). A Life Cycle Thinking Approach to Analyse Sustainability in the Textile Industry: A Literature Review. Sustainability, 12, 23. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T. (2008). Advanced technical textile products. Textile Progress, 40, 3, 123–181. [CrossRef]

- Montero, G. A. , Smith, C. B., Hendrix, W. A., & Butcher, D. L. (2000). Supercritical Fluid Technology in Textile Processing: An Overview. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 39, 4806–4812. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C. R. S. de, Oliveira, P. V. de, Pellenz, L., Aguiar, C. R. L. de, & Júnior, A. H. da S. (2024). Supercritical fluid technology as a sustainable alternative method for textile dyeing: An approach on waste, energy, and CO2 emission reduction. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 140, 123–145. [CrossRef]

- Piribauer, B., & Bartl, A. (2019). Textile recycling processes, state of the art and current developments: A mini review. Waste Management & Research, 37(2), 112–119.

- Roy Choudhury, A. K. (2014). Sustainable Textile Wet Processing: Applications of Enzymes. In S. S. Muthu (Ed.), Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Eco-friendly Raw Materials, Technologies, and Processing Methods (pp. 203–238). Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. , Barui, S., Tarafdar, P. K., & De, S. K. (2018). Jute Agro Textile as a Mulching Tool for Improving Yield of Green Gram. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 7(05), 3604–3611. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. , & Smith, E. (2015). 4—Enzymatic treatments for sustainable textile processing. In R. Blackburn (Ed.), Sustainable Apparel (pp. 119–133). Woodhead Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Wu, Y., Li, Y., Shao, Q., Yan, X., Han, C., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., & Guo, Z. (2018). Flame-retardant rigid polyurethane foam with a phosphorus-nitrogen single intumescent flame retardant. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 29(1), 668–676.

- Yasin, S. , & Sun, D. (2019). Propelling textile waste to ascend the ladder of sustainability: EOL study on probing environmental parity in technical textiles. Journal of Cleaner Production, 233, 1451–1464. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).