Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We build a high-performance matmul, NeuronMM, for LLM inference on Trainium. NeuronMM is open- sourced and adds a key milestone to the Trainium eco-system

- We introduce a series of techniques customized to Trainium to reduce data movement across the software- managed memory hierarchy, maximize the utilization of SRAM and compute engines, and avoid expensive matrix transpose

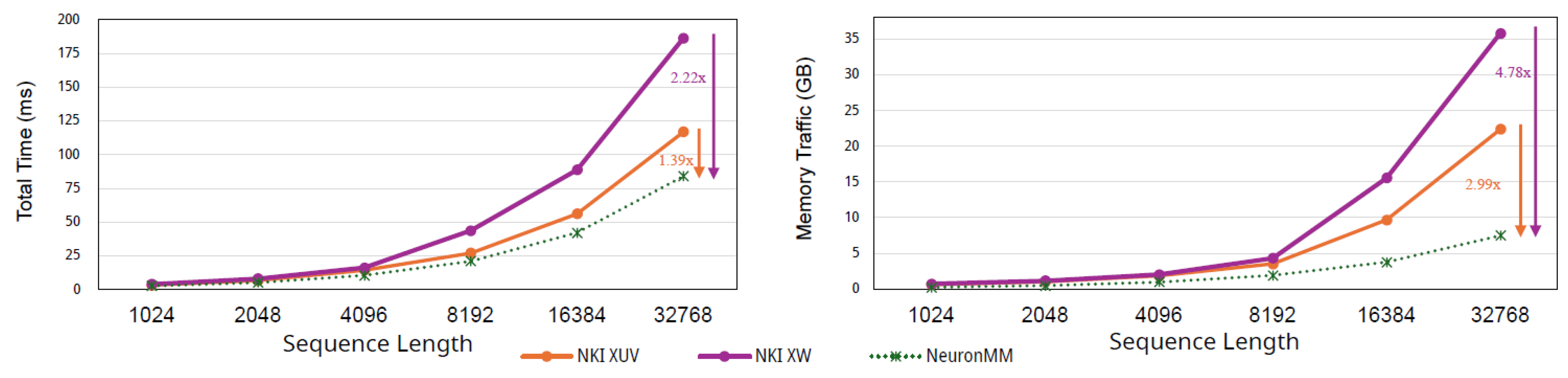

- Evaluating with nine datasets and four recent LLMs, we show that NeuronMM largely outperform the state- of–the art matmul implemented by AWS on Trainium: at the level of matmul kernel, NeuronMM achieves an average 1.35× speedup (up to 2.22×), which translates to an average 1.66× speedup (up to 2.49×) for end-to- end LLM inference

2. Background

2.1. SVD for Weight Compression

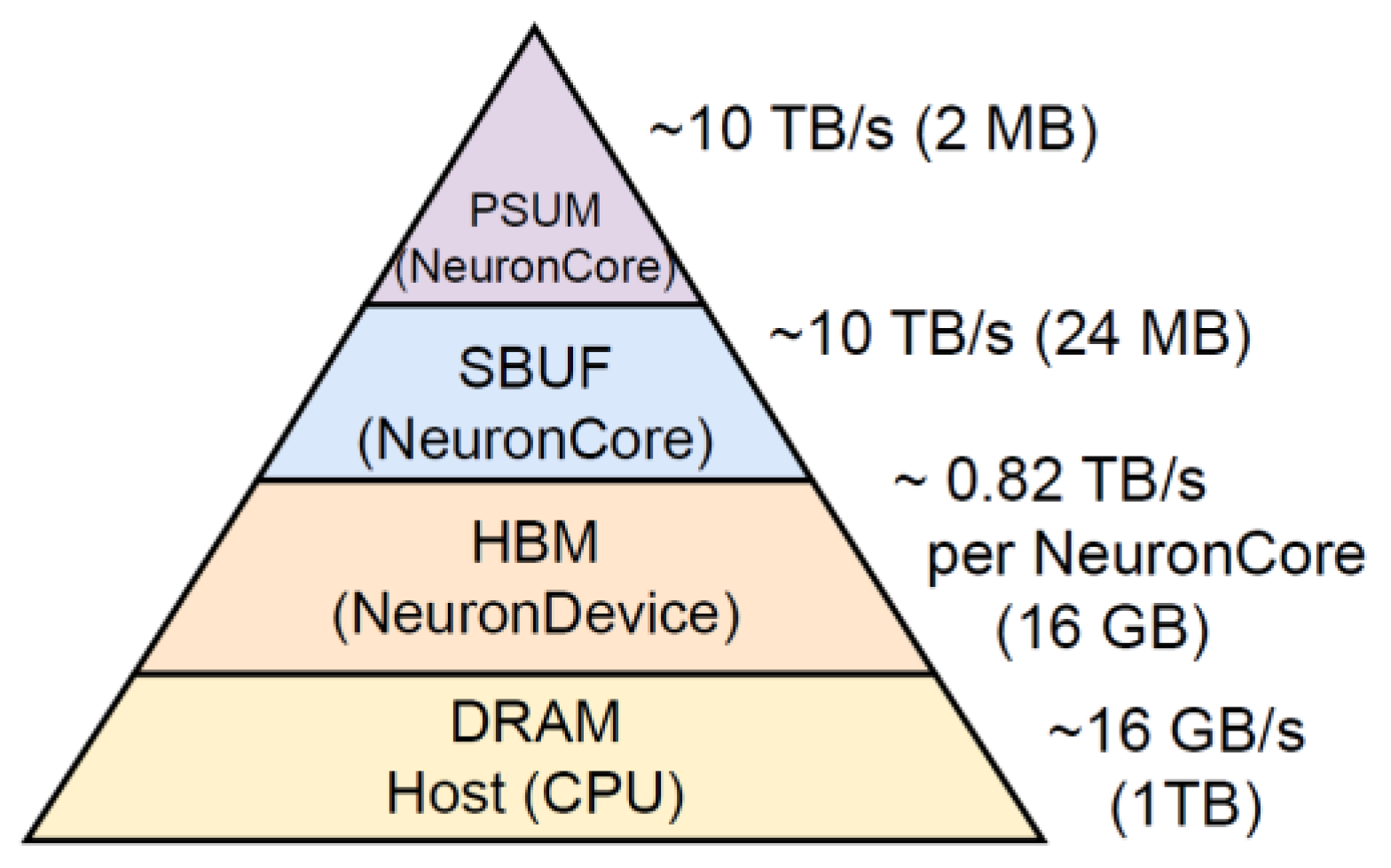

2.2. AWS Trainium

3. Motivation

3.1. Challenge 1: I/O Bottleneck

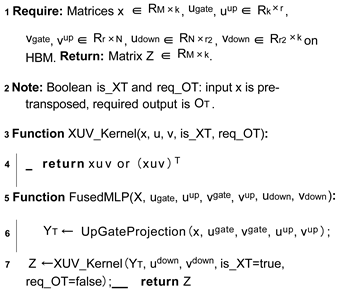

| Algorithm 1: Naive kernel fusion for Y = Xuv. |

|

3.2. Challenge 2: Recomputation

3.3. Challenge 3: Transpose Overhead

4. Design

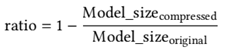

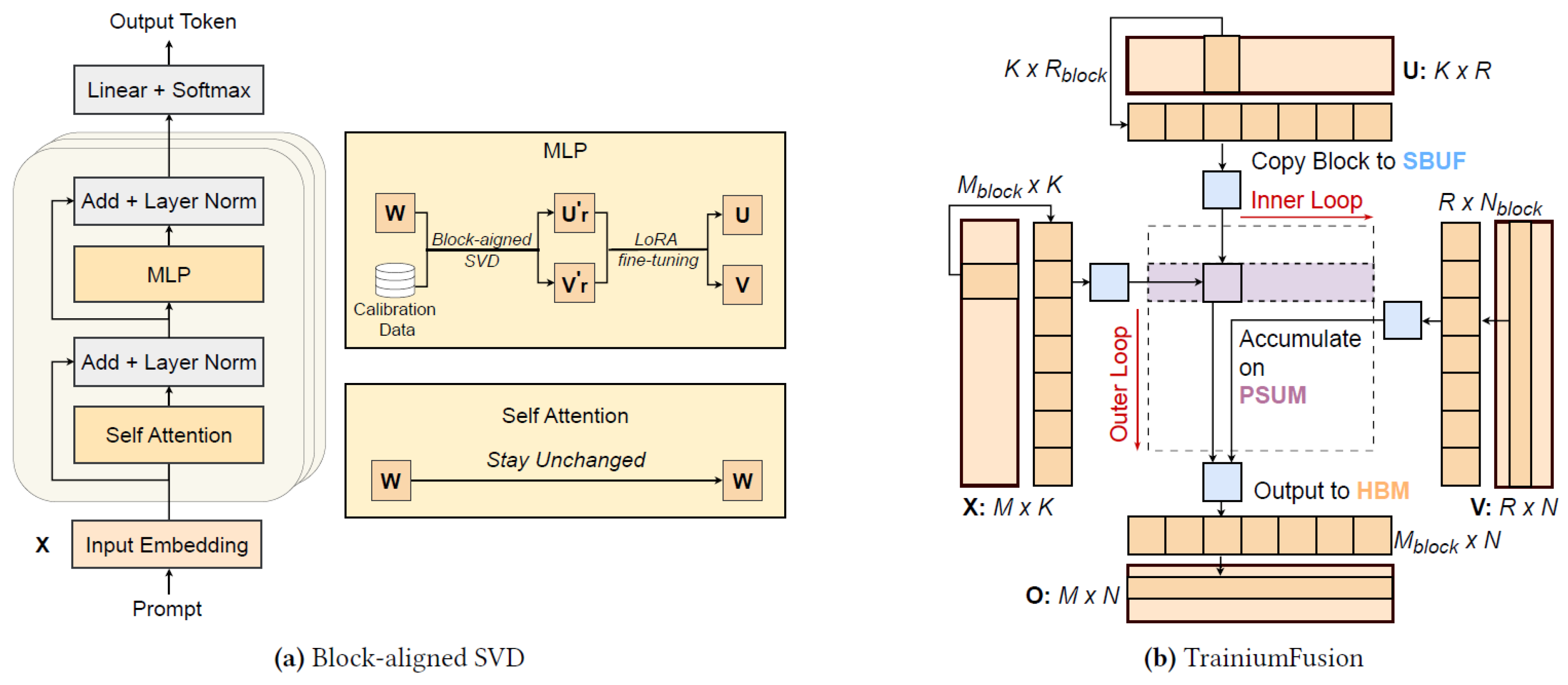

4.1. Block-Aligned SVD

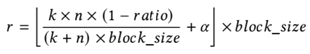

4.2. TrainiumFusion

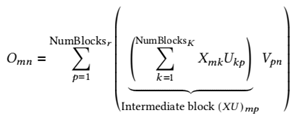

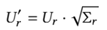

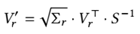

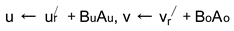

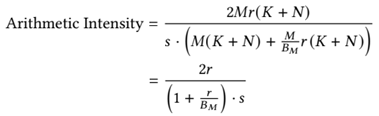

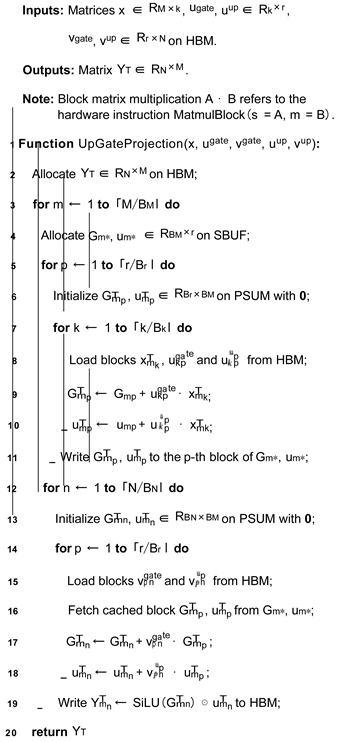

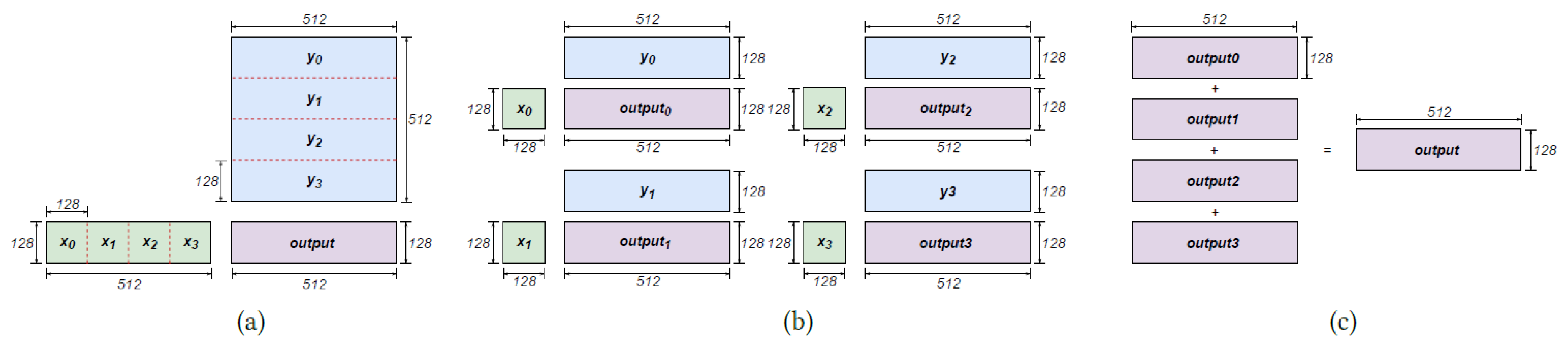

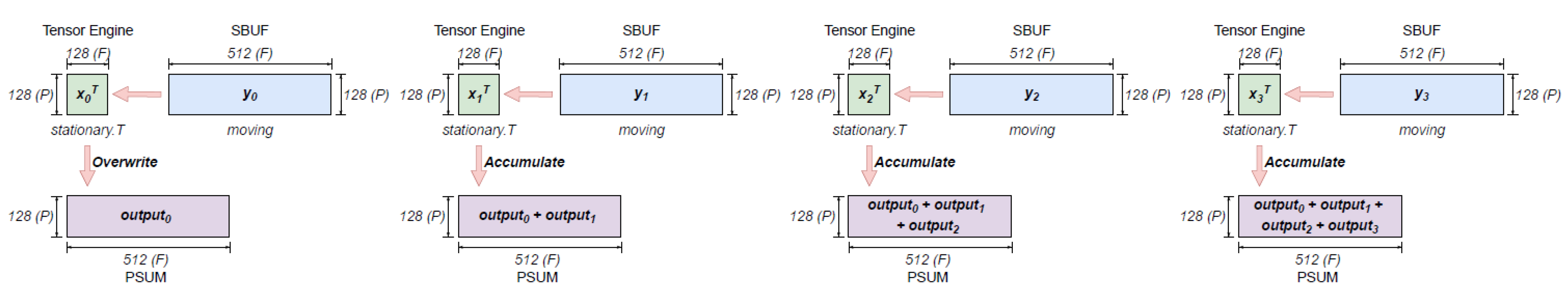

4.2.1. XUV NKI Kernel We introduce three techniques: caching, implicit transposition, and blocking, to overcome the challenges of I/O bottlenecks and recomputation. The main idea is to fuse theXuv chain into a two-stage computa- tion that executes entirely within the on-chip SBUF. First, we compute a strip of the intermediate product, using implicit transposition by reordering the inputs to the NKIMatmul primitive to directly generate its transpose, (Xu)T . This on-chip result is then immediately consumed in the second stage, where it is multiplied with a corresponding strip of v to produce a block of the final output. This fused dataflow avoids intermediate data transfer between HBM and SBUF, eliminates the recomputation penalty, and removes the inter- mediate transpose, as illustrated in Figure 5b. We give more details as follows.

, in SBUF. To do this, its inner loops load corresponding blocks of X and u from HBM. The X block is transposed in transit by the DMA engine, and the blocks are multiplied, with the result

, in SBUF. To do this, its inner loops load corresponding blocks of X and u from HBM. The X block is transposed in transit by the DMA engine, and the blocks are multiplied, with the result  accumulated in PSUM before being stored in the SBUF cache. In the second phase, another set of inner loops iterates through the blocks of matrix V, loading them from HBM and multiplying them with the pre-computed blocks fetched from the cached strip in SBUF. The final re- sult for the output block, Omn, is accumulated in PSUM and then written back to HBM.

accumulated in PSUM before being stored in the SBUF cache. In the second phase, another set of inner loops iterates through the blocks of matrix V, loading them from HBM and multiplying them with the pre-computed blocks fetched from the cached strip in SBUF. The final re- sult for the output block, Omn, is accumulated in PSUM and then written back to HBM.

= (B Mr + (BM + Br) · max(Bk, BN )) · S

4.3. Discussions

| Algorithm 2: MLP up-projection kernel |

|

| Algorithm 3: SVD-compressed MLP layer |

|

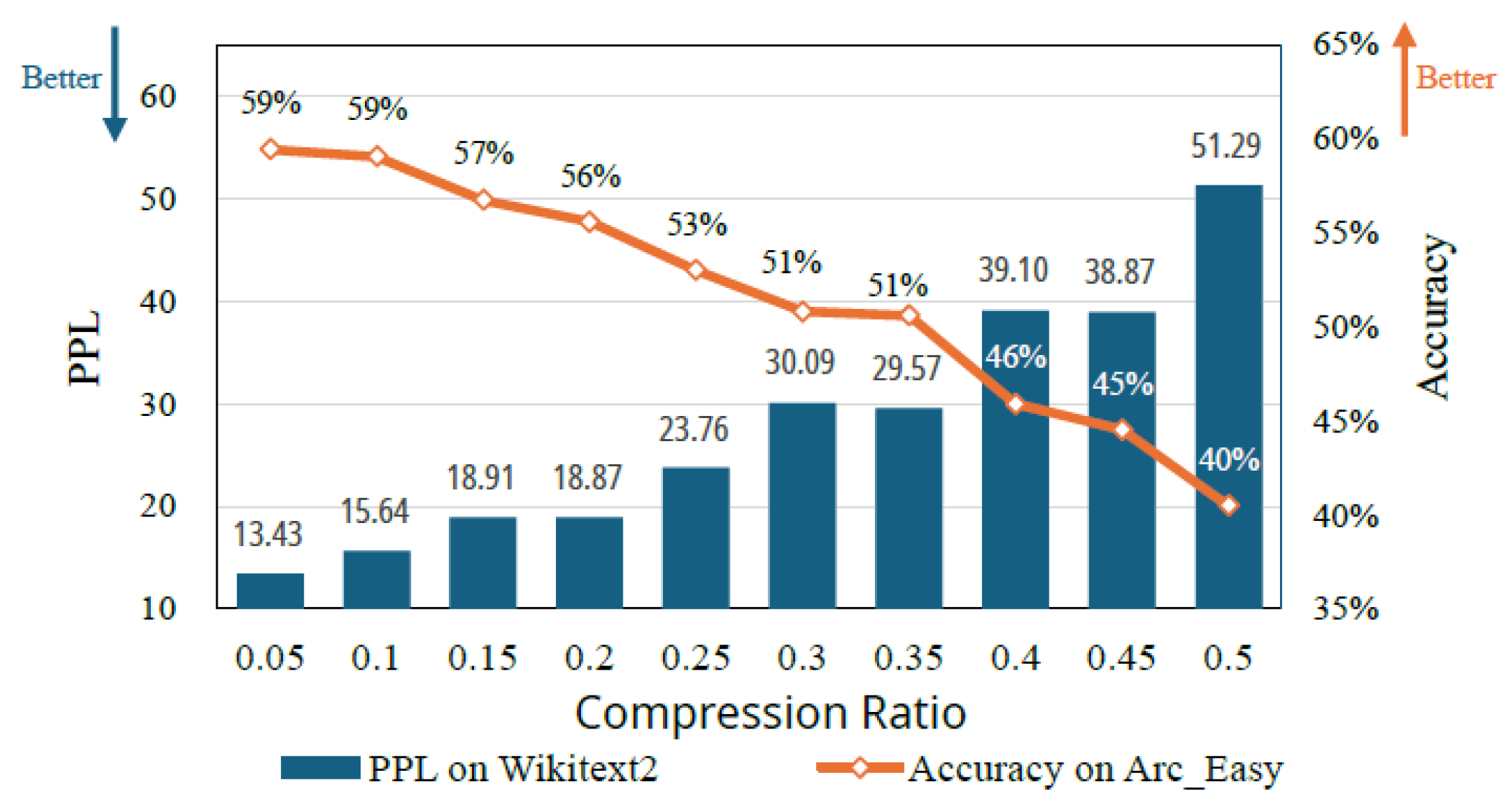

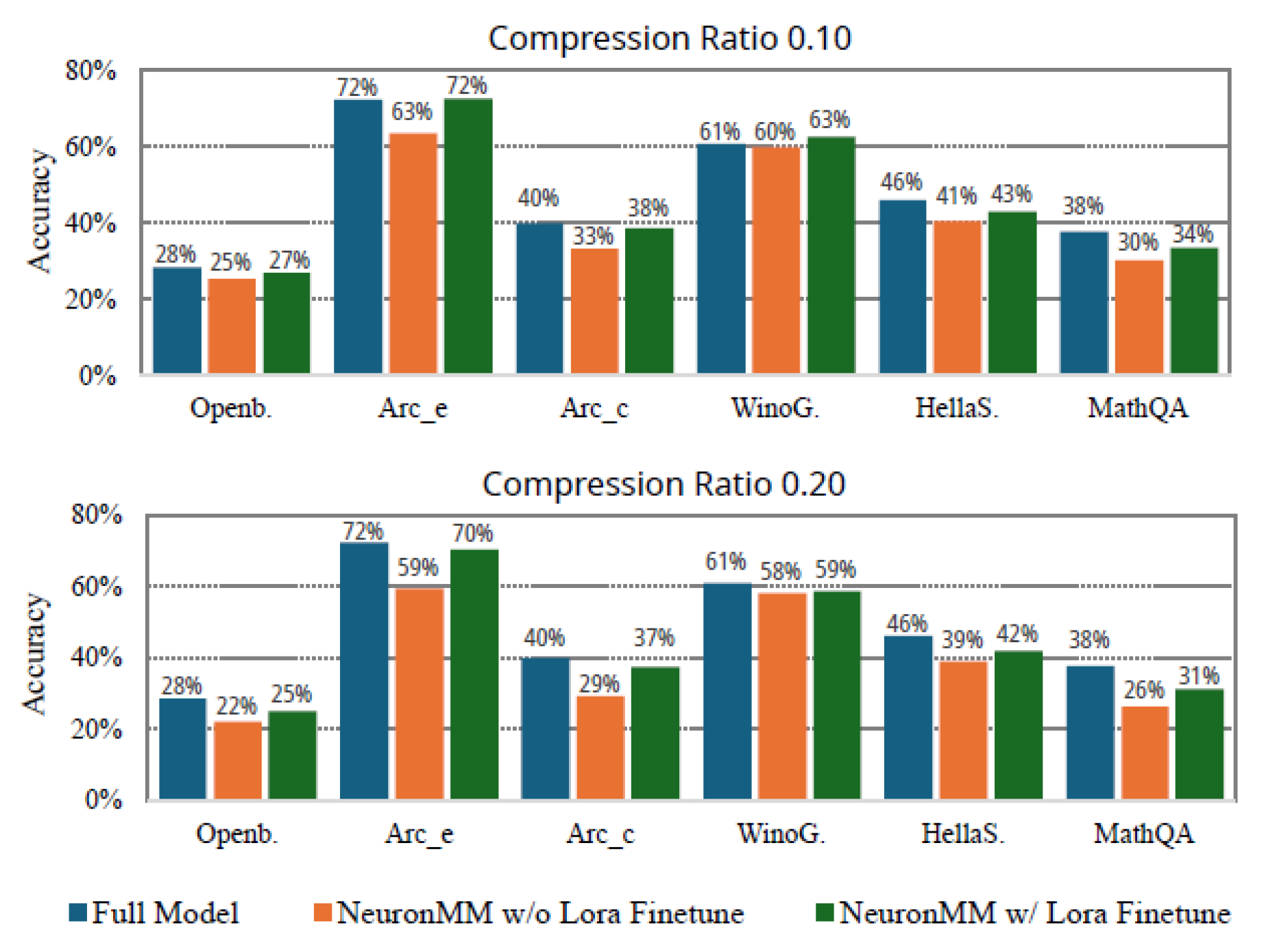

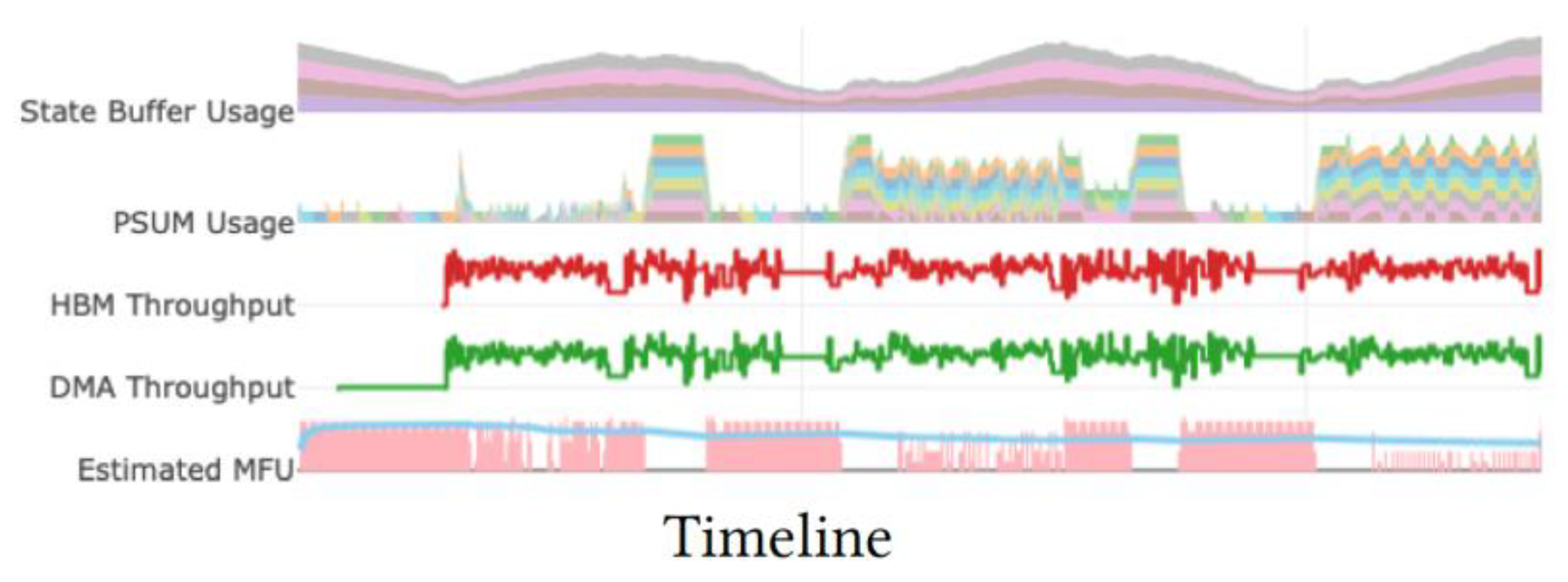

5. Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Evaluation of XUV Kernel

5.3. Impact of Block Size on Kernel Performance

5.4. Evaluation of MLP Kernel

| Model | Compr Ratio | PPL (↓) | Accuracy (↑) | mAcc (↑) | Avg. Speedup (↑) | γ (↓) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiki2 | PTB | C4 | Openb. | ARC_e | ARC_c | WinoG. | HellaS. | MathQA | |||||

| Llama-3.2-1B | 0 | 9.75 | 15.4 | 13.83 | 0.26 | 0.66 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 1.00× | - |

| 0.1 | 15.64 | 22.8 | 22.72 | 0.2 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 1.21× | 25.27% | |

| 0.2 | 18.87 | 27.24 | 26.71 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 1.63× | 11.24% | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0 | 7.82 | 11.78 | 11.29 | 0.31 | 0.74 | 0.42 | 0.7 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 1.00× | - |

| 0.1 | 11.58 | 15.61 | 17.11 | 0.24 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 1.88× | 8.66% | |

| 0.2 | 15.13 | 18.69 | 20.8 | 0.23 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.6 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 2.49× | 7.20% | |

| Qwen-3-1.7B | 0 | 16.68 | 28.88 | 22.8 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0.4 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 1.00× | - |

| 0.1 | 15.43 | 25 | 20.13 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 1.41× | 3.24% | |

| 0.2 | 17.05 | 26.97 | 22.14 | 0.25 | 0.7 | 0.37 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 1.74× | 4.72% | |

| Qwen-3-4B | 0 | 9.75 | 15.4 | 13.83 | 0.29 | 0.8 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 1.00× | - |

| 0.1 | 12.18 | 18.98 | 19.05 | 0.31 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.5 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 1.28× | 6.93% | |

| 0.2 | 14.05 | 21.09 | 21.38 | 0.3 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 1.67× | 7.41% | |

| Without SVD | Compression Ratio 0.2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Module | Size | Module | Size |

| up_proj gate_proj down_proj |

[2048, 8192] [2048, 8192] [8192, 2048] |

up_u_proj up_v_proj gate_u_proj gate_v_proj down_u_proj down_v_proj |

[2048, 1280] [1280, 8192] [2048, 1280] [1280, 8192] [8192, 1280] [1280, 2048] |

| Ratio | E2E Latency (s) | Throughput | TTFT (ms) | TPOT (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 41.22 | 49.69 | 82.22 | 39.65 |

| 0.05 | 33.76 | 60.67 | 74.18 | 32.38 |

| 0.10 | 30.45 | 67.25 | 71.41 | 29.15 |

| 0.15 | 24.90 | 82.25 | 63.07 | 23.74 |

| 0.20 | 22.14 | 92.52 | 61.20 | 20.41 |

6. Related Work

7. Conclusions

References

- Rishabh Agarwal, Nino Vieillard, Yongchao Zhou, Piotr Stanczyk, Sabela Ramos Garea, Matthieu Geist, and Olivier Bachem. On-policy distillation of language models: Learning from self-generated mistakes. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- Amazon Web Services. Aws trainium, 2023. Accessed: 2025-09-23.

- Amazon Web Services. Aws neuron introduces neuron kernel interface (nki), nxd training, and jax support for training, 2024. Accessed: 2025- 09-23.

- Saleh Ashkboos, Maximilian L. Croci, Marcelo Gennari do Nascimento, Torsten Hoefler, and James Hensman. SliceGPT: Compress large lan- guage models by deleting rows and columns. In The Twelfth Interna- tional Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- AWS Neuron SDK Documentation. NKI Matrix multiplication, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-13.

- AWS Neuron SDK Documentation. Trainium and Inferentia2 Architec- ture, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-28.

- Yueyin Bai, Hao Zhou, Keqing Zhao, Jianli Chen, Jun Yu, and Kun Wang. Transformer-opu: An fpga-based overlay processor for trans- former networks. In 2023 IEEE 31st Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), pages 221–221. IEEE, 2023.

- Steven Bart, Zepeng Wu, YE Rachmad, Yuze Hao, Lan Duo, and X. Zhang. Frontier ai safety confidence evaluate. Cambridge Open Engage, 2025.

- Jiang Bian, Helai Huang, Qianyuan Yu, and Rui Zhou. Search-to- crash: Generating safety-critical scenarios from in-depth crash data for testing autonomous vehicles. Energy, page 137174, 2025.

- Yahav Biran and Imry Kissos. Adaptive orchestration for large-scale inference on heterogeneous accelerator systems balancing cost, per- formance, and resilience, 2025.

- Yonatan Bisk, Rowan Zellers, Jianfeng Gao, Yejin Choi, et al. Piqa: Reasoning about physical commonsense in natural language. In Pro- ceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, volume 34, pages 7432–7439, 2020.

- Jie Chen, Ziyi Li, Lu Li, Jialing Wang, Wenyan Qi, Chong-Yu Xu, and Jong-Suk Kim. Evaluation of multi-satellite precipitation datasets and their error propagation in hydrological modeling in a monsoon-prone region. Remote Sensing, 12(21):3550, 2020.

- Zeming Chen, Qiyue Gao, Antoine Bosselut, Ashish Sabharwal, and Kyle Richardson. Disco: Distilling counterfactuals with large language models. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2212.10534.

- Peter Clark, Isaac Cowhey, Oren Etzioni, Tushar Khot, Ashish Sab- harwal, Carissa Schoenick, and Oyvind Tafjord. Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1803.05457.

- Joel Coburn, Chunqiang Tang, Sameer Abu Asal, Neeraj Agrawal, Raviteja Chinta, Harish Dixit, Brian Dodds, Saritha Dwarakapuram, Amin Firoozshahian, Cao Gao, et al. Meta’s second generation ai chip: Model-chip co-design and productionization experiences. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, pages 1689–1702, 2025.

- James W Demmel. Applied numerical linear algebra. SIAM, 1997.

- Tim Dettmers, Mike Lewis, Younes Belkada, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Gpt3. int8 (): 8-bit matrix multiplication for transformers at scale. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:30318–30332, 2022.

- Tim Dettmers, Mike Lewis, Sam Shleifer, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 8-bit optimizers via block-wise quantization. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2110.02861.

- Tim Dettmers, Artidoro Pagnoni, Ari Holtzman, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms, 2023.

- Xuan Ding, Rui Sun, Yunjian Zhang, Xiu Yan, Yueqi Zhou, Kaihao Huang, Suzhong Fu, Chuanlong Xie, and Yao Zhu. Dipsvd: Dual- importance protected svd for efficient llm compression. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2506.20353.

- Haozheng Fan, Hao Zhou, Guangtai Huang, Parameswaran Raman, Xinwei Fu, Gaurav Gupta, Dhananjay Ram, Yida Wang, and Jun Huan. Hlat: High-quality large language model pre-trained on aws trainium. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), pages 2100–2109. IEEE, 2024.

- Amin Firoozshahian, Joel Coburn, Roman Levenstein, Rakesh Nat- toji, Ashwin Kamath, Olivia Wu, Gurdeepak Grewal, Harish Aepala, Bhasker Jakka, Bob Dreyer, et al. Mtia: First generation silicon target- ing meta’s recommendation systems. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, pages 1–13, 2023.

- Elias Frantar and Dan Alistarh. Sparsegpt: Massive language models can be accurately pruned in one-shot. In International conference on machine learning, pages 10323–10337. PMLR, 2023.

- Elias Frantar, Saleh Ashkboos, Torsten Hoefler, and Dan Alistarh. Optq: Accurate quantization for generative pre-trained transformers. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Xinwei Fu, Zhen Zhang, Haozheng Fan, Guangtai Huang, Moham- mad El-Shabani, Randy Huang, Rahul Solanki, Fei Wu, Ron Diamant, and Yida Wang. Distributed training of large language models on aws trainium. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing, pages 961–976, 2024.

- Song Guo, Jiahang Xu, Li Lyna Zhang, and Mao Yang. Compresso: Structured pruning with collaborative prompting learns compact large language models, 2023.

- Yuze Hao. Comment on’predictions of groundwater pfas occurrence at drinking water supply depths in the united states’ by andrea k. tokranov et al., science 386, 748-755 (2024). Science, 386:748–755, 2024.

- Yuze Hao. Accelerated photocatalytic c–c coupling via interpretable deep learning: Single-crystal perovskite catalyst design using first- principles calculations. In AI for Accelerated Materials Design-ICLR 2025, 2025.

- Yuze Hao, Lan Duo, and Jinlu He. Autonomous materials synthesis laboratories: Integrating artificial intelligence with advanced robotics for accelerated discovery. ChemRxiv, 2025.

- Yuze Hao and Yueqi Wang. Quasi liquid layer-pressure asymmetrical model for the motion of of a curling rock on ice surface. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2302.11348.

- Yuze Hao and Yueqi Wang. Unveiling anomalous curling stone tra- jectories: A multi-modal deep learning approach to friction dynamics and the quasi-liquid layer, 2025.

- Yuze Hao, X Yan, Lan Duo, H Hu, and J He. Diffusion models for 3d molecular and crystal structure generation: Advancing materials discovery through equivariance, multi-property design, and synthe- sizability. 2025.

- Shwai He, Guoheng Sun, Zheyu Shen, and Ang Li. What mat- ters in transformers? not all attention is needed. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2406.15786.

- Lu Hou, Zhiqi Huang, Lifeng Shang, XinJiang, Xiao Chen, and Qun Liu. Dynabert: dynamic bert with adaptive width and depth. NIPS ’20, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020. Curran Associates Inc.

- Yen-Chang Hsu, Ting Hua, Sungen Chang, Qian Lou, Yilin Shen, and Hongxia Jin. Language model compression with weighted low-rank factorization. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2207.00112.

- Edward J Hu, Yelong Shen, Phillip Wallis, Zeyuan Allen-Zhu, Yuanzhi Li, Shean Wang, Lu Wang, Weizhu Chen, et al. Lora: Low-rank adap- tation of large language models. ICLR, 1(2):3, 2022.

- Xinyue Huang, Ziqi Lin, Fang Sun, Wenchao Zhang, Kejian Tong, and Yunbo Liu. Enhancing document-level question answering via multi-hop retrieval-augmented generation with llama 3, 2025.

- Xinyue Huang, Chen Zhao, Xiang Li, Chengwei Feng, and Wuyang Zhang. Gam-cot transformer: Hierarchical attention networks for anomaly detection in blockchain transactions. INNO-PRESS: Journal of Emerging Applied AI, 1(3), 2025.

- Yuhao Ji, Chao Fang, and Zhongfeng Wang. Beta: Binarized energy- efficient transformer accelerator at the edge. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), pages 1–5. IEEE, 2024.

- XinyuJia, Weinan Hou, Shi-Ze Cao, Wang-Ji Yan, and Costas Papadim- itriou. Analytical hierarchical bayesian modeling framework for model updating and uncertainty propagation utilizing frequency response function data. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 447:118341, 2025.

- Xinyu Jia and Costas Papadimitriou. Data features-based bayesian learning for time-domain model updating and robust predictions in structural dynamics. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 224:112197, 2025.

- XinyuJia, Omid Sedehi, Costas Papadimitriou, Lambros S Katafygiotis, and Babak Moaveni. Nonlinear model updating through a hierar- chical bayesian modeling framework. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 392:114646, 2022.

- Norm Jouppi, George Kurian, Sheng Li, Peter Ma, Rahul Nagarajan, Lifeng Nai, Nishant Patil, Suvinay Subramanian, Andy Swing, Brian Towles, et al. Tpu v4: An optically reconfigurable supercomputer for machine learning with hardware support for embeddings. In Proceedings of the 50th annual international symposium on computer architecture, pages 1–14, 2023.

- Norman PJouppi, Doe Hyun Yoon, George Kurian, Sheng Li, Nishant Patil, James Laudon, Cliff Young, and David Patterson. A domain- specific supercomputer for training deep neural networks. Communi- cations of the ACM, 63(7):67–78, 2020.

- Liunian Harold Li, Jack Hessel, Youngjae Yu, Xiang Ren, Kai-Wei Chang, and Yejin Choi. Symbolic chain-of-thought distillation: Small models can also" think" step-by-step. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2306.14050.

- Zhiteng Li, Mingyuan Xia, Jingyuan Zhang, Zheng Hui, Linghe Kong, Yulun Zhang, and Xiaokang Yang. Adasvd: Adaptive singular value de- composition for large language models. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2502.01403.

- Ziyi Li, Kaiyu Guan, Wang Zhou, Bin Peng, Zhenong Jin, Jinyun Tang, Robert F Grant, Emerson D Nafziger, Andrew J Margenot, Lowell E Gentry, et al. Assessing the impacts of pre-growing-season weather conditions on soil nitrogen dynamics and corn productivity in the us midwest. Field Crops Research, 284:108563, 2022.

- Ziyi Li, Kaiyu Guan, Wang Zhou, Bin Peng, Emerson D Nafziger, Robert F Grant, Zhenong Jin, Jinyun Tang, Andrew J Margenot, DoKy- oungLee, et al. Comparing continuous-corn and soybean-corn rotation cropping systems in the us central midwest: Trade-offs among crop yield, nutrient losses, and change in soil organic carbon. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 393:109739, 2025.

- Aixin Liu, Bei Feng, Bing Xue, Bingxuan Wang, Bochao Wu, Chengda Lu, Chenggang Zhao, Chengqi Deng, Chenyu Zhang, Chong Ruan, et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2412.19437.

- Shiwei Liu, Chen Mu, Hao Jiang, Yunzhengmao Wang, Jinshan Zhang, Feng Lin, Keji Zhou, Qi Liu, and Chixiao Chen. Hardsea: Hybrid analog- reram clustering and digital-sram in-memory computing accelerator for dynamic sparse self-attention in transformer. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems, 32(2):269–282, 2023.

- Xichang Liu, Helai Huang, Jiang Bian, Rui Zhou, Zhiyuan Wei, and Hanchu Zhou. Generating intersection pre-crash trajectories for au- tonomous driving safety testing using transformer time-series gen- erative adversarial networks. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 160:111995, 2025.

- Xinyin Ma, Gongfan Fang, and Xinchao Wang. Llm-pruner: On the structural pruning of large language models, 2023.

- MaryAnn Marcinkiewicz. Building a large annotated corpus of english: The penn treebank. Using Large Corpora, 273:31, 1994.

- Stephen Merity, Caiming Xiong, James Bradbury, and Richard Socher. Pointer sentinel mixture models. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1609.07843.

- Todor Mihaylov, Peter Clark, Tushar Khot, and Ashish Sabharwal. Can a suit of armor conduct electricity? a new dataset for open book question answering. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1809.02789.

- Roy Miles, Adrian Lopez Rodriguez, and Krystian Mikolajczyk. Infor- mation theoretic representation distillation, 2022.

- AWS Neuron. neuronx-distributed-inference, 2025. Accessed: 2025- 09-24.

- Neuron Kernel Interface. Neuron kernel interface. https://awsdocs- neuron.readthedocs-hosted.com/en/latest/general/nki/index.html, 2025. Accessed: August 1, 2025.

- Neuron Kernel Interface. Neuron kernel interface mm. https://awsdocs-neuron.readthedocs-hosted.com/en/latest/general/ nki/tutorials/matrix_multiplication.html, 2025. Accessed: August 1, 2025.

- Jiaming Pei, Jinhai Li, Zhenyu Song, Maryam Mohamed Al Dabel, Mohammed JF Alenazi, Sun Zhang, and Ali Kashif Bashir. Neuro-vae- symbolic dynamic traffic management. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2025.

- Jiaming Pei, Wenxuan Liu, Jinhai Li, Lukun Wang, and Chao Liu. A review of federated learning methods in heterogeneous scenarios. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, 70(3):5983–5999, 2024.

- Jiaming Pei, Marwan Omar, Maryam Mohamed AlDabel, Shahid Mum- taz, and Wei Liu. Federated few-shot learning with intelligent trans- portation cross-regional adaptation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2025.

- Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J Liu. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research, 21(140):1–67, 2020.

- Keisuke Sakaguchi, Ronan Le Bras, Chandra Bhagavatula, and Yejin Choi. Winogrande: An adversarial winograd schema challenge at scale. Communications of the ACM, 64(9):99–106, 2021.

- Victor Sanh, Thomas Wolf, and Alexander Rush. Movement pruning: Adaptive sparsity by fine-tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:20378–20389, 2020.

- Shikhar Tuli and Niraj K Jha. Acceltran: A sparsity-aware accelera- tor for dynamic inference with transformers. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, 42(11):4038– 4051, 2023.

- Georgios Tzanos, Christoforos Kachris, and Dimitrios Soudris. Hard- ware acceleration of transformer networks using fpgas. In 2022 Panhel- lenic Conference on Electronics & Telecommunications (PACET), pages 1–5. IEEE, 2022.

- Zhongwei Wan, Xin Wang, Che Liu, Samiul Alam, Yu Zheng, Jiachen Liu, Zhongnan Qu, Shen Yan, Yi Zhu, Quanlu Zhang, et al. Efficient large language models: A survey. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2312.03863.

- Lukun Wang, Xiaoqing Xu, and Jiaming Pei. Communication-efficient federated learning via dynamic sparsity: An adaptive pruning ratio based on weight importance. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Commu- nications and Networking, 2025.

- Qinsi Wang, Jinghan Ke, Masayoshi Tomizuka, Yiran Chen, Kurt Keutzer, and Chenfeng Xu. Dobi-svd: Differentiable svd for llm com- pression and some new perspectives. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2502.02723.

- Xin Wang, Samiul Alam, Zhongwei Wan, Hui Shen, and Mi Zhang. Svd-llm v2: Optimizing singular value truncation for large language model compression. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2503.12340.

- Xin Wang, Yu Zheng, Zhongwei Wan, and Mi Zhang. SVD-LLM: Truncation-aware singular value decomposition for large language model compression. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025.

- Samuel Williams, Andrew Waterman, and David Patterson. Roofline: an insightful visual performance model for multicore architectures. Communications of the ACM, 52(4):65–76, 2009.

- Xiaoxia Wu, Cheng Li, Reza Yazdani Aminabadi, Zhewei Yao, and Yuxiong He. Understanding int4 quantization for transformer models: Latency speedup, composability, and failure cases, 2023.

- ShuoXu, Yuchen ***, Zhongyan Wang, andYexin Tian. Fraud detection in online transactions: Toward hybrid supervised–unsupervised learn- ing pipelines. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Electronic Communication and Artificial Intelligence (ICECAI 2025), Chengdu, China, pages 20–22, 2025.

- Tengfei Xue, Xuefeng Li, Roman Smirnov, Tahir Azim, Arash Sadrieh, and Babak Pahlavan. Ninjallm: Fast, scalable and cost-effective rag using amazon sagemaker and aws trainium and inferentia2, 2024.

- Yahma. Alpaca cleaned dataset. https://huggingface.co/datasets/ yahma/alpaca-cleaned, 2023. Accessed: 2025-07-28.

- An Yang, Anfeng Li, Baosong Yang, Beichen Zhang, Binyuan Hui, Bo Zheng, Bowen Yu, Chang Gao, Chengen Huang, Chenxu Lv, et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2505.09388.

- Shuo Yang, Sujay Sanghavi, Holakou Rahmanian,Jan Bakus, and S. V. N. Vishwanathan. Toward understanding privileged features distillation in learning-to-rank, 2022.

- Zhihang Yuan, Yuzhang Shang, Yue Song, Qiang Wu, Yan Yan, and Guangyu Sun. Asvd: Activation-aware singular value decom- position for compressing large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.05821, 2023.

- Rowan Zellers, Ari Holtzman, Yonatan Bisk, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. Hellaswag: Can a machine really finish your sentence? arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.07830, 2019.

- Minjia Zhang and Yuxiong He. Accelerating training of transformer- based language models with progressive layer dropping. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:14011–14023, 2020.

- Kaiyang Zhong, Yifan Wang, Jiaming Pei, Shimeng Tang, and Zonglin Han. Super efficiency sbm-dea and neural network for performance evaluation. Information Processing & Management, 58(6):102728, 2021.

- Rui Zhou, Weihua Gui, Helai Huang, Xichang Liu, Zhiyuan Wei, and Jiang Bian. Diffcrash: Leveraging denoising diffusion probabilistic models to expand high-risk testing scenarios using in-depth crash data. Expert Systems with Applications, page 128140, 2025.

- Rui Zhou, Helai Huang, Guoqing Zhang, Hanchu Zhou, and Jiang Bian. Crash-based safety testing of autonomous vehicles: Insights from generating safety-critical scenarios based on in-depth crash data. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2025.

- Rui Zhou, Guoqing Zhang, Helai Huang, Zhiyuan Wei, Hanchu Zhou, Jieling Jin, Fangrong Chang, and Jiguang Chen. How would au- tonomous vehicles behave in real-world crash scenarios? Accident Analysis & Prevention, 202:107572, 2024.

- Xunyu Zhu, Jian Li, Yong Liu, Can Ma, and Weiping Wang. A survey on model compression for large language models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 12:1556–1577, 2024.

- J Zhuang, G Li, H Xu, J Xu, and R Tian. Text-to-city controllable 3d urban block generation with latent diffusion model. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Singapore, pages 20–26, 2024.

| Metric | Sequential Matmul | Naive Kernel fusion |

|---|---|---|

| Total Time (ms) | 1.57 | 18.06 |

| Model FLOPs (GFLOPs) | 85.90 | 343.60 |

| Memory Footprint (MB) | 298.66 | 3140.42 |

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| Matrix Operations & Dimensions | |

| W ≈ UV X ∈ RM ×k U ∈ Rk ×r , V ∈ Rr ×N M K, N r |

The weight matrix W is approximated by the product of two low-rank matrices. The input activation matrix. The low-rank matrices from SVD. The input sequence length. The hidden size and intermediate size in MLP layer of LLMs. The rank of the SVD-decomposed matrices. |

| Data Layout Hierarchy | |

| BM, Bk, Br, BN TM, TN Aij Ai∗ A ∗j |

The sizes of a block along dimensions. The sizes of a tile along dimensions. The block at the i-th row and j-th column of matrix A. The row strip composed of all blocks in the i-th row of matrix A. The column strip composed of all blocks in the j-th column of matrix A. |

| NKI XW | NKI XUV | NeuronMM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latency (ms) | 57.89 | 37.47 | 27.63 |

| Memory Traffic (GB) | 9.93 | 6.52 | 2.47 |

| Tensor Engine Active Time (%) | 78.52 | 81.28 | 99.21 |

| MFU (%) | 64.09 | 65.24 | 85.20 |

| FLOPs (TFLOPS) | 2.96 | 2.18 | 2.18 |

| Transpose FLOPs (GFLOPS) | 68.01 | 78.92 | 22.55 |

| BM | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 4096 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time (ms) | 31.25 | 16.02 | 11.02 | 10.99 | 11.07 | 12.50 |

| Arithmetic Intensity (flops/byte) | 124.12 | 240.94 | 455.10 | 819.17 | 1280.50 | 512.95 |

| SBUF Usage (%) | 19.54 | 51.69 | 80.07 | 90.05 | 96.35 | 98.96 |

| Spill Reload (MB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29.19 | 931.00 |

| Spill Save (MB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.53 | 266.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).