Introduction

Background and Rationale

Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA) is a considerable global public health problem and the most predominant nutritional disorder worldwide, affecting around 25% of the global population, with particularly high burdens among children and women of reproductive age, involving an estimated 40% of children under five years old worldwide, with the highest prevalence in low- and middle-income countries. [

1]

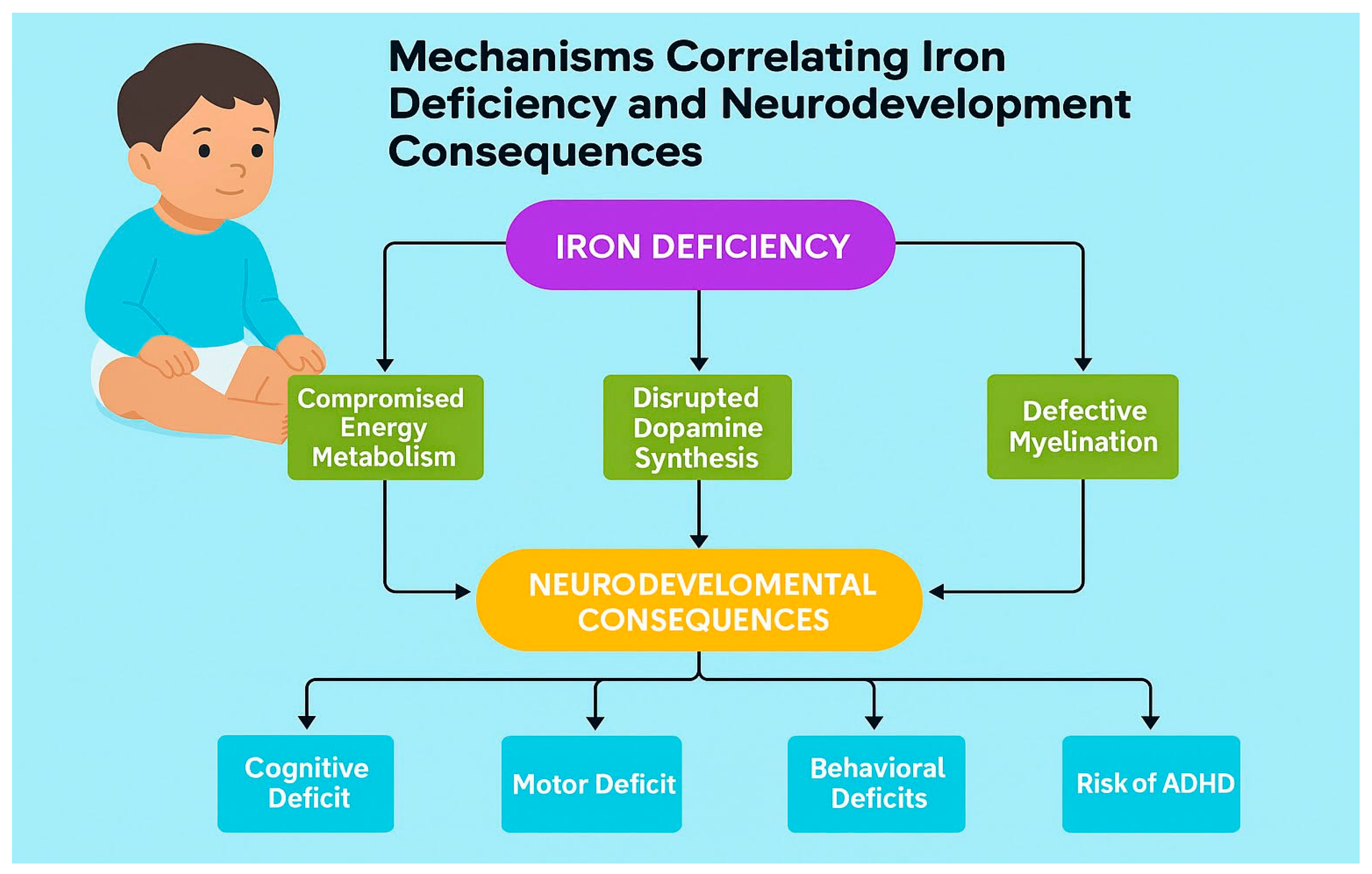

The hematological effects of IDA are well-documented; its role as a significant disruptor of neurodevelopment has garnered considerable scientific interest over recent decades. The developing brain has a high demand for iron to support essential functions, such as neurotransmitter synthesis, neuronal energy metabolism, myelination, synaptogenesis, and dopamine/GABA signaling processes that are highly active in early life. Iron deficiency during critical periods (late pregnancy, early childhood) may lead to lasting neurodevelopmental changes. Several studies of infants with IDA have shown persistent deficits into adolescence across cognitive, motor, and socioemotional domains, with neurophysiological differences noted on follow-up. [

2]

Despite extensive research, substantial challenges persist in comprehending the exact mechanisms through which IDA influences cognitive effects and how diverse confounding factors might influence these associations. [

3] This review aims to explore and revise the literature regarding the impact of IDA on cognitive and behavioral outcomes in children, evaluate the efficacy of treatment in switching these deficits, and discuss the overarching public health implications for prevention and early intervention.

Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was conducted utilizing relevant keywords, including child development, deficiency anemia, cognition, behavior, neurodevelopment, iron supplementation, and prevention across databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Medline. The inclusion criteria included clinical studies, original research, reviews, and meta-analyses focused on pediatric age groups, excluding non-English publications, conference abstracts lacking complete data, case reports, and studies unrelated to children. Titles and abstracts were assessed for relevance, with a focus on studies from the past decade and consideration of significant older works for foundational context.

Screening and Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency Anemia

Anemia is generally defined as a hemoglobin level below the 5th percentile for age and sex; commonly used cut-offs include <110 g/L for children aged 1–5 years and <115 g/L for children aged 5–12 years. Screening for iron deficiency anemia in children is targeted, focusing on high-risk populations. Key risk factors include preterm or low birth weight infants, exclusive breastfeeding beyond 4–6 months without iron supplementation, introduction of non-iron-fortified formulas or cow’s milk before 12 months, low socioeconomic status, and certain medical conditions like chronic malabsorption or inflammatory bowel disease. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends universal hemoglobin screening for all children at approximately 12 months of age, with additional selective screening for at-risk patients at later ages. [

7,

8]

The diagnosis of IDA is confirmed through a combination of complete blood count (CBC) and iron studies. The CBC in IDA usually reveals microcytic (low mean corpuscular volume, MCV) and hypochromic (low mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCH) red blood cells. A serum ferritin measurement is the most specific and cost-effective test to confirm iron deficiency, with a level below 12–15 μg/L being diagnostic in otherwise healthy children. It is crucial to note that ferritin is an acute-phase reactant; therefore, levels can be falsely elevated during concurrent infection or inflammation. In such cases, using a higher ferritin cut-off (e.g., <30–50 μg/L) or measuring additional markers, such as soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), is recommended to rule out inflammation. A reticulocyte hemoglobin equivalent (Ret-He) is an emerging, rapid parameter that reflects real-time iron availability for erythropoiesis and is not affected by inflammation, making it a valuable tool for early detection. A transferrin saturation (TSAT) of <16–20% provides further supportive evidence of depleted iron stores. A therapeutic trial of oral iron remains a valid diagnostic strategy in resource-limited settings; an increase in Hb of ≥10 g/L after 1 month of treatment is considered confirmatory for IDA. [

7,

8]

Mechanisms Correlating Iron Deficiency and Neurodevelopment

Iron is necessary for brain function and development due to diverse biological mechanisms. It works as a key cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that limits the rate of dopamine synthesis. The availability of iron has a direct impact on dopaminergic neurotransmission, a system crucial for attention, executive functions, and reward processing. [

9] Iron is also necessary for myelination of white matter tracts, with deficiency leading to defective oligodendrocyte function and reduced myelin production. Iron deficiency can also compromise brain energy metabolism because it acts as a cofactor for mitochondrial enzymes that are crucial for cellular energy production. [

10]

The developmental timing of iron deficiency is the single most critical factor demarcating the severity and permanence of its effects. The first 1,000 days of life (from conception to age 2 years) represent a crucial period of rapid brain development, characterized by intense myelination, synaptogenesis, dendritogenesis, and hippocampal structure and function, in addition to the establishment of neural networks. [

11]. Research indicates that iron deficiency during this critical window may cause irreversible damage to monoamine metabolism. [

11] During this period, the hippocampus (a structure vital for learning and memory) undergoes remarkably rapid development, making it especially vulnerable to iron insufficiency.

Recent advancements in neuroimaging techniques have started to clarify the neurobiological links associated with iron deficiency. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) and magnetic field correlation (MFC) imaging have demonstrated reduced iron content in deep brain structures, including the substantia nigra, thalamus, and basal ganglia, of children with ADHD, which is frequently associated with iron deficiency. These results imply that brain iron deficiency might disrupt dopaminergic neurotransmission in cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits, potentially justifying the high comorbidity between IDA and neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD. [

11].

Cognitive Impacts and Consequences of Iron Deficiency in Childhood

Impact on learning, memory, and attention

School performance and academic outcomes

Long-term neurocognitive consequences

The cognitive deficits associated with IDA are pervasive and observed across multiple domains. Cohort studies link infant IDA in infancy & preschool with poorer motor performance, lower IQ/mental development scores, altered affect/attention, and social-emotional difficulties that can persist despite later iron repletion. Cross-sectional and trial data show that School-age children link iron deficiency with reduced attention, processing speed, and memory; however, the effects on academic achievement are less consistent. Long-term consequences include diminished executive control (working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility) and lower educational attainment in adulthood, emphasizing the crucial role of iron in proper brain development, especially during critical early life periods (Infancy & preschool). [

12,

13]

Meta-analyses have consistently reported that children with IDA score, on average, 5 to 10 points lower on standardized examinations of cognitive and motor development compared to iron-replete peers [

14,

15]. Language development is also adversely affected, with studies documenting delays in expressive language skills and vocabulary acquisition. Learning and memory processes, particularly those dependent on the hippocampus, demonstrate significant impairment, with children demonstrating poorer performance on recognition and recall tasks. Fine motor skills, and visual-motor integration are also notably weaker, which can impact school readiness and performance [

16,

17,

18].

Behavioral and Psychosocial Consequences

In addition to its impact on cognition, IDA greatly influences a child’s emotional well-being and behavior, increasing the risk of psychiatric symptoms. A characteristic behavioral profile includes heightened wariness, fearfulness, unhappiness, and irritability. Children may display reduced social engagement and limited interaction with peers and caregiversact, hesitant and withdrawn in new situations. These behavioral patterns are thought to reflect dysregulation of the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems. Longitudinal cohort studies have found that children with chronic, severe IDA in infancy have a remarkably raised risk of being diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and exhibiting internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxiety, depression) later in childhood and adolescence. [

19,

20,

21].

Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia and Intervention Strategies

Iron supplementation (oral, parenteral)

Dietary interventions and fortification

Public health approaches (screening and prevention programs)

Treatment strategies for iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in children encompass a multifaceted approach that includes clinical, dietary, and public health interventions. It is based on oral iron supplementation, dietary modification, and careful monitoring. Oral elemental iron at 3–6 mg/kg/day remains the first-line therapy, typically administered as ferrous fumarate, sulfate, or gluconate, with daily dosing preferred; however, intermittent schedules may improve adherence. Recent evidence indicates that lower doses (< 5 mg/kg/day) can still be effective, and both short (< 3 months) and prolonged (> 6 months) treatment courses may lead to hematologic improvement, depending on the baseline hemoglobin levels. Therapy should continue for at least 3 months after normalization of hemoglobin to replenish iron stores. Dietary counseling that emphasizes iron-rich foods, limiting excessive cow’s milk intake in infants, and sufficient vitamin C intake, along with the use of fortified products, aids in recovery. For low-birth-weight and preterm infants, early enteral supplementation of 2–4 mg/kg/day is recommended. At the same time, in malaria-endemic areas, iron must be combined with malaria prevention and treatment measures. Children intolerant to or unresponsive to oral iron may require intravenous formulations, and transfusion is reserved for severe, symptomatic cases. Monitoring should include a hemoglobin response within 3–4 weeks and ferritin levels after treatment to confirm repletion of iron stores. Hematological recovery (normalization of hemoglobin and ferritin) is rapid and typically complete within 1-2 months of initiating therapy. Behavioral improvements, particularly a reduction in irritability and an improvement in attention, are often observed quickly after starting treatment; However, the reversal of cognitive deficits is frequently incomplete. While some studies show significant cognitive gains post-treatment, children rarely catch up completely to their non-anemic peers, especially in domains such as executive function and memory, as the extent of recovery is influenced by the degree of severity and chronicity of the deficiency, the timing of treatment, and the age at which it occurred. [

22,

23,

24] This partial reversibility emphasizes that treating the anemia does not automatically correlate to correcting the underlying neural insult that happened during development.

Clinical trials and cohort studies provide evidence of treatment effectiveness, with early intervention yielding better results by mitigating the cascading effects of disease progression. However, limitations exist in managing late-detected cases, as irreversible neurological changes may be too profound for full recovery, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Public health policies need to enhance these measures through large-scale fortification initiatives, community-wide supplementation programs, and targeted nutrition education campaigns and screening programs. At the same time, public awareness campaigns and prevention efforts aim to promote sustainable behavioral change and policy support, thereby reducing the global burden of iron deficiency anemia. Compliance with iron therapy is usually compromised by dose-dependent gastrointestinal side effects such as epigastric pain, nausea, and constipation, which lead many patients to intermittent dosing regimens or discontinue treatment. Parenteral iron, while adequate in severe cases, has its own risks, including immediate hypersensitivity reactions. Treatment outcomes also differ widely across populations due to differences in age, cultural practices, health status, and coexisting conditions, such as thalassemia intermedia, where standard biomarkers may fail to represent iron overload accurately. These challenges underscore the urgent need for real-world trials and culturally sensitive approaches to enhance adherence and therapeutic efficacy in diverse clinical and community settings. [

22,

23,

24]

The Critical Role of Timing of treatment and Irreversibility

The timing of iron deficiency is the single most critical factor in determining the lasting effects it can have. If treatment is delayed during periods of rapid growth and neurodevelopment, it can result in irreversible cognitive, behavioral, and motor deficits, even if hematologic levels are subsequently corrected. Early initiation of iron therapy not only restores hemoglobin and iron stores but also protects the developing brain during sensitive windows of myelination, neurotransmitter synthesis, and hippocampal development. Studies demonstrate that untreated or late-treated IDA in infancy is associated with long-term deficits in attention, school performance, and socio-emotional development that persist into adolescence and adulthood, underscoring that the neurological sequelae of iron deficiency may not be fully reversible even after iron repletion is achieved. Therefore, timely diagnosis and prompt initiation of therapy are essential to prevent lifelong impairments. [

25,

26,

27,

28]

Research gap and confounding factors

Mechanistic Insights and Brain Iron Measurement

Current diagnostic techniques for iron measurement primarily rely on blood biomarkers, including serum ferritin, hemoglobin, and transferrin saturation. However, emerging evidence suggests that these peripheral measures may not accurately reflect brain iron concentration due to the tight regulation of the blood-brain barrier and the unique iron homeostasis mechanisms in neural tissues, and a considerable disconnect remains between peripheral iron measures and brain iron status. For instance, iron regulatory protein two expression is higher in neural tissues compared to the periphery, suggesting independent regulation. [

29] This gap underlines the urgent need for non-invasive neuroimaging techniques that can precisely quantify brain iron concentration. Quantitative susceptibility mapping and Magnetic field correlation imaging show promise; however, there is limitations in their clinical application remain. Prospective research should focus on validating these imaging biomarkers against post-mortem brain iron measurements and developing standardized protocols for assessing brain iron status in pediatric populations. Additionally, more studies are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms regulating brain iron homeostasis and how these processes are disrupted in iron deficiency states. [

29]

Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

The longitudinal course of neurodevelopmental impairments following iron deficiency remains poorly described. Various studies have documented cognitive deficits in iron-deficient children; however, most have limited follow-up periods, leaving queries about the persistence of these impacts into adolescence and adulthood.

a recent systematic review by Morandini et al. (2025) noted that only 17 cohort studies have examined long-term outcomes, with just 14 being of high quality, furthermore, existing studies have neglected specific cognitive domains that might be particularly sensitive to iron deficiency and focused primarily on global cognitive measures such as IQ scores, while Future studies should employ comprehensive neuropsychological batteries assessing specific cognitive domains and continue tracking participants into adulthood to determine whether early iron deficiency increases risk for neurodegenerative conditions later in life. [

29]

Heterogeneity in Supplementation Response

Recent research has revealed a puzzling finding: the responsiveness to iron supplementation varies among different populations and individuals. Well-designed randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that iron supplementation has minimal effects on the psychomotor development of infants, regardless of whether they belong to populations at high or low risk of iron deficiency. [

30]

This heterogeneity suggests the presence of effect modifiers that influence individual response to iron supplementation. Possible modifiers include genetic factors affecting iron metabolism, baseline iron status, the timing of supplementation comparable to critical developmental windows, and comorbid nutritional deficiencies. Future research should utilize accurate approaches to recognize genetic, nutritional, and metabolic factors that predict response to iron supplementation, fostering more targeted and effective interventions. [

30]

Future Directions

Need for early detection and preventive strategies

Role of multi-nutrient interventions

Research gaps and potential innovations

Preventive approaches are moving toward food-based strategies, including fortification and recipe development to improve iron bioavailability, as well as blended interventions that integrate supplementation and nutrition education within existing programs, such as Integrated Child Development Services. Additionally, addressing root causes, such as parasitic infections, through integrated control programs is also crucial. Recognizing that IDA often coexists with other micronutrient deficiencies, future efforts should prioritize multi-nutrient interventions that leverage synergistic effects, such as vitamin C enhancing iron absorption. Interpretation of diagnostic factors, including inflammatory and genetic components, is crucial to strengthening outcomes. Bridging research with implementation by promoting behavioral change and conducting rigorous field evaluations, as well as fostering culturally sensitive communication and partnerships, will be key to achieving a sustainable, population-wide impact. [32]

Limitations

It is essential to admit that this narrative review has several limitations. These possess the limitations of an evidence-based synthesis, including dependence on published literature, which could present publication bias, and the risk of missing applicable studies despite a wide search strategy.

Conclusion

Iron Deficiency Anemia in early childhood is a neurodevelopmental disorder with potentially lifelong impacts. The deficits in cognition, school achievement, and behavior place a significant burden on families, individuals, and healthcare systems. Given the limited ability of treatment to fully restore developmental potential, the focus must shift decisively to prevention. Public health strategies are the most effective and cost-efficient solution. These include:

Advancing maternal iron status during pregnancy and endorsing delayed umbilical cord clamping.

Securing adequate iron intake for infants through supplementation (e.g., 1 mg/kg/day for exclusively breastfed infants from 4 months of age) and the timely introduction of iron-rich complementary foodstuffs.

Enforce universal screening for anemia at around one year of age.

Sustaining nutritional education programs for communities and families.

Future studies should resume investigating the specific neural mechanisms affected by IDA and explore more potent nutritional and psychosocial intervention approaches to improve recovery in children affected by this condition.

References

- Djokic B, Mijatović Jovin V, Živanović N, Minaković I, Gvozdenović N, Dickov Kokeza I, et al. Iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia: a comprehensive overview of established and emerging concepts. *Pharmaceuticals*. 2025;18(8):1104. [CrossRef]

- Somashekar A, Mahansaria OP, Agarwal NK, Venkata RA, Hazra S, Bhasin S, et al. Iron deficiency anemia in infancy—pediatric expert opinions and path forward in Indian context. *J Pediatr Perinatol Child Health*. 2025;9(2):e020. [CrossRef]

- Smith J, Lee A, Kumar R. Unlocking iron: nutritional origins, metabolic pathways, and systemic significance. *Front Nutr*. 2025;12:1637316.

- Hurrell R, Egli I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. *Am J Clin Nutr*. 2023;117(6):1237–43. [CrossRef]

- European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Working Group on Pediatric Iron Deficiency. A novel algorithm for the differential diagnosis of microcytic anemia in children: integrating reticulocyte hemoglobin and soluble transferrin receptor. *J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr*. 2025;80(4):521–8.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). *Iron deficiency anaemia in under 16s: diagnosis and management* [NICE Guideline NG78, 2025 update]. London: NICE; 2025.

- Morandini P, Rossi F, Yildiz Y, Demirci S. Brain iron concentration in childhood ADHD: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. *J Affect Disord*. 2025;368:145–53.

- Appiah PK, Sarfo JO, Osei-Asibey A, Agyei FK, Asare-Doku W, Adomako I, et al. Iron deficiency anemia and its association with cognitive function among adolescents in the Ashanti Region, Ghana. *BMC Public Health*. 2024;24:1472.

- Morandini P, Yildiz Y, Aydin O, Demirci S, Balkan S. Neurodevelopmental impairments as long-term effects of early-life iron deficiency. *Balkan Med J*. 2025;42(2):123–9.

- Gingoyon A, Borkhoff CM, Koroshegyi C, Mamak E, Birken CS, Maguire JL, et al. Chronic iron deficiency and cognitive function in early childhood. *Pediatrics*. 2022;150(6):e2021055926. [CrossRef]

- Gutema BT, Sorrie MB, Megersa ND, Yesera GE, Yeshitila YG, Pauwels NS, et al. Effects of iron supplementation on cognitive development in school-age children: systematic review and meta-analysis. *PLoS One*. 2023;18(6):e0287703. [CrossRef]

- Sachdev H, Gera T, Nestel P. Effect of iron supplementation on mental and motor development in children: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. *Public Health Nutr*. 2005;8(2):117–32. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, et al. The effect of iron supplementation on motor development and cognitive function in children under 3 years of age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. *Nutrients*. 2019;11(8):1799.

- Lozoff B, et al. Poorer behavioral and developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for iron deficiency in infancy. *Pediatrics*. 2000;105(4):E51. [CrossRef]

- Congdon EL, et al. Iron deficiency in infancy is associated with altered neural correlates of recognition memory at 10 years. *J Pediatr*. 2012;160(6):1027–33. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Barroso RM, et al. Iron supplementation and iron status in infants: a randomized controlled trial. *J Pediatr*. 2008;152(3):382–7.

- Carter RC, et al. Iron deficiency anemia and cognitive function in infancy. *Pediatrics*. 2010;126(2):e427–34. [CrossRef]

- Lozoff B, et al. Dose–response relationships between iron deficiency with or without anemia and infant social-emotional behavior. *J Pediatr*. 2008;152(5):696–702. [CrossRef]

- Wiegersma AM, et al. Association of prenatal and infant exposure to iron-deficiency anemia with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. *JAMA Pediatr*. 2019;173(7):1–9.

- Rehman S, Maqbool H, Aslam B, Khan H. Optimal dose and duration of iron supplementation for treating iron-deficiency anemia in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. *Nutrients*. 2025;17(3):513.

- World Health Organization (WHO). *Daily iron supplementation in infants and children: guideline.* Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- Radziewicz-Winnicki I, Szenborn L, Weker H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in children and adolescents: recommendations of the Polish Pediatric Society. *Front Pediatr*. 2023;11:1185132.

- Lozoff B, Smith JB, Clark KM, Perales CG, Rivera F. Home intervention improves cognitive and social-emotional scores in iron-deficient anemic infants. *J Nutr*. 2021;151(5):1326–34. [CrossRef]

- Beard JL, Lozoff B. Long-term functional consequences of iron deficiency in childhood. *Nutr Rev*. 2022;80(8):748–60.

- Algarín C, Peirano P, Garrido M, Pizarro F, Lozoff B. Iron-deficiency anemia in infancy: long-lasting effects on auditory and visual system functioning. *Front Hum Neurosci*. 2023;17:1123897. [CrossRef]

- East P, et al. Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive and educational outcomes in young adulthood. *Dev Psychol*. 2018;54(11):2112–25. [CrossRef]

- Morandini HAE, et al. Brain iron concentration in childhood ADHD: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. *J Psychiatr Res*. 2024;173:200–9. [CrossRef]

- Theola J, Andriastuti M. Neurodevelopmental impairments as long-term effects of iron deficiency in early childhood: a systematic review. *Balkan Med J*. 2025;42(2):108–20. [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska A, Domellöf M. Iron deficiency in infants and children – current research challenges. *Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care*. 2025;28(3):284–8. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein JL, Fothergill A, Hackl LS, Haas JD, Mehta S. Iron biofortification interventions to improve iron status and functional outcomes. *Proc Nutr Soc*. 2019;78(2):197–207.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).