1. Introduction

The 1969 paper by Strassen [

1] showed that matrix multiplication can be done with a sub-cubic complexity. More recent algorithms such as the Method of Four Russians and the Strassen-Winograd multiplication as well as various low-level strategies such as the bit-level parallelization for multiplying dense binary matrices can be found in [

2]. The Schur complement is often a basis for blockwise recursive methods to invert large real-valued matrices [

3]. For base cases of the recursive methods, say, the matrices of sizes five or less, it is more efficient to use the direct Gauss-Jordan elimination (GJE) [

4]. The caveat is that the submatrices created during the recursion must themselves be invertible. Unfortunately, for the matrices defined over finite Galois fields, this cannot be guaranteed, and it is also the key reason why the recursion often fails in practice.

In some applications, it is useful to explore the high-throughput strategies for enumerating the invertible matrices of a given size. The invertible matrices of size

over a Galois field,

q, form the general linear group

[

5]. The GL group can be ordered using a Grey encoding, so that any two subsequent matrices are related by simple operations on rows [

6]. The underlying group structure can be studied using the corresponding Cayley graphs.

The current literature contains mainly the results on optimizing the primitives in matrix multiplications, and also provides deep theoretical insights into the structure of the groups. However, to our best knowledge, there are presently no investigations how to efficiently invert very large matrices over finite fields, and the related problems. In particular, it is sometimes sufficient to only detect when such a matrix is singular. In other cases, it may be necessary to also find the closest matrix that is invertible. Moreover, any recursive algorithm for inverting the matrices over finite fields needs to address the issue of submatrices being singular.

This paper fills the gap in the literature by reporting a robust and fast algorithm for inverting very large binary matrices. It is based on the pivoted PLU factorization [

4]. On the other hand, the efficient enumeration of all invertible matrices in the

group is achieved by the Bruhat decomposition [

7]. In addition, a method for finding an invertible matrix that is closest to a given binary singular matrix is devised. This method determines the positions of the minimum number of bit-flips to make the matrix non-singular. The developed algorithms are implemented in C++, and they are available from the Github repository [

8]. All implemented algorithms were validated. Even though the focus in this paper is on binary matrices, the proposed methods are also effective for the matrices defined over other finite fields by updating the arithmetic operations to these fields.

This paper is organized as follows. The rest of this section summarizes the terminology and notations, which are important in understating the paper.

Section 2 introduces a robust blockwise matrix inversion algorithm based on the PLU factorization. The algorithm for efficiently enumerating elements of general linear groups is presented in

Section 3. It is based on the Bruhat group decomposition. An algorithm for repairing singular binary matrices to make them invertible by performing the minimum number of bit-flips is proposed in

Section 4. The paper is concluded in

Section 5. The examples illustrating the proposed algorithms are provided in Appendix A and B.

1.1. Preliminaries and Notations

The Galois field, , is a ring, , with addition denoted by symbol, ⊕, and multiplication denoted by symbol, ∧. Additions over can be effectively performed using logical exclusive-or (XOR), whereas multiplications are equivalent to logical AND. Note also that, in , the addition and subtraction are equivalent.

The matrices are denoted by bold capital letters. The symbol, , represents the i-th row and the j-th column element of the matrix, . A bit-flip at position, , is defined as, . The identity matrix is denoted by .

The permutation matrix, , is created from the identity matrix, , by permuting its row and/or columns. There are (n factorial) unique permutation matrices. The permutation matrices are orthogonal, i.e., .

A unit lower-triangular binary matrix, , have all diagonal entries equal to 1, while all the entries above the main diagonal are 0. Similarly, a upper-triangular binary matrix, , have all diagonal entries equal to 1, and all the entries below the main diagonal are 0.

The rank of matrix, , is the maximum number of linearly independent rows (or, equivalently, columns). The matrix has full rank, if . The square matrix is invertible, i.e., its inverse, , exists, if and only if, it has full rank; otherwise it is said to be singular. The singular matrix has the rank deficiency, . The rank deficiency represents how many linearly independent rows or columns are missing to have a full span of the n-dimensional vector space.

A general linear group

is the set of all invertible

binary matrices that is closed under matrix multiplication. The unit element of the group is the identity matrix,

. The group has order (i.e., the cardinality),

The

,

n is even, matrix can be partitioned into four equal-size submatrices (i.e., blocks) as,

Provided that is invertible, its Schur complement is defined as, .

2. Accelerated Inversion of Binary Matrices

The objective is to devise a fast algorithm for the robust inversion of very large binary matrices. The proposed algorithm relies on the following crucial techniques. The pivoted PLU factorization enables the proper factorization of any invertible matrix. Importantly, it avoids the fundamental limitation of simpler blockwise inversion methods that often fails at singular submatrices for matrices defined over finite fields. The recursive blockwise inversion can be further optimized for speed by considering the sub-cubic Strassen’s algorithm for matrix multiplication in order to improve the asymptotic time complexity.

For smaller matrices, the recursion overhead exceeds the complexity of the direct GJE. The GJE assumes the augmented matrix, , and performs the row operations until it arrives at the matrix, . In , it only involves the row swaps and XORing the rows. If the matrix is found to be singular, i.e., there is no pivot for a given matrix column, the algorithm correctly reports a failure. The cubic time complexity of the GJE is acceptable for smaller matrices.

For larger matrices, other algorithm strategies such as divide-and-conquer and dynamic programming are required. These strategies provide much better control over the time complexity as the problem size increases. In this paper, we first consider a standard blockwise recursive inversion with the Schur complement to show that it is fundamentally flawed when considering matrices over finite fields. This will motivate much more robust block-recursive inversion method that is based on the PLU factorization. Recall also that, in this paper, only the binary matrices are considered; generalizing the methods to other finite fields should be straightforward by modifying the underlying arithmetic operations.

The standard blockwise inversion of matrices assumes the Schur complement to reduce the

problem into the four sub-problems, each of size

. In particular, assuming that both

and its Schur complement

are non-singular, the inverse

is computed recursively using its Schur complement. The Schur complement requires two matrix multiplications, and its inverse,

, is again computed recursively. The inverse matrix is then constructed as,

where

Computing the matrices in (

4) requires six matrix multiplications.

Furthermore, in order to improve the asymptotic time complexity of the standard matrix blockwise inversion, the six required matrix multiplications can be efficiently performed using the Strassen’s technique, which has a sub-cubic time complexity. Subsequently, only seven rather than eight matrix multiplications are required in computing each sub-problem in the divide-and-conquer matrix inversion method described above; the asymptotic time complexity is then reduced from to . However, and importantly, for and other finite fields, the submatrices, , and, , frequently become singular, which terminates the algorithm, even though the original matrix, , is non-singular. The solution is to combine the Schur complement with the PLU factorization in performing the blockwise matrix inversion as will be described next. We also prove the correctness of this algorithm, and analyze its time complexity.

2.1. Block-Wise Inversion with PLU Factorization

The PLU matrix factorization can be used to achieve a fast matrix inversion as originally proposed in [

9]. Specifically, the PLU factorization theorem asserts that, for any non-singular matrix,

, there exists a permutation matrix

such that

, where

and

are the unit lower-triangular and and upper-triangular matrices, respectively, representing the LU factorization [

4]. The key idea is to first recursively compute the PLU factorization of the matrix,

, to facilitate its fast inversion, since inverting a triangular matrix amounts to solving a set of linear equations being already in the reduced row echelon form [

4].

In particular, the first step is to recursively compute the PLU factorization of the submatrix,

. Thus, provided that,

, then the inverse,

, is straightforward to obtain. The Schur complement can be inverted similarly using its PLU factorization,

. The inverse matrix,

, is then obtain using the structure (

3) and (

4). Most importantly, the PLU matrix factorization is guaranteed to always yield the correct result for all non-singular binary matrices,

.

The matrix bisection that is performed repeatedly at each recursive step of the blockwise matrix inversion and the Strassen’s multiplication implicitly assume that the original matrix,

, has the size,

, for some integer,

. Even though the power of two size cannot be guaranteed, the original matrix can be always padded with zeros to such a size, i.e.,

where

, and

is the ceiling function. The inverse of the

matrix,

, can be then written as,

Once the complete factorization,

, is obtained, the matrix inverse is computed as,

2.2. Complexity and Correctness of Matrix Inversion via PLU

Factorization

Lemma 1 (Correctness of the PLU-based matrix inversion). The non-singular matrices over finite Galois fields can be correctly inverted using the PLU factorization with blockwise matrix decomposition. Moreover, the singular matrices are always correctly detected, and the algorithm terminates.

(Proof outline) The GJE, which is adopted for inverting the base cases, is guaranteed to find the inverse, or to correctly detect that the submatrix is singular. The PLU factorization theorem guarantees that any non-singular matrix,

, can be factored as,

,

4]. Importantly, the submatrices,

, and the Schur complements,

, at each step of the blockwise recursion are always invertible by the PLU factorization theorem. Hence, the PLU factorization,

, can be always correctly obtained by properly combining the submatrices,

. The unit triangular matrices are always invertible [

4]. Consequently, the non-singular matrix,

, can be inverted as,

. Moreover, the singular matrix is always detected when inverting the base case submatrices as the GJE fails to find all pivots. □

It should be noted that Lemma 1, and its proof are independent of the specific field. Thus, Lemma 1 is valid for the matrices defined over all finite fields, and even infinite fields including real numbers.

Theorem 1 (Complexity of blockwise matrix inversion with PLU factorization). The blockwise recursive inversion of matrices with the PLU factorization and Strassen’s matrix multiplication has the complexity, .

Proof. Let

be the time to invert a

matrix, and

be the time to multiply two

matrices. The complexity is dominated by the operations performed at the first blockwise decomposition, i.e., by the PLU factorization and the inversion of the

submatrix,

, and its Schur complement,

. The seven required multiplications of submatrices has the complexity,

. Consequently, the overall complexity is dominated by the two recursive calls, and the matrix multiplications, i.e.,

where

c is the total number of required submatrix multiplications. The Strassen’s algorithm for matrix multiplication has the complexity,

. The recursion (

8) can be solved by the Master Theorem [

10], which yields the total complexity,

. Moreover, since the base cases are assumed to be sufficiently small, they do not affect the overall asymptotic complexity. □

2.3. Implementation

The blockwise matrix inversion with the PLU factorization and Strassen’s matrix multiplication was implemented in C++ programming language [

8]. The implementation adopts several optimizations to improve the actual run-time of inverting large binary matrices. In particular, the low-level C++ data structure,

std::bitset<N>, is used to store the rows of binary matrices. This encourages compiled code to exploit the single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) CPU instructions, which provides the bit-level parallelism involving the bit arrays. In turn, this offers a substantial speed-up of adding and multiplying the rows of binary matrices.

The size of submatrices that are treated as base cases, and for which the GJE instead of the blockwise recursion is used, is a hyper-parameter that can be optimized for faster inversion. The former has better data locality, and avoids the overhead of recursive function calls.

The singular matrices, for which the GJE fails to find a pivot when inverting one of the base case submatrices, are detected using the function signature with, std::optional, parameter. This has the benefit that it avoids the complexities of exception handling.

The matrix to be inverted is instantiated at a compile time using the C++ template, template<size_t N>. It provides the type safety, and also reduces the runtime overhead.

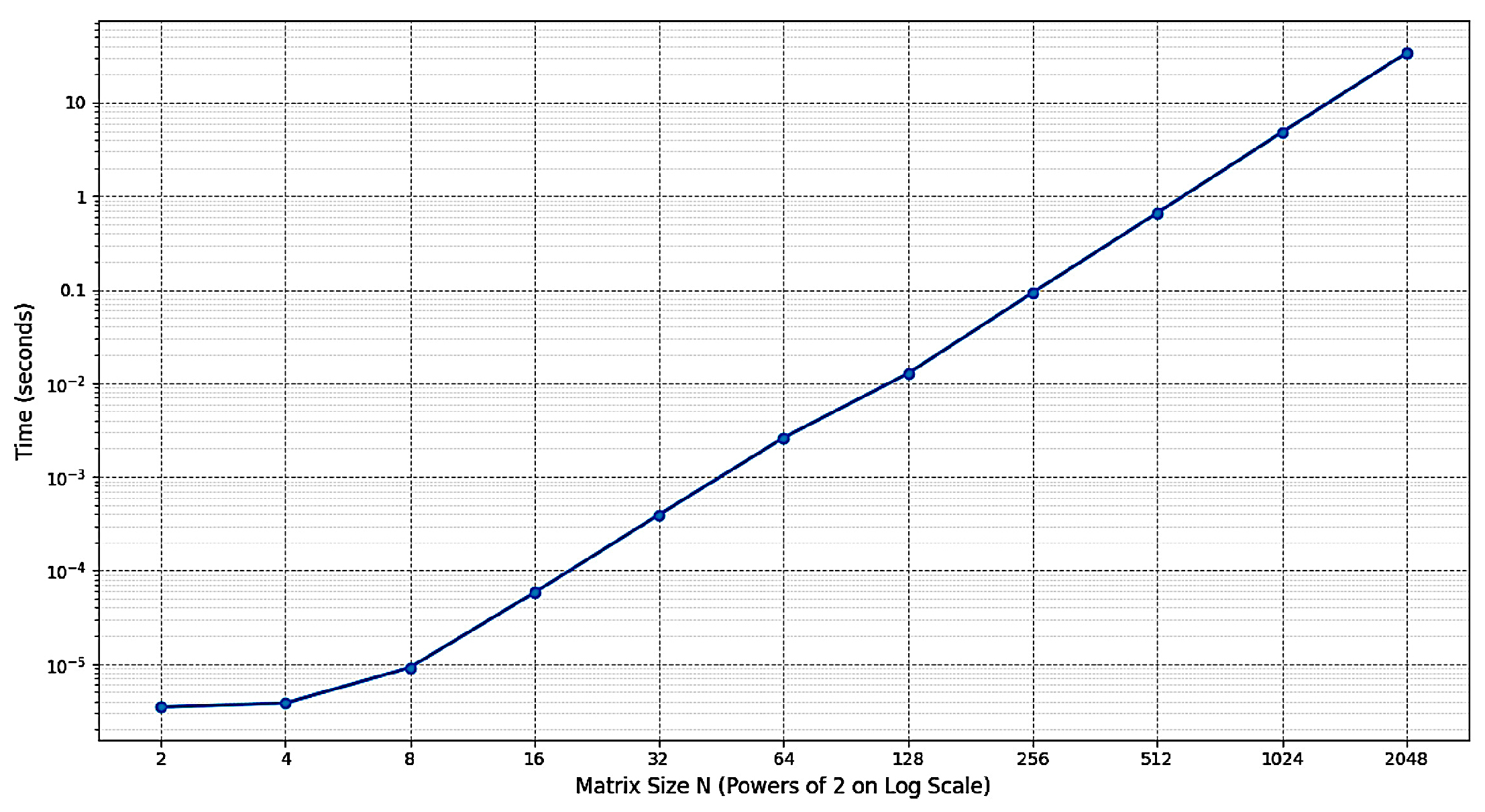

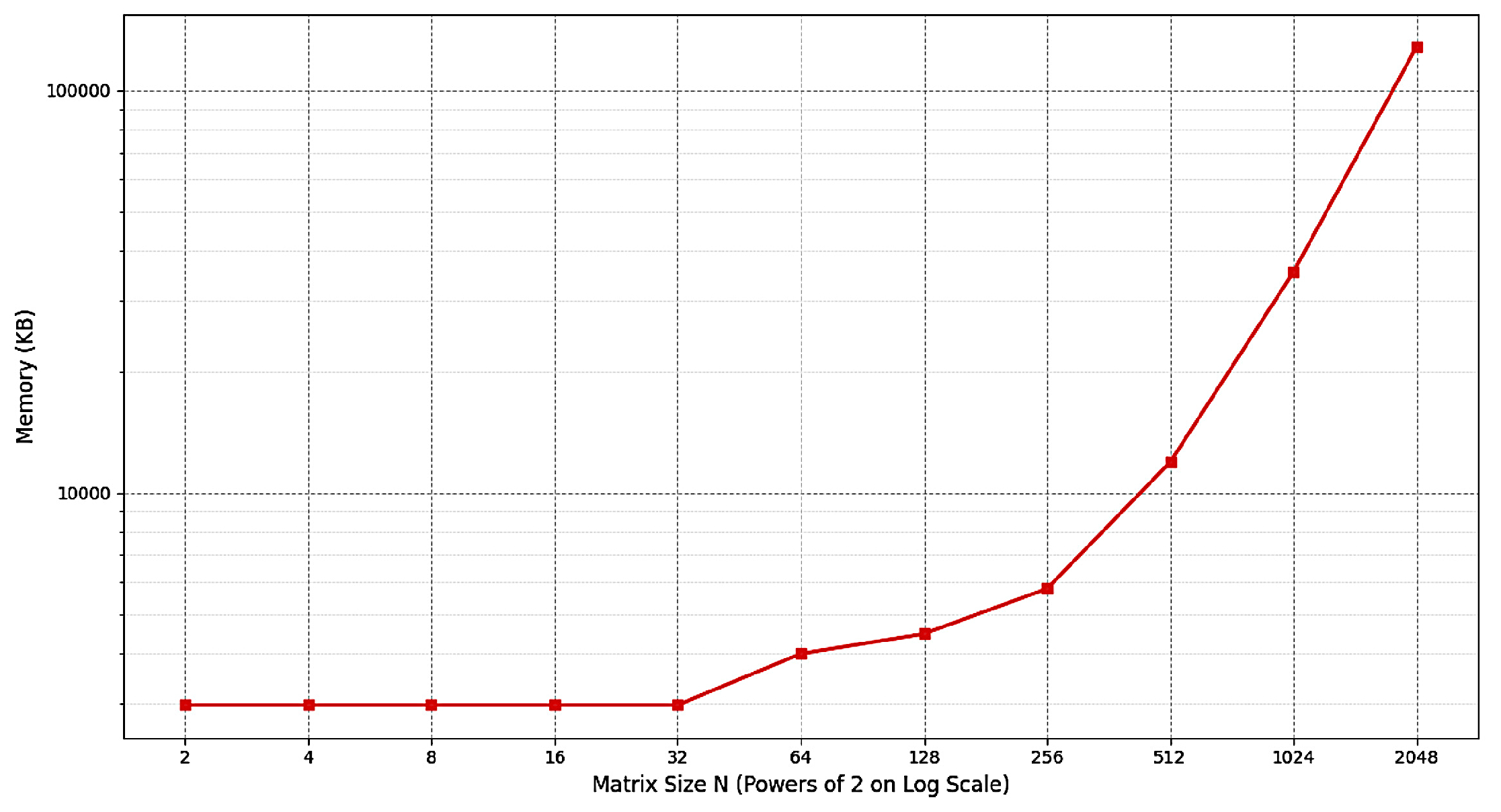

The empirical measurements of the runtime and memory usage for inverting the binary matrices of size,

,

, are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively. Both metrics appear to have asymptotically linear growths on the log-log scale plots suggesting the asymptotic complexity,

.

Even though the reference implementation in C++ considers specifically the matrices over , the blockwise recursive inversion with PLU factorization can be readily modified to other fields. However, only the computations over the finite Galois fields are exact, whereas the algorithms involving the floating point arithmetic suffer from numerical instabilities and numerically ill-conditioned problems. For example, the pivoting used in the GJE must be made more robust for inverting the real-valued matrices. Moreover, the bit-level parallelization can be much more easily exploited for the finite fields than for real numbers, which has a noticeable impact on the practical runtime and the memory usage of the implemented algorithms.

The matrix multiplications in Strassen’s algorithm can be parallelized to support the implementation of inverting very large matrices on multi-core computing platforms. For such matrices, the data structures could be further optimized to improve the data locality, and to exploit fast memory caching mechanisms. There can be multiple implementations for different values of the matrix sizes, . Similar considerations can be used for the high-throughput inversions of very large matrices in hardware, for example, FPGAs.

3. Enumerating Groups

In this section, the objective is to exhaustively enumerate the unique elements of a linear group,

. A naive approach may again exploit the PLU factorization, which has been assumed in the previous section for inverting very large binary matrices. The caveat is how to avoid a considerable redundancy by removing the duplicated matrices. Ideally, every unique invertible matrix of a given size is generated exactly once. The proposed solution is to consider the Bruhat decomposition theorem to define unique factorization of every invertible matrix [

7]. This theorem can be specifically restated for general linear groups as follows.

Theorem 2 (Bruhat decomposition of general linear groups).

The general linear group, , is a disjoint union of double cosets of the subgroup of upper triangular invertible matrices, , i.e.,

where is the symmetric group of permutation matrices.

Theorem 2 allows partitioning the group, , into the disjoint subgroups (called Bruhat cells), which are indexed by the permutation matrices. More importantly, every invertible matrix, , has a unique factorization, , where is a permutation matrix, and and are the lower and upper triangular matrices, respectively, having the non-zero elements that are strictly constrained by the structure of . The uniqueness of this decomposition enables the effective non-redundant enumeration of all invertible matrices.

In particular, the matrix, , is defined by so-called inversions of the permutation, , of a given permutation matrix, . The inversion is an index pair, , such that, , whereas . The matrix, , is only allowed to have non-zero entries at positions, . The number of inversions of permutation, , is denoted as, . Thus, there are k elements of matrix, , that can be freely selected from a given field, whereas other elements must be zero.

There are

disjoint cells corresponding to one permutation matrix,

. The order of each cell is a function of the number of inversions in

. For the field of cardinality,

q, the cell order is given by the formula,

The term, , accounts for the number of unconstrained upper-triangular matrices, , and the term, , accounts for the number of constrained lower-triangular matrix, , respectively.

The enumeration algorithm proceeds by systematically enumerating all permutation matrices,

. For each matrix,

, all invertible matrices in the disjoint cell,

, are generated. Assuming that the two matrix multiplications to construct a matrix,

, have the complexity,

, and noting that the double cosets are disjoint and cover the whole GL group, which has the order given by (

1), the overall complexity is,

For comparison, the naive enumeration of a group using the PLU factorization is performed by creating all combinations of products between permutation matrices, and lower and upper triangular matrices, respectively. The overall complexity is dominated by the number of these products, each having, , complexity. In addition, each resulting matrix must be checked whether it has already been generated previously, which has the complexity, . Consequently, the total complexity of the naive enumeration via the PLU factorization is, . Consequently, even though the complexity of the Bruhat-based enumeration is still exponential, it avoids the factorial scaling of the PLU based enumeration, and at the same time, it is guaranteed to systematically produce a sequence of the unique invertible matrices.

3.1. Implementation

The rows of binary matrices can be stored in

std::vector<int>, or in more efficient

std::bitset<N> data structure to enable the compiled C++ code to use the low-level SIMD instructions. The Bruhat-based enumeration of the general linear group,

, was implemented in C++ [

8]. For complexity comparison, and despite its inefficiency, the PLU-based enumeration was also implemented, but validated only for

. For smaller values of

n, the uniqueness of the generated matrices can be automatically enforced by exploiting the

std::set data structure with hashing or tree-based indexing. For larger

n, more advanced data structures are required such as the hash-tries. The complete sets of all lower and upper triangular matrices can be pre-generated, which results in the large memory footprint, but faster generation. Alternatively, these matrices can be generated sequentially.

It should be emphasized that the exhaustive enumeration of general linear groups is only feasible for invertible matrices over finite fields, otherwise the group order becomes infinite. Moreover, deciding whether the two real-valued matrices are identical is problematic, as it depends on the floating-point representation of their values. The PLU-based enumeration can be effective, provided that it is modified, so that only unique matrices are implicitly or explicitly generated. Moreover, the PLU-based enumeration is already “embarrassingly parallel”, allowing the distributed matrix generation.

4. Repairing Singular Matrices to Become Invertible

In many scenarios, large binary matrices may be nearly invertible, however, they are strictly singular by definition. Such a case can be practically resolved by finding a `closest” invertible matrix that is non-singular. The problem can be formulated as follows.

Problem 1. Given a binary matrix, , find the binary matrix, , having the minimal Hamming distance, .

Specifically, in the first step, the rank deficiency, , is computed to decide whether is invertible, or not. If is already invertible, i.e., , the algorithm terminates. Otherwise, the invertible matrix, , having the Hamming distance precisely, , is obtained by flipping exactly d bits in as explained below.

The rank (i.e., also the rank deficiency) can be computed by the standard GJE. The matrix rank is equal to the number of pivots [

4]. Specifically, when transforming the matrix into a row-echelon form, the

j-th column does not have a pivot, if there is no row,

, such that the element,

. The columns without a pivot are referred to as being pivot-free. Equivalently, the row-echelon form contains exactly

d all-zero rows. It is also important to record, which rows are swapped in the GJE process. The rows that were swapped and zeroed are referred as dependent rows, since they are linear combinations of the other rows. The identified pivot-free columns and dependent rows are then used to define the bit positions that need to be flipped in order to make the original matrix invertible.

Lemma 2 (Rank change due to single bit-flip). A single bit-flip changes the rank of binary matrix at most by one.

Proof. Let be a square binary matrix obtained by flipping the entry of , so that, , and the matrix, , has exactly one non-zero element at position, . The rank of sum, , since . Similarly, , and thus, . Consequently, . □

Assuming Lemma 2, the task now is to find the set of d bit-flips that reduce the rank deficiency of to zero, so that it becomes invertible. These bit-flips are defined by the following theorem.

Theorem 3 (Minimal bit-flips to make binary matrix invertible). The binary square matrix, , with rank deficiency, , can be made invertible by performing no less than and exactly d bit-flips at the intersection of the dependent rows and the pivot-free columns.

Proof. By Lemma 2, every bit-flip can increase the matrix rank by at most one. Thus, the minimum number of bit-flips required to make the matrix invertible is precisely equal to its rank deficiency,

d. The GJE produces the row-echelon matrix,

where

is a

invertible submatrix,

, and

is a

all-zero matrix. The

d all-zero rows are the swapped dependent rows, and the last

d columns are pivot-free [

4]. Since every bit-flip at the intersection of dependent row and pivot-free column is guaranteed to increase the rank exactly by one, it is necessary as well as sufficient to define the

d unique bit-flips. This is achieved by replacing the matrix,

, with a permutation matrix,

, of the same size, i.e., the modified matrix,

, becomes,

For instance, , is one possible solution. The rank of is the sum of ranks of its diagonal blocks, i.e., , so it is invertible. Furthermore, the modified matrix, , has the minimal Hamming distance, , which is equal to the rank deficiency of . □

4.1. Implementation

The C++ implementation again uses

std::bitset<N> data structure to store the matrix rows to allow the compiler to utilize the SIMD instructions for bit-level parallelism on a CPU [

8]. For instance, a binary matrix containing

bits requires approximately

MB of memory. The time complexity of making the matrix invertible is dominated by the GJE, which has the complexity,

. The GJE computations can be at least partially distributed, which is important in high-throughput applications requiring to invert large binary matrices such as designing forward error correction coding, cryptography, and quantized machine learning algorithms. Moreover, the GJE arithmetic operations for the matrices defined over

field are readily amenable to fast hardware implementations including, for example, FPGAs.

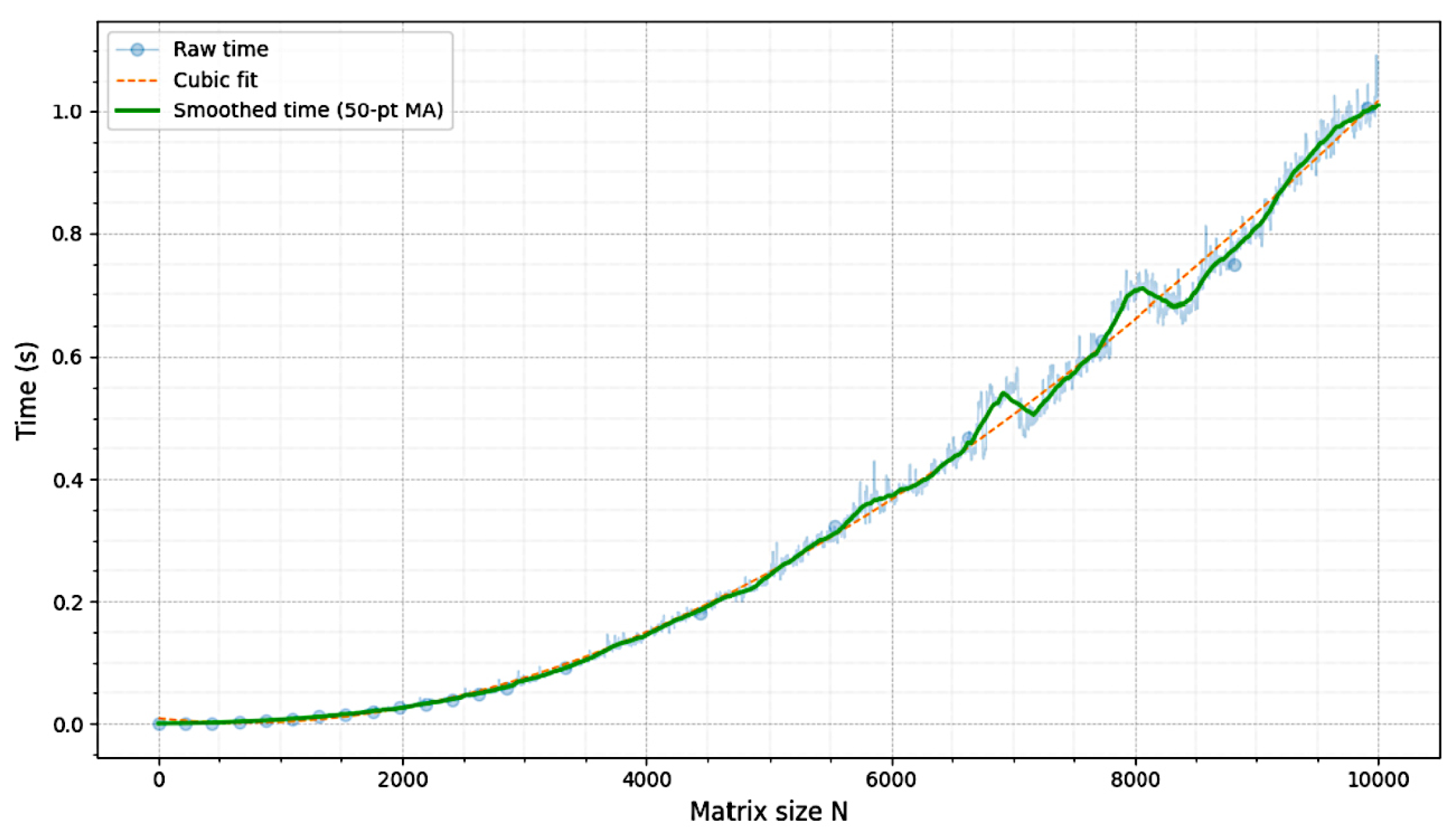

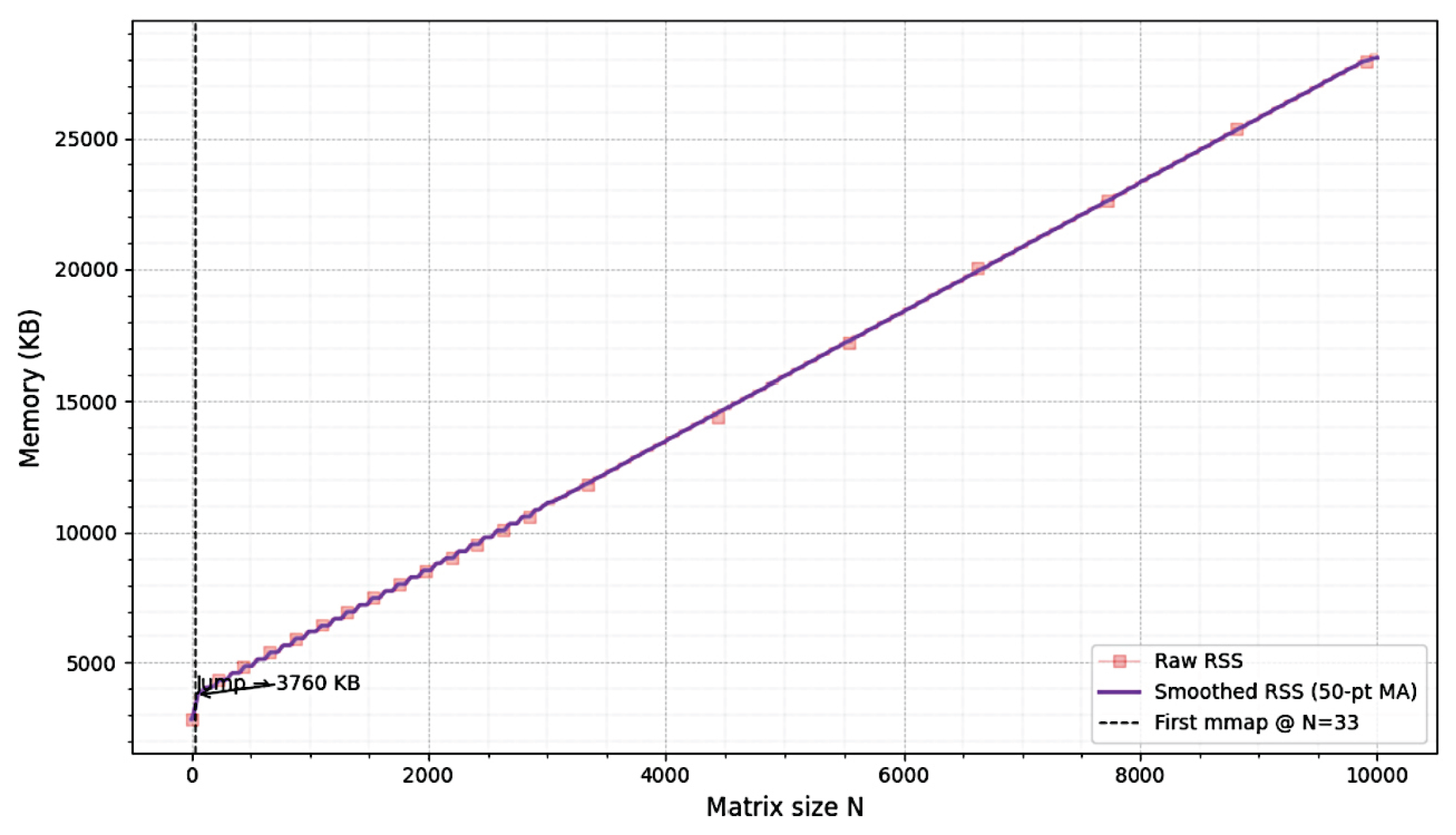

The empirical runtimes and the memory requirements of repairing randomly generated binary matrices to become invertible are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively. Note that a binary random matrix is invertible with the probability,

, for

.

It is unclear whether the required bit-flips to make the binary matrix invertible could be found more directly in order to reduce the cubic cost of the GJE. The complexity of the GJE itself can be reduced by adopting faster matrix multiplications, for example, using the Method of Four Russians, and other Strassen-like algorithms [

2].

5. Conclusions

The paper investigated the problem of inverting very large binary matrices. Specifically, a robust blockwise matrix inversion was proposed that is based on the PLU matrix factorization. The time complexity of this algorithm was evaluated both theoretically and empirically. Next, it was shown that the enumeration of general linear groups can be done much more efficiently by assuming the Bruhat decomposition rather than the PLU decomposition in order to only generate the unique invertible matrices. Finally, it was shown how to find an invertible binary matrix that is closest to a given singular binary matrix by performing the minimum number of bit-flips at the determined positions. The number of these bit-flips is equal to the rank deficiency of the original matrix. All proposed algorithms were validated to show their correctness. The reference C++ implementation is available from the public Github repository.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M., P.L., and T.H.; Formal analysis, I.M., P.L., and T.H.; Investigation, all; Supervision, P.L. and T.H.; Project administration, P.L.; Writing original-draft, I.M.; Writing review & editing, P.L; Visualization, I.M; Software, I.M.; Resources, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a research grant from Zhejiang University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Example of Matrix Inversion via PLU Decomposition

Consider inverting the binary matrix,

, of size,

,

The

submatrices are already sufficiently small, so they represent the base cases that can be inverted by the GJE. However, the submatrix,

, is clearly singular, so its inversion fails. When such a singularity is detected, it can be resolved by first permuting the rows of

. In particular, swapping the rows 2 and 3, the matrix to be actually inverted becomes,

The submatrix, , is now invertible, and the singularity problem is removed.

The pivoted factorization,

, yields the matrices,

The Schur complement of is computed using the inverse matrices, , and, . We get, . Since the size of is sufficiently small, it is treated as a base case, and factored directly as, , where .

The final step is to construct the inverse matrix

using (

7). The overall permutation matrix,

, consists of the products of submatrices,

, that were used at the intermediate steps of the algorithm. The overall triangular matrices,

, and,

, are constructed similarly from the submatrices

,

,

, and,

.

Appendix B. Three Examples of Making the Binary Singular Matrix

Invertible

Appendix Example 1

Consider the

binary matrix,

The matrix, , is singular, since the third row is the sum of the first and the second rows.

The row reduction by GJE is used to find the matrix rank, and to identify possible row-dependencies. In particular, let,

be the first pivot. Other 1’s in the first column are eliminated by simple row operations. This process is repeated assuming the pivot,

, which yields the row-echelon form,

The final pivot is the element at position, . Consequently, the rank is, , and the third column is the only column without a pivot. In the process, the third row of the original matrix, , is identified as the source of linear dependency, which reduces the matrix rank by one.

Since the rank deficiency is,

, exactly one bit-flip in

is required to recover the full rank. The position of this bit is determined by the dependent row and the pivot-free column, i.e., the bit-flip must be done at position,

. The resulting matrix,

has the full rank, and thus, it is invertible.

Appendix Example 2

Consider the

singular binary matrix,

The GJE identifies the third row to be linearly dependent on the other rows, and the third column is pivot-free. Consequently, the rank deficiency is, , and a single bit-flip at position, , makes the modified matrix, , to become invertible.

Appendix Example 3

Consider the

singular binary matrix,

The first and the fourth rows are identical, and so are the second and the fifth rows. Performing the GJE, the rank deficiency is found to be,

. The fourth and the fifth columns are pivot-free. The fourth and the fifth rows are linearly dependent. Consequently, exactly two bit-flips are required. There are four possibilities for these bit-flips in total. For example, the dependent rows and the pivot-free columns can be paired to make the bit-flips at positions,

, and,

. The resulting matrix,

has the full rank, and thus, it is invertible.

References

- Strassen, V. Gaussian Elimination is Not Optimal. Numerische Mathematik 1969, 13, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Bard, G.; Hart, W. Efficient Multiplication of Dense Matrices Over GF(2), 2013. arXiv:0811.1714.

- Zhang, F. The Schur Complement and Its Applications; Springer New York, NY, 2005.

- Golub, G.H.; Loan, C.F.V. Matrix Computations, 4th ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

- Dummit, D.S.; Foote, R.M. Abstract Algebra, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Gregor, P.; Hoang, H.P.; Merino, A.; Mička, O. Generating all invertible matrices by row operations, 2024. arXiv:2405.01863.

- Lusztig, G. Bruhat decomposition and applications, 2010. arXiv:1006.5004.

- Mammadov, I. Inverting Large Binary Matrices. https://github.com/1brahim74/Inverting-GF2-matrixes, 2025.

- Bunch, J.R.; Hopcroft, J.E. Triangular Factorization and Inversion by Fast Matrix Multiplication. Mathematics of Computation 1974, 28, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormen, T.H.; Leiserson, C.E.; Rivest, R.L.; Stein, C. Introduction to Algorithms, 4th ed. ed.; MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).