1. Introduction

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by approximately 25%, according to data reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). This surge reflects the substantial psychological burden associated with prolonged social isolation, fear of infection, bereavement, and financial instability. Young people, women and individuals with pre-existing physical illnesses (e.g., asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease) displayed a higher vulnerability to mental health symptoms[

1].

Even from the first year of the pandemic, it was observed long-term evolution of COVID-19, defined as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). This condition goes forward over 3 months after the onset, with persistent symptoms for at least 2 months and is not explainable by an alternative diagnosis. Some of the most common PASC symptoms include depression, anxiety, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia and cognitive impairments, affecting daily functioning levels [

2].

The pathophysiological theory of mental health symptoms and immune response to coronaviruses evidenced neuroinflammation, which is characterized by a “cytokine storm.” Monocytes release proinflammatory cytokines, affecting neurons, microglia, and astrocytes. These stimuli induce neuronal stress at the level of dendrites and impair neurogenesis, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Another mechanism is ischemia caused by microvascular dysfunction and thrombosis leading to small cerebral infarctions and persistent neurological impairment. Such changes can lead to behavioral pathologies, manifesting anxiety and depressive symptoms, the severity of which may improve between 1- and 3-months post-recovery as inflammation resolves over time [

3,

4,

5].

The biological mechanisms linking SARS-CoV-2 infection to the development of anxiety remain incompletely understood, although emerging evidence points to a central role of immune system overactivation and neuroinflammation. Increased levels of cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-1β, have been associated with the severity of psychiatric symptoms, while neuroimaging studies have documented functional and structural brain alterations affecting cognitive and emotional regulation networks. Additional mechanisms may involve dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the renin–angiotensin system. Despite accumulating evidence supporting this association, reported effect sizes are generally modest, and it remains unclear to what extent these findings reflect specific consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than nonspecific effects of hypoxia or systemic inflammation, underscoring the need for further investigation[

6].

In addition to psychosocial stressors, depression in COVID-19 positive patients may be due to direct viral infection of the brain or through an indirect immune response that again triggers neuroinflammation via a “cytokine storm”[

7]. Cytokines influence the brain in several ways that can lead to the development of depression [

8]. This includes hyper-activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which sets off a cascade of events resulting in neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration as well as disruption of synaptic plasticity, all of which are associated with an increased risk of major depressive disorder [

9].

Covid-19 had negative effects on sleep, a significant proportion of adults experienced poor sleep beyond 12 months after recovering from the initial infection [

10].

The COVID-19-sleep disorders are a major problem of rehabilitation of patients after infection. There is reported evidence that sleep apnea in humans and rodents induces systemic low-grade inflammation characterized by the release of cytokines, chemokines, and acute-phase proteins that promote changes in cellular components of the Blood Brain Barriere (BBB), particularly on brain endothelial cells and on tight junction proteins. Neuroinflammation and Brain Sleep loss alter permeability of brain barrier and might be a novel biomarker of the BBB leakage, but the mechanisms underlying the ‘coronasomnia’ phenomenon is still poor understood [

11].

Recent studies support a bidirectional relationship between insomnia and depression. Sleep disturbance is a risk factor and a diagnostic criterion for depression, but it is unclear how sleep affects depression. In addition to environmental factors, stressful social genetic factors contribute to the development of both depression and insomnia [

12].

Depression and sleep disturbances are closely interconnected through shared neurobiological mechanisms. Evidence suggests that both conditions involve dysregulation of monoaminergic, cholinergic, and neuroimmune pathways. Alterations in serotonin and noradrenaline signaling, which are central to mood regulation, together with cholinergic imbalance, contribute to disruptions of sleep architecture commonly observed in depressive and anxiety disorders. The orexin/hypocretin system, a key neuropeptidergic network, plays a critical role in regulating wakefulness, circadian rhythms, arousal, appetite, energy metabolism, electrolyte balance, and emotional processing. Dysfunction of orexin pathways has been associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms, which may explain the high prevalence of insomnia, fatigue, and cognitive impairment in affected individuals. These symptoms overlap considerably with PASC. Consequently, sleep impairment may represent not only a symptom, but also a contributing factor to the development and persistence of depressive disorders [

13].

The objective of this study was to assess the evolution of anxiety, depression, and sleep quality during the first post-COVID year in hospitalized, non-critical patients and to evaluate long-term outcomes up to four years after infection. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study in our region to examine mood disturbances in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with extended longitudinal follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

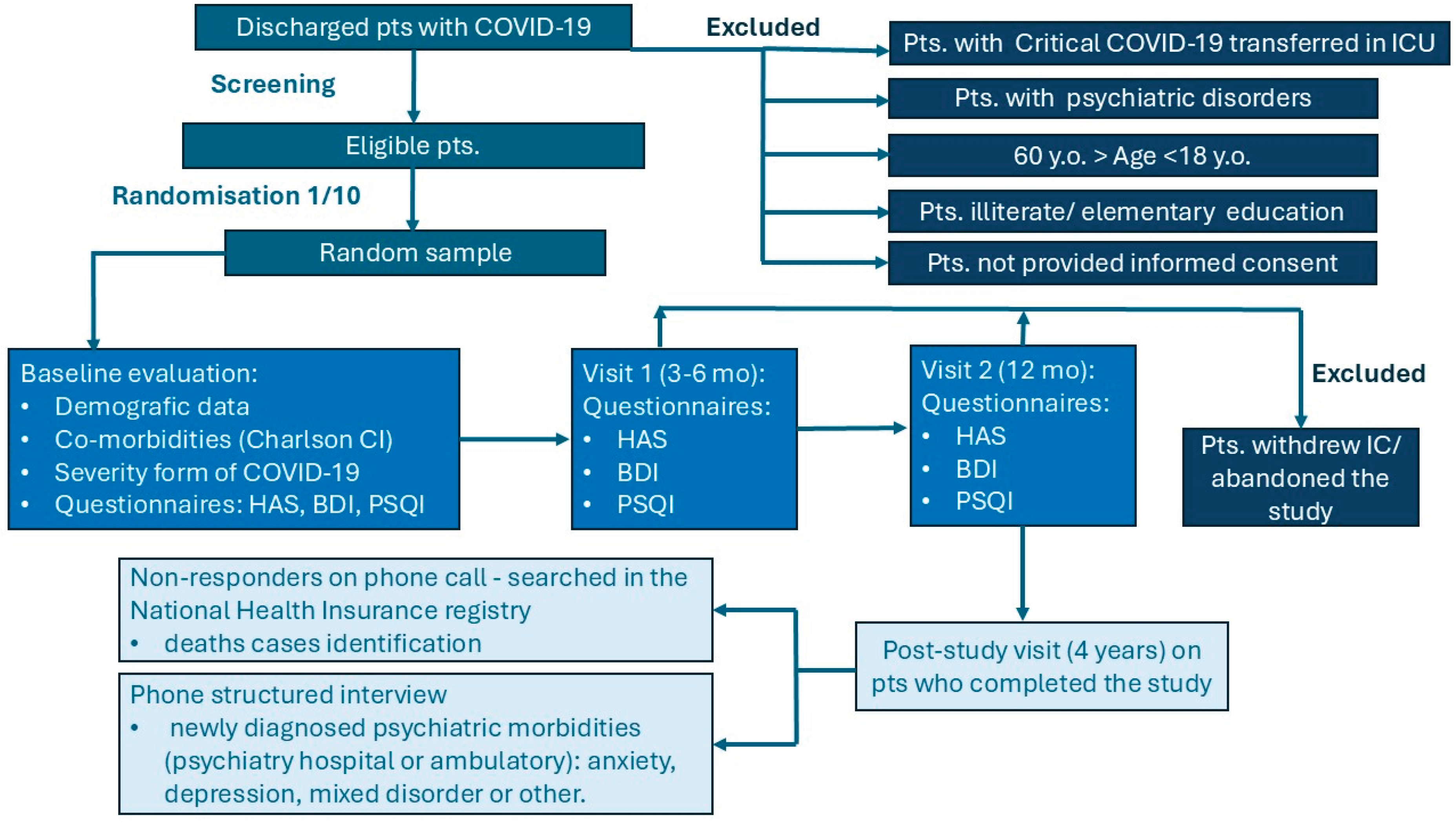

We conducted a prospective study on mood disorders related to the first episode of COVID-19 in hospitalized Romanian patients admitted to the Infectious Diseases Hospital in Galați, from August 2020 to July 2021. Baseline evaluation corresponded to the date of patient discharge following the first COVID-19 episode. At baseline, we collected demographic data, comorbidities, and information on the severity of COVID-19.

Anxiety was assessed using the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAS), depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and sleep quality and patterns using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Assessments were performed at baseline and during two on-site post-COVID-19 follow-up visits, at 3–6 months and 12 months.

A supplementary post-study follow-up was conducted via telephone between August 2024 and July 2025 to record whether patients had been newly diagnosed with a mental health disorder, specified as anxiety, depression, mixed disorder, or other. For patients who did not respond to the telephone call, we verified the national health insurance registry to identify deaths. Cases that could not be traced were considered lost to follow-up and were excluded from the analysis of post-COVID-19 outcomes, including mortality and mental health morbidity rates [

Figure A1].

2.2. Study Population

The study population was selected from Romanian adult patients hospitalized with symptomatic COVID-19 and virological confirmed by a real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR-SARS-CoV2 positive test, according to the case definition in use at the time.

The inclusion criteria were aged between 18 and 60 years old, and the agreement to participate in the study by written informed consent. We used the criteria for classification of COVID-19 infection into mild, moderate, severe, and critical forms according to WHO definitions and the national protocol for the management of COVID-19 infection, that was classified according to the current national protocols [

14,

15,

16]. On the day

of discharge, one in every ten patients was randomly selected to participate in the study.

The exclusion criteria were critically ill patients, those with neuro-psychiatric history, head trauma or substance use disorders and people who were illiterate or elementary school educated.

2.3. Data Collected

We assessed the demographic characteristics of the patients: age stratified under 40 or over 40, gender male or female, living environment urban or rural, educational level. We grouped the patients by education level in two categories: low (secondary education) and high (upper secondary education) [17].

We considered the risk factors of behaviors represented by smoking or alcohol, and obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) over 30 kg/m2. The BMI was calculated according to the standard formula, using height and weight measurements obtained through standard anthropometric procedures[

18].

The medical history of patients in the study group was assessed by calculating the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) based on documented comorbid conditions. Following score determination, patients were stratified into two categories according to a cutoff value of 4: low-risk (<4) and high-risk (≥4)[

19,

20].

We applied self-assessment questionnaires, using the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Each item of the questionnaires was analyzed, and the global score was evaluated in every visit from baseline, 3-6 months and 12 months follow-up.

2.4. Study Questionnaires

We assessed the severity of anxiety symptoms by HAS. The questionnaire consists of 14 items and assesses both psychic (mental) and somatic (physical) symptoms; each item is rated on a scale from “0” to “4”, where “0” means “not present” and “4” means “very severe”. Scores were summed up to give a total score. A score of 0-4 indicates absence of anxiety, 5-10 indicates mild anxiety, 11-16 indicates moderate anxiety, and 17 or higher indicates severe anxiety [

21,

22,

23].

The BDI test is a valuable tool for both clinical assessment and research, providing a structured way to evaluate depressive symptoms and their severity. We used BDI-II (1996) Romanian version, with a self-reported questionnaire containing 21 items, that assess affective, cognitive, somatic and vegetative symptoms. Each item was rated on a scale from “0” to “3”, where “0” means “not at all”, “1” means “several days”, “2” means “more than half the day”, and “3” means “nearly every day”, with a total score ranging from 0 to 63. The scores from 0-13 indicates minimal depression, 14-19 indicates mild depression, 20-28 indicates moderate depression, and 29-63 indicates severe depression [

24,

25,

26].

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to measure the quality of sleep, and to differentiate “poor” from “good” sleep. The questionnaire encompasses seven domains assessed over the preceding month: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Patients self-rated each domain on a 0–3 Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. A global PSQI score was computed by summing all component scores, and a threshold score of ≥ 5 was used to classify individuals as poor sleepers [

27,

28,

29].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, only patients who completed the study during the first year, including baseline, 6-month, and 12-month visits, were considered.

The distribution of the data was assessed using histograms to guide the selection of appropriate statistical tests. Descriptive analysis of numerical data was performed using the mean and standard deviation for normally distributed variables, and the mean, median, skewness, and extreme values (minimum and maximum) for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical data were summarized using frequencies, and significance was initially assessed using ANOVA where appropriate.

Pearson's chi-squared test was applied to assess the association between categorical variables. Nominal data were compared using either the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the independent t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, depending on data distribution. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data and Severity COVID-19 Episode

The study group consisted of 137 hospitalized patients with a mean age of 44.36 ±11.06 years, of whom 54% were women. Most participants, 82%, resided in urban areas and 64% completed at least high school education. Based on patient self-reports, 18.25% of participants were smokers, while 13.14% reported alcohol consumption. Obesity was present in 21.9% of patients. The Charlson Co-morbidity Index, in the population studied, ranged from 0 to 6, with a median value of 0. Only 2 patients (1.46%) had scores of 4 or higher, indicating that most participants had few or no comorbidities. These findings suggest that the studied population has a low comorbidity-related risk of mortality.

Of the patients, 22.63% had mild COVID-19, 48.18% moderate, and 29.20% severe disease [

Table A1].

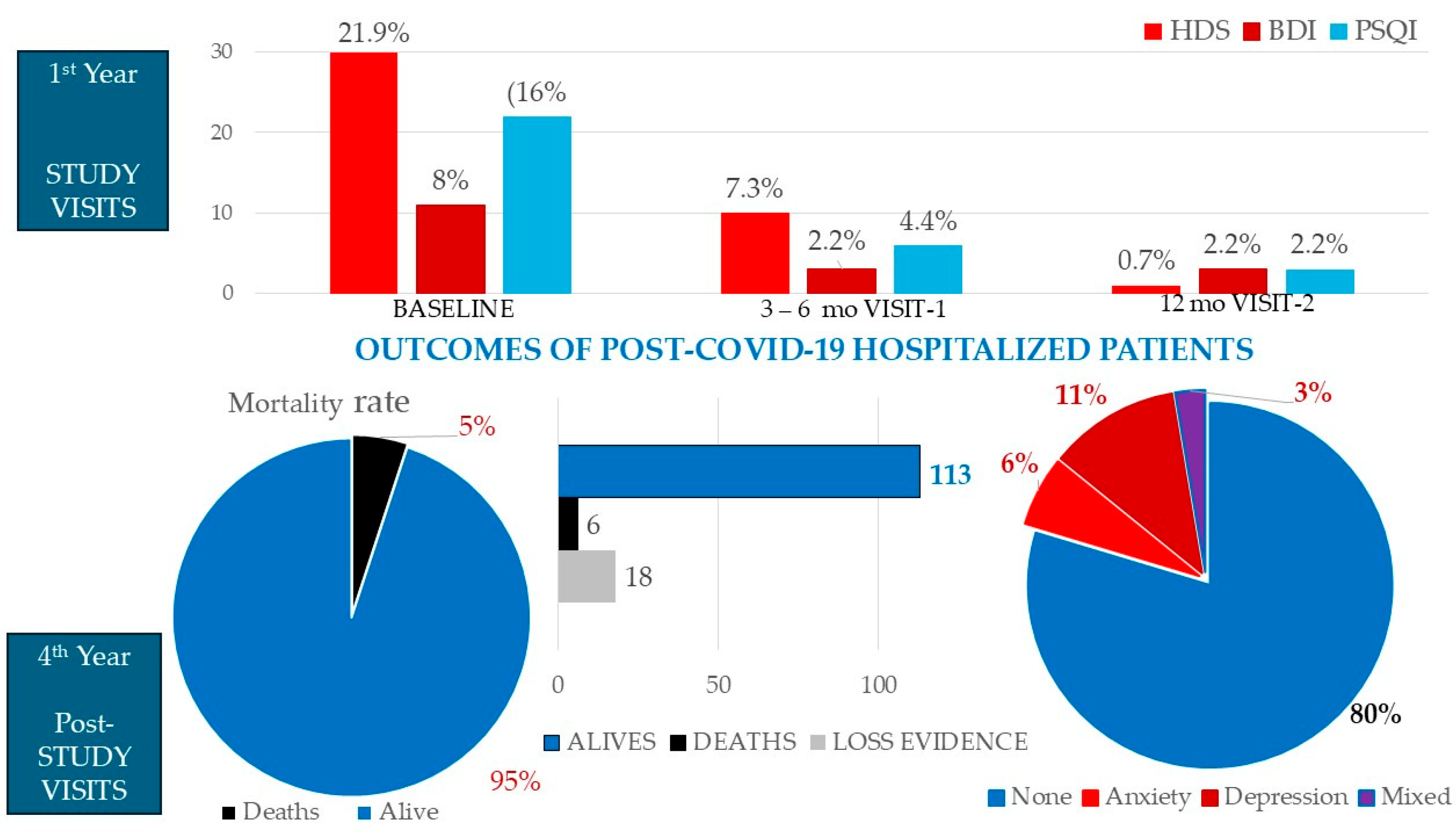

3.2. Anxiety in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19

The mean Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale score at baseline was 2.86 ± 3.69, decreasing to 1.15 ± 2.04 at 6 months and 0.43 ± 0.99 at 12 months. Based on the established severity categories, anxiety was identified in 21.9% of patients, manifesting predominantly as mild (14.6%) and moderate (7.3%) forms. No significant associations were observed for age, living area, education, smoking, or alcohol consumption. Anxiety symptoms were observed more frequently among female participants and in individuals who experienced more severe forms of COVID-19 [

Table 1].

At baseline, COVID-19–related anxiety was significantly associated with sex (p < 0.001) and disease severity (p = 0.028), with higher levels observed in females and in patients with more severe illness. No significant associations were found with age, residence, education, smoking, alcohol use, or obesity, suggesting that baseline anxiety was independent of these potential confounders.

Self-reported anxiety symptoms improved in most patients during the first year post-COVID-19, with mild symptoms persisting in 7.3% of cases at 6 months and only 0.7% at 12 months, indicating a substantial recovery over time.

3.3. Assessment of Depression in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19

The average score of depression in baseline was 4.11±3.21, according Back inventory scale. The score value dropped to 1.89 ± 2.30 after 6 months and to 1.10±2.39 after 12 months. Depression was reported in 8% of patients, all of them with mild forms. At baseline, depression levels were not significantly associated with sex, age, place of residence, education, smoking, alcohol use, obesity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, or COVID-19 severity (all p > 0.05), indicating that baseline depression was independent of these confounding factors [

Table 2].

According to the questionnaire, most cases returned to normal prior to the first visit (10/11 cases). At follow-up visits, symptoms persisted in one of these cases, while two additional patients developed newly developed depressive symptoms, representing 2.2% of the total study population. These findings suggest that depression associated with the COVID-19 episode is more likely a reactive form, triggered by the fear of an unknown and unpredictable illness, and is generally transient and reversible. The small sample size of cases limits the generalizability of these findings.

3.4. Sleapniess Scales in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19

The average sleepiness score was 3.74 ± 2.00, indicating a generally mild impact on sleep. However, 23.35% of patients reported scores ≥ 5, representing a subgroup with clinically relevant sleep disturbances. At baseline, sleep disturbances, as assessed by PSQI scores, were not significantly associated with sex, age, place of residence, education, smoking, alcohol use, obesity, or Charlson Comorbidity Index (all p > 0.05). In contrast, PSQI scores were statistically but weak associated with COVID-19 severity (p = 0.040), with more severe disease linked to poor sleep [

Table 3].

PSIQ scores slightly improved at 6 months (3.39 ± 1.84) and remained relatively stable in 12 months (3.38 ± 2.06). Remarkably, poor sleep was not associated with depression, neither in baseline, nor in 12 months visit. These findings suggest that baseline sleep quality in COVID-19 patients is influenced primarily by infectious disease severity rather than other known risk factors.

3.5. Long-Term Post-COVID-Psychiatric Morbidity and Mortalitay

Four years after COVID-19 hospitalization, 113 patients were successfully followed up by telephone interview, while 24 could not be contacted. Among these 24 individuals, six were identified as deceased in the national health-insurance registry, and the remaining 18 (13.13%) were classified as lost to follow-up. Accordingly, the 4-year post-COVID-19 mortality rate was 5%, which was significantly associated with a severe initial COVID-19 episode (p = 0.020) and higher Charlson Comorbidity Index scores (p < 0.001). No significant correlations were observed with anxiety, depression, or sleepiness identified during the first year after COVID-19 [

Figure 1].

Among the surviving patients, 20.35% (23/113) received specialist psychiatric evaluation, which resulted in formal diagnoses of 11.5% depression, 6.2% anxiety disorders, and 2.65%mixed disorders. No other psychiatric disorders were identified.

4. Discussion

The study evaluated the dynamics of anxiety and depression, commonly mental health disorders associated with COVID-19 during the early phase of the pandemic in hospitalized patients. At that time, the situation was particularly stressful due to the severity of the new disease, the uncertainty of long-term outcomes, the absence of a vaccine, and disruptions in the functioning of health services. Our prospective evaluation included a relatively homogenous group of hospitalized patients, to limit the confounders factors such as aging, education level, co-morbidities or pre-existent mental health disorders.

Anxiety was more frequent than depression related to acute episode of COVID-19, contrary to the findings in long-term follow-up. A meta-analysis of anxiety including 14 studies reported a general prevalence ranging from 16.6% (10.1–23.1%) to 29.6% (14.0–44.0%), close to 21,9% in our study [30].

Our results confirm a female predisposition to anxiety and its association with the severity of the COVID-19 hospitalization episode. Although anxiety scores substantially decreased during the first year post-COVID-19, an increasing trend was observed over the subsequent three years, suggesting the involvement of distinct pathogenic mechanisms [31].

In comparison, a global systematic review estimated a prevalence of 28% for depression. In our cohort, depression was identified in only 8% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients and in 2.2% after recovery, all cases being mild forms and without any significant correlation with demographic factors, comorbidities, or severity of the viral episode. These findings suggest that depression associated with COVID-19 is more likely a reactive form, triggered by the fear of an unknown and unpredictable illness, and is generally transient and reversible. However, three-year remote follow-up revealed an increase in the proportion of patients diagnosed with depression (11.5%), particularly new-onset cases. This may reflect either delayed effects potentially linked to viral-induced neuroinflammatory mechanisms or the natural incidence of depression in the general population, independent of the initial COVID-19 episode.

Most studies investigating anxiety and depression during the pandemic focused on the first three months after COVID-19. Approximately 30% of individuals showed pathological scores on psychometric scales, and 52.4% demonstrated persistent functional impairment, which was independently associated with ongoing physical symptoms [3]. Our findings extend these observations and provide a more optimistic perspective, showing gradual recovery of anxiety, depression, and poor sleep within 12 months.

Regarding the relationship between sleep quality and COVID-19, rates of sleep disturbances range from 26 to 75% in different studies, substantially higher than the 10–20% observed in the general population, with significant improvement during the first three months [

32,

33,

34].

A cross-sectional small study conducted after at least 12 weeks from the COVID-19 diagnosis used the same psychometric scales as our study and observed poor sleep quality, anxiety and depression, in 50%, 33.3%, and 29.2%, of the participants, respectively[

35].

In our study, sleep disturbances were less pronounced, affecting 16% of cases, with marked improvement observed at the subsequent two follow-up visits. Interestingly, poor sleep was not correlated with depression scores, as we might expect. We noted that all three patients who reported persistent poor sleep (PSQI≥5) in the 12 months visit had died in the post-study visit. Looking to deaths cases, we found significant correlation neither with PSQI scores, nor with HAS or BDI scores.

The relation between poor sleep and depression remains a critical domain that should be monitored and explored, knowing that depression and sleep disorders have significant impact on cognitive decline and dementia among COVID-19 survivors[

36].

This study has several key strengths. Its prospective design with repeated follow-up over four years allows a detailed evaluation of the temporal dynamics of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances post-COVID-19. Patients were randomly selected at discharge, reducing selection bias, and assessments were conducted using validated psychometric instruments (HAS, BDI, PSQI). Comprehensive baseline data, including demographics, comorbidities, and COVID-19 severity, enabled the analysis of potential risk factors. Study population in non-critically ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients, provides a unique insight into the evolution and emergence of psychiatric sequelae. Finally, this is the first long-term prospective study in the region simultaneously assessed anxiety, depression, and sleep quality, providing a holistic perspective on the mental health consequences of COVID-19. The four-year follow-up, including verification via national health records, allows for evaluation of delayed psychiatric manifestations, post-COVID-19 mortality, and persistence or emergence of new disorders.

Limits of Study

This study has several limitations. First, a control group could not be included because, during the enrollment period, the hospital was exclusively dedicated to COVID-19 care, which severely restricted access for non-COVID patients. Second, the study relied on self-reported psychometric questionnaires, and repeated assessments at 3–6-month intervals may have affected the accuracy of responses. Third, medical history, pre-existing neuropsychiatric conditions, and comorbidity profiles were based solely on patient declarations without verification through medical records, introducing potential recall or reporting bias. Fourth, follow-up visits were conducted via telephone interviews, which may have led to inaccuracies due to misreporting, misunderstanding, or intentional misrepresentation of symptoms. Fifth, loss to follow-up over the four-year period may have influenced outcome estimates and the observed prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Sixth, the relatively small sample size limits statistical power and reduces the generalizability of our findings. Finally, the study did not include objective measures such as neuroimaging, inflammatory biomarkers, or clinician-administered psychiatric assessments, which could have provided more robust insights into the pathophysiology and severity of post-COVID psychiatric and sleep disturbances.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

In this prospective cohort of hospitalized non-critically ill COVID-19 patients, post-COVID-19 anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances were more prevalent than in the general population, although less frequent than reported in other studies. Anxiety was the most common mood disorder and was influenced by gender and severity of the acute infection. Most psychiatric and sleep-related disturbances resolved within the first 12 months post-infection. However, long-term follow-up revealed a dynamic course, with new-onset cases of depression emerging after the first year, highlighting the need for ongoing monitoring and early intervention. These findings underscore the importance of recognizing and addressing post-COVID psychiatric and sleep sequelae to improve long-term mental health outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and M.-C.V.; methodology, M.A., M.-C.V., C.-I.V., M.S.-C.; software, A.-A.A. and C.P.-C.; validation, C.P.-C. and M.S.-C.; formal analysis, M.A., M.-C.V. and A.-A.A; investigation, M.-C.V.; resources, C.-I.V.; data curation, A.-A.A. and C.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-C. V., C-I.V., M. C.-S. and C.P.-C.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and A.-A.A.; visualization, M. C.-S. and C-I.V.; supervision, M.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Dunarea de Jos University from Galati, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Sf. Cuv. Parascheva” Clinical Hospital for Infectious Diseases Galati, Romania: No. 65/30 July 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BDI |

Beck Depression Inventory Charlson Comorbidity Index

|

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| COVID-19 |

Coronaviral Infectious Disease |

| IL |

Interleukine |

| HAS |

Hamilton Anxiety Scale |

| PSQI |

Pittsbourgh Sleep Quality Index |

| PASC |

post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Flow chart of the study design. Legend: CI: comorbidity index; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; HAS: Hamilton Anxiety Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Pts: patients.

Figure A1.

Flow chart of the study design. Legend: CI: comorbidity index; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; HAS: Hamilton Anxiety Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Pts: patients.

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics of the hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics of the hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

| |

N |

% |

P* |

| Age |

<40 years |

49 |

35.77% |

p<0.05 |

| 40-60 years |

88 |

64.23% |

| Gender |

Male |

63 |

46% |

0.347 |

| Female |

74 |

54% |

| Living area |

Urban |

91 |

66.42% |

p<0.05 |

| Rural |

46 |

33.58% |

| Education |

Low** |

112 |

81.75% |

p<0.05 |

| High*** |

25 |

18.25% |

| Smoke |

Yes |

25 |

18,25% |

p<0.05 |

| No |

112 |

81.75% |

| Alcohol |

Yes |

18 |

13.14% |

p<0.05 |

| No |

119 |

16.86% |

| Obesity |

Yes |

30 |

21.9% |

p<0.05 |

| No |

107 |

78.1% |

| Charlson Index |

<4 |

135 |

98.54% |

p<0.05 |

| ≥4 |

2 |

1.46% |

| COVID-19 severity |

Mild |

31 |

22.63% |

p<0.05 |

| Moderate |

66 |

48.18% |

| Severe |

40 |

29.20% |

References

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 2). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide; Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide [Accessed 2.11.2025].

- Mazza, M. G., De Lorenzo, R., Conte, C., Poletti, S., Vai, B., Bollettini, I., Melloni, E. M. T., Furlan, R., Ciceri, F., Rovere-Querini, P., & Benedetti, F. (2020). Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 89, 594–600. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A. A., Latif, A. A., & Elseesy, S. W. (2025). Cognitive impairment, depressive and anxiety disorders among post-COVID-19 survivors: A follow-up study. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 32(8). [CrossRef]

- Seighali, N., Abdollahi, A., Shafiee, A., et al. (2024). The global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorder among patients coping with post COVID-19 syndrome (long COVID): A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 24, 105. [CrossRef]

- Vasile MC, Vasile CI, Arbune AA, Nechifor A, Arbune M (2023). Cognitive Dysfunction in Hospitalized Patient with Moderate-to-Severe COVID-19: A 1-Year Prospective Observational Study. J Multidiscip Healthc., 16:3367-3378. https://doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S432969.

- Burkauskas, J., Branchi, I., Pallanti, S., & Domschke, K. (2023). Anxiety in post-COVID-19 syndrome – prevalence, mechanisms and treatment. Neuroscience Applied, 3, 103932. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F., Mazza, M., Cavalli, G., Ciceri, F., Dagna, L., & Rovere-Querini, P. (2021). Can cytokine blocking prevent depression in COVID-19 survivors? Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, 16(1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, P. A., Ayari, L., Madry, J., Betts, C., Robinson, D. M., & Kirmani, B. F. (2023). The relationship between COVID-19 and the development of depression: Implications on mental health. Neuroscience Insights, 18, 26331055231191513. [CrossRef]

- Lorkiewicz, P., & Waszkiewicz, N. (2021). Biomarkers of post-COVID depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4142. [CrossRef]

- Batool-Anwar, S., Fashanu, O. S., & Quan, S. F. (2025). Long-term effects of COVID-19 on sleep patterns. Turkish Thoracic Journal, 26(1), 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Batool-Anwar, S., Fashanu, O. S., & Quan, S. F. (2025). Long-term effects of COVID-19 on sleep patterns. Turkish Thoracic Journal, 26(1), 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Yasugaki, S., Okamura, H., Kaneko, A., & Hayashi, Y. (2025). Bidirectional relationship between sleep and depression. Neuroscience Research, 211, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Ruhrländer, J., Syntila, S., Schieffer, E., & Schieffer, B. (2025). The orexin system and its impact on the autonomic nervous and cardiometabolic system in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Biomedicines, 13(3), 545. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health of Romania. (2020, March 23). Order no. 487 for the approval of the treatment protocol for SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Official Gazette no. 242 of March 24, 2020.

- Ministry of Health of Romania. (2020, August 10). Order no. 1418 on the amendment of the annex to the Order of the Minister of Health no. 487/2020 for the approval of the treatment protocol for SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Official Gazette no. 719 of August 10, 2020.

- Bhimraj, A., Morgan, R. L., Shumaker, A. H., Lavergne, V., Baden, L., Cheng, V. C., Edwards, K. M., Gandhi, R., Muller, W. J., O’Horo, J. C., Shoham, S., Murad, M. H., Mustafa, R. A., Sultan, S., & Falck-Ytter, Y. (2020). Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clinical Infectious Diseases. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2012). International Standard Classification of Education: ISCED 2011. Montreal: UNESCO-UIS. Available at: https://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced. [Accessed 12.01.2021].

- National Institutes of Health. (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—The evidence report. Obesity Research, 6(Suppl 2), 51S–209S.

- Charlson, M., Szatrowski, T. P., Peterson, J., & Gold, J. (1994). Validation of a combined comorbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 47(11), 1245–1251. [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L., & MacKenzie, C. R. (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(5), 373–383. [CrossRef]

- Maier, W., Buller, R., Philipp, M., & Heuser, I. (1988). The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: Reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 14(1), 61–68.. https://doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9.

- Tiwari, K., & Ojha, R. (2024). A study on Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale among college students. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 10, 1725–1731. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Zhu, E., Ai, P., Liu, J., Chen, Z., Wang, F., Chen, F., & Ai, Z. (2022). The potency of psychiatric questionnaires to distinguish major mental disorders in Chinese outpatients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1091798. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-H., Lee, S.-J., Hwang, S.-T., Hong, S.-H., & Kim, J.-H. (2017). Reliability and validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-II among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investigation, 14(1), 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 35(4), 416–431. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Assessment of depression in medical patients: A systematic review of the utility of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Clinics (São Paulo), 68(9), 1274–1287. [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. III, Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [CrossRef]

- Mollayeva, T., Thurairajah, P., Burton, K., Mollayeva, S., Shapiro, C. M., & Colantonio, A. (2016). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 25, 52–73. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C., Bellon, S., Hinkey, M., Nash, A., Boyd, J., Cook, C. E., & Garcia, A. N. (2020). Measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures used to assess the sleep quality in adults with high-prevalence chronic pain conditions: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine, 74, 315–331. [CrossRef]

- James, B. B., Rengasamy, E. R., Watson, C., et al. (2022). Persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Communications, 4(1), fcab297. [CrossRef]

- Diogo Gonçalves, S., Santos, A. L., Ramos, C., Valente, F., Jesus, L., Pereira, A. J., & Chyczij, F. (2025). Mental health in Europe after COVID-19: A systematic review of depression, anxiety, and stress among adult primary health care users. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 109. [CrossRef]

- Tomasoni D, Bai F, Castoldi R, Barbanotti D, Falcinella C, Mulè G, Mondatore D, Tavelli A, Vegni E, Marchetti G, d'Arminio Monforte A. Anxiety and depression symptoms after virological clearance of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Milan, Italy. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(2):1175-1179. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26459..

- Adibi, A., Motahharynia, A., & Adibi, I. (2025). Long-term consequences of COVID-19 on sleep, mental health, fatigue, and cognition: A preliminary study. Discover Mental Health, 5, 66. [CrossRef]

- Popovici, G. C., Georgescu, C. V., Vasile, M. C., Vlase, C. M., Arbune, A. A., & Arbune, M. (2024). Obstructive sleep apnea after COVID-19: An observational study. Life (Basel), 14(8), 1052. [CrossRef]

- Tanriverdi, A., Savci, S., Kahraman, B. O., & Ozpelit, E. (2022). Extrapulmonary features of post-COVID-19 patients: Muscle function, physical activity, mood, and sleep quality. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 191(3), 969–975. [CrossRef]

- Albu, S., Zozaya, N. R., Murillo, N., García-Molina, A., Chacón, C. A. F., & Kumru, H. (2021). What’s going on following acute COVID-19? Clinical characteristics of patients in an out-patient rehabilitation program. NeuroRehabilitation, 48(4), 469–480. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).