1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that emerges during childhood and is characterised by alterations in communication and social interaction, as well as by the presence of repetitive behaviours or restricted patterns of interest. These manifestations vary considerably among individuals, which justifies the term “spectrum”: it is not a single, homogeneous condition, but rather a range of profiles differing in severity, preserved abilities, and support needs. The heterogeneity of the disorder means that some children display mild difficulties that allow for a reasonable degree of autonomy, whereas others present more severe limitations affecting virtually all areas of life. This variability also requires that diagnosis and both educational and clinical support be tailored to the specific characteristics of each case [

1].

A diagnosis of ASD in a child has a significant impact on family dynamics. Such families often face emotional, social, and financial challenges that affect their overall wellbeing [

2]. Caregivers of individuals with ASD experience high levels of stress linked to the demands of caregiving, as well as to the child’s communication difficulties and behaviours. In addition, social stigma, isolation, and discrimination exacerbate the emotional burden and reduce their quality of life. Caring for a person with ASD also entails a substantial financial burden: the total costs associated with such care can exceed one million euros over a lifetime. These expenses include specialised therapies, adapted education, and loss of income on the part of the main caregivers, who are often forced to reduce their working hours or leave employment due to the lack of time to balance professional and caregiving responsibilities [

3,

4]. Behavioural and emotional problems, sensory profiles, and the severity of the disorder are variables that may further increase caregivers’ stress levels [

5].

In this context, health services, both primary and specialised, must address not only the needs of the diagnosed individual but also those of their family environment. Nurses, alongside other professionals, should provide comprehensive care to families, offering counselling, guidance, and emotional support. The benefits of such interventions include active information-seeking, the strengthening of social and spiritual support, acceptance of the condition, and reinforcement of self-esteem. It is also essential to conduct systematic follow-up of the primary caregiver, providing recommendations, identifying early signs of problems, and delivering training and information regarding the necessary care [

6].

Despite growing evidence on the importance of individualised care, significant gaps remain in the support provided to families of people with ASD. Multifactorial and cross-cutting factors continue to contribute to high levels of parental stress [

7]. Various studies have demonstrated the usefulness of parental training programmes and behavioural therapies, which foster solidarity and shared learning among parents [

4]. However, limitations persist, including the lack of individualised attention and insufficient resources, which constrain their effectiveness [

4].

It is therefore essential that healthcare professionals provide families with adequate support and resources to promote effective strategies for preventing parental stress. The implementation of early intervention programmes and access to support networks can significantly improve the quality of life of both the child with ASD and their family [

8]. Health professionals such as nurses have the responsibility to inform families about the existence of parent associations for children with ASD, which offer diagnostic, assessment, and counselling services, as well as respite care programmes, leisure activities, training, and parent education initiatives. Health education for the families of affected children is essential, ensuring that they can find support within the healthcare system [

9].

Within this framework, it is crucial to conduct situational assessments that allow for the design of appropriate intervention strategies. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify the level of stress among caregivers of children with ASD affiliated with the Ánsares Association in Huelva (Spain), considering a range of sociodemographic variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

A quantitative, descriptive, observational, and cross-sectional study with an exploratory scope was conducted. This type of design is appropriate for describing understudied phenomena and establishing preliminary trends or relationships between variables.

Although the study was not intended to produce statistically generalisable results, it sought to provide an accurate description of the level of parental stress in a representative sample of caregivers of children with ASD affiliated with the Ánsares Association in Huelva.

The relatively small sample was selected purposively, based on accessibility and relevance to the study objectives. This approach enabled the inclusion of participants sharing homogeneous characteristics regarding their caregiving role and exposure to the demands associated with ASD, thereby ensuring the descriptive validity of the findings.

The cross-sectional design allowed data to be collected at a single point in time, identifying possible associations between parental stress levels and various sociodemographic variables, without establishing causal relationships.

2.2. Context, Population and Sample

The geographical scope of the study was the province of Huelva (Spain). To access the target population, collaboration was established with the Ánsares Association, a local organisation working with families and children with ASD.

The study population consisted of relatives of children with a confirmed diagnosis of ASD who participated in the association’s therapeutic activities. Access to participants was facilitated by the association’s director, who informed families about the study objectives and connected them with the research team.

A purposive non-probability sampling strategy was applied, selecting those relatives who met the inclusion criteria and expressed willingness to participate. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

- -

Inclusion criteria: Parents of children diagnosed with ASD who attended therapeutic sessions at the association.

- -

Exclusion criteria: Parents of children without a confirmed ASD diagnosis.

The final sample consisted of 57 parents, of whom 75.4% were women and 22.8% men. Despite the small sample size, several strategies were adopted to ensure methodological rigour and the validity of the results [

10]:

Standardised administration of the questionnaire under homogeneous conditions.

Careful review and cleaning of data prior to statistical analysis.

Detailed documentation of the data collection process and related ethical considerations.

These measures ensured the consistency and representativeness of the data within the specific context of the association.

2.3. Variables and Assessment Instrument

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Variables

Independent sociodemographic variables were collected, including the age of the child with ASD and the main caregiver, sex, marital status, educational level, occupation, number of children, religious beliefs, and external caregiving support (presence or absence of an additional caregiver).

2.3.2. Dependent Variables

The dependent variables were measured using the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF), originally developed by Abidin [

11] and widely used to assess stress associated with the parental role. This questionnaire identifies the emotional and cognitive impact on parents and highlights risk areas that may require psychological support or intervention.

The abbreviated PSI-SF consists of 36 items distributed across three dimensions [

11,

12]:

1. Parental Distress: stress derived from the demands and responsibilities of the parental role.

2. Parent-child dysfunctional interaction: perception of dissatisfaction or disconnection in the relationship with the child.

3. Difficult child: evaluation of the child’s behaviour as problematic or hard to manage.

Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The instrument yields a total score (range: 24-120) and specific scores for each subscale: Parental Distress (7-35), Dysfunctional Interaction (6-30), and Difficult Child (11-55).

There are no universal cut-off points; normative percentile distributions are used instead. Following the original manual [

11] and subsequent adaptations [

12,

13], the following criteria were applied:

≥ 85th percentile: clinically significant stress.

75–84th percentile: high stress, risk zone.

20–74th percentile: normal range.

≤ 15–20th percentile: low stress (possible minimisation).

The PSI-SF has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in various cultural contexts, including validation in Spanish-speaking populations [

13], supporting its reliability and relevance for this research. Previous studies have reported internal consistency coefficients between 0.84 and 0.93 for the total score, and values above 0.70 for the three subscales [

14,

15,

16], confirming its robustness and suitability for the present study.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data collection took place at the Ánsares Association headquarters in Huelva. An initial meeting was held with the association’s director to present the study objectives and agree on the logistical aspects of its implementation. During this meeting, the research schedule was defined, and all necessary documentation was provided, including institutional authorisation, informed consent forms, questionnaires, and ethical approval. The data collection instrument comprised a set of sociodemographic questions and the items from the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF). Questionnaires were distributed during the association’s activity sessions over several days to ensure that all family members had sufficient time and opportunity to complete them calmly. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and self-administered, with the option of requesting clarification from the researchers present.

Given that children with ASD and their families constitute a vulnerable population, ethical safeguards were maximised to minimise potential risks, limited to possible emotional discomfort. A referral protocol was in place if needed. Questionnaires were completed in private rooms to guarantee confidentiality and respect for participants’ privacy. Completed forms were securely stored until statistical analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Firstly, a descriptive analysis of sociodemographic variables and parental stress levels was conducted. For quantitative variables, measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated, including mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values. For categorical variables, absolute frequencies and percentages were reported.

Before conducting inferential analyses, the normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, as the sample size exceeded 50 participants. This step determined whether to apply parametric or non-parametric tests as appropriate.

Subsequently, bivariate analyses were performed to explore potential associations between parental stress levels and sociodemographic variables. Depending on data characteristics, the following tests were applied: Pearson’s chi-square, Kruskal-Wallis H, and one-way ANOVA. A two-tailed significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for biomedical research outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report, as well as the ethical standards of the Code of Good Scientific Practice approved by the Spanish National Research Council [

17]. Compliance was also ensured with Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights [

18], and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of 27 April [

19].

All participants received written information about the study objectives and signed an informed consent form, guaranteeing voluntary participation, the right to withdraw at any time, and confidentiality of the information provided. Data were anonymised through the assignment of alphanumeric codes and securely stored in accordance with data protection standards. The study proposal was authorised by the management board of the Ánsares Association and approved by the Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Huelva (reference no. SICEIA-2025-000320).

3. Results

3.1. Measurement of Participants’ Stress Levels

Most participants scored within the normal range (56.9%), followed by 19.6% who reported low levels of stress. A total of 9.8% presented elevated stress levels, and 13.7% fell within the clinically significant range (

Table 1).

3.2. Dimensions of Parental Stress

In the parental distress dimension, 5.9% of caregivers exhibited elevated stress and 17.6% scored within the clinically significant range (

Table 2).

Regarding parent-child dysfunctional interaction, 7.8% showed elevated stress and 15.7% clinically significant stress (

Table 2).

Lastly, in the difficult child dimension, some parents perceived their children as particularly challenging to manage, with 5.9% presenting elevated stress and 17.6% clinically significant levels (

Table 2).

3.3. Stress Levels According to Sociodemographic Variables

No statistically significant associations were found between parental stress levels and sociodemographic variables (marital status, occupation, educational level, religious beliefs, or external support) (

Table 3). However, some descriptive trends were observed.

When stress levels were analysed according to marital status, married participants showed the highest proportion of clinically significant cases, followed by single and divorced participants. Nonetheless, no statistical dependence was observed between stress level and marital status (

Table 3).

In terms of occupation, results indicated that housewives presented the highest percentage of clinically significant stress, whereas most employed participants scored within the normal range. However, no significant dependence was found between occupation type and stress level (

Table 3).

Regarding educational level, both extremes of education (primary and postgraduate) displayed the highest percentages of clinically significant stress, while participants with vocational training mainly fell within the normal range. Again, no dependence was observed, suggesting that educational level was not a determining factor for parental stress in this sample (

Table 3).

Concerning religious beliefs, believing parents reported more clinically significant cases than non-believers, who mostly showed normal levels. Nonetheless, no dependence was observed between these variables (

Table 3).

Finally, participants without external caregiving support for their child with ASD presented slightly higher proportions of clinically significant cases compared to those who did have such support. However, no dependence was found between external support and stress level (

Table 3).

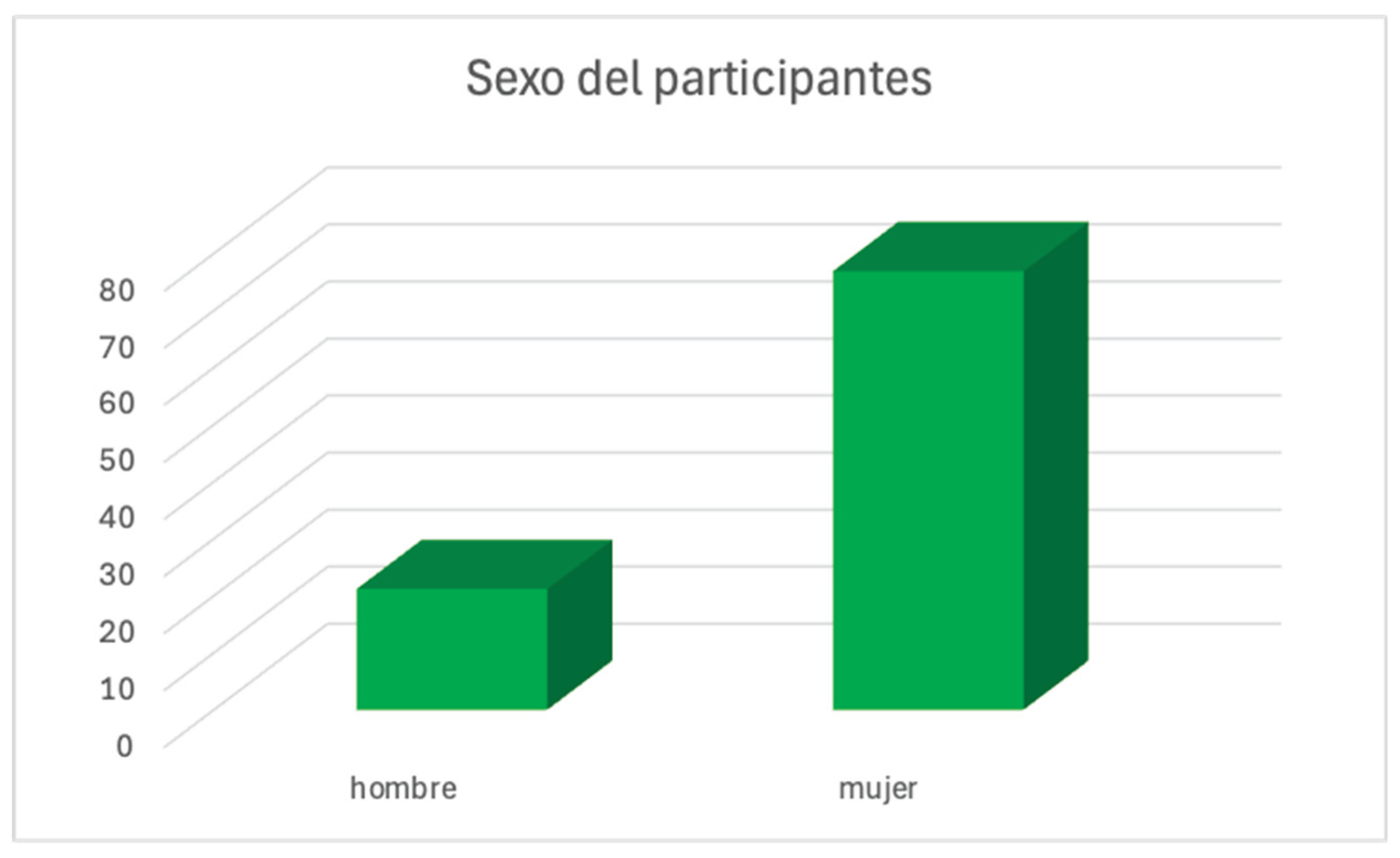

3.4. Stress Level as a Function of Sex

The distribution of the sample by sex showed a clear predominance of women, representing 78.4% of the total, compared with 21.6% male participants (

Figure 1).

Women presented a higher proportion of clinically significant cases (17.5%) compared to men, although the differences were not statistically significant (χ² = 5.258; p = 0.154) (

Table 4).

3.5. Stress Level as a Function of Age and Number of Children

No statistically significant differences were observed between participants’ age and stress level (Kruskal-Wallis H = 2.924; p = 0.404).

Similarly, the number of children showed no significant association with stress levels (F = 0.319; p = 0.811).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the level of parental stress among relatives of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) belonging to the Ánsares Association in Huelva, while considering various sociodemographic variables. The findings indicate that a proportion of parents of children with ASD experience stress levels that, in some cases, reach clinically significant values. Although no statistically significant associations were found with sociodemographic variables (p > 0.05), the descriptive patterns are consistent with previous literature, which highlights mothers’ greater vulnerability and the influence of social support on the caregiving experience [

5,

20]. These findings suggest that, beyond sociodemographic characteristics, parental stress in families with children with ASD arises from a combination of emotional, behavioural, and structural demands that are difficult to manage without professional support.

The high proportion of caregivers reporting distress reinforces what was previously stated by Arphi [

21], who identified the use of avoidant coping strategies as a factor that increases stress and reduces quality of life. The absence of significant associations in the present study may be partly explained by the small sample size and the heterogeneity of family profiles. Nevertheless, the data support earlier research describing parental stress as a multifactorial and cross-cutting phenomenon in families of children with ASD, one not always explainable solely by sociodemographic factors [

7].

Regarding sex, results showed that women tend to present higher levels of stress than men. These results are consistent with findings from the scientific literature, which indicate that mothers tend to employ more emotion-focused coping strategies, potentially increasing anxiety and hindering adaptation to complex situations [

22]. In addition, employment status has been shown to influence stress levels among mothers of dependent children, with higher stress reported among those who work [

23]. However, women often display greater problem-solving capacity and proactivity when addressing difficulties compared to men [

24].

With respect to occupation, caregivers who were housewives presented higher percentages of stress than those in other employment situations. This finding aligns with previous research showing that unrecognised and therefore unpaid forms of work tend to be associated with fewer available resources, leading to greater stress and poorer coping ability when facing challenging situations [

22].

Lastly, regarding religious beliefs, caregivers who identified as believers reported higher percentages of clinically significant stress than those without religious affiliation. Most studies in the literature differ from these findings, as religion is often seen as a protective factor [

22]. Although faith can promote family cohesion and positive coping, no direct association was observed in this study, suggesting that its role may vary depending on cultural context and personal experiences of faith.

Taken together, the results of this study highlight the complexity of parental stress in families with children with ASD. This phenomenon does not depend solely on sociodemographic variables, but rather on the interaction between individual, familial, and contextual factors. Consequently, it is essential to strengthen psychoeducational and emotional support networks, as well as to incorporate nursing interventions focused on the early detection of distress and the promotion of family well-being.

4.1. Limitations, Future Research Lines and Implications for Clinical Practice

This study provides relevant evidence on parental stress in families of children with ASD; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. It is a cross-sectional study in which the relationship between variables was measured at a single point in time, without follow-up. Therefore, many of the measured variables may change over time, which could affect stress indicator scores.

Another limitation concerns variables not included in the analysis, such as caregivers’ mental health history or access to social, economic, and healthcare resources, all of which may influence stress levels [

25]. Future research should therefore expand the sample size, include longitudinal follow-up, and incorporate these additional factors to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of parental stress in this population. The results of this study have several important implications for professional practice. It is crucial to enhance healthcare professionals’ capacity to identify stress-related problems among caregivers of children with ASD, enabling the development of more tailored care plans for each patient and family. Strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration (including social workers, psychologists, and other professionals) is also essential to ensure comprehensive care that addresses all dimensions of the individual. In this sense, the role of nursing professionals in supporting these families is particularly relevant. Beyond clinical care, nurses play a key role in offering guidance, psychoeducational support, and coping resources. Recent evidence suggests that nurse-led or nurse-coordinated interventions, even in remote formats, can help improve parental competence and reduce stress levels [

26]. Professional accompaniment thus becomes a key element in fostering family adaptation and improving quality of life.

Overall, the findings of this study reinforce the need to promote policies and programmes aimed at improving the quality of life of individuals with ASD and their families, particularly in the economic, healthcare, and social support domains.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that a significant proportion of family caregivers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Huelva experience elevated levels of parental stress. This phenomenon appears to be linked to a lack of emotional support, adequate resources, and specific training to address the demands of caring for a child with special needs. Further research is therefore needed to explore these aspects in greater depth in order to offer more effective support to these families.

Gender differences were also observed in how caregivers cope with these situations. This finding underscores the importance of continuing to consider such differences in future research and in the design of support programmes.

Despite advances in understanding ASD, there remains a need to expand research on the factors influencing caregivers’ well-being and to assess the effectiveness of interdisciplinary interventions, particularly those led by nursing professionals.

Finally, the conclusions of this study contribute to updating the scientific literature on this topic and outline a potential roadmap that may serve as a basis for future studies and interventions aimed at reducing caregiver stress. Ultimately, if caregivers are well, they will provide better care, and when they provide better care, their relatives with ASD will receive a higher quality of support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.-N.; methodology, M.-d.-R.M.-L.; software, E.-I.M.-T.-d.-C.; validation, M.-d.-l.-A.M.-G. and F.-J.G.-V.; formal analysis, D.M.-N.; investigation, M.-d.-R.M.-L.; resources E.-I.M.-T.-d.-C.; data curation, M.-d.-l.-A.M.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.-J.G.-V.; writing—review and editing, D.M.-N.; visualization, M.-d.-R.M.-L.; supervision, F.-J.-G.-V.; project administration, M.-d.-l.-A.M.-G.; funding acquisition, E.-I.M.-T.-d.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Huelva Research Ethics Committee (reference no. SICEIA-2025-000320).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. Comprendiendo el estrés crónico, 2013. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/estres-cronico.

- Skinner, E.A., Edge, K., Altman, J. and Sherwood, H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol Bull.,2003, 129(2),216-69. [CrossRef]

- Autismo Madrid. El gasto familiar en la atención de las personas con TEA, 2015. https://autismomadrid.es.

- Lavado-Candelario, S. and Muñoz-Silva, A. Impacto en la familia del diagnóstico de Trastorno del espectro del autismo (TEA) en un hijo/a: una revisión sistemática. Análisis Mod Conducta, 2023, 49(180), 3-53. [CrossRef]

- Ángeles, A., & Fernández, L. Estrés parental en padres de niños con y sin trastornos del espectro autista. Revista Ecuatoriana de Psicología, 2024, 7(17), 66–70. https://repsi.org/index.php/repsi/article/view/160.

- Sánchez Pérez, A. El papel de la Enfermería en niños con Trastorno del Espectro Autista [Trabajo Fin de Grado, Universidad de Valladolid], 2016. http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/25113.

- Morera, L.P., Tempesti, T.C., Pérez, E., & Medrano, L.A. Biomarcadores en la medición del estrés: una revisión sistemática. Ansiedad y Estrés, 2019, 25(1), 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Celis Alcalá, G. and Ochoa Madrigal, M.G. Trastorno del espectro autista (TEA). Med Univ., 2022, 65(1),7-14. [CrossRef]

- Frías Plaza, A. Propuesta de actividades de Enfermería dirigida a padres de hijos con trastornos del espectro autista desde el enfoque de la consulta de Enfermería de salud mental en atención primaria [Trabajo Fin de Grado, Universidad de Alicante], 2018. http://hdl.handle.net/10045/76472.

- Smith, J.A., Brown, R.L., & Johnson, K.M. Conducting power analyses to determine sample sizes in quantitative research: A primer for technology education researchers. Journal of Technology Education, 2024, 35(2), 78-95. [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R.. Parenting Stress Index: Professional manual (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1995.

- Díaz-Herrero, Á., Brito de la Nuez, A.G., López-Pina, J.A., Pérez-López, J., & Martínez-Fuentes, M.T. Validación del Parenting Stress Index-Short Form en una muestra de padres españoles. Psicothema, 2010, 22(4), 1033–1038.

- Sánchez Griñán, G. Cuestionario de Estrés Parental: características psicométricas y análisis comparativo del estrés parental en padres de familia con hijos e hijas de 0 a 3 años de edad de Lima Moderna [Tesis de licenciatura, Universidad de Lima], 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pineda, D. Estrés parental y estilos de afrontamiento en padres de niños con trastornos del espectro autista (Tesis de licenciatura), 2012. http://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/.

- Mejía, M. Estresores relacionados con el cáncer, sentido de coherencia y estrés parental en madres de niños con leucemia que provienen del interior del país (Tesis de maestría), 2013. http://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/.

- Mendoza, X. Estrés parental y optimismo en padres de niños con trastorno del espectro autista (Tesis de licenciatura), 2014. http://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/.

- Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). Código de buenas prácticas, 2017. https://www.csic.es/es/el-csic/etica-e-integridad-cientifica-en-el-csic/integridad-cientifica-y-buenas-practicas#:~:text=Las%20buenas%20pr%C3%A1cticas%20cient%C3%ADficas%20son,que%20comporta%20la%20integridad%20cient%C3%ADfica.

- Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 6 de diciembre de 2018, 294, 119788-119857. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2018/12/05/3.

- Reglamento (UE) 2016/679, de 27 de abril, relativo a la protección de las personas físicas en lo que respecta al tratamiento de datos personales y a la libre circulación de estos datos y por el que se deroga la Directiva 95/46/CE (Reglamento general de protección de datos).

- León-Álvarez, M.A., Nuñez-Calderón, D.E., & Meléndez Jara, C.M. Estrés en padres de niños con TEA en tiempos de pandemia: un estudio de revisión. Revista Cubana de Salud Pública, 2023, 49(2), 406–416. https://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1990-86442023000200406&script=sci_arttext.

- Arphi Limo, Y. Relación entre el uso de estrategias de afrontamiento y nivel de estrés en padres con hijos autistas [Tesis de licenciatura en Psicología, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia], 2017. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12866/886.

- Canseco, L.M. and Vargas, P.D. Comprendiendo los niveles de ansiedad y los estilos de afrontamiento en cuidadores de niños con TEA. Rev Psicol Clín Salud Niños Adolesc., 2020, 7(1),23-35. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7770607.

- Bueno-Hernández, A., Cárdenas-Gutiérrez, M., Pastor-Zamalloa, M. and Silva-Mathews, Z. Experiencias de los padres ante el cuidado de su hijo autista. Rev Enferm Herediana, 2012, 5(1),26-35.

- Azar, R., and Solomon, C. Coping strategies of parents facing child diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Nurs., 2001, 16(6),418-28. [CrossRef]

- Webb Hooper, M., Nápoles, A.M., and Pérez-Stable, E.J. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA, 2020, 323(24):2466-7. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., Zhang, L., Wang, L., Li, Y., Wang, Y., & Wang, H. Enhancing autism care: The role of remote support in parental well-being and child development. World Journal of Psychiatry, 2025, 15(4), 102267–102278. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).