Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| “And I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within in you. |

| And I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh, |

| And give you a heart of flesh.” |

| (Holy Bible, English Standard Version, Ezekiel 36:26) |

2. Pathophysiology

3. Clinical Presentation

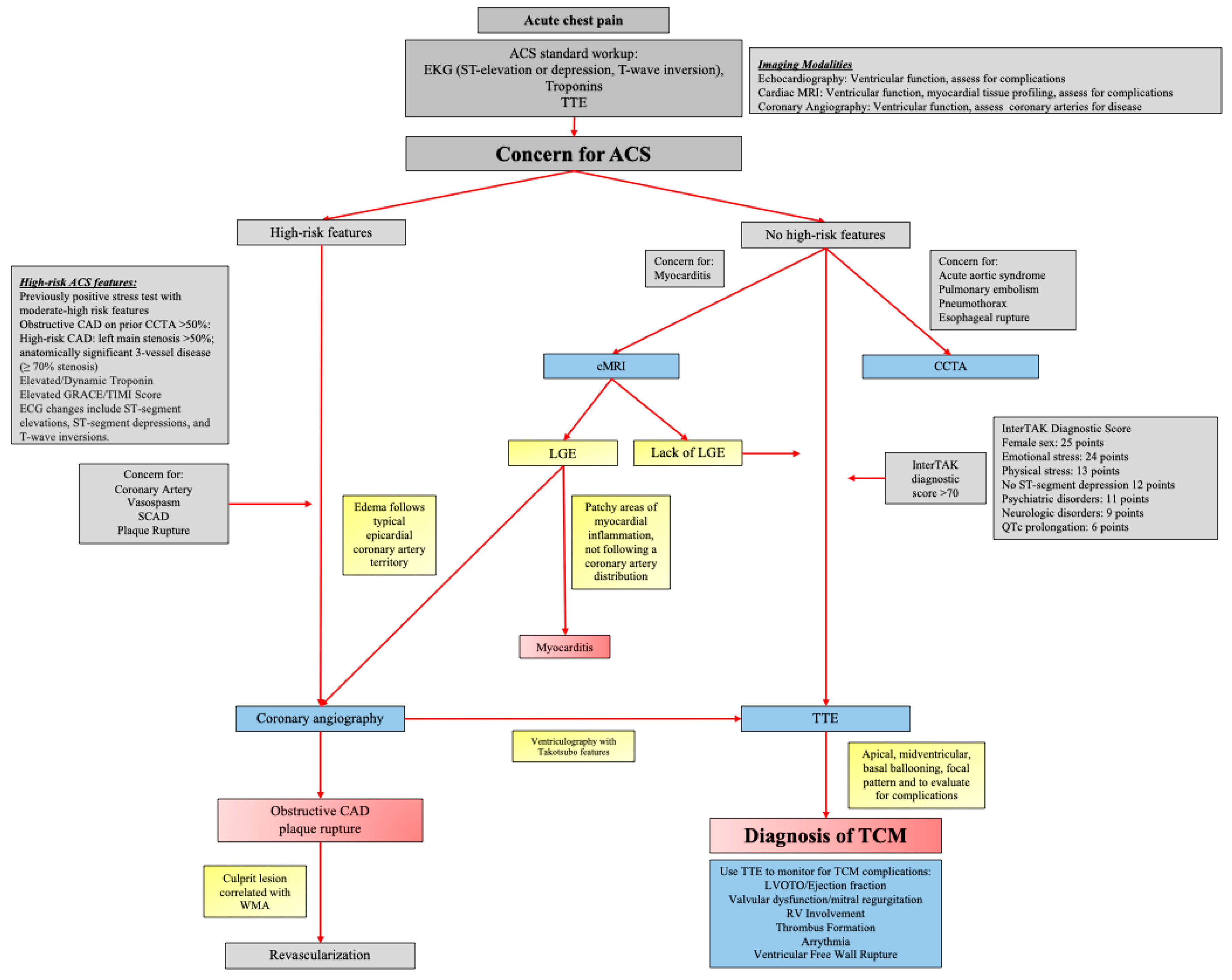

4. Assessment, Technology, and Diagnosis

5. Complications

5.1. Acute Heart Failure/Cardiogenic Shock

5.2. Hemodynamic Complications

- Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO)

- Valvular dysfunction

- Right ventricular involvement

- Thrombus formation

- Arrhythmias

- Ventricular free wall rupture

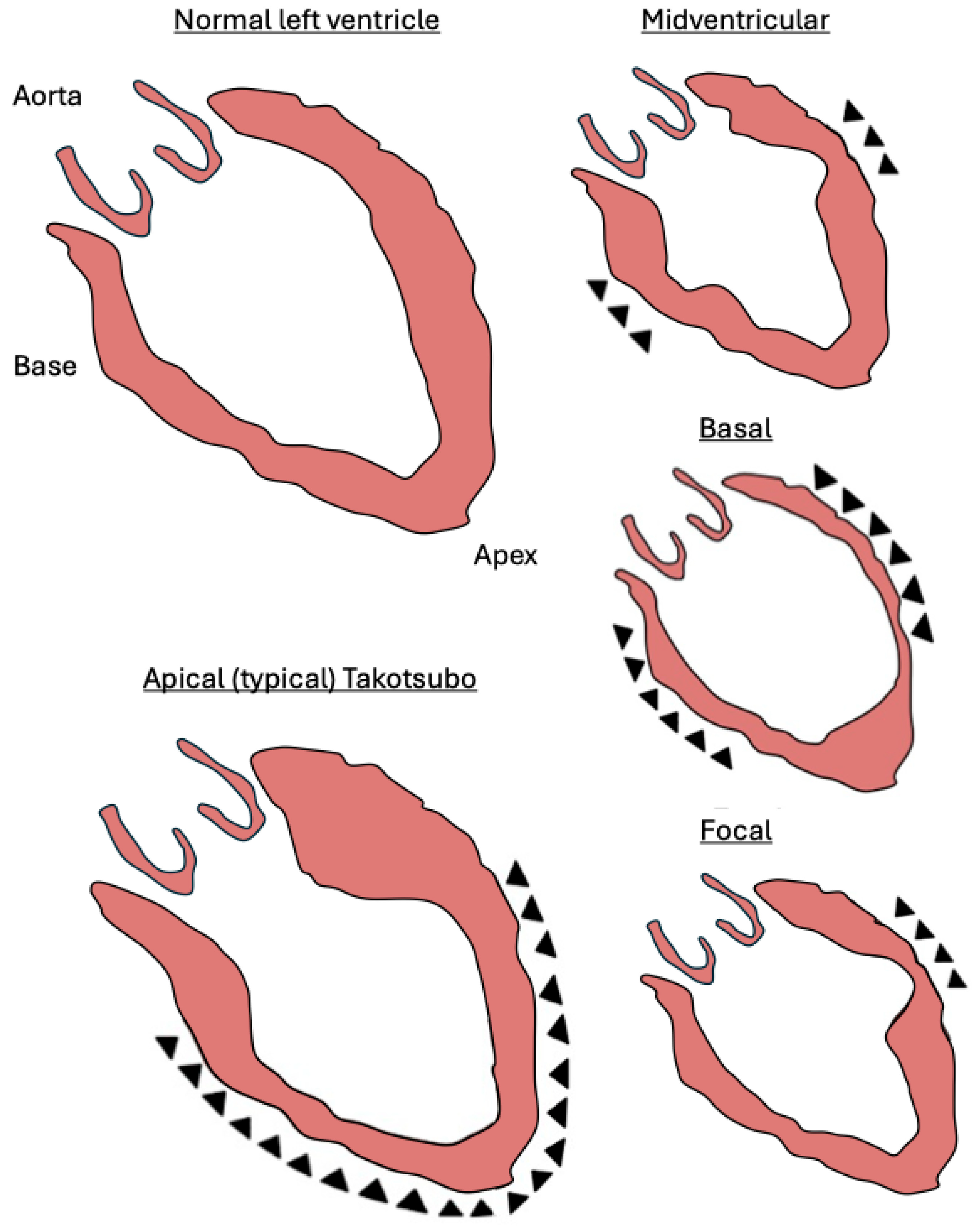

6. Takotsubo Variants

- Apical

- Midventricular

- Basal (reverse or inverted Takotsubo)

7. Prognosis

8. Limitations

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Templin, C.; Ghadri, J.R.; Diekmann, J.; Napp, L.C.; Bataiosu, D.R.; Jaguszewski, M.; Cammann, V.L.; Sarcon, A.; Geyer, V.; Neumann, C.A.; et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 373, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.; Sareen, P.; Ahmad, S.A.; Chhabra, L. Takotsubo syndrome: The past, the present and the future. World J Cardiol 2019, 11, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, B.T.; Choubey, R.; Novaro, G.M. Reduced estrogen in menopause may predispose women to takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Gender Medicine 2010, 7, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movahed, M.R.; Javanmardi, E.; Hashemzadeh, M. High Mortality and Complications in Patients Admitted With Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy With More Than Double Mortality in Men Without Improvement in Outcome Over the Years. Journal of the American Heart Association 2025, 0, e037219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchihashi, K.; Ueshima, K.; Uchida, T.; Oh-mura, N.; Kimura, K.; Owa, M.; Yoshiyama, M.; Miyazaki, S.; Haze, K.; Ogawa, H.; et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2001, 38, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction due to multivessel coronary spasm. Clinical aspect of myocardial injury: from ischemia to heart failure 1990, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dote, K.; Sato, H.; Tateishi, H.; Uchida, T.; Ishihara, M. [Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: a review of 5 cases]. J Cardiol 1991, 21, 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wittstein, I.S.; Thiemann, D.R.; Lima, J.A.C.; Baughman, K.L.; Schulman, S.P.; Gerstenblith, G.; Wu, K.C.; Rade, J.J.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Champion, H.C. Neurohumoral Features of Myocardial Stunning Due to Sudden Emotional Stress. New England Journal of Medicine 2005, 352, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Eisenhofer, G.; Kopin, I.J. Sources and significance of plasma levels of catechols and their metabolites in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003, 305, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfaj, E.; Nejat, A.; Haamid, A.; Espinosa, A.; Elmahdy, A.; Pylova, T.; Jha, S.; Redfors, B.; Omerovic, E. Temperature and repeated catecholamine surges modulate regional wall motion abnormalities in a rodent takotsubo syndrome model. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfaj, E.; Nejat, A.; Espinosa, A.S.; Hussain, S.; Haamid, A.; Soliman, A.E.; Kakaei, Y.; Jha, A.; Redfors, B.; Omerovic, E. Development of a small animal model replicating core characteristics of takotsubo syndrome in humans. European Heart Journal Open 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfors, B.; Ali, A.; Shao, Y.; Lundgren, J.; Gan, L.-M.; Omerovic, E. Different catecholamines induce different patterns of takotsubo-like cardiac dysfunction in an apparently afterload dependent manner. International Journal of Cardiology 2014, 174, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, A.; de Jong, M.C.; Varghese, S.; Lee, J.; Foo, R.; Parameswaran, R. A systematic cohort review of pheochromocytoma-induced typical versus atypical Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology 2023, 371, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiamanesh, O.; Vu, E.N.; Webber, D.L.; Lau, E.; Kapeluto, J.E.; Stuart, H.; Wood, D.A.; Wong, G.C. Pheochromocytoma-Induced Takotsubo Syndrome Treated With Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. JACC: Case Reports 2019, 1, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.L.; Chen, P.C.; Lee, C.C.; Chua, S.K. Adrenal pheochromocytoma presenting with Takotsubo-pattern cardiomyopathy and acute heart failure: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, T.; Khan, A.A.; Shabbir, R.W. Takotsubo syndrome with underlying pheochromocytoma. J Geriatr Cardiol 2021, 18, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, U.; El-Battrawy, I.; Fastner, C.; Behnes, M.; Sattler, K.; Huseynov, A.; Baumann, S.; Tülümen, E.; Borggrefe, M.; Akin, I. Clinical outcomes associated with catecholamine use in patients diagnosed with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasaki, S.; Kanaoka, K.; Nakai, M.; Sumita, Y.; Onoue, K.; Soeda, T.; Watanabe, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Saito, Y. Outcomes of catecholamine and/or mechanical support in Takotsubo syndrome. Heart 2022, 108, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, N.S. Formation of Aminochrome Leads to Cardiac Dysfunction and Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation Research 2018, 123, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.K.; Dhalla, K.S.; Shao, Q.; Beamish, R.E.; Dhalla, N.S. Differential changes in sympathetic activity in left and right ventricles in congestive heart failure after myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1997, 133, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P. Oxidative Products of Catecholamines During Heightened Sympathetic Activity Due to Congestive Heart Failure: Possible Role of Antioxidants. International Journal of General Medicine 2024, 17, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizanova, O.; Myslivecek, J.; Tillinger, A.; Jurkovicova, D.; Kubovcakova, L. Adrenergic and calcium modulation of the heart in stress: From molecular biology to function. Stress 2007, 10, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, L.H.; Walpoth, B.; Barsacchi, R. Calcium and catecholamines: relevance to cardiomyopathies and significance in therapeutic strategies. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1985, 17 Suppl 2, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, P.G. Signaling mechanisms of GPCR ligands. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 2008, 11, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Wang, S.-Q.; Yang, H.-Q. β-adrenergic regulation of Ca<sup>2+</sup> signaling in heart cells. Biophysics Reports 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izem-Meziane, M.; Djerdjouri, B.; Rimbaud, S.; Caffin, F.; Fortin, D.; Garnier, A.; Veksler, V.; Joubert, F.; Ventura-Clapier, R. Catecholamine-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction and mPTP opening: protective effect of curcumin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012, 302, H665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, N.; Münz, F.; Zink, F.; Gröger, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Wolfschmitt, E.-M.; Hogg, M.; Calzia, E.; Waller, C.; Radermacher, P.; et al. Relation of Plasma Catecholamine Concentrations and Myocardial Mitochondrial Respiratory Activity in Anesthetized and Mechanically Ventilated, Cardiovascular Healthy Swine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 17293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.M.; Boarescu, P.-M.; Bocsan, C.I.; Gherman, M.L.; Chedea, V.S.; Jianu, E.-M.; Roșian, Ș.H.; Boarescu, I.; Ranga, F.; Tomoiagă, L.L.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects of White Grape Pomace Polyphenols on Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Infarction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Ishikawa, S.; Kojima, S.; Hayashi, J.; Watanabe, Y.; Hoffman, J.I.; Okino, H. Increased responsiveness of left ventricular apical myocardium to adrenergic stimuli. Cardiovasc Res 1993, 27, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paur, H.; Wright, P.T.; Sikkel, M.B.; Tranter, M.H.; Mansfield, C.; O’Gara, P.; Stuckey, D.J.; Nikolaev, V.O.; Diakonov, I.; Pannell, L.; et al. High Levels of Circulating Epinephrine Trigger Apical Cardiodepression in a β<sub>2</sub>-Adrenergic Receptor/G<sub>i</sub>–Dependent Manner. Circulation 2012, 126, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Pepe, A.; Bacopoulou, F.; Lupi, A.; Quaia, E.; Chrousos, G.P.; Mavrogeni, S.I. Combined Brain–Heart Imaging in Takotsubo Syndrome: Towards a Holistic Patient Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Takanami, K.; Takase, K.; Shimokawa, H.; Yasuda, S. Reversible increase in stress-associated neurobiological activity in the acute phase of Takotsubo syndrome; a brain 18F-FDG-PET study. International Journal of Cardiology 2021, 344, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Gamble, D.T.; Rudd, A.; Mezincescu, A.M.; Abbas, H.; Noman, A.; Stewart, A.; Horgan, G.; Krishnadas, R.; Williams, C.; et al. Structural and Functional Brain Changes in Acute Takotsubo Syndrome. JACC: Heart Failure 2023, 11, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templin, C.; Hänggi, J.; Klein, C.; Topka, M.S.; Hiestand, T.; Levinson, R.A.; Jurisic, S.; Lüscher, T.F.; Ghadri, J.-R.; Jäncke, L. Altered limbic and autonomic processing supports brain-heart axis in Takotsubo syndrome. European Heart Journal 2019, 40, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Magalhães, R.; Arantes, C.; Moreira, P.S.; Rodrigues, M.; Marques, P.; Marques, J.; Sousa, N.; Pereira, V.H. Brain functional connectivity is altered in patients with Takotsubo Syndrome. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurisu, S.; Inoue, I.; Kawagoe, T.; Ishihara, M.; Shimatani, Y.; Nakama, Y.; Maruhashi, T.; Kagawa, E.; Dai, K.; Matsushita, J.; et al. Prevalence of incidental coronary artery disease in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Coronary Artery Disease 2009, 20, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.; Athanasiadis, A.; Schwab, J.; Pistner, W.; Gottwald, U.; Schoeller, R.; Toepel, W.; Winter, K.-D.; Stellbrink, C.; Müller-Honold, T.; et al. Complications in the clinical course of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology 2014, 176, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, H.; Honda, S.; Noguchi, M.; Sakai, C.; Harimoto, K.; Kawasaki, T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by acute coronary syndrome: A case report. J Cardiol Cases 2023, 28, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossone, E.; Lyon, A.; Citro, R.; Athanasiadis, A.; Meimoun, P.; Parodi, G.; Cimarelli, S.; Omerovic, E.; Ferrara, F.; Limongelli, G.; et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: an integrated multi-imaging approach. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging 2013, 15, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadri, J.-R.; Wittstein, I.S.; Prasad, A.; Sharkey, S.; Dote, K.; Akashi, Y.J.; Cammann, V.L.; Crea, F.; Galiuto, L.; Desmet, W.; et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Criteria, and Pathophysiology. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 2032–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stähli, B.E.; Schindler, M.; Schweiger, V.; Cammann, V.L.; Szawan, K.A.; Niederseer, D.; Würdinger, M.; Schönberger, A.; Schönberger, M.; Koleva, I.; et al. Cardiac troponin elevation and mortality in takotsubo syndrome: New insights from the international takotsubo registry. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2024, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, C.; Paduraru, L.; Balanescu, S. An Extensive Review on Imaging Diagnosis Methods in Takotsubo Syndrome. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine 2023, 24, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misumida, N.; Ogunbayo, G.O.; Kim, S.M.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Ziada, K.M.; Sorrell, V.L. Clinical Outcome of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Diagnosed With or Without Coronary Angiography. Angiology 2018, 70, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, S.; Nakajima, K.; Kinuya, S.; Yamagishi, M. Diagnostic utility of 123I-BMIPP imaging in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Journal of Cardiology 2014, 64, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangieh, A.H.; Obeid, S.; Ghadri, J.R.; Imori, Y.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Kovac, M.; Ruschitzka, F.; Lüscher, T.F.; Duru, F.; Templin, C.; et al. ECG Criteria to Differentiate Between Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy and Myocardial Infarction. Journal of the American Heart Association 2016, 5, e003418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadri, J.-R.; Wittstein, I.S.; Prasad, A.; Sharkey, S.; Dote, K.; Akashi, Y.J.; Cammann, V.L.; Crea, F.; Galiuto, L.; Desmet, W.; et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part II): Diagnostic Workup, Outcome, and Management. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 2047–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitel, I.; von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff, F.; Bernhardt, P.; Carbone, I.; Muellerleile, K.; Aldrovandi, A.; Francone, M.; Desch, S.; Gutberlet, M.; Strohm, O.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Findings in Stress (Takotsubo) Cardiomyopathy. JAMA 2011, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zghyer, F.; Botheju, W.S.P.; Kiss, J.E.; Michos, E.D.; Corretti, M.C.; Mukherjee, M.; Hays, A.G. Cardiovascular Imaging in Stress Cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo Syndrome). Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amicone, S.; Impellizzeri, A.; Tattilo, F.P.; Ryabenko, K.; Asta, C.; Belà, R.; Suma, N.; Canton, L.; Fedele, D.; Bertolini, D.; et al. Noninvasive Assessment in Takotsubo Syndrome: A Diagnostic Challenge. Echocardiography 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayar, J.; John, K.; Philip, A.; George, L.; George, A.; Lal, A.; Mishra, A. A Review of Nuclear Imaging in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy. Life 2022, 12, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.L.; Horne, B.D.; Le, V.T.; Bair, T.L.; Min, D.B.; Minder, C.M.; Dhar, R.; Mason, S.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Knowlton, K.U. Spectrum of radionuclide perfusion study abnormalities in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology 2022, 29, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.E.; Ahtarovski, K.A.; Bang, L.E.; Holmvang, L.; Søholm, H.; Ghotbi, A.A.; Andersson, H.; Vejlstrup, N.; Ihlemann, N.; Engstrøm, T.; et al. Basal hyperaemia is the primary abnormality of perfusion in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a quantitative cardiac perfusion positron emission tomography study. European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging 2015, 16, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylecka, M.; Budnik, M.; Kochanowski, J.; Piątkowski, R.; Wojtera, K.; Chojnowski, M.; Peller, M.; Fronczewska-Wieniawska, K.; Mazurek, T.; Mączewska, J.; et al. Diagnostic utility of hybrid single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography imaging in patients with Takotsubo syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, G.; Pizzuto, C.; Barbaro, G.; Sutera, L.; Incalcaterra, E.; Evola, G.; Azzarelli, S.; Palecek, T.; Di Gesaro, G.; Cascio, C.; et al. Chronic pharmacological treatment in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology 2008, 127, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposeiras-Roubin, S.; Santoro, F.; Arcari, L.; Vazirani, R.; Novo, G.; Uribarri, A.; Enrica, M.; Lopez-Pais, J.; Guerra, F.; Alfonso, F.; et al. Beta-Blockers and Long-Term Mortality in Takotsubo Syndrome: Results of the Multicenter GEIST Registry. JACC: Heart Failure 2025, 13, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mahmoud, R.; Mansencal, N.; Pilliére, R.; Leyer, F.; Abbou, N.; Michaud, P.; Nallet, O.; Digne, F.; Lacombe, P.; Cattan, S.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in Tako-Tsubo syndrome. American Heart Journal 2008, 156, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Nagao, K.; Kyuma, M.; Ooiwa, H.; Nozawa, A.; Shimoshige, S.; Eguchi, M.; Wakabayashi, T.; et al. Clinical implications of midventricular obstruction and intravenous propranolol use in transient left ventricular apical ballooning (Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy). American Heart Journal 2008, 155, 526.e521–526.e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, F.; Ieva, R.; Ferraretti, A.; Fanelli, M.; Musaico, F.; Tarantino, N.; Martino, L.D.; Gennaro, L.D.; Caldarola, P.; Biase, M.D.; et al. Hemodynamic Effects, Safety, and Feasibility of Intravenous Esmolol Infusion During Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy With Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction: Results From A Multicenter Registry. Cardiovascular Therapeutics 2016, 34, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, F.; Stiermaier, T.; Tarantino, N.; De Gennaro, L.; Moeller, C.; Guastafierro, F.; Marchetti, M.F.; Montisci, R.; Carapelle, E.; Graf, T.; et al. Left Ventricular Thrombi in Takotsubo Syndrome: Incidence, Predictors, and Management: Results From the GEIST (German Italian Stress Cardiomyopathy) Registry. Journal of the American Heart Association 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kaushik, S.; Nautiyal, A.; Choudhary, S.K.; Kayastha, B.L.; Mostow, N.; Lazar, J.M. Cardiac Rupture in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review. Clinical Cardiology 2011, 34, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; Bossone, E.; Schneider, B.; Sechtem, U.; Citro, R.; Underwood, S.R.; Sheppard, M.N.; Figtree, G.A.; Parodi, G.; Akashi, Y.J.; et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Heart Failure 2016, 18, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallaoui, N.; Wang, Z.; Lecomte, M.; Ennezat, P.V.; Blanchard, D. Acute mitral regurgitation in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care 2015, 4, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citro, R.; Rigo, F.; D’Andrea, A.; Ciampi, Q.; Parodi, G.; Provenza, G.; Piccolo, R.; Mirra, M.; Zito, C.; Giudice, R.; et al. Echocardiographic Correlates of Acute Heart Failure, Cardiogenic Shock, and In-Hospital Mortality in Tako-Tsubo Cardiomyopathy. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2014, 7, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, H.; Akiba, H.; Inagawa, H.; Okada, Y. Isolated right ventricular takotsubo cardiomyopathy presenting as acute right ventricular failure: A case report. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiyama, N.; Okura, H.; Tamada, T.; Imai, K.; Yamada, R.; Kume, T.; Hayashida, A.; Neishi, Y.; Kawamoto, T.; Yoshida, K. Impact of right ventricular involvement on the prognosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging 2016, 17, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Battrawy, I.; Santoro, F.; Stiermaier, T.; Möller, C.; Guastafierro, F.; Novo, G.; Novo, S.; Mariano, E.; Romeo, F.; Romeo, F.; et al. Incidence and Clinical Impact of Right Ventricular Involvement (Biventricular Ballooning) in Takotsubo Syndrome: Results From the GEIST Registry. Chest 2021, 160, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurisu, S.; Inoue, I.; Kawagoe, T.; Ishihara, M.; Shimatani, Y.; Nakama, Y.; Maruhashi, T.; Kagawa, E.; Dai, K. Incidence and treatment of left ventricular apical thrombosis in Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology 2011, 146, e58–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, G.N.; Mcevoy, J.W.; Fang, J.C.; Ibeh, C.; Mccarthy, C.P.; Misra, A.; Shah, Z.I.; Shenoy, C.; Spinler, S.A.; Vallurupalli, S.; et al. Management of Patients at Risk for and With Left Ventricular Thrombus: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isogai, T.; Matsui, H.; Tanaka, H.; Makito, K.; Fushimi, K.; Yasunaga, H. Incidence, management, and prognostic impact of arrhythmias in patients with Takotsubo syndrome: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care 2023, 12, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, S.; Deshmukh, A.; Mehta, K.; Badheka, A.O.; Tuliani, T.; Patel, N.J.; Dabhadkar, K.; Prasad, A.; Paydak, H. Burden of arrhythmias in patients with Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (Apical Ballooning Syndrome). International Journal of Cardiology 2013, 170, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Battrawy, I.; Lang, S.; Ansari, U.; Tülümen, E.; Schramm, K.; Fastner, C.; Zhou, X.; Hoffmann, U.; Borggrefe, M.; Akin, I. Prevalence of malignant arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in takotsubo syndrome and its management. EP Europace 2018, 20, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.H.; Trohman, R.G.; Madias, C. Arrhythmias in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Cardiac Electrophysiology Clinics 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiermaier, T.; Rommel, K.-P.; Eitel, C.; Möller, C.; Graf, T.; Desch, S.; Thiele, H.; Eitel, I. Management of arrhythmias in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Is the implantation of permanent devices necessary? Heart Rhythm 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguszewski, M.; Fijalkowski, M.; Nowak, R.; Czapiewski, P.; Ghadri, J.-R.; Templin, C.; Rynkiewicz, A. Ventricular rupture in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal 2012, 33, 1027–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskander, M.; Abugroun, A.; Shehata, K.; Iskander, F.; Iskander, A. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy-Induced Cardiac Free Wall Rupture: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cardiology Research 2018, 9, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribarri, A.; Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Conty, D.A.; Vedia, O.; Almendro-Delia, M.; Duran Cambra, A.; Martin-Garcia, A.C.; Barrionuevo-Sánchez, M.; Martínez-Sellés, M.; Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Prognosis of Patients With Takotsubo Syndrome Based on Different Triggers: Importance of the Physical Nature. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e013701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, R.T.; Askew, J.W.; Reuss, C.S.; Lee, R.W.; Sweeney, J.P.; Fortuin, F.D.; Oh, J.K.; Tajik, A.J. Transient Midventricular Ballooning Syndrome: A New Variant. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2006, 48, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaraj, R.; Movahed, M.R. Reverse or Inverted Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (Reverse Left Ventricular Apical Ballooning Syndrome) Presents at a Younger Age Compared With the Mid or Apical Variant and Is Always Associated With Triggering Stress. Congestive Heart Failure 2010, 16, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, H.H.; McNeal, A.R.; Goyal, H. Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive review. Ann Transl Med 2018, 6, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citro, R.; Rigo, F.; Previtali, M.; Ciampi, Q.; Canterin, F.A.; Provenza, G.; Giudice, R.; Patella, M.M.; Vriz, O.; Mehta, R.; et al. Differences in Clinical Features and In-Hospital Outcomes of Older Adults with Tako-Tsubo Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2012, 60, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinjikji, W.; El-Sayed, A.M.; Salka, S. In-hospital mortality among patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A study of the National Inpatient Sample 2008 to 2009. American Heart Journal 2012, 164, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, V.; Nazari, R.; Senobari, N.; Alirezaei, A.; Akbari, T.; Nasrollahizadeh, A.; Ebrahimi, P.; Ahmed, R.; Khan, S.Q.; Shahid, F. Stress-Induced Cardiomyopathy Following Kidney Transplant. JACC: Case Reports 2025, 30, 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusnina, W.; Elhouderi, E.; Walters, R.W.; Al-Abdouh, A.; Mostafa, M.R.; Liu, J.L.; Mazozy, R.; Mhanna, M.; Ben-Dor, I.; Dufani, J.; et al. Sex Differences in the Clinical Outcomes of Patients With Takotsubo Stress Cardiomyopathy: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. The American Journal of Cardiology 2024, 211, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Zuo, X.; Li, Q.; Sherif, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Dong, M.; et al. Takotsubo syndrome and respiratory diseases: a systematic review. European Heart Journal Open 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Almendro-Delia, M.; Andrés, M.; Sionis, A.; Martin, A.; Bastante, T.; Córdoba-Soriano, J.G.; Linares, J.A.; González Sucarrats, S.; Sánchez-Grande-Flecha, A.; et al. Secondary forms of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A whole different prognosis. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care 2016, 5, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, A.E.; Horgan, G.W.; McGowan, J.; Sood, A.; McGeoch, R.; Irving, J.; Watt, J.; Leslie, S.J.; Petrie, M.C.; Lang, C.C.; et al. Morbidity After Takotsubo Syndrome: A Report From the Scottish Takotsubo Registry. Annals of Internal Medicine 2025, 178, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looi, J.-L.; Easton, A.; Webster, M.; To, A.; Lee, M.; Kerr, A.J. Recurrent Takotsubo Syndrome: How Frequent, and How Does It Present? Heart, Lung and Circulation 2024, 33, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Ishigaki, T.; Toyoshima, M.; Katawaki, W.; Toshima, T.; Takahashi, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Watanabe, M. Recurrent Takotsubo Syndrome Presenting with Different Ballooning Patterns and Electrocardiographic Abnormalities. Internal Medicine 2023, 62, 2977–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Battrawy, I.; Santoro, F.; Stiermaier, T.; Möller, C.; Guastafierro, F.; Novo, G.; Novo, S.; Mariano, E.; Romeo, F.; Romeo, F.; et al. Incidence and Clinical Impact of Recurrent Takotsubo Syndrome: Results From the GEIST Registry. Journal of the American Heart Association 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Carson, K.; Usmani, Z.; Sawhney, G.; Shah, R.; Horowitz, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence and correlates of recurrence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology 2014, 174, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadri, J.R.; Jaguszewski, M.; Corti, R.; Lüscher, T.F.; Templin, C. Different wall motion patterns of three consecutive episodes of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the same patient. International Journal of Cardiology 2012, 160, e25–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Jamhour, K.; Abu-Assi, E.; Conty, D.A.; Vedia, O.; Almendro-Delia, M.; Sionis, A.; Martin-Garcia, A.C.; Corbí-Pascual, M.; et al. Long-term prognostic impact of beta-blockers in patients with Takotsubo syndrome: Results from the RETAKO Registry. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia 2023, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Complication | Frequency | Diagnostic Clues | Onset Timing | Clinical Presentation | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Heart failure | 12-45% | CXR, echo, clinical exam | Acute | Dyspnea, pulmonary edema | Diuretics, oxygen, supportive therapy |

| LVOTO | 10-25% | Echo, hypotension, low cardiac output | Acute | Hypotension. systolic murmur | Inotropes, vasopressors, mechanical support if needed |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 6-20% | Echo with Doppler, hypotension | Acute | Hypotension, systolic murmur, poor perfusion | Beta-blockers, avoid inotropes, |

| Valvular Dysfunction | 19-25% | Echo (MR), auscultation | Acute | Dyspnea, murmur | Afterload reduction, manage MR supportively |

| RV Involvement | 11-34% | Echo, RV dilation or dysfunction | Acute | Hypotension, right-sided heart failure signs | Supportive care, monitor RV function |

| LV Thrombus | 1.3–8% | Echo, cardiac MRI | Subacute | Stroke or embolic signs | Anticoagulation, imaging surveillance |

| Arrhythmias: VT, VF and SCA, atrial fibrillation, bradyarrhythmias | AFib: 5-15% VT/VFs:4-9% Bradyarrhythmias: 2-5% |

EKG, telemetry | Acute | Palpitations, syncope, arrest | Rate/rhythm control, defibrillation if unstable, ICD in certain patients |

| Ventricular Free Wall Rupture | <1% | Echo, pericardial effusion | Acute | Sudden cardiovascular collapse, tamponade | Emergency pericardiocentesis, surgery |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).