Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

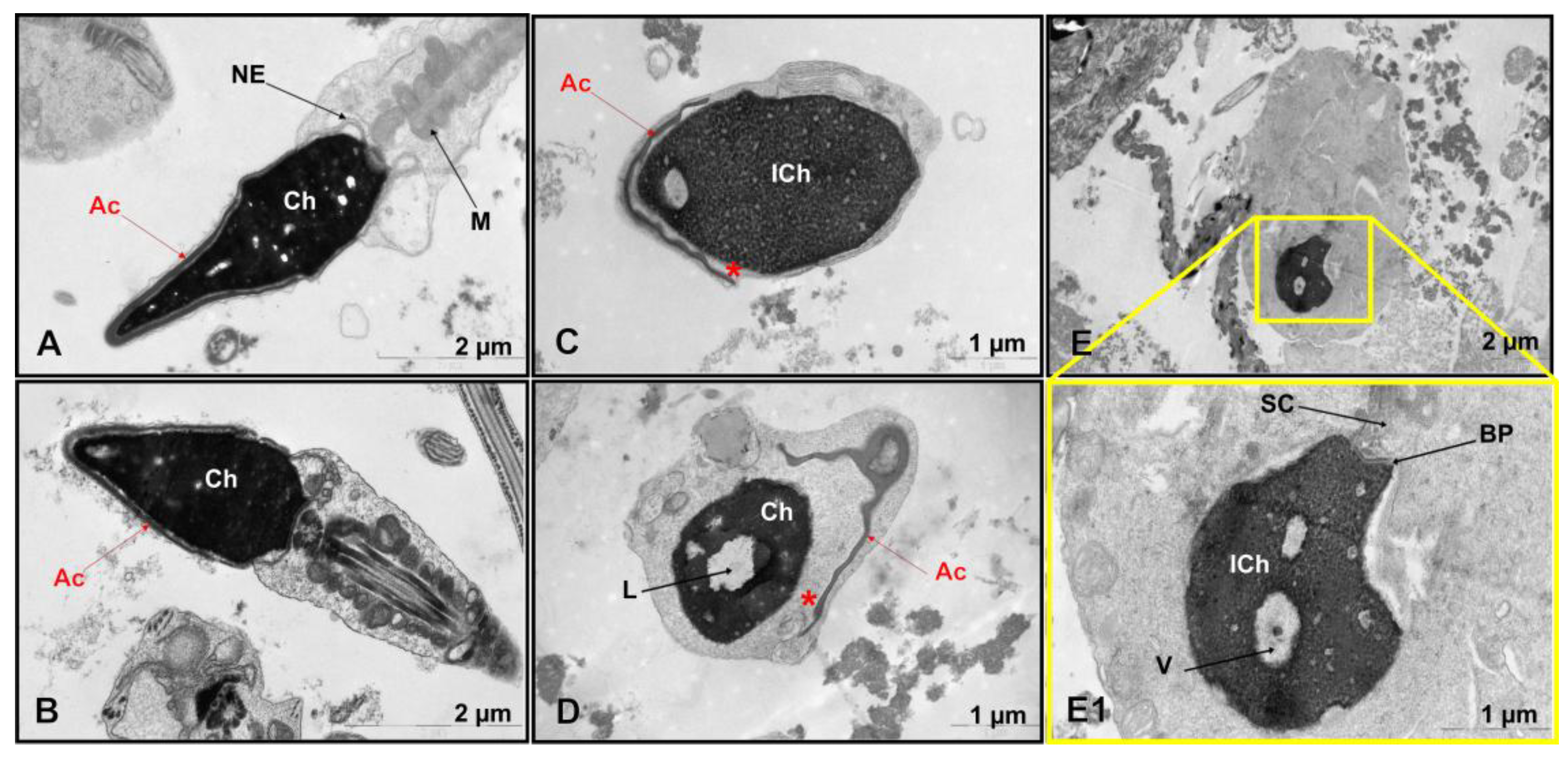

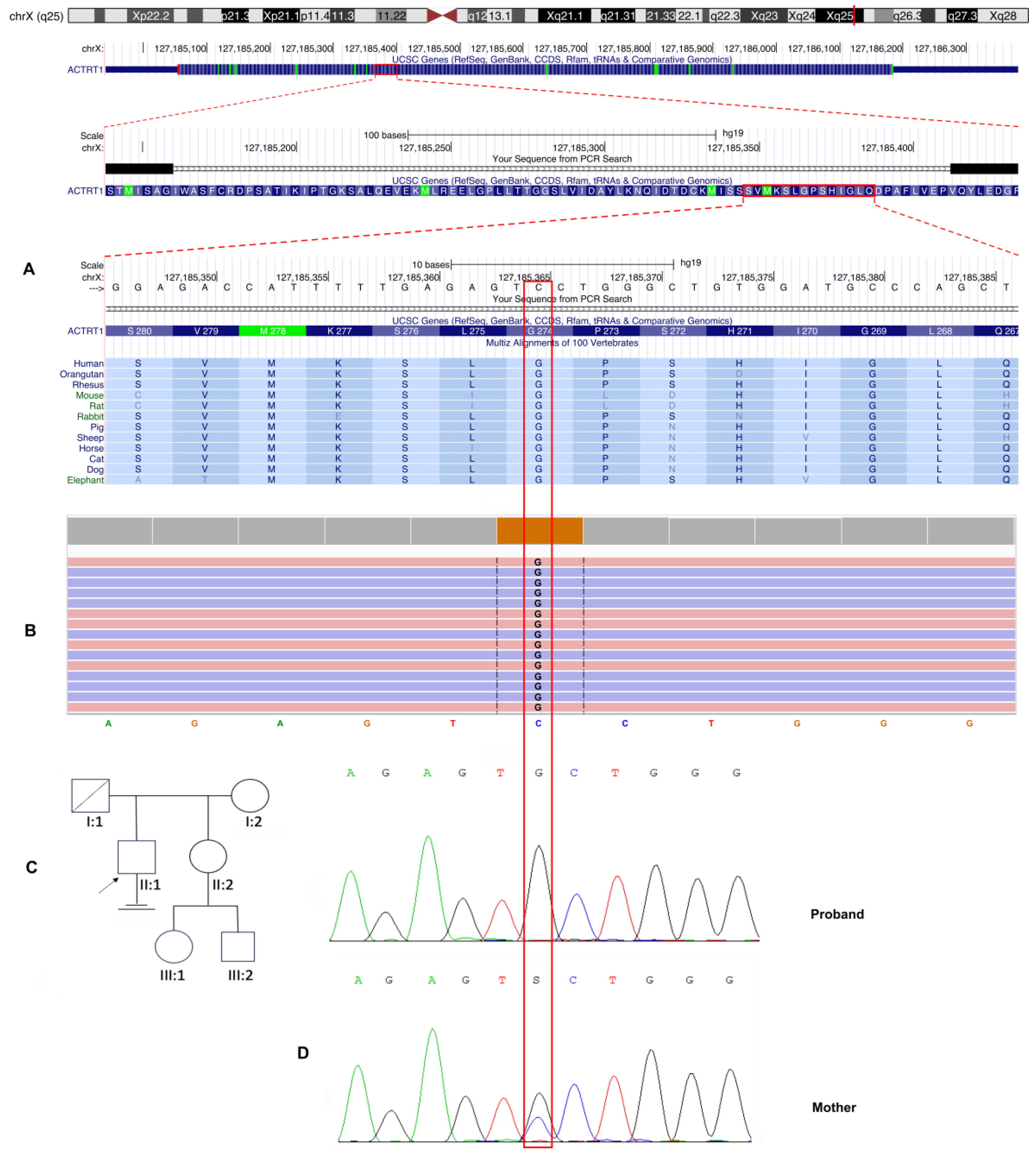

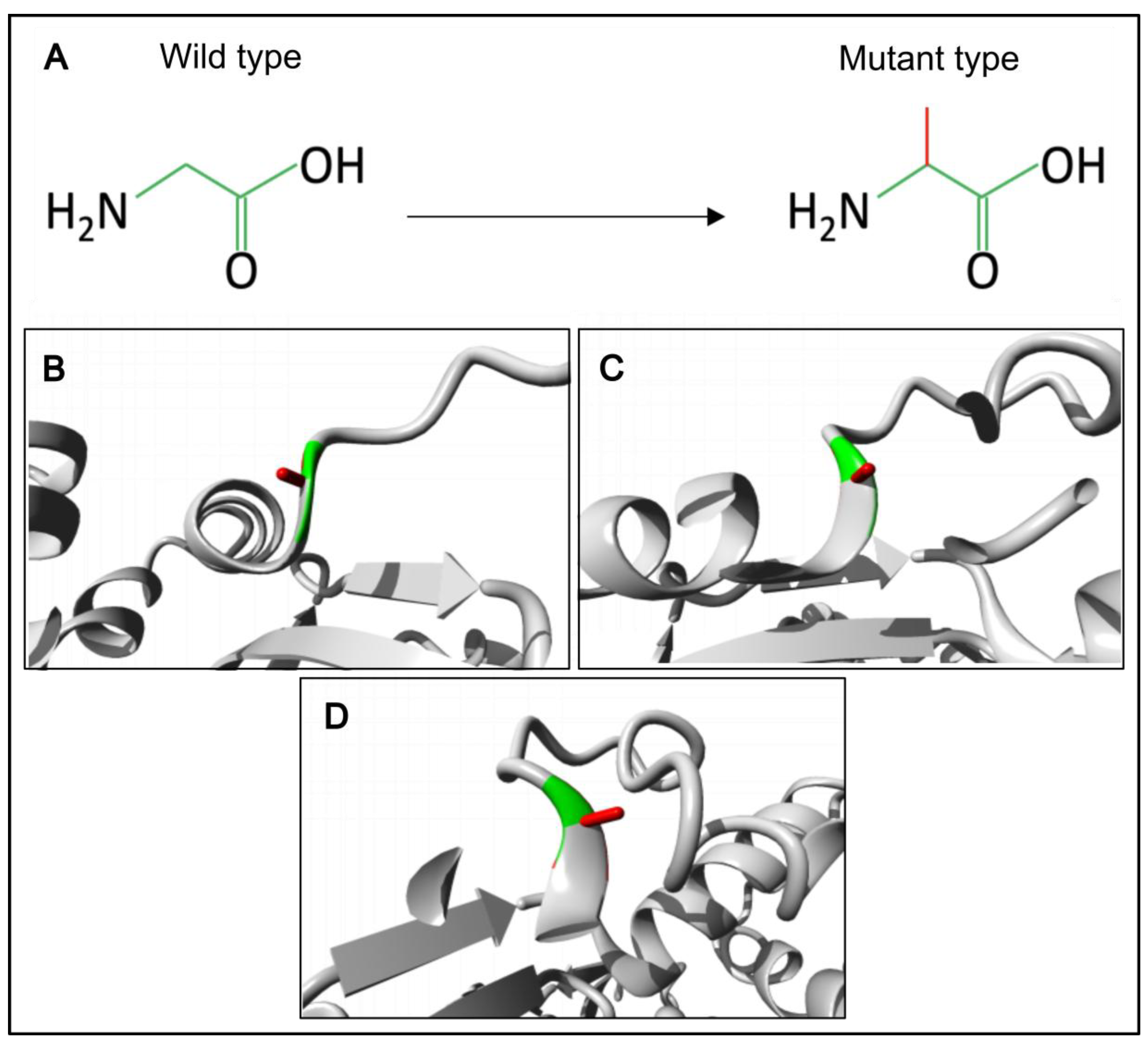

Background: Male infertility is a common reproductive disorder, affecting about 7% of men in the general population. Despite its prevalence, the cause of infertility is often unknown. This case report presents the results of a comprehensive evaluation of a patient with severe oligoteratozoospermia and primary infertility. Methods: The patient underwent clinical, andrological, and genetic examinations, including semen analysis, transmission electron microscopy, cytogenetic examination, molecular analysis of the AZF locus and the CFTR gene, whole exome sequencing and Sanger sequencing. Results: Semen analysis revealed severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Transmission electron microscopy showed acrosome detachment from the nucleus in 49% of the spermatozoa. A high percentage of spermatozoa with insufficiently condensed ("immature") chromatin (54%) was also observed. No chromosomal abnormalities, Y chromosome microdeletions, or pathogenic CFTR gene variants were identified. Whole exome sequencing revealed a novel c.821G>C variant (chrX:127185365G>C; NM_138289.4) in the ACTRT1 gene (Xq25). This variant was hemizygous in the patient and heterozygous in his mother, as determined by Sanger sequencing. According to the ACMG guidelines (PM2, PP3), this missense variant in the ACTRT1 gene was classified as a variant of uncertain clinical significance (VUS). Amino acid conservation and 3D protein modeling predict that the identified variant has a deleterious effect on the protein. Conclusions: This study demonstrates that hemizygous variants of the ACTRT1 gene can cause X-linked specific teratozoospermia characterized by acrosome detachment from the sperm nucleus. These findings underscore the importance of genetic testing for infertile men with specific morphological abnormalities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient

2.2. Standard Semen Examination

2.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.4. Isolation of Genomic DNA

2.5. Whole Exome Sequencing

2.6. Sanger Sequencing

2.7. In Silico Pathogenicity Prediction and Structural Analysis of Detected Variant

3. Results

3.1. Semen Analysis

3.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

3.3. Molecular Genetic, Segregation and Bioinformatic Study Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AZF | AZoospermia Factor |

| CFTR | Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator |

| PT | Perinuclear Theca |

| SAR | SubAcrosomal Region |

| PAR | PostAcrosomal Region |

| FSH | Follicle Stimulating Hormone |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

| IGV | Integrative Genome Viewer |

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| sOT | severe OligoTeratozoospermia |

| sOAT | Severe OligoAsthenoTeratozoospermia |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| OMIM | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man |

| gnomAD | genome Aggregation Database |

| PLCζ | Phospholipase C Zeta |

| ASS | Acephalic Sperm Syndrome |

| HTCA | Head-Tail Coupling Apparatus |

| BDS | Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome |

| AOA | Assisted Oocyte Activation |

References

- Krausz, C. Male Infertility: Pathogenesis and Clinical Diagnosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 25, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, B.J.; Riera-Escamilla, A.; Wyrwoll, M.J.; Salas-Huetos, A.; Xavier, M.J.; Nagirnaja, L.; Friedrich, C.; Conrad, D.F.; Aston, K.I.; Krausz, C.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Validated Monogenic Causes of Human Male Infertility: 2020 Update and a Discussion of Emerging Gene–Disease Relationships. Hum Reprod Update 2021, 28, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, H.; Shimada, K.; Kaneda, Y.; Ikawa, M. Development of Functional Spermatozoa in Mammalian Spermiogenesis. Development 2024, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Chen, W.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, S.; He, J.; Han, L.; He, Z.; Qin, W. Novel Gene Regulation in Normal and Abnormal Spermatogenesis. Cells 2021, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oko, R.; Sutovsky, P. Biogenesis of Sperm Perinuclear Theca and Its Role in Sperm Functional Competence and Fertilization. J Reprod Immunol 2009, 83, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oko, R. Developmental Expression and Possible Role of Perinuclear Theca Proteins in Mammalian Spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil Dev 1995, 7, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, F.J.; Cook, S. Formation of the Perinuclear Theca in Spermatozoa of Diverse Mammalian Species: Relationship of the Manchette and Multiple Band Polypeptides. Mol Reprod Dev 1991, 28, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Kovacevic, A.; Mayer, M.; Dicke, A.-K.; Arévalo, L.; Koser, S.A.; Hansen, J.N.; Young, S.; Brenker, C.; Kliesch, S.; et al. Cylicins Are a Structural Component of the Sperm Calyx Being Indispensable for Male Fertility in Mice and Human. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oko, R.; Maravei, D. Protein Composition of the Perinuclear Theca of Bull Spermatozoa1. Biol Reprod 1994, 50, 1000–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, H.W.; Figge, U.; Winter, S.; Kuhn, C.; Zimbelmann, R.; Franke, W.W. Novel Actin-Related Proteins Arp-T1 and Arp-T2 as Components of the Cytoskeletal Calyx of the Mammalian Sperm Head. Exp Cell Res 2002, 279, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-Z.; Wei, L.-L.; Zhang, X.-H.; Jin, H.-J.; Chen, S.-R. Loss of Perinuclear Theca ACTRT1 Causes Acrosome Detachment and Severe Male Subfertility in Mice. Development 2022, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jin, H.; Long, S.; Tang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Han, W.; Liao, H.; Fu, T.; Huang, G.; et al. Deletion of ACTRT1 Is Associated with Male Infertility as Sperm Acrosomal Ultrastructural Defects and Fertilization Failure in Human. Hum Reprod 2024, 39, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Jia, W.; Hou, M.; Zhang, X. Actl7a Deficiency in Mice Leads to Male Infertility and Fertilization Failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 623, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeb, A.; Ma, A.; Chen, J.; Zhao, D.; Rahim, F.; Khan, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A Recessive ACTL7A Founder Variant Leads to Male Infertility Due to Acrosome Detachment in Pakistani Pashtuns. Clin Genet 2023, 104, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Gong, F.; Lu, G.; Zheng, W.; Lin, G. Pathogenic Variant in ACTL7A Causes Severe Teratozoospermia Characterized by Bubble-Shaped Acrosomes and Male Infertility. Mol Hum Reprod 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xi, Q.; Jia, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Luo, G.; Xing, C.; Zhang, D.; Hou, M.; Liu, H.; et al. A Novel Homozygous Mutation in ACTL7A Leads to Male Infertility. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2023, 298, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cui, Y.; Guo, S.; Liu, B.; Bian, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H. Novel Variants in ACTL7A and PLCZ1 Are Associated with Male Infertility and Total Fertilization Failure. Clin Genet 2023, 103, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, A.; Qu, R.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Tao, C.; Fu, J.; Tang, J.; Ru, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Disruption in ACTL7A Causes Acrosomal Ultrastructural Defects in Human and Mouse Sperm as a Novel Male Factor Inducing Early Embryonic Arrest. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaaz4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Lin, Y.; Cai, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Yang, X. Novel Bi-Allelic Variants in ACTL7A Are Associated with Male Infertility and Total Fertilization Failure. Hum Reprod 2021, 36, 3161–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Long, R.; Jin, H.; Gao, L.; Zhu, L.; Jin, L. Novel ACTL7A Variants in Males Lead to Fertilization Failure and Male Infertility. Andrology 2025, 13, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gong, F.; Lu, G.; Lin, G.; Dai, J. Homozygous ACTL9 Mutations Cause Irregular Mitochondrial Sheath Arrangement and Abnormal Flagellum Assembly in Spermatozoa and Male Infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet 2024, 41, 2271–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Cheng, X.; Xiong, Y.; Li, K. Gene Mutations Associated with Fertilization Failure after in Vitro Fertilization/Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhang, T.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Q.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, L.; Zong, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Homozygous Pathogenic Variants in ACTL9 Cause Fertilization Failure and Male Infertility in Humans and Mice. Am J Hum Genet 2021, 108, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaei, R.; Eslami, M.; Dadfar, M.; Saberi, A. Identification of a New Mutation in the ACTL9 Gene in Men with Unexplained Infertility. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2024, 12, e2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajar, A.; Forti, G.; O’Neill, T.W.; Lee, D.M.; Silman, A.J.; Finn, J.D.; Bartfai, G.; Boonen, S.; Casanueva, F.F.; Giwercman, A.; et al. Characteristics of Secondary, Primary, and Compensated Hypogonadism in Aging Men: Evidence from the European Male Ageing Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. 2010, 271.

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venselaar, H.; Te Beek, T.A.H.; Kuipers, R.K.P.; Hekkelman, M.L.; Vriend, G. Protein Structure Analysis of Mutations Causing Inheritable Diseases. An e-Science Approach with Life Scientist Friendly Interfaces. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSabbagh, M.M.; Baqi, M.A. Bazex-Dupré-Christol Syndrome: Review of Clinical and Molecular Aspects. Int J Dermatol 2018, 57, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-S.; Papanastasi, E.; Blanchard, G.; Chiticariu, E.; Bachmann, D.; Plomann, M.; Morice-Picard, F.; Vabres, P.; Smahi, A.; Huber, M.; et al. ARP-T1-Associated Bazex-Dupré-Christol Syndrome Is an Inherited Basal Cell Cancer with Ciliary Defects Characteristic of Ciliopathies. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Banka, S.; Huang, Y.; Hardman-Smart, J.; Pye, D.; Torrelo, A.; Beaman, G.M.; Kazanietz, M.G.; Baker, M.J.; Ferrazzano, C.; et al. Germline Intergenic Duplications at Xq26.1 Underlie Bazex–Dupré–Christol Basal Cell Carcinoma Susceptibility Syndrome. British Journal of Dermatology 2022, 187, 948–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Ge, S.; Dai, Y.; Ping, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing of a Large Chinese Azoospermia and Severe Oligospermia Cohort Identifies Novel Infertility Causative Variants and Genes. Hum Mol Genet 2020, 29, 2451–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Serafimovski, M.; Isachenko, V.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X. Pathogenic Variants in ACTRT1 Cause Acephalic Spermatozoa Syndrome. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 676246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yin, Z.; Ni, B.; Lin, J.; Luo, S.; Xie, W. Whole Exome Sequencing Analysis of 167 Men with Primary Infertility. BMC Med Genomics 2024, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Gene variant | Phenotype/additional data | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOA54 | c.662A>G, p.(Tyr221Cys) | NOA with meiotic arrest. Normal male karyotype (46,XY) without AZF microdeletions; normal endocrine profile (FSH, LH, total testosterone) and testis volume | S. Chen et al., 2020 [32] |

| NOA281 | c.431C>T, p.(Ala144Val) | ||

| F018 | c.95G>A, p.(Arg32His) | Asthenoteratozoospermia, ASS | Y. Sha et al., 2021 [33] |

| F034 | c.662A>G, p.(Tyr221Cys) | ||

| L053 | 110-kb deletion | sOT; acrosome detachment, fertilization failure | Q. Zhang et al., 2024 [12] |

| L116 | |||

| M1555 | c.169G>A, p.(Val157Met) | OAT. Normal male karyotype (46,XY), no AZF microdeletions | H. Zhou et al., 2024 [34] |

| Present | c.821G>C, p.(Gly274Ala) | sOAT; acrosome detachment, fertilization failure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).