Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

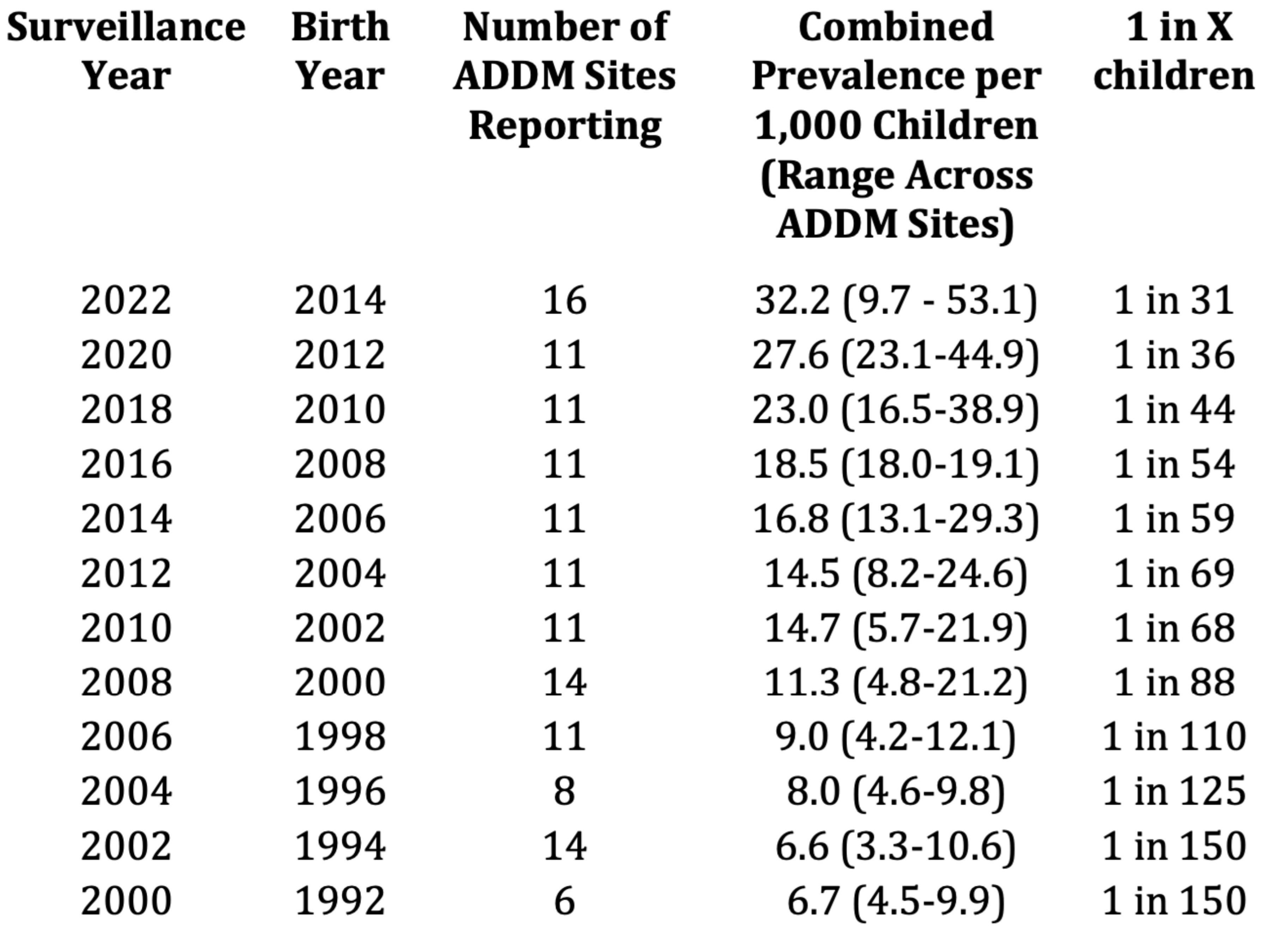

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

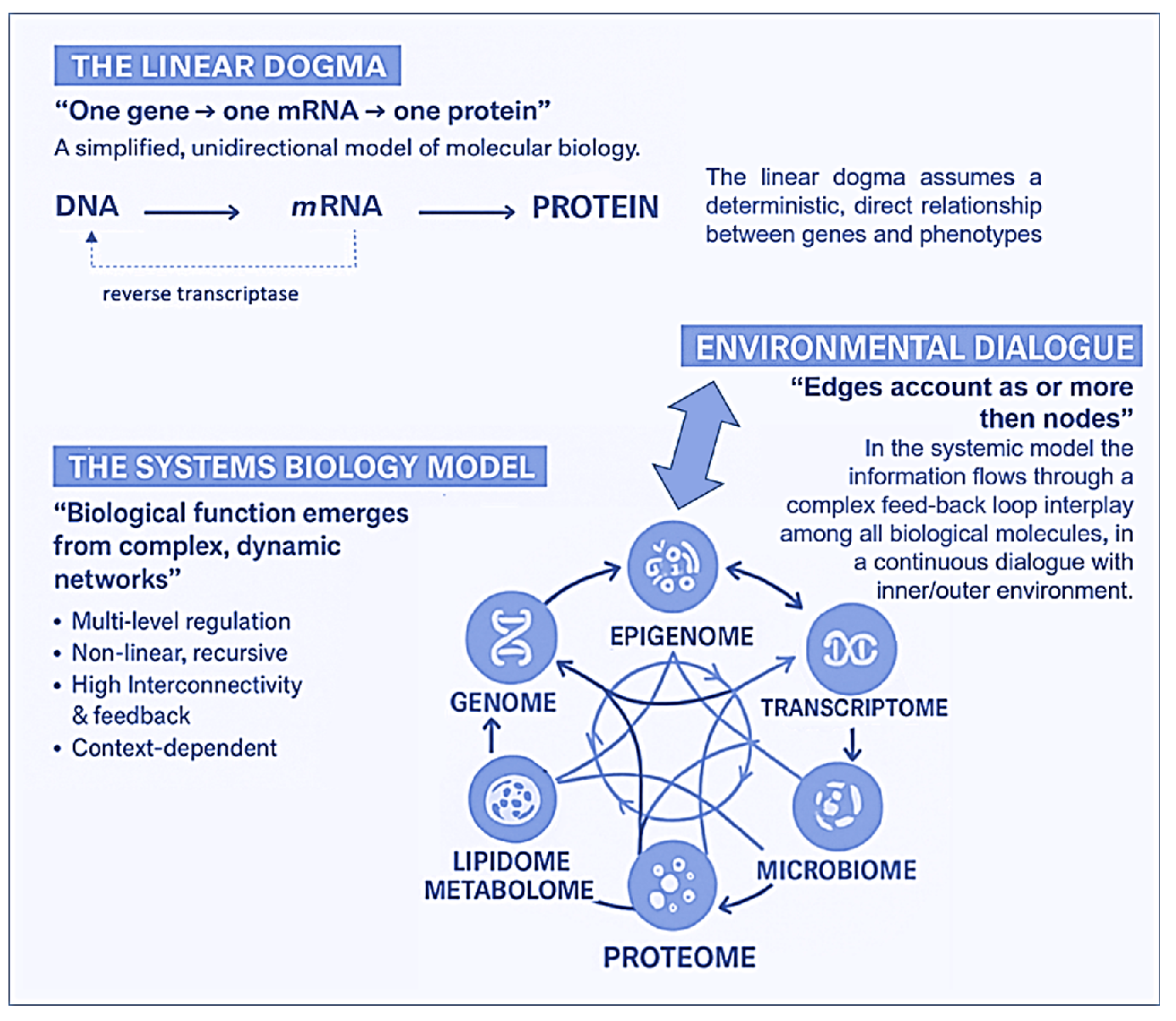

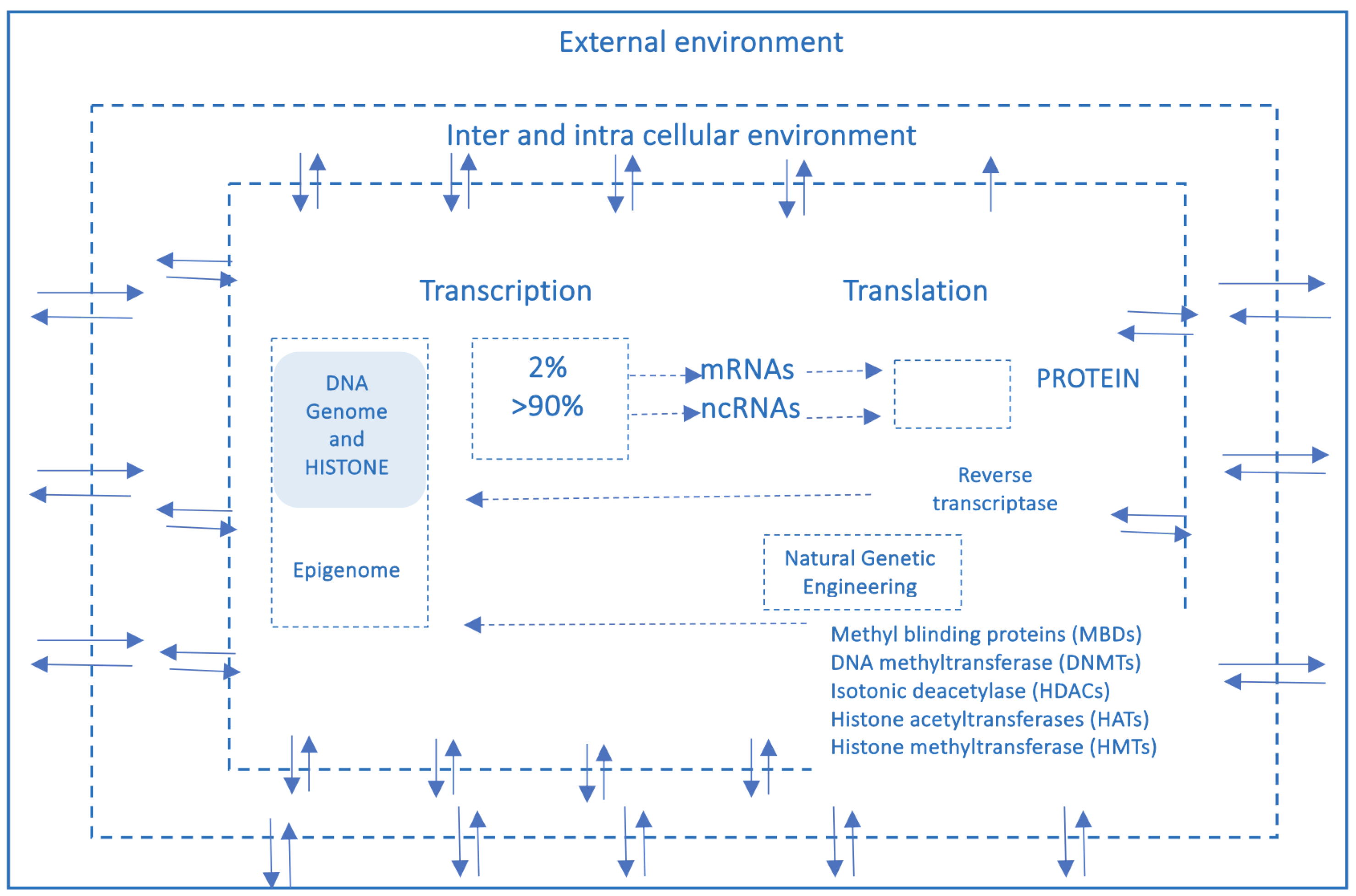

2. Towards A New Paradigm: From Linear Genetics to Systems Biology and Complex Genomics (Epigenetics, Metagenomics, Hologenomics)

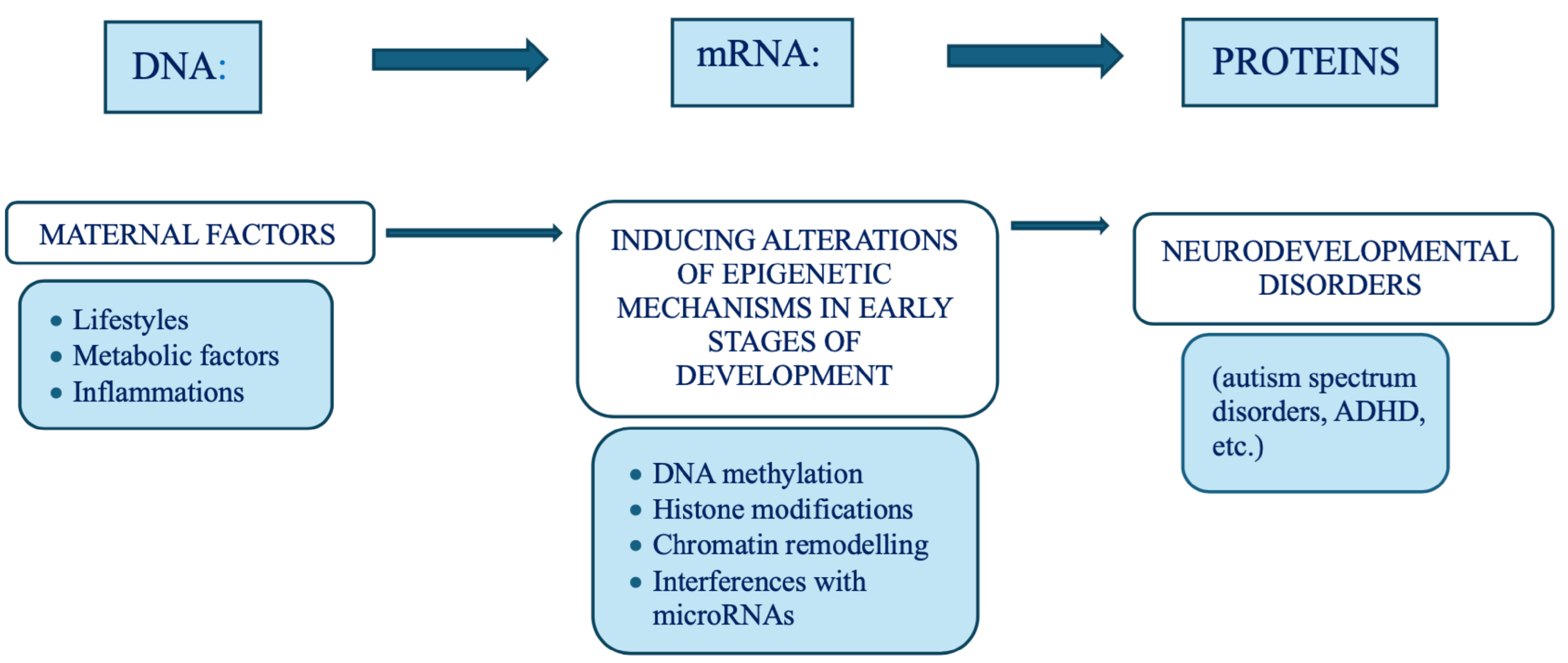

3. The Dynamic Interplay Between Nature and Nurture: An Epigenetic Shift

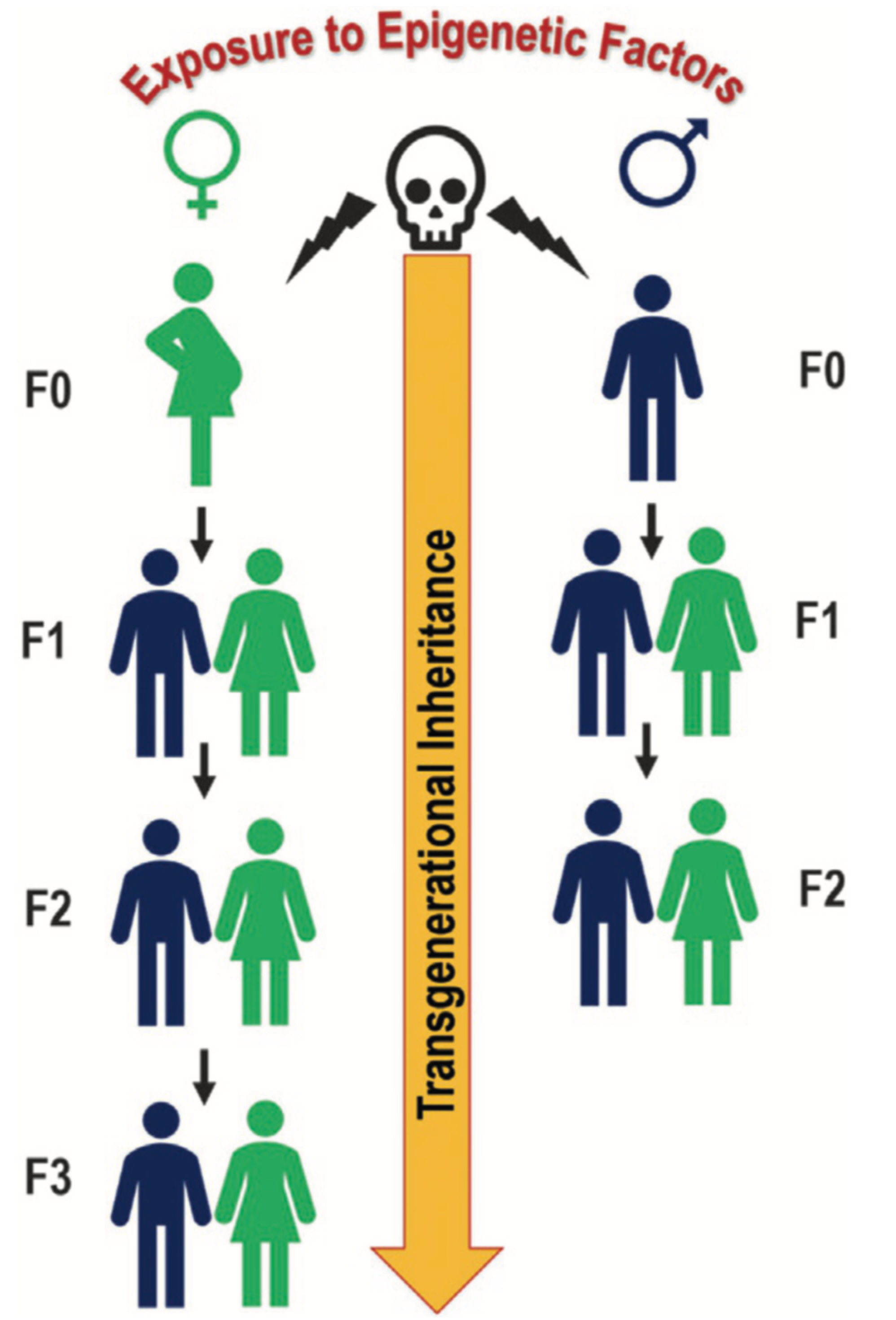

3.1. Epigenetic Intergenerational/Transgenerational Inheritance

3.2. An Historical/Epistemological Digression

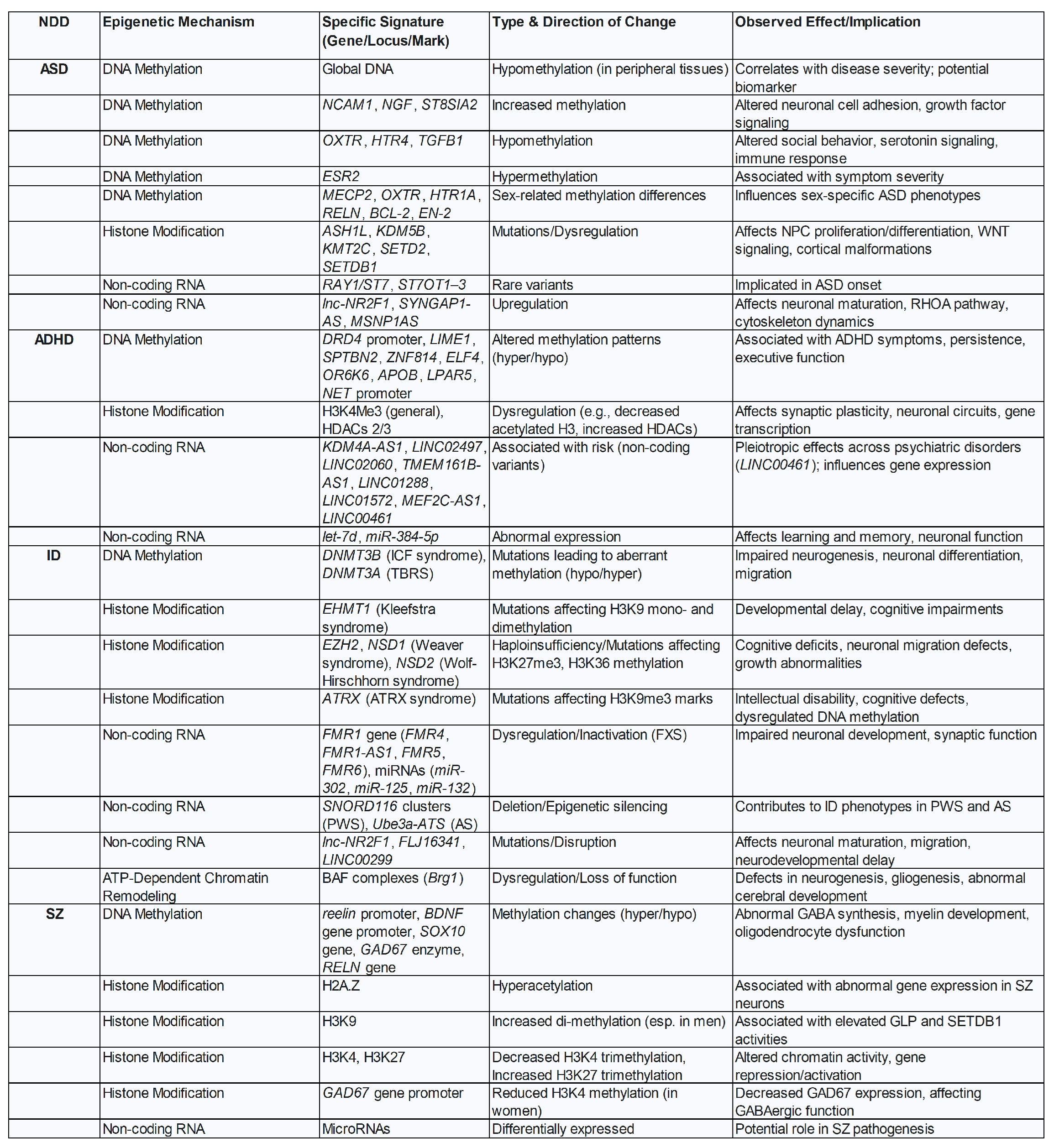

4. Epigenetics Signatures in The Spectrum of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

5. Epidemiological Data: Genuine Increase or Improved Diagnosis?

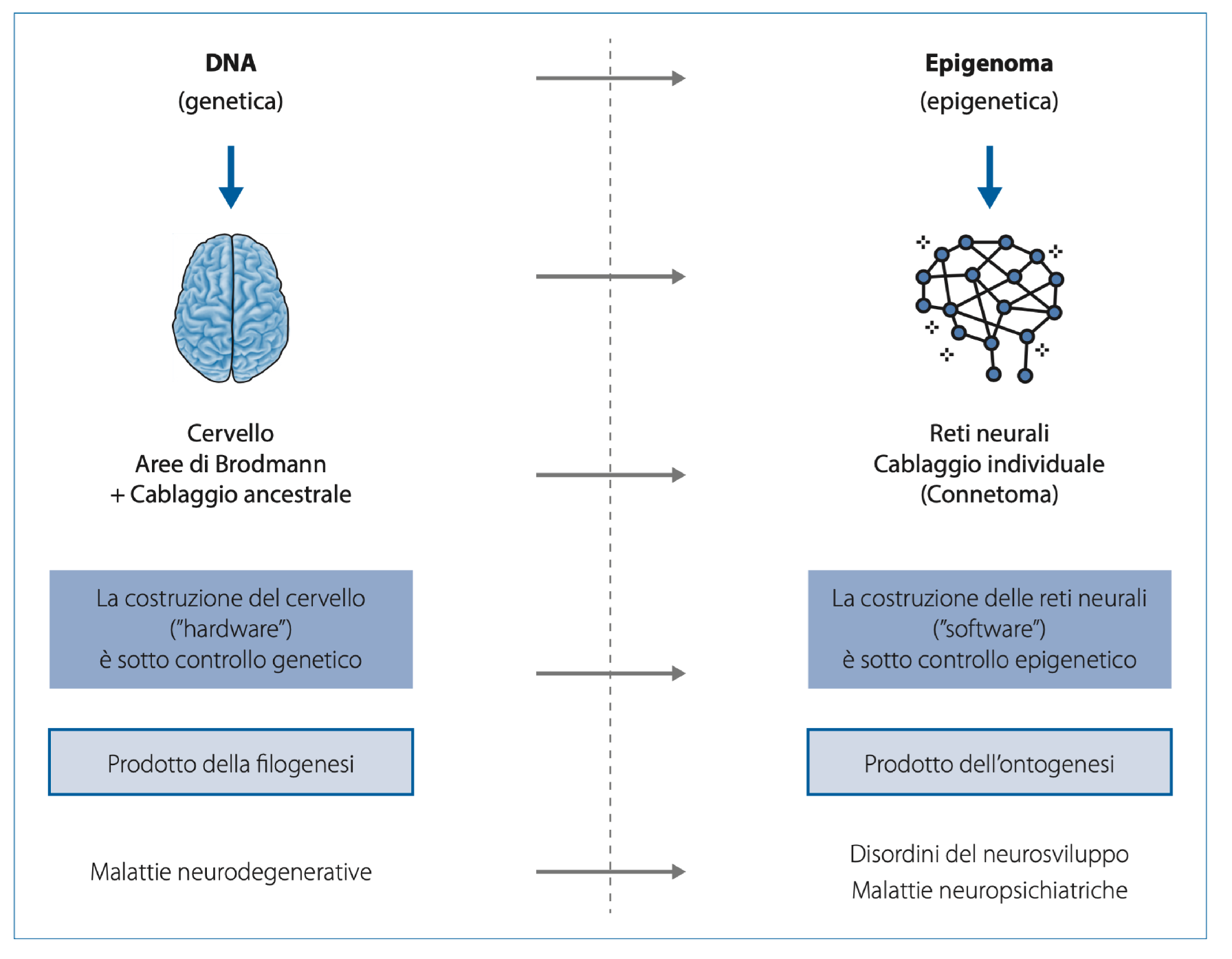

6. Phylogenesis and Ontogenesis: The Role of Genetics and Epigenetics

7. Risk Factors

7.1. Environmental Exposures and Epigenetic Neurotoxicology

8. Maternal Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Psycho-Neurotoxicity

9. Maternal Metabolic Disorders and Life Style

9.1. Maternal-Foetal Stress and Its Psycho-Neurotoxic Effects on the Foetus

10. Premature Births and Placental Inflammation: Psychoneurotoxic Effects on The Foetus

11. Parental Age and The Risk of Autism and Schizophrenia

12. The Adolescent Brain: A Critical Period of Development

13. Concluding Remarks: Epigenetics, The Bridge Between Genes and Environment, The Field of Human Responsibility

Acknowledgments

References

- J. Reichard and G. Zimmer-Bensch, The Epigenome in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Front. Neurosci. 15, 776809 (2021).

- P.M. Adamczyk, A. Shaw, I.M. Morella, L. More, Neurobiology, molecular pathways, and environmental influences in antisocial traits and personality disorders, Neuropharmacology 269, 110322 (2025).

- S. Lee, J.C. McAfee, J. Lee, A. Gomez, A.T. Ledford, D. Clarke, H. Min, M.B. Gerstein, A.P. Boyle, P.F. Sullivan, A.S. Beltran, H. Won, Massively parallel reporter assay investigates shared genetic variants of eight psychiatric disorders, Cell 188,1409 (2025).

- C. Xie, S. Xiang, C. Shen, X. Peng, J. Kang J, Y. Li, W. Cheng, S. He, M. Bobou, M.J. Broulidakis, B.M. van Noort, Z. Zhang, L. Robinson, N. Vaidya, J. Winterer, Y. Zhang, S. King, T. Banaschewski, G.J. Barker, A.L.W. Bokde, U. Bromberg, C. Büchel, H. Flor, A. Grigis, H. Garavan, P. Gowland, A. Heinz, B. Ittermann, H. Lemaître, J.L. Martinot, M.P. Martinot, F. Nees, D.P. Orfanos, T. Paus, L. Poustka, J.H. Fröhner, U. Schmidt, J. Sinclair, M.N. Smolka, A. Stringaris, H. Walter, R. Whelan, S. Desrivières, B.J. Sahakian, T.W. Robbins, G. Schumann, T. Jia, J. Feng, IMAGEN Consortium; STRATIFY/ESTRA Consortium; ZIB Consortium, A shared neural basis underlying psychiatric comorbidity, Nat Med. 29,1232 (2023). Erratum in: Nat Med. 29, 2375 (2023).

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Genomic Relationships, Novel Loci, and Pleiotropic Mechanisms across Eight Psychiatric Disorders, Cell 179, 1469 (2019).

- E.R. Bacon, R.D. Brinton, Epigenetics of the developing and aging brain: Mechanisms that regulate onset and outcomes of brain reorganization, Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 125, 503 (2021).

- B. Horsthemke, A critical view on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans, Nat Commun 9, 2973 (2018).

- D.S. Fernandez-Twinn, M. Constância, S.E. Ozanne, Intergenerational epigenetic inheritance in models of developmental programming of adult disease, Semin Cell Dev Biol. 43, 85 (2015).

- C. J. Mulligan, E. B. Quinn, D. Hamadmad, C. L. Dutton, L. Nevell, A. M. Binder, C. Panter-Brick, and R. Dajani, Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees, Scientific Reports 15, 5945 (2025).

- D.C. Dolinoy, J.R. Weidmana, R.L. Jirtle, Epigenetic gene regulation: linking early developmental environment to adult disease, Reprod. Toxicol. 23, 297 (2007).

- K. Hacker, The Burden of Chronic Disease, Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 8, 112 (2024). Erratum in: Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 9, 100588 (2024).

- G. Wang, S.O. Walker, X. Hong, T.R. Bartell, X. Wang, Epigenetics and Early Life Origins of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases, Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, S14-S21(2013).

- M.Kundakovic, F.A. Champagne, Early-life experience, epigenetics, and the developing brain, Neuropsychopharmacology 40,141 (2015).

- E. Kwon, Y.J. Kim, What is fetal programming?: a lifetime health is under the control of in utero health, Obstet. Gynecol. 60, 506 (2017).

- M. Subramanian, A. Wojtusciszyn, L. Favre, et al., Precision medicine in the era of artificial intelligence: implications in chronic disease management, J Transl Med 18, 472 (2020).

- Encode Project Consortium, An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome, Nature 489, 57 (2012).

- J.A. Shapiro, Revisiting the Central Dogma, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1178, 6 (2009).

- E. Balestrieri, C. Arpino, C. Matteucci, R. Sorrentino, F. Pica, et al., HERVs Expression in Autism Spectrum Disorders, PLoS ONE 7, e48831 (2012).

- G. Guffanti, S. Gaudi, J.H. Fallon, J. Sobell, S.G. Potkin, C. Pato, F. Macciardi, Transposable elements and psychiatric disorders, Am J Med Genet Part B 165B, 20 (2014).

- S. Dash, Y.A. Syed, and M.R. Khan, (2022) Understanding the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Brain Development and Its Association With Neurodevelopmental Psychiatric Disorders, Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 880544 (2022).

- C.L.Dutton, F.M. Maisha, E.B. Quinn, K.L. Morales, J.M. Moore, C.J. Mulligan, Maternal Psychosocial Stress Is Associated with Reduced Diversity in the Early Infant Gut Microbiome, Microorganisms 11, 975 (2023).

- L. Krubitzer, D.M. Kahn, Nature versus nurture revisited: an old idea with a new twist, Prog. Neurobiol. 70, 33 (2003).

- R. Perna, L. Harik, Nature (Genes), Nurture (Epigenetics), and Brain Development, J. Pediatr. Neonatal Care 6, 00238 (2017).

- S. Penner-Goeke, E.B. Binder, Linking environmental factors and gene regulation, Elife 13, e96710 (2024).

- D.C. Dolinoy, R. Das, J.R. Weidman, R.L. Jirtle, Metastable epialleles, imprinting, and the foetal origins of adult diseases, Pediatr. Res. 61, 30R (2007).

- T. Kubota, Epigenetic alterations induced by environmental stress associated with metabolic and neurodevelopmental disorders, Environ Epigenet. 2, 1 (2016).

- C.J. Mulligan, Systemic racism can get under our skin and into our genes, Am J Phys Anthropol. 2021 175, 399 (2021).

- R. Jaenisch, A. Bird, Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: How the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals, Nat. Genet. Suppl. 33, 245 (2003).

- C.J. Mulligan, Epigenetic age acceleration and psychosocial stressors in early childhood, Epigenomics Jul;17(10):701-710 (2025). [CrossRef]

- M. Subramanian, A. Wojtusciszyn, L. Favre, et al., Precision medicine in the era of artificial intelligence: implications in chronic disease management, J Transl Med 18, 472 (2020).

- M.F. Fraga, et al., Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins, PNAS 102, 10604 (2005).

- E. Hannon, et al., Characterizing genetic and environmental influences on variable DNA methylation using monozygotic and dizygotic twins, PLoS Genet 14(8): e1007544 (2018).

- F. Zenk, et al., Germ line-inherited H3K27me3 restricts enhancer function during maternal-to-zygotic transition, Science 357, 212 (2017).

- W. Reik, Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development, Nature 447, 425 (2007).

- A.J. Drake, B.R. Walker, The intergenerational effects of fetal programming: non-genomic mechanisms for the inheritance of low birth weight and cardiovascular risk, J. Endocrinol. 180, 1 (2004).

- B. Banushi, J. Collova, H. Milroy, Epigenetic Echoes: Bridging Nature, Nurture, and Healing Across Generations, Int J Mol Sci. 26, 3075 (2025).

- E. Burgio, P. Piscitelli, A. Colao, Environmental Carcinogenesis and Transgenerational Transmission of Carcinogenic Risk: From Genetics to Epigenetics, Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 15, 1791 (2018).

- T. Nomura, Transgenerational carcinogenesis: induction and transmission of genetic alterations and mechanisms of carcinogenesis, Mutat. Res. 544, 425 (2003).

- A.K. Webster, P.C. Phillips, Epigenetics and individuality: from concepts to causality across timescales, Nat Rev Genet 26, 406 (2025).

- R. Verdikt, A.A. Armstrong, P. Allard, Transgenerational inheritance and its modulation by environmental cues, Curr Top Dev Biol. 152, 31 (2023).

- T. Mørkve Knudsen, F.I. Rezwan, Y. Jiang, W. Karmaus, C. Svanes, J.W. Holloway, Transgenerational and intergenerational epigenetic inheritance in allergic diseases, J Allergy Clin Immunol. 142, 765 (2018).

- C. J. Mulligan, E. B. Quinn, D. Hamadmad, C. L. Dutton, L. Nevell, A. M. Binder, C. PanterBrick, and R. Dajani, Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees, Scientific Reports 15, 5945 (2025).

- G. Cavalli, E. Heard, Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease, Nature. 2019 571, 489 (2019).

- Y. Takahashi, M. Morales Valencia, Y. Yu, Y. Ouchi, K. Takahashi, M.N. Shokhirev, K. Lande, A.E. Williams, C. Fresia, M. Kurita, T. Hishida, K. Shojima, F. Hatanaka, E. Nuñez-Delicado, C.R. Esteban, J.C. Izpisua Belmonte, Transgenerational inheritance of acquired epigenetic signatures at CpG islands in mice, Cell. 186, 715 (2023).

- A.S. Kachhawaha, S. Mishra, A.K.Tiwari, Epigenetic control of heredity, Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 198, 25 (2023).

- R. Yehuda, S.M. Engel, S.R. Brand, J. Seckl, S.M. Marcus, G.S. Berkowitz, Transgenerational effects of posttraumatic stress disorder in babies of mothers exposed to the World Trade Center attacks during pregnancy, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 90, 4115 (2005).

- S.E. Cusick, M.K. Georgieff, The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the “First 1000 Days”, The Journal of Pediatrics, 175, 16 (2016).

- L. Katus, S. Lloyd-Fox, Broadening the lens: How 25 years of prospective longitudinal studies have reshaped infant neurodevelopment in the majority world, Infant Behav Dev. 81, 102128 (2025).

- E. Heard, and R.A. Martienssen, Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Myths and Mechanisms, Cell 157, 95 (2014).

- Aristotle, De Generatione et Corruptione, 336b.

- D.J. Barker, The origins of the developmental origins theory, Journal of Internal Medicine 261, 412 (2007).

- Aristotle, Parva Naturalia, 472a.

- L.H. Lumey, A.D. Stein, H.S. Kahn, K.M. van der Pal-de Bruin, G.J. Blauw, P.A. Zybert, and E.S. Susser, Cohort profile: The Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study, International Journal of Epidemiology 36, 1196 (2007).

- Aristotle, Parva Naturalia, 467a.

- D.J. Morris-Rosendahl, M.A. Crocq, Neurodevelopmental disorders-the history and future of a diagnostic concept, Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 22, 65 (2020).

- A.P. Mullin, A. Gokhale, A. Moreno-De-Luca, S. Sanyal, J.L. Waddington, V. Faundez, Neurodevelopmental disorders: mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes, Transl Psychiatry 3 e329 (2013).

- E. Bonti, I.K. Zerva, C. Koundourou, M. Sofologi, The High Rates of Comorbidity among Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Reconsidering the Clinical Utility of Distinct Diagnostic Categories, J Pers Med. 14, 300 (2024).

- A.G. Bertollo, C.F. Puntel, B.V. da Silva, M.l. Martins, M.D. Bagatini, Z.M. Ignácio, Neurobiological Relationships Between Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Mood Disorders, Brain Sci. 15, 307 (2025).

- MJ. Owen, MC O’Donovan, Schizophrenia and the neurodevelopmental continuum: evidence from genomics, World Psychiatry 16, 227 (2017).

- R. Lordan, C. Storni, C.A. De Benedictis, Autism Spectrum Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment, In: A.M. Grabrucker, editor, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications, Chapter 2 (2021).

- M.E. Márquez-Caraveo, R. Rodríguez-Valentín, V. Pérez-Barrón, R.A. Vázquez-Salas, J.C. Sánchez-Ferrer, F. De Castro, B. Allen-Leigh, E. Lazcano-Ponce, Children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders show cognitive heterogeneity and require a person-centered approach, Sci Rep. 11 18463 (2021).

- K.A. Aldinger, C.J. Lane, J. Veenstra-Van der Weele, P. Levitt, Patterns of Risk for Multiple Co-Occurring Medical Conditions Replicate Across Distinct Cohorts of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Autism Res. 8, 771 (2015).

- S. Patel S, V.X. Han, B.A. Keating, H. Nishida, S. Mohammad, H. Jones, R.C. Dale, NDD-ECHO: A standardised digital assessment tool to capture early life environmental and inflammatory factors for children with neurodevelopmental disorders, Brain Behav Immun Health. 46, 101011 (2025).

- A. Stoccoro, A.; E. Conti, E. Scaffei, S. Calderoni, F. Coppedè, L. Migliore, R. Battini, DNA Methylation Biomarkers for Young Children with Idiopathic Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9138 (2023).

- J. Reichard and G. Zimmer-Bensch, The Epigenome in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Front. Neurosci. 15, 776809 (2021).

- M. Hamza, S. Halayem, S. Bourgou, M. Daoud, F. Charfi, A. Belhadj, Epigenetics and ADHD: Toward an Integrative Approach of the Disorder Pathogenesis, Journal of Attention Disorders 23, 655 (2019).

- B. Mirkovic, A. Chagraoui, P. Gerardin, D. Cohen, Epigenetics and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: New Perspectives?, Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11, 579 (2020).

- G.H. Fu, W. Chen, H.M. Li, Y.F. Wang, L. Liu, Q.J. Qian, A potential association of RNF219-AS1 with ADHD: Evidence from categorical analysis of clinical phenotypes and from quantitative exploration of executive function and white matter microstructure endophenotypes, CNS Neurosci Ther. 27, 603 (2021).

- S.F. Zhang, J. Gao, C.M. Liu, The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Front Genet. 10, 1033 (2019).

- C. Liaci, L. Prandi, L. Pavinato, A. Brusco, M. Maldotti, I. Molineris, S. Oliviero, G.R.Merlo, The Emerging Roles of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Intellectual Disability and Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Int J Mol Sci. 2022 23, 6118 (2022).

- L. Smigielski, V. Jagannath, W. Rössler, S. Walitza, E. Grünblatt, Epigenetic mechanisms in SZ and other psychotic disorders: a systematic review of empirical human findings, Mol Psychiatry. 25, 1718 (2020).

- Ph. Grandjean, Ph. J. Landrigan, Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals, The Lancet 368, 2167 (2006) and Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity, The Lancet Neurology 13, 3 (2014).

- L. Francés , J. Quintero, A. Fernández, A. Ruiz, J. Caules, G. Fillon, A. Hervás, C.V. Soler, Current state of knowledge on the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood according to the DSM-5: a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA criteria, Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 16, 27 (2022).

- C. Bougeard, F. Picarel-Blanchot, R. Schmid, R. Campbell, J. Buitelaar, Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Co-Morbidities in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2, 212 (2024).

- J. Baio, et al., Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years, Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014, MMWR Surveill Summ. 67, 1 (2018).

- E. Fombonne, H. MacFarlane, A.C. Salem, Epidemiological surveys of ASD: advances and remaining challenges. J Autism Dev Disord. 51, 4271 (2021).

- R. Sacco, N. Camilleri, J. Eberhardt, K. Umla-Runge, D. Newbury-Birch, The Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Europe. In: Autism Spectrum Disorders – Recent Advances and New Perspectives. IntechOpen, (2023).

- A. Issac, K. Halemani, A. Shetty, L. Thimmappa, V. Vijay, K. Koni, P. Mishra, V. Kapoor, The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 16, 3 (2025).

- E. Bonti, I.K. Zerva, C. Koundourou, M. Sofologi. The High Rates of Comorbidity among Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Reconsidering the Clinical Utility of Distinct Diagnostic Categories, J Pers Med. 14, 300 (2024).

- Ph. Grandjean, Ph.J. Landrigan Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity, The Lancet Neurol. 13, 330 (2014).

- D.K. Lahiri, B. Maloney, B.M. Riyaz, Y.W. Ge, N.H. Zawia, How and when environmental agents and dietary factors affect the course of Alzheimer’s disease: the LEARn model (Latent Early Associated Regulation) may explain the triggering of AD, Curr Alzheimer Res. 4, 219 (2007).

- M. Subramanian, A. Wojtusciszyn, L. Favre, et al., Precision medicine in the era of artificial intelligence: implications in chronic disease management, J Transl Med. 18, 472 (2020).

- E. Burgio, Environment and Fetal Programming: the origins of some current ‘pandemics’, JPNIM. 4, e040237 (2015).

- S. Lacagnina, The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD), Am J Lifestyle Med. 14, 47 (2019).

- R.A. Raff, W. Arthur, S.B. Carroll, M.I. Coates, G. Wray, Chronicling the birth of a discipline, Evol.Dev. 1, 1 (1999).

- O. Miranda-Dominguez, E. Feczko, D.S. Grayson, H. Walum, J.T. Nigg, D.A. Fair, Heritability of the human connectome: a connectotyping study, Netw. Neurosci. 2, 175 (2018).

- P. Bailo, A. Piccinini, G. Barbara, P. Caruso, V. Bollati, S. Gaudi, Epigenetics of violence against women: a systematic review of the literature, Environ Epigenet. 10, dvae012 (2024).

- A. Carannante, M. Giustini, F. Rota, P. Bailo, A. Piccinini, G. Izzo, V. Bollati, S. Gaudi, Intimate partner violence and stress-related disorders: from epigenomics to resilience, Front Glob Womens Health. 6, 1536169 (2025).

- J.J. Tuulari, M. Bourgery, J. Iversen, et al, Exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with specific epigenetic patterns in sperm, Mol Psychiatry 30, 2635 (2025).

- L. Stenz, D.S. Schechter, S.R. Serpa, A. Paoloni-Giacobino, Intergenerational Transmission of DNA Methylation Signatures Associated with Early Life Stress, Curr Genomics 19, 665 (2018).

- C.J. Mulligan, Systemic racism can get under our skin and into our genes, Am J Phys Anthropol 175, 399 (2021).

- E. An, D.R. Delgadillo, J. Yang, et al, Stress-resilience impacts psychological wellbeing as evidenced by brain–gut microbiome interactions, Nat Mental Health 2, 935 (2024).

- T.L. Roth, J.D. Sweatt, Annual Research Review: Epigenetic mechanisms and environmental shaping of the brain during sensitive periods of development, J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52, 398 (2011).

- N.Q.V. Tran, K. Miyake, Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Environmental Toxicants: Epigenetics as an Underlying Mechanism, Int J Genomics 2017;2017:7526592, Epub 2017 May 8.

- S. Lacagnina, The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD), Am J Lifestyle Med 14, 47 (2019).

- R. Bose, S. Spulber, S. Ceccatelli, The threat posed by environmental contaminants on neurodevelopment: What can we learn from neural stem cells?, Int J Mol Sci 24, 4338 (2023).

- E.E. Antoniou, R. Otter, Phthalate exposure and neurotoxicity in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Environ Health Perspect 132, 027002 (2024).

- C. Sun, C. Huang, C.W. Yu, Environmental exposure and infants’ health, Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 91, 103741 (2023).

- F.Y. Ismail, A. Fatemi, M.V. Johnston, Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain, Eur J Paediatr Neurol 21, 23 (2017).

- B.P. Lanphear, et al, Erratum: Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis, Environ Health Perspect 127, 894 (2005).

- A. Kumar, A. Kumar, M.M.S. C.-P., A.K. Chaturvedi, A.A. Shabnam, G. Subrahmanyam, R. Mondal, D.K. Gupta, S.K. Malyan, S.S. Kumar, et al., Lead Toxicity: Health Hazards, Influence on Food Chain, and Sustainable Remediation Approaches, Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 2179 (2020).

- C. Johansson, A.F. Castoldi, N. Onishchenko, L. Manzo, M. Vahter, S. Ceccatelli, Neurobehavioural and molecular changes induced by methylmercury exposure during development, Neurotox Res 11, 241 (2007).

- P. Farías, D. Hernández-Bonilla, H. Moreno-Macías, S. Montes-López, L. Schnaas, J.L. Texcalac-Sangrador, C. Ríos, H. Riojas-Rodríguez, Prenatal Co-Exposure to Manganese, Mercury, and Lead, and Neurodevelopment in Children during the First Year of Life, Int J Environ Res Public Health 19, 13020 (2022).

- A.A. Appleton, B.P. Jackson, M. Karagas, C.J. Marsit, Prenatal exposure to neurotoxic metals is associated with increased placental glucocorticoid receptor DNA methylation, Epigenetics 12, 607 (2017).

- F. Perera, Y. Miao, Z. Ross, V. Rauh, A. Margolis, L. Hoepner, K.W. Riley, J. Herbstman, S. Wang, Prenatal exposure to air pollution during the early and middle stages of pregnancy is associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes at ages 1 to 3 years, Environ Health 23, 95 (2024).

- N. Grova, H. Schroeder, J.L. Olivier, J.D. Turner, Epigenetic and Neurological Impairments Associated with Early Life Exposure to Persistent Organic Pollutants, Int J Genomics 2019, 2085496 (2019.).

- A.A. Botnaru, A. Lupu, P.C. Morariu, A. Jităreanu, A.H. Nedelcu, B.A. Morariu, E. Anton, M.L. Di Gioia, V.V. Lupu, O.M. Dragostin, M. Vieriu, I.D. Morariu, Neurotoxic Effects of Pesticides: Implications for Neurodegenerative and Neurobehavioral Disorders, J Xenobiot 15, 83 (2025).

- K.C. Brannen, L.L.B. Devaud, J.C. Liu, J.M. Lauder, Prenatal exposure to neurotoxicants dieldrin or lindane alters tert-Butylbicyclophosphorothionate binding to GABA(A) receptors in fetal rat brainstem, Dev Neurosci 20, 34 (1998).

- L.V.J. Van Melis, T. Bak, A.M. Peerdeman, R.G.D.M. van Kleef, J.P. Wopken, R.H.S. Westerink, Acute, prolonged, and chronic exposure to organochlorine insecticides evoke differential effects on in vitro neuronal activity and network development, Neurotoxicology 111, 103308 (2025).

- V.A. Rauh, R. Garfinkel, F.P. Perera, H.F. Andrews, L. Hoepner, D.B. Barr, R. Whitehead, D. Tang, R.W. Whyatt, Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children, Pediatrics 118, 1845 (2006).

- J.R. Roberts, E.H. Dawley, J.R. Reigart, Children’s low-level pesticide exposure and associations with autism and ADHD: a review, Pediatr Res 85, 234 (2019).

- A.C.C. Bertoletti, K.K. Peres, L.S. Faccioli, M.C. Vacci, I.R.D. Mata, C.J. Kuyven, S.M.D. Bosco, Early exposure to agricultural pesticides and the occurrence of autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review, Rev Paul Pediatr 41, e2021360 (2022).

- H.O. Atladottir, P. Thorsen, L. Ostergaard, D.E. Schendel, S. Lemcke, M. Abdallah, E.T. Parner, Maternal infection requiring hospitalization during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders, J Autism Dev Disord 40, 1423 (2010).

- O. Zerbo, A.-M. Iosif, C. Walker, S. Ozonoff, R.L. Hansen, I. Hertz-Picciotto, Is maternal influenza or fever during pregnancy associated with autism or developmental delays? Results from the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) study, J Autism Dev Disord 43, 25 (2013).

- H.K. Kwon, G.B. Choi, J.R. Huh, Maternal inflammation and its ramifications on fetal neurodevelopment, Trends Immunol 43, 230 (2022).

- G. Ayoub, Neurodevelopmental impact of maternal immune activation and autoimmune disorders, environmental toxicants and folate metabolism on autism spectrum disorder, Curr Issues Mol Biol 47, 721 (2025).

- A. Keil, J.L. Daniels, U. Forssen, C. Hultman, S. Cnattingius, K.C. Soderberg, M. Feychting, P. Sparen, Parental autoimmune diseases associated with autism spectrum disorders in offspring, Epidemiology 21, 805 (2010).

- H.O. Atladottir, M.G. Pedersen, P. Thorsen, P.B. Mortensen, B. Deleuran, W.W. Eaton, E.T. Parner, Association of family history of autoimmune diseases and autism spectrum disorders, Pediatrics 124, 687 (2009).

- M.N. Spann, L. Timonen-Soivio, A. Suominen, K. Cheslack-Postava, I.W. McKeague, A. Sourander, A.S. Brown, Proband and familial autoimmune diseases are associated with proband diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 58, 496 (2019).

- M.A. Labouesse, E. Dong, D.R. Grayson, A. Guidotti, U. Meyer, Maternal immune activation induces gad1 and gad2 promoter remodeling in the offspring prefrontal cortex, Epigenetics 10, 1143 (2015).

- I. Dudova, K. Horackova, M. Hrdlicka, M. Balastik, Can maternal autoantibodies play an etiological role in ASD development?, Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 16, 1391 (2020).

- D. Braunschweig, P. Krakowiak, P. Duncanson, R. Boyce, R.L. Hansen, P. Ashwood, I. Hertz-Picciotto, I.N. Pessah, J. Van de Water, Autism-specific maternal autoantibodies recognize critical proteins in developing brain, Transl Psychiatry 3, e277 (2013).

- K.L. Jones, J. Van de Water, Maternal autoantibody related autism: mechanisms and pathways, Mol Psychiatry 24, 252 (2019).

- A. Ramirez-Celis, L.A. Croen, C.K. Yoshida, S.E. Alexeeff, J. Schauer, R.H. Yolken, P. Ashwood, J. Van de Water, Maternal autoantibody profiles as biomarkers for ASD and ASD with co-occurring intellectual disability, Mol Psychiatry 27, 3760 (2022).

- M.R. Bruce, A.C.M. Couch, S. Grant, J. McLellan, K. Ku, C. Chang, A. Bachman, M. Matson, R.F. Berman, R.J. Maddock, D. Rowland, E. Kim, M.D. Ponzini, D. Harvey, S.L. Taylor, A.C. Vernon, M.D. Bauman, J. Van de Water, Altered behavior, brain structure, and neurometabolites in a rat model of autism-specific maternal autoantibody exposure, Mol Psychiatry 28, 2136 (2023).

- A. Banik, D. Kandilya, S. Ramya, W. Stünkel, Y.S. Chong, S.T. Dheen, Maternal factors that induce epigenetic changes contribute to neurological disorders in offspring, Genes (Basel) 8, 150 (2017).

- A.A. Lussier, T.S. Bodnar, J. Weinberg, Intersection of epigenetic and immune alterations: implications for foetal alcohol spectrum disorder and mental health, Front Neurosci 15, 788630 (2021).

- A. Smith, F. Kaufman, M.S. Sandy, A. Cardenas, Cannabis exposure during critical windows of development: epigenetic and molecular pathways implicated in neuropsychiatric disease, Curr Environ Health Rep 7, 325 (2020).

- D. Álvarez-Mejía, J.A. Rodas, J.E. Leon-Rojas, From womb to mind: prenatal epigenetic influences on mental health disorders, Int J Mol Sci 26, 6096 (2025).

- D. Baroutis, I.M. Sotiropoulou, R. Mantzioros, M. Theodora, G. Daskalakis, P. Antsaklis, Prenatal maternal stress and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes: a narrative review, J Perinat Med (2025) Sep 17. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2025-0297.

- B. Yao, Y. Cheng, Z. Wang, Y. Li, L. Chen, L. Huang, W. Zhang, D. Chen, H. Wu, B. Tang, P. Jin, DNA N6-methyladenine is dynamically regulated in the mouse brain following environmental stress, Nat Commun 8, 1122 (2017).

- E. Ohuma, A.-B. Moller, E. Bradley, et al, National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: a systematic analysis, Lancet 402, 1261 (2023).

- E.M. Cervantes, S. Girard, Placental inflammation in preterm premature rupture of membranes and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders, Cells 14, 965 (2025).

- K. Lyall, L. Song, K. Botteron, L.A. Croen, S.R. Dager, M.D. Fallin, H.C. Hazlett, E. Kauffman, R. Landa, R. Ladd-Acosta, D.S. Messinger, S. Ozonoff, J. Pandey, J. Piven, R.J. Schmidt, R.T. Schultz, W.L. Stone, C.J. Newschaffer, H.E. Volk, The association between parental age and autism-related outcomes in children at high familial risk for autism, Autism Res 13, 998 (2020).

- A. Krug, M. Wöhr, D. Seffer, H. Rippberger, A.Ö. Sungur, B. Dietsche, F. Stein, S. Sivalingam, A.J. Forstner, S.H. Witt, H. Dukal, F. Streit, A. Maaser, S. Heilmann-Heimbach, T.F.M. Andlauer, S. Herms, P. Hoffmann, M. Rietschel, M.M. Nöthen, M. Lackinger, G. Schratt, M. Koch, R.K.W. Schwarting, T. Kircher, Advanced paternal age as a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders: a translational study, Mol Autism 11, 54 (2020).

- B. Yao, Y. Cheng, Z. Wang, Y. Li, L. Chen, L. Huang, W. Zhang, D. Chen, H. Wu, B. Tang, P. Jin, DNA N6-methyladenine is dynamically regulated in the mouse brain following environmental stress, Nat Commun 8, 1122 (2017).

- E. Ohuma, A.-B. Moller, E. Bradley, et al, National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: a systematic analysis, Lancet 402, 1261 (2023).

- E.M. Cervantes, S. Girard, Placental inflammation in preterm premature rupture of membranes and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders, Cells 14, 965 (2025).

- K. Lyall, L. Song, K. Botteron, L.A. Croen, S.R. Dager, M.D. Fallin, H.C. Hazlett, E. Kauffman, R. Landa, R. Ladd-Acosta, D.S. Messinger, S. Ozonoff, J. Pandey, J. Piven, R.J. Schmidt, R.T. Schultz, W.L. Stone, C.J. Newschaffer, H.E. Volk, The association between parental age and autism-related outcomes in children at high familial risk for autism, Autism Res 13, 998 (2020).

- A. Krug, M. Wöhr, D. Seffer, H. Rippberger, A.Ö. Sungur, B. Dietsche, F. Stein, S. Sivalingam, A.J. Forstner, S.H. Witt, H. Dukal, F. Streit, A. Maaser, S. Heilmann-Heimbach, T.F.M. Andlauer, S. Herms, P. Hoffmann, M. Rietschel, M.M. Nöthen, M. Lackinger, G. Schratt, M. Koch, R.K.W. Schwarting, T. Kircher, Advanced paternal age as a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders: a translational study, Mol Autism 11, 54 (2020).

- I. Weaver, N. Cervoni, F. Champagne, et al, Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior, Nat Neurosci 7, 847 (2004).

- J.J. Wood, A. Drahota, K. Sze, K. Har, A. Chiu, D.A. Langer, Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial, J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50, 224 (2009).

- N.J. Ball, E. Mercado III, I. Orduña, Enriched environments as a potential treatment for developmental disorders: a critical assessment, Front Psychol 10, 466 (2019).

- S. Gaudi, G. Guffanti, J. Fallon, F. Macciardi, Epigenetic mechanisms and associated brain circuits in the regulation of positive emotions: a role for transposable elements, J Comp Neurol 524(15):2944–2954 (2016).

- P. Kaliman, Epigenetics and meditation, Curr Opin Psychol 28, 76 (2019).

- T. Kubota, Biological understanding of neurodevelopmental disorders based on epigenetics, a new genetic concept in education, In Learning Disabilities—Neurobiology, Assessment, Clinical Features and Treatments, Misciagna S., Ed., IntechOpen, London, UK (2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).