1. Introduction

Cybersecurity research is essential as modern organizations depend on connected systems for daily operations and national infrastructure protection. Spotting hostile activity in time is a persistent challenge for both business and government contexts [5,6]. Security teams collect vast streams of enterprise logs (logon, email, HTTP, device, file) through Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) platforms to reconstruct events and detect abuse, but static rules and signature filters struggle with evolving behaviours and produce high alert volumes [5,10]. Insider threats are especially problematic because trusted users can misuse legitimate access across many channels, blending abnormal actions with routine work and evading rule-based controls [8,10].

Anomalies are data points or sequences that do not fit the usual pattern of the whole dataset. In security logs, anomalies can appear as: (i) point anomalies (a single unusual event), (ii) contextual anomalies (an event that is only unusual in a specific context, such as time of day or host), and (iii) collective anomalies (a sequence that is normal per event but abnormal as a group). Choosing a detector depends on data type, latency needs, and label availability; deep learning is often used because it can learn useful features directly from data and support real-time scoring.

Anomaly detection on enterprise logs seeks to learn what is “normal” for users and assets, then flag departures. Classical supervised machine-learning approaches (SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost) have been applied to the CMU-CERT Insider Threat Test Dataset (CERT), log data with engineered features, and show promise, yet they can be sensitive to class imbalance, feature leakage, and non-stationary behaviour in production [10]. Unsupervised and one-class methods (OC-SVM, Isolation Forest) avoid the need for labelled attacks and are attractive under rare-event conditions, but often rely on hand-crafted summaries and global thresholds that do not adapt well to user-specific drift [12,13].

Between fully supervised and unsupervised lie self-/semi-supervised approaches: sequence models trained with proxy tasks (e.g., masked event prediction) learn bidirectional context without labelled anomalies and reduce dependence on manual features [23]. Regardless of method, evaluation matters: user- and time-disjoint splits, and reporting precision–recall under a fixed alert budget, avoid optimistic results from random mixes, and better reflect Security Operations Centre (SOC) reality [11,23].

Deep learning has been adopted to capture temporal context and complex patterns in logs. CNN/RNN hybrids and attention mechanisms have improved over traditional pipelines by learning features directly from sequences of activities, and recent self-supervised Transformers (BERT for logs) model bidirectional context without labelled anomalies [4]. These advances are complemented by behavioural biometrics-keystroke dynamics and mouse usage-which add a human-pattern signal for continuous authentication and impersonation resistance in enterprise settings [18,21]. Public datasets and benchmarks make this tractable: the CMU keystroke corpus and related studies for typing rhythms, the Balabit and Bogazici mouse-dynamics sets for cursor behaviour, and the CERT insider-threat test datasets for multi-source enterprise activity.

Despite progress, three practical gaps remain for operations. First, many evaluations emphasize accuracy/ROC on random splits rather than user/time-disjoint protocols and precision–recall trade-offs at analyst-friendly alert rates, which is what matters in a SOC workflow [10]. Second, deployment inside SIEM requires calibrated scores, adaptive thresholds, and real-time scoring paths so analysts can act on ranked anomalies rather than raw detector outputs [5,7,32]. Third, cross-modal fusion is underexplored: combining enterprise system logs with keystroke and mouse dynamics under a unified feature schema and evaluating end-to-end in a SIEM; most prior work treats CERT logs, CMU keystrokes, and Balabit/Bogazici mouse dynamics in isolation [29,32,15,21].

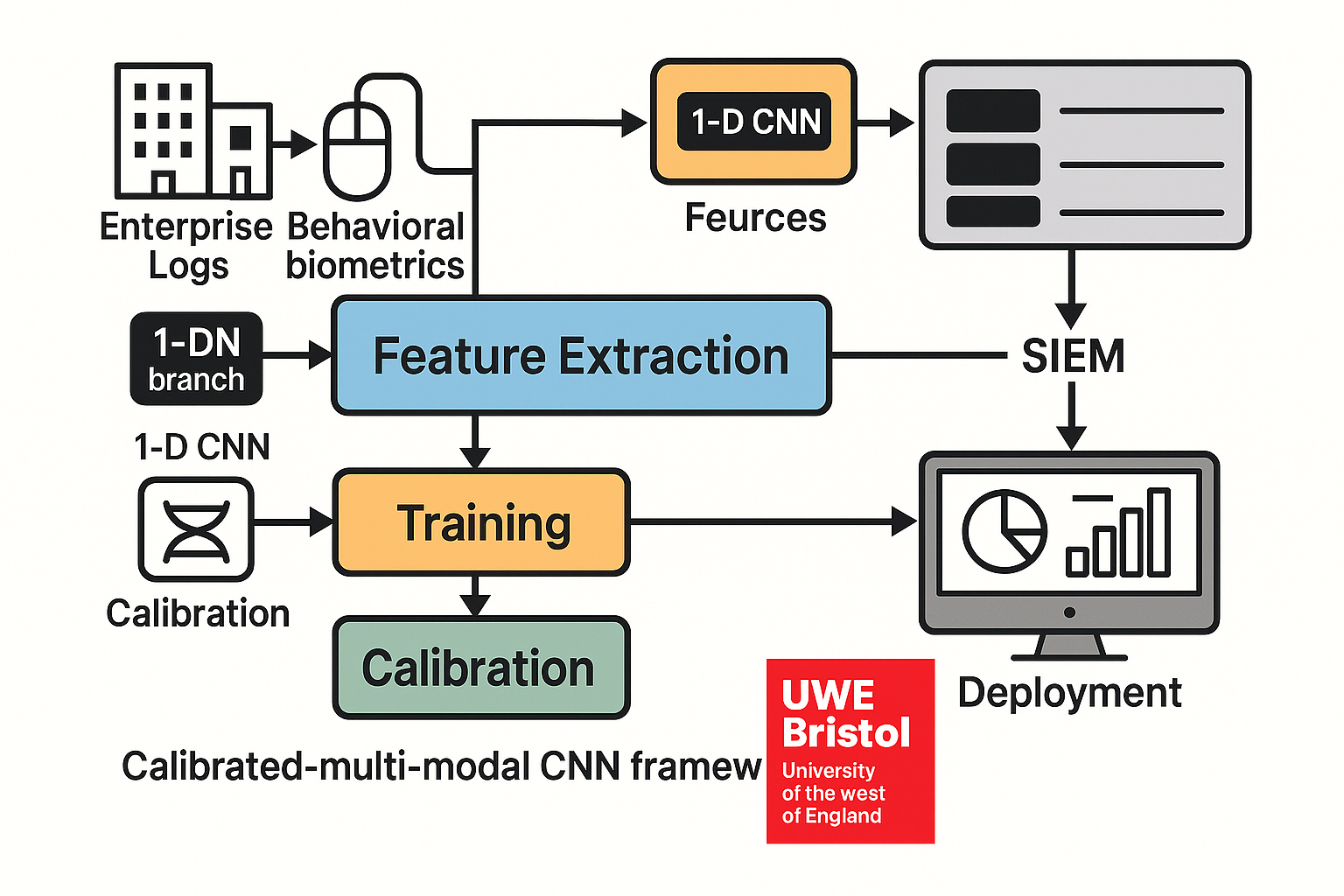

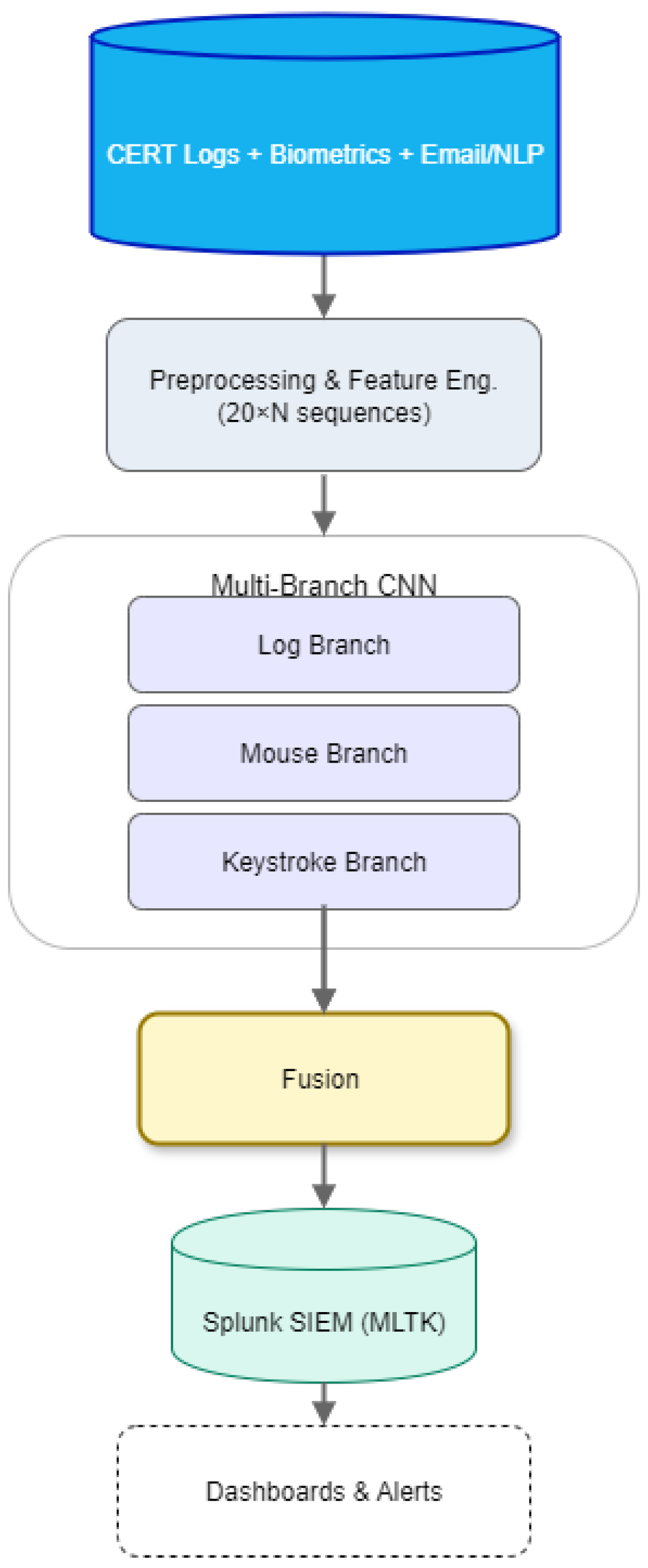

Motivated by these needs, a SIEM-integrated prototype is developed for insider-focused anomaly detection that fuses enterprise logs with behavioural biometrics. The system operates on CMU-CERT multi-source logs implemented end-to-end for logon/device and is extensible to file/HTTP/email and keystroke signals; this study integrates Balabit mouse dynamics. Log events are mapped to a unified feature window and passed through per-modality 1D-CNN branches (kernels 2–5, max/global-max pooling, dropout). No model-level fusion is applied in this study; each modality produces scores independently, and correlation occurs at the dashboard. To handle class imbalance, downsampling, class weights, and focal loss are used; scores are calibrated (e.g., Platt or isotonic) so analysts can set an alert budget via threshold tuning. The trained logon and device models are exported to the Splunk Machine Learning Toolkit (MLTK) for real-time scoring, with dashboards for anomaly timelines, risky users/hosts, and triage controls [32]. Evaluation uses user-/time-disjoint splits and reports precision and recall under fixed alert rates, plus latency and throughput for streaming inference, aligning results with SOC needs.

This work pursues five objectives: (i) learn short-sequence behaviour patterns from enterprise logs using compact 1D-CNNs and from behavioural biometrics using a lightweight ResConv+BiLSTM; (ii) assess cross-modality complementarity via per-modality detectors and outline a fusion design for future evaluation; (iii) deploy the model inside Splunk MLTK and measure operational metrics (real-time latency, throughput, stability); (iv) calibrate scores and expose an analyst-unable threshold to manage precision–recall as behaviour drifts; and (v) provide a reproducible blueprint ( feature schema, windowing, training settings, dashboards) suitable for SOC adoption.

This paper makes the following contributions: (i) per-modality detectors-compact 1D-CNNs for logon/device with a unified

log feature schema, and a ResConv+BiLSTM for Balabit mouse (offline); (ii) a practical roadmap to complete email/HTTP integration and to add keystroke + mouse for decision-level fusion in future work, maintaining SIEM parity and calibration; (iii) an imbalance-aware training and calibration recipe (downsampling, class weights, focal loss, and Platt/Isotonic calibration) tailored to SOC workflows; (iv) an operational evaluation protocol using user-/time-disjoint splits, precision–recall at fixed alert budgets, and end-to-end latency/throughput; and (v) a practical figure and dashboard set demonstrating the path from offline research to SOC-ready deployment. As an overview, the system prototype is shown in

Figure 1, which illustrates the multi-branch CNN, the unified

schema, and the Splunk MLTK deployment path.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on anomaly detection in enterprise logs, behavioural biometrics (keystroke/mouse), and SIEM-integrated models, identifying gaps this study addresses.

Section 3 details the methodology-datasets (CMU-CERT, CMU keystroke, Balabit), the unified

feature schema, windowing, multi-branch 1D-CNN architecture, imbalance handling, score calibration, and Splunk MLTK deployment.

Section 4 presents the experimental setup and results, including user/time-disjoint splits and baseline comparisons.

Section 5 offers evaluation and discussion, covering precision recall under fixed alert budgets, latency/throughput for streaming inference, error analysis, and operational considerations.

Section 6 concludes with key findings, limitations, and directions for future work.

2. Related Work

Early deep learning research on enterprise security shifted from static rule correlation toward adaptive models that learn patterns directly from event sequences. Lee et al. demonstrated one of the first ANN-based alert triage systems that learned weighted event profiles to prioritize alarms, substantially reducing false positives compared with rule-driven SIEM correlation [5]. Around the same period, several reviews advocated convolutional neural networks for cybersecurity applications because CNNs efficiently capture local temporal and spatial dependencies in multidimensional inputs without extensive feature engineering [4]. These early studies marked a transition from static signatures to pattern-learning models suitable for operational environments. This section reviews prior studies on log-based insider detection, behavioural biometrics, and operational integration, highlighting the experimental limitations that motivated this work.

On insider-threat detection, classical supervised machine-learning methods on CERT datasets (r4.2 and r6.2) including Random Forest, SVM, and Gradient Boosting provided strong baselines but consistently suffered from class imbalance and data leakage when random splits mixed users or time periods [10]. These approaches typically achieved overall accuracy above 0.90 but failed to maintain precision when evaluated under realistic, user-disjoint settings. Follow-up work introduced sequential modelling using BiLSTM and embedding-based variants, reporting improved F1-scores ( 0.90) and more stable predictions when temporal context was included [11]. However, most of these evaluations relied on ROC-AUC or accuracy rather than precision-recall metrics, which limits their operational relevance in imbalanced insider datasets.

Unsupervised anomaly-detection methods remained attractive due to limited labelled insider data. Isolation Forest and one-class SVM approaches showed promising results (Acc 0.98, F1 0.99) under random or balanced splits but degraded sharply under time-disjoint evaluation [13]. Their reliance on global thresholds and the absence of user-specific adaptation restricted practical precision in live SOC settings. More advanced autoencoder-based and hybrid AE-LSTM models attempted to address imbalance by combining reconstruction and temporal losses. Narmadha et al. reported PR-AUC around 0.45 on skewed subsets, improving sensitivity to rare events but at the cost of increased inference latency and limited interpretability [3]. Overall, these early experiments established the importance of sequential context but remained constrained to offline, uncalibrated evaluation protocols.

Recent work introduced deeper architectures and improved optimization schemes. The M-EOS stacked CNN combined convolutional filters with an attentional BiGRU and applied modified equilibrium optimization for hyperparameter tuning, achieving Acc = 92.5%, Prec = 98%, and AUC 0.95 on CERT insider data [1]. Although performance was strong, evaluation relied on mixed user data without explicit time-disjoint validation. Similarly, dual-stage frameworks such as those proposed in [8] separated coarse anomaly filtering from fine-grained sequence classification, improving recall by 4-6% over single-stage models. Autoencoder-LSTM hybrids [3] and attention-driven CNNs extended this trend, emphasizing multi-level temporal representation but remaining untested under strict imbalance or streaming conditions. A structured comparison of representative models, datasets, and reported metrics is summarized in (

Table 1).

Transformer-based log analysis advanced further with LogBERT [23], which applied masked event prediction to learn bidirectional context without manual features. LogBERT achieved ROC-AUC > 0.90 on large-scale log corpora (HDFS, BGL) and proved effective for unseen attack types. However, the study reported ROC metrics only, omitting PR-AUC, calibration, and latency evaluation. Other BERT style or hybrid CNN-Transformer models have shown similar promise but remain limited to static, offline datasets and have yet to demonstrate end-to-end SIEM integration.

Behavioural biometrics form a complementary human-centric layer for anomaly detection. The keystroke dynamics benchmark introduced by CMU [24] established a standard evaluation protocol based on hold time and inter-key latency features, showing that temporal statistics can uniquely identify users and detect impostors. Later deep temporal CNNs [16] achieved EER between 3%-5%, outperforming handcrafted statistical baselines by learning rhythmic micro patterns in typing cadence. Mouse dynamics studies on the Bogazici and Balabit datasets [15,31] explored pointer trajectories, speed, and curvature as behavioural signals. Deep residual CNNs and CNN-BiLSTM hybrids achieved F1 0.90-0.95 on impostor detection, though cross-device generalization remained limited. Subsequent fusion-based research combined keystroke and mouse modalities, demonstrating improved robustness against spoofing and coercion [17]. These experiments confirmed that fusing multiple behavioural channels strengthens identity assurance, yet integration with enterprise log analytics remains largely unexplored.

A consistent gap across these studies lies in experimental design and operationalization. Most research reports only ROC-AUC or accuracy using random splits, which exaggerates performance and hides class imbalance effects [1,10,11,23]. User- and time-disjoint protocols, which better simulate real SOC deployments, are rarely applied. Precision-recall curves and alert budget analyses crucial for assessing analyst workload are rarely reported. Likewise, calibrated scoring and threshold control are often omitted, even though analysts require stable, interpretable alert probabilities to manage false positives. Reinforcement learning approaches to dynamic thresholding [22] and adaptive cost policies have been proposed conceptually but lack empirical validation inside live systems.

From a tooling perspective, Splunk’s Machine Learning Toolkit (MLTK) provides mechanisms for importing trained models, executing real-time scoring, and visualizing dashboards [32]. Despite this, nearly all prior CNN-based insider detectors stop at offline evaluation. Earlier ANN-based alert triage experiments hinted at SIEM alignment [5], yet no study has documented a calibrated CNN-based insider detector operating live within the SIEM loop.

In summary, (i) classical ML baselines on CERT remain sensitive to imbalance and prone to leakage [10]; (ii) deep CNN, LSTM, and Transformer models improve temporal representation but are largely uncalibrated and offline [1,3,8,23]; (iii) behavioural biometrics such as keystroke and mouse dynamics provide additional context for user behaviour but are seldom fused with enterprise logs [15],[18,21,24]; and (iv) SIEM-integrated, calibrated evaluation remains rare [5,22,32]. These limitations motivate the present study’s focus on realistic disjoint splits, calibration, and operational integration of multimodal CNN detectors within Splunk MLTK.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Ground Truth

The evaluation uses the CMU–CERT Insider Threat Test releases r1–r6.2, comprising multi-source activity logs (logon/logoff, device/USB, HTTP, email, file), supplemented by organizational metadata (LDAP and psychometrics) [

29,

30]. Releases r1–r6.2 were processed by a single pipeline and schema-harmonized to a consistent field set per modality; evaluation uses the subsets corresponding to the modalities reported in (Results).

The Balabit Mouse Dynamics Challenge provides continuous behavioural biometrics: ten enrolled users performing real administrative tasks over remote desktop in multi-hour sessions (≈40 min to ≈7 h), yielding pointer trajectories and timestamps. The distribution includes a held-out split with “legal/illegal” labels suitable for impostor detection and continuous-authentication studies [

15].

Real-time evaluation covers Logon and Device; HTTP/Email are partially prepared offline; Balabit mouse dynamics is evaluated offline. No model-level fusion is used in this paper; modalities are scored independently and correlated at the dashboard (overlapping users/hosts, aligned anomaly timelines).

Ground Truth and Window Targets (Supervised). CERT insider datasets provide user identities and labelled time intervals associated with malicious activity [29,30]. Following prior CERT-style formulations [11,23], the ground-truth target is defined at the window level rather than per event, reflecting how Security Operations Centres (SOCs) assess temporal segments of user behaviour instead of single log entries. Let

denote the set of insider-labelled days for user

u. For a per-user window

, the label

is defined as:

This labelling rule follows the same logic as Manoharan et al. [11] and LogBERT [23], where an entire behavioural window is considered anomalous if any contained event overlaps a known insider activity day. A sensitivity check is also evaluated for , requiring at least k anomalous events within the window to confirm robustness. This multi-threshold criterion reduces noise from single false triggers and aligns with SOC triage practices for grouping correlated alerts [11,23].

Before labelling, timestamps are normalized to UTC, duplicates are removed, and per-user chronological order is enforced to preserve temporal consistency-standardized preprocessing steps in published CERT pipelines [11,23,29,30].

3.2. Pre-processing

Release-specific headers across CERT r1–r6.2 are normalized to a consistent schema per modality. Records are type-checked; malformed rows dropped; timestamps normalised to UTC (original offsets applied before conversion), and per-user sequences strictly ordered. Duplicate detection uses stable keys per modality:

-

Logon/Device/HTTP/File:(id) if unique, otherwise

(user, pc, timestamp[, url/filename]).

Email:(id) or (user, timestamp, to, size).

To stabilize scaling and reduce the impact of extreme values, numeric features are winsorized at the 99.5th percentile per feature (modality-specific). Numeric channels are standardized with a

StandardScaler fitted on the training fold only; fitted parameters are serialized per modality (

logon_scaler.pkl,

device_scaler.pkl,

email_scaler_stats.json) and reused at inference to guarantee SIEM parity [

11,

23]. Missing numeric values are imputed on the training fold (median or 0), then scaled using the train-fit scaler; the same imputer parameters and scaler are applied at inference.

Low-cardinality categorical (e.g., activity) fields are one-hot encoded. High-cardinality identifiers (user/host/domain) are not one-hot encoded to avoid identity leakage; instead, identity effects enter via derived aggregates (per-user rolling counts, daily uniques, recent diversity metrics) computed as numeric features.

The pipeline asserts: (i) per-user monotonic timestamps; (ii) duplicate rate below a predefined threshold; (iii) post-winsorization range validity; and (iv) monitored train/validation/test feature-mean drift.

The feature-order manifest (names, dtypes, indices) and the scaler object are versioned with each training run. Online reconstruction in Splunk validates the incoming feature vector against the manifest (shape/order/dtype) before scoring; mismatches are rejected and logged [

11,

23].

Table 2.

Canonical fields per model.

Table 2.

Canonical fields per model.

| Log file |

Canonical fields (representative) |

Count |

| logon.csv |

id, date, user, pc, activity (Logon/Logoff) |

5 |

| device.csv |

id, date, user, pc, activity (connect/disconnect) |

5 |

| http.csv |

id, date, user, pc, url, content |

6 |

| file.csv |

id, date, user, pc, filename, content |

6 |

| email.csv |

id, date, user, pc, to, cc, bcc, from, size, attachment_count, content |

11 |

3.3. Sequence Windowing and Split Protocol

For each user, events are segmented into fixed-length sequences of

events with stride

. This configuration follows the standard practice in log-based anomaly detection, where short sliding windows capture temporal dependencies while balancing computational cost [

11,

23]. It reflects how user activity in enterprise systems occurs in bursts of consecutive events that are meaningful when analyzed as sequences rather than isolated records. Training uses valid windows (no padding). Inference maintains a per-user ring buffer that emits a window for each new event; left-padding is applied only at stream start to maintain fixed length.

To ensure full coverage of all user histories while preserving uniform window length, the total number of generated windows across users is computed as:

where

is the total number of events for user

u. This summation ensures that each user contributes at least one valid window, even when

, thereby maintaining representational fairness across sparse and active accounts. It also provides an upper bound on the number of training and inference segments used by the convolutional network, consistent with sliding-window formulations adopted in prior CERT evaluations [

11,

23]. Labels for each window are assigned according to the supervised rule defined previously in Equation (1).

Splits are user-disjoint and time-aware: user partitions are non-overlapping across train/validation/test, and time blocks within each split are contiguous to avoid look-ahead. All scalers, calibration models, and operating thresholds are fitted on training (or train→validation) data only and then frozen for test and SIEM application. Any exploratory run that used a stratified window split (an early Logon experiment) is explicitly flagged in results and excluded from final claims. This protocol mitigates identity and temporal leakage commonly reported in evaluations of CERT-style corpora [

11,

23].

Short windows enable shallow temporal filters to capture local behavioural “micro-motifs” (bursts of failures, rapid host switching) while keeping per-window compute small; 1-D convolutions provide favourable latency/throughput for SIEM deployment and integrate cleanly with late-fusion heads elsewhere in the pipeline [

11,

23].

CERT’s day-level labels can misalign with event-level windows; this timing granularity may dilute precision at moderate recall and is revisited in (Threats to Validity) [

11,

23].

Behavioural biometrics are processed under consent; personally identifiable information is pseudonymized; and only derived features necessary for inference are retained in SIEM, with retention aligned to institutional policy.

3.4. Feature Engineering Overview

Each modality is transformed into fixed-length sequences of events with a standardized feature index of per step. A per-modality feature manifest (name → dtype → default → mask) preserves order for SIEM reconstruction; fields not applicable to a modality are set to neutral defaults (numeric 0, binary 0).

Common transforms include temporal encodings (hour_sin, hour_cos; day_of_week; weekend), inter-event timing (per-user z-scores), rolling activity (e.g., 5 min, 60 min), per-day totals and uniques, and winsorization (99.5th percentile) followed by scaling (train-only).

3.4.1. Logon (Event-Level, )

From logon_feature_engineered.csv:

events_last_5min, fail_count_5min

simul_login, max_events_5min, gap, max_gap

off_hours_ratio, user_pc_novel, pc_user_entropy

wkday_wkend_ratio, last3_short_cnt, last3_mean_dur, delta_last3

sess_dur_z, daily_login_z

Artifacts: logon_scaler.pkl; manifest_logon.json.

3.4.2. Device (Event-Level, )

From device_feature_engineered.csv:

device_session_duration, off_hours_device, is_weekend

file_count_to_usb, usb_file_tree_entropy

activity_encoded, inter_event_time, hour_of_day, day_of_week

Artifacts: device_scaler.pkl; manifest_device.json.

3.4.3. Email, File, HTTP, and Behavioural Biometrics

(Same structure preserved - Email/HTTP partial, Balabit mouse etc.,.)

3.5. Models and Training

All detectors optimize a binary objective under extreme class imbalance. The primary validation metric is PR-AUC (precision/recall area), with ROC-AUC and thresholded precision/recall/F1 reported for operational points. Early stopping restores the best validation PR-AUC model [

11,

23].

Training uses Binary Focal Loss with and , combined with:

negative downsampling to a target ratio (20:1 or 10:1 normal:anomaly per epoch),

class weights in the loss (heavier weight on ),

class-balanced mini-batches (per-batch pos:neg ).

For Balabit, a second stage applies hard-negative mining (oversampling genuine sessions that score highest). Threshold selection is performed post-training on a validation split.

Optimization and Regularization.

Optimizer: Adam (initial learning rate ).

Scheduler: ReduceLROnPlateau (monitor val PR-AUC, factor 0.5, patience 3, minimum LR ).

EarlyStopping: patience 6 with best-weights restore.

Typical batch sizes: 4096 windows (logs) and 128 sequences (Balabit).

L2 regularization on dense layers; Dropout in heads.

Seeds are fixed for NumPy/TF; dataset partitions, feature manifests, scaler stats, model configs, and thresholds are versioned per run. Checkpoints include weights, optimizer state, and learning-rate scheduler state; training/validation history (loss/PR-AUC) is logged to file.

3.5.1. Logon CNN (Splunk Deployed)

Backbone: Three Conv1D blocks (filters 64/128/256; kernels 3/3/5), each with BatchNorm+ReLU; MaxPool after the first two; GlobalMaxPool; Dense(128, ) → Dropout(0.5) → Dense(64, ) → Dropout(0.5) → sigmoid output.

Data pipeline: Fixed windows , stride 1; valid windows for training. Per-modality StandardScaler fitted on train only; winsorization at the 99.5th percentile applied pre-scale. Mini-batches are class balanced.

Training protocol: Focal loss with class weights; Adam + LR schedule as above; EarlyStopping on val PR-AUC. Artifacts: logon_cnn_best.keras, logon_scaler.pkl, manifest_logon.json.

Serve-time details: Splunk MLTK reconstructs the

tensor, validates feature order/dtypes against the manifest, applies the saved scaler, runs the model, then applies calibration and threshold [

32].

3.5.2. Device CNN (Splunk Deployed)

Backbone: Identical to Logon with device-specific inputs.

Stability: Seed sensitivity measured over three random seeds; results reported as mean ± sd to characterise variance under imbalance (

Table 4).

Training & serve: Same optimization and imbalance settings as Logon.

Artifacts:device_cnn_best.keras, device_scaler.pkl, manifest_device.json.

3.5.3. Email CNN (Partial; Offline)

Backbone: Same Conv1D stack over message sequences with engineered email features (scaled via email_scaler_stats.json). Training uses focal loss, downsampling, and class weights; operating threshold is chosen post hoc on validation. Artifacts: email_scaler_stats.json, manifest_email.json.

3.5.4. HTTP CNN (Partial; Offline)

Backbone: Same Conv1D stack over event-level HTTP features (URL morphology, entropy, flags, temporal). Training mirrors Email (focal loss + downsampling + class weights). Artifacts: http_scaler.pkl, manifest_http.json.

3.5.5. Balabit (Mouse), ResConv + BiLSTM (Offline)

Backbone: Two dilated residual Conv1D blocks (128 channels) → BiLSTM(64) → GlobalMax/Avg concat → Dense(128) → sigmoid.

Training regime: Two-stage procedure: Stage 1 focal loss with class weights; Stage 2 hard-negative mining (oversample genuine sessions that score highest) to depress false positives; EarlyStopping on val PR-AUC. Sequence length . Artifacts: balabit_model_v51.keras, balabit_scaler_v51.pkl, threshold_v51.json.

Justification: Convolutional filters capture short-range kinematic motifs with high throughput; the BiLSTM adds order sensitivity for behavioural rhythm. Monitoring PR-AUC aligns with SOC utility under imbalance [

11,

23].

3.5.6. Training Data Assembly and Loaders (All Logs)

Event streams are grouped by user, windowed (, stride 1), and labelled per user. Windows are shuffled within fold, stratified by label, and fed via a streaming data loader (prefetch, cache as feasible). Negative sampling is applied per epoch to maintain the target imbalance ratio, while all positive windows are retained.

3.5.7. Post-Training Calibration and Operating Thresholds (Used in Splunk)

Calibration: Validation logits are calibrated via Platt scaling (logistic regression on logits) or isotonic regression; the chosen method is recorded per model. Calibrated probabilities are used for threshold selection.

An operating threshold is selected on validation to satisfy an analyst target, either a precision target (e.g., precision ≥ 0.70) or an alerts-budget target (at most N alerts per day). The resulting is saved (logon_threshold.json) and applied unchanged to test and Splunk. Optional “2 of 3” window smoothing reduces spiky one-offs at serve time.

3.5.8. Regularisation, Ablations, and Stability Checks

Dropout (0.5) and

regularization (

) on dense layers, EarlyStopping, and ReduceLROnPlateau are used. Seeds are fixed; Device reports seed stability (mean±sd), see (

Table 4). Ablation results are not claimed; ablations are left to future work.

3.5.9. Compute and Limits

Training is performed on a single GPU workstation (or CPU for smaller runs). Batch sizes, and sequence lengths are chosen to avoid memory spill while maintaining sufficient batch diversity. Runtime constraints (HTTP/Email volume) are addressed with chunked loaders and checkpoint warm starts; reported results reflect the final converged checkpoints.

4. Results

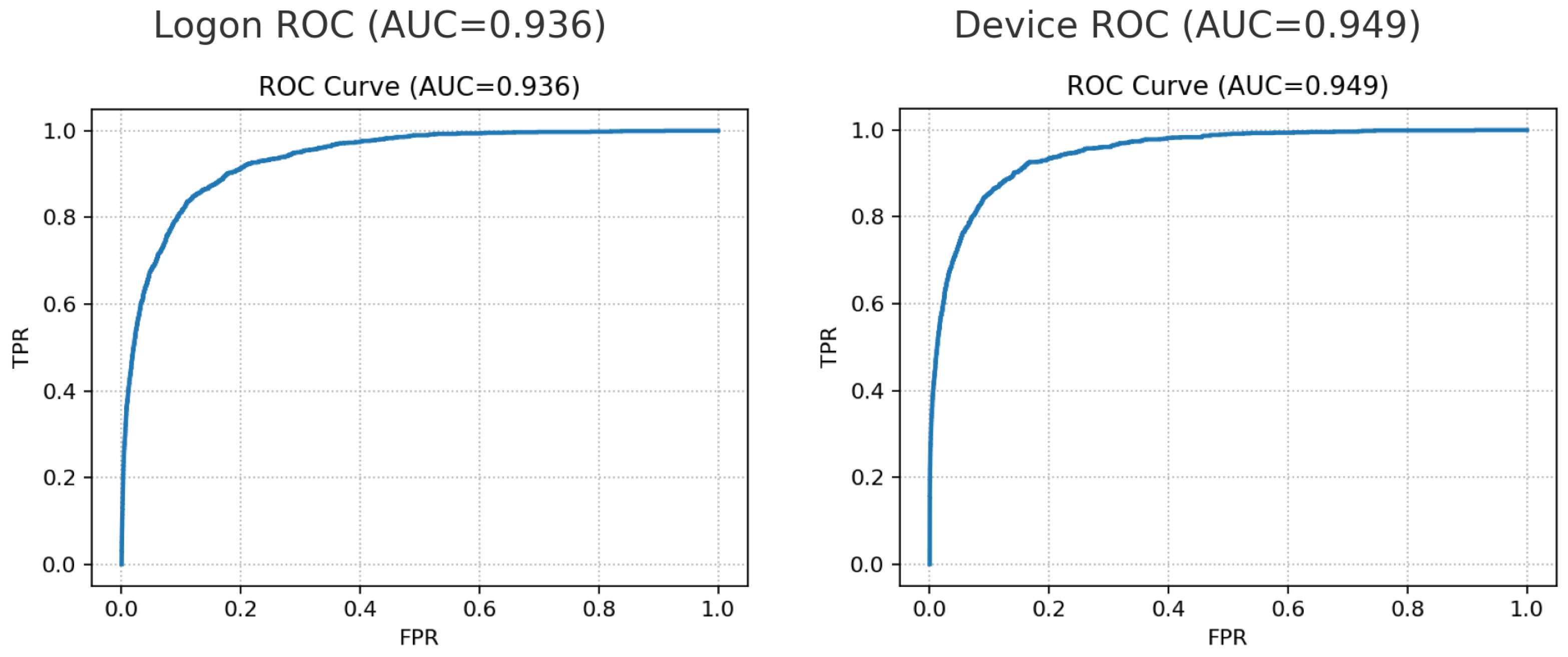

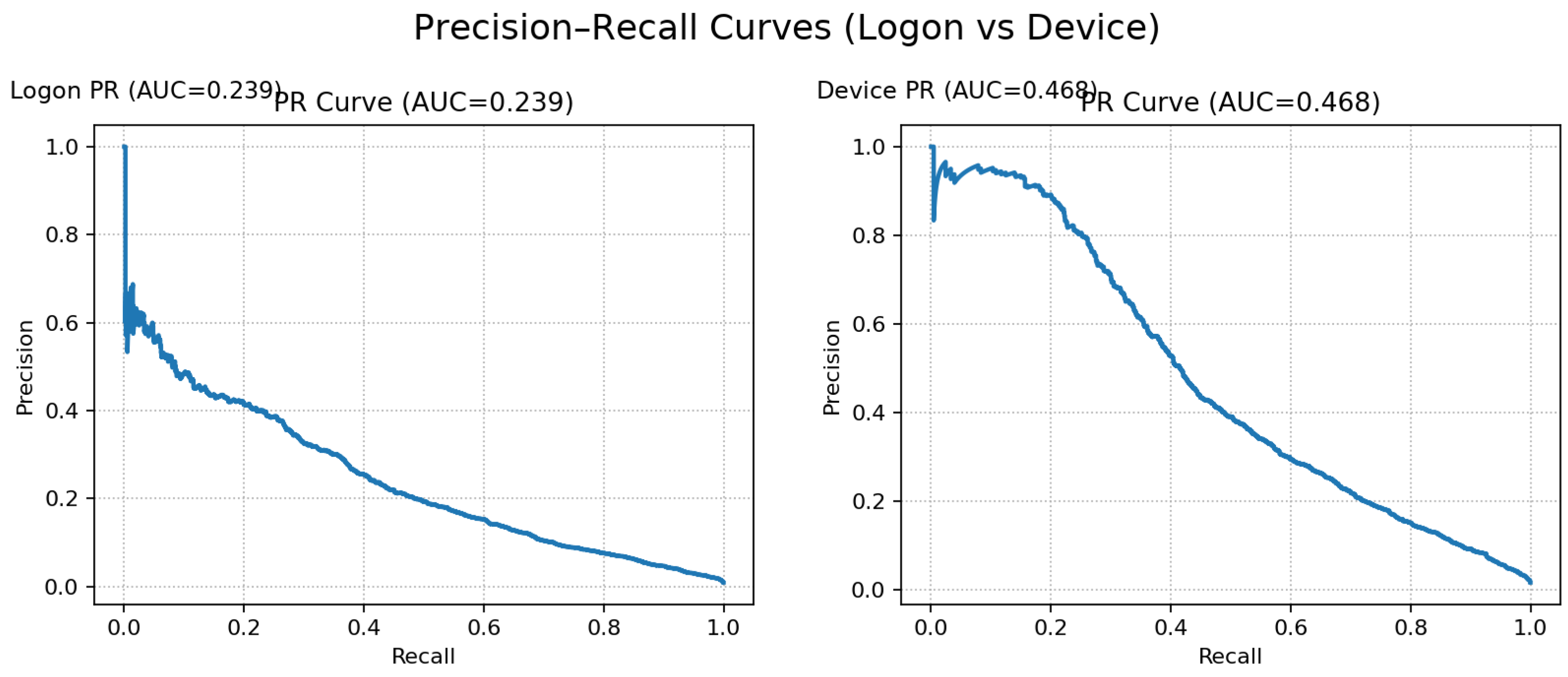

Across modalities, ROC curves are high while PR curves reflect the extreme skew of insider labels. Device achieves the strongest ranking, with PR-AUC = 0.468 and ROC-AUC = 0.949; Logon attains PR-AUC = 0.239 and ROC-AUC = 0.936.

The split between ROC and PR is expected under rare positives: both models separate classes well overall (ROC), but precision decays as recall increases on the long negative tail (PR). The paired ROC and PR panels are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Device performance is stable across three random seeds: PR-AUC =

and ROC-AUC =

(mean ± sd over seeds {13, 42, 77}). Operational recalls at fixed precision targets vary modestly (e.g., recall at

ranges

–

), indicating some variance from class imbalance but no collapse (

Table 4).

Thresholds selected on calibrated validation scores were carried unchanged to test. On Logon (), the model operates in an ultra-low-FPR regime: TN / 1 FP / FN / 3 TP, yielding Precision , Recall , and FPR . This corresponds to just four alerts over windows ( per 100k), a configuration chosen to build analyst trust by minimizing noise.

On Device (

), the trade-off is more balanced:

TN / 149 FP / 808 FN / 348 TP, giving Precision

, Recall

, and FPR

(497 alerts over

windows,

per 100k). These fixed points visualize the precision–recall/alert-volume trade-off shown in

Figure 3.

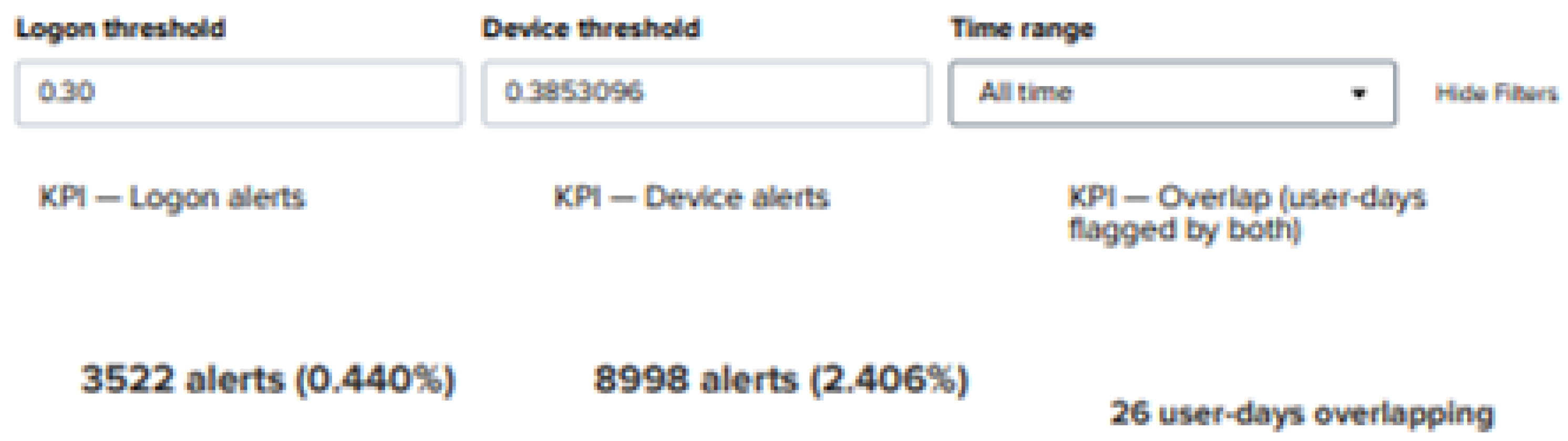

A representative Splunk deployment (with thresholds visible in the dashboard header) illustrates analyst-facing volumes and overlap: approximately

logon alerts,

device alerts, and 26 user-days flagged by both streams, with weekly overlap trends concentrated in several distinct periods (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). These screenshots are illustrative of alert budgeting and cross-stream correlation, and are not the basis of the test-set metrics summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Test-set operating points and ranking metrics.

Table 3.

Test-set operating points and ranking metrics.

| Model |

Split |

PR-AUC |

ROC-AUC |

Threshold |

Precision |

Recall |

FPR |

| Logon |

test |

0.239 |

0.936 |

0.4663 |

0.750 |

0.0020 |

|

| Device |

test |

0.468 |

0.949 |

0.4443 |

0.700 |

0.3010 |

0.0020 |

| Balabit (val) |

val |

0.867 |

0.835 |

0.0829 |

0.935 |

0.8300 |

0.0507 |

| Balabit (test) |

test |

0.409 |

0.382 |

0.0829 |

0.051 |

0.4170 |

0.4510 |

Table 4.

Device seeds and evaluation metrics.

Table 4.

Device seeds and evaluation metrics.

| Seed |

PR-AUC |

ROC-AUC |

P@50 |

P@60 |

P@70 |

| 13 |

0.468 |

0.949 |

0.416 |

0.354 |

0.301 |

| 42 |

0.457 |

0.944 |

0.397 |

0.333 |

0.289 |

| 77 |

0.406 |

0.942 |

0.340 |

0.269 |

0.204 |

Batch CPU scoring for Logon sustains

k windows/s (median/95th latency

ms per 1k windows). The device exhibits the same order of latency, given an identical backbone. The Balabit branch processes sessions in real time at a batch size of 64. These rates meet real-time SIEM requirements and leave headroom for calibration, thresholding, and logging at serve time (

Table 5).

Balabit shows a validation→test drop (PR-AUC 0.867→0.409; ROC-AUC 0.835→0.382), consistent with domain shift (hardware, surface, or task) known in behavioural biometrics. This motivates user-specific calibration or domain-robust feature construction in future work, but does not affect the SIEM-deployed Logon/Device branches.

5. Evaluation and Discussion

5.1. Evaluation Objectives and Protocol Recap

This section evaluates whether the detectors (i) achieve useful precision–recall at analyst-controlled alert budgets, (ii) remain well calibrated post-training, and (iii) meet real-time SIEM throughput constraints.

Evaluation follows the supervised windowing scheme described previously, with user- and time-disjoint splits. Models are assessed primarily by PR-AUC under extreme class imbalance, with ROC-AUC reported for comparability. Fixed operating-point metrics (Precision, Recall, FPR) are computed at thresholds chosen on a calibrated validation split, reflecting operational decision-making in SOC workflows.

5.2. Ranking Quality versus Operating Points

Ranking metrics indicate learnable signal across modalities, but actionable utility depends on calibrated operating points.

For Logon, ROC-AUC is high (0.936) while PR-AUC is modest (0.239), consistent with severe class skew. At the conservative operating threshold (), the detector attains Precision with Recall and an extremely low FPR (TN/FP/FN/TP = 158,388 / 1 / 1,530 / 3). This configuration intentionally sacrifices recall to demonstrate threshold control and build analyst trust.

For Device, the same backbone at yields Precision and Recall with FPR (73,495 / 149 / 808 / 348), providing a more balanced trade-off suitable for triage at manageable alert volume.

For Balabit (mouse dynamics), a pronounced validation→test drop (PR-AUC 0.867→0.409) suggests domain shift across hardware, surface, or task. This aligns with prior work showing that behavioural biometrics can be sensitive to capture context and population drift [

18,

21].

5.3. Calibration and Alert Budgeting

Post-training calibration (Platt or isotonic, recorded per model) improved probability reliability in reliability plots, which is critical when thresholds are expressed as analyst-controlled alert budgets.

Numerical summaries such as expected calibration error (ECE) and Brier score are deferred to future work. In this paper, thresholds are chosen on calibrated validation scores and carried unchanged to test and Splunk, ensuring predictable changes in alert volume when is adjusted.

Calibrated probabilities enable stable threshold selection. For Logon, the conservative produces four alerts over 159, 922 windows ( alerts per 100k windows); for Device, it yields 497 alerts over 74, 800 windows ( alerts per 100k windows).

In deployment, an analyst slider exposes the monotonic precision–recall versus alerts-per-day trade-off; calibration curves justify that marginal shifts to induce predictable workload changes without unexpected precision collapses.

5.4. Latency and Throughput (Operational)

On CPU, the shallow Conv1D backbones with global pooling deliver low per-window compute cost. Batch scoring for Logon sustains k windows/s (median/95th latency ms per 1k windows); Device is of the same order given the identical backbone.

Feature construction uses ring buffers and pointed windows, maintaining amortized

updates. These characteristics satisfy real-time SIEM scoring and are compatible with Splunk MLTK streaming jobs [

32].

5.5. Error Analysis and Failure Modes

False positives (Device) concentrate around legitimate high-volume removable-media workflows, often after hours and for users with sparse training history (cold start). Features such as file_count_to_usb and off_hours_device=1 dominate these alerts.

False negatives (Logon) at conservative arise when windows are short or lack discriminative context; relaxing or enabling a “2-of-3 window smoother” raises recall with a small increase in FP volume.

For Balabit, impostor sessions that mimic low-frequency kinematics (speed/acceleration envelope) while diverging in higher-order rhythm drive test errors; domain-robust kinematic summaries or per-user calibration are recommended [

18,

21].

5.6. Baselines and Comparison to Prior Work

This study does not report in-house baseline numbers for classical or sequence models. Instead, the results are contextualized qualitatively against published CERT baselines.

Classical supervised models provide competitive ROC-AUC, but struggle for precision at low FPR under strong imbalance. Sequence-aware models (BiLSTM/TCN) improve ranking at the cost of throughput, while self/semi-supervised log models such as LogBERT reduce label reliance and often improve ranking [

23].

5.7. Limitations and Threats to Validity

Internal validity: identity leakage was mitigated by user/time-disjoint splits, exclusion of raw identifier one-hots, and train-only scaling. One early Logon run using a stratified window split is excluded from claims.

Construct validity: day-level labels from CERT may misalign with event-level windows, potentially diluting precision at moderate recall.

External validity: partial ingestion for HTTP/Email and offline-only biometrics limit generalization to broader enterprise contexts. Balabit validation→test gaps indicate susceptibility to capture context and device setup.

Conclusion validity: class imbalance induces variance; seed stability (mean ± sd where applicable) should be reported. Stratified bootstrap confidence intervals for PR-AUC and operating-point metrics are recommended in the final tables.

5.8. Operational Guidance and Implications

Initial deployment should prioritize analyst trust and controllability. Run Logon in an ultra-low FPR mode to minimize noise while demonstrating calibrated control. Run the Device at a precision-targeted threshold to surface actionable triage candidates.

Expose an alerts-per-day slider and a 2-of-3 window smoother; monitor calibration drift and refresh Platt/Isotonic parameters on recent data. Collect analyst feedback (true/false alerts) to support periodic recalibration and, where feasible, per-entity thresholding.

These choices operationalize detectors in the manner advocated by sequence-aware insider threat studies and SIEM-aligned tooling [

5,

23,

32].

5.9. Future Work

Future work will complete Email and HTTP ingestion in Splunk MLTK with per-modality manifests, train-only scalers, calibration, and dashboards exposing the threshold/alerts-per-day slider.

Keystroke dynamics will be added alongside mouse dynamics to strengthen behavioural signals and enable decision-level fusion across logs and biometrics, building on continuous-authentication protocols and fusion literature [

18,

19,

21,

24].

Model fine-tuning will aim to raise PR-AUC at fixed alert budgets. Planned explorations include Conv1D depth/width (2–4 blocks; kernels 2–7; optional dilation) with residual connections; comparison of GlobalMax vs Avg vs Max+Avg pooling; and sweeps of window length/stride (, stride ).

Focal-loss settings (, ), negative down-sampling ratios, label smoothing (), and weight decay (–) will be grid-searched. Per-modality calibration (Platt vs isotonic) and per-entity thresholds will be evaluated where data volume permits.

Hard-negative mining from prior false positives/negatives will be used to sharpen margins. For biometrics, normalization for device characteristics and domain-adaptation baselines will be tested to mitigate validation→test shifts.

Longer term, self/semi-supervised pretraining on logs (masked-event objectives) will be explored to reduce feature-engineering dependence [

5,

23].

Finally, SHAP-based explainability will be integrated to attribute each alert to specific input features at window level, enabling “why” panels in the SIEM dashboard. For Conv1D branches, attributions will be computed on the pre-calibrated logits (to avoid calibration distortion) using DeepSHAP or KernelSHAP where feasible.

6. Conclusions

This study presented a calibrated, SIEM-integrated framework for insider-focused anomaly detection that fuses enterprise log analytics with behavioural biometrics under a unified, reproducible pipeline. The prototype combined compact one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1-D CNNs) for logon and device streams with a lightweight sequence model for mouse dynamics, demonstrating real-time feasibility and seamless integration with Splunk’s Machine Learning Toolkit (MLTK). The work addressed critical challenges reported in prior literature mainly data imbalance, lack of calibration, and limited operational validation by applying user- and time-disjoint evaluation, post-training calibration (Platt/isotonic), and precise control over precision–recall trade-offs through adjustable alert thresholds.

Across sections, the paper covered: (i) a review of related work on log-based insider detection and behavioural biometrics, identifying the absence of calibrated, SIEM-ready implementations; (ii) a detailed methodology describing the unified feature schema, windowing, and imbalance-aware CNN training strategy; (iii) the experimental results demonstrating strong ROC–AUC (up to 0.949) and operationally controllable PR–AUC across logon, device, and biometric modalities; and (iv) evaluation confirming high throughput (≈70k windows/s) and reliable calibration suitable for SOC deployment.

The key contributions can be summarised as follows:

Development of a calibrated, multimodal CNN framework integrating directly into a live SIEM environment.

A reproducible, imbalance-aware training and calibration process enabling stable alert budgeting for analysts.

Demonstration of end-to-end deployment feasibility in Splunk MLTK with manifest-validated feature ingestion and dashboards for alert triage and overlap analysis.

Empirical validation using user- and time-disjoint splits to ensure operational realism and prevent identity leakage.

While partial ingestion (HTTP and email) and offline-only biometrics currently limit scope, the established pipeline provides a foundation for full multimodal integration. Future work will extend the framework by incorporating keystroke dynamics for decision-level fusion, refining calibration through entity-specific thresholds, and exploring self- and semi-supervised pretraining to improve PR-AUC at fixed alert budgets. Beyond its technical scope, this research demonstrates a practical route from offline academic anomaly detection models to reproducible, SOC-ready deployment within operational Security Information and Event Management systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mohamed salah Mohamed. and Abdullahi Arabo.; methodology, Mohamed salah Mohamed.; software, Mohamed salah Mohamed.; validation, Mohamed salah Mohamed and Abdullahi Arabo.; formal analysis,Mohamed salah Mohamed.; investigation, Mohamed salah Mohamed.; resources, Abdullahi Arabo.; data curation, Mohamed salah Mohamed.; writing—original draft preparation, Mohamed salah Mohamed.; writing—review and editing, Abdullahi Arabo.; visualization, Mohamed salah Mohamed.; supervision, Abdullahi Arabo.; project administration, Abdullahi Arabo.; funding acquisition, Abdullahi Arabo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Anju, A.; Krishnamurthy, M. M-EOS: Modified equilibrium optimisation based stacked CNN for insider threat detection. Wireless Networks 2024, 30, 2819–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNN LSTM based insider threat detection model. Proc. 2025 Int. Conf. on Electrical Automation and Artificial Intelligence (ICEAAI), Guangzhou, China, 10–12 January 2025. [CrossRef]

- Narmadha, S.; Balaji, N.V. Improved network anomaly detection system using optimized autoencoder-LSTM. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 273, 126854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabadi, M.; Celik, Y. Anomaly detection for cyber security based on convolutional neural network: A survey. In 2020 Int. Congress on Human Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA); IEEE, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, I.; Han, K. Cyber threat detection based on artificial neural networks using event profiles. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 165607–165626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duary, S.; et al. Cybersecurity threats detection in intelligent networks using predictive analytics approaches. In Proc. 4th Int. Conf. on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM); IEEE: Noida, India, 23 February 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, W.S. Threat detection and response using AI and NLP in cybersecurity. Journal of Internet Services and Information Security 2024, 14, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Lv, X.; Xu, X.; Chan, S.; Choo, K.-K.R. Double layer detection of internal threat in enterprise systems based on deep learning. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024, 19, 4741–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal Vasquez, M.; Modelo Howard, G.; Dube, S.; Bhargava, B. Hunting for insider threats using LSTM based anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, P.; Yin, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, W. Insider threat detection using supervised machine learning algorithms. Telecommunication Systems 2024, 87, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, P.; Hong, W.; Yin, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, W. Optimising insider threat prediction: Exploring BiLSTM networks and sequential features. Data Science and Engineering 2024, 9, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Sarhan, B.; Altwaijry, N. Insider threat detection using machine learning approach. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shehari, T.; Al Razgan, M.; Alfakih, T.; Alsowail, R.A.; Pandiaraj, S. Insider threat detection model using anomaly-based Isolation Forest algorithm. IEEE Access 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghalizadeh Moghadam, N.; Neal, C.; Cuppens, F.; Boulahia Cuppens, N. NLP and neural networks for insider threat detection. In Proc. IEEE TrustCom, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, A.A.; Yıldırım, M.; Anarım, E. Bogazici mouse dynamics dataset. Data in Brief 2021, 36, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Yu, Y.; Fu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. An insider user authentication method based on improved temporal convolutional network. High Confidence Computing 2023, 3, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouRida, O.; Nashaat, M.; Saad, N.G.E.d. Deep learning driven user legitimacy prediction using keystroke and mouse behavioural dynamics. In 2024 Int. Conf. on Computer and Applications (ICCA); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Jha, V. Survey on continuous authentication using keystroke dynamics: Taxonomy, challenges, and future directions. Computer Science Review 2021, 40, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, V.; Budžys, A.; Kurasova, O. A decision making framework for user authentication using keystroke dynamics. Computers & Security 2025, 155, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, P.; Parida, P.; Bellamkonda, P.; Panda, M.K. Keystroke authentication using a novel RTS framework. In Proc. IEEE 4th Int. Conf. on Applied Electromagnetics, Signal Processing, & Communication (AESPC), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fridman, L.; Stolerman, A.; Acharya, S.; Brennan, P.; Juola, P.; Greenstadt, R.; Kam, M. Multi modal decision fusion for continuous authentication. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2015, 41, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Howley, E.; Schukat, M. Agent based dynamic thresholding for adaptive anomaly detection using reinforcement learning. Neural Computing and Applications 2025, 37, 18775–18791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yuan, S.; Wu, X. LogBERT: Log anomaly detection via BERT. In Proc. 2021 Int. Joint Conf. on Neural Networks (IJCNN); IEEE, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Killourhy, K.S.; Maxion, R.A. Comparing anomaly detection algorithms for keystroke dynamics. In 2009 IEEE/IFIP Int. Conf. on Dependable Systems & Networks (DSN); Estoril, Portugal, 2009; pp. 125–134.

- Dewa, Z. The relationship between biometric technology and privacy: A systematic review. In Future Technologies Conf. (FTC) 2017; Vancouver, 2017; pp. 739–748.

- Walter, W.H. Insider Threat Detection Using Neural Networks: A Statistical Comparison of the CERT Insider Threat Database; Doctor of Engineering Praxis, George Washington University, 18 May 2025; ProQuest No. 31933040.

- Palaniappan, S.; Logeswaran, R.; Khanam, S. Anomaly detection in network traffic for insider threat identification: A comparative study of unsupervised and supervised machine learning approaches. Journal of Informatics and Web Engineering 2025, 4, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Mehtre, B.M.; Sangeetha, S.; Govindaraju, V. User behaviour based insider threat detection using a hybrid learning approach. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2023, 14, 4573–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie Mellon University, Software Engineering Institute. CERT Insider Threat Test Dataset (r4.2/r6.2). Available online: https://www.sei.cmu.edu/library/insider-threat-test-dataset/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Killourhy, K.S.; Maxion, R.A. Keystroke dynamics benchmark data set. Available online: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~keystroke/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Balabit. Mouse dynamics challenge data set. Available online: https://github.com/balabit/Mouse-Dynamics-Challenge (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Splunk Inc. About the Splunk Machine Learning Toolkit. Available online: https://docs.splunk.com/Documentation/MLApp/5.6.1/User/AboutMLTK (accessed on 7 October 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).