Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Literature

Cultural Identity in Migration

Food as a Cultural Symbol

Collectivist- and Individualist- Confucianism

Empirical Research on Food and Intercultural Adaptation

Methodology

Findings

Food Socialising with Chinese People in the UK

Most of the time I eat alone. I don’t mind it, you know. But when it comes to the important days, I want to meet with people and eat together. At that time, I feel I am involved in a community and not alone anymore. We have similar experiences of studying abroad and we enjoy the mealtime together, not only eating but chatting and having someone with me.

I once ordered my favourite Kong Pao Chicken in a Chinese restaurant. But it was not as I expected, too salty, and not spicy at all. I miss Mom’s cooking.

At the beginning, I really missed the noise and warmth of eating with my family back home. Here, everyone seems to just grab a sandwich and eat alone. It felt strange and a bit sad, since meals used to mean connection for me. (extract from the second interview)

Food Socialising with Non-Chinese in the UK

Zhu (female, undergraduate student): I remember the first time I ate with a British friend. She was surprised that I like fish and chips. I guess it represents British food? But she thought I like the flavour so she taught me how to make it like using beef tallow. Well, I don’t know if I would make it myself, but it tasted good actually, and I also wanted to make her happy as this is her “home food”, right? She is a foodie as well, and we quickly found common interest.

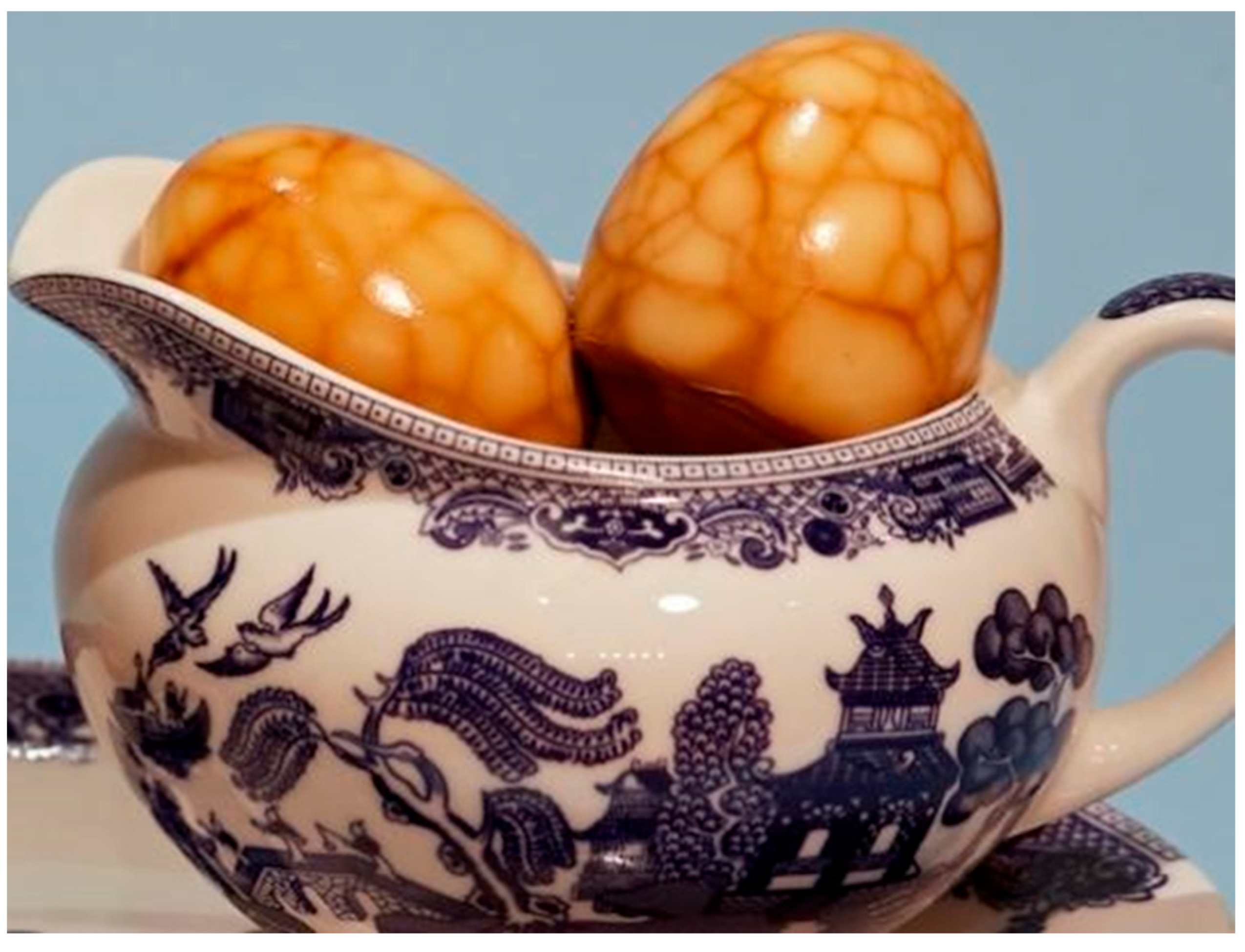

I was once invited to a student party at my teacher’s home and was surprised to be asked to bring a dish. In China, the host usually prepares the food! Confused, I asked my landlord, who said people here prefer not to share food — unlike in China, where sharing is common. So, I made a pot of tea eggs, ensuring everyone could have their own. Later, I realised it was a potluck, a concept I’d never encountered before. I was impressed by the homemade spaghetti — it tasted better than any restaurant! People also complimented my dish, and I felt proud.

I run my own business, creating short videos to bridge Chinese and Western cultures. I even found team members, like my video editor, at food events — it’s easier to connect with people over food and drinks in a relaxed setting. I first promoted my business in my dormitory kitchen, where my flatmates from different countries eagerly shared their cultures. And when there’s nothing else in common, food is always a great conversation starter. But I don’t network just for business; I also enjoy meeting people with shared interests. Some didn’t join my team, but we became good friends.

In the beginning, I refused some lunch invitations from non-Chinese classmates. They might think I am a tough person [laugh]. Actually, it wasn’t that I didn’t want to join. I just felt nervous. The menus were confusing and I didn’t want to ask what it was all the time. After a few months, I realised I was missing chances to connect, and I start knowing more about local food, so I pushed myself to go. It actually became a good way to learn about both the food and the people. (Shuo, male, Master’s student)

Food Preference and Cultural Identity

Most of the time I cook Chinese food by myself, even not as tasty as the food takeaway. I think Chinese food is healthier. It’s funny that I didn’t realise this until I came here. I don’t like the cheese food; it’s too oily. Healthy food, like salad is not delicious for me. Chinese food is a “happy medium”.

Food and Social Class

I noticed that different supermarkets have different prices, quality, and types of food. People from different backgrounds seem to shop in different places. Stores like Lidl, Morrisons, and Tesco feel more student-friendly since they’re cheaper. I sometimes go to Waitrose for things I can’t find elsewhere, like venison. Most supermarkets have a time each day when stuff gets discounted, but even the ‘bargains’ at Waitrose can cost more than full-price items in other shops. If the quality is the same, I always go for the cheaper option.

Alcohol-Related Activities

I think pub culture plays a significant role in university and social life here. For Chinese students, this might feel unfamiliar, as we’re often taught that visiting such places isn’t something “good” students do. (Ni, female, PhD student)

I once went to the London Eye with some friends, but we got split up into different pods. I thought we would be able to stick together, but it didn’t work out that way. I felt lonely in the pod at first. But it turned out to be a really great experience as I saw strangers drank champagne together and celebrated the great time in the same pod on London Eye! People were super kind and welcoming. I was barely anxious, and I felt like I was stepping out of my comfort zone in the best way. It made me realise I’m getting more open to new things.

Discussion

Conclusion

Disclosure statement

References

- Almerico, G.M. 2014. Food and identity: Food studies, cultural, and personal identity. Journal of international business and cultural studies 8: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri, M., A.J. Kruse-Diehr, J.T. McDaniel, J. Partridge, and D.B. Null. 2023. Impact of social support on the dietary behaviors of international college students in the United States. Journal of american college HealtH 71, 8: 2436–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcadu, M., M. Olcese, G. Rovetta, and L. Migliorini. 2024. “Bridging cultures through food”: A qualitative analysis of food dynamic between Italian host families and Ukrainian refugees. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 102: 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.A., S.H. Park, S. Cheng, and K.J. Chang. 2021. Comparison of consumption behaviors and development needs for the home meal replacement among Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea, Chinese college students in China, and Korean college students in Korea. Nutrition Research and Practice 15, 6: 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beagan, B.L., E.M. Power, and G.E. Chapman. 2015. ‘Eating isn’t just swallowing food’: Food practices in the context of social class trajectory. Canadian Food Studies/La Revue canadienne des études sur l’alimentation 2, 1: 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawuk, D.P. 2017. Individualism and collectivism. The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication 2: 920–929. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. 2018. Distinction a social critique of the judgement of taste. In Inequality. Routledge: pp. 287–318. [Google Scholar]

- Brindley, E.F. 2010. Individualism in early China: Human agency and the self in thought and politics. University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. 2016. Edited by A. Lindgreen and M.K. Hingley. The role of food in the adjustment journey of international students. In The new cultures of food. Routledge: pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L., J. Edwards, and H. Hartwell. 2010. A taste of the unfamiliar. Understanding the meanings attached to food by international postgraduate students in England. Appetite 54, 1: 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.K., and C. Freiwald. 2020. Potluck: Building Community and Feasting among the Middle Preclassic Maya. In Her Cup for Sweet Cacao: Food in Ancient Maya Society. University of Texas Press: pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L., and I. Paszkiewicz. 2017. The role of food in the Polish migrant adjustment journey. Appetite 109: 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C., K.C. Manning, B. Leonard, and H.M. Manning. 2016. Kids, cartoons, and cookies: Stereotype priming effects on children’s food consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology 26, 2: 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S. 2004. Eating satay babi: sensory perception of transnational movement. Journal of Intercultural Studies 25, 3: 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, J.C. 2009. The estranged self: recovering some grounds for pluralism in education. Journal of Moral Education 38, 2: 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormoș, V.C. 2022. The processes of adaptation, assimilation and integration in the country of migration: A psychosocial perspective on place identity changes. Sustainability 14, 16: 10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwertmann, D.J., and F. Kunze. 2021. More than meets the eye: The role of immigration background for social identity effects. Journal of Management 47, 8: 2074–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, C.J., and D. Ore. 2022. Landscapes of appropriation and assimilation: the impact of immigrant-origin populations on US cuisine. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48, 5: 1152–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. 2003. Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, R.I. 2017. Breaking bread: the functions of social eating. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 3, 3: 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, I., B. Stevens, P. McKeever, and S. Baruchel. 2006. Photo elicitation interview (PEI): Using photos to elicit children’s perspectives. International journal of qualitative methods 5, 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, M., K.A. Noels, and N.M. Lou. 2022. Self-determined motivation in language learning beyond the classroom: Interpersonal, intergroup, and intercultural processes. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, K., and S. Campbell. 2024. Being participatory through photo-based images. In Being Participatory: Researching with Children and Young People: Co-constructing Knowledge Using Creative, Digital and Innovative Techniques. Cham: Springer International Publishing: pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, T., L. Tibère, C. Laporte, E. Mognard, M.N. Ismail, S.P. Sharif, and J.P. Poulain. 2016. Eating patterns and prevalence of obesity. Lessons learned from the Malaysian Food Barometer. Appetite 107: 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freidenreich, D.M. 2011. Foreigners and their food: Constructing otherness in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic law. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, M.J. 2014. The Myth of Chinese Barbies: eating disorders in China including Hong K ong. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 21, 8: 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalo, J.A., and B.M. Staw. 2006. Individualism–collectivism and group creativity. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 100, 1: 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourlay, L. 2010. Multimodality, visual methodologies and higher education. In New approaches to qualitative research. Routledge: pp. 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, M., F.W. Nussbeck, and K. Jonas. 2013. The impact of food-related values on food purchase behavior and the mediating role of attitudes: A Swiss study. Psychology & Marketing 30, 9: 765–778. [Google Scholar]

- He, R., S. Köksal, H. Cockayne, and D.L. Elliot. 2025. It’s more than just food: the role of food among Chinese international students’ acculturation experiences in the UK and USA. Food, Culture & Society 28, 1: 306–324. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.M. 2021. Intercultural personhood: A non-essentialist conception of individuals for intercultural research. Language and Intercultural Communication 21, 1: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W., and D.B. Allen. 2008. Toward a model of cross-cultural business ethics: The impact of individualism and collectivism on the ethical decision-making process. Journal of Business Ethics 82, 2: 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R., T.T. Le, T.T. Vuong, T.P. Nguyen, G. Hoang, M.H. Nguyen, and Q.H. Vuong. 2023. A gender study of food stress and implications for international students acculturation. World 4, 1: 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X., and R. Whitson. 2014. Young women and public leisure spaces in contemporary Beijing: Recreating (with) gender, tradition, and place. Social & Cultural Geography 15, 4: 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y. 2001. Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., and H. Cui. 2022. On the value of the Chinese pre-Qin Confucian thought of “harmony” for modern public mental health. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 870828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstam, E., M. Mader, and H. Schoen. 2021. Conceptions of national identity and ambivalence towards immigration. British Journal of Political Science 51, 1: 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, T., C. Mohammed, and K.B. Newbold. 2017. Cultural dimensions of food insecurity among immigrants and refugees. Human Organization 76, 1: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C. 2010. Understanding the international student experience. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, N. 2019. On the engagement with social theory in food studies: Cultural symbols and social practices. Food, Culture & Society 22, 1: 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nititham, D.S. 2016. Making home in diasporic communities: Transnational belonging amongst Filipina migrants. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Parasecoli, F. 2011. Savoring semiotics: Food in intercultural communication. Social Semiotics 21, 5: 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovskaya, A.V. 2021. National identity in international education: Revisiting problems of intercultural communication in the global world. TLC Journal 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerano, J.A., and V. Riegel. 2017. Food and cultural omnivorism: a reflexive discussion on otherness, interculturality and cosmopolitanism. International Review of Social Research 7, 1: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S., J.W. Berry, P. Vedder, and K. Liebkind. 2022. The acculturation experience: Attitudes, identities, and behaviors of immigrant youth. In Immigrant youth in cultural transition. Routledge: pp. 71–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pho, H., and A. Schartner. 2021. Social contact patterns of international students and their impact on academic adaptation. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 42, 6: 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilli, B., and J. Slater. 2021. Food Experiences and Dietary Patterns of International Students at a Canadian University. Canadian journal of dietetic practice and research 82, 3: 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, R., and A. Ichijo. 2022. Food, national identity and nationalism: From everyday to global politics. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J., Ruan, and Christie. 2016. Guanxi, social capital and school choice in China. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegler, O., and B. Leyendecker. 2017. Balanced cultural identities promote cognitive flexibility among immigrant children. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T., M. Horn, and D. Merritt. 2004. Values and lifestyles of individualists and collectivists: a study on Chinese, Japanese, British and US consumers. Journal of consumer marketing 21, 5: 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurnell-Read, T., L. Brown, and P. Long. 2018. International students’ perceptions and experiences of British drinking cultures. Sociological Research Online 23, 3: 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, W. 2021. How globalisation influences perspectives on citizenship education: from the social and political to the cultural and moral. Compare: a journal of comparative and international education 51, 8: 1174–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R. 2020. Finding a Silent Voice for the Researcher: Using Photographs in Evaluation and Research1. In Qualitative voices in educational research. Routledge: pp. 72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. 2016. Individuality, hierarchy, and dilemma: the making of Confucian cultural citizenship in a contemporary Chinese classical school. Journal of Chinese Political Science 21, 4: 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., and Z.B. Liu. 2010. What collective? Collectivism and relationalism from a Chinese perspective. Chinese Journal of Communication 3, 1: 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worae, J., and J.D. Edgerton. 2023. A descriptive survey study of international students’ experiences at a Canadian University: Challenges, supports, and suggested improvements. Comparative and International Education 51, 2: 16–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P. 2013. Nonverbal communication in Mandarin Chinese talk-in interaction. Interaction. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, D.A.W., B. Cappellini, C.L. Wang, and B. Nguyen. 2018. Food consumption when travelling abroad: Young Chinese sojourners’ food consumption in the UK. Appetite 121: 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., A. Veeck, and F. Yu. 2015. Family meals and identity in urban China. Journal of Consumer Marketing 32, 7: 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalli, E. 2024. Globalization and education: exploring the exchange of ideas, values, and traditions in promoting cultural understanding and global citizenship. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research and Development 11, 1 S1: 55–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | International students in the UK are counted in the official figures under the heading of ‘student migration’, people entering in the UK on a student visa with a focus on higher education and further education (i.e., for longer term study in higher education rather than short term English language courses). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).