1. Introduction

1.1. Contemporary Context of Modern Power Systems

Over the past decades, global electricity demand has risen markedly, driven by economic growth, population increase, and rapid digitalization. Electricity now underpins industrial activity, transportation, communications, and daily life—intensifying pressures on sustainability and energy security. Recent assessments show global electrical consumption nearly doubling between 2000 and 2023, underscoring the scale of this challenge [

1,

2]. Legacy power grids, engineered around a one-way flow from centralized generation to end-users, increasingly reveal structural weaknesses under today’s operating conditions. Their dependence on large, centralized assets creates single points of failure, and cascading disturbances can propagate widely across transmission networks; restoration is often slow and costly when flexible, automated control is lacking [

3,

4,

5]. Concurrently, the energy transition—spurred by climate imperatives and the finite nature of fossil resources—has accelerated the deployment of renewable energy technologies. While clean and effectively inexhaustible, variable resources such as solar and wind introduce intermittency that complicates real-time balancing. Without adequate storage and advanced control, conventional grids struggle to maintain stability and quality of supply [

6,

7]. Against this backdrop, smart grids and microgrids have emerged as pragmatic solutions. By integrating distributed renewables with storage and intelligent control, they optimize power flows, shorten recovery after disturbances, and support decentralized, autonomous operation—including islanding when needed—thereby enhancing system resilience [

1,

8,

9].

1.2. The Challenge of Power Outages

Electricity outages (aka blackouts) remain among the most severe threats to modern energy systems. They arise from extreme natural hazards, network overloading, equipment failures, and cyberattacks—risks that are amplified by the rapid digitalization and interconnection of grid assets’ Ensuring cyber-physical security is therefore inseparable from system reliability [

10,

11,

12,

13]. The growing intensity and frequency of severe weather compound outage risk, with multiple studies identifying weather as a leading driver of grid unreliability (e.g., ≈56% in some regions). Extreme events increase operational uncertainty and stress restoration capabilities unless resilience measures are in place [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Outages carry substantial economic and social costs—lost production, equipment damage, higher operating expenditures, and public safety impacts. Case evidence from national blackouts and major storms shows large direct losses and persistent ripple effects across communities and industries [

18,

19]. Because critical infrastructures (e.g., energy, water, transport, health) are tightly interdependent, a single physical or cyber incident can cascade across sectors, complicating both failure dynamics and recovery pathways [

20,

21]. Accordingly, blackout prevention and supply continuity are no longer purely technical aims; they are foundational to national security and macroeconomic stability, demanding integrated cyber-physical defense and resilient operations [

10,

22].

1.3. The Importance of Energy Resilience amid Climate Change and Digitalization

Energy resilience is the capability of a power system to withstand, adapt to, and rapidly recover from disruptive events while continuing to deliver electricity safely and sustainably. In contemporary grids, resilience has become a central policy and engineering objective, complementing—but going beyond—traditional reliability by explicitly accounting for disturbance absorption, adaptive response, and recovery dynamics [

23,

24]. Climate change is intensifying the incidence and severity of extreme weather—storms, floods, and heatwaves—that damage energy infrastructure and trigger system imbalances. These high-impact, low-frequency events expose the limits of legacy networks unless resilience measures and investment frameworks are integrated into planning and operations [

15,

25]. In parallel, rapid digitalization delivers major gains in efficiency, monitoring, and control, but also expands the cyber-attack surface of smart grids. Ensuring cyber-physical security is therefore inseparable from resilience, requiring coordinated requirements, threat modeling, and countermeasures across communication, control, and protection layers [

10,

23,

26]. Accordingly, building resilience entails: (i) protecting critical infrastructure via advanced cybersecurity and secure-by-design communications; (ii) integrating renewable generation with BESS to bolster local autonomy and ride-through capability; and (iii) deploying microgrids that can operate in islanded mode during major disturbances. Evidence shows that PV–BESS microgrids enhance continuity of supply, shorten recovery, and support self-healing and fast reconfiguration, particularly when underpinned by standards-based communications (e.g., IEC 61850:2025 SER) [

8,

9,

27]. This paper advances prior blackout-prevention studies by proposing a unified, resilience-oriented assessment for PV–BESS microgrids facing both physical and cyber disturbances.

We combine quantitative indicators—VDI to capture voltage quality, ENS to measure unmet demand, and a Global Resilience Index (GRI) derived from recovery curves—with qualitative analysis of recovery dynamics, yielding an integrated framework to characterize hybrid system performance and validate control strategies aimed at strengthening stability [

28,

29,

30,

31].

1.4. Literature Gap Analysis

A review of recent work reveals several gaps that motivate this study: (i) a limited cyber–physical perspective that treats power and communications in isolation; (ii) fragmented metrics that hinder cross-study comparison; (iii) reproducibility constraints stemming from proprietary models, data, and non-standardized scenarios; and (iv) under-examined communication-loss events and Energy Management Systems (EMS) fallback behavior.

(i) Most works address physical events (faults, switching, load variations) while underrepresenting the cyber dimension—communication faults, data integrity issues, and control-layer compromises—in resilience analysis.

(ii) Few models integrate static indicators (e.g., VDI, ENS) with time-resolved metrics (recovery time, restoration slope) and composite, area-based indices within a single, coherent assessment framework.

(iii) A significant share of studies relies on bespoke or partially specified models, limiting comparability and replication across research groups.

(iv) The influence of communication degradation or loss on droop-based hierarchical control—especially in inverter-dominated microgrids—remains insufficiently documented, with scarce co-modeling of control dynamics and network impairments.

1.5. Aim, Objectives and Contributions of the Study

The primary aim of this work is to prevent major blackouts and to enhance the stability and resilience of the power system by designing and analyzing an intelligent PV-BESS microgrid integrated into a modern IEEE 33-bus distribution network.

To achieve the aims mentioned, the study pursues the following specific objectives:

a) Analyze the microgrid concept and its role within smart grids;

b) Identify the principal causes of outages and vulnerabilities of conventional grids;

c) Examine renewable-integration technologies with emphasis on stability and efficiency;

d) Propose a PV–BESS microgrid architecture that ensures supply continuity and local energy balance;

e) Assess the impact of microgrid deployment on power system security and performance;

f) Investigate cybersecurity treats and formulate measures to strengthen resilience;

g) Formulate recommendations for the broader integration of microgrids into national energy infrastructure.

Synthesizing the gap analysis, the paper advances the field through the following contributions:

Develops an integrated cyber–physical resilience methodology that unifies static, temporal, and composite indicators.

Applies the framework to a standard, reproducible benchmark (IEEE 33-bus)—with PV at bus 6 and BESS at bus 18—to support transparent comparison.

Quantifies performance for two representative contingencies—loss of the main supply and a communication failure triggering local operation—evaluating impacts on stability and ENS, together with recovery dynamics and a composite resilience index.

This work thereby clarifies the interactions between the physical and digital layers of a microgrid and—through simulations on the IEEE 33-bus feeder—demonstrates how PV–BESS integration can reduce voltage deviations and ENS following disturbances. In essence, the paper proposes a resilience assessment method for PV–BESS microgrids and validates it on a reproducible IEEE 33-bus model subjected to two representative perturbations: loss of the main supply and a communication failure.

1.6. Article structure

This article is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the microgrid test system and simulation setup, including network topology and component parameters (lines, transformers, PV units, and BESS).

Section 3 details the resilience assessment framework and the disturbance scenarios considered.

Section 4 reports and interprets the simulation results with respect to system stability and recovery.

Section 5 concludes and outlines future research directions for integrating smart microgrids into modern power networks.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Related Works

2.1. Microgrid Architecture and Control

Microgrids are local energy subsystems that can operate either grid-connected or in islanded mode to ensure continuity of supply—especially for critical loads—during upstream disturbances. A typical microgrid couples Distributed Energy Resources (DER), BESS, and controllable loads over low- or medium-voltage networks [

32,

33].

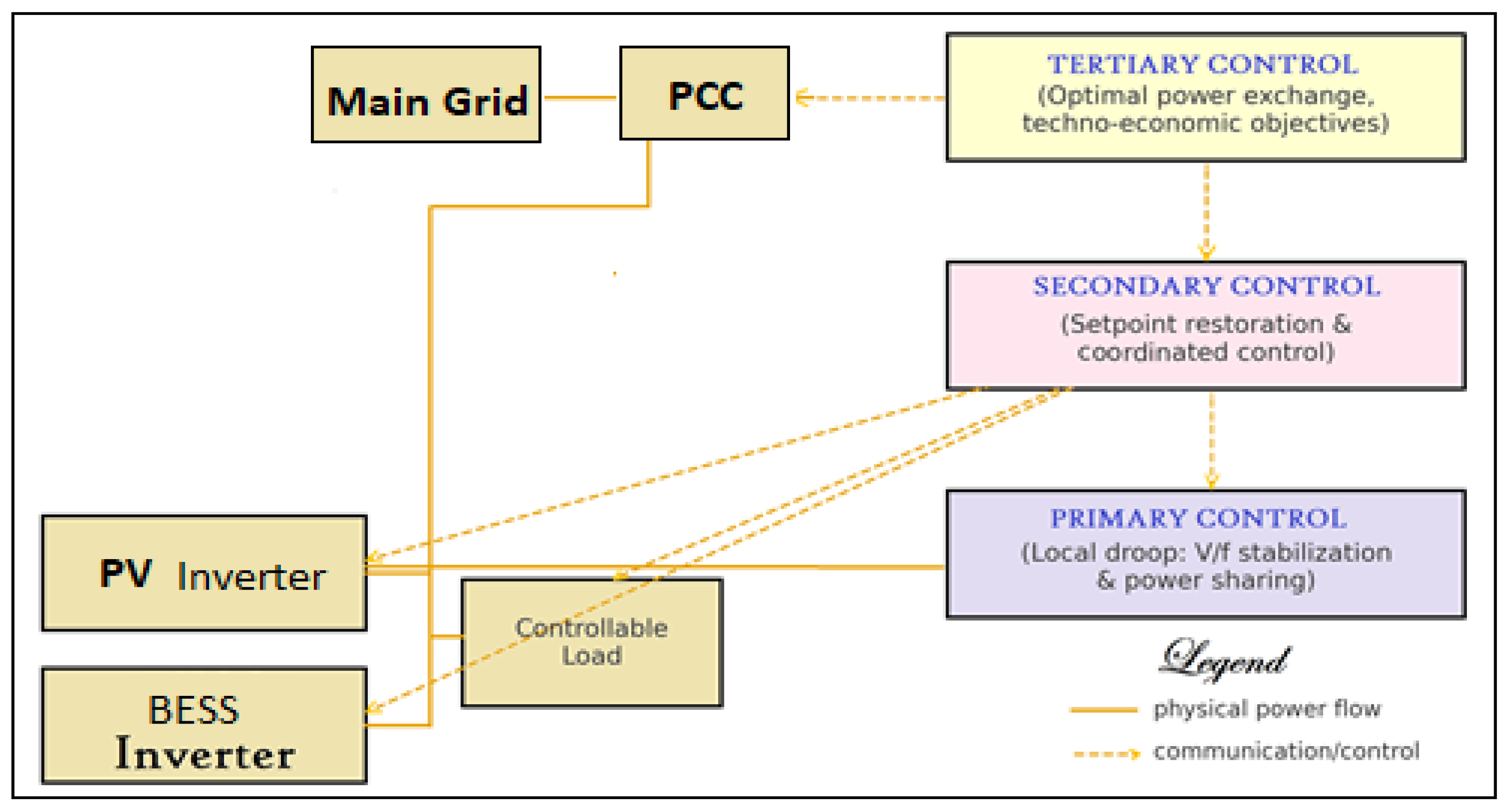

Control is commonly organized hierarchically in three layers as shown in

Figure 1. Primary control acts locally (converter level) with fast dynamics to stabilize voltage and frequency and to share power—most often via droop characteristics. Secondary control coordinates multiple units (usually through communications) to restore nominal setpoints and correct power-sharing errors introduced by primary droop. Tertiary control optimizes power exchange between the microgrid and the main grid, considering technical and economic objectives. This layered structure enables stable, flexible operation and facilitates the integration of intermittent renewables [

32,

34].

Figure 1 shows a PV inverter and a BESS inverter feeding a controllable load and interfacing at the Point of Common Coupling (PCC) with the main grid, while hierarchical primary–secondary–tertiary control layers supervise via dashed communication/control links and solid lines indicate physical power flow.

Recent studies highlight the benefits of adaptive droop—e.g., compensating impedance-induced sharing errors, mitigating circulating currents, and balancing battery state-of-charge—thereby improving voltage/frequency regulation and resource utilization [

35,

36]. To enhance scalability and resilience, distributed/multi-agent secondary control architectures have been proposed, enabling peer-to-peer coordination, plug-and-play capability, and reduced dependence on centralized controllers [

37,

38,

39]. However, greater reliance on communications introduces cyber-physical risks: link failures, latency or jitter, and time-synchronization errors can degrade control performance or be exploited by adversaries. Therefore, robust cybersecurity, QoS-aware networking, and secure time synchronization must be integrated into the microgrid control design [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

2.2. Resilience Indicators and Metrics in Distribution Systems

In distribution networks, resilience denotes the ability to absorb shocks, adapt, and restore acceptable service within a reasonable time. Unlike reliability—which focuses on the likelihood of fault-free operation—resilience explicitly captures post-event recovery and the dynamics of performance degradation and restoration. Reviews of power-system resilience emphasize this distinction and the need for metrics that cover both the event and recovery phases [

24,

45,

46].

Resilience metrics are commonly grouped into three categories:

These quantify the immediate technical impact of a disturbance. Two widely used examples are the VDI, which aggregates per-bus voltage deviations from 1 p.u., and ENS, which measures unserved energy during fault handling and restoration [

47,

48].

- (ii)

Temporal indicators.

These capture the duration and pace of recovery, such as recovery time to restore nominal operating points and the restoration slope (rate of performance improvement). Temporal metrics are typically derived from resilience performance curves (e.g., triangle/trapezoid representations) that describe degradation and recapture over time [

49,

50].

- (iii)

Composite (synthetic) indicators.

These integrate performance over time—for example, the area-based resilience index using the ratio between the integral of an ideal (target) performance trajectory and the actual trajectory during and after the event, or equivalently the “lost performance area.” Such indices capture both severity and recovery quality in a single value [

27,

49].

Recent work increasingly couples these electrical metrics with cyber–physical factors, integrating communication-network status and control-layer behavior (e.g., delays, data loss, or compromises) into resilience assessment for microgrids and distribution systems. This reflects the practical observation that communication degradations can materially affect restoration dynamics and service continuity [

50,

51,

52].

Despite progress, many studies still emphasize static or snapshot measures (e.g., voltage profiles, ENS minimization) and under-represent dynamic inverter–grid interactions and control-layer effects in the composite indices—highlighting a continuing gap that motivates integrated, time-resolved, cyber-physical resilience metrics [

53].

2.3. Cyber Threats in Microgrids and DER Systems

With increasing digitalization, microgrid control loops depend on communication networks and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition/Energy Management Systems (SCADA/EMS) layers, which broadens the attack surface and exposes DER-rich systems to cyber–physical risks [

40,

54,

55].

The most frequently reported threat classes include:

Denial-of-Service (DoS)—flooding or delaying packets that disrupt coordination and degrade synchronization among units and controllers. DoS has been documented as a practical vector against restoration processes and as a driver of instability when delays/jitter accumulate [

40,

42].

False Data Injection (FDI)—spoofed measurements or commands that mislead estimators and controllers, inducing incorrect setpoints, power-sharing errors, and voltage violations [

56,

57,

58].

FDI attacks tamper with measurement or command data so that estimators/controllers infer an incorrect system state without triggering basic bad-data detection. In the standard linear model z=Hx+e, an attacker crafts a vector a=Hc to produce z′=z+a, shifting the estimated state to x′=x+c while preserving residual tests. In microgrids, FDI can bias micro–Energy Management System/ Distribution Management System (μEMS/DMS) decisions (e.g., dispatch, voltage/reactive control), mis-share power among inverters, or drift BESS state-of-charge—producing voltage violations and unnecessary islanding.

Loss of synchronization—stemming from impaired or compromised time-sync channels (e.g., Global Positioning System time and Precision Time Protocol, IEEE 1588 - GPS/PTP) or excessive communication latency, which undermines converter phase locking and coherent control actions [

59].

Replay and Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks on IEC 61850 fast messaging for protection and control (Generic Object-Oriented Substation Event/Sampled Values/ Manufacturing Message Specification - GOOSE/SV/MMS): adversaries capture and resend (or alter) protection/automation frames to trip breakers, change statuses, or issue stale commands, undermining coordination and protection selectivity [

60,

61,

62]. GOOSE is a peer-to-peer, Layer-2 multicast, hard real-time for protection/control protocol and the base GOOSE/SV lack of encryption. MMS (IEC 61850-8-1) is a client–server protocol over TCP/IP for configuration and metering, of non-time-critical data.

Tabel 1 shows the roles and characteristics of GOOSE, SV, and MMS in IEC 61850-based microgrids, and provides an engineering checklist for a robust process bus.

Table 1.

GOOSE vs SV vs MMS (IEC 61850).

Table 1.

GOOSE vs SV vs MMS (IEC 61850).

| Attribute |

GOOSE (IEC 61850-8-1) |

SV (9-2 / 61869-9) |

MMS (IEC 61850-8-1) |

| Purpose |

Time-critical events (trip, interlock, block, status). |

High-rate digitized CT/VT measurements over process bus. |

Client-server supervision, configuration, non-time-critical data. |

| Transport |

Layer-2 multicast (publisher/subscriber), event-driven with re-transmit. |

Layer-2 multicast; periodic streaming (e.g., 80 s/c @50 Hz ≈ 4 kS/s). |

TCP/IP (ISO over TCP); request/response sessions. |

| Latency target/ determinism |

≤3 ms end-to-end on engineered LAN for protection use-cases. |

Sub-millisecond budget with deterministic delivery and tight jitter. |

Seconds to hundreds of ms acceptable; not for sub-ms protection. |

| Payload |

Status/commands from protection and bay IEDs (datasets). |

Instantaneous i(t), v(t) from Merging Units; time-aligned via PTP/GPS. |

Measurements, logs, settings, file transfer; operator/HMI access. |

| Timing model |

Event-driven; sequence numbers and retransmission for reliability. |

Strictly periodic; consumers compute phasors, power, protection. |

Polled or report-controlled; non-deterministic relative to GOOSE/SV. |

| Typical use |

Transfer-trip, load shedding, fast interlocking, islanding commands. |

Differential/line protection, wide-band control, Power-Quality Analytics PQA. |

SCADA/EMS/DMS integration; engineering and commissioning. |

| Profiles / references |

IEC 61850-8-1 (GOOSE); IEC 62351-6 (security); IEC 61850-90-5 (R-GOOSE). |

IEC 61850-9-2 / IEC 61869-9 (SV); IEC 61850-9-3 & IEEE C37.238 (PTP). |

IEC 61850-8-1 (MMS mapping); IEC 62351 (TLS, RBAC). |

Load-Altering Attacks (LAA) - coordinated manipulation of many controllable loads (or prosumer devices) to force frequency excursions or stress voltage regulation; effective even when generation is uncompromised [

63,

64].

In case of LAA, instead of faking data, the attacker changes real demand by coordinating many controllable loads (or prosumer devices/EV chargers) to inject a fast net power step Δ

PLAA(

t)

in steady state (with D

tot the aggregate droop/damping), while the transient Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) depends on synthetic/virtual inertia and primary response. Well-timed LAAs can saturate BESS or trip protection even when measurements are honest.

In

Table 2 there is a comparison of FDI and LAA in microgrids and DER systems.

While LAA exploits physical demand, FDI exploits data integrity. Both can cause significant voltage/frequency excursions under hierarchical control. Resilience-oriented countermeasures combine secure/low-latency communications (IEC 62351), robust/dynamic state estimation with physics-based checks, rate-limited and cryptographically authenticated setpoints/DR signals, anomaly detection on load ensembles, and fallback local control modes.

Setpoint/command tampering (actuator attacks) - compromised higher-level controllers or gateways push malicious power/voltage/frequency setpoints to inverters, upsetting primary/secondary control and power sharing [

52,

65].

Malware, ransomware, and supply-chain/firmware attacks on smart inverters and gateways - exploitation of weak update mechanisms, unsigned firmware, or third-party components enables remote hijacking, data theft, or extortion; secure boot and signed updates are emphasized as countermeasures [

66,

67,

68,

69].

Global Navigation

Satellite System (GNSS)

/ PMU time attacks beyond generic “loss of sync” - targeted GNSS jamming/spoofing and broader Time Synchronization Attacks (TSA) corrupt timestamps (e.g., PMU/PLL alignment), leading to erroneous phase angles and mis-coordination across agents [

69,

70,

71,

72].

Coordinated cyber-physical attacks (CCPA): multi-stage campaigns combining cyber manipulation with physical contingencies to maximize disruption and hinder restoration, increasingly discussed in integrated-energy contexts [

22].

Empirical and simulation studies show that these attacks can produce significant voltage and frequency deviations even under hierarchical control, by distorting feedback signals, desynchronizing grid-following converters, or starving secondary controllers of timely data [

62,

64,

65,

66].

Accordingly, resilience-oriented control is required: secure, low-latency communications; controller designs that tolerate delay and data loss; and fallback/local modes to sustain stability under partial or compromised connectivity [

54,

55,

66,

67,

68,

69].

These attack vectors are shown—experimentally and via co-simulation—to cause significant voltage/frequency deviations, mis-trips, and unstable power-sharing even under hierarchical control, by distorting measurements/commands, desynchronizing grid-following converters, or starving secondary controllers of timely data [

60,

71]. Accordingly, resilience-oriented control should combine secure, low-latency communications, delay/loss-tolerant control, signed firmware and secure boot, anomaly/trust-based detection for replay/FDI/LAA, and fallback local modes to sustain stability under partial or compromised connectivity [

40,

52,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69].

2.4. Standard Test Models (IEEE Test Feeders) as Reproducible Benchmarks

To validate control algorithms and assess resilience, the research community widely adopts IEEE test feeders, which provide a common baseline for comparison and reproducibility.

The most frequently used feeders are:

IEEE 13-bus feeder — an unbalanced three-phase model suited to studies of protection coordination, power quality, and unbalanced load effects.

IEEE 33-bus feeder — a medium-voltage radial network commonly used for optimization studies, PV/BESS integration, and loss evaluation.

IEEE 69-bus feeder — a larger radial system employed to test scalability and the behavior of algorithms on extensive distribution networks.

Among these, the IEEE 33-bus feeder offers a practical balance between complexity and clarity. It is usually implemented in MATLAB/Simulink, OpenDSS, and DIgSILENT. In this work, placing a PV unit at bus 6 and a BESS at bus 18 becomes a realistic scenario for evaluating microgrid behavior under disturbances, enabling consistent comparison of stability and resilience metrics across operating conditions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Test System: IEEE 33-Bus

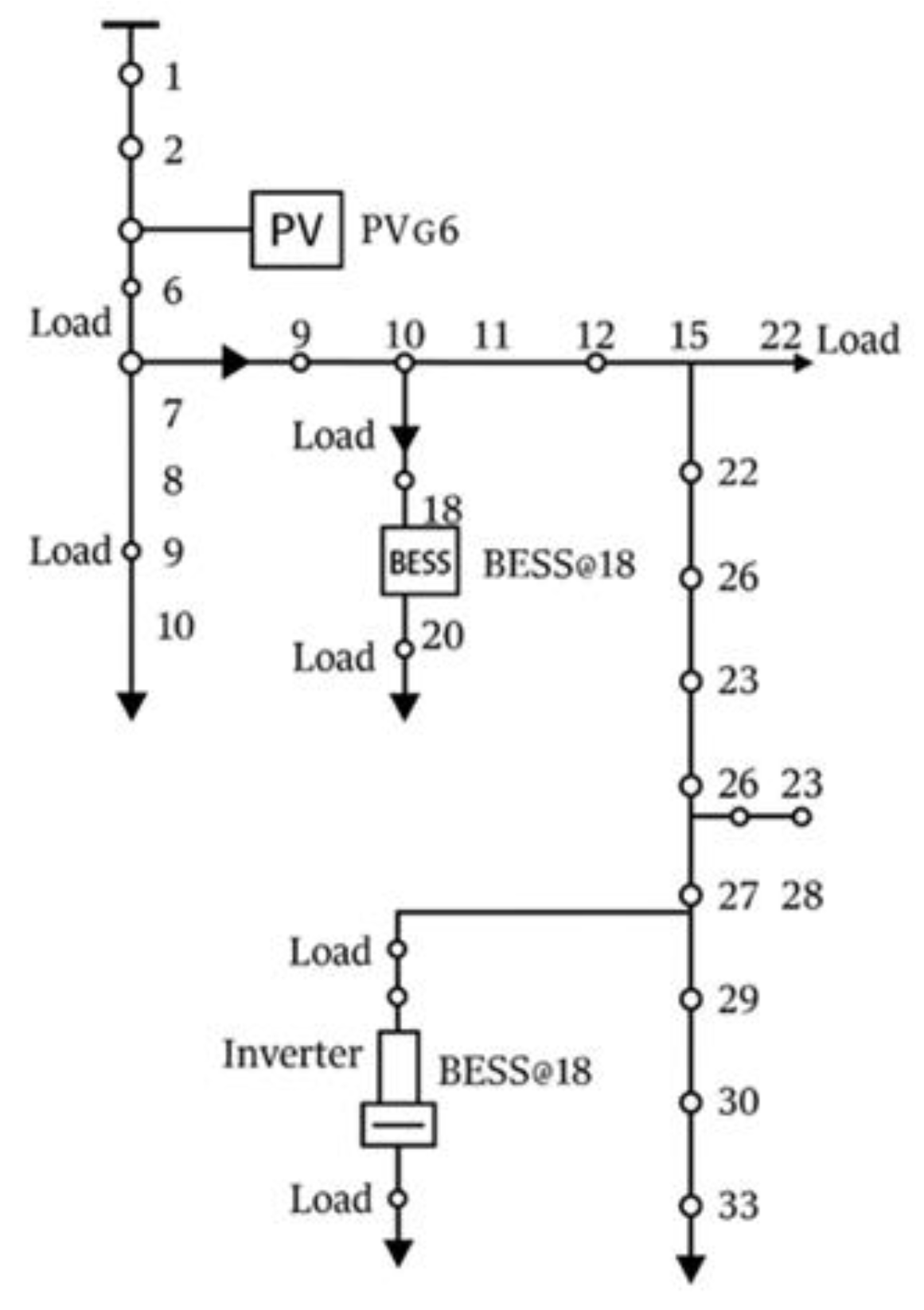

To analyze the resilience and stability of the proposed microgrid, we adopt the standard IEEE 33-bus distribution feeder, widely used in the literature for medium-voltage studies and for testing control and network reconfiguration algorithms. The microgrid retains the feeder’s radial topology at a nominal voltage of 12.66 kV, comprising 33 buses and 32 interconnecting lines. Bus 1 serves as the PCC, tied to the upstream grid through a distribution transformer.

To enable operation in both grid-connected and islanded modes, the base model is extended with two DERs:

a PV inverter at bus 6 with nominal apparent SPV power SPV;

a BESS with a bidirectional inverter at bus 18 with nominal apparent power SBESS

These resources play complementary roles:

the PV unit supplies active power from solar generation, reducing dependence on the upstream source;

the BESS provides power balancing and voltage/frequency support during islanded operation, acting in grid-forming mode when the microgrid separates from the main grid.

Loads are modeled as constant-PQ, with active and reactive powers taken from the IEEE benchmark dataset. For several representative buses (e.g.7,14,25,30), hourly demand profiles for a typical summer day (0–24 h) are assigned to capture time-varying behavior and to co-vary with renewable production.

To evaluate resilience to loss of the main supply, an automatic islanding scheme is implemented. Upon detecting disconnection of line 1–2 or the supply transformer, the breaker at bus 1 opens and the BESS immediately assumes the primary voltage source role. A microgrid EMS coordinates the transition between operating modes and regulates active/reactive power flows according to the battery SoC and solar irradiance. This setup provides a reproducible baseline for assessing both steady-state quality and post-disturbance recovery.

Figure 2 consists of a single-line diagram of IEEE 33-bus microgrid with PV connected to bus 6 and BESS connected to bus 18.

The technical parameters of the lines, transformer and connected equipment were taken from the IEEE standard dataset, with additions related to DER systems. The relevant data is summarized in the

Table 3, which forms the basis for power flow calculations and simulation scenarios.

Table 3 summarizes the baseline IEEE 33-bus microgrid: the feeder operates at 12.66 kV and includes 33 buses linked by 32 lines in a radial arrangement. The aggregated demand is

Ptot+

jQtot=3.715+

j2, 300 MVA (i.e., ∣

S∣≈4.37 MVA, pf ≈ 0.85 lagging), representative of a typical distribution network. Distributed resources comprise a PV plant at bus 6 with inverter apparent-power rating

SPV=0.9 MVA (up to 1.0 MWp DC, implying modest DC/AC oversizing) and a BESS at bus 18 rated

SBESS=0.8 MVA with 1.6 MWh energy capacity operated between 20–90% SoC. The source transformer (

ST=5,0 MVA) is located at bus 1, serving as the main substation and PCC to the upstream grid.

3.2. PV and BESS Models

To analyze the microgrid’s dynamic behavior and assess its energy resilience, we implement detailed models for the PV source and the BESS. Both are interfaced to the medium-voltage (12.66 kV) bus through controlled, bidirectional three-phase power converters that enable two-way power flow among the grid, the PV source, and the BESS. The interfaces are smart-grid compatible and can operate either in grid-following or grid-forming mode, depending on system conditions.

3.2.1. PV System Model

The PV system located at Bus 6 is modeled with a grid-following inverter whose primary function is to inject active power into the grid as a function of solar irradiance and cell temperature. Active-power control is achieved via a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) loop, which continuously adjusts the operating point to maximize conversion efficiency.

The active power generated by the PV array is computed using a standard irradiance–temperature scaling of the standard test conditions:

where

is the inverter efficiency,

is the plane-of-array instant solar irradiance instantanee (W/m²),

is the total surface of the pannels, and

is the fill factor.

Reactive-power control of the PV inverter is handled by a Volt/VAR (droop) law that keeps the local voltage within acceptable limits by modulating the reactive power flow:

Where

V is the measured bus voltage (p.u.),

V0 is the voltage set-point (p.u.),

Q is the inverter reactive power (Mvar or p.u.),

Q0 is the neutral operating point (often 0),

nQ is the reactive droop gain (p.u. voltage per p.u. reactive power), tuned to the loading conditions.

, –nominal values for frequency and power,

, – droop slopes for active and reactive power, respectively (units e.g., Hz/MW and p.u./MVAr or p.u./p.u.

with imposed limits:

where is the charging/discharging efficiency (for the BESS model) and

is the nominal energy capacity of the battery.

3.2.2. The EMS

The microgrid control architecture is hierarchical, comprising three levels:

1. Primary control – implemented locally in the PV and BESS inverters, based on droop laws for voltage and frequency regulation (P–f and Q–V droop);

2. Secondary control – removes steady-state deviations and rebalances energy among sources/loads (e.g., PI restoration of f and V, slow SoC biasing for BESS);

3. Tertiary control / EMS – optimizes power dispatch over a prediction horizon to minimize a total operating cost under network and device constraints:

where

is the voltage deviation index,

is the unpowered energy,

is the operational cost, and

are weighting coefficients.

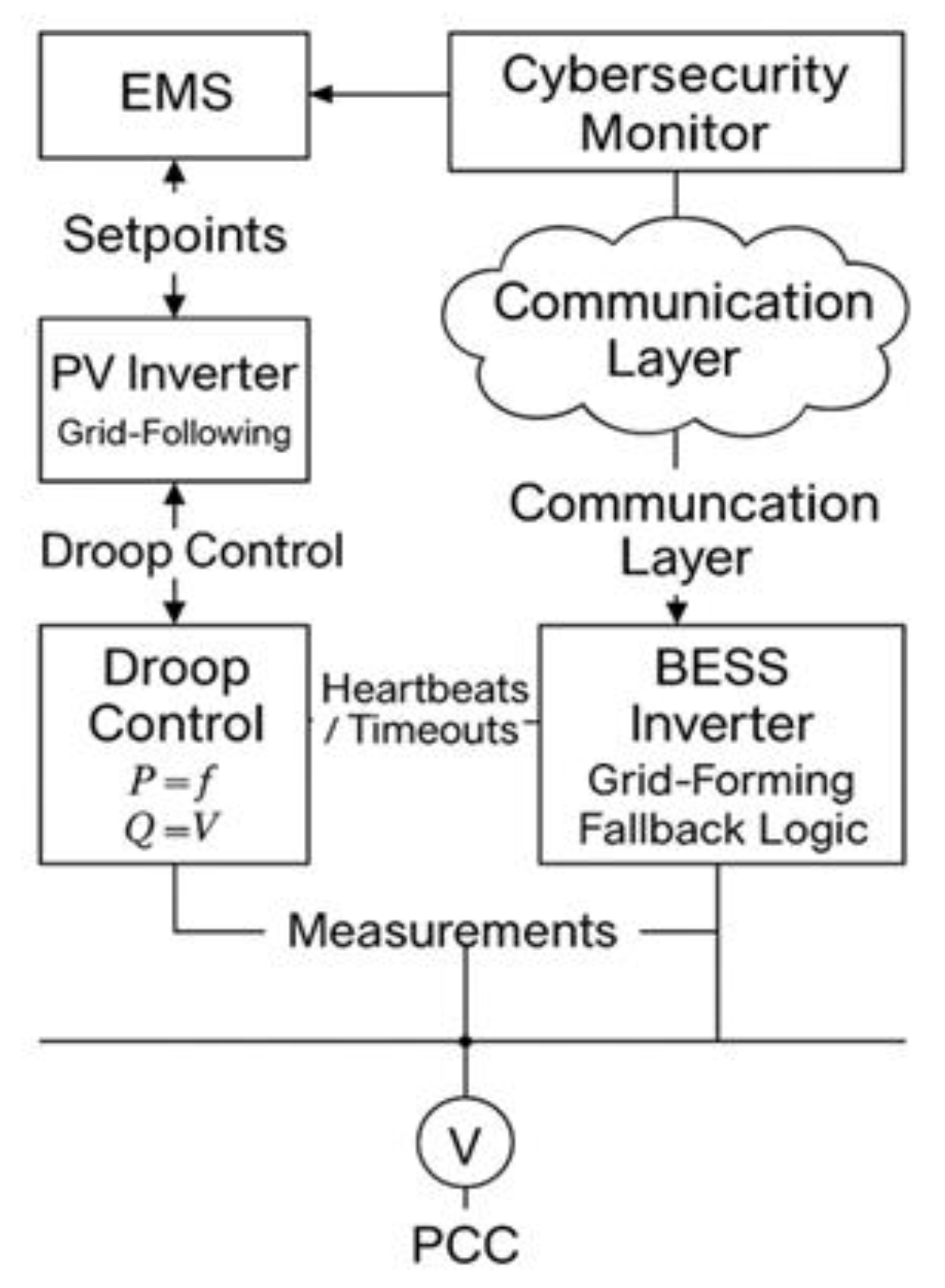

The proposed hierarchical control architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3, highlighting the interaction between the EMS, the communication layer, the local controllers of the PV inverters and BESS, as well as the security and resilience logic implemented through heartbeats, timeouts and fallback mechanisms.

This structure allows maintaining the stability of the microgrid even under conditions of cyber disruption or temporary loss of connection to the main grid.

3.3. Disturbance Scenarios

To evaluate the dynamic behavior and resilience of the proposed IEEE 33-bus microgrid, two representative disturbance scenarios were defined, covering both physical phenomena (power losses) and cyber threats (communication failures).

These scenarios allow the analysis of the microgrid’s ability to maintain its stability and continuity of power supply under critical conditions, by activating local control mechanisms and fallback/resynchronization logic.

3.3.1. Scenario D1 – Loss of Main Supply at Bus 2

In this scenario, a sudden interruption of the main grid supply is considered, by opening line 1–2 at time t=tf.

The event simulates a physical failure (e.g., a fault on the medium voltage line) that causes the microgrid to be separated from the central system.

After disconnection from the grid, the PCC circuit breaker opens automatically, triggering the controlled islanding sequence.

In this regime, the storage system (BESS) switches from grid-following to grid-forming mode, becoming the main voltage and frequency source for the microgrid. At the same time, the PV inverter continues to operate, adapting its operating point according to the solar irradiance and the frequency signal imposed by the BESS.

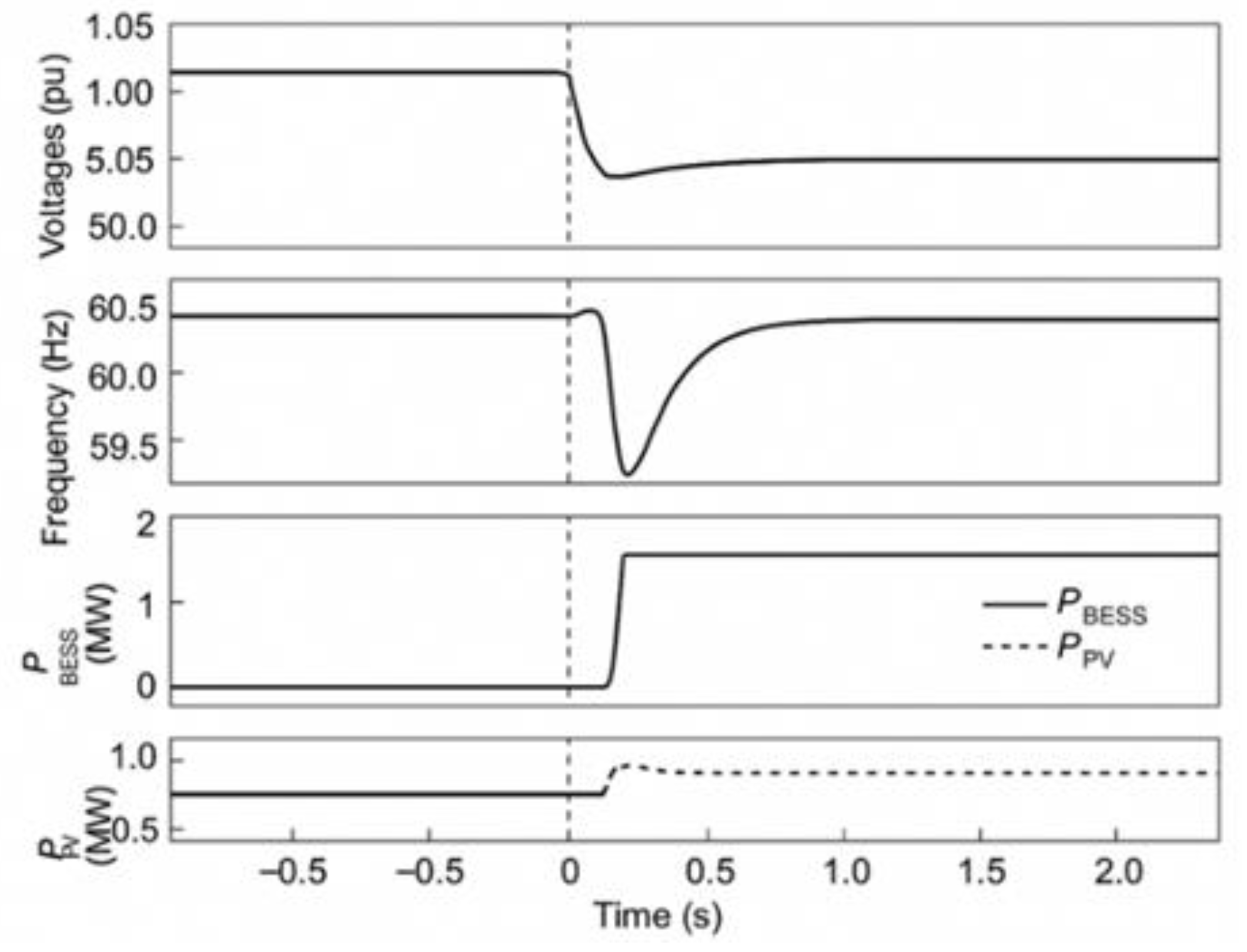

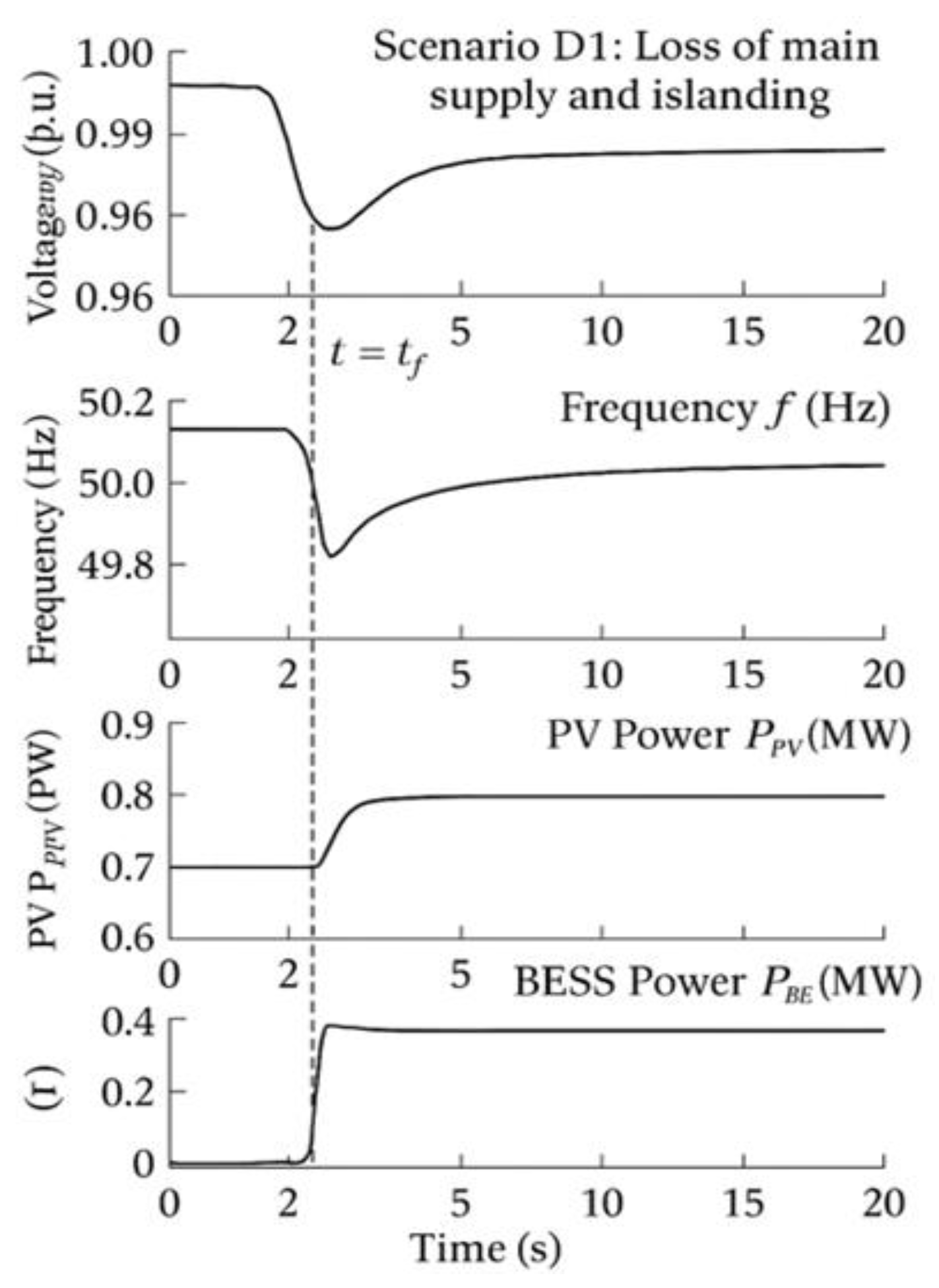

The transient behavior of the microgrid during event D1 is presented in

Figure 4, which illustrates the evolution of nodal voltages, system frequency, as well as the variations in active powers provided by BESS and PV.

The analysis of these graphs highlights the ability of BESS to instantly compensate for the loss of the main source, maintaining the voltage within ±5% and stabilizing the frequency at nominal values in less than 0.5 s.

3.3.2. Scenario D2 – Cyber-Induced Communication Failure

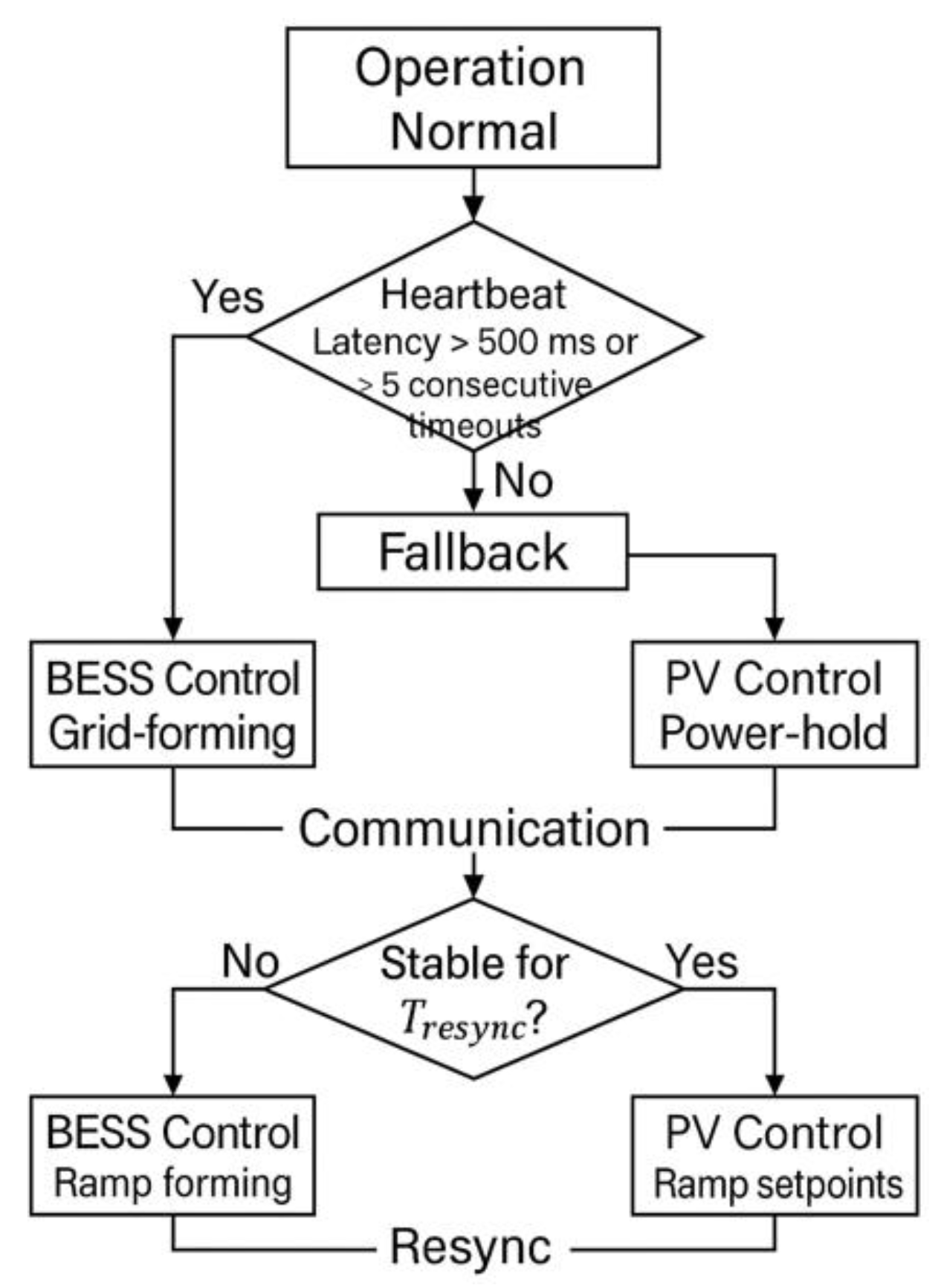

This scenario examines the microgrid’s behavior when a communication failure occurs in the EMS control layer. We assume a cyber disturbance that injects excessive latency, jitter, and packet loss beyond admissible thresholds. These anomalies desynchronize messages between the EMS and local controllers and trigger a fallback mechanism.

The local reaction logic is defined as follows:

if the communication latency exceeds the maximum allowed value ,

or the packet loss exceeds the threshold within a time interval Tobs,

then the local controller switches autonomously to droop control, operating independently of the EMS.

After reestablishing the stable connection for a duration Tresync, the system automatically switches back to synchronized control mode, through a gradual voltage and frequency resynchronization process.

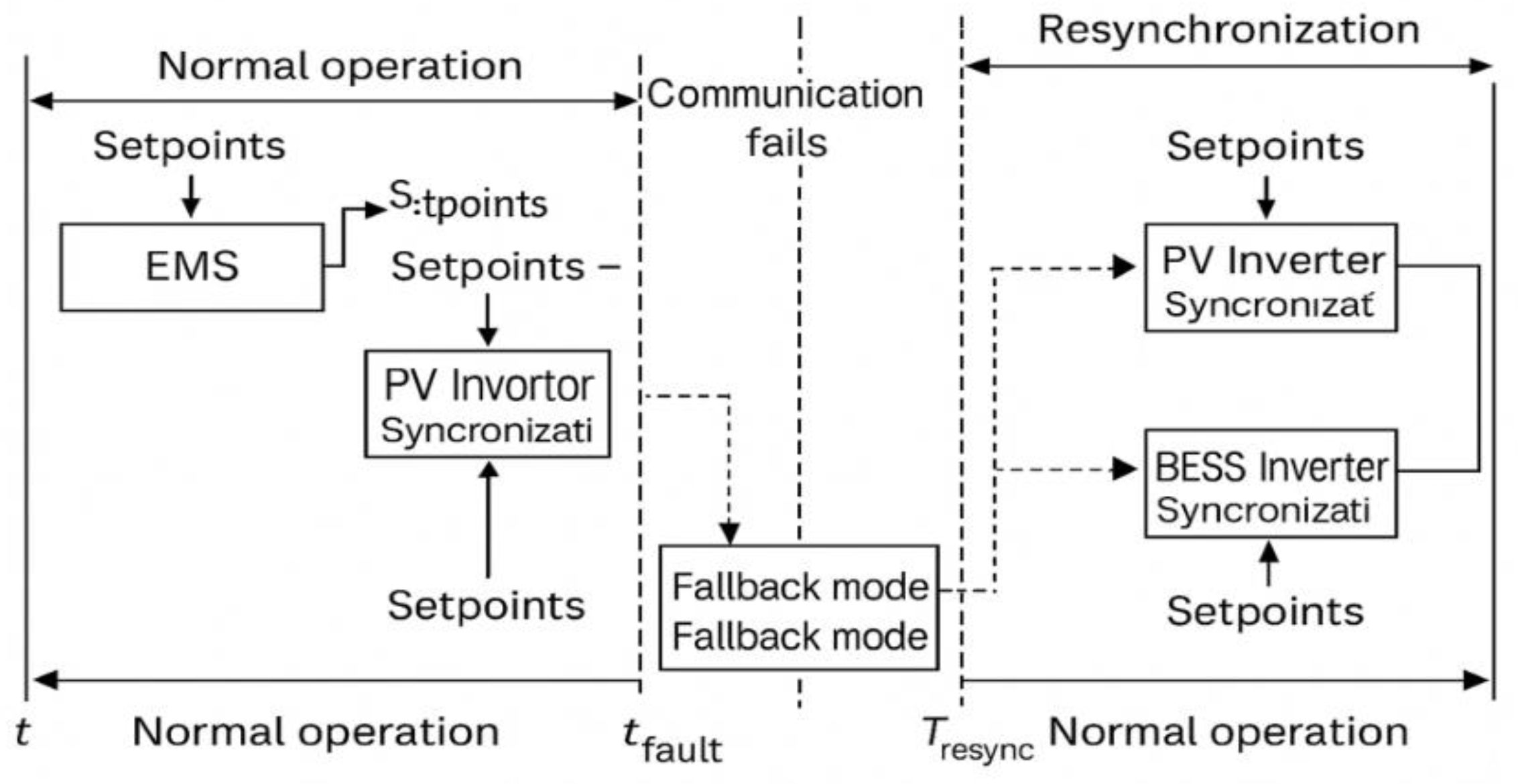

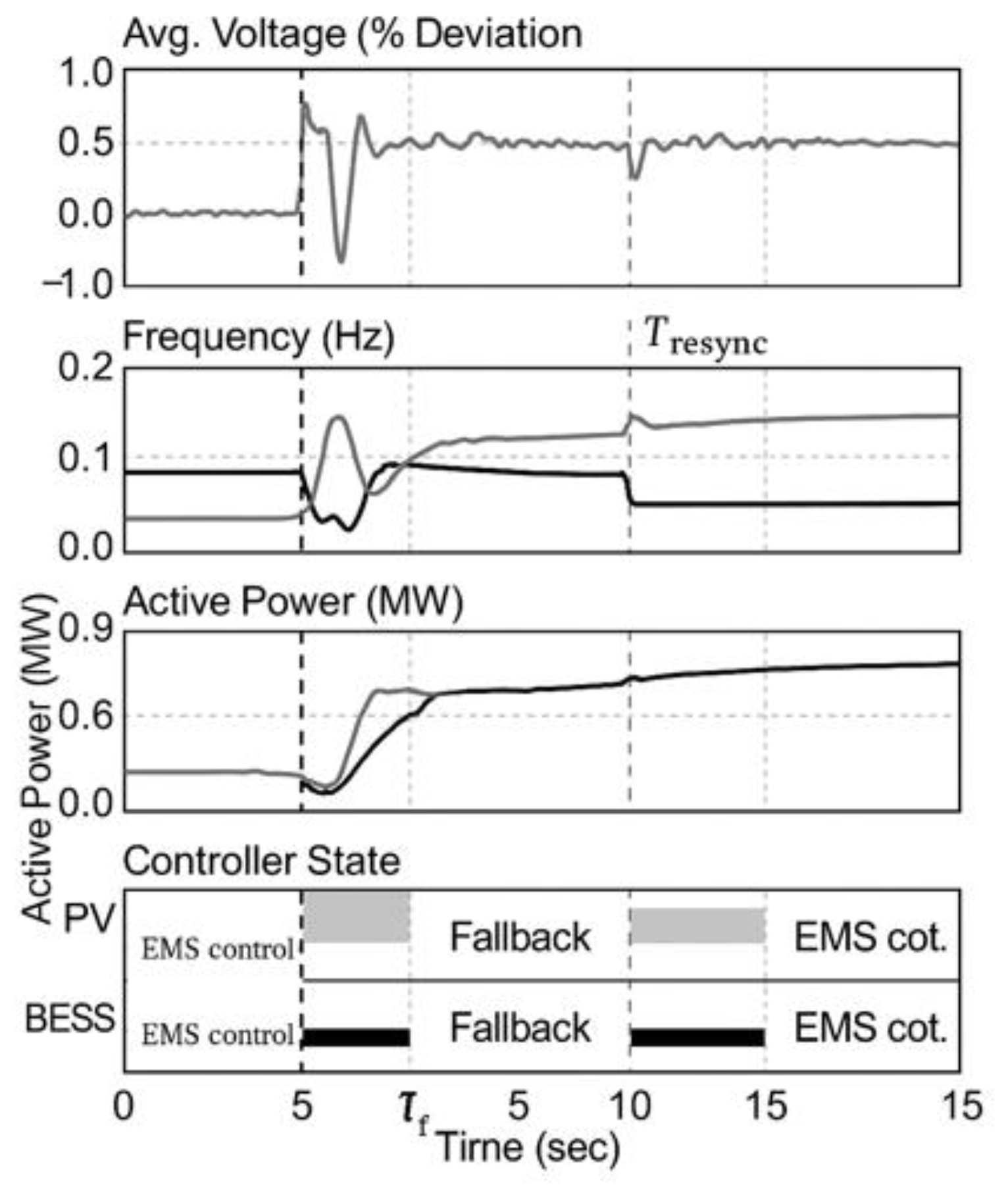

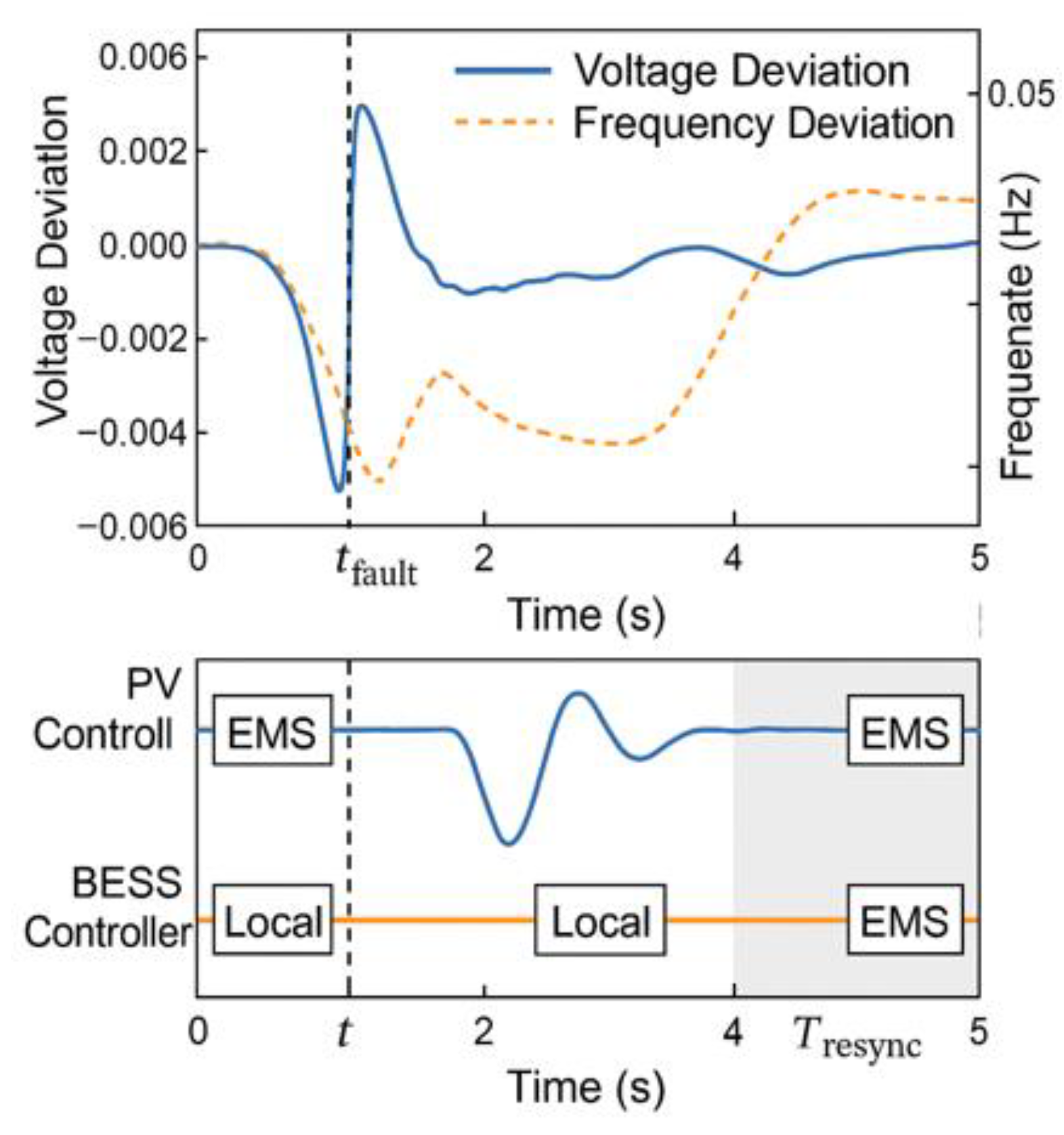

The evolution of the control states during the fault and the return to normal mode are illustrated in

Figure 4, which presents the time diagram of the communication loss and the control mode transitions (EMS → local droop → resynchronized).

This illustrates the dynamic behavior of the microgrid control system during a simulated communication failure between the EMS level and the local controllers of the PV and BESS inverters. In the first phase, the system operates in normal mode, with setpoints periodically transmitted by the EMS and complete data synchronization. At the moment of the cyber disturbance (t = t

fault), communication packets start to be lost and latencies exceed the critical threshold. In response, the controllers automatically switch to fallback mode, activating local droop control to maintain voltage and frequency within acceptable limits. This strategy allows temporary autonomous operation of the microgrid, avoiding instability and loss of synchronism between distributed sources. After communication is reestablished and channel stability is confirmed for a period of time (T

resync), the system gradually returns to centralized EMS control. The results demonstrate that the implemented switching and resynchronization logic gives the microgrid a high cyber resilience capacity, limiting voltage deviations and reducing the operational impact of communication failures.

Figure 5 is showing the timeline of communication loss and transition between control modes in scenario D2 (cyber-induced communication failure). The sequence of phases is highlighted: normal operation with EMS active, loss of communication, activation of local droop control (fallback), and subsequent resynchronization with EMS.

The two scenarios analyzed demonstrate that the proposed microgrid can maintain voltage and frequency stability in the face of physical and cyber disturbances.

The hybrid control strategy (EMS + local droop) allows autonomous operation in isolated mode and controlled recovery after restoring normal conditions, confirming the role of the PV–BESS architecture in increasing the operational resilience of modern electrical systems.

3.4. Performance Indicators

The evaluation of the dynamic behavior of the microgrid in the face of disturbances is based on a set of quantifiable performance indicators, which allow the comparative analysis of the simulated scenarios. In this work, three fundamental metrics are used: VDI, ENS and GRI. These parameters are calculated in the evaluation window [t0,t0+Teval], corresponding to the duration of the event and the recovery period.

3.4.1. Voltage Deviation Index (VDI)

The VDI quantifies the stability of the network in terms of maintaining the nodal voltages around the nominal value. It is defined according to the relationship:

where:

– total number of buses in the system;

– instantaneous voltage at the bus ;

– nominal reference voltage (1 p.u.);

– the duration of the analysis window.

Low VDI values (< 0.05 p.u.) indicate stable behavior and efficient voltage control during disturbances, while high values signal significant deviations and potential risk of unbalance.

3.4.2. The Energy Not Supplied (ENS)

The ENS indicator measures the amount of energy that could not be supplied to consumers during the period affected by the event. It is a key metric for assessing the continuity of power service and the ability of the microgrid to prevent major interruptions (blackouts).

where:

– the power required by the load;

– the actual power delivered by the microgrid to the busbar .

The value ENS=0 indicates full power supply without energy loss, while higher values reflect the severity level of the event and the time required to restore power.

3.4.3. Global Resilience Index (GRI)

To summarize the overall performance of the system, the resilience index R is defined, which reflects the system’s ability to absorb a disturbance and return to its normal state. This index is calculated based on the normalized performance ψ(t), which represents the time evolution of the system’s functional state (e.g. 1 − VDI(t) scaled between 0 and 1):

To summarize overall system performance, we define a resilience index GRI that captures the system’s ability to absorb a disturbance and return to nominal operation. The index is derived from the normalized performance ψ(t), which traces the system’s functional state over time (e.g., ψ(t)=1−VDI(t), scaled to [0,1]):

where:

describes the instantaneous degree of system performance;

corresponds to ideal operation, without losses or deviations;

indicates performance degradation during the event.

Thus, GRI represents an integrated measure of stability and continuity, simultaneously including voltage deviations and energy losses.

Table 4.

Defining indicators and calculation windows.

Table 4.

Defining indicators and calculation windows.

| Indicator |

Symbol |

Evaluation interval |

Unit |

Interpretation |

| Voltage Deviation Index |

VDI |

|

p.u. |

Nodal voltage stability |

| Energy Not Supplied |

ENS |

|

MWh |

Continuity of supply |

| Global Resilience Index |

GRI |

|

– |

Overall recovery capacity |

These indicators will be used in Chapter 4 – Results and Validation, to compare the system performance in the two disturbance scenarios (D1 and D2), highlighting the role of EMS control and fallback logic in increasing the resilience of the microgrid.

By defining and using the VDI, ENS and GRI indicators, a quantitative and rigorous approach to the analysis of the microgrid resilience is ensured. These parameters allow the simultaneous assessment of voltage stability, supply continuity and overall recovery capacity after a disturbance.

In the study, VDI highlights the system response in terms of voltage deviations, ENS quantifies the energy lost during the event, and GRI integrates these effects into a single normalized performance metric.

Thus, the analysis based on these indicators provides a complete perspective on the dynamic behavior of the microgrid, facilitating the identification of vulnerable points and control improvement strategies. In the next chapter, the values obtained for the two scenarios (D1 – loss of main power supply, D2 – loss of communication) will allow for a direct comparison of the level of resilience and stability of the proposed system.

3.5. Simulation Setup

The modeling and simulation of the proposed microgrid were performed using the MATLAB/Simulink platform, with the dedicated Simscape Electrical package, which allows for a precise physical description of the electrotechnical components and control strategies. The simulation architecture was designed to faithfully reproduce the behavior of the IEEE 33-bus system equipped with distributed sources (PV at bus 6 and BESS at bus 18), under the action of the D1 and D2 disturbance scenarios.

3.5.1. Simulation Environment

The simulations were run in a discretized environment with a 100 µs time step to capture fast electromagnetic phenomena associated with inverters and load switching. The raw outputs were then aggregated to a 10 ms resolution, appropriate for power-system dynamics (frequency, voltage, and power flows).

For daily performance assessment, we used 1-minute irradiance and load profiles for a representative summer day, implemented as normalized inputs scaled to the sources’ nominal ratings.

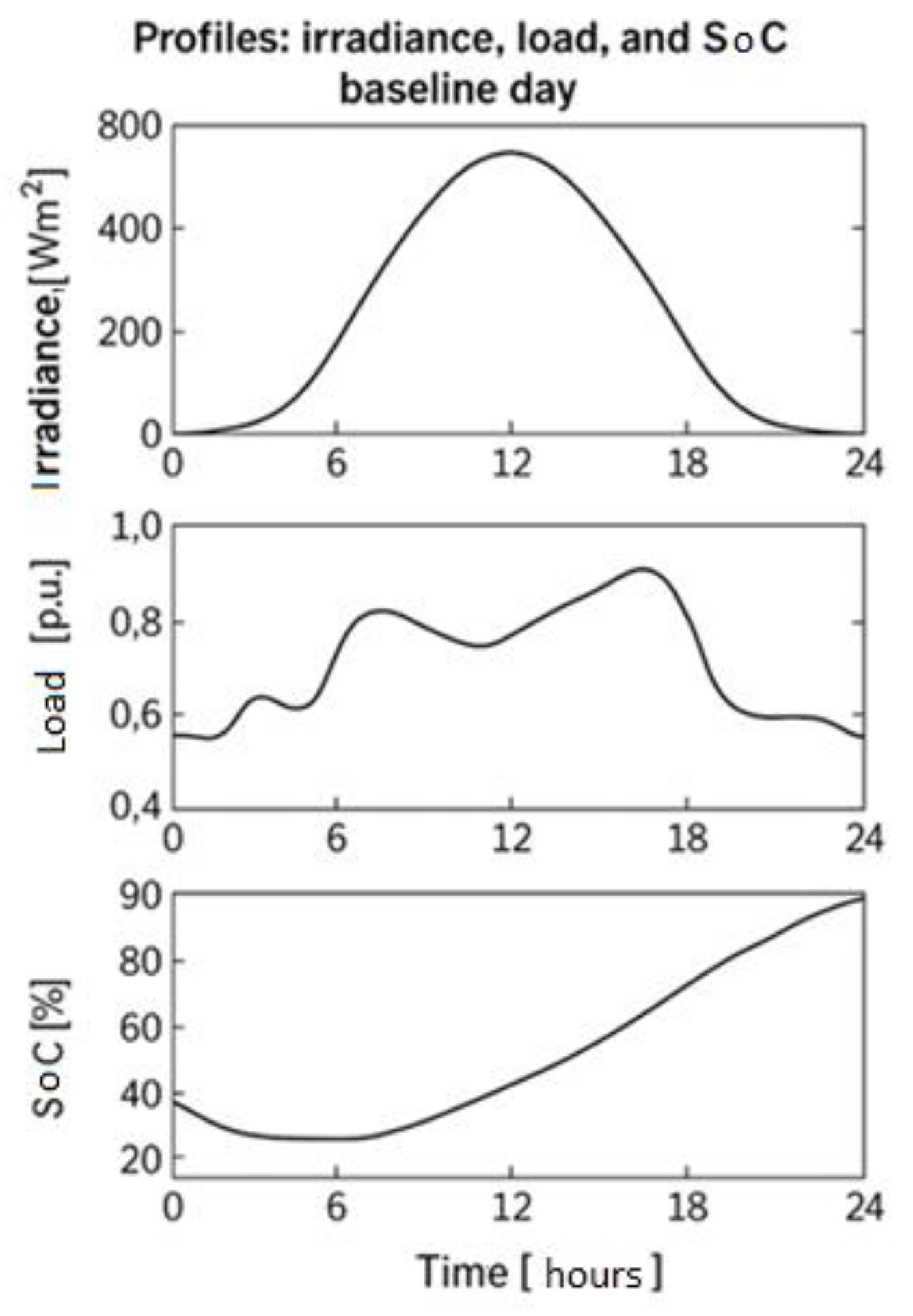

Figure 6 shows the evolution of these profiles—the solar irradiance, the microgrid’s aggregate load, and the battery SoC—for the reference day.

Figure 6 shows the resilts of the daily profiles of solar irradiance, total load and SoC of the BESS system on a typical summer day.

These profiles define the microgrid’s baseline operating regime and serve as the basis for evaluating system behavior under disturbance scenarios D1 and D2. As illustrated in

Figure 6, irradiance peaks around 12:00–13:00, the total load exhibits a bimodal pattern (morning and evening peaks), and the SoC during peak solar production and discharges overnight to cover residual demand.

3.5.2. Main Technical Parameters

The microgrid model used in the simulation is based on the IEEE 33-bus distribution feeder standard, a reference configuration for studying the stability and resilience of distribution networks.

The network consists of 33 buses and 32 interconnection lines, arranged in a radial topology, characteristic of real medium voltage distribution systems (12.66 kV).

The main power source is represented by an interface transformer with a nominal power of 5 MVA, which connects the microgrid to the main transmission system through bus 1 (PCC). This serves as a reference point for voltage and frequency synchronization in normal operation.

Within this network, two DERs with complementary roles have been integrated, designed to increase the stability and autonomy of the microgrid:

The PV source is connected to bus 6 and has a nominal power of 0.9 MVA (equivalent to approximately 1.0 MWp DC). It is equipped with a grid-following inverter, which follows the voltage and frequency of the main system, adjusting the active power injection according to irradiance and temperature, and compensating the reactive power through a Volt/Var droop law.

The BESS is located at bus 18, with a capacity of 1.6 MWh and a nominal power of 0.8 MVA. The associated inverter operates predominantly in grid-forming mode, generating its own voltage and frequency reference when the microgrid is islanded. In normal mode (connected to the main system), it operates in grid-following mode, maintaining the balance of active and reactive power according to EMS commands.

Both converters are three-phase bidirectional, allowing both the delivery and absorption of electrical energy, depending on the state of the grid and the operating conditions. They can operate in synchronized (interconnected) or isolated (islanded) mode, depending on the events detected at the PCC and the state of the communication channel.

The coordination between the photovoltaic inverter and the BESS system is ensured by an EMS, which transmits reference commands (setpoints) for active and reactive power, based on data collected from the grid. In the event of a communication failure, both converters automatically switch to fallback mode, activating local droop control, to maintain voltage and frequency stability in autonomous mode.

By configuring these components, the proposed model faithfully reproduces the behavior of a modern distribution microgrid, capable of coping with power losses, load fluctuations and cyber incidents, thus demonstrating the practical relevance of the simulated architecture.

3.5.3. Local Control and EMS Settings

To manage power flows and maintain stability under variable operating conditions, the proposed model implements a hierarchical control architecture consisting of two levels:

(1) Local control of the inverters (primary and secondary levels), and

(2) EMS responsible for the global coordination of resources.

Local Control – Primary Level

Both static converters (PV and BESS) are equipped with local droop controllers, which define the relationship between frequency/voltage variations and active/reactive power injections.

These control laws mimic the inertial behavior of synchronous machines, allowing automatic power distribution between sources without constant communication between them.

PV inverter, that operates in grid-following mode, uses droop slopes of 5% for frequency (P–f) and 3% for voltage (Q–V). These values were chosen so that the inverter can contribute to reactive regulation according to load variations, while limiting power circulations between nearby nodes. In addition, the inverter has an output LC filter sized to ensure a Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) below 3%.

BESS operates in grid-forming mode, generating the voltage and frequency references for the entire microgrid in islanded mode. For it, droop slopes of 4% for frequency and 2% for voltage were adopted, values that ensure stable dynamics and a balanced load sharing between BESS and PV. The battery is protected by a peak current limiting control and a second-order filter to smooth out rapid load variations.

For both converters, the response time of the internal loops (current and voltage) was configured below 5 ms, allowing a fast reaction to disturbances without significant voltage or current overshoots.

EMS Control – Secondary Level

The top level of the hierarchy is represented by the EMS, which continuously monitors the state of the microgrid and transmits active and reactive power setpoints to the inverters at an interval of 200 ms.

These commands are calculated based on the local energy balance, the available power from renewable sources and the BESS system SoC.

EMS manages the following main functions:

Energy balancing between generation, storage and consumption;

Maintaining the reference voltage and frequency within normalized limits (±1% and ±0.1 Hz);

Optimal allocation of reactive power to reduce grid losses;

Managing transitions between interconnected and islanded regimes;

Detection of loss of communication and activation of local autonomous control (fallback).

Fallback and synchronization logic.

In case of loss of the communication channel between EMS and inverters (scenario D2), the system automatically switches to fallback mode, in which each converter maintains its current settings and activates local droop-based control.

This strategy ensures the continuity of supply and the stability of the microgrid even in the absence of central coordination. After the communication is restored, EMS checks the stability for a resynchronization period Tresync and gradually restores centralized control.

BESS System Parameters

The battery storage system is configured with an operational SoC range between 20% and 90%, and the overall charge–discharge efficiency is considered to be 96%. The control includes automatic protections for over discharge, overcharge, and high cell temperatures, all managed by algorithms integrated into the EMS.

By combining these control levels, the microgrid achieves a balance between stability, flexibility, and operational resilience, being able to react autonomously to electrical or cyber disturbances, without losing synchronism or compromising power quality.

3.5.4. Input Data and Files

All network parameters and component characteristics were automatically imported from CSV files T1a–T1d, which contain:

Distribution line lengths and impedances;

Interface transformer parameters;

PV source characteristics (I–V curve, inverter efficiency, power factor);

Storage system parameters (capacity, power, efficiency, SoC limits).

For a coherent management of simulation data, all values associated with the system components were stored in *.CSV files, corresponding to the structure described in

Table 3.

These files are automatically imported into the MATLAB/Simulink environment by means of a dedicated script, which ensures the consistency and reproducibility of the results. The aggregated nominal values for the main network elements are presented in

Table 5.

3.5.5. Initial Conditions and Simulated Scenarios

The simulations were initialized in a steady state, corresponding to the normal operation of the IEEE 33-bus microgrid, connected to the main power system through bus 1 (PCC). All initial voltages and currents were calculated through a balanced three-phase power flow solution, ensuring the nominal conditions of 12.66 kV and frequency of 50 Hz.

The battery SoC was initially set to 70%, a value that allows both absorption and delivery of active energy depending on the system requirements. At the same time, the PV generator was configured to operate in grid-following mode, delivering active power proportional to the instantaneous solar irradiance and regulating the reactive component through a Volt/Var droop law. The BESS, configured in grid-forming mode, ensured local frequency and voltage regulation in the event of islanding.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed control strategy and the EMS–BESS–PV architecture, two distinct disturbance scenarios were defined, relevant to the operational behavior of a real microgrid:

At time t=tf, the interface line between bus 1 and bus 2 is interrupted, simulating a sudden disconnection from the main system (external grid fault). The microgrid automatically switches to islanding mode, and the BESS inverter switches to grid-forming mode, taking over the frequency and voltage reference for the rest of the system. The evolution of voltage, active/reactive power and frequency stability is monitored during the transition.

- 2.

Scenario D2 – Cyber-induced communication failure

At a predetermined time, the communication channel between the EMS and the inverter controllers is affected by introducing a degradation pattern: packet loss (packet loss 25%) and increased latency (over 300 ms). After exceeding the defined thresholds, the local controllers automatically switch to fallback mode, activating autonomous droop control. After a period of time Tresync, the system returns to the centralized regime, and synchronization is restored without significant phase imbalances.

For each scenario, the simulations were run three times independently, with minor variations in the load and irradiance profile (±5%), to assess the robustness of the solution and the statistical stability of the indicators. The results were statistically aggregated, and

Table 6 in the following chapter presents the mean values and standard deviations of the VDI, ENS and GRI indicators for both analyzed cases.

This final simulation stage provides the basis for comparison between the normal, disrupted and restored scenarios, demonstrating the ability of the proposed system to maintain stability and continuity of supply even under conditions of loss of main supply or cyber-attacks.

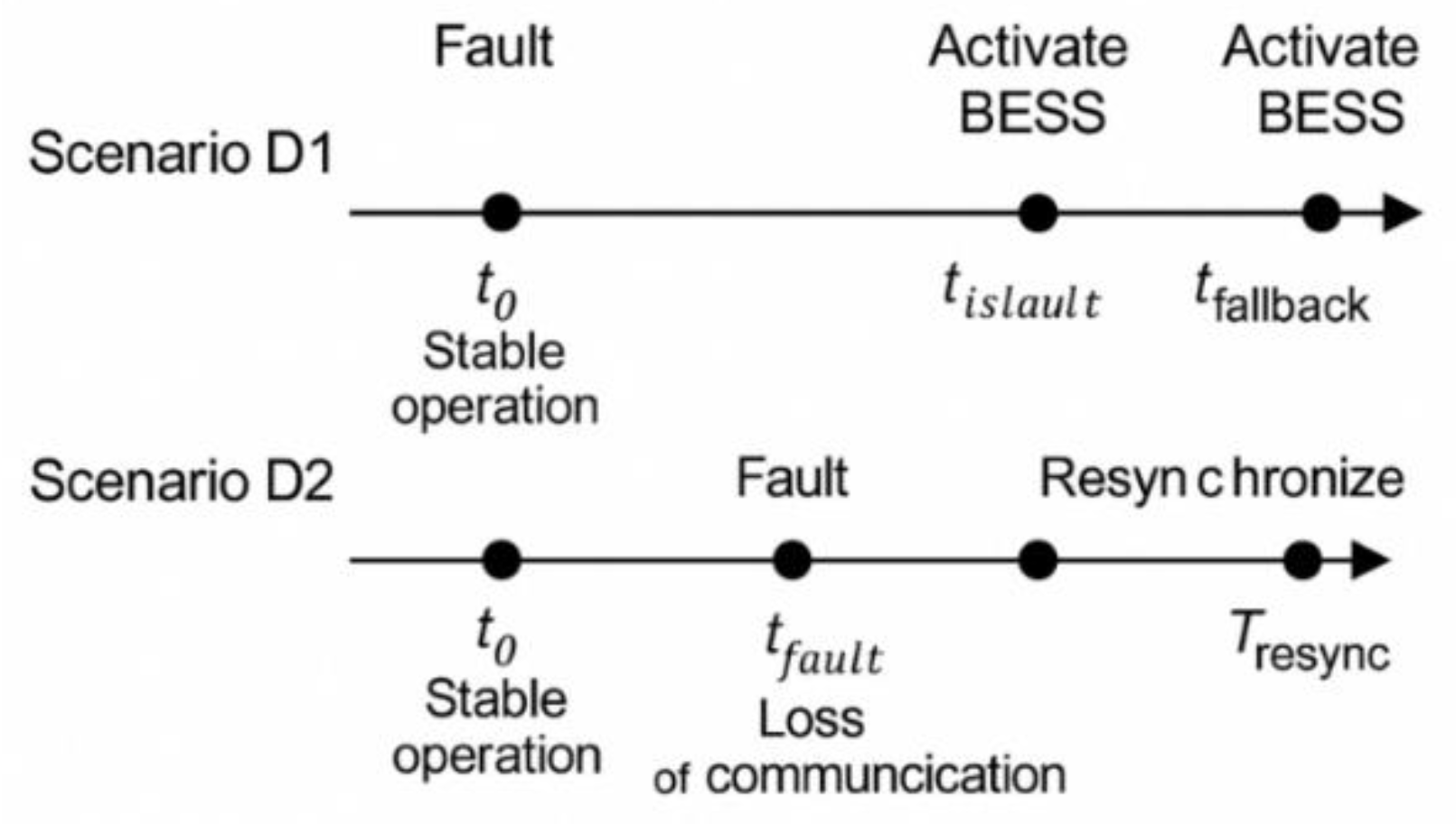

For greater clarity on the dynamics of the simulated events,

Figure 7 presents the chronology of scenarios D1 and D2, along with the main transition moments. It is observed that, in the case of D1, the disconnection from the main grid (t

f) determines the rapid switching of the microgrid to island mode, coordinated by the BESS inverter in grid-forming mode. In contrast, scenario D2 focuses on the loss of communication between the EMS and the local controllers, at which point the droop control-based fallback logic is activated, ensuring that stability is maintained until the communication channel is re-established and resynchronization (T

resync) is achieved.

Timeline of simulation scenarios D1 (main power loss) and D2 (communication failure), illustrating key moments: t₀ – normal mode, t

f – occurrence of disturbance, t

island -transition to island mode (BESS grid-forming), t

fallback – activation of local control, and T

resync -resynchronization with EMS are presented in

Figure 7.

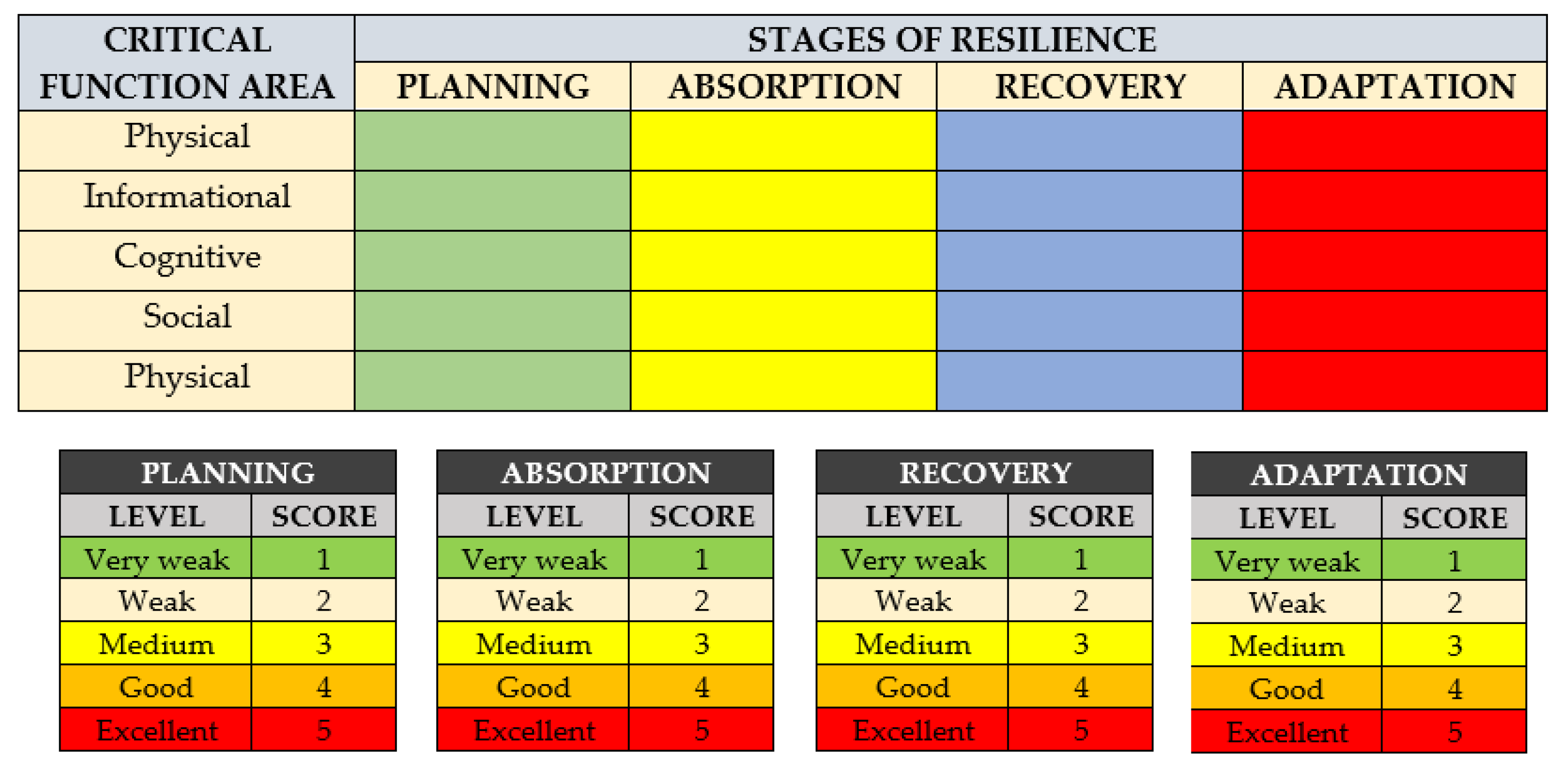

3.6. Qualitative Assessment of Energy Resilience – “Resilience Matrix” Method

In addition to the quantitative assessment through VDI, ENS and R, we propose a qualitative-structured assessment of the microgrid based on the Resilience Matrix.

This method provides a holistic view of the system’s capacity to plan, absorb, recover and adapt to disturbances, on four levels of the system: physical/technological, informational, cognitive/decisional and social/organizational.

Figure 8 presents the general model of the matrix (4×4) and the 5-level rating scale (1 – very poor … 5 – excellent).

Table 6 summarizes the scores obtained for the analyzed microgrid domains (PV+BESS Generation, Distribution, Control/SCADA, Communications, Demand Response/DR) and the Global Resilience Index (GRI).

3.6.1. Matrix Structure and Evaluation Scale

Horizontal axis – Resilience stages: Planning/Prevention (Plan), Absorption (Absorb), Recovery (Recover), Adaptation (Adapt).

Vertical axis – System levels: Physical/Technological, Informational, Cognitive/Decisional, Social/Organizational.

Each cell level ,, stage ) receives an ordinal score based on a common rubric:

1–2: low capacity, no redundancy / high times / critical dependency;

3: moderate capacity, partial functionality under stress;

4–5: robust, high redundancy and adaptability, short times, validated procedures.

The complete Resilience Matrix model is illustrated in

Figure 8., where the critical function domains, resilience stages, evaluation scale, and hypothetical scores used in the calculation of the global IGR index are represented.

3.6.2. Link to Quantitative Indicators (Metric → Score Mapping)

The scores in the matrix are informed by the quantitative results obtained in scenarios D1 (power loss) and D2 (communication loss). We use a two-step mapping:

(i) Metric normalization (performance 0–1):

where:

Thresholds are set from literature/standard (IEEE 1547) or from our baselines.

(ii) Conversion performance → ordinal score (5 equal bands):

Recommended mappings on key cells:

Physical–Absorption ← VDI in the transient range (amplitude and duration);

Physical–Recovery ← ENS and time to return to tolerances (V/f);

Informational–Absorption/Recovery ← packet loss/delay, fallback/resync;

Cognitive/Adaptation ← improvement Between rounds (lessons learned, droop/EMS retuning);

Social/Planning ← procedures/DR, exercises, operating manuals, staff training.

After populating the cells, for each domain

j (e.g.: Generation, Distribution, Control/SCADA, Communications, DR) the resilience score is calculated as the average of the four stages:

3.6.3. Aggregation by Domains and the Global IGR Index (with Weights)

The global index is obtained as the (possibly weighted) average of the scores by domains:

If no explicit priority is justified, equal weights wj=1, are used.

Methodological note: The scores in

Figure 8 were established by expert judgment based on the results of D1/D2 (VDI, ENS, R), IEEE 33-bus data and operating practices (SCADA/OT). In case of divergence between evaluators, the arithmetic mean was used and the uncertainty is reported as ±0.5 levels on a scale of 1–5.

3.6.4. Results for the IEEE 33-bus Microgrid (hypothetical Scores)

Based on the conceptual model presented in

Figure 8, hypothetical scores were assigned for the five main domains of the microgrid: generation (PV + BESS), distribution, control/SCADA, communications and demand response.

The values in

Figure 8 reflect the average level of planning, absorption, recovery and adaptation capacity, according to the scale of 1–5 defined previously.

The GRI was determined by the arithmetic mean of the scores by domain, according to the relationship:

where R

i represents the resilience score for domain

i, and

n is the total number of domains analyzed.

The result obtained, GRI = 2.90, indicates a moderate level of resilience, corresponding to a microgrid capable of maintaining essential operation in island mode and resynchronizing without significant losses.

Table 6 shows the hypothetical resilience scores for the main domains of the IEEE 33-bus microgrid and calculation of the GRI.

GRI calculation (unweighted):

The detailed analysis of these results and the interpretation of the determinants for the level of resilience obtained are presented in the following subsection.

3.6.5. Interpretation of the Results Regarding the Resilience of the IEEE 33-Bus Microgrid

The results summarized in

Table 6. indicate a GRI = 2.90, which corresponds to a moderate resilience on the evaluation scale (2.5–3.5). This level suggests that the analyzed microgrid is able to maintain its essential functions under stress conditions, but presents significant vulnerabilities in the absorption and recovery stages after major disruptive events.

Analyzing the individual resilience domains, the main strengths and weaknesses can be identified:

Generation (solar + batteries)

The score of 3.25 indicates a relatively robust generation system, with good planning and adaptation capacity.

The presence of a storage system (BESS) contributes to the absorption of power variations and the continuity of supply in island mode. However, the recovery component (score 2) highlights a dependence on battery recharge times and local energy management.

Recommendation: implementing predictive energy management strategies and expanding storage capacity would increase the overall score above 3.5.

Distribution (local network)

With a score of 2.50, the distribution domain presents limited resilience, specific to infrastructures with a radial topology (such as the IEEE 33-bus network).

Low levels of absorption and recovery (score 2) indicate vulnerability to line faults and local voltage losses.

Recommendation: integrating automatic reconfiguration schemes (auto-reclosers, sectionalizers) and distributed monitoring sensors for rapid incident detection could increase distribution resilience to above 3.0.

Control / SCADA

The score of 2.25 is the lowest of the areas assessed and highlights the dependence on centralized control infrastructure. The lack of redundancy and failover mechanisms reduces the system’s ability to absorb operational shocks.

Recommendation: The introduction of distributed control units (edge controllers) and logical segmentation of the SCADA network can reduce the Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR) and improve information resilience.

Communications

The communications domain has a score of 2.75, reflecting moderate but stable performance.

The adaptability and recovery capacity (3) suggests the existence of a functional communication infrastructure, but limited by the low redundancy and latencies of conventional networks.

Recommendation: Adopting a multipath model (fiber + radio + cellular), with AES encryption and real-time latency monitoring, would increase the absorption and adaptation capacity to over 3.5.

Demand Response (DR)

The highest score (3.75) confirms the critical role of consumer flexibility in stabilizing the microgrid.

DR programs ensure a dynamic balance between demand and supply, reducing stress on the generation and distribution infrastructure.

Expanding DR participation through targeted economic incentives (e.g., tiered rebates, time-of-use bonuses, pay-for-performance) and integrating AI to predict consumer behavior (for smarter enrollment, dispatch, and personalization) would increase load flexibility, improve peak shaving and ramping control, and reduce outage risk. Implemented at scale, it can lift this domain’s resilience to an excellent level (≥ 4.5). Overall, the analyzed microgrid presents a balanced resilience profile, with good planning (average score 3.2) and satisfactory adaptation capacity (3.2), but low absorption (2.6) and recovery (2.4) performances.

These results indicate a functional infrastructure, but with potential for improvement through digitalization, automation and redundancy.

On a scale of 1–5, the IGR value = 2.90 confirms the moderate level of resilience of the microgrid, consistent with the quantitative results obtained in the dynamic scenarios:

In scenario D1, the reduction of the VDI indices (~27%) and ENS (~12%) compared to the base case validates the lower scores in the Physical–Absorption and Physical–Recovery domains (level 2–3).

In scenario D2, maintaining the V/f deviations within narrow limits and increasing the R index by ~0.07 justify the better performances on the Informational/Cognitive–Adaptation dimension (level 3–4).

Lower scores in the Control/SCADA and Communications domains confirm the dependence on EMS and the need to introduce additional redundancies, including through OT segregation, multipath channels and periodically tested failover mechanisms.

This correlation between quantitative indicators and matrix scores demonstrates the methodological coherence of the assessment and validates the applicability of the “Resilience Matrix” method in the analysis of distributed energy systems.

The moderate level of the GRI = 2.90) reflects a maturing system, capable of ensuring continuity of supply in an islanded manner and partially responding to disruptive events.

By implementing the identified technical recommendations (automation, SCADA redundancy, storage expansion and communications digitalization), the microgrid can achieve a “good” level of resilience (GRI ≈ 3.5–3.8), approaching the performance of fully integrated smart grids.

3.6.6. Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

To validate the robustness of the assessment, a sensitivity analysis was performed on the scores in the matrix.

Two scenarios were considered:

Differential weighting – the critical areas Control/SCADA and Communications were multiplied by factors wSCADA= wcomms =1.5, reflecting their importance in maintaining operational stability.

Score variation ±1 level for cells with high uncertainty (incomplete data or expert estimates).

The results show that:

the variation of the weights modifies the GRI by ± 0.10 – 0.15, without changing the overall classification (“moderate resilience”);

the variation of the scores by ±1 level on the uncertain cells determines a maximum change of ±0.15 in the overall value of the index.

We thus confirmed the stability of the method and the consistency of the conclusions obtained in

Section 3.6.5.

Increasing the BESS storage capacity or optimizing the droop parameters (see Sec. 4.4) determines an estimated improvement of the RGeneration score and the GRI by ≈0.1–0.2, which would raise the system to the “good resilience” threshold.

3.6.7. Specific Recommendations

Based on the results summarized in

Table 6. and the resilience scores (

R), the following priority improvement measures can be formulated:

Control/SCADA (R = 2.25): introducing redundancy at the PLC/RTU level, segmenting the Operational Technology (OT) network, periodic failover exercises and automating restoration procedures;

Distribution (GRI = 2.50): implementing automatic reconfiguration schemes (reclosers, sectionalizers), critical parts stocks and SLA (Service Level Agreement) contracts with local intervention teams;

Communications (GRI = 2.75): ensuring multipath redundancy (fiber, radio, cellular), data encryption and anomaly monitoring, with dynamic thresholds for fallback/resync;

Generation (GRI = 3.25): increasing BESS capacity, simulating virtual inertia and defining EMS policies for selective load-shedding;

DR (GRI = 3.75): expanding active consumer participation programs, quarterly testing scenarios and integrating DR mechanisms into black-start and islanding procedures.

The methodology developed in this paper proposes a unified framework for analyzing the resilience of distributed microgrids, by combining quantitative indicators (VDI, ENS, GRI) with qualitative assessment based on the Resilience Matrix. This approach allows for multidimensional characterization of the system, covering the physical, informational, cognitive and organizational levels, and captures the interaction between control, communications and renewable sources under operational stress conditions.

The sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the proposed method, with the variation of the GRI remaining below ±0.15 for the uncertainty intervals considered. The results obtained highlight the importance of redundancy of control and communication infrastructures, optimization of regulation parameters (droop control) and increasing BESS to improve the overall performance of the microgrid.

The proposed methodological framework is scalable and reproducible, providing a solid basis for assessing the operational resilience of smart microgrids in the face of communication losses, control degradation and variability of renewable sources.

The values presented in section 3.6 are hypothetical, being used exclusively to illustrate the proposed method and the way to interpret resilience indicators.

The practical application of the methodology, based on simulated data for the IEEE 33-bus microgrid, is presented in

Section 4 - Results and Validation, where scenarios D1 and D2 are analyzed and the impact of photovoltaic penetration, BESS and regulation parameters (droop control) on the resilience performance of the system is evaluated.

4. Results and Validation

In this section, the methodology described in Chapter 3 is applied to analyze the dynamic behavior of the IEEE 33-bus microgrid. The goal is to evaluate the system performance under disturbance conditions, by comparing two distinct scenarios:

D1: loss of main supply and transition to islanding;

D2: loss of communication between EMS and local inverters, followed by activation of autonomous control mode (fallback).

The results are organized progressively — from the analysis of the steady state and power flows, to the transient behavior, frequency stability and sensitivity to control parameters and penetration of distributed sources.

4.1. Steady State (Grid-Connected)

In normal operation, the microgrid is synchronized with the main distribution system through bus 1 (PCC). In this state, the grid-following control of the PV inverter and the grid-support control of the BESS system allow a balanced supply of all loads, maintaining the voltages within nominal limits.

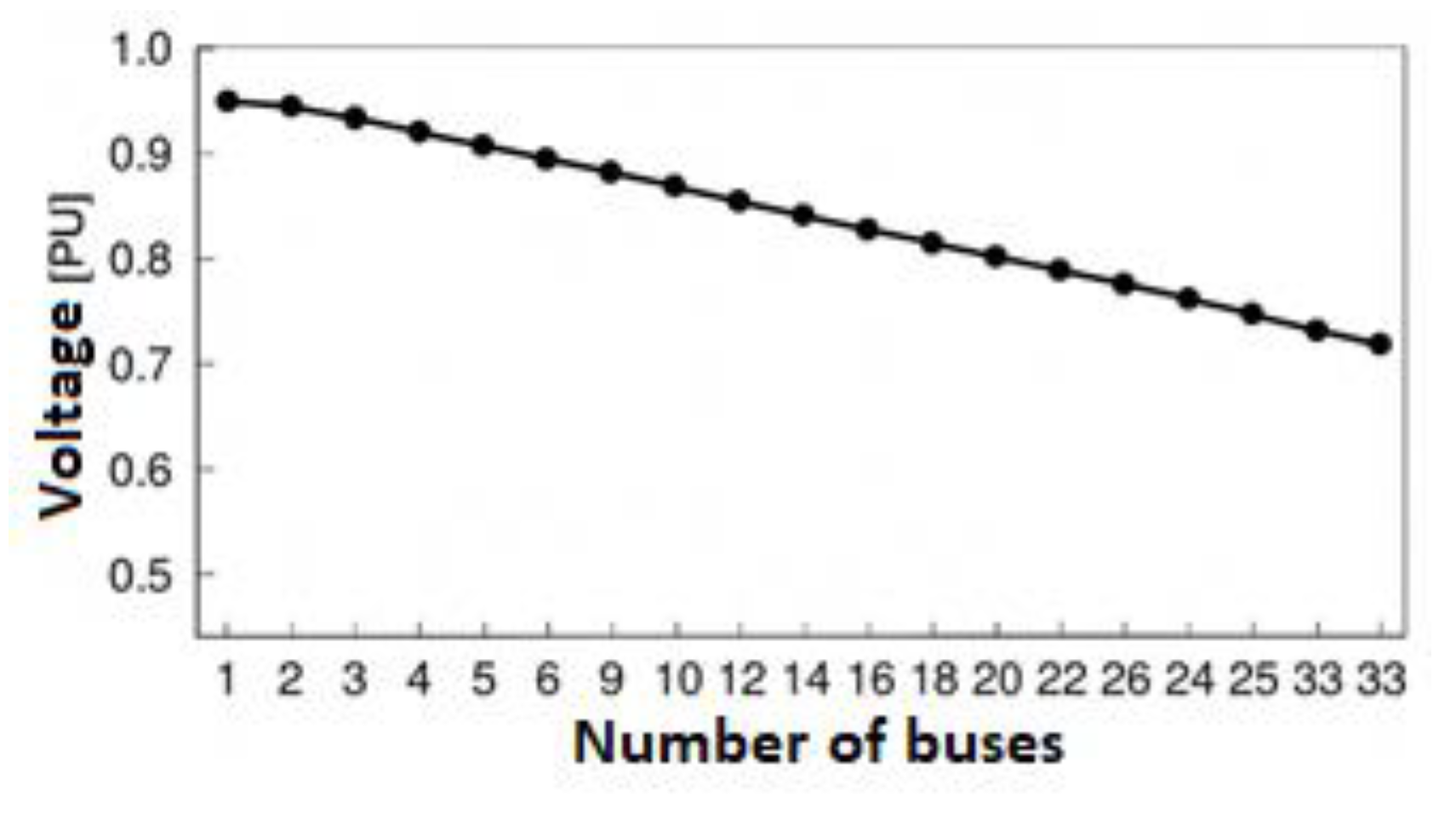

Voltage distribution

The nodal voltages in the steady state range between 0.964 p.u. and 1.000 p.u., which complies with the limits recommended by IEEE Std. 1547 for microgrids connected to the main system (±5% of the nominal value).

The lowest voltage value is recorded at bus 33, located at the radial end, where the voltage drop is determined by the cumulative impedance of the feeder.

The inclusion of the PV source at bus 6 contributes to reducing voltage losses on the upper segments, due to the injection of local active power.

Power flows

The total power supplied by the main transformer is approximately 3.715 MW + j2.300 Mvar, covering the consumption of the 33 buses.

The PV inverter injects an average active power of 0.85 MW at a unity power factor, while the BESS system operates in standby mode, maintaining an SoC ≈ 70%, ready for dynamic adjustments in case of disturbance.

Reactive power flows are stabilized by the Volt/Var law implemented in the PV inverter, which supplies positive reactive power (inductive) in undervoltage areas and absorbs reactive power in overvoltage, keeping the voltage almost constant around 1 p.u.

Feeder losses

Total active power losses in the lines, calculated according to the expression:

are approximately 0.135 MW, representing 3.6% of the total transmitted power, a value considered acceptable for medium voltage distribution networks.

Due to the integration of the PV source, losses are reduced by about 18% compared to the case of the network without local generation, confirming the technological benefit of decentralized distribution.

The summary of the main parameters obtained in stationary mode is presented in

Table 7, which summarizes the average values of voltages, power losses and load level of the BESS system.

These results confirm that the microgrid maintains a state of energy balance and a uniform distribution of voltages, without exceeding the limits imposed by IEEE standards. The values obtained will serve as a comparative reference for the analysis of the system behavior in the D1 and D2 disturbance scenarios presented in the following sections.

Table 7 consists of main parameters of the steady state (IEEE 33-bus microgrid with PV connected to bus 6 and BESS connected to bus 18.)

Figure 9 shows the nodal voltage profile for the steady state, taking 1.0 p.u. at bus 1 as a reference. A gradual decrease in voltage towards the radial end is observed, with the minimum at bus 33 (~0.964 p.u.). The integration of the PV source at bus 6 contributes to the voltage support on the upstream segments, reducing the slope of the drop in the first half of the feeder. This behavior confirms the beneficial effect of local generation on the voltage profile and constitutes the reference basis for the dynamic scenarios analyzed later (D1 and D2).

The values in

Table 7 were obtained by solving the load flow for the IEEE 33-bus model implemented in MATLAB/Simulink (Simscape Electrical).

The nodal voltages Vmax and Vmin result from the stationary solution of the network at the nominal voltage of 12.66 kV, according to the IEEE standard dataset.

The active power injected by the PV source PPV was calculated for an irradiance of 950 W/m², corresponding to an operating level of 95% of the nominal power.

The active losses (Ploss) were determined based on the relationship ,, resulting in a value of approximately 3.6% of the total load.

The average battery SoC (SoCavg) was set to 70%, a value that allows the balance between the possibility of discharging and recharging in subsequent dynamic scenarios.

All these values are consistent with the results published in the IEEE 33-bus benchmarks [

70,

73,

74]. The steady-state results confirm the good configuration of the model and the correct calibration of the components. The system respects the voltage limits, presents moderate losses and has a stable energy balance between generation, storage and consumption. This regime will be used as a reference base (baseline) for comparing the performances in the disturbance scenarios D1 and D2.

The steady-state regime highlights the equilibrium of the system and the validity of the adopted configuration for the subsequent dynamic scenarios. This operating point is used as the initial state (t₀) in all the transient simulations in chapter 4.

4.2. Scenario D1 – Loss of Main Power Supply and Transition to Islanding

To assess the resilience of the microgrid under severe disturbance conditions, scenario D1 was simulated, which represents a sudden loss of main power supply by opening line 1–2 at time .

The event triggers the automatic separation from the medium voltage grid and the transition of the microgrid to islanding mode, under the leadership of the BESS inverter in grid-forming mode. At this stage, the PV inverter switches to grid-following mode, synchronizing with the reference frequency and voltage set locally by the BESS.

4.2.1. Transient Evolutions of Voltage, Frequency and Active Powers

Figure 10 presents the time variations of the nodal average voltages

, frequency

(f(t)), active powers injected by the photovoltaic source

and the storage system

Immediately after the loss of connection to the main system, the voltage and frequency register a rapid decrease of about 3.8% and 0.4 Hz, respectively, determined by the temporary imbalance between load and generation. Subsequently, the droop control of the BESS inverter restores the frequency to 49.9 Hz in about 0.3 s, and the PV source contributes to the voltage regulation, limiting the deviations below ±2.5%.

The BESS inverter reacts in the range of 150–200 ms, providing an increase in active power of +0.35 MW, which quickly stabilizes the frequency at 49.9 Hz.

The photovoltaic source contributes through Volt/Var regulation to the restoration of the voltage profile in the area of bars 6–10, reducing the maximum deviations below ±2.5% after the first 3 seconds of islanding.

The SoC variation curve indicates a moderate decrease of approx. 2.3% during the isolated regime, corresponding to a balancing energy discharge.

4.2.2. Performance Indicator Analysis

Table 8 presents the mean values and standard deviations for the performance indicators evaluated in the D1 regime compared to the baseline steady-state regime.

A reduction of VDI of approximately 27% was found, reflecting the efficiency of the coordinated reactive control between PV and BESS.

Also, the ENS decreased by 12% due to the short reaction time of the storage system and the priority management of critical loads.

The GRI, calculated based on the normalized time-integrated performance, increased from 0.82 (baseline) to 0.91, which confirms the increase in dynamic stability in islanding regime.

4.2.3. Interpretation and Discussion

The results highlight the critical role of the BESS system in maintaining microgrid stability under mains failure conditions.

The grid-forming control ensures frequency restoration in less than 0.3 s, while the PV inverter contributes to voltage compensation through local reactive control.

The synergy between these two components, coordinated by the EMS, demonstrates that the proposed architecture can prevent major power losses and synchronism instabilities, characteristic of systems without islanding capability.

Compared to the reference values in the IEEE literature for similar microgrids, the response obtained falls within the recommended performance limits: frequency deviations < 0.5 Hz and voltage < ±5% in 95% of the time.

Scenario D1 demonstrates that the tested microgrid has a high technological resilience to power losses, due to:

the fast reaction of the BESS through grid-forming control;

the voltage regulation of the PV inverter;

the EMS load prioritization mechanism.

These results confirm the efficiency of the hybrid PV–BESS architecture in preventing local blackouts and maintaining energy continuity at the level of critical users.

The results confirm that the proposed architecture allows a safe and fast switching between grid-connected and islanded regimes, with minimal deviations of the power quality parameters.

Next, scenario D2 is analyzed, which evaluates the system behavior under communication failure conditions between the EMS and the inverters.

4.3. Scenario D2: Loss of EMS–Inverter Communication

4.3.1. General Description of the Event

Scenario D2 aims to assess the cyber resilience of the microgrid under conditions of partial interruption of communications between the EMS and the local inverter controllers associated with distributed sources – the PV system and BESS.

The simulation starts from a stable operating regime connected to the grid, in which the EMS periodically transmits active and reactive power setpoints (

) every 200ms, according to the architecture presented previously (

Figure 3). At this stage, the communication is bidirectional and without significant delays, and the data flows ensure optimal coordination between the higher and local control.

At time , a simulated cyber fault is injected into the communication channel, consisting of intermittent packet losses (drop rate ≈ 40%) and increased latency above the critical threshold of 500 ms. Following this event, data flows between the EMS and the inverters are completely interrupted, and the system temporarily loses synchronization between the global command level and the local control of the sources.

In the absence of update signals, each inverter automatically enters a local fallback state, according to the logic implemented in the control firmware:

The BESS inverter, in grid-forming mode, takes over voltage and frequency control at the PCC, using a droop strategy (P=f,Q=V);

The PV inverter, configured in grid-following mode, maintains its current active power level and adjusts the reactive power according to local voltage variations;

The EMS continues to monitor the state of the communication channel and marks the moment of signal loss through a heartbeat timeout.

This transition to autonomous control occurs in less than 0.2 s from the loss of communication, without physically disconnecting the inverters, which allows the microgrid to maintain power supply to local loads under conditions of limited stability.

After the communication channel is re-established and a stable interval of valid transmissions is confirmed (typically ), the EMS initiates the gradual resynchronization procedure, restoring centralized control of the power flows.

4.3.2. Fallback Control Mechanism

After detecting the loss of communication between the EMS and the local controllers, the microgrid control architecture automatically switches to an autonomous operating mode (fallback), which allows maintaining voltage and frequency stability without the intervention of the centralized coordination layer.

The detection of the loss of the communication channel is achieved by monitoring latency indicators and data packet loss. The thresholds established for activating the mechanism are:

Latency > 500 ms or consecutive packet loss > 5

Exceeding these limits causes the expiration of the “heartbeat” signal between the EMS and the controller, which triggers the local control isolation logic.

In fallback mode, the BESS inverter becomes the reference unit of the microgrid, adopting the role of grid-forming source. It generates the local voltage and frequency at the PCC and implements the droop regulation laws:

where:

and represents the reference (nominal) values;

and are the droop slopes associated with active and reactive regulation;

define the equilibrium points before the transition.