1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder and a major global health challenge, affecting already more than 500 million people worldwide and projected to increase further in the coming decades. It is primarily characterized by insulin resistance and progressive

-cell dysfunction, leading to hyperglycemia and a high risk of complications such as cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, and retinopathy [

1]. Despite the availability of multiple therapeutic options, sustained glycemic control remains difficult for many patients, highlighting the need for effective, tailored treatments [

2,

3].

The kidney is central to glucose homeostasis by reabsorbing nearly all filtered glucose within the kidney’s proximal tubule. This process is mediated mainly by the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2, 90%) and to a lesser extent by the sodium-glucose co-transporter 1 (SGLT1, 10%) [

4,

5]. Inhibition of SGLT2 lowers the renal threshold for glucose (RTG) and therefore increases urinary glucose excretion (UGE), ultimately reducing plasma glucose concentrations. This insulin-independent mechanism has been successfully used by SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), which not only improve glycemic control but also provide additional benefits such as weight reduction and improved cardiovascular and renal outcomes [

4].

Dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor and the first drug of this class to receive approval, is widely used in the treatment of T2DM, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. Clinically, dapagliflozin is typically prescribed at 5–10 mg once daily, with 10 mg being the standard maintenance dose. It is characterized by oral efficacy, high selectivity, and durable effects on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) [

6,

7]. The pharmacokinetics (PK) of dapagliflozin are well characterized. It is rapidly absorbed, reaching peak plasma concentrations within 2 h, has a half-life of approximately 13 h, and an oral bioavailability of about 78%. The drug is primarily metabolized by UDP glucuronosyltransferase family 1 member A9 (UGT1A9) to dapagliflozin-3-O-glucuronide (D3G), which accounts for the majority of urinary excretion, while unchanged dapagliflozin contributes less than 2% [

7,

8]. Pharmacodynamically, dapagliflozin lowers the renal threshold for glucose, reduces the maximal reabsorptive capacity (TmG), and increases UGE [

9,

10], resulting in improved glycemic control in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects [

11,

12,

13].

Patients with T2DM are at increased risk of developing comorbidities. Clinical studies have demonstrated that pathophysiological factors can significantly impact the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PD) of dapagliflozin [

9]. For example, renal impairment increases systemic exposure to dapagliflozin and its metabolite, while reducing UGE and leading to diminished efficacy [

14]. Hepatic impairment similarly increases exposure, raising potential safety concerns [

9,

15]. Furthermore, food-drug interaction studies consistently report delayed time to maximum plasma concentration and reduced C

max under fed conditions. Although these food-induced changes are often considered clinically negligible from a pharmacokinetic standpoint, as they do not affect overall exposure, they may still impact the pharmacodynamic effects of UGE, and therefore its efficiency as a drug. Together, these findings underscore the difficulty of predicting drug exposure and response in diverse patient populations [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Several modeling studies have examined dapagliflozin, including population PK and exposure-response analyses in special populations [

7,

20,

21,

22], meta-analytical PK/PD approaches [

23], and physiologically based models focusing on pediatric dosing, SGLT inhibition, or drug-drug interactions [

24,

25,

26]. While each provided valuable insights, they addressed specific aspects in isolation rather than offering an integrated view of dapagliflozin pharmacology.

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) modeling provides a quantitative framework to integrate physiological, biochemical, and drug-specific data. By representing the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) in mechanistic detail, such models can simulate the impact of organ dysfunction, prandial state, and other patient-specific factors on exposure and response, offering insights beyond what can be obtained from clinical trials alone [

27,

28,

29].

Here, we present a digital twin of dapagliflozin developed by using published clinical data in healthy individuals, patients with T2DM, and those with renal or hepatic impairment. This digital twin was applied to systematically investigate the influence of renal and hepatic dysfunction as well as food intake on dapagliflozin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Our work provides a mechanistic foundation to understand inter-individual variability in dapagliflozin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, identifying its underlying causes and magnitude, and supports model-informed dose recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

The digital twin of dapagliflozin was developed as a PBPK/PD model through a systematic workflow combining clinical data curation, mechanistic modeling, and in silico simulations. This involved a structured literature search, development of an SBML-based model, parameter optimization with selected data subset, and simulation experiments reflecting clinical trial conditions. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic outcomes were then analyzed to characterize drug disposition and variability across physiological, pathophysiological and prandial states.

2.1. Systematic Literature Research and Data Curation

A systematic literature search was conducted to compile studies that reported pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data of dapagliflozin. PubMed was queried on 2024-04-23 using the terms

dapagliflozin AND pharmacokinetics, and the PKPDAI (

https://www.pkpdai.com/) database was screened in parallel [

30]. The clinical studies encompassed a diverse cohort of participants, including healthy volunteers, patients diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and studies investigating renal or hepatic impairment. Pediatric studies, animal studies, and reports lacking sufficient data were excluded from the analysis. The Supplementary Materials Figure S1 provides an overview of the literature review process. Data from eligible studies were curated in the open pharmacokinetics database PK-DB (

https://pk-db.com) [

31]. Information on demographics, disease status, dosing protocols, plasma and urine concentration-time profiles of dapagliflozin and D3G, and pharmacodynamic outcomes such as urinary glucose excretion were extracted according to established protocols [

31]. Figure-based data were digitized using WebPlotDigitizer (

https://automeris.io/) [

32], while tabular and textual data were reformatted into standardized PK-DB formats [

31]. The curated dataset, including patient and study characteristics, dosing regimens, and PK/PD outcomes, provided the basis for PBPK/PD model development and is publicly available via PK-DB (

https://pk-db.com).

Table 1 provides an overview of the curated studies, along with the PK-DB IDs for each study.

2.2. Computational Model

The PBPK/PD model was developed in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [

33,

34]. Programmatic model construction and visualization were performed using the

sbmlutils [

35] and

cy3sbml [

36,

37] libraries. Numerical solutions of the underlying ordinary differential equations (ODEs) were obtained with

sbmlsim [

38], powered by the high-performance SBML simulation engine

libRoadRunner [

39,

40]. The complete model, including simulation scripts and documentation, is available in SBML format under a CC-BY 4.0 license via GitHub (

https://github.com/matthiaskoenig/dapagliflozin-model) and archived on Zenodo 0.9.7 (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13987865) [

41].

The model comprises a whole-body framework with submodels for the intestine, liver, and kidney, linked through the systemic circulation (

Figure 1) to characterize dapagliflozin’s absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. The model has a hierarchical structure, with the whole-body model linking the submodels. Key ADME processes modeled include intestinal absorption (first-order uptake from the gastrointestinal tract), hepatic and renal glucuronidation by UGT1A9 to form the major metabolite D3G, tissue distribution, renal filtration, and urinary and fecal excretion of dapagliflozin and D3G. The model has a hierarchical structure linking whole-body, intestinal, liver, and kidney submodels that capture these processes. The pharmacodynamic component linked dapagliflozin plasma concentrations to urinary glucose excretion through inhibition of renal glucose reabsorption, parameterized by fasting plasma glucose and the renal threshold for glucose. Mathematical descriptions of the submodels and ODEs are provided in the Supplementary Materials Section S3.

Several key factors influencing pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability were implemented as scaling parameters.

Renal impairment was modeled as a progressive decline in renal function using the factor f

renal, which was applied to glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and renal clearance of dapagliflozin and D3G. Scaling values were mapped from KDIGO categories: normal (eGFR ≥90 ml/min,

), mild (GFR 50–89 ml/min,

), moderate (GFR 30–49 ml/min,

), severe (GFR ≤ 30 ml/min,

), derived from KDIGO guidelines and related modeling studies [

42,

43].

Hepatic impairment was modeled using the scaling factor f

cirrhosis, representing reduced functional liver parenchyma and blood shunting. Scaling values were mapped to Child–Turcotte–Pugh classes: A (mild: 5–6 points, f

cirrhosis = 0.4), B (moderate: 7–9 points, f

cirrhosis = 0.7), and C (severe: 10–15 points, f

cirrhosis = 0.8) [

44,

45,

46,

47].

Prandial effects were incorporated via the intestinal absorption scaling factor fabsorption (fasted: 1.0, fed: 0.3).

The given dose can be modified by changing the parameters corresponding to the intravenous and oral doses of dapagliflozin, IVDOSEdap and PODOSEdap, respectively.

2.3. Model Parameterization

A subset of curated data from healthy subjects, patients with T2DM, and individuals with renal impairment following single-dose administration was used to optimize parameters using a local standard optimizer, with the optimal parameters used in the final model. The final optimized parameter set was applied consistently across all subsequent simulations without further study-specific refitting. Optimized parameter values are reported in the Supplementary Materials Section S4.

2.4. Simulations

For each curated clinical study (

Table 1), a corresponding

in silico experiment was implemented to reproduce the reported dosing regimen and study conditions. Where available, mean demographics (body weight) were applied; otherwise, standard references were used. Parameters for oral and intravenous dosing, prandial state, bodyweight, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and renal or hepatic function were adjusted according to study-specific information. Multiple dosing protocols were incorporated where applicable. To further explore sources of variability, simulation experiments and parameter scans were performed across physiologically relevant ranges for renal function, hepatic function, intestinal absorption activity, and dose to enable systematic evaluation of the influence of key physiological and pathophysiological parameters on PK/PD outcomes.

2.5. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Parameters

Pharmacokinetic parameters of dapagliflozin and D3G were calculated from plasma concentration-time curves and urinary excretion using standard non-compartmental methods. Pharmacodynamic outcomes were evaluated in terms of UGE, calculated from the simulated plasma concentration-time courses in combination with fasting plasma glucose and the renal threshold for glucose. Simulated profiles and derived pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters were compared against the curated clinical data for dapagliflozin and its primary metabolite D3G.

3. Results

3.1. Dapagliflozin Database

An extensive database of dapagliflozin’s pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics was created to develop and validate the model. A systematic literature search initially yielded 251 records. After screening according to predefined inclusion criteria, 28 studies were selected for detailed curation and formed the core dataset used to evaluate the PBPK/PD model. See Supplementary Materials Figure S1 for the study selection process. All curated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data are publicly available in the PK-DB (

https://pk-db.com) database with unique study identifiers as referenced in the manuscript (

Table 1).

3.2. Computational Model

Using the curated dataset, a digital twin in the form of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model was developed to describe the ADME of dapagliflozin and its primary metabolite, D3G, as well as its pharmacodynamic effect on urinary glucose excretion (

Figure 1). The complete model, including simulation scripts and documentation, is available in SBML format under a CC-BY 4.0 license via GitHub (

https://github.com/matthiaskoenig/dapagliflozin-model) and archived on Zenodo 0.9.7 (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17413679) [

41].

Simulations followed the respective clinical study designs, accounting for single- and multiple-dose regimens, prandial state, and renal or hepatic impairment. Additional simulations are provided in Supplementary Materials Section S5 (Figures S6–S21).

The final parameter set is summarized in the Supplementary Materials Tables S1 and S2, and the corresponding convergence and goodness-of-fit plots are provided in the Supplementary Materials Figure S5. Parameter optimization consistently reduced the cost function and yielded robust solutions across repeated runs. Simulated concentration-time showed overall good agreement with clinical data across studies, with small study-specific deviations in some pharmacokinetic datasets. All submodel visualizations are provided in Supplementary Materials Section S2 (Figures S2-S4), and all model equations and ODEs are given in Supplementary Materials Section S3.

3.3. Dose Dependency

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of dapagliflozin over an oral dose range of 0–500 mg are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. With increasing doses, plasma concentrations of dapagliflozin and its primary metabolite D3G increased accordingly, as did the amounts excreted in urine and feces. Dapagliflozin reached peak plasma levels after approximately 3 h and returned to baseline within approximately 10 h, whereas D3G showed a slightly delayed peak and elimination. The parameter scan confirmed a clear dose-dependent rise in exposure metrics (AUC and

), while half-lives remained largely unchanged. Higher doses of dapagliflozin progressively lowered RTG, leading to a nonlinear increase in urinary glucose excretion.

Time-course simulations were performed for all curated clinical dose-dependency studies. The model accurately reproduced the observed dapagliflozin and D3G plasma concentrations, urinary excretion, and UGE, with good agreement for both single-dose and multiple-dose data.

In addition to dose-dependency, glucose-dependent simulations were performed to explore how varying plasma glucose levels influence pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic outcomes (Supplementary Figure S21). While pharmacokinetics remained unchanged across glucose concentrations from 3 to 15 mM, higher glucose levels led to greater urinary glucose excretion because the filtered glucose load more frequently exceeded RTG. These simulations are consistent with clinical observations of increased glucosuria in hyperglycemic states.

3.4. Renal Impairment

The impact of renal impairment on dapagliflozin disposition and pharmacodynamics is shown in

Figure 4. Simulations were performed for four renal function groups (normal, mild, moderate, severe). Plasma concentrations of dapagliflozin were minimally affected by renal dysfunction, whereas exposure to its main metabolite (D3G) increased progressively with declining renal function. Urinary excretion of both dapagliflozin and D3G decreased with impairment, while fecal excretion remained unchanged. Across renal function strata, parent AUC and

changed modestly, while D3G exposure increased with impairment; UGE decreased markedly in moderate–severe impairment.

The pharmacodynamic response showed a pronounced reduction in UGE with declining renal function, while RTG changed slightly. In severe impairment, simulated UGE was clearly lower than under normal function (consistent with the lower filtered glucose load), whereas RTG itself was only minimally affected. At any renal function, higher plasma glucose led to higher UGE, while pharmacokinetics remained unchanged.

Comparison with clinical data from Kasichayanula2013 [

14] and FDAMB102007 [

48] confirmed these trends. The simulations reproduced the observed parent and metabolite plasma time courses and the urinary excretion profiles across renal function groups; UGE agreed reasonably well. Fecal excretion data were not available for direct comparison.

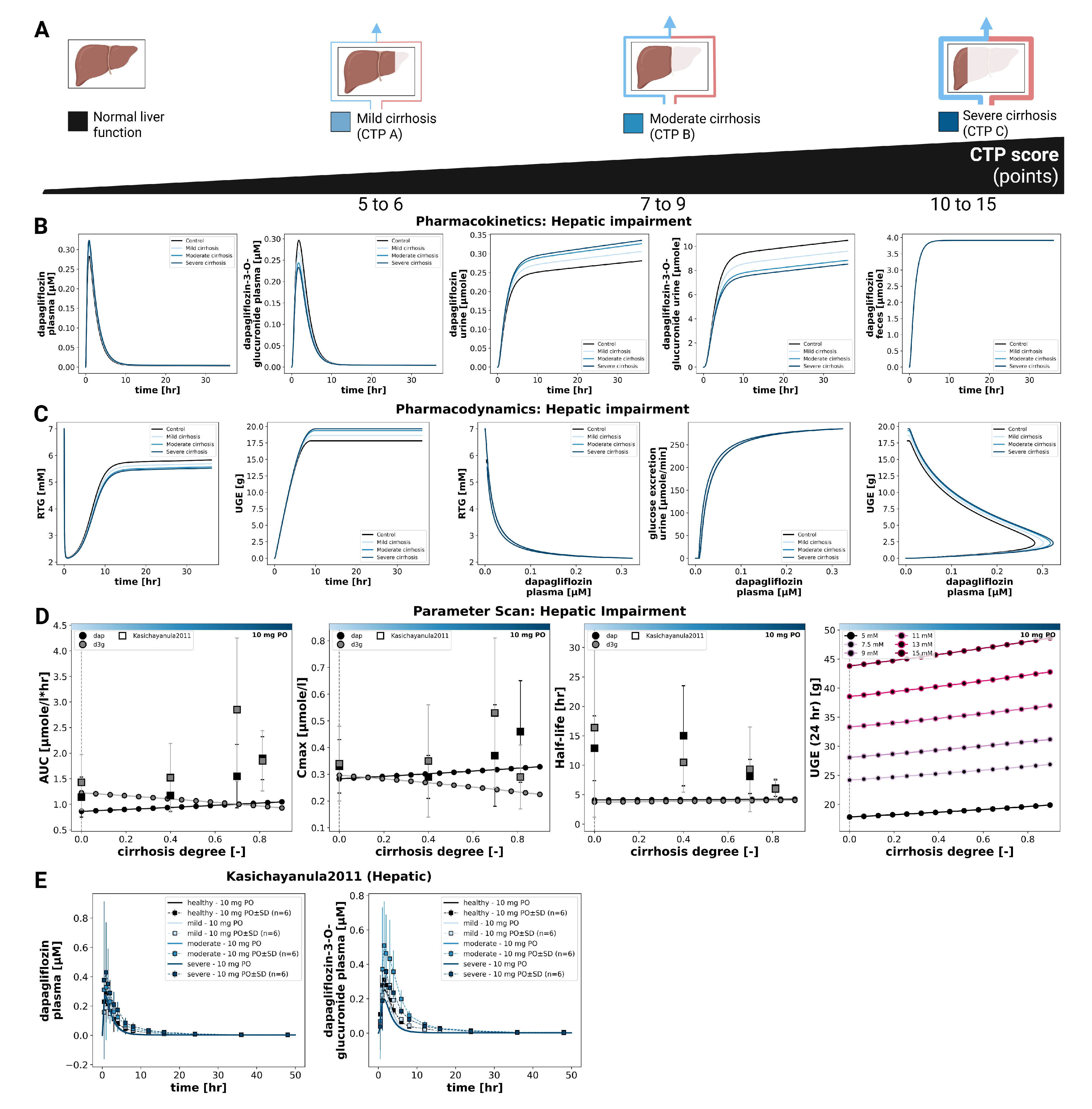

3.5. Hepatic Impairment

The effect of hepatic impairment on dapagliflozin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is summarized in

Figure 5. Simulations were performed for normal liver function and for mild, moderate, and severe cirrhosis. Plasma time courses changed only minimally across groups. With increasing severity, dapagliflozin plasma exposure rose slightly (small increases in

and AUC), whereas exposure of the main metabolite (D3G) decreased slightly. Urinary excretion showed the same inverse pattern (dapagliflozin slightly higher, D3G slightly lower), while fecal excretion was essentially unchanged. Parameter scans were consistent with these trends where half-life changed only little for both compounds.

Pharmacodynamic changes were small overall. UGE increased only slightly with cirrhosis severity, and RTG decreased marginally; the overall magnitude of change was minor. As expected, UGE remained glucose dependent at any hepatic function state (higher plasma glucose led to higher UGE), whereas pharmacokinetics were unaffected by glycemia.

Comparison with clinical data from Kasichayanula2011 [

9] supported these observations. Despite the considerable variability in the study data, the simulations reproduced the lack of large shifts in parent and metabolite plasma concentrations and the modest differences in urinary excretion. Overall, hepatic impairment exerted only modest effects on dapagliflozin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

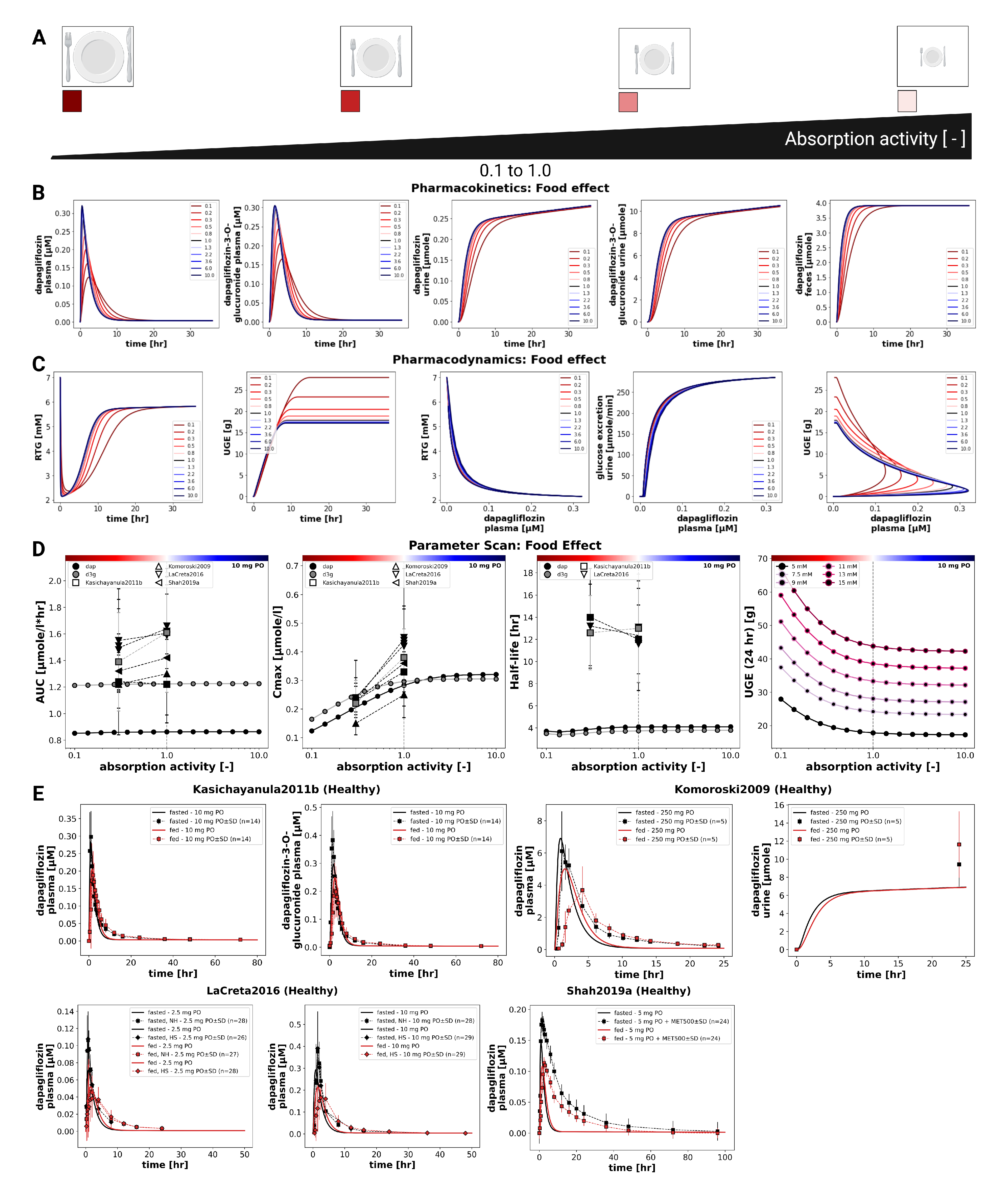

3.6. Food Effects

The influence of food intake on dapagliflozin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics was evaluated by systematically varying the fractional absorption parameter over a range from 0.1 to 10.0 (

Figure 6). Simulations were conducted for a single 10 mg oral dose. Lower absorption activity resulted in slower and smaller increases in plasma concentrations of dapagliflozin and D3G, as well as slightly slower urinary excretion of both compounds. Consistent with this effect, the pharmacokinetic analysis showed that changes in absorption predominantly affected

, while AUC and half-life remained nearly unchanged. Reduced absorption leads to a lower

with minimal effect on overall exposure.

Pharmacodynamic simulations indicated that UGE depends on dapagliflozin plasma concentrations and is therefore sensitive to altered absorption. Higher absorption activity produced a larger magnitude of UGE, whereas lower absorption led to delayed and reduced glucosuria.

Comparison with clinical studies under fasted and fed conditions confirmed these findings (Kasichayanula2011b [

16], Komoroski2009 [

17], LaCreta2016 [

18], Shah2019a [

19]). Food intake consistently reduced

by around 30–50%. Direct UGE comparisons between fed and fasted conditions were not available in these studies.

Table 1.

Summary of studies for modeling. Overview of study identifiers, PK-DB IDs, administered substance, route, dosing, and subject characteristics, including health status (H), renal impairment (RI), hepatic impairment (HI), fasting status and urinary glucose excretion (UGE) and renal threshold for glucose (RTG). DAP P = dapagliflozin plasma, DAP U = dapagliflozin urine, DAP F = dapagliflozin feces, D3G P = dapagliflozin-3 glucuronide plasma, D3G U = dapagliflozin-3 glucuronide urine

Table 1.

Summary of studies for modeling. Overview of study identifiers, PK-DB IDs, administered substance, route, dosing, and subject characteristics, including health status (H), renal impairment (RI), hepatic impairment (HI), fasting status and urinary glucose excretion (UGE) and renal threshold for glucose (RTG). DAP P = dapagliflozin plasma, DAP U = dapagliflozin urine, DAP F = dapagliflozin feces, D3G P = dapagliflozin-3 glucuronide plasma, D3G U = dapagliflozin-3 glucuronide urine

| Study |

PK-DB |

Substance |

Route |

Dosing |

Dose [mg] |

H |

RI |

HI |

T1 |

T2 |

DAP P |

DAP U |

DAP F |

D3G P |

D3G U |

Fed |

Fast |

UGE |

RTG |

| Boulton2013 [49] |

PKDB00838 |

dap, [14C]dap |

oral, IV |

single |

10, 0.080 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cho2021 [50] |

PKDB00839 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FDAMB102002 [51] |

PKDB00959 |

dap |

oral |

multi |

2.5, 10, 20, 50, 100 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| FDAMB102003 [52] |

PKDB00960 |

dap |

oral |

single, multi |

5, 25, 100 |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| FDAMB102006 [53] |

PKDB00970 |

[14C]dap |

oral |

single |

50 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

| FDAMB102007 [48] |

PKDB00971 |

dap |

oral |

single, multi |

20, 50 |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gould2013 [54] |

PKDB00840 |

dap |

oral |

single |

0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 250, 500 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| Hwang2022a [55] |

PKDB00923 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Imamura2013 [56] |

PKDB00893 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jang2020 [57] |

PKDB00913 |

dap |

oral |

multi |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kasichayanula2011 [9] |

PKDB00841 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Kasichayanula2011a [58] |

PKDB00842 |

dap |

oral |

single, multi |

2.5, 10, 20, 50 |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

| Kasichayanula2011b [16] |

PKDB00843 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

| Kasichayanula2011c [59] |

PKDB00924 |

dap |

oral |

single |

20, 50 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kasichayanula2012 [60] |

PKDB00925 |

dap |

oral |

single |

20 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kasichayanula2013 [14] |

PKDB00844 |

dap |

oral |

single, multi |

20, 50 |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

| Kasichayanula2013a [61] |

PKDB00845 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Khomitskaya2018 [62] |

PKDB00926 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kim2023 [63] |

PKDB00927 |

dap |

oral |

multi |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kim2023a [64] |

PKDB00928 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Komoroski2009 [17] |

PKDB00846 |

dap |

oral |

single, multi |

2.5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 250, 500 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| LaCreta2016 [18] |

PKDB00847 |

dap |

oral |

single |

2.5, 10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

| Obermeier2010 [5] |

PKDB00848 |

dap, [14C]dap |

oral |

single |

50 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sha2015 [10] |

PKDB00891 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Shah2019a [19] |

PKDB00849 |

dap |

oral |

single |

5 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

| vanderAartvanderBeek2020 [65] |

PKDB00929 |

dap |

oral |

single |

10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Watada2019 [66] |

PKDB00850 |

dap |

oral |

multi |

5, 10 |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

| Yang2013 [67] |

PKDB00851 |

dap |

oral |

single, multi |

5, 10 |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

4. Discussion

In this study, we established a comprehensive clinical dataset of dapagliflozin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and used it to develop a mechanistic PBPK/PD digital twin. In total, 28 clinical trials were curated, covering a broad spectrum of dosing regimens, prandial states, and populations with renal and hepatic impairment. While data availability was generally sufficient for model development, notable gaps remain. Quantitative information on fecal excretion originates from a single balance study, RTG measurements are available for only one study, and UGE under fed conditions is sparsely reported. These gaps highlight the need for more systematic reporting of PD endpoints and excretion routes in clinical pharmacology studies.

The PBPK/PD framework integrates intestinal absorption, hepatic metabolism, and renal clearance into a coherent representation of dapagliflozin disposition and effect. Robust parameter fitting and overall good agreement with observed data across studies support the reliability of the model. A distinct advantage of this mechanistic approach is the ability to investigate scenarios not easily addressed in clinical trials, such as direct comparisons of hepatic versus renal impairment or systematic exploration of absorption variability. Furthermore, pharmacodynamics are driven by total plasma concentrations via SGLT2 inhibition that modulates the renal threshold for glucose (RTG), providing a physiologically interpretable link from exposure to UGE.

The simulations reproduced the expected dose-response behavior, as increasing doses led to higher plasma concentrations and greater UGE, while half-life remained largely unchanged. Glucose-dependency analysis confirmed that pharmacokinetics were independent of plasma glucose in the tested range, whereas pharmacodynamics showed strong glucose dependence, consistent with greater UGE when plasma glucose exceeds RTG. These results align with clinical observations of increased glucosuria in hyperglycemic states.

Evaluation of organ dysfunction highlighted important differences between hepatic and renal impairment. Hepatic impairment produced only minor changes in parent exposure and small pharmacodynamic effects, despite measurable shifts in the metabolite. In contrast, renal impairment markedly increased D3G exposure and substantially reduced UGE, reflecting the central role of the kidneys in both metabolite elimination and the pharmacodynamic endpoint. Together, these findings emphasize that renal function is the dominant determinant of variability in both D3G disposition and UGE under the conditions studied.

The analysis of food effects highlights the importance of distinguishing between the extent and the rate of absorption. Although systemic exposure (AUC) remained essentially unchanged under fed conditions, both simulations and clinical data demonstrated a consistent reduction in Cmax (approximately 30–50%). The model further indicated that these changes can diminish UGE, revealing a pharmacodynamic consequence that may be overlooked when focusing solely on AUC ratios. Given the limited PD datasets under fed/fasted conditions, the food effect on dapagliflozin may warrant closer consideration when therapeutic goals depend on peak SGLT2 inhibition and UGE magnitude.

Some aspects remain insufficiently characterized. Data are incomplete for RTG measurements, fecal excretion, and UGE under fed conditions and in hepatic impairment. In addition, unexpected patterns in D3G concentrations during moderate hepatic impairment were observed and could reflect a combination of reduced UGT1A9 capacity, altered hepatic blood flow/shunting, or changes in renal handling. To elucidate these mechanisms, targeted studies will be necessary. Future work should prioritize prospective clinical datasets with standardized UGE and RTG measurements under fed and fasted conditions, larger cohorts with renal and hepatic impairment, and quantitative characterization of hepatic glucuronidation capacity. Incorporating drug-drug interaction data and extending the framework to account for inter-individual variability could further improve individualized dosing strategies. More comprehensive data on fecal elimination would also strengthen the model.

In conclusion, the present PBPK/PD model integrates diverse clinical data into a mechanistic framework that captures key pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic features across patient populations and clinical scenarios. The model provides insight into dose dependency, glucose dependency, food–drug interactions, and organ impairment, and can inform dose recommendations by quantifying the sources and magnitude of variability in drug response.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. and M.K.; methodology, N.N. and M.K.; software, N.N., M.E. and M.K.; validation, N.N., M.E. and M.K.; formal analysis, N.N., M.E., and M.K.; data curation, N.N., M.E., and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N. and M.E.; writing—review and editing, N.N., M.E., and M.K.; visualization, N.N., M.E. and M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Matthias König (MK) was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Germany) within ATLAS by grant number 031L0304B and by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Research Unit Program FOR 5151 "QuaLiPerF (Quantifying Liver Perfusion-Function Relationship in Complex Resection - A Systems Medicine Approach)" by grant number 436883643 and by grant number 465194077 (Priority Programme SPP 2311, Subproject SimLivA). This work was supported by the BMBF-funded de.NBI Cloud within the German Network for Bioinformatics Infrastructure (de.NBI) (031A537B, 031A533A, 031A538A, 031A533B, 031A535A, 031A537C, 031A534A, 031A532B).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All curated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data are publicly available in the PK-DB database (

https://pk-db.com) with unique study identifiers as referenced in the manuscript (

Table 1).

Acknowledgments

Figures were created in BioRender. König, M. (2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Harreiter, J.; Roden, M. [Diabetes mellitus: definition, classification, diagnosis, screening and prevention (Update 2023)]. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 2023, 135, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. ; IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition scientific committee. IDF DIABETES ATLAS, 10th ed.; IDF Diabetes Atlas, International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S20–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheen, A.J. Evaluating SGLT2 Inhibitors for Type 2 Diabetes: Pharmacokinetic and Toxicological Considerations. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology 2014, 10, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeier, M.; Yao, M.; Khanna, A.; Koplowitz, B.; Zhu, M.; Li, W.; Komoroski, B.; Kasichayanula, S.; Discenza, L.; Washburn, W.; et al. In Vitro Characterization and Pharmacokinetics of Dapagliflozin (BMS-512148), a Potent Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter Type II Inhibitor, in Animals and Humans. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2010, 38, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.; Liu, X.; Cui, D.; Liang, D.; LaCreta, F.; Griffen, S.C.; Lubin, S.; Quamina-Edghill, D.; Boulton, D.W. Bioequivalence, Food Effect, and Steady-State Assessment of Dapagliflozin/Metformin Extended-release Fixed-dose Combination Tablets Relative to Single-component Dapagliflozin and Metformin Extended-release Tablets in Healthy Subjects. Clinical therapeutics 2015, 37, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, D.; Tang, W.; Scheerer, M.; Danne, T.; Biester, T.; Sokolov, V.; Boulton, D.; Parkinson, J. Comparison of Pharmacokinetics and the Exposure-Response Relationship of Dapagliflozin between Adolescent/Young Adult and Adult Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2019, 85, 1820–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naagaard, M.D.; Chang, R.; Någård, M.; Tang, W.; Boulton, D.W. Common UGT1A9 Polymorphisms Do Not Have a Clinically Meaningful Impact on the Apparent Oral Clearance of Dapagliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2022, 88, 1942–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Pfister, M.; LaCreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Influence of Hepatic Impairment on the Pharmacokinetics and Safety Profile of Dapagliflozin: An Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Single-Dose Study. Clinical therapeutics 2011, 33, 1798–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Polidori, D.; Farrell, K.; Ghosh, A.; Natarajan, J.; Vaccaro, N.; Pinheiro, J.; Rothenberg, P.; Plum-Mörschel, L. Pharmacodynamic Differences between Canagliflozin and Dapagliflozin: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Study. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2015, 17, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, E.; Ramos, S.J.; Salsali, A.; Tang, W.; List, J.F. Dapagliflozin Monotherapy in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Inadequate Glycemic Control by Diet and Exercise: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2217–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Hompesch, M.; Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Hong, Y.; Pfister, M.; Morrow, L.A.; Leslie, B.R.; Boulton, D.W.; Ching, A.; et al. Characterization of Renal Glucose Reabsorption in Response to Dapagliflozin in Healthy Subjects and Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3169–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.F.; Woo, V.; Morales, E.; Tang, W.; Fiedorek, F.T. Sodium-Glucose Cotransport Inhibition with Dapagliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Pe Benito, M.; Yao, M.; Pfister, M.; LaCreta, F.P.; Humphreys, W.G.; Boulton, D.W. The Influence of Kidney Function on Dapagliflozin Exposure, Metabolism and Pharmacodynamics in Healthy Subjects and in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2013, 76, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoris, A.; Marlar, C.A. Use Of The Child Pugh Score In Liver Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Pfister, M.; Reele, S.B.; Aubry, A.F.; LaCreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Effect of a High-Fat Meal on the Pharmacokinetics of Dapagliflozin, a Selective SGLT2 Inhibitor, in Healthy Subjects. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2011, 13, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoroski, B.; Vachharajani, N.; Boulton, D.; Kornhauser, D.; Geraldes, M.; Li, L.; Pfister, M. Dapagliflozin, a Novel SGLT2 Inhibitor, Induces Dose-Dependent Glucosuria in Healthy Subjects. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2009, 85, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCreta, F.; Griffen, S.C.; Liu, X.; Smith, C.; Hines, C.; Volk, K.; Tejwani, R.; Boulton, D.W. Bioequivalence and Food Effect of Heat-Stressed and Non-Heat-Stressed Dapagliflozin 2.5- and 10-Mg Tablets. International journal of pharmaceutics 2016, 511, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.A.; Shrivastav, P.S.; Shah, J.V.; George, A. Simultaneous Quantitation of Metformin and Dapagliflozin in Human Plasma by LC-MS/MS: Application to a Pharmacokinetic Study. Biomedical chromatography : BMC 2019, 33, e4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Walt, J.S.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Pfister, M.; Boulton, D.W.; Karlsson, M.O. A Nonlinear Mixed Effects Pharmacokinetic Model for Dapagliflozin and Dapagliflozin 3-O-glucuronide in Renal or Hepatic Impairment. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2013, 2, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, V.; Yakovleva, T.; Ueda, S.; Parkinson, J.; Boulton, D.W.; Penland, R.C.; Tang, W. Urinary Glucose Excretion after Dapagliflozin Treatment: An Exposure-Response Modelling Comparison between Japanese and Non-Japanese Patients Diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2019, 21, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Aart-van der Beek, A.B.; Koomen, J.V.; Dekkers, C.C.J.; Barbour, S.J.; Boulton, D.W.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Greasley, P.J.; Abdul Gafor, A.H.; Laverman, G.D.; Li, Q.; et al. Evaluation of the Pharmacokinetics and Exposure-Response Relationship of Dapagliflozin in Patients without Diabetes and with Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2021, 60, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhou, J.; Song, L.; Ren, Y.; Hu, P.; Liu, D. A Model-Based Meta Analysis Study of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2023, 12, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Saito, R.; Nakamaru, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Yamazaki, H. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Modeling to Predict Concentrations and Actions of Sodium-Dependent Glucose Transporter 2 Inhibitor Canagliflozin in Human Intestines and Renal Tubules. Biopharmaceutics & drug disposition 2016, 37, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Pilla Reddy, V.; Parkinson, J.; Boulton, D.W.; Tang, W. Model-Informed Pediatric Dose Selection for Dapagliflozin by Incorporating Developmental Changes. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2021, 10, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, E.; Lin, J.; Tse, S.; Goosen, T.C.; Sahasrabudhe, V. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling of the Drug-Drug Interaction of the UGT Substrate Ertugliflozin Following Co-Administration with the UGT Inhibitor Mefenamic Acid. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2021, 10, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Rowland-Yeo, K. Basic Concepts in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Drug Discovery and Development. CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology 2013, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, J.E.; Yu, J.; Ragueneau-Majlessi, I.; Isoherranen, N. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling and Simulation Approaches: A Systematic Review of Published Models, Applications, and Model Verification. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2015, 43, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmanshenn, C.; Scherholz, M.; Androulakis, I.P. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Models: Approaches for Enabling Personalized Medicine. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics 2016, 43, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Hernandez, F.; Carter, S.J.; Iso-Sipilä, J.; Goldsmith, P.; Almousa, A.A.; Gastine, S.; Lilaonitkul, W.; Kloprogge, F.; Standing, J.F. An Automated Approach to Identify Scientific Publications Reporting Pharmacokinetic Parameters. Wellcome Open Research 2021, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Brandhorst, J.; Green, K.; Eleftheriadou, D.; Duport, Y.; Barthorscht, F.; Köller, A.; Ke, D.Y.J.; De Angelis, S.; König, M. PK-DB: Pharmacokinetics Database for Individualized and Stratified Computational Modeling. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D1358–D1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer, 2024.

- Hucka, M.; Bergmann, F.T.; Chaouiya, C.; Dräger, A.; Hoops, S.; Keating, S.M.; König, M.; Novère, N.L.; Myers, C.J.; Olivier, B.G.; et al. The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML): Language Specification for Level 3 Version 2 Core Release 2. Journal of Integrative Bioinformatics 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.M.; Waltemath, D.; König, M.; Zhang, F.; Dräger, A.; Chaouiya, C.; Bergmann, F.T.; Finney, A.; Gillespie, C.S.; Helikar, T.; et al. SBML Level 3: An Extensible Format for the Exchange and Reuse of Biological Models. Molecular Systems Biology 2020, 16, e9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, M. Sbmlutils: Python Utilities for SBML. Zenodo, 2024. [CrossRef]

- König, M.; Dräger, A.; Holzhütter, H.G. CySBML: A Cytoscape Plugin for SBML. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2402–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, M. Cy3sbml - SBML for Cytoscape. Zenodo, 2025. [CrossRef]

- König, M. Sbmlsim: SBML Simulation Made Easy, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Somogyi, E.T.; Bouteiller, J.M.; Glazier, J.A.; König, M.; Medley, J.K.; Swat, M.H.; Sauro, H.M. libRoadRunner: A High Performance SBML Simulation and Analysis Library. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, C.; Xu, J.; Smith, L.; König, M.; Choi, K.; Sauro, H.M. libRoadRunner 2.0: A High Performance SBML Simulation and Analysis Library. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemitz, Nike; Elias, M.; König, M. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) Model of Dapagliflozin. Zenodo, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallol, B.S.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.M.; König, M. Insights into Intestinal P-glycoprotein Function Using Talinolol: A PBPK Modeling Approach, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Child, C.G.; Turcotte, J.G. Surgery and Portal Hypertension. Major Problems in Clinical Surgery 1964, 1, 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, R.N.; Murray-Lyon, I.M.; Dawson, J.L.; Pietroni, M.C.; Williams, R. Transection of the Oesophagus for Bleeding Oesophageal Varices. The British Journal of Surgery 1973, 60, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köller, A.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.M.; König, M. Prediction of Survival After Partial Hepatectomy Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Indocyanine Green Liver Function Tests. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 730418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köller, A.; Grzegorzewski, J.; König, M. Physiologically Based Modeling of the Effect of Physiological and Anthropometric Variability on Indocyanine Green Based Liver Function Tests. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 757293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA 202293Orig1s000 Review (FDAMB102007). Impact of Renal Impairment on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dapagliflozin Was Studied in a Single (50 Mg) and Multiple Dose (20 Mg)., 2013.

- Boulton, D.W.; Kasichayanula, S.; Keung, C.F.A.; Arnold, M.E.; Christopher, L.J.; Xu, X.S.; Lacreta, F. Simultaneous Oral Therapeutic and Intravenous 14C-microdoses to Determine the Absolute Oral Bioavailability of Saxagliptin and Dapagliflozin. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2013, 75, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, J.; Yoo, Y.; Cho, M.; Sohn, S.; Lee, B.J. Improved Manufacturability and In Vivo Comparative Pharmacokinetics of Dapagliflozin Cocrystals in Beagle Dogs and Human Volunteers. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA 202293Orig1s000 Review (FDAMB102002). Pharmacokinetics for Multiple-Dose Administration of Dapagliflozin in Healthy Subjects., 2013.

- FDA. FDA 202293Orig1s000 Review (FDAMB102003). Bioequivalence Assessment during Multiple-Dose Administration of Dapagliflozin in Subjects with T2DM., 2013.

- FDA. FDA 202293Orig1s000 Review (FDAMB102006). Urinary and Fecal Excretion Data Following a 50 mg Dose of Dapagliflozin., 2013.

- Gould, J.C.; Kasichayanula, S.; Shepperly, D.C.; Boulton, D.W. Use of Low-Dose Clinical Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Data to Establish an Occupational Exposure Limit for Dapagliflozin, a Potent Inhibitor of the Renal Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology : RTP 2013, 67, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.G.; Jeong, S.I.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, Y.; Ji, S.C.; Lee, S.; Park, M.K. Common ABCB1 SNP, C3435T Could Affect Systemic Exposure of Dapagliflozin in Healthy Subject. Translational and clinical pharmacology 2022, 30, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, A.; Kusunoki, M.; Ueda, S.; Hayashi, N.; Imai, Y. Impact of Voglibose on the Pharmacokinetics of Dapagliflozin in Japanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes therapy : research, treatment and education of diabetes and related disorders 2013, 4, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.; Jeon, J.Y.; Moon, S.J.; Kim, M.G. Evaluation of the Pharmacokinetic Interaction Between Lobeglitazone and Dapagliflozin at Steady State. Clinical therapeutics 2020, 42, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Chang, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Liu, X.; Yamahira, N.; LaCreta, F.P.; Imai, Y.; Boulton, D.W. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dapagliflozin, a Novel Selective Inhibitor of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter Type 2, in Japanese Subjects without and with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2011, 13, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Shyu, W.C.; Zhang, W.; Pfister, M.; Griffen, S.C.; Li, T.; LaCreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Lack of Pharmacokinetic Interaction between Dapagliflozin, a Novel Sodium-Glucose Transporter 2 Inhibitor, and Metformin, Pioglitazone, Glimepiride or Sitagliptin in Healthy Subjects. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2011, 13, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Chang, M.; Liu, X.; Shyu, W.C.; Griffen, S.C.; LaCreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Lack of Pharmacokinetic Interactions between Dapagliflozin and Simvastatin, Valsartan, Warfarin, or Digoxin. Advances in therapy 2012, 29, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Griffen, S.C.; Lacreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Effects of Rifampin and Mefenamic Acid on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dapagliflozin. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2013, 15, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomitskaya, Y.; Tikhonova, N.; Gudkov, K.; Erofeeva, S.; Holmes, V.; Dayton, B.; Davies, N.; Boulton, D.W.; Tang, W. Bioequivalence of Dapagliflozin/Metformin Extended-release Fixed-combination Drug Product and Single-component Dapagliflozin and Metformin Extended-release Tablets in Healthy Russian Subjects. Clinical therapeutics 2018, 40, 550–561.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Choi, M.; Jin, B.H.; Hong, T.; Kim, C.O.; Yoo, B.W.; Park, M.S. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug-Drug Interactions between Evogliptin and Empagliflozin or Dapagliflozin in Healthy Male Volunteers. Clinical and translational science 2023, 16, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Lee, S.; Sung, S.; Kim, E.; Jang, I.J.; Chung, J.Y. A Comparison of the Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Dapagliflozin Formate, an Ester Prodrug of Dapagliflozin, to Dapagliflozin Propanediol Monohydrate in Healthy Subjects. Drug design, development and therapy 2023, 17, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Aart-van der Beek, A.B.; Wessels, A.M.A.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Touw, D.J. Simple, Fast and Robust LC-MS/MS Method for the Simultaneous Quantification of Canagliflozin, Dapagliflozin and Empagliflozin in Human Plasma and Urine. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences 2020, 1152, 122257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watada, H.; Shiramoto, M.; Ueda, S.; Tang, W.; Asano, M.; Thorén, F.; Kim, H.; Yajima, T.; Boulton, D.W.; Araki, E. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dapagliflozin in Combination with Insulin in Japanese Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2019, 21, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Bui, A.; Chang, M.; Liu, X.; Kasichayanula, S.; Griffen, S.C.; Lacreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Single- and Multiple-Dose of Dapagliflozin, a Selective Inhibitor of SGLT2, in Healthy Chinese Subjects. Clinical therapeutics 2013, 35, 1211–1222.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).