1. Introduction

Children with obesity affect quality of life and well-being with various social and psychological problems. Obesity in children and adolescents has risen from the rates it was in the 1970s by approximately three times (CDC, 2024). It has extremely been stigmatized because of personal choices; yet new research shows that a variety of mental health issues such as depression can be a leading cause in developing obesity in children and adolescents (Haqq et al., 2021). Recent studies show about 17% of children from 10-17 years have obesity (Elizabeth Williams, 2023; Sanyaolu et al., 2019) in the United States, though it was based upon the children’s body mass index (BMI), which has had recent pushback. Childhood obesity can cause significant medical and psychosocial complications. It can cause too many health issues such as obesity, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, fatty liver disease and depression and affect the quality of life. Due to its profound long-term consequences that may persist across generations, widespread research has been conducted on childhood obesity.

Childhood obesity has increased globally over the last few decades. In 2010, the World health organization estimated that more than 40 million children less than 5 years of age were overweight globally (WHO, 2012). In 2019-2020, 30.5% of children aged 10-17 in California were either overweight or obese (KidsData, 2019). The prevalence of overweight and obese children in California has increased since 2003 (Center, 2008). Among teens, nearly 1 in 5 in the state were either overweight or obese, totaling about 1.2 million adolescents ((CHIS), 2023). In Mexico, up to 40% of children are overweight and obese, while 32% in Lebanon, and 28% in Argentina. In European countries, 1 in 3 school-aged children are living with overweight or obesity. In Denmark, 13% of primary school children are classified as overweight or obese, and it increases to 19% when they graduate from school. During the COVID-19 pandemic, childhood obesity in California increased from 19% to 26% (Iacopetta et al., 2024; Nguyen, 2023). In the United Kingdom, 1 in 10 children observed having mental health disorder, emotional, and behavioral issues. In a recent meta-analysis study, it was established a relationship between mental health, depression, and childhood obesity (Sutaria et al., 2019). Childhood obesity has increased in 186 countries for girls and 195 countries for boys. It is estimated that globally, 65.1 million girls and 94.2 million boys aged 5 to 19 are living with obesity (Phelps et al., 2024). This review summarized how overweight children suffer from various mental health conditions such as anxiety, peer pressure, depression, and stress that affects both physical and emotional well-being. A systems approach to childhood obesity fosters shared understanding of its root causes and supports collaborative, community-based interventions.

2. How Much of a Problem Is Childhood Obesity?

Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents aged 5–19 years are defined based on body mass index (BMI)-for-age. Overweight is classified as BMI more than 1 standard deviation above the World Health Organization (WHO) growth reference median, while obesity is defined as more than 2 standard deviations above the WHO growth reference median (GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2024). Overweight and childhood obesity are defined as excess and abnormal accumulation of fat that cause a risk. This is a global problem and steadily affecting many low- and middle-income countries in urban population (GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2024).

Childhood obesity is a public health challenge that is becoming an increasingly prevalent problem in the U.S. According to a German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS) study, the overweight incidence in children and adolescents between 3 to 17 years was 15.4% and the obesity frequency amounted to 5.9%, which is a 50% rise based on the studies from 80s (Förster et al., 2023). Originally, it was predominantly a chronic disease seen in adults, yet new data shows a concerning growth in obesity in children. The prevalence of obesity among U.S children and adolescents was 19.7%. Approximately, 15 million children and adolescents are obese, which is around 20% of that age group (CDC, 2024) and more than 35 million children under the age of 5 years are estimated to be overweight globally (GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2024). More than 390 million children and adolescents were overweight between the age of 5 to 19 years in 2022 and rising from 8% in 1990 to 20% in 2022 (GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2024). It is classified as a public health challenge and is the initial stage leading to several diseases, including pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes, as well as cardiovascular issues such as heart disease, asthma, high cholesterol and blood pressure and stroke (Committee, 2021). It can also lead to adulthood obesity further complicating this issue. Additionally, childhood obesity can lead to social stigmatization, as well as various mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, all contributing to a low self-esteem (Segal & Gunturu, 2025). Furthermore, overweight and obese children show higher impulsivity, lack of attention, low reward sensitivity, self-regulation, and mental flexibility compared to normal weight children (Martin, 2014). In overweight children, teasing and social rejection are also associated with lower performances in school. Lifestyle intervention for childhood overweight management might improve the school performances through improvement of self-esteem and quality of life. Notably, boys were more prone to obesity compared with girls between age 3 to 19 (Lobstein & Brinsden, 2019).

2.1. Complex Causes and Factors Affecting Childhood Obesity

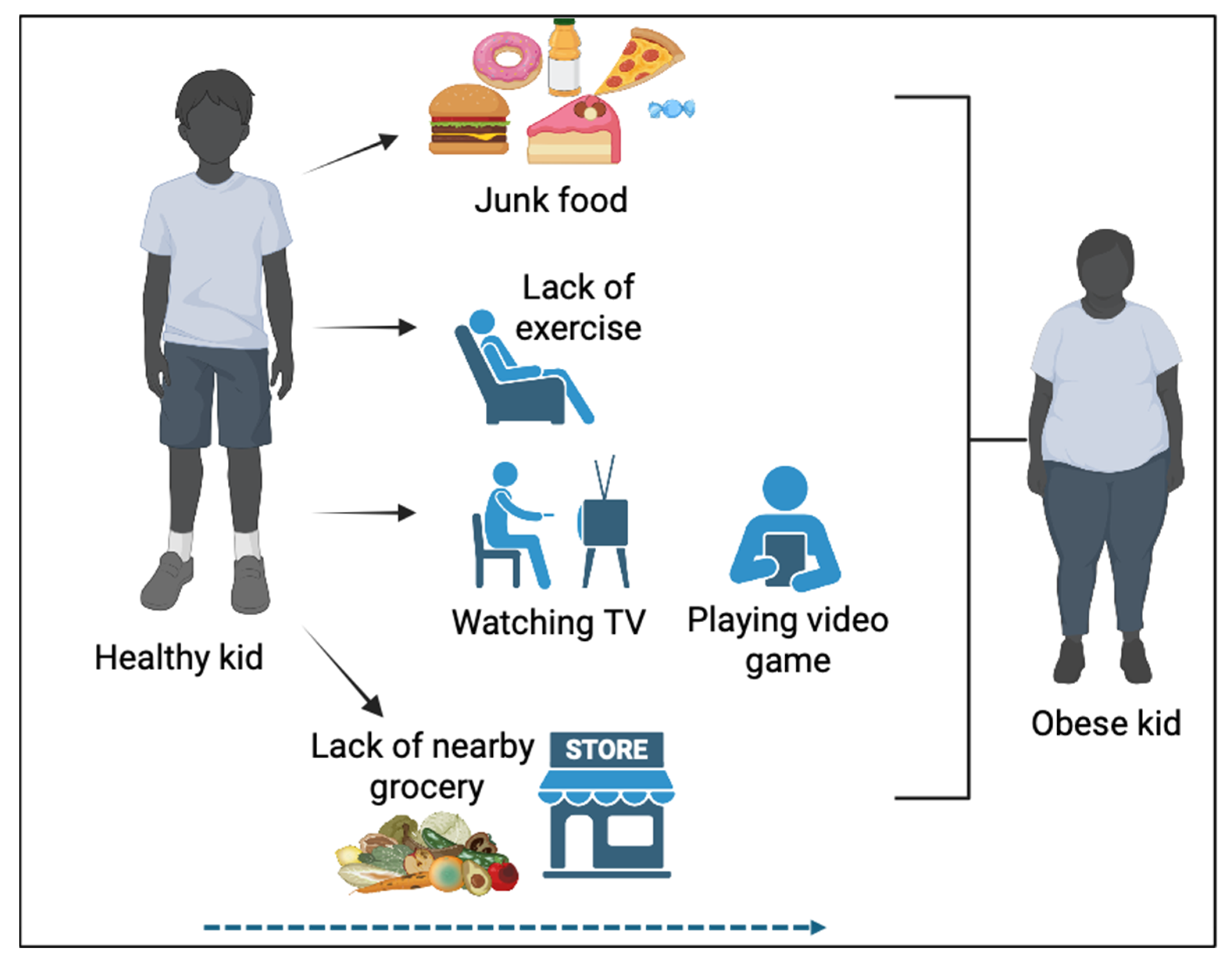

Childhood obesity impacts daily life negatively. Childhood obesity is a complex and multifactorial issue influenced by a variety of factors (Figure 1). Children with family history of obesity due to genetics or hormonal imbalances, are at higher risk of obesity. Today, fast food and processed meals, classified as “junk” food, are far more affordable, and more conveniently accessible with aggressive marketing than healthier food options (Fuhrman, 2018). Marketing of food by bright packaging, celebrity endorsements, and using cartoon characters, make children more attractive and prefer to eat unhealthy foods. Increased intake of high calorie food, high in fat and sugar is also considered as a major contributor for childhood obesity (Sahoo et al., 2015). Physical inactivity, sedentary behavior, such as watching television, excessive screen time with television, computer and gaming, and smartphone screen time has become increasingly prevalent within youth, leading to a lack of exercise and movement in a child’s daily activity (Julian McDougall & Michael J Duncan, 2008; Kenney & Gortmaker, 2017). Sleep duration and quality also significantly affect childhood obesity (Han et al., 2022). The environment where the child is raised is one of the significant factors affecting childhood obesity (Campbell, 2016; Sahoo et al., 2015). Environmental factors including home and family, family dietary habits, community and social, socio-cultural influences are the major contributors to childhood obesity (Ayala et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2015). Furthermore, traffic exposure, air pollution, emissions from urbanized areas, and parental smoking also significantly impact childhood obesity (Guo et al., 2025).

Figure 1.

Progression towards obesity due to unhealthy diets, lack of exercise, and environmental factors. A child who frequently eats junk food, watches TV, plays video games, avoids outdoor games, and lacks access to healthy food nearby is more likely to become obese.

Figure 1.

Progression towards obesity due to unhealthy diets, lack of exercise, and environmental factors. A child who frequently eats junk food, watches TV, plays video games, avoids outdoor games, and lacks access to healthy food nearby is more likely to become obese.

2.2. Childhood Obesity Is Lined with Mental Health

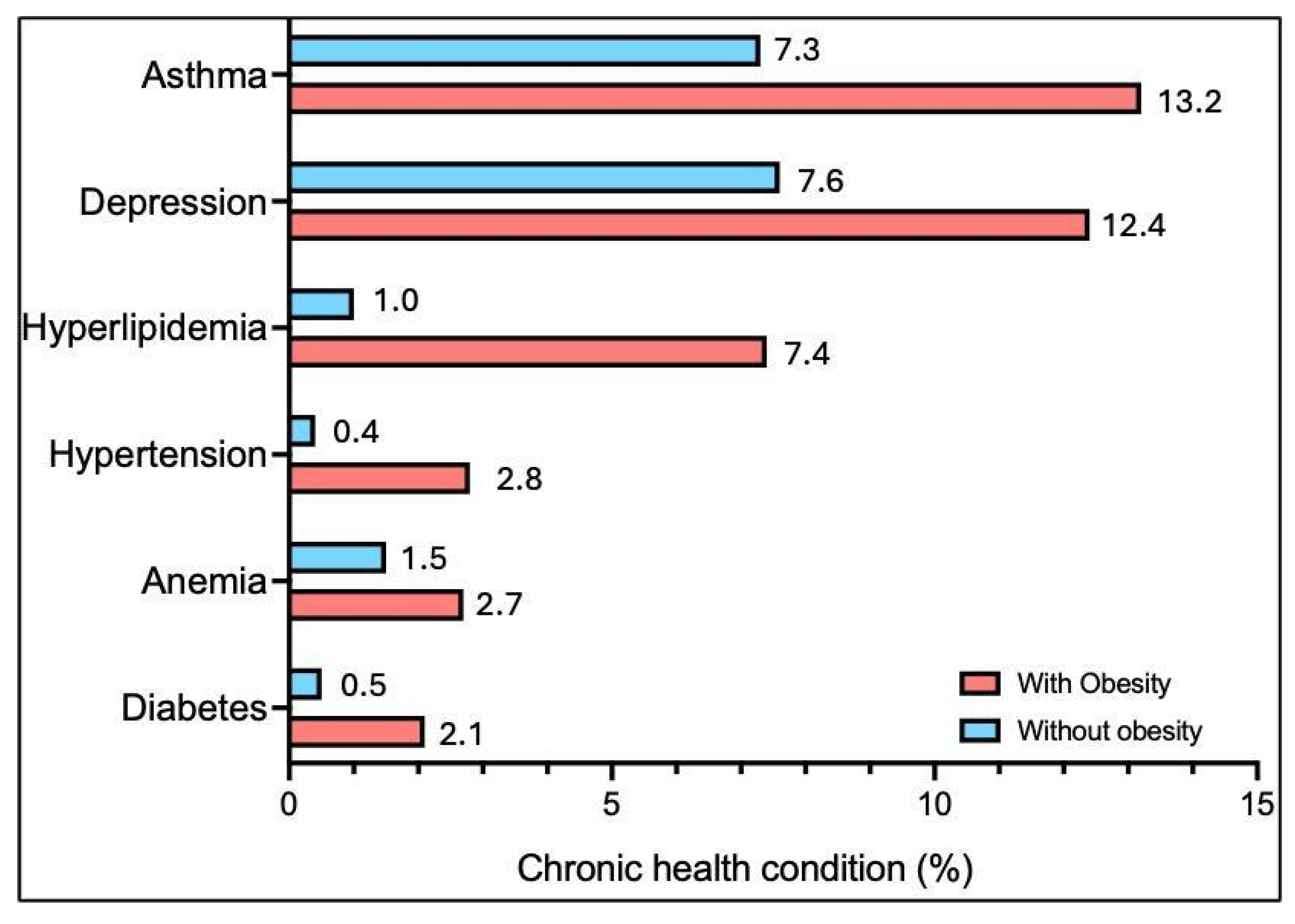

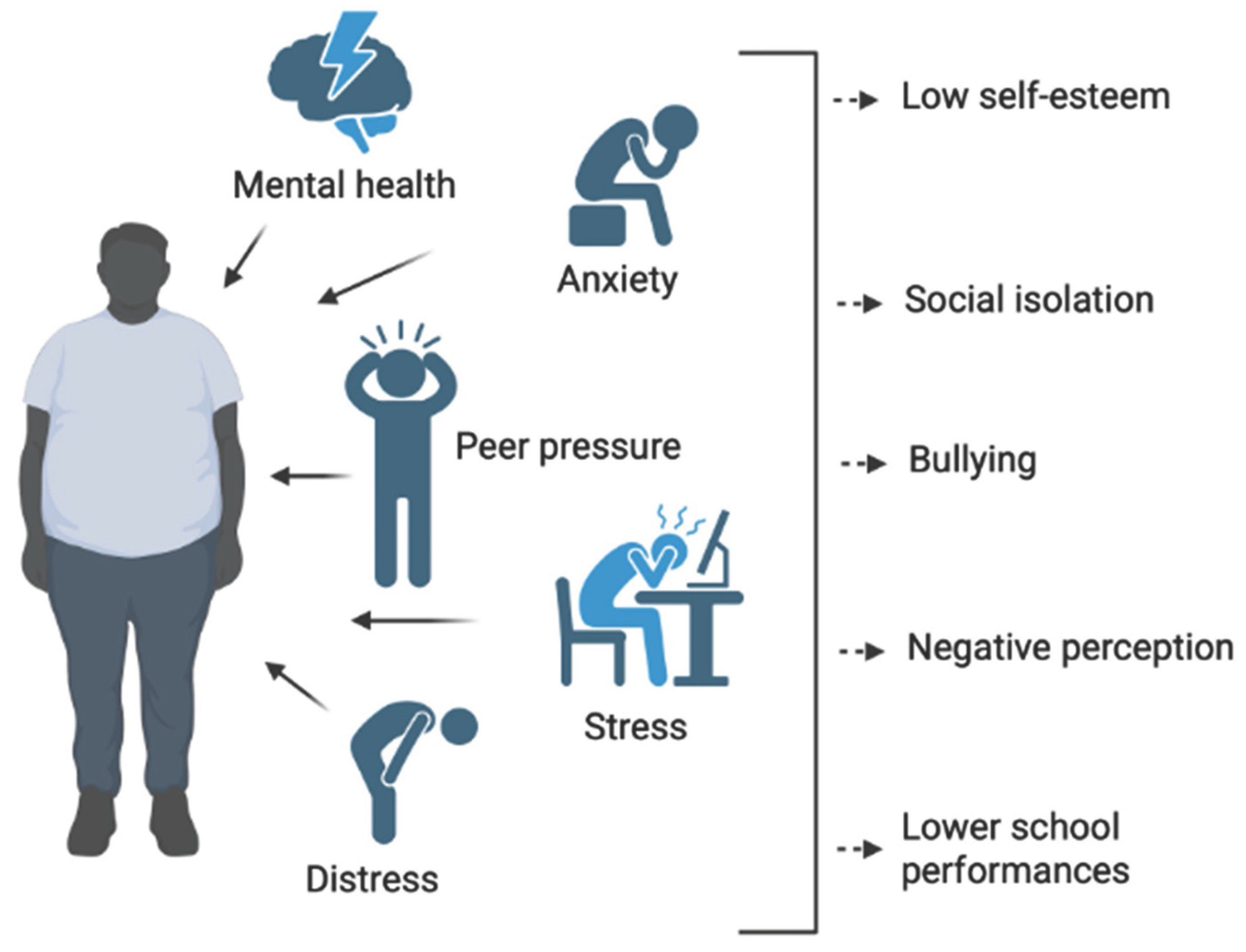

Mental health issues are diverse, but in obesity research, depressive mood disorders are among the most prevalent and significant (Faulconbridge & Bechtel, 2014). Children with obesity have a significantly higher rate of other chronic medical conditions and significant disparity in depression rates between children with and those without (Figure 2). Children with obesity are more likely to have asthma, depression, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, anemia, and diabetes (Elizabeth Williams, 2023). In addition, children with obesity experience physical and psychological challenges, including social stigma, bullying and social isolation, low self-esteem, unhealthy coping behavior, academic and behavioral problems, and increased risk of chronic diseases (Cheng et al., 2022; Haqq et al., 2021; Pont et al., 2017; Rankin et al., 2016) (Figure 3). Peer pressure can lead to a low-self-esteem, and as recent studies show, a low self-esteem can adopt depression and anxiety creating another reason for childhood obesity to become prevalent (Ajele et al., 2025; Haqq et al., 2021; Merino et al., 2024). However, mental issues can largely contribute to and from childhood obesity as well (Newson et al., 2024). Lack of proper sleep can contribute like lack of exercise in fostering childhood obesity (Gohil & Hannon, 2018; Richter et al., 2024). The reported literature highlights a potential association between childhood obesity and mental health problems.

Figure 2.

Chronic condition diagnoses among Medicaid children with obesity compared to those without. Analysis limited to children aged 10–17 continuously enrolled in Medicaid with no more than a 45-day gap during the year. Source: KFF analysis of T-MSIS Research files, 2019 (Elizabeth Williams, 2023).

Figure 2.

Chronic condition diagnoses among Medicaid children with obesity compared to those without. Analysis limited to children aged 10–17 continuously enrolled in Medicaid with no more than a 45-day gap during the year. Source: KFF analysis of T-MSIS Research files, 2019 (Elizabeth Williams, 2023).

Figure 3.

The impact of mental health conditions, stress, and anxiety on childhood obesity. Anxiety, peer pressure, stress, and emotional distress can negatively affect a child’s well-being, contributing to obesity.

Figure 3.

The impact of mental health conditions, stress, and anxiety on childhood obesity. Anxiety, peer pressure, stress, and emotional distress can negatively affect a child’s well-being, contributing to obesity.

2.3. Environmental Factor

Environmental factors play a significant role in childhood obesity, including the child’s social environment with family, peers, friends, and teachers (Figure 1 and 3). Parents have a crucial responsibility in preventing obesity (Lindsay et al., 2006). They can encourage healthy behaviors, physical activity, promote balanced diets, shaping a child’s mindset toward nutrition, and controlling the home environment (Lindsay et al., 2006). By limiting unhealthy, high-sugar foods and fostering an active lifestyle, parents can set positive examples for their children. Conversely, sedentary habits in parents can discourage outdoor play and physical activity, negatively impacting a child’s health (Tomayko et al., 2021). Beyond the family, a child’s social environment, including interactions with friends, teachers, and classmates, can also contribute to obesity (Ayala et al., 2021). Bullying, low self-esteem, and negative role models can lead to emotional stress, poor eating habits, and reduced physical activity, all of which increase the risk of childhood obesity. Social relationships, environment beyond family, peers, teachers, and community networks largely influence children’s risk of obesity (Ayala et al., 2021).

2.4. Access of Food and Dietary Habits

Availability of unhealthy food in neighborhoods with limited access to grocery stores is affecting obesity very frequently in young children (Figure 1). Food deserts are a prime example for childhood obesity. Food deserts are the areas of low-income neighborhoods, and they have limited access to affordable, nutritious food. The United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS) defines “food deserts” as locations in which there is either restricted or no access to a variety of wholesome food options, such as low-fat dairy products and fresh produce such as fruits and vegetables (Key et al., 2023; Ploeg, 2010). Geographic location of food markets, grocery stores, and supermarkets, lack of proper public transport affected people for easy access to healthy choices (Odoms-Young et al., 2024). USDA-ERS presented a study to Congress that showed about 2.3 million people live greater than one mile from the nearest supermarket and do not have a car (Michele Ver Ploeg, 2009). Supermarkets and grocery stores are essential in providing people with healthier, more wholesome choices, however unevenly distributed grocery stores and food outlets can put a strain on people in urban areas void of healthy food that promotes more calories. While urban populations tend to have more access to public transport, it can still cause a travel burden. Similarly, people living in suburban or rural areas do not have much access to public transportation. Thus, nearby gas stations, convenience stores, and fast-food outlets become a main and convenient source of nutrition. These establishments tend to offer high calorie, low nutrient food like sugar drinks, processed snacks, and fast food which may contribute to weight gain and obesity (Key et al., 2023).

2.5. Watching Television and Smartphone

Excessive screen time, including television, gaming, and smartphone use, has been strongly linked to an increased risk of childhood obesity (Figure 1) (Bakour et al., 2022; Engberg et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2017). One cross sectional study reported that heavy sedentary screen time is associated with being overweight and heaviest among 10,000 children (Bakour et al., 2022). Studies have shown that children who spend more than two hours a day on screens are significantly more likely to be overweight due to the increase of sedentary habits (Fang et al., 2019). A meta-analysis found that children and adolescents with the highest screen time had a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) by 0.7 kg/m², and a longitudinal study attributed up to 60% of the 4-year incidence of overweight in children aged 10 to 15 years to excessive television viewing (Robinson et al., 2017). Several mechanisms contribute to this link, including increased eating while viewing screens, often involving high-calorie snacks, exposure to food advertising that influences unhealthy eating habits, and reduced physical activity and sleep (Robinson et al., 2017). Smartphone use also presents specific risks, with university students who used their smartphones for five or more hours a day showing a 43% higher risk of obesity (Glenn, 2019) (Brodersen et al., 2023). Teens who spent more than two hours daily on smartphones were more likely to consume junk food and fewer fruits and vegetables, and those who engaged in excessive smartphone gaming were over twice as likely to be overweight or obese (Bakour et al., 2022; Brodersen et al., 2023). To counteract these risks, experts recommend limiting children’s screen time to no more than two hours per day, while promoting physical activity and healthy eating habits (Hospital, 2025; Porri et al., 2024).

2.6. Lack of Physical Exercise

Lack of physical activity is a major factor contributing to childhood obesity (

Figure 1). The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that children engage in at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily, yet over 75% of U.S. children do not meet this standard (Chaabene et al., 2024; Grao-Cruces et al., 2020). Physical inactivity leads to an energy imbalance, where caloric intake exceeds energy expenditure, resulting in weight gain (Feter et al., 2023; Shook et al., 2015; Westerterp-Plantenga, 2020). Moreover, insufficient exercise hampers fat burning and reduces the development of fundamental motor skills necessary for engaging in physical activities (Kolnes et al., 2021). Long-term consequences of physical inactivity during childhood include increased risks of morbidity and mortality in adulthood due to chronic health conditions (Feter et al., 2023). Factors contributing to the lack of physical activity includes increased screen time, insufficient physical education in schools, inadequate facilities for exercise, and the rise of sedentary behaviors, such as video gaming (Yiting et al., 2023). Addressing these issues requires comprehensive strategies, such as increasing physical education in schools, implementing family-centered interventions, promoting active play, and advocating for public health measures to increase physical activity among children. By taking these steps, we can help mitigate childhood obesity and improve long-term health outcomes.

3. Effect of Obesity on Health and Behavior

3.1. Mental Health Impacts

Obesity has significant mental health impacts, particularly in children, who often experience low self-esteem and body image issues (Iversen et al., 2024). The stigma associated with being overweight can lead to social isolation, bullying, and a negative perception of oneself (Figure 3). These challenges may affect a child’s ability to engage in physical activities or form positive social connections, time constraints or technology dependence, hindering social interactions further exacerbating feelings of inadequacy (Gajalakshmi & Meenakshi, 2023; Veitch et al., 2010). Moreover, obese individuals are at an increased risk for mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. The constant stress of dealing with societal pressures, as well as internalized negative beliefs about their body, can contribute to emotional distress (Merino et al., 2024). Additionally, emotional eating becomes a coping mechanism for many, where individuals turn to food to manage negative feelings, creating a vicious cycle of weight gain and emotional instability (Craven & Fekete, 2019; Dakanalis et al., 2023; Frayn et al., 2018). This interconnection between mental health and obesity can hinder not only physical health but also emotional well-being, making it essential to address both aspects when seeking solutions.

3.2. Overweight and Depression

An elevated body mass index (BMI) is linked to an increased chance of a chronic course of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Fulton et al., 2022). The odds of developing major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety increase as a function of the number of coexisting metabolic impairments, such as those characteristics of metabolic syndrome (Kokka et al., 2023; Mehdi et al., 2023). MDD is a debilitating condition with genetic, epigenetic, and environmental contributions. Depression can manifest in various ways, modulating homeostatic functions such as appetite and sleep that can in turn further alter mood. Anxiety accompanies depression in most cases and is indicative of a poorer mental health (Fulton et al., 2022). Obesity is coupled to various structural and functional changes in the brain that are remarkably similar to those observed in depressive disorders, such as region-specific increases in cell density and compromised neural connectivity and excitability (Bonin et al., 2024; Gibson-Smith et al., 2020).

3.3. Stigma and Public Perception

Obesity stigma is extremely relevant in our society and has become a global health challenge (Brown et al., 2022). Despite the increased prevalence of obesity in recent years, obesity stigma seems to have increased and proportion of obesity-related costs also due to obesity stigma (Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022). A recent report published by the WHO revealed that school-aged children with obesity experience a 63% higher chance of being bullied, 54% of adults with obesity reported being stigmatized by their co-workers, and 69% of adults with obesity reported experiencing stigmatization from healthcare professionals (Westbury et al., 2023).

4. Childhood Obesity and Socioeconomic Challenges

Childhood obesity is associated with many social challenges which started very early in life and had long term effects. In this multifaceted challenge include the environment, food insecurity, barriers to intervention, and long-term consequences (Ayala et al., 2021; Deal et al., 2020; Saleh et al., 2024). Children start to develop attitudes and health behaviors at 5 years of age. Families with lower socioeconomic status are associated with increased rates of childhood obesity. However, this increased trend is not the same at all socioeconomic levels. Social determinants of obesity are complete when health inequalities related to obesity are increasing (Frederick et al., 2014).

4.1. Environmental Condition

Poverty, living conditions, access to transport, and social support plays a part in determining risk of obesity (Jia et al., 2021). In addition, study showed that higher BMI during childhood is associated with exposure to smoking by parents or in the neighborhood, and traffic related air pollution (Guo et al., 2025; McConnell et al., 2015). Both indoors and outdoors air pollution exposure also affecting to higher BMI such as automobile exhaust nitrogen dioxide, other gases released from burning of fossil| fuels, and atmospheric particles (Guo et al., 2025). It was noted to understand environmental exposure to take appropriate action to reduce the increasing childhood obesity. Obesity prevalence differs by geographical region in the U.S with the South and the Midwest having the highest level of obesity among adults (CDC, 2023; Myers et al., 2015). The Midwest and South also have high rates of diabetes and metabolic syndrome, which frequently accompany obesity (Gurka et al., 2018). Approximately 55% of global increases in BMI can be attributed to rising BMI in rural areas, and this may be as high as 80% in low- and middle-income countries ((NCD-RisC), 2019; Lee et al., 2000).

Weight gain occurring even in the presence of resources or poverty relief suggests that focusing solely on individual and environmental factors may not fully explain the development of obesity. Systemic environmental changes, such as adding sidewalks or increasing access to fruits and vegetables in a corner store often require longer time frames to show adequate impact, which may not be reported in academic studies. Moreover, the small or inconsistent changes observed when such resources are introduced highlights the need of further investigation into deeper realms of social hierarchical constructs. Continued research into both individual behaviors and environmental factors is essential to improve more effective strategies for the treatment and prevention of obesity. Targeting personal habits, diets, routines of physical exercise, and sleep time as well as easy access to healthy food, exercise friendly infrastructure, and community healthcare expansion will help to mitigate childhood obesity.

4.2. Food Insecurity

Families with limited resources may have restricted access to healthy food, leading to getting on cheaper, calorie dense options, which increases obesity risk (Ayala et al., 2021). Lack of consistent access to enough food for an active and healthy life is known as food insecurity, which affects approximately 11.8 percent of families in the United States and has been linked to obesity and diabetes (El Zein et al., 2020). Food insecurity occurs when “the intake of one or more members of a household is reduced and eating patterns are disrupted (sometimes resulting in hunger) because of insufficient money and other resources for food”. In women, food insecurity status predicts overweight/obese status differentially across racial ethnic groups (Hernandez et al., 2017b). Non-Hispanic white women who are food insecure are 41% more likely to have overweight or obesity whereas Hispanic women who are food insecure are 29% more likely to have overweight and obesity (Hernandez et al., 2017a). Among non-Hispanic black women and men, food insecurity did not predict overweight or obesity status (Lee et al., 2000; Martin & Lippert, 2012).

4.3. Barriers to Intervention

Barriers to intervention in obesity are multifaceted, with several key factors contributing to the difficulty in addressing the issue. One significant barrier is the lack of access to healthcare, particularly in underserved communities, where individuals may not have adequate insurance coverage or proximity to healthcare facilities (Allen et al., 2017). This limits their ability to receive essential services such as nutritional counseling, medical advice, or weight management programs (Agurs-Collins et al., 2024). The family environment also plays a crucial role, as unhealthy eating habits and sedentary lifestyles often stem from learned behaviors within the household, making it harder for individuals to adopt healthier habits (Pallarito, 2017). Lastly, challenges within the healthcare system itself, such as a shortage of specialized professionals, insufficient funding for obesity prevention programs, and a focus on acute care rather than long-term management that further hinder efforts to combat obesity effectively.

4.4. Long-Term Consequences

An overweight or obese child has three times the risk for depression in adulthood compared to a normal-weight child (Jacovides et al., 2024; Kanellopoulou et al., 2022). This risk increases to four times for children who are overweight or obese in both childhood and adulthood (Jacovides et al., 2024; Pallarito, 2017). Compounded by social isolation and stigma, discrimination across various contexts can induce loneliness and social withdrawal, heightening the risk for mood disorders (Dandgey & Patten, 2023; Sarwer & Polonsky, 2016). The relationship between obesity and increased instances of anxiety, depression and mood disorder are notably bidirectional (Fulton et al., 2022). Mental health disorders can drive behaviors that foster obesity, and conversely, obesity can escalate the risk of such depressive disorders. The negative influence of obesity on self-esteem and self-efficacy, particularly regarding efforts to lose weight, can undermine motivation and intensify feelings of helplessness. At the same time, the overall quality of life suffers due to the physical limitations, health complications, and emotional distress associated with obesity, diminishing engagement in enjoyable activities and life satisfaction.

5. Discussion

In this article, we reviewed both the causes of childhood obesity, its impact on mental health, and socioeconomic challenges associated with it. Childhood obesity increases the risk of numerous health problems. Children with obesity are more likely to be obese adults, increasing their risk for chronic diseases and mental health issues (Gibson-Smith et al., 2020; Iversen et al., 2024; Kokka et al., 2023; Pallarito, 2017). Although the report indicated that obesity is a hereditary genetic and hormonal disease, dietary habits, sedentary lifestyle, access to healthcare, food access, sleep, and environment also play a role (Fuhrman, 2018; Gohil & Hannon, 2018; Jacovides et al., 2024; Martin, 2014). Weight stigma is a greater concern, negatively impact mental health and potentially discourages people from asking for help (Haqq et al., 2021; Sánchez-Carracedo, 2022; Westbury et al., 2023). Children with obesity may get teased or bullied by their peers, so they lose self-esteem and have higher risk of depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (Craven & Fekete, 2019; Faulconbridge & Bechtel, 2014; Merino et al., 2024; Segal & Gunturu, 2025). These social consequences might cause more difficulty in weight management. Parents of these children should be aware of these behaviors by offering healthy foods. Pears and family play a major role in children’s well-being, and childhood symptoms proceeded further in adolescence. In addition, social withdrawal can aggravate stress and eating disorders like cravings for sweets, high fat, and high sugar junk foods, which could contribute to obesity (Sepúlveda et al., 2022). Children with less sleeping practice are more overweight compared to longer sleep duration. A study in China reported that short sleep duration increased the risks of obesity in children mostly for girls compared to boys at the age 8-13 years (Chen et al., 2022; Han et al., 2022).

Overweight children distance themselves from peers to avoid negative comments, so they have fewer friends than normal weight children which lead to less social interaction and outdoor activities (Sahoo et al., 2015). Consumption of poor nutritional food, high calorie sugar, and easy access to processed food increased over the years and have replaced home-cooked, balanced meals, leading to excessive caloric intake. Childhood obesity has reduced school performance. Obese and overweight children had lower health related quality of life compared to healthy children (Schwimmer et al., 2003). Family physicians, parents, and teachers should get informed of the risk of less health-related quality of life. Psychological stresses such as lack of social support network, unemployed parents, adverse childhood time, and negligence have been associated with childhood obesity at early school age. Childhood obesity is strongly associated with mental health problems. Children and adolescents with increased BMI and standard deviation score showed more behavioral difficulties compared to low BMI (Förster et al., 2023).

Addressing childhood obesity requires a multi-faceted approach. Childhood obesity can be prevented by setting good example of healthy eating, regular family outdoor physical activity, balanced meals and snacks including fruits, vegetables, grains each day, change to new food alternatively, teaching about less eating of junk food, reduce the screen time, encourage child for good sleep, limit portion size, etc. In addition, schools and communities can motivate students for daily exercise, engage in outdoor activities such as running club, biking, and various sporting games. Implementation of healthy behavior, improvement of physical and psychosocial health help to control obesity in children. A variety of behavioral programs such as group activity, therapy sessions, and e-health support are evidenced to control childhood obesity (Jebeile et al., 2022).

6. Conclusion

This present study provides a comprehensive insight into the development of childhood obesity, its causes, consequences and impact on mental health conditions. Childhood obesity is a complex public health challenge with profound physical, psychological, and social consequences. While it increases the risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, metabolic diseases, etc., its impact on mental health is equally significant. Obese children often face stigma, low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety, which can create an environment that reinforces unhealthy behaviors and further weight gain. Recognition of children with psychological vulnerability with obesity could help in early diagnosis. Addressing this problem requires comprehensive prevention and treatment strategies that promote healthy lifestyle changes and create supportive environments.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contribution

E.S. conceived the project. E.S., and P.K.J. designed and wrote the manuscript. The authors approve and take sole responsibility for this article for its integrity.

Institutional Review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The supporting data of the findings of this publication are available within this article.

Acknowledgements

Figures were created using Biorender.com and GraphPad Prism version 10.0. Citation management software Endnote library (version 9) was used to create bibliography.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- C. H. I. S. Overweight and Obesity. CHIS. 2023. Available online: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/our-work/overweight-and-obesity.

- N. R. F. C. Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature 2019, 569(7755), 260–264. [CrossRef]

- Agurs-Collins, T.; Alvidrez, J.; ElShourbagy Ferreira, S.; Evans, M.; Gibbs, K.; Kowtha, B.; Pratt, C.; Reedy, J.; Shams-White, M.; Brown, A. G. Perspective: Nutrition Health Disparities Framework: A Model to Advance Health Equity. Adv Nutr 2024, 15(4), 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajele, K. W.; Ramadie, K. J.; Idemudia, E. S.; Ugwu, L. E. Mental health among high school students in South Africa: Roles of childhood adversity, bullying behaviour, peer pressure, and self-esteem. Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 34(6), 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E. M.; Call, K. T.; Beebe, T. J.; McAlpine, D. D.; Johnson, P. J. Barriers to Care and Health Care Utilization Among the Publicly Insured. Med Care 2017, 55(3), 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, G. X.; Monge-Rojas, R.; King, A. C.; Hunter, R.; Berge, J. M. The social environment and childhood obesity: Implications for research and practice in the United States and countries in Latin America. Obes Rev 2021, 22 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), e13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakour, C.; Mansuri, F.; Johns-Rejano, C.; Crozier, M.; Wilson, R.; Sappenfield, W. Association between screen time and obesity in US adolescents: A cross-sectional analysis using National Survey of Children’s Health 2016-2017. PLoS ONE 2022, 17(12), e0278490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, S.; Harnois-Leblanc, S.; Béland, M.; Simoneau, G.; Mathieu, M.-È.; Barnett, T. A.; Sabiston, C. M.; Henderson, M. The association between depressive symptoms and overweight or obesity in prepubertal children: Findings from the QUALITY cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders 2024, 367, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K.; Hammami, N.; Katapally, T. R. Is excessive smartphone use associated with weight status and self-rated health among youth? A smart platform study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23(1), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Flint, S. W.; Batterham, R. L. Pervasiveness, impact and implications of weight stigma. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 47, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. K. Biological, environmental, and social influences on childhood obesity. Pediatr Res 2016, 79(1-2), 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Adult obesity prevalence Maps. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data-and-statistics/adult-obesity-prevalence-maps.html.

- CDC. Managing obesity on schools . In Center of Disease Control (CDC); 2024, July 8, 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/school-health-conditions/chronic/obesity.html.

- Center, C. p. R. California State Fact Sheet. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. Retrieved 07/09/2025. 2008. Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/docs/nsch-docs/california-pdf.pdf#:~:text=The%20California%20prevalence%20of%20overweight%20and%20obese,2%2D5%20are%20overweight%20or%20obese%20in%20California.

- Chaabene, H.; Markov, A.; Schega, L. Why should the Next Generation of Youth Guidelines Prioritize Vigorous Physical Activity? Sports Med Open 2024, 10(1), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L. J.; Xin, F.; Liang, G.; Chen, Y. Associations between sleep duration, sleep quality, and weight status in Chinese children and adolescents. BMC Public Health 2022, 22(1), 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Kaminga, A. C.; Liu, Q.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Association between weight status and bullying experiences among children and adolescents in schools: An updated meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect 2022, 134, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee, A. P. E. The Impact of Obesity on Your Body and Health . 2021. Available online: https://asmbs.org/patients/impact-of-obesity/.

- Craven, M. P.; Fekete, E. M. Weight-related shame and guilt, intuitive eating, and binge eating in female college students. Eating Behaviors 2019, 33, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S. K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G. K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The Association of Emotional Eating with Overweight/Obesity, Depression, Anxiety/Stress, and Dietary Patterns: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandgey, S.; Patten, E. Psychological considerations for the holistic management of obesity. Clin Med (Lond) 2023, 23(4), 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, B. J.; Huffman, M. D.; Binns, H.; Stone, N. J. Perspective: Childhood Obesity Requires New Strategies for Prevention. Advances in Nutrition 2020, 11(5), 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zein, A.; Colby, S. E.; Zhou, W.; Shelnutt, K. P.; Greene, G. W.; Horacek, T. M.; Olfert, M. D.; Mathews, A. E. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Increased Risk of Obesity in US College Students. Current Developments in Nutrition 2020, 4(8), nzaa120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Elizabeth A. B.; Rudowitz, Robin. The National Survey of Children’s Health. Medicaid KFF. 2023. Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/obesity-rates-among-children-a-closer-look-at-implications-for-children-covered-by-medicaid/#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20share%20of,income%20households%20(Figure%201).

- Engberg, E.; Figueiredo, R. A. O.; Rounge, T. B.; Weiderpass, E.; Viljakainen, H. Heavy screen users are the heaviest among 10,000 children. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1), 11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Mu, M.; Liu, K.; He, Y. Screen time and childhood overweight/obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child: Care, Health and Development 2019, 45(5), 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulconbridge, L. F.; Bechtel, C. F. Depression and Disordered Eating in the Obese Person. Curr Obes Rep 2014, 3(1), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feter, N.; Leite, J. S.; Weymar, M. K.; Dumith, S. C.; Umpierre, D.; Caputo, E. L. Physical activity during early life and the risk of all-cause mortality in midlife: findings from a birth cohort study. Eur J Public Health 2023, 33(5), 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, L.; Vogel, M.; Stein, R.; Hilbert, A.; Breinker, J.; Böttcher, M.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Mental health in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. BMC Public Health 2023, 23(1), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayn, M.; Livshits, S.; Knäuper, B. Emotional eating and weight regulation: a qualitative study of compensatory behaviors and concerns. J Eat Disord 2018, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, C. B.; Snellman, K.; Putnam, R. D. Increasing socioeconomic disparities in adolescent obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111(4), 1338–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, J. The Hidden Dangers of Fast and Processed Food. Am J Lifestyle Med 2018, 12(5), 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, S.; Décarie-Spain, L.; Fioramonti, X.; Guiard, B.; Nakajima, S. The menace of obesity to depression and anxiety prevalence. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2022, 33(1), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajalakshmi, G.; Meenakshi, S. Understanding the psycho-social problems of vulnerable adolescent girls and effect of intervention through life skill training. J Educ Health Promot 2023, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403(10440), 2162–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson-Smith, D.; Halldorsson, T. I.; Bot, M.; Brouwer, I. A.; Visser, M.; Thorsdottir, I.; Birgisdottir, B. E.; Gudnason, V.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Launer, L. J.; Harris, T. B.; Gunnarsdottir, I. Childhood overweight and obesity and the risk of depression across the lifespan. BMC Pediatr 2020, 20(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, K. Five or More Hours of Smartphone Usage Per Day May Increase Obesity . American College of Cardiology. 2019. Available online: https://www.acc.org/about-acc/press-releases/2019/07/25/14/23/five-or-more-hours-of-smartphone-usage-per-day-may-increase-obesity.

- Gohil, A.; Hannon, T. S. Poor Sleep and Obesity: Concurrent Epidemics in Adolescent Youth [Review]. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2018, 9–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grao-Cruces, A.; Velásquez-Romero, M. J.; Rodriguez-Rodríguez, F. Levels of Physical Activity during School Hours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Chen, X.; Howland, S.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gauderman, W. J.; McConnell, R.; Pavlovic, N.; Lurmann, F.; Bastain, T. M.; Habre, R.; Breton, C. V.; Farzan, S. F. Childhood Exposure to Air Pollution, Body Mass Index Trajectories, and Insulin Resistance Among Young Adults. JAMA Network Open 2025, 8(4), e256431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurka, M. J.; Filipp, S. L.; DeBoer, M. D. Geographical variation in the prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes among US adults. Nutr Diabetes 2018, 8(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. H.; Yee, J. Y.; Pyo, J. S. Impact of Short Sleep Duration on the Incidence of Obesity and Overweight among Children and Adolescents. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haqq, A. M.; Kebbe, M.; Tan, Q.; Manco, M.; Salas, X. R. Complexity and Stigma of Pediatric Obesity. Child Obes 2021, 17(4), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D. C.; Reesor, L.; Murillo, R. Gender Disparities in the Food Insecurity-Overweight and Food Insecurity-Obesity Paradox among Low-Income Older Adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2017a, 117(7), 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D. C.; Reesor, L. M.; Murillo, R. Food insecurity and adult overweight/obesity: Gender and race/ethnic disparities. Appetite 2017b, 117, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital, U. B. C. s. Childhood Obesity and Screen Time . UCSF Benioff Childre’s Hospital. 2025. Available online: https://www.ucsfbenioffchildrens.org/education/childhood-obesity-and-screen-time.

- Iacopetta, D.; Catalano, A.; Ceramella, J.; Pellegrino, M.; Marra, M.; Scali, E.; Sinicropi, M. S.; Aquaro, S. The Ongoing Impact of COVID-19 on Pediatric Obesity. Pediatr Rep 2024, 16(1), 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, K. D.; Pedersen, T. P.; Rasmussen, M.; Hansen, M. L.; Roikjer, B. H.; Teilmann, G. Mental health and BMI in children and adolescents during one year in obesity treatment. BMC Pediatr 2024, 24(1), 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacovides, C.; Pritsa, A.; Chrysafi, M.; Papadopoulou, S. K.; Kapetanou, M. G.; Lechouritis, E.; Mato, M.; Papadopoulou, V. G.; Tsourouflis, G.; Migdanis, A.; Sampani, A.; Kosti, R. I.; Psara, E.; Giaginis, C. Childhood Mediterranean Diet Compliance Is Associated with Lower Incidence of Childhood Obesity, Specific Sociodemographic, and Lifestyle Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study in Children Aged 6-9 Years. Pediatr Rep 2024, 16(4), 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A. S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L. A. Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2022, 10(5), 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Dai, S.; Rohli, K. E.; Rohli, R. V.; Ma, Y.; Yu, C.; Pan, X.; Zhou, W. Natural environment and childhood obesity: A systematic review. Obes Rev 2021, 22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), e13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, Julian; Duncan. Children, video games and physical activity: An exploratory study. International Journal on Disability and Human Development 2008, 7(1), 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulou, A.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Douros, K.; Panagiotakos, D. B. The Association between Obesity and Depression among Children and the Role of Family: A Systematic Review. Children (Basel) 2022, 9(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, E. L.; Gortmaker, S. L. United States Adolescents’ Television, Computer, Videogame, Smartphone, and Tablet Use: Associations with Sugary Drinks, Sleep, Physical Activity, and Obesity. J Pediatr 2017, 182, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, J.; Burnett, D.; Babu, J. R.; Geetha, T. The Effects of Food Environment on Obesity in Children: A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10(1), 98. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/10/1/98. [CrossRef]

- KidsData. Students Who Are Overweight or Obese, by Race/Ethnicity and Grade Level . www.kidsdata.org. 2019. Available online: https://www.kidsdata.org/topic/727/overweight-race/.

- Kokka, I.; Mourikis, I.; Bacopoulou, F. Psychiatric Disorders and Obesity in Childhood and Adolescence-A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies. Children (Basel) 2023, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnes, K. J.; Petersen, M. H.; Lien-Iversen, T.; Højlund, K.; Jensen, J. Effect of Exercise Training on Fat Loss-Energetic Perspectives and the Role of Improved Adipose Tissue Function and Body Fat Distribution. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 737709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Cardel, M.; Donahoo, W. T. Social and Environmental Factors Influencing Obesity. In Endotext; Feingold, K. R., Ahmed, S. F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M. R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W. W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J., Kalra, S., Kaltsas, G., Kapoor, N., Koch, C., Kopp, P., Korbonits, M., Kovacs, C. S., Kuohung, W., Laferrère, B., Levy, M., McGee, E. A., McLachlan, R., Muzumdar, R., Purnell, J., Rey, R., Sahay, R., Shah, A. S., Singer, F., Sperling, M. A., Stratakis, C. A., Trence, D. L., Wilson, D. P., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000-2025, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, A. C.; Sussner, K. M.; Kim, J.; Gortmaker, S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child 2006, 16(1), 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobstein, T.; Brinsden, H. Atlas of childhood obesity. World Obesity Federation 2019, 211, 486. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.; Saunders, DH; Shenkin, SD; Sproule, J. Lifestyle intervention for improving schoolachievement in overweight or obese children and adolescents’ . In Cochrane database of systematic reviews; 2014; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. A.; Lippert, A. M. Feeding her children, but risking her health: The intersection of gender, household food insecurity and obesity. Social Science & Medicine 2012, 74(11), 1754–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, R.; Shen, E.; Gilliland, F. D.; Jerrett, M.; Wolch, J.; Chang, C. C.; Lurmann, F.; Berhane, K. A longitudinal cohort study of body mass index and childhood exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and air pollution: the Southern California Children’s Health Study. Environ Health Perspect 2015, 123(4), 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S.; Wani, S. U. D.; Krishna, K. L.; Kinattingal, N.; Roohi, T. F. A review on linking stress, depression, and insulin resistance via low-grade chronic inflammation. Biochem Biophys Rep 2023, 36, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.; Tornero-Aguilera, J. F.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Villanueva-Tobaldo, C. V.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Clemente-Suárez, V. J. Body Perceptions and Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Impact of Social Media and Physical Measurements on Self-Esteem and Mental Health with a Focus on Body Image Satisfaction and Its Relationship with Cultural and Gender Factors. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ver Ploeg, Michele V.B.; Farrigan, Tracey; Hamrick, Karen; Hopkins, David; Lin, Biing-Hwan; Nord, Mark; Smith, Travis A.; Williams, Ryan; Kinnison, Kelly; Olander, Carol; Singh, Anita; Tuckermanty, Elizabeth. Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food-Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences: Report to Congress . In USDA Economic Research Service; 2009. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details?pubid=42729.

- Myers, C. A.; Slack, T.; Martin, C. K.; Broyles, S. T.; Heymsfield, S. B. Regional disparities in obesity prevalence in the United States: A spatial regime analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015, 23(2), 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, L.; Sides, N.; Rashidi, A. The psychosocial beliefs, experiences and expectations of children living with obesity. Health Expect 2024, 27(1), e13973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C. The pandemic made childhood obesity even worse. How can we help the children most at risk? USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism. 2023. Available online: https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/our-work/insights/pandemic-made-childhood-obesity-even-worse-how-can-we-help-children-most-risk.

- Odoms-Young, A.; Brown, A. G. M.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Glanz, K. Food Insecurity, Neighborhood Food Environment, and Health Disparities: State of the Science, Research Gaps and Opportunities. Am J Clin Nutr 2024, 119(3), 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarito, K. Overweight kids face higher risk for depression as adults . CBS NEW. 2017. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/overweight-obese-children-higher-risk-depression-as-adults/.

- Phelps, N. H.; Singleton, R. K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R. A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J. E.; Paciorek, C. J.; Lhoste, V. P. F.; Carrillo-Larco, R. M.; Stevens, G. A.; Rodriguez-Martinez, A.; Bixby, H.; Bentham, J.; Di Cesare, M.; Danaei, G.; Rayner, A. W.; Barradas-Pires, A.; Cowan, M. J.; Savin, S.; Ezzati, M. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 2024, 403(10431), 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, M. V. Access to Affordable, Nutritious Food Is Limited in “Food Deserts” . In USDA Economic Research Service; 2010. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2010/march/access-to-affordable-nutritious-food-is-limited-in-food-deserts.

- Pont, S. J.; Puhl, R.; Cook, S. R.; Slusser, W.; OBESITY, S. O.; SOCIETY, T. O. Stigma Experienced by Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics 2017, 140(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porri, D.; Morabito, L. A.; Cavallaro, P.; La Rosa, E.; Li Pomi, A.; Pepe, G.; Wasniewska, M. Time to act on childhood obesity: the use of technology. Front Pediatr 2024, 12, 1359484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J.; Matthews, L.; Cobley, S.; Han, A.; Sanders, R.; Wiltshire, H. D.; Baker, J. S. Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2016, 7, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, E.; Patel, P.; Babu, J. R.; Wang, X.; Geetha, T. The Importance of Sleep in Overcoming Childhood Obesity and Reshaping Epigenetics. Biomedicines 2024, 12(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T. N.; Banda, J. A.; Hale, L.; Lu, A. S.; Fleming-Milici, F.; Calvert, S. L.; Wartella, E. Screen Media Exposure and Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2017, 140 Suppl 2, S97–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A. K.; Sofi, N. Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A. S. Childhood obesity: causes and consequences. J Family Med Prim Care 2015, 4(2), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Ba-Break, M.; Abahussin, A. Barriers and facilitators of school-based obesity prevention interventions: a qualitative study from the perspectives of primary school headteachers. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 2024, 43(1), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Obesity stigma and its impact on health: A narrative review. Endocrinología, Diabetes y Nutrición (English ed.) 2022, 69(10), 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Qi, X.; Locke, J.; Rehman, S. Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in the United States: A Public Health Concern. Glob Pediatr Health 2019, 6, 2333794x19891305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D. B.; Polonsky, H. M. The Psychosocial Burden of Obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2016, 45(3), 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwimmer, J. B.; Burwinkle, T. M.; Varni, J. W. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. Jama 2003, 289(14), 1813–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, Y.; Gunturu, S. Psychological Issues Associated With Obesity. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda, A. R.; Lacruz, T.; Solano, S.; Rojo, M.; Román, F. J.; Blanco, M. Using structural equation modeling to understand family and psychological factors of childhood obesity: from socioeconomic disadvantage to loss of control eating. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2022, 27(5), 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shook, R. P.; Hand, G. A.; Drenowatz, C.; Hebert, J. R.; Paluch, A. E.; Blundell, J. E.; Hill, J. O.; Katzmarzyk, P. T.; Church, T. S.; Blair, S. N. Low levels of physical activity are associated with dysregulation of energy intake and fat mass gain over 1 year12. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015, 102(6), 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutaria, S.; Devakumar, D.; Yasuda, S. S.; Das, S.; Saxena, S. Is obesity associated with depression in children? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 2019, 104(1), 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomayko, E. J.; Tovar, A.; Fitzgerald, N.; Howe, C. L.; Hingle, M. D.; Murphy, M. P.; Muzaffar, H.; Going, S. B.; Hubbs-Tait, L. Parent Involvement in Diet or Physical Activity Interventions to Treat or Prevent Childhood Obesity: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2021, 13(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Ball, K. Individual, social and physical environmental correlates of children’s active free-play: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbury, S.; Oyebode, O.; van Rens, T.; Barber, T. M. Obesity Stigma: Causes, Consequences, and Potential Solutions. Curr Obes Rep 2023, 12(1), 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. Challenging energy balance - during sensitivity to food reward and modulatory factors implying a risk for overweight - during body weight management including dietary restraint and medium-high protein diets. Physiology & Behavior 2020, 221, 112879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. 2012, 27 February 2013. Available online: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

- Yiting, E.; Yang, J.; Shen, Y.; Quan, X. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Academic Burden: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Health among Chinese Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).