Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

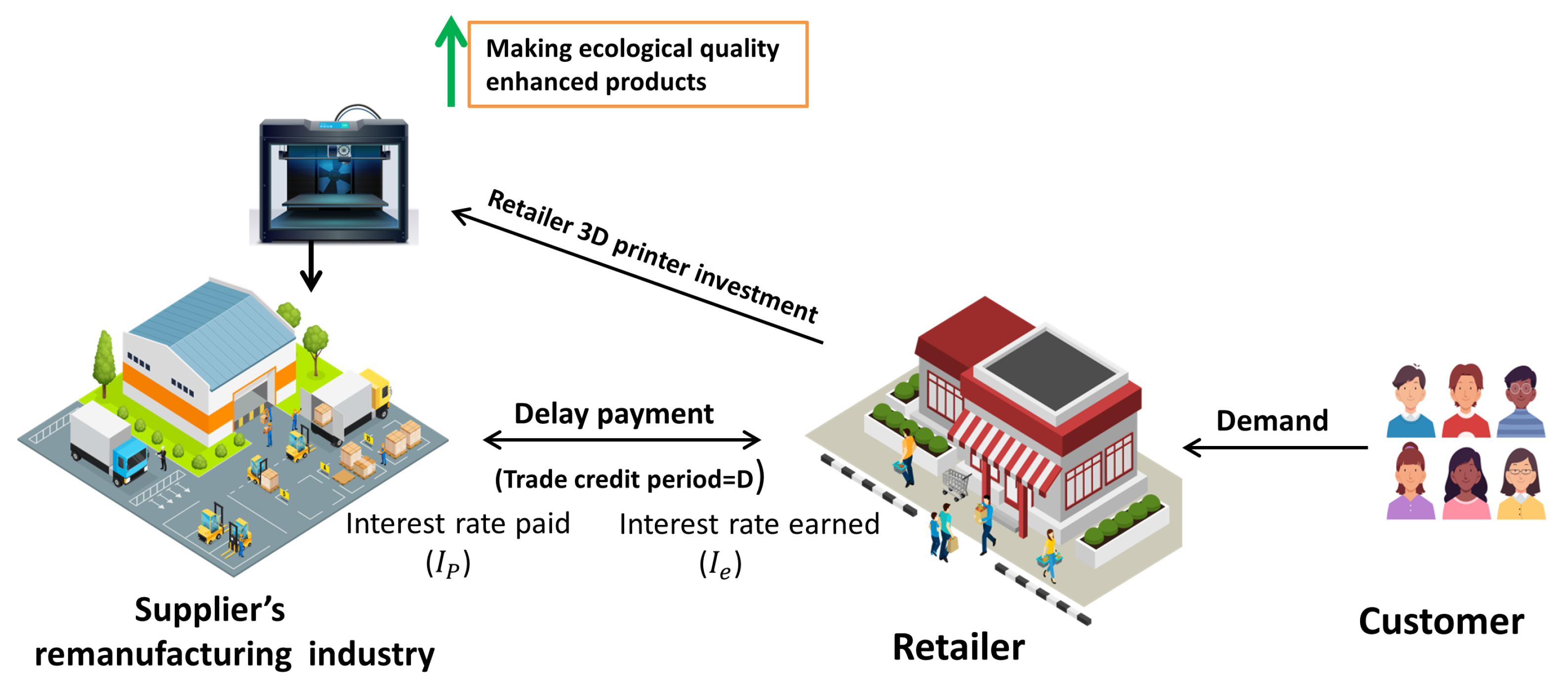

1. Introduction

- Need to answer approaches to improve the quality of recycled products using additive manufacturing technology.

- How can a sustainable recycled inventory system be created through the use of AM technology?

- Analysis on investment from retailers in 3D printers can support the production of recycled products.

- How can the reliability of recycled plastic products be ensured while maximizing overall profit?

2. Literature Review

- To develop a sustainable EOQ model integrating AM (3D printing) for eco-friendly inventory management.

- o enhance product quality and reliability while utilizing recycled plastic materials in production.

- To evaluate the economic and environmental benefits of adopting 3D printing technology in retailer operations.

- Introduce the additive manufacturing technology investments to increase the quality, reliability, and profitability of recycled products.

- A sustainable inventory model using AM technology for emission reduction and waste minimization to enhance the quality of recycled plastic products.

| Reference |

Sustainable |

EOQ |

Price dependent demand |

Time dependent demand |

Quality dependent demand |

Reliability dependent demand |

AM Technology or 3D printing technology |

Delay payment |

| [41] | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [42] | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| [43] | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| [44] | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| [45] | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [46] | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| [47] | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [48] | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| [49] | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| [51] | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [52] | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| [53] | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ |

| [54] | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| [55] | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| [56] | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ |

| [57] | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [58] | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| [59] | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| [60] | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| This paper | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

3. Development of Sustainable Inventory System

- The demand rate for this model which depends on the price, reliability and quality and increases with time i.e., , here a is initial demand.

- Degradation initiates immediately upon lot reception, and its rate remains constant at deterioration rate denoted by .

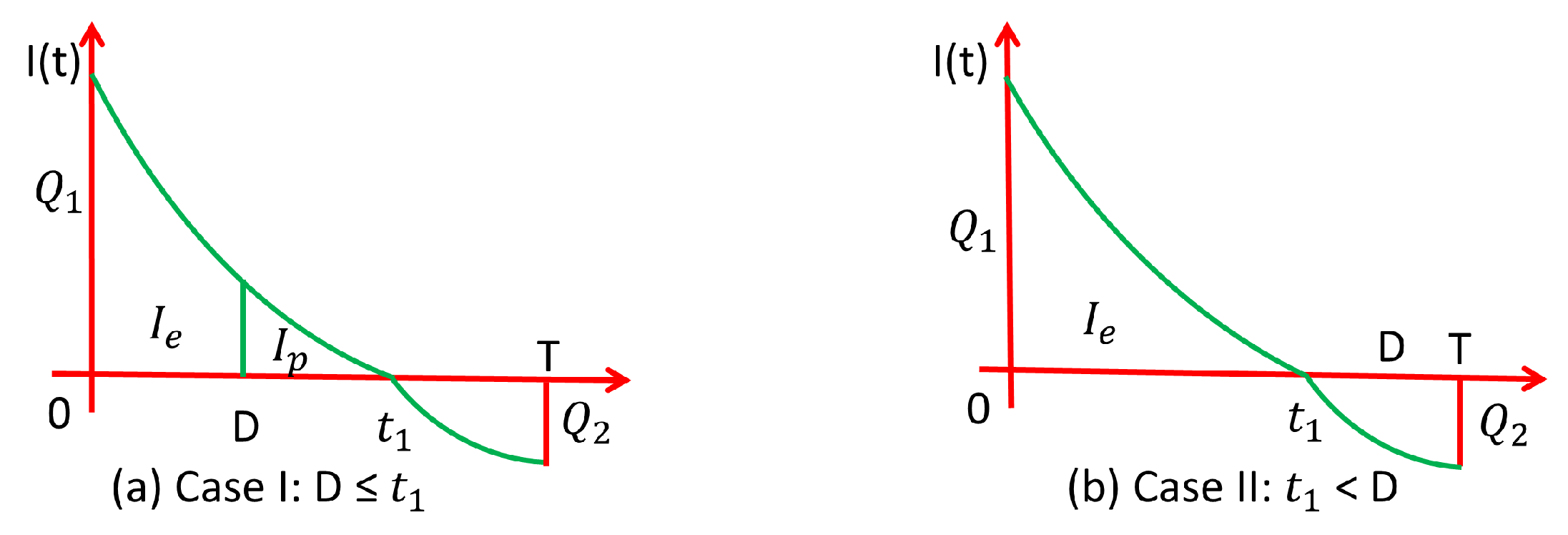

- If the retailer settles the payment within the designated credit period D provided by the supplier, they will avoid any interest fees. Conversely, if the retailer makes the payment after the the credit term D, they will incur interest at the rate .

-

In case-I: When the stock duration is consistently positive and exceeds the credit term D (i.e., ). The consumer seeks to generate interest at an annual rate of . This situation arises when the credit duration D exceeds the duration of the stock. Using the sales revenue, calculate . After the credit period concludes, the unsold inventory will be financed at an annual rate of once the credit time has expired.Case-II: If the amount D equals or exceeds the allowable payment delay (i.e, ), the consumer is excused from paying interest and instead accumulates interest at a constant yearly rate within the range (0, D). This occurs if D is greater than , which indicates that D exceeds the allowable payment delay.

- The rate at which this model is in demand relies on product reliability, expressed as . The reliability of products offered by the retailer is influenced by the quality of goods provided by the manufacturer.

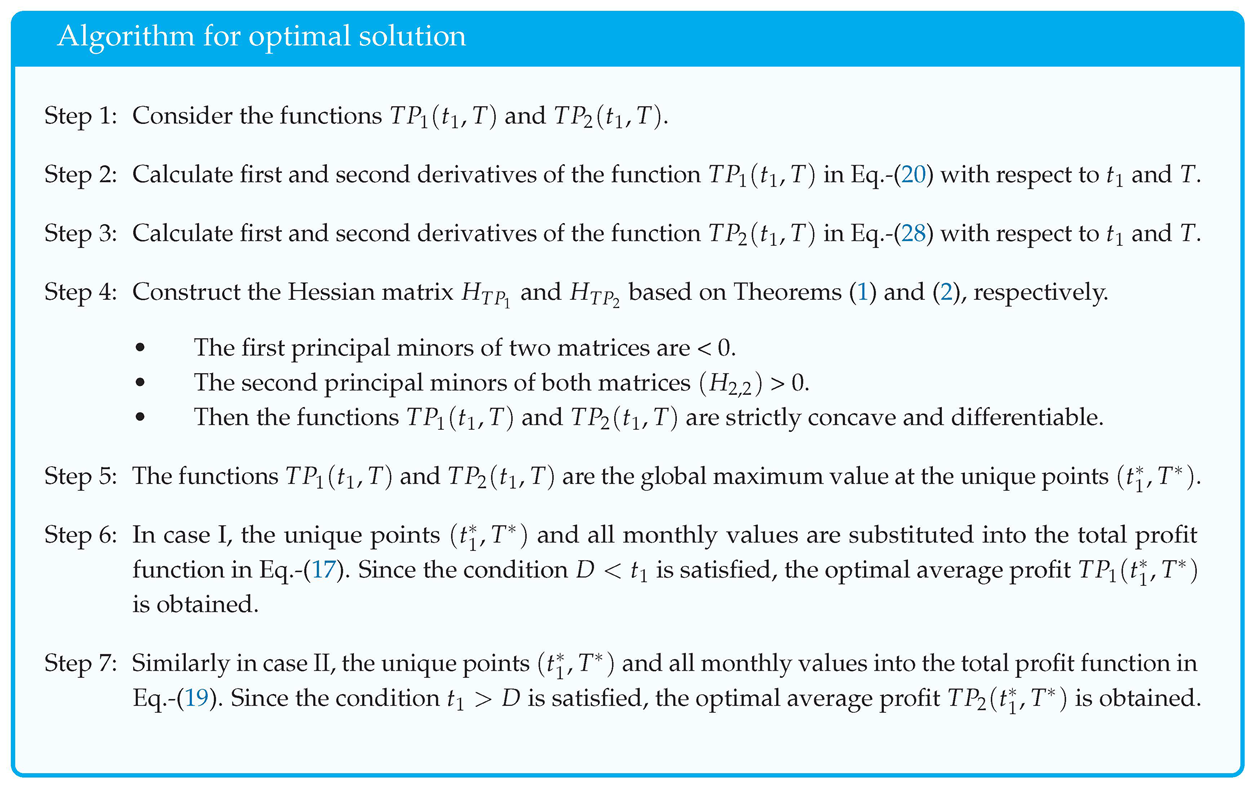

- Quality of items in the inventory system is i.e of quality item’s present in the inventory. Here is the amount of recycling products when 3D technology is investmented, and e is the efficiency of 3D technology in recycling products. The quality q = 0, when A = 0, and tends to when . The cost function of investment, q(A) is possesses continuous derivatives

4. Derivation of Costs of Inventory System

Delay Based Payment Frameworks

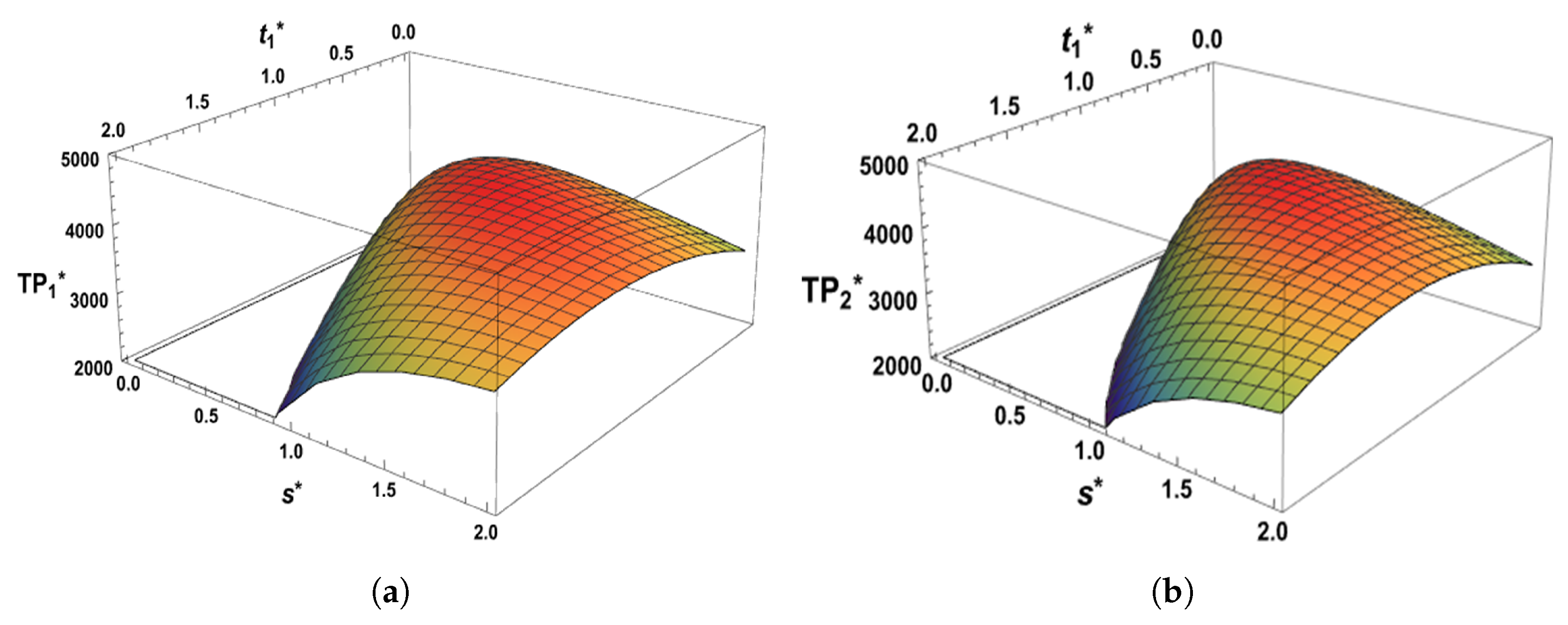

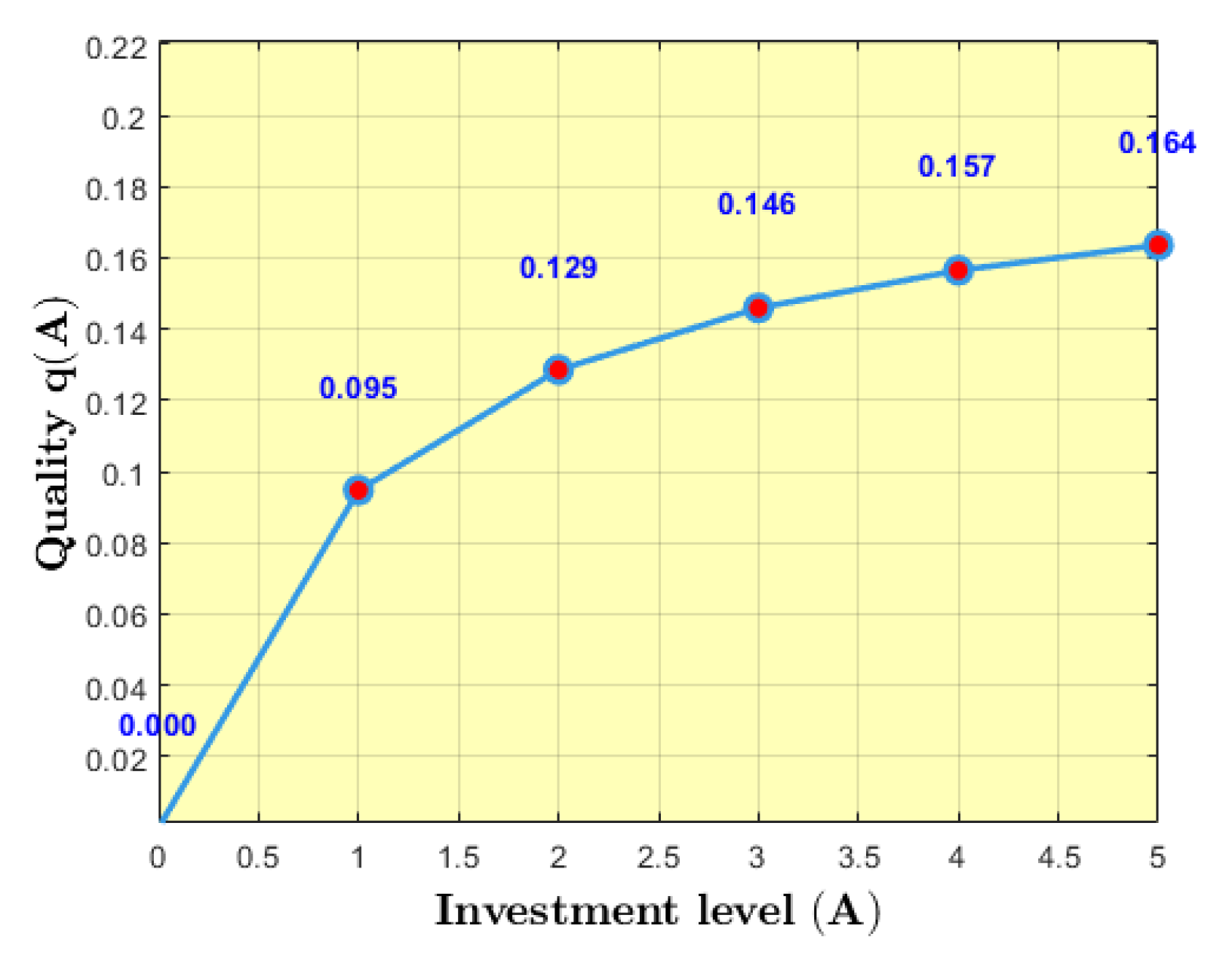

5. Methodology

6. Numerical Illustration

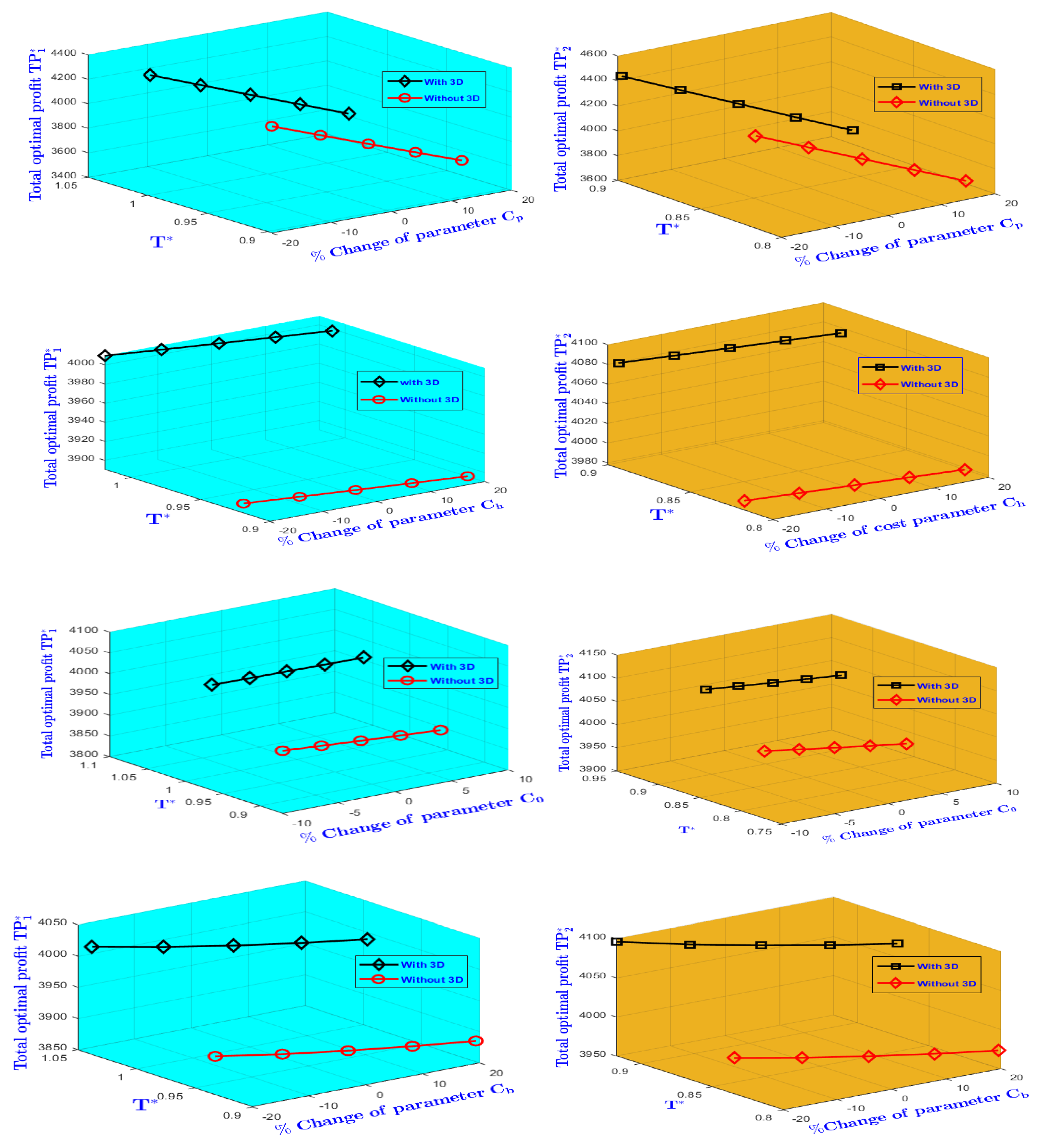

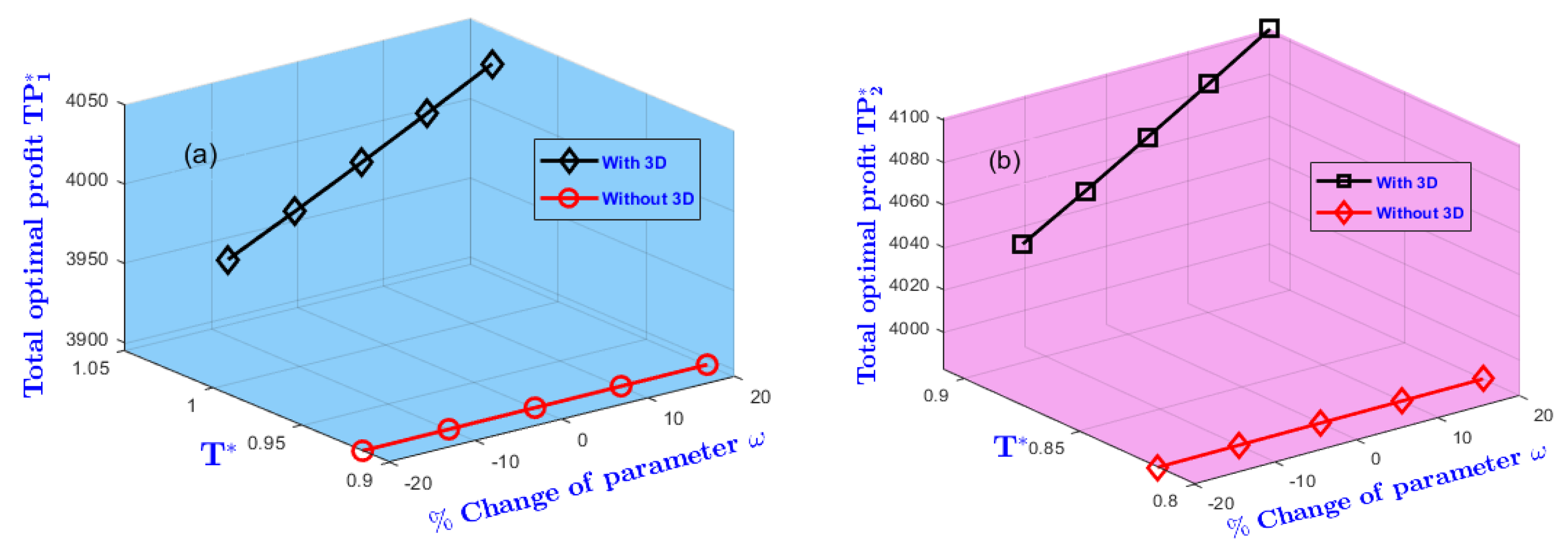

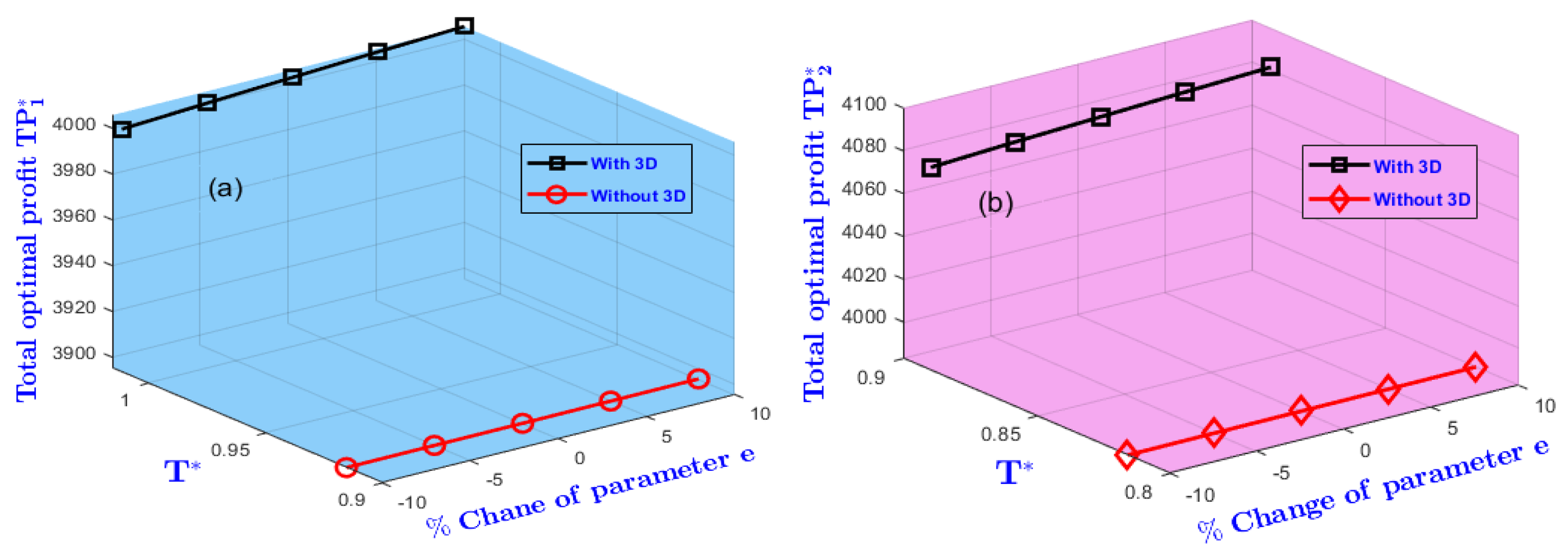

7. Sensitivity Analysis

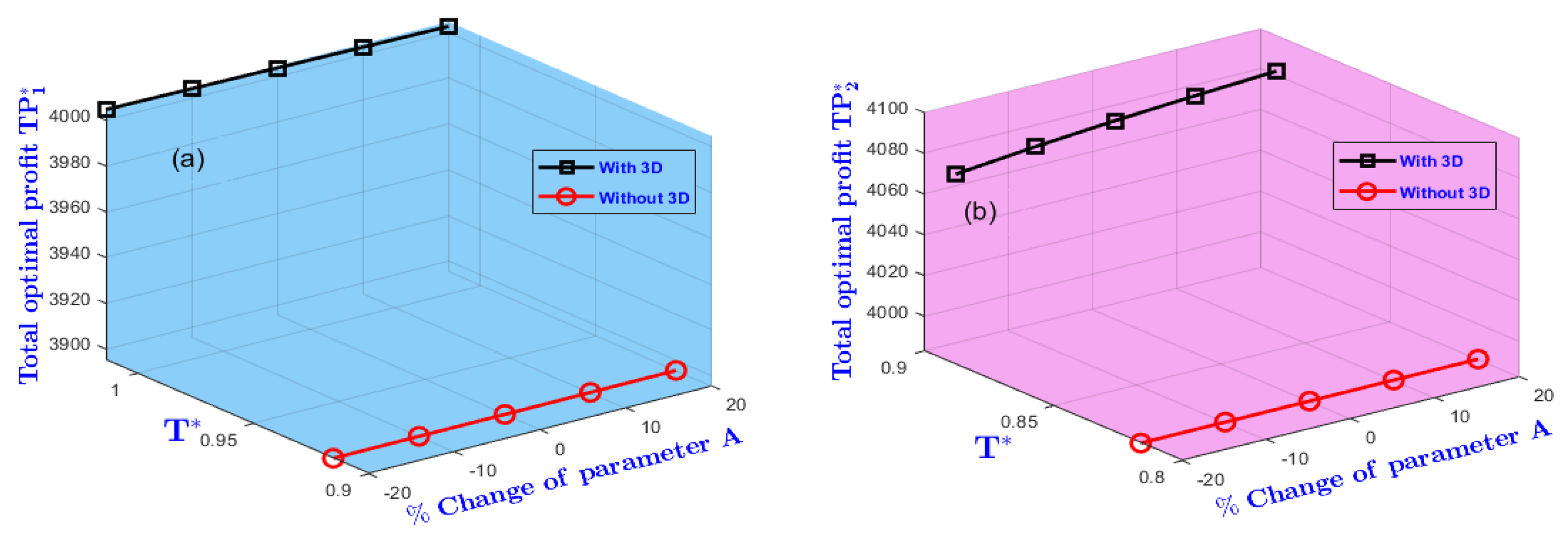

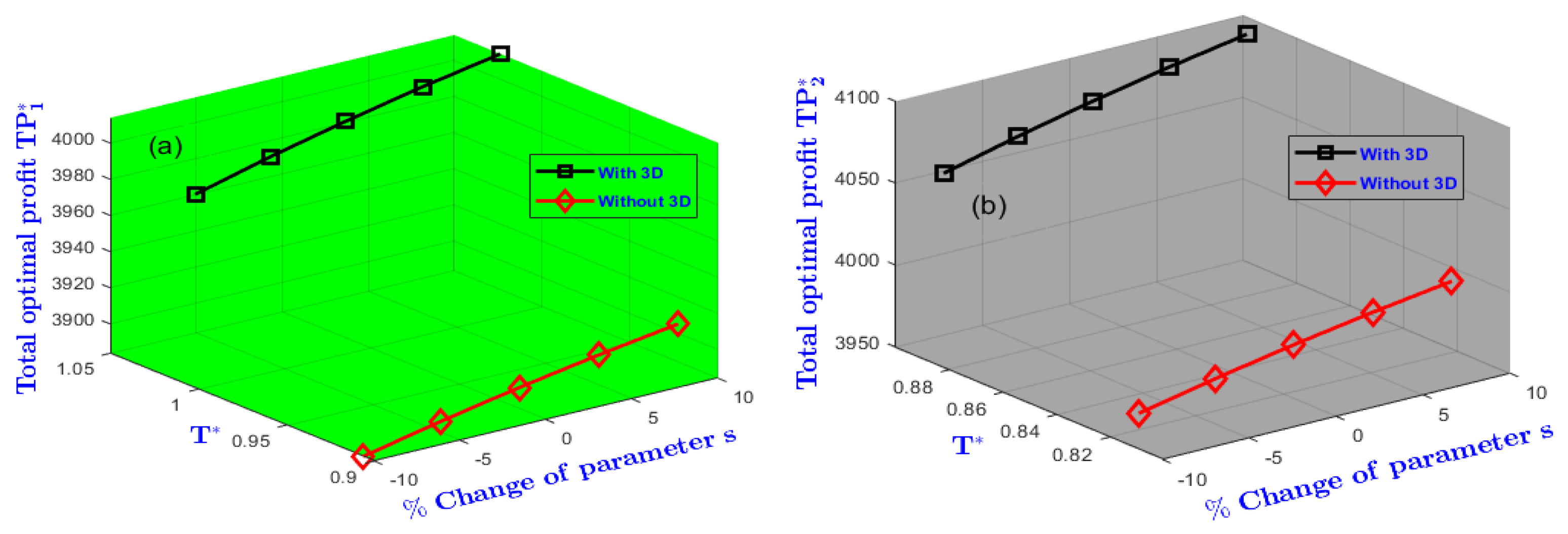

- Efficient investment in AM technology enhances product quality and overall profitability. Adoption of advanced technological solutions not only strengthens manufacturing capability but also supports environmentally sustainable practices.

- Managers should maintain a balance between pricing and demand to sustain profitability. Excessively high prices may suppress demand; hence, competitive pricing combined with focused promotional strategies can stimulate sales. Furthermore, optimizing order quantities and inventory cycles enhances operational efficiency and long-term financial performance.

- Improving product quality enhances reliability, contributing to higher profitability. Manufacturers should prioritize robust quality control and continuous process improvement to ensure consistent performance, operational efficiency, and customer satisfaction.

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameters | |

| s | Supplier’s quality products. |

| Annual interest rate earned. | |

| Annual interest rate charged. | |

| D | Supplier-to-retailer-set credit period. |

| Deterioration rate. | |

| p | The price at which the item is sold.($/unit). |

| A | AM technology investment cost to increase quality ($/year). |

| e | Efficiency of the AM technology in recycling products. |

| Amount of recycling products after 3d technology investment(ton/unit/year). | |

| r | Reliability of the products. |

| q | Fraction of quality items present in the inventory. |

| Decision variables | |

| The time at the reaching point of zero inventory level. | |

| T | Cycle length (unit of time). |

References

- Ashok, D.; Raju Bahubalendruni, M.; Johnney Mertens, A.; Balamurali, G. A novel nature inspired 3D open lattice structure for specific energy absorption. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part E: Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering 2022, 236, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, F.; Taylor, R. Additive Manufacturing in the Context of Repeatability and Reliability. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2023, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour Pour, M.; Zanoni, S.; Bacchetti, A.; Zanardini, M.; Perona, M. Additive manufacturing impacts on a two-level supply chain. International Journal of Systems Science: Operations and Logistics 2019, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; De, S.K. A pollution sensitive fuzzy EPQ model with endogenous reliability and product deterioration based on lock fuzzy game theoretic approach. Soft Computing 2023, 27, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhari, W.; Pujawan, I.; Suef, M.; Govindan, K. Low carbon inventory model for vendor‒buyer system with hybrid production and adjustable production rate under stochastic demand. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2022, 108, 840–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; He, Y.; Li, D. Coordination of pricing, inventory, and production reliability decisions in deteriorating product supply chains. International Journal of Production Research 2018, 56, 6201–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslah, B.; Gharbi, A.; Pellerin, R. Joint economic design of production, continuous sampling inspection and preventive maintenance of a deteriorating production system. International Journal of Production Economics 2016, 173, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehayem Nodem, F.; Kenné, J.; Gharbi, A. Simultaneous control of production, repair/replacement and preventive maintenance of deteriorating manufacturing systems. International Journal of Production Economics 2011, 134, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Gomez, H.; Gharbi, A.; Kenné, J.P. Joint control of production, overhaul, and preventive maintenance for a production system subject to quality and reliability deteriorations. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2013, 69, 2111–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchhait, P.; Kumar Maiti, M.; Maiti, M. Production-inventory models for a damageable item with variable demands and inventory costs in an imperfect production process. International Journal of Production Economics 2013, 144, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikur Rahman, M.; Al-Amin Khan, M.; Abdul Halim, M.; Nofal, T.A.; Akbar Shaikh, A.; Mahmoud, E.E. Hybrid price and stock dependent inventory model for perishable goods with advance payment related discount facilities under preservation technology. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2021, 60, 3455–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Das, S.; Zidan, A.; Manna, A.K.; Shaikh, A.A.; Bhunia, A.K. An application of preservation technology in inventory control system with price dependent demand and partial backlogging. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2020, 59, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.B.; Yu, J.C.P.; Chen, J.M. Optimizing a Sustainable Inventory Model Under Limited Recovery Rates and Demand Sensitivity to Price, Carbon Emissions, and Stock Conditions. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. Optimal Strategies for Interval Economic Order Quantity (IEOQ) Model with Hybrid Price-Dependent Demand via CU Optimization Technique. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Rahaman, M.; Alam, S.; Pervin, M.; Salahshour, S.; Mondal, S.P. An Inventory Model with Price-, Time-and Greenness-Sensitive Demand and Trade Credit-Based Economic Communications. Logistics 2025, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Mashud, A.H.; Hasan, M.; Wee, H.M.; Daryanto, Y. Non-instantaneous deteriorating inventory model under the joined effect of trade-credit, preservation technology and advertisement policy. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 1645–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, F.; Tang, W. Optimal pricing on an age-specific inventory system for perishable items. Operational Research 2020, 20, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuniya, S.; Guchhait, R.; Ganguly, B.; Pareek, S.; Sarkar, B.; Sarkar, M. An application of a smart production system to control deteriorated inventory. RAIRO - Operations Research 2023, 57, 2435–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Hakim, M.; Hezam, I.M.; Alrasheedi, A.F.; Gwak, J. Pricing policy in an inventory model with green level dependent demand for a deteriorating item. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.S.; Kumar, D.; Prasad, K. Two warehouse dispatching policies for perishable items with freshness efforts, inflationary conditions and partial backlogging. Operations Management Research 2022, 15, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.N.B.; Kim, H.S.; Cuong, T.N.; You, S.S. Intelligent decision support system for optimizing inventory management under stochastic events. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 23675–23697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.H.; Rabari, K.; Patel, E. ECONOMIC PRODUCTION MODEL WITH RELIABILITY AND INFLATION FOR DETERIORATING ITEMS UNDER CREDIT FINANCING WHEN DEMAND DEPENDS ON STOCK DISPLAYED. Investigacion Operacional 2022, 43, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Alamri, O.A. Sustainable supply chain model for defective growing items (fishery) with trade credit policy and fuzzy learning effect. Axioms 2023, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E.; Manna, A.K.; Céspedes-Mota, A.; Treviño-Garza, G. Two level trade credit policy approach in inventory model with expiration rate and stock dependent demand under nonzero inventory and partial backlogged shortages. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.L.; Lee, S.F.; Kuo, W.L.; Liao, J.J. Retailer’s Lot-sizing Decisions with Imperfect Quality and Capacity Constraint under Generalized Payments in Three-level Supply Chain. International Journal of Information and Management Sciences 2023, 34, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Jayaswal, M.K.; Kumar, V. Effect of learning on the optimal ordering policy of inventory model for deteriorating items with shortages and trade-credit financing. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management 2022, 13, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-José, L.A.; Sicilia, J.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E.; de-la Rosa, M.G. A sustainable inventory model for deteriorating items with power demand and full backlogging under a carbon emission tax. International Journal of Production Economics 2024, 268, 109098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Yang, Y. Greenhouse Gas Emission Analysis of Integrated Production-Inventory- Transportation Supply Chain Enabled by Additive Manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, Transactions of the ASME 2022, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.; Yang, Y.; Lee, W.J.; Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, F. Reusable unit process life cycle inventory for manufacturing: stereolithography. Production Engineering 2019, 13, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.; Kuzmenko, K.; Roussel, N.; Mesnil, R.; Feraille, A. Life cycle assessment of a concrete 3D printing process. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2023, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozkhosh, P.; Pooya, A.; Soleimani Fard, O.; Bagheri, R. Revolutionizing supply chain sustainability: an additive manufacturing-enabled optimization model for minimizing waste and costs. Process Integration and Optimization for Sustainability 2024, 8, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, H.M.; Al Rashid, A.; Koç, M. Recent advancements in sustainable production and consumption: Recycling processes and impacts for additive manufacturing. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2024, 42, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekren, B.Y.; Stylos, N.; Zwiegelaar, J.; Turhanlar, E.E.; Kumar, V. Additive manufacturing integration in E-commerce supply chain network to improve resilience and competitiveness. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2023, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jedeck, S.; Yang, L.; Bai, L. Modeling and analysis of the on-demand spare parts supply using additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2019, 25, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togwe, T.; Eveleigh, T.J.; Tanju, B. An Additive Manufacturing Spare Parts Inventory Model for an Aviation Use Case. EMJ - Engineering Management Journal 2019, 31, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Karantoni, G.; Chaudhuri, A.; Srinivasan, A. Impact of additive manufacturing on aircraft supply chain performance: A system dynamics approach. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2018, 29, 846–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Mishra, U. A sustainable circular economic supply chain system with waste minimization using 3D printing and emissions reduction in plastic reforming industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 345, 131128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmsen, S.; Yi, L.; Glatt, M.; Linke, B.S.; Aurich, J.C. Reusable unit process life cycle inventory for manufacturing: high speed laser directed energy deposition. Production Engineering 2023, 17, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadayi-Usta, S. Sustainable additive manufacturing supply chains with a plithogenic stakeholder analysis: Waste reduction through digital transformation. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2024, 55, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladkikh, M.; Shan, Y.; Ayers, J.; Tackett, E.; Mao, H. Blueprint and case study for the cyber supply chain: Distributed additive manufacturing enables resilience and sustainability. Manufacturing Letters 2025, 44, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransikarbum, K.; Ha, S.; Ma, J.; Kim, N. Multi-objective optimization analysis for part-to-Printer assignment in a network of 3D fused deposition modeling. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2017, 43, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, U.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.E.; Tiwari, S.; Shaikh, A.A.; Treviño-Garza, G. An inventory model under price and stock dependent demand for controllable deterioration rate with shortages and preservation technology investment. Annals of Operations Research 2017, 254, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; He, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, H. Pricing, replenishment and preservation technology investment decisions for non-instantaneous deteriorating items. Omega 2019, 84, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, A.K.; Dey, J.K.; Mondal, S.K. Two layers supply chain in an imperfect production inventory model with two storage facilities under reliability consideration. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering 2018, 35, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosofi, M.; Kerbrat, O.; Mognol, P. Additive manufacturing processes from an environmental point of view: a new methodology for combining technical, economic, and environmental predictive models. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2019, 102, 4073–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, P.K.; Bag, A. Optimal disposal strategy with controllable deterioration and shortage. International Journal of Agricultural and Statistical Sciences 2019, 15, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Godina, R.; Ribeiro, I.; Matos, F.; Ferreira, B.T.; Carvalho, H.; Peças, P. Impact assessment of additive manufacturing on sustainable business models in industry 4.0 context. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Qu, Z.; Archibald, T.W.; Luan, Z. An inventory model of a deteriorating product considering carbon emissions. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 148, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ö.F. Examining additive manufacturing in supply chain context through an optimization model. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 142, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, A. Controllable carbon emissions in an inventory model for perishable items under trade credit policy for credit-risk customers. Carbon Capture Science & Technology 2021, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.L.; Nunes, A.O.; Martins, M.G.; Belli, M.C.; Saavedra, Y.M.; Silva, D.A.L.; Moris, V.A.d.S. Comparative LCA of conventional manufacturing vs. additive manufacturing: the case of injection moulding for recycled polymers. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 2021, 14, 1604–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamna, K.; Gautam, P.; Jaggi, C.K. Sustainable inventory policy for an imperfect production system with energy usage and volume agility. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management 2021, 12, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duary, A.; Das, S.; Arif, M.G.; Abualnaja, K.M.; Khan, M.A.A.; Zakarya, M.; Shaikh, A.A. Advance and delay in payments with the price-discount inventory model for deteriorating items under capacity constraint and partially backlogged shortages. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2022, 61, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, N.; Chauhan, A.; Pandey, R. Optimisation of an FEOQ model for deteriorating items with reliability influence demand. International Journal of Services and Operations Management 2022, 43, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, C. Optimum economic ordering and preservation technology expenditure strategy facing non-instantaneous degrading inventory as a consequence of composite impact of advertisement, trade-credit besides inflation. International Journal of Mathematical Modelling and Numerical Optimisation 2022, 12, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin Khan, M.; Abdul Halim, M.; AlArjani, A.; Akbar Shaikh, A.; Sharif Uddin, M. Inventory management with hybrid cash-advance payment for time-dependent demand, time-varying holding cost and non-instantaneous deterioration under backordering and non-terminating situations. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2022, 61, 8469–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokyasar, T.; Jin, M. Additive manufacturing capacity allocation problem over a network. IISE Transactions 2023, 55, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadman Sakib, M.; Osman, H.; Azab, A.; Baki, F. Product-platform design and multi-period, multi-platform lot-sizing for hybrid manufacturing considering stochastic demand and processing time. Manufacturing Letters 2023, 35, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Borkar, A.; Khanna, A. Sustainability enablers with price-based preservation technology and carbon reduction investment in an inventory system to regulate emissions. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 2024, 35, 402–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, F.; Al-Amin Khan, M.; Akbar Shaikh, A.; Fahad Alrasheedi, A. Interval valued inventory model for deterioration, carbon emissions and selling price dependent demand considering buy now and pay later facility. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2024, 15, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambini, A.; Martein, L. Generalized convexity and optimization: Theory and applications; Vol. 616, Springer Science & Business Media, 2008.

| Delay of payments |

(year) | (year) | ||||

| 3 month (D=0.25) |

0.5883 | 0.9972 | 3995 | 0.4859 | 0.9134 | 3969 |

| 5 month (D=0.4167) |

0.6050 | 1.0040 | 4001 | 0.5198 | 0.9043 | 4022 |

| 7 month (D=0.5833) |

0.6229 | 1.0138 | 4004 | 0.5518 | 0.8913 | 4080 |

| 8 month (D=0.6667) |

0.6324 | 1.0199 | 4004 | 0.5672 | 0.8834 | 4110 |

| 9 month (D=0.75) |

0.6422 | 1.0265 | 4003 | 0.5821 | 0.8745 | 4142 |

| Additive manufacturing | (year) | (year) | ||||

| With | 0.6229 | 1.0138 | 4004 | 0.5518 | 0.8913 | 4080 |

| Without | 0.5680 | 0.9154 | 3896 | 0.5518 | 0.8160 | 3983 |

| Cost | % change |

(year) |

% | % | % |

(year) | % | % | % |

||||

| -12 | 0.5808 | -9.34 | 0.9525 | -10.29 | 4065 | 2.60 | 0.5248 | -8.35 | 0.8319 | -11.37 | 4150 | 2.92 | |

| -10 | 0.5946 | -4.54 | 0.9630 | -5.01 | 4054 | 1.25 | 0.5295 | -4.04 | 0.8421 | -5.52 | 4138 | 1.42 | |

| 10 | 0.6500 | 4.35 | 1.0624 | 4.79 | 3956 | -1.20 | 0.5731 | 3.86 | 0.9381 | 5.25 | 4025 | -1.35 | |

| 12 | 0.6758 | 8.49 | 1.1089 | 9.38 | 3909 | -2.37 | 0.5934 | 7.54 | 0.9828 | 10.27 | 3973 | -2.62 | |

| -20 | 0.6422 | 3.10 | 0.9979 | -1.57 | 4389 | 9.62 | 0.5735 | 3.93 | 0.8972 | 0.66 | 4450 | 9.07 | |

| -10 | 0.6323 | 1.51 | 1.0055 | -0.82 | 4196 | 4.80 | 0.5621 | 1.87 | 0.8940 | 0.30 | 4265 | 4.53 | |

| 10 | 0.6142 | -1.40 | 1.0228 | 0.89 | 3811 | -4.82 | 0.5426 | -1.67 | 0.8890 | -0.26 | 3895 | -4.53 | |

| 20 | 0.6060 | -2.71 | 1.0324 | 1.83 | 3620 | -9.59 | 0.5343 | -3.17 | 0.8872 | -0.46 | 3710 | -9.07 | |

| -20 | 0.6363 | 2.15 | 1.0185 | 0.46 | 4009 | 0.12 | 0.5595 | 1.40 | 0.8933 | 0.22 | 4085 | 0.12 | |

| -10 | 0.6295 | 1.06 | 1.0161 | 0.23 | 4007 | 0.07 | 0.5556 | 0.69 | 0.8923 | 0.11 | 4082 | 0.05 | |

| 10 | 0.6165 | -1.03 | 1.0116 | -0.22 | 4001 | -0.07 | 0.5481 | -0.67 | 0.8903 | -0.11 | 4077 | -0.07 | |

| 20 | 0.6102 | -2.04 | 1.0094 | -0.43 | 3998 | -0.15 | 0.5444 | -1.34 | 0.8893 | -0.22 | 4075 | -0.12 | |

| -20 | 0.5781 | -7.91 | 1.0374 | 2.33 | 4023 | 0.47 | 0.5279 | -4.33 | 0.9163 | 2.80 | 4096 | 0.39 | |

| -10 | 0.6024 | -3.29 | 1.0246 | 1.07 | 4013 | 0.22 | 0.5407 | -2.01 | 0.9029 | 1.30 | 4087 | 0.17 | |

| 10 | 0.6407 | 2.86 | 1.0046 | -0.91 | 3996 | -0.20 | 0.5617 | 1.79 | 0.8810 | -1.16 | 4073 | -0.17 | |

| 20 | 0.6561 | 5.33 | 0.9965 | -1.71 | 3989 | -0.37 | 0.5705 | 3.39 | 0.8721 | -2.15 | 4067 | -0.32 | |

| -20 | 0.6371 | 2.28 | 1.0188 | 0.49 | 4010 | 0.15 | 0.5600 | 1.49 | 0.8935 | 0.25 | 4085 | 0.12 | |

| -10 | 0.6300 | 1.14 | 1.0163 | 0.25 | 4007 | 0.07 | 0.5559 | 0.74 | 0.8923 | 0.11 | 4083 | 0.07 | |

| 10 | 0.6161 | -1.09 | 1.0114 | -0.24 | 4001 | -0.07 | 0.5479 | -0.71 | 0.8902 | -0.12 | 4077 | -0.07 | |

| 20 | 0.6094 | -2.17 | 1.0091 | -0.46 | 3998 | -0.15 | 0.5439 | -1.43 | 0.8892 | -0.24 | 4075 | -0.12 |

| Parameter | % change |

(year) |

% | % | % |

(year) | % | % | % |

||||

| -20 | 0.6202 | -0.43 | 1.0089 | -0.48 | 4000 | -0.10 | 0.5501 | -0.31 | 0.8876 | -0.41 | 4076 | -0.10 | |

| A | -10 | 0.6217 | -0.19 | 1.0116 | -0.22 | 4002 | -0.05 | 0.5510 | -0.14 | 0.8896 | -0.19 | 4078 | -0.05 |

| 10 | 0.6240 | 0.18 | 1.0158 | 0.20 | 4005 | 0.02 | 0.5525 | 0.13 | 0.8927 | 0.16 | 4081 | 0.02 | |

| 20 | 0.6250 | 0.34 | 1.0174 | 0.36 | 4006 | 0.05 | 0.5531 | 0.24 | 0.8940 | 0.30 | 4082 | 0.05 | |

| -20 | 0.5815 | -6.65 | 0.9394 | -7.34 | 3920 | -2.10 | 0.5248 | -4.89 | 0.8346 | -6.36 | 4005 | -1.84 | |

| y | -10 | 0.6011 | -3.50 | 0.9746 | -3.87 | 3961 | -1.07 | 0.5377 | -2.56 | 0.8616 | -3.33 | 4042 | -0.93 |

| 10 | 0.6475 | 3.95 | 1.0579 | 4.35 | 40481 | 1.10 | 0.5675 | 2.85 | 0.9240 | 3.67 | 4119 | 0.96 | |

| 20 | 0.6751 | 8.38 | 1.1078 | 9.27 | 4094 | 2.25 | 0.5848 | 5.98 | 0.9604 | 7.75 | 4160 | 1.96 | |

| -20 | 0.6106 | -1.97 | 0.9917 | -2.18 | 3980 | -0.60 | 0.5439 | -1.43 | 0.8746 | -1.87 | 4059 | -0.51 | |

| -10 | 0.6167 | -1.00 | 1.0026 | -1.10 | 3992 | -0.30 | 0.5478 | -0.72 | 0.8829 | -0.94 | 4069 | -0.27 | |

| 10 | 0.6294 | 1.04 | 1.0254 | 1.14 | 4016 | 0.30 | 0.5560 | 0.76 | 0.8999 | 0.96 | 4091 | 0.27 | |

| 20 | 0.6360 | 2.10 | 1.0374 | 2.33 | 4028 | 0.60 | 0.5602 | 1.52 | 0.9088 | 1.96 | 4101 | 0.51 | |

| -10 | 0.6218 | -0.18 | 1.0116 | -0.22 | 4001 | -0.07 | 0.5511 | -0.13 | 0.8896 | -0.19 | 4078 | -0.05 | |

| e | -5 | 0.6224 | -0.08 | 1.0127 | -0.11 | 4003 | -0.02 | 0.5514 | 0.07 | 0.8904 | 0.10 | 4082 | -0.02 |

| 5 | 0.6235 | 0.10 | 1.0148 | 0.10 | 4005 | 0.02 | 0.5522 | 0.07 | 0.8920 | 0.08 | 4081 | 0.02 | |

| 10 | 0.6240 | 0.18 | 1.0517 | 0.19 | 4006 | 0.05 | 0.5525 | 0.13 | 0.8927 | 0.16 | 4082 | 0.05 |

| Parameter | % change | (year) | % | % | % | (year) | % | % | % | ||||

| -20 | 0.6486 | 4.13 | 1.0599 | 4.55 | 3045 | -23.95 | 0.5770 | 4.57 | 0.9495 | 6.63 | 3100 | -24.02 | |

| a | -10 | 0.6353 | 1.99 | 1.0360 | 2.19 | 3524 | -11.99 | 0.5640 | 2.21 | 0.9192 | 3.13 | 3589 | -12.03 |

| 10 | 0.6115 | -1.83 | 0.9933 | -2.02 | 4484 | 11.99 | 0.5406 | -2.03 | 0.8656 | -2.88 | 4571 | 12.03 | |

| 20 | 0.6009 | -3.53 | 0.9742 | -3.91 | 4964 | 23.98 | 0.5301 | -3.93 | 0.8418 | -5.55 | 5064 | 24.12 | |

| -5 | 0.6469 | 3.85 | 1.0569 | 4.25 | 4047 | 1.07 | 0.5671 | 2.77 | 0.9233 | 3.59 | 4119 | 0.96 | |

| b | -3 | 0.6370 | 2.26 | 1.0390 | 2.49 | 4029 | 0.62 | 0.5609 | 1.65 | 0.9101 | 2.11 | 4103 | 0.56 |

| 10 | 0.5822 | -6.53 | 0.9408 | -7.20 | 3922 | -2.05 | 0.5252 | -4.82 | 0.8357 | -6.24 | 2006 | -1.81 | |

| 20 | 0.5489 | -11.88 | 0.8811 | -13.09 | 3845 | -3.97 | 0.5029 | -8.86 | 0.7891 | -11.47 | 3937 | -3.50 | |

| -20 | 0.6107 | -1.96 | 0.9917 | -2.18 | 3980 | -0.60 | 0.5439 | -1.43 | 0.8746 | -1.87 | 4059 | -0.51 | |

| x | -10 | 0.6167 | -1.00 | 1.0026 | -1.10 | 3992 | -0.30 | 0.5478 | -0.72 | 0.8828 | -0.95 | 4069 | -0.27 |

| 10 | 0.6294 | 1.04 | 1.0254 | 2.33 | 4016 | 0.30 | 0.5560 | 0.76 | 0.8999 | 0.96 | 4091 | 0.27 | |

| 20 | 0.6361 | 2.12 | 1.0374 | 2.33 | 4028 | 0.60 | 0.5602 | 1.52 | 0.9088 | 1.06 | 4101 | 0.51 | |

| -5 | 0.6590 | 5.80 | 1.0787 | 6.40 | 3716 | -7.19 | 0.5744 | 4.108 | 0.9392 | 5.37 | 3786 | -7.21 | |

| p | -3 | 0.6443 | 3.44 | 1.0522 | 3.79 | 3832 | -4.30 | 0.5652 | 2.43 | 0.9197 | 3.19 | 3904 | -4.31 |

| 10 | 0.5588 | -10.29 | 0.8990 | -20.81 | 4571 | 14.16 | 0.5105 | -7.48 | 0.8032 | -9.88 | 4666 | 14.24 | |

| 20 | 0.5049 | -18.94 | 0.8028 | -20.81 | 5132 | 28.17 | 0.4745 | -14.01 | 0.7264 | -18.50 | 5235 | 28.31 | |

| -10 | 0.6153 | -1.22 | 1.0002 | -1.16 | 3989 | -0.37 | 0.5470 | -6.87 | 0.8810 | -1.16 | 4067 | -0.32 | |

| s | -5 | 0.6193 | -0.58 | 1.0074 | -0.63 | 3997 | -0.17 | 0.5495 | -0.42 | 0.8864 | -0.55 | 4074 | -0.15 |

| 5 | 0.6262 | 0.53 | 1.0196 | 0.57 | 4010 | 0.15 | 1.5539 | 0.38 | 0.8955 | 0.47 | 4085 | 0.12 | |

| 10 | 0.6291 | 1 | 1.0248 | 1.09 | 4015 | 0.27 | 0.5558 | 0.72 | 0.8994 | 0.91 | 4090 | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).