1. Introduction

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was established in 1943 by 44 Allied countries [1,2]. Its main objective was to provide humanitarian aid and reconstruction to countries affected by World War II [2,3]. As one of the most devastated countries, Poland became one of the primary beneficiaries of UNRRA aid [4,5,6]. A key area of the organisation’s activity in Poland was assistance in the agricultural and veterinary sectors to rebuild livestock populations destroyed by warfare [6,7]. World War II left Poland in a state of almost total devastation. The losses in people, infrastructure, and economy were enormous [8]. According to estimates, Poland lost about 6 million citizens, about 17% of the pre-war population [8]. Agriculture, the backbone of the Polish economy, was particularly affected by the consequences of the war. Livestock numbers fell dramatically—it is estimated that between 1939 and 1945, the number of horses decreased by around 50% and cattle by around 40% [9,10,11]. These losses had a direct impact on food production and national reconstruction. In such a situation, international assistance was essential [3,7]. This paper discusses the activities of UNRRA, particularly concerning the health problems of animals transported to Poland under this programme [12,13,14,15,16,17].

2. The Rise of UNRRA

The efforts of the Allied States to rebuild countries particularly affected by the war began even before the end of the Second World War. One of the most important tools of this aid was the UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), established in 1943 at a conference in Washington [2,22,23]. Its main objective was humanitarian aid and devastated countries’ economic and social reconstruction [2,3]. The organisation covered many areas, including agriculture, public health and veterinary medicine [7,9,10,20]. In Poland, UNRRA focused primarily on rebuilding the livestock population, crucial to the country’s food security. In addition to supplying the animals, UNRRA provided medicines and veterinary equipment and organised training for Polish veterinarians [6,7,21]. Plans for the reconstruction of Poland began to be drawn up as early as the summer of 1944 [2,22]. Initially, UNRRA held talks with the Polish Government in Exile in London, whose representatives attended the First Session of the UNRRA Council [2,10,23]. The situation changed when, in July 1944, the Soviet Union announced the administration handover of liberated Polish territories to the Polish Committee for National Liberation. UNRRA, trying to remain neutral towards the competing authorities in London and Lublin, found itself in a difficult position. Eventually, the situation was normalised after the US and UK recognised the Provisional Government of National Unity in July 1945 [2,5,24].

In March 1945, Mikhail A. Menshikov, Deputy Director General of the Area Office of UNRRA Headquarters, was appointed Chairman of the Provisional Delegation to Poland [6,18,26]. Its task was to negotiate an agreement with the Provisional Government, assess the country’s needs and prepare the ground for the start of a permanent mission. Due to visa difficulties, the delegation did not arrive in Poland until July 1945. By October of the same year, the permanent mission staff began working in Warsaw [6,18]. One of the first problems faced was the shortage of qualified personnel. In time, however, these difficulties were overcome, and in January 1946, six regional UNRRA offices were established in Katowice, Kraków, Łódź, Poznań, Gdynia and Warsaw. In September 1946, a seventh office was opened in Szczecin following the opening of the port there. At the peak of its activities in the second half of 1946, the UNRRA Mission in Poland had 162 international staff (Class I) and 260 locally recruited staff (Class II) [6,18].

The main point of contact with the Polish government was the UNRRA Affairs Office, established at the Ministry of Shipping and Trade [6]. Other ministries also cooperated with it, setting up their coordination committees and drafting aid applications, which were sent to the Council of Ministers after verification by the relevant subcommittees. The first aid transports reached Poland in the summer of 1945 via the port of Constanta on the Black Sea and then overland via Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. In September of the same year, the ports of Gdynia and Gdansk were opened, allowing the more time-consuming land transport to be dispensed with [6,18]. The scale of UNRRA aid to Poland was enormous. The value of the supplies amounted to $477,927,000, and their gross weight exceeded 2,241,889 tonnes [3,6,18]. This was the most significant aid to European countries in terms of value [3,4,5]. The organisational structure of the Polish UNRRA mission was based on models from other countries, although it contained some exceptions. The Department of Transport, headed by the Deputy Head of Mission, operated independently of the Department of Supply and was directly responsible to the Head of Mission. It managed water and rail transport supplies and supervised UNRRA port offices. It also coordinated the exporting of Polish raw materials, such as coal, to other UNRRA relief countries. The Department of Supply was responsible for distributing other supplies and implementing agricultural and industrial reconstruction programmes [6]. The UNRRA mission in Poland ended its activities on 30 June 1947 [6,18].

3. The Challenges of Animal Transport

Initially, the organisers of this project thought they would be dealing mainly with logistical issues, including loading, transporting and unloading animals at destination ports [7,9,10]. The scale of the undertaking and the impact of intercontinental transport on animal health were not foreseen or underestimated [12,13,14,17]. The need for veterinary care was assumed, but it was presumed that this would be needed within the limits of regular medical supervision. Transporting tens of thousands of animals across the ocean and several seas proved to be unprecedented and definitely affected their condition and health. Polish ports (Gdansk, Gdynia, Szczecin) received almost 150,000 livestock, of which up to 20% showed lesions or symptoms of physical exhaustion [6,31]. One ship usually housed 800 to 1,000 animals, which occupied cramped and poorly ventilated quarters, with temperatures as high as 40 °C (it is not surprising that numerous deaths occurred, e.g., a transport that arrived in Gdansk on 3 July 1946, 19 horses did not survive) [12,13,16,17]. Dr W.R. Strieber described the duties of the UNRRA veterinarian from the American side [17]. After leaving UNRRA headquarters in Washington, veterinarians went to the transhipment ports from which livestock was shipped. The tasks of the veterinary service included the selection of animals during which sick animals were separated from healthy ones. Sick specimens were sent to pens marked as hospital, surgery, lameness, sale or disposal [16,17]. In the ‘hospital’, infectious diseases were treated, mainly goitre, influenza, pneumonia, and often secondary infections with reduced immunity [14,17]. Medicines such as penicillin, intravenous and oral sulphonamides and other symptomatic measures were used [14,21]. Experimental therapies were also conducted to evaluate the efficacy of new drugs [14,17,21]. In the surgery department, abscesses were worked out, wounds were treated, and fistulas of the glomus were opened. Purulent arthritis of lacrimal origin was also treated, and rectovaginal fistulas and other minor surgical cases were occasionally operated on. Diagnosis and treatment were carried out in the lame animal enclosure. Animals requiring long-term treatment were sent to the sales department, as it was impossible to continue treatment on-site [17].

Before loading, all healthy animals were directed to the wharf and underwent a final health check [16,17]. The day before loading, one of the two doctors accompanying the transport would review the medical equipment and medicines to ensure the kits were complete [17]. Once approved, the equipment was transferred to the on-board pharmacy. UNRRA was also tasked with employing animal handling staff. They were accountable to the veterinarians [6,17]. Loading usually lasted one day, after which the veterinarians started their duties already on board [17].

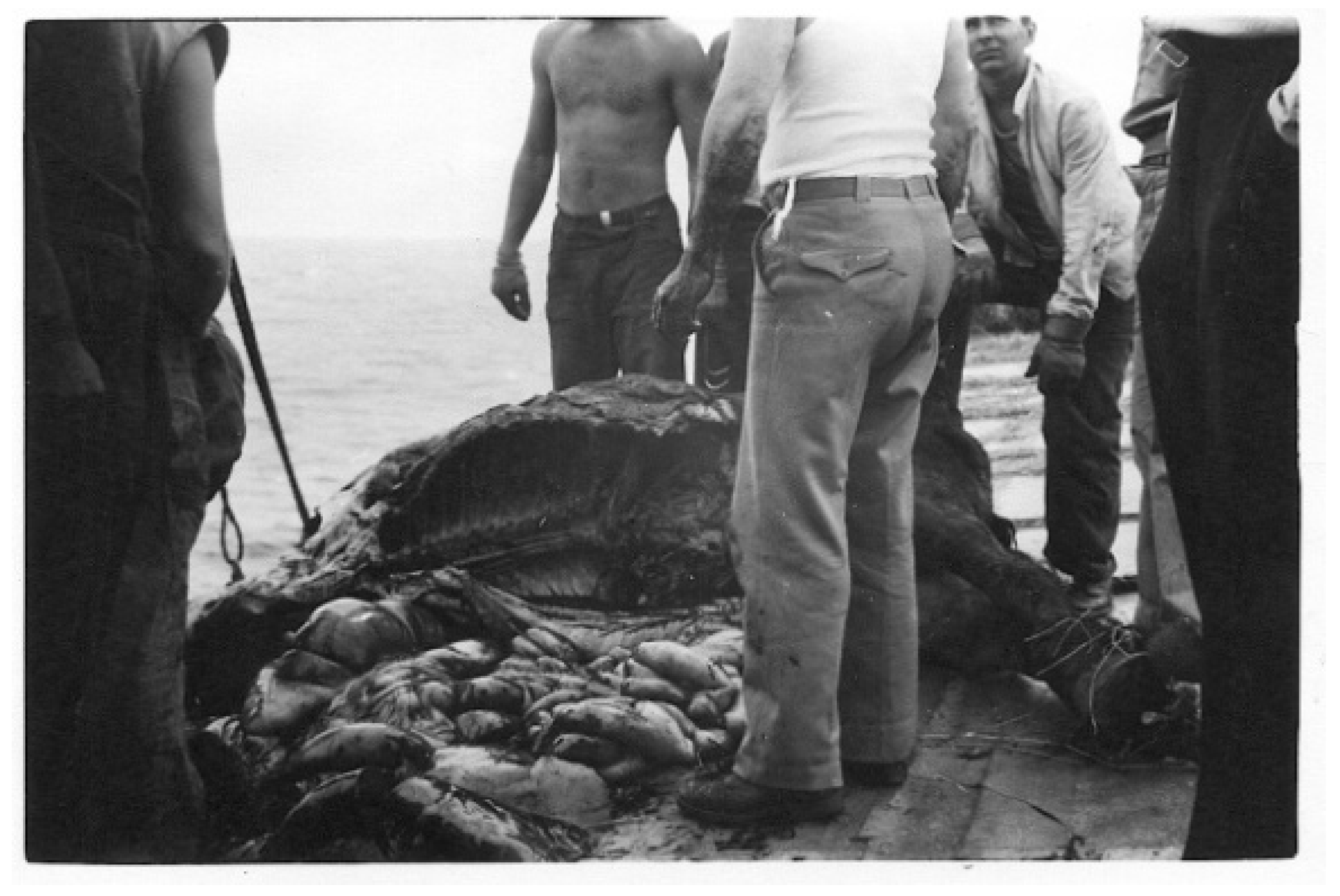

The working day during the cruise started at 8:30 in the morning. Two veterinarians would divide the animals into groups to monitor their health effectively. The rounds took place in the morning, after lunch and after 8 p.m. The eye, nose and mouth mucous membranes were checked for congestion, temperature was measured, and sick animals were diagnosed and treated [16,17]. The transport challenges are also evidenced in the memoirs of Dr Harold Burton, an American veterinarian graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, who provided care for transported animals [16,29]. According to Burton, the job at sea was to keep the animals as healthy as possible, which, with the crowded conditions in the holds, was not easy. The rooms were very poorly lit, hot and dusty, and horses and cattle always stood in manure [16,29]. Burton said that veterinary care was an extremely demanding task. Performing intravenous injections in rough seas was not the easiest of tasks. Bites, kicks, bumps, and bruises were a daily occurrence concerning the veterinarians caring for the animals. In addition to treatment activities, the vets kept records and performed post-mortems on the dead horses so that UNRRA could use these reports to improve the conditions for transporting the next consignment of animals (

Figure 1) [16,17,29].

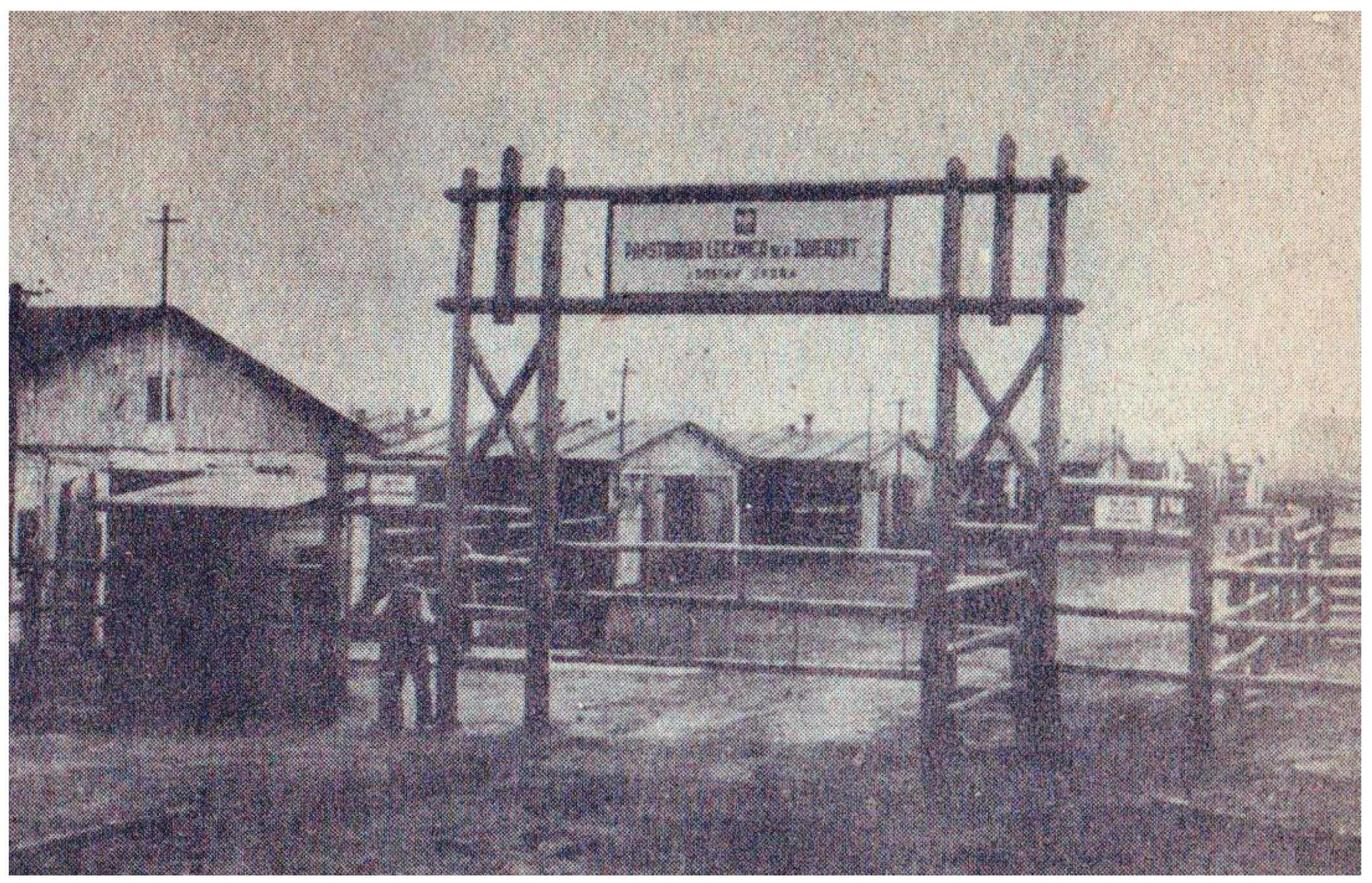

The unloading, examination and selection of animals at the end of the journey, in turn, posed a considerable logistical challenge for the post-war Polish veterinary service (

Figure 2) [6,12,13,15]. About 50 horses and a similar number of cattle were estimated to remain from one transport for inpatient treatment. A total of 4688 out of 129,949 loaded horses died. Almost 17,658 horses passed through the clinics in Gdańsk, Gdynia and Sopot (a complex of Polish port cities), and 2618 died. These figures illustrate the magnitude of the problems veterinarians face [12,13,31]. Upon arrival in Poland, the animals had to undergo a process of quarantine and adaptation to the new conditions [6,12,15].

The documents emphasise that American horses, although characterised by good trainability, were often in poor health after transport. Among the animals delivered by UNRRA, those with upper respiratory diseases predominated due to both the conditions of transport and a decline in the animals’ immunity. The documents also described cases of upper respiratory tract rhinitis and bacterial infections that required intensive treatment. One UNRRA report noted that among horses arriving from the USA, as many as 70% showed signs of respiratory disease within the first two weeks after arrival in Poland [12,14,15,28]. Veterinary clinics that received animals from UNRRA supplies used a variety of treatments. For respiratory diseases, sulphonamides, strychnine and calcium salts were used. Antibiotics were also used in more severe cases, such as bronchopneumonia, although their availability was limited [14,21]. The papers emphasise that the best results were achieved by isolating sick animals and ensuring they were calm and fed correctly. One report describes that more than 80% of sick horses were rescued at the Animal Clinic in Gdansk (

Figure 3) due to intensive care [14,15,28].

Table 1 shows the number of animals delivered to Poland as part of UNRRA aid and from Sweden [6,31]. In order to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, UNRRA also supported vaccination programmes, which were one of the key preventive measures. Horses suspected of having infectious diseases were immediately isolated to prevent epidemics [6,7,31].

Dr A. Czarnowski, head of the Animal Clinic in Sopot, where horses imported to Poland were treated, described the results of the clinical examination of most patients as follows: ‘The clinical signs of the observed conditions, in general, are as follows: Temperature varies in different horses from 39 °C to 41 °C, pulse up to 80 per minute with very weak and hardly palpable in more severe cases. Mucous membranes reddened, sometimes bluish; in some horses, there is lacrimation. Almost all animals have a nasal discharge, mostly mucous bilaterally, purulent or even purulent and bloody, sometimes snotty and smelly. Cough is rare, but it is with profuse discharge in more severe cases. In the Sopot clinic, by 1 March 1946, 24 horses showed the described respiratory symptoms, of which 14 died with symptoms of pneumonia. Sectionally, bronchial obstructive changes were found, as well as numerous abscesses in the lungs. The myocardium was slightly enlarged in most cases. Bacteriological examinations generally gave the same results, and as the author described, haemolytic streptococcus was cultured in every case. The best treatment results were observed with intravenous application of Rival 1 to 3 g in 250 ml of water and intramuscular application of Yatren Vaccine E104 and autohemotherapy with simultaneous use of seminal agents containing ether, camphor and guaiacol’ [14]. Polish veterinarians also observed that pneumonia was rarely observed in horses transported in holds located on decks and, therefore, well-ventilated, and if it occurred, it was mild. No falls were recorded [15].

Table 2 summarises horses that died during all sea transports to Poland from 5. 10. 1945 to 31. 12. 1946.

As can be seen from the attached data, the majority of horses came from the USA [6,31]. Horses from Europe (Sweden, Ireland, Iceland) arrived in Polish ports after a short voyage, significantly affecting their health status. The early-mentioned conditions on ships sailing from North America, and above all, the length of the journey, significantly affected the health of the animals. The experience gained in the first transports carried out in 1945 had an effect, and the mortality rate decreased despite the far more numerous convoys [12,13,31]. The organisation of the Polish veterinary service also improved. The existing infrastructure was initially used, but the clinic where the cases discussed above were treated was calculated to handle a maximum of 30 horses. In order to meet the enormous needs associated exclusively with the health care of animals coming from UNRRA transports, a clinic was built in Gdansk Wrzeszcz in mid-March 1946 [6,15]. By the end of May that year, more than 1,000 patients had already been treated at this facility [15]. The medical staff initially consisted of eight veterinary surgeons and eight paramedics, and by October, this had increased to 11 doctors and 12 paramedics. Treatment efficiency improved as the clinic became better equipped, staffing increased, and by the end of the year, it was 10% [15]. In addition to livestock, UNRRA assistance also included equipment and training aids, with which the programme contributed to the rebuilding and strengthening Polish veterinary medicine. Thanks to the supply of medicines, medical equipment, and training, Polish veterinarians have gained new tools to fight animal diseases [6,21,27]. The medicines supplied under the programme (including sulphonamides and antibiotics) were particularly important, and they were used to treat mainly severe cases of respiratory infections in horses and cattle from transports [14,21]. One UNRRA report noted that thanks to the training provided by the organisation, Polish veterinarians gained new skills in diagnosing and treating infectious diseases.

4. Discussion

Between the end of June 1945 and April 1947, UNRRA made some 360 livestock shipments [7,31]. Ships departed from Baltimore, Galveston, Gulfport, Houston, Montreal, New Orleans, New York, Newport News, Portland (ME) and Savannah [16,29]. These supplies were crucial to the rebuilding of Poland’s livestock population [6,7,31]. They gave Polish agriculture the necessary resources to rebuild food production [4,5,6,9]. It should be stressed that although many animals arrived in poor health, the activities of the Polish veterinary service significantly reduced losses, and healthy and cured animals were an essential part of the gradual rebuilding of livestock [12,13,14,15,28]. According to statistics, between 1946 and 1947, the horse population in Poland increased by about 20% and the cattle population by about 15% [6,9,10,31]. This resulted from the aid provided to Poland by, among others, the United States [4,32]. Although UNRRA was active in the world until September 1948, as early as mid-1946, the Polish communist authorities, under pressure from the USSR, stopped the supplies, treating the organisation as a form of US interference in Polish sovereignty [5,24,25,30,33].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Szukała, M. 80 Years Ago, UNRRA Was Established – An Organisation Providing Aid to Countries Devastated by War [80 lat temu powstała UNRRA – organizacja niosąca pomoc krajom spustoszonym wojną]. Dzieje.pl. Accessed 12 Aug 2025.

- Woodbridge, G. UNRRA: The History of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, Vol. III. New York: Columbia University Press, 1950.

- UNRRA. Relief Program for All Countries (June 1947) – Bureau of Supply, Summary Report. Luxembourg: CVCE.

- Marks, B. UNRRA Aid in Rebuilding Poland’s Economy (1945–1947) [Pomoc UNRRA w odbudowie gospodarki Polski (1945–1947)]. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis: Politologia 19 (1990).

- Reinisch, J. “We Shall Rebuild Anew a Powerful Nation”: UNRRA, Internationalism and National Reconstruction in Poland. Journal of Contemporary History 2008, 43(3): 451–476. [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, J.Z. (ed.) The UNRRA Mission in Poland. Closing Report (1945–1949) [Misja UNRRA w Polsce. Raport zamknięcia]. Lublin: Werset, 2017.

- UNRRA. Final Report on the Operations of the UNRRA Livestock Program in Europe. Washington, D.C.: United Nations, 1949.

- Harold, J. Europe Reborn: A History, 1914–2000. London: Routledge, 2003. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 1948. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1948.

- FAO. European Livestock Rehabilitation Programs, 1945–1948. Rome: FAO, 1949. https://www.fao.org/4/ap637e/ap637e.pdf.

- World Bank (Economic Department). Poland – Post-war Rehabilitation Notes (with references to UNRRA experts). Washington, D.C., 1947.

- Pępkowski, A. UNRRA Animal Deliveries for Poland (Part II) [Dostawy zwierząt UNRRA dla Polski (cz. II)]. Medycyna Weterynaryjna 1947; 3(4): 233–235.

- Pępkowski, A. UNRRA Animal Deliveries for Poland (Part III) [Dostawy zwierząt UNRRA dla Polski (cz. III)]. Medycyna Weterynaryjna 1947; 3(5): 305–307.

- Czarnowski, A. Causes of Pneumonia in Horses Delivered by UNRRA [Przyczyny zapaleń płuc u koni dostarczonych przez UNRRA]. Medycyna Weterynaryjna 1946; 1(8): 363–365.

- Staśkiewicz, G. State Animal Clinic for UNRRA Deliveries [Państwowa lecznica dla zwierząt z dostaw UNRRA]. Medycyna Weterynaryjna 1946; 1(10): 486.

- Seagoing Cowboys Blog. UNRRA Livestock Trips from the Eyes of a Veterinarian. 2021.

- Strieber, W.R. UNRRA Veterinarian’s Duties. The Veterinary Student 1947: 152–153.

- UN Archives (UNARMS). UNRRA Selected Records: Poland Mission (AG-018-026).

- UN Archives (UNARMS). Records of the UNRRA (1943–1948) – Collection Overview.

- UN Yearbook. United Nations Yearbook 1948–49 – FAO (Livestock, Feeding, Coordination).

- Łotysz, S. Penicillin and Prosthetics – Import and Launch of Production in Poland (UNRRA Context) [Penicylina i protezy – import i uruchomienie produkcji w Polsce (kontekst UNRRA)]. Quarterly of the History of Science and Technology 2018; 63(3).

- UNRRA. Interim Report (15 September–31 December 1944).

- Columbia University Libraries. United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration – Finding Aid.

- Reinisch, J. ‘Auntie UNRRA’ at the Crossroads. Past & Present (Suppl.) 2013; 218(suppl_8): 70–97. [CrossRef]

- Łaptos, J. Humanitarianism and Politics: UNRRA Aid for Poland and Polish Refugees (1944–1947) [Humanitaryzm i polityka. Pomoc UNRRA dla Polski i polskich uchodźców w latach 1944–1947]. Kraków, 2018.

- UNARMS. Poland Mission – AG-018-026.

- Jones, S.D.; Koolmees, P.A. A Concise History of Veterinary Medicine. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Wasielewski, J. How Horses from UNRRA Were Treated in Gdańsk after the War [Jak po wojnie leczono konie z UNRRY w Gdańsku]. Trojmiasto.pl, 26 Feb 2019.

- Seagoing Cowboys Project. The UNRRA Years (1945–1947).

- Clavin, P. Securing the World Economy: The Reinvention of the League of Nations, 1945–1955. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- UNRRA / FAO. Livestock Shipments to Poland (Statistical Summary, 1945–1947). Based on FAO Archives, Rome.

- Waluk-Legun, L. American Aid for Poland after World War II [Pomoc amerykańska dla Polski po II wojnie światowej]. Accessed 2 Feb 2025.

- Łaptos, J. UNRRA, IRO and French Authorities on Polish Displaced Persons Becoming Political Refugees (1944–1950) […przeobrażania się polskich dipisów w uchodźców politycznych]. Prace Historyczne (UJ).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).