1. Introduction

Medical diagnosis is the process of determining the nature and cause of a disease or condition by analyzing the patient’s symptoms, medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic test results [

1,

2]. It is a multifaceted process that relies on a combination of patient history, physical examination, diagnostic tests, clinical reasoning, collaboration, and effective communication. By systematically evaluating patients’ symptoms and clinical data, healthcare providers can arrive at accurate diagnoses and provide appropriate treatment and management strategies. A medical diagnosis system is a computer-based tool or software designed to assist healthcare professionals in the process of diagnosing diseases and medical conditions. These systems utilize various technologies, algorithms, and databases to analyze patient data, symptoms, and medical history to generate potential diagnoses or provide decision support for clinicians.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a

neurological and developmental disorder whose etiologies are largely unknown [

3]. Autism is a complex brain disorder that inhibits a person’s ability to carry out social communication and interaction and also exhibit restricted interest and repetitive behaviours [

4].

The onset of the disorder occurs during the developmental period, typically in early childhood and last throughout a person’s life time. Symptoms of autism are usually apparent very early but it is usually not understood by parents until later stage of a child’s life when social demands exceed limited capacities [

5,

6]

. Thus, diagnoses are not carried out until 2 to 3 years of a child’s life. The autism spectrum disorders belong to an “umbrella” class category of five childhood onset conditions called Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD). The following three are the most 3common PDD: Autism Spectrum Disorder, Asperger Syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) also known as a typical autism. Childhood disintegration and Rett Syndrome are the other pervasive developmental disorders [

7]. They occur rarely and Rett Syndrome is believed to affect only girls. People stricken with autism disorder have vital language delays, social and communication challenges (i.e cannot talk and avoid eye contact), unusual behaviors and interest, and usually have intellectual disability.

Autism is referred to as a spectrum disorder because of the wide variation in the type and severity of symptoms people experience. Due to

the unique mixture of symptoms seen in each child, severity can sometimes be difficult to determine [

8]

. It’s generally based on the level of impairments and how they impact the ability to function. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is said to be “an equal opportunity disorder, which occurs in all ethnic and socio-economic groups, affects every age group no matter which country or culture and it is on the rise [

9]. According to Klauck [

10], 1 out of every 100 children is on the autism spectrum. Researches over the years have not been able to give a satisfactory understanding of the causative factors of the disorder [

8]. Studies suggest that genes can act together with influences from the environment to affect development in ways that lead to ASD [

11]. Some factors are believed to increase the risk of developing ASD. Such risk factors include: Age of parents at conception; having a sibling with ASD; a child born with very low birth weight and having certain genetic conditions (For example, people with Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and Rett syndrome are more likely than others to have ASD) [

12].

Characteristics of autism may be detected in early childhood, but is often not diagnosed until two to three years of a child’s life due to lack of definitive biomarkers that pinpoint the disorder. However, the earliest symptom is the absence of normal behavior [

13]. There is no single medical test that can diagnose it definitively; instead, in order to accurately pinpoint a child’s problem, multiple evaluations and tests may be necessary. Early recognition is the linchpin of repelling the disorder. While currently, there is no cure for autism, early detection, recognition and treatment will help to improve the diverse symptoms associated with the disease, and the ASD victims will integrate into the society and develop as healthy children do [

14].

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent challenges in social interaction, communication, and behavior. Early identification and intervention play a crucial role in improving outcomes for individuals with ASD, highlighting the importance of accurate predictive models [

15]. In this context, adaptive neuro-fuzzy systems offer a promising approach by combining the adaptive learning capabilities of neural networks with the interpretability of fuzzy logic. This study presents an adaptive neuro-fuzzy model specifically tailored for predicting autism in pediatric cases. By leveraging a diverse range of features and employing advanced computational techniques, the model aims to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of autism diagnosis, facilitating early intervention and support for affected children and their families. For this study, the hybridization of artificial neural network and fuzzy logic will be used to establish a system of early diagnosis of ASD as well as the level of severity of the disorder in children. The result of applying the combination of artificial neural network and fuzzy logic in diagnosing autism testifies to its accuracy in detecting autism early in a child’s life. Many of the youngsters of today, who are meant to make great contributions to the future growth of this country, are struggling with developmental obstacles like ASD. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a chronic, severe condition that affects the brain’s ability to develop social and communication skills. It is also characterized by repetitive or constrained behaviors and interests [

4]. ASD is the developmental disability with the fastest rate of growth, and prevalence rates are increasing incredibly quickly (CDC, 2020). According to current estimates, 1.5% of the world’s population is on the autistic spectrum, and it is believed that many ASDs in the community go undiagnosed [

16,

17]. Therefore, the need for early identification and prompt intervention has grown as a result of greater awareness of ASD [

18]. This is crucial because getting an ASD diagnosis is a “critical milestone,” allowing parents to better understand their child’s needs and gain access to vital resources (such as therapy and special education). In the first two or three years of a child’s existence, parents typically become aware of indicators, which frequently appear gradually. Although it is not difficult to diagnose autism, doctors must undergo extensive education and training in order to do so. It is believed that autism is a systemic body condition that affects the brain rather than a genetic brain disorder [

19]. There are several methods used in the detection of autism. The initial method is the classic one in which the diagnosis is based on series of abnormal behaviours, like repetitive and restricted symptoms. However, the accuracy level of this method is low and not suitable for infant less than 24 months because expression of the symptoms of autism in younger children is usually unclear.

Autism Screening tools like CHAT (Checklist for Autism in Toddlers), ITC (Infant Toddler Checklist) M-CHAT, Q-CHAR are used to detect autism by observing the child’s communication skill and emotions. Diagnostic autism tools like Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic (ADOS-G), Childhood Autism Rating. Scale (CARS) and Gilliam Autism Rating Scale-2 (GARS-2) are all used in predicting autism However, these rating scales have the same common ground. They assess information about autism via questions, sum up points and conclude by classifying types and level of autism. For instance, in the CARS, the scale has three levels; mild, moderate and severe. The methods mentioned above are incapable of grasping the complexity of ASD leading to lots of false positive and false negative cases as a result of the property of the rating scale and accuracy of the evaluators result. In order to fix those drawbacks, Artificial intelligence techniques will be applied to improve the accuracy of early autism diagnosis.

2. Methodology

The proposed system is tagged

Hybrid Intelligent Model for prediction of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children. The system shall explore technology beyond the soft computing approach for object-oriented prediction rather than components based system used in the existing system [

20]. It also builds quality prediction on the principles of neuro-fuzzy hybridization technique at the design stage before coding.

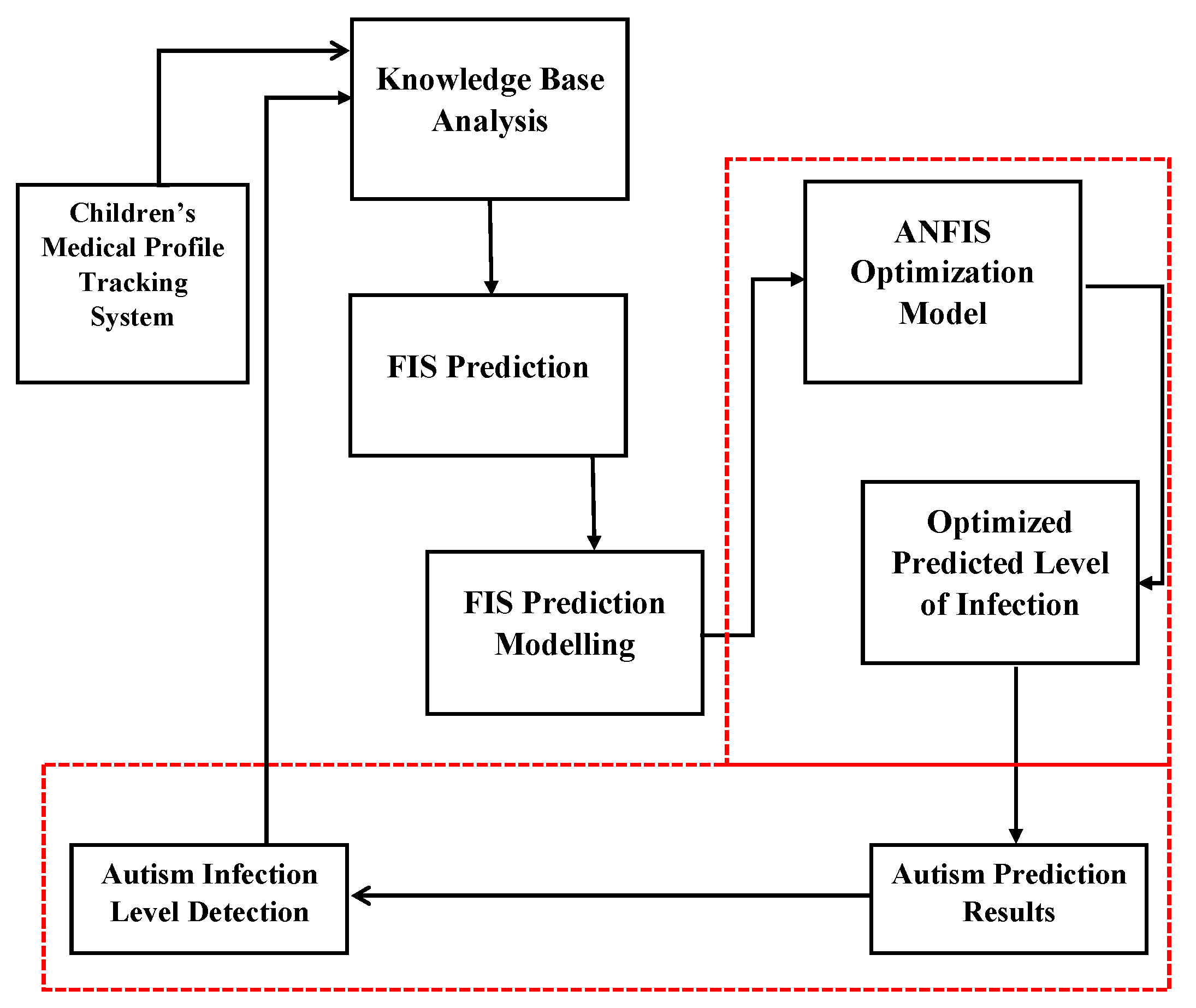

A comprehensive dataset comprising behavioral observations, developmental milestones, and clinical assessments of pediatric cases is compiled from multiple sources, including medical records, caregiver reports, and standardized assessments. The collected data was preprocessed and used in the hybrid model to carry out the prediction. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework of the proposed system.

A. Data Collection

A comprehensive dataset comprising behavioral observations, developmental milestones, and clinical assessments of pediatric cases was compiled from multiple sources, including medical records, caregiver reports, and standardized assessments. Collection of the dataset for predicting autism in pediatric cases was carried out by gathering questionnaires at the Enugu University Teaching Hospital through behavioral observations, developmental milestones, and clinical assessments of pediatric cases from multiple sources, including medical records, caregiver reports, and standardized assessments. These synthetic data mimic real-world characteristics of children with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The dataset consists of the following features:

“Child ID”: Uniquely identifies each child in the dataset.

“Age (months)”: Represents the age of the child in months at the time of assessment.

“Sex”: Indicates the gender of the child (M for Male, F for Female).

“Eye Contact”: Numerical score representing the level of eye contact observed.

“Gesture Use”: Numerical score representing the use of gestures observed.

“Language Skills”: Numerical score representing language skills observed.

“Sensitivity to Pains”: Numerical score representing the sensitivity of the child to pains observed.

“Communication Test”: Numerical score representing communication abilities observed.

“Social Interaction Score”: Composite score representing the child’s overall social interaction abilities.

“Diagnosis (ASD)”: Target feature indicating whether the child has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (Yes or No).

The dataset was composed of 5000 entries, each representing real-life values based on known distributions and patterns in pediatric assessments and autism diagnosis. Due to the lack of existing records on children between the ages of 6-24 months living with autism, this survey was conducted to collect the necessary data for the research. The primary source of data was unstructured interviews with pediatricians in the autism domain, where four parametric variables used for autism prediction were identified: eye contact level, sensitivity of the child to pain, social and environmental interaction, and communication test. The secondary source of data was a survey conducted using a well-structured questionnaire filled out by doctors and parents of autistic children. The questionnaire used consisted of two parts:

Bio data information of the child, including age, gender, ethnicity, and if the child was born with jaundice and the clinical evaluation, where questions were formulated based on the four parametric variables on autism. As earlier stated, this dataset contains 5000 entries with various characteristics and behaviors observed in children, along with their diagnosis status. Each entry includes values for the features mentioned above.

Table 1.

Shows the sample dataset of the collected data.

Table 1.

Shows the sample dataset of the collected data.

| Child ID |

Age (months) |

Sex |

Eye Contact |

Gesture Use |

Language Skills |

Sensitivity to Pains |

Commu-nication Test |

Social Interaction Score |

Diagnosis (ASD) |

| 1 |

24 |

M |

3 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

Yes |

| 2 |

18 |

F |

2 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

No |

| 3 |

36 |

M |

4 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

8 |

10 |

Yes |

| 4 |

21 |

F |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

No |

| 5 |

30 |

M |

3 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

7 |

9 |

Yes |

| 6 |

15 |

F |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

No |

| 7 |

27 |

M |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

6 |

7 |

Yes |

| 8 |

12 |

F |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

No |

| 9 |

33 |

M |

4 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

9 |

11 |

Yes |

| 10 |

14 |

F |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

No |

B. Feature Selection and Preprocessing

Relevant features are selected based on their relevance to autism diagnosis and undergo preprocessing to standardize data formats, handle missing values, and normalize feature scales.

C. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Model Design

An adaptive neuro-fuzzy model (ANFM) was developed, consisting of interconnected neural network modules and fuzzy logic inference mechanisms [

22,

23]. The model architecture is optimized to accommodate the complexity of autism diagnosis and adapt to varying input data.

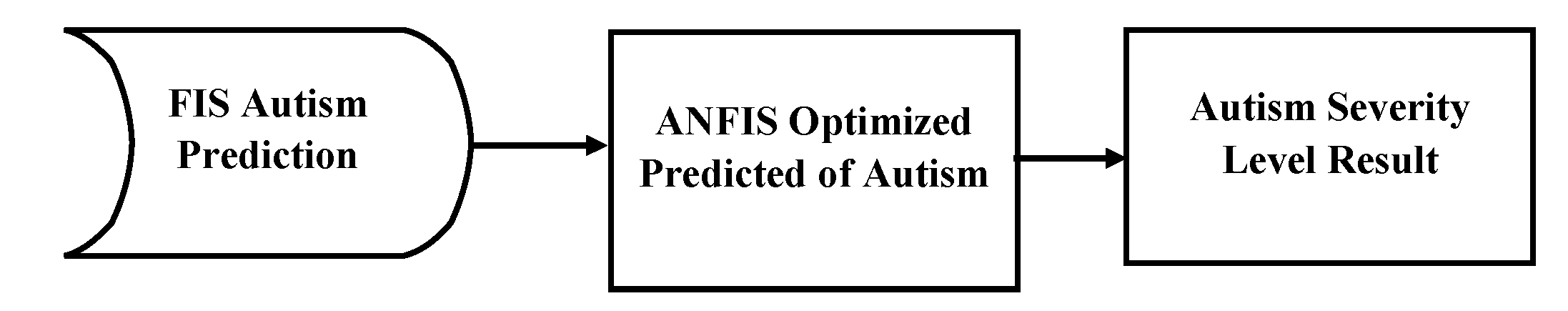

Figure 2, shows the ANFM.

In the above framework, Fuzzy Logic is used as the soft computing techniques to predict the level of infection of the child to autism and the output is fed into the ANFIS model for optimization.

The model uses six (6) metrics to determine the presence of autism in a child and as well as severity level; the four metrics are: Gesture Use, Language Skills, Eye Contact Level (ECL), Child’s sensitivity to pains (SCP), Child’s response to Social and Environmental Interaction (SEI), and Communication Test (CT). Figure 3 below shows the conceptual frame work of the fuzzy object-oriented software Adherence prediction. In this work, a type-1 fuzzy logic model was used. This model is based on a triangular membership function that defines a degree of membership of all crisp values within the specified universe of discourse.

(i) Fuzzification

In this stage, for each input and output variable selected, we define four membership functions (MF), namely –Eye Contact Level (ECL), Child’s sensitivity to pains (SCP), Child’s response to Social and Environmental Interaction (SEI), and Communication Test (CT). A category is defined for each of the variable, these categories are called fuzzy term. We employ triangular membership function. For this reason, we need at least three points (o, p, q) to define one Membership Function (MF) of a variable [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. The triangular membership function is defined as;

Where:

o - the left leg of the membership function

p - the center of the function

q - the right leg of the function

x - the crisp input

f - a mapping function

(ii) Fuzzy rule base

A fuzzy rule is defined as a conditional statement in the form [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]:

Where:

, is rule number

- is the current rule

- is the number of linguistic variable

- is the p’s linguistic variable

- is the p’s linguistic term of rule - is the output linguistic variable of rule

(iii) Membership matrix

This shows the degree of membership at various levels of the crisp inputs. The membership matrix is computed by substituting the different crisp input into the triangular membership function [

2]. The membership matrix for this work is generated a membership function evaluator software presented in the tables below;

(I) Membership matrix for

Eye Contact Level

Table 2.

Membership Matrix for Eye Contact Level.

Table 2.

Membership Matrix for Eye Contact Level.

| FUZZY SET |

CRISP INPUT |

| 0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.89 |

0.9 |

| N |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| R |

0.272 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| SD |

0.00 |

0.618 |

0.140 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| D |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.782 |

0.518 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| VD |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.717 |

0.874 |

0.930 |

0.792 |

0.857 |

(II) Membership matrix for Child’s Sensitivity to Pains.

Table 3.

Membership Matrix for Child’s Sensitivity to Pains.

Table 3.

Membership Matrix for Child’s Sensitivity to Pains.

| FUZZY SET |

CRISP INPUT |

| 10 |

20 |

30 |

40 |

60 |

70 |

80 |

90 |

| VVS |

0.937 |

0.326 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| VS |

0.00 |

0.361 |

0.8 94 |

0.348 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| S |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.262 |

0.359 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| SS |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.230 |

0.996 |

0.238 |

0.00 |

| NS |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.340 |

0.830 |

(III) Membership matrix for Social & Environmental Interaction.

Table 4.

Membership Matrix for Social & Environmental Interaction.

Table 4.

Membership Matrix for Social & Environmental Interaction.

| FUZZY SET |

CRISP INPUT |

| 1 |

2 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.5 |

4 |

4.5 |

5 |

| NI |

0.369 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| SI |

0.340 |

0.343 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| NI |

0.00 |

0.268 |

0.975 |

0.319 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| HI |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.275 |

1.00 |

0.275 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| VHI |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.374 |

0.813 |

0.00 |

(IV) Membership matrix for Communication Test.

Table 5.

Membership Matrix for Communication Test.

Table 5.

Membership Matrix for Communication Test.

| FUZZY SET |

CRISP INPUT |

| 0.12 |

0.21 |

0.32 |

0.42 |

0.5 |

0.61 |

0.78 |

0.98 |

| N |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| S |

0.388 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| A |

0.324 |

0.472 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| P |

0.00 |

0.132 |

0.697 |

0.790 |

0.380 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| VP |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.440 |

0.880 |

0.0800 |

(iv) Rule Evaluation.

Table 6.

Rule Evaluation.

Table 6.

Rule Evaluation.

| Rule No. |

Firing Interval |

Consequent |

Max |

| R1 |

[0.629*0.510*0.523*0.233]= .168 |

|

LI[0.0]

SI[0.0]

I[0.348]

VI[0.263]

MI[0.0] |

| R2 |

[0.518*0.262*0.975*0.697]= .262 |

[0.263] |

R3

R4 |

[0.421*0.344*0.975*0.697]= .075

[0.217*0.262*0.975*0.697]=0.217 |

[0.217]

[0.217] |

(v) Defuzzification.

The defuzzificationofthe fuzzy set was carried out by using the center of gravity defuzzification method presented in equation 10;

where µ

A(x) is the degree of membership of x in a set P.

3. Results and Discussions

A. ANFIS training procedure

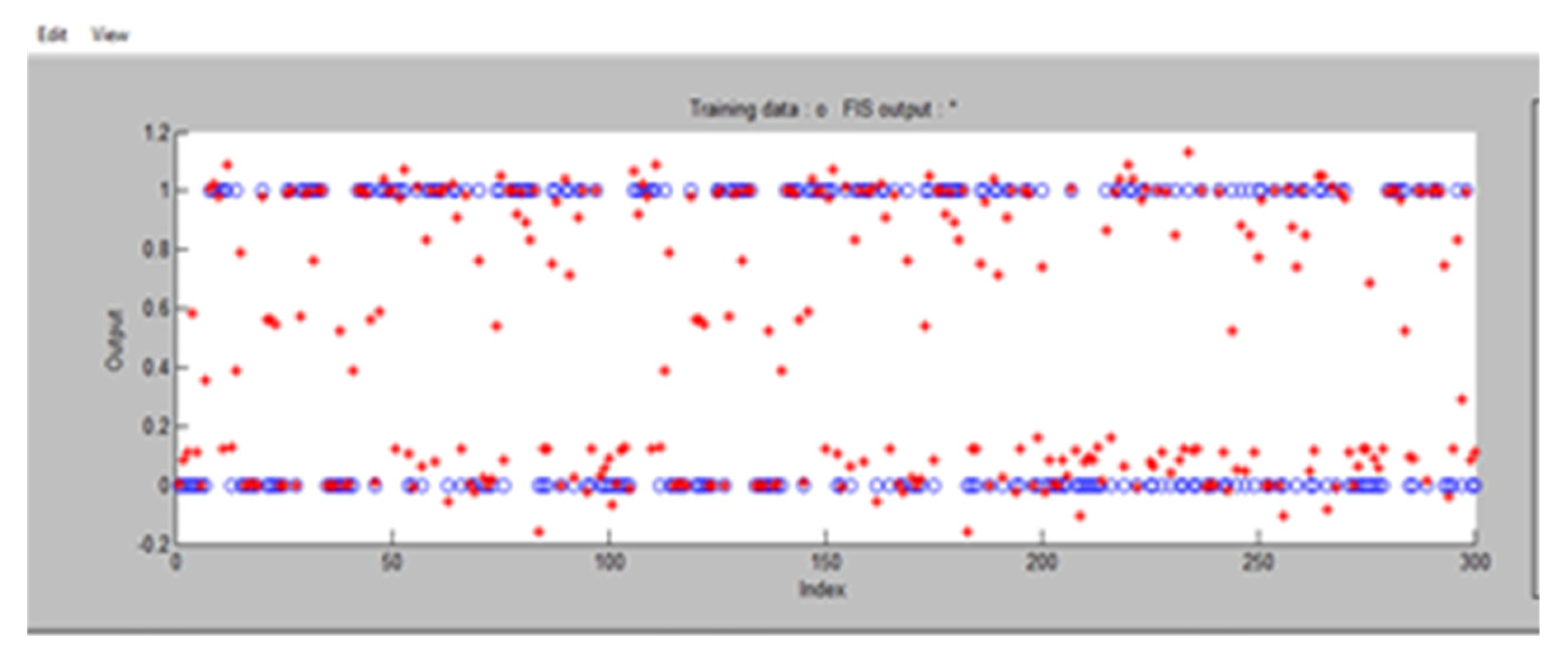

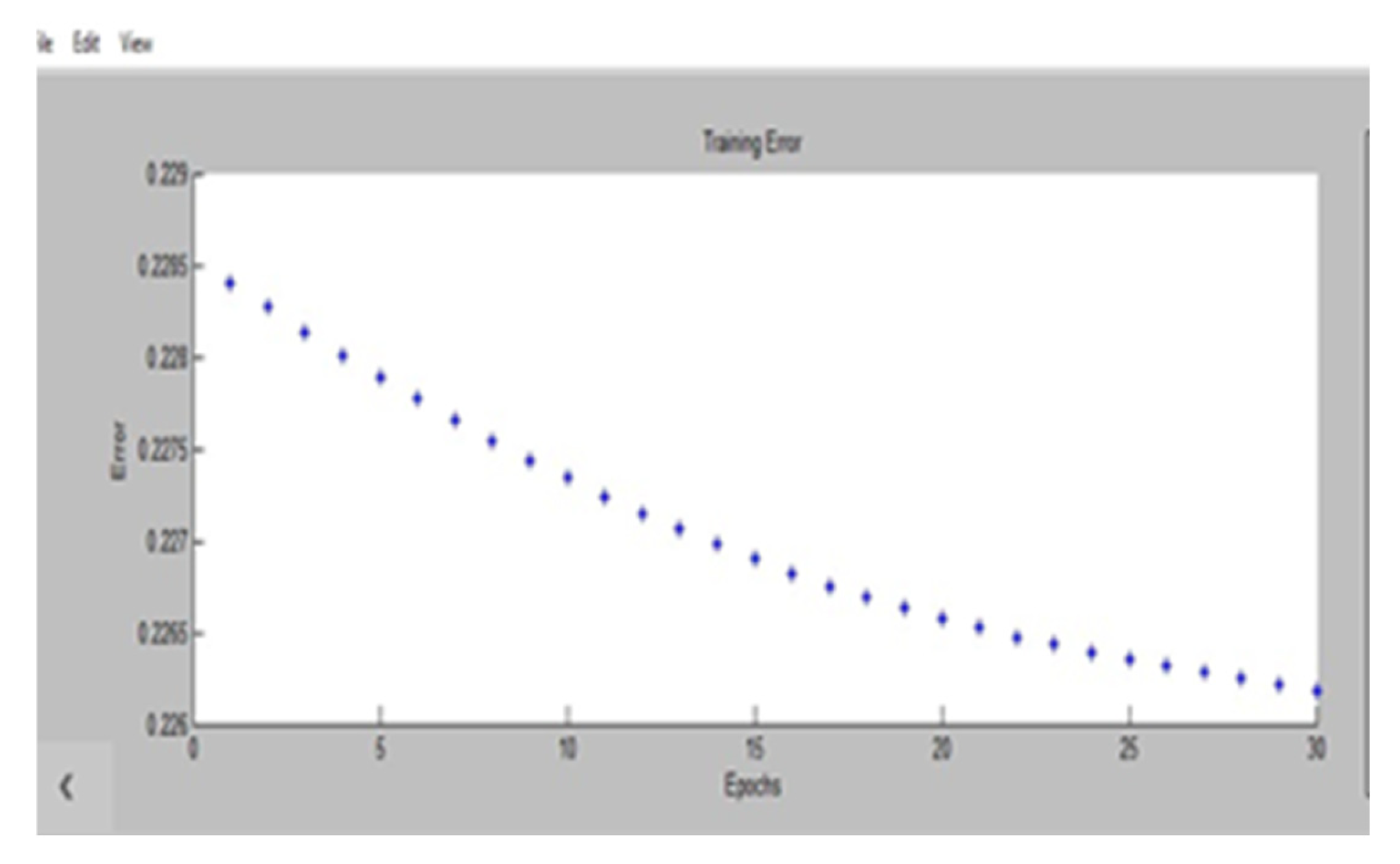

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, shows the ANFIS training plot, ANFIS Training Error plot, and ANFIS Checking plot respectively. The checking data are represented by the (+) sign the number of checking data pairs are 300.

B. ANFIS model validation

From

Table 7, at epoch 300, the testing error value of 0.19379 is observed between the computed data and the desired output. The observed error value is far greater the error tolerance of 0.0001 specified in the train FIS. The idea behind using a checking data set for model validation is that after a certain point in the training, the model begins over fitting the training data set. In principle, the model error for the checking data set tends to decrease as the training takes place up to the points that over fitting begins, and then the model error for the checking data suddenly increases. Over fitting is accounted for by testing the FIS trained on the training data against the checking data, and chosen the membership function parameter to be those associated with the minimum checking error if these errors indicate model over fitting.

The presented results provide insights into the performance of the adaptive neuro-fuzzy model for predicting autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children. The model underwent training and optimization over multiple epochs, with the training, checking, and testing errors monitored to evaluate its performance. The epochs represent the number of iterations or training cycles the model underwent during the learning process. The training error is the metric which indicates the error between the predicted values and the actual values in the training dataset. A decreasing trend in training error across epochs suggests that the model is learning and improving its performance on the training data. The checking error is a measure of the model’s performance on a validation dataset, which is distinct from the training data. It helps prevent overfitting by evaluating the model’s generalization ability. Ideally, the checking error should decrease initially and then stabilize or increase slightly. The testing error reflects the model’s performance on unseen data, typically reserved for final evaluation. It provides insights into how well the model generalizes to new, unseen instances. Lower testing errors indicate better predictive performance. The average error provides a summary of the overall performance of the model across different epochs. It considers the training, checking, and testing errors to provide a comprehensive assessment.

In the initial epochs (e.g., epochs 30 and 60), the training error decreases gradually, indicating that the model is learning from the training data. However, the checking error may initially decrease or fluctuate before stabilizing. As the number of epochs increases, the model’s performance on the training data improves, as evidenced by decreasing training errors. However, it’s crucial to monitor the checking error to ensure that the model does not overfit to the training data. The testing error, which reflects the model’s generalization ability, may vary across epochs. Lower testing errors suggest better performance on unseen data. It was noticed that the average error provides a consolidated view of the model’s performance across epochs. A decreasing trend in the average error indicates that the model is improving over time. In general, the results suggest that the adaptive neuro-fuzzy model demonstrates promising performance in predicting autism in pediatric cases.

At the cause of comparing the performance of ANFIS with Hybrid Algorithm and ANFIS with Back Propagation Algorithm; the analysis was done based on several metrics such as training error, checking error, testing error, and average error across different epochs. Lower values indicate better performance in terms of error minimization. ANFIS with Back Propagation Algorithm generally has higher training errors compared to ANFIS with Hybrid Algorithm across all epochs. This indicates that the Back Propagation Algorithm may struggle more during the training phase to minimize errors. Both algorithms show fluctuations in the checking error, but ANFIS with Hybrid Algorithm tends to have lower checking errors in most epochs compared to ANFIS with Back Propagation Algorithm. ANFIS with Hybrid Algorithm demonstrates better performance in terms of testing error reduction, especially in the earlier epochs. However, ANFIS with Back Propagation Algorithm achieves lower testing errors in some epochs as well. Overall, ANFIS with Hybrid Algorithm maintains lower average errors compared to ANFIS with Back Propagation Algorithm, indicating better overall performance in error minimization.

Based on this results, ANFIS with Hybrid Algorithm appears to outperform ANFIS with Back Propagation Algorithm in terms of error minimization, particularly in the training and testing phases.

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 shows the ANFIS Performance with Hybrid Algorithm, ANFIS Performance with Back Propagation Algorithm and ANFIS training Information respectively.

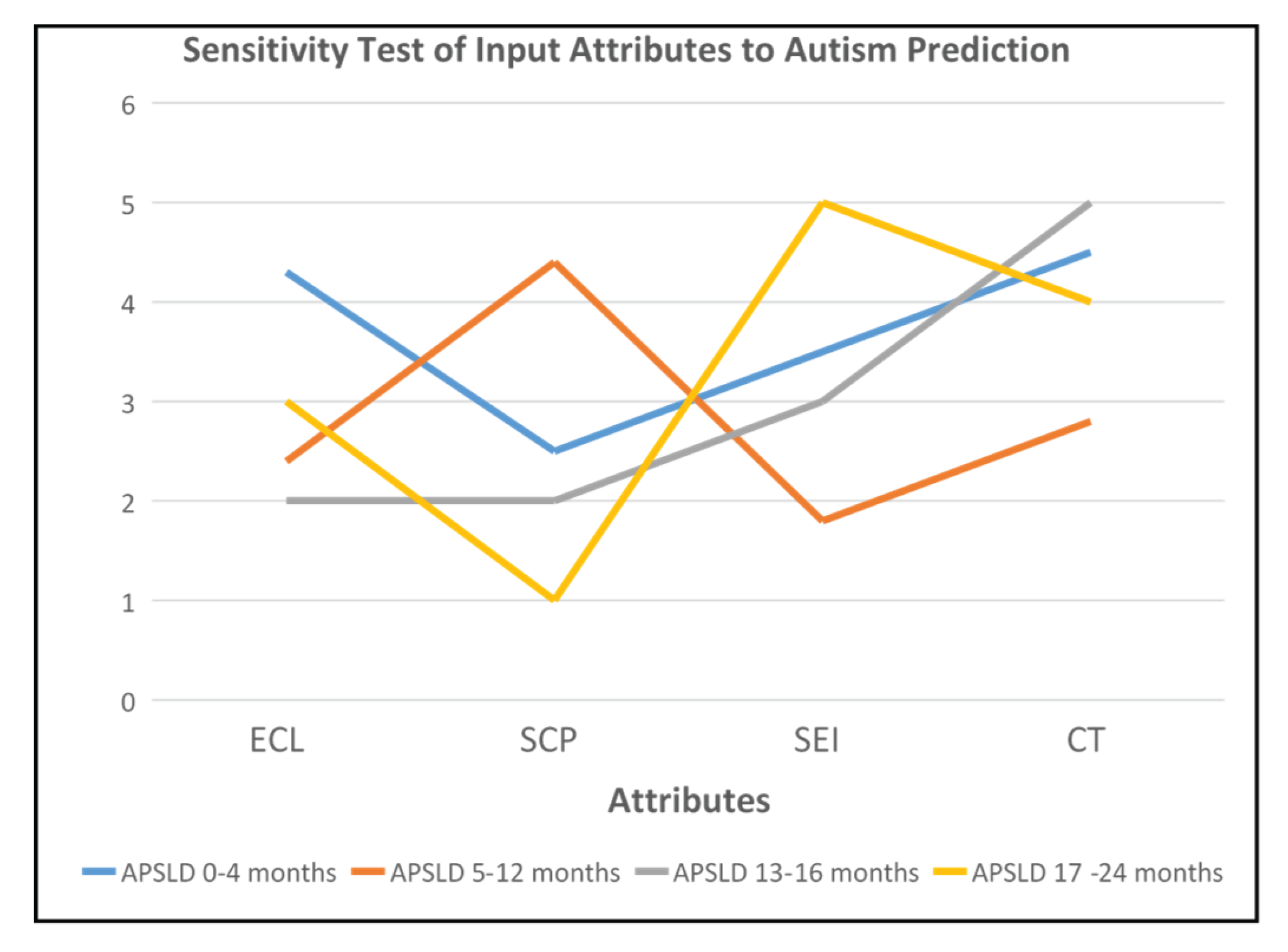

C. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the level of contributions or degree of significance of inputs to output. In this research, Matab was used to plot the graph of the sensitivity of the input to the output variables as shown in

Figure 7.

Considering the percentage input contributions to output; the contributions were segmented into four (4) groups. Group A were input which scored above 69%, Group B scored above 59% but less than or equals to 69%, Group C scored above 40% and below but less than 59% while inputs with less than 1% score were grouped in F. SCP has the highest score of 75.10%, in the prediction of the presence of autism disorder in children between the age of six to 24 months. ECL and SEI have scores of 65.32% and 67.50% respectively in the sensitivity analysis. The variable CT scored 40.85% which contributed 40.85% to the determination of output. No variable had below 1%. Based on this analysis, the variables SCP, ECL and SEI with scores A, B and B respectively are very important variables in predicting autism disorder in children, whilst variable CT plays less role.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study presents a comprehensive approach to early detection and prediction of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in pediatric cases. Autism, characterized by its complex neurological and developmental features, poses significant challenges in early diagnosis and intervention. Despite its onset during the developmental period, typically in early childhood, ASD often remains undiagnosed until 2 to 3 years of age, when social demands exceed limited capacities. This delay underscores the critical need for accurate predictive models to facilitate timely intervention and support for affected children and their families. The proposed Hybrid Intelligent Model leverages adaptive neuro-fuzzy systems to predict ASD and assess its severity in children. By integrating artificial neural network capabilities with fuzzy logic, the model offers a robust framework for ASD diagnosis, utilizing diverse features such as eye contact, gesture use, language skills, sensitivity to pain, communication abilities, and social interaction. Through fuzzification, fuzzy rule base establishment, membership matrix computation, and defuzzification, the model achieves enhanced accuracy in predicting ASD and evaluating its severity. Results from the study demonstrate the effectiveness of the adaptive neuro-fuzzy model in predicting ASD in pediatric cases, with a testing accuracy of 98%. Sensitivity analysis reveals the significant contributions of input variables, with sensitivity to pain, eye contact level, and social interaction emerging as crucial factors in ASD prediction. Comparative analysis with the Back Propagation Algorithm highlights the superiority of the proposed Hybrid Algorithm in error minimization and overall performance. In general, the study contributes to advancing the understanding and management of ASD, offering a valuable tool for early diagnosis and intervention. The Hybrid Intelligent Model holds promise in improving outcomes for individuals with ASD by enabling early identification and access to vital resources such as therapy and special education. By bridging the gap in early detection of ASD, this research aims to enhance the quality of life for affected children and their families, ultimately fostering integration and development within society.

5. Research Contribution

The diagnosis and prediction of autism has always been done on patients two years and above. The contribution in this research work is predicting the disease in children between six months and twenty-four months. This early period of diagnosis will enable early intervention and treatment that will see the child live a normal or fairly normal life.

Secondly, the work could be deployed to rural areas so that medical practitioners, who are not very vast in the autism domain, could predict the disease with ease.

References

- G. G. James, E. G. Chukwu, and P. O. Ekwe, “Design of an Intelligent based System for the Diagnosis of Lung Cancer,” Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 791–796, 2023.

- Umoh, U. A., Umoh, A. A., James, G. G., Oton, U. U., Udoudo, J. J., B.Eng., “Design of Pattern Recognition System for the Diagnosis of Gonorrhea Disease,” International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, pp. 74–79, June 2012.

- M. Bakare et al., “Etiological explanation, treatability and preventability of childhood autism: a survey of Nigerian healthcare workers’ opinion,” Ann. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 6, 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Ruzich et al., “Measuring autistic traits in the general population: a systematic review of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) in a nonclinical population sample of 6,900 typical adult males and females,” Mol. Autism, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 2, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Stevens, D. R. Dixon, M. N. Novack, D. Granpeesheh, T. Smith, and E. Linstead, “Identification and analysis of behavioral phenotypes in autism spectrum disorder via unsupervised machine learning,” Int. J. Med. Inf., vol. 129, pp. 29–36, Sept. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Nasser, M. O. Al-Shawwa, and S. S. Abu-Naser, “Artificial Neural Network for Diagnose Autism Spectrum Disorder,” vol. 3, no. 2, 2019.

- Ms. R. Kundu and M. Suranjan Das, “Predicting Autism Spectrum Disorder in Infants Using Machine Learning,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1362, p. 012018, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Thabtah, “An accessible and efficient autism screening method for behavioural data and predictive analyses,” Health Informatics J., vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 1739–1755, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Omar, P. Mondal, N. S. Khan, Md. R. K. Rizvi, and M. N. Islam, “A Machine Learning Approach to Predict Autism Spectrum Disorder,” in 2019 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE), Cox’sBazar, Bangladesh: IEEE, Feb. 2019, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Klauck, “Genetics of autism spectrum disorder,” Eur. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 714–720, June 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. Mirkovic and P. Gérardin, “Asperger’s syndrome: What to consider?,” L’Encéphale, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 169–174, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Talkowski, E. V. Minikel, and J. F. Gusella, “Autism Spectrum Disorder Genetics: Diverse Genes with Diverse Clinical Outcomes,” Harv. Rev. Psychiatry, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 65–75, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Reji R1 and , Dr P SojanLal 2, “3D Facial Features in Neuro Fuzzy Model for Predictive Grading Of Childhood Autism,” Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. IJCSIS, vol. 15, no. 12, Dec. 2017, [Online]. Available: https://sites.google.com/site/ijcsis/ I.

- S. Roy, S. Sadhu, S. K. Bandyopadhyay, D. Bhattacharyya, and T.-H. Kim, “Brain Tumor Classification using Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System from MRI,” Int. J. Bio-Sci. Bio-Technol., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 203–218, June 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Anurekha and P. Geetha, “Evidence Based Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System for ASD Detection,” in 2018 3rd IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT), Bangalore, India: IEEE, May 2018, pp. 2188–2192. [CrossRef]

- M. Fitzgerald, “The Clinical Gestalts of Autism: Over 40 years of Clinical Experience with Autism,” in Autism - Paradigms, Recent Research and Clinical Applications, M. Fitzgerald and J. Yip, Eds., InTech, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Brugha et al., “Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Adults in the Community in England,” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 68, no. 5, p. 459, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Russell et al., “The mental health of individuals referred for assessment of autism spectrum disorder in adulthood: A clinic report,” Autism, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 623–627, July 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Woodbury-Smith and F. R. Volkmar, “Asperger syndrome,” Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 2–11, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Onu F. U.; Osisikankwu P. U.; Madubuike C. E.; James G. G., “Impacts of Object Oriented Programming on Web Application Development,” Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. Res., vol. 4, no. 9, pp. 706–710, 2015.

- R. Ahuja and D. Kaur, “Neuro-Fuzzy Methodology for Diagnosis of Autism,” vol. 5, 2014.

- G. G. James, A. E. Okpako, C. Ituma, and J. E. Asuquo, “Development of Hybrid Intelligent based Information Retreival Technique,” Int. J. Comput. Appl., vol. 184, no. 34, pp. 1–13, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G.G. James, A.E. Okpako, and J.N. Ndunagu, “Fuzzy cluster means algorithm for the diagnosis of confusable disease,” vol. 23, no. 1, Mar. 2017, [Online]. Available: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jcsia/article/view/153911.

- C. Ituma, G. G. James, and F. U. Onu, “Implementation of Intelligent Document Retrieval Model Using Neuro-Fuzzy Technology,” Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol., vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 65–74, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Ituma, G. G. James, and F. U. Onu, “A Neuro-Fuzzy Based Document Tracking & Classification System,” Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol., vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 414–423, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Ekong, G. G. James, and I. Ohaeri, “Oil and Gas Pipeline Leakage Detection using IoT and Deep Learning Algorithm,” J. Inf. Syst. Inform., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 421–434, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. G. James, A. E. Okpako, and C. O. Agwu, “Tention to use IoT technology on agricultural processes in Nigeria based on modified UTAUT model: perpectives of Nigerians’ farmers,” Sci. Afr., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 199–214, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. James, A. Ekong, E. Abraham, E. Oduobuk, and P. Okafor, “Analysis of support vector machine and random forest models for predicting the scalability of a broadband network,” 2024.

- Okafor, P. C., Ituma, C, James, G. G., “Implementation of a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) Based Cashless Vending Machine,” Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. Res., vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 90–98, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. C., J. G. G., and I. C., “Design of an Intelligent Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) Based Cashless Vending Machine for Sales of Drinks,” Br. J. Comput. Netw. Inf. Technol., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 36–57, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. P. Essien, G. G. James, and V. U. Ufford, “Technological impact assessment of Blockchain Technology on the synergism of decentralized exchange and pooled trading platform,” Int. J. Contemp. Afr. Res. Netw. Publ. Contemp. Afr. Res. Netw. CARN, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 152–165, 2024, doi: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.12103430.

- James, G. G., Asuquo, J. E., and Etim, E. O., “Adaptive Predictive Model for Post Covid’19 Health-Care Assistive Medication Adherence System,” in Contemporary Discourse on Nigeria’s Economic Profile A FESTSCHRIFT in Honour of Prof. Nyaudoh Ukpabio Ndaeyo on his 62nd Birthday, vol. 1, University of Uyo, Nigeria, 2023, pp. 622–631.

- U. James, G. G. U. A., U. Umoeka, Ini J. Edward N. ,., and Umoh, A. A., “Pattern Recognition System for the Diagnosis of Gonorrhea Disease,” Int. J. Dev. Med. Sci., vol. 3, no. 1 & 2, pp. 63–77, 2010.

- G. James, I. Umoren, A. Ekong, I. Ohaeri, and S. Inyang, “Real-Time Monitoring of Oil and Gas Pipeline Leakages Identification System Based on Deep Learning Approaches: A Systematic Review,” Mar. 14, 2025, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).