Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

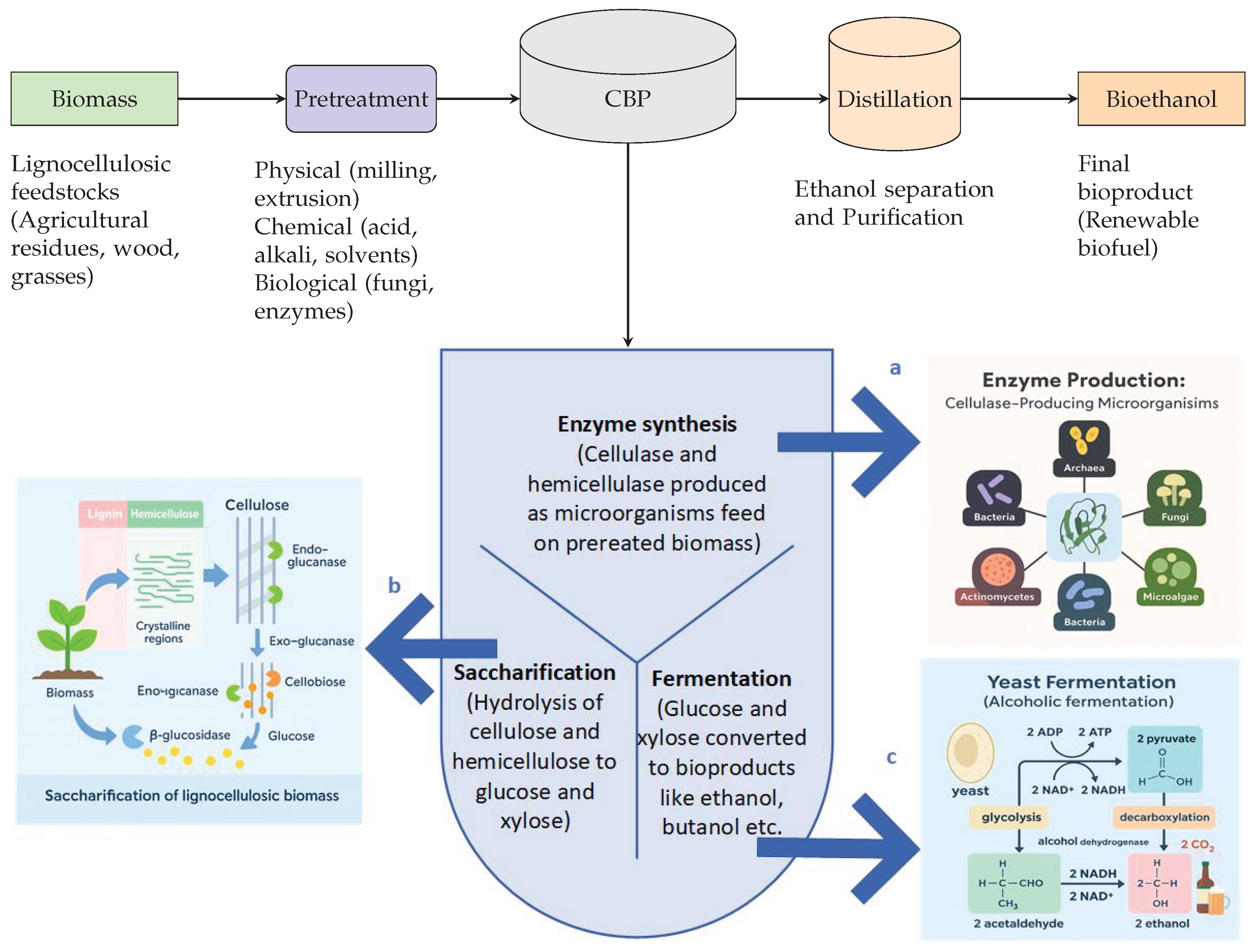

2. Research Advances in CBP for Bioproduction

2.1. Enzyme Synthesis

- Cellulase enzymes attach to the cellulose’s surface and adhere to it,

- Biotransformation of cellulose to fermentable sugars, and

- Desorption of cellulase.

| Enzymes | Specific types | Function | Microorganisms (Bacterial and Fungal Species) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulases | Endoglucanase (EG) | Breaks internal bonds in the cellulose chain, creating new chain ends. | Clostridium sp., T. reesei, Cellulomonas sp., T. viride, Thermomonospora sp., A. niger, Bacillus sp., P. helicum, Streptomyces sp., P. betulinus, R. flavefaciens, A. nidulans, Pedobacter sp., A. fumigatus, F. succinogenes, A. oryzae, R. albus, M. grisea, Mucilaginibacter sp., N. crassa, F. gramineum | [17,23,25,39,43] |

| -Glucosidase (BG) | Hydrolyzes cellobiose into glucose molecules. Works in synergy with cellulases and hemicellulases to ensure complete sugar release. | |||

| Exoglucanase (CBH) | Cleaves cellulose from the ends of the chains, releasing cellobiose. | |||

| Hemicellulases | Xylanases | Breaks down xylan (a major component of hemicellulose) by hydrolyzing -1,4-xylosidic bonds. Converts xylan into shorter oligosaccharides and xylooligosaccharides. | Bacillus sp., A. niger, P. bryantii, P. betulinus, R. flavefaciens, B. cinerea, P. xylanivorans, A. nidulans, F. succinogenes, A. fumigatus, R. albus, A. oryzae, B. succinogenes, M. grisea, Pedobacter sp., F. gramineum, Mucilaginibacter sp. | [9,20,33,37] |

| Endo--1,4-glucanase | Hydrolyzes random internal -1,4-glycosidic bonds in glucans, including cellulose and hemicellulose. Produces smaller oligosaccharides and enhances accessibility for other enzymes. | |||

| -Xylosidase | Cleaves -1,4-linked xylooligosaccharides into individual xylose units. Complements xylanase by breaking down shorter xylo-oligomers into simple sugars. | |||

| -Galactosidase | Hydrolyzes -1,6-linked galactose residues from galactomannans and other hemicelluloses. Removes side chains from mannans and arabinogalactans, making them easier to degrade. | |||

| Acetyl esterase | Removes acetyl groups from xylan and other hemicelluloses. Makes xylan more accessible to xylanases by breaking down ester linkages. | |||

| Mannanase | Breaks down mannans (a type of hemicellulose) by hydrolyzing -1,4-mannosidic bonds. Converts mannans into mannose and oligosaccharides. | |||

| Lignases | Laccase (LaC) | Oxidizes lignin using oxygen, creating radicals for degradation. | A. lipoferum, D. squalens, B. subtilis, G. applanatum, C. basilensis, T. reesei, R. ornithinolytica, T. longibrachiatum, Prevotella sp., M. tremellosus, Pseudomonas sp., P. chrysosporium, Pseudobutyrivibrio sp., C. subvermispora, P. cinnabarinus, Pleurotus sp., P. rivulosus, Pseudobutyrivibrio sp. | [30,31,41,42] |

| Lignin peroxidase (LiP) | Breaks down non-phenolic lignin structures using . | |||

| Manganese peroxidase (MnP) | Uses to degrade lignin and open aromatic rings. | |||

| Versatile peroxidase (VP) | Combines the functions of LiP and MnP to degrade lignin. |

2.2. Glucose production (hydrolysis)

2.3. Microbial fermentation

2.4. Challenges in sugar utilization and bio-product formation

2.5. Experimental approaches for optimizing CBP systems

| Microbial consortia | Substrate | Bioproduct | Yield/Productivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-culture of Clostridium beijerinckii and Clostridium cellulovorans | Alkali-extracted deshelled corn cobs | Acetone, butanol, ethanol (ABE) | 2.64 g/L acetone, 8.30 g/L butanol, 0.87 g/L ethanol; Productivity = 11.8 g/L of ABE solvents | [71] |

| T. reesei BCRC 31863, A. niger BCRC 3113, Z. mobilis BCRC 10809 | Carboxymethyl-cellulose | Bioethanol | Productivity = 0.56 g/L; Reducing sugar conversion = 11.2 % | [69] |

| Clostridium thermocellum and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum | Avicel | Bioethanol, acetate, lactate | Productivity = 38 g/L of bioethanol | [35] |

| Trichoderma reesei, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Scheffersomyces stipitis | Wheat straw | Bioethanol | Yield = 67 % | [36] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae and C. phytofermentans | -cellulose | Bioethanol | Productivity = 22 g/L bioethanol | [73] |

| Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana | -cellulose | Bioethanol | Yield = 15 % | [74] |

| Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium thermolacticum | Micro-crystallized cellulose (MCC) | Bioethanol | Yield = 75 % | [75] |

| Phlebia radiata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Waste lignocellulose material | Bioethanol | Productivity = 32.4 g/L | [56] |

| Acremonium cellulolyticus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Solka-Floc (SF) | Bioethanol | Concentration = 8.7– 46.3 g/L | [76] |

| Acetivibrio thermocellus and Thermoclostridium stercorarium | Mixture of cellulose and Xylan | Bioethanol | Concentration = 40.4 mM | [77] |

3. Review of recent modeling approaches for CBP

3.1. Polynomial Models

3.2. Response Surface Methodology

3.3. Machine Learning-Based Modeling of CBP

3.3.1. Regression Models

3.3.2. Neural Network Models

| Modeling Approach | Microorganisms | Substrate | Bioproduct | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSM | Hangateiclostridium thermocellum KSMK1203 and consortium of Cellulomonas fimi MTCC 24 and Zymomonas mobilis MTCC 92 | Pre-treated Allium ascalonicum leaves | Bioethanol | [37] | |

| Cellulomonas fimi MTCC 24 and Zymomonas mobilis MTCC 92 | Thermo-chemo pretreated Manihot esculenta Crantz YTP1 stem | Cellulase | , RMSE = 0.7943 | [102] | |

| Bioethanol | , RMSE = 1.0526 | ||||

| ANN | Cellulomonas fimi MTCC 24 and Zymomonas mobilis MTCC 92 | Thermo-chemo pretreated Manihot esculenta Crantz YTP1 stem | Cellulase | , RMSE = 0.5151 | [102] |

| Bioethanol | , RMSE = 0.6575 | ||||

| 18 different microorganisms | Secondary dataset with different cellulosic substrates | Bioethanol | , MSE = 2.529 | [95] | |

| Seeded synthetic dataset with different cellulosic substrates | Bioethanol | , MSE = 114.713 | |||

| GPR | 18 different microorganisms | Secondary dataset with different cellulosic substrates | Bioethanol | , RMSE = 0.2445 | [84] |

| Seeded synthetic dataset with different cellulosic substrates | Bioethanol | , RMSE = 1.826 | [95] |

3.4. Summary of the State of the Art in First-Order Principles and Data-Driven Modeling of CBP

| Criteria | First principle-based models | Data-driven models |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretability and mechanistic insight | ++ | − |

| Amount of data required | + | |

| Predictive accuracy under known conditions | ++ | + |

| Ability to update with new experimental results | − | ++ |

| Computational complexity | − | 0 |

| Handling multivariate interactions | 0 | ++ |

| Suitability for early-stage research | ++ | 0 |

| Need for system understanding | ++ | − |

| Ease of implementation | − | + |

| Model Type | Description and Potential Application in CBP |

|---|---|

| Deterministic models | Using ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to simulate microbial growth, enzyme production, substrate degradation, and product formation. Suitable for controlled systems and can help design predictive bioprocess control strategies. |

| Stochastic models | Incorporating random variables to account for biological noise and fluctuations in microbial behavior. Useful for microbial consortia, variability in feedstock composition, and uncertain process conditions. |

| Kinetic models (Monod, structured models) | Description of enzyme kinetics, microbial metabolism, and growth dynamics. Can be extended to include co-culture dynamics and substrate competition in CBP systems. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | Simulation of reactor hydrodynamics, mixing patterns, mass transfer, and heat exchange. Can be used to optimize large-scale CBP bioreactors and reduce process bottlenecks. |

| Multi-scale modeling | Integration of genome-scale metabolic models with process-level dynamics to understand intracellular fluxes and system behavior at different scales. Potentially useful to link metabolic engineering with reactor performance in CBP. |

| Hybrid models | Combination of mechanistic (first-principle) models with data-driven approaches like support vector machines or random forests to improve prediction accuracy and interpretability. Hybrid models are useful to predict CBP outcomes under novel feedstocks. |

| Reinforcement learning models | Utilizing reward-based algorithms to optimize process parameters dynamically. Can be applied to adaptive control of CBP processes, e.g., feeding strategies or environmental adjustments. |

| Evolutionary algorithms | Optimization techniques inspired by natural selection. Can be used to optimize multi-objective CBP process parameters, microbial community composition, or pathway design. |

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sebestyén, V. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: Environmental impact networks of renewable energy power plants. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 151, 111626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, B.; Markovska, N.; Puksec, T.; Duić, N.; Foley, A. Renewable and sustainable energy challenges to face for the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 157, 112071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Waghmare, P.R.; Dijkhuizen, L.; Meng, X.; Liu, W. Research advances on the consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass. Engineering Microbiology 2024, 4, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, E.; Dussap, C.G. First Generation Bioethanol: Fundamentals—Definition, History, Global Production, Evolution. In Liquid Biofuels: Bioethanol; Springer, 2022; pp. 1–12.

- De Almeida, M.A.; Colombo, R. Production chain of first-generation sugarcane bioethanol: characterization and value-added application of wastes. BioEnergy Research 2023, 16, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althuri, A.; Gujjala, L.K.S.; Banerjee, R. Partially consolidated bioprocessing of mixed lignocellulosic feedstocks for ethanol production. Bioresource Technology 2017, 245, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukas, T.; Kotzekidou, P. From food industry wastes to second generation bioethanol: a review. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2022, 21, 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Kit Chin, D.; Lim, S.; Pang, Y.L.; Lam, M.K. Fundamental review of organosolv pretreatment and its challenges in emerging consolidated bioprocessing. Biofuels, bioproducts and biorefining 2020, 14, 808–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olguin-Maciel, E.; Singh, A.; Chable-Villacis, R.; Tapia-Tussell, R.; Ruiz, H.A. Consolidated Bioprocessing, an Innovative Strategy towards Sustainability for Biofuels Production from Crop Residues: An Overview. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, D.; Xu, Y. Perspectives and advances in consolidated bioprocessing strategies for lignin valorization. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2024, 8, 1153–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonsamy, T.A.; Mandegari, M.; Farzad, S.; Görgens, J.F. A new insight into integrated first and second-generation bioethanol production from sugarcane. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 188, 115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K.; Singh, A.; Haldar, D.; Soam, S.; Chen, C.W.; Tsai, M.L.; Dong, C.D. Consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass: Technological advances and challenges. Bioresource Technology 2022, 354, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, S.; Beula Isabel, J.; Kavitha, S.; Karthik, V.; Mohamed, B.A.; Gizaw, D.G.; Sivashanmugam, P.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Recent advances in consolidated bioprocessing for conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into bioethanol – A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 453, 139783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, A.; Mazzoli, R. Current progress on engineering microbial strains and consortia for production of cellulosic butanol through consolidated bioprocessing. Microbial Biotechnology 2023, 16, 238–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupte, A.P.; Di Vita, N.; Myburgh, M.W.; Cripwell, R.A.; Basaglia, M.; van Zyl, W.H.; Viljoen-Bloom, M.; Casella, S.; Favaro, L. Consolidated bioprocessing of the organic fraction of municipal solid waste into bioethanol. Energy Conversion and Management 2024, 302, 118105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsa, G.; Konwarh, R.; Masi, C.; Ayele, A.; Haile, S. Microbial cellulase production and its potential application for textile industries. Annals of Microbiology 2023, 73, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, S.; Tong, X.; Liu, K. An overview on the current status and future prospects in Aspergillus cellulase production. Environmental Research 2024, 244, 117866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CareerPower. Anaerobic respiration: definition, equation and examples. https://www.careerpower.in/school/biology/anaerobic-respiration, 2024. Accessed: 26 September 2025.

- Kumar, V.; Ahluwalia, V.; Saran, S.; Kumar, J.; Patel, A.K.; Singhania, R.R. Recent developments on solid-state fermentation for production of microbial secondary metabolites: Challenges and solutions. Bioresource Technology 2021, 323, 124566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althuri, A.; Mohan, S.V. Sequential and consolidated bioprocessing of biogenic municipal solid waste: a strategic pairing of thermophilic anaerobe and mesophilic microaerobe for ethanol production. Bioresource technology 2020, 308, 123260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.D.; Sandri, J.P.; Claes, A.; Carvalho, B.T.; Thevelein, J.M.; Zangirolami, T.C.; Milessi, T.S. Effective application of immobilized second generation industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain on consolidated bioprocessing. New biotechnology 2023, 78, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Lu, M.; Jin, M.; Yang, S. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium cellulovorans to improve butanol production by consolidated bioprocessing. ACS synthetic biology 2020, 9, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Kumar, B.; Agrawal, K.; Verma, P. Current perspective on production and applications of microbial cellulases: a review. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 2021, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaar, L.; den Haan, R. Engineering natural isolates of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for consolidated bioprocessing of cellulosic feedstocks. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2023, 107, 7013–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhati, N.; Shreya.; Sharma, A.K. Cost-effective cellulase production, improvement strategies, and future challenges. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2021, 44, e13623. [CrossRef]

- Weimer, P.J. Degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose by ruminal microorganisms. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, A.; Silini, A.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Bouket, A.C.; Boudechicha, A.; Luptakova, L.; Alenezi, F.N.; Belbahri, L. Screening of cellulolytic bacteria from various ecosystems and their cellulases production under multi-stress conditions. Catalysts 2022, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Han, L.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Dai, Y.; Leng, J. Studies on the concerted interaction of microbes in the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants on lignocellulose and its degradation mechanism. Frontiers in Microbiology 2025, 16, 1554271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Jin, M.; Yang, S. Consolidated bioprocessing for butanol production of cellulolytic Clostridia: development and optimization. Microbial biotechnology 2020, 13, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, L.K.; Chaudhary, G. Advances in Biofeedstocks and Biofuels, Biofeedstocks and Their Processing; John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- Jiang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wu, R.; Lu, J.; Dong, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Consolidated bioprocessing performance of a two-species microbial consortium for butanol production from lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2020, 117, 2985–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, M.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Spatial niche construction of a consortium-based consolidated bioprocessing system. Green Chemistry 2022, 24, 7941–7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Srivastava, N.; Ramteke, P.W.; Mishra, P.K. Approaches to enhance industrial production of fungal cellulases; Springer, 2019; p. 200.

- Schlembach, I.; Hosseinpour Tehrani, H.; Blank, L.M.; Büchs, J.; Wierckx, N.; Regestein, L.; Rosenbaum, M.A. Consolidated bioprocessing of cellulose to itaconic acid by a co-culture of Trichoderma reesei and Ustilago maydis. Biotechnology for biofuels 2020, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyros, D.A.; Tripathi, S.A.; Barrett, T.F.; Rogers, S.R.; Feinberg, L.F.; Olson, D.G.; Foden, J.M.; Miller, B.B.; Lynd, L.R.; Hogsett, D.A.; et al. High Ethanol Titers from Cellulose by Using Metabolically Engineered Thermophilic, Anaerobic Microbes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 8288–8294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brethauer, S.; Studer, M.H. Consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulose by a microbial consortium. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S.; Gajendran, T.; Saranya, K.; Selvakumar, P.; Manivasagan, V.; Jeevitha, S. An insight - A statistical investigation of consolidated bioprocessing of Allium ascalonicum leaves to ethanol using Hangateiclostridium thermocellum KSMK1203 and synthetic consortium. Renewable Energy 2022, 187, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Deng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, L. Distributive and collaborative push-and-pull in an artificial microbial consortium for improved consolidated bioprocessing. AIChE Journal 2022, 68, e17844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, R.L.; Luterbacher, J.S.; Brethauer, S.; Studer, M.H. Consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass to lactic acid by a synthetic fungal-bacterial consortium. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2018, 115, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Kumar, V.; Prasad, R.; Gaur, N.A. Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a consolidated bioprocessing host to produce cellulosic ethanol: Recent advancements and current challenges. Biotechnology Advances 2022, 56, 107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagide, C.; Castro-Sowinski, S. Technological and biochemical features of lignin-degrading enzymes: a brief review. Environmental Sustainability 2020, 3, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiwesh, G.; Parrish, C.C.; Banoub, J.; Le, T.A.T. Lignin degradation by microorganisms: A review. Biotechnology Progress 2022, 38, e3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, J.; Ishizue, N.; Ishizaki, M.; Yasuda, M.; Takahashi, K.; Ninomiya, K.; Yamada, R.; Kondo, A.; Ogino, C. Development and evaluation of consolidated bioprocessing yeast for ethanol production from ionic liquid-pretreated bagasse. Bioresource Technology 2017, 245, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.T.; Romaní, A.; Inokuma, K.; Johansson, B.; Hasunuma, T.; Kondo, A.; Domingues, L. Consolidated bioprocessing of corn cob-derived hemicellulose: engineered industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae as efficient whole cell biocatalysts. Biotechnology for biofuels 2020, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Fong, S.S. Challenges and advances for genetic engineering of non-model bacteria and uses in consolidated bioprocessing. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banner, A.; Toogood, H.S.; Scrutton, N.S. Consolidated bioprocessing: synthetic biology routes to fuels and fine chemicals. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Pan, X. Insights into solid acid catalysts for efficient cellulose hydrolysis to glucose: progress, challenges, and future opportunities. Catalysis Reviews 2022, 64, 445–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N.K.; Ernawati, D.; Sari, K.N. Optimization of Glucose from Saccaromycess cerevicae Liquid Waste Using the Acid Hydrolysis Process. Nusantara Science and Technology Proceedings, 2024; 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, M.; Xu, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Dong, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Consolidated Bioprocessing of Hemicellulose-Enriched Lignocellulose to Succinic Acid through a Microbial Cocultivation System. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, B.; Feng, Y.; Cui, Q. Consolidated bio-saccharification: Leading lignocellulose bioconversion into the real world. Biotechnology Advances 2020, 40, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, B.; Gu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Liu, D.; Sun, W.; et al. Coordination of consolidated bioprocessing technology and carbon dioxide fixation to produce malic acid directly from plant biomass in Myceliophthora thermophila. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempfle, D.; Kröcher, O.; Studer, M.H.P. Techno-economic assessment of bioethanol production from lignocellulose by consortium-based consolidated bioprocessing at industrial scale. New biotechnology 2021, 65, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Chen, J.; Gong, Z.; Xu, Q.; Yue, W.; Xie, H. Dissolution pretreatment of cellulose by using levulinic acid-based protic ionic liquids towards enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 269, 118271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Fox, B.G.; Takasuka, T.E. Consolidated bioprocessing of plant biomass to polyhydroxyalkanoate by co-culture of Streptomyces sp. SirexAA-E and Priestia megaterium. Bioresource Technology 2023, 376, 128934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.L.; Sun, Q.; Chen, W. Advances in consolidated bioprocessing using synthetic cellulosomes. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2022, 78, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, H.; Kačar, D.; Mali, T.; Lundell, T. Lignocellulose bioconversion to ethanol by a fungal single-step consolidated method tested with waste substrates and co-culture experiments. AIMS Energy 2018, 6, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, R. Current progress in production of building-block organic acids by consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulose. Fermentation 2021, 7, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Saini, H.; Thakur, B.; Soni, R.; Soni, S.K. Consolidated bioprocessing of biodegradable municipal solid waste for transformation into biofertilizer formulations. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14, 20923–20937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wu, M.; Bao, H.; Liu, W.; Shen, Y. Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for co-fermentation of glucose and xylose: current state and perspectives. Engineering Microbiology 2023, 3, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulos, V.; Boura, K.; Dima, A.; Karabagias, I.K.; Bosnea, L.; Nigam, P.S.; Kanellaki, M.; Koutinas, A.A. Consolidated bioprocessing of lactose into lactic acid and ethanol using non-engineered cell factories. Bioresource Technology 2022, 345, 126464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.J.; Xia, Z.Y.; Yang, B.X.; Tang, Y.Q. Improving acetic acid and furfural resistance of xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains by regulating novel transcription factors revealed via comparative transcriptomic analysis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2021, 87, e00158–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavana, B.K.; Mudliar, S.N.; Bokade, V.; Debnath, S. Effect of furfural, acetic acid and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on yeast growth and xylitol fermentation using Pichia stipitis NCIM 3497. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14, 4909–4923. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Gupta, A.; Mathur, A.S.; Barrow, C.; Puri, M. Integrated consolidated bioprocessing for simultaneous production of Omega-3 fatty acids and bioethanol. Biomass and bioenergy 2020, 137, 105555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Peled, L.; Kory, N. Principles and functions of metabolic compartmentalization. Nature metabolism 2022, 4, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Kovalev, A.A.; Zhuravleva, E.A.; Pareek, N.; Vivekanand, V. Enhanced production of acetic acid through bioprocess optimization employing response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Bioresource Technology 2023, 376, 128930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breig, S.J.M.; Luti, K.J.K. Response surface methodology: A review on its applications and challenges in microbial cultures. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 42, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, T.; Vázquez, D.; Müller, C.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Machine learning uncovers analytical kinetic models of bioprocesses. Chemical Engineering Science 2024, 300, 120606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Singh, V. A consolidated bioprocess design to produce multiple high-value platform chemicals from lignocellulosic biomass and its technoeconomic feasibility. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 377, 134383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.K.; Yang, C.A.; Chen, W.C.; Wei, Y.H. Producing bioethanol from cellulosic hydrolyzate via co-immobilized cultivation strategy. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2012, 114, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.G.; McBride, J.E.; Shaw, A.J.; Lynd, L.R. Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Current opinion in biotechnology 2012, 23, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Wu, M.; Lin, Y.; Yang, L.; Lin, J.; Cen, P. Artificial symbiosis for acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation from alkali extracted deshelled corn cobs by co-culture of Clostridium beijerinckii and Clostridium cellulovorans. Microbial cell factories 2014, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbaneme-Smith, V.; Chinn, M.S. Consolidated bioprocessing for biofuel production: recent advances. Energy and Emission Control Technologies 2015, 3, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuroff, T.R.; Xiques, S.B.; Curtis, W.R. Consortia-mediated bioprocessing of cellulose to ethanol with a symbiotic Clostridium phytofermentans/yeast co-culture. Biotechnology for biofuels 2013, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Alkotaini, B.; Salunke, B.K.; Deshmukh, A.R.; Saha, P.; Kim, B.S. Direct ethanol production from cellulose by consortium of Trichoderma reesei and Candida molischiana. Green Processing and Synthesis 2019, 8, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tschirner, U. Improved ethanol production from various carbohydrates through anaerobic thermophilic co-culture. Bioresource technology 2011, 102, 10065–10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.Y.; Naruse, K.; Kato, T. One-pot bioethanol production from cellulose by co-culture of Acremonium cellulolyticus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2012, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yan, Z.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C. Synergy of Cellulase Systems between Acetivibrio thermocellus and Thermoclostridium stercorarium in Consolidated-Bioprocessing for Cellulosic Ethanol. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Wu, Q.; Shapiro, B.M.; McKernan, S.E. Limited mechanistic link between the Monod equation and methanogen growth: a perspective from metabolic modeling. Microbiology spectrum 2022, 10, e02259–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Bi, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Lv, X.; Liu, L. Artificial intelligence technologies in bioprocess: Opportunities and challenges. Bioresource Technology 2023, 369, 128451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadino-Riquelme, M.; Donoso-Bravo, A.; Zorrilla, F.; Valdebenito-Rolack, E.; Gómez, D.; Hansen, F. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling applied to biological wastewater treatment systems: An overview of strategies for the kinetics integration. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 466, 143180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.K.; Tarafdar, A.; You, S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for smart bioprocesses. Bioresource Technology 2023, 375, 128826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhuvanthi, S.; Jayanthi, S.; Suresh, S.; Pugazhendhi, A. Optimization of consolidated bioprocessing by response surface methodology in the conversion of corn stover to bioethanol by thermophilic Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Johnson, W.; Valderrama-Gomez, M.A.; Icten, E.; Tat, J.; Ingram, M.; Shek, C.F.; Chan, P.K.; Schlegel, F.; Rolandi, P.; et al. COSMIC-dFBA: A novel multi-scale hybrid framework for bioprocess modeling. Metabolic Engineering 2024, 82, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, M.K.; Asiedu, N.Y.; Dogbe, S.; Addo, A. Performance of Machine Learning Based-Modelling Approach in Consolidated Bioprocessing with Microbial Consortium for Bioethanol Production. Industrial Biotechnology 2024, 20, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempfle, D.B. Model-based scale-up of a continuously operated consolidated bioprocess based on a microbial consortium for the production of ethanol. PhD thesis, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), 2022. https://infoscience.epfl.ch/bitstreams/89988351-e1ca-4306-994f-ab1b209478b0/download.

- Rendón-Castrillón, L.; Ramírez-Carmona, M.; Ocampo-López, C.; Gómez-Arroyave, L. Mathematical model for scaling up bioprocesses using experiment design combined with Buckingham Pi theorem. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangipudi, S.; Reddy, D.G.V.; Ranganathan, P. Computational tools in bioprocessing. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 211–231.

- Agharafeie, R.; Ramos, J.R.C.; Mendes, J.M.; Oliveira, R. From Shallow to Deep Bioprocess Hybrid Modeling: Advances and Future Perspectives. Fermentation 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, B. Hybrid modeling in bioprocess dynamics: Structural variabilities, implementation strategies, and practical challenges. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2023, 120, 2072–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ma, A.; Zhuang, G. Construction of environmental synthetic microbial consortia: based on engineering and ecological principles. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 829717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelgalil, S.; Soliman, N.; Abo-Zaid, G.; Abdel-Fattah, Y. Bioprocessing strategies for cost-effective large-scale production of bacterial laccase from Lysinibacillus macroides LSO using bio-waste. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 2021; 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman, V.; Johnrajan, J.; Yazhini, K.; Rathinasabapathi, P. Bioprocess engineering essentials: cultivation strategies and mathematical modeling techniques. In Industrial microbiology and biotechnology: a new horizon of the microbial world; Springer, 2024; pp. 247–276.

- de Andrade Bustamante, R.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Dos Santos, B.F. Modeling biosurfactant production from agroindustrial residues by neural networks and polynomial models adjusted by particle swarm optimization. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 6466–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, J.F.C.; dos Reis, B.D.; de Baptista Neto, Á.; Lerin, L.A.; de Oliveira, J.V.; de Paula, A.V.; Remonatto, D. Comparing a polynomial DOE model and an ANN model for enhanced geranyl cinnamate biosynthesis with Novozym® 435 lipase. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 58, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, M.K. Modelling of Consolidated Bioprocessing for Bioethanol Production: Encoded Microbial Consortium for Machine Learning. Master thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, 2024.

- Monteiro, M.; Fadda, S.; Kontoravdi, C. Towards advanced bioprocess optimization: A multiscale modelling approach. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2023, 21, 3639–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, C.M.; Zhang, Q.; Daoutidis, P.; Hu, W.S. A hybrid mechanistic-empirical model for in silico mammalian cell bioprocess simulation. Metabolic Engineering 2021, 66, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafrakidou, P.; Manthos, G.; Zagklis, D.; Mema, J.; Kornaros, M. Assessment of substrate load and process pH for bioethanol production–Development of a kinetic model. Fuel 2022, 313, 123007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgalil, S.A.; Soliman, N.A.; Abo-Zaid, G.A.; Abdel-Fattah, Y.R. Dynamic consolidated bioprocessing for innovative lab-scale production of bacterial alkaline phosphatase from Bacillus paralicheniformis strain APSO. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djimtoingar, S.S.; Derkyi, N.S.A.; Kuranchie, F.A.; Yankyera, J.K. A review of response surface methodology for biogas process optimization. Cogent Engineering 2022, 9, 2115283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, S.; Sharma, S.; Dutt, H.C.; Mahajan, R.; Bajaj, B.K. One pot consolidated bioprocess for conversion of Saccharum spontaneum biomass to ethanol-biofuel. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 250, 114880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, P.; Kavitha, S.; Sivashanmugam, P. Optimization of process parameters for efficient bioconversion of thermo-chemo pretreated Manihot esculenta Crantz YTP1 stem to ethanol. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 2177–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.P.; Galodha, A.; Verma, V.K.; Singh, V.; Show, P.L.; Awasthi, M.K.; Lall, B.; Anees, S.; Pollmann, K.; Jain, R. Review on machine learning-based bioprocess optimization, monitoring, and control systems. Bioresource technology 2023, 370, 128523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzak, S.A.; Alam, M.S.; Hossain, S.Z.; Rahman, S.M. Tree-based machine learning for predicting Neochloris oleoabundans biomass growth and biological nutrient removal from tertiary municipal wastewater. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2024, 210, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Bermúdez, L.M. Bioprocesses in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Revista Colombiana de Biotecnología 2025, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong-Trung, N.; Born, S.; Kim, J.W.; Schermeyer, M.T.; Paulick, K.; Borisyak, M.; Cruz-Bournazou, M.N.; Werner, T.; Scholz, R.; Schmidt-Thieme, L.; et al. When bioprocess engineering meets machine learning: A survey from the perspective of automated bioprocess development. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2023, 190, 108764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleckes, L.M.; Hemmerich, J.; Wiechert, W.; von Lieres, E.; Grünberger, A. Machine learning in bioprocess development: from promise to practice. Trends in biotechnology 2023, 41, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baako, T.M.D.; Kulkarni, S.K.; McClendon, J.L.; Harcum, S.W.; Gilmore, J. Machine learning and deep learning strategies for Chinese hamster ovary cell bioprocess optimization. Fermentation 2024, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, V.V.; Pappa, N.; Rani, S.J.V. Deep learning based soft sensor for bioprocess application. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE second international conference on control, measurement and instrumentation (CMI). IEEE; 2021; pp. 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Imamoglu, E. Artificial Intelligence and/or Machine Learning Algorithms in Microalgae Bioprocesses. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singhal, B. Role of machine learning in bioprocess engineering: current perspectives and future directions. Design and Applications of Nature Inspired Optimization: Contribution of Women Leaders in the Field, 2023; 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Kurian, V.; Ogunnaike, B.A. Bioprocess systems analysis, modeling, estimation, and control. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering 2021, 33, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable ai: A review of machine learning interpretability methods. Entropy 2020, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.W.; Song, Z.; Ramon, F.V.; Jing, K.; Zhang, D. Investigating ‘greyness’ of hybrid model for bioprocess predictive modelling. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2023, 190, 108761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agharafeie, R.; Oliveira, R.; Ramos, J.R.C.; Mendes, J.M. Application of hybrid neural models to bioprocesses: A systematic literature review. Authorea Preprints 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Agharafeie, R.; Ramos, J.R.C.; Mendes, J.M.; Oliveira, R. From shallow to deep bioprocess hybrid modeling: Advances and future perspectives. Fermentation 2023, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.T.; Kristiani, E.; Leong, Y.K.; Chang, J.S. Big data and machine learning driven bioprocessing–recent trends and critical analysis. Bioresource technology 2023, 372, 128625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, P.P.; Soares, E.A.; Jiang, R.; Arnold, N.I.; Atkinson, P.M. Explainable artificial intelligence: an analytical review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2021, 11, e1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Rad, P. Opportunities and challenges in explainable artificial intelligence (xai): A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.11371, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Granrose, D.; Jones, A.; Loftus, H.; Tandeski, T.; Heaton, W.; Foley, K.T.; Silverman, L. Design of experiment (DOE) applied to artificial neural network architecture enables rapid bioprocess improvement. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering 2021, 44, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B. A guide to the Michaelis–Menten equation: steady state and beyond. The FEBS journal 2022, 289, 6086–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.J.; Guo, L.; Morgan, J.; Schwender, J. Modeling plant metabolism: from network reconstruction to mechanistic models. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2020, 71, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, H.; Luna, M.F.; von Stosch, M.; Cruz Bournazou, M.N.; Polotti, G.; Morbidelli, M.; Butté, A.; Sokolov, M. Bioprocessing in the digital age: the role of process models. Biotechnology journal 2020, 15, 1900172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, S. Machine Learning and Deep Learning methods for predictive modelling from Raman spectra in bioprocessing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.02935, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nazemzadeh, N.; Malanca, A.A.; Nielsen, R.F.; Gernaey, K.V.; Andersson, M.P.; Mansouri, S.S. Integration of first-principle models and machine learning in a modeling framework: An application to flocculation. Chemical Engineering Science 2021, 245, 116864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, G.; Kocbek, P.; Fijacko, N.; Zitnik, M.; Verbert, K.; Cilar, L. Interpretability of machine learning-based prediction models in healthcare. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2020, 10, e1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M. Against interpretability: a critical examination of the interpretability problem in machine learning. Philosophy & Technology 2020, 33, 487–502. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H. Application of Big Data Analysis in Intelligent Industrial Design Using Scalable Computational Model. Scalable Computing: Practice and Experience 2025, 26, 1180–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoko, K.; Cordiner, J.L.; Kis, Z.; Moghadam, P.Z. Bioprocessing 4.0: a pragmatic review and future perspectives. Digital Discovery 2024, 3, 1662–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wan, M.P.; Chen, W.; Ng, B.F.; Dubey, S. Model predictive control with adaptive machine-learning-based model for building energy efficiency and comfort optimization. Applied Energy 2020, 271, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.K.; Ayankoso, S.A.; Nagata, F. Data-driven modeling: concept, techniques, challenges and a case study. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE international conference on mechatronics and automation (ICMA). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1000–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.Q. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14608, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Penloglou, G.; Kiparissides, A. Advanced Modeling of Biomanufacturing Processes. Processes 2024, 12, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).