1. Introduction

Heart failure remains a leading global cause of morbidity and mortality, with its prevalence steadily increasing due to aging populations and persistent cardiovascular risk factors [

1]. Among its etiologies, pressure overload—typically arising from hypertension or aortic stenosis—initiates maladaptive cardiac remodeling marked by left ventricular hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and progressive functional decline [

2,

3]. These structural alterations are driven by intricate molecular pathways involving oxidative stress, inflammation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, ultimately impairing myocardial compliance and contractility [

4]. Despite advances in pharmacological and device-based therapies, current interventions often fail to reverse established fibrosis or restore myocardial architecture [

5]. This therapeutic limitation highlights the need for novel strategies that target the underlying molecular mechanisms of remodeling. Marine-derived compounds such as fucoidan have emerged as promising candidates, owing to their multifaceted bioactivities—including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic properties [

6,

7,

8]. Previous studies have shown that fucoidan suppresses galectin-3 secretion and attenuates fibrosis in pressure overload models [

9], motivating further investigation into its proteomic effects on cardiac tissue.

Cardiac remodeling induced by pressure overload involves a multifaceted network of molecular pathways that progressively impair myocardial structure and function. Inflammation plays a pivotal role, as activated immune cells and cytokine cascades stimulate fibroblast activation and ECM expansion [

2,

4]. Oxidative stress further exacerbates tissue injury by generating reactive oxygen species that compromise mitochondrial integrity and initiate apoptotic signaling [

7,

10]. Excessive ECM deposition, particularly collagen accumulation, increases myocardial stiffness and contributes to diastolic dysfunction. This fibrotic process is regulated by profibrotic mediators such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and matrix metalloproteinases, which coordinate ECM turnover and remodeling [

9]. Simultaneously, mitochondrial dysfunction—characterized by impaired bioenergetics, disrupted iron-sulfur cluster assembly, and altered oxidative phosphorylation—diminishes cardiomyocyte viability and contractile performance [

11,

12]. Galectin-3, a β-galactoside-binding lectin secreted by activated macrophages and fibroblasts, has emerged as a key biomarker and effector in cardiac fibrosis and inflammation. Elevated galectin-3 levels are associated with adverse outcomes in heart failure and have been shown to promote fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and proinflammatory signaling [

6,

8,

13]. Previous studies have demonstrated that fucoidan suppresses galectin-3 secretion and attenuates fibrosis in pressure overload models, underscoring its therapeutic potential [

9].

Marine ecosystems have produced a diverse array of bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential, among which fucoidan—a sulfated polysaccharide extracted from brown algae such as

Fucus vesiculosus,

Laminaria japonica, and

Sargassum species—has gained prominence for its pleiotropic biological activities [

7,

13,

14]. Structurally defined by a fucose backbone and variable sulfate content, fucoidan exhibits potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antifibrotic effects across a range of disease models, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and oncologic conditions [

6,

15,

16]. Recent studies have shown that fucoidan modulates immune responses, suppresses oxidative stress, and regulates extracellular matrix turnover—key processes implicated in tissue remodeling [

17,

18]. Its cardioprotective effects have been linked to the attenuation of mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibition of proinflammatory signaling, and restoration of endothelial integrity [

10,

19]. In our previous investigation using a murine transverse aortic constriction (TAC) model, fucoidan administration significantly reduced left ventricular hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Mechanistically, this improvement was associated with downregulation of galectin-3, a macrophage-derived lectin known to promote fibroblast activation and collagen deposition [

9]. These findings support the hypothesis that fucoidan mitigates pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling by targeting molecular drivers of inflammation and fibrosis.

Although fucoidan has demonstrated cardioprotective effects in preclinical models—including reduced fibrosis, suppressed galectin-3 secretion, and preserved cardiac function under pressure overload—its molecular targets remain incompletely defined [

8,

9]. Most existing studies have emphasized functional or histological outcomes, leaving a critical gap in our understanding of the intracellular signaling networks and protein-level changes that mediate its therapeutic effects [

6,

7,

17]. Given the complexity of cardiac remodeling—which involves dynamic crosstalk among metabolic enzymes, structural proteins, and inflammatory mediators—high-resolution molecular profiling is essential. Unbiased, high-throughput techniques such as liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enable systematic identification of differentially expressed proteins and pathway-level perturbations in response to treatment [

3,

11,

21]. Proteomic analysis not only facilitates the discovery of novel therapeutic targets but also offers mechanistic insights into how fucoidan modulates mitochondrial function, translational machinery, and extracellular matrix organization—domains often overlooked in conventional assays. To date, few studies have applied proteomics to investigate marine-derived compounds in cardiovascular disease models, underscoring the need for integrative omics strategies to elucidate fucoidan’s molecular mechanisms and support its development as a targeted therapeutic agent.

Proteomic technologies have become essential for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac remodeling. Among these, LC-MS/MS enables high-throughput, quantitative profiling of thousands of proteins within cardiac tissue, offering detailed insights into disease-associated alterations in signaling pathways, metabolic networks, and structural components [

3,

11,

21]. This approach has been successfully employed to differentiate proteomic signatures between hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic stenosis [

3], to characterize remodeling induced by pressure overload in murine models [

11], and to identify biomarkers of pathological hypertrophy through integrative proteogenomic analysis [

21]. Beyond global protein quantification, cell-type-specific proteomic profiling—such as isolating fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched fractions—provides critical resolution into the compartmentalized responses that drive cardiac pathology. Fibroblasts contribute to extracellular matrix deposition and inflammatory signaling, while cardiomyocytes undergo metabolic reprogramming and structural adaptation. Dissecting these distinct cellular contributions enhances mechanistic understanding and informs the development of targeted interventions. In the context of marine-derived therapeutics such as fucoidan, proteomic analysis offers a powerful platform to uncover novel molecular targets and clarify how these compounds modulate remodeling dynamics at both cellular and systems levels.

This study aimed to characterize proteomic alterations induced by fucoidan treatment in a murine model of pressure overload, using TAC to simulate pathological cardiac remodeling. Although previous investigations have shown that fucoidan attenuates fibrosis, suppresses galectin-3 secretion, and improves cardiac function [

9], its molecular targets and cell-specific effects remain insufficiently defined. To address this gap, we integrated echocardiographic evaluation, histological analysis, and LC-MS/MS-based proteomic profiling of left ventricular tissue. This multi-tiered approach enabled the identification of differentially expressed proteins across fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched fractions, offering mechanistic insights into fucoidan’s therapeutic actions. Proteomic data revealed consistent modulation of mitochondrial enzymes, ribosomal subunits, and cytoskeletal proteins in fucoidan-treated TAC (TAC-FO) mice compared to untreated TAC controls, suggesting restoration of metabolic and structural homeostasis. These findings align with prior reports of mitochondrial dysfunction and translational dysregulation in pressure overload models [

11,

12,

21], and underscore fucoidan’s potential to reverse key molecular features of cardiac remodeling. By integrating functional, histological, and proteomic endpoints, this study provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating marine-derived bioactives in cardiovascular disease.

2. Results

2.1. Fibroblast-Enriched Fraction

Proteomic analysis of fibroblast-enriched left ventricular tissue from TAC-FO mice revealed a reversal of pressure overload-induced suppression across key functional domains, including metabolism, protein synthesis, structural integrity, and mitochondrial function.

• Metabolic and Energy-Related Proteins: Fucoidan significantly upregulated enzymes central to mitochondrial energy metabolism, such as lipoamide acyltransferase (P53395), alpha-enolase (P17182), glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (P06745), and methanethiol oxidase (P17563). These proteins are involved in branched-chain amino acid catabolism, glycolysis, and redox regulation—pathways commonly disrupted in pressure overload models [

11,

12]

• Protein Synthesis and Post-Translational Modification: Ribosomal subunits including receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1; P68040), mitochondrial ribosomal protein L49 (mL49; Q9CQ40), and ribosomal protein S11 (uS11; P62264) were restored, alongside tRNA-modifying enzymes and methyltransferases. These changes suggest recovery of translational capacity, consistent with prior reports of ribosomal dysfunction in hypertrophic myocardium [

21].

• Structural and Cytoskeletal Proteins: Fucoidan enhanced the expression of beta-actin-like protein 2 (Q8BFZ3), laminin gamma-1 (F8VQJ3), and collagen alpha-2(VI) chain (Q02788), supporting cytoskeletal stabilization and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. Notably, gamma-sarcoglycan (P82348) was downregulated in TAC-FO versus TAC, indicating reversal of maladaptive structural changes [

2].

• Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Import Machinery: Proteins involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and import—including frataxin (O35943), translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane domain-containing protein 1 (TIMMDC1; Q8BUY5), translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 homolog B (TOM40B; Q9CZR3), and iron-sulfur cluster assembly factors—were elevated, reflecting improved organelle integrity and metabolic competence [

10,

12].

• Signal Transduction and Regulatory Proteins: Restoration of NOD-like receptor family member X1 (Q3TL44), quinone oxidoreductase (P47199), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α)/estrogen-related receptor (ERR)-induced regulators suggests that fucoidan modulates inflammatory and oxidative signaling pathways, consistent with its known anti-inflammatory properties [

6,

9].

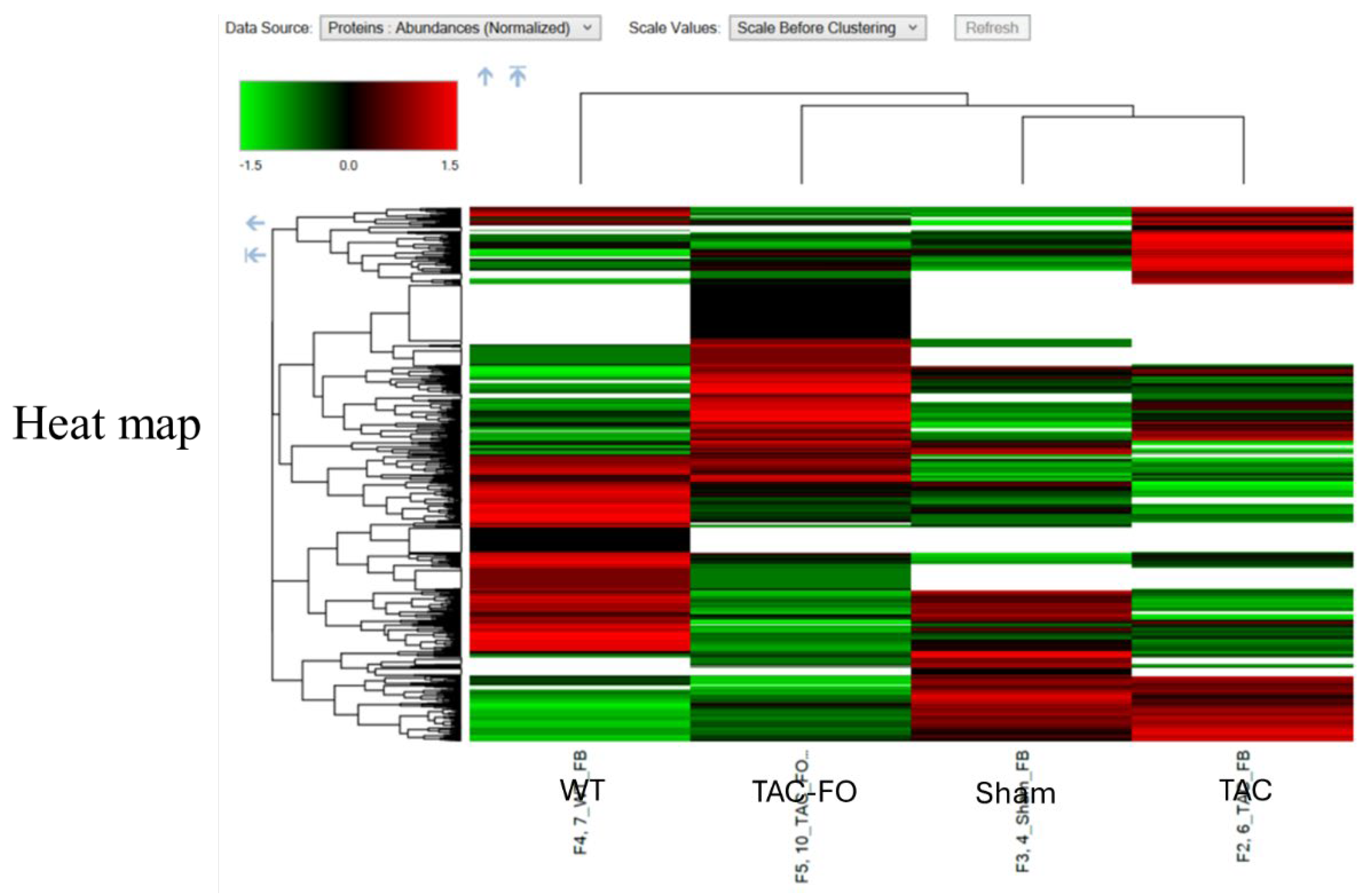

These proteomic changes are visualized in

Figure 1, which presents a heatmap of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) across wild-type (WT), sham-operated (Sham), TAC, and TAC-FO groups. Unsupervised clustering highlights partial restoration of protein expression patterns in fucoidan-treated mice toward baseline levels. To further contextualize these findings, Table 1 categorizes DEPs by biological function, including components of protein synthesis, mitochondrial activity, and regulatory pathways. This functional classification underscores fucoidan’s capacity to enhance translational machinery and mitochondrial integrity, reinforcing its role in reversing pressure overload-induced remodeling.

2.2. Myocyte-Enriched Fraction

Proteomic alterations in cardiomyocyte-enriched left ventricular tissue closely mirrored those observed in fibroblast fractions, reinforcing fucoidan’s broad cellular impact across key functional domains.

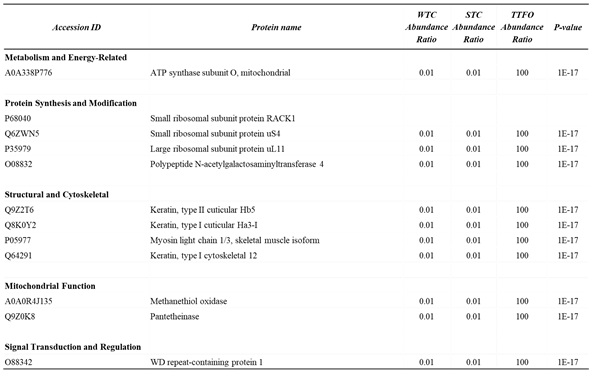

• Energy Metabolism: Fucoidan treatment significantly upregulated ATP synthase subunit O (A0A338P776) and methanethiol oxidase (A0A0R4J135), indicating enhanced mitochondrial ATP production and redox regulation.

• Protein Synthesis and Modification: Increased abundance of ribosomal protein S4 (uS4; Q6ZWN5), ribosomal protein L11 (uL11; P35979), and glycosyltransferase (O08832) suggests recovery of translational and post-translational machinery, consistent with restored biosynthetic capacity.

• Structural Integrity: Expression of keratin isoforms (Q9Z2T6, Q8K0Y2, Q64291) and myosin light chain 1/3 (P05977) was restored toward baseline levels, reflecting improved cytoskeletal organization and contractile function.

• Mitochondrial and Regulatory Proteins: Elevation of pantetheinase (Q9Z0K8) and WD repeat-containing protein 1 (O88342) in TAC-FO mice implicates fucoidan in the modulation of mitochondrial lipid metabolism and intracellular signaling pathways.

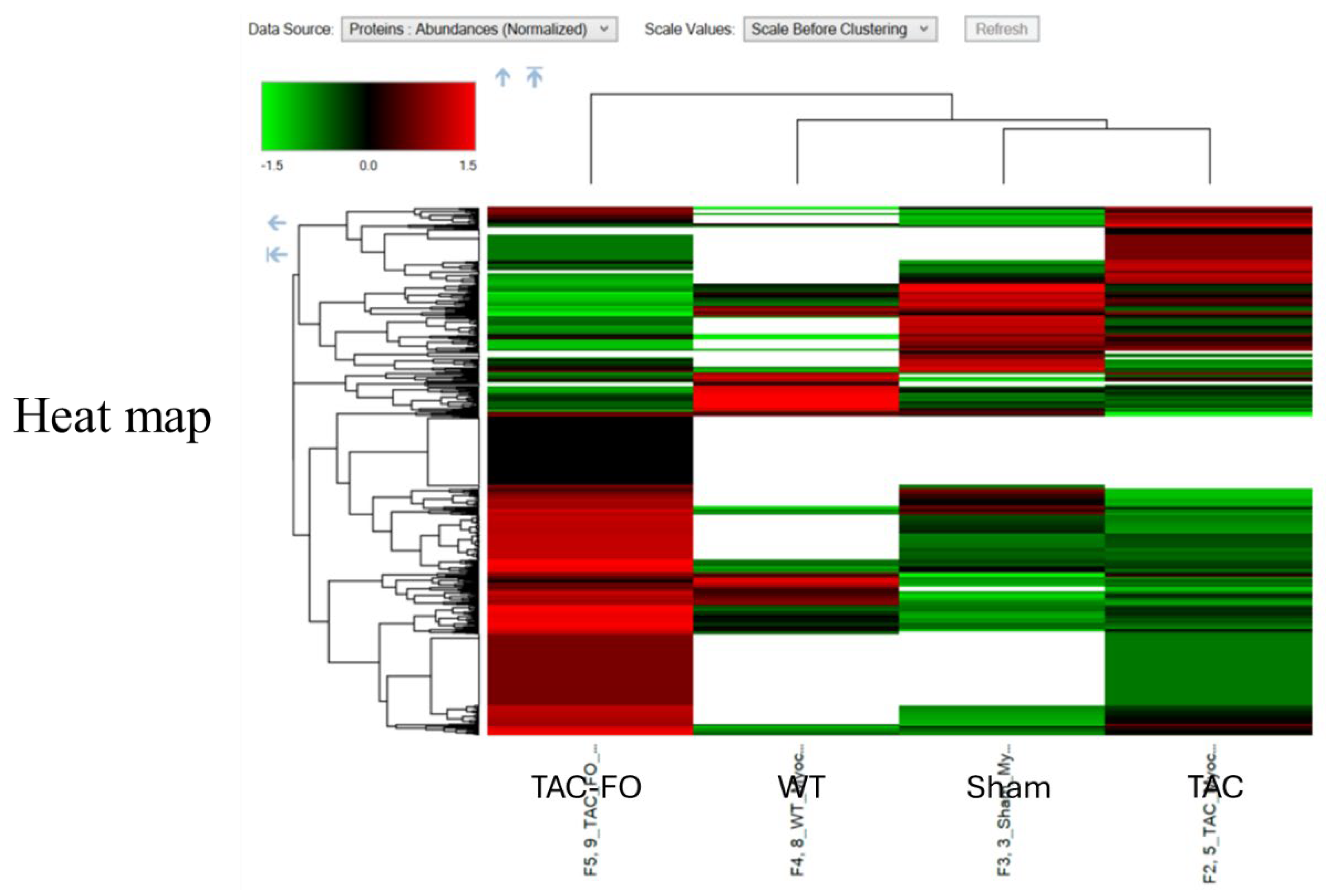

These proteomic trends are visualized in

Figure 2, which presents a heatmap of DEPs in cardiomyocyte-enriched tissue across WT, Sham, TAC, and TAC-FO groups. The normalization of protein expression in TAC-FO hearts reflects fucoidan’s restorative effects on mitochondrial, translational, and structural domains.

Table 2 complements this visualization by categorizing DEPs according to biological function, including metabolism, protein synthesis, cytoskeletal organization, and signal transduction. The consistent upregulation of mitochondrial and structural proteins further supports fucoidan’s role in reversing cardiomyocyte dysfunction under pressure overload.

Curated list of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in cardiomyocyte-enriched left ventricular tissue comparing TAC and TAC-FO mice. Proteins are grouped by biological function, including metabolism and energy-related enzymes (e.g., ATP synthase subunit O), components of protein synthesis and modification (e.g., ribosomal proteins RACK1, S20, L23a, and glycosyltransferase), structural and cytoskeletal proteins (e.g., keratin isoforms, myosin light chain 1/3), mitochondrial function markers (e.g., methanethiol oxidase, peroxiredoxin-3), and signal transduction regulators (e.g., WD repeat-containing protein 1). Each entry includes protein accession ID, abundance ratios across experimental comparisons, and P values.

2.3. Summary of Proteomic Trends

Fucoidan treatment elicited coordinated molecular restoration across both fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched fractions in TAC mice. Mitochondrial enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, branched-chain amino acid metabolism, and redox regulation, such as lipoamide acyltransferase, alpha-enolase, and methanethiol oxidase, were consistently upregulated, indicating reversal of pressure overload-induced metabolic suppression. Ribosomal subunits and tRNA-modifying enzymes also showed increased abundance, suggesting recovery of translational capacity, which is frequently compromised in hypertrophic myocardium. Structural proteins, including actin isoforms, keratins, laminins, and myosin light chains, were restored toward baseline levels, reflecting improved cytoskeletal organization and extracellular matrix remodeling. Downregulation of gamma-sarcoglycan in fucoidan-treated hearts further supports reversal of maladaptive structural changes. In parallel, modulation of signal transduction and regulatory proteins, such as NOD-like receptors, quinone oxidoreductases, and mitochondrial import factors, indicates activation of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and mitochondrial biogenesis pathways. Collectively, these findings suggest that fucoidan exerts its cardioprotective effects through multi-pathway molecular reprogramming, targeting the metabolic, structural, and regulatory networks disrupted by pressure overload.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates that fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide derived from brown algae, confers significant cardioprotective effects in a murine model of pressure overload. Using LC-MS/MS-based proteomic profiling of fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched left ventricular fractions, we identified a coordinated reversal of pathological remodeling in TAC-FO mice. Specifically, fucoidan restored the expression of proteins involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism, translational machinery, and cytoskeletal organization—three domains critically impaired in pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction [

22,

23,

24]. In both cellular compartments, mitochondrial enzymes such as lipoamide acyltransferase and ATP synthase subunit O were upregulated, suggesting enhanced oxidative phosphorylation and redox homeostasis. Concurrently, ribosomal subunits (e.g., RACK1, mL49, uS11, uL11) and tRNA-modifying enzymes showed increased abundance, indicating recovery of protein synthesis capacity, which is frequently suppressed in hypertrophic myocardium [

23]. Structural proteins—including actin isoforms, keratins, laminins, and myosin light chains—were also restored, reflecting stabilization of cytoskeletal architecture and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. These proteomic signatures support the hypothesis that fucoidan mitigates cardiac remodeling through multi-pathway molecular reprogramming, targeting both metabolic and structural deficits induced by pressure overload [

9,

22,

25].

Further analysis revealed that fucoidan treatment significantly restored mitochondrial enzymes disrupted by pressure overload. Notably, lipoamide acyltransferase, ATP synthase subunit O, and methanethiol oxidase were consistently upregulated in both fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched fractions. These enzymes are essential for branched-chain amino acid catabolism, ATP production, and redox regulation—processes commonly impaired in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling [

22,

24]. The elevation of ATP synthase subunit O suggests enhanced oxidative phosphorylation and improved bioenergetic capacity, while increased methanethiol oxidase reflects recovery of redox balance and detoxification pathways. Lipoamide acyltransferase, a component of the mitochondrial dehydrogenase complex, contributes to metabolic flexibility and supports NADH regeneration, which is critical for sustaining electron transport chain activity. Collectively, these changes indicate a reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction frequently observed in TAC models, where impaired oxidative metabolism and disrupted iron-sulfur cluster assembly compromise cardiomyocyte viability and contractile performance [

22,

24]. These findings are consistent with prior reports implicating mitochondrial damage in the progression of heart failure under pressure overload and extend previous observations by demonstrating that fucoidan restores key enzymatic components of mitochondrial function. By reactivating energy-generating and redox-stabilizing pathways, fucoidan appears to mitigate bioenergetic deficits and preserve organelle integrity, reinforcing its therapeutic potential in the context of cardiac remodeling [

9,

22,

25].

Fucoidan treatment restored key components of the translational apparatus, including ribosomal subunits such as RACK1, mL49, uS11, and uL11, along with enzymes involved in tRNA modification. These proteins are essential for ribosome assembly, mRNA decoding, and post-transcriptional regulation. Their coordinated upregulation in TAC-FO mice suggests reversal of the translational repression commonly observed in pressure overload-induced hypertrophy [

23]. In pathological cardiac remodeling, translational capacity is often compromised due to ribosomal dysfunction and altered protein turnover, impairing cellular repair and adaptation. The observed recovery of ribosomal proteins in both fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched fractions indicates that fucoidan supports biosynthetic reactivation, enabling efficient protein synthesis under stress conditions. This effect is particularly relevant given the role of translational machinery in maintaining proteostasis, regulating stress responses, and facilitating structural remodeling. By restoring ribosomal integrity and enhancing tRNA-modifying enzyme expression, fucoidan appears to promote protein homeostasis and cellular resilience. These findings align with prior reports of ribosomal dysregulation in hypertrophic myocardium and extend them by demonstrating that marine-derived compounds can modulate translational networks at the proteomic level [

23]. Collectively, the data support a model in which fucoidan facilitates biosynthetic recovery as part of its broader cardioprotective mechanism.

Fucoidan treatment also promoted the restoration of structural proteins essential for maintaining cardiomyocyte architecture and mechanical function. Proteomic profiling revealed increased expression of actin isoforms, keratin subtypes, laminin gamma-1, and myosin light chain 1/3 in TAC-FO hearts. These proteins contribute to cytoskeletal organization, sarcomere stability, and ECM anchoring—features commonly disrupted during pressure overload-induced remodeling [

24,

26]. Upregulation of actin-like protein 2 and myosin light chains suggests improved contractile alignment and force transmission, while elevated laminin and keratin levels reflect reinforcement of the cytoskeletal–ECM interface. These changes are consistent with enhanced structural resilience and reduced mechanical stress on cardiomyocytes. Notably, gamma-sarcoglycan, a component of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex associated with sarcolemmal instability, was significantly downregulated in TAC-FO versus TAC mice. This reduction may indicate reversal of maladaptive remodeling, as elevated gamma-sarcoglycan expression has been linked to pathological hypertrophy and membrane fragility [

26]. Together, these findings suggest that fucoidan supports cytoskeletal reorganization and ECM remodeling, contributing to improved mechanical integrity and functional recovery. By restoring the expression of key structural proteins and suppressing maladaptive markers, fucoidan appears to counteract the architectural disarray characteristic of pressure overload-induced cardiomyopathy [

24,

26].

In addition to restoring metabolic and structural domains, fucoidan modulated several proteins involved in inflammatory regulation and mitochondrial signaling, indicating activation of protective pathways. Notably, members of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) protein family, quinone oxidoreductases, and WD repeat-containing proteins were upregulated in TAC-FO hearts. These molecules are associated with innate immune modulation, redox homeostasis, and intracellular signaling scaffolds, respectively, and their coordinated elevation suggests a shift toward anti-inflammatory and antioxidant states [

9,

25]. Increased expression of quinone oxidoreductase supports enhanced detoxification of reactive oxygen species, consistent with fucoidan’s established antioxidant properties in cardiovascular and metabolic models [

25]. Similarly, WD repeat-containing protein 1, which contributes to actin-cytoskeleton remodeling and signal transduction, may enhance cellular resilience under mechanical stress. Restoration of NLR family member X1 implies attenuation of inflammasome activation, aligning with fucoidan’s ability to suppress macrophage-derived inflammatory mediators such as galectin-3 [

9]. These regulatory changes may be linked to activation of the PGC-1α/ ERR signaling axis—a transcriptional pathway known to promote mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative defense [

24]. By modulating proteins downstream of this pathway, fucoidan appears to enhance mitochondrial integrity and dampen inflammatory cascades—mechanisms frequently disrupted in pressure overload-induced heart failure [

22,

24]. Jointly, these findings reinforce the concept that fucoidan exerts its cardioprotective effects through integrated regulation of metabolic, structural, and immunomodulatory networks.

Proteomic profiling of fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched left ventricular fractions revealed both convergent and compartment-specific responses to fucoidan treatment. Across both cell types, fucoidan consistently restored proteins involved in mitochondrial metabolism, translational machinery, and cytoskeletal organization—domains commonly disrupted in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling [

22,

23,

24]. Shared upregulation of enzymes such as lipoamide acyltransferase and ATP synthase subunit O, along with ribosomal subunits and myosin light chains, suggests a coordinated recovery of bioenergetic capacity and structural integrity. Despite these common trends, distinct regulatory targets emerged within each compartment. In fibroblasts, fucoidan elevated mitochondrial import proteins (e.g., TIMMDC1, TOM40B) and iron-sulfur cluster assembly factors, reflecting enhanced organelle biogenesis and redox regulation [

22]. In contrast, cardiomyocytes exhibited increased expression of pantetheinase and WD repeat-containing protein 1, implicating lipid metabolism and intracellular signaling pathways in the myocyte-specific response [

24,

25]. These findings underscore fucoidan’s broad cellular impact, engaging both shared and specialized molecular programs to counteract pressure overload-induced dysfunction. By resolving cell-type-specific proteomic signatures, this study highlights the value of compartmentalized analysis in elucidating therapeutic mechanisms and supports the development of targeted interventions for cardiac remodeling [

23,

24].

Previous investigations have demonstrated that fucoidan mitigates cardiac remodeling by suppressing galectin-3 secretion and reducing myocardial fibrosis in pressure overload models [

9]. These effects were primarily characterized through histological and functional assessments, establishing fucoidan’s anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic potential. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these therapeutic actions remained incompletely defined, particularly regarding intracellular signaling and protein-level modulation. The present study builds on these findings by employing LC-MS/MS-based proteomic profiling to examine fucoidan’s impact at both cellular and systems levels. By separately analyzing fibroblast- and cardiomyocyte-enriched fractions, we achieved cell-type-specific resolution of differentially expressed proteins, revealing coordinated restoration of mitochondrial enzymes, translational machinery, and cytoskeletal components. This approach addresses a critical gap in the literature, where most prior studies lacked high-throughput molecular mapping and compartmentalized analysis [

9,

25]. Importantly, our data identify novel regulatory targets, including mitochondrial import proteins, iron-sulfur cluster assembly factors, and WD repeat-containing proteins, that may mediate fucoidan’s effects on bioenergetics, redox balance, and structural integrity. These findings suggest that fucoidan engages broader molecular networks than previously appreciated, supporting its development as a multi-target therapeutic for pressure overload-induced heart failure [

22,

24].

The results of this study reinforce fucoidan’s potential as a marine-derived therapeutic agent for heart failure, particularly in the context of pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling. Extracted from brown algae such as

Laminaria japonica and

Fucus vesiculosus, fucoidan has demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic properties across diverse disease models [

25,

27]. In cardiovascular settings, its ability to suppress galectin-3 and reduce myocardial fibrosis has been validated in TAC models [

9], establishing a foundation for its therapeutic relevance. Proteomic profiling in this study revealed that fucoidan engages multiple molecular pathways simultaneously—restoring mitochondrial enzymes, ribosomal subunits, cytoskeletal proteins, and regulatory mediators involved in redox balance and inflammation. This multi-pathway engagement distinguishes fucoidan from conventional single-target interventions and suggests a systems-level capacity to reverse cardiac remodeling. Moreover, fucoidan’s favorable safety profile, natural origin, and oral bioavailability support its feasibility for long-term use and integration into nutraceutical formulations [

25,

28]. The consistent molecular restoration observed across both fibroblast and cardiomyocyte compartments, coupled with alignment to known pathogenic mechanisms in heart failure, underscores its translational promise. Future studies should investigate dose optimization, pharmacokinetics, and clinical efficacy in human populations, particularly those with hypertensive heart disease or early-stage heart failure. Fucoidan’s pleiotropic effects and marine origin position it as a compelling candidate for development into cardioprotective nutraceuticals or adjunctive therapies targeting structural and metabolic dysfunction.

While this study provides proteomic evidence supporting fucoidan’s cardioprotective effects in pressure overload-induced remodeling, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the analysis was conducted at a single post-treatment time point, limiting insight into the temporal dynamics of protein expression and pathway activation. Time-course studies would be valuable to determine whether fucoidan’s effects are sustained, progressive, or transient. Second, although differentially expressed proteins were identified with high confidence, functional validation of individual targets, such as mitochondrial import factors, ribosomal subunits, and structural proteins, was not performed. Future investigations should incorporate targeted assays to confirm their mechanistic roles in remodeling reversal. As well, the study did not evaluate dose-response relationships or pharmacokinetics, which are essential for translating fucoidan into clinical or nutraceutical applications. Given its favorable safety profile and oral bioavailability [

25], systematic assessment of dosing strategies could optimize therapeutic efficacy and inform human trials. While LC-MS/MS enabled high-resolution proteomic mapping, integration with transcriptomic, metabolomic, and epigenomic data would offer a more comprehensive view of fucoidan’s molecular impact. Multi-omics approaches have proven effective in characterizing complex disease networks and identifying actionable targets in heart failure [

23,

24]. Finally, the promising results observed here encourage exploration of other marine-derived bioactives with complementary or synergistic properties. Compounds such as laminarin, alginate, and phlorotannins have demonstrated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in cardiovascular models [

27,

28], and may enhance or diversify therapeutic strategies. Expanding the scope of marine pharmacology through integrative profiling and functional validation will be critical for advancing novel interventions in cardiac disease.