Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

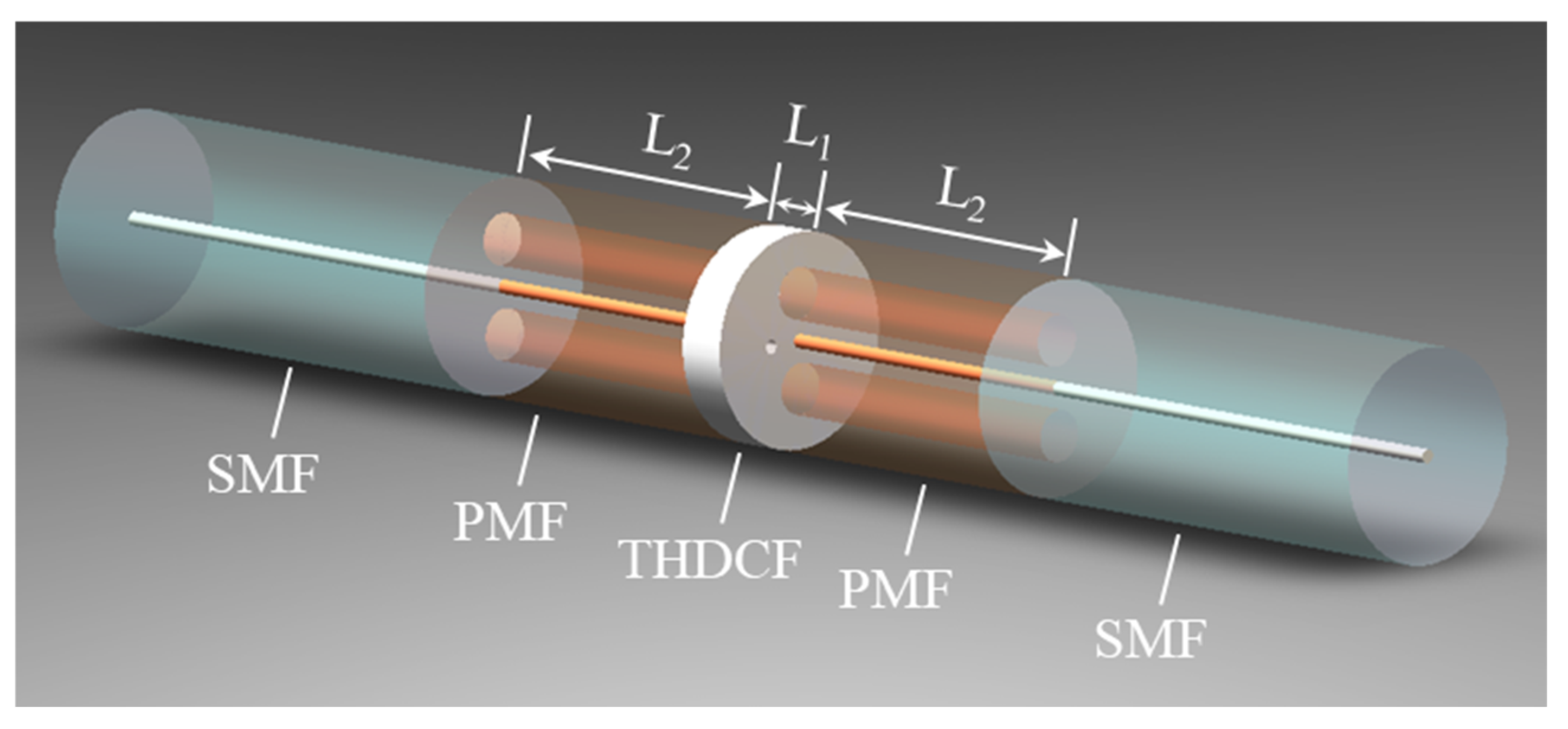

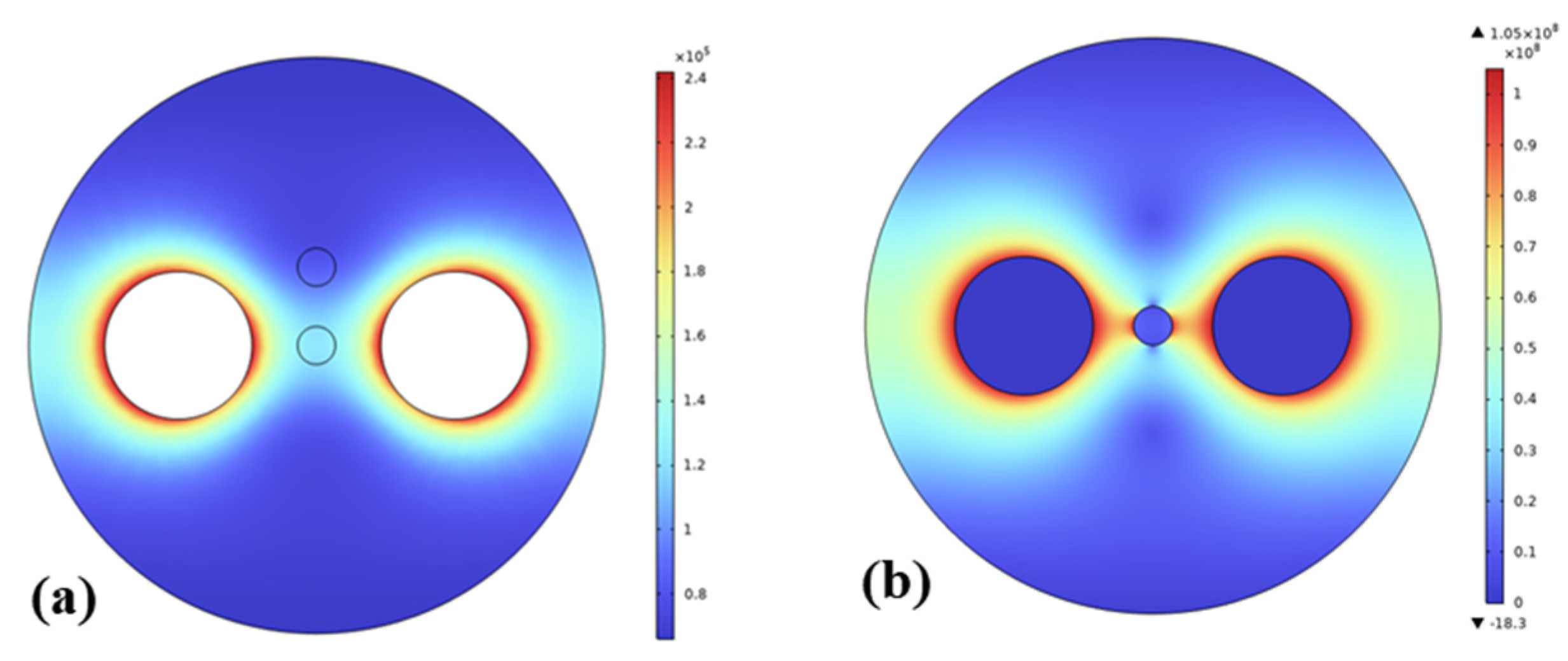

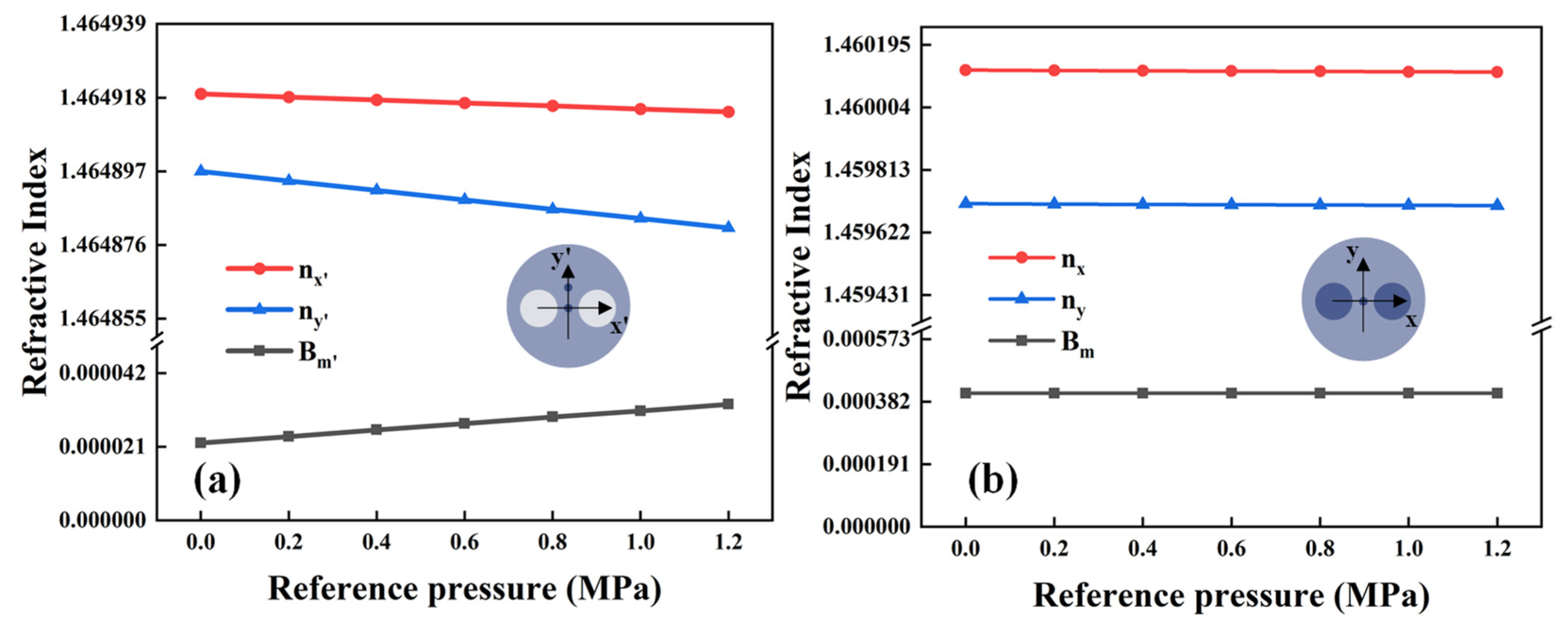

2. Sensor Fabrication and Working Principle

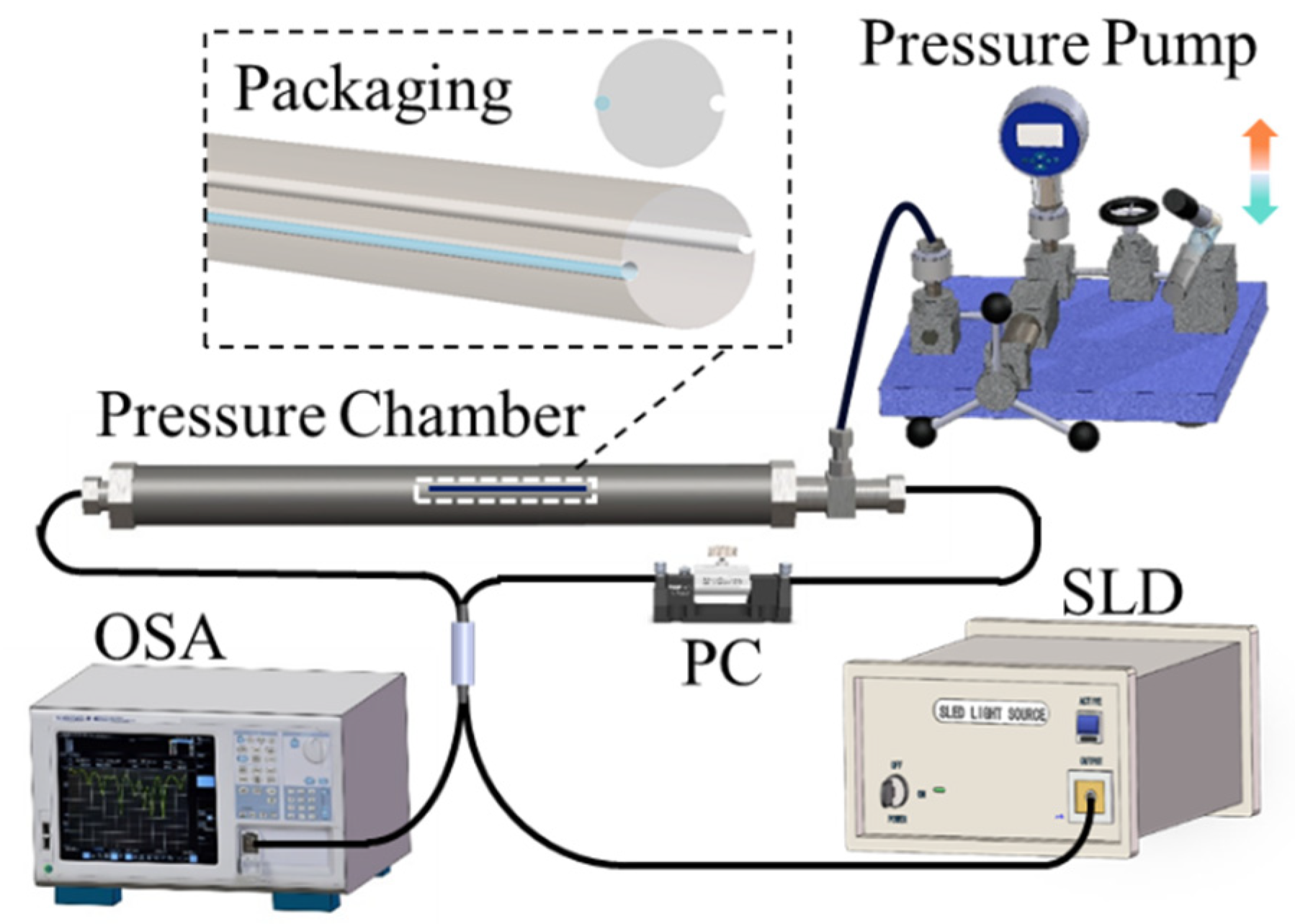

3. Experiments and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Availability of Data and Material

Competing Interest

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Lianqing Zhu, Guangkai Sun, Weimin Bao, Structural deformation monitoring of flight vehicles based on optical fiber sensing technology: A review and future perspectives, Engineering 16 (2022) 39-55.

- Xiuquan Yuan, Wenxin Dong, Jinyang Fan, et al., Dynamic gas emission during coal seam drilling under the thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling effect: A theoretical model and numerical simulations, Gas Science and Engineering 131 (2024).

- Victor S. Balderrama, Jesús A. Leon-Gil, David A. Fernández-Benavides, et al., Manuel Bandala-Sánchez MEMS Piezoresistive Pressure Sensor Based on Flexible PET Thin-Film for Applications in Gaseous-Environments, IEEE Sensors Journal 22 (2022) 3.

- Guilherme Lopes, Nunzio Cennamo, Luigi Zeni, et al., Innovative optical pH sensors for the aquaculture sector: Comprehensive characterization of a cost-effective solution, Optics & Laser Technology 171 (2024) 110355.

- Yunzhou Li, Qiang Zhao, Dongying Chen, et al., Hydrological profile observation scheme based on optical fiber sensing for polar sea ice buoy monitoring, Optics Express 32 (2024) 13001-13013.

- Epin Vorathin, Zohari Mohd Hafizi, Nurazima Binti Ismail, et al., Review of high sensitivity fibre-optic pressure sensors for low pressure sensing, Optics & Laser Technology 121 (2020) 105841.

- John W. Berthold III, Fiber Optic Sensors: An Introduction for Engineers and Scientists, Third Edition, Industrial Applications of Fiber Optic Sensors, Chapter 22, First Published: 05 April 2024.

- Xuehui Zhang, Honghu Zhu, Xi Jiang, et al., Distributed fiber optic sensors for tunnel monitoring: A state-of-the-art review, Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering 16 (2024) 3841-3863.

- Jitendra Narayan Dash, Xin Cheng, and Hwa-yaw Tam, Low gas pressure sensor based on a polymer optical fiber grating, Optics Letters 46 (2021) 933-936.

- Looh Augustine Ngiejungbwen, Hind Hamdaoui, Mingyang Chen, Polymer optical fiber and fiber Bragg grating sensors for biomedical engineering Applications: A comprehensive review, Optics & Laser Technology 170 (2024) 110187.

- Abdullah Al Noman, Jitendra Narayan Dash, Xin Cheng, et al., Mach-Zehnder interferometer based fiber-optic nitrate sensor, Optics Express 21 (30) (2022) 38966-38974.

- Xiaoguang Mu, Jiale Gao, Yuqiang Yang, Parallel Polydimethylsiloxane-Cavity Fabry-Perot Interferometric Temperature Sensor Based on Enhanced Vernier Effect, IEEE Sensors Journal 22 (2022) 1333-1337.

- Chaluvadi V Naga Bhaskar, Subhradeep Pal, Prasant Kumar Pattnaik, Recent advancements in fiber Bragg gratings based temperature and strain measurement, Results in Optics 5 (2021) 100130.

- Manish Mishra, Prasant Kumar Sahu, Fiber Bragg Gratings in Healthcare Applications: A Review, IETE Technical Review 40 (2022) 202–219.

- Jichao Liu, Yunfei Hou, Jing Wang, et al., Multi-parameter demodulation for temperature, salinity and pressure sensor in seawater based on the semi-encapsulated microfiber Mach-Zehnder interferometer, Measurement 196 (2022) 111213.

- Yunlian Ding, Yao Chen, Si Luo, et al., All-fiber MZI hydrostatic pressure sensor, Optics & Laser Technology 171 (2024) 110414.

- Yong Zhao, Jian Zhao, Xixin Wang, et al., Femtosecond laser-inscribed fiber-optic sensor for seawater salinity and temperature measurements, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 353 (2022) 131134.

- Xiaojun Zhu, Haoran Zhuang, Yu Liu, et al., High-sensitivity robust Mach-Zehnder interferometer sensor in ultra-compact format, Measurement 236 (2024) 115051.

- Chaoqun Ma, Donghong Peng, Xuanyao Bai, et al., A Review of Optical Fiber Sensing Technology Based on Thin Film and Fabry-Perot Cavity, Coatings 13 (2023) 1277.

- Yuqiang Hu, Lu Cao, Shaoxiong Nie, et al., MEMS Fabry-Perot sensor for accurate high pressure measurement up to 10 MPa, Optics Express 32 (2024) 37059-37072.

- Jingwei Lv, Wei Li, Jianxin Wang, et al., High-sensitivity strain sensor based on an asymmetric tapered air microbubble Fabry-Pérot interferometer with an ultrathin wall, Optics Express 32 (2024) 19057-19068.

- Xinyu Zhao, Xiwang Ren, Jiandong Bai, et al., Enhanced High-Temperature Gas Pressure Sensor based on a Fiber Optic Fabry-Pérot Interferometer Probe, Journal of Lightwave Technology (2024) 1-7.

- Hamed Arianfard, Saulius Juodkazis, David J. Moss, et al., Sagnac interference in integrated photonics, Applied Physics Reviews, 10 (2023) 011309.

- Loc Hin Cho, Chuang Wu, Chao Lu, et al., A Highly Sensitive and Low-Cost Sagnac Loop Based Pressure Sensor, IEEE Sensors Journal 13 (2013) 3073-3078.

- H. Y. Fu, Chuang Wu, M. L. V. Tse, et al., High pressure sensor based on photonic crystal fiber for downhole application, Applied Optics 49 (2010) 2639-2643.

- Yao Chen, Weixuan Luo, Baobao Jiao, et al., Reflective All-Fiber Integrated Sensor for Simultaneous Gas Pressure and Temperature Sensing, Journal of Lightwave Technology 42 (2024) 463-469.

- Eric Udd, Applications and Development of the Sagnac Interferometer, In Fiber Optic Sensors (eds E. Udd and W.B. Spillman) (2024).

- Pizzaia, João Paulo Lebarck, Shujia Ding, et al., Highly sensitive temperature sensing based on a birefringent fiber Sagnac loop, Optical Fiber Technology 72 (2022) 102949.

- Dhyana C. Bharathan, R. Martijn Wagterveld, Karima Chah, et al., Optical fiber sensor with enhanced strain sensitivity based on the Vernier effect in a three-FBG cascaded Fabry–Perot configuration, Optical Fiber Technology 94 (2025): 104361.

- Yundong Liu, Hailiang Chen, Qiang Chen, et al., Experimental Study on Dual-Parameter Sensing Based on Cascaded Sagnac Interferometers with Two PANDA Fibers, Journal of Lightwave Technology 40 (9) (2022) 3090-3097.

- Chaoyi Liu, Hailiang Chen, Qiang Chen, et al., Sagnac interferometer-based optical fiber strain sensor with exceeding free spectral measurement range and high sensitivity, Optics & Laser Technology 159 (2023) 108935.

- Juan Ruan, Lirui Hu, Anshan Lu, Weiyan Lu, et al., Temperature Sensor Employed TCF-PMF Fiber Structure-Based Sagnac Interferometer, IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, 29 (16) (2017) 1364-1366.

- Qiang Ge, Jianhui Zhu, Yanyan Cui, Fiber optic temperature sensor utilizing thin PMF based Sagnac loop, Optics Communications, 502 (2022) 127417.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).