1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of unknown aetiology that can affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Its clinical course is characterised by alternating periods of activity (flare-ups) and phases of remission [

1]. It is known to affect the immune system, causing an unregulated response that gives rise to its symptoms [

2]. The most common signs and symptoms include diarrhoea, weight loss, abdominal pain, and fatigue, while severe cases may cause fistulas to develop that require surgery. Flare-ups often lead to hospitalisation, which, combined with the burden of symptoms and medical treatments, make this disease highly debilitating, greatly affecting patients and those around them.

Furthermore, the unpredictable nature of the disease and the complexity of its treatment, often cause high levels of perceived stress, which in turn, can trigger flare-ups [

3,

4].

Environmental factors play a decisive role in health, both in terms of disease prevention and the progression or complication of chronic conditions. Elements related to the environment, nutrition and lifestyle habits can modulate the activation of certain genes, triggering significant effects upon health and disease development [

5].

Social support is particularly noteworthy within the group of social variables, since it contributes most to adaptation and effective coping with the disease. Social support is defined as the interaction established between at least two people, in which both the sender and the receiver recognise the objective of improving the well-being of the recipient [

6]. It can also be understood as the set of expressive or instrumental resources—whether perceived or received—provided by the community, social networks, and trusted individuals [

7].

Having trusted individuals with whom to share emotions, concerns, difficulties, or opinions, or simply experiencing the feeling of being listened to and accepted, has been associated with a significant positive impact on self-esteem and the ability to adequately cope with complex and stressful situations [

8,

9].

Received social support refers to the effective help that individuals obtain through their connections and relationships with others, that is, the concrete actions that other people take to assist them. Perceived social support, on the other hand, corresponds to the cognitive assessment that individuals make regarding the reliability of their social connections; in other words, their subjective perception of the support they receive [

10].

Sources of social support refer to the interpersonal bonds and relationships available to a person—such as family, partner, friends, work colleagues, neighbours or institutions—which can offer emotional, practical, informational or evaluative support in times of need [

11].

Various studies have shown that social support has a beneficial effect on the course of the disease, contributing to both better clinical outcomes and greater stability. It also leads to an increase in psychological well-being, better adjustment to the disease and an improvement in the quality of life of those affected [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The effectiveness of social support may vary depending on the source of support. Emotional and instrumental support from family and friends is consistently linked to improved emotional well-being.

On the other hand, one of the most important functions of social support is its buffering or indirect role in shaping the perception of stress. According to the model proposed by Cohen and Wills [

18] (1985), sources of support act as a resource that modulates the cognitive assessment of external demands so that when the level of social support is high, the perception of stress tends to be lower. This effect occurs because social support provides emotional, instrumental and informational resources that lessen the perceived threat in stressful situations.

Furthermore, social support has a direct effect on the individual, making adaptation to life circumstances easier, despite stressful events. Thus, social support plays a vital role in helping individuals adapt to illness, cope more effectively, and maintain emotional well-being [

19,

20].

The role of social support as a protective factor against stress is well established in scientific literature [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

A recent study from 2022 demonstrated that individuals with low levels of social support display heightened stress-related brain activity, notably in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex, the dorsal striatum, and the periaqueductal grey matter [

28].

Regarding inflammatory bowel disease, Britt’s work indicated that social support plays a role in reducing signs and symptoms in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [

29].

The study we conducted in 2024, demonstrated a relationship between low levels of social support and increased stress levels, further confirming that the interaction between social support and stress plays a crucial role in triggering flare-ups [

30].

Stress is defined as an ongoing interaction between the person and their environment, assessed by the individual as a situation that overwhelms them or exceeds their resources and jeopardises their well-being [

31]. It is an integrative, psychobiological and psychosocial response to internal or external demands perceived as threatening or exceeding the individual’s personal and social resources, significantly influencing the individual’s interaction with their social environment and emotional well-being [

32].

Recent studies have shown that the psychobiological mechanisms involved in the stress response can lead to alterations in the integrity of the intestinal membrane and its permeability, thus compromising its protective function [

3,

30,

33,

34].

Perceived stress not only affects emotional well-being but has also been associated with disease activity and the onset of flare-ups in people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [

3,

30,

35].

A 2022 review reported that stress induces dysfunctions in immune regulation and causes alterations to the composition of the gut microbiome in the context of inflammatory bowel disease [

36].

In 2011, Konturek, Brzozowski and Konturek, also analysed the effect of stress on the brain-gut axis, showing that this stimulus triggers a cascade of events that include the release of neurotransmitters and pro-inflammatory cytokines. These physiological responses have a direct impact on intestinal function, causing alterations in the mucosa and the composition of the microbiome [

37].

The course and severity of the disease are influenced by the individual’s level of compliance and adherence to treatment. While some patients take a proactive approach and actively engage with their treatment, others display a fatalistic outlook, believing that the course of their disease is beyond their control. This perception of control over health plays a crucial role in disease management and long-term clinical outcomes. This is a matter of utmost importance when dealing with chronic diseases [

38].

This concept relates to the locus of control. According to Rotter’s original formulation on social learning (1966), locus of control should be considered to be a personality trait. There are two types of locus of control: internal and external. The first refers to the subject’s perception that events occur mainly as a result of their own actions, i.e., they feel that they are in control of their lives. The second relates to the subject’s perception that events occur as a result of chance, fate, luck, or the power and decisions taken by others. Thus, individuals with an external locus of control, believe that what happens to them is not related to their own actions, effort, and dedication, but instead to luck, chance, God, or other powerful forces [

39].

The initial idea of a locus of control gave rise to the concept of “health locus of control” [

40]. This belief is specifically related to health-related behaviours and outcomes. Individuals with an internal health locus of control believe that the progression or worsening of their condition depends largely on their own actions, such as adherence and compliance with treatment. To the contrary, those with an external locus of control believe that their health outcomes are determined by external factors, and that their illness will worsen regardless of their adherence and compliance with treatment.

A locus of control is a stable characteristic that influences an individual’s behaviour [

41]. Experimental findings show that an individual’s perception of causality is an important moderator of their response to stressful life events [

42].

Several studies have shown that an internal locus of control can reduce the negative effects of stress [

43]. Thus, individuals who believe they can influence events are less likely to perceive stressful situations as permanent. Essentially, a person can tolerate more stress if they believe that the situation will not continue indefinitely. Furthermore, if a person believes they have control over a situation, it will be perceived as less threatening [

44].

Studies have shown that individuals with a mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, who possess an internal locus of control, are more likely to recover after hospitalisation for a relapse, as they tend to show greater adherence and compliance with treatment. The opposite occurs when these individuals have an external locus of control [

45].

In a study conducted in 2024 by Tsionis and his team on refugees with psychopathology, it was found that these individuals had an external locus of control. Furthermore, it showed that there was a negative correlation between an internal locus of control and the severity of depression. There was also a positive correlation between the intensity of depression and an external locus of control [

46].

In 2024, a study conducted on patients with a substance use disorder, examined the interaction between self-efficacy for abstinence, locus of control, and perceived social support during rehabilitation. The findings indicated that individuals with a higher self-efficacy for abstinence were more likely to have an internal locus of control, which positively influenced recovery outcomes. Furthermore, the study also demonstrated that both an internal locus of control and perceived social support from family members were significant predictors of self-efficacy for abstinence [

47].

With regard to intestinal disease, a study conducted on adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease found that an external locus of control was associated with increased physical severity, a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, and greater family dysfunction, compared to patients with an internal locus of control in the same situation [

48].

Prospero et al., recently reported in their 2025 study, that an external health locus of control is associated to worse health in irritable bowel syndrome patients [

49].

In a case-control study comparing patients with ulcerative colitis to healthy individuals, Suraj et al., (2025) [

51], assessed the health locus of control and found that sick patients showed a greater tendency towards an external locus of control than healthy individuals.

We conducted our study in light of the above and the lack of specific studies on stress, social support, its different sources and the health locus of control in Crohn’s disease. We wanted to determine the levels and role played by these variables across the different stages of CD. In addition, we examined the influence of these psychosocial factors on disease flare-ups, with the ultimate aim of improving the treatment, attention and care of these patients.

This study had two main objectives: (1) examine the roles of perceived stress, perceived social support, received social support, different sources of social support, and the health locus of control during different stages of CD; (2) analyse, study, and determine the relationship and influence of these variables on the occurrence of CD flare-ups.

Our initial hypothesis was that social support and an internal health locus of control positively influence CD and stress, while an external health locus of control has the opposite effect. We also hypothesised that variables with positive effects would decrease the likelihood of disease flare-ups, whereas those with negative effects would increase it.

To address the aims of this study, the following specific objectives were established:

- Measure the level of perceived stress, perceived social support, received social support, different sources of social support, and both the internal and external health locus of control.

- To analyse and compare how the study variables vary across the different stages of the disease.

- Examine and analyse the association between the study variables and the presence of disease flare-ups (dependent variable).

- Examine and analyse the influence of the study variables and their relationship to the occurrence of disease flare-ups (dependent variable).

- Determine the extent to which psychosocial factors predict the likelihood of disease flare-ups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

A cross-sectional, observational study was conducted using validated scales to assess stress, total social support (both perceived and received), as well as different sources of support and health locus of control in Crohn’s disease.

2.2. Participants

The sample was comprised of 160 participants, divided into two groups: 80 individuals experiencing a CD flare-up, and 80 individuals in remission. Members of the Crohn’s disease flare-up group, had previously received a confirmed diagnosis through standard diagnostic tests including blood tests, stool analysis, colonoscopy, upper gastrointestinal series, and computed tomography. All were following both pharmacological and dietary treatment regimens. At the time of admission, these participants presented with fever, vomiting, cachexia, abdominal pain and, in some cases, pseudo-intestinal obstruction.

Participants in the remission group were clinically stable, and were not being treated with prednisone. All reported feeling well, with no abdominal pain, and had passed 0 to 2 formed stools per day without rectal bleeding.

To be included in the study, participants were required to reside within the Gregorio Marañón Hospital healthcare area and have a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease confirmed by a gastroenterologist. Furthermore, the diagnosis must have been established between the ages of 17 and 40, in accordance with the Montreal classification (A2). The disease had to be in the terminal ileum, the colon, or both segments (L1, L2, or L3, according to this classification). In terms of clinical pattern, types B1 (non-stenosing, non-fistulising or inflammatory), and B2 (stenosing), were considered. Remission group participants were required to have a Harvey–Bradshaw Index score of less then 5, whereas those in the flare-up phase had to fall within the ranges corresponding to moderate or severe disease according to the same index.

Patients with any chronic organic disease other than Crohn’s disease were excluded from the study, as were those with a psychological or psychiatric disorder diagnosed by a psychiatrist.

2.3. Procedure

Participants in flare-up phase were recruited upon admission to the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Ward at the Gregorio Marañón Hospital, following a confirmed diagnosis of a Crohn’s disease flare-up. Participants in remission were recruited through the Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Association of the Community of Madrid. All participants were enrolled by the principal investigator of the study.

The study was presented personally to all potential participants, who were provided with details regarding eligibility criteria. After checking that all potential participants had understood everything, questionnaires were then completed by those interested. In all cases, participation was voluntary and uncompensated.

The study followed a cross-sectional design and adhered to the STROBE checklist to guide the reporting of research findings. All participants signed the Written Informed Consent Form. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid (ref. 2018/19-022). Data collection took place between September 2021 and December 2022.

2.4. Instruments

The following questionnaires were used in this research: a Sociodemographic Questionnaire, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14), the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale, and two Social Support Questionnaires.

2.4.1. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS14), used in this study was adapted by Remor and Carrobles [

52] from the original scale developed by Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein [

53].

The PSS14 scale assesses the extent to which life situations are perceived as stressful. It consists of 14 items with a five-point response format (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = often, and 4 = very often). The total stress score is the sum of the scores assigned to each of the items, requiring the scores of items 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13 to be reversed, that’s to say 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2, 3 = 1, and 4 = 0. Scores below 0 to 18 indicate a low level of perceived stress, between 19 and 37 indicate a moderate level, and above 38 indicate a high level of perceived stress.

2.4.2. Perceived and Received Social Support Questionnaires

The first questionnaire used was the Perceived Social Support Questionnaire, and the second, the Received Social Support Questionnaire. Both questionnaires consider sources of support and evaluate them independently, so that direct scores are obtained for each one. Both were validated by Díaz Vega (1986) [

54]. The Perceived Social Support Scale assesses support from various sources such as family, friends, other Crohn’s disease patients, and healthcare personnel, using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (none) to 7 (maximum). The second scale measures the social support actually received from these same sources (family, friends, other Crohn’s patients and healthcare personnel), using a Likert scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 7 (very satisfied).

The total perceived social support score for each participant was obtained by adding the scores assigned to each source by each subject. The possible scores range from 12 (minimum) to 84 (maximum), with values below 36 indicating a low level of social support, scores between 36 and 60 indicating moderate support, and scores above 60, reflecting a high level of perceived social support from the different sources.

Regarding the perceived social support from each support source, the minimum score is 3 and the maximum score is 21. A score below 9 is considered indicative of a low level of perceived social support from a given support source, between 9 and 15 indicates a moderate level, and above 16, a high level of social support from that specific source.

The total score for social support received from different support sources is calculated by adding the value assigned to each source of support. The lowest score would be 4 points and the highest 28. A score below 12 is indicative of a low level of social support received from the different support sources, between 12 and 19 indicates a moderate level, and above 19, a high level.

In terms of social support received from each source, the minimum score is 1 point and the maximum is 7. A score below 3 indicates a low level of social support received from the support source, between 3 and 5, a moderate level, and above 5, a high level of social support received from that specific source.

2.4.3. Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLC)

The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLC) [

55] is the original Wallston, Wallston and Devellis scale, adapted by Garcia-Alcaraz et al. [

56]. The scale consists of 18 items, six for each factor, answered according to a Likert-type scale of 6 points, ranging from 0 (“in complete disagreement”) to 5 (“completely agree”).

In relation to the factors considered, three main dimensions were established: Factor I, called ‘Other Powerful Factors’ (Other Powerful Health Locus of Control), was calculated by adding the scores from items 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 18; Factor II, identified as ‘Internal’ (Internal Health Locus of Control), comprised the total scores from items 1, 6, 8, 12, 13 and 17, and Factor III, called ‘Chance’ (Chance Health Locus of Control), was calculated from the total of items 2, 4, 9, 11, 15 and 16. Scores lower than or equal to 3.1, indicate a low level of health locus of control, whereas scores above 3.1 up to 5, indicate a high level of health locus of control, whether internal or external.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Qualitative variables were analysed using percentages, whereas quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency, including mean and standard deviation.

The t-test for independent samples was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the groups studied.

Binary logistic regression was used to analyse the relationship between the variables under study and the existence of a flare-up. This statistical technique makes it possible to identify and quantify the effect of different independent variables on the likelihood of a dichotomous outcome. It determines which factors increase or reduce the likelihood of the outcome occurring, and identifies the variables that significantly explain its presence or absence. In this study, the dependent variable was defined as the presence or absence of a flare-up, defined as a binomial variable with two possible values: flare-up present = 1; flare-up absent = 0.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 23 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used to carry out descriptive statistics, hypothesis testing and analyses of internal consistency, reliability and validity of the research instruments. All tests were conducted at a 95% confidence level, with p-values below 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Sociodemographic Variables

The study included 160 individuals diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, evenly distributed between the active (flare-up) and inactive (remission) phases of the disease.

In the remission group (n = 80), 37.5% were men and 62.5% were women, with a mean age of 34.5 years. Within this group, 61.3% of participants were married, 36.3% were single, and 2.4% were divorced. In terms of educational background, 33.8% had completed upper secondary school education, 23.2% had secondary school education, 16.3% had completed intermediate university studies, and 26.3% had completed higher education. Most worked full-time (81.3%). Regarding living arrangements, most participants lived with two people (36.2%) while 32.5% lived with three or more people. In the group of individuals with Crohn’s disease experiencing a flare-up (n = 80), 58.8% were men and 41.2% were women, with an average age of 32.5 years. In this group, 53.8% were single, 37.4% were married, and 8.8% were divorced/separated. In terms of education, 44.2% had completed upper secondary school education, 24.1% secondary school education, 13% intermediate university studies, and 18.2%, higher education. Full-time workers made up 58.8% of individuals, and most lived with three or more people. For a detailed overview of the sociodemographic data for each group, see

Table 1.

3.2. Analysis of Perceived and Received Social Support from Family, Friends, other Crohn’s Disease Patients, and Healthcare Professionals, together with Stress and both the Internal and External Locus of Control

Total perceived social support reached a moderate level in both groups, with averages of 45.1 in patients in remission and 51.2 in those experiencing a flare-up, with a difference of 6.1 points in favour of the latter group.

In terms of perceived family social support, the level was high in both cases, with identical scores (M=17.3). Perceived social support from friends was moderate in both the remission phase (M=12.1) and the flare-up phase (M=13.4).

On the other hand, perceived social support from other Crohn’s disease patients was low during the remission phase (M = 6.8), but increased slightly during the flare-up phase (M = 8.5). Perceived support from healthcare personnel, was moderate in both phases, with mean scores of 10.9 for those in remission and 12.7 for those experiencing a flare-up.

In terms of total social support received, moderate levels were identified in the remission phase (M = 17.4), and high levels in the flare-up phase (M = 20.1). Upon analysis of specific sources, family support received was moderate for both groups (M = 6.0 in the remission phase; M = 6.3 in the flare-up phase, respectively). Social support received from friends went from moderate in the remission phase (M = 4.8) to high in the flare-up phase (M = 5.2). Support received from other CD patients was low in the remission phase (M = 2.5) and moderate in the flare-up phase of the disease (M = 3.4). Finally, the support received from healthcare personnel increased from moderate (M = 4.7) for those in remission, to high (M = 5.2) for those experiencing a flare-up, showing greater contact and availability of healthcare professionals during the most critical phases.

In terms of psychological variables, perceived stress reached moderate levels in both groups, although it was higher for patients experiencing a flare-up (M = 27.8) than for those in remission (M = 22.6), displaying a difference of 5.2 points.

Finally, analysis of the locus of control revealed that individuals in remission scored higher for an internal locus of control (M = 3.3) compared to those experiencing a flare-up (M = 3.1). In contrast, scores for an external locus of control were lower in the remission group and higher in the flare-up group (M = 2.8).

These results are presented in

Table 2 and offer a clearer understanding of the dynamics between social support and psychological variables in relation to the clinical status of the disease, highlighting the importance of social and professional support during periods of greatest vulnerability.

3.3. Comparison of Perceived and Received Social Support from Family, Friends, other Crohn’s Disease Patients, and Healthcare Professionals, as well as Stress and both Internal and External Locus of Control between Individuals with Crohn’s Disease in Remission and those experiencing a Flare-up.

The independent samples t-test was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences. The results showed statistically significant differences in the total perceived support and total received support from the various support sources (p = .001; p = .000, respectively), indicating significant variability between the groups in terms of the overall perception and reception of social support.

More specifically, in relation to perceived social support from other patients with Crohn’s disease, significant differences were observed between the means of both groups (p = .046). Similarly, perceived social support from healthcare personnel showed statistically significant differences (p = .019), suggesting that the source of support is a differentiating factor in the subjective experience of support.

With regard to social support received, statistically significant differences were identified in the case of support from other patients with Crohn’s disease (p = .010), reflecting the importance of peer support in this clinical context.

On the other hand, when analysing the stress variable, significant differences were found between the means of the groups (p = .001), highlighting the different impact this variable had in the sample studied. Finally, the internal locus of control also showed statistically significant differences (p = .034), suggesting a possible relationship between the degree of perceived control and the other psychosocial variables analysed.

These results are summarised in

Table 3, which details the differences observed between the groups across the different variables assessed.

3.4. Correlations between the Dependent Variable (Flare-up Occurrence) and Perceived and Received Social Support from Family, Friends, other Crohn’s Disease Patients, and Healthcare Professionals, as well as Stress and both the Internal and External Locus of Control

In this study, we wanted to determine the relationship between the variables under investigation and the occurrence of CD flare-ups. To do this, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed since this technique allows us to determine which variables increase or decrease the likelihood of an outcome occurring. In our case, we wanted to know whether the variables studied could explain the existence of a CD flare-up. The existence of a flare-up was established as a binomial and categorical dependent variable, with two possible outcomes: YES or NO. The “Enter Method” was used. In this technique, the table of variables excluded from the equation shows the bivariate statistical analysis, indicating the correlations of the independent variables that explain the dependent variable (in this case, the existence of a flare-up).

The bivariate analysis of the independent variables and the dependent variable determined that all the variables studied in this research explain the dependent variable, except perceived social support from family, received social support from friends, and the external locus of control. The results can be seen in

Table 4.

Furthermore, the omnibus test showed that the main effects mode was statistically significant, (χ²= 36,550; p = 0,000), confirming that the selected variables can predict the occurrence of flare-ups.

Table 5.

Omnibus Test for the coefficients of the model.

Table 5.

Omnibus Test for the coefficients of the model.

| |

|

Chi-Squared |

df |

Sig. |

| Step 1 |

Step |

36.550 |

10 |

.000 |

| |

Block |

36.550 |

10 |

.000 |

| |

Model |

36.550 |

10 |

.000 |

3.5. Influence of total perceived social support from different sources, total received social support from different sources, perceived and received social support from family, friends, other Crohn’s patients, and healthcare personnel, together with stress and an internal locus of control in Crohn’s Disease

In addition, we aimed to predict the likelihood of a flare-up based on the variables that had proven to be statistically significant in the bivariate analysis. Binary logistic regression was again used to determine which variables influence an increase or decrease in the likelihood of this outcome occurring (existence of a flare-up).

It was found that the logistic regression model correctly predicted 74.3% of individuals who experienced a flare-up and 77.8% of individuals who did not. The results are shown in

Table 6.

The data corresponding to the model found are shown in

Table 7.

We found that the variables that predict the likelihood of a flare-up are total perceived social support from different sources (TPSS), perceived social support from friends (PSSF), perceived social support from healthcare personnel (PSSHP), stress, and the internal locus of control (ILC). These findings indicate that total perceived social support from different sources, perceived social support from friends, perceived social support from healthcare personnel, and an internal locus of control, act as protective variables that decrease the likelihood of a flare-up, in such that the higher their level, the lower the likelihood of a flare-up occurring. It was also observed that the stress variable was positively associated with the likelihood of a flare-up occurring; the greater the stress level, the higher the likelihood of its occurrence. Consequently, the predictive formula for the likelihood of a flare-up is

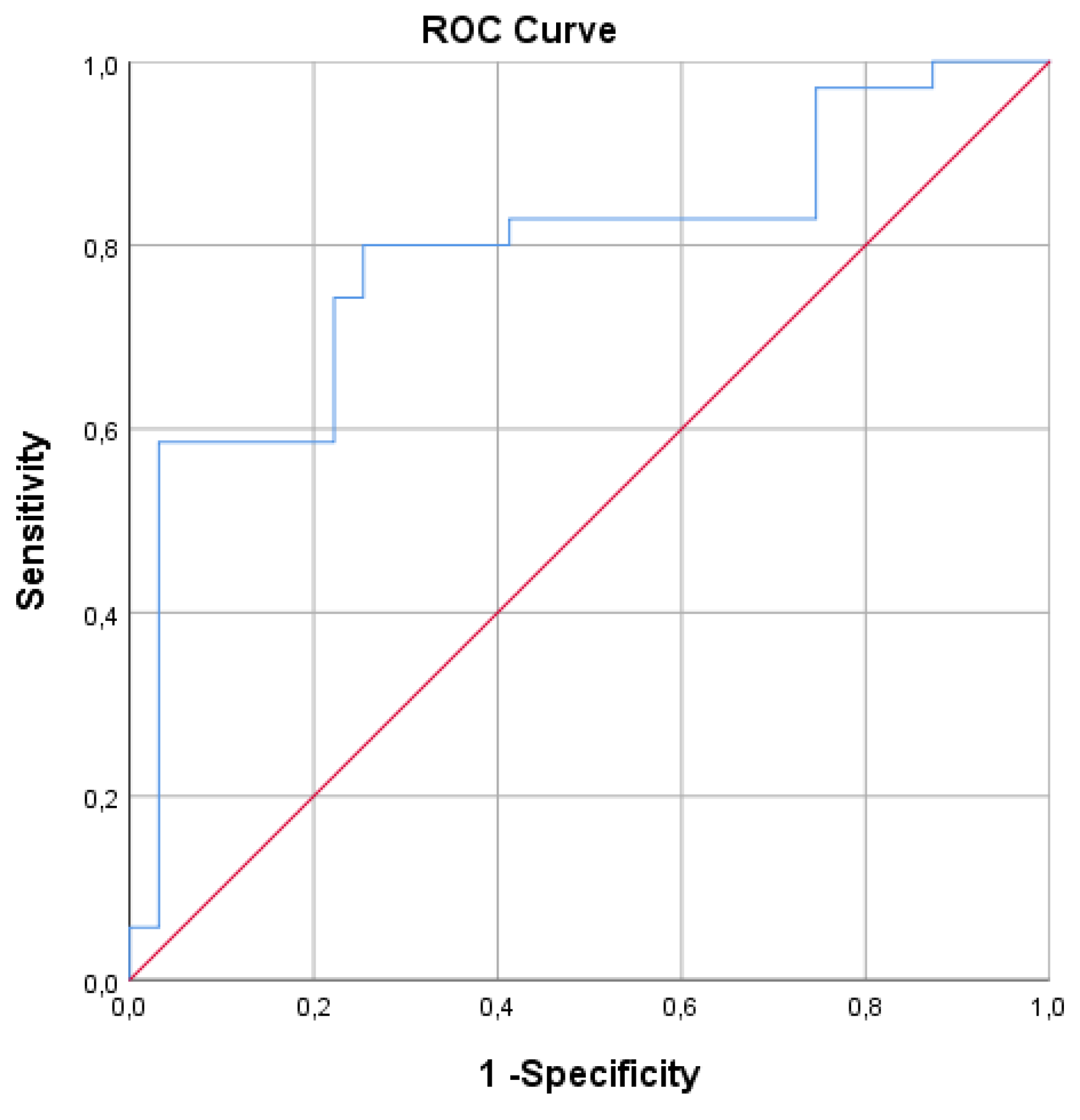

The ROC curve was used to assess the effectiveness of the binary logistic regression model. Graphically, the curve shifted upwards and to the left, indicating that the area under the curve is greater than the area above it. This therefore suggests that the test demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity.

Finally, the performance of the statistically significant binary logistic regression model in predicting the likelihood of a flare-up was determined using an ROC curve (see

Figure 1). The model demonstrated an accuracy of 76.1.%, with a specificity of 59.6%, and a sensitivity of 96.8%, using a cut-off point of 0.5. Thus, these results indicate the high sensitivity and specificity of the ROC curve and the suitability of the model found.

4. Discussion

This article contributes to a deeper understanding of how psychological stress, social support, and locus of control influence individuals with Crohn’s disease (CD). It provides valuable evidence on how these psychosocial factors can directly affect the clinical course of the disease in patients and the onset of CD flare-ups. Furthermore, our findings offer a solid basis for the design of comprehensive care programmes aimed at improving the quality of care, support and treatment for these patients.

The main objectives of this research were to examine the roles of perceived stress, perceived social support, received social support, the different sources of social support, and health locus of control across different stages of CD. It also sought to determine the impact of these variables on the occurrence of CD flare-ups.

In relation to the first main objective, the levels of the variables under study were measured, analysed, and compared across different stages of the disease. The results obtained through measures of central tendency and the t-test, demonstrated the relevance of the psychosocial factors studied in the clinical course of the disease and its different phases.

With regard to total perceived social support, the results show statistically significant differences between the groups (p = .001). Individuals experiencing a CD flare-up had higher mean scores (M = 51.2) compared to those in remission (M = 45.1). This finding suggests that, during periods of heightened symptomatology, patients perceive greater availability of social support within their environment, probably reflecting a more active mobilisation of support networks in response to their clinical vulnerability.

In particular, perceived social support from family remained stable and identical in both groups (M = 17.3), highlighting the consistency of family support regardless of clinical status. This finding shows that the family acts as a stable source of both emotional and instrumental support, even during periods of remission.

With regard to perceived support from friends (a primarily emotional and instrumental source of support), a tendency towards higher values was observed during the flare-up stage (M = 13.4) compared to the remission stage (M = 12.1). This increase, although not statistically significant, could reflect greater involvement of the informal social environment during periods of increased patient vulnerability.

The perceived support from other patients with Crohn’s disease was generally low, but significantly higher during flare-ups (M = 8.5), than in remission (M = 6.8), (p = .046). This result suggests that peer interaction intensifies at times of greater clinical burden, functioning as an important source of understanding and emotional validation. This type of support, which is emotional and instrumental in nature, becomes relevant when patients seek companionship and shared coping strategies for this disease, which is consistent with previous findings [

17].

The perceived support from healthcare personnel (mainly informational support), also showed significant differences (p = .019), with higher scores in the CD flare-up group (M = 12.7) than in the remission group (M = 10.9). This highlights the importance of professional support during acute episodes, when accessibility to healthcare personnel increases and the therapeutic relationship becomes essential for ensuring safety and disease management. The informational support offered by professionals, as seen in previous studies [

17], is key for the patient’s adjustment to the disease.

Regarding total social support received, the results also revealed statistically significant differences between the groups (p < .001), with higher levels during flare-up phase (M = 20.1) than in remission phase (M = 17.4). In line with the results found for total perceived social support, this pattern suggests that patients with active disease are more aware of the support they receive, reflecting an increased perception during this phase of the availability of help within their social environment during periods of greatest need.

Specifically, the support received from family remained moderate in both groups (M = 6.0 in remission; M = 6.3 during flare-up). This result, in line with the perceived support from family, reinforces the consistent role of this source of emotional and instrumental support, regardless of the clinical status of the pathology [

17]. In contrast, the support received from other patients showed statistically significant differences (p = .010), with higher mean values during the flare-up phase (M = 3.4) compared to the remission phase (M = 2.5). This finding highlights the importance of peer support during active phases of the disease, when both the physical and emotional burden are greater. Support received from healthcare personnel increased significantly in individuals experiencing a flare-up (M = 5.2), compared to those in remission (M = 4.7), showing a trend towards significance (p = .066). This finding is consistent with increased healthcare interaction during active phases of the disease.

As a whole, these results reveal an adaptive dynamic of social support that adjusts to patients’ perceived needs throughout the course of the disease. The family environment acts as a stable and continuous source of support, whereas friends, peers, and health professionals become more actively involved during periods of acute disease activity.

With regard to psychological variables, the level of perceived stress was significantly higher in patients during the flare-up phase (M = 27.8), than in those in remission (M = 22.6), (p = .001). This finding is consistent with studies linking stress to the reactivation of inflammatory bowel disease [

3,

4,

30,

35]) and to the contrary [

29]. Regarding locus of control, patients in the remission phase showed a higher internal locus of control (M = 3.3), compared to those who in the active phase (M = 3.1), with statistically significant differences (p = .034). These findings are consistent with others indicating that personal perception of causality is an important moderator [

41,

42]. They also align with studies showing that having an internal locus of control reduces the negative effects of stress [

43], since individuals who see themselves as being in control of a situation, tend to experience a lower perceived threat level, and have a better controlled response to stress [

44]. These findings, specifically in CD, support the idea that an internal locus of control contributes to greater clinical stability of the patients, while the presence of an external locus of control is associated with an increased likelihood of CD flare-ups [

4]. A similar pattern has been observed in other intestinal diseases [

51].

Regarding the second main objective of this study, we analysed the relationship between different dimensions of social support and its various sources, as well as stress, and locus of control and the occurrence of CD flare-ups. The results obtained through binary logistic regression showed that most of the psychosocial variables evaluated had a significant association with the dependent variable—the occurrence of flare-ups—which demonstrates the relevance of psychosocial factors in the clinical course of the disease.

The results obtained from the initial step of binary logistic regression (

Table 4) revealed statistically significant associations between the occurrence of Crohn’s disease flare-ups and social support, stress, and locus of control. Overall, these findings suggest that both perceived and received social support could play a relevant role in the clinical evolution of Crohn’s disease patients.

Firstly, a significant relationship was found between total perceived social support (p = .003) and total received social support (p = .001), with respect to CD flare-ups, indicating that both the amount of support received and the perception of support, are related to the course of the disease. These findings indicate that patients who perceive or receive less social support from their environment are more likely to experience disease flare-ups. However, these results also suggest that social support does not have a direct effect on disease activity, but instead has a beneficial impact on patients’ adjustment to the disease [

18,

19,

20]. Research on the regulatory effect of high levels of social support in predicting the likelihood of CD flare-ups is also consistent with the findings of this study [

30].

Analysis of specific sources of support revealed that perceived social support from friends (p = .017), other Crohn’s disease patients (p = .044), and healthcare personnel (p = .005) was significantly associated with the occurrence of flare-ups. These findings reinforce those described above, highlighting the greater involvement of the informal social environment (friends), increased emotional and instrumental support from peers (other Crohn’s patients), and the availability and importance of the therapeutic relationship during the active phase of the disease. In contrast, perceived support from family members did not show statistical significance (p = .639), which may be explained by the minimal variation in perceived support from this source during different stages of the disease.

Regarding received social support, significant associations were found with support received from family (p = .044), other patients (p = .019) and healthcare personnel (p = .034). In this case, received support appears to have a more uniform impact across the different sources, suggesting that tangible and concrete assistance (e.g., companionship, information, or practical help), may be more influential than the mere perception of available support. This distinction between perceived and received support highlights the importance of treating these as separate constructs in psychosocial research on inflammatory bowel diseases.

Likewise, the stress variable showed a significant association with the occurrence of flare-ups (p = .030), which reinforces the hypothesis that this psychological factor influences the activity of Crohn’s disease. Several studies have shown that high levels of stress can alter immunoregulatory mechanisms, increasing susceptibility to intestinal inflammation. It is noteworthy that this finding aligns with previous literature linking high levels of stress to the reactivation of inflammatory bowel disease [

3,

4,

30,

33,

34,

35].

In this context, social support could act as a mediator or buffer against the impact of stress, contributing to the clinical stability of patients, which in turn, shows that the higher the level of social support, the lower the level of stress [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Finally, the internal locus of control (p = .047) was significantly related to the occurrence of flare-ups. This is due to the beneficial effect of an internal locus of control being related to compliance and therapeutic adherence [

45].

This study also sought to examine the influence of the variables under investigation on the likelihood of flare-up occurrence.

The binary logistic regression model (

Table 7) identified perceived social support as the primary protective factor against flare-ups occurring, with a significant negative coefficient (B = –0.217; p = .035; OR = 0.805), suggesting that higher levels of perceived social support are associated with a reduced likelihood of disease exacerbation. This finding is consistent with previous studies that highlight the protective role of social support against symptoms and inflammatory activity in chronic diseases [

30,

38]. It further highlights the direct effect of social support in promoting better adjustment to the illness and enhancing psychological well-being [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Analysis of the different sources of support revealed that perceived support from friends and healthcare personnel were also significant predictors in the model, both having protective effects (B = –0.300; p = .028; OR = 1.350 and B = –0.373; p = .021; OR = 1.452, respectively).

These findings reinforce the idea that close and expert sources of support have a significant impact on the active phases of the disease. Support from friends can help reduce feelings of isolation and encourage emotional stability, while perceived support from healthcare professionals represents a key source of security and enhances self-efficacy in symptom management. Once again, the direct and beneficial effects of social support from friends and healthcare professionals are evident [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Friends provide emotional support and validation, whereas healthcare professionals provide information, guidance and reassurance in managing the chronic condition.

Perceived stress emerged as one of the most significant predictors in the model (B = 0.074; p = .003; OR = 1.077), indicating that higher stress levels increase the likelihood of a flare-up. This finding is consistent with extensive evidence linking psychological stress to the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the aggravation of intestinal inflammation [

3,

30,

38,57].

Finally, the internal locus of control was also significantly associated with the likelihood of flare-ups (B = –0.643; p = .034; OR = 0.526). This finding confirms that patients with an internal locus of control, i.e., those who attribute their health outcomes to their own actions, have less risk of aggravating their condition. Thus, greater patient involvement in their own care, adherence to treatment, effective stress management and less emotional vulnerability associated with this psychological variable, contribute to greater well-being during the course of the disease. In contrast, the presence of an external locus of control is associated with an increased likelihood of CD flare-ups [

4].

One of the strengths of this study, is its comprehensive psychosocial approach, as it simultaneously addresses psychological, cognitive and social variables (stress, locus of control and social support), providing a more complete understanding of the impact of psychosocial factors on the clinical course of CD.

Another notable strength is the differentiated analysis of social support, which distinguishes between perceived and received social support, as well as between different support sources such as family, friends, peers, and healthcare professionals. This approach provides a more nuanced and realistic understanding of the dynamics of support in the context of chronic diseases and, more specifically, in CD.

Similarly, the methodological rigour is evident in the use of multivariate statistical analyses, such as binary logistic regression, which enable the identification of predictive relationships between psychosocial variables and the occurrence of flare-ups, thereby enhancing the internal validity of the study.

In terms of clinical and applied relevance, our findings offer empirical evidence with direct implications for healthcare practice, highlighting strategic approaches focused on strengthening social support, reducing stress and reinforcing the development of an internal locus of control in these patients.

Furthermore, it is important to emphasise the consistency of our findings with previous scientific literature. Our results align with both national and international studies, reinforcing their theoretical coherence and supporting their external validity.

Regarding limitations and the direction of future research, the primary constraints of this study are its type and sample size.

Future research should consider larger samples, long-term longitudinal designs, and the incorporation of complementary qualitative studies.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study show that the psychosocial factors investigated play a significant role in the clinical progression of Crohn’s disease. Specifically, both perceived and received social support were found to be higher during flare-ups, reflecting an adaptive mobilisation of support networks in response to the patient’s increased vulnerability. The family remains a constant and structural source of support, whereas friends, peers and healthcare professionals tend to increase their involvement at times of greater clinical burden, providing emotional, instrumental and informational assistance.

The predictive model confirms the protective effect of perceived social support on the onset of flare-ups, particularly support from friends and healthcare personnel, suggesting that perceiving such support fosters well-being, security and self-efficacy in disease management. In contrast, perceived stress significantly increases the likelihood of a flare-up. This finding reinforces the crucial role of social support in reducing stress and promoting clinical stability in patients with Crohn’s disease.

Finally, an internal locus of control emerges as a protective factor associated with greater therapeutic adherence, more effective coping and lower emotional vulnerability, thereby contributing to clinical stability. As a whole, these findings confirm the interaction between the psychosocial factors studied and disease activity, highlighting the need to incorporate the assessment and enhancement of social support, stress management and the development of an internal locus of control, into comprehensive care programmes for people with Crohn’s disease.

Based on the results obtained, programmes aimed at improving the quality of life, disease management and clinical stability of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) are recommended. These initiatives should build on the protective role of social support, the strengthening of an internal locus of control and the reduction and management of stress.

Programmes could be developed to strengthen the support networks of patients with Crohn’s disease and enhance their sense of companionship. Psychoeducational workshops could be implemented to help patients shift from an external to an internal health locus of control. In addition, targeted actions focused on stress management could be incorporated into these initiatives.

Such programmes could help delay the onset of flare-ups, reduce hospital admissions, and improve patients’ adaptation to the disease. They would also strengthen both the direct and indirect effects of social support through its various sources. Furthermore, these initiatives are likely to encourage patients to take a more active role in self-care and the management of their disease.