Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Histology and Tissue Microarray (TMA)

2.3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.4. Digital IHC Quantification

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Histomorphological Evaluation in HE-Stained Sections

3.2. Overall DAXX and ATRX Expression in Prostate and Bladder Tissues

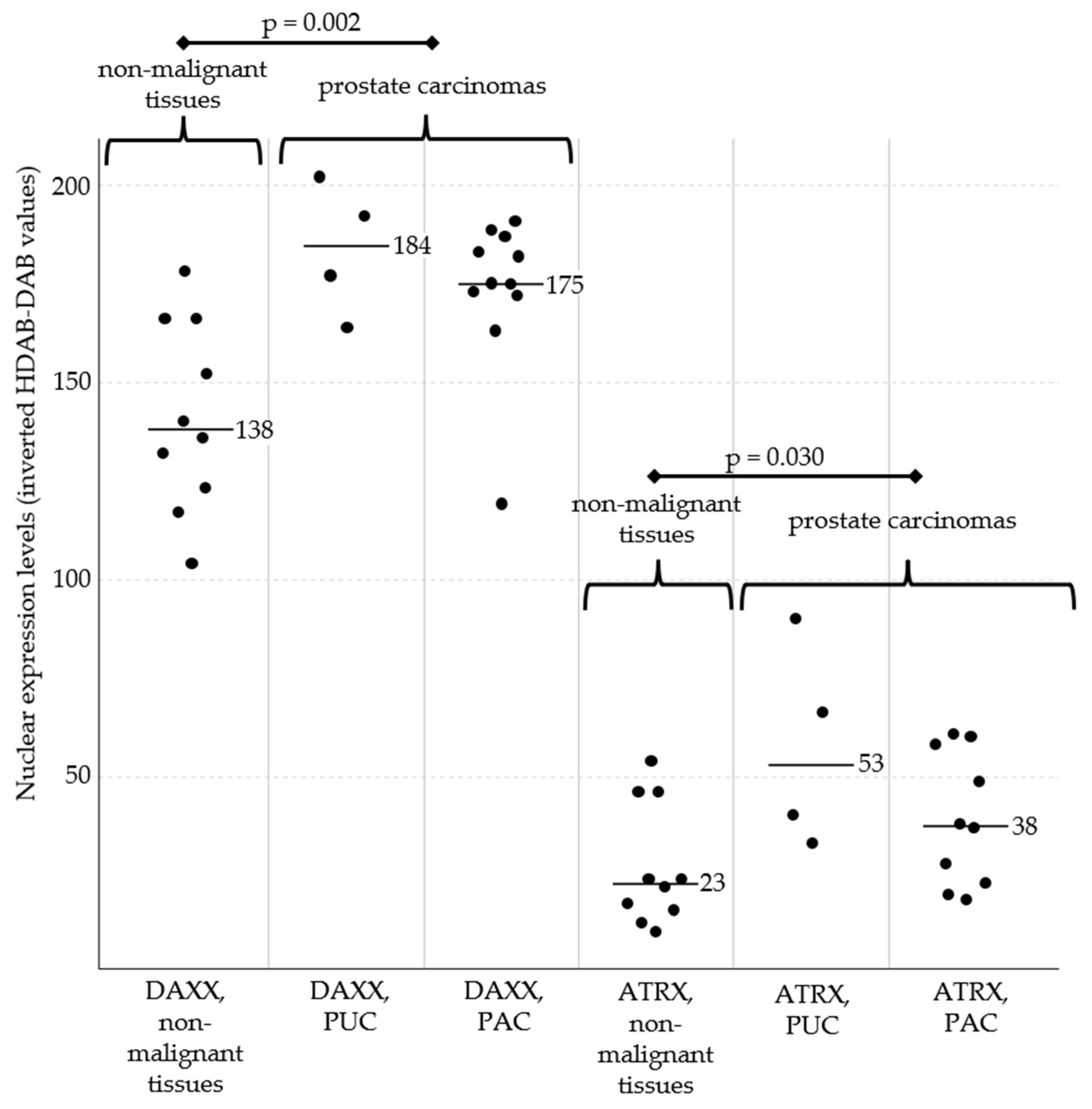

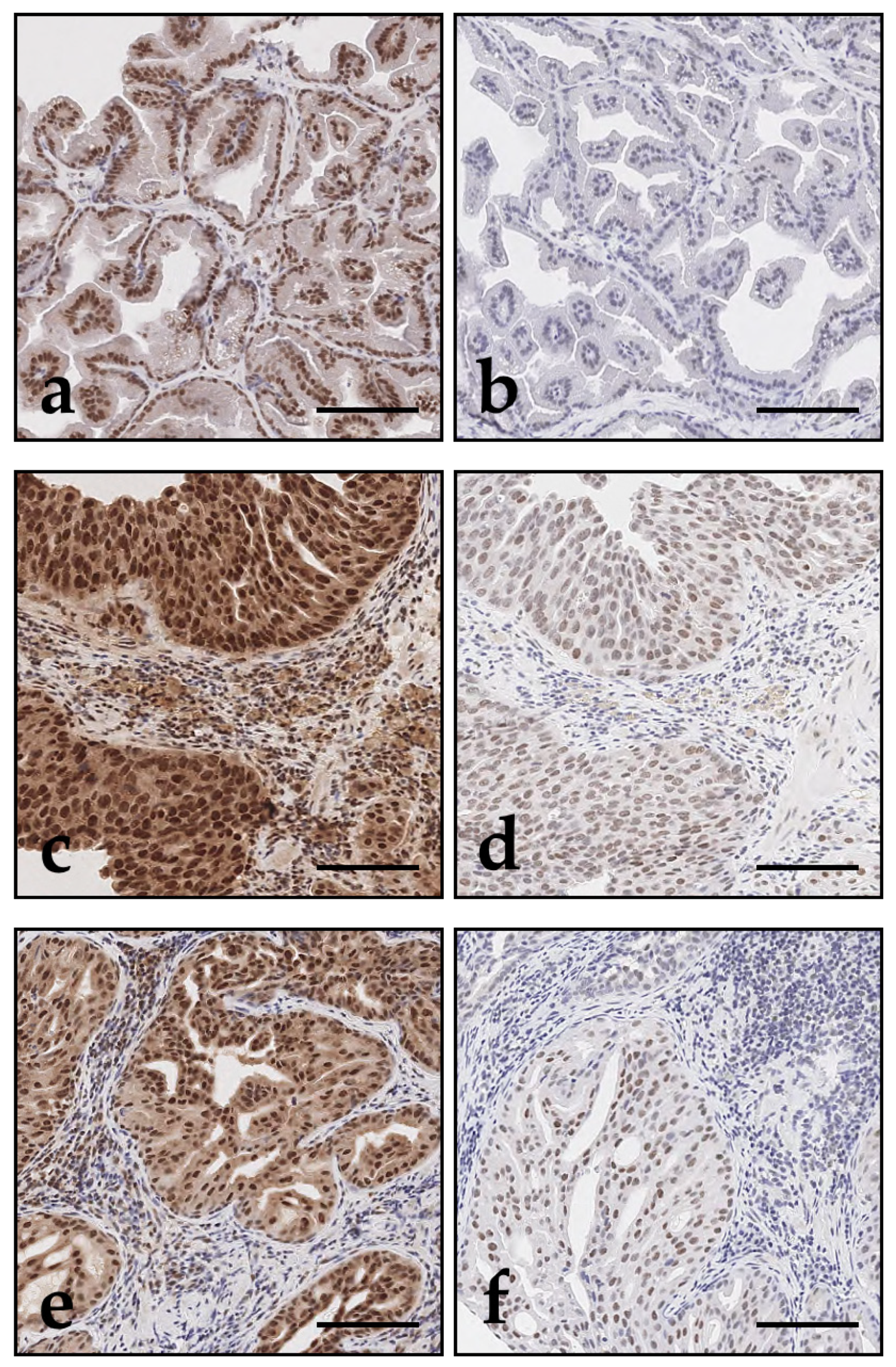

3.3. Epithelial Nuclear DAXX and ATRX Expression in the Prostate

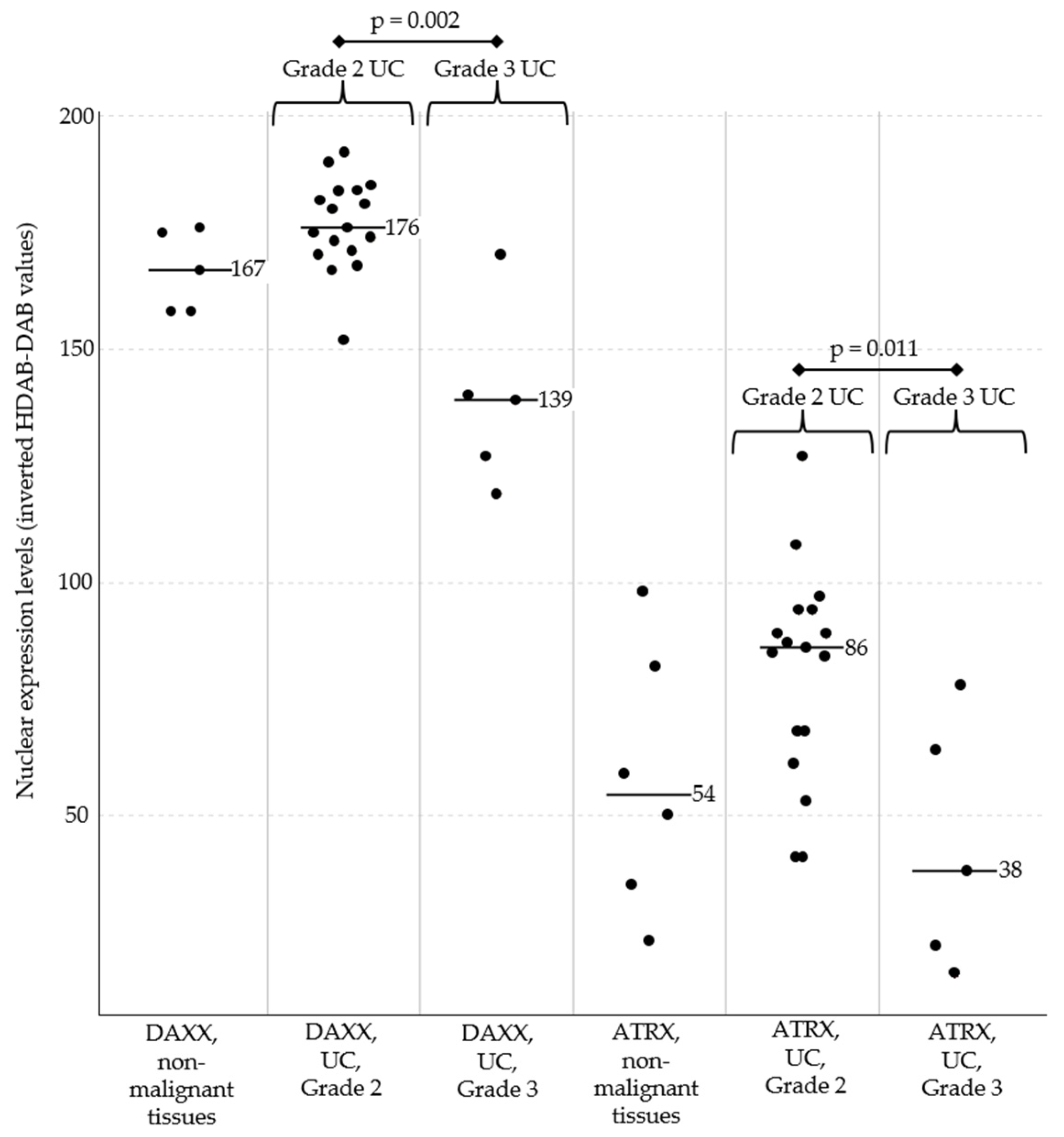

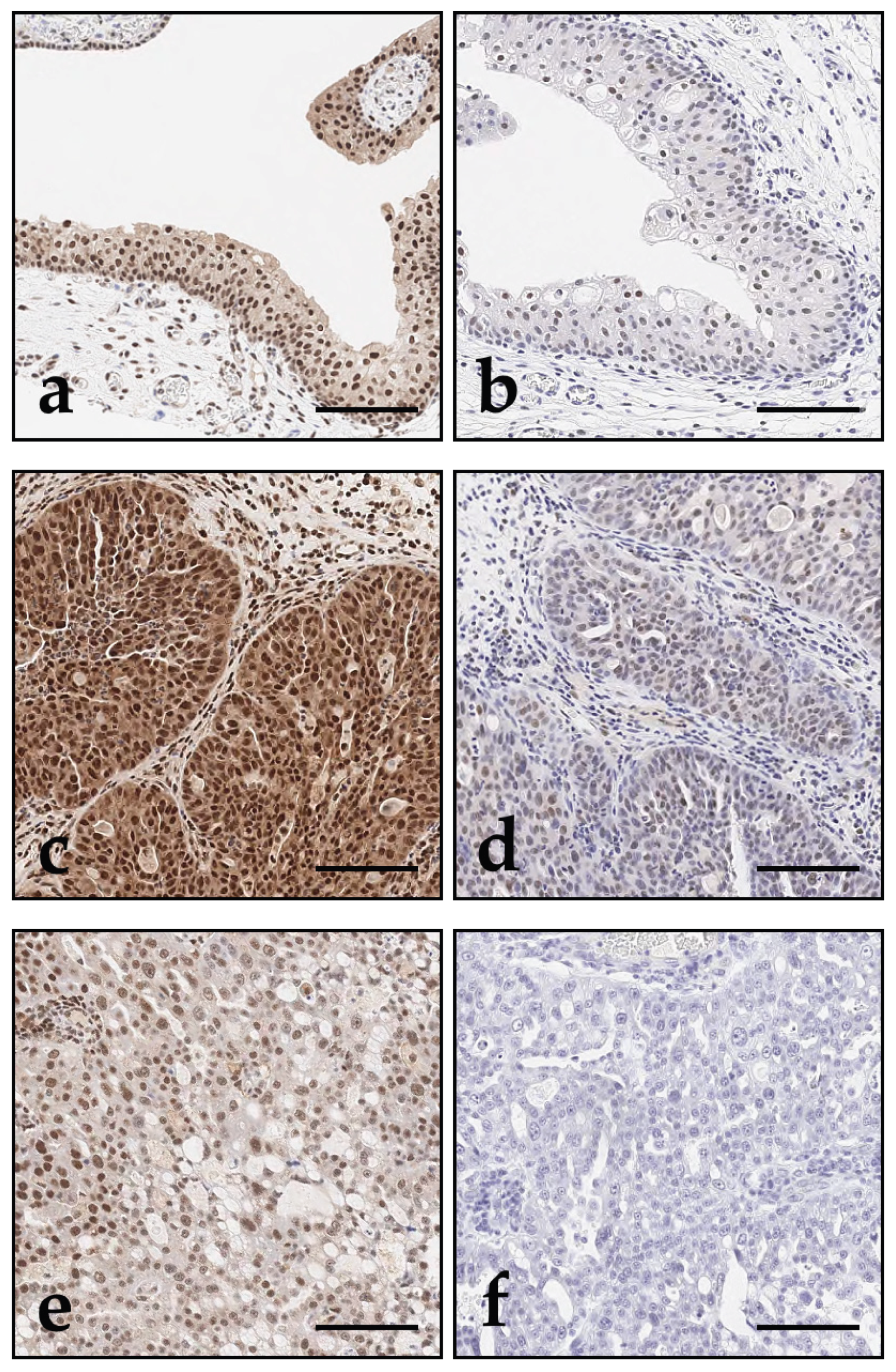

3.4. Epithelial Nuclear DAXX and ATRX Expression in the Bladder

3.5. Main Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Considerations

4.2. Organ-Specific Expression Patterns in Canine Prostate and Urinary Bladder Tissue

4.3. Clinical Relevance in Human Medicine and Implications for Veterinary Medicine

4.4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, V.J.; Evans, K.M.; Sampson, J.; Wood, J.L.N. Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2010, 51, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, L.; Qiu, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Guan, X.; Cen, X.; Zhao, Y. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomarkers Definitions working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatterbuck Soper, S.F.; Walker, R.L.; Pineda, M.A.; Zhu, Y.J.; Dalgleish, J.L.T.; Wang, J.; Meltzer, P.S. Cancer-associated DAXX mutations reveal a critical role for ATRX localization in ALT suppression. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Chen, X.; Ji, T.; Cheng, M.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, C. The Chromatin Remodeler ATRX: Role and Mechanism in Biology and Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, A.D.; Banaszynski, L.A.; Noh, K.-M.; Lewis, P.W.; Elsaesser, S.J.; Stadler, S.; Dewell, S.; Law, M.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; et al. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell 2010, 140, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, E.I.; Reinberg, D. New chaps in the histone chaperone arena. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, M.A.; Qadeer, Z.A.; Valle-Garcia, D.; Bernstein, E. ATRX and DAXX: Mechanisms and Mutations. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, P.; López-Contreras, A.J. ATRX, a guardian of chromatin. Trends Genet. 2023, 39, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, A.; Rocha, W.; Verreault, A.; Almouzni, G. Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell 2007, 128, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, S.G.; Pereira, B.J.A.; Lerario, A.M.; Sola, P.R.; Oba-Shinjo, S.M.; Marie, S.K.N. The chromatin remodeler complex ATRX-DAXX-H3.3 and telomere length in meningiomas. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021, 210, 106962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, R.F. de; Heaphy, C.M.; Maitra, A.; Meeker, A.K.; Edil, B.H.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Ellison, T.A.; Schulick, R.D.; Molenaar, I.Q.; Valk, G.D.; et al. Loss of ATRX or DAXX expression and concomitant acquisition of the alternative lengthening of telomeres phenotype are late events in a small subset of MEN-1 syndrome pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Mod. Pathol. 2012, 25, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, I.; Kurrer, A.S.; Vassella, E.; Dettmer, M.; Rudolph, T.; Banz, V.; Hunger, F.; Pasquinelli, S.; Speel, E.-J.; Perren, A. Loss of DAXX and ATRX are associated with chromosome instability and reduced survival of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 453–60.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindi, G.; Mete, O.; Uccella, S.; Basturk, O.; La Rosa, S.; Brosens, L.A.A.; Ezzat, S.; Herder, W.W. de; Klimstra, D.S.; Papotti, M.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 115–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumors in domestic animals; Meuten, D. J., Ed., 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Ames, 2017; ISBN 9780813821795. [Google Scholar]

- Vries, C. de; Konukiewitz, B.; Weichert, W.; Klöppel, G.; Aupperle-Lellbach, H.; Steiger, K. Do Canine Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms Resemble Human Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours? A Comparative Morphological and Immunohistochemical Investigation. J. Comp. Pathol. 2020, 181, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachida, S.; Vakiani, E.; White, C.M.; Zhong, Y.; Saunders, T.; Morgan, R.; Wilde, R.F. de; Maitra, A.; Hicks, J.; Demarzo, A.M.; et al. Small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas are genetically similar and distinct from well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreilmeier, T.; Sampl, S.; Deloria, A.J.; Walter, I.; Reifinger, M.; Hauck, M.; Borst, L.B.; Holzmann, K.; Kleiter, M. Alternative lengthening of telomeres does exist in various canine sarcomas. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Ludwig, L.; Krijgsman, O.; Adams, D.J.; Wood, G.A.; van der Weyden, L. Comparison of the oncogenomic landscape of canine and feline hemangiosarcoma shows novel parallels with human angiosarcoma. Dis. Model. Mech. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Shi, C.; Edil, B.H.; Wilde, R.F. de; Klimstra, D.S.; Maitra, A.; Schulick, R.D.; Tang, L.H.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Choti, M.A.; et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science 2011, 331, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, R.; Marrano, P.; Teerapakpinyo, C.; Arnoldo, A.; Shago, M.; Shuangshoti, S.; Thorner, P.S. Immunohistochemistry for ATRX Can Miss ATRX Mutations: Lessons From Neuroblastoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourlakis, M.C.; Schoop, M.; Plass, C.; Huland, H.; Graefen, M.; Steuber, T.; Schlomm, T.; Simon, R.; Sauter, G.; Sirma, H.; et al. Overexpression of the chromatin remodeler death-domain-associated protein in prostate cancer is an independent predictor of early prostate-specific antigen recurrence. Hum. Pathol. 2013, 44, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho-Camillo, C.M.; Miracca, E.C.; dos Santos, M.L.; Salaorni, S.; Sarkis, A.S.; Nagai, M.A. Identification of differentially expressed genes in prostatic epithelium in relation to androgen receptor CAG repeat length. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2006, 21, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzi, A.; Montironi, M.A.; Mazzucchelli, R.; Scarpelli, M.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cheng, L.; Paone, N.; Castellini, P.; Montironi, R. Immunohistochemical analysis of chromatin remodeler DAXX in high grade urothelial carcinoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2013, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segersten, M.U.; Edlund, E.K.; Micke, P.; La Torre, M. de; Hamberg, H.; Edvinsson, A.E.L.; Andersson, S.E.C.; Malmström, P.-U.; Wester, H.K. A novel strategy based on histological protein profiling in-silico for identifying potential biomarkers in urinary bladder cancer. BJU international 2009, 104, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, X.; Xie, W.; Chen, S.; Hu, Y.; Xing, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Han, Z.; et al. Opposing biological functions of the cytoplasm and nucleus DAXX modified by SUMO-2/3 in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, I.; Liao, D. DAXX in cancer: phenomena, processes, mechanisms and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 7734–7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klarskov, L.; Ladelund, S.; Holck, S.; Roenlund, K.; Lindebjerg, J.; Elebro, J.; Halvarsson, B.; Salomé, J. von; Bernstein, I.; Nilbert, M. Interobserver variability in the evaluation of mismatch repair protein immunostaining. Hum. Pathol. 2010, 41, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butter, R.; Hondelink, L.M.; van Elswijk, L.; Blaauwgeers, J.L.G.; Bloemena, E.; Britstra, R.; Bulkmans, N.; van Gulik, A.L.; Monkhorst, K.; Rooij, M.J. de; et al. The impact of a pathologist’s personality on the interobserver variability and diagnostic accuracy of predictive PD-L1 immunohistochemistry in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2022, 166, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrielides, M.A.; Gallas, B.D.; Lenz, P.; Badano, A.; Hewitt, S.M. Observer variability in the interpretation of HER2/neu immunohistochemical expression with unaided and computer-aided digital microscopy. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2011, 135, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraw, A.; Aeffner, F. Whole-slide imaging, tissue image analysis, and artificial intelligence in veterinary pathology: An updated introduction and review. Vet. Pathol. 2022, 59, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, C.; Foster, R.A.; Grieco, V.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; Wood, G.A.; Culp, W.T.N.; Murua Escobar, H.; Marzo, A.M. de; Laufer-Amorim, R. Histopathological Terminology Standards for the Reporting of Prostatic Epithelial Lesions in Dogs. J. Comp. Pathol. 2019, 171, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, C.; Grieco, V. Proposal of Gleason-like grading system of canine prostate carcinoma in veterinary pathology practice. Res. Vet. Sci. 2015, 103, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, V.E.; Norris, A.; Jacobs, R.M.; Laing, E.; Withrow, S.; Macy, D.; Tomlinson, J.; McCaw, D.; Ogilvie, G.K.; Pidgeon, G. Pathology of canine bladder and urethral cancer and correlation with tumour progression and survival. J. Comp. Pathol. 1995, 113, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierorazio, P.M.; Walsh, P.C.; Partin, A.W.; Epstein, J.I. Prognostic Gleason grade grouping: data based on the modified Gleason scoring system. BJU international 2013, 111, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poalelungi, D.G.; Neagu, A.I.; Fulga, A.; Neagu, M.; Tutunaru, D.; Nechita, A.; Fulga, I. Revolutionizing Pathology with Artificial Intelligence: Innovations in Immunohistochemistry. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cives, M.; Partelli, S.; Palmirotta, R.; Lovero, D.; Mandriani, B.; Quaresmini, D.; Pelle’, E.; Andreasi, V.; Castelli, P.; Strosberg, J.; et al. DAXX mutations as potential genomic markers of malignant evolution in small nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puto, L.A.; Brognard, J.; Hunter, T. Transcriptional Repressor DAXX Promotes Prostate Cancer Tumorigenicity via Suppression of Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 15406–15420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinoni, I. Prognostic value of DAXX/ATRX loss of expression and ALT activation in PanNETs: is it time for clinical implementation? Gut 2022, 71, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Fan, S.; Hu, C.; Liu, X.; Hou, T. Clinicopathological Significance of ATRX Expression in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Patients: A Retrospective Study. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 6931–6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, B.; McFadden, E.; Holth, A.; Brunetti, M.; Flørenes, V.A. Death domain-associated protein (DAXX) expression is associated with poor survival in metastatic high-grade serous carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2020, 477, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, D.; Watters, A.K.; To, J.T.; Young, M.W.; Muratori, J.; Wilkoff, M.H.; Abraham, R.G.; Plummer, M.M.; Zhang, D. ALT Positivity in Human Cancers: Prevalence and Clinical Insights. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, L.M.; Flynn, R.L. Highlighting vulnerabilities in the alternative lengthening of telomeres pathway. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2023, 70, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-M.; Zou, L. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic outlooks. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicanova, L.; Kreilmeier-Berger, T.; Reifinger, M.; Holzmann, K.; Kleiter, M. Prevalence and potentially prognostic value of C-circles associated with alternative lengthening of telomeres in canine appendicular osteosarcoma. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2021, 19, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbarino, J.; Eckroate, J.; Sundaram, R.K.; Jensen, R.B.; Bindra, R.S. Loss of ATRX confers DNA repair defects and PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Translational oncology 2021, 14, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaol, J.C.; Dejnaka, E.; Mucignat, G.; Bajzert, J.; Henklewska, M.; Obmińska-Mrukowicz, B.; Giantin, M.; Pauletto, M.; Zdyrski, C.; Dacasto, M.; et al. PARP inhibitor olaparib induces DNA damage and acts as a drug sensitizer in an in vitro model of canine hematopoietic cancer. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scbt. Daxx Inhibitoren | SCBT - Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Available online: https://www.scbt.com/browse/daxx-inhibitors?pageNum=2 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Scbt. ATRX Inhibitors | SCBT - Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Available online: https://www.scbt.com/browse/atrx-inhibitors?srsltid=AfmBOooT6ZhjNw6OP1KpJZL0COGLr7SItvehYQ1DsYUlz4bwpt7DyrOk (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Singh, D.; Dhiman, V.K.; Pandey, M.; Dhiman, V.K.; Sharma, A.; Pandey, H.; Verma, S.K.; Pandey, R. Personalized medicine: An alternative for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2024, 42, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibuk, J.; Flory, A.; Kruglyak, K.M.; Leibman, N.; Nahama, A.; Dharajiya, N.; van den Boom, D.; Jensen, T.J.; Friedman, J.S.; Shen, M.R.; et al. Horizons in Veterinary Precision Oncology: Fundamentals of Cancer Genomics and Applications of Liquid Biopsy for the Detection, Characterization, and Management of Cancer in Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 664718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).