Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- duration (short-term or long-term);

- insertion site (subclavian, femoral, jugular, basilic, brachial, cephalic);

- number of lumens (single, double, or triple);

- tip characteristics (open or closed);

- materials used to reduce complications (such as heparin, antibiotic, or silver impregnation) [3];

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

2.3. Research Question

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Time Limits

3. Results

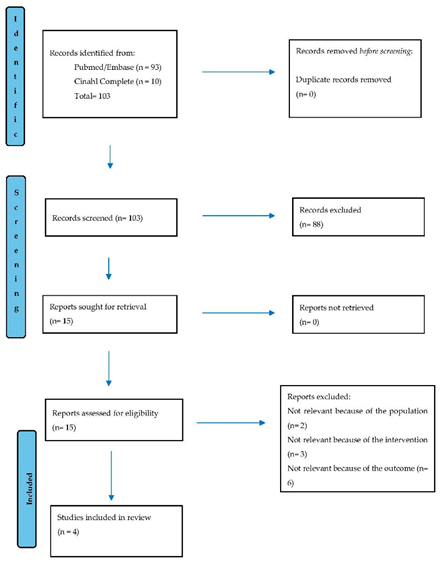

3.1. Study Selection

|

First Author, Country, Year |

Study Design | Population | Number of Participants | Type of Catheter | Clinical Indication for CVC Insertion | Intervention with Chlorhexidine-Impregnated Dressing | Comparison | Definition of CLABSI/ CRBSI (i) | Definition of Catheter Colonization (ii) | Follow-up | Contraindications | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muhterem Duyu, Turkey, 2021 | Parallel-group RCT | Pediatric patients admitted to the PICU with a CVC >48h.. Main pathology : Respiratory failure. |

Intervention group Patients 151 M: 57,6 % F: 42,4 % Range:0-18. Control group Patients:156 M: 55,1 % F : 44,9 % Range:0-18. Mean age: 2 years | Non-tunneled short-term CVC | Administration of heparin and antibiotics | Chlorhexidine dressing: Applied 24h after catheterization, changed every 7 days or as needed | Transparent or standard breathable hypoallergenic dressing. | Bacteremia/fungemia with >1 positive blood culture from a peripheral vein, clinical manifestations of infection, and positive semiquantitative (>15CFU/segment) or quantitative (>10^3 CFU/segment) culture of catheter segment. | 15 CFU from catheter tip culture, without clinical signs of infection and without the same microorganism in blood samples, or when the microorganism isolated from blood differs from that on the catheter tip. | 1 year and 7 months | Contact dermatitis : (p = 0,346) Intervention group (7,2%) Control group (4,4%) |

CLABSI/CRBSI (i) : No statistically significant difference between intervention group and control group (9,9% vs 12,8%; p = 0,767). Catheter Colonization (ii) : Chlorhexidine dressing significantly reduces the incidence of catheter colonization (5,9% vs 12,8%; p = 0,041). |

| Nattapong Jintrungruengnij, Thailand, 2020 |

Parallel-group RCT | Patients with CVC or PICC >48h.. Main pathology : Heart disease |

Intervention group. Patients : 92 M: 51 % F: 49 % Range: 0-18 Control group: Patients : 89 M: 66 % F: 34 % Range: 0-18 Mean age: 2,3 years |

Short-term CVC or PICC | Intravenous therapy. | Chlorhexidine dressing: Applied within 72h after catheterization, changed every 7 days or as needed. | Standard transparent dressing. | Patients showing at least one sign or symptom of bloodstream infection (fever, chills, or hypotension not related to another infection site). | >100 CFU from catheter tip cultures using quantitative methods. | 1 year | Local skin reaction : (p = 0,54) Intervention group (7,5%) Control group (6,0%) |

CLABSI/CRBSI (i) : No statistically significant difference between intervention group and control group (7,98 per 1000 days vs 6,74 per 1000 days p= 0,70). Catheter colonization (ii) : No statistically significant difference between intervention group and control group (2,02 per 1000 days vs 3,07 per 1000 days; p= 0,59). |

| Duygu Sönmez Düzkaya, Turkey, 2016 |

Parallel-group RCT | Pediatric patients admitted to the PICU with CVC >72h.. Main pathology : Respiratory failure. |

Intervention group. Patients : 50 M: 60 % F: 40 % Range: 0-18 Control group. Patients : 50 M: 60 %. F: 40 % Range: 0-18 Mean age: 2,1 years |

Short-term CVC | Parental nutrition and blood transfusions | Chlorhexidine dressing: Applied after CVC insertion and changed every 7 days or as needed. | Sterile pad dressing | >15 CFU growth at catheter tip and microorganism isolated from two blood samples showing the same antibiotic resistance pattern as those from the catheter tip. | >15 CFU growth but no clinical infection signs and negative blood cultures, or blood microorganism different from that on catheter tip. | 2 years | Not specified | CLABSI/CRBSI (i) : No statistically significant difference between intervention group and control group (2% vs 10% p = 0,07) Catheter colonization (ii) : No statistically significant difference between intervention group and control group (2% vs 8% p = 0,07) |

| Itzhak Levy, Israel, 2005 |

Parallel-group RCT | Pediatric patients admitted to the cardiac PICU with CVC>48h. Main pathology : Heart disease |

Intervention group: Patients : 74 M: 34 % F: 66 % Range: 0-18 Control group: Patients : 71 M: 39 %. F: 61 %. Range: 0-18 Mean age: 2-5 years |

Non-tunneled short-term CVC | Fluid administration and blood sampling. | Sponge impregnated with chlorhexidine placed at insertion site, covered with transparent polyurethane, replaced in case of mechanical complications, bleeding or infection signs.. | Standard polyurethane dressing. | Bacteremia without isolation of the same organism from both CVC tip and blood | >15 CFU by roll-plate technique, without local or systemic infection signs. | 1 year and 2 months | Erythema at insertion site : Intervention group (5,4%) Control group (1,5%) |

CLABSI/CRBSI (i) : No statistically significant difference between intervention group and control group (5,4% vs 4,2%; p= 1,00) Catheter colonization (ii) : Chlorhexidine dressing significantly reduces the incidence of catheter colonization (14,8% vs 29,5%; p =0,04) |

3.2. JBI Checklist for the Critical Appraisal of Randomized Clinical Trials

- 2 points if the criterion was met

- 1 point if unclear

- 0 points if not met

- High quality: more than 80% of criteria met

- Moderate quality: 60% to 80% of criteria met

- Low quality: less than 60% of criteria met.

| Internal validity | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection and allocation | Administration of the intervention/exposure | Assessment, detection and measurement of the outcome | Retention of participants | Total score (%) | Validity of the statistical conclusion | ||||||||||||

| Questions | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | ||||

| Duyu et al 2021 | OUTCOME | RESULTS | |||||||||||||||

| CLABSI/CRBSI | 1 year 7 months | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | 22/26 (84,6) | YES | YES | YES | ||

| Catheter colonization | 1 year 7 months | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |||

| Jintrungruengnij et al 2020 | CLABSI/CRBSI | 1 year | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | 22/26 (84,6) | YES | YES | YES | |

| Catheter colonization | 1 year | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |||

| Düzkaya et al 2016 | CLABSI/CRBSI | 2 years | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | 22/26 (84,6) | YES | YES | YES | |

| Catheter colonization | 2 years | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |||

| Levy et al 2005 | CLABSI/CRBSI | 1 year 2 months | YES | NC | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | 21/26 (80,7) | YES | YES | YES | |

| Catheter colonization | 1 year 2 months | YES | NC | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |||

3.3. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.4. Characteristics of the Population

3.5. Characteristics of the Intervention

3.6. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLABSI | Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection |

| CRBSI | Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection |

| CVC | Central Venous Catheter |

References

- Kolikof, J. , Peterson, K., Williams, C., Baker, A.M. ‘Central Venous Catheter Insertion’, in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 4 February (2025).

- Cellini, M. , Bergadano, A., Crocoli, A., Locatelli, F., Cesaro, S., Putti, M.C., Rondelli, R., Vinti, L., Menna, G., Rizzari, C. ‘Guidelines of the Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology for the management of the central venous access devices in pediatric patients with onco-hematological disease’, Journal of Vascular Access, 23(1), (2022) pp. 3–17.

- Cesaro, S. , Caddeo, G. ‘Vascular Access’, in Sureda, A., Corbacioglu, S., Greco, R., Kröger, N., Carreras, E. (eds.), The EBMT Handbook: Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies, 8th ed. Cham (CH): Springer, (2024) pp. 197–201.

- Lee, K. , Ramaswamy, R.S. ‘Intravascular access devices from an interventional radiology perspective: indications, implantation techniques, and optimizing patency’, Transfusion, 58(Suppl 1), (2018) pp. 549–557.

- Cornillon, J. , Martignoles, J.A., Tavernier-Tardy, E., Isnard, F., Thomas, X., Yakoub-Agha, I., Michallet, M., Salles, G., Dhedin, N., Dauriat, G., Garnier, F., Tabrizi, R., Bay, J.O. ‘Prospective evaluation of systematic use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC lines) for the home care after allogenic hematopoietic stem cells transplantation’, Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, (2017) pp. 2843–2847.

- Blanco-Guzman, M.O. ‘Implanted vascular access device options: a focus review on safety and outcomes’, Transfusion, 58, (2018) pp. 558–568.

- Lee, M.M. , Anand, S., Loyd, J.W. ‘Saphenous Vein Cutdown’, in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 4 September (2023).

- Misirlioglu, M. , Yildizdas, D., Yavas, D.P., Ekinci, F., Horoz, O.O., Yontem, A. ‘Central Venous Catheter Insertion for Vascular Access: A 6-year Single-center Experience’, Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 27(10), (2023) pp. 748–753. [CrossRef]

- Ullman, A.J., Cooke, M.L., Mitchell, M., Tran, V., Rickard, C.M., Marsh, N., Mihala, G., Chopra, V., Cheng, A.C. ‘Dressings and securement devices for central venous catheters (CVC)’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(9):CD010367 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, K. , Lathyris, D., Clouva-Molyvdas, P., Papaioannou, V., Malachias, S., Rellos, K., Tsolaki, V., Tripodaki, E., Nanas, S., Dimopoulou, I. ‘Comparison of Oligon catheters and chlorhexidine-impregnated sponges with standard multilumen central venous catheters for prevention of associated colonization and infections in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study’, Critical Care Medicine, 40(2), (2012) pp. 420–429.

- Ho, K.M. , Litton, E. ‘Use of chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing to prevent vascular and epidural catheter colonization and infection: a meta-analysis’, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 58(2), (2006) pp. 281–287. [CrossRef]

- Tingley, K. , Lê, M.L. ‘Chlorhexidine Gluconate for Skin Preparation During Catheter Insertion and Surgical Procedures’, Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, August (2021).

- Jenks, M. , Craig, J., Green, W., Hewitt, N., Arber, M., Sims, A. ‘Tegaderm CHG IV Securement Dressing for Central Venous and Arterial Catheter Insertion Sites: A NICE Medical Technology Guidance’, Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 14(2),(2016) pp. 135–149. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.M. , Bond, E.L., Garman, J.K. ‘Use of a chlorhexidine dressing to reduce microbial colonization of epidural catheters’, Anesthesiology, 73(4), (1990) pp. 625–631. [CrossRef]

- Thokala, P. , Arrowsmith, M., Poku, E., Martyn-St James, M., Anderson, J., Foster, S., Elliott, T., Whitehouse, T. ‘Economic impact of Tegaderm chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) dressing in critically ill patients’, Journal of Infection Prevention, 17(5), (2016) pp. 216–223. [CrossRef]

- O'Grady, N.P. , Alexander, M., Burns, L.A., Dellinger, E.P., Garland, J., Heard, S.O., Lipsett, P.A., Masur, H., Mermel, L.A., Pearson, M.L., Raad, I., Randolph, A.G., Rupp, M.E., Saint, S. ‘Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 52(9), (2011) pp. e162–e193. [CrossRef]

- Prestel, C. , Fike, L., Patel, P., Smith, J., Walker, B. ‘A Review of Pediatric Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network: United States, 2016-2022’, Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, 12(9), (2023)pp. 519–521. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, J.E. , Brilli, R.J., Lake, M.R., Gedeit, R.G., Sparling, K.W. ‘Reducing catheter-associated bloodstream infections in the pediatric intensive care unit: Business case for quality improvement’, Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 11(5), (2010) pp. 579–587. [CrossRef]

- Biasucci, D.G. , Pittiruti, M., Taddei, A., Elia, F., Cogo, P., Cattani, S., Avolio, M., Iorio, R. ‘Targeting zero catheter-related bloodstream infections in pediatric intensive care unit: a retrospective matched case-control study’, Journal of Vascular Access, 19(2), (2018) pp. 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. , Li, Y., Li, X., Bian, L., Wen, Z., Li, M. ‘Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for the prophylaxis of central venous catheter-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, BMC Infectious Diseases, 19(1) (2019):429. [CrossRef]

- Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015);13(3):132-40.

- Duyu M, Karakaya Z, Yazici P, Yavuz S, Yersel NM, Tascilar MO, Firat N, Bozkurt O, Caglar Mocan Y. Comparison of chlorhexidine impregnated dressing and standard dressing for the prevention of central-line associated blood stream infection and colonization in critically ill pediatric patients: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Int. (2022) Jan;64(1):e15011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jitrungruengnij N, Anugulruengkitt S, Rattananupong T, Prinyawat M, Jantarabenjakul W, Wacharachaisurapol N, Chatsuwan T, Janewongwirot P, Suchartlikitwong P, Tawan M, Kanchanabutr P, Pancharoen C, Puthanakit T. Efficacy of chlorhexidine patches on central line-associated bloodstream infections in children. Pediatr Int. 2020 Jul;62(7):789-796. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düzkaya DS, Sahiner NC, Uysal G, Yakut T, Çitak A. Chlorhexidine-Impregnated Dressings and Prevention of Catheter-Associated Bloodstream Infections in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Nurse. (2016) Dec;36(6):e1-e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy I, Katz J, Solter E, Samra Z, Vidne B, Birk E, Ashkenazi S, Dagan O. Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prevention of colonization of central venous catheters in infants and children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2005) Aug;24(8):676-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.P. , Lin, Q.S., Yang, W.Y., Chen, X.J., Liu, F., Chen, X., Ren, Y.Y., Ruan, M., Chen, Y.M., Zhang, L., Zou, Y., Guo, Y., Zhu, X.F. ‘High risk of bloodstream infection of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae carriers in neutropenic children with hematological diseases’, Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control (2023), 12(1):66. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, S.A. , Hirt, P.A., Weigelt, M.A., Nanda, S., de Bedout, V., Kirsner, R.S., Schachner, L.A. ‘Traditional and advanced therapeutic modalities for wounds in the paediatric population: an evidence-based review’, Journal of Wound Care, 29(6), (2020) pp. 321–334. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, 12 April). Updates | Infection Control.

- Xu, H. , Hyun, A., Mihala, G., Rickard, C.M., Cooke, M.L., Lin, F., Mitchell, M., Ullman, A.J. ‘The effectiveness of dressings and securement devices to prevent central venous catheter-associated complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, International Journal of Nursing Studies, (2024) 149:104620. [CrossRef]

- Garland, J.S. , Alex, C.P., Mueller, C.D., Hedlund, T.L., Miller, C.A., Reisinger, K.D., Buck, R.K., Stafford, R.R. ‘A randomized trial comparing povidone-iodine to a chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated dressing for prevention of central venous catheter infections in neonates’, Pediatrics, 107(6), pp. 1431–1 (2001) 436. [CrossRef]

- Pittiruti, M. , Scoppettuolo, G. ‘Raccomandazioni GAVeCeLT 2024 per indicazione, impianto e gestione dei dispositivi per accesso venoso’, Gruppo Aperto di Studio Gli Accessi Venosi Centrali a Lungo Termine (GAVeCeLT). (2024) Documento disponibile online presso IVAS e GAVeCeLT.

- Infusion Nurses Society (INS). Infusion therapy standards of practice. 9th ed. Norwood, MA: Infusion Nurses Society (2024).

- Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ‘Strategies to prevent central line–associated bloodstream infections in acute-care hospitals: 2022 update’,Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 43(5), (2022) pp. 547–585. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, S. L., Stortz, J. A., Mira, J. C., & Moldawer, L. L. Programmed and environmental determinants driving neonatal susceptibility to infection. Immunological Reviews (2023), 311(1), 82396. [CrossRef]

| (P) Population | Pediatric patients with central venous catheter (CVC) |

| (I) Intervention | Use of chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings. |

| (O) Outcome | CLABSI, CRBSI, CVC colonization |

| Database | Search strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Medline/Embase | ('central venous catheter'/exp OR 'axera':ti,ab,kw OR 'broviac':ti,ab,kw OR 'cvp line':ti,ab,kw OR 'careflow (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'cook spectrum (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'groshong':ti,ab,kw OR 'icy (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'logicath':ti,ab,kw OR 'leonard':ti,ab,kw OR 'leonard catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'orion ii':ti,ab,kw OR 'pediasat':ti,ab,kw OR 'powerline (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'powerwand':ti,ab,kw OR 'pro-line':ti,ab,kw OR 'secalon-t':ti,ab,kw OR 'vortex (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'vortex port':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter, central venous':ti,ab,kw OR 'central intravenous catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central line':ti,ab,kw OR 'central vein catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous access catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous access device':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheter, device':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterization kit, short-term':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheters':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous line':ti,ab,kw OR 'cv cath':ti,ab,kw OR 'short-term central venous catheterization kit':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterization'/exp OR 'catheterisation, central venous':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheterization, central venous':ti,ab,kw OR 'central vein catheterisation':ti,ab,kw OR 'central vein catheterization':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterisation':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterization':ti,ab,kw) AND ('chlorhexidine'/exp OR '1, 1 hexamethylenebis [5 (para chlorophenylbiguanide) ]':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 1` hexamethylenebis [5 (4 chlorophenyl) biguanide]':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 1` hexamethylenebis [5 (para chlorophenylbiguanide) ]':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 6 bis (n5 para chlorophenyl n1 diguanido) hexane':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 6 bis [n1 (para chlorophenyl) n5 biguanido] hexane':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 6 di (4` chlorophenyldiguanido) hexane':ti,ab,kw OR 'ay 5312':ti,ab,kw OR 'ay5312':ti,ab,kw OR 'bidex (chlorhexidine)':ti,ab,kw OR 'boston conditioning lotion':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhex':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidin':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine chlorhydrate':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine dihydrochloride':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine glutamate':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine hydrochloride':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohex':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohexidine acetate':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohexydine':ti,ab,kw OR 'clohexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'clorhexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'compound 10040':ti,ab,kw OR 'hexamethylene 1, 6 bis [1 (5 para chlorophenyl) biguanide]':ti,ab,kw OR 'lisium':ti,ab,kw OR 'nibitane':ti,ab,kw OR 'nolvasan':ti,ab,kw OR 'nolvascin':ti,ab,kw OR 'rotersept':ti,ab,kw OR 'sterilon':ti,ab,kw OR 'tubilicid':ti,ab,kw OR 'tubulicid':ti,ab,kw OR 'umbipro':ti,ab,kw) AND ('catheter related bloodstream infection'/exp OR 'clabsi (central line associated bloodstream infection)':ti,ab,kw OR 'clabsis (central line associated bloodstream infections)':ti,ab,kw OR 'crbsi (catheter related bloodstream infection)':ti,ab,kw OR 'crbsis (catheter related bloodstream infections)':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated blood stream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated blood stream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated bloodstream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated bloodstream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related blood stream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related blood stream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related bloodstream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related bloodstream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'central line associated bloodstream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'central line associated bloodstream infections':ti,ab,kw) AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [infant]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim OR [school]/lim) | 93 |

| Cinhal | ('central venous catheter'/exp OR 'axera':ti,ab,kw OR 'broviac':ti,ab,kw OR 'cvp line':ti,ab,kw OR 'careflow (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'cook spectrum (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'groshong':ti,ab,kw OR 'icy (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'logicath':ti,ab,kw OR 'leonard':ti,ab,kw OR 'leonard catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'orion ii':ti,ab,kw OR 'pediasat':ti,ab,kw OR 'powerline (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'powerwand':ti,ab,kw OR 'pro-line':ti,ab,kw OR 'secalon-t':ti,ab,kw OR 'vortex (central venous catheter)':ti,ab,kw OR 'vortex port':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter, central venous':ti,ab,kw OR 'central intravenous catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central line':ti,ab,kw OR 'central vein catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous access catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous access device':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheter':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheter, device':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterization kit, short-term':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheters':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous line':ti,ab,kw OR 'cv cath':ti,ab,kw OR 'short-term central venous catheterization kit':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterization'/exp OR 'catheterisation, central venous':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheterization, central venous':ti,ab,kw OR 'central vein catheterisation':ti,ab,kw OR 'central vein catheterization':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterisation':ti,ab,kw OR 'central venous catheterization':ti,ab,kw) AND ('chlorhexidine'/exp OR '1, 1 hexamethylenebis [5 (para chlorophenylbiguanide) ]':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 1` hexamethylenebis [5 (4 chlorophenyl) biguanide]':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 1` hexamethylenebis [5 (para chlorophenylbiguanide) ]':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 6 bis (n5 para chlorophenyl n1 diguanido) hexane':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 6 bis [n1 (para chlorophenyl) n5 biguanido] hexane':ti,ab,kw OR '1, 6 di (4` chlorophenyldiguanido) hexane':ti,ab,kw OR 'ay 5312':ti,ab,kw OR 'ay5312':ti,ab,kw OR 'bidex (chlorhexidine)':ti,ab,kw OR 'boston conditioning lotion':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhex':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidin':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine chlorhydrate':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine dihydrochloride':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine glutamate':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorhexidine hydrochloride':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohex':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohexidine acetate':ti,ab,kw OR 'chlorohexydine':ti,ab,kw OR 'clohexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'clorhexidine':ti,ab,kw OR 'compound 10040':ti,ab,kw OR 'hexamethylene 1, 6 bis [1 (5 para chlorophenyl) biguanide]':ti,ab,kw OR 'lisium':ti,ab,kw OR 'nibitane':ti,ab,kw OR 'nolvasan':ti,ab,kw OR 'nolvascin':ti,ab,kw OR 'rotersept':ti,ab,kw OR 'sterilon':ti,ab,kw OR 'tubilicid':ti,ab,kw OR 'tubulicid':ti,ab,kw OR 'umbipro':ti,ab,kw) AND ('catheter related bloodstream infection'/exp OR 'clabsi (central line associated bloodstream infection)':ti,ab,kw OR 'clabsis (central line associated bloodstream infections)':ti,ab,kw OR 'crbsi (catheter related bloodstream infection)':ti,ab,kw OR 'crbsis (catheter related bloodstream infections)':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated blood stream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated blood stream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated bloodstream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter associated bloodstream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related blood stream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related blood stream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related bloodstream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'catheter related bloodstream infections':ti,ab,kw OR 'central line associated bloodstream infection':ti,ab,kw OR 'central line associated bloodstream infections':ti,ab,kw) AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [infant]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim OR [school]/lim) | 10 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).