1. Introduction

Rare metals are now the basis of high-tech industry and in wide demand worldwide. One of the most popular rare metals is lithium, used in the production of power supplies for a variety of devices. The rare metals that are in demand include tantalum, tin, beryllium, and cesium, which are used to produce high-tech alloys with a variety of properties. These alloys are then employed in numerous industrial sectors. Given the high demand for these rare metals, the issue of replenishing their reserves is an urgent task, which raises interest in forecasting and searching for new rare-metal deposits.

The ore deposits Li, Ta, Cs, Be, Sn are traditionally associated with rare metal-magmatic systems related to the evolution of granites and associated pegmatite and hydrothermal deposits [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The investigation of granitoids and the evolution of related late- and post-magmatic systems is a significant step towards predicting new rare-metal deposits.

This article presents the results of mineralogical and geochemical studies of granites and related pegmatite and hydrothermal manifestations located in the northwestern part of Kalba-Narym zone, Eastern Kazakhstan. This area is a known rare-metal province where large deposits of rare-metal granite pegmatites with Li-Cs-Ta mineralization have been identified [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The majority of the discovered deposits are concentrated in the central part of the Kalba-Narym zone, while the metallogenic potential of the northwestern part of this zone is not yet well explored.

2. Geological Background

The geological structure of East Kazakhstan was formed in the Late Paleozoic during the collision interaction of the Siberian and Kazakhstan continents, and the closure of the Ob-Zaisan oceanic basin [

13,

14]. The formed geostructure consists of several zones from the northeast to the southwest, each of these zones has a certain set of sedimentary and magmatic formations and corresponding metallogenic specifics. This facilitated the indentification of metallogenic belts [

15,

16] (

Figure 1, a):

1) The Rudny Altai polymetallic belt is composed mainly of volcanogenic rocks formed in the Devonian on the active margin of the Siberian continent;

2) Kalba rare-metal belt, which is a fragment of the passive Carboniferous margin of the Siberian continent, within which many granite intrusions were formed in the early Permian;

3) West -Kalba gold ore belt, which is a fragment of the Devonian-Carboniferous island-arc system, in which numerous gold deposits were formed during the activity of small diorite and granite intrusions in the Late Carboniferous - Early Permian;

4) Zharma-Saur copper-molybdenum belt, which is a fragment of the Silurian-Devonian margin of the Kazakhstan continent with a manifestation of Carboniferous-Permian granitoids.

The most interesting for Li mineralization is the Kalba-Narym rare metal belt, which extends from northwest to southeast for 400 km at a width of approximately 50 km (

Figure 1, b). The main geological formation of this belt is the Kalba granitoid batholith, which is composed of two associations: 1) the Kalba granodiorite-granite complex, formed at an interval of 297-287 million years and 2) the Monastery leucogranite complex, formed at an interval of 283-276 million years [

17]. The main rare metal deposits Li, Cs, Be, Ta, Nb, Sn, and W are concentrated within the Kalba-Narym rare metal belt; the vast majority of them are associated with granites of the Kalba complex. Four ore districts have been identified (

Figure 1, b): Shulbinsk, North-Western Kalba, Central Kalba and Narym. The Central Kalba ore district contains the majority of large explored deposits and is the best studied. The North-Western Kalba district (NWK) has been studied in less detail. Only one Kvartsevoe deposit has been discovered in this area [

12]. Nevertheless, several rare-metal occurrences of pegmatite and hydrothermal origin are known, but have not been explored.

The area of North-Western Kalba is characterized by a slightly dissected relief and good outcrop. The geological structure is shown in

Figure 2. A significant part of the territory is covered by a layer of loose Quaternary deposits, which, nevertheless, has a small thickness, which made it possible to determine the contours of granitoid intrusions during geological surveys [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Most of the granite intrusions of the area belong to the Kalba complex (

Figure 2). Biotite granites of the first phase of the Kalba complex are the most widespread, while biotite-muscovite granites of the second phase of the Kalba complex are less common. Biotite-muscovite leucogranites of the Dungaly intrusion of the Monastery complex are also located in the south-east of the district.

All identified mineralization points are associated with the granites of the Kalba complex. They are represented by manifestations of pegmatites and greisens with Li-Cs-Ta-Be mineralization, as well as hydrothermal veins with Sn-W mineralization. All mineralization manifestations are located in the near-contact or apical parts of granite intrusions, both within granites and among the host siltstones and shales of the Takyr formation. During the geological exploration carried out in the 1970s [

19,

22,

23], rare metal occurrences of the area were classified according to genetic types (

Table 1).

3. Materials and Methods

The scientific study included field and analytical work. Samples from granites, rare-metal pegmatites and greisens (more than 50 samples) were taken for laboratory research. Samples were taken directly from rock outcrops. Analytical studies were performed in the VERITAS laboratory of the D. Serikbayev East-Kazakhstan Technical University (EKTU) (Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan) and the V.S. Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy (IGM) of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Novosibirsk, Russia). Petrographic studies on transparent thin sections were performed at IGM using a Carl Zeiss AxioScope.A1 polarizing light micro-scope equipped with a Canon EOS 650D camera. The images of minerals in backscattered electrons were obtained using a scanning electron microscope (JEOL 100C) with an energy-dispersive attachment (Kevex Ray). For analyses, the beam current was 1 nA, the beam diameter was 10 nm, and the analysis was carried out by scanning an area of 5*5 μm. The live spectrum acquisition time was 60 s. The stability of the survey parameters was con-trolled by periodically measuring the intensity of the K-line of pure cobalt. The correctness of the obtained results was controlled via periodic measurement of the standards used in the calibration.

The content of trace elements and rare metals was determined in EKTU. The samples were dried at a temperature of 105 °C and then ground to a fraction of less than 71 mkm. Before geochemical measurements, the samples were transferred into a solution using polyacid decomposition. During acid decomposition, standard samples of the composition of aqueous solutions of elements were used as calibration solutions. Calibration solutions were prepared by diluting standard samples with a solution of nitric acid with a molar concentration of 1 mol/dm3, a mass concentration of 2% or 5%; hydrochloric acid solution with a mass concentration of 10% or water. A solution of nitric acid with a mass concentration of 5% was used as a background solution. The analyses were performed at the VERITAS Laboratory of the EKTU. The compositions of rocks and minerals were determined, respectively, by mass spectrometry with inductively coupled plasma (ICP-MS) on an Agilent 7500cx (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which determines 73 elements with high sensitivity.

4. Rare Metal Mineralization of North-Western Kalba

4.1. Granites of North-Western Kalba

The granites of the Kalba complex are represented by three varieties within the studied area. The granite of the first phase of the Kalba complex is predominant. They are represented by medium- and fine-grained biotite granites. (

Figure 3, a). They contain about 40-50 vol.% plagioclase and potassium feldspar forming subidiomorphic grains. Potassium feldspar is usually predominant compared to plagioclase. Quartz occupies from 35 to 45 vol.%, forming xenomorphic grains. Biotite forms subidiomorphic flake grains (amount reaches 10-12 vol.%). Muscovite occurs rarely, in interstitials between early minerals (amount does not exceed 2 vol.%). The sequence of mineral formation has been established: Pl + Kfs + Bt → Otz → Ms.

The second phase of the Kalba complex is represented by biotite-muscovite medium-grained granites (

Figure 3, b), which form small intrusive bodies among the granites of the first phase. Plagioclase and potassium feldspar predominate in these rocks, occupying a total of about 50 vol.%. Quartz occupies up to 40 vol.% and is represented by xenomorphic grains. Biotite forms small subidiomorphic flaky grains, its amount does not exceed 5 vol.%. Muscovite is found everywhere, and forms large flaky grains in interstices between early minerals; its amount can reach 15 vol.%. The sequence of mineral formation has been established: Pl + Kfs + Bt → Otz + Ms.

Granite veins, which belong to the third phase, break through the granites of both the first and second phases. They are represented mainly by fine-grained muscovite granites (

Figure 3, c). Plagioclase is the predominant mineral; its idiomorphic grains occupy up to 60 vol. %. Potassium feldspar occupies no more than 15 vol. %, and forms weakly idiomorphic grains. Quartz forms xenomorphic grains, its amount does not exceed 20 vol. %. Muscovite is present everywhere in the interstices as a late magmatic mineral, its amount varies from 1-2 vol. % to 10-12 vol. %. Biotite has not been found in any type of rocks of the third phase. Dark-colored minerals in some muscovite granite samples are represented by idiomorphic garnet grains

Figure 3, d), in addition, single idiomorphic tourmaline grains are occasionally found. The sequence of mineral formation is established: (Turm) + Grt → Pl → Kfs + Otz → Ms.

The composition of the studied granite samples is given in

Table 2. All studied granites are characterized by the predominance of LREE over HREE, this difference is best expressed in biotite granites of the 1st phase (

Figure 4, a). Biotite-muscovite granites of the second phase show reduced REE contents relative to the rocks of the first phase. Muscovite granites of the third phase have wide variations in REE contents, but for most samples they are lower than in granites of the first phase. On the spider diagram (

Figure 4, c) granites of all phases show increased concentrations of LILE (Cs, Rb) and HFSE (Hf, Zr), minima in Ba and Yb contents, and maxima in U, Ta, and Nb contents. For muscovite granites of the 3rd phase, the maximum in Ta content is clearly distinguished (

Figure 4, b, c). A comparison of the concentration of rare metals shows that in general there are no fundamental differences between granites of different phases, however, nevertheless, some samples of muscovite granites of the 3rd phase differ from granites of the 1st and 2nd phases with increased concentrations of Ta, Nb, Mo, and reduced concentrations of Li (

Figure 4, b).

4.2. Rare Metal Pegmatite Deposits

The greatest interest in the area is attracted by the veins of rare-metal pegmatites [

16,

19], which, according to the prevailing mineral assemblages, can be divided into the following types: microcline with beryl, albite with tantalite and beryl, microcline-

albite with spodumene (

Table 1). Veins can often have the zonal structure. Different associations can be gathered in one large vein. Here and further, we mean that pegmatites can be found within the same veins, as sections of veins composed mainly of an association of feldspar and quartz; and greisens can also be found, as sections of veins composed of a mineral association with a predominance of mica (muscovite).

The Kvartsevoye deposit is the most studied and explored. It is located in the endocontact of a granite intrusion composed of biotite granites of the 1st phase of the Kalba complex. The deposit consists of a series of pegmatite veins break through granites; the main mineralization is represented by spodumene, tantalite and accessory cassiterite, concentrated in the largest Main vein. The results of a study of the mineral assemblages and rock composition of the Kvartsevoye deposit have recently been published in [

12]. The following section will provide detailed description of other ore occurrences in the NWK area.

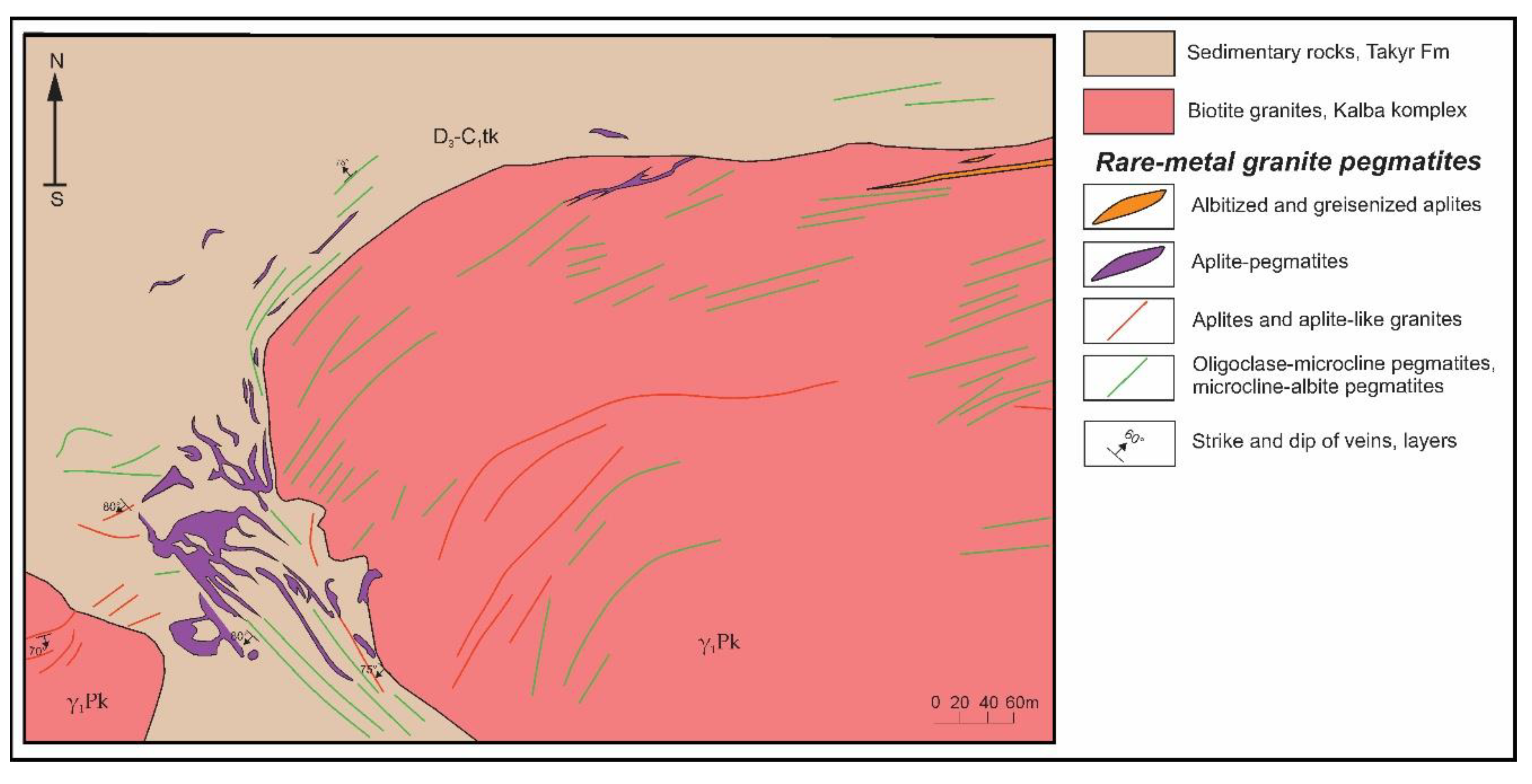

The Alypkel ore occurrence is located northwest from the Kvartsevoye deposit and located near the western edge of the Alypkel granite intrusion. Pegmatite veins break through both the granites of the 1st phase of the Kalba complex and the host siltstones of the Takyr formation (

Figure 5). The veins have a NW or NE strike, and are oriented almost vertically. The thickness of the largest pegmatite veins is several meters, the largest is up to 15 m. Most of the veins are composed by oligoclase–microcline and microcline–albite pegmatites. Rare-metal pegmatites are represented by microcline-albite types, in which beryl mineralization occurs. Exploration wells within the Alypkel ore occurrence have uncovered veins of quartz-albite-spodumene pegmatites, which contain up to 25-30% spodumene, and are characterized by elevated concentrations of Li, Be, and Sn. In addition to beryl and cassiterite, accessory galena and sphalerite are found in granites and pegmatites (

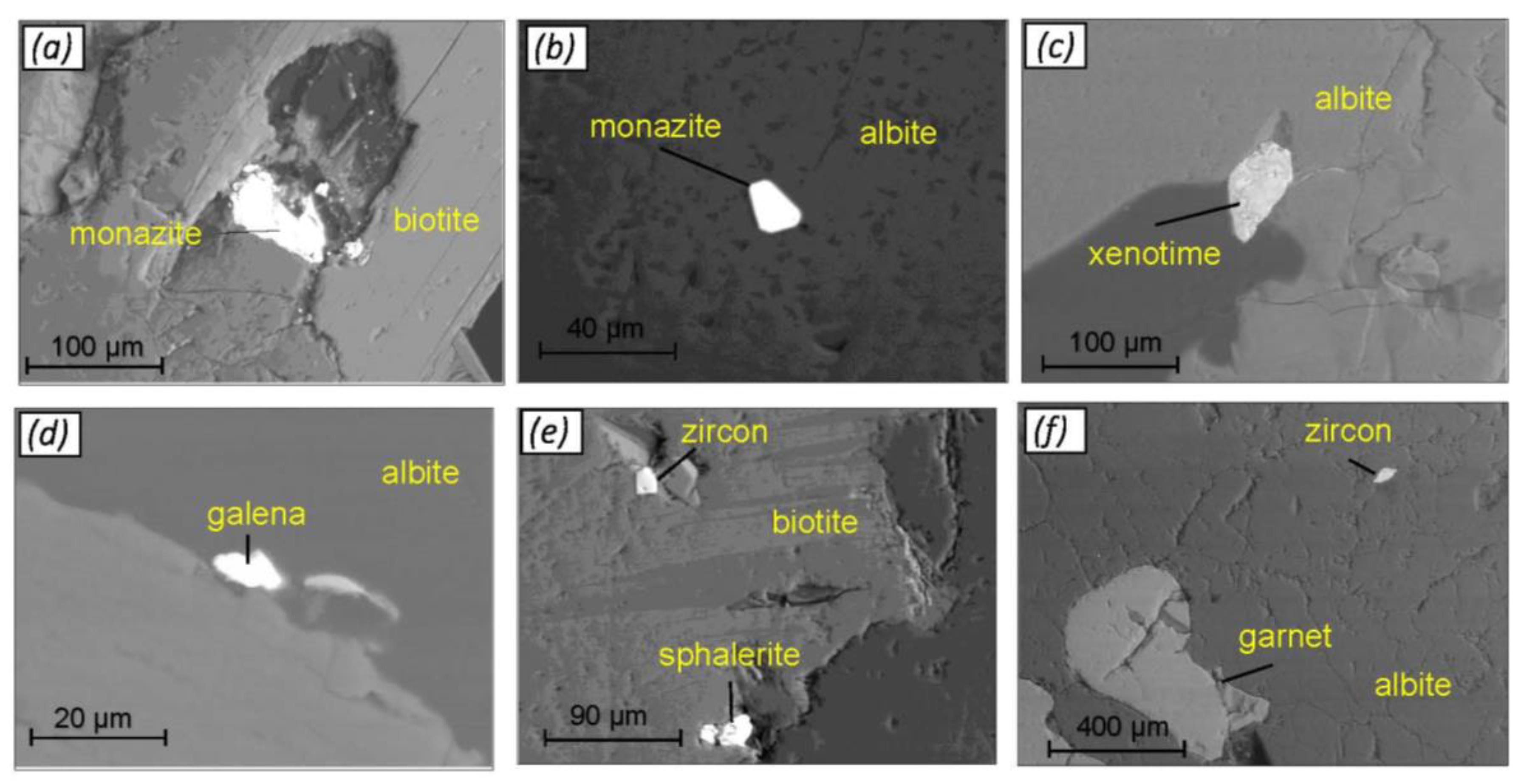

Figure 6).

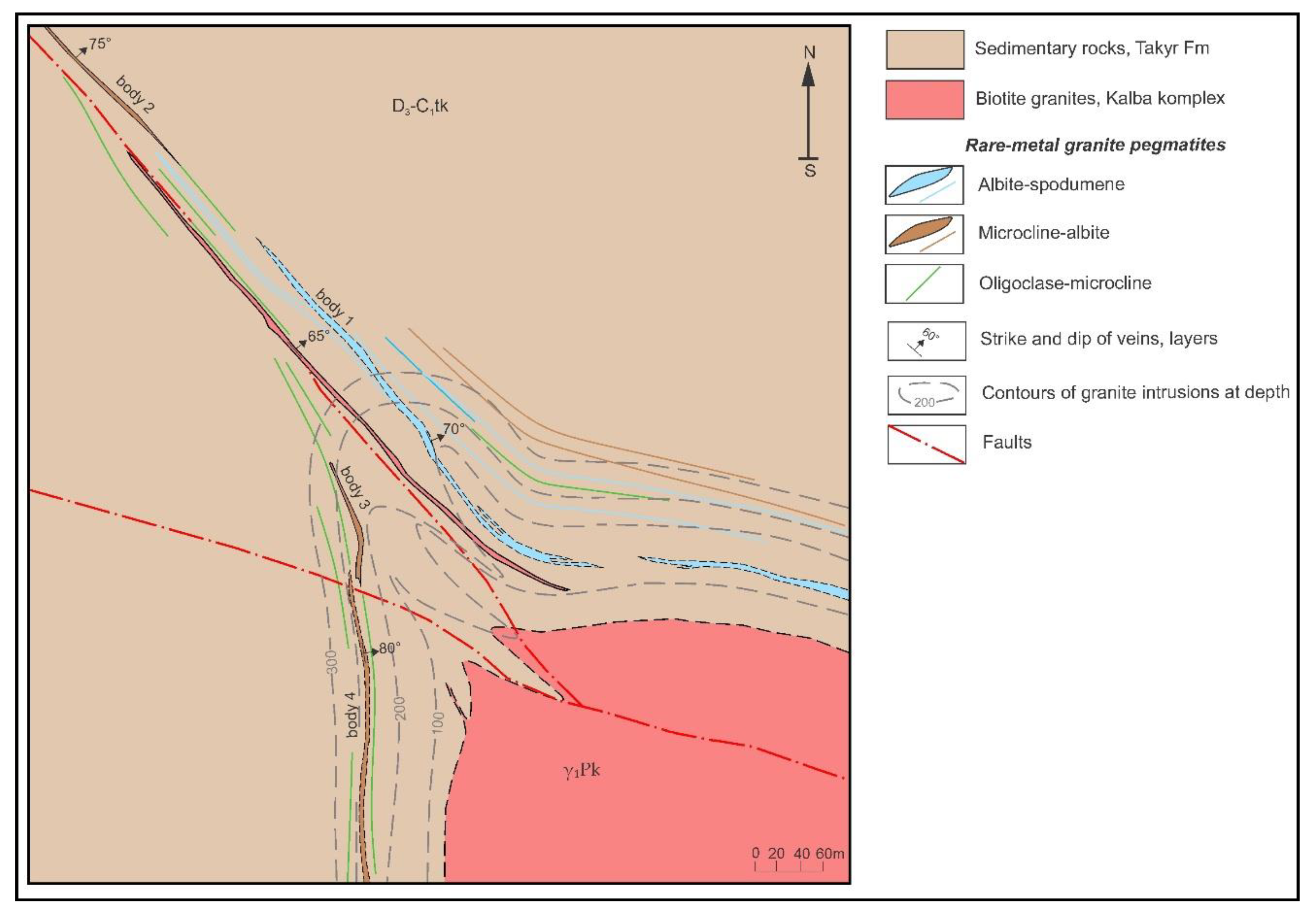

The Kovalevskoye ore occurrence is located northeast from the Kvartsevoye deposit and is situated in the super-intrusive zone of the northwestern part of the South-Kovalevskoye intrusion. It is represented by several subvertical veins of the northwestern strike associated with the fault (

Figure 7). Rare metal veins are composed of microcline-albite and albite-spodumene assemblages. Albitization is observed in the veins, which is expressed in the formation of clusters of fine-crystalline albite and greisenization, which is expressed in the formation of clusters of greenish muscovite. The spodumene content in the veins reaches up to 60-70% in thickest sections and up to 3-5% where the vein thickness decreases. Columbite is present as an accessory ore mineral (

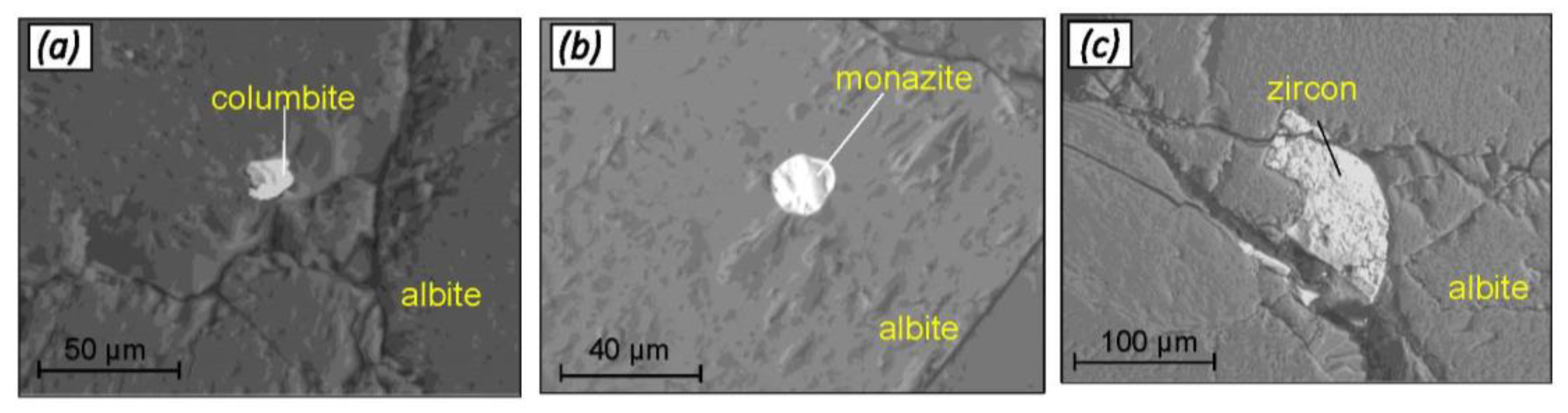

Figure 8).

The Aktobe ore occurrence is located 5 km southwest from the Kvartsevoye deposit and consists of a series of pegmatite veins break through shales of the Takyr formation between the Nikolaevsky and Central granite intrusions (

Figure 9). The veins exhibit a predominantly submeridional or north-western strike. A wide variety of pegmatite mineral assemblages have been identified here: 1) simple microcline pegmatites; 2) microcline-albite pegmatites without spodumene; 3) microcline-albite pegmatites with spodumene; 4) albite pegmatites without spodumene; 5) albite pegmatites with spodumene.

The veins of rare-metal pegmatites do not exhibit pronounced zonation, and their structure is more consistent with aplite-pegmatites. With increasing thickness, coarser-grained rock structures appear in the veins, and the amount of spodumene and fine-flake muscovite also increases in the more powerful sections of the veins.

Albite-type pegmatites are of the greatest interest, in which spodumene is present in all areas. In the largest Moschnaya vein, the amount of spodumene can reach 50-60%, and the albite-spodumene mineral association is manifested here. The Powerful vein also contains iron-manganese phosphates in the form of 5-6 mm nests. The average content of Ta2O5 in the Moschnaya vein is 0.0035%, Be – 0.053%, Li – 0.005%. The second largest vein is the Vetvistaya, which is composed of albite-microcline pegmatite without spodumene with non-uniform albitization and greisenization. The weighted average content of Ta2O5 in it is 0.0049%; BeO is 0.036%. Sphalerite, columbite, and chalcopyrite have been identified in the form of microinclusions in the veins of Aktobe (

Figure 10).

3.2. Hydrothermal deposits

Hydrothermal deposits are widespread in the northern and eastern parts of the studied area (

Figure 2). They are mostly located away from pegmatite deposits, but they are also associated with granite intrusions. The most promising of these is the Kaindy group of deposits, which are associated with the granites of the Kaindy intrusion.

Several large quartz veins have been identified in the Kaindy ore field, breaking through the shales of the Takyr formation in the exocontact of the granite intrusion (

Figure 11). Quartz veins have a north-west strike, stretch for hundreds of meters and have a thickness of up to 2-3 meters. The largest quartz veins contain tungsten and tin-tungsten mineralization. The ore mineralization is represented by wolframite, less often cassiterite and scheelite (

Figure 12).

The largest is the Novo-Kaindy ore occurrence with concentrations of WO

3 – 0.7%, Sn-0.3% and an average ore body thickness of 1 m. They contain Li (0.001 – 0.002%), Sn (0.001 – 0.004%), and WO

3 – up to 0.36%. According to the results of the preliminary geological exploration assessment [

23], the projected resources of the Kaindy ore field may amount to 30.8 tons of WO

3.

6. Discussion

Based on the patterns of deposit and ore occurrence in the North-Western Kalba region, as well as the relationship between different rock types within their boundaries, it can be suggested that rare metal deposits and occurrences are genetically linked to the granites of the Kalba complex. This hypothesis is supported by the following evidence.

Firstly, geological observations indicate that nowhere in North-Western Kalba have swarms of pegmatite veins been found without granite manifestations nearby. Conversely, veins of rare-metal pegmatites are always located near Kalba granites, in endocontact or exocontact zones of intrusions.

The second piece of evidence is geochronological data. Although we did not perform any special geochronological studies in this paper, we have data on the age of rare-metal pegmatites from the Kvartsevoye deposit (285-288 Ma, [

12]) and rare-metal deposits from the Asubulak ore region in Central Kalba (295-286 Ma, [

7]). These age values are congruent with, or only slightly younger than the age values of the granite of the Kalba complex (297-287 Ma, [

17]). This suggests that the formation of granites and rare metal mineralization was the result of a single endogenous event.

The third piece of evidence for the connection between Kalba granites and rare-metal pegmatites is mineralogical and geochemical. Based on the samples we studied, Kalba granites are represented by three intrusive phases: biotite granites of the first phase, which occupy the largest volume, biotite-muscovite granites of the second phase, which occupy a smaller volume, and muscovite granites of the third phase, represented by vein bodies; the volume of granites of the third phase is comparable to the volume of pegmatite veins.

Petrographic observations indicate that the proportion of muscovite increases from early to late granites, and the predominance of plagioclase over feldspar increases. This is evidence of the accumulation of sodium, alumina, and volatile components during magmatic differentiation in the melt. Geochemical data on the main components also indicate a decrease in the content of mafic components and potassium and an increase in the proportion of silica in granites of the 3rd phase compared with granites of the 1st and 2nd phases. Such an evolution of granite magmas leads to the replacement of potassium feldspar with albite and the appearance of garnet as an aluminum-concentrating phase, in addition, such an evolution of granite melts facilitates the transport of elements such as Sn, Ta, Nb, and Be [

25].

The concentration of rare earth elements in most samples of muscovite granites of the 3rd phase is lower than in granites of the 1st and 2nd phases (

Figure 4, a). This indicates the fractionation of REE concentrating minerals, including biotite and accessory apatite, monazite, zircon, and xenotime during the evolution of the parental granite magma.

Concurrently, muscovite granites of the 3rd phase exhibit elevated concentrations of Ta, Nb, and Mo in comparison with granites of the 1st and 2nd phases (

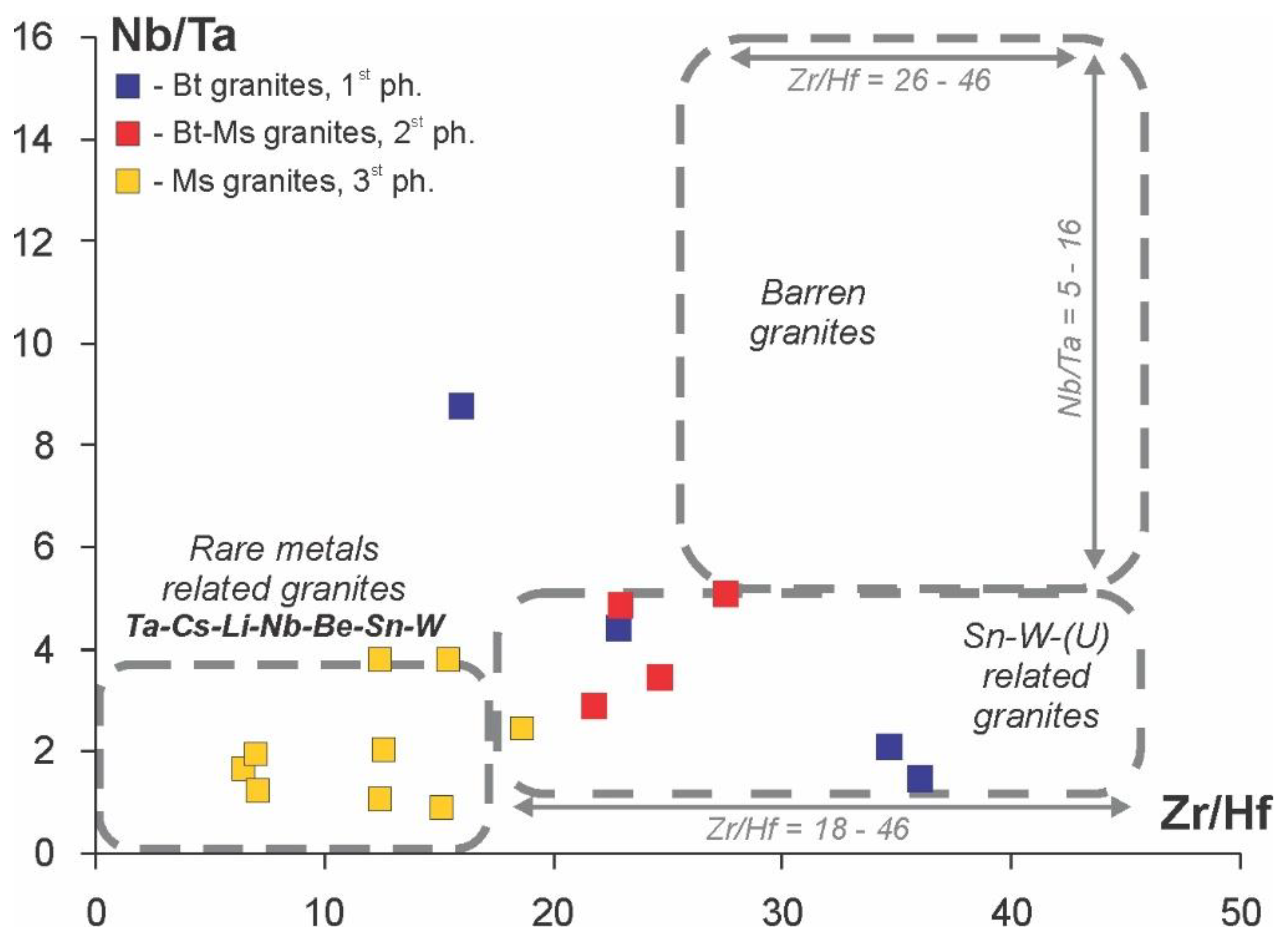

Figure 4, b), suggesting the accumulation of these elements in a residual melt rich in volatile components. Futhermore, the results of geochemical studies of granites show that the Nb/Ta and Zr/Hf ratios are a key indicator of magmatic fractionation [

26]. The Nb/Ta value < 5 is an indicator of the interaction of magma with late magmatic fluids [

27]. For the studied Kalba granites, the Nb/Ta ratio is 1.45 – 8.75 in Bt granites of the 1st phase, 2.88 – 5.05 in Bt-Ms granites of the 2nd phase, and 0.87 – 3.77 in Ms granites of the 3rd phase. The Nb/Ta vs Zr/Hf diagram shows that the granites of northwestern Kalba demonstrate the process of fractional crystallization, and the muscovite granites of the 3rd phase correspond to rare metal related granites with the Ta-Cs-Li-Nb-Be-Sn-W mineralization (

Figure 13).

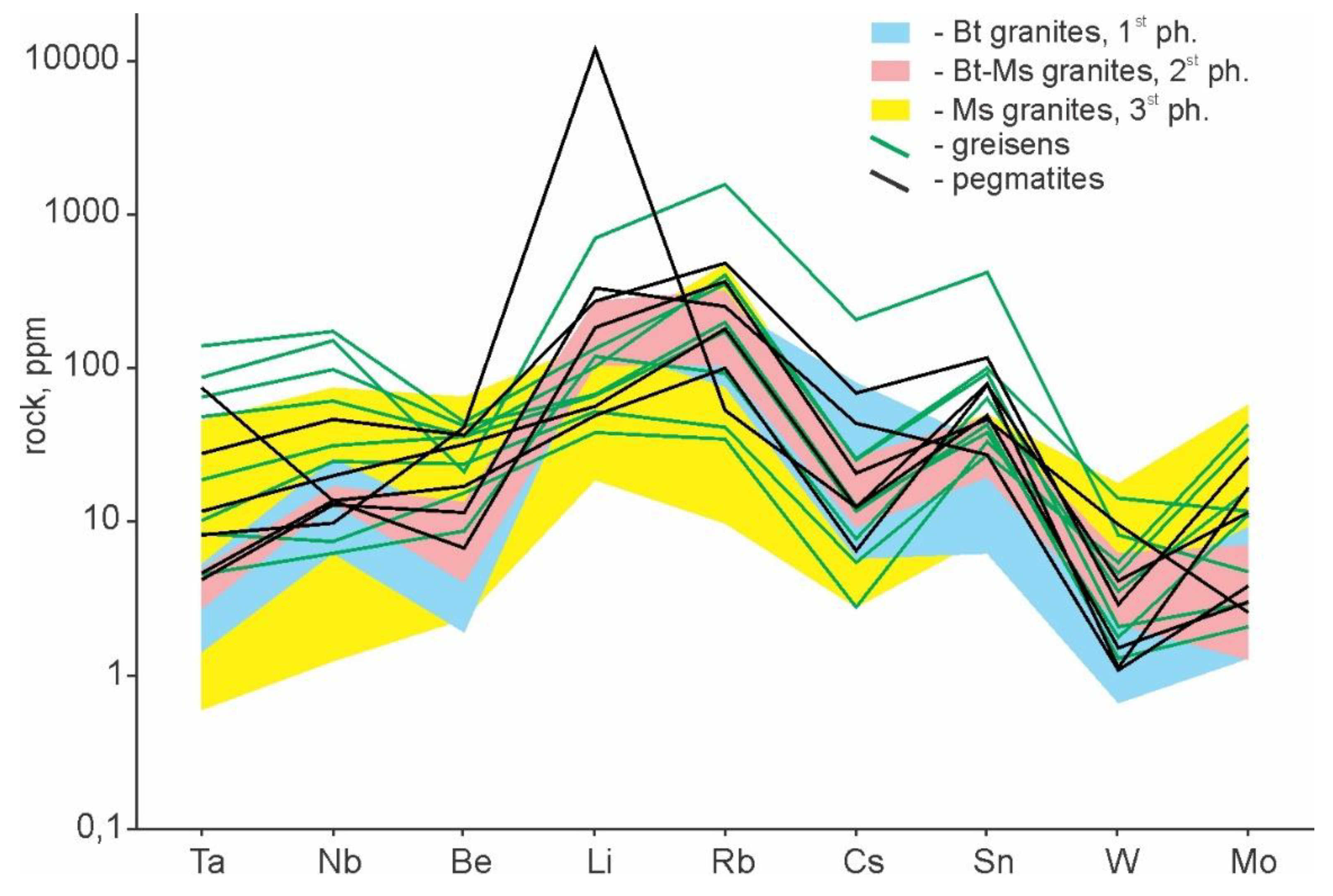

The content of rare metals in the studied samples of pegmatites and greisens is shown in

Table 3. As shown in

Figure 14, a comparison has been made of the contents of rare metals in granites and pegmatites. Most samples of pegmatites and greisens are characterized by high concentrations of Ta, Nb, Be, and Mo, which are the same as or higher than in some samples of muscovite granites of the 3rd phase. Sn concentrations in most samples of pegmatites and greisens are higher than in granites. Li concentrations are high only in spodumene-containing varieties. At the same time, the concentrations of Rb, Cs, and W are almost identical to those in granites.

The data demonstrate a gradual evolution of the parental granitic magma from biotite granites to biotite–muscovite and muscovite granites, and then to pegmatites. At the initial stages of evolution, Na, Al, and volatile components accumulated in the residual melts, which contributed to the concentration of rare metals. At the later stages of evolution, albite and spodumene crystallized, which allowed the formation of albite-spodumene pegmatites, and the accumulation of volatiles in the remaining mobile phase led to the crystallization of greisen associations enriched in Ta, Nb, Be, Sn, Mo. Pegmatites and greisen did not concentrate W, it can be assumed that W was mainly concentrated in the residual hydrous fluid. This fluid subsequently crystallized in the form of hydrothermal quartz W-bearing veins during the final stages of evolution.

6. Conclusions

It can be argued that all the rare metal deposits of North-Western Kalba were formed during a single process of differentiation of the parental magmas of Kalba granites – from pegmatites to greisen and to hydrothermal deposits. Similar models have been proposed previously for the Central Kalba ore region [

6,

10] as well as for rare metal pegmatite deposits in Thailand [

28], Vietnam [

29] and China [

4,

30].

This allows us to consider the North-Western Kalba region as promising for the discovery of new rare metal deposits. During exploration, special attention should be paid to exocontact zones of non-exposed granite intrusions, as well as zones of development of W-bearing quartz veins, under which rare-metal pegmatites may be located at depth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.O. and S.V.K.; methodology, S.V.K.; software, T.A.O.; validation, T.A.O. and S.V.K.; formal analysis, T.A.O. and S.V.K.; investigation, T.A.O.; resources, T.A.O.; data curation, T.A.O. and S.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V.K. and T.A.O.; writing—review and editing, S.V.K. and T.A.O.; visualization, T.A.O.; supervision, T.A.O.; project administration, T.A.O.; funding acquisition, T.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP19676805) and by the State Assignment of IGM SB RAS (Project No 122041400044-2).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the VERITAS Engineering Laboratory (EKTU) and the Analytical Center (IGM) for the analytical work. Our thanks are extended to Alexey Volosov for their aid in the manuscript’s preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cerny, P. Rare-element granitic pegmatites. Part I: Anatomy and internal evolution of pegmatite deposits. Geosci. Can. 1991, 18, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- London, D. Ore-forming processes within granitic pegmatites. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 101, 349–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B. Formation of tin ore deposits: A reassessment. Lithos. 1057. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Pan, H.; Li, C.; Feng, H.; He, L.; Bai, Y.; Luo, Y.Q.; Suo, Q.Y.; Cao, C. Newly-recognized Triassic highly fractionated leucogranite in the Koktokay deposit (Altai, China): Raremetal fertility and connection with the No. 3 pegmatite. Gondwana Res. 2022, 112, 24–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losantos, E.; Borrajo, I.; Losada, I.; Boixet, L.; Castelo Branco, J.M.; Tornos, F. Sn and W mineralisation in the Iberian Peninsula. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 179, 106542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’yachkov, B. A. Genetic Types of Rare-Metal Deposits in the Kalba-Narym Belt. EKSTU: Ust-Kamenogorsk. Kazakhstan.

- Khromykh, S.V.; Oitseva, T.A.; Kotler, P.D.; D’yachkov, B.A.; Smirnov, S.Z. et. al. Rare-Metal Pegmatite Deposits of the Kalba Region, Eastern Kazakhstan: Age, Composition and Petrogenetic Implications. Minerals 2020, 10, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachkov, B.A.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Mizernaya, M.A.; Khromykh, S.V.; Oitseva, T.A.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Zimanovskaya, N.A.; Aitbayeva, S.S. Mineralogical tracers of gold and rare-metal mineralization in Eastern Kazakhstan. Minerals. 2021, 3, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimanovskaya, N.A.; Oitseva, T.A.; Khromykh, S.V.; Travin, A.V.; Bissatova, A.Y.; et. al. Geology, Mineralogy, and Age of Li-Bearing Pegmatites: Case Study of Tochka Deposit (East Kazakhstan). Minerals 2022, 12, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oitseva, T.A.; D’yachkov, B.A.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Ageeva, O.V. New data on the substantial composition of Kalba rare metal deposits. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 110, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absametov, M.K. , Boyarko, G.Yu., Dutova, E.M., Bolsunovskaya, L.M., Itemen, N.M., Chenzybaev, D.B. Lithium capacity of Kazakhstan mineral resource base. Bull. of the Tomsk Polytech. Univ. Geo Assets Engin.

- Oitseva, T. A.; Khromykh, S. V.; Naryzhnova, A. V.; Kotler, P. D.; Mizernaya, M. A.; Kuzmina, O. N.; Dremov, A. K. Rare Metal (Li–Ta–Nb) Mineralization and Age of the Kvartsevoye Pegmatite Deposit (Eastern Kazakhstan). Minerals. 2025, 15, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, A.G.; Kruk, N.N.; Khromykh, S.V.; Polyansky, O.P.; Chervov, V.V.; Vladimirov, V.G.; Travin, A.V.; Babin, G.A.; Kuibida, M.L.; Khomyakov, V.D. Permian magmatism and lithospheric deformation in the Altai caused by crustal and mantle thermal processes. Russ. Geol. and Geoph. 2008, 49(7), 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V. Basic and associated granitoid magmatism and geodynamic evolution of the Altai accretion–collision system (Eastern Kazakhstan). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2022, 63(3), 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherba, G.N.; Dʹyachkov, B.A.; Stuchevsky, N.I.; Nakhtigal, G.P.; Antonenko, A.N.; Lubetsky, V.N. Great Altai: Geology and Metallogeny. Book 1. Geological Construction; Gylym: Almaty. 1998; 304р.

- D’yachkov, B.A.; Mizernaya, M.A.; Khromykh, S.V.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Oitseva, T.A.; Miroshnikova, A.P.; Frolova, O.V.; Kuzmina, O.N.; Zimanovskaya, N.A.; Pyatkova, A.P.; et al. Geological History of the Great Altai: Implications for Mineral Exploration. Minerals 2022, 12, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.D.; Khromykh, S.V.; Kruk, N.N.; Sun, M.; Li, P.; Khubanov, V.B.; Semenova, D.V.; Vladimirov, A. Granitoids of the Kalba batholith, Eastern Kazakhstan: U–Pb zircon age, petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Lithos 2021, 188–389, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatnikov, V.V.; Izokh, E.P.; Ermolov, P.V.; Ponomareva, A.P.; Stepanov, A.S. Magmatism and ore content of the Kalba-Narym zone of Eastern Kazakhstan. Moscow: Nauka.

- Kashcheev, V.F. Report on the search for complex beryllium-tantalum ores in the northwestern part of the Kalba rare metal region in the Aktobe area for 1984-1987. Ust-Kamenogorsk: Vostkazgeology.

- Lopatnikov, V. V.; Nechaev, A. V.; Nikolenko, A. E.; Mayorova, N. P. Geological structure and useful minerals of sheets M-44-95-A, B. Ust-Kamenogorsk: Vostkazgeology.

- Miletin, V. I.; Pushko, E. P.; Sugak V., S. Report on prospecting, exploration and geochemical work of the Irtysh GRP for 1964-65. Ust-Kamenogorsk: Vostkazgeology.

- Ermolin, V. T.; Pushko, E. P.; Rybalchenko, N. G.; Yaroshenko, O. N. Report of the Irtysh geological exploration party on the results of prospecting work in North Western Kalba for 1965 - 1969 (sections Kvartsevoye, Aktobe, Bekkuduk, Izmailovsky, Kovalevsky, Nikolaevsky, Sotschigiz, Ak-Tobe). Ust-Kamenogorsk: Vostkazgeology.

- Maslov, V.I.; Vvedensky, R.V.; Lutsky, B.M.; Trofimov, S.A. Report of geological exploration within Delbegetei, Kaindy, Izmailovo sites at the 1978-1984. Ust-Kamenogorsk: Vostkazgeology.

- Sun, S.-S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. Geolog. Society, London, Spec. Publ, 42.

- Canosa, F.; Martin-Izard, A.; Fuertes-Fuente, M. Evolved granitic systems as a source of rare-element deposits: The Ponte Segade case (Galicia, NW Spain). Lithos. 2012, 153, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, X.; Ji, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, L. Highly fractionated granites: Recognition and research. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouard, C.; Poujol, M.; Boulvais, P.; Branquet, Y.; Tartèse, R.; Vigneresse, J.L. Nb-Ta fractionation in peraluminous granites: A marker of the magmatic-hydrothermal transition. Geology. 2016, 44(3), 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanka, Al.; Tadthai, J. Petrology and geochemistry of Li-bearing pegmatites and related granitic rocks in southern Thailand: implications for petrogenesis and lithium potential in Thailand. Front. in Earth Sc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hien-Dinh, T. T.; Dao, D. A.; Tran, T.; Wahl, M.; Stein, E.; and Giere, R. Lithium-rich albite-topaz-lepidolite granite from central Vietnam: A mineralogical and geochemical characterization. Eur. J. Mineral. 2017, 29, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.-Y.; Romer, R.L.; Zhang, H.-X.; Wan, S.-L. Characteristics and formation of rare-metal pegmatites and granites in the Duanfengshan-Guanyuan district of the northern Mufushan granite complex in South China. Lithos. 1075. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).