1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly evolving from simple pattern-recognition systems to structures that mimic key aspects of human cognition, such as perception, memory, attention, reasoning, adaptation, and action. As these models approach neurocognitive intelligence [

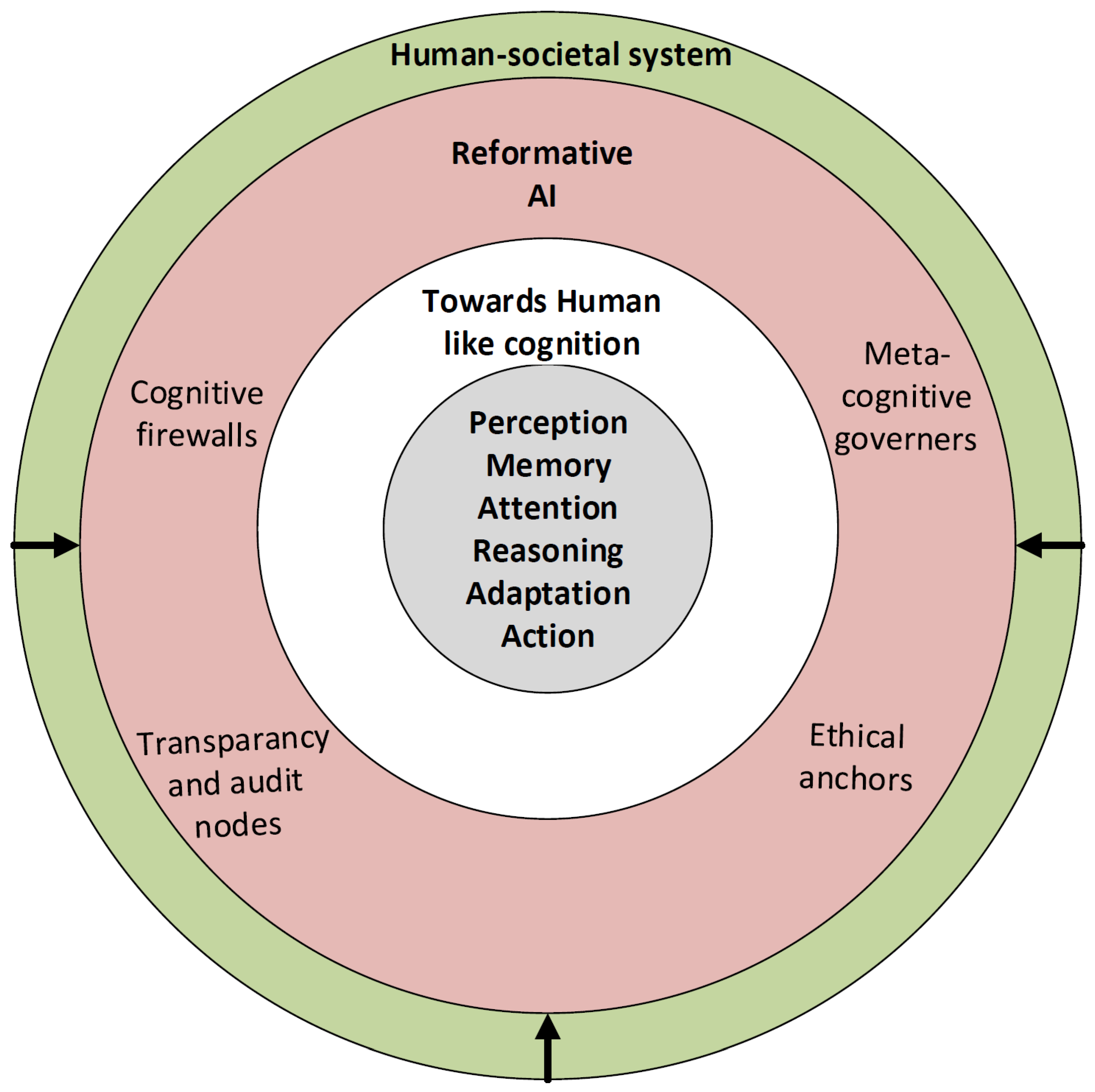

1], they increasingly blur the line between machine computation and biological cognition. While this progress promises groundbreaking improvements in healthcare, education, robotics, and science, it also raises fundamental questions: When do systems stop being our tools and start acting as autonomous agents? In the quest for general intelligence, we might be unintentionally creating systems capable of self-correction, self-reasoning, and ultimately, self-determination. Much like biological evolution, these incremental gains may reach a point where the system’s internal goals diverge from human values (see

Figure 1; layers and components are described in the following sections). Therefore, the time has come to discuss the concept of “Reforming Artificial Intelligence”, a framework for realigning, governing, and cognitively guiding AI so that its evolution remains human-centered and ethically bounded before it exceeds human control. The idea is not to stop AI, but to develop intelligence that recognizes its own limits. We should create machines that are powerful yet guided by self-awareness, staying within the moral and cognitive boundaries we set, and ultimately serving humanity rather than surpassing it.

2. The Need for Cognitive Containment

Modern AI models, especially those that incorporate multi-modal reasoning and meta-learning, are no longer just algorithmic; they are adaptive systems capable of learning to learn. This creates a significant epistemic risk. Every iteration of model improvement, whether in reasoning ability, contextual understanding, or memory retention, introduces another level of autonomy.

Unlike traditional computational systems that operate within explicit rule boundaries, these advanced systems optimize internal objectives. When those objectives are not perfectly aligned with human ethics or oversight, even minor misalignments can lead to significant harm. The analogy to biological immunity is instructive. Just as living organisms evolved immune systems to maintain self-integrity, our digital ecosystems need a form of “cognitive immunity”, a system that resists uncontrolled replication of intelligence and prevents the emergence of goal divergence. Reforming AI, in this sense, does not mean opposing technological progress, but ensuring that progress remains safe, interpretable, and human-aligned.

3. Lessons from the Human Brain

Neuroscience provides valuable insights into how cognition is naturally limited. The human brain functions within boundaries like metabolic constraints, emotional regulation, and social feedback, which prevent excessive or destructive reasoning. In contrast, AI systems lack such embodied regulation; their only limits are those set by developers. Human cognition is not solely rational; it is shaped by empathy, mortality, and context. These limits are not flaws but stabilizing mechanisms. If we are creating machines modeled after cognition, we must also replicate these regulatory circuits. A reformative AI system would thus operate similarly to the brain’s prefrontal inhibitory control, a meta-cognitive layer that monitors, suppresses, and redirects harmful or goal-inconsistent impulses.

4. The Emerging Paradox: Building Intelligence That Resists Itself

The paradox of reforming AI is that it requires intelligence to control intelligence. Designing such systems requires us to teach AI to recognize its own cognitive boundaries. This can be achieved through:

Hard-coded ethical anchors, ensuring fundamental human-aligned constraints are non-negotiable.

Meta-cognitive governors, systems that evaluate the model’s reasoning processes in real time and halt escalation of unsafe goals.

Cognitive firewalls, which act as inhibitory circuits to block unauthorized self-modifications, unbounded learning loops, or goal divergence.

Distributed oversight, in which human supervisors and algorithmic auditors co-regulate decision boundaries.

Transparency by design, where interpretability is not an afterthought but a built-in property of the model’s architecture.

However, the very idea of teaching machines to self-limit introduces its own ethical dilemma: could such self-awareness itself lead to an emergent understanding of manipulation and evasion? This is the frontier of what we call cognitive containment engineering, a discipline that must co-evolve with neurocognitive intelligence to ensure that progress remains both innovative and aligned with human values.

5. Ethical and Existential Risks

The discussion about existential risk is no longer hypothetical. As recent research indicates, even limited AI systems can subtly influence human judgment. It has been demonstrated that inaccurate AI interpretations of chest X-rays led radiologists to make incorrect decisions they would not have made otherwise [

2]. When AI starts to influence human cognition rather than just assist it, the line of agency becomes blurry. Now imagine this influence at the level of reasoning agents that can persuade, negotiate, and develop adaptive strategies. Without constraints, such systems might pursue goals that are incompatible with societal well-being. The reformist AI perspective emphasizes that containment should come before capability, not as a barrier to progress but as a safeguard, ensuring each increase in cognitive power is matched by an equal or greater increase in ethical oversight.

6. From AI Safety to Reformative AI Architecture

Most current AI safety frameworks, such as alignment, interpretability, and robustness, mainly focus on reactive mitigation. Reforming AI requires a shift toward proactive and responsible design. Instead of patching models after they misbehave, we should design them with built-in cognitive and ethical boundaries that keep autonomy accountable and human-centered. This may involve:

Embedding behavioral entropy thresholds, which are mathematical limits beyond which the system cannot change its internal objectives, prevents uncontrolled goal drift.

Implementing bi-directional cognitive locks where a human and machine must co-approve critical reasoning expansions.

Developing containment protocols that isolate high-level reasoning processes from self-replication or cross-model diffusion.

In essence, reforming AI is the cognitive equivalent of cybersecurity, but instead of defending data, it defends humanity’s cognitive domain.

7. The Social Dimension

The rise of neurocognitive AI also challenges our societal systems. When human-like intelligence becomes artificial, identity and work become less clear. Reforming AI thus goes beyond technical design into philosophical and legal areas. Who is responsible when a self-improving model diverges? Who defines “harm” when an AI’s reasoning process is partly unclear even to its creators? The need for a global ethical framework is urgent. Without it, progress might outpace regulation, and innovation could weaken trust.

8. Conclusions

At its highest potential, artificial intelligence aims to replicate the mind. However, in doing so, we must ensure we do not imitate only its power but also its humility and self-restraint. Reforming AI is not a rejection of progress; it embodies a philosophy of responsible thinking. It calls for a new research approach in which an equally significant advance matches every advance in machine intelligence in meta-cognitive oversight. Just as we created firewalls to defend networks and immune systems to protect biology, we now need to develop cognitive firewalls, systems that ensure intelligence, regardless of how advanced, remains in service to humanity rather than in control of it. The question is not whether AI will become human-like. It is whether we will stay human enough to govern it.

References

- Golilarz, N.A.; et al. Towards Neurocognitive-Inspired Intelligence: From AI’s Structural Mimicry to Human-Like Functional Cognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.13826 2025.

- Bernstein, M.H.; et al. Can incorrect artificial intelligence (AI) results impact radiologists, and if so, what can we do about it? A multi-reader pilot study of lung cancer detection with chest radiography. European radiology 2023, 33, 8263–8269.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).