Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objective: High-risk Human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is the leading cause of premalignant lesions and cervical cancer (CC), affecting disproportionally women living with HIV. Mozambique is among the countries with a heavy triple-burden of HIV, hrHPV infections and CC which accounts for more than 5300 new cases and 3800 deaths each year. In this study, we assessed the age-specific distribution and factors associated with hrHPV and cervical lesions among HIV-positive and -negative women from HPV-ISI (HPV Innovative Screening Initiative) study in Maputo, Mozambique. Methods: This cross-sectional study included 1,248 non-pregnant women aged ≥18 years who attended CC screening at the DREAM Sant’Egídio Health Center between July 2021 and April 2022. Screening involved visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and high-risk HPV DNA testing. Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and reproductive data were collected through a routine questionnaire. Logistic regression assessed associations between risk factors and hrHPV infection or cervical lesions. Age-specific hrHPV prevalence, partial HPV16/18 genotyping, and abnormal cytology rates were further analyzed by HIV status. Results: The mean age was 43.0±8.6 years. The hrHPV prevalence was 28%, higher in HIV-positive (46.8%) than HIV-negative (23.8%) women. Non-16/18 hrHPV types predominated across all ages. VIA positivity was 11.1%, mostly involving <75% cervical area, and was more frequent in younger (30–45 years) and HIV-positive women. Older age (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–1.00, p=0.017) and higher parity (≥3 vs nulliparous: OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.36–0.94, p=0.029) showed protective effects against hrHPV infection. Contraceptive use (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.15–2.38, p=0.007) and partially/non-visible SCJ (OR 2.88, 95% CI 1.74–4.79, p<0.001) were associated with VIA positivity. Conclusions: hrHPV infection and cervical lesions were more frequent in younger and HIV-positive women, highlighting the need for strengthened targeted screening within HIV care services in Mozambique.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

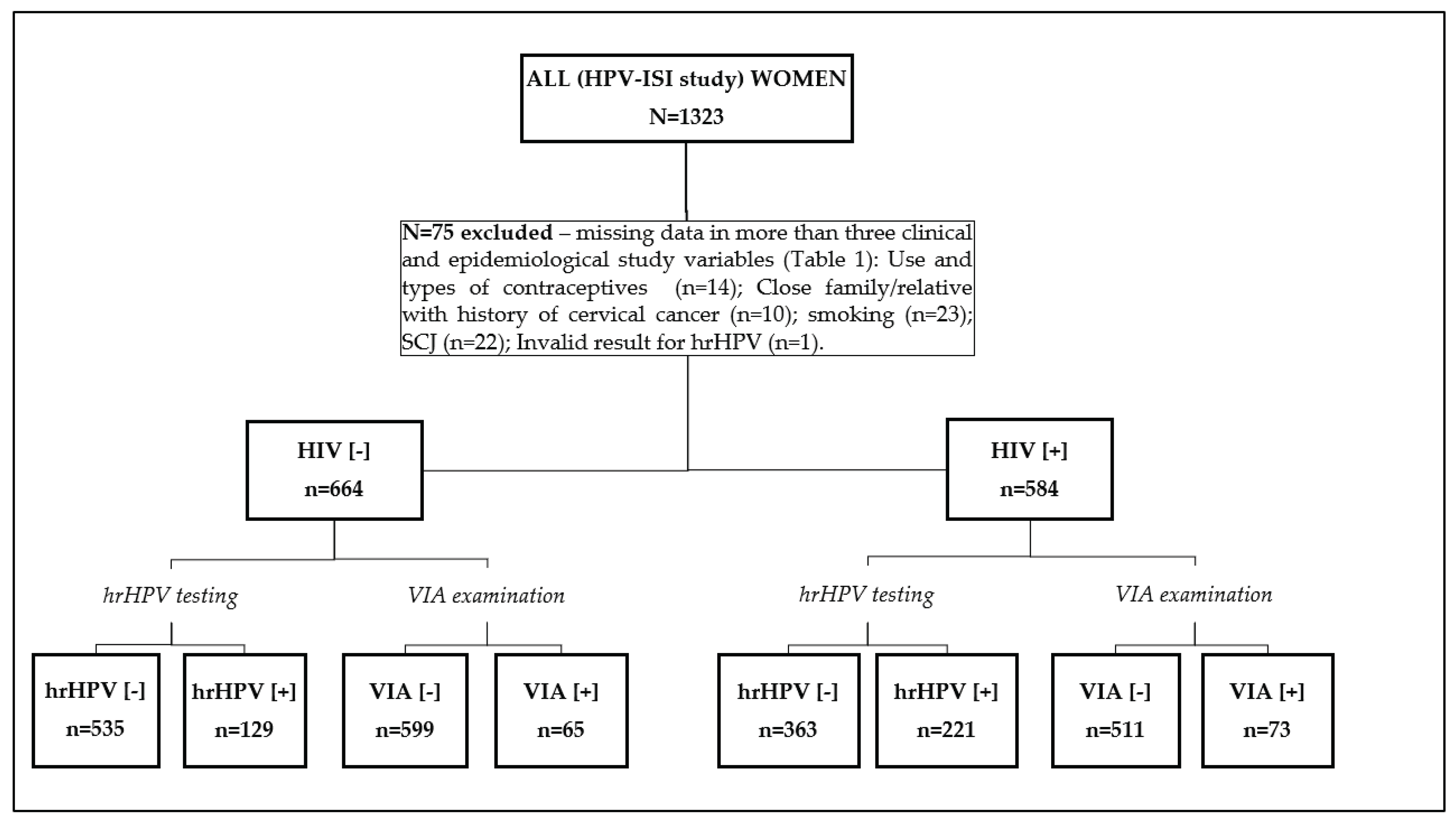

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Ethical Approval

2.2. Data Collection, Samples and Screening Tests

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Distribution of hrHPV and VIA Results by Participants Characteristics and According to HIV Status

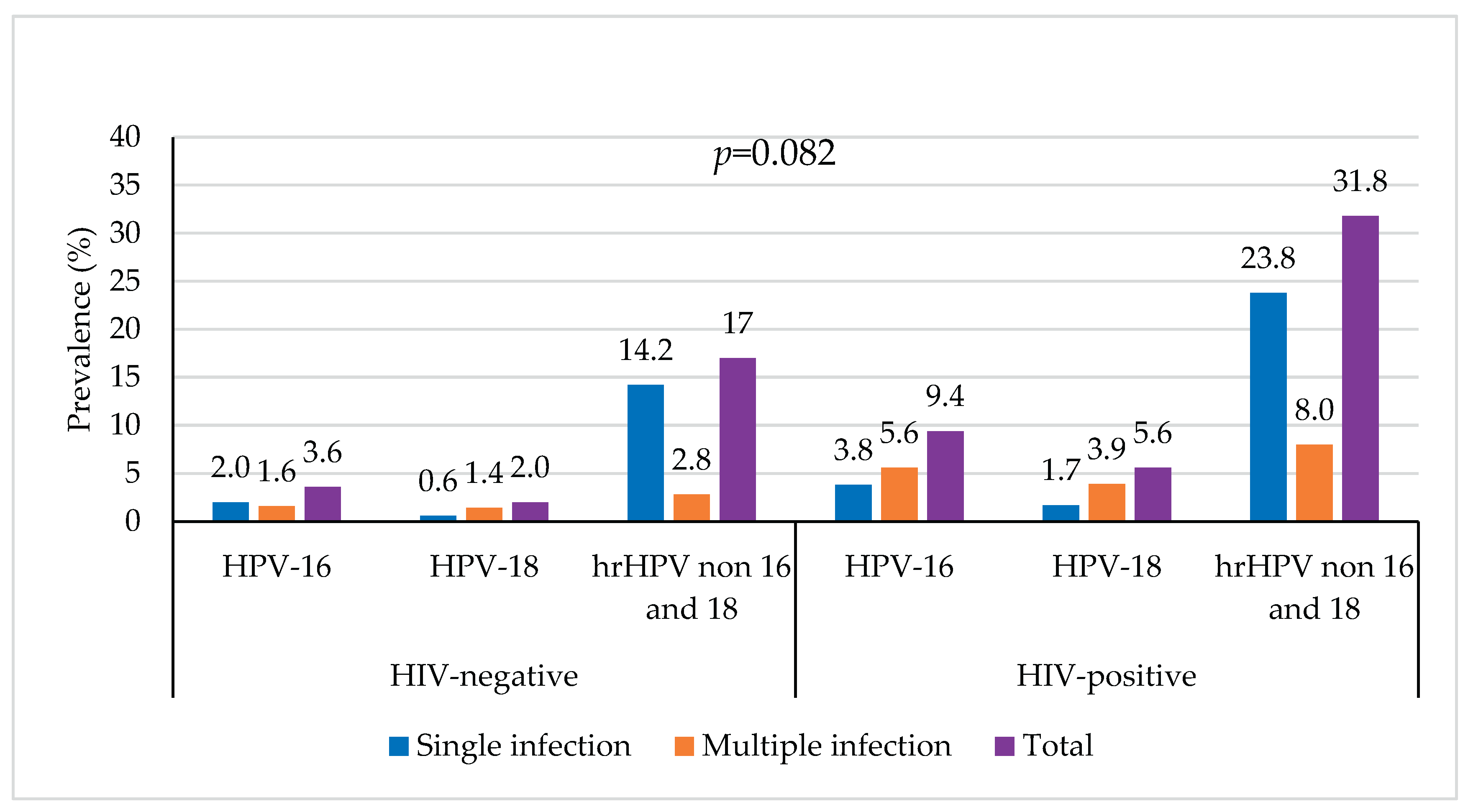

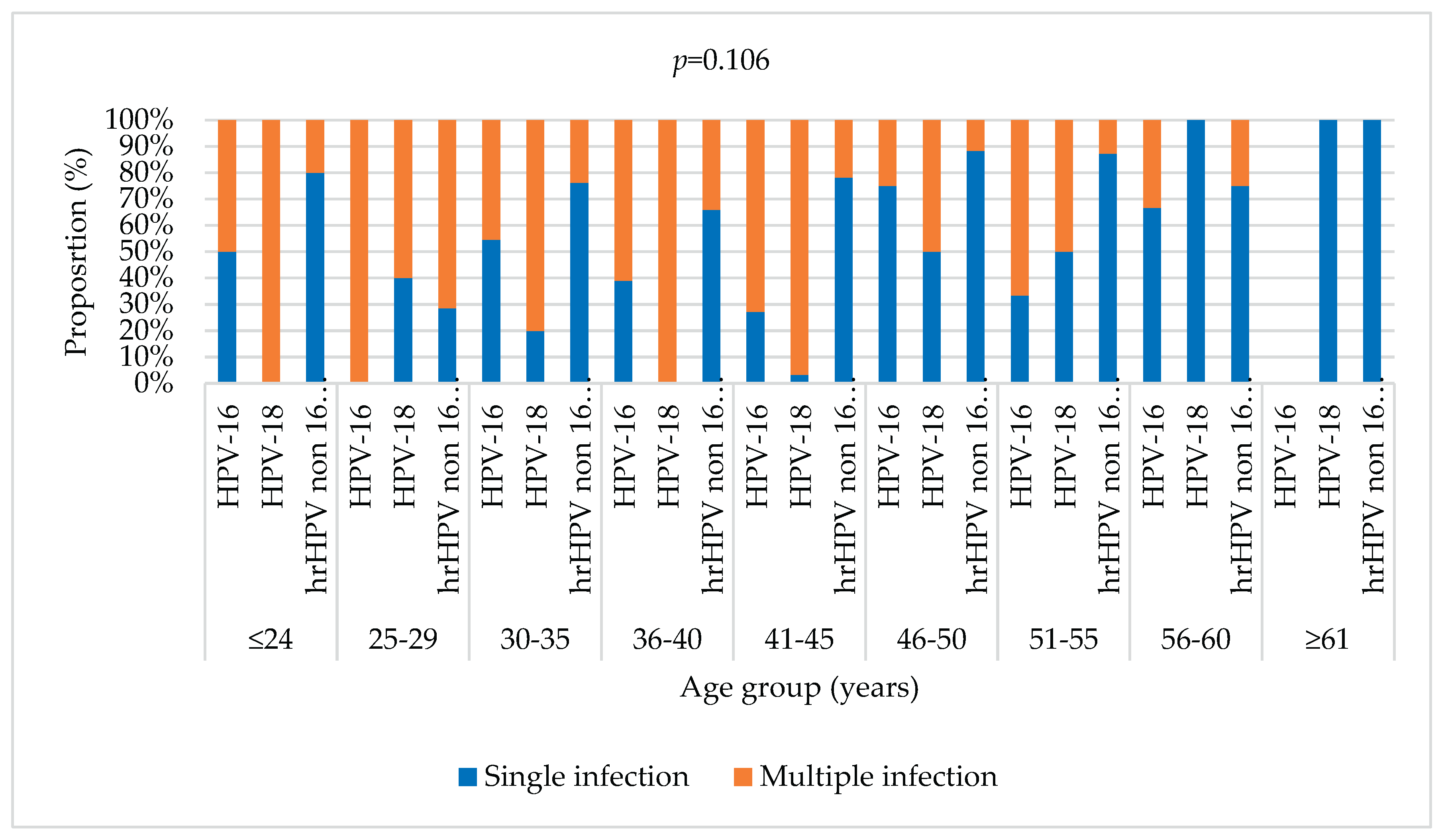

3.3. Overall Prevalence of hrHPV Types According to HIV Status and Its Age-Specific Distribution

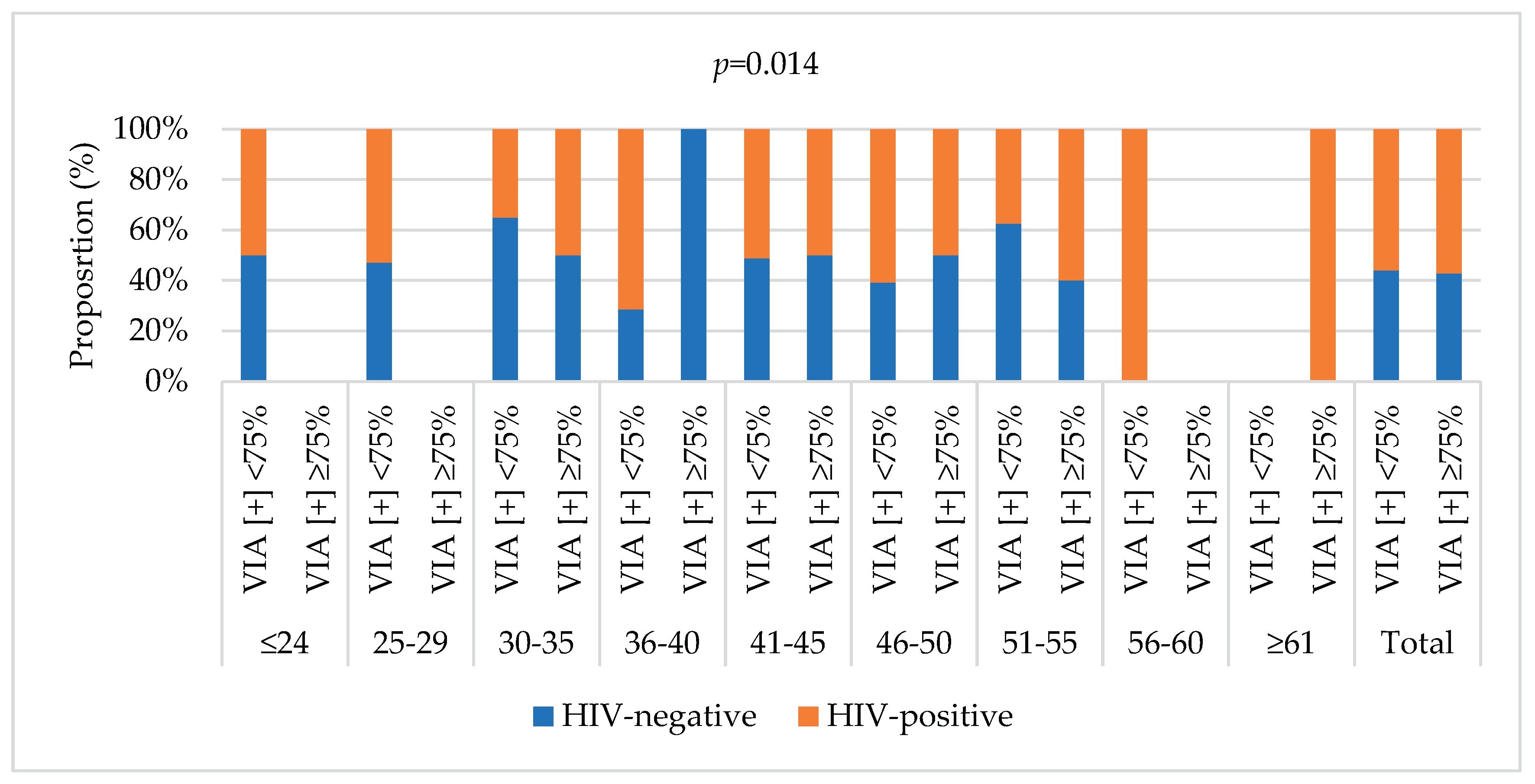

3.4. Overall Prevalence of Cervical Lesions According to HIV Status and Its Age-Specific Distribution

3.5. Factors Associated with hrHPV Prevalence and Cervical Lesions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruni, L.; Diaz, M.; Castellsagué, X.; Ferrer, E.; Bosch, F.X.; De Sanjosé, S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: Meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010, 202, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Collado, J.J.; Gómez, D.; et al. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in the World. Summary Report [Internet]. 2023 Mar. Available from: www.hpvcentre.net.

- Lekoane, B.K.M.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P.; Ginindza, T.G. Mapping evidence on the distribution of human papillomavirus-related cancers in sub-Saharan Africa: Scoping review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboumba Bouassa, R.S.; Prazuck, T.; Lethu, T.; Jenabian, M.A.; Meye, J.F.; Bélec, L. Cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a preventable noncommunicable disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2017, 15, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martel, C.; Plummer, M.; Vignat, J.; Franceschi, S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 2017, 141, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, H.W.; Dunne, E.F.; Hariri, S.; Markowitz, L.E. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014, 41, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudenga, S.L.; Shrestha, S. Key considerations and current perspectives of epidemiological studies on human papillomavirus persistence, the intermediate phenotype to cervical cancer. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2013, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walboomers, J.M.M.; Jacobs, M.V.; Manos, M.M.; Bosch, F.X.; Kummer, J.A.; Shah, K.V.; et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. Journal of Pathology. 1999, 189, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, N.; Bosch, F.X.; de Sanjosé, S.; Herrero, R.; Castellsagué, X.; Shah, K.V.; et al. Epidemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with Cervical Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003, 348, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Tommasino, M.; Depuydt, C.; Dillner, J. Are 20 human papillomavirus types causing cervical cancer? J Pathol. 2014, 234, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzle, D.; Tanaka, L.F.; Lee, K.K.; Ibrahim Khalil, A.; Baussano, I.; Shah, A.S.V.; et al. Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health. 2021, 9, e161–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoye, J.O.; Ofodile, C.A.; Adeleke, O.K.; Obioma, O. Prevalence of high-risk HPV genotypes in sub-Saharan Africa according to HIV status: a 20-year systematic review. Epidemiol Health [Internet]. 2021, 43, e2021039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchouaket, M.C.T.; Ka’e, A.C.; Semengue, E.N.J.; Sosso, S.M.; Simo, R.K.; Yagai, B.; et al. Variability of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus and Associated Factors among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellsagué, X. Natural history and epidemiology of HPV infection and cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008, 110, S4–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panatto, D.; Amicizia, D.; Trucchi, C.; Casabona, F.; Lai, P.L.; Bonanni, P.; et al. Sexual behaviour and risk factors for the acquisition of human papillomavirus infections in young people in Italy: suggestions for future vaccination policies [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/623.

- Schiffman, M.; Wentzensen, N. Human Papillomavirus Infection and the Multistage Carcinogenesis of Cervical Cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention [Internet]. 2013, 22, 553–560, Available from: https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/22/4/553/69839/Human-Papillomavirus-Infectionand-the-Multistage. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Park, E.C.; Chang, H.S.; Kwon, J.A.; Yoo, K.B.; Kim, T.H. Socioeconomic disparity in cervical cancer screening among Korean women: 1998-2010. BMC Public Health 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broberg, G.; Wang, J.; Östberg, A.L.; Adolfsson, A.; Nemes, S.; Sparén, P.; et al. Socio-economic and demographic determinants affecting participation in the Swedish cervical screening program: A population-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinyemiju, T.; Ogunsina, K.; Sakhuja, S.; Ogbhodo, V.; Braithwaite, D. Life-course socioeconomic status and breast and cervical cancer screening: Analysis of the WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). BMJ Open. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Collado, J.J.; Gómez, D.; et al. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Mozambique. Summary Report [Internet]. 2023 Mar. Available from: www.hpvcentre.net.

- Edna Omar, V.; Orvalho, A.; Nália, I.; Kaliff, M.; Lillsunde-Larsson, G.; Ramqvist, T.; et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and genotype distribution among young women and men in Maputo city, Mozambique. BMJ Open. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bule, Y.P.; Silva, J.; Carrilho, C.; Campos, C.; Sousa, H.; Tavares, A.; et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and distribution in self-collected samples from female university students in Maputo. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2020, 149, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maueia, C.; Murahwa, A.; Manjate, A.; Andersson, S.; Sacarlal, J.; Kenga, D.; et al. Identification of the human papillomavirus genotypes, according to the human immunodeficiency virus status in a cohort of women from maputo, Mozambique. Viruses. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, M.P.; Oliveira, C.; Andrade, V.; Mariano, A.A.N.; Changule, D.; Rangeiro, R.; et al. The Capulana study: A prospective evaluation of cervical cancer screening using human papillomavirus testing in Mozambique. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2020, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcedo, M.P.; Lathrop, E.; Osman, N.; Neves, A.; Rangeiro, R.; Mariano, A.A.N.; et al. The Mulher Study: cervical cancer screening with primary HPV testing in Mozambique. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2023, 33, 1869–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sineque, A.; Catalao, C.; Ceffa, S.; Fonseca, A.M.; Parruque, F.; Guidotti, G.; et al. Screening approaches for cervical cancer in Mozambique in HIV positive and negative women. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, C.; Fontes, F.; Tulsidás, S.; Lorenzoni, C.; Ferro, J.; Brandão, M.; et al. Cancer incidence in Mozambique in 2015–2016: data from the Maputo Central Hospital Cancer Registry. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2019, 28, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batman, S.; Rangeiro, R.; Monteiro, E.; Changule, D.; Daud, S.; Ribeiro, M.; et al. Expanding Cervical Cancer Screening in Mozambique: Challenges Associated With Diagnosing and Treating Cervical Cancer. JCO Glob Oncol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naucler, P.; Mabota da Costa, F.; da Costa, J.L.; Ljungberg, O.; Bugalho, A.; Dillner, J. Human papillomavirus type-specific risk of cervical cancer in a population with high human immunodeficiency virus prevalence: case–control study. Journal of General Virology. 2011, 92, 2784–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothe, M.A.S.; Sathane, I.; Baltazar, C.S.; Chicuecue, N.; Horth, R.; Fazito, E.; et al. Low engagement in HIV services and progress through the treatment cascade among key populations living with HIV in Mozambique: alarming gaps in knowledge of status. BMC Public Health. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INS - Instituto Nacional de Saúde. Inquérito Nacional sobre o Impacto do HIV e SIDA (INSIDA 2021): Relatório Final. [Internet]. Maputo; 2023 Jul. Available from: http://ins.gov.mz.

- Brandão, M.; Tulsidás, S.; Damasceno, A.; Silva-Matos, C.; Carrilho, C.; Lunet, N. Cervical cancer screening uptake in women aged between 15 and 64 years in Mozambique. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2019, 28, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. Second. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. 1–115 p.

- Golia D’Augè, T.; Giannini, A.; Bogani, G.; Di Dio, C.; Laganà, A.S.; Di Donato, V.; et al. Prevention, Screening, Treatment and Follow-Up of Gynecological Cancers: State of Art and Future Perspectives. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2023, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Botha, M. Cervical cancer prevention in Southern Africa: A review of national cervical cancer screening guidelines in the Southern African development community. J Cancer Policy. 2024, 40, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, D.; Bay, Z.; Wate, A.; Nhanguiombe, H.; Manhica, P.; Bila, E.; et al. Scaling-up Cervical Cancer Services for Women Living with HIV in Mozambique, October 2018–September 2023 [Internet]. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sant’Egidio Community. Drug Resource Enhancement against AIDS and Malnutrition - DREAM: Report [Internet]. Rome; 2011 [cited 2025 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.santegidiomadrid.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/201103_ReportEN_.pdf.

- DREAM program. The Disease Relief through Excellent and Advanced Means (DREAM) program in sub-Saharan Africa. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.dream-health.org/?lang=en.

- Leone, M.; Palombi, L.; Guidotti, G.; Ciccacci, F.; Lunghi, R.; Orlando, S.; et al. What headache services in sub-Saharan Africa? The DREAM program as possible model. Cephalalgia. 2019, 39, 1339–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Lio, M.M.S.; Marchetti, I.; Carrilho, C.; Cioni, M.P.; Guidotti, G.; Moscatelli, C.; et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Mozambique. Retrovirology 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sineque, A.; Ceffa, S.; Parruque, F.; Guidotti, G.; Massango, C.; Sidumo, Z.; et al. Impact of STIs on cervical cancer screening: Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) positive women in Mozambique. Int J STD AIDS. 2024, 35, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MISAU. Plano Nacional de Controlo do Cancro 2019-2029. Maputo; 2019.

- Cunha, M.; Matos, C.S. MISAU. Normas Nacionais para Prevenção do Cancro do Colo Uterino [Internet]. Maputo; Available from: www.misau.gov.mz.

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globocan. The Global Cancer Observatory: fact sheet - Mozambique [Internet]. 2024 Feb [cited 2025 Oct 4]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/508-mozambique-fact-sheet.pdf.

- IARC - The International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cervical Cancer Screening Programme in Five Continents (CanScreen5): Country fact sheets [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 4]. Available from: https://canscreen5.iarc.fr/?page=countryfactsheetcervix&q=MOZ&rc=.

- Tulsidás, S.; Fontes, F.; Brandão, M.; Lunet, N.; Carrilho, C. Oncology in Mozambique: Overview of the Diagnostic, Treatment, and Research Capacity. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña-Rodríguez, P.; Bahena-Román, M.; Delgado-Romero, K.; Madrid-Marina, V.; Torres-Poveda, K. Prevalence and Risk Factors for High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Disorders: Baseline Findings From an Human Papillomavirus Cohort Study. Cancer Control. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, D.; Putoto, G.; Chhaganlal, K.D. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: a Mozambique overview. Vol. 27, VirusDisease. Springer India; 2016. p. 116–22.

- Okunade, K.S.; Nwogu, C.M.; Oluwole, A.A.; Anorlu, R.I. Prevalence and risk factors for genital high-risk human papillomavirus infection among women attending the outpatient clinics of a university teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2017, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinayobye, J.D.A.; Sklar, M.; Hoover, D.R.; Shi, Q.; Dusingize, J.C.; Cohen, M.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for High-Risk Human Papillomavirus (hrHPV) infection among HIV-infected and Uninfected Rwandan women: Implications for hrHPV-based screening in Rwanda. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabre, P.; Sagna, T.; Ouedraogo, R.; Simpore, J. Epidemiological profile of human papillomavirus infections and cervical cancer prevention among sexually active women in Burkina Faso: Literature Review. Med Res Arch. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.A.; Risley, C.; Stewart, M.W.; Geisinger, K.R.; Hiser, L.M.; Morgan, J.C.; et al. Age-specific prevalence of human papillomavirus and abnormal cytology at baseline in a diverse statewide prospective cohort of individuals undergoing cervical cancer screening in Mississippi. Cancer Med [Internet]. 2021, 10, 8641–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, V.; Hörner, L.; Nkurunziza, T.; Rank, S.; Tanaka, L.F.; Klug, S.J. Global prevalence of cervical human papillomavirus in women aged 50 years and older with normal cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2025, 6, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaji, S.; Aminu, M.; Inabo, H.; Oguntayo, A. Spectrum of high risk human papillomavirus types in women in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2019, 18, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangethe, J.M.; Gichuhi, S.; Odari, E.; Pintye, J.; Mutai, K.; Abdullahi, L.; et al. Confronting the human papillomavirus–HIV intersection: Cervical cytology implications for Kenyan women living with HIV. South Afr J HIV Med. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufa, T.; Mandiriri, A.; Shamu, T.; Dube Mandishora, R.S.; Pascoe, M.J. Prevalence of cervical high-risk human papillomavirus among Zimbabwean women living with HIV. South Afr J HIV Med. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.M.; Rangeiro, R.; Osman, N.; Baker, E.; Neves, A.; Mariano, A.A.N.; et al. Evaluation of hpv risk groups among women enrolled in the mulher cervical cancer screening study in Mozambique. Infect Agent Cancer. 2025, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Selabe, S.G.; Bogers, J.; Lebelo, R.L. High prevalence of and factors associated with human papillomavirus infection among women attending a tertiary hospital in Gauteng Province, South Africa. BMC Cancer. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim Khalil, A.; Mpunga, T.; Wei, F.; Baussano, I.; de Martel, C.; Bray, F.; et al. Age-specific burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV: A global analysis with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Cancer. 2022, 150, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues De Oliveira 1 Valdimara Corrêa Vieira G, Fernanda Martínez Barral M. Risk factors and prevalence of HPV infection in patients from Basic Health Units of an University Hospital in southern Brazil Palavras-chave.

- Tekalegn, Y.; Aman, R.; Woldeyohannes, D.; Sahiledengle, B.; Degno, S. Determinants of VIA Positivity Among Women Screened for Cervical Precancerous Lesion in Public Hospitals of Oromia Region, Ethiopia: Unmatched Case-Control Study. Int J Womens Health. 2020, 12, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, V.B.; Wright, J.D.; Gross, C.P.; Lin, H.; Boscoe, F.P.; Hutchison, L.M.; et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors of occult uterine cancer in presumed benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019, 221, 39.e1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maueia, C.; Murahwa, A.; Manjate, A.; Sacarlal, J.; Kenga, D.; Unemo, M.; et al. The relationship between selected sexually transmitted pathogens, HPV and HIV infection status in women presenting with gynaecological symptoms in Maputo City, Mozambique. PLoS One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Piao, H. Status and epidemiological characteristics of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in multiple centers in Shenyang. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Factors | Sociodemographic | Healthcare referral facility; Age (years; ≤29, 30-45, ≥46; ≤24, 25-29, 30-35, 36-40, 41-45, 46-50, 51-55, 56-60, ≥61). |

| Sexual and lifestyle behavior | Age at first intercourse - sexual debut [years; ≤17 (adolescent), 18-25 (young), ≥26 (adult)]; Use of contraceptives [no/yes (condom use, oral pills, intrauterine device, implant, injectable, other); smoking habit (no/yes). | |

| Clinical, gynecological and reproductive history | HIV status (negative/positive); Screening or consultations history (1st/Follow-up 1 year/ Follow-up 3 year); Pregnancies history (number; nulligravida, 1-2, ≥3); Full-term pregnancies or deliveries history (number; nulliparous, 1-2, ≥3); History of STI or vaginal descharge (yes/no); Close family/relative with history of cervical cancer (yes/no); Gynecological findings [vaginal/uterus related (normal/abdnormal - cervicitis, bleeding, condylomas, polyps, others); SCJ related (Totally visible/Partially or not visible)]. | |

| Main outcomes | Clinical-laboratory | VIA result [negative/positive (<75%; ≥75% or worse)]; hrHPV result [negative/positive (HPV-16, HPV-18 and Other hrHPV) |

| Characteristic varables | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Health center of provenance | - | |

| DREAM Sant’Egidio | 1052 | 84.3 |

| DREAM Consolata/Criança | 46 | 3.7 |

| DREAM Machava | 136 | 10.9 |

| DREAM Matola-II | 11 | 0.9 |

| Other – external to DREAM | 3 | 0,2 |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 43.0±8.6 | – |

| Age category (years) | ||

| ≤29 | 56 | 4.5 |

| 30-45 | 700 | 56.1 |

| ≥46 | 492 | 39.4 |

| Screening type* | ||

| First time | 924 | 74 |

| 1 year follow-up | 272 | 21.8 |

| 3 year follow-up | 52 | 4.2 |

| Age at sexual debut (years), mean±SD | 17.5±2.4 | – |

| Age at sexual debut (years) | ||

| ≤17 (adolescent) | 666 | 53.4 |

| 18-25 (young) | 577 | 46.2 |

| ≥26 (adult) | 5 | 0.4 |

| Number of pregnancy, mean±SD | 4.1±2.1 | – |

| Number of pregnancy | ||

| Nulligravida | 52 | 4.2 |

| 1-2 | 233 | 18.7 |

| ≥3 | 963 | 77.1 |

| Number of deliveries, mean±SD | 3.2±1.9 | – |

| Number of deliveries | ||

| Nulliparous | 77 | 6.2 |

| 1-2 | 379 | 30.4 |

| ≥3 | 792 | 63.4 |

| Menstrual cycle, n (%) | ||

| Normal (regular) | 838 | 67.1 |

| Abdnormal (irregular) | 410 | 32.9 |

| Use of contraceptives | ||

| No | 875 | 70.1 |

| Yes** | 373 | 29.9 |

| Condom | 31 | 2.5 |

| Oral pills | 117 | 9.4 |

| IUD | 28 | 2.2 |

| Implant | 84 | 6.7 |

| Injectable | 76 | 6.1 |

| Other type | 16 | 1.3 |

| Not declared | 21 | 1.7 |

| Family history of CC | ||

| No | 1207 | 96.7 |

| Yes | 15 | 1.2 |

| Don’t know | 26 | 2.1 |

| Smoking (or ever smoked) | ||

| No | 1164 | 93.3 |

| Yes | 1 | 0.1 |

| Not declared | 83 | 6.6 |

| Previous STI/Vaginal discharge | ||

| No | 1149 | 92.1 |

| Yes | 99 | 7.9 |

| Gynecological findings – vaginal/uterus | ||

| Normal | 1147 | 91.9 |

| Abdormal*** | 101 | 8.1 |

| Gynecological findings – SCJ | ||

| Totally visible | 1153 | 92.4 |

| Partially/Not visible | 95 | 7.6 |

| VIA result | ||

| Negative | 1110 | 88.9 |

| Positive | 138 | 11.1 |

| <75% | 125 | 10.1 |

| ≥75% | 13 | 1.0 |

| hrHPV result | ||

| Negative | 898 | 72.0 |

| Positive | 350 | 28.0 |

| Varables | All | HIV-positive (+) | HIV-negative (-) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hrHPV (+) | hrHPV (-) | P value | hrHPV (+) | hrHPV (-) | P value | hrHPV (+) | hrHPV (-) | P value | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 42.0±8.9 | 43.3±8.0 | 0.013a | 43.3±8.1 | 42.9±7.4 | 0.540 | 39.9±9.9 | 43.6±9.1 | <0.001a |

| Age category (years), n (%) | |||||||||

| ≤29 | 21 (1.7) | 35 (2.8) | 5 (0.9) | 7 (1.2) | 16 (2.4) | 28 (4.2) | |||

| 30-45 | 206 (16.5) | 494 (39.6) | 0.067 | 132 (22.6) | 228 (39.0) | 0.751 | 74 (11.1) | 266 (40.1) | <0.001a |

| ≥46 | 123 (9.9) | 369 (29.6) | 84 (14.4) | 128 (21.9) | 39 (5.9) | 241 (36.3) | |||

| Screening type*, n (%) | |||||||||

| First time | 259 (20.8) | 665 (53.3) | 0.038a | 151 (25.9) | 229 (39.2) | 0.339 | 108 (16.3) | 436 (65.7) | 0.561 |

| 1 year follow-up | 84 (6.7) | 188 (15.1) | 70 (12.0) | 133 (22.8) | 14 (2.1) | 55 (8.3) | |||

| 3 year follow-up | 7 (0.6) | 45 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.1) | 44 (6.6) | |||

| Age at sexual debut (years), mean±SD | 17.5±2.7 | 17.6±2.3 | 0.512 | 17.3±2.7 | 17.4±2.2 | 0.626 | 17.7±2.7 | 17.7±2.4 | 1.00 |

| Age at sexual debut (years), n (%) | |||||||||

| ≤17 (adolescent) | 197 (15.8) | 469 (37.6) | 128 (21.9) | 202 (34.6) | 69 (10.4) | 267 (40.2) | |||

| 18-25 (young) | 150 (12.0) | 427 (34.2) | 0.105 | 91 (15.6) | 160 (27.4) | 0.483 | 59 (8.9) | 267 (40.2) | 0.401 |

| ≥26 (adult) | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Number of pregnancy, mean±SD | 4.0±2.2 | 4.1±2.1 | 0.456 | 3.9±2.0 | 4.0±2.0 | 0.558 | 4.2±2.5 | 4.2±2.1 | 1.00 |

| Number of pregnancy, n (%) | |||||||||

| Nulligravida | 23 (1.8) | 29 (2.2) | 0.038a | 10 (1.7) | 10 (1.7) | 0.524 | 12 (1.8) | 18 (2.7) | 0.013a |

| 1-2 | 65 (5.2) | 168 (13.5) | 47 (8.1) | 80 (13.7) | 18 (2.7) | 88 (13.3) | |||

| ≥3 | 263 (21.1) | 700 (56.2) | 164 (28.2) | 271 (46.6) | 99 (14.9) | 429 (64.6) | |||

| Number of deliveries, mean±SD | 3.2±2.0 | 3.3±1.8 | 0.393 | 3.1±1.9 | 3.1±1.7 | 1.00 | 3.3±2.2 | 3.4±1.8 | 0.589 |

| Number of deliveries, n (%) | |||||||||

| Nulliparous | 29 (2.3) | 48 (3.8) | 15 (2.6) | 24 (4.1) | 14 (2.1) | 24 (3.6) | |||

| 1-2 | 115 (9.2) | 264 (21.2) | 0.046a | 78 (13.4) | 115 (19.7) | 0.645 | 37 (5.6) | 149 (22.4) | 0.017a |

| ≥3 | 206 (16.5) | 586 (47.0) | 128 (21.9) | 224 (38.4) | 78 (11.7) | 362 (54.5) | |||

| Menstrual cycle, n (%) | |||||||||

| Normal (regular) | 239 (19.2) | 599 (48.0) | 0.639 | 152 (26.0) | 256 (43.8) | 0.710 | 87 (13.1) | 343 (51.7) | 0.538 |

| Abdnormal (irregular) | 111 (8.9) | 299 (24.0) | 69 (11.8) | 107 (18.3) | 42 (6.3) | 192 (28.9) | |||

| Use of contraceptives, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 244 (19.5) | 631 (50.6) | 0.891 | 165 (28.3) | 259 (44.3) | 0.339 | 79 (11.9) | 372 (56.1) | 0.075 |

| Yes** | 106 (8.5) | 267 (21.4) | 56 (9.6) | 104 (17.8) | 50 (7.5) | 163 (24.5) | |||

| Condom | 11 (0.9) | 20 (1.6) | 8 (1.4) | 11 (1.9) | 3 (0.5) | 9 (1.4) | |||

| Oral pills | 32 (2.6) | 85 (6.8) | 12 (2.1) | 27 (4.6) | 20 (3.0) | 58 (8.7) | |||

| IUD | 5 (0.4) | 23 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (1.5) | 4 (0.6) | 14 (2.1) | |||

| Implant | 26 (2.1) | 58 (4.6) | 19 (2.9) | 19 (3.3) | 9 (1.4) | 39 (5.9) | |||

| Injectable | 23 (1.8) | 53 (4.2) | 10 (1.7) | 26 (4.5) | 13 (2.0) | 27 (4.1) | |||

| Other type | 4 (0.3) | 12 (1.0) | 4 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.9) | |||

| Not declared | 5 (0.4) | 16 (1.3) | 4 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 10 (1.5) | |||

| Family history of CC, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 337 (27.0) | 870 (69.7) | 0.389 | 212 (36.3) | 347 (59.4) | 0.698 | 125 (18.8) | 523 (78.8) | 0.687 |

| Yes | 3 (0.2) | 12 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (1.2) | |||

| Don’t know | 10 (0.8) | 16 (1.3) | 8 (1.4) | 12 (2.1) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) | |||

| Smoking (or ever smoked), n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 326 (26.1) | 838 (67.1) | 0.276 | 203 (34.8) | 333 (57.0) | 0.428 | 123 (18.5) | 505 (76.1) | 0.829 |

| Yes | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Not declared | 23 (1.8) | 60 (4.8) | 17 (2.9) | 30 (5.1) | 6 (0.9) | 30 (4.5) | |||

| Previous STI/Vaginal discharge, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 318 (25.5) | 831 (66.6) | 0.351 | 199 (34.1) | 331 (56.7) | 0.660 | 119 (17.9) | 500 (75.3) | 0.696 |

| Yes | 32 (2.6) | 67 (5.4) | 22 (3.8) | 32 (5.5) | 10 (1.5) | 35 (5.3) | |||

| Gynecological findings – vaginal/uterus, n (%) | |||||||||

| Normal | 311 (24.9) | 836 (67.0) | 0.020a | 195 (33.4) | 330 (56.5) | 0.323 | 116 (17.5) | 506 (76.1) | 0.067 |

| Abdormal*** | 39 (3.1) | 62 (5.0) | 26 (4.5) | 33 (5.7) | 13 (2.0) | 29 (4.4) | |||

| Gynecological findings – SCJ, n (%) | |||||||||

| Totally visible | 320 (25.6) | 833 (66.7) | 0.409 | 201 (34.4) | 341 (58.4) | 0.189 | 119 (17.9) | 492 (74.1) | 1.00 |

| Partially/Not visible | 30 (2.4) | 65 (5.3) | 20 (3.4) | 22 (3.8) | 10 (1.5) | 43 (6.5) | |||

| Varables | All | HIV-positive (+) | HIV-negative (-) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIA (+) | VIA (-) | P value | VIA (+) | VIA (-) | P value | VIA (+) | VIA (-) | P value | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 38.9±7.9 | 43.5±8.5 | <0.001a | 39.6±8.1 | 43.6±7.5 | <0.001a | 38.1±7.8 | 43.4±9.3 | <0.001a |

| Age category (years), n (%) | |||||||||

| ≤29 | 14 (1.1) | 42 (3.4) | 7 (1.2) | 5 (0.9) | 7 (1.1) | 37 (5.6) | |||

| 30-45 | 95 (7.6) | 605 (48.5) | <0.001a | 49 (8.4) | 311 (53.3) | <0.001a | 46 (6.9) | 294 (44.3) | <0.001a |

| ≥46 | 29 (2.3) | 463 (37.1) | 17 (2.9) | 195 (33.4) | 12 (1.8) | 268 (40.4) | |||

| Screening type, n (%) | |||||||||

| First time | 112 (9.0) | 812 (65.1) | 0.075 | 54 (9.4) | 326 (55.8) | 0.224 | 58 (8.7) | 486 (73.2) | 0.227 |

| 1 year follow-up | 24 (1.9) | 248 (19.9) | 19 (3.3) | 184 (31.5) | 5 (0.9) | 64 (9.6) | |||

| 3 year follow-up | 2 (0.2) | 50 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 49 (7.4) | |||

| Age at sexual debut (years), mean±SD | 17.3±2.7 | 17.6±2.4 | 0.213 | 17.2±1.6 | 17.4±2.5 | 0.507 | 17.3±3.5 | 17.7±2.3 | 0.210 |

| Age at sexual debut (years), n (%) | |||||||||

| ≤17 (adolescent) | 81 (6.5) | 585 (46.9) | 40 (6.8) | 290 (49.7) | 41 (6.2) | 295 (44.4) | |||

| 18-25 (young) | 56 (4.5) | 521 (41.7) | 0.316 | 33 (5.7) | 218 (37.3) | 0.753 | 23 (3.5) | 303 (45.6) | 0.013a |

| ≥26 (adult) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Number of pregnancy, mean±SD | 3.8±1.8 | 4.1±2.1 | 0.070 | 3.7±1.7 | 4.0±2.0 | 0.223 | 4.0±2.0 | 4.2±2.2 | 0.483 |

| Number of pregnancy, n (%) | |||||||||

| Nulligravida | 4 (0.3) | 46 (3.7) | 0.778 | 2 (0.3) | 18 (3.1) | 0.902 | 2 (0.3) | 28 (4.2) | 0.723 |

| 1-2 | 26 (2.1) | 207 (16.6) | 17 (2.9) | 110 (18.9) | 9 (1.4) | 97 (14.2) | |||

| ≥3 | 108 (8.7) | 855 (68.6) | 54 (9.3) | 381 (65.5) | 54 (8.1) | 474 (71.4) | |||

| Number of deliveries, mean±SD | 3.0±1.7 | 3.3±1.8 | 0.052 | 2.9±1.7 | 3.1±1.8 | 0.372 | 3.1±1.7 | 3.4±1.9 | 0.223 |

| Number of deliveries, n (%) | |||||||||

| Nulliparous | 8 (0.6) | 69 (5.5) | 4 (0.7) | 35 (6.0) | 4 (0.6) | 34 (5.1) | |||

| 1-2 | 55 (4.4) | 324 (26.0) | 0.036a | 33 (5.7) | 160 (27.4) | 0.062 | 22 (3.3) | 164 (24.7) | 0.515 |

| ≥3 | 75 (6.0) | 717 (57.5) | 36 (6.2) | 316 (54.1) | 39 (5.9) | 401 (60.4) | |||

| Menstrual cycle, n (%) | |||||||||

| Normal (regular) | 89 (7.1) | 749 (60.0) | 0.502 | 52 (8.9) | 356 (61.0) | 0.892 | 37 (5.6) | 393 (59.2) | 0.173 |

| Abdnormal (irregular) | 49 (3.9) | 361 (28.9) | 21 (3.6) | 155 (26.5) | 28 (4.2) | 206 (31.0) | |||

| Use of contraceptives, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 83 (6.7) | 792 (63.4) | 0.008a | 49 (8.4) | 375 (64.2) | 0.264 | 34 (5.1) | 417 (62.8) | 0.007a |

| Yes* | 55 (4.4) | 318 (25.5) | 24 (4.1) | 136 (23.3) | 31 (4.7) | 182 (27.4) | |||

| Condom | 2 (0.2) | 29 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (3.3) | 2 (0.3) | 10 (1.5) | |||

| Oral pills | 18 (1.4) | 99 (7.9) | 6 (1.0) | 33 (5.7) | 12 (1.8) | 66 (9.9) | |||

| IUD | 5 (0.4) | 23 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (1.5) | 4 (0.6) | 14 (2.1) | |||

| Implant | 14 (1.1) | 70 (5.6) | 5 (0.9) | 31 (5.3) | 9 (1.4) | 39 (5.9) | |||

| Injectable | 11 (0.9) | 65 (5.2) | 7 (1.2) | 29 (5.0) | 4 (0.6) | 36 (5.4) | |||

| Other type | 2 (0.2) | 14 (1.1) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.9) | |||

| Not declared | 3 (0.2) | 18 (1.4) | 3 (0.5) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.7) | |||

| Family history of CC, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 134 (10.7) | 1073 (86.0) | 0.307 | 70 (12.0) | 489 (83.7) | 0.661 | 64 (9.6) | 584 (88.0) | 0.494 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (1.5) | |||

| Don’t know | 4 (0.3) | 22 (1.8) | 3 (0.5) | 17 (2.9) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.8) | |||

| Smoking (or ever smoked), n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 129 (10.3) | 1035 (82.9) | 0.216 | 68 (11.6) | 468 (80.1) | 0.857 | 61 (9.2) | 567 (85.4) | 0.772 |

| Yes | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Not declared | 9 (0.7) | 74 (5.9) | 5 (0.9) | 42 (7.2) | 4 (0.6) | 32 (4.8) | |||

| Previous STI/Vaginal discharge, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 124 (9.9) | 1025 (82.1) | 0.190 | 66 (11.3) | 464 (79.5) | 0.831 | 58 (8.7) | 561 (84.5) | 0.315 |

| Yes | 14 (1.1) | 85 (6.4) | 7 (1.2) | 47 (8.0) | 7 (1.1) | 38 (5.7) | |||

| Gynecological findings – vaginal/uterus, n (%) | |||||||||

| Normal | 123 (9.9) | 1024 (82.0) | 0.244 | 64 (11.0) | 461 (78.9) | 0.532 | 59 (8.9) | 563 (84.8) | 0.287 |

| Abdormal** | 15 (1.2) | 86 (6.9) | 9 (1.5) | 50 (8.6) | 6 (0.9) | 36 (5.4) | |||

| Gynecological findings – SCJ, n (%) | |||||||||

| Totally visible | 115 (9.2) | 1038 (83.2) | <0.001a | 58 (9.9) | 484 (82.9) | <0.001a | 57 (8.6) | 554 (83.4) | 0.223 |

| Partially/Not visible | 13 (1.8) | 72 (5.8) | 15 (2.6) | 27 (4.6) | 8 (1.2) | 45 (6.8) | |||

| Predictor variables | All | HIV-positive (+) | HIV-negative (-) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.98 (0.97 – 1.00) | 0.017 | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.03) | 0.662 | 0.96 (0.94 – 0.98) | <0.001 |

| Age category (years) | ||||||

| ≤29 | Reference | |||||

| 30-45 | 0.70 (0.40 – 1.22) | 0.207 | 0.81 (0.25 – 2.60) | 0.724 | 0.49 (0.25 – 0.95) | 0.034 |

| ≥46 | 0.56 (0.31 – 0.99) | 0.046 | 0.92 (0.22 – 2.25) | 0.888 | 0.28 (0.14 – 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Screening type | ||||||

| First time | Reference | |||||

| 1 year follow-up | 1.15 (0.85 – 1.54) | 0.361 | 0.80 (0.56 – 1.14) | 0.213 | 1.03 (0.55 – 1.92) | 0.932 |

| 3 year follow-up | 0.40 (0.18 – 0.90) | 0.026 | n/a | n/a | 0.64 (0.28 – 1.46) | 0.293 |

| Number of pregnancy | ||||||

| Nulligravida | Reference | |||||

| 1-2 | 0.49 (0.26 – 0.92) | 0.027 | 0.58 (0.23 – 1.52) | 0.271 | 0.31 (0.13 – 0.75) | 0.009 |

| ≥3 | 0.48 (0.27 – 0.85) | 0.012 | 0.61 (0.25 – 1.49) | 0.273 | 0.35 (0.16 – 0.74) | 0.006 |

| Number of deliveries | ||||||

| Nulliparous | Reference | |||||

| 1-2 | 0.72 (0.43 – 1.20) | 0.209 | 1.09 (0.54 – 2.20) | 0.820 | 0.43 (0.20 – 0.90) | 0.026 |

| ≥3 | 0.58 (0.36 – 0.94) | 0.029 | 0.91 (0.46 – 1.81) | 0.796 | 0.37 (0.18 – 0.75) | 0.005 |

| Predictor variables | All | HIV-positive (+) | HIV-negative (-) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age (years) | 0.94 (0.92 – 0.96) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.90 – 0.96) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.91 – 0.97) | <0.001 | |

| Age category (years) | |||||||

| ≤29 | Reference | ||||||

| 30-45 | 0.47 (0.25 – 0.90) | 0.022 | 0.11 (0.03 – 0.37) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.35 – 1.97) | 0.667 | |

| ≥46 | 0.19 (0.09 – 0.38) | <0.001 | 0.06 (0.02 – 0.22) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.09 – 0.64) | 0.004 | |

| Number of deliveries | |||||||

| Nulliparous | Reference | ||||||

| 1-2 | 1.46 (0.67 – 3.21) | 0.342 | 1.80 (0.60 – 5.42) | 0.293 | 1.14 (0.37 – 3.52) | 0.820 | |

| ≥3 | 0.90 (0.42 – 1.95) | 0.793 | 1.00 (0.34 – 2.97) | 0.995 | 0.83 (0.28 – 2.45) | 0.731 | |

| Use of contraceptives | |||||||

| No | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 1.65 (1.15 – 2.38) | 0.007 | 1.35 (0.80 – 2.29) | 0.263 | 2.09 (1.25 – 3.50) | 0.005 | |

| Gynecological findings – SCJ | |||||||

| Totally visible | Reference | ||||||

| Partially/Not visible | 2.88 (1.74 – 4.79) | <0.001 | 4.64 (2.33 – 9.22) | <0.001 | 1.73 (0.78 – 3.85) | 0.180 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).