Introduction

Within the dynamic and demanding landscape of the educational sphere, the welfare of school teachers has emerged as a pivotal focal point. Educators face numerous challenges, ranging from escalated workloads to the complexities of student interactions, culminating in heightened stress levels that can adversely affect job satisfaction, efficacy, and overall well-being. Notably, elevated stress levels have been shown to impact both teacher well-being and the classroom climate (Flook et al., 2013). In response to these challenges, there has been a growing interest in exploring alternative methodologies to boost the well-being of educators. Among these methodologies, mindfulness practices have gathered significant attention for their potential to mitigate stress, fortify resilience, and foster a positive work environment.

Mindfulness, as conceptualized by Kabat-Zinn (1991), involves intentionally focusing one’s attention on present experiences in a purposeful and accepting manner, without judgment. This approach underpins the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) framework. Rooted in age-old contemplative traditions, mindfulness entails the cultivation of heightened awareness and a non-judgmental focus on the current moment. Over recent decades, mindfulness has transcended its traditional spiritual origins and has found application across various secular domains, including the educational realm. Research spanning diverse fields has shed light on the benefits of mindfulness on mental health, stress alleviation, and overall well-being. However, despite the implementation of mindfulness interventions within educational contexts, there persists a discernible need for targeted research dedicated to scrutinizing their impact on the well-being of school teachers. Mindfulness practices, as evidenced by Hwang et al. (2017), exhibit a propensity to reduce stress and foster awareness of both body and mind. Various mindfulness exercises, such as yoga poses, intentional breathing, and guided meditation, can be employed for this purpose.

This research aims to augment the growing body of knowledge on mindfulness in education by evaluating its efficacy in mitigating stress and enhancing well-being among school teachers. By centring on the distinctive context of educational institutions, this study aspires to furnish insights directly germane to the challenges confronted by educators in their day-to-day professional endeavours.

In recent years, educational systems worldwide have undergone profound transformations, concomitant with heightened expectations and accountabilities for educators. The demands accompanying these transformations have underscored the imperative of strengthening the mental and emotional welfare of school teachers. While numerous studies have scrutinized the impact of stress on educators, comparatively fewer have delved into the potential of mindfulness practices as a panacea for these stressors (Carroll & Hepburn, 2022; Tsang, 2021)

This research aligns with the broader societal acknowledgment of the paramount importance of mental health and well-being. In the educational sector, the welfare of school teachers assumes paramount importance not only for their personal contentment and efficacy but also for fostering an optimal learning milieu for students. As educators navigate their multifaceted roles as mentors, facilitators, and leaders, their own well-being becomes inextricably intertwined with the prosperity and flourishing of the educational community at large (Song et al., 2020).

Problem Statement

The prevalence of high stress levels among school teachers adversely affects their well-being and job performance. Given the demanding nature of the education profession, effective strategies to mitigate stress and enhance well-being are essential. While mindfulness practices present promising solutions, their specific efficacy within educational settings warrants thorough investigation and evaluation.

Objectives

To assess the baseline levels of stress among school teachers.

To investigate the impact of mindfulness practices tailored for the school context.

To examine the impact of the mindfulness intervention on enhancing well-being indicators among school teachers.

Null Hypothesis (H0)

There is no significant difference in stress levels and well-being indicators among school teachers before and after participating in mindfulness practices.

Alternate Hypothesis (H1)

There is a significant difference in stress levels and well-being indicators among school teachers before and after participating in mindfulness practices, indicating that mindfulness practices effectively reduce stress and improve well-being.

Literature Review

The teaching profession continues to struggle with widespread stress and burnout, affecting not only individual well-being but also classroom effectiveness. Recent evidence from a systematic review suggests that teacher burnout surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, fueled by increased work demands, uncertainty, and technostress (Pressley, 2021; Goldstein et al., 2023). Another recent study found that mindfulness-based interventions meaningfully reduced teacher stress, burnout, and depression, underscoring their promise as practical support tools in education (Phan et al., 2025).

Teacher Well-Being and Stress

Teachers’ well-being is influenced by contextual factors, including school environment and workload, affecting job satisfaction and intent to leave the profession (Travers, 2017). The stress of managing student behavior and disciplinary issues further contributes to burnout (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2010; Lambert et al., 2015). Studies emphasize the importance of teacher well-being for creating supportive learning environments and positive student outcomes (Flook et al., 2013; McCallum and Price, 2010).

Long-term stress in teaching frequently results in burnout, which includes symptoms like feeling emotionally drained and developing a detached attitude toward students, dimensions commonly assessed through the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach et al., 1996).

Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Teacher Well-Being

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have gained attention for their potential to improve teacher well-being and reduce stress (Roeser et al., 2013). Research suggests that MBIs enhance teachers’ psychological well-being, mitigate distress, and improve physical health, thus positively impacting classroom climate and instructional practices (Klingbeil & Renshaw, 2018).

Cross-Cultural Considerations and Short-Term Mindfulness Training

Although mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been widely studied in Western contexts, their applicability across different cultural settings remains underexplored, highlighting a need for more diverse research (Henrich et al., 2010). Short-term mindfulness training (MT) has shown promise in reducing stress among teachers, offering a more accessible alternative to traditional long-term interventions (Zeidan et al., 2010a).

Studies have shown that even brief mindfulness programs can yield benefits across diverse school settings, including primary schools (Rix & Bernay, 2014).

Conclusions

The literature reviewed underscores the significance of addressing teacher stress and promoting well-being among school teaching staff. Mindfulness-based interventions emerge as promising strategies for supporting teacher mental health and creating more conducive learning environments. This study builds upon this foundation by specifically investigating the efficacy of a brief, structured mindfulness program within the unique context of Pakistani school settings, aiming to provide practical insights for educators facing high-demand environments.

Methodology

This study employed a one-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention on reducing stress and enhancing the overall well-being of school teachers. This design was selected due to its practical applicability in real-world educational contexts where random assignment to control groups is often unfeasible. The design facilitated the assessment of changes in participants’ stress and well-being levels by comparing measurements taken before and after the mindfulness intervention within the same group.

Population

School teachers currently employed in private or public schools in Pakistan, aged 25 years or older, with at least 3 years of teaching experience.

Sample

Total 30 initial participants were included in the study.

Sampling Technique

School teachers were recruited for participation through public announcements disseminated via popular social media platforms (Facebook and Instagram). The recruitment advertisement invited school teachers to enroll in a complimentary counseling and mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Prospective participants attended an initial online orientation session via Microsoft Teams, during which the study’s objectives, structure, and voluntary nature were thoroughly explained.

Following this, individuals expressing interest were required to complete a digital participatory consent form and confirm their eligibility based on the following inclusion criteria:

Currently employed in a school (private or public sector)

Minimum 3 years of teaching experience

Aged 25 years or older

Willingness to attend all sessions and complete follow-up questionnaires

Instrument

This study employed a structured self-report questionnaire administered at two time points: pre- and post-intervention. The instrument comprised 15 items organized into three domains: (1) Physical and Emotional Stress Symptoms, (2) Perceived Stress and Coping, and (3) Well-being, Mindfulness, and Resilience (contextual). The items were adapted from two established instruments: the Teacher Stress Inventory (TSI) by Fimian (1984) and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) by Cohen et al. (1983).

Adaptation Process

Items were reviewed for contextual and linguistic relevance to Pakistani school settings. Revisions were made to ensure comprehension and cultural appropriateness for school teachers with varying degrees of familiarity with psychological terminology. Examples of adaptations include:

TSI item “I feel emotionally drained by my work” was simplified to “I feel emotionally exhausted after a day at school.”

PSS item “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and ‘stressed’?” was reworded as “I often feel nervous or under pressure due to work.”

Reverse-coded items from the PSS were excluded due to confusion during pilot testing, which initially led to response inconsistencies.

While expert judgment and content review ensured surface-level clarity and face validity, no formal re-validation procedures (such as confirmatory factor analysis or test-retest reliability checks) were performed post-adaptation. This is acknowledged as a key limitation: the adapted scales may differ in psychometric properties from their original validated forms. As such, the internal consistency (measured by Cronbach’s alpha) is reported, but the construct validity and factorial structure remain uncertain. The results derived from these adapted scales should therefore be interpreted with caution regarding their generalizability beyond this specific study context.

Contextual Scale

The third section of the instrument was a contextual-developed scale designed to assess internal states related to emotional regulation, mindful awareness, and interpersonal support among school teachers. This section focused on teacher well-being and resilience within the context of a high-demand educational environment. The items were constructed based on contemporary mindfulness and educator well-being literature and tailored to suit the Pakistani school setting.

Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), with multiple items per construct. The development was informed by prior research on school leadership communication and teacher support frameworks, but no external validation or standardization procedures were applied to this scale. It was not pilot tested or subjected to item analysis prior to full deployment.

Although post-hoc Cronbach’s alpha for this section showed strong internal consistency (Pre: α = 0.75, Post: α = 0.87), further psychometric evaluation is necessary to establish the scale’s validity and dimensionality. Future research should conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and criterion validation to refine this instrument. The lack of prior validation for this custom scale is a significant limitation of the study.

Detail of Intervention

The three-week mindfulness program drew upon core components of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) model, adapted for educators. Breath-focused exercises encouraged participants to focus their attention on their breathing patterns, serving as an anchor for awareness and a tool for calming the mind.

Duration and Frequency

Three live 45-minute virtual sessions conducted via Microsoft Teams (once per week),

Thrice weekly individual practice sessions, each lasting 10–15 minutes.

Ongoing check-ins and encouragement via Microsoft Teams for follow-up, reflections, and support.

The intervention combined theoretical components, experiential mindfulness exercises, and reflection periods to support cognitive, emotional, and behavioral changes in participants.

Mindfulness Techniques Taught

The following evidence-based mindfulness practices were included:

Focused Breathing

Participants were guided to focus their attention on the natural rhythm of their breath to anchor their awareness and reduce mental agitation.

Mindful Walking

A slow, deliberate walking activity aimed at grounding participants in the present moment through attention to bodily sensations during movement.

Mindful Eating

An exercise to cultivate sensory awareness by slowly eating a small food item (e.g., a raisin or cracker), focusing on texture, taste, and smell.

Loving-Kindness Meditation

A practice of silently repeating compassionate phrases (e.g., “May I be happy, may others be safe”) to foster emotional warmth and social connectedness.

Emotion-Focused Mindfulness

Participants learned to notice and name their emotions as they arose (e.g., sadness, stress), with acceptance and without judgment.

Mindful Movement (Gentle Yoga)

Gentle stretches and simple yoga postures were used to promote body awareness and release physical tension.

Each session also included mood reflection activities and personal reflection questions to encourage participants to observe their internal states before and after practice.

Facilitator and Qualifications

The intervention was delivered by a licensed psychologist with a Master’s degree in Psychology and over three years of practical experience in leading mindfulness-based interventions, particularly in educational settings. The facilitator held professional training in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), ensuring the safe and appropriate delivery of practices suitable for adult learners.

Data Analysis Techniques

The data for this study was collected at two time points pre-intervention and post-intervention, using a structured self-report questionnaire composed of 15 items across three domains: Physical and Emotional Stress Symptoms, Perceived Stress and Coping, and Well-being, Mindfulness, and Resilience. The responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. After data collection, quantitative analysis was conducted to assess changes in participants’ stress levels and well-being.

Descriptive statistics were used to compute means and standard deviations for pre- and post-intervention scores. Inferential analysis included the use of a paired sample t-test to evaluate whether the differences in scores before and after the intervention were statistically significant. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of the instrument, with results indicating acceptable reliability (Pre: α = 0.75, Post: α = 0.87). Although no formal re-validation procedures were conducted for the adapted and custom items, the internal consistency supported the instrument’s use for this exploratory study. The statistical analysis focused on identifying whether the mindfulness intervention had a measurable impact on stress reduction and well-being improvement among the participating school teachers.

Confidentiality and Ethical Considerations

All participation in the study was entirely voluntary. Digital written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any data collection. Rigorous measures were implemented to ensure the confidentiality of participant data.

Results

Each domain in

Table 1 shows statistically significant improvement following the mindfulness intervention, with Cohen’s

d values ranging from 0.77 to 0.92, reflecting large effect sizes and suggesting substantial real-world impact. All powers (1-β) exceed 0.90, indicating a very low risk of Type II error. All

p-values < 0.001, meaning results are highly statistically significant.

t-values > 4 confirm that the differences between pre- and post-scores are not due to random variation.

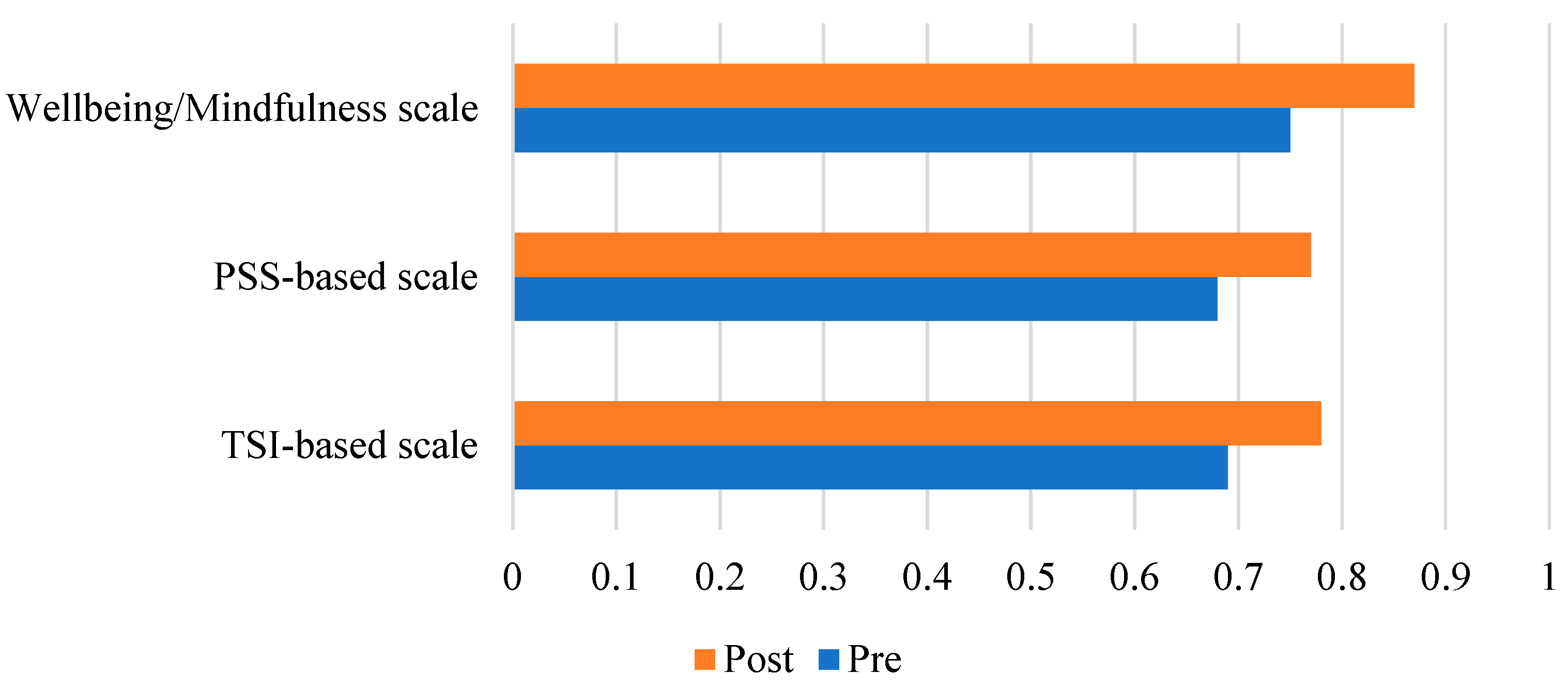

Figure 1 illustrates improved internal consistency across all scales following the mindfulness intervention. Cronbach’s alpha increased from 0.69 to 0.78 for the TSI, 0.68 to 0.77 for the PSS (after adjusting reverse-coded items), and 0.75 to 0.87 for the well-being scale, indicating enhanced reliability and stronger response consistency.

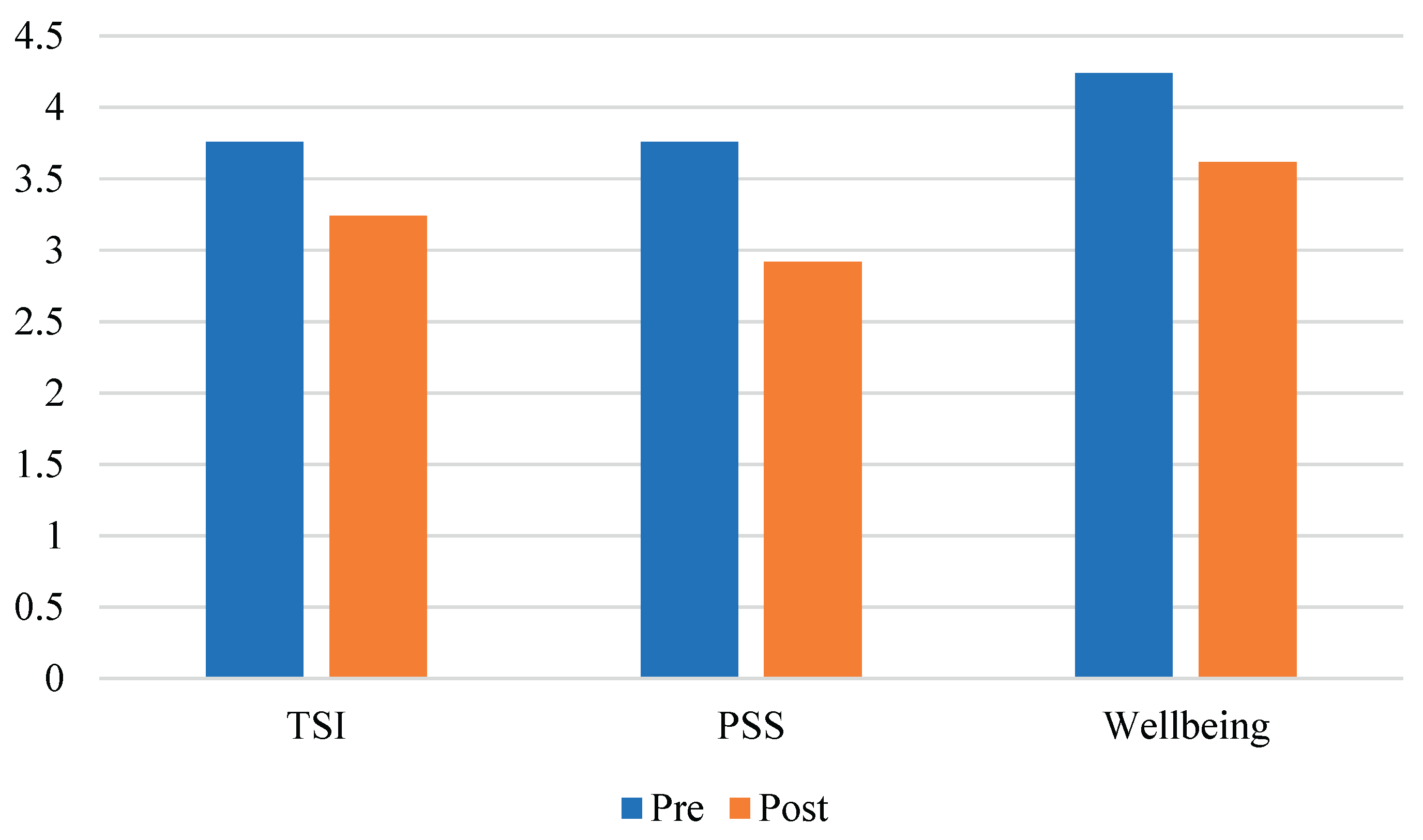

Figure 2 visually supports the effectiveness of mindfulness practices in reducing stress and promoting better emotional regulation among teachers.

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a structured mindfulness intervention on reducing stress and enhancing well-being among school teachers in Karachi, Pakistan. Using a one-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design, the study successfully demonstrated that a brief, context-sensitive mindfulness program can lead to statistically significant and practically meaningful improvements in teacher well-being. The intervention, grounded in the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) model, was tailored to meet the professional and cultural needs of school teachers, delivered virtually via Microsoft Teams to support accessibility and consistency.

The sample consisted of 30 school teachers recruited voluntarily through social media platforms. All participants met specific eligibility criteria, including a minimum of three years of teaching experience. The use of a structured self-report questionnaire, comprising adapted and contextualized items from the Teacher Stress Inventory (TSI), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and a custom-developed well-being scale, allowed for multidimensional assessment across physical, emotional, and psychological domains.

Quantitative data analysis confirmed the intervention’s positive impact. Statistically significant improvements were observed in all three measured domains: Physical and Emotional Stress Symptoms (t = 4.315, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.77), Perceived Stress and Coping (t = 5.001, p < 0.001, d = 0.92), and Well-being, Mindfulness, and Resilience (t = 4.716, p < 0.001, d = 0.85). These results represent large effect sizes according to Cohen’s thresholds, indicating substantial practical significance. Post-hoc power values above 0.98 across all domains further affirm the robustness of the findings, minimizing the likelihood of Type II errors.

The internal consistency of the measurement instruments improved from pre- to post-intervention, with Cronbach’s alpha increasing across all domains (TSI: 0.69 to 0.78; PSS: 0.68 to 0.77; Contextual scale: 0.75 to 0.87). These enhancements suggest that participant understanding and engagement with the items increased after the intervention, particularly following the removal of reverse-coded items from the PSS that initially caused confusion. Despite the absence of formal scale re-validation (e.g., factor analysis or test-retest reliability), the reliability indices support the use of the adapted instruments for exploratory purposes in this study.

Overall, the findings provide compelling evidence that a short-duration mindfulness program, even when delivered virtually, can significantly reduce stress and enhance resilience among educators. This reinforces previous research suggesting that mindfulness practices not only benefit individual psychological well-being but also potentially contribute to healthier school environments. However, given the limitations of a one-group design and the contextual adaptation of instruments without full psychometric validation, caution should be exercised when generalizing these results. Future studies should incorporate control groups, larger sample sizes, and longitudinal designs to examine the sustainability of these benefits over time.

Conclusions

The prevalence of high stress levels among school teachers adversely affects their well-being and job performance, underscoring the critical need for effective interventions in the educational sector. This study investigated the efficacy of mindfulness practices as a solution to this pressing issue.

The null hypothesis (H0) stating that there is no significant difference in stress levels and well-being indicators among school teachers before and after participating in mindfulness practices is rejected. This suggests that there is evidence to support the alternative hypothesis (H1) that mindfulness practices have an effect on reducing stress and enhancing well-being. The findings of this study align with existing literature on the benefits of mindfulness-based interventions for educators, demonstrating that even a brief, structured program can yield significant positive outcomes in reducing stress and enhancing well-being among school teachers. These results underscore the potential of mindfulness as a practical and effective strategy for promoting mental health and resilience within demanding educational environments.

Despite these promising findings, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Specifically, the one-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design limits the ability to infer causality definitively due to the absence of a control group. Additionally, the instruments used, while adapted from established scales, did not undergo formal psychometric re-validation (e.g., confirmatory factor analysis or test-retest reliability checks) post-adaptation, and the custom-developed scale lacked prior external validation. The relatively small sample size also restricts the generalizability of these findings.

Future research should build upon these findings by incorporating control groups, larger and more diverse samples, and longitudinal follow-ups to further establish the long-term efficacy and generalizability of such interventions. Additionally, further psychometric validation of adapted and custom instruments is crucial for advancing the rigor of research in this area.

In conclusion, this study provides compelling evidence that accessible mindfulness interventions can significantly enhance the mental health and resilience of school teachers, ultimately contributing to a more supportive and thriving educational environment for all.

Recommendations

Schools should integrate short-term mindfulness programs into their staff development to reduce teacher stress and improve well-being.

Mindfulness interventions should be culturally adapted for better relevance and effectiveness in local school settings.

Education policies and teacher training curricula should include mindfulness practices as a proactive mental health strategy.

Author Note

Muhammad Zeeshan Rub is a Biology teacher in Karachi with over a decade of experience. He holds a Master’s in Physiology and a Post-Graduate Diploma in Educational Leadership and Management. His research interests include adolescent and mental health, educational leadership, management, and educational technology.

This study was conducted independently. No funding was received, and the author declares no conflicts of interest. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Appendix A

Purpose: Track observable engagement behaviors before (baseline) and at post-test.

Rating scale (class-level tallies):

1 = Not observed, 2 = Rarely (<25%), 3 = Sometimes (25–50%), 4 = Often (51–75%), 5 = Very Often (>75%)

| Rating scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Section A: Physical and Emotional Stress Symptoms (TSI-based) |

| I feel physically exhausted after my workday. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep due to work-related thoughts. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I experience headaches, muscle tension, or fatigue during the school week. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel overwhelmed by my workload or responsibilities. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I find myself becoming easily irritated or frustrated at work. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Section B: Perceived Stress and Coping (PSS-based) |

| I feel nervous or stressed about things beyond my control. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel that I am unable to control important aspects of my work life. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel that difficulties are piling up so high that I cannot overcome them. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel overwhelmed when faced with unexpected changes in my schedule. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I struggle to manage my emotions during stressful situations at school. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Section C: Wellbeing, Mindfulness, and Resilience (Custom/Contextual) |

| I am able to remain calm during challenging moments at school. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel emotionally balanced during my working hours. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I am able to focus on one task at a time without becoming distracted. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I take time to reflect on how I feel during the day. |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel supported and connected to others in my school environment. |

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Carroll, A. , Hepburn, S-J., & Bower, J. (2022). Mindful practice for teachers: Relieving stress and enhancing positive mindsets. Frontiers in Education, 7, 954098. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. , Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24(4), 385–396. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fimian, M. J. (1984). The development of an instrument to measure occupational stress in teachers: The Teacher Stress Inventory. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61, 335–344. [CrossRef]

- Flook, L. , Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., Bonus, K., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout, and teaching efficacy. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7, 182–195. [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J. , Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-S. , Bartlett, B., Greben, M., & Hand, K. (2017). A systematic review of mindfulness interventions for in-service teachers: A tool to enhance teacher well-being and performance. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 26–42. [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1991). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte Press.

- Klingbeil, D. A. , & Renshaw, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for teachers: A meta-analysis of the emerging evidence base. School Psychology Quarterly, 33, 501–511. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R. G. , McCarthy, C. J., O’Donnell, M., & Wang, C. (2015). Measuring elementary teacher stress and coping in the classroom: Validity evidence for the Classroom Appraisal of Resources and Demands. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 488–501. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. In C. P. Zalaquett & R. J. Wood (Eds.), Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources (pp. 191-218). The Scarecrow Press.

- McCallum, F. , & Price, D. (2010). Well teachers, well students. Journal of Student Wellbeing 4(1), 19–34. [CrossRef]

- Phan, M. L. , Renshaw, T. L., Domenech Rodríguez, M. M., McClain, M. B., Moo, E. L., Humphries, A., … Parker, B. (2025). Evaluating the effects of a teacher-implemented mindfulness-based intervention on teacher stress and student prosocial behavior. Contemporary School Psychology, 29, 393–409. [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T. , Ha, C., & Learn, E. (2021). Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: An empirical study. School Psychology, 36, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Rix, G. , & Bernay, R. (2014). A study of the effects of mindfulness in five primary schools in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 11, 201–220. [CrossRef]

- Roeser, R. W. , Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Jha, A., Cullen, M., Wallace, L., Wilensky, R.,... Harrison J. (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: Results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 787–804. [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M. , & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1059–1069. [CrossRef]

- Song, X. , Zheng, S., Liu, J., & Wang, M. (2020). Effects of a four-day mindfulness intervention on teachers’ stress and affect: A pilot study in eastern China. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1298. [CrossRef]

- Travers, C. J. (2017). Current knowledge on the nature, prevalence, sources and potential impact of teacher stress. In T. M. McIntyre, S. E. McIntyre, & D. J. Francis (Eds.), Educator stress: An occupational health perspective (pp. 10–28). Springer.

- Tsang, K. K. Y. (2021). Effectiveness and mechanisms of mindfulness training for school teachers in difficult times: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 12, 2820–2831. [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, F. , Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010a). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19, 597–605. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).