1. Introduction

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is universally acknowledged as a vital strategy for enhancing infant survival and development. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines EBF as the practice of feeding an infant solely with breast milk without water or other solid or liquid foods, except for syrups and vitamins, during the first six months of life [

1,

2]. This practice plays a crucial role in reducing both infant morbidity and mortality, as it safeguards against infections and promotes optimal nutritional and cognitive development [

3,

4]. Infants who are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life are 14 times less likely to die from causes such as pneumonia and diarrhea compared to non-breastfed infants [

3]. Despite the well-documented advantages of EBF, child malnutrition persists as a significant public health challenge in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Alarmingly, the latest Demographic and Health Survey (EDS-III, 2023–2024) reveals that 45% of children under five in the DRC suffer from stunted growth, while 7% face acute malnutrition [

5].

Breastfeeding is instrumental in ensuring that infants not only survive but also reach their full growth and developmental potential, thanks to the dynamic nature of breastfeeding and the unique properties of human milk. Human milk is a complete source of nutrition, comprising about 87% water, proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals [

6]. The primary protein, whey, supports growth with essential amino acids. Rich in essential fatty acids like docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA), human milk promotes brain development. Lactose serves as the main carbohydrate, providing energy and aiding calcium absorption. Key vitamins include Vitamin D for bone health and bioavailable iron for effective absorption. Immunological components like secretory IgA protect infants from infections, while oligosaccharides and growth factors foster gut health and growth. Breastfeeding is linked to enhanced cognitive development, with milk composition adapting over time to meet the infant's needs [

3,

6].

Currently, the prevalence of EBF in the DRC is inadequate, with only 53% of infants under six months receiving exclusive breastfeeding. This statistic underscores significant regional disparities, particularly highlighted in Kinshasa, where the breastfeeding rate plummets to just 25% [

5]. Various socio-economic factors, cultural norms, and maternal health conditions influence this practice. Notably, postpartum depression (PPD) emerges as a significant barrier [

7]. Affecting 10% to 20% of women globally, and up to 30% in sub-Saharan Africa, PPD is exacerbated by socio-economic challenges and limited access to mental healthcare. Symptoms of PPD, such as increased fatigue and diminished motivation, often lead mothers to wean prematurely or introduce food substitutes, jeopardizing infant health and increasing the risk of malnutrition and infections [

8,

9]. Postpartum depression (PPD) significantly impacts a mother's ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding. Emotional challenges such as sadness and anxiety can undermine motivation and bonding with infants, leading to reduced breastfeeding rates. Mothers with PPD often experience fatigue and irritability, making breastfeeding feel overwhelming, which can result in a shift to formula feeding. Research shows these mothers tend to stop breastfeeding earlier, affecting infant health. PPD also disrupts hormonal balance necessary for milk production, potentially decreasing supply. Effective support systems, including mental health resources and educational initiatives, are vital in helping mothers manage PPD and encourage breastfeeding, benefiting both maternal health and infant nutrition [

10].

In recent years, Africa has witnessed a concerning decline in exclusive breastfeeding rates This downturn poses serious implications for newborn health and nutrition in a region where breastfeeding is critical for enhancing child survival and well-being. This decline can be attributed to various factors, including the aggressive marketing of complementary foods, formula milk, and cereals that undermine breastfeeding practices [

11,

12]. Additionally, the interplay between a mother’s self-efficacy in breastfeeding and the level of support from male partners significantly influences breastfeeding outcomes. Furthermore, PPD can severely hinder a mother’s ability to initiate and maintain EBF [

10,

13,

14]. Understanding these interconnected aspects is crucial for designing effective interventions to promote and sustain breastfeeding practices throughout Africa.

Data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (2007, 2013, and 2023) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (2010 and 2017) [

5,

15,

16,

17,

18] reveal a troubling trend: while the national landscape in the DRC shows signs of improvement, Kinshasa is experiencing a dramatic decline in exclusive breastfeeding rates. As of 2023, only 25.3% of infants in Kinshasa are exclusively breastfed, starkly lower than the national average of 52.3% [

5]. Immediate action is imperative to identify and address the factors contributing to this reality in Kinshasa, thereby promoting breastfeeding as a public health priority. Previous studies, such as those conducted by Wallenborn et al. [

19], have indicated significant disparities in breastfeeding practices between urban and rural settings. Factors such as urban lifestyle changes, cultural shifts, media influence, lack of familial support, and peer pressure are believed to play a role in the declining rates of EBF in Kinshasa [

20]. Urban areas also tend to exhibit higher incidences of unplanned pregnancies compared to rural regions[

21]. Moreover, mental health issues critically affect a mother’s ability to initiate and sustain breastfeeding [

10,

22].

To date, as intended birth may contribute to high postpartum depression, especially in urban areas, there has been a lack of comprehensive research addressing the interplay between breastfeeding, psychological factors, social support, and other sociodemographic factors within a singular structural model. This study aims to explore how personality traits may influence exclusive breastfeeding, potentially mediated by self-efficacy. Although few studies have investigated the impact of PPD on EBF practices in the DRC [

23,

24], understanding this relationship is essential for identifying psychological barriers to EBF and developing targeted interventions. This study seeks to illuminate the complex relationships among exclusive breastfeeding, postpartum depression, male partner support, dietary diversity, and child morbidity through the application of structural equation modeling (SEM). By integrating these variables, we can gain deeper insights into how maternal and familial factors influence breastfeeding practices, ultimately facilitating the development of interventions designed to enhance breastfeeding rates. This research contributes to the growing body of literature emphasizing the need for a multifaceted approach to maternal and child health, highlighting the importance of support systems and nutritional considerations in fostering exclusive breastfeeding.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study employed a cross-sectional analytical design, conducted from 15 September to 8 October 2025 in seven main hospitals in Kinshasa City (CME BARUMBU, CS MOSOSO, General Reference Hospital of MATETE, Maternity DE BINZA, Maternity de Kingasani, Maternity of Kintambo, and Hospital Saint Gabriel). The maternity wards in Kinshasa have the highest volume of prenatal, preschool, and postnatal consultations, serving all socio-economic demographics within the city province. The target population consisted of mother–child dyads, specifically mothers with children aged 0 to 6 months, recruited during preschool and postnatal consultations across the above health facilities. This age group was selected due to its critical importance for breastfeeding practices and its influence on child growth and development. Participants were mothers aged ≥18 years with a child aged 0–6 months, recruited during preschool or postnatal consultations, in selected health facilities. Exclusions were made for children with severe pathologies and mothers experiencing significant obstetric complications.

2.2. Sample Selection

The sample size was determined using the formula for estimating proportions in cross-sectional studies (OpenEpi), taking into account a 95% confidence level and an estimated exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) prevalence of 53% (EDS-III/RDC, 2023–2024) [

5]. An anticipated minimum required sample of 766 mother–child pairs was adequate using a clustering effect of 2. Considering a non-response rate of 5%, the sample size was increased to 806. All mothers of children aged 0 to 6 months attending the seven above maternities for preschool and postnatal consultations during the data collection period were invited to participate. Finally we reached 793 instead of the 806 (Response rate of 98.4%).

2.3. Variables of the Study

The primary dependent variable was the practice of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), defined by the WHO as feeding a child aged 0 to 6 months solely with breast milk, without any water, other liquids, or solid foods. EBF was measured through direct interviews with mothers using a 24 h dietary recall, expressed both as a binary variable and as a percentage of children exclusively breastfed the day prior to the survey. To compare estimated measures of exclusive breastfeeding from different methods, we employed three methods based on large-scale household surveys:

EBF-24H: Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among infants less than 6 months based on a 24 h recall.

Self-Declaration: EBF status based on a one-question self-declaration by the mother: “Did you feed your child only breast milk yesterday?”

EBF-SB: Percentage of infants less than 6 months who had not been given anything other than breast milk since birth.

The secondary dependent variable was the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale—Short Form (BSES-SF). This self-report questionnaire evaluates the self-efficacy levels of breastfeeding mothers. The BSES-SF consists of 14 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater breastfeeding self-efficacy [

25]. The internal consistency of the scale was assessed, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 in this study.

The main independent variables were dietary diversity, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Spouse Postpartum Social Support, and child morbidity. Dietary intake was assessed using a 24 h recall method. Foods were classified into the ten Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD_W) food groups: (1) grains, white roots, tubers, and plantain; (2) pulses; (3) nuts and seeds; (4) dairy; (5) meat, poultry, and fish; (6) eggs; (7) dark green leafy vegetables; (8) other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; (9) other vegetables; and (10) other fruits. A point was allocated for each group consumed, with a range of 0 to 10. Adequate dietary diversity is defined as MDD_W ≥ 5, while inadequate diversity is indicated by MDD_W < 5, serving as a binary indicator. The cumulative MDD-W scores were categorized into variables: adequate dietary diversity (consuming five or more food groups) and inadequate dietary diversity or dietary monotony (consuming fewer than five food groups) [

26]. Dietary diversity was measured according to a single 24 h recall using the MDD_W food group classification. We acknowledge that a single day may not reflect habitual intake, increasing the possibility of random measurement error; this limitation was anticipated and is discussed below. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [

27]: This internationally validated scale comprises 10 items reflecting symptoms experienced in the past week, such as sadness, anxiety, and feelings of incompetence. The total score can be anywhere from 0 to 30, and each item is rated from 0 to 3 based on how bad the symptoms are. A score of ≥13 indicates the presence of probable PPD, allowing the identification of mothers potentially experiencing psychological distress that may influence EBF practices. The internal consistency of the scale was assessed, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 in this study. The husband’s support in exclusive breastfeeding tool included seven items assessing spousal support using a five-point Likert scale (see

Table S1). The items are derived from consultations with specialists in maternal and child health, as well as a prior studies executed in Kinshasa [

28,

29,

30,

31]. These items were formulated in conjunction with lactation experts. This questionnaire was evaluated with a target group to ascertain its clarity and relevance, hence enhancing the validity of the questions. The internal consistency of the scale was assessed, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 in this study. To accurately assess the incidence of illness (morbidity in the last 2 weeks) among children in the two weeks leading up to the survey, in this study, the child was considered to have had an illness when they encountered at least one of the three childhood illnesses (acute respiratory infections/cough, diarrhea, fever) and categorized as ‘yes’, while those who had none of them were categorized as ‘no’ [

32]. This approach was implemented to mitigate information bias and ensure reliable data collection. One in four observations missed this data.

The other covariates included basic characteristics (ages of participant and child, mother’s educational level, religion, marital status, number of prenatal consultations attended, parity, household size, complications during pregnancy/or childbirth, nutritional advice during pregnancy, child sex, and childbirth weight). The study used the DHS Equitool for household respondent wealth classification [

33].

2.4. Data Collection

The data collection process was carefully crafted to guarantee high-quality results through structured individual interviews using a validated questionnaire. A team of 15 trained enumerators undertook the task, supervised daily for consistency and accuracy over a 21-day period. Smartphones with the surveyCTO application facilitated streamlined data collection, enabling real-time monitoring and feedback. Daily consistency checks identified discrepancies, ensuring reliability. After data collection, the information was securely stored on a dedicated server, followed by a quality examination before analysis in Stata 18 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Entries failing predetermined validity criteria, such as incomplete responses, were excluded to ensure that only high-quality data contributed to the findings. This meticulous approach aimed to preserve data integrity and enhance the validity of the results.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Proportional estimates and confidence intervals for EBF status were derived, and chi-square tests were conducted to assess relationships among categorical variables. T-tests were employed to compare means of continuous variables across EBF categories. The analysis employed a Venn diagram to illustrate the interrelations among three principal variables concerning exclusive breastfeeding: self-reported exclusive breastfeeding (Self-Declaration), exclusive breastfeeding at 24 h EBF-24H, and exclusive breastfeeding as determined by EBF-SB. A total of 793 records were examined, uncovering significant insights into the intersection and distribution of these variables.

Proportional estimates and confidence intervals for EBF status were derived, and chi-square tests were conducted to assess relationships among categorical variables. T-tests were employed to compare means of continuous variables across EBF categories. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the effects of independent variables on EBF status, adjusting for potential confounders.

This study employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to explore the relationships between various factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding practices among a sample of 793 participants. Before starting on the pathway, we ran bivariate analysis with all independent variables with the two dependent variables (Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and the exclusive breastfeeding in the last 24 h). Before the SEM analysis, we did bivariate analyses to look at how the independent variables were related to the two dependent variables, the Exclusive Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale. This initial step was essential for pinpointing significant associated factors and guiding the delineation of the SEM pathways, as outlined in foundational literature on structural equation modeling [

34,

35,

36]. The significant relationships found in the bivariate analysis guided the pathway in the structural equation modeling. Its ability lies in the assessment of latent variables at the observation level and in testing hypothesized relationships between latent variables at the theoretical level [

37], and hence the SEM was the preferred analytical strategy for analyzing the relationships among the constructs (maternal characteristics, infant characteristics, postnatal complications, breastfeeding techniques, and exclusive breastfeeding initiation) simultaneously in our hypothetical model [

38].

The SEM analysis utilized maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors, accounting for clustering within facilities. The standardized root mean squared residual was 0.014 and the coefficient of determination was 0.220. Endogenous variables included the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and exclusive breastfeeding in the last 24 h. The model incorporated several exogenous variables: child age, religion, dietary diversity score, nutritional education, morbidity of the child in the last 2 weeks, husband’s support in exclusive breastfeeding, probable major maternal depression, mother’s educational attainment, mode of birth, complications during pregnancy, and socioeconomic status. To address potential missing data, the analysis employed a maximum likelihood with missing values approach. Model fit was evaluated through iterations of log pseudolikelihood, with close attention paid to goodness-of-fit statistics to ensure the robustness of relationships among variables. This methodology enabled a comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to breastfeeding practices, setting the stage for targeted interventions.

In the sensitivity analysis, we ran SEM with the default standard error, and the strength of fit of the SEM model was investigated based on multiple indices, including the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). The following cut-off values, which were suggested by Hu and Bentler [

39], indicate a good fit: our RMSEA was 0.035, which is less than 0.06; CFI was 0.965, which is over 0.95; and TLI was 0.885, which less than 0.95. Missing data was handled using multiple imputations by chained equations with m = 20 imputations. We combined estimates using Rubin’s rules and contrasted results with a complete-case analysis (

Table S2). The imputation model included all variables from the analytical model, plus auxiliary predictors related to missingness. Convergence and plausibility were assessed via trace and over-imputation diagnostics. A significance level of

p < 0.05 was set to ensure robust results.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health of Kinshasa (approval no. ESP/CE/83/2025, on 11 April 2025). Informed consent was obtained from each participant, explaining the study objectives and their right to refuse or withdraw without consequences. Confidentiality was maintained by anonymizing data and storing it securely on a protected computer accessible only to the research team.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The average mother’s age was 28.74 years (SD ± 5.72), with approximately 6 out of 10 women aged between 25 and 34. A majority of mothers (93.1%) had attained secondary school education or higher. The marital status of participants indicated that 87.3% were married or in a union. Additionally, 62.4% of mothers were engaged in housekeeping or other home occupations. The average household size was 5.3 ± 2.2 members, and the socioeconomic status analysis indicated that 58.5% of households were in the highest quintile.

A total of 84.0% of mothers reported receiving nutritional advice during pregnancy. Furthermore, 80.1% attended four or more antenatal care sessions. The results showed that 84.2% of births were vaginal deliveries, with a mean birth weight of 3197.89 g (SD ± 572.45). Among children, one out ten (9.4%) had a history of low birth weight (BW < 2500 g). About 36.0% experienced morbidity in the past two weeks, with cough (27.0%) being the most prevalent symptom. The prevalence of diarrhea and fever during the past two weeks was estimated at 11% among the children studied.

3.2. Dietary Diversity, Depression, Male Partner Support, and Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy

Table 2 presents the consumption frequency of various food groups among the studied population. A total of 777 participants reported consuming grains, white roots, tubers, and plantains, indicating a high prevalence at 97.6%. Dairy products followed closely, with 62.9% (501 participants), while pulses—including beans, peas, and lentils—were consumed by 24.9% (198 participants). In contrast, the consumption of meat, poultry, and fish was significantly lower, with only 90.2% (718 participants) reporting regular intake. Other notable findings include egg consumption at 21.5% (171 participants), and a modest intake of dark green leafy vegetables (67.3%, 536 participants) and of various vegetables and fruits ranging, respectively, from 86.7% to 36.9%. Dietary diversity was assessed with a mean diversity score of 5.44 (±1.48). The results indicate that 22.4% of participants exhibited inadequate dietary diversity, while 77.6% (95%CI: 74.6–80.4) achieved an adequate diversity level. The prevalence of possible depression (EPDS ≥ 10) was 12.4%, while 5.7% of women had probable major depression (EPDS ≥ 13). The average scores of Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and husband’s support in exclusive breastfeeding were, respectively, 48.04 and 23.04.

The results show that 45 out of 793 participants probable major depression (

Table 2). Of those who did not plan or want their birth, 7.43% experienced depression. Meanwhile, only 4.29% of those who planned or wanted their birth showed signs of depression. This suggests that birth planning may reduce the risk of major depressive symptoms postpartum (

p = 0.058), even if the

p-value was slightly over the alpha set for this study.

3.3. Exclusive Breastfeeding Prevalence

Figure S1 presents the estimated percentage of infants who were exclusively breastfed according to the survey for each of the three measures described above. The proportion of infants in the study sample who were exclusively breastfed was 29.1% (95% CI: 26.0–32.3%) using EBF-24H, 34.9% (95% CI: 31.4–38.6%) according to the “Self-Declaration”, and 25.1% (95% CI: 22.2–28.2%) using EBF-SB. About 190 (24%) validated exclusive breastfeeding across all three metrics, underscoring a robust concordance across the variables. Ultimately, 509 records (64%) did not indicate exclusive breastfeeding through any of the three metrics.

3.4. Factors Associated with Exclusive Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Score in Bivariate Analysis

Table 3 reveals no significant association between maternal age, marital status, occupation, household size, and socioeconomic level with exclusive breastfeeding. Nonetheless, educational level exhibited a statistically significant link (

p = 0.023), indicating higher exclusive breastfeeding rates among individuals with lower educational attainment. Religious affiliation exhibited significance (

p = 0.002), indicating that participants from the evangelical Church reported elevated rates of exclusive breastfeeding in comparison to other religious groups. Child factors, especially age, were significantly impactful (

p < 0.001), with younger newborns (0–1 month) demonstrating higher exclusive breastfeeding rates compared to older infants. Morbidity in the preceding two weeks markedly decreased exclusive breastfeeding rates, particularly in cases of cough and fever, which correlated with diminished EBF rates among the impacted children (

p < 0.001 and

p = 0.002, respectively). The results indicate that socio-demographic factors, in conjunction with health circumstances, significantly influence exclusive breastfeeding behaviors.

Mothers of exclusively breastfed infants possess a greater dietary diversity score, averaging 5.62, in contrast to 5.40 for those whose infants are not exclusively breastfed; nonetheless, the difference is only marginally significant (

p = 0.056). The mother’s self-efficacy score is markedly elevated for exclusively breastfed newborns, averaging 49.62, in contrast to 47.63 for non-exclusively breastfed infants (

p < 0.001). The support from husbands in the exclusive breastfeeding score is significantly higher for infants who are exclusively breastfed, averaging 24.32, compared to 22.63 for those who are not exclusively nursed (

p = 0.002). Data also suggests that mothers in the higher quintile experience significantly greater confidence in their breastfeeding abilities compared to those in the middle quintile (

Figures S2–S4).

3.5. Factors Associated with Exclusive Breastfeeding and Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Using SEM

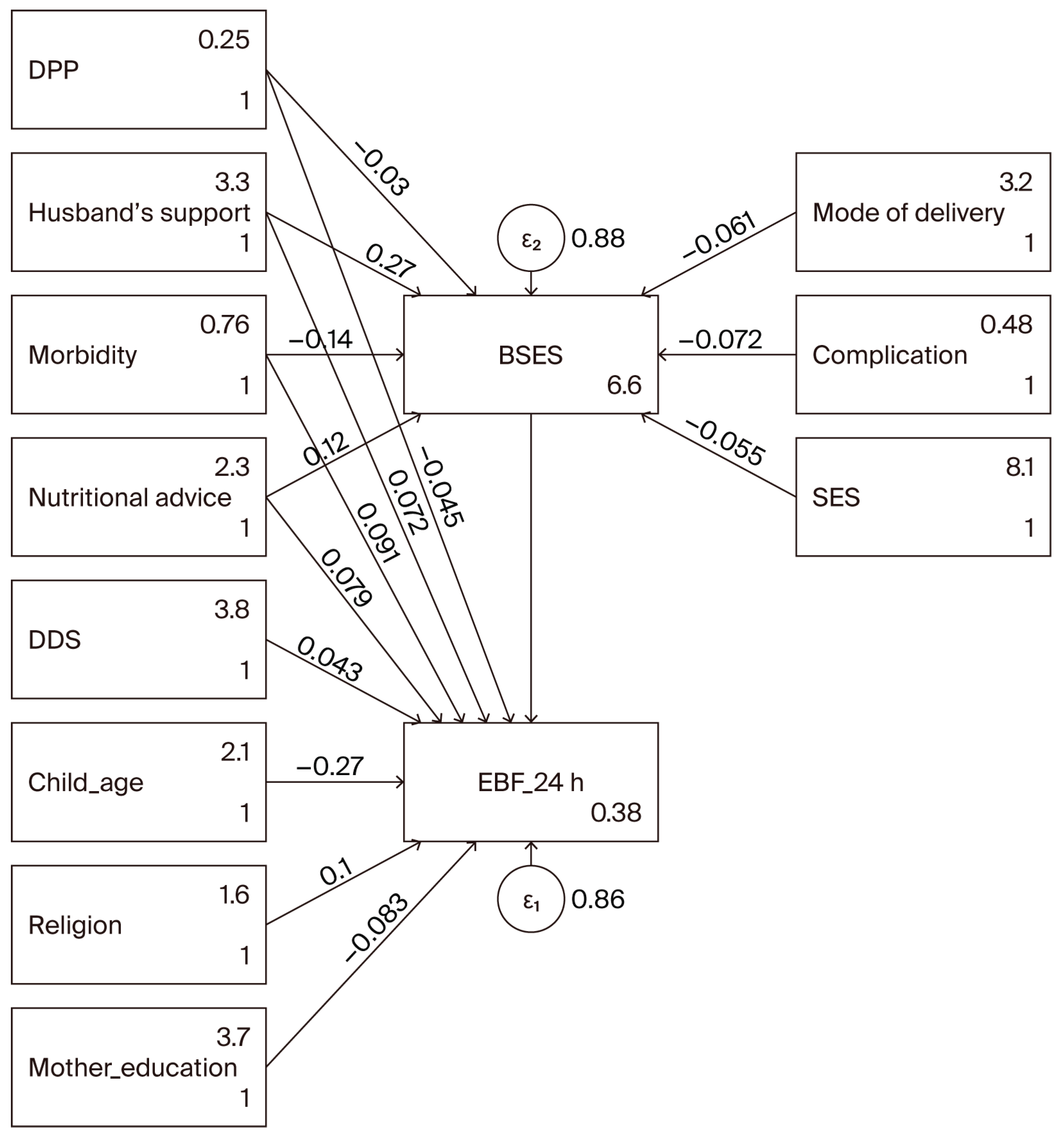

This analysis utilized structural equation modeling (see

Table 4 and

Figure 1) to investigate the associated factors of exclusive breastfeeding at 24 h and breastfeeding self-efficacy ratings across 793 mother–child pairs. The model was calibrated using maximum likelihood estimation, with missing data addressed via the maximum likelihood with missing values approach. The Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy score is positively influenced by nutritional advice during pregnancy, with a coefficient of 2.25, indicating that improved education in nutrition significantly correlates with increased breastfeeding support (

p = 0.044). However, child morbidity in the last 2 weeks showed a negative association with Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy (coefficient = −2.01,

p = 0.070), implying that higher morbidity rates are associated with lower breastfeeding support. The husband’s support in exclusive breastfeeding positively correlates with both Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy (coefficient = 0.26,

p = 0.002) and EBF (coefficient = 0.0058,

p = 0.058). A significant negative relationship exists between child age and EBF (coefficient = −0.0847,

p < 0.001), suggesting that as the child ages, exclusive breastfeeding rates may decline. Conversely, religion positively influences EBF (coefficient = 0.0441,

p = 0.029), indicating that cultural and religious contexts play an important role in breastfeeding practices. There is a noteworthy negative effect of mother’s education on EBF (coefficient = −0.1490,

p = 0.006), suggesting that education levels may inversely affect practices of exclusive breastfeeding, possibly due to varying perceptions and priorities regarding breastfeeding among educated mothers.

Post-estimation diagnostics revealed an adequate model fit, demonstrated by an R-squared value of 0.15 for the overall model, with goodness-of-fit statistics indicating potential areas for improvement. Exploring further variables or reassessing the model framework may enhance predictive accuracy. Model statistics showed that the model adequately fit the data (RMSEA = 0.035, CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.885). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) indicate that although the model demonstrates a satisfactory fit, further refining is required.

In a sensitivity analysis, when comparing complete-case and MICE approaches, the MICE methodology frequently uncovers subtle correlations that may be concealed in whole-case analyses, offering a more thorough comprehension of the determinants affecting exclusive breastfeeding. Consequently, employing MICE not only strengthens the validity of the findings but also augments the clarity of the data, finally facilitating improved actions for advancing EBF (

Table S2).

4. Discussion

In this study, we estimated the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in three ways among the same populations, and identified key factors associated with breastfeeding. The EBF status based on a one-question self-declaration by the mother resulted in the highest estimates. The EBF-24H indicator was higher than the EBF-SB indicator. Several factors had an effect: (1) failure to capture prelacteal feeding; (2) failure to capture intermittent use of complementary feeds; and (3) the assumption that the feeding pattern at the time of the survey will continue until 6 months of age [

40,

41,

42]. EBF-SB is more sensitive to the first two issues; that is, it can capture both prelacteal feeding and the intermittent use of complementary feeds. Using EBF-SB produces results lower than those of the other two methods. The prevalence of EBF reported in this study is much lower than the national estimate reported by the most recent DHS in DRC [

5].

Breastfeeding self-efficacy refers to a mother’s confidence in her ability to breastfeed successfully. Our results indicate that higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with an increased likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding. This aligns with existing works in the literature suggesting that mothers who believe in their ability to breastfeed are more likely to initiate and maintain breastfeeding practices [

25,

43]. Enhancing breastfeeding self-efficacy can be achieved through targeted interventions such as prenatal education programs, where mothers receive information and support focused on breastfeeding techniques and overcoming common challenges. Peer support groups and mentorship programs can also play a pivotal role in reinforcing mothers’ confidence and ensuring they feel supported throughout their breastfeeding journey [

44]. It should be noted that, as shown by the results of this study, the role of the husband/male partner’s support emerged as a critical associated factor in breastfeeding self-efficacy. Our study found that when husbands are actively involved and supportive, mothers report higher levels of confidence in their breastfeeding abilities. This finding is consistent with research that highlights the positive impact of paternal involvement on maternal health outcomes [

45]. Husbands can provide emotional support and practical assistance, which can alleviate stress and encourage mothers to persist with breastfeeding, especially during challenging times. Therefore, it is essential to include fathers in prenatal education and breastfeeding support programs. Engaging fathers not only strengthens family bonds but also creates an environment conducive to breastfeeding success. When thinking about prenatal education and breastfeeding support programs, there is a need to think differently about current practices regarding nutritional advice during pregnancy. Nutritional advice during pregnancy was also positively associated with breastfeeding self-efficacy in our study. Proper nutrition is fundamental for mothers, as it affects both their health and their capacity to produce milk. Research has shown that women who receive adequate nutritional guidance are more likely to feel empowered and capable of breastfeeding successfully [

46]. Healthcare providers should prioritize nutritional counseling as an integral component of prenatal care. Providing mothers with information about dietary choices that support breastfeeding can enhance their confidence and commitment to exclusive breastfeeding. Furthermore, community-based programs that focus on educating mothers about the nutritional aspects of breastfeeding can foster a supportive environment that encourages healthy practices.

Improving BSES will improve EBF practice, as shown in this study. The findings of this study reveal significant relationships between exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and several key factors, including breastfeeding self-efficacy, maternal education level, husband support, nutritional advice during pregnancy, child’s age, morbidity in the last two weeks, and religion. Understanding these associations is crucial for developing comprehensive strategies to promote EBF, ultimately enhancing infant health outcomes. Our results indicate a strong correlation between breastfeeding self-efficacy and the likelihood of maintaining EBF. This underscores the importance of empowering mothers with confidence in their breastfeeding abilities. Interventions that focus on enhancing self-efficacy—such as prenatal education sessions and peer support groups—could play a pivotal role in improving EBF rates. When mothers believe in their capacity to breastfeed successfully, they are more likely to persevere through challenges, leading to longer durations of EBF [

25,

43,

47]. The study also highlights the significant impact of maternal education on EBF practices. Educated mothers are generally more aware of the benefits of breastfeeding and are better equipped to navigate potential barriers. This finding emphasizes the need for targeted educational programs that inform and equip mothers with the knowledge necessary to sustain EBF. Policies aimed at increasing educational opportunities for women could have a cascading effect on improving breastfeeding rates within communities [

3,

48].

Husband support and nutritional advice during pregnancy had a direct influence on EBF or an influence via BSES in this study. Husband support emerged as a critical determinant of EBF, illustrating the importance of familial involvement in breastfeeding practices. Support from partners can alleviate stress and provide emotional encouragement, which is vital during the demanding postpartum period. Programs that engage fathers in prenatal and post-natal education can foster a supportive environment that promotes breastfeeding. Encouraging active paternal involvement not only enhances maternal well-being but also strengthens family dynamics [

45,

46]. The provision of nutritional advice during pregnancy was positively associated with EBF. Access to proper nutrition and guidance can empower mothers to make informed dietary choices that support their health and breastfeeding efforts. Healthcare providers should prioritize nutritional counseling as part of routine prenatal care, ensuring that mothers receive the necessary information to optimize their health and breastfeeding success [

49,

50].

This study also found that child age significantly influenced EBF practices, as younger infants are more likely to be exclusively breastfed. Additionally, higher morbidity in the last two weeks was associated with a decreased likelihood of EBF, suggesting that health complications can hinder breastfeeding efforts. This relationship highlights the importance of monitoring infant health and providing appropriate medical care to support continued breastfeeding. Pediatric healthcare providers should advocate for and support breastfeeding, particularly during periods of illness [

51,

52]. Finally, the role of religion in shaping breastfeeding practices warrants further exploration. Cultural and religious beliefs can significantly influence maternal attitudes towards breastfeeding. Understanding the religious contexts and values surrounding breastfeeding can inform culturally sensitive interventions that respect these beliefs and integrate them into educational programs [

53,

54].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations. It utilizes a cross-sectional methodology, which restricts the capacity to determine causal links among postpartum depression, nutritional diversity, and exclusive breastfeeding practices. This study did not demonstrate a correlation between depression and the two outcomes (EBF and BSES); however, an extensive study with a larger sample size is necessary to determine whether this relationship exists in Kinshasa, particularly considering the high incidence of unwanted pregnancies [

21,

55], which also affects postpartum depression, as previously noted. Longitudinal studies are essential for comprehending the temporal dynamics and causality of these connections. Dependence on self-reported questionnaires may introduce bias, as mothers may underreport symptoms of postpartum depression or exaggerate their breastfeeding practices according to social desirability. Future research may benefit from the incorporation of clinical assessments in mental health evaluations. The sample size, although sufficient for initial findings, may not comprehensively reflect the heterogeneous population of mothers in Kinshasa or other areas of the DRC. Outcomes may also change through various socioeconomic or cultural circumstances. The evaluation of dietary diversity failed to consider specific nutrient intake or the quality of the foods ingested. A comprehensive investigation of food habits could yield further insights into the correlation between maternal nutrition and nursing. Although we endeavored to account for numerous confounding variables, there may be unmeasured factors (such as social support and health literacy) that could affect both maternal mental health and breastfeeding results. The cultural attitudes and behaviors related to breastfeeding and maternal mental health were not thoroughly examined, outside of religion. These factors can have a profound impact on breastfeeding patterns and may limit the generalizability of findings across various cultural contexts. The study occurred within a defined chronological framework, where exogenous variables such as political instability or health emergencies (e.g., the Mpox epidemic, flooding, socio-economic crises) could have impacted maternal mental health and breastfeeding behaviors during this timeframe. Another big and significant limitation of this study is the use of a non-standardized tool to measure husband’s support for exclusive breastfeeding. While the tool was developed to capture relevant dimensions of support, its lack of validation and standardization may affect the reliability and comparability of the results. This limitation raises concerns regarding the accuracy of the assessments and the potential for measurement bias, as the tool may not fully encompass the complexities of spousal support or the various ways in which it can influence breastfeeding practices. Future research should consider employing validated instruments to measure familial support, ensuring more robust and generalizable findings.

This study makes several significant contributions to the understanding of breastfeeding practices, with a particular focus on the interplay between breastfeeding self-efficacy, husband support, and nutritional advice during pregnancy. These contributions are vital for both academic discourse and practical applications in maternal and child health. By examining the direct relationship between breastfeeding self-efficacy and its contributing factors, this study enriches the existing framework on breastfeeding practices. It provides empirical evidence that empowers healthcare practitioners to develop targeted interventions aimed at increasing self-efficacy among mothers. This can lead to higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding, which is crucial for infant health. This research underscores the critical role of husband’s support in breastfeeding journeys. By identifying husband’s support as a significant predictor of breastfeeding self-efficacy, the study advocates for the inclusion of fathers in prenatal education and breastfeeding support initiatives. This contribution not only broadens the scope of the existing literature but also promotes a more inclusive approach to maternal health, recognizing the family unit’s role in successful breastfeeding practices. The findings emphasize the importance of nutritional advice during pregnancy as an associated factor for breastfeeding self-efficacy. This contribution highlights the need for healthcare providers to integrate or strengthen nutritional counseling into routine prenatal care. By focusing on the nutritional needs of expectant mothers, the study advocates comprehensive strategies that support mothers in their breastfeeding efforts, ultimately benefiting both maternal and infant health.

4.2. Practical Implications for Healthcare Providers

The study’s insights offer practical implications for healthcare providers, policymakers, and maternal health programs. By identifying key factors that enhance breastfeeding self-efficacy, the research can inform the design of education and support programs tailored to meet the needs of mothers. This aligns with current public health goals to increase breastfeeding rates and improve maternal and child health outcomes.

4.3. Suggestions for Future Research

This study lays the groundwork for future research exploring the dynamics of breastfeeding support systems. It opens avenues for further investigation into how various familial and social factors influence breastfeeding practices, paving the way for more nuanced and effective intervention strategies.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study highlights the multifaceted challenges faced by mothers in Kinshasa regarding exclusive breastfeeding. The findings of the current study can assist health professionals and decision-makers in designing and implementing culturally tailored interventions to enhance maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy. The findings of this study reveal significant relationships between breastfeeding self-efficacy, husband support, and nutritional advice during pregnancy. These factors are crucial in promoting EBF and can significantly influence maternal and infant health outcomes. By prioritizing maternal mental health and the roles of husband support and nutritional advice during pregnancy, we can create a more supportive framework for breastfeeding practices. Future research should explore longitudinal approaches to understand the long-term effects of PPD and the roles of husband support and nutritional advice during pregnancy on breastfeeding and infant health, as well as the potential benefits of integrated maternal health programs that address both psychological and nutritional needs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding by metric; Figure S2: Relationship between Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy score and dietary diversity score (a) and husband’s support in exclusive breastfeeding score (b); Figure S3: Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy by mother’s characteristics; Figure S4: Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy by mother’s characteristics; Figure S5: Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy by mother’s characteristics; Table S1: Male partner/husbands' support for exclusive breastfeeding; Table S2: Comparative analysis of direct & indirect effects of various factors on exclusive breastfeeding: complete case versus multiple imputation approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; methodology, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; software, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; validation, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; formal analysis, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; investigation, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; resources, G.B.B., F.K.K. and P.A.Z.; data curation, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation: G.B.B., F.K.K. and P.A.Z.; writing—review and editing: G.B.B., F.K.K., B.M.B., P.M.M. and P.A.Z.; visualization, G.B.B. and P.A.Z.; supervision, G.B.B., B.M.B., D.B.B., F.K.K. and P.A.Z.; project administration, G.B.B., F.K.K. and P.A.Z.; and funding acquisition, G.B.B. and F.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review board of the Kinshasa School of Public Health (KSPH; no. ESP/CE/83/2025, 11 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from each respondent during the data collection process, and privacy and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study.

Data Availability Statement

A de-identified dataset and codebook are available at OSF (doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/CSJF4). Any additional materials that cannot be shared openly due to ethical restrictions are available from KSPH upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff involved in data collection, as well as all the respondents for sharing their experiences.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work from the previous three years, nor other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the work submitted.

References

- Akadri, A.; Odelola, O. Breastfeeding Practices among Mothers in Southwest Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2020, 30, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidance on Ending the Inappropriate Promotion of Foods for Infants and Young Children: Implementation Manual; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.; França, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuki, N.; Lee, A.C.; Silveira, M.F.; Sania, A.; Vogel, J.P.; Adair, L.; Barros, F.; Caulfield, L.E.; Christian, P.; Fawzi, W.; et al. The associations of parity and maternal age with small-for-gestational-age, preterm, and neonatal and infant mortality: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2013, 13 (Suppl 3), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDC-Institut National de la Statistique, École de Santé Publique de Kinshasa et ICF. Enquête Démographique et de Santé de République Démocratique du Congo 2023–2024: Rapport Final; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA; Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B.L.; Victora, C.G. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on child health. World Health Organization. 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506120 (consulted on 15 September 2025).

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwoz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G.; Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koray, M.H.; Wanjiru, J.N.; Kerkula, J.S.; Dushimirimana, T.; Mieh, S.E.; Curry, T.; Mugisha, J.; Kanu, L.K. Factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding in Sub-Saharan Africa: Analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, P. Postnatal depression: A global public health perspective. Perspect. Public Health 2009, 129, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezley, L.; Cares, K.; Duffecy, J.; Koenig, M.D.; Maki, P.; Odoms-Young, A.; Clark Withington, M.H.; Lima Oliveira, M.; Loiacono, B.; Prough, J.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.; Buscemi, J. Efficacy of behavioral interventions to improve maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J. 2022, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boyland, E.; Muc, M.; Coates, A.; Ells, L.; Halford, J.C.G.; Hill, Z.; Maden, M.; Matu, J.; Maynard, M.J.; Rodgers, J.; et al. Food marketing, eating and health outcomes in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2025, 133, 781–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.; Beyer, F.; Parkinson, K.; Muir, C.; Graye, A.; Kaner, E.; Stead, M.; Power, C.; Fitzgerald, N.; Bradley, J.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A. Non-Pharmacological Interventions to Reduce Unhealthy Eating and Risky Drinking in Young Adults Aged 18⁻25 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Değer, M.S.; Sezerol, M.A.; Altaş, Z.M. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy, Personal Well-Being and Related Factors in Pregnant Women Living in a District of Istanbul. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavine, A.; Farre, A.; Lynn, F.; Shinwell, S.; Buchanan, P.; Marshall, J.; Cumming, S.; Wallace, L.; Wade, A.; Ahern, E.; et al. Lessons for the UK on implementation and evaluation of breastfeeding support: Evidence syntheses and stakeholder engagement. Health Soc. Care Deliv. Res. 2024, 12, 1–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministère du Plan et Macro International. Enquête Démographique et de Santé, République Démocratique du Congo 2007; Ministère du Plan et Macro International: Calverton, Maryland, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Statistique et Fonds des Nations Unies pour l’Enfance. Enquête par Grappes à Indicateurs Multiples en République Démocratique du Congo (MICS-RDC 2010); Rapport Final; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en œuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM), Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP) et ICF International. Enquête Démographique et de Santé en République Démocratique du Congo 2013–2014; MPSMRM, MSP et ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- INS. Enquête par Grappes à Indicateurs Multiples, 2017–2018; Rapport de Résultats de L’enquête; INS: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Wallenborn, J.T.; Valera, C.B.; Kounnavong, S.; Sayasone, S.; Odermatt, P.; Fink, G. Urban-Rural Gaps in Breastfeeding Practices: Evidence From Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karen, M.K. Breastfeeding and Human Lactation; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Finer, L.B.; Zolna, M.R. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agler, R.A.; Zivich, P.N.; Kawende, B.; Behets, F.; Yotebieng, M. Postpartum depressive symptoms following implementation of the 10 steps to successful breastfeeding program in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldeyohannes, D.; Tekalegn, Y.; Sahiledengle, B.; Ermias, D.; Ejajo, T.; Mwanri, L. Effect of postpartum depression on exclusive breast-feeding practices in sub-Saharan Africa countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C. L. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Prevel, Y.; Arimond, M.; Allemand, P.; Wiesmann, D.; Ballard, T.J.; Deitchler, M.; Dop, M.C.; Kennedy, G.; Lartey, A.; Lee, W.T.; et al. Development of a dichotomous indicator for population-level assessment of dietary diversity in women of reproductive age. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.; Inandi, T.; Yigit, A.; Hodoglugil, N.N. Validation of the Turkish version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale among women within their first postpartum year. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, A.J.; Wood, F.E.; Woo, M.; Gay, R. Impact of the Momentum pilot project on male involvement in maternal health and newborn care in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, A.J.; Akilimali, P.Z.; Wood, F.E.; Gay, R.; Olivia Padis, C.; Bertrand, J.T. Evaluation of the effect of the Momentum project on family planning outcomes among first-time mothers aged 15–24 years in Kinshasa, DRC. Contraception 2023, 125, 110088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, F.E.; Gage, A.J.; Mafuta, E.; Bertrand, J.T. Involving men in pregnancy: A cross-sectional analysis of the role of self-efficacy, gender-equitable attitudes, relationship dynamics and knowledge among men in Kinshasa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, A.J.; Wood, F.E.; Kittoe, D.; Murthy, P.; Gay, R. Association of Male Partners’ Gender-Equitable Attitudes and Behaviors with Young Mothers’ Postpartum Family Planning and Maternal Health Outcomes in Kinshasa, DRC. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilot, D.; Belay, D.G.; Shitu, K.; Mulat, B.; Alem, A.Z.; Geberu, D.M. Prevalence and associated factors of common childhood illnesses in sub-Saharan Africa from 2010 to 2020: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e065257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DHS. Equitool. Available online: https://equitytool.org/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Edition ed; Guilford Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd Edition. ed; Routledge, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley-Interscience, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelishadi, R.; Rashidian, A.; Jari, M.; Khosravi, A.; Khabiri, R.; Elahi, E.; Bahreynian, M. National survey on the pattern of breastfeeding in Iranian infants: The IrMIDHS study. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2016, 30, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Fenta, E.H.; Yirgu, R.; Shikur, B.; Gebreyesus, S.H. A single 24 h recall overestimates exclusive breastfeeding practices among infants aged less than six months in rural Ethiopia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, T. Exclusive breastfeeding: Measurement and indicators. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2014, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, V.; Lee, A.H.; Scott, J.A.; Karkee, R.; Binns, C.W. Implications of methodological differences in measuring the rates of exclusive breastfeeding in Nepal: Findings from literature review and cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.L.; Faux, S. Development and psychometric testing of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, R.J.; Chambers, J. Supporting breastfeeding mothers: A systematic review of the evidence of the effectiveness of breastfeeding peer support. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Lu, J.; Qin, A.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W.; Li, H.; Rao, L. The role of paternal support in breastfeeding outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Int Breastfeed J. 2024, 19, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kearney, J.M.; McElroy, B. The role of fathers in breastfeeding: A critical review. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2010, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, N.; et al. Educating mothers about breastfeeding: A study in the Indian context. J. Pediatr. 2003, 143, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; et al. Effect of nutritional counseling on exclusive breastfeeding among mothers of infants aged 0–6 months: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Health Sci. 2016, 10, 607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, C.D.; Whitsel, L.P.; Thorndike, A.N.; Marrow, M.W.; Otten, J.J.; Foster, G.D.; Carson, J.A.S.; Johnson, R.K. Nutritional counseling and its impact on maternal and child health. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victora, C.G.; et al. Breastfeeding and health outcomes in children: A global perspective. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinara, P.G.; et al. Impact of child morbidity on breastfeeding practices: A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, S.W. The role of religion in breastfeeding practices in the United States. Matern. Child Nutr. 2002, 8, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadare, J.O.; et al. Influence of cultural beliefs on infant feeding practices among nursing mothers in Nigeria. Int. J. Health Sci. 2016, 10, 546–552. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, W.H.; Jhpiego. University of Kinshasa School of Public Health; Performance Monitoring for Action (PMA) Democratic Republic of Congo (Kinshasa) Phase 4: Household and Female Survey (Version #); PMA2024/CDP4-HQFQ; Institute for Population and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).