1. Introduction

The practice of exclusive breastfeeding (EB) from birth to four months of age is common worldwide. Health organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Israeli Ministry of Health, recommend EB up to 6 months of age as the ideal goal, which will be followed by the introduction of solid foods and continued breastfeeding. Before six months, infants are typically not yet developmentally ready to handle solid foods, thus, rendering breastfeeding the ideal source of nutrition at this stage. EB also provides natural antibodies which bolster the infant’s immune system.

The first two years of the baby’s life are critical, and proper nutrition is essential for proper growth and development (Black et al., 2008). Inadequate nutrition increases the risk of both short- and long-term morbidity and mortality, i.e., wasting (low weight for height), stunting (delayed growth), obesity, cognitive impairment, diminished future physical work capacity, and, in female infants, fertility problems (Black et al., 2008; Prado & Dewey, 2014; Ottolini et al., 2020). Moreover, poor early nutrition can lead to the development of unhealthy eating habits that may persist throughout life (Birch et al., 2007). According to data from the WHO and the World Bank, 6.8% of children under 5 years old suffer from wasting, and ~22% experience stunting. The majority of these cases occur in children from developing or third-world countries (mostly, Africa and Asia). However, these conditions are also present in developed countries, with prevalence rates of stunting and wasting at 4% and 0.4%, respectively. Globally, a common nutritional problem is food insecurity, defined as limited or uncertain availability of safe and adequate food or an unreliable ability to acquire food through socially acceptable means. In Israel, a developed country, ~21% of children suffer from food insecurity, with approximately half of these children experiencing severe food insecurity (World Health Organization, 2023).

Childhood obesity, on the other hand, is a more prevalent phenomenon found in developed countries: 7.6% vs. 3.4% in developing countries National Insurance Institute, 2021). Among breastfeeding’s numerous advantages for both infants and mothers is the reduced risk of obesity as well as development of an emotional bond/attachment between mother and infant. Moreover, there is a decreased risk of breast and ovarian cancer for the mother (Dieterich et al., 2013; Ip et al., 2009; Wallenborn et al., 2021). Studies have shown that breastfed infants have a 26% lower likelihood of suffering from obesity or overweight (Victora et al., 2016; Quigley et al., 2016; Rito et al., 2019).

Research has also indicated that EB offers additional benefits, including a reduced risk of mortality in infants due to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). A meta-analysis conducted in the USA found that the risk of SIDS was reduced by 45% in infants who were breastfed (either exclusively or partially); in infants breastfed for at least two months, the risk decreased by 62%, and in infants who were breastfed for a certain amount of time, by 73% (Hauck et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2017). Meek & Noble found that EB may bestow a protective effect against the development of asthma, eczema, lower respiratory tract infections, and type 1 diabetes (Meek & Noble, 2022). Despite the advantages associated with EB, a significant percentage of women worldwide do not breastfeed.

Only three developed countries (USA, Spain, and France) have reported that >80% of mothers have ever breastfed Perez-Escamilla et al., 2023). In 2020, according to the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) data from the USA, breastfeeding initiation rate was 83.1%, with significant differences observed across various socio-economic groups (90.1%, among women in the highest socio-economic versus 75.4% in the lowest socio-economic bracket). The breastfeeding initiation rate among university-educated women was 91.9%, compared to 72.5% who did not complete high school Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). These data indicate that only 45.3% of infants received EB at 3 months; 25.4% at 6 months of age (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). According to the Global Breastfeeding Collective of the WHO and UNICEF, only 48% of infants under 6 months are EB (Global Breastfeeding Collective, 2023). To encourage breastfeeding, many hotlines for breastfeeding mothers have been set up internationally, i.e., the Australian Breastfeeding Association website, which enumerates the advantages of breastfeeding for both mothers and infants and offers help with related problems (Australian Breastfeeding Association website).

1.1. Breastfeeding Practice in Israel

A national health and nutrition survey conducted in Israel between 2019 and 2020 found that the percentage of women practicing EB for a duration of 4 to <6 months was 28.8% (Specht et al., 2018). In another survey conducted in Israel, it was reported that the initiation rate of breastfeeding was ~90%, for all women who began EB in the hospital. However, the rates of EB significantly declined during the postpartum period (during maternity leave). The survey indicated that the primary reason for discontinuing breastfeeding was the difficulty in breastfeeding, i.e., physiological issues and problems with milk supply (National Program for Nutrition and Health Surveys, 2019).

Various factors influence the duration of EB, i.e., demographic and biological, perceptions and beliefs, social, and hospital-related. Demographic factors include age (older women are expected to breastfeed more than younger women); education level (the higher the education, the greater the likelihood of EB); and income level (as income increases, the likelihood of breastfeeding also increases (Victora et al., 2016; Perez-Escamilla et al., 2023). Biological factors primarily relate to the ability to produce milk or a sufficient milk quantity. Moreover, research has shown that mothers who are obese at the time of pregnancy exhibit a lower likelihood of breastfeeding. Factors related to the mother’s perceptions and beliefs include feelings of self-efficacy (the higher the self-efficacy, the greater the likelihood of breastfeeding) (Meek & Noble, 2022); Perez-Escamilla et al., 2023).

Social factors include the mother’s employment status, duration of maternity leave, and support from her partner. Hospital-related factors include policies (such as rooming-in and early initiation of breastfeeding) (Zimmerman et al., 2022; Dieterich et al., 2022). It is essential to raise awareness as to the long-term importance of breastfeeding during the mother’s visits to well-baby clinics. The WHO, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Israeli Ministry of Health recommend EB for the first six months following the birth of the infant [Dieterich et al., 2022; WHO , 2022; Meek et al., 2020; Ministry of Health, 2021; Sundararajan & Rabe, 2021).

1.2. Religious Significance Attributed to Breastfeeding

In the Israeli Arab community (Islam, Christianity, and Druze), breastfeeding holds a significant symbolic value due to religious reasons, hence, we focused on three groups: a non-conservative, conservative, and religious group. A majority of Arab women do not participate in the labor force remaining at home to raise their children. Consequently, breastfeeding is perceived as a fundamental and important issue, similar to global trends, as a result of its health benefits for both infants and mothers. However, also within this community, cultural, social, and economic factors affect the attitudes and practices related to breastfeeding.

In terms of traditional and religious significance, breastfeeding is regarded in Islam as a blessed duty. The Quran specifies the duration of breastfeeding in the verse: “Mothers may breastfeed their children for two complete years for whoever wishes to complete the nursing” (Surat Al-Baqarah [2:233]) (The Noble Qur’an. Surat Al-Baqarah). Breastfeeding is considered a religious obligation of the mother towards the child; however, the child may be transitioned to artificial feeding, if necessary for the child’s welfare . If a mother is unable to breastfeed her child, another woman (wet nurse) is appointed to the role and establishes a bond of “milk kinship” between the infant, wet nurse, and family, a relationship that is recognized in Islam and precisely defined by religious law, giving breastfeeding a spiritual value.(Sivertsev, 2022).

In Christianity, breastfeeding symbolizes maternal care, love, and the spiritual grace conferred by both the mother and the Church. It also serves as a symbol of the spiritual relationship between the believer and the Church. In the Catholic tradition, Mary is often portrayed as the ideal mother. Images of Mary breastfeeding the infant Jesus are perceived as a representation of how she provides life to her son, both physically and spiritually (Mehrpisheh, et al. 2020). In the Druze community, breastfeeding is perceived as an essential part of raising a child, encompassing both physical and cultural values . Similar to many other cultures, breastfeeding is considered an integral part of a mother’s responsibility towards her child, signifying closeness and love (Alchalel et al., 2024).

1.3. Family and Social Factors

In many Arab families, regardless of religious beliefs, there is strong support for breastfeeding from extended family members, such as grandmothers and aunts, who provide guidance on the benefits and techniques of breastfeeding. There is often encouragement to breastfeed for extended periods, and in some cases, even beyond the first year of the child’s life. However, the level of familial support and influence may vary across families. Furthermore, various social factors also impact breastfeeding, i.e., education, age, socio-economic status, ethnic background, health, and cultural beliefs. Socio-economic status also plays a pivotal role. For example, in the United States and the United Kingdom, non-white ethnic groups, particularly, those of Caribbean descent, tend to have lower breastfeeding rates. Cultural beliefs, in particular, exert a significant influence on the likelihood of breastfeeding (Dorri et al., 2022).

Because breastfeeding in the Israeli Arab community is regarded as a key element with significant health, cultural, and religious value, research has reported a steady increase in breastfeeding rates among Israeli Arab women, with studies showing that in the initial months following childbirth, breastfeeding rates rise to between 85% and 90%. Among Muslim women, there is a tendency to breastfeed for extended periods of time, sometimes up to a year or beyond (Mehrpisheh et al., 2020; Alchalel et al., 2024; Dorri et al., 2022; Arif et al., 2021).

Breastfeeding rates among Christian Arab women are lower than among Muslim women, yet, above the national average. Research has shown that the breastfeeding rate among Christian women ranges from 70% to 80% during the initial months postpartum, with a gradual decline, thereafter, similar to trends observed in other populations [

34]. Furthermore, among Druze women, breastfeeding rates are also high, reaching ~85% to 90% in the months following childbirth. Similar to their Muslim counterparts, Druze women perceive breastfeeding as having significant cultural and communal value. Nonetheless, there is a decline in breastfeeding rates associated with the adoption of modern lifestyles and economic pressures, i.e., the necessity to return to work (Alchalel et al., 2024; Dorri et al.,2022; Arif et al., 2021; Laksono et al., 2021).

Overall, breastfeeding rates are relatively high across all groups, with the highest rates observed among Druze women, followed by Muslim women, and lastly, Christian women. There is a general trend of declining breastfeeding rates over time, correlated with the increasing complexity of modern life. The relationship between poverty, women’s occupations, and EB has been extensively studied. Health-related initiatives, such as the WHO Code and the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative have addressed these factors [

35]. Analyzing economic gradient data can further clarify the impact of education and occupation on breastfeeding trends (Carandang et al., 2021).

Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine the impact of socio-demographic, occupational, and religious characteristics on the rates of EB among Israeli Arab mothers (Muslim, Christian, and Druze). We investigated how factors such as age, education, marital status, income level, and profession affect a mother’s decision to EB. Additionally, we explored the relationship between the mothers’ level of religiosity and EB rates, endeavoring to understand the contributions of these factors to the duration and/or continuation of EB and related public health policies.

The research hypotheses were:

H1: As the mother’s age increases, the likelihood of EB and its duration increases.

H2: The more previous births (i.e., children), the likelihood of EB and its duration increases.

H3: There are differences in the rate of EB and its duration based on ethnic group affiliation and geographical region.

H4: As the mother’s education level increases, the likelihood of EB and its duration increases.

H5: As the mother’s religiosity level increases, the likelihood of EB and its duration increases.

H6: There are differences in the rates of EB and its duration based on the type of breastfeeding instructional trainings/courses the mother had received.

H7: Working reduced the likelihood of both EB and its duration, further decreasing as the workload (scope) increases.

H8: An association exists between the mother’s education level and the factors which foster breastfeeding and those that lead to its cessation.

While hypotheses H1-H4 addresses aspects that have been studied to some extent in the existing literature, they remain integral to our study because they provide validation of previously observed trends among the underrepresented population of Arab mothers in Israel. Furthermore, they allow for a comparative analysis to assess whether these well-documented relationships hold within our specific sample or show unique patterns affected by religiosity, employment status, or regional factors, thus, serving as a foundation for understanding the broader interplay of factors crucial for interpreting findings from the newer hypotheses (H5-H8) and ensuring a comprehensive analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Hypotheses Testing

In order to test hypothesis H1, the assessment of age differences between: (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., complete reliance on baby food and/or supplements, EB, or integrated/combined EB and baby food) and (2) breastfeeding duration, one-way analyses of variance (one-way ANOVAs), were employed.

In assessing the association between age and breastfeeding methods (exclusive; N =165, M = 31.73, SD = 4.76/combined; N =66, M =30.00, SD = 4.92/baby food; N =43, M = 0.05, SD = 7.00), the results indicated a significant main effect: F(2, 271) = 3.60, p <.05. Hence, in order to gauge the source of these significant differences, Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were performed, revealing only that those who preferred EB were slightly older than those who opted for combined breastfeeding (p <.05). No other significant differences were discovered between these groups.

In assessing the association between age and breastfeeding duration during the last 4 months (did not breastfeed at all; N =19, M =28.95, SD = 3.52/up to 1 month; N =10, M =27.20, SD = 4.61/up to 2 months; N =6, M =27.33, SD =5.05/up to 3 months; N =25, M =32.20, SD = 8.73/up to 4 months; N =20, M =28.45, SD =5.83/above 4 months; N =194, M =31.69, SD = 4.46), the results indicated a significant main effect: F(5, 268) =4.40, p <.01. In order to gauge the source of these significant differences, Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were performed, revealing that those who breastfed for >4 months were slightly older than those who did so up to 4 months (p <.05) and up to 1 month (p <.05). No other significant differences were discovered between these groups.

In order to test hypothesis H2, the assessment of the association between the number of children prior to the recent delivery and (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., only baby food, EB, integrated/combined breastfeeding) and (2) breastfeeding duration, chi-square tests were performed. Statistically significant differences were found among the different breastfeeding methods: χ2 (6, N =274) =41.15, p <.01, rc =.27. Results indicated that: (1) those with no children before the current delivery, preferred baby food or combined breastfeeding; (2) those with 1 child did not have a specific preference; (3) those with 2 children preferred combined breastfeeding; and (4) those with 3 children preferred EB. Statistically significant differences were also found among the different breastfeeding methods: χ2 (6, N =274) =41.15, p <.01, rc =.27.

In order to test hypothesis H3, the assessment of the association between ethnic affiliation (Muslim-Arabs/Christian-Arabs/Druze) or geographic region (north, center and south of the country) and (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., only baby food, EB, integrated/combined breastfeeding) and (2) breastfeeding duration, chi-square tests, were performed.

Statistically significant differences were found among the different ethnic groups: χ2 (4, N =274) =31.93, p <.01, rc =.24. Results indicated that: (1) Muslim Arab women preferred baby food or combined breastfeeding; whereas, (2) Christian Arabs and (3) Druze both preferred EB. Statistically significant differences were found among the different ethnic groups: χ2 (10, N =274) =22.73, p <.01, rc =.20. Results indicated that: (1) Muslim Arab women preferred to breastfeed for up to 3 and 4 months; whereas (2) Christian Arabs and (3) Druze both preferred to breastfeed for >4 months. Statistically significant differences were found among the different regions: χ2 (4, N =274) =14.70, p <.01, rc =.16. Results indicated that: (1) those living in the north of the country preferred EB; (2) those living in the center preferred to use baby food; and (3) those living in the south preferred combined breastfeeding. Statistically significant differences were found among the different regions: χ2 (10, N =274) =25.36, p <.01, rc =.22. Results indicated that: (1) those living in the north of the country preferred to breastfeed for >4 months; (2) those living in the center did not have a specific preference; whereas (3) those living in the south preferred to breastfeed up to 3 and 4 months.

In order to test hypothesis H4, the assessment of the association between educational level (non-academic/academic) and (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., only baby food, EB, integrated/combined breastfeeding) and (2) breastfeeding duration, chi-square tests were performed. No statistically significant differences were found among the educational levels of the groups in relation to breastfeeding methods: χ2 (2, N =274) =4.01, p >.05, rc =.12 and no statistically significant differences were found among the educational levels of the groups in relation to breastfeeding duration: χ2 (2, N =274) =2.49, p >.05, rc =10.

In order to test hypothesis H5, the assessment of religiosity level differences between (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., only baby food, EB, integrated/combined breastfeeding) and (2) breastfeeding duration, one-way analyses of variance (one-way ANOVAs), were employed.

In gauging the association between religiosity level and breastfeeding methods (exclusive; N = 65, M =4.70, SD = 0.65/combined; N =66, M =4.37, SD =0.71/baby food; N =43, M =4.27, SD =0.97), the results indicated a significant main effect: F(2, 271) =8.70, p <.01. Hence, in order to reveal the source of these significant differences, Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were performed, finding that those who preferred EB reported higher religiosity levels than (1) those who preferred combined breastfeeding (p <.01) and (2) only baby food (p <.01). No other significant differences were discovered between these groups.

In gauging the association between religiosity level and breastfeeding duration during the last 4 months (did not breastfeed at all; N =19, M =3.97, SD =1.24/up to 1 month; N =10, M = 4.27, SD =1.05/up to 2 months; N =6, M =3.61, SD =0.83/up to 3 months; N =25, M =4.55, SD = 0.48/up to 4 months; N =20, M =4.35, SD =.90/above 4 months; N =194, M =4.67, SD =0.61), the results indicated a significant main effect: F(5, 268) =6.54, p <.01. In order to reveal the source of these significant differences, Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were performed, indicating only that those who breastfed for >4 months reported a higher religiosity level than (1) those who preferred not to breastfeed (p <.01) and (2) those who breastfed up to 2 months (p <.01). No other significant differences were discovered between these groups.

In order to test hypothesis H6, the assessment of the association between prior instruction(s) received regarding breastfeeding (did not receive any/group instructional program/personal or private instructional program) and (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., only baby food, EB, integrated/combined breastfeeding) and (2) breastfeeding duration, chi-square tests were performed. No statistically significant differences were found among the instructional groups in relation to breastfeeding methods: χ2 (4, N =274) =4.28, p >.05, rc =.09. In addition, no statistically significant differences were found among the instructional groups in relation to breastfeeding duration: χ2 (10, N =274) =7.90, p >.05, rc =.12.

In order to test hypothesis H7, the assessment of the association between employment status (unemployed/part- or full-time salaried employee/self-employed) and (1) the three different breastfeeding methods (i.e., only baby food, EB, integrated/combined breastfeeding), chi-square tests were performed. No statistically significant differences were found among the different breastfeeding methods: χ2 (4, N =274) =17.08, p <.01, rc =.18. Results indicated that: (1) those who were unemployed preferred EB; (2) those who were self-employed preferred to opt for baby food only or combined breastfeeding; and (3) salaried employees preferred combined breastfeeding. However, in testing whether these results changed under different employment/job percentage (0% or unemployed/part-time as 25% job/50%/75%/full-time with 100% employment), it was discovered that the results (previous paragraph) did not change at all based on the job scope, and stayed relatively similar across all the work percentage groups, respectively: (1) χ2 =4.57, p >.05, for the unemployed group; (2) χ2 =4.02, p >.05, for the 25% part-timers; (3) χ2 =0.49, p >.05, for the 50% part-timers; (4) χ2 =6.35, p >.05, for the 75% part-timers; and (5) χ2 =1.96, p >.05, for the full-timers.

Lastly, in order to test hypothesis H8, the assessment of the differences between educational levels (non-academic/academic) on (1) the reasons for fostering the mothers to breastfeed their infant and (2) the reasons leading them to stop breastfeeding, descriptive statistics, independent-samples t-tests and chi-square tests were performed. Notable, the 9 reasons fostering the mothers to breastfeed their infant were rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 =did not influence my decision to breastfeed my baby; 1 =somewhat influenced my decision; 2 =influenced my decision a great deal). Moreover, the 6 reasons leading to a halt in breastfeeding were calculated on a dichotomous scale (0 = was not a reason to stop breastfeeding; 1 = was a reason to stop breastfeeding). The 3-point Likert scale was chosen for its simplicity and clarity and to minimize participant confusion and response fatigue, thus, enabling clear categorization of levels of influence,

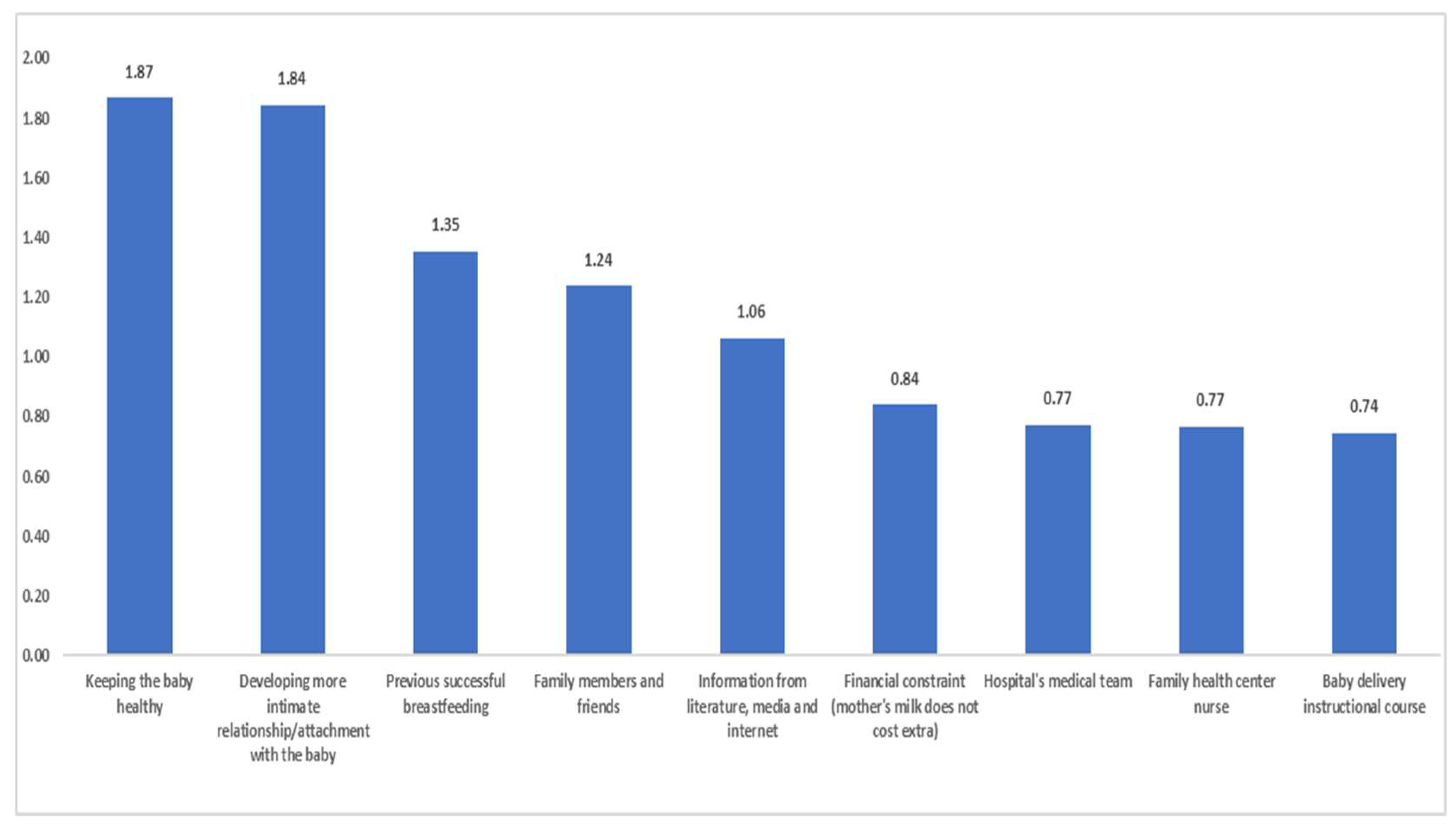

Depicted in

Figure 1 are the reasons, in a descending order, based on the mean scores, favoring breastfeeding. As can be seen, the two most prominent participant-reported reasons favoring breastfeeding were: (1) wanting to maintain the baby’s health (

M =1.87); and (2) wanting to develop a more intimate relationship/attachment with the baby (

M =1.84).

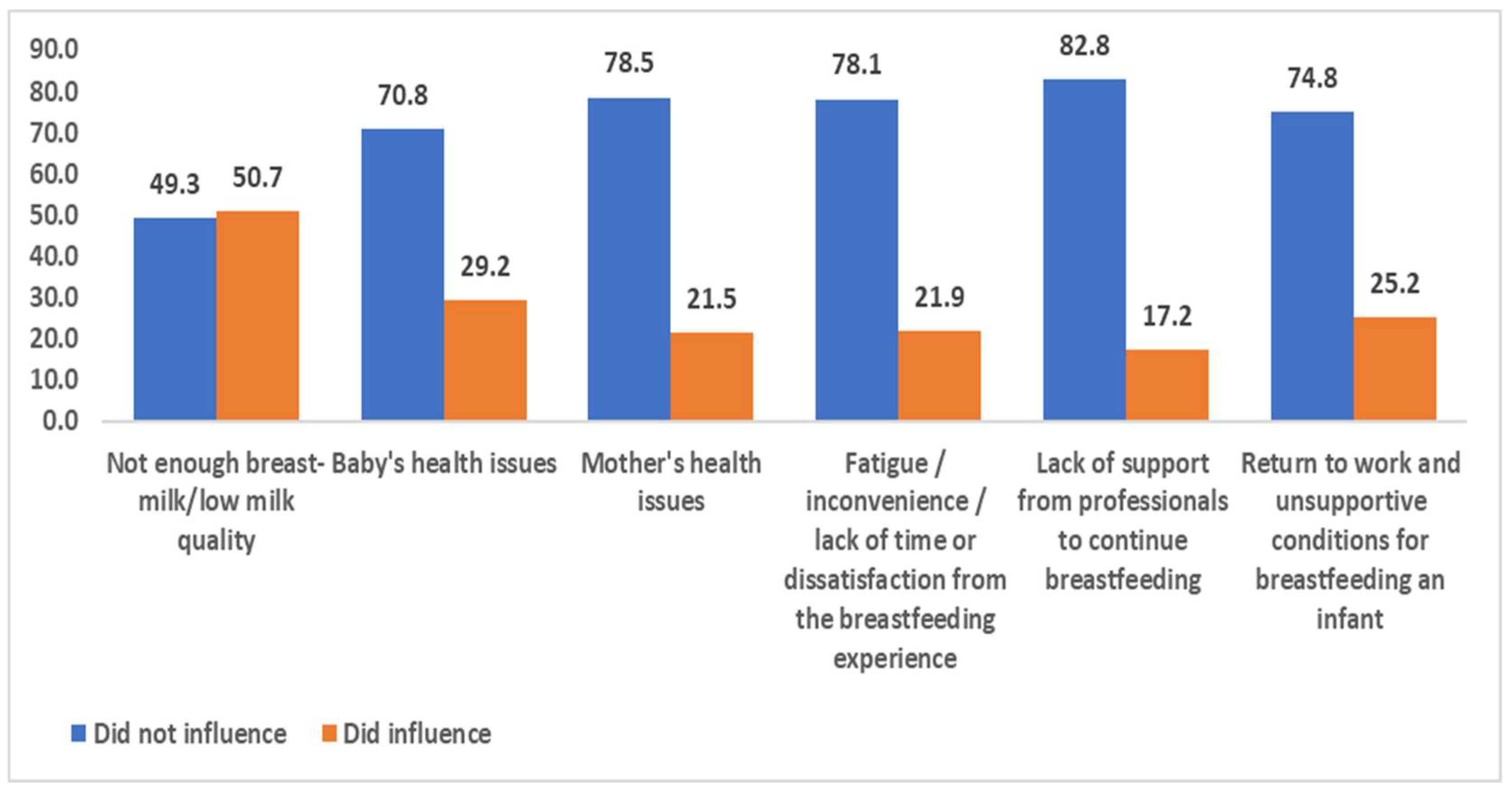

Portrayed in

Figure 2 are the participant-reported reasons leading to a halt in breastfeeding in a descending order based on relative frequencies. “Reported reasons” was used to describe the participants’ self-identified reasons for ceasing breastfeeding, as collected through the survey instrument. This phrasing reflects the subjective nature of the responses provided by the participants. As can be seen, the most prominent reported reason to halt breastfeeding was the quality of the milk/the amount of milk produced by the mother herself (50.7%).

Independent-sample

t-tests revealed several significant differences between academics and non-academics for fostering breastfeeding. The results are presented in

Table 1. As can be learned from the statistically significant effects: (1) non-academics were more influenced by their family members to breastfeed than academics; (2) academics were more influenced by instructional training programs than non-academics; (3) non-academics were more influenced by successful previous breastfeeding than academics; (4) non-academics were more influenced by financial constraints (i.e., EB does not require ‘special’ funds) than academics; and (5) academics tended to be more influenced by information obtained from the literature, internet or media.

4. Discussion

EB offers significant health benefits for both infants and mothers, applicable in both the short- and long term. Breast milk provides essential nutrition and protection against infections and diseases (Adokiya et al., 2023), containing antibodies, cytokines, and antimicrobial compounds that support the infant’s immune system and facilitate its development. Breastfeeding reduces the risk of SIDS, with the risk being even lower with EB. Furthermore, EB protectively affects the development of asthma, eczema, type 1 diabetes, and other diseases. Infants who are breastfed have a lower risk of obesity. Furthermore, studies have shown that women who breastfeed, experience lower incidence rates of breast and ovarian cancer (Lokossou et al., 2022; Gavine et al., 2022; Gianni et al., 2019).

In 2003, the WHO recommended EB for infants up to 6 months of age (Gavine et al., 2022; Gianni et al., 2019). In Israel, a survey showed that the breastfeeding initiation rate is ~90%, with all women who began breastfeeding in the hospital reporting practicing EB. However, EB rates dropped significantly during maternity leave, largely due to challenges such as milk supply issues and technical difficulties with breastfeeding (Zimmerman et al., 2022).

According to data from the 2nd National Health and Nutrition Survey, the percentage of women practicing EB at 4 to 6 months postpartum was only 28.8% (National Program for Nutrtion and Health Surveys, 2020; Ministry of Health, 2023). Following these findings, a quality indicator was established within Israel’s National Program for Quality Indicators in Well-Baby Clinics (“Tipat Chalav”), focusing on “the rate of women practicing EB up to 4 months.” Data from 2022 showed that the national rate for EB up to 4 months was 22%, whereas, the rate among Arab Israeli women was even lower, 14% (Alchalele et al., 2024). These findings highlight Arab Israeli women as a group at an increased risk for lower rates of EB. This population’s specific characteristics and challenges should be investigated to better understand and address the factors affecting EB within this demographic, in line with the quality index’s goal of improving early nutrition and breastfeeding rates across Israel.

The largest Arab population in Israel is concentrated in the Northern District, towns and villages. Arab citizens of Israel, who are primarily Muslim, Christian, and Druze, make up 21% of the overall population of Israel (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The current study emphasizes the complex effects of religious beliefs, socio-demographic factors, and cultural norms on breastfeeding patterns among Arab mothers in Israel. These findings provide insights into the key factors shaping breastfeeding behavior, including religiosity, education, age, number of children, employment, and family support.

To elaborate, one of the central findings of this study is the strong association between high levels of religiosity and longer durations of EB. This finding aligns with the religious traditions in Islam, Christianity, and Druze communities, who recommend breastfeeding and regard it as a health and spiritual obligation of the mother towards the child. The religious value attributed to breastfeeding serves as a significant motivator for its continuation, particularly, in religious communities where faith plays a central role in daily life. This finding underscores the powerful impact of religious beliefs on the health of both the mothers and infants.

As the mother’s age increases, the likelihood of EB and its duration increases. Based on the data analyzed herein, we found that the relationship between the mother’s age and breastfeeding was significant. Older mothers tended to practice EB more often and for longer periods of time than younger mothers, as evidenced by the ANOVA findings showing significant differences in breastfeeding methods and duration between the different age groups. The post hoc analysis further confirmed that mothers who practiced EB were slightly older than those who used combined feeding methods, thus suggesting that older mothers may have more experience, patience, or access to resources that encourage EB. Moreover, as the mother has had more previous births (i.e., more children), the likelihood of EB and its duration increases.

Chi-square tests revealed statistically significant differences in breastfeeding practices based on the number of children a mother had birthed before her recent delivery. Mothers with more children, particularly, those with three or more children, showed a stronger preference for EB compared to mothers with fewer or no prior children. This could be attributed to increased confidence and experience in breastfeeding as a mother has more children, as well as greater familiarity with overcoming initial breastfeeding challenges.

Furthermore, differences were found relating to the rate of EB and the duration of breastfeeding based on belonging to an ethnic group and/or geographic region. Ethnic and regional differences were observed to statistically and significantly impact both breastfeeding methods and duration. Muslim Arab mothers were more likely to combine breastfeeding with baby formula, whereas, Christian and Druze mothers favored EB. Geographically, mothers from northern Israel were more likely to practice EB compared to those from the central or southern regions. These differences most likely reflected cultural and religious practices, as well as access to breastfeeding support services that vary by region and ethnicity.

Moreover, as the educational level of the mother increased, the probability of EB and its duration increased. Contrary to expectations, the relationship between education level and breastfeeding was not as strong as hypothesized. Chi-square tests indicated no statistically significant difference between education levels and breastfeeding methods or duration. However, the effect of education may be more pronounced during the initiation phase, and less so in the continuation phase. Other factors such as family support and employment status might play a larger role in the continuation of EB over time.

Furthermore, as the mother’s level of religiosity increased, the likelihood of EB and its duration increased. The study found a significant association between higher religiosity and EB. Mothers with higher levels of religiosity were more likely to practice EB and for longer durations, thus, reflecting the religious beliefs in the Arab Muslim, Christian, and Druze communities that encourage breastfeeding as a spiritual and health-related obligation. These findings underscore the importance of integrating religious considerations into public health strategies that aim to promote breastfeeding.

However, as opposed to our hypothesis, no statistically significant differences were found as to the type of breastfeeding training mothers received and their breastfeeding methods or duration. Whereas, breastfeeding courses and training may provide initial support, they did not seem to affect long-term breastfeeding behavior in this sample, hence, suggesting that while training may help with initiation, other factors such as family support, personal experience, and cultural norms may play a more substantial role in sustaining EB.

In line with our other hypotheses, working reduced the likelihood of both EB and its duration, further decreasing as workload (volume) increased. The results indicated that employment status significantly affected breastfeeding practices. Unemployed mothers were more likely to practice EB, whereas, mothers who were employed, especially, those with full-time jobs, tended to opt for combined feeding methods. Employment-related factors such as lack of time and unsupportive workplace conditions contributed to early cessation of breastfeeding. These findings highlight the need for workplace policies that support breastfeeding, such as extended maternity leave and on-site breastfeeding facilities.

There is also the relationship between the mother’s level of education and the factors that foster breastfeeding or lead to its termination. Education level played a role in the reasons for fostering or halting breastfeeding. Non-academic mothers were more likely to be influenced by family members and financial constraints, whereas, academic mothers were more likely to be influenced by breastfeeding literature and medical advice. Academic mothers were more likely to cite fatigue, lack of time, or work-related issues as reasons for stopping breastfeeding, thus, indicating the importance of targeted interventions addressing the specific challenges faced by working mothers.

We found significant importance in familial support, particularly, the roles of grandmothers and older women within the family in encouraging breastfeeding. In the Arab society, where strong familial support networks exist, this encouragement plays a central role in preserving traditional breastfeeding patterns, thus, underscoring the importance of community intervention programs that include family members as part of the breastfeeding education process, thus, enabling a more comprehensive support system for breastfeeding.

We identified several challenges that led to the cessation of breastfeeding, including difficulties in milk supply, fatigue, and the pressure of returning to work. These challenges are particularly pronounced among mothers with lower levels of education, highlighting the need for targeted interventions to provide both practical and emotional support for continued breastfeeding.

In summary, this study has provided evidence supporting most of the hypotheses, particularly, those related to age, number of children, religiosity, and employment status. Yet, the effect of educational level and breastfeeding training on breastfeeding practices was less pronounced than expected, suggesting the need for further research and targeted interventions to promote long-term EB.

4.1. Policy Recommendations

Our findings emphasize the need to integrate religious and cultural factors into breastfeeding promotion programs within religious communities. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the religious and cultural significance of breastfeeding and provide support to mothers in alignment with their beliefs. As such, encouraging EB should commence early in the pregnancy, during hospitalization, and continue after discharge within the community. This can be achieved through resource utilization for both group and individual guidance, facilitating mother-infant proximity post-delivery, thus, empowering mothers to enhance their self-efficacy in continuing breastfeeding. Furthermore, raising awareness among mothers and their surroundings as to the benefits of maintaining EB, as well as the drawbacks of premature cessation, will aid in adopting health-promoting behaviors through breastfeeding and prevent its early discontinuation.

Collaborative efforts should be established among all members of the healthcare team (physicians, nurses, dietitians, and social workers) and workplaces to implement supportive breastfeeding processes, with the all-encompassing goal of safeguarding public health. Policies that allow for flexible work arrangements, longer maternity leave, and physical conditions that facilitate breastfeeding can ease the burden on mothers and encourage the continuation of breastfeeding.

The current research suggests that breastfeeding patterns among Arab mothers in Israel are influenced by a combination of religious beliefs, social factors, and demographic characteristics. Addressing existing challenges, particularly, in the workplace and the lack of professional support, may lead to improved breastfeeding rates and positively impact the health of both mothers and infants.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

The sampling method employed in the study utilized a snowball sampling technique; participants recruit additional participants from their personal networks. This method may introduce bias in sample selection, as the sample may not necessarily represent the broader population, but, is instead based on existing social networks. We recommend that future studies employ randomized or stratified sampling methods to ensure a more representative sample. Alternatively, combining snowball sampling with other probability-based sampling techniques could reduce bias and increase generalizability.

Geographic limitations of the sample were noted, as most participants resided in northern Israel, which could affect the generalizability of the findings to other populations in different geographic areas of the country. To mitigate such biases, the survey was distributed across all residential areas of the Arab population. Fortunately, it achieved a satisfactory representation from all segments of the population, reflecting the diversity of the Arab community in Israel in terms of origin and place of residence. We recommend that future research aim for a more geographically diverse sample, potentially including participants from different regions of Israel or outside the country. Researchers could also explore regional differences by comparing findings from northern and southern Israel to assess variations.

Since participants were asked to retrospectively report on breastfeeding after childbirth, there is a likelihood of memory bias that may affect the accuracy of the reports, particularly, regarding the duration of breastfeeding and the reasons for its cessation. We recommend that to reduce memory bias, future research could prospectively collect data, by following participants from childbirth through the breastfeeding period. Alternatively, researchers could use mixed methods, incorporating qualitative interviews to validate quantitative reports.

Furthermore, the study focused on Arab mothers in Israel, therefore, the findings may not be applicable or representative of other populations, even within Israel or in the broader global context, thereby, limiting generalizability of the findings to other populations. We recommend conducting similar studies (i.e., systematic replications) with diverse ethnic and religious groups, both within Israel and in other countries, to determine whether the findings are culturally specific or universally applicable. Cross-cultural comparisons could also be valuable.

From a cultural/religious aspect, although the study emphasized religious and cultural beliefs, we did not explore in depth the interaction between these and other factors, such as modern social norms and global effects, which may alter breastfeeding patterns in specific populations. We recommend that future research explore the dynamic relationship between traditional cultural/religious beliefs and factors, such as media, globalization, and socioeconomic factors, to understand how these affect breastfeeding practices. This can be achieved through longitudinal studies and in-depth qualitative research.