1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) plays a significant role in the pathobiology of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinomas (OPSCC) [

1]. Patients with HPV-positive exhibit distinct clinical features, including higher response rates to therapy, improved progression free survival, and better overall survival (OS) compared to their HPV-negative counterparts [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Given the more favorable prognosis of HPV-positive tumors and the substantial side effects associated with multimodal treatments, numerous clinical trials have investigated de-intensification strategies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Consequently, accurate identification of HPV status is essential for appropriate therapeutic stratification. Currently, the standard approach relies on immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of p16, a surrogate marker for HPV, as recommended by the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC) staging system [

11]. However, while p16 IHC demonstrated a high sensitivity (0.97), its specificity (0.84) remains suboptimal [

12]. To improve diagnostic accuracy, p16 is often combined with additional molecular assays such as in situ hybridization (ISH) [

13,

14]. To address these limitations, we previously developed a handcrafted machine learning pipeline that extracted single-cell morphological features from annotated images to classify HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPSCC cases. The best classifier, with an accuracy above 90%, was obtained when training on cases positive both for p16

INK4a immunostain and for HPV DNA by ISH/

INNO-LiPA® [

15]. Building on the strong performance of our feature-based machine learning approach, we sought to test whether comparable results could be achieved using a fundamentally different strategy. Specifically, we turned to weakly supervised deep learning methods, which require only slide-level annotations. Unlike fully supervised learning methods, which require detailed annotations, weakly supervised models operate only with global slide labels. We implemented the Clustering-constrained Attention Multiple Instance Learning (CLAM) [

16] framework to directly predict HPV status from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained whole slide images (WSI) of OPSCC cases. CLAM enables both classification and localization of predictive histological patterns, enhancing interpretability. In this study, we tested the feasibility of using CLAM to directly predict HPV status from H&E-stained WSIs of OPSCC cases, and we further analyzed whether high-attention regions correspond to morphologically relevant cell types using an auxiliary feature-based classifier.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

We collected H&E-stained WSI from two distinct cohorts. The first cohort is from The Cancer Genome Atlas-Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (TCGA-HNSC) and includes 10 WSIs of OPSCC. HPV status for these cases was determined using both p16

INK4a immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH), with five cases classified as HPV-positive and five as HPV-negative. The second cohort, named OPSCC-UNINA, includes 113 histological slides of OPSCC obtained from the archives of the Pathology Unit of the University "Federico II" of Naples. The HPV infection status of these specimens was determined by p16

INK4a IHC. In a subset of cases, additional molecular confirmation was available via ISH/

INNO-LiPA®. The detailed methodology for both techniques has been previously described [

15]. However, to ensure homogeneity in labeling for training the deep learning model, HPV status determined by p16 IHC was used as ground truth for all UNINA samples. Among the OPSCC-UNINA cases, 41 were HPV-positive and 72 were HPV-negative. For external validation, we used an independent set of 35 HPV-negative WSIs from UNINA, which were entirely separate from the 113 cases included in the OPSCC-UNINA training cohort. The full lists of cases analyzed in the present study are in Supplementary I.

2.2. Slide Digitization

The histological slides of the OPSCC-UNINA cohort were digitized using an Leica Aperio AT2 scanner (Leica Biosystems Imaging, California, USA) at 20x magnification. Before scanning, each slide was carefully cleaned with solvent and sterile gauze to remove any contaminants or artifacts that could compromise image quality. This ensured optimal conditions for image analysis before model training.

2.3. Computational Framework: CLAM

2.3.1. Overview

To implement a weakly supervised learning approach for whole-slide image (WSI) classification, the Clustering-constrained Attention Multiple Instance Learning (CLAM) framework[

16] was adopted. This approach allows for whole-slide predictions without the need for patch- or region-of-interest (ROI)-level annotations. We used the official implementation released by the Mahmood Lab (

https://github.com/mahmoodlab/CLAM). In preprocessing, WSIs were first subjected to tissue segmentation to exclude background areas and then subdivided into non-overlapping patches of size 256×256 pixels. Each patch was converted into a 1024-dimensional feature vector using a ResNet-50 network pre-trained on ImageNet. During training, the model evaluates and classifies all patches, assigning each an “attention score” that determines its contribution or importance to the collective slide-level representation. This representation is computed using an attention pooling rule, which combines feature vectors by weighting them according to their attention score.CLAM also includes a supervised clustering part where the patches with the highest and lowest attention scores are separated into distinct clusters. The overall loss function combines the slide-level classification loss with a patch-level clustering loss.

2.3.2. Performance Evaluation and Interpretability

Training was conducted according to a 10-fold Monte Carlo cross-validation scheme, with the dataset randomly split into 80% training, 10% validation and 10% testing for each fold, maintaining the stratification by class. Optimization was performed using the Adam algorithm with a learning rate of and an early stop criterion after 20 consecutive epochs without improvement of the validation loss, up to a maximum of 200 epochs. A batch size of 1 was used (one slide per batch) and no data augmentation techniques were applied. At the end of each fold, the model performance was evaluated in terms of accuracy (ACC) and area under the ROC curve (AUC), both on the validation and test set, using the official scripts provided by the CLAM framework. Finally, to increase the interpretability of the model, attention heatmaps were generated, highlighting the regions of the slide that most influenced the predictive decision.

2.4. Feature Evaluation

To assess whether high-attention regions reflected morphologically significant differences, we conducted a supervised cellular-level analysis on truly positive and truly negative patches identified by the CLAM model. A total of 1,230 high-attention patches were selected and analyzed using QuPath (v0.6.0-rc3) [

17]. Each patch inherited the slide-level HPV label, and cells were detected using QuPath’s cell detection module with adjusted parameters. A total of 133,125 cells were segmented and characterized by 41 morphological and staining-related features.

2.4.1. Morphological Feature-Based Classification

We trained a Random Forest classifier using the extracted features to distinguish HPV-positive from HPV-negative cells. The model, implemented in Python 3.10 using the scikit-learn library, consisted of 500 trees and default hyperparameters. The analysis was conducted following a formal approach previously described and validated by Varricchio et al. [

15]. Source code was adapted from the official scikit-learn documentation

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.ensemble.RandomForestClassifier.html (last consulted: 10/01/2024).

2.4.2. Computational Environment

All experiments were conducted on a Windows workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX A2000 GPU (12 GB VRAM), Intel(R) Xeon(R) W5-3465X CPU, and 64 GB of RAM.

3. Results

3.1. CLAM Model Performance on Internal Cross-Validation

We trained a CLAM model on a total of 123 Whole Slide Images (WSIs) from two cohorts: OPSCC-UNINA (n=113) and TCGA (n=10). In the 10-fold cross-validation setting, the CLAM model showed moderate performance with substantial variability across folds (

Table 1). The average test area under the curve (AUC) was 0.5324, and the corresponding test accuracy was 56.5%, whereas validation performance was consistently higher, with an average AUC of 0.7178 and accuracy of 78.2%. Notably, Fold 6 achieved a perfect test AUC of 1.0 and the highest test accuracy of 80.0%, suggesting optimal class separation within that subset (

Table 1).

3.2. Global Classification and Probability Analysis

For each WSI, the model outputs both the predicted class and the associated probabilities for HPV-positive and HPV-negative labels. Overall, 78.9% of WSIs were correctly classified (

Table 2), with the majority showing high confidence. However, about 21% of the WSIs (26 out of 123, of which 23 from the OPSCC-UNINA dataset and 3 from TCGA) were misclassified. (Supplementary II)

Among the 21% of misclassified WSIs (26 of 123), several recurring patterns were identified. In four WSIs, the model prediction probabilities were close to the classification threshold, suggesting uncertainty in the decision-making process. These borderline cases often showed nearly equal probabilities for both HPV-positive and HPV-negative classes (e.g., 0.512 vs. 0.487). In four other WSIs, model predictions were discordant with IHC-based labels but concordant with INNO-lipa results. Some samples labeled as HPV-positive by IHC but negative by INNO-lipa were also predicted as negative by the model. This observation suggests that p16 IHC, while commonly used as a surrogate marker, may occasionally lead to false-positive classifications. These findings emphasize the added value of computational models in flagging cases that are ambiguous or potentially misclassified when relying on a single biomarker. Six additional WSIs had significant artifacts, such as tissue folds, tears, or glass markers, which likely impaired the model’s ability to extract relevant histological features. Notably, all three misclassified slides from the TCGA cohort fell into this category, indicating a potential link between technical quality and misclassification.

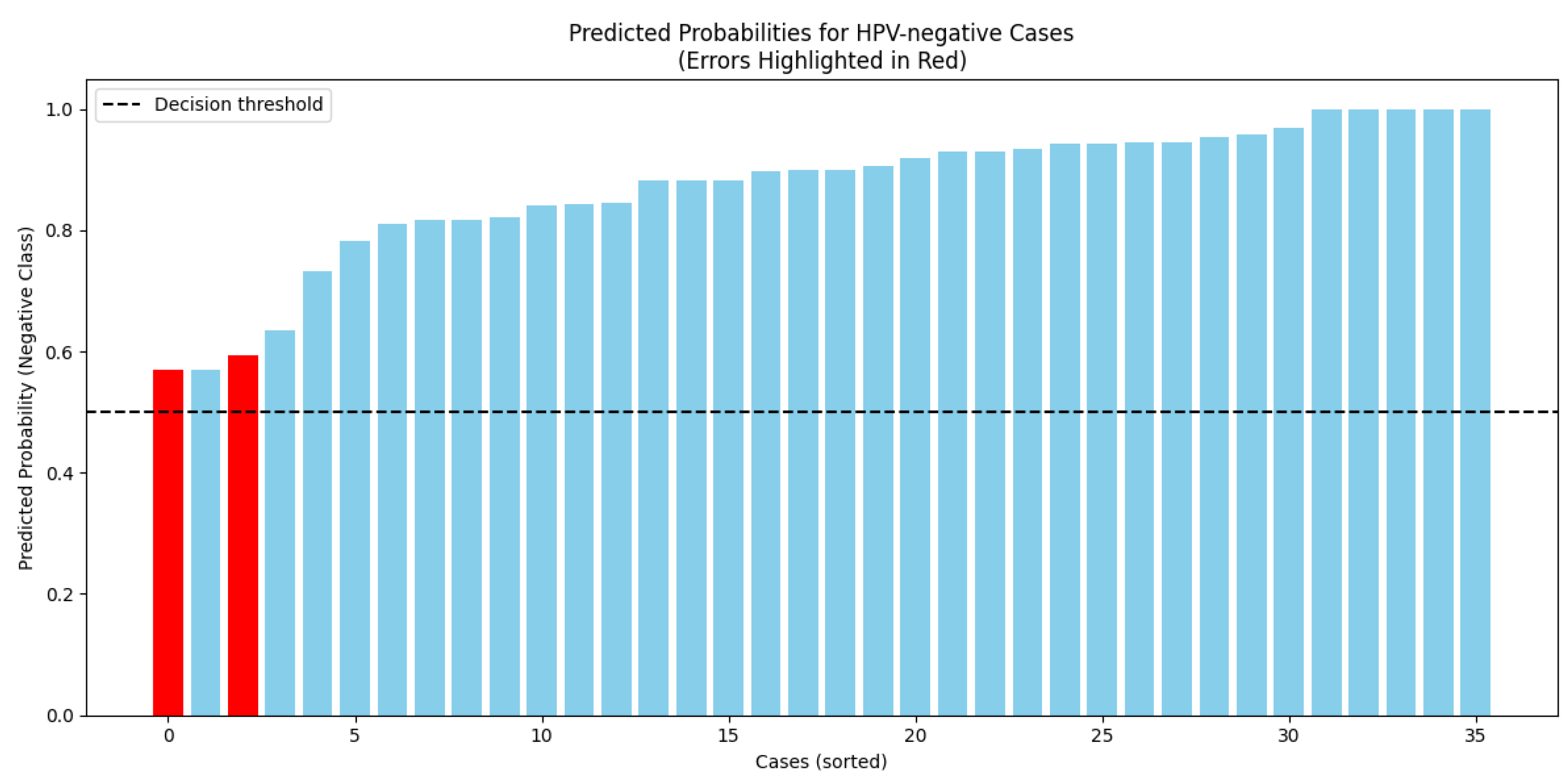

3.3. External Test Set Performance

The trained model was evaluated on an independent test set of 35 HPV-negative WSIs. The model correctly classified 33 out of 35 cases, yielding an accuracy of 94.3%. Most correctly classified slides had strong negative probabilities (80–90%). The two misclassified slides were predicted as HPV-positive with probabilities of 0.593 and 0.570, both of which are close to the classification threshold. One of these slides contained a large air bubble, likely compromising the feature extraction process. (Supplementary III)

Figure 1.

Histogram of predicted probabilities for HPV-negative class (correct: blue, incorrect: red).

Figure 1.

Histogram of predicted probabilities for HPV-negative class (correct: blue, incorrect: red).

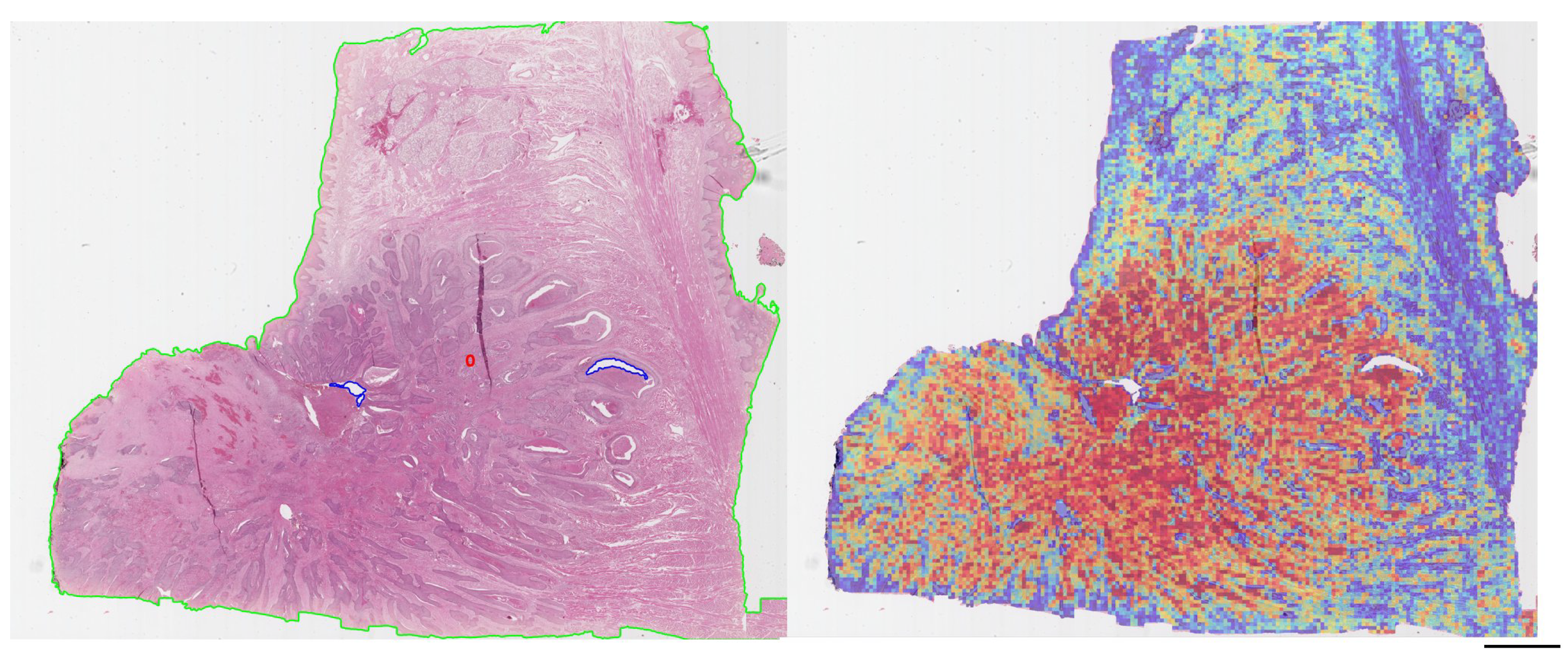

3.4. Interpretability Through Attention Maps

Analysis of the attention heatmaps revealed that the model consistently focused on tumor-rich regions, particularly in correctly classified cases (

Figure 2 ). This behavior was observed across both training and external datasets, supporting the hypothesis that the model learns biologically relevant features for HPV status classification.

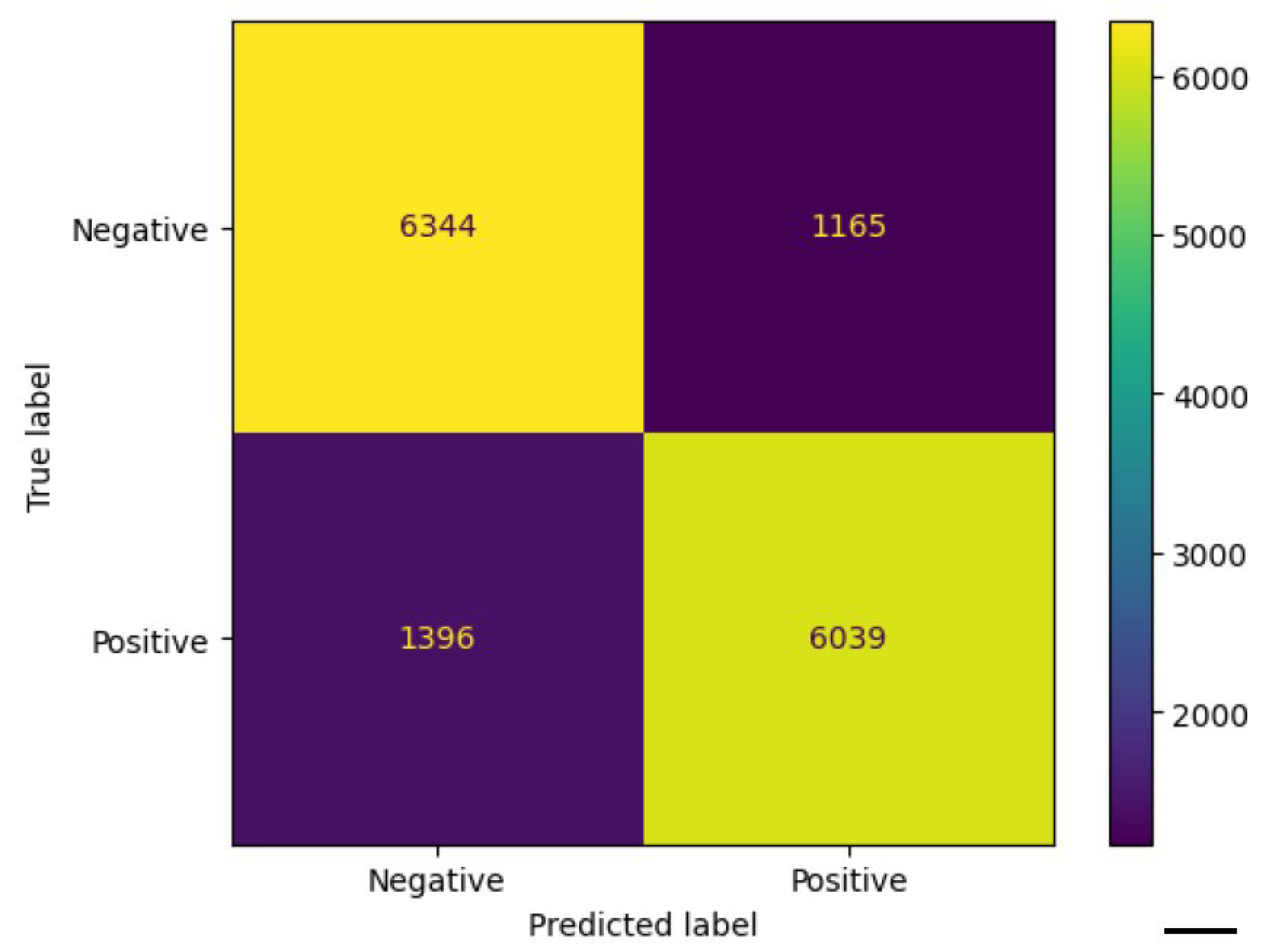

3.5. Cell-Level Analysis

To evaluate the ability of morphological features to discriminate between HPV-positive and HPV-negative cells. The cells were segmented using QuPath v0.6.0 and described by 41 morphological and staining-related features. We trained a Random Forest classifier on a balanced dataset of 74,718 cells (37,359 per class), each labeled according to the patch from which it was extracted. The model achieved an overall accuracy of

82.9%, with a precision of

84%, recall of

81%, and F1-score of

0.83 for the HPV-positive class, as summarized in

Table 3. Classification performance was consistent across both classes, confirming the presence of robust morphometric signals differentiating HPV-related tumors. The confusion matrix shown in

Figure 3 further confirms the balanced performance of the classifier, with comparable accuracy in both HPV-positive and HPV-negative classes.

4. Discussion

Predicting HPV status directly from H&E-stained slides using deep learning represents a promising and innovative frontier in computational pathology. Building on our previous work with handcrafted morphological features, which demonstrated high accuracy in distinguishing HPV-positive from HPV-negative OPSCC and highlighted the complementary nature of p16 IHC and molecular testing, we sought to explore a more scalable, annotation-free approach. In this study, we employed the CLAM framework, a weakly supervised deep learning model, to classify HPV status using only slide-level labels. The model achieved an overall classification accuracy of 78.9% on the internal dataset and performed strongly on an independent test set, reaching 94.3% accuracy. These findings confirm the feasibility of extracting biologically relevant features from routine H&E slides without manual region-of-interest annotation. Despite these encouraging results, performance during cross-validation was variable (mean AUC: 0.5324), with one fold achieving perfect discrimination (AUC = 1.0; accuracy = 80%). This variability may reflect cohort heterogeneity, differences in image quality, or noise in the ground truth labels. Notably, our primary labeling method relied on p16 IHC, which, while highly sensitive, is limited by reduced specificity. This limitation likely contributed to label noise, particularly in cases where p16 was positive but not corroborated by molecular testing.

Recent studies, such as Klein et al. (AUC = 0.80) [

18], Wang et al. (AUC = 0.8371) [

19], and Adachi et al. (AUC = 0.905) [

20], performed better.

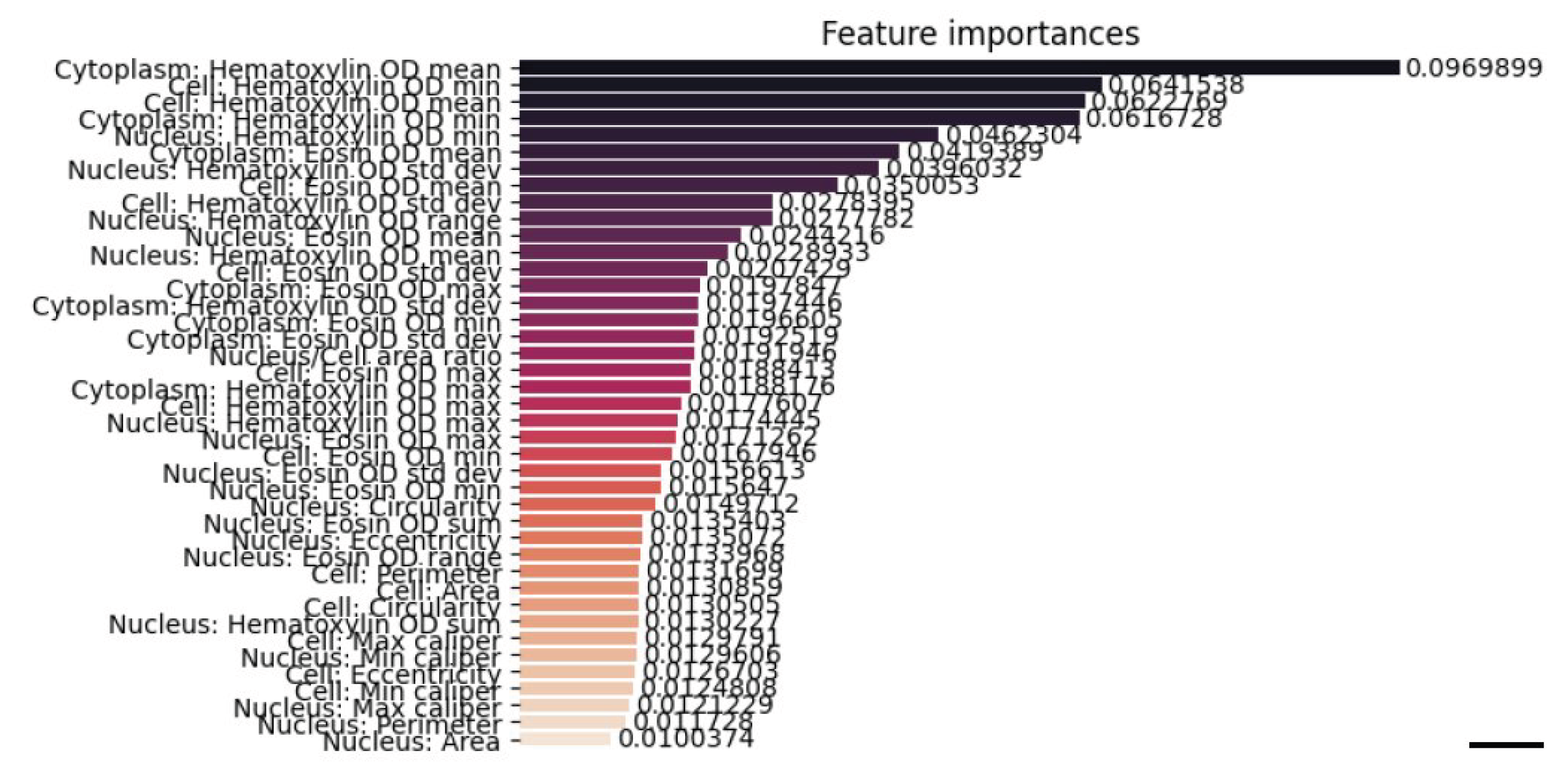

Indeed, in four misclassified cases, model predictions were discordant with p16 status but aligned with INNO-LiPA results, suggesting that the model may detect histological cues more closely associated with actual HPV infection. Such findings reinforce the notion that computational models can serve as a second opinion or flag potentially misclassified cases when relying solely on p16. Technical artifacts also contributed to misclassification. Slides with tissue folds, air bubbles, or annotation markers tended to impair model performance, underscoring the need for quality control as an integral component of digital pathology workflows. To enhance model interpretability, attention heatmaps were generated. These consistently localized to tumor-rich areas across datasets, supporting the hypothesis that the model was learning biologically meaningful features. To further investigate the nature of these regions, we extracted 1,230 high-attention patches and performed supervised cell-level morphological analysis using QuPath. Over 133,000 cells were segmented and described with 41 quantitative features. A Random Forest classifier trained on these features achieved an accuracy of 82.9%, with balanced precision and recall across HPV-positive and -negative classes. These results confirm the presence of robust, class-distinguishing morphometric signals at the cellular level. Feature importance analysis revealed that the most influential variables were colorimetric, particularly haematoxylin optical density metrics associated with nuclear morphology and chromatin texture (

Figure 4). Remarkably, these same features emerged as top contributors in our prior feature-based machine learning model, which was trained on manually annotated cells, suggesting strong biological consistency between traditional and deep learning approaches [

15]. Overall, our findings support the potential of weakly supervised deep learning to deliver both accurate and interpretable predictions of HPV status in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). The reproducibility of key morphometric features, alignment with molecular results in ambiguous cases, and localization of model attention to biologically plausible regions are all hallmarks of a robust pipeline. For clinical adoption, however, seamless integration into laboratory workflows remains essential. The recent framework proposed by Angeloni et al. [

21], which enables HL7-based communication between AI systems and laboratory information systems (LIS), represents a critical step toward deployment. Equally important is the integration of predictive outputs — such as heatmaps or confidence scores — into widely used platforms like QuPath to support daily diagnostic utility. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that weakly supervised deep learning can accurately and interpretably predict HPV status from H&E slides. By combining attention-based models with morphometric validation, we provide a scalable framework that complements current diagnostic standards, reduces dependence on molecular assays, and supports personalized treatment strategies for HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Table S1: Summary of patient characteristics and biomarker results across datasets; Table S2: Case-level predictions and discordant results from CLAM and Random Forest models; Figure S1: Representative CLAM attention heatmaps for HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPSCC cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: FM; Methodology: FM, GI, SV, AM, DC; Software: AC, FM; formal analysis: FM, AC, GI; writing original draft: AC, FM, GI; writing review and editing: SS, RMDC, DR; funding acquisition: SS, FM; GI. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Rare cancers of the head and neck: a comprehensive approach combining genomic, immunophenotypic and computational aspects to improve patient prognosis and establish innovative preclinical models – RENASCENCE “ (project code PNRR-TR1-2023-12377661)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and in agreement with Italian law for studies based only on retrospective analyses on routine archival FFPE tissue. A written informed consent from the living patient, following the indication of Italian Legislative Decree No. 196/03 (Codex on Privacy), as modified by EU Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and Commission, was obtained at the time of surgery.

Acknowledgments

Google Gemini 1.5 Pro was used by the authors to revise or translate the text, enhancing the grammar and English language of this work. The authors then critically reviewed and revised the output, ensuring full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACC |

Accuracy |

| AJCC |

American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| AUC |

Area under the ROC curve |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| CLAM |

Clustering-constrained Attention Multiple Instance Learning |

| DL |

Deep learning |

| FFPE |

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HPV |

Human papillomavirus |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| ISH |

In situ hybridization |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| OPSCC |

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| TCGA |

The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| WSI |

Whole-slide image |

References

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, K.K.; Harris, J.; Wheeler, R.; Weber, R.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Nguyen-Tân, P.F.; Westra, W.H.; Chung, C.H.; Jordan, R.C.; Lu, C.; et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhry, C.; Westra, W.H.; Li, S.; Cmelak, A.; Ridge, J.A.; Pinto, H.; Forastiere, A.; Gillison, M.L. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus–positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2008, 100, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischin, D.; Young, R.J.; Fisher, R.; Fox, S.B.; Le, Q.T.; Peters, L.J.; Solomon, B.; Choi, J.; O’Sullivan, B.; Kenny, L.M.; et al. Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III trial. Journal of clinical oncology 2010, 28, 4142–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, M.; Lorch, J.; Goloubeva, O.; Tan, M.; Schumaker, L.; Sarlis, N.; Haddad, R.; Cullen, K. Survival and human papillomavirus in oropharynx cancer in TAX 324: a subset analysis from an international phase III trial. Annals of oncology 2011, 22, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri, F.; Longo, F.; Caponigro, F.; Sandomenico, F.; Guida, A.; Della Vittoria Scarpati, G.; Ottaiano, A.; Muto, P.; Ionna, F. Management of HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: pitfalls and caveat. Cancers 2020, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.J.; Vokes, E.E. Optimizing treatment de-escalation in head and neck cancer: current and future perspectives. The oncologist 2021, 26, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cmelak, A.; Li, S.; Marur, S.; Zhao, W.; Westra, W.H.; Chung, C.H.; Gillison, M.L.; Gilbert, J.; Bauman, J.E.; Wagner, L.I.; et al. E1308: Reduced-dose IMRT in human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated resectable oropharyngeal squamous carcinomas (OPSCC) after clinical complete response (cCR) to induction chemotherapy (IC)., 2014.

- Chera, B.S.; Amdur, R.J.; Tepper, J.E.; Tan, X.; Weiss, J.; Grilley-Olson, J.E.; Hayes, D.N.; Zanation, A.; Hackman, T.G.; Patel, S.; et al. Mature results of a prospective study of deintensified chemoradiotherapy for low-risk human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2018, 124, 2347–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yom, S.; Harris, J.; Caudell, J.; Geiger, J.; Waldron, J.; Gillison, M.; Subramaniam, R.; Yao, M.; Xiao, C.; Kovalchuk, N.; et al. Interim futility results of NRG-HN005, A randomized, phase II/III non-inferiority trial for non-smoking p16+ oropharyngeal cancer patients. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 2024, 120, S2–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.G.; Anderson, L.A.; Schache, A.G.; Moran, M.; Graham, L.; Currie, K.; Rooney, K.; Robinson, M.; Upile, N.S.; Brooker, R.; et al. Recommendations for determining HPV status in patients with oropharyngeal cancers under TNM8 guidelines: a two-tier approach. British Journal of Cancer 2019, 120, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, R.C.; Lingen, M.W.; Perez-Ordonez, B.; He, X.; Pickard, R.; Koluder, M.; Jiang, B.; Wakely, P.; Xiao, W.; Gillison, M.L. Validation of methods for oropharyngeal cancer HPV status determination in US cooperative group trials. The American journal of surgical pathology 2012, 36, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhi, A.D.; Westra, W.H. Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer 2010, 116, 2166–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, W.; Wang, B.; Wei, J.; Ji, R.; Xin, Y.; Dong, L.; Jiang, X. Feasibility of immunohistochemical p16 staining in the diagnosis of human papillomavirus infection in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 10, 524928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varricchio, S.; Ilardi, G.; Crispino, A.; D’Angelo, M.P.; Russo, D.; Di Crescenzo, R.M.; Staibano, S.; Merolla, F. A machine learning approach to predict HPV positivity of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Pathologica-Journal of the Italian Society of Anatomic Pathology and Diagnostic Cytopathology 2024, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.Y.; Williamson, D.F.; Chen, T.Y.; Chen, R.J.; Barbieri, M.; Mahmood, F. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images. Nature biomedical engineering 2021, 5, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.; Wuerdemann, N.; Demers, I.; Kopp, C.; Quantius, J.; Charpentier, A.; Tolkach, Y.; Brinker, K.; Sharma, S.J.; George, J.; et al. Predicting HPV association using deep learning and regular H&E stains allows granular stratification of oropharyngeal cancer patients. npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Khurram, S.A.; Walsh, H.; Young, L.S.; Rajpoot, N. A novel deep learning algorithm for human papillomavirus infection prediction in head and neck cancers using routine histology images. Modern Pathology 2023, 36, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, M.; Taki, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Kojima, M.; Hirao, A.; Matsuura, K.; Hayashi, R.; Tabuchi, K.; Ishikawa, S.; Ishii, G.; et al. Extracting interpretable features for pathologists using weakly supervised learning to predict p16 expression in oropharyngeal cancer. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeloni, M.; Rizzi, D.; Schoen, S.; Caputo, A.; Merolla, F.; Hartmann, A.; Ferrazzi, F.; Fraggetta, F. Closing the gap in the clinical adoption of computational pathology: a standardized, open-source framework to integrate deep-learning models into the laboratory information system. Genome Medicine 2025, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).