Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Epidemiology and Clinical Burden

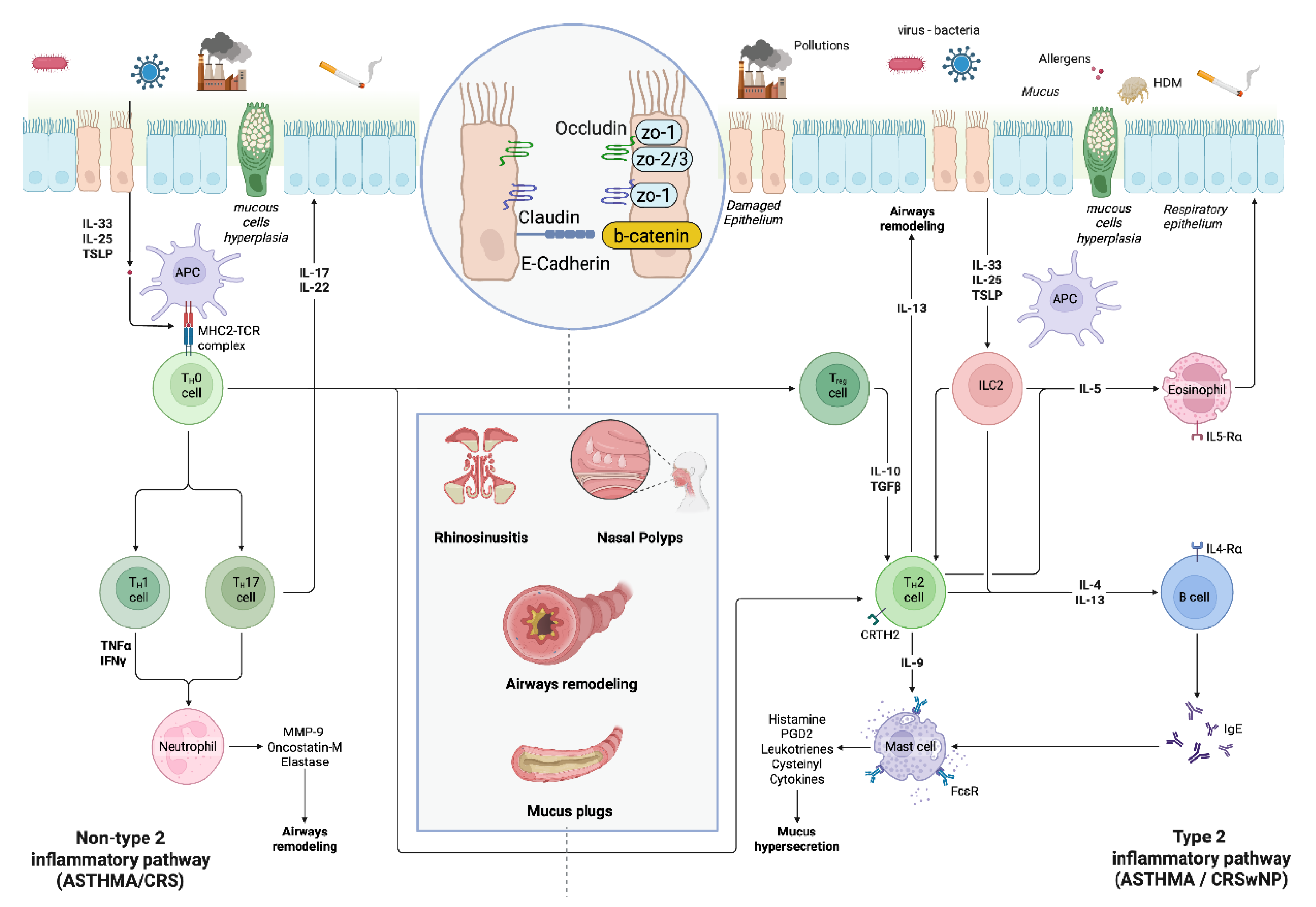

3. Mechanisms, Endotypes and Phenotypes

4. Diagnostics tools

- Imaging:

- b. Allergy and Laboratory Tests:

- c. Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT):

- d. Biomarkers:

- e. Histopathology:

5. Management Strategies

6. Multidisciplinary Care:

7. Pharmacotherapy:

- Intranasal Corticosteroids and Associations with Antihistamines:

- b. Inhaled Corticosteroids:

- c. Antimuscarinics (LAMA)

- d. Oral Corticosteroids:

- e. Antibiotics:

- f. Biologic Therapies:

- g. Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy:

- h. New Targeted Therapies:

- i.

- Surgical Interventions:

- j. Non-Pharmacologic Measures:

8. Precision Medicine and Treatable Traits

9. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Abbreviations

| ABPA | Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis |

| ACCESS | Amsterdam Classification of Completeness of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery |

| ACQ-6 | Asthma Control Questionnaire-6 |

| AERD | Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease |

| AIT | Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy |

| AR | Allergic Rhinitis |

| BAT | Basophil Activation Test |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRD | Component Resolved Diagnosis |

| CRSsNP | Chronic Rhinosinusitis without Nasal Polyps |

| CRSwNP | Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| EBC | Exhaled Breath Condensate |

| EGPA | Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis |

| Eos | Eosinophils |

| EPOS/EUFOREA | European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps / European Forum for Research and Education in Allergy and Airway Diseases |

| ESS | Endoscopic Sinus Surgery |

| FEF25-75% | Forced Expiratory Flow at 25–75% of Vital Capacity |

| FeNO | Fractional exhaled Nitric Oxide |

| FEV1% | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (percentuale del predetto) |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| GINA | Global Initiative for Asthma |

| ICS | Inhaled Corticosteroids |

| IgE | Immunoglobulins E |

| IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 | Interleukin-4, Interleukin-5, Interleukin-13 (citokines) |

| IL-4R | Interleukin-4 Receptor |

| IL-4Rα | Interleukin-4 Receptor alpha |

| IL-5R | Interleukin-5 Receptor |

| ILC2s | Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells |

| INCS | Intranasal Corticosteroids |

| IOS | Impulse Oscillometry (o Spirometria con Tecnica di Oscillazione) |

| JAK | Janus Kinase (inibitori) |

| LABA | Long-Acting Beta Agonist |

| LAMA | Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonist |

| LMS | Lund-Mackay Score |

| MART | Maintenance and Reliever Therapy |

| MAT | Mast Cell Activation Test |

| MDI | Metered-Dose Inhaler |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OCS | Oral Corticosteroids |

| OSA | Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome |

| PFT | Pulmonary Function Testing |

| PROs | Patient-Reported Outcomes |

| SNOT-22 | Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (score) |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| T2 | Type 2 (Inflammation) |

| Th2 | T helper type 2 (cells) |

| TSLP | Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (citokine) |

| TT | Treatable Traits |

| UAD | United Airway Disease |

References

- Domínguez-Ortega, J.; Mullol, J.; Álvarez Gutiérrez, F.J.; Miguel-Blanco, C.; Castillo, J.A.; Olaguibel, J.M.; Blanco-Aparicio, M. The Effect of Biologics in Lung Function and Quality of Life of Patients with United Airways Disease: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: Global 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiotiu, A.; Novakova, P.; Baiardini, I.; Bikov, A.; Chong-Neto, H.; de-Sousa, J.C.; Emelyanov, A.; Heffler, E.; Fogelbach, G.G.; Kowal, K.; et al. Manifesto on United Airways Diseases (UAD): An Interasma (Global Asthma Association - GAA) Document. J Asthma 2022, 59, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yii, A.C.A.; Tay, T.R.; Choo, X.N.; Koh, M.S.Y.; Tee, A.K.H.; Wang, D.Y. Precision Medicine in United Airways Disease: A “Treatable Traits” Approach. Allergy 2018, 73, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkens, W.; Reitsma, S. Unified Airway Disease: A Contemporary Review and Introduction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2023, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Luong, A.U.; Gevaert, P.; Mullol, J.; Smith, S.G.; Silver, J.; Sousa, A.R.; Howarth, P.H.; Benson, V.S.; Mayer, B.; et al. The Unified Airway Hypothesis: Evidence From Specific Intervention With Anti-IL-5 Biologic Therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023, 11, 2630–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, T.M.; Mullol, J.; Woessner, K.M.; Amin, N.; Mannent, L.P. Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps and Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021, 9, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Liao, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.Y. Role of IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP in Triggering United Airway Diseases toward Type 2 Inflammation. Allergy 2020, 75, 2794–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachert, C.; Luong, A.U.; Gevaert, P.; Mullol, J.; Smith, S.G.; Silver, J.; Sousa, A.R.; Howarth, P.H.; Benson, V.S.; Mayer, B.; et al. The Unified Airway Hypothesis: Evidence From Specific Intervention With Anti–IL-5 Biologic Therapy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2023, 11, 2630–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, T.; Takemura, M.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Yokota, M.; Fukumitsu, K.; Takeda, N.; Ichikawa, H.; Hijikata, H.; Uemura, T.; Takakuwa, O.; et al. Combined Measurements of Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide and Nasal Nitric Oxide Levels for Assessing Upper Airway Diseases in Asthmatic Patients. Journal of Asthma 2018, 55, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yii, A.C.A.; Tay, T.R.; Choo, X.N.; Koh, M.S.Y.; Tee, A.K.H.; Wang, D.Y. Precision Medicine in United Airways Disease: A “Treatable Traits” Approach. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2018, 73, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relationship of Upper Airways Disorders to FEV1 and Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness in an Epidemiological Study - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1426221/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Giombi, F.; Pace, G.M.; Pirola, F.; Cerasuolo, M.; Ferreli, F.; Mercante, G.; Spriano, G.; Canonica, G.W.; Heffler, E.; Ferri, S.; et al. Airways Type-2 Related Disorders: Multiorgan, Systemic or Syndemic Disease? Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullol, J.; Maldonado, M.; Castillo, J.A.; Miguel-Blanco, C.; Dávila, I.; Domínguez-Ortega, J.; Blanco-Aparicio, M. Management of United Airway Disease Focused on Patients With Asthma and Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps: A Systematic Review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022, 10, 2438–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.P.; Wise, S.K. Unified Airway Disease: Examining Prevalence and Treatment of Upper Airway Eosinophilic Disease with Comorbid Asthma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2023, 56, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.H.; Callejas-Díaz, B.; Mullol, J. MicroRNA in United Airway Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteinberg, M.; Nassrallah, N.; Jrbashyan, J.; Uri, N.; Stein, N.; Adir, Y. Upper Airway Involvement in Bronchiectasis Is Marked by Early Onset and Allergic Features. ERJ Open Res 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverino, E.; Dimakou, K.; Hurst, J.; Martinez-Garcia, M.A.; Miravitlles, M.; Paggiaro, P.; Shteinberg, M.; Aliberti, S.; Chalmers, J.D. The Overlap between Bronchiectasis and Chronic Airway Diseases: State of the Art and Future Directions. Eur Respir J 2018, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Cai, Q.; Hu, S.; Zhu, R.; Wang, J. Causal Associations between Pediatric Asthma and United Airways Disease: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, G.; Min, C.; Park, B.; Choi, H.G.; Mo, J.H. Bidirectional Association between Asthma and Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Two Longitudinal Follow-up Studies Using a National Sample Cohort. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.; Bunyavanich, S. Allergic Rhinitis: The “Ghost Diagnosis” in Patients with Asthma. Asthma Res Pract 2015, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.H.; Miller, M.D.; Simon, R.A. The United Allergic Airway: Connections between Allergic Rhinitis, Asthma, and Chronic Sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2012, 26, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passalacqua, G.; Ciprandi, G.; Canonica, G.W. The Nose-Lung Interaction in Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma: United Airways Disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2001, 1, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Vivolo Aun, M.; Takejima, P.; Kalil, J.; Agondi, R.C. United Airway Disease: Current Perspectives. J Asthma Allergy 2016, 9, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, C.; Canevari, R.F.; Bagnasco, D.; Bilò, M.B.; Canonica, G.W.; Caruso, C.; Castelnuovo, P.; Cecchi, L.; Calcinoni, O.; Carone, M.; et al. ARIA-Italy Multidisciplinary Consensus on Nasal Polyposis and Biological Treatments: Update 2025. World Allergy Organ J 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.A. Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma: Epidemiology and Common Pathophysiology. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014, 35, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, G.; Canonica, G.W. Treating the Allergic Patient: Think Globally, Treat Globally. Allergy 2002, 57, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naydenova, K.; Dimitrov, V.; Velikova, T. Immunological and MicroRNA Features of Allergic Rhinitis in the Context of United Airway Disease. Sinusitis 2021, Vol. 5, Pages 45-52 2021, 5, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, M.Z.; Sun, D.; Rawlins, E.L. Human Lung Development: Recent Progress and New Challenges. Development (Cambridge) 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yin, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, J.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X. Advances in Co-Pathogenesis of the United Airway Diseases. Respir Med 2024, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Asako, M.; Tomoda, K.; Kawauchi, H.; Iwai, H. Regulation of Interaction between the Upper and Lower Airways in United Airway Disease. Med Sci (Basel) 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klain, A.; Indolfi, C.; Dinardo, G.; Licari, A.; Cardinale, F.; Caffarelli, C.; Manti, S.; Ricci, G.; Pingitore, G.; Tosca, M.; et al. United Airway Disease. Acta Bio Medica : Atenei Parmensis 2021, 92, e2021526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Liao, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.Y. Role of IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP in Triggering United Airway Diseases toward Type 2 Inflammation. Allergy 2020, 75, 2794–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, J.; Adir, Y.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Celis-Preciado, C.A.; Colodenco, F.D.; Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Lababidi, H.; Ledanois, O.; Mahoub, B.; Perng, D.W.; et al. Type 2 Inflammation in Asthma and Other Airway Diseases. ERJ Open Res 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furue, M.; Ulzii, D.; Vu, Y.H.; Tsuji, G.; Kido-Nakahara, M.; Nakahara, T. Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis: Current Paradigm. Iran J Immunol 2019, 16, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, A.; Lal, D.; Divekar, R.D. Unified Airway Disease: Diagnosis and Subtyping. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2023, 56, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamil, E.; Hopkins, C. Unified Airway Disease: Medical Management. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2023, 56, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, J.G.; Marino, M.J.; Luong, A.U. Unified Airway Disease: Future Directions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2023, 56, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.W.Q.; Sim, W.L.; Cheong, J.K.; Kuan, W. Sen; Tran, T.; Lim, H.F. MicroRNAs in Chronic Airway Diseases: Clinical Correlation and Translational Applications. Pharmacol Res 2020, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.H.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2019, 56, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardolo, F.L.M.; Sprio, A.E.; Baroso, A.; Gallo, F.; Riccardi, E.; Bertolini, F.; Carriero, V.; Arrigo, E.; Ciprandi, G. Characterization of T2-Low and T2-High Asthma Phenotypes in Real-Life. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, L.G.; Perez de Llano, L.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Backer, V.; Busby, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Christoff, G.C.; Cosio, B.G.; FitzGerald, J.M.; Heffler, E.; et al. Eosinophilic and Noneosinophilic Asthma: An Expert Consensus Framework to Characterize Phenotypes in a Global Real-Life Severe Asthma Cohort. Chest 2021, 160, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.F.; Dixey, P.; Abubakar-Waziri, H.; Bhavsar, P.; Patel, P.H.; Guo, S.; Ji, Y. Characteristics, Phenotypes, Mechanisms and Management of Severe Asthma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022, 135, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agache, I. Severe Asthma Phenotypes and Endotypes. Semin Immunol 2019, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Chupp, G. Phenotypes and Endotypes of Adult Asthma: Moving toward Precision Medicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 144, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Greve, G.; Hellings, P.W.; Fokkens, W.J.; Pugin, B.; Steelant, B.; Seys, S.F. Endotype-Driven Treatment in Chronic Upper Airway Diseases. Clin Transl Allergy 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Gu, M.; Zhang, X.; Wen, M.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, R.; Xiao, X. Diagnostic Value of Upper Airway Morphological Data Based on CT Volume Scanning Combined with Clinical Indexes in Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, M.; Bagnasco, D.; Canevari, F.R.M. Should Computed Tomography Be Used in the Evaluation of Biologic Therapies for Severe Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps? Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2025, 45, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, V.J.; Kennedy, D.W. Staging for Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinreich, S.J. Imaging for Staging of Rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2004, 193, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adapinar, B.; Kurt, E.; Kebapçi, M.; Erginel, M.S. Computed Tomography Evaluation of Paranasal Sinuses in Asthma: Is There a Tendency of Particular Site Involvement? Allergy Asthma Proc 2006, 27, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansotegui, I.J.; Melioli, G.; Canonica, G.W.; Caraballo, L.; Villa, E.; Ebisawa, M.; Passalacqua, G.; Savi, E.; Ebo, D.; Gómez, R.M.; et al. IgE Allergy Diagnostics and Other Relevant Tests in Allergy, a World Allergy Organization Position Paper. World Allergy Organ J 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, T.F.; Berdnikovs, S.; Simon, H.U.; Bochner, B.S.; Rosenwasser, L.J. Eosinophilic Bioactivities in Severe Asthma. World Allergy Organ J 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodig, S.; Čepelak, I. The Potential of Component-Resolved Diagnosis in Laboratory Diagnostics of Allergy. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmings, O.; Kwok, M.; McKendry, R.; Santos, A.F. Basophil Activation Test: Old and New Applications in Allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri, R.; Custovic, A.; Korosec, P.; Tsoumani, M.; Barron, M.; Wu, J.; Sayers, R.; Weimann, A.; Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Patel, N.; et al. Mast Cell Activation Test in the Diagnosis of Allergic Disease and Anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 142, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottini, M.; Bondi, B.; Bagnasco, D.; Braido, F.; Passalacqua, G.; Licini, A.; Lombardi, C.; Berti, A.; Comberiati, P.; Landi, M.; et al. Impulse Oscillometry Defined Small Airway Dysfunction in Asthmatic Patients with Normal Spirometry: Prevalence, Clinical Associations, and Impact on Asthma Control. Respir Med 2023, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonica, G.W.; Blasi, F.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Guida, G.; Heffler, E.; Paggiaro, P. Journal Pre-Proof SANI Definition of Clinical Remission in Severe Asthma: A Delphi Consensus. I: In Practice The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A.; Sordillo, J.E.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Chung, W.; Liang, L.; Coull, B.A.; Hivert, M.F.; Lai, P.S.; Forno, E.; Celedón, J.C.; et al. The Nasal Methylome as a Biomarker of Asthma and Airway Inflammation in Children. Nat Commun 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, G.; Bagnasco, D.; Carriero, V.; Bertolini, F.; Ricciardolo, F.L.M.; Nicola, S.; Brussino, L.; Nappi, E.; Paoletti, G.; Canonica, G.W.; et al. Critical Evaluation of Asthma Biomarkers in Clinical Practice. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottin, S.; Doyen, V.; Pilette, C. Upper Airway Disease Diagnosis as a Predictive Biomarker of Therapeutic Response to Biologics in Severe Asthma. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1129300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrecht, B.N.; Hammad, H. The Airway Epithelium in Asthma. Nat Med 2012, 18, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, P.K. Remodeling in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Crombruggen, K.; Zhang, N.; Gevaert, P.; Tomassen, P.; Bachert, C. Pathogenesis of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011, 128, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemark, A.; Shteinberg, M.; De Soyza, A.; Haworth, C.S.; Richardson, H.; Gao, Y.; Perea, L.; Dicker, A.J.; Goeminne, P.C.; Cant, E.; et al. Characterization of Eosinophilic Bronchiectasis: A European Multicohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 205, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweik, R.A.; Boggs, P.B.; Erzurum, S.C.; Irvin, C.G.; Leigh, M.W.; Lundberg, J.O.; Olin, A.C.; Plummer, A.L.; Taylor, D.R. An Official ATS Clinical Practice Guideline: Interpretation of Exhaled Nitric Oxide Levels (FeNO) for Clinical Applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 184, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.L.; Scott, R.; Boyle, M.J.; Gibson, P.G. Inflammatory Subtypes in Asthma: Assessment and Identification Using Induced Sputum. Respirology 2006, 11, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.B.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Shteinberg, M.; Chalmers, J.D. Rethinking Bronchiectasis as an Inflammatory Disease. Lancet Respir Med 2024, 12, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I.; Hunt, J.; Barnes, P.J.; Alving, K.; Antczak, A.; Baraldi, E.; Becher, G.; van Beurden, W.J.C.; Corradi, M.; Dekhuijzen, R.; et al. Exhaled Breath Condensate: Methodological Recommendations and Unresolved Questions. Eur Respir J 2005, 26, 523–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguin, F.; Cardet, J.C.; Chung, K.F.; Diver, S.; Ferreira, D.S.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Gaga, M.; Kellermeyer, L.; Khurana, S.; Knight, S.; et al. Management of Severe Asthma: A European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society Guideline. Eur Respir J 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddel, H.K.; Taylor, D.R.; Bateman, E.D.; Boulet, L.P.; Boushey, H.A.; Busse, W.W.; Casale, T.B.; Chanez, P.; Enright, P.L.; Gibson, P.G.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Asthma Control and Exacerbations: Standardizing Endpoints for Clinical Asthma Trials and Clinical Practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 180, 59–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, H.G.; Liu, M.C.; Pavord, I.D.; Brusselle, G.G.; FitzGerald, J.M.; Chetta, A.; Humbert, M.; Katz, L.E.; Keene, O.N.; Yancey, S.W.; et al. Mepolizumab Treatment in Patients with Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleecker, E.R.; FitzGerald, J.M.; Chanez, P.; Papi, A.; Weinstein, S.F.; Barker, P.; Sproule, S.; Gilmartin, G.; Aurivillius, M.; Werkström, V.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab for Patients with Severe Asthma Uncontrolled with High-Dosage Inhaled Corticosteroids and Long-Acting Β2-Agonists (SIROCCO): A Randomised, Multicentre, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies-Gow, A.; Corren, J.; Bourdin, A.; Chupp, G.; Israel, E.; Wechsler, M.E.; Brightling, C.E.; Griffiths, J.M.; Hellqvist, Å.; Bowen, K.; et al. Tezepelumab in Adults and Adolescents with Severe, Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 1800–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Aliberti, S.; Blasi, F. Management of Bronchiectasis in Adults. Eur Respir J 2015, 45, 1446–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, P. 2025 GINA Report for Asthma. Lancet Respir Med 2025, 13, e41–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yan, M.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zeng, X.; Nie, Z.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, W.; et al. Impact of Asthma Severity on Surgical Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis Comorbid with Asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2025, 134, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, A.S.; Alt, J.A.; Detwiller, K.Y.; Rowan, N.R.; Gray, S.T.; Hellings, P.W.; Joshi, S.R.; Lee, J.T.; Soler, Z.M.; Tan, B.K.; et al. Management Paradigms for Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Individuals with Asthma: An Evidence-Based Review with Recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2023, 13, 1758–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertazzoni, G.; Conti, C.; Testa, G.; Pipolo, G.C.; Mattavelli, D.; Piazza, C.; Pianta, L. High Volume Nasal Irrigations with Steroids for Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Allergic Rhinitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2025, 282, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, K.J. In Asthma, Change Is the Only Constant. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2025, 211, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley-Yates, P.; Singh, D.; Igea, J.M.; Macchia, L.; Verma, M.; Berend, N.; Plank, M. Assessing the Effects of Changing Patterns of Inhaled Corticosteroid Dosing and Adherence with Fluticasone Furoate and Budesonide on Asthma Management. Adv Ther 2023, 40, 4042–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstahl, G.J.; Kleinjan, A.; Overbeek, S.E.; Prins, J.B.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Fokkens, W.J. Segmental Bronchial Provocation Induces Nasal Inflammation in Allergic Rhinitis Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braido, F.; Tiotiu, A.; Guidos-Fogelbach, G.; Baiardini, I.; Cosini, F.; Correia de Sousa, J.; Bikov, A.; Novakova, S.; Labor, M.; Kaidashev, I.; et al. Manifesto on Inhaled Triple Therapy in Asthma: An Interasma (Global Asthma Association–GAA) Document. Journal of Asthma 2022, 59, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.P.; Upham, J.W.; Bardin, P.G.; Hew, M. Rational Oral Corticosteroid Use in Adult Severe Asthma: A Narrative Review. Respirology 2019, 25, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, T.J.; Kronman, M.P. Clarifying the Role of Antibiotics in Acute Sinusitis Treatment. Pediatrics 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB, A.; MR, J.; MD, P.; PG, A.; MS, B.; JA, H.; WA, C. Antimicrobial Treatment Guidelines for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004, 130, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.K.; Park, C.S.; Kim, J.W.; Hwang, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Park, D.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Guidelines for the Antibiotic Use in Adults with Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. Infect Chemother 2017, 49, 326–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loperfido, A.; Cavaliere, C.; Begvarfaj, E.; Ciofalo, A.; D’Erme, G.; De Vincentiis, M.; Greco, A.; Millarelli, S.; Bellocchi, G.; Masieri, S. The Impact of Antibiotics and Steroids on the Nasal Microbiome in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Systematic Review According to PICO Criteria. J Pers Med 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psaltis, A.J.; Mackenzie, B.W.; Cope, E.K.; Ramakrishnan, V.R. Unraveling the Role of the Microbiome in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 149, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverino, E.; Goeminne, P.C.; McDonnell, M.J.; Aliberti, S.; Marshall, S.E.; Loebinger, M.R.; Murris, M.; Cantón, R.; Torres, A.; Dimakou, K.; et al. European Respiratory Society Guidelines for the Management of Adult Bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Boersma, W.; Lonergan, M.; Jayaram, L.; Crichton, M.L.; Karalus, N.; Taylor, S.L.; Martin, M.L.; Burr, L.D.; Wong, C.; et al. Long-Term Macrolide Antibiotics for the Treatment of Bronchiectasis in Adults: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019, 7, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.T.; Sullivan, A.L.; Chalmers, J.D.; De Soyza, A.; Stuart Elborn, J.; Andres Floto, R.; Grillo, L.; Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Harvey, A.; Haworth, C.S.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for Bronchiectasis in Adults. Thorax 2019, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Viskens, A.S.; Backer, V.; Conti, D.; de Corso, E.; Gevaert, P.; Scadding, G.K.; Wagemann, M.; Sprekelsen, M.B.; Chaker, A.; et al. EPOS/EUFOREA Update on Indication and Evaluation of Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps 2023. Rhinology 2023, 61, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Bachert, C.; Fokkens, W.; Desrosiers, M.; Wagenmann, M.; Lee, S.E.; Smith, S.G.; Martin, N.; Mayer, B.; Yancey, S.W.; et al. Mepolizumab for Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps (SYNAPSE): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021, 9, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Han, J.K.; Desrosiers, M.; Hellings, P.W.; Amin, N.; Lee, S.E.; Mullol, J.; Greos, L.S.; Bosso, J. V.; Laidlaw, T.M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Patients with Severe Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): Results from Two Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Phase 3 Trials. Lancet 2019, 394, 1638–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L. Efficacy and Safety of Biologics for Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps: A Meta-Analysis of Real-World Evidence. Allergy 2025, 80, 1256–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Okano, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Sunaga, Y.; Orimo, M.; Ishida, M. Reduction of Rescue Treatment With Dupilumab for Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps in Japan. Laryngoscope 2025, 135, 3093–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scadding, G.K.; Kariyawasam, H.H.; Scadding, G.; Mirakian, R.; Buckley, R.J.; Dixon, T.; Durham, S.R.; Farooque, S.; Jones, N.; Leech, S.; et al. BSACI Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Allergic and Non-Allergic Rhinitis (Revised Edition 2017; First Edition 2007). Clin Exp Allergy 2017, 47, 856–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creticos, P.S.; Gunaydin, F.E.; Nolte, H.; Damask, C.; Durham, S.R. Allergen Immunotherapy: The Evidence Supporting the Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Immunotherapy and Sublingual Forms of Immunotherapy for Allergic Rhinitis/Conjunctivitis and Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2024, 12, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonica, G.W.; Bachert, C.; Hellings, P.; Ryan, D.; Valovirta, E.; Wickman, M.; De Beaumont, O.; Bousquet, J. Allergen Immunotherapy (AIT): A Prototype of Precision Medicine. World Allergy Organization Journal 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Oishi, K.; Chikumoto, A.; Murakawa, K.; Ohteru, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Uehara, S.; Suetake, R.; Ohata, S.; Murata, Y.; et al. Impact of Sinus Surgery on Type 2 Airway and Systemic Inflammation in Asthma. Journal of Asthma 2021, 58, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.J.; Fu, C.H.; Wang, C.H.; Huang, C.C.; Huang, C.C.; Chang, P.H.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, C.C.; Wu, C.L.; Kuo, H.P. Impact of Chronic Rhinosinusitis on Severe Asthma Patients. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemitsu, Y.; Kurokawa, R.; Ono, J.; Fukumitsu, K.; Takeda, N.; Fukuda, S.; Uemura, T.; Tajiri, T.; Ohkubo, H.; Maeno, K.; et al. Increased Serum Periostin Levels and Eosinophils in Nasal Polyps Are Associated with the Preventive Effect of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Asthma Exacerbations in Chronic Rhinosinusitis Patients. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2020, 181, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Fischer, J.L.; Ramakrishnan, V.R.; Welch, K.C.; Kim, D.Y.; Won, T. Bin; Cho, J.H.; Mun, S.J.; Lee, J.T.; Beswick, D.M.; et al. A Systematic Classification of Surgical Approaches for the Sphenoid Sinus: Establishing a Standardized Nomenclature for Endoscopic Sphenoid Sinus Surgery. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2025, 18, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.; Staibano, P.; Snidvongs, K.; Nguyen, T.B.V.; Sommer, D.D. Extent of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2024, 24, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.J.; Snidvongs, K.; Kalish, L.H.; Oakley, G.M.; Sacks, R. Corticosteroid Nasal Irrigations Are More Effective than Simple Sprays in a Randomized Double-Blinded Placebo-Controlled Trial for Chronic Rhinosinusitis after Sinus Surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2018, 8, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promsopa, C.; Quannuy, T.; Chinpairoj, S.; Kirtsreesakul, V.; Prapaisit, U.; Suwanparin, N. A Randomized, Double-Blind Study Comparing Corticosteroid Irrigations and Nasal Sprays for Polyp Size Reduction in CRSwNP. Laryngoscope 2025, 135, 3550–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiles, S.A.; Gibson, P.G.; Agusti, A.; McDonald, V.M. Treatable Traits That Predict Health Status and Treatment Response in Airway Disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021, 9, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agusti, A.; Gibson, P.G.; McDonald, V.M. Treatable Traits in Airway Disease: From Theory to Practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023, 11, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).