Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

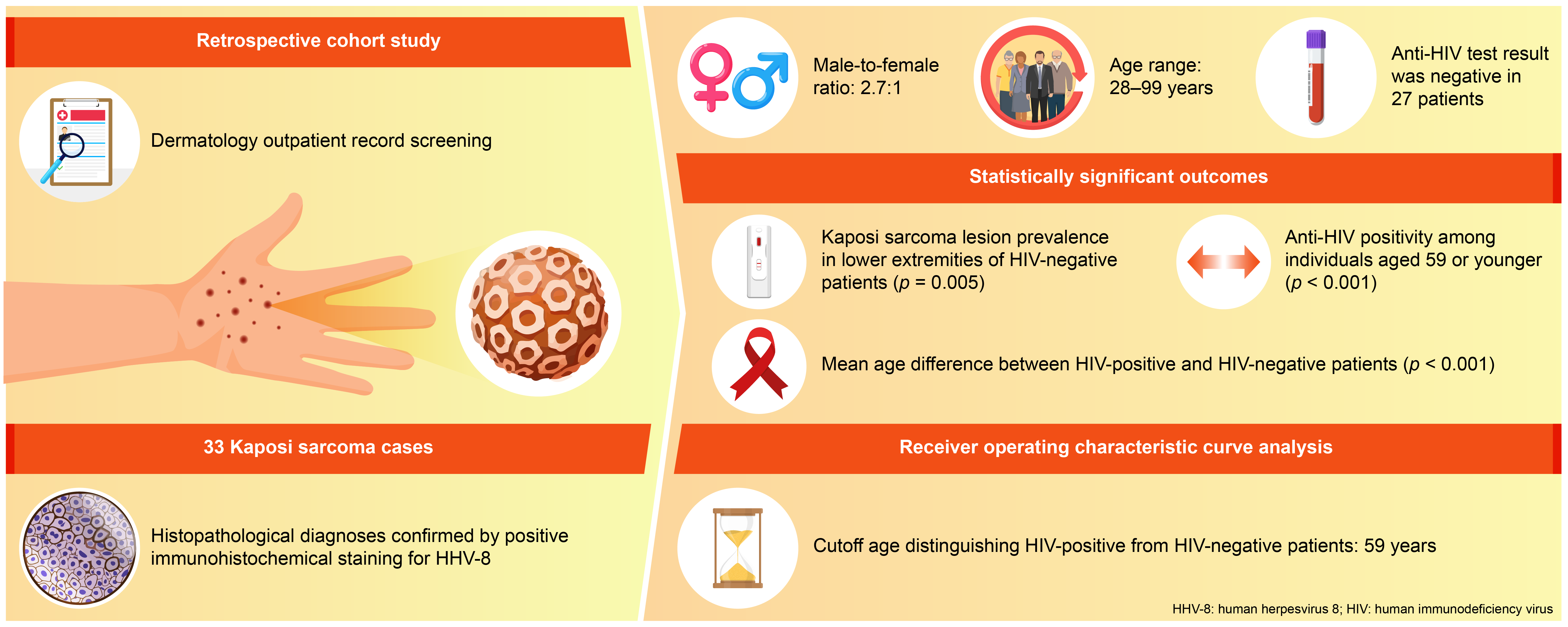

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HHV-8 | Human herpesvirus 8 |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Sars-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| Nd-YAG | Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet |

| ICD | International classification of diseases |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| LANA | Latency-associated nuclear antigen |

| Anti-GBM | Anti-glomerular basement membrane |

References

- Tsai, K.Y. : West Sussex, Great Britain, 2024; Volume 4, pp. 138.1-138.6.Sarcoma. In Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, 10thed.; Griffiths, C., Barker, J., Bleiker, T., Hussain, W., Simpson, R., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: West Sussex, Great Britain, 2024; Volume 4, p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi, E.; Tinunin, L.; Grassi, T.; Maio, V.; Grandi, V. Bullous Kaposi Sarcoma: An Uncommon Blistering Variant in an HIV-Negative Patient. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygier, J.; Sass, U.; Meiers, I.; Marneffe, A.; de Vicq de Cumptich, M.; Richert, B. Kaposi Sarcoma of the Nail Unit: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Skin. Appendage. Disord. 2023, 9, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoval, J.; Bonfill-Ortí, M.; Martínez-Molina, L.; Valentí-Medina, F.; Penín, R.M.; Servitje, O. Evolution of Kaposi sarcoma in the past 30 years in a tertiary hospital of the European Mediterranean basin. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, F.; Giordano, S.; Latini, A.; Muscianese, M. New-onset cutaneous kaposi’s sarcoma following SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3747–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardini, G.; Odolini, S.; Moioli, G.; Papalia, D.A.; Ferrari, V.; Matteelli, A.; Caligaris, S. Disseminated Kaposi sarcoma following COVID-19 in a 61-year-old Albanian immunocompetent man: a case report and review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2021, 26, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, B.; Burningham, K.; Alkul, M.; Tyring, S. Treatment of Kaposi sarcoma with intralesional cidofovir in an HIV-negative man. JAAD Case Rep. 2023, 42, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.A.; Efendiev, K.T.; Kornev, D.O.; Samoylova, S.I.; Fatyanova, A.S.; Karpova, R.V.; Reshetov, I.V.; Loschenov, V.B. Photodynamic therapy of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with video-fluorescence control. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, M.R.; Luppino, I.; Spurio Catena, A.; Micali, G. Nodular Classic Kaposi’s Sarcoma Treated With Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser Delivered Through a Tilted Angle: Outcome and 12-Month Follow Up. Lasers Surg. Med. 2020, 52, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tancredi, V.; Licata, G.; Buononato, D.; Boccellino, M.P.; Argenziano, G.; Giorgio, C.M. Topical Sirolimus 0.1% as Off-Label Treatment of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, C.M.R.; Licata, G.; Briatico, G.; Babino, G.; Fulgione, E.; Gambardella, A.; Alfano, R.; Argenziano, G. Comparison between propranolol 2% cream versus timolol 0.5% gel for the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Int. J. Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Genedy, R.M.; Owais, M.; El Sayed, N.M. Propranolol: A Promising Therapeutic Avenue for Classic Kaposi Sarcoma. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2025, 15, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daadaa, N.; Souissi, A.; Chaabani, M.; Chelly, I.; Ben Salem, M.; Mokni, M. Involution of classic Kaposi sarcoma lesions under acitretin treatment Kaposi sarcoma treated with acitretin. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 3340–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Yu, Y.; Su, Z.; Lu, Y. Rapid improvements in Kaposi sarcoma with metformin: a report of two cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2025, 193, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, S.; Schöfer, H.; Hoffmann, C.; Claßen, J.; Kreuter, A.; Leiter, U.; Oette, M.; Becker, J.C.; Ziemer, M.; Mosthaf, F.; Sirokay, J.; Ugurel, S.; Potthoff, A.; Helbig, D.; Bierhoff, E.; Schulz, T.F.; Brockmeyer, N.H.; Grabbe, S. S1 Guidelines for the Kaposi Sarcoma. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettuzzi, T.; Lebbe, C.; Grolleau, C. Modern Approach to Manage Patients With Kaposi Sarcoma. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, e70294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavak, E.E.; Ürün, Y. Classical Kaposi sarcoma: an insight into demographic characteristics and survival outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2025, 25, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Paul, P.M.; Ko, N.; Garlapati, S. A Retrospective Study on the Incidence of Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States From 1999 to 2020 Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research (CDC WONDER) Database. Cureus. 2025, 17, e77213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, S.; Zorlu, O.; Bulbul Baskan, E.; Balaban Adim, S.; Aydogan, K.; Saricaoglu, H. Retrospective Analysis of 91 Kaposi’s Sarcoma Cases: A Single-Center Experience and Review of the Literature. Dermatology. 2018, 234, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.Y.; Lin, C.L.; Chen, G.S.; Hu, S.C. Clinical features of Kaposi’s sarcoma: experience from a Taiwanese medical center. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, N.; Blomqvist, C.; Kivelä, P. Kaposi sarcoma in Southern Finland (2006-2018). Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; He, F.; Jielili, A.; Zhang, Z.R.; Cui, Z.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Guo, H.T. A retrospective study of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Hotan region of Xinjiang, China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e35552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalya, P.L.; Mbunda, F.; Rambau, P.F.; Jaka, H.; Masalu, N.; Mirambo, M.; Mushi, M.F.; Kalluvya, S.E. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a 10-year experience with 248 patients at a single tertiary care hospital in Tanzania. BMC Res. Notes. 2015, 8, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabar, S.; Costagliola, D. Epidemiology of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounouga, D.N.; Kouotou, E.A.; Nansseu, J.R.; Zoung-Kanyi Bissek, A.C. Epidemiological and Clinical Patterns of Kaposi Sarcoma: A 16-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study from Yaoundé, Cameroon. Dermatology. 2018, 234, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Lee, C.S. The emerging role of the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) in human neoplasia. Pathology. 2001, 33, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Lee, C.S. Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinico-pathological analysis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and non-HIV associated cases. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2002, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Tian, T.; Wang, B.; Lu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.F.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Zou, H. Global patterns and trends in Kaposi sarcoma incidence: a population-based study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2023, 11, e1566–e1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

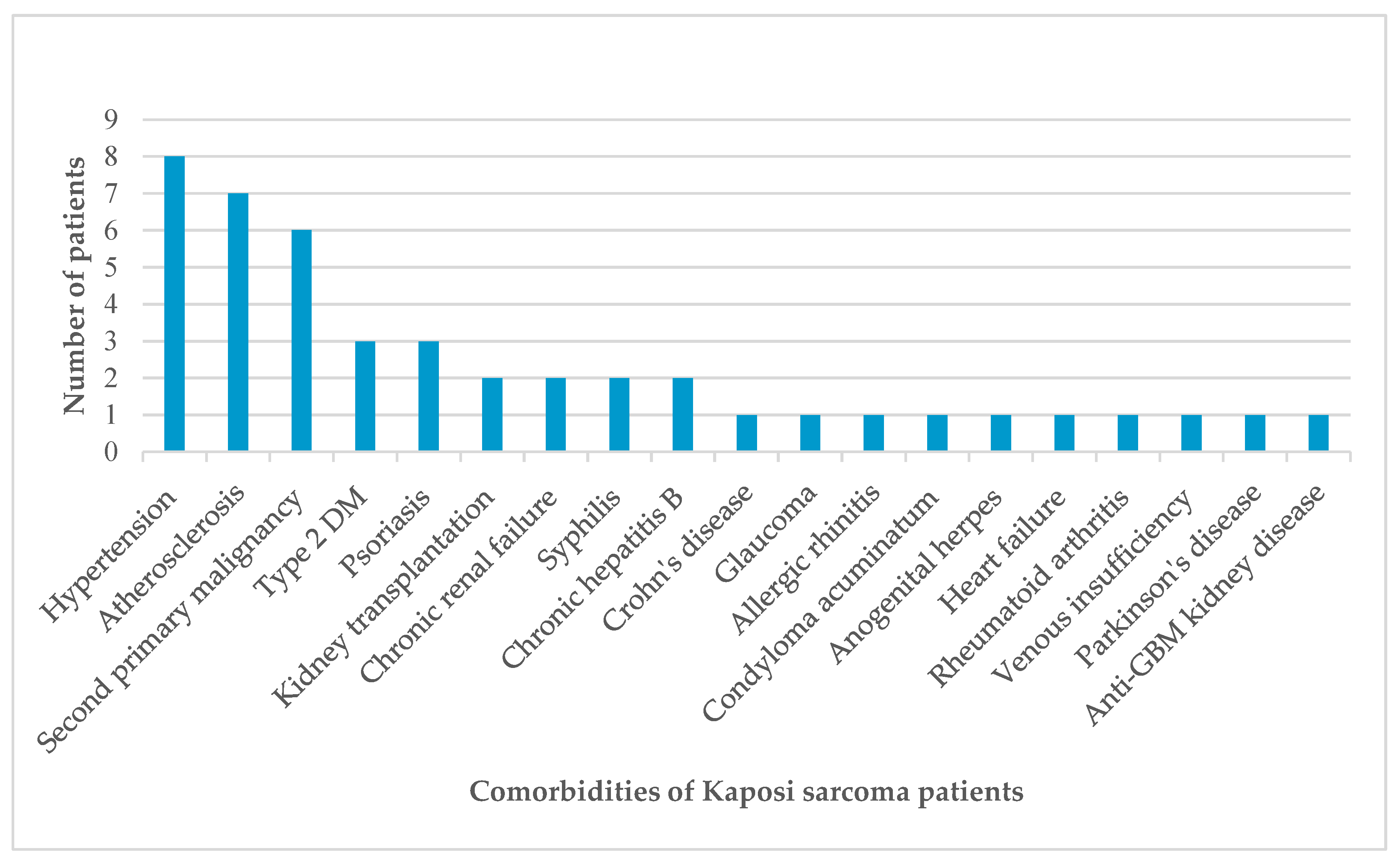

- The China PEACE Collaborative Group. Association of age and blood pressure among 3.3 million adults: insights from China PEACE million persons project. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safai, B.; Miké, V.; Giraldo, G.; Beth, E.; Good, R.A. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma with second primary malignancies: possible etiopathogenic implications. Cancer. 1980, 45, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, L.; Genovese, G.; Tourlaki, A.; Della Bella, S. Coexistence of Kaposi’s sarcoma and psoriasis: is there a hidden relationship? Eur. J. Dermatol. 2018, 28, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Chen, P.C.; Chen, L.W.; Wang, S.S.; Shih, Y.J.; Chen, L. Y,.; Chen, C.J., Hung, C.H., Eds.; Lin, C.L. Diabetes and risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma: effects of high glucose on reactivation and infection of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 80595-80611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugcu, M.; Kasapoglu, U.; Ruhi, C.; Sayman, E. Kaposi Sarcoma in a Chronic Renal Failure Patient Treated by Hemodialysis. Turk. Neph. Dial. Transpl. 2016, 25, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Chun, J.S.; Hong, S.K.; Kang, M.S.; Seo, J.K.; Koh, J.K.; Sung, H.S. Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with chronic renal failure undergoing dialysis. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, J.A. Anergy and immunosuppression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rev. Colomb. Reumatol. 2021, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Age | Gender | Localization | Anti-HIV | Comorbidity |

| 1 | 53 | Male | Bilateral cruris and feet | Negative | Kidney transplant recipient |

| 2 | 82 | Male | Bilateral wrists and feet | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| 3 | 68 | Male | Left hand, right foot | Negative | Hypertension, chronic renal failure, Crohn’s disease |

| 4 | 67 | Female | Left arm, left hand, right foot | Negative | None |

| 5 | 81 | Female | Right ankle | Negative | Hypertension, glaucoma, chronic peripheral venous insufficiency |

| 6 | 65 | Female | Left foot | Negative | Allergic rhinitis |

| 7 | 50 | Male | Right axilla and chest | Positive | Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), condyloma acuminatum, anogenital herpes |

| 8 | 75 | Male | Right cruris | Negative | Type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, renal cell carcinoma |

| 9 | 84 | Male | Right foot | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| 10 | 30 | Male | Extensive skin lesions | Positive | None |

| 11 | 45 | Male | Extensive skin lesions | Positive | None |

| 12 | 78 | Male | Left ankle | Negative | Psoriasis |

| 13 | 54 | Male | Extensive skin lesions | Positive | Syphilis |

| 14 | 99 | Female | Bilateral cruris | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| 15 | 71 | Male | Left hand, left foot | Negative | Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, type 2 DM, atherosclerosis, chronic hepatitis B |

| 16 | 81 | Female | Right knee | Negative | Atherosclerosis |

| 17 | 72 | Male | Left elbow | Negative | Psoriasis |

| 18 | 69 | Male | Left arm, bilateral feet | Negative | Thyroid papillary carcinoma, glioblastoma |

| 19 | 70 | Male | Left knee, left labial commissure | Negative | None |

| 20 | 73 | Female | Right arm, right foot | Negative | Hypertension |

| 21 | 79 | Male | Bilateral cruris | Negative | Basal cell carcinoma |

| 22 | 74 | Male | Right thigh | Negative | Prostate carcinoma |

| 23 | 43 | Male | Bilateral cruris | Negative | Kidney transplant recipient |

| 24 | 81 | Male | Right ankle | Negative | Psoriasis |

| 25 | 28 | Male | Left arm, left cruris, trunk | Positive | None |

| 26 | 77 | Male | Bilateral arms and legs | Negative | Parkinson’s disease, hypertension, prostate carcinoma |

| 27 | 54 | Male | Left cruris, left ankle | Positive | Syphilis |

| 28 | 72 | Female | Right foot | Negative | None |

| 29 | 53 | Male | Bilateral feet, gastric antrum and corpus | Negative | Anti-glomerular basement membrane kidney disease |

| 30 | 82 | Female | Left cruris | Negative | Chronic hepatitis B, rheumatoid arthritis |

| 31 | 64 | Female | Left arm | Negative | None |

| 32 | 80 | Male | Right foot | Negative | None |

| 33 | 77 | Male | Right ankle | Negative | Hypertension, atherosclerosis, chronic renal failure, heart failure |

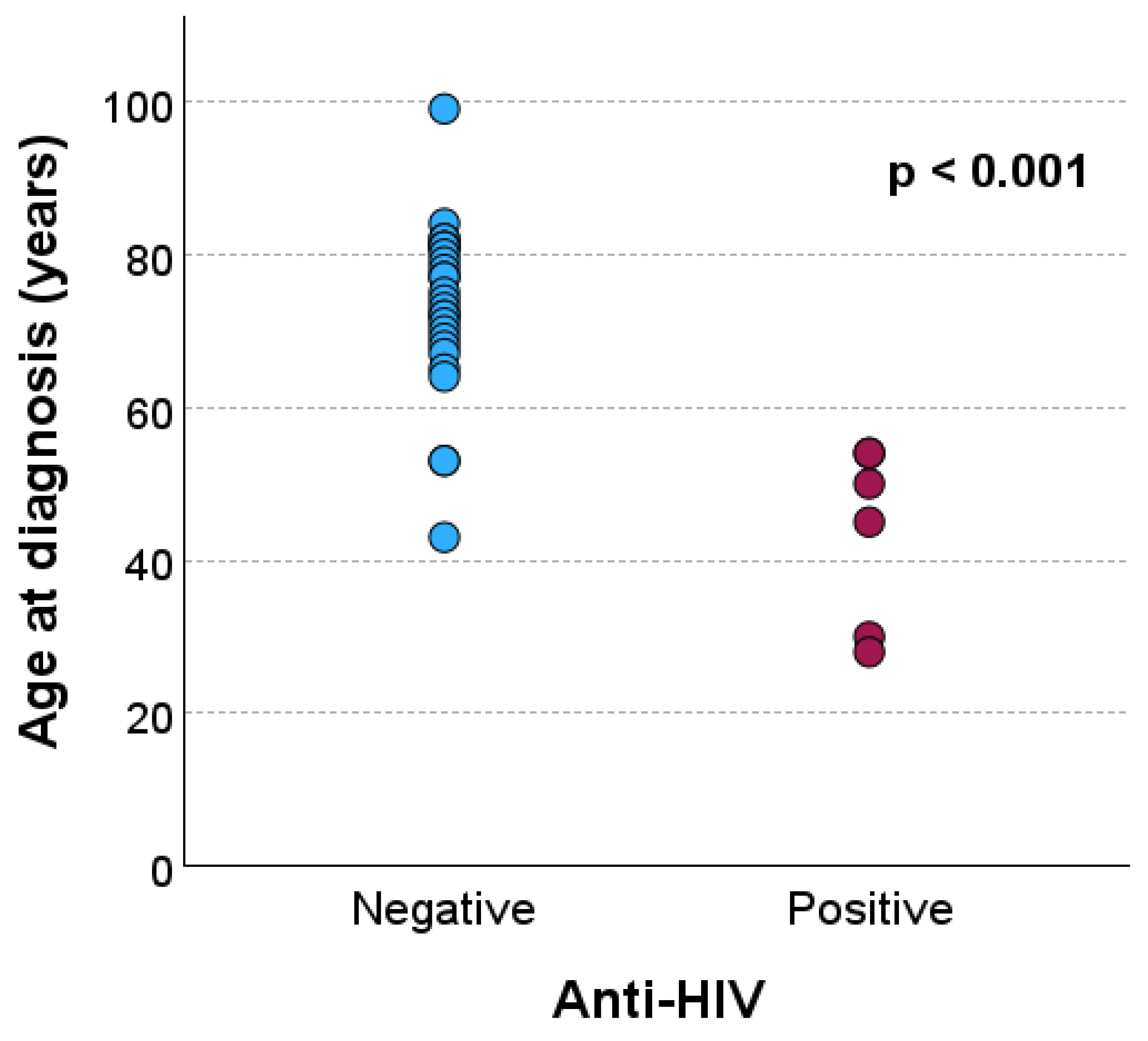

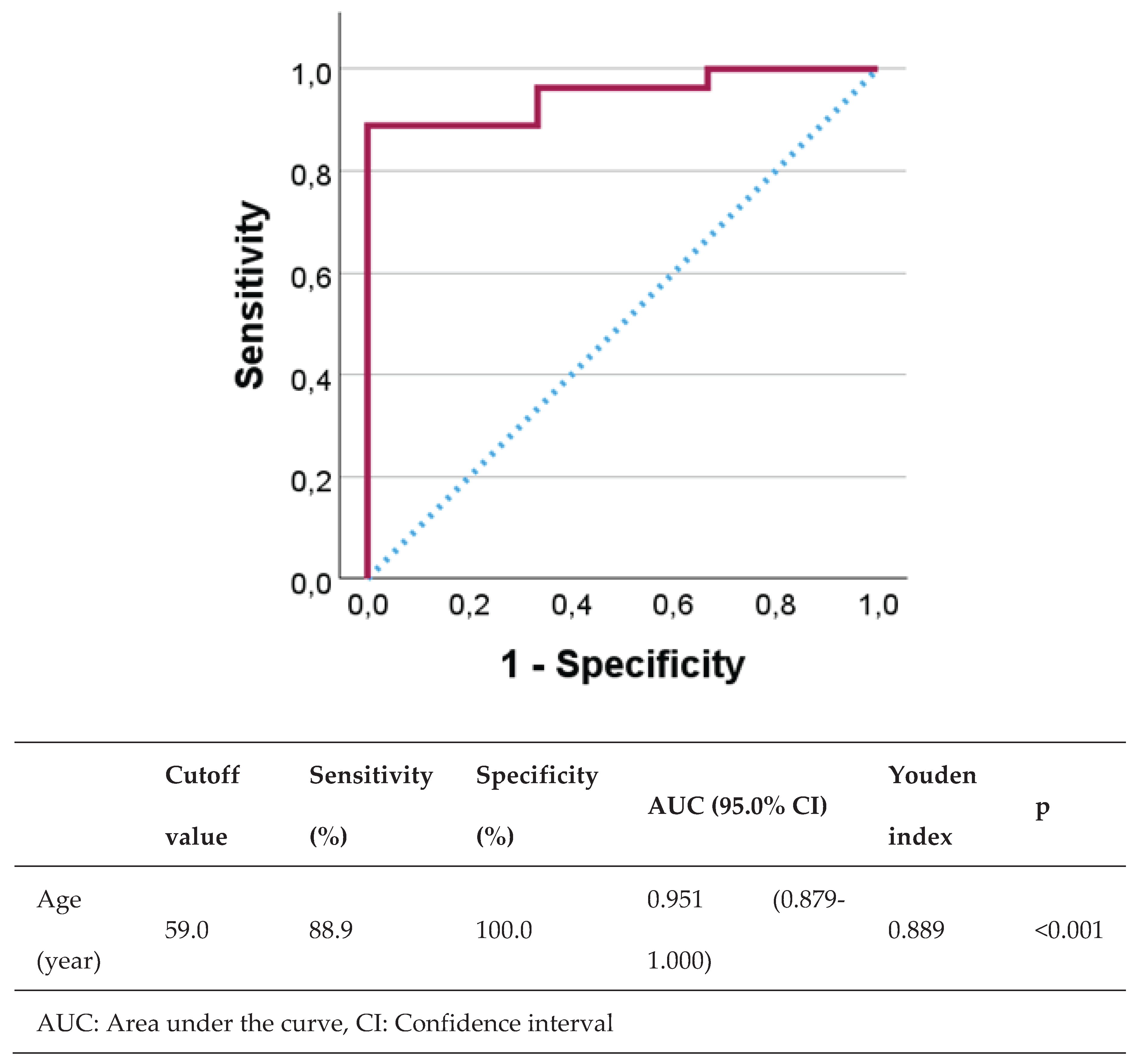

| Anti-HIV | p | |||

| Negative | Positive | |||

| Age (year), mean ± standard deviation | 73.0 ± 11.2 | 43.5 ± 11.7 | <0.001a | |

| Age (year), n (%) | ≤59 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | <0.001b |

| ≥60 | 24 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| a Mann-Whitney U test; b Fisher’s exact test | ||||

| Anti-HIV | p* | ||

| Negative, n (%) | Positive, n (%) | ||

| Lower extremities | 25 (92.6) | 2 (33.3) | 0.005 |

| Upper extremities | 9 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0.640 |

| Trunk | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0.028 |

| Head | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Diffuse skin involvement | 0 (0.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0.004 |

| Gastrointestinal system | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| *Fisher’s exact test | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).