Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Understanding how processes of magma genesis and magma differentiation control and modify the chemical composition of erupted lavas from the geochemical measurements of the latter is an under-constrained inverse problem as there is only one known parameter – the measured composition of the erupted lava – but two unknown parameters – the chemical composition and lithology of the source before melting and how melting, crystallization, and melt-rock interactions act to alter the lava en route to the surface. In this invited contribution, we review nearly seven decades of scientific research that demonstrate the potential of U and Th decay series measurements for unraveling the complexities of oceanic magmatism. We review the underlying nuclear theory, geochemical principles, and application of the 238U, 235U, and 232Th decay series for (i) defining the timescales of magma genesis during decompression mantle melting, (ii) establishing the timescales of magma recharge and magma degassing, and (iii) determining the eruption ages of oceanic Quaternary volcanism.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

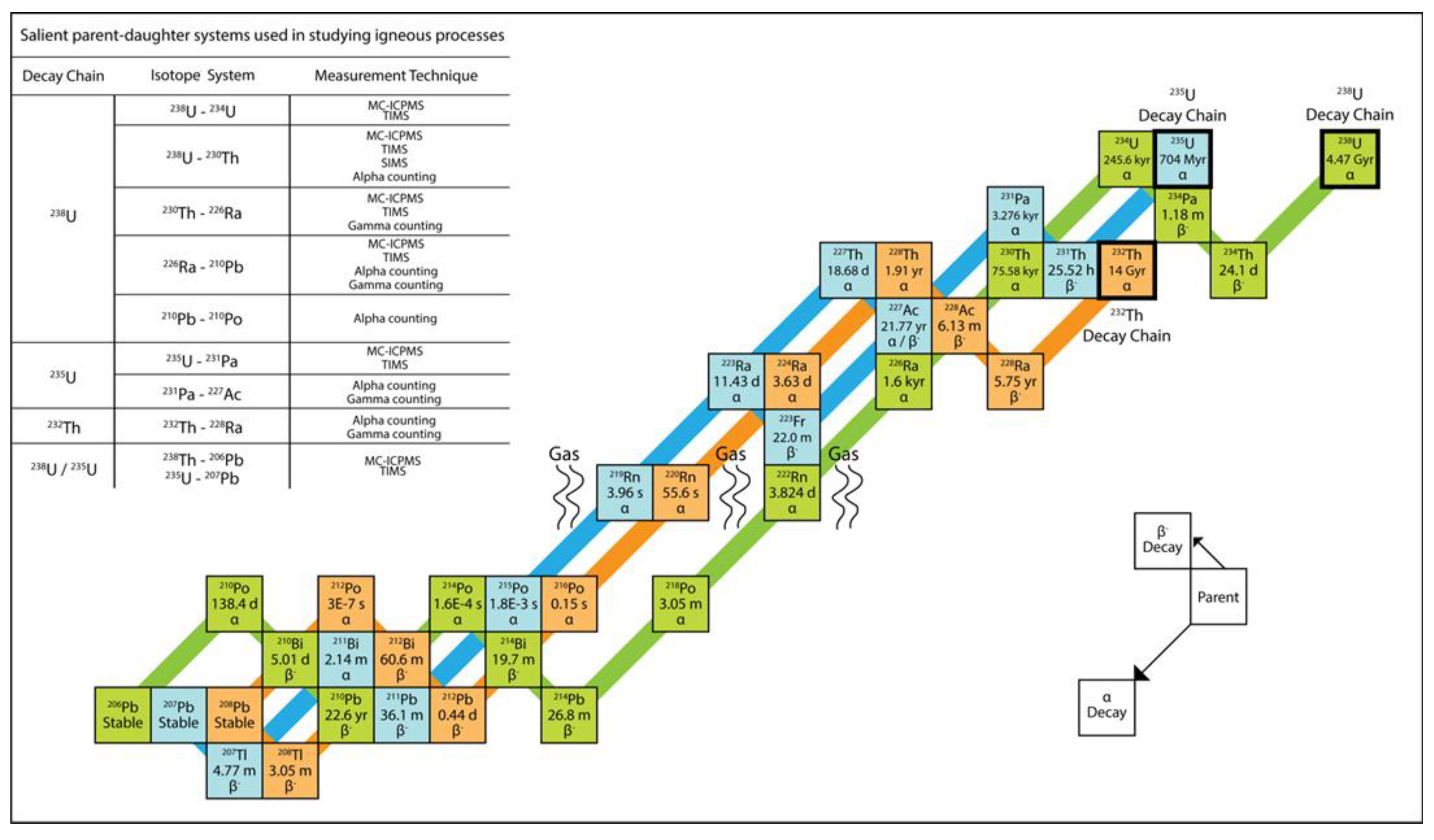

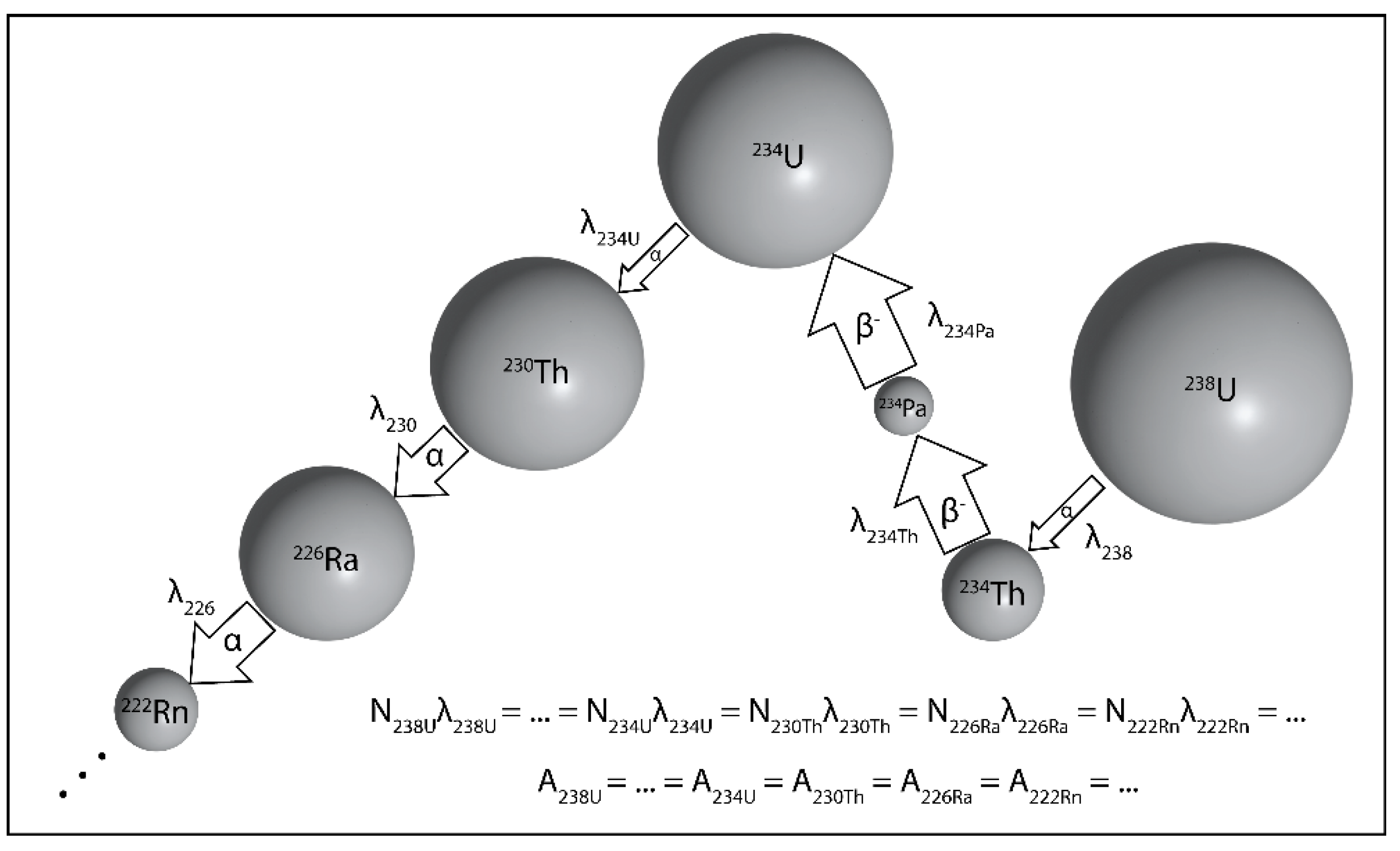

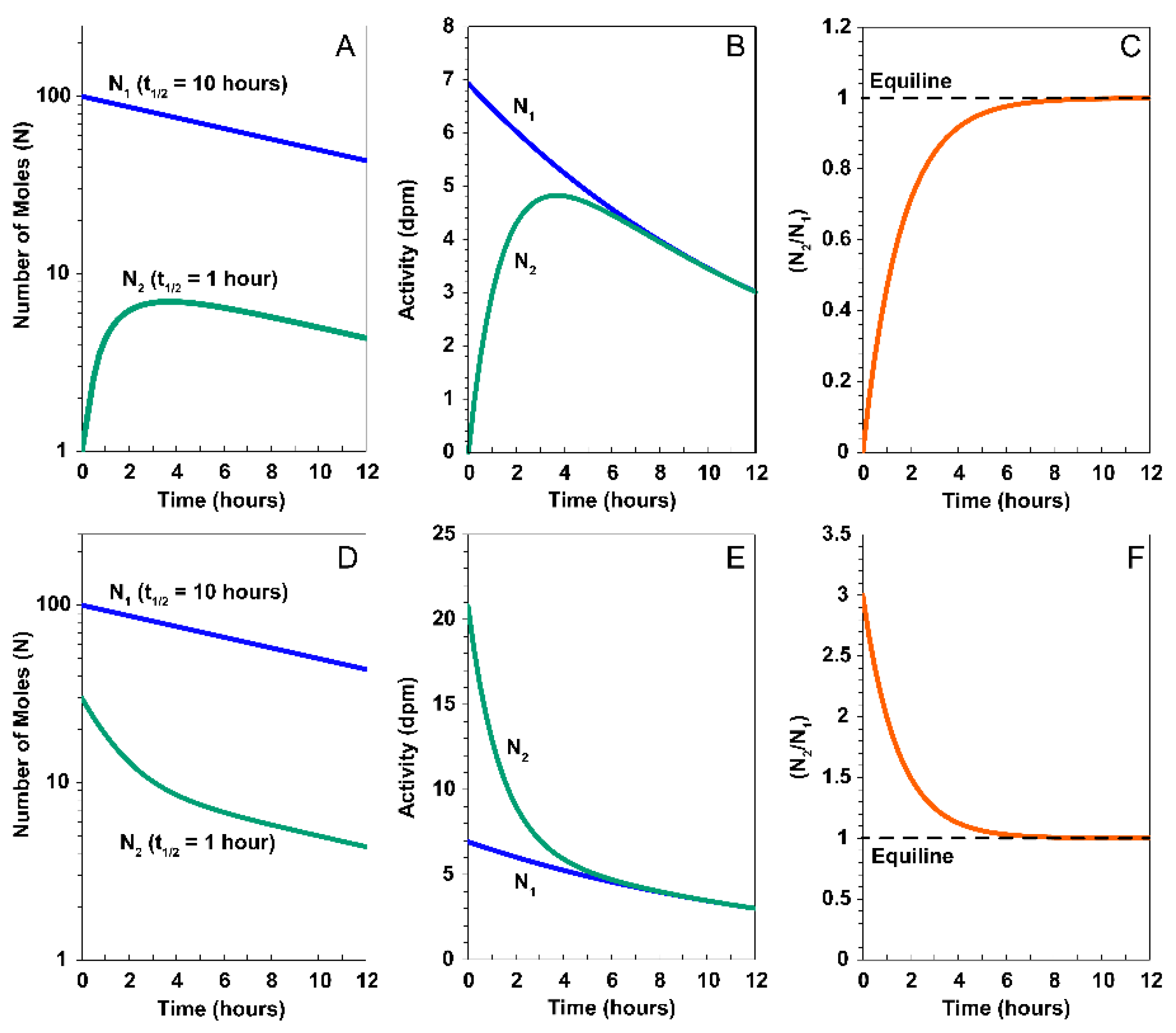

- Section 2 presents an overview of the theoretical formalism of the U and Th decay series' unique isotope systematics, using 238U-234U-230Th within the 238U decay series as an explicit example.

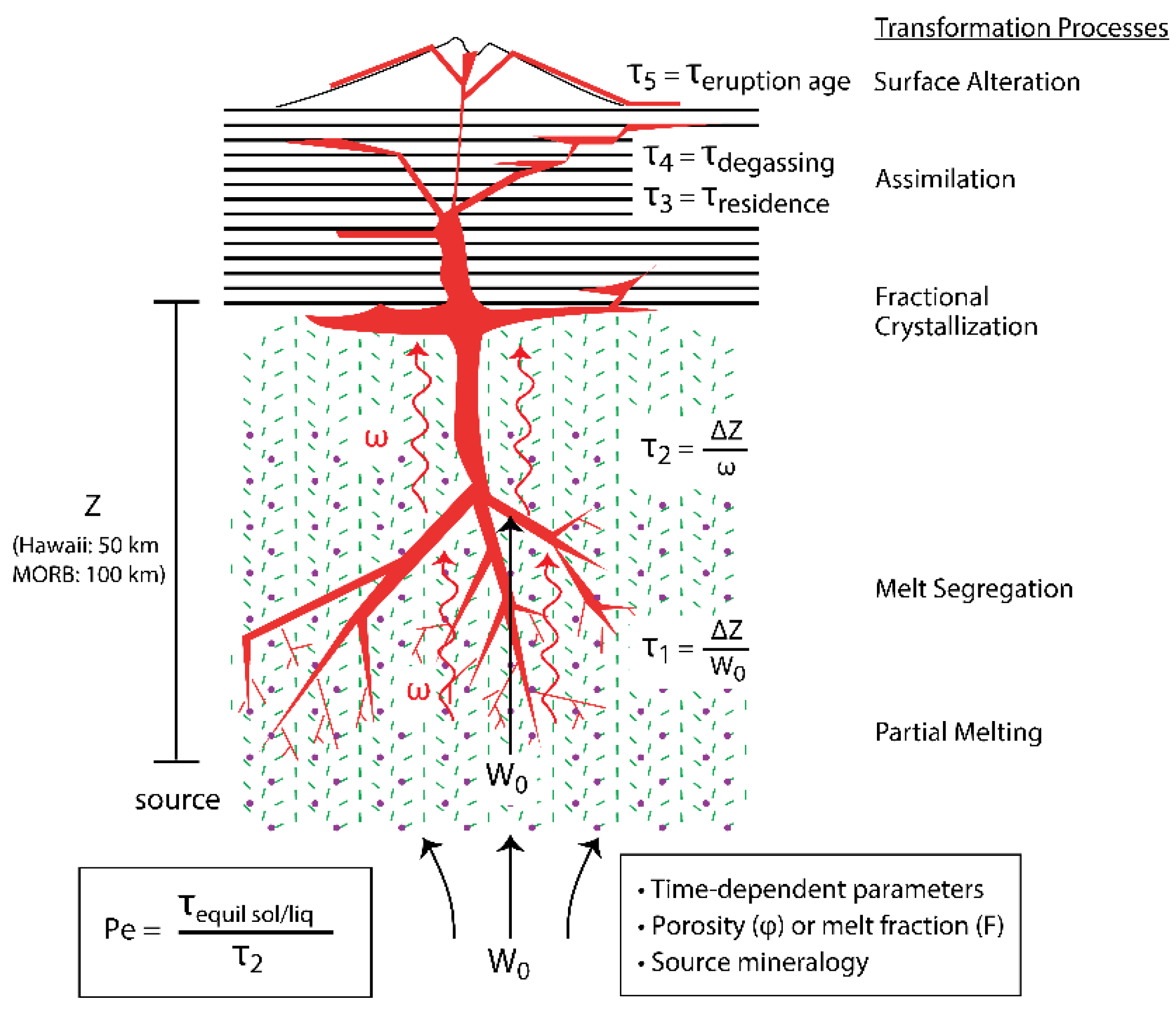

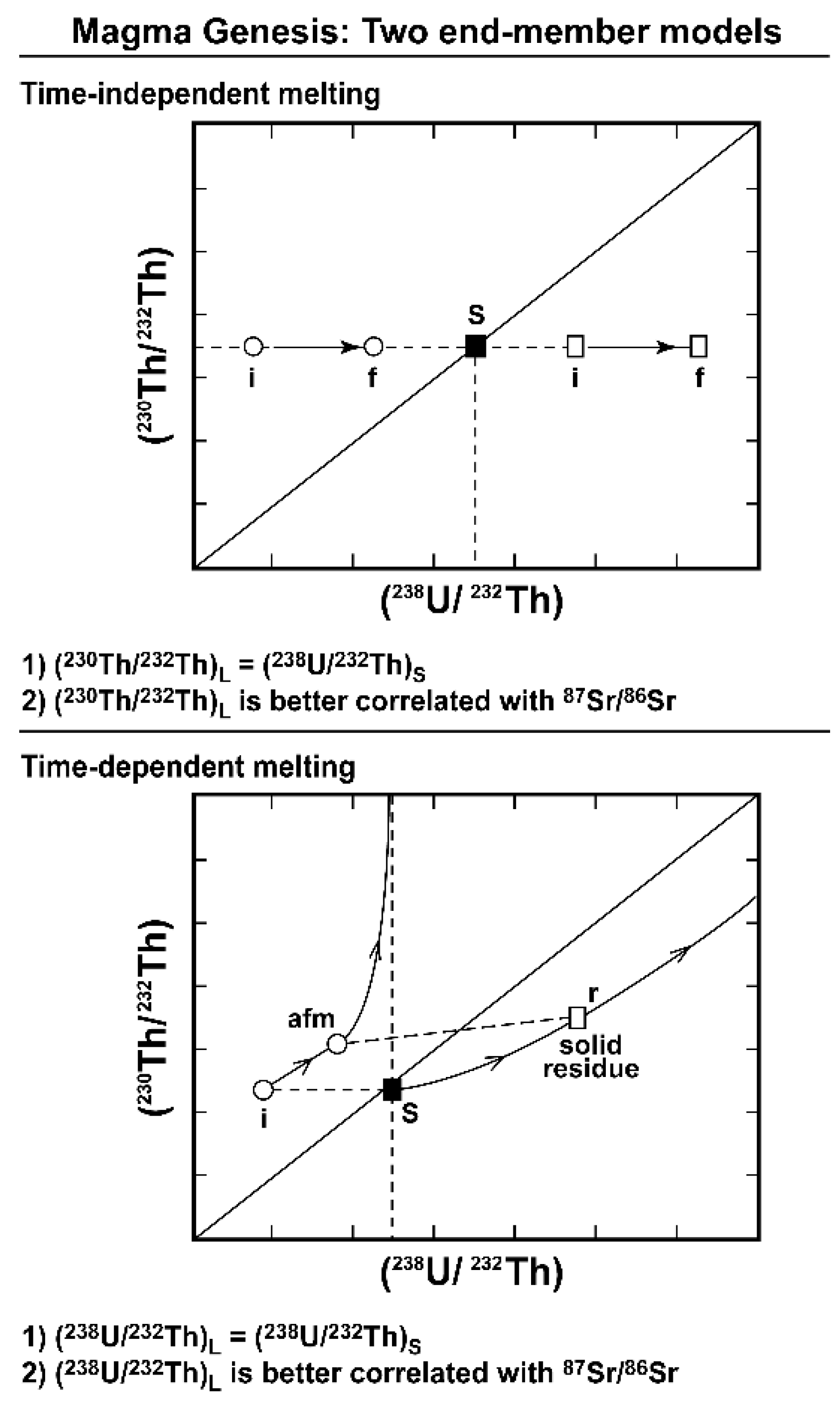

- Section 3 examines the geochemical principles and assumptions particular to the application of the 238U, 235U, and 232Th decay series to decompression mantle melting in oceanic settings. It focuses on the differences between time-independent melting models such as batch and tractional melting, which rely solely on elemental fractionation and time-dependent melting models that in turn take into consideration the timescales of melting and incorporate daughter ingrowth during melting. Specific examples of how different melting models and different lithologies produce divergent results, as well as the reasoning behind interpreting and selecting any model over another, are then considered. Melt generation at both divergent plate boundaries (MORB) and intraplate hotspots (OIB) are assessed.

- Section 4 presents the application of the 238U, 235U, and 232Th decay series for dating eruption ages of volcanic rocks using three different approaches: 1) age limits, whereby the presence of disequilibria can place bounds on the eruption age of a lava; 2) internal mineral isochron methods, which establish the crystallization age of a volcanic rock; and 3) U-Th-Ra 'model' ages, which couple measurements of U and Th disequilibria with geological, geochemical, and isotopic constraints to establish eruption ages for a lava or a lava sequence.

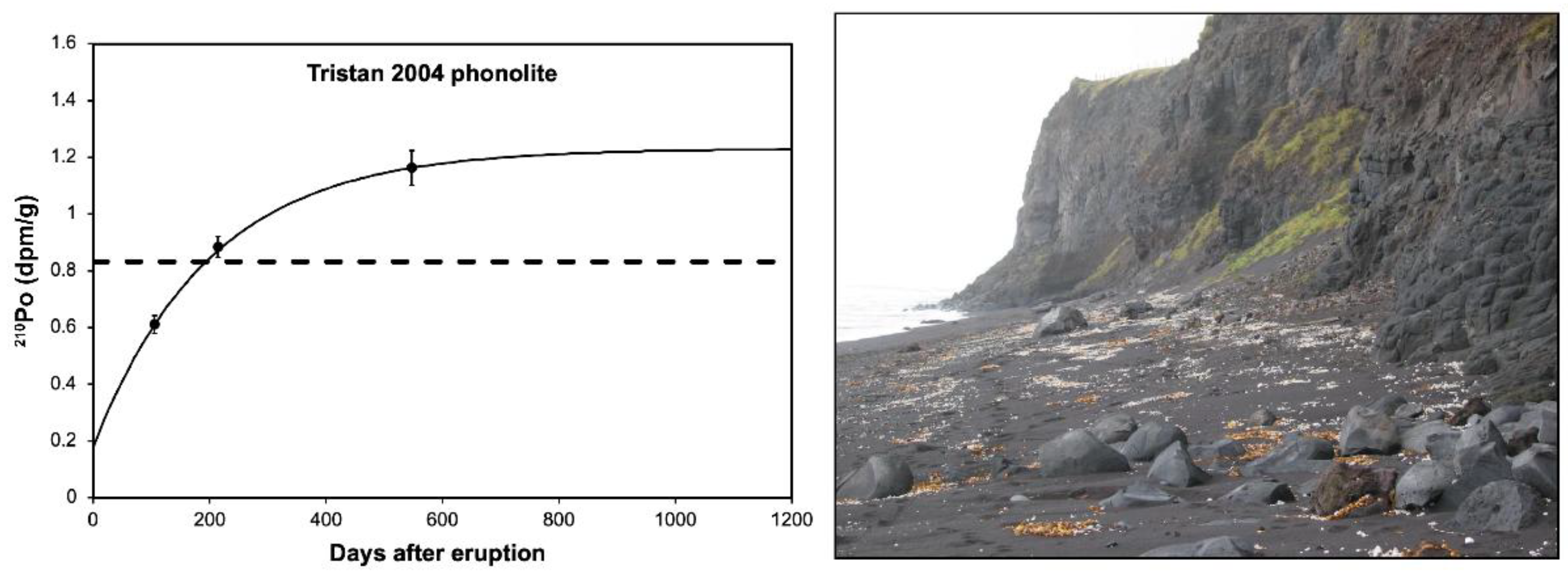

- Section 5 presents the application of 226Ra-210Pb-210Po disequilibria to establishing the timescales of magma recharge and degassing, which is directly linked to a volcano’s activity and fundamental to our understanding of physical eruption dynamics and hazard assessment. We look at three specific examples: Kilauea in the Hawaiian Archipelago, Tristan de Cunha in the South Atlantic Ocean, and Mount Erebus Volcano in Antarctica.

- Section 6 provides a historical overview of current and past analytical methodologies used to measure 238U, 235U, and 232Th decay series isotopes. We highlight recent improvements in mass spectrometry that have greatly influenced this field of study, as well as the alpha counting methods used for 210Pb-210Po measurements.

2. The Theoretical Construct of Multiple Nuclides Decaying in a Series

3. U-Th-Ra and U-Pa Series Constraints on Decompression Melting at Divergent Plate Boundaries and Intraplate Hotspots

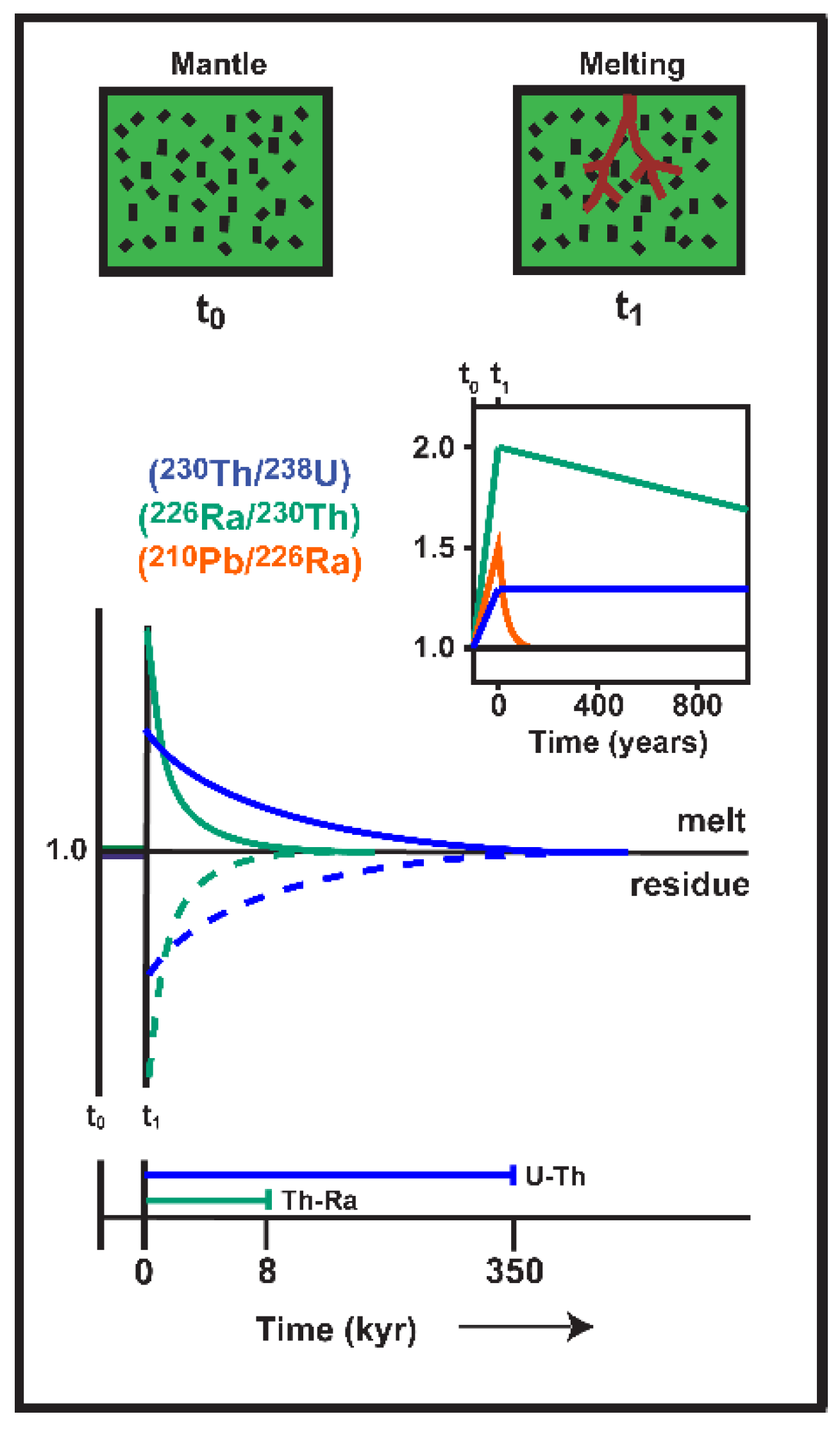

3.1. Time-Dependent Melting Models

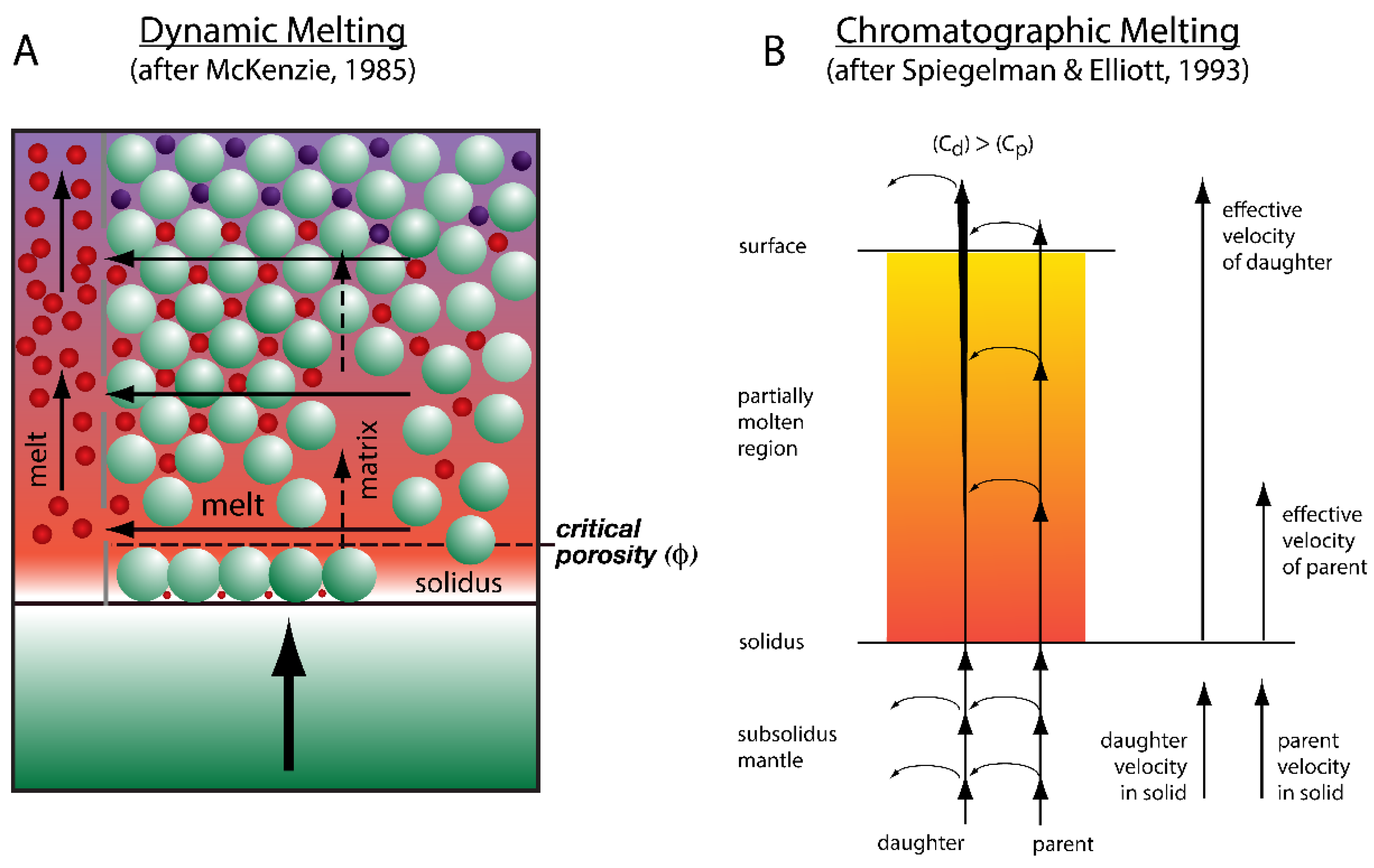

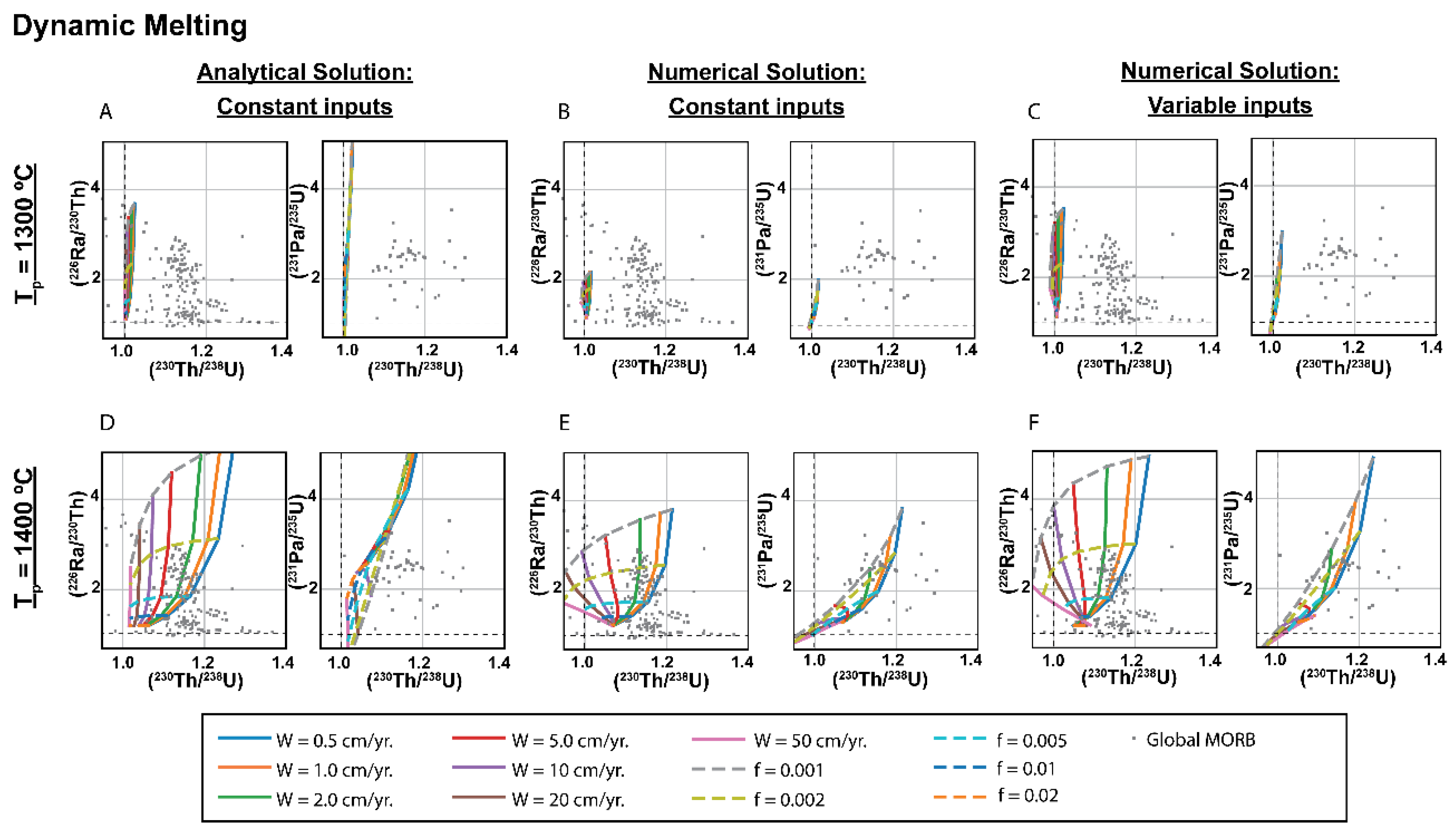

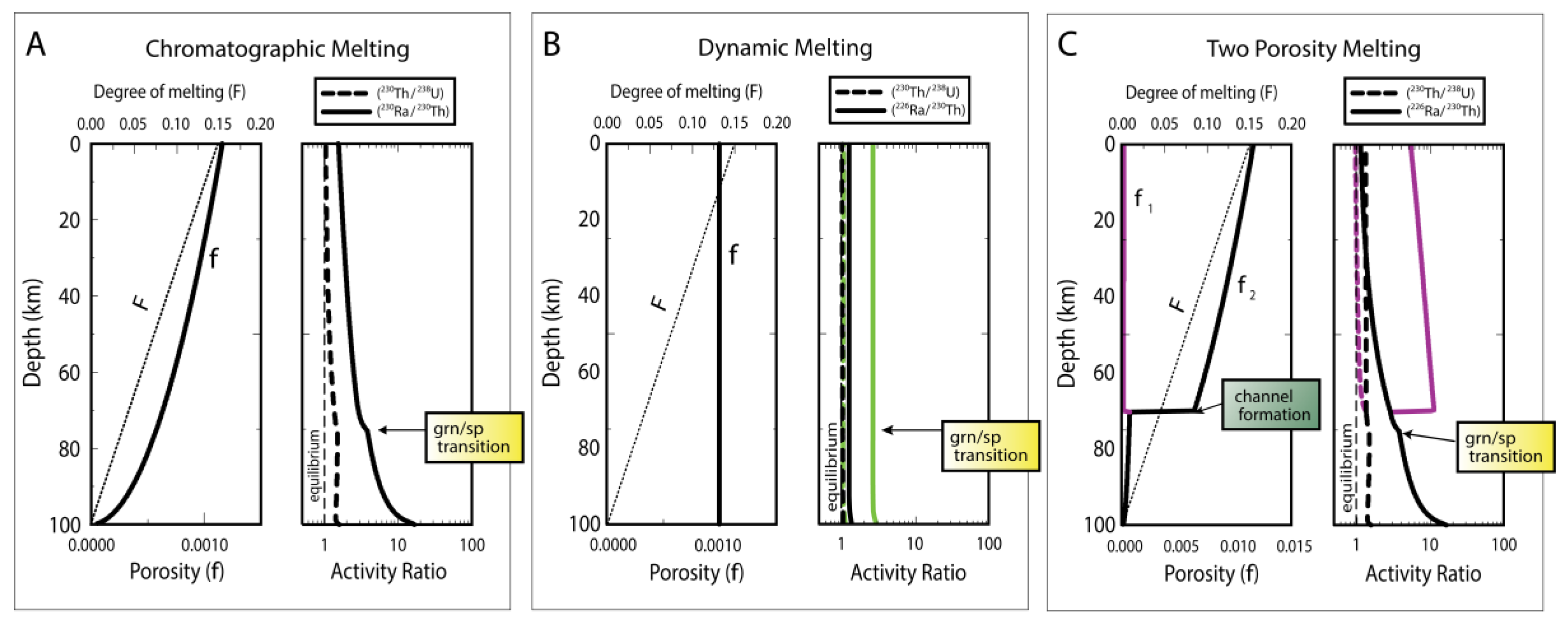

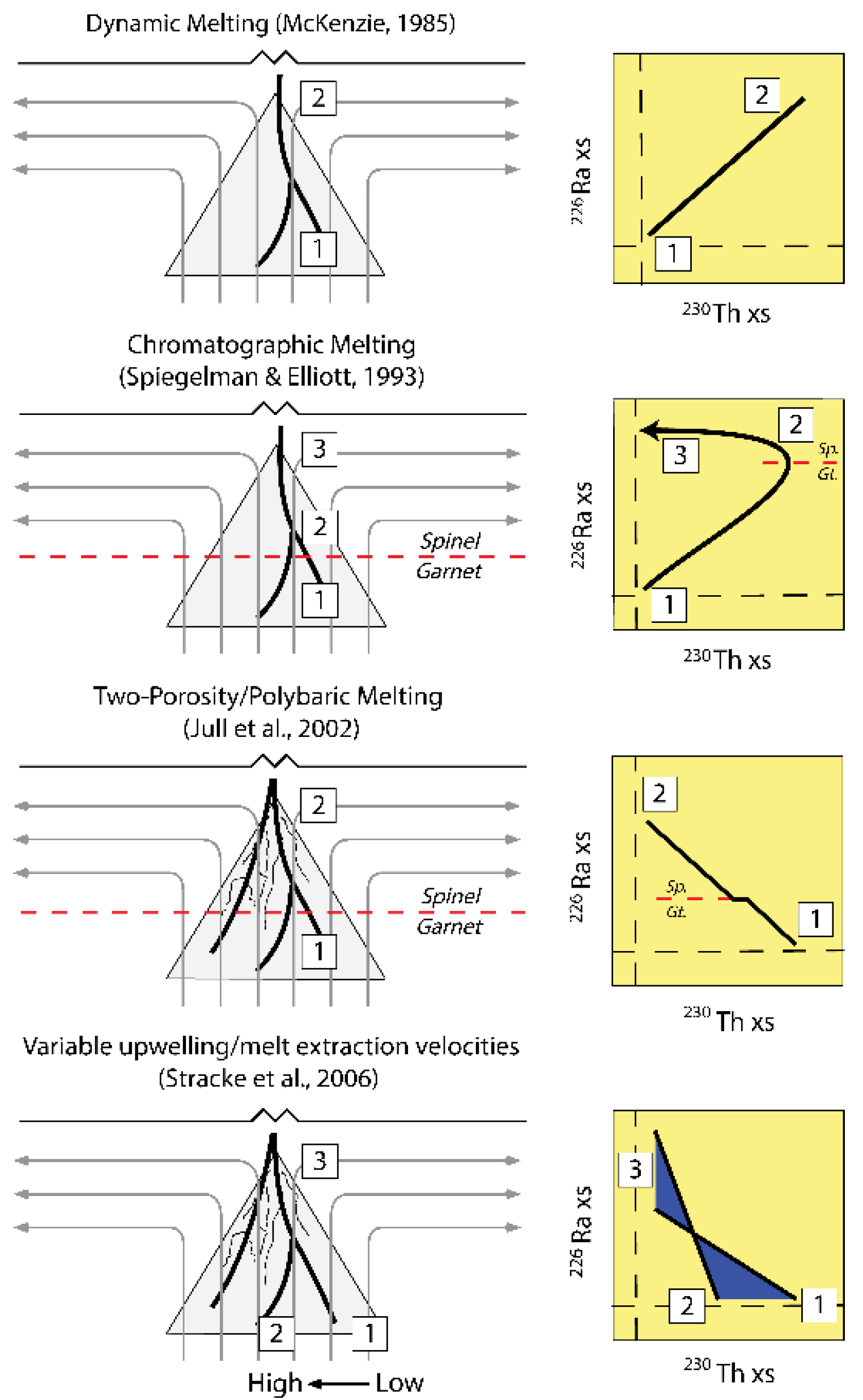

3.2. Dynamic Melting

| Isotope | Abundance | Half-life | Decay Constant | Reference |

| 238U | 99.2742% | 4.4683 ± 0.0024 x 109 yr | 1.5513 x 10–10 yr–1 | [48] |

| 234U | 0.0054% | 245,620 ± 260 yr | 2.82206 x 10–6 yr–1 | [49] |

| 230Th | 0.02% | 75,584 ± 110 yr | 9.1706 × 10–6 yr–1 | [49] |

| 226Ra | Trace | 1,600 ± 7 yr | 4.332 x 10–4 yr–1 | [50] |

| 222Rn | Trace | 3.8235 ± 0.0004 d | 1.8 x 10–1 d–1 | [50] |

| 210Pb | Trace | 22.6 ± 0.1 yr | 3.07 x 10-2 yr–1 | [51] |

| 210Po | Trace | 138.4 ± 0.1 d | 5.008 x 10–3 d–1 | [51] |

| 235U | 0.7204% | 7.0381 ± 0.0048 x 108 yr | 9.8485 x 10–10 yr–1 | [48] |

| 231Pa | 100% | 32,760 ± 220 yr | 2.1158 x 10–5 yr–1 | [52] |

| 227Ac | Trace | 21.77 ± 0.02 yr | 3.184 x 10–2 yr–1 | [51] |

| 232Th | 99.98% | 1.401 ± 0.007 x 1010 yr | 4.948 x 10–11 yr–1 | [53] |

| 228Ra | Trace | 5.75 ± 0.03 yr | 1.21 x 10–1 yr–1 | [50] |

| 224Ra | Trace | 3.6319 ± 0.0023 d | 1.9085 x 10–1 d–1 | [51] |

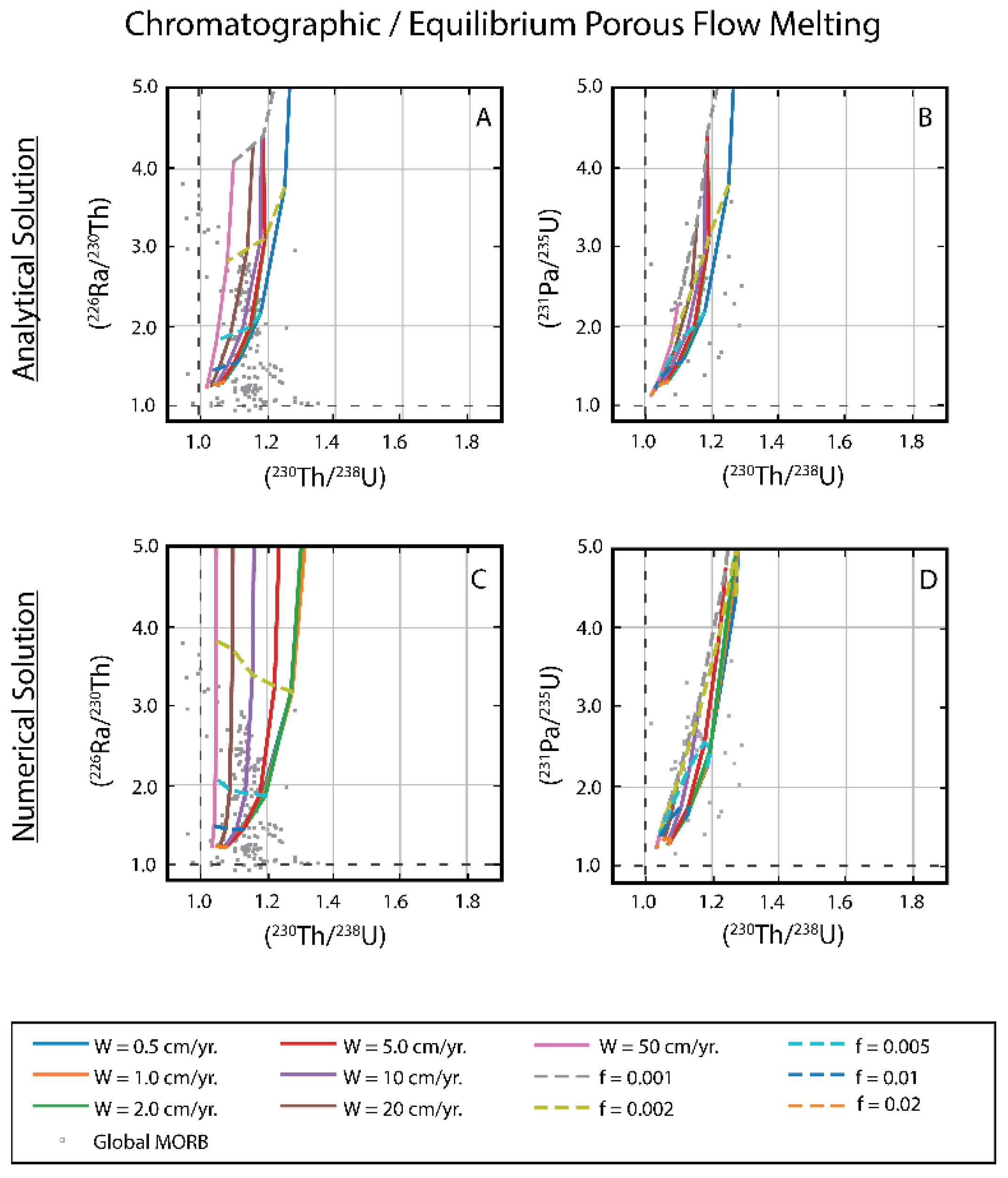

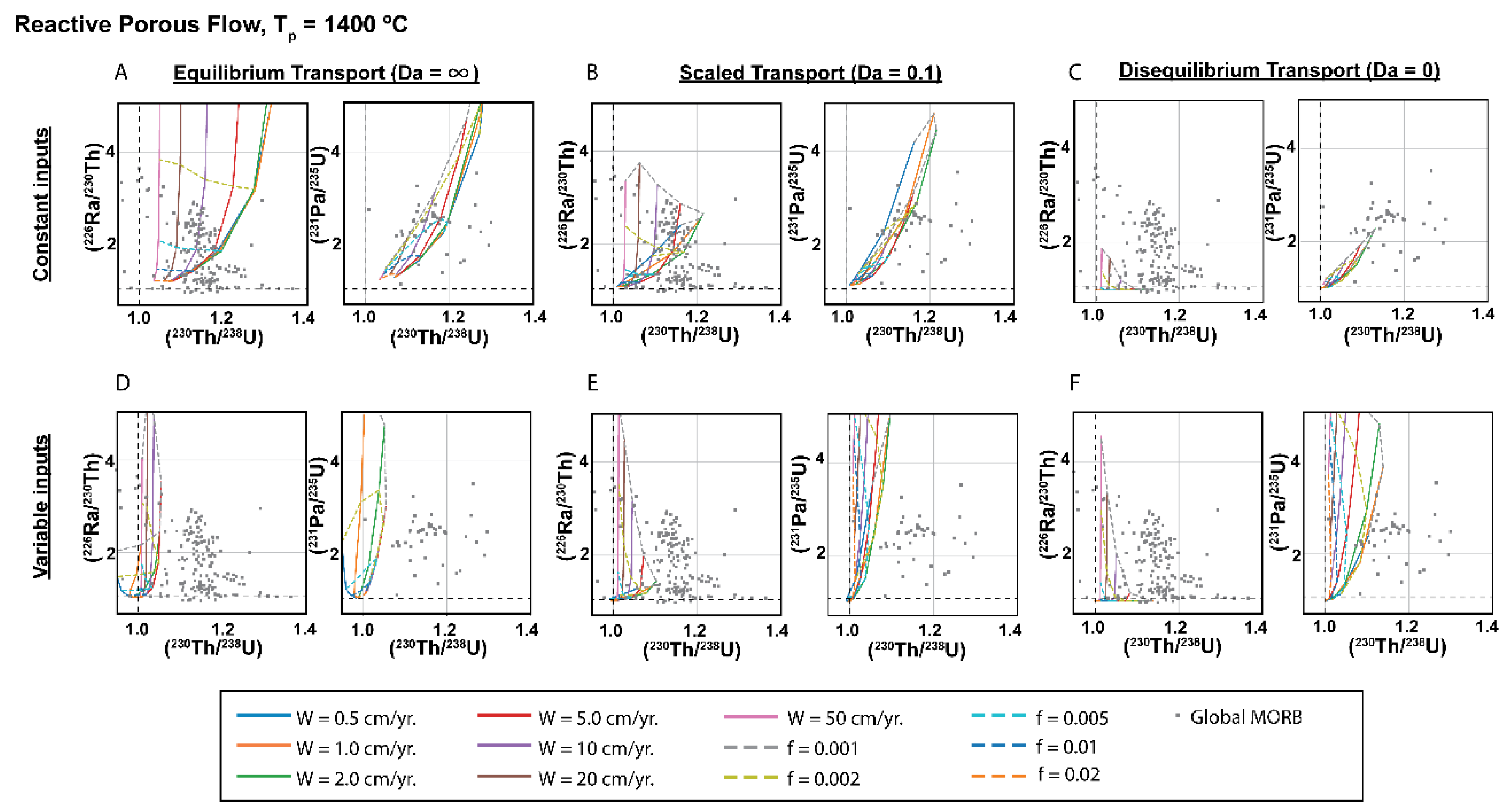

3.3. Chromatographic Porous Flow Melting

| Parameters | Notation | Units | Range |

| Degree of melting | F | --- | 0-0.2 |

| Solid upwelling rate (1D) | W | m·yr-1 | 0-1 |

| Melting rate | Γ | kg·m-3·yr-1 | 10−3 to 10−5 |

| Solidus temperature | T | K | 1000-1400 |

| Length of melting column | Z | km | 0-150 |

| Plate velocity | --- | m·yr-1 | 0.01-0.1 |

| Matrix porosity | φ | --- | 0-0.05 |

| Solid density | ρs | kg·m−3 | 3300 |

| Melt density | ρf or ρm | kg·m−3 | 2800 |

| Melt velocity (1D) | ω | m·yr-1 | |

| Lithosphere thickness | h | km | 0-100 |

| Decay Constants | λ | yr-1 | >10-1 to 10-11 |

| Bulk Partition Coefficient | Di | --- | 0.00001 to 0.1 |

| Buoyancy flux | B | Mg·s-1 | 0.5-9 |

3.1.1. Comparison of Analytical Solutions with the Full Numerical Solution for Chromatographic Porous Flow Melting

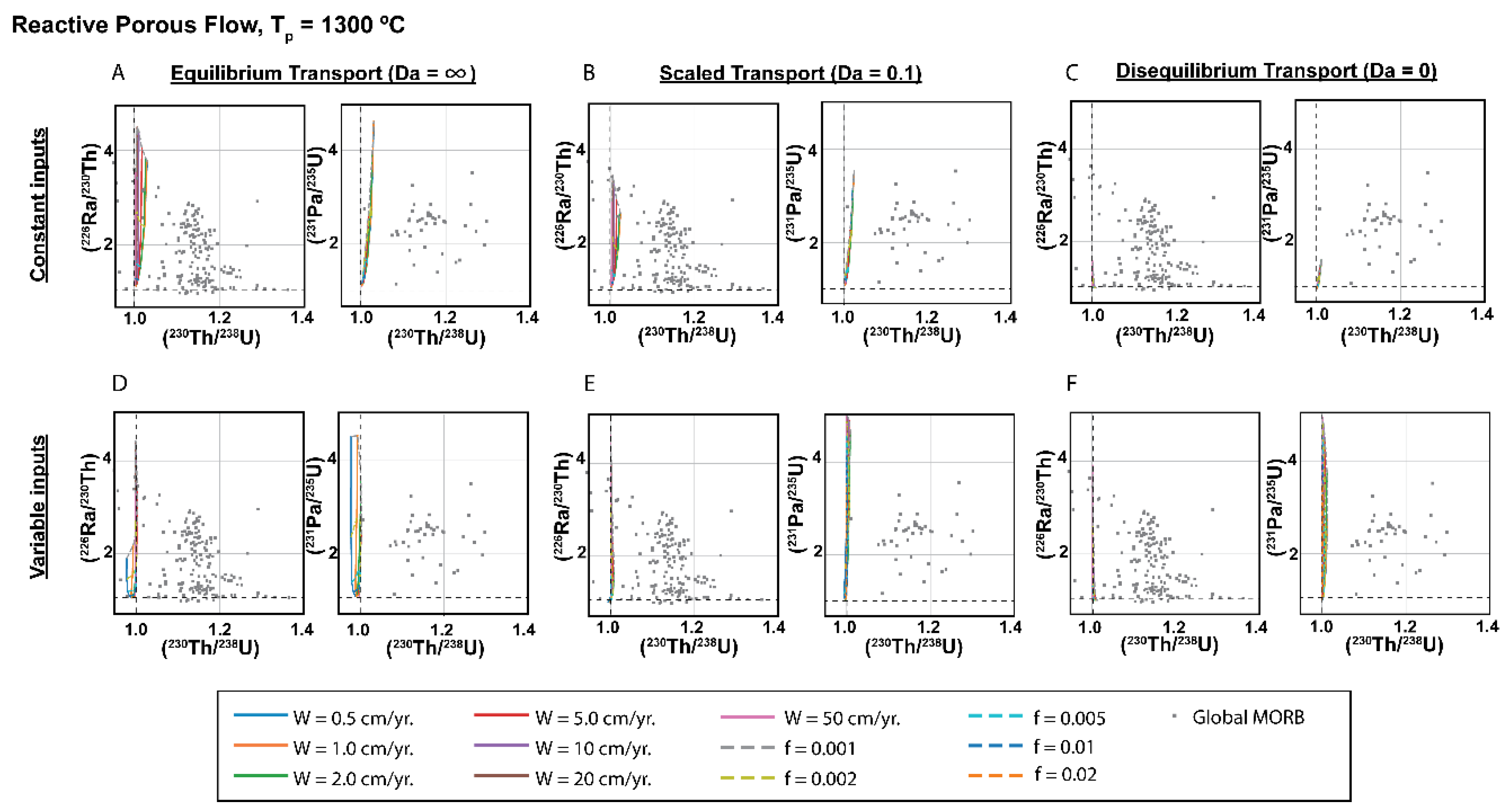

3.4. Dynamic versus Chromatographic Melting: Comparison of the Two Types of Time-Dependent Models

| Lithology | Phase | DU | DTh | DPa * | DRa * | Reference |

| Garnet Peridotite | Garnet | 0.038 | 0.017 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-5 experiment, [73] |

| KG1 Pyroxenite | Clinopyroxene | 0.0030 | 0.0040 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-5 experiment, [73] |

| Olivine | 0.00005 | 0.00047 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-5 experiment, [73] | |

| Orthopyroxene | 0.0078 | 0.0086 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | TM0500-3 experiment, [73] | |

| Pigeonite | 0.00050 | 0.00018 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | W&P 122-1 experiment, [74] | |

| Spinel | 0.012 | 0.0024 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Lunar basalt, [75] | |

| Spinel Peridotite | Cpx | 0.0080 | 0.0070 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | TM 1094-9 experiment, [76] |

| Olivine | 0.00005 | 0.00047 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-5 experiment, [73] | |

| Orthopyroxene | 0.0024 | 0.0027 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-2 experiment, [73] | |

| Plagioclase | 0.0006 | 0.0034 | 0.00001 | 0.02000 | DU, DTh calculated after [54]; DRa from [77] | |

| Pigeonite | 0.0005 | 0.00018 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | W&P 122-1 experiment, [74] | |

| Spinel | 0.012 | 0.0024 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Lunar basalt, [75] | |

| G2 Pyroxenite | Garnet | 0.02405 | 0.00415 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | A343 experiment, [78] |

| Clinopyroxene | 0.0041 | 0.0032 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | A343 experiment, [78] | |

| Olivine | 0.00005 | 0.00047 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-5 experiment, [73] | |

| Orthopyroxene | 0.0078 | 0.0086 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | TM0500-3 experiment, [73] | |

| Plagioclase | 0.0006 | 0.0034 | 0.00001 | 0.02000 | DU, DTh calculated after [54]; DRa from [77] | |

| Pigeonite | 0.0096 | 0.010 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Experiment 18, [79] | |

| Spinel | 0.046 | 0.016 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Maximum measured, [80] | |

| MIX1G, m7-16 | Garnet | 0.013 | 0.0032 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Experimental results, [80] |

| Pyroxenite | Clinopyroxene | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Experimental results, [80] |

| Olivine | 0.00005 | 0.00047 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | RD 1097-5 experiment, [73] | |

| Spinel | 0.046 | 0.016 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Maximum measured, [80] | |

| Orthopyroxene | 0.0078 | 0.0086 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | TM0500-3 experiment, [73] | |

| Plagioclase | 0.0006 | 0.0034 | 0.00001 | 0.02000 | DU, DTh calculated after [54]; DRa from [77] | |

| Pigeonite | 0.0096 | 0.010 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | Experiment 18, [79] |

3.5. Sources of Uncertainty in Melting Models

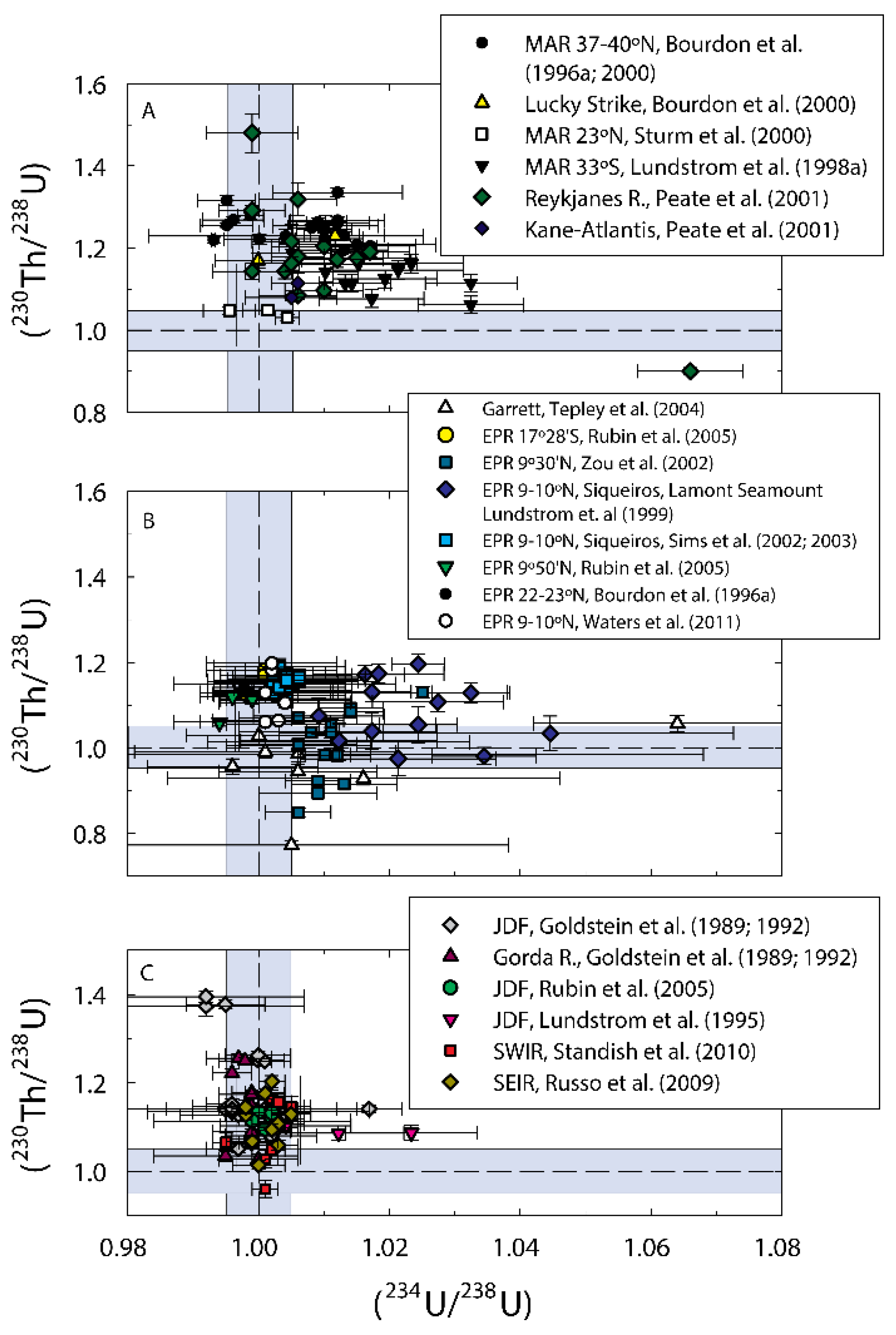

3.5.1. Uncertainties Introduced by the Modification of Lava Compositions by Post-eruptive Contamination

3.5.2. Uncertainties in Sample Ages and Magma Storage Times

3.5.3. Uncertainties in Measured U, Th, Ra Partition Coefficients

3.5.4. Modification of Magma Compositions by Assimilation

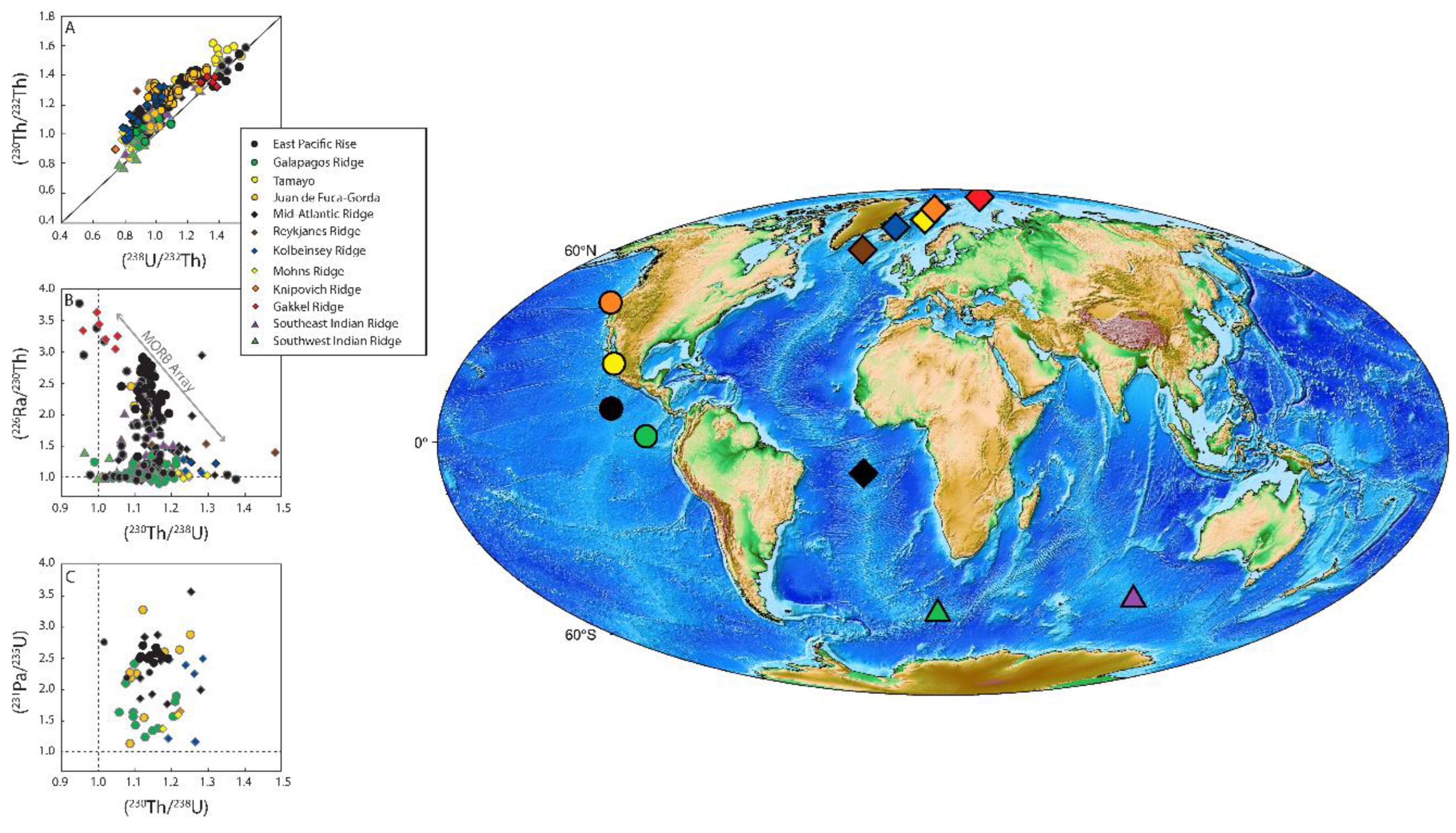

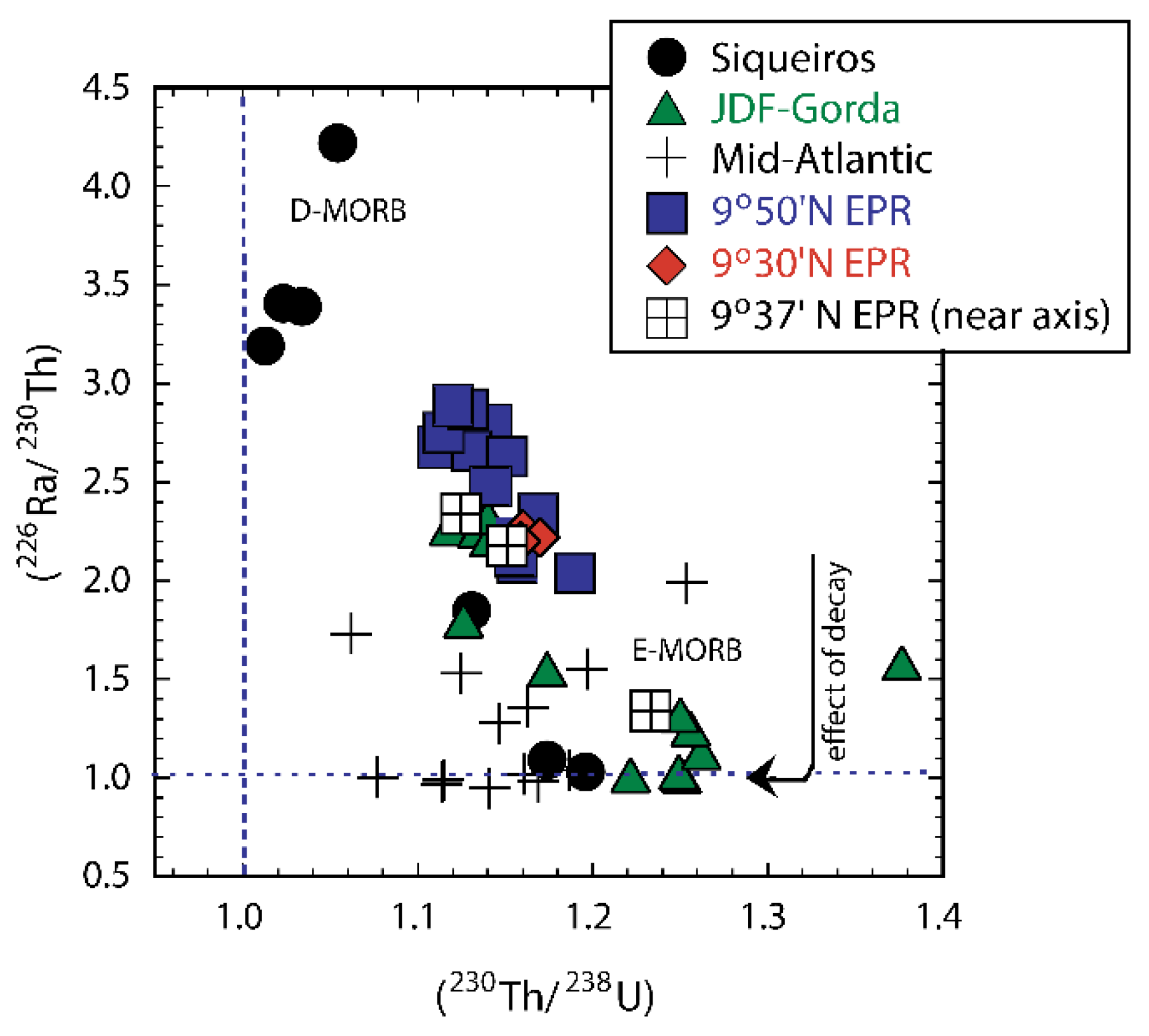

3.6. Mid-Ocean Ridge Basalts (MORB)

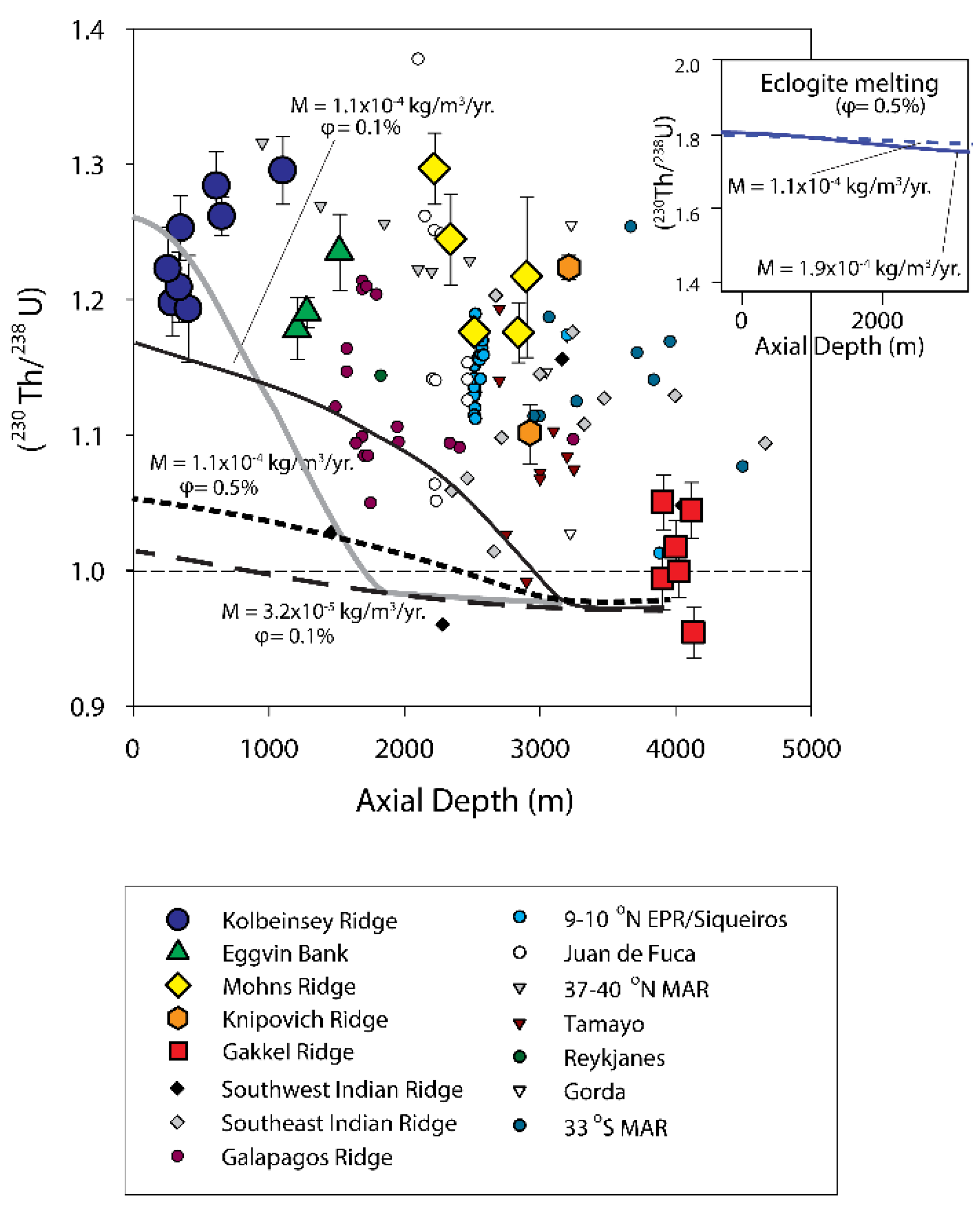

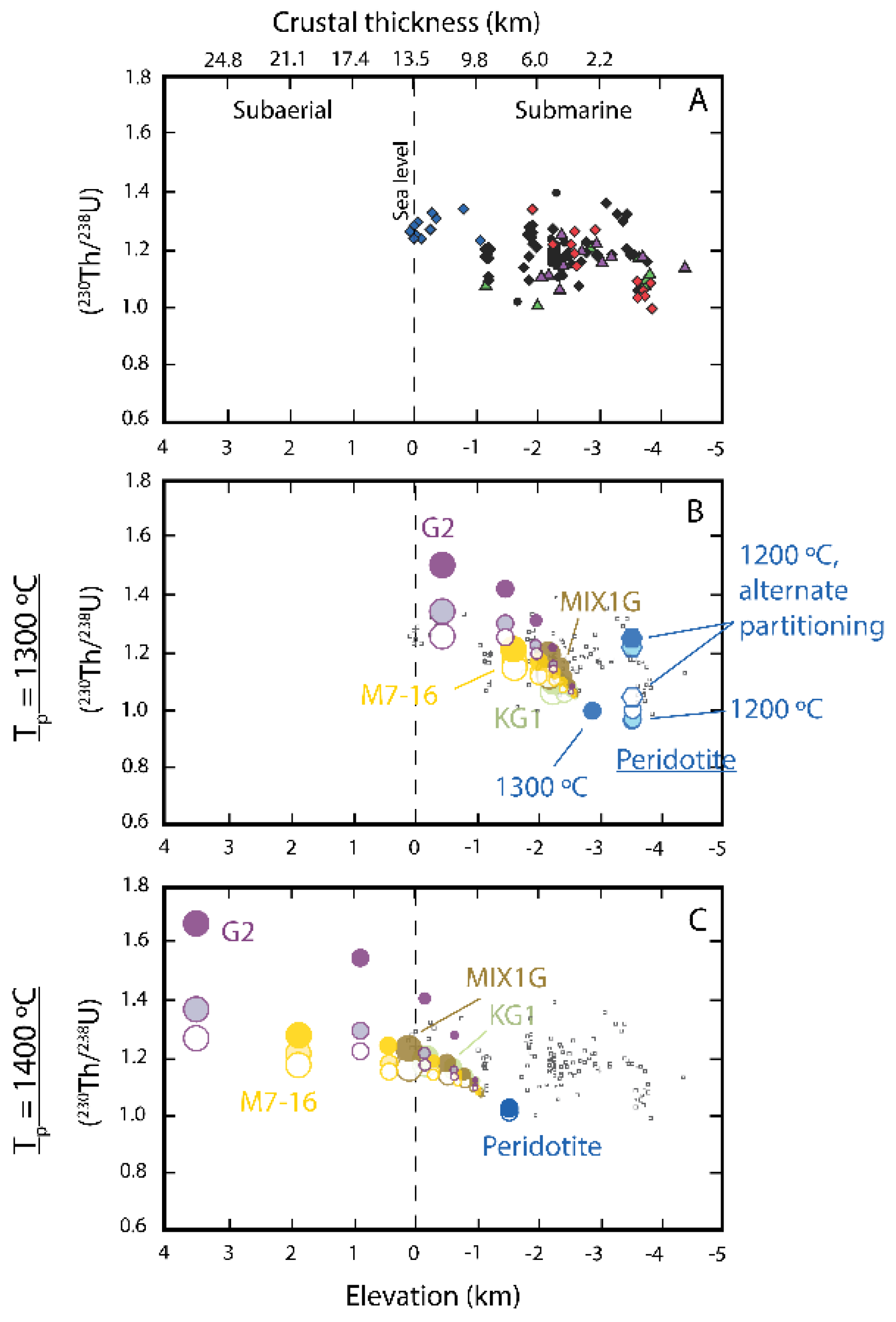

3.6.1. Global Correlation of (230Th/238U) with Ridge Axial Depth

3.6.2. Two-Porosity Modeling

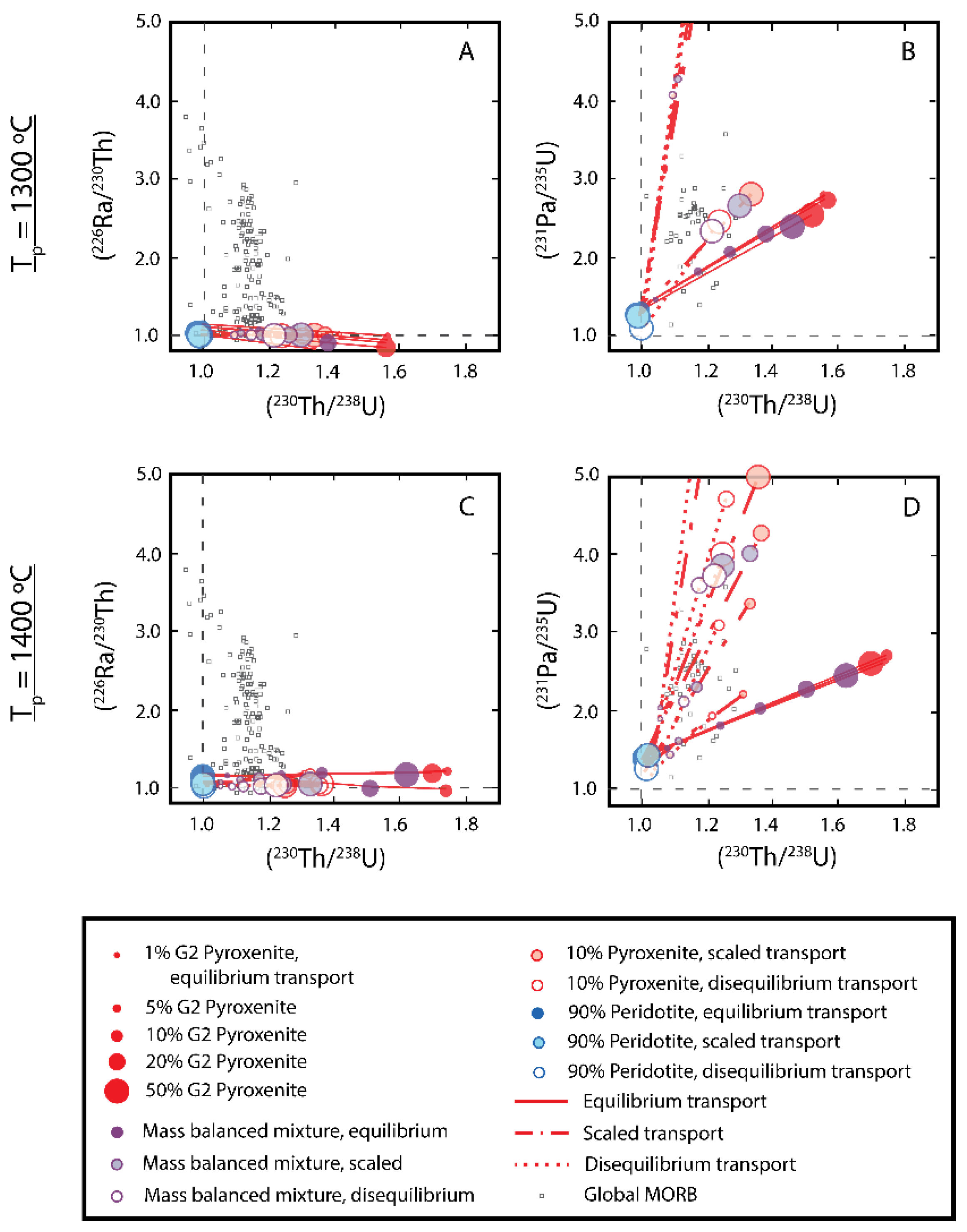

3.6.3. Effects of Source Heterogeneity on U-series Disequilibria in MORB

3.6.4. U-series Techniques for Deciphering the Origins of MORB

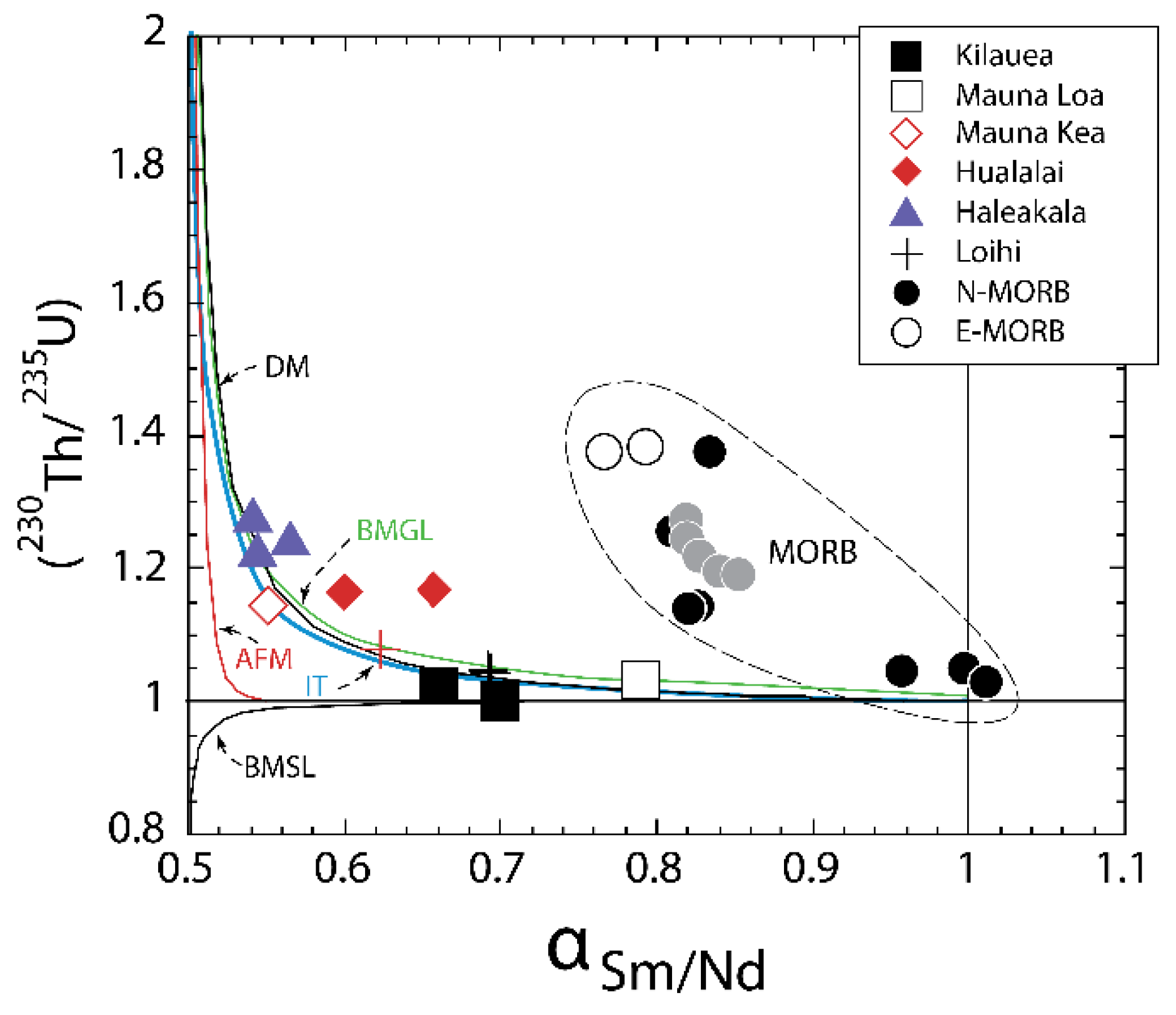

3.7. Ocean Island Basalts (OIB)

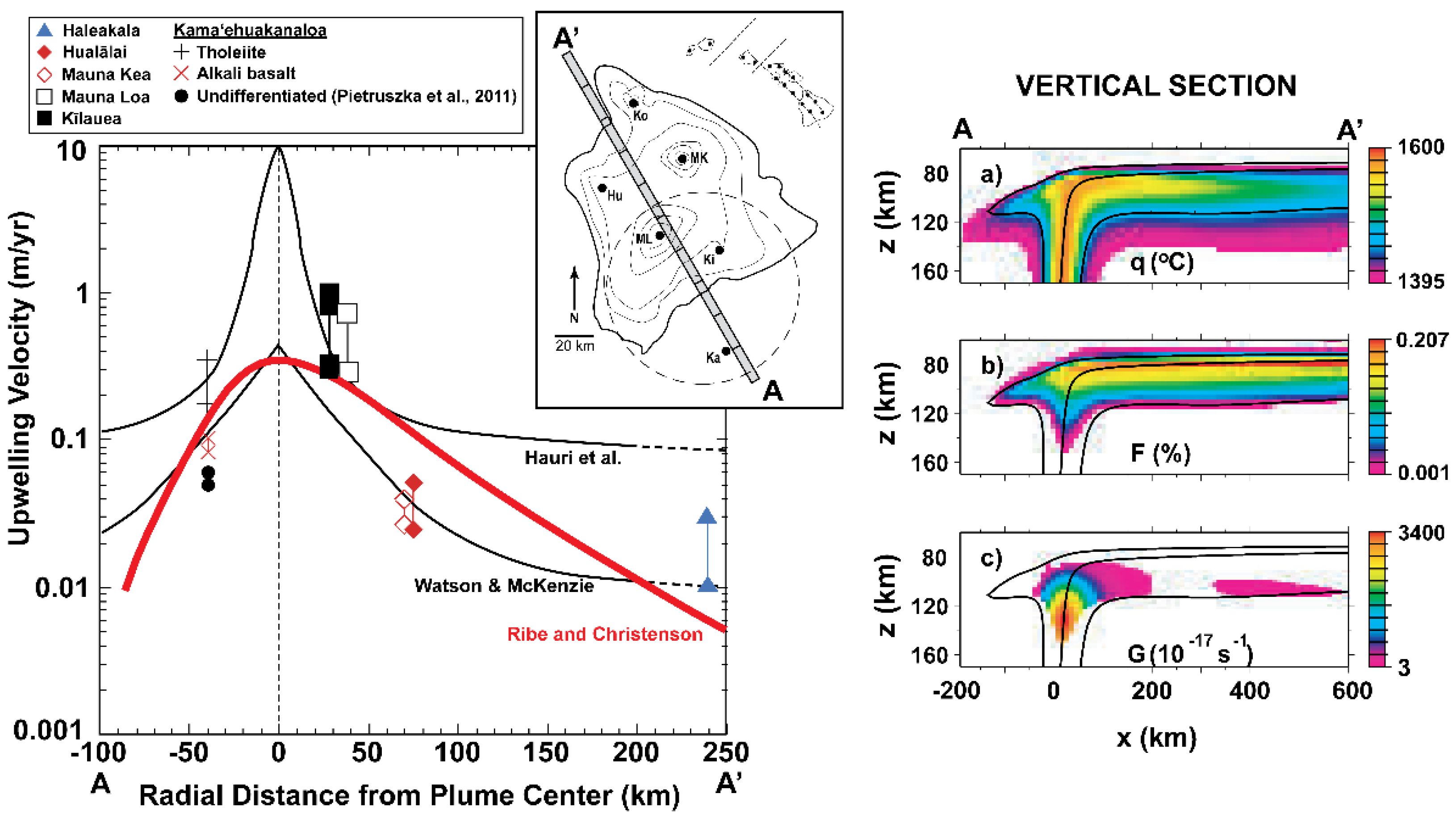

3.7.1. Using U-series Disequilibria to Evaluate Upwelling in Mantle Plumes

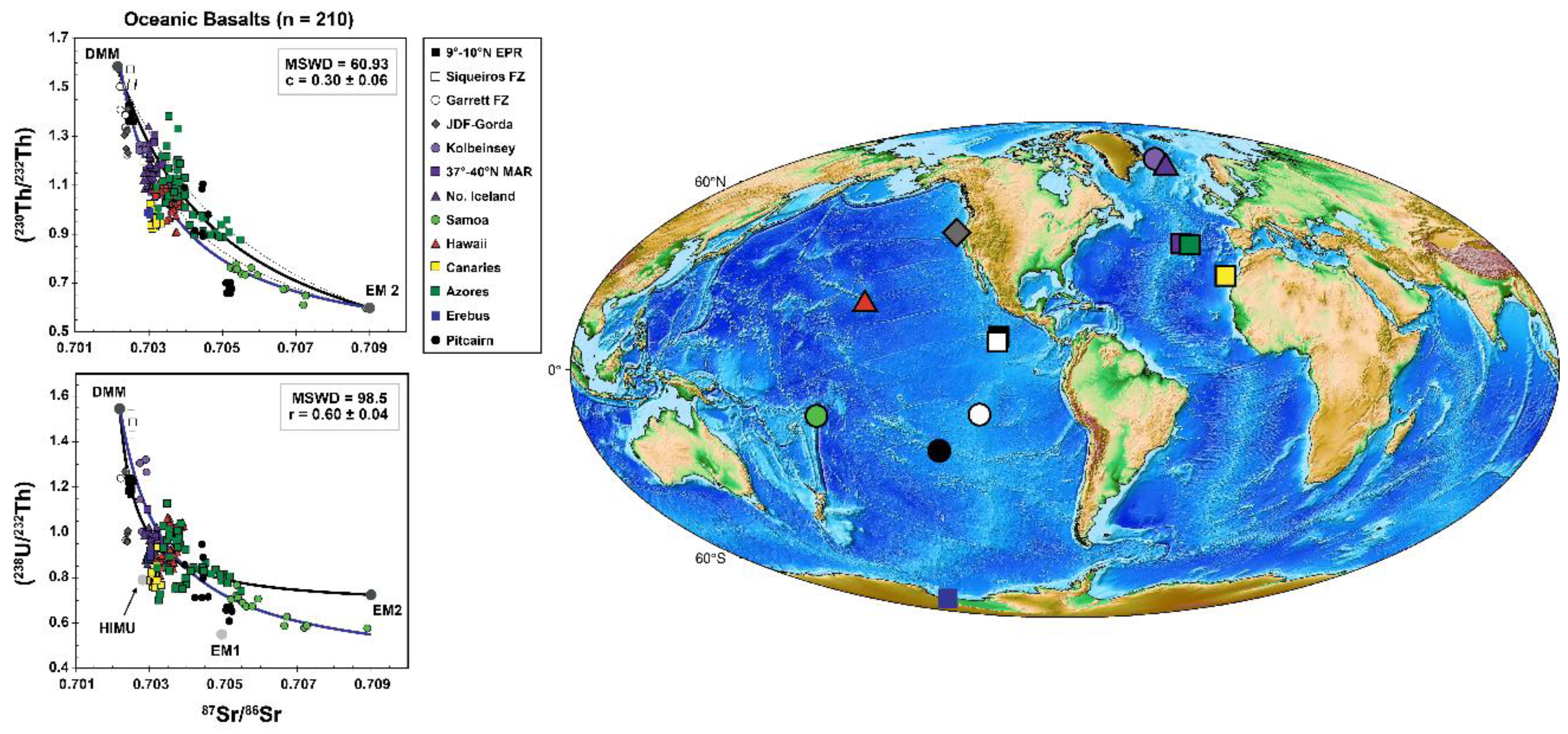

3.8. Global Correlations of U-Th Disequilibria with Radiogenic Isotopes in OIB and MORB

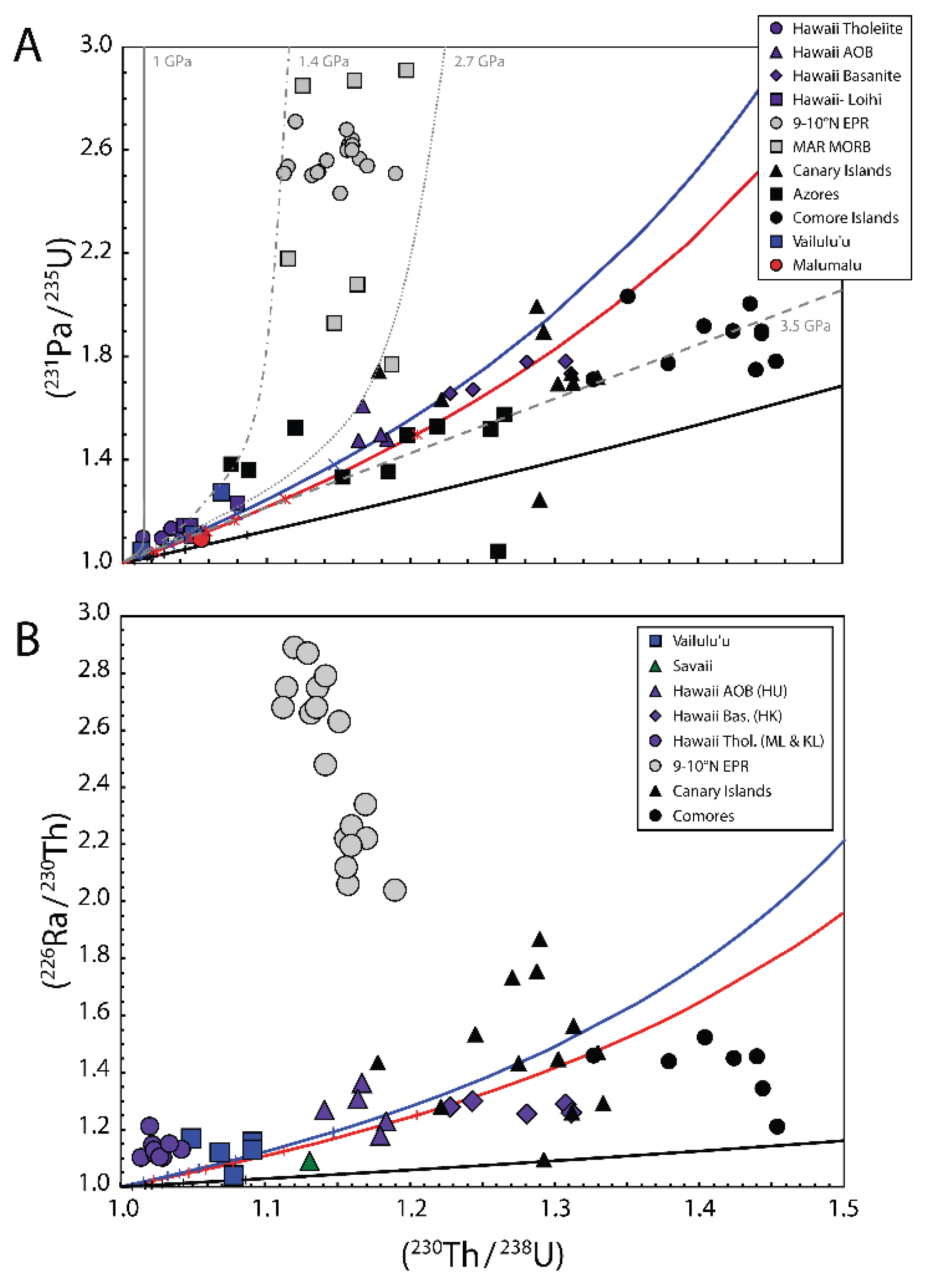

3.9. Average Depths of Mantle Melting from (231Pa/235U) and (230Th/238U) in MORB and OIB

3.10. A Final Comment on Time-Independent Melting versus Time-Dependent Melting in MORB and OIB

4. Principles and Applications of U and Th Decay Series for Dating Eruptions of Unknown Age Lavas

4.1. Establishing Lava Eruption Age Limits Based on the Presence or Absence of U-Series Disequilibria

| Nuclide Pair | Age Constraint |

| 210Po/210Pb ≠ 1 | < 2 yr |

| 210Pb/226Ra ≠ 1 | < 100 yr |

| 226Ra/230Th ≠ 1 | < 8 kyr |

| 231Pa/235U ≠ 1 | < 160 kyr |

| 230Th/238U ≠ 1 | < 375 kyr |

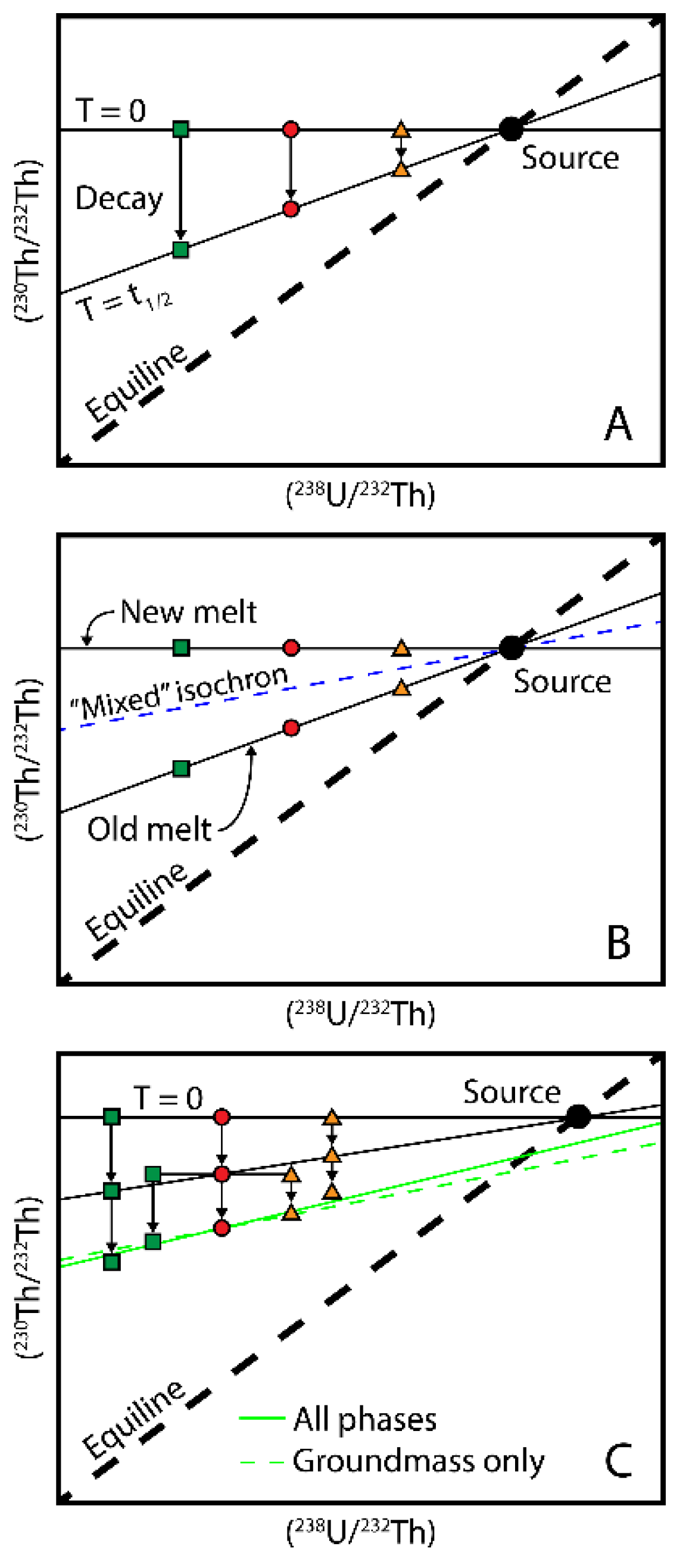

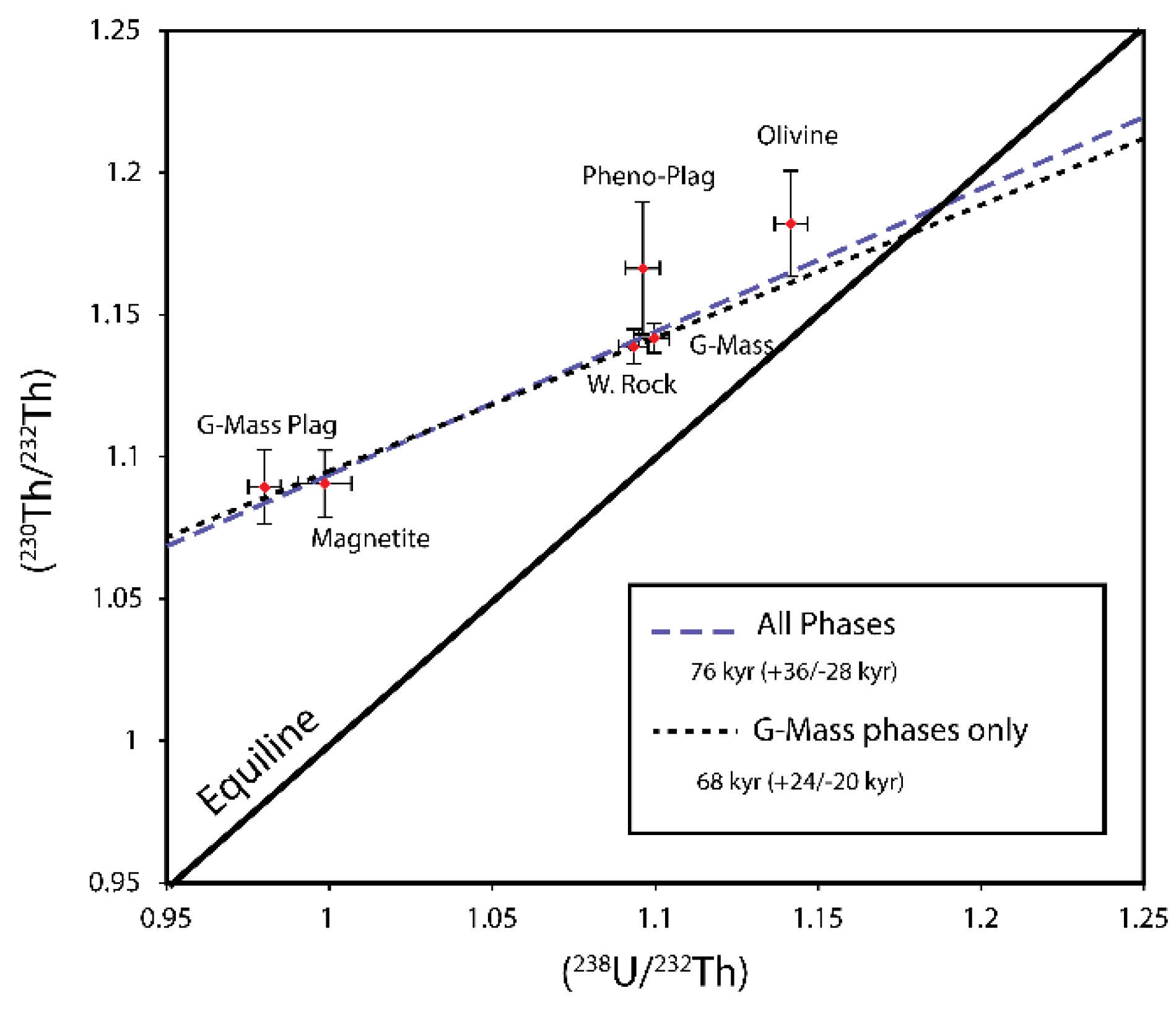

4.2. Internal Mineral Isochron Method

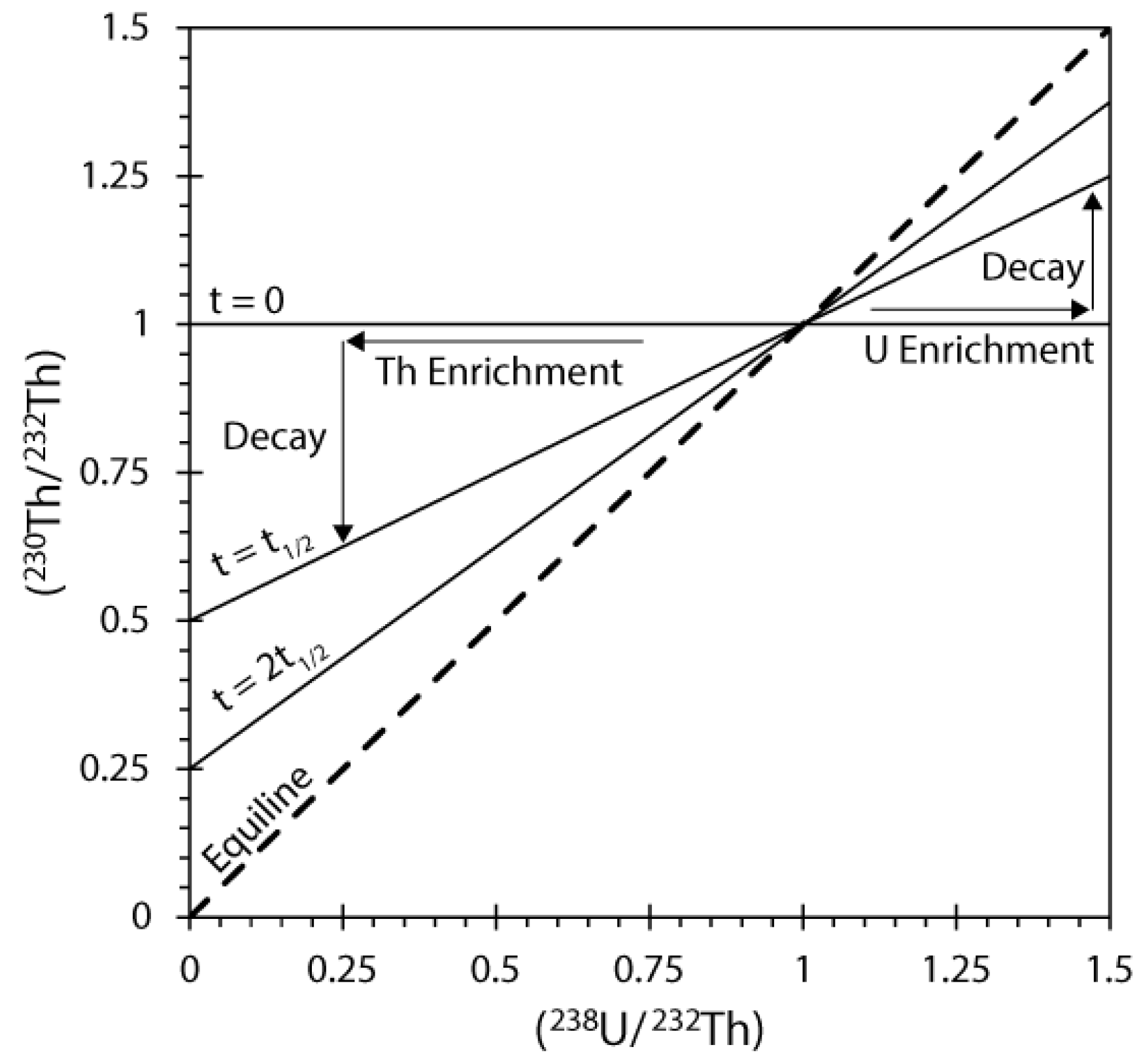

4.2.1.(238. U)/(232Th) - (230Th)/(232Th)

4.2.2.(230. Th)/Ba - (226Ra)/Ba Isochrons

4.3. U-Th-Ra ‘Model’ Ages

- U-series disequilibria were initially created by primary magmatic processes and the lavas being dated have not undergone significant secondary alteration. The lavas have remained a closed system with respect to Th/U, Ra/Th, and Pa/U after eruption.

- After melt generation and transport, the magma has not resided in a magma chamber for periods of time that are significant relative to the half-lives of 230Th, 231Pa, and 226Ra. If it has, then the determined age will be the sum of the integrated crustal residence time and the age of the lava, as the disequilibria is assumed to have been initiated by a melting process, which is when the radiometric clock was started. Furthermore, if a magma chamber is filled repeatedly and slowly with respect to the half-life of the geochronometer nuclide, then the age of the erupted lava will be the sum of the integrated magma residence time and the time since eruption,

- The initial extent of disequilibria in all lavas under consideration is the same, which requires the sources of all lavas to have constant Th/U, Ra/Th, and Pa/U. This further requires that lavas were generated by similar degrees of melting at similar depths of melting from a relatively homogenous mantle source that had not recently lost partial melts. It also requires that all melts have similar transport rates (e.g., [20,45,46,107]).

4.4. Dating Young Volcanic Rocks with 226Ra-210Pb

4.4. Dating Young Volcanic Rocks with 210Po-210Pb

- In a study of lavas from Vailulu’u and Malumalu in Samoa, Sims et al. [35] demonstrate that the calculated 210Po age, which provides an eruption date of 8 November, 2004 (+62 days/-67 days), falls within a window of bathymetric imaging showing new dome growth occurring sometime between March 1999 and April 2005 (Figure 33).

- In a study of the EPR, Tolstoy et al. [234] found a 2+ year buildup of seismic activity preceding a sudden drop in seismic activity on 22 January, 2006. While this event was interpreted as a singular eruption along the East Pacific Rise, the 210Po dates in lava samples from this event show a wider range of eruption dates, from June 2005 to January 2006 [234]. The apparent discrepancy between the calculated ages and seismic observations is controversial; however, a simple interpretation that reconciles this discrepancy is that the 210Po ages may reflect the buildup of seismic activity representing numerous smaller, distant eruptive events rather than precursors to a singular eruptive event.

5. Timescales of Magma Degassing

5.1. Magma Degassing in Ocean Ridge Settings

5.2. Magma Degassing in Ocean Island Plume Settings

5.2.1. Kilauea

5.2.2. Tristan de Cunha

5.2.3. Mount Erebus Volcano

6. Brief Overview of Techniques for Measuring U-Series Nuclides in Oceanic Volcanic Rocks

- Because the equilibrium abundances of the U and Th decay series nuclides are proportional to their respective half-lives (a=λn, where a=activity, λ= ln(2)/half-life, and n=number of atoms), the short-lived progeny of 232Th, 238U, and 235U occur in very low concentrations. For example, in most oceanic basalts, 232Th and 238U are generally found in weight concentrations of ng/g to ug/g, 234U and 230Th in concentrations of pg/g, 226Ra in concentrations of fg/g, and 228Ra and 210Pb in concentrations of ag/g.

- Isotope ratios involving long-lived and short-lived nuclides are often quite extreme as the equilibrium atomic ratios of the various elements are set by the ratio of their decay constants; as such the measured ratios are typically on the order of 10-5 for 234U/238U, 10-6 for 230Th/232Th, 10-3 for 226Ra/228Ra, and 10-8 for 210Pb/208Pb.

7. Summary

- Defining the timescales of magma genesis during decompression mantle melting. The formation and transport of basaltic magma in the mantle during adiabatic decompression can be characterized in terms of the velocity of the upwelling solid mantle, the rate of melting, the melt velocity, melt transport processes (time scale, focused and diffuse, closed or open system), and the delay time, or storage time, of magma before eruption. While the velocity of upwelling mantle and the corresponding melting rate can be estimated from models coupled with thermodynamic data and geophysical observations (e.g., [23,24,150,267]), the melt velocity and magma storage times are difficult to estimate from first principles and require measurement. Fortunately, because the daughter isotopes 230Th and 226Ra of the 238U decay series and the daughter isotope 231Pa of the 235U decay series have half-lives that bracket the timescales over which melting and melt extraction are thought to occur, measurements of (230Th/238U), (226Ra/230Th), and (231Pa/235U) ratios in young basaltic lavas provide unique information on the timescales and modes of melt generation and transport.

- Determining the eruption ages of oceanic Quaternary volcanism. Without lava ages it is not possible to relate volcanic activity to tectonics processes, establish the timing and duration of changes in lava compositions, and link hydrothermal and biological activities to fluctuations in submarine and subaerial oceanic volcanism. Thus, age constraints are not a detail, they are necessary. Without them, our understanding of oceanic systems will remain limited. Dating young submarine lavas has proven to be notoriously difficult – long-lived radiogenic isotope systems such as Rb-Sr, Sm-Nd, Lu-Hf, and U-Th-Pb have half-lives that are too long and hence lack the temporal resolution for precise ages; cosmogenic age dating on the ocean floor is not possible; potassium-argon dating techniques suffer from a myriad of problems when applied to young oceanic basalts; and sedimentation rates are known to vary widely over short spatial scales. Thus, the visual appearance of lavas provides only a subjective, semi-quantitative estimate of age [268]. Fortunately, 238U and 232Th decay series disequilibria can provide robust constraints on the eruption ages of young oceanic basalts. The application of the 238U, 235U, and 232Th for dating eruption ages of volcanic rocks uses three different approaches: 1) age limits, whereby the absence or presence of disequilibria can place bounds on the eruption age of a lava; 2) internal mineral isochron methods, which establish the crystallization age of a volcanic rock; and 3) U-Th-Ra 'model' ages, which couple measurements of U and Th disequilibria with geological, geochemical, and isotopic constraints to estimate the eruption age of an individual lava or a sequence of lavas.

- Establishing the timescales of magma recharge and degassing. Processes operating within magma reservoirs affect both the physical state and the chemical composition of magmas within them. Measurements of (210Po), (210Pb), and (210Bi) in gas emissions from actively degassing open-conduit systems and (210Pb)/(226Ra) and (228Ra/228Th) in young known-age erupted lavas provide otherwise unobtainable constraints on the timescales of magma recharge and degassing. These timescales are directly linked to a volcano’s activity and are thus fundamental to our understanding of physical eruption dynamics and hazard assessment.

References

- Bourdon, B.; Henderson, G.M.; Lundstrom, C.C.; Turner, S. Uranium-Series Geochemistry, Vol. 52; Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, D.C., United States, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, H. The solution of a system of differential equations occurring in the theory of radioactive transformations. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 1910, 15, 423–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovich, M.; Harmon, R.S. Uranium-Series Disequilibrium: Applications to Earth, Marine, and Environmental Sciences, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Stark, G.J.; Reagan, M.R. An Essential Quaternary Clock for Earth System Sciences: An Overview of the Theory and Applications of U and Th Decay Series Isotopes for the Dating of Young Igneous and Sedimentary Rocks. In Encyclopedia of Geology, 2nd ed.; Alderton, D., Elias, S.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, 2021; Volume 6, pp. 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allègre, C.J. 230Th dating of volcanic rocks: a comment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1968, 5, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, S.A.; Buesseler, K.O.; Sims, K.W.W. Re-evaluating the 238U-salinity relationship in seawater: Implications for the 238U-234Th disequilibrium method. Mar. Chem. 2011, 127, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allègre, C.J.; Condomines, M. Basalt genesis and mantle structure studied through Th-isotopic geochemistry. Nature 1982, 299, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; DePaolo, D.J.; Murrell, M.T.; Baldridge, W.S.; Goldstein, S.J.; Clague, D.A. Mechanisms of magma generation beneath Hawaii and mid-ocean ridges: Uranium/thorium and samarium/neodymium isotopic evidence. Science 1995, 267, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T.R. Fractionation of U and Th during mantle melting: A reprise. Chem. Geol. 1997, 139, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D. The generation and compaction of partially molten rock. J. Petrol. 1984, 25, 713–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.W.; Gill, J.B. Effects of partial melting on the uranium decay series. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 1607–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, M.; Elliott, T. Consequences of melt transport for uranium series disequilibrium in young lavas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1993, 118, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, C.C.; Gill, J.; Williams, Q.; Perfit, M.R. Mantle melting and basalt extraction by equilibrium porous flow. Science 1995, 270, 1958–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D. 230Th-238U disequilibrium and the melting processes beneath ridge. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1985, 72, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.W. Disequilibrium partial melting model and its implications for trace element fractionations during mantle melting. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1992, 112, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.W. Dynamics of melt generation beneath midocean ridge axes-theoretical analysis based on 238U-230Th-226Ra and 235U-231Pa disequilibria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1993, 57, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamori, H. 238U-230Th-226Ra and 235U-231Pa disequilibria produced by mantle melting with porous and channel flows. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1994, 125, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.; McKenzie, D. Radioactive disequilibria from 2D models of melt generation by plumes and ridges. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1994, 128, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; DePaolo, D.J.; Murrell, M.T.; Baldridge, W.S.; Goldstein, S.; Clague, D.; Jull, M. Porosity of the melting zone and variations in the solid mantle upwelling rate beneath Hawaii: Inferences from 238U-230Th-226Ra and 235U-231Pa disequilibria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 4119–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Goldstein, S.J.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Perfit, M.R.; Kelemen, P.; Fornari, D.J.; Michael, P.; Murrell, M.T.; Hart, S.R.; DePaolo, D.J.; Layne, G.D.; Jull, M. Chemical and isotopic constraints on the generation and transport of melt beneath the East Pacific Rise. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 3481–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, A.; Zindler, A.; Salters, V. J.; McKenzie, D.; Grönvold, K. The dynamics of melting beneath Theistareykir, northern Iceland. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2003, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, A.; Bourdon, B.; Mckenzie, D. Melt extraction in the Earth’s mantle: Constraints from U–Th–Pa–Ra studies in oceanic basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 244, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, D.; Bickle, M.J. The volume and composition of melt generated by extension of the lithosphere. J. Petrol. 1988, 29, 625–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimow, P.D.; Hirschmann, M.M.; Stolper, E.M. An analysis of variations in isentropic melt productivity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 1997, 355, 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Hawkesworth, C.; Rogers, N.; King, P. U-Th isotope disequilibria and ocean island basalt generation in the Azores. Chem. Geol. 1997, 139, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Langmuir, C.H.; Zindler, A. Ridge-hotspot interaction along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between 37°30′ and 40°30′N: The U-Th disequilibrium evidence. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1996, 142, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Zindler, A.; Elliott, T.; Langmuir, C. Constraints on mantle melting at mid-ocean ridges from global 238U-230Th disequilibrium data. Nature 1996, 384, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Joron, J.-L.; Claude-Ivanaj, C.; Allègre, C. J. U–Th–Pa–Ra systematics for the Grande Comore volcanics: Melting processes in an upwelling plume. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 164, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosso, L.; Bougault, H.; Langmuir, C.; Bollinger, C.; Bonnier, O.; Etoubleau, J. The age and distribution of mantle heterogeneity along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (31–41 N). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999, 170, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude-Ivanaj, C.; Bourdon, B.; Allègre, C.J. Ra-Th-Sr isotope systematics in Grande Comore Island: a case study of plume-lithosphere interaction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 164, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude-Ivanaj, C.; Joron, J.-L.; Allègre, C.J. 238U-230Th-226Ra fractionation in historical lavas from the Azores : long-lived source heterogeneity vs. Metasomatism fingerprints. Chem. Geol. 2001, 176, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Van Orman, J.A. Melting of enriched mantle beneath Pitcairn seamounts: Unusual U–Th–Ra systematics provide insights into melt extraction processes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 277, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, C.C.; Williams, Q.; Gill, J.B. Investigating solid mantle upwelling rates beneath mid-ocean ridges using U-series disequilibria, 1: a global approach. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 157, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, C.C.; Sampson, D.E.; Perfit, M.R.; Gill, J.; Williams, Q. Insight into mid-ocean ridge basalt petrogenesis: U-series disequilibria from the Siqueiros Transform, Lamont Seamounts, and East Pacific Rise, J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 13035–13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Hart, S.R.; Reagan, M.K.; Blusztajn, J.; Staudigel, H.; Sohn, R.A.; Layne, G.D.; Ball, L.A.; Andrews, J. 238U-230Th-226Ra-210Pb-210Po, 232Th-228Ra, and 235U-231Pa constraints on the ages and petrogenesis of Vailulu’u and Malumalu Lavas, Samoa. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Maclennan, J.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Mervine, E.M.; Bluzstajn, J.; Grönvold, K. Short length scale mantle heterogeneity beneath Iceland probed by glacial modulation of melting. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 379, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.H.; Sims, K.W.W.; Sherrod, D.R.; Salters, V.J.M.; Blusztajn, J.; Dulai, H. Isotopic constraints on the genesis and evolution of basanitic lavas at Haleakala, Island of Maui, Hawaii. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 195, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmarsson, O.; Carn, S.; Carracedo, J.C. Systematics of U-series nuclides in primitive lavas from the 1730–36 eruption on Lanzarote, Canary Islands, and implications for the role of garnet pyroxenites during oceanic basalt formations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 162, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.W.; Gill, J.B. Th isotope and U-series disequilibria in some alkali basalts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1992, 19, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peate, D.W.; Hawkesworth, C.J.; van Calsteren, P.W.; Taylor, R.N.; Murton, B.J. 238U-230Th constraints on mantle upwelling and plume-ridge interaction along the Reykjanes Ridge. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 187, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.E.; Goldstein, S.J.; Klein, E.M.; Karson, J.A.; Murrell, M.T. Uranium-series age constraints on lavas from the axial valley of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, MARK area. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2000, 181, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepley, F.J. III; Lundstrom, C.C.; Sims, K.W.W.; Hékinian, R. U-series disequilibria in MORB from the Garrett Transform and implications for mantle melting. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004, 223, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Sims, K.W.W.; Prytulak, J.; Elliott, T.; Mattielli, N.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Blusztajn, J.; Devey, C.; Mertz, D.; Schilling, J.-G.; M. Murrell. Understanding melt generation beneath the slow-spreading Kolbeinsey Ridge using 238U, 230Th, and 231Pa excesses. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2011, 75, 6300–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, C.L.; Sims, K.W.W.; Perfit, M.R.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Blusztajn, J. Perspective on the genesis of E-MORB from Chemical and Isotopoic Heterogeneity at 9-10°N East Pacific Rise. J. Petrol. 2011, 52, 565–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, C.L.; Sims, K.W.W.; Klein, E.M.; White, S.M.; Reagan, M.K.; Girard, G. Sill to Surface: Linking Young Off-Axis Volcanism with Subsurface Melt at the Overlapping Spreading Center at 9°03’N East Pacific Rise. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 369, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, C.L.; Sims, K.W.W.; Soule, S.A.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Dunbar, N.W.; Plank, T.; Sohn, R.A.; Tivey, M.A. Recent Volcanic Accretion at 9-10°N East Pacific Rise as Resolved by Combined Geochemical and Geological Observations. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2013, 14, 2547–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zindler, A. Constraints on the degree of dynamic partial melting and source composition using concentration ratios in magmas. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffey, A.H.; Flynn, K.F.; Glendenin, L.E.; Bentley, W.C.; Essling, A.M. Precision Measurement of Half-Lives and Specific Activities of 235U and 238U. Phys. Rev. C 1971, 4, 1889–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Shen, C.C.; Polyak, V.J.; Asmerom, Y.; Woodhead, J.; Hellstorm, J.; Yongjin, W.; Kong, X.; Spötl, C.; Wang, X.; Alexander Jr, E.C. Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 371, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, J.K. Nuclear Wallet Cards, National Nuclear Data Center. Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, 2000.

- Holden, N.E. Total half-lives for selected nuclides. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990, 62, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, J.; Miranda, C.F.; Muxart, R. Mesure de la période du protactinium 231 par microcalorimétrie. Radiochim. Acta 1969, 11, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, L.A.; Glendenin, L.E. Half-life of 232Th. In Proceedings of the National Meeting on Nuclear Energy (Vol. 83, p. 94), Pretoria, South Africa, April 1963.

- Blundy, J.D.; Wood, B.J. Mineral-Melt Partitioning of Uranium, Thorium and Their Daughters. In U-series Geochemistry; Bourdon, B., Lundstrom, C., Henderson, G., Turner, S.P., Eds.; Eds., Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, D.C., United States, 2003; pp. 59–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, M. UserCalc: A Web-based uranium series calculator for magma migration problems. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Spiegelman, M. pyUserCalc: A revised Jupyter Notebook calculator for uranium-series disequilibria in basalts. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimow, P.D. Calculation of peridotite partial melting from thermodynamic models of minerals and melts, IV. Adiabatic decompression and the composition and mean properties of mid-ocean ridge basalts. J. Petrol. 2001, 42, 963–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, P. The generation of uranium series disequilibria by partial melting of spinel peridotite: constraints from partitioning studies. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1993, 117, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, P. Uranium-thorium disequilibria and partitioning on melting of garnet peridotite. Nature 1993, 363, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTourette, T.Z.; Burnett, D.S. Experimental determination of U and Th partitioning between clinopyroxene and synthetic basaltic liquid. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1992, 110, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTourrette, T.Z.; Kennedy, A.K.; Wasserburg, G. J. Thorium-uranium fractionation by garnet: evidence for a deep source and rapid rise of oceanic basalts. Science 1993, 261, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, C.C.; Shaw, H.F.; Ryerson, F.J.; Phinney, D.L.; Gill, J.B.; Williams, Q. Compositional controls on the partitioning of U, Th, Ba, Pb, Sr and Zr between clinopyroxene and haplobasaltic melts: implications for uranium series disequilibria in basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1994, 128, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehr, D.; Blundy, J.; Chamorro-Perez, E.; Hill, E.; Wood, B. U-series disequilibria generated by partial melting of spinel lherzolite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 188, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.C. Numerical Methods for Ordinary Differential Equations. John Wiley & Sons: New York, United States, 2003.

- Lambert, J.D. Numerical Methods for Ordinary Differential Systems. Wiley: New York, United States, 1992.

- Hairer, E.; Wanner, G. Solving Ordinary Differential Equations II: Stiff and Differential-Algebraic Problems (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1996.

- Elkins, L.J.; Bourdon, B.; Lambart, S. Testing pyroxenite versus peridotite sources for marine basalts using U-series isotopes. Lithos 2019, 332–333, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Lambart, S. Uranium-series disequilibria in MORB, revisited: A systematic numerical approach to partial melting of a heterogeneous mantle. Volcanica 2024, 7, 685–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krein, S.B.; Behn, M.D.; Grove, T.L. Origins of major element, trace element, and isotope garnet signatures in mid-ocean ridge basalts. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2020, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambart, S. No direct contribution of recycled crust in Icelandic basalts. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 2017, 4, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambart, S.; Baker, M.B.; Stolper, E.M. The role of pyroxenite in basalt genesis: Melt-PX, a melting parameterization for mantle pyroxenites between 0.9 and 5 GPa. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2016, 121, 5708–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiorso, M.S.; Hirschmann, M.M.; Reiners, P.W.; Kress III, V. C. The pMELTS: A revision of MELTS for improved calculation of phase relations and major element partitioning related to partial melting of the mantle to 3 GPa. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2002, 3, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salters, V.J.M.; Longhi., J.E.; Bizimis, M. Near mantle solidus trace element partitioning at pressures up to 3.4 GPa. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2002, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehr, D.; Blundy, J.; Chamorro-Perez, E.; Hill, E.; Wood, B. U-series disequilibria generated by partial melting of spinel lherzolite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 188, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemme, S.; Günther, D.; Hametner, K.; Prowatke, S.; Zack, T. The partitioning of trace elements between ilmenite, ulvospinel, armalcolite and silicate melts with implications for the early differentiation of the moon. Chem. Geol. 2006, 234, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salters, V.J.M.; Longhi, J.E. Trace element partitioning during the initial stages of melting beneath ocean ridges. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999, 166, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizio, A.; Schmidt, M.W.; Günther, D.; Eikenberg, J. Experimental determination of Ra mineral/melt partitioning for feldspars and 226Ra-disequilibrium crystallization ages of plagioclase and alkali-feldspar. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 280, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertermann, M.; Hirschmann, M.M.; Hametner, K.; Günther, D.; Schmidt, M.W. Experimental determination of trace element partitioning between garnet and silica- rich liquid during anhydrous partial melting of MORB-like eclogite. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Westrenen, W.; Blundy, J.; Wood, B. Crystal-chemical controls on trace element partitioning between garnet and anhydrous silicate melt. Am. Mineral. 1999, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Gaetani, G.A.; Sims, K.W.W. Partitioning of U and Th during garnet pyroxenite partial melting: Constraints on the source of alkaline ocean island basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 265, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Kant, L.B.; Stark, G.J.; Reagan, M.K.; Standish, J.J.; Langmuir, C.H. High-resolution decadal-scale eruption age dating of young oceanic basalts at an active hydrothermal vent site. Front. Geochem. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Turner, S.P.; Ribe, N.M. Partial melting and upwelling rates beneath the Azores from a U-series isotope perspective. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 239, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Bourdon, B.; Lambart, S. (2023). Corrigendum to “Testing pyroxenite versus peridotite sources for marine basalts using U-series isotopes” [Lithos 332–333 (2019) 226–244]. Lithos 2023, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, D.L. Anomalous U234/U238 in nature. J. Geophys. Res. 1962, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, T.L.; Mathieu, G.G.; Knauss, K.G. Uranium in open ocean: concentration and isotopic composition. Deep Sea Res. 1977, 24, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.M.; Cohen, A.S.; O'nions, R.K. 234U/238U ratios and 230Th ages for Hateruma Atoll corals: implications for coral diagenesis and seawater 234U/238U ratios. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1993, 115, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.F.; Henderson, G.M.; Hall, L.; Matthews, I. Climatic control of riverine and seawater uranium-isotope ratios. Science 2004, 305, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulaiova, H.; Sims, K.W.W.; Charette, M.A. A new method for the determination of low-level actinium-227 in geological samples. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2013, 296, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

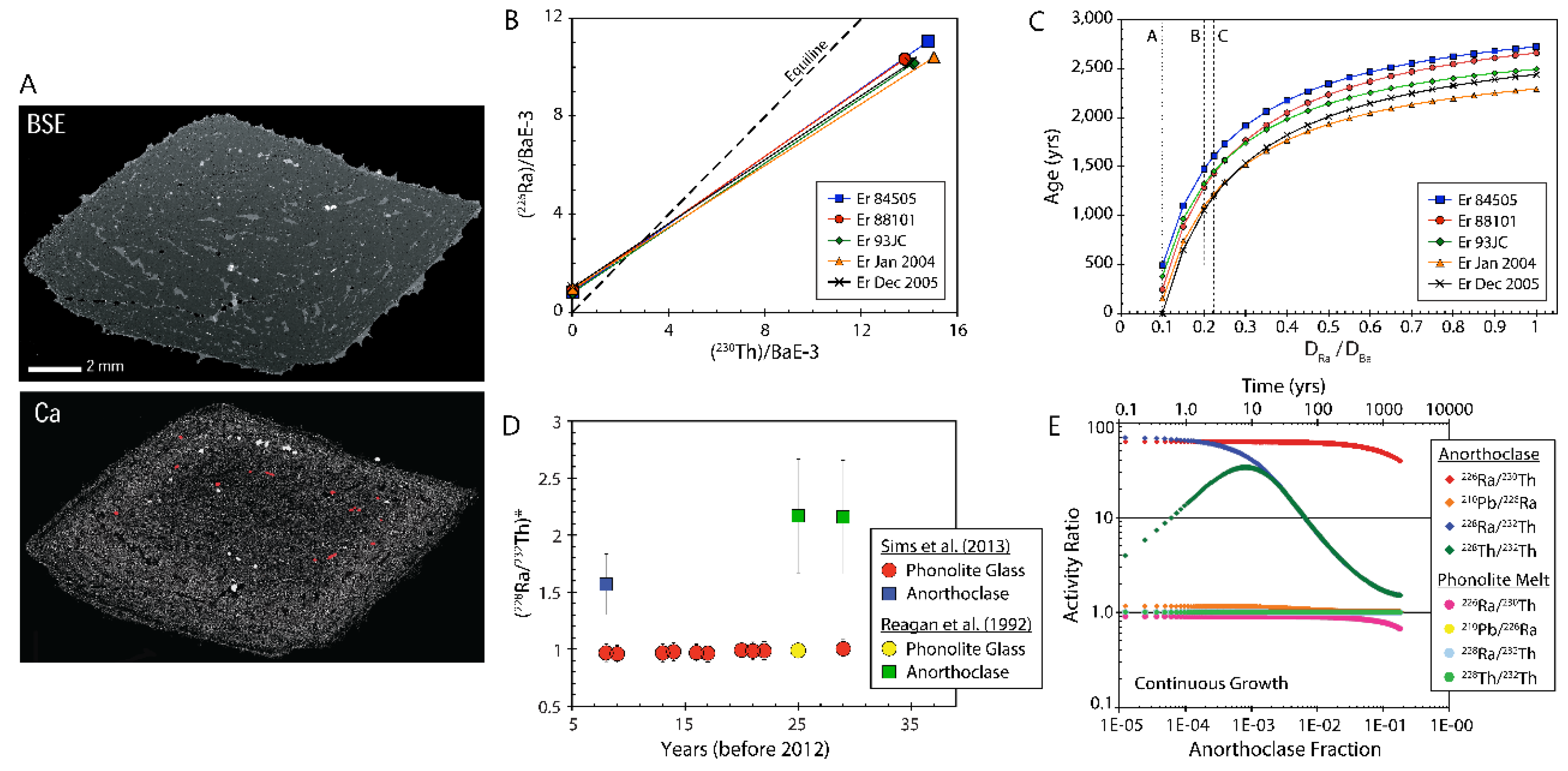

- Sims, K.W.W.; Pichat, S.; Reagan, M.K.; Kyle, P.R.; Dulaiova, H.; Dunbar, N.; Prytulak, J.; Sawyer, G.; Layne, G.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Gauthier, P.J.; Charrette, M.A.; Elliott, T.R. On the timescales of magma genesis, melt evolution, crystal growth rates and magma degassing in the Erebus volcano magmatic system using the 238U, 235U and 232Th-decay series. J. Petrol. 2013, 54, 2–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Aster, R.; Gaetani, G.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Phillips, E.H.; Wallace, P.J.; Mattioli, G.S.; Rasmussen, D.; Boyd, E.S. Mount Erebus Volcano: An Exceptional Natural Laboratory to Study Alkaline Magmatism and Open-Conduit Volcano Behavior. In Volcanism in Antarctica: 200 Million Years of Subduction, Rifting and Continental Break-Up; Smellie, J., Panter, K., Eds.; Geyer, A. Geological Society: London, United Kingdom, 2021; Volume 55, pp. 695–731. [Google Scholar]

- Hiraga, T.; Hirschmann, M.M.; Kohlstedt, D.L. Equilibrium interface segregation in the diopside–forsterite system II: applications of interface enrichment to mantle geochemistry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, T.; Kohlstedt, D.L. Hidden Records Of Critical Melt Fraction? Constant Intergranular Component In Mantle Xenoliths. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, San Francisco, California, United States, December 2007.

- Hiraga, T.; Kohlstedt, D.L. Equilibrium interface segregation in the diopside–forsterite system I: Analytical techniques, thermodynamics, and segregation characteristics Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 1266–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, H.S.C.; Jenner, F.E. The global pattern of trace-element distributions in ocean floor basalts. Nature 2012, 491, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissenberg, C.J.; MacLeod, C.J.; Bennett, E.N. Consequences of a crystal mush-dominated magma plumbing system: a mid-ocean ridge perspective. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2019, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, A.E.; Van Orman, J.A. The 226Ra enrichment in oceanic basalts: Evidence for melt-cumulate diffusive interaction processes within the oceanic lithosphere. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Orman, J.A.; Saal, A.E.; Bourdon, B.; Hauri, E.H. Diffusive fractionation of U-series radionuclides during mantle melting and shallow-level melt-cumulate interaction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 4797–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.M.; Langmuir, C.H. Global correlations of ocean ridge basalt chemistry with axial depth and crustal thickness. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 1987, 92, 8089–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauri, E.H.; Whitehead, J.A.; Hart, S.R. Fluid dynamic and geochemical aspects of entrainment in mantle plumes. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 24–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.J.; Blundy, J.D.; Robinson, J.A.C. The role of clinopyroxene in generating U-series disequilibrium during mantle melting. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Sims, K.W.W.; Prytulak, J.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Elliott, T.; Blusztajn, J.; Fretzdorff, S.; Reagan, M.K.; Haase, K.; Humphris, S.; Schilling, J.-G. Melt generation beneath Arctic Ridges: Implications from measurements of U decay series disequilibria in the Mohns, Knipovich, and Gakkel Ridges. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 127, 140–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokat, W.; Schmidt-Aursch, M.C. Geophysical characteristics of the ultraslow spreading Gakkel Ridge, Arctic Ocean. Geophys. J. Int. 2007, 168, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellebrand, E.; Snow, J.E.; Mühe, R. Mantle melting beneath Gakkel Ridge (Arctic Ocean): abyssal peridotite spinel compositions. Chem. Geol. 2002, 182, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.J.; Langmuir, C.H.; Dick, H.J.B.; Snow, J.E.; Goldstein, S.L.; Graham, D.W.; Lehnert, K.; Kurras, G.; Jokat, W.; Mühe, R.; Edmonds, H.N. Magmatic and amagmatic seafloor generation at the ultraslow-spreading Gakkel ridge, Arctic Ocean. Nature 2003, 423, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, T.R.; Spiegelman, M. Melt Migration in Oceanic Crustal Production: A U-Series Perspective. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Rudnick, R.L.; Holland, H.D.; Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 465 – 510. [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Scott, S.R.; Sims, K.W.W.; Rivers, E.R.; Devey, C.W.; Reagan, M.K.; Hamelin, C.; Pedersen, R.B. Exploring the role of mantle eclogite at mid-ocean ridges and hotspots: U-series constraints on Jan Mayen Island and the Kolbeinsey Ridge. Chem. Geol. 2016, 444, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

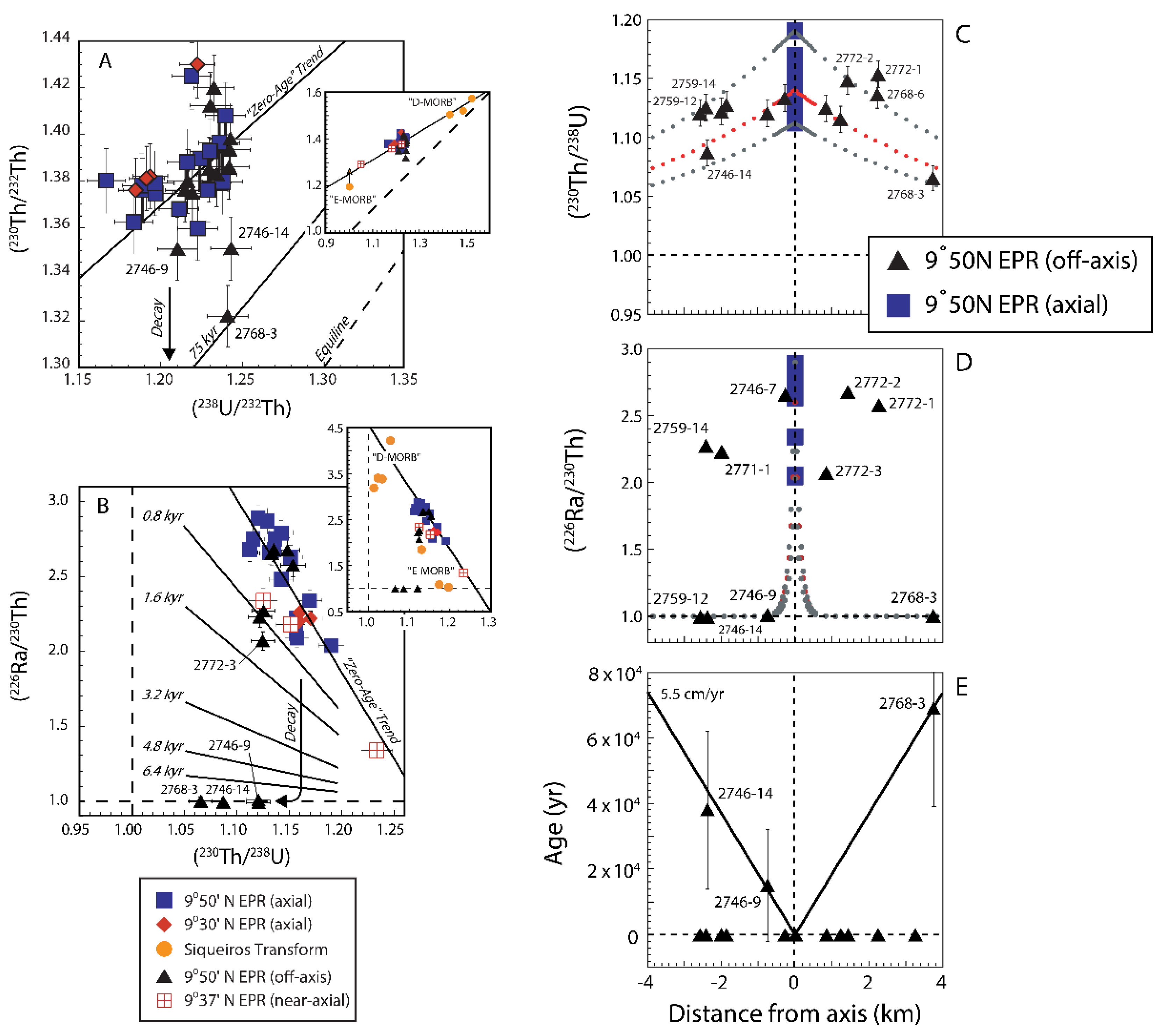

- Sims, K.W.W.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Fornari, D.J.; Perfit, M.R.; Goldstein, S.J.; Johnson, P.; DePaolo, D.J.; Hart, S.R.; Murrell, M.T.; Michael, P.J.; Layne, G.D.; Ball, L.A. Aberrant youth: Chemical and isotopic constraints on the origin of off-axis lavas from the East Pacific Rise, 9°–10°N. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2003, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Goldstein, S.J.; Sims, K.W.W.; Murrell, M.T. Uranium-Series Chronology of Gorda Ridge Volcanism: New evidence from the 1996 Eruption. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2003, 206, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.J.; Rubin, K.H.; Graham, D.W. Mantle melting and magma supply to the Southeast Indian Ridge: The roles of lithology and melting conditions from U-series disequilibria. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 278, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

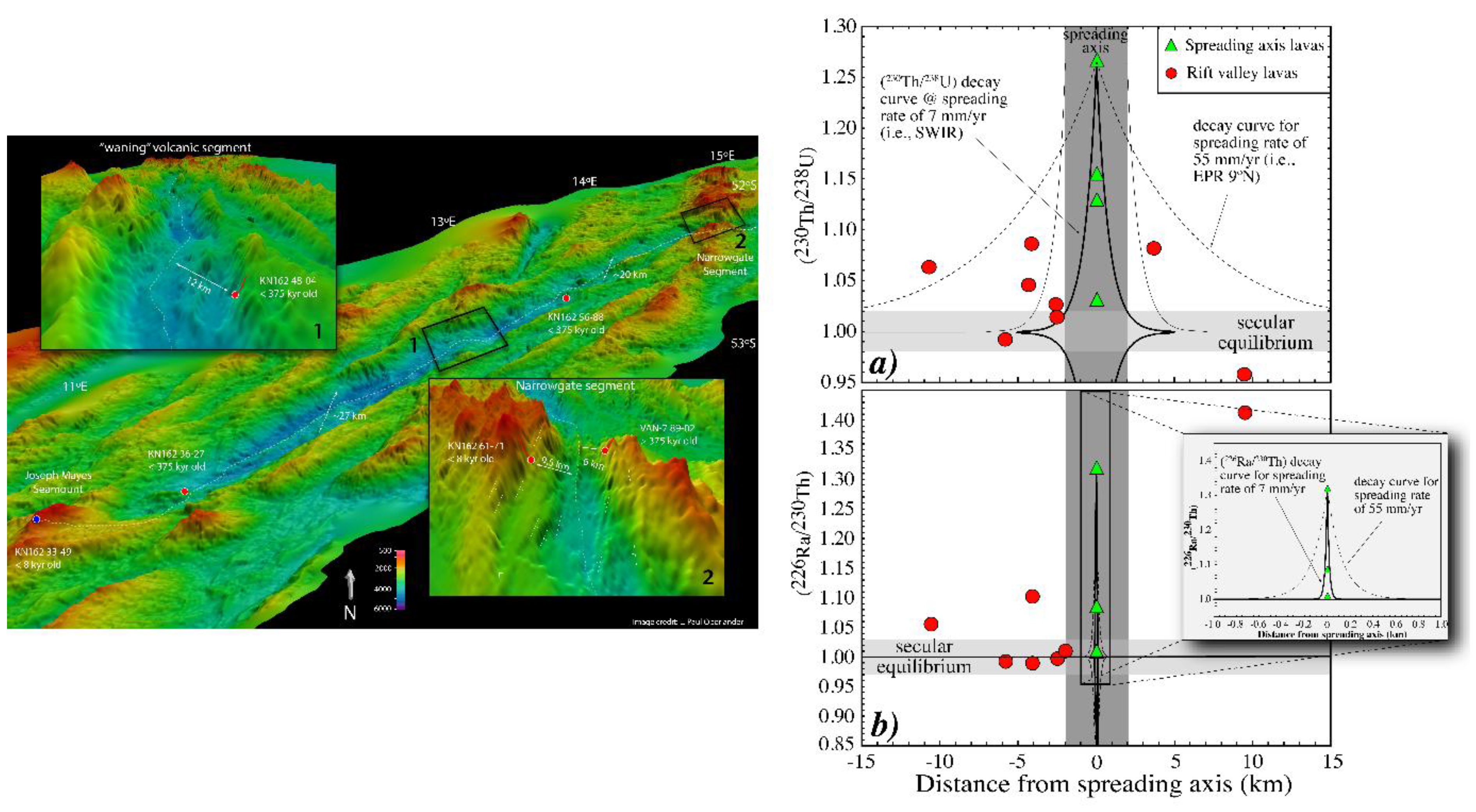

- Standish, J.J.; Sims, K.W.W. Young volcanism and rift valley construction at an ultraslow spreading ridge. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Hirth, G.; Shimizu, N.; Spiegelman, M.; Dick, H.J.B. A review of melt migration processes in the adiabatically upwelling mantle beneath oceanic spreading ridges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. A 1997, 355, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; DePaolo, D.J. Inferences about mantle magma sources from incompatible element concentration ratios in oceanic basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamori, H. Dynamic disequilibrium melting model with porous flow and diffusion controlled-chemical equilibration. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1993, 114, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, M.; Kelemen, P.B.; Sims, K.W.W. Consequences of diffuse and channelled porous melt migration on uranium series disequilibria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 4133–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Shimizu, N.; Salters, V.J. Extraction of mid-ocean-ridge basalt from the upwelling mantle by focused flow of melt in dunite channels. Nature 1995, 375, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.F.; Jones, D.W.R.; Rudge, J.F.; Keller, T. Physics of melt extraction from the mantle: Speed and style. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2022, 50, 507–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.J.; Spiegelman, M.; Stegman, D.R.; Wilson, C. The influence of spreading rate and permeability on melt focusing beneath mid-ocean ridges. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2020, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, A.; Bourdon, B. The importance of melt extraction for tracing mantle heterogeneity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann, M.M.; Stolper, E.M. A possible role for pyroxenite in the origin of the garnet signature in MORB. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1996, 124, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogiso, T.; Hirschmann, M.M.; Pertermann, M. High-pressure partial melting of mafic lithologies in the mantle. J. Petrol. 2004, 45, 2407–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, A.V.; Hofmann, A.W.; Sobolev, S.V.; Nikogosian, I.K. An olivine-free mantle source of Hawaiian shield basalts. Nature 2005, 434, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, S.V.; Sobolev, A.V.; Kuzmin, D.V.; Krivolutskaya, N.A.; Petrunin, A.G.; Arndt, N.T.; Radko, V.A.; Vasiliev, Y.R. The amount of recycled crust in sources of mantle-derived melts. Science 2007, 316, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertermann, M.; Hirschmann, M.M. Partial melting experiments on a MORB-like pyroxenite between 2 and 3 GPa: Constraints on the presence of pyroxenite in basalt source regions from solidus location and melting rate. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps Morgan, J. Thermodynamics of pressure release melting of a veined plum pudding mantle. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2001, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, G.; Mahoney, J.J. Flow and melting of a heterogeneous mantle: 1. Method and importance to the geochemistry of ocean island and mid-ocean ridge basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 230, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, G.; Mahoney, J.J. Flow and melting of a heterogeneous mantle: 2. Implications for a chemically nonlayered mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 230, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Parmentier, E.M. A two-porosity double lithology model for partial melting, melt transport and melt–rock reaction in the mantle: mass conservation equations and trace element transport. J. Petrol. 2010, 51, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. Trace element fractionation and isotope ratio variation during melting of a spatially distributed and lithologically heterogeneous mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 552, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorttle, O.; Maclennan, J. Compositional trends of Icelandic basalts: Implications for short-length scale lithological heterogeneity in mantle plumes. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2011, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertermann, M.; Hirschmann, M.M.; Hametner, K.; Günther, D.; Schmidt, M.W. Experimental determination of trace element partitioning between garnet and silica-rich liquid during anhydrous partial melting of MORB-like eclogite. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, A.; Salters, V.J.M.; Sims, K.W.W. Assessing the presence of garnet-pyroxenite in the mantle sources of basalts through combined hafnium-neodymium-thorium isotope systematics. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 1999, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Graff, M.; Liang, Y. Trace element partitioning between plagioclase and silicate melt: The importance of temperature and plagioclase composition, with implications for terrestrial and lunar magmatism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 206, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Purdy, G.M.; Schouten, H.; Sempere, J.-C.; Zervas, C. Evidence from gravity data for focused magmatic accretion along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Nature 1990, 344, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, K.E.; Goldstein, S.L.; Langmuir, C.H.; Spiegelman, M. Origin of enriched ocean ridge basalts and implications for mantle dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004, 226, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G.M.; Harding, A.J.; Orcutt, J.A. Distribution of magma beneath the East Pacific Rise between the Clipperton transform and the 9°17′ N Deval from forward modeling of common depth point data. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 1993, 98, 13945–13969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.G.; Kingsley, R.; Fontignie, D.; Poreda, R.; Xue, S. Dispersion of the Jan Mayen and Iceland mantle plumes in the Arctic: A He-Pb-Nd-Sr isotope tracer study of basalts from the Kolbeinsey, Mohns, and Knipovich Ridges. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 1999, 104, 10543–10569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichert-Toft, J.; Agranier, A.; Andres, M.; Kingsley, R.; Schilling, J.; Albarède, F. Geochemical segmentation of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge north of Iceland and ridge–hot spot interaction in the North Atlantic. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Hoernle, K.; Hauff, F.; Johansen, T.S.; Klügel, A.; Kokfelt, T.; Lundstrom, C. 238U–230Th–226Ra Disequilibria Constraints on the Magmatic Evolution of the Cumbre Vieja Volcanics on La Palma, Canary Islands. J. Petrol. 2015, 56, 1999–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, L.J.; Hamelin, C.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Scott, S.R.; Sims, K.W.W.; Yeo, I.A.; Devey, C.W.; Pederson, R.B. North Atlantic hotspot-ridge interaction near Jan Mayen Island. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 2016, 2, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, M.; Kelemen, P.B.; Aharnohov, E. Causes and consequences of flow organization during melt transport: The reaction infiltration instability in compactible media. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2001, 106, 2061–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, M.; Kelemen, P.B. Extreme chemical variability as a consequence of channelized melt transport. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2003, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, A.J.; Rubin, K.H.; Garcia, M.O. 226Ra-230Th-238U disequilibria of historical Kilauea lavas (1790–1982) and the dynamics of mantle melting within the Hawaiian plume. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 186, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokfelt, T.F.; Hoernle, K.; Hauff, F. Upwelling and melting of the Iceland plume from radial variation of 238U-230Th disequilibria in postglacial volcanic rocks. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2003, 214, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Sims, K.W.W. U-series Constraints on Intraplate Basaltic Magmatism. In U-series Geochemistry; Bourdon, B., Lundstrom, C., Henderson, G., Turner, S.P., Eds.; Eds., Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, D.C., United States, 2003; pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prytulak, J.; Elliott, T. Determining melt productivity of mantle sources from 238U-230Th and 235U-231Pa disequilibria; an example from Pico Island, Azores. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 2103–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.J. Hypothesis of Earth's behaviour. Nature 1963, 198, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.J. Convection plumes in the lower mantle. Nature 1971, 230, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.J. Deep mantle convection plumes and plate motions. Bull. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. 1972, 56, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead Jr., J. A.; Luther, D.S. Dynamics of laboratory diapir and plume models. J. Geophys. Res. 1975, 80, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.; McKenzie, D. Melt generation by plumes: a study of Hawaiian volcanism. J. Petrol. 1991, 32, 501–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.M. Sources of oceanic basalts: Radiogenic isotopic evidence. Geology 1985, 13, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.M. Oceanic island basalts and mantle plumes: The geochemical perspective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2010, 38, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, B.; Ribe, N.M.; Stracke, A.; Saal, A.E.; Turner, S.P. Insights into the dynamics of mantle plumes from uranium-series geochemistry. Nature 2006, 444, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, A.J.; Garcia, M.O.; Carlson, R.W.; Hauri, E.H. Slow changes in lava chemistry at Kama‘ehuakanaloa linked to sluggish mantle upwelling on the margin of the Hawaiian plume. Geology 2023, 51, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.A.; Katsura, T. Chemical composition of Hawaiian lavas. J. Petrol. 1964, 5, 82–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Frey, F.A. Origin of Hawaiian tholeiite and alkalic basalt. Nature 1983, 302, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswami, S.; Turekian, K.K.; Bennett, J.T. The behavior of 232Th and the 238U decay chain nuclides during magma formation and volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Finkel, R.C.; Macdougall, J.D. Comparison of 230Th-238U disequilibrium systematics in lavas from three hot spot regions: Hawaii, Prince Edward and Samoa, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinitz, I.M.; Turekian, K.K. The behavior of the uranium decay chain nuclides and thorium during the flank eruptions of Kilauea (Hawaii) between 1983 and 1985. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 3735–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hémond, C.; Hofmann, A.W.; Heusser, G.; Condomines, M.; Raczek, I.; Michael^Rhodes, J. U-Th-Ra systematics in Kilauea and Mauna Loa basalts, Hawaii. Chem. Geol. 1994, 116, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.S.; O’Nions, R.K. Melting rates beneath Hawaii: Evidence from uranium series isotopes in recent lavas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1993, 120, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, A.J.; Rubin, K.H.; Garcia, M.O. 238U-230Th-226Ra disequilibria in historical Kilauea volcano lavas: Mantle melting within the Hawaiian plume. In Proceedings of the Ninth Annual V.M. Goldschmidt Conference, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, G.; Reagan, M.K.; Sims, K.W.W.; Thornber, C.R.; Waters, C.L.; Phillips, E.H. 238U-230Th-226Ra-210Pb-210Po Disequilibria constraints on magma generation, ascent, and degassing during the ongoing eruption of Kilauea. J. Petrol. 2017, 58, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.M.; Reid, M.R.; Murrell, M.T.; Clague, D.A. Crystal and magma residence at Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii: 230Th-226Ra dating of the 1955 east rift eruption. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 184, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, A.J.; Rubin, K.H.; Garcia, M.O. 226Ra–230Th–238U disequilibria of historical Kilauea lavas (1790–1982) and the dynamics of mantle melting within the Hawaiian plume. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 186, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salters, V.J.M.; Hart, S.R. The hafnium paradox and the role of garnet in the source of mid-ocean-ridge basalts. Nature 1989, 342, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, D.A.; Murrell, M.T. Observations of 231Pa/235U disequilibrium in volcanic rocks. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 148, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribe, N.M.; Christensen, U.R. The dynamical origin of Hawaiian volcanism. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999, 171, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, A.J.; Keyes, M.J.; Duncan, J.A.; Hauri, E.H.; Carlson, R.W.; Garcia, M.O. Excesses of seawater-derived 234U in volcanic glasses from Loihi Seamount due to crustal contamination. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 304, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabaux, F.; Allègre, C.J. 238U-230Th-226Ra disequilibria in volcanics- a new insight into melting conditions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1994, 126, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleep, N.H. Hotspots and mantle plumes—some phenomenology. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 6715–6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribe, N.M. The dynamics of plume-ridge interaction 2. Off-ridge plumes. J. Geophys. Res. 1996, 101, 16,195–16,204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePaolo, D.J.; Stolper, E.M. Models of Hawaiian volcano growth and plume structure: Implications of results from the Hawaii Scientific Drilling Project. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 1996, 101, 11643–11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, M.; Ribe, N. The geochemistry of Hawaiian plume dynamics. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual V.M. Goldschmidt Conference, Davos, Switzerland, August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Hart, S.R. Comparison of Th, Sr, Nd and Pb isotopes in oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle heterogeneity and magma genesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 245, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePaolo, D.J.; Wasserburg, G.J. Inferences about magma sources and mantle structure from variations of 143Nd/144Nd. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1976, 3, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zindler, A.; Hart, S.R. Chemical Geodynamics. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1988, 14, 493–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.R. Heterogeneous mantle domains: signatures, genesis and mixing chronologies. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1988, 90, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, A.; Hofmann, A.W.; Hart, S.R. FOZO, HIMU, and the rest of the mantle zoo. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2005, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudge, J.F.; Maclennan, J.; Stracke, A. The geochemical consequences of mixing melts from a heterogeneous mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 114, 112–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.; Afonso, J.C.; Tilhac, R. A disequilibrium reactive transport model for mantle magmatism. J. Petrol. 2020, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, A.; Willig, M.; Genske, F.; Béguelin, P.; Todd, E. Chemical geodynamics insights from a machine learning approach. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prytulak, J.; Avanzinelli, R.; Koetsier, G.; Kreissig, K.; Beier, C.; Elliott, T. Melting versus contamination effects on 238U-230Th-226Ra and 235U-231Pa disequilibria in lavas from São Miguel, Azores. Chem. Geol. 2014, 381, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neymark, L.A.; Amelin, Y.V.; Paces, J.B. 206Pb–230Th–234U–238U and 207Pb–235U geochronology of Quaternary opal, Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 64, 2913–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.A.; Hogan, L.G. Radiometric dating of young MORB using the 40Ar-39Ar incremental heating method. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1994, 21, 1927–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Mcdougall, J.D. Dating of neovolcanic MORB using (226Ra/230Th) disequilibrium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1990, 101, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.J.; Murrell, M.T.; Janecky, D.R.; Delaney, J.R.; Clague, D.A. Geochronology and petrogenesis of MORB from the Juan de Fuca and Gorda ridges by 238U–230Th disequilibrium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1991, 107, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.J.; Murrell, M.T.; Williams, R.W. 231Pa and 230Th chronology of mid-ocean ridge basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1993, 115, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.J.; Perfit, M.R.; Batiza, R.; Fornari, D.J.; Murrell, M.T. Off-axis volcanism at the East Pacific Rise detected by uranium-series dating of basalts. Nature 1994, 367, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Macdougall, J.D.; Perfit, M.R. 210Po-210Pb dating of recent volcanic eruptions on the sea floor. Nature 1994, 368, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Van der Zander, I.; Smith, M.C.; Bergmanis, E.C. Minimum speed limit for ocean ridge magmatism from 210Pb–226Ra–230Th disequilibria. Nature 2005, 437, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, A.M.; Goldstein, S.J. 226Ra-230Th disequilibrium in axial and off-axis mid-ocean ridge basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1993, 57, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, K.M.; Brandl, P.A.; Devey, C.W.; Hauff, F.; Melchert, B.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Kokfelt, T.F.; Paulick, H. Compositional variation and 226Ra-230Th model ages of axial lavas from the southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 8° 48′ S. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2016, 17, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.R.; Ramos, F.C.; Gill, J.B. Spreading dynamics of an intermediate Ridge: Insights from U-series disequilibria, Endeavour Segment, Juan de Fuca Ridge. J. Petrol. 2018, 59, 1847–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zindler, A.; Niu, Y. Constraints on melt movement beneath the East Pacific Rise from 230Th-238U disequilibrium. Science 2002, 295, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Beier, C.; Niu, Y.; Cook, C. U-Th-Ra disequilibria and the extent of off-axis volcanism across the East Pacific Rise at 9 30′ N, 10 30′ N, and 11 20′ N. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reubi, O.; Sims, K.W.W.; Bourdon, B. 238U-230Th equilibrium in arc magmas and implications for the time scales of mantle metasomatism. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2014, 391, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M.K.; Sims, K.W.W.; Erich, J.; Thomas, R.B.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Layne, G.; Ball, L. Time-scales of differentiation from mafic parents to rhyolite in North American continental arcs. J. Petrol. 2003, 44, 1703–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; Williams, R.; Bruland, K. Eruption of basalt and andesite lava degasses 222Rn and 210Po. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1985, 12, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condomines, M.; Hémond, C.; Allègre, C.J. U-Th-Ra radioactive disequilibria and magmatic processes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1988, 90, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmarsson, O. Short magma chamber residence time at an Icelandic volcano inferred from U-series disequilibria. Nature 1996, 382, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.R.; Coath, C.D.; Harrison, T.M.; McKeegan, K.D. Prolonged residence times for the youngest rhyolites associated with Long Valley Caldera: 230Th–238U ion microprobe dating of young zircons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1997, 150, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.R. Timescales of Magma Transfer and Storage in the Crust. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Rudnick, R.L.; Holland, H.D.; Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 167-193. [CrossRef]

- Condomines, M.; Gauthier, P.J.; Sigmarsson, O. Timescales of magma chamber processes and dating of young volcanic rocks. In U-series Geochemistry; Bourdon, B., Lundstrom, C., Henderson, G., Turner, S.P., Eds.; Eds., Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, D.C., United States, 2003; pp. 125–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jicha, B.R.; Singer, B.S.; Beard, B.L.; Johnson, C.M. Contrasting timescales of crystallization and magma storage beneath the Aleutian Island arc. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 236, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M.K.; Tepley III, F.J.; Gill, J.B.; Wortel, M.; Hartman, B. Rapid time scales of basalt to andesite differentiation at Anatahan volcano, Mariana Islands. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2005, 146, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.M.; Sims, K.W.W.; Eiler, J.M.; Banerjee, N. Timescales of storage and recycling of crystal mush at Krafla Volcano, Iceland. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2016, 171, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

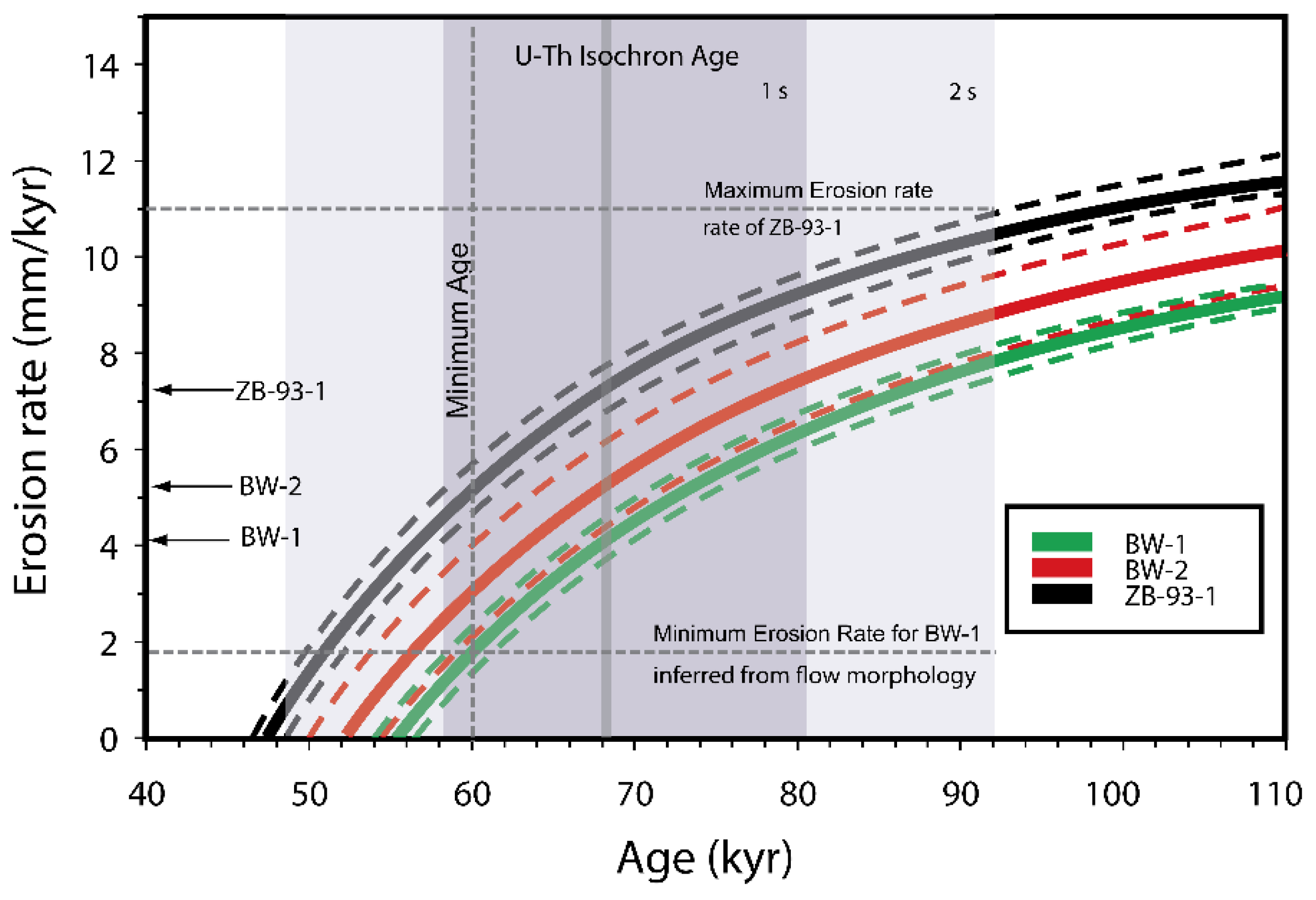

- Sims, K.W.W.; Ackert, Jr., R. P.; Ramos, F.; Sohn, R.A.; Murrell, M.T.; DePaolo, D.J. Determining eruption ages and erosion rates of Quaternary basaltic volcanism from combined U-series disequilibria and cosmogenic exposure ages. Geology 2007, 35, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Black, S.; Berlo, K. 210Pb–226Ra and 228Ra–232Th systematics in young arc lavas: implications for magma degassing and ascent rates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004, 227, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, A.M.; Hammond, P.E. 238U-230Th-226Ra disequilibria in young Mount St. Helens rocks: time constraint for magma formation and crystallization. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1991, 107, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, A.M. 238U-230Th-226Ra disequilibrium in young Mt. Shasta andesites and dacites. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1992, 53, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellmer, G.F.; Rubin, K.H.; Grönvold, K.; Jurado-Chichay, Z. On the recent bimodal magmatic processes and their rates in the Torfajökull–Veidivötn area, Iceland. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 269, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundy, J.; Wood, B. Prediction of crystal-melt partition coefficients from elastic moduli. Nature 1994, 372, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, R.A.; Menke, W. Application of maximum likelihood and bootstrap methods to nonlinear curve-fit problems in geochemistry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2002, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.J.; Blundy, J.D. Trace Element Partitioning under Crustal and Uppermost Mantle Conditions: The Influences of Ionic Radius, Cation Charge, Pressure, and Temperature. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Carlson, R.W.; Holland, H.D.; Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 568. [CrossRef]

- Kokfelt, T.F.; Hoernle, K.; Lundstrom, C.; Hauff, F.; Van Den Bogaard, C. Time-scales for magmatic differentiation at the Snaefellsjökull central volcano, western Iceland: Constraints from U–Th–Pa–Ra disequilibria in post-glacial lavas. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 1120–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.M.; Reid, M.R. Uranium-series crystal ages. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2008, 69, 479–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, N.W.; Phillips, F.M. Cosmogenic 36Cl ages of lava flows in the Zuni-Bandera volcanic field, north central New Mexico, USA. New Mex. Bur. of Geol. and Miner. Resour. Bull. 2004, 160, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Harpel, C.J.; Kyle, P.R.; Esser, R.P.; McIntosh, W.C.; Caldwell, D.A. 40Ar/39Ar dating of the eruptive history of Mount Erebus, Antarctica: summit flows, tephra, and caldera collapse. Bull. Volcanol. 2004, 66, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, R.A.; Sims, K.W.W. Bending as a mechanism for triggering off-axis volcanism on the East Pacific Rise. Geology 2005, 33, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, P.J.; Condomines, M. 210Pb–226Ra radioactive disequilibria in recent lavas and radon degassing: inferences on the magma chamber dynamics at Stromboli and Merapi volcanoes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999, 172, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M.K.; Tepley III, F.J.; Gill, J.B.; Wortel, M.; Garrison, J. Timescales of degassing and crystallization implied by 210Po–210Pb–226Ra disequilibria for andesitic lavas erupted from Arenal volcano. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2006, 157, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M.K.; Turner, S.; Legg, M.; Sims, K.W.W.; Hards, V.L. 238U- and 232Th-decay series constraints on the timescales of crystal fractionation to produce the phonolite erupted in 2004 near Tristan da Cunha, South Atlantic Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 4367–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlo, K.; Turner, S. 210Pb–226Ra disequilibria in volcanic rocks. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 296, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condomines, M.; Sigmarsson, O.; Gauthier, P.J. A simple model of 222Rn accumulation leading to 210Pb excesses in volcanic rocks. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 293, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmarsson, O.; Condomines, M.; Gauthier, P.J. Excess 210Po in 2010 Eyjafjallajökull tephra (Iceland): Evidence for pre-eruptive gas accumulation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2015, 427, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbotte, S.; Macdonald, K. East Pacific Rise 8–10 30′ N: Evolution of ridge segments and discontinuities from SeaMARC II and three-dimensional magnetic studies. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 1992, 97, 6959–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, G.; Sigmarsson, O.; Larsen, G. Declining Gas Accumulation Under Hekla Volcano, Iceland, From 210Pb-226Ra Disequilibrium. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2025, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, P.J.; Le Cloarec, M.F.; Condomines, M. Degassing processes at Stromboli volcano inferred from short-lived disequilibria (210Pb–210Bi–210Po) in volcanic gases. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2000, 102, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H. Degassing of metals and metalloids from erupting seamount and mid-ocean ridge volcanoes: Observations and predictions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 3525–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.T.; Krishnaswami, S.; Turekian, K.K.; Melson, W.G.; Hopson, C.A. The uranium and thorium decay series nuclides in Mt. St. Helens effusives. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1982, 60, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, G.; Le Cloarec, M.F.; Ardouin, B.; Le Roulley, J.C. Volcanic emission of radionuclides and magma dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1985, 76, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Macdougall, J.D. Submarine magma degassing and explosive magmatism at Macdonald (Tamarii) seamount. Nature 1989, 341, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstoy, M.; Cowen, J.P.; Baker, E.T.; Fornari, D.J.; Rubin, K.H.; Shank, T.M.; Waldhauser, F.; Bohnenstiehl, D.R.; Forsyth, D.W.; Holmes, R.C.; Glazer, B. A sea-floor spreading event captured by seismometers. Science 2006, 314, 1920–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrini, V.L.; Tivey, M.K.; Carbotte, S.M.; Martinez, F.; Roman, C. Variable morphologic expression of volcanic, tectonic, and hydrothermal processes at six hydrothermal vent fields in the Lau back-arc basin. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Sato, J. Estimation of gas-releasing efficiency of erupting magma from 226Ra–222Rn disequilibrium. Nature 1977, 266, 439–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlo, K.; Turner, S.; Blundy, J.; Black, S.; Hawkesworth, C. Tracing pre-eruptive magma degassing using (210Pb/226Ra) disequilibria in the volcanic deposits of the 1980–1986 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 249, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cloarec, M.F.; Gauthier, P.J. Merapi Volcano, Central Java, Indonesia: A case study of radionuclide behavior in volcanic gases and its implications for magma dynamics at andesitic volcanoes. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmanis, E.C.; Sinton, J.; Rubin, K.H. Recent eruptive history and magma reservoir dynamics on the southern East Pacific Rise at 17°30′ S. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, B.; Clague, D.A.; Gill, J.B. Magmagenesis at Axial Seamount, Juan de Fuca Ridge: Insights from Uranium-Series Systematics. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, San Francisco, California, United States, December 2009.

- Kent, G.M.; Singh, S.; Harding, A.; Sinha, M.; Orcutt, J.; Barton, P.; Bazin, S.; Hobbs, R.; Tong, C.; Pye, J. Evidence from three-dimensional seismic reflectivity images for enhanced melt supply beneath mid-ocean ridge discontinuities. Nature 2000, 406, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Harding, A.; Kent, G.; Sinha, M.; Combier, V.; Bazin, S.; Tong, C.; Pye, J.; Barton, P.; Hobbs, R.; White, R.; Orcutt, J. Seismic reflection images of the moho underlying melt sills at the East Pacific Rise. Nature 2006, 442, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayzar, T.M.; Cooper, K.M.; Reagan, M.K.; Kent, A.J. Gas transport model for the magmatic system at Mount Pinatubo, Philippines: Insights from (210Pb)/(226Ra). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2009, 181, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.J.; Elias, T. One hundred volatile years of volcanic gas studies at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. Characteristics of Hawaiian Volcanoes 2014, 1801, 295–320. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Kyle, P.R.; Pichat, S.; Bluzstajn, J.; Kelly, P.J.; Ball, L.A.; Layne, G.D. A Sr, Nd, Hf, and Pb isotope perspective on the genesis and long-term evolution of alkaline magmas from Erebus volcano, Antarctica. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008, 177, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.H.; Sims, K.W.W.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Aster, R.C.; Gaetani, G.A.; Kyle, P.R.; Wallace, P.J.; Rasmussen, D.J. The nature and evolution of mantle upwelling at Ross Island, Antarctica, with implications for the source of HIMU lavas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018, 498, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S-H.; Langmuir, C.H.; Sims, K.W.W.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Kim, S-S.; Scott, S.R.; Lin, J.; Choi, H.; Yang, Y-S.; Michaels, P.J. An isotopically distinct Zealandia-Antarctic mantle domain in the Southern Ocean, Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 206–214. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.J.; Kyle, P.R.; Dunbar, N.W.; Sims, K.W.W. Geochemistry and mineralogy of the phonolite lava lake, Mount Erebus volcano, Antarctica: 1972 – 2004 and comparison with older lavas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008, 177, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, C.; Moretti, R.; Kyle, P.R.; Eschenbacher, A.; Lowenstern, J.B.; Hervig, R.L; Dunbar, N.W. Mantle to surface degassing of alkalic magmas at Erebus volcano, Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 306, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, N.W.; Cashman, K.V.; Dupré, R. Crystallization Processes of Anorthoclase Phenocrysts in the Mount Erebus Magmatic System: Evidence from Crystal Composition, Crystal Size Distributions, and Volatile Contents of Melt Inclusions. In Volcanological and Environmental Studies of Mount Erebus, Antarctica; Kyle, P.R., Ed.; American Geophysical Union: Washington D.C., United States, 1994; Volume 66, pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenbacher, A.J. Open-System Degassing of a Fractionating, Alkaline Magma, Mount Erebus, Ross Island, Antarctica. M.S. Thesis, N.M. Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, New Mexico, United States, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, D.J.; Kyle, P.R.; Wallace, P.J.; Sims, K.W.W.; Gaetani, G.A.; Phillips, E.H. Understanding degassing and transport of CO2 rich alkalic magmas at Ross Island, Antarctica using olivine-hosted melt inclusions. J. Petrol. 2017, 58, 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.W.; Gill, J.B.; Bruland, K.W. Ra-Th disequilibria systematics: timescale of carbonatite magma formation at Oldoinyo Lengai volcano, Tanzania. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1986, 50, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, M.K.; Herrstrom, E.A.; Murrell, M.T. Uranium series and beryllium isotope evidence for an extended history of subduction modification of the mantle below Nicaragua. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 4199–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, L.; Reagan, M.; Turner, S.; Sparks, R.S.; Handley, H.; Didonna, R.; Berlo, K.; Hansen, S.; Barclay, J. U-series histories of magmatic volatile phase and enclave development at Soufrière Hills Volcano, Montserrat. Chem. Geol. 2021, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.J.; Murrell, M.T.; Janecky, D.R. Th and U isotopic systematics of basalts from the Juan de Fuca and Gorda Ridges by mass spectrometry, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1989, 96, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, A.N.; Lee, D.C.; Christensen, J.N.; Walder, A.J.; Freedman, P.A.; Jones, C.E.; Hall, C.M.; Yi, W.; Teagle, D. Recent developments in inductively coupled plasma magnetic sector multiple collector mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Processes 1995, 146, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layne, G.D.; K. W.W. Sims Analysis of 232Th/230Th in volcanic rocks by Secondary Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000, 203, 1-3, 187-198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, A.J.; Carlson, R.W.; Hauri, E.H. Precise and accurate measurement of 226Ra -230Th-238U disequilibria in volcanic rocks using plasma ionization muticollector mass spectrometry. Chem. Geol. 2002, 188, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, D.L.; Prytulak, J.; Richards, D.A.; Elliott, T.; Coath, C.D.; Smart, P.L.; Scholz, D. Procedures for accurate U and Th isotope measurements by high precision MC-ICPMS. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 264, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.A.; Sims, K.W.W.; Schwieters, J. Measurement of 234U/238U and 230Th/232Th in volcanic rocks using the Neptune MC-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2008, 23, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K.W.W.; Gill, J.; Dossetto, A.; Hoffmann, D.; Lundstrom, C.C.; Williams, R.; Ball, L.A.; Tollstrup, D.; Turner, S.P.; Prytulak, J.; Glessner, J.; Standish, J.J. Elliott, T. An inter-laboratory assessment of the Th Isotopic Composition of Synthetic and Rock standards. Geostand. and Anal. Res. 2008, 32, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.R.; Sims, K.W.W.; Reagan, M.K. , Ball, L.; Schwieters, J.B.; Bouman, C.; Lloyd, N.S.; Waters, C.L.; Standish, J.J.; Tollstrup, D.L. The application of abundance sensitivity filters to the precise and accurate measurement of U-series nuclides by plasma mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 435, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koornneef, J.M.; Stracke, A.; Aciego, S.; Reubi, O.; Bourdon, B. A new method for U–Th–Pa–Ra separation and accurate measurement of 234U–230Th–231Pa–226Ra disequilibria in volcanic rocks by MC-ICPMS. Chem. Geol. 2010, 277, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, A.; Rubin, K.; McLean, N.; Bowring, J.; Bard, E.; Edwards, R.; Henderson, G.; Reid, M.; Richards, D.; Sims, K.W.W.; Walker, J.; Yokoyama, Y. Data reporting standards for publication of U-series data for geochronology and timescale assessment in the Earth Sciences. Quat. Geochronol. 2017, 39, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H. Analysis of 232Th/230Th in volcanic rocks: a comparison of thermal ionization mass spectrometry and other methodologies. Chem. Geol. 2001, 175, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.W. Geophysical constraints on mantle flow and melt generation beneath mid-ocean ridges. Geophysical Monograph Series 1992, 71, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.M.; White, S.M.; Nunnery, A.; Mason, J.L.; Wanless, D.; Perfit, M.R.; Waters, C.L.; Sims, K.W.W.; Fornari, D.J.; Zaino, A.J.; Ridley, W.I. Seafloor photo-geology and sonar terrain modeling at the 9°N overlapping spreading center, East Pacific Rise. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).