Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Key Disorders of Amino Acid Metabolism: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Approaches

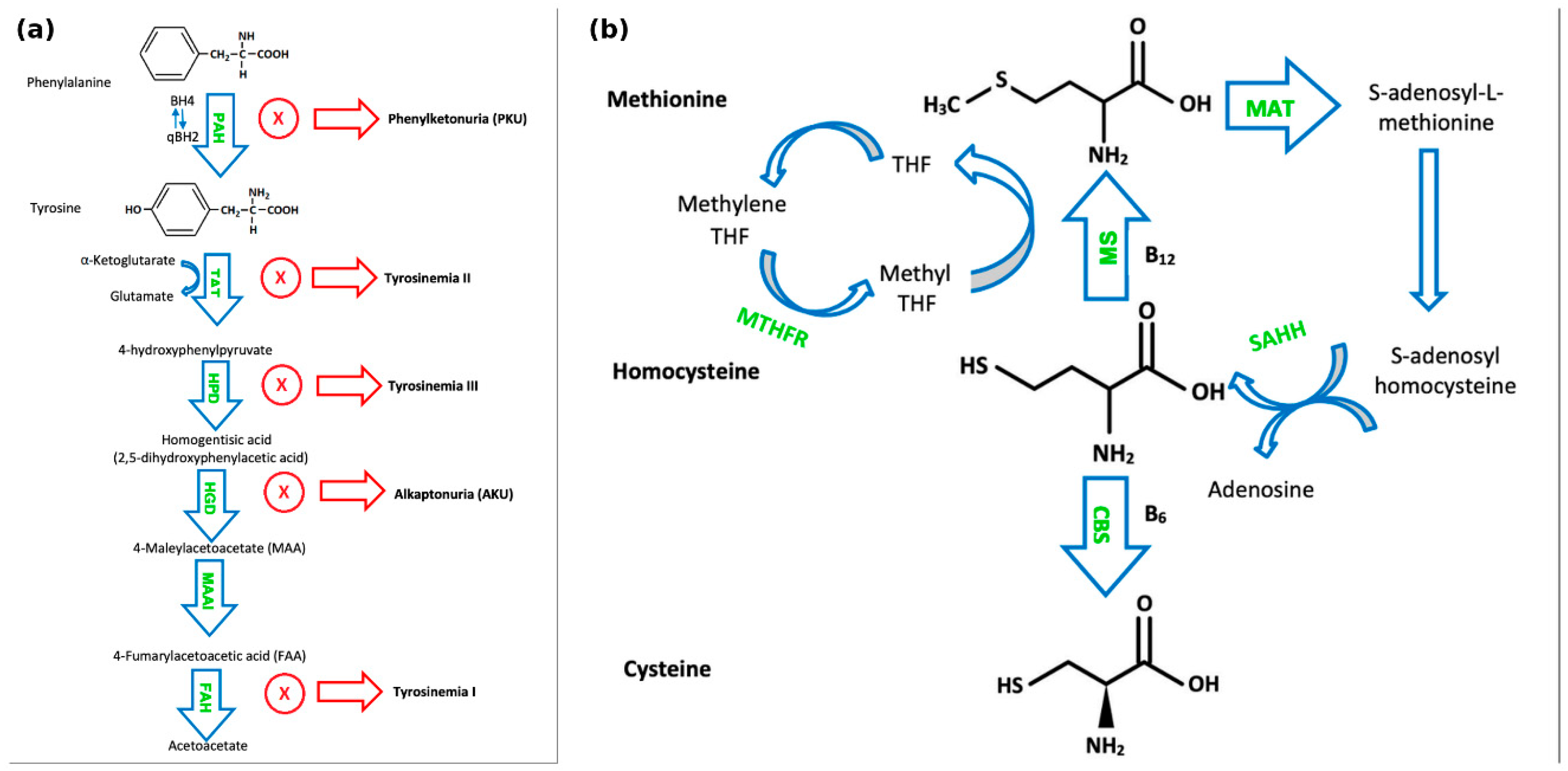

2.1. Phenylketonuria

2.2. Alkaptonuria

2.3. Tyrosinemia Type I, Type II and Type III

2.4. Homocystinuria

2.5. Methylmalonic Acidaemia

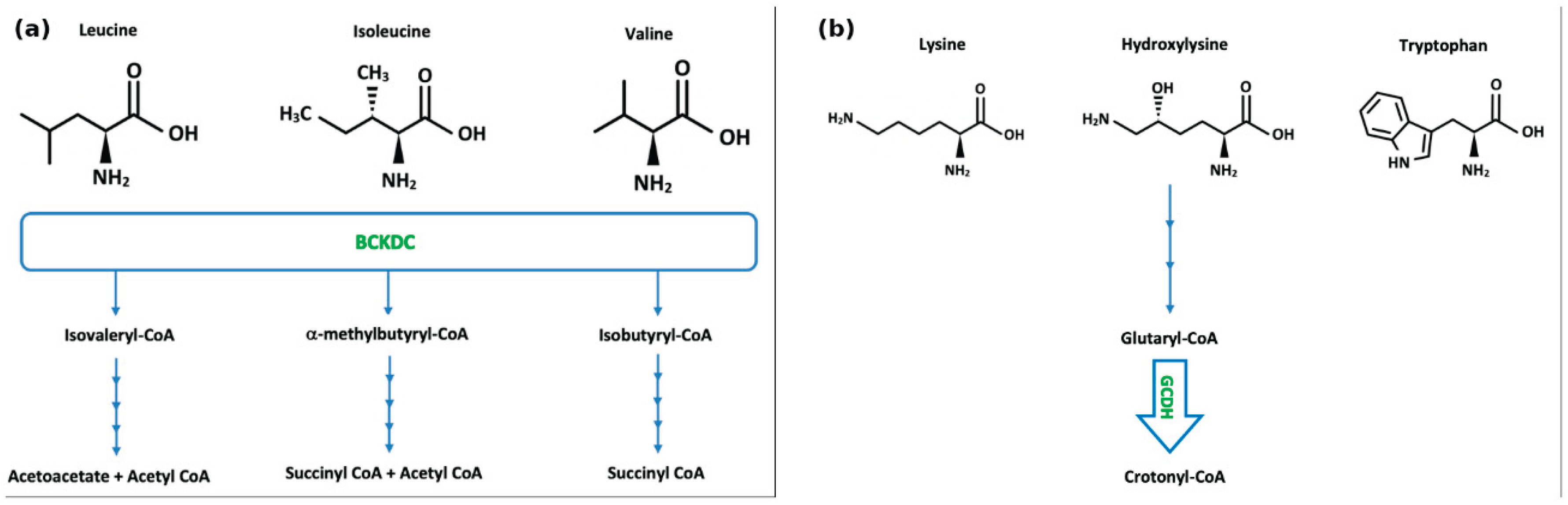

2.6. Maple Syrup Urine Disease

2.7. Nonketotic Hyperglycinaemia

2.8. Pyridoxine-Dependent Epilepsy

2.9. Cystinuria

2.10. Lysinuric Protein Intolerance

2.11. Hartnup Disease

2.12. Glutaric Aciduria Type 1

2.13. Serine Deficiency

2.14. Hyperprolinaemia Type I and Type II

2.15. Glutamine Synthetase Deficiency

2.16. Asparagine Synthetase Deficiency

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-HIAA | 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid |

| AASS | Aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase (gene) |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| AAV8 | Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| AEDs | Anti-epileptic drugs |

| AKU | Alkaptonuria |

| AMT | Aminomethyltransferase (gene) |

| ASD | Asparagine synthetase deficiency |

| ASNS | Asparagine synthetase gene |

| BCAAs | Branched-chain amino acids |

| BCKD | Branched-chain keto-acid dehydrogenase |

| BCKDC | Branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex |

| BCKDH | Branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase |

| BD | Twice daily |

| BH4 | Tetrahydrobiopterin |

| BHMT | Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase |

| BID | Twice daily |

| BTMs | Bone turnover markers |

| C3 | Propionylcarnitine |

| CBS | Cystathionine-β-synthase |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CYP2D6 | Cytochrome P450 2D6 |

| CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| CYPUGT | Cytochrome P450 / UGT (as written in manuscript) |

| DNAJC12 | DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C12 |

| EC | Enzyme Commission |

| ESPFKU | European Society for Phenylketonuria |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| ESRF | End-stage renal failure |

| FAA | Fumarylacetoacetate |

| FAH | Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase |

| GA1 | Glutaric aciduria type 1 |

| GCDH | Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (gene) |

| GH | Growth hormone |

| GLDC | Glycine decarboxylase (gene) |

| GLUL | Glutamate–ammonia ligase (glutamine synthetase) gene |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| GSD | Glutamine synthetase deficiency |

| HCU | Homocystinuria |

| HGA | Homogentisic acid |

| HGD | Homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase |

| HRT | Hormone replacement therapy |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| HPD | 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase |

| HVA | Homovanillic acid |

| IEAAMs | Inborn errors of amino acid metabolism |

| IV | Intravenous |

| L-DOPA | L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| LNAAs | Large Neutral Amino Acids |

| LP | Lumbar puncture |

| LPI | Lysinuric protein intolerance |

| LRTs | Lysine-reduction therapies |

| MAA | Maleylacetoacetate |

| MAAI | Maleylacetoacetate isomerase |

| MAT | Methionine S-adenosyltransferase |

| MMA | Methylmalonic acidemia |

| MMAA | Methylmalonic acidemia cblA type (gene) |

| MMAB | Methylmalonic acidemia cblB type (gene) |

| MMUT | Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (gene) |

| MS | Methionine synthase |

| MSUD | Maple Syrup Urine Disease |

| MTHFR | Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| NG | Nasogastric |

| NKH | Nonketotic hyperglycinemia |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NTBC | Nitisinone (2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione) |

| OMIM | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man |

| PAH | Phenylalanine hydroxylase |

| PAL | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase |

| PDE | Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PKU | Phenylketonuria |

| PO | By mouth |

| PRODH | Proline dehydrogenase (gene) |

| QDS | Four times daily |

| SAH | S-adenosylhomocysteine |

| SAHH | S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase |

| SAM | S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| TAT | Tyrosine aminotransferase |

| TDS | Three times daily |

| THF | Tetrahydrofolate |

| tHcy | Total homocysteine |

| Tyr | Tyrosine |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Chandel, N. S., Amino Acid Metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2021, 13 (4). [CrossRef]

- Tessari, P.; Lante, A.; Mosca, G., Essential amino acids: master regulators of nutrition and environmental footprint? Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26074. [CrossRef]

- Blau, N.; van Spronsen, F. J.; Levy, H. L., Phenylketonuria. Lancet 2010, 376 (9750), 1417-27. [CrossRef]

- Blau, N.; Hennermann, J. B.; Langenbeck, U.; Lichter-Konecki, U., Diagnosis, classification, and genetics of phenylketonuria and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies. Mol Genet Metab 2011, 104 Suppl, S2-9. [CrossRef]

- van Wegberg, A. M. J.; MacDonald, A.; Ahring, K.; Bélanger-Quintana, A.; Blau, N.; Bosch, A. M.; Burlina, A.; Campistol, J.; Feillet, F.; Giżewska, M., et al., The complete European guidelines on phenylketonuria: diagnosis and treatment. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017, 12 (1), 162. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, F.; Lynch, G.; Reynolds, C. M.; Green, A.; Parr, G.; Howard, C.; Knerr, I.; Rice, J., Determination of the Protein and Amino Acid Content of Fruit, Vegetables and Starchy Roots for Use in Inherited Metabolic Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16 (17). [CrossRef]

- Levy, H. L.; Milanowski, A.; Chakrapani, A.; Cleary, M.; Lee, P.; Trefz, F. K.; Whitley, C. B.; Feillet, F.; Feigenbaum, A. S.; Bebchuk, J. D., et al., Efficacy of sapropterin dihydrochloride (tetrahydrobiopterin, 6R-BH4) for reduction of phenylalanine concentration in patients with phenylketonuria: a phase III randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2007, 370 (9586), 504-10. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, S.; O'Regan, M.; Stenson, C.; Bracken, J.; Hendroff, U.; Agasarova, A.; Deverell, D.; Treacy, E. P., Extended Experience of Lower Dose Sapropterin in Irish Adults with Mild Phenylketonuria. JIMD Rep 2018, 40, 71-76. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Levy, H.; Amato, S.; Vockley, J.; Zori, R.; Dimmock, D.; Harding, C. O.; Bilder, D. A.; Weng, H. H.; Olbertz, J., et al., Pegvaliase for the treatment of phenylketonuria: Results of a long-term phase 3 clinical trial program (PRISM). Mol Genet Metab 2018, 124 (1), 27-38. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.; van Wegberg, A. M. J.; Ahring, K.; Beblo, S.; Bélanger-Quintana, A.; Burlina, A.; Campistol, J.; Coşkun, T.; Feillet, F.; Giżewska, M., et al., PKU dietary handbook to accompany PKU guidelines. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2020, 15 (1), 171. [CrossRef]

- Vernon, H. J.; Koerner, C. B.; Johnson, M. R.; Bergner, A.; Hamosh, A., Introduction of sapropterin dihydrochloride as standard of care in patients with phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab 2010, 100 (3), 229-33. [CrossRef]

- Sanford, M.; Keating, G. M., Sapropterin: a review of its use in the treatment of primary hyperphenylalaninaemia. Drugs 2009, 69 (4), 461-76. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, S.; O’Regan, M.; Stenson, C.; Bracken, J.; Hendroff, U.; Agasarova, A.; Deverell, D.; Treacy, E. P., Extended Experience of Lower Dose Sapropterin in Irish Adults with Mild Phenylketonuria. JIMD Reports, Volume 40 2018, 71-76. [CrossRef]

- Hollander, S.; Viau, K.; Sacharow, S., Pegvaliase dosing in adults with PKU: Requisite dose for efficacy decreases over time. Mol Genet Metab 2022, 137 (1-2), 104-106. [CrossRef]

- Mahan, K. C.; Gandhi, M. A.; Anand, S., Pegvaliase: a novel treatment option for adults with phenylketonuria. Curr Med Res Opin 2019, 35 (4), 647-651. [CrossRef]

- Bozaci, A. E.; Er, E.; Yazici, H.; Canda, E.; Kalkan Uçar, S.; Güvenc Saka, M.; Eraslan, C.; Onay, H.; Habif, S.; Thöny, B., et al., Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiencies: Lesson from clinical experience. JIMD Rep 2021, 59 (1), 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Fino, E.; Barbato, A.; Scaturro, G. M.; Procopio, E.; Balestrini, S., DNAJC12 deficiency: Mild hyperphenylalaninemia and neurological impairment in two siblings. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 2023, 37, 101008. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Basit, J.; Rehman, M. E. U., Adequacy of nitisinone for the management of alkaptonuria. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 80, 104340. [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, L. R.; Milan, A. M.; Hughes, A. T.; Khedr, M.; Norman, B. P.; Alsbou, M.; Imrich, R.; Gornall, M.; Sireau, N.; Gallagher, J. A., et al., Comparing nitisinone 2 mg and 10 mg in the treatment of alkaptonuria-An approach using statistical modelling. JIMD Rep 2022, 63 (1), 80-92. [CrossRef]

- Das, A. M., Clinical utility of nitisinone for the treatment of hereditary tyrosinemia type-1 (HT-1). Appl Clin Genet 2017, 10, 43-48. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R. P., CHAPTER 32 - Metabolic Liver Disease: Tyrosinemia, Galactosemia, and Hereditary Fructose Intolerance. In Pediatric Gastroenterology, Liacouras, C. A.; Piccoli, D. A.; Bell, L. M., Eds. Mosby: Philadelphia, 2008; pp 267-275.

- Introne, W. J.; Perry, M.; Chen, M., Alkaptonuria. In GeneReviews(®), Adam, M. P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G. M.; Pagon, R. A.; Wallace, S. E.; Amemiya, A., Eds. University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993-2025, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.: Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Sharabi, A. F.; Goudar, R. B., Alkaptonuria. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Teke Kisa, P.; Eroglu Erkmen, S.; Bahceci, H.; Arslan Gulten, Z.; Aydogan, A.; Karalar Pekuz, O. K.; Yuce Inel, T.; Ozturk, T.; Uysal, S.; Arslan, N., Efficacy of Phenylalanine- and Tyrosine-Restricted Diet in Alkaptonuria Patients on Nitisinone Treatment: Case Series and Review of Literature. Ann Nutr Metab 2022, 78 (1), 48-60. [CrossRef]

- Morrow, G.; Tanguay, R. M., Biochemical and Clinical Aspects of Hereditary Tyrosinemia Type 1. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 959, 9-21. [CrossRef]

- van Ginkel, W. G.; Pennings, J. P.; van Spronsen, F. J., Liver Cancer in Tyrosinemia Type 1. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 959, 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Chinsky, J. M.; Singh, R.; Ficicioglu, C.; van Karnebeek, C. D. M.; Grompe, M.; Mitchell, G.; Waisbren, S. E.; Gucsavas-Calikoglu, M.; Wasserstein, M. P.; Coakley, K., et al., Diagnosis and treatment of tyrosinemia type I: a US and Canadian consensus group review and recommendations. Genet Med 2017, 19 (12). [CrossRef]

- Čulic, V.; Betz, R. C.; Refke, M.; Fumic, K.; Pavelic, J., Tyrosinemia type II (Richner–Hanhart syndrome): A new mutation in the TAT gene. European Journal of Medical Genetics 2011, 54 (3), 205-208. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Quintana, L.; Scherer, G.; Curbelo-Estévez, M. L.; Jiménez-Acosta, F.; Hartmann, B.; La Roche, F.; Meavilla-Olivas, S.; Pérez-Cerdá, C.; García-Segarra, N.; Giguère, Y., et al., Tyrosinemia type II: Mutation update, 11 novel mutations and description of 5 independent subjects with a novel founder mutation. Clinical Genetics 2017, 92 (3), 306-317. [CrossRef]

- Russo, P. A.; Mitchell, G. A.; Tanguay, R. M., Tyrosinemia: a review. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2001, 4 (3), 212-21. [CrossRef]

- Rüetschi, U.; Cerone, R.; Pérez-Cerda, C.; Schiaffino, M. C.; Standing, S.; Ugarte, M.; Holme, E., Mutations in the 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase gene (HPD) in patients with tyrosinemia type III. Hum Genet 2000, 106 (6), 654-62. [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, E.; Sredzinska, M.; Ciara, E.; Piekutowska-Abramczuk, D.; Ploski, R.; Rokicki, D.; Tylki-Szymanska, A., Tyrosinemia type III in an asymptomatic girl. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 2015, 5, 48-50. [CrossRef]

- Barroso, F.; Correia, J.; Bandeira, A.; Carmona, C.; Vilarinho, L.; Almeida, M.; Rocha, J. C.; Martins, E., TYROSINEMIA TYPE III: A CASE REPORT OF SIBLINGS AND LITERATURE REVIEW. Rev Paul Pediatr 2020, 38, e2018158. [CrossRef]

- Sellos-Moura, M.; Glavin, F.; Lapidus, D.; Evans, K.; Lew, C. R.; Irwin, D. E., Prevalence, characteristics, and costs of diagnosed homocystinuria, elevated homocysteine, and phenylketonuria in the United States: a retrospective claims-based comparison. BMC Health Services Research 2020, 20 (1), 183. [CrossRef]

- Weber Hoss, G. R.; Sperb-Ludwig, F.; Schwartz, I. V. D.; Blom, H. J., Classical homocystinuria: A common inborn error of metabolism? An epidemiological study based on genetic databases. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020, 8 (6), e1214. [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, A.; Dawson, C., Homocystinuria diagnosis and management: it is not all classical. J Clin Pathol 2022. [CrossRef]

- Aljassim, N.; Alfadhel, M.; Nashabat, M.; Eyaid, W., Clinical presentation of seven patients with Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 2020, 25, 100644. [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. A.; Kožich, V.; Santra, S.; Andria, G.; Ben-Omran, T. I.; Chakrapani, A. B.; Crushell, E.; Henderson, M. J.; Hochuli, M.; Huemer, M., et al., Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis 2017, 40 (1), 49-74. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Power, B.; Abedin, A.; Purcell, O.; Knerr, I.; Monavari, A., Plasma methionine concentrations and incidence of hypermethioninemic encephalopathy during infancy in a large cohort of 36 patients with classical homocystinuria in the Republic of Ireland. JIMD Rep 2019, 47 (1), 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Ludolph, A. C.; Masur, H.; Oberwittler, C.; Koch, H. G.; Ullrich, K., Sensory neuropathy and vitamin B6 treatment in homocystinuria. European Journal of Pediatrics 1993, 152 (3), 271-271. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K. A.; Morton, D. H.; Puffenberger, E. G.; Hendrickson, C.; Robinson, D. L.; Wagner, C.; Stabler, S. P.; Allen, R. H.; Chwatko, G.; Jakubowski, H., et al., Prevention of brain disease from severe 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2007, 91 (2), 165-75. [CrossRef]

- Furujo, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Nagao, M.; Kubo, T., S-adenosylmethionine treatment in methionine adenosyltransferase deficiency, a case report. Mol Genet Metab 2012, 105 (3), 516-8. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chang, R.; Abdenur, J. E., The biochemical profile and dietary management in S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2022, 32, 100885. [CrossRef]

- Elmonem, M. A.; Veys, K. R.; Soliman, N. A.; van Dyck, M.; van den Heuvel, L. P.; Levtchenko, E., Cystinosis: a review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2016, 11 (1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Head, P. E.; Meier, J. L.; Venditti, C. P., New insights into the pathophysiology of methylmalonic acidemia. J Inherit Metab Dis 2023, 46 (3), 436-449. [CrossRef]

- Forny, P.; Hörster, F.; Ballhausen, D.; Chakrapani, A.; Chapman, K. A.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Dixon, M.; Grünert, S. C.; Grunewald, S.; Haliloglu, G., et al., Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic acidaemia and propionic acidaemia: First revision. J Inherit Metab Dis 2021, 44 (3), 566-592. [CrossRef]

- Manoli, I.; Sloan, J. L.; Venditti, C. P., Isolated Methylmalonic Acidemia. In GeneReviews(®), Adam, M. P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G. M.; Pagon, R. A.; Wallace, S. E.; Amemiya, A., Eds. University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993-2025, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.: Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Zhou, X.; Cui, Y.; Han, J., Methylmalonic acidemia: Current status and research priorities. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2018, 7 (2), 73-78. [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.; Burrage, L. C.; Chapman, K. A.; Ginevic, I.; Mazariegos, G. V.; Graham, B. H., Solid organ transplantation in methylmalonic acidemia and propionic acidemia: A points to consider statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine 2023, 25 (2). [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.; Arnoux, J.-B.; Bienaimé, F.; Brassier, A.; Brazier, F.; Benoist, J.-F.; Pontoizeau, C.; Ottolenghi, C.; Krug, P.; Boyer, O., et al., Long-term renal outcome in methylmalonic acidemia in adolescents and adults. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2021, 16 (1), 220. [CrossRef]

- Marelli, C.; Fouilhoux, A.; Benoist, J.-F.; De Lonlay, P.; Guffon-Fouilhoux, N.; Brassier, A.; Cano, A.; Chabrol, B.; Pennisi, A.; Schiff, M., et al., Very long-term outcomes in 23 patients with cblA type methylmalonic acidemia. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2022, 45 (5), 937-951. [CrossRef]

- Morton, D. H.; Strauss, K. A.; Robinson, D. L.; Puffenberger, E. G.; Kelley, R. I., Diagnosis and treatment of maple syrup disease: a study of 36 patients. Pediatrics 2002, 109 (6), 999-1008. [CrossRef]

- Frazier, D. M.; Allgeier, C.; Homer, C.; Marriage, B. J.; Ogata, B.; Rohr, F.; Splett, P. L.; Stembridge, A.; Singh, R. H., Nutrition management guideline for maple syrup urine disease: An evidence- and consensus-based approach. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2014, 112 (3), 210-217. [CrossRef]

- Ziadlou, M.; MacDonald, A., Alternative sources of valine and isoleucine for prompt reduction of plasma leucine in maple syrup urine disease patients: A case series. JIMD Rep 2022, 63 (6), 555-562. [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, W. L.; Rice-Kelts, M.; Klein, J.; Barshop, B. A., Treatment of the acute crisis in maple syrup urine disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998, 152 (6), 593-8. [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, D.; Crushell, E.; Hughes, J.; Ryan, S.; Rogers, Y.; Borovickova, I.; Mayne, P.; Riordan, M.; Awan, A.; Carson, K., et al., Maple syrup urine disease: Clinical outcomes, metabolic control, and genotypes in a screened population after four decades of newborn bloodspot screening in the Republic of Ireland. J Inherit Metab Dis 2021, 44 (3), 639-655. [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, P. R.; Gass, J. M.; Vairo, F. P. E.; Farnham, K. M.; Atwal, H. K.; Macklin, S.; Klee, E. W.; Atwal, P. S., Maple syrup urine disease: mechanisms and management. Appl Clin Genet 2017, 10, 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, C. R., 2nd; Swanson, M. A.; Kronquist, K.; Acquaviva, C.; Hutchin, T.; Rodríguez-Pombo, P.; Väisänen, M. L.; Spector, E.; Creadon-Swindell, G.; Brás-Goldberg, A. M., et al., The genetic basis of classic nonketotic hyperglycinemia due to mutations in GLDC and AMT. Genet Med 2017, 19 (1), 104-111. [CrossRef]

- Hennermann, J. B.; Berger, J. M.; Grieben, U.; Scharer, G.; Van Hove, J. L., Prediction of long-term outcome in glycine encephalopathy: a clinical survey. J Inherit Metab Dis 2012, 35 (2), 253-61. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Chuchra, P.; Paprocka, J., Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia: Insight into Current Therapies. J Clin Med 2022, 11 (11). [CrossRef]

- Forget, P.; le Polain de Waroux, B.; Wallemacq, P.; Gala, J. L., Life-threatening dextromethorphan intoxication associated with interaction with amitriptyline in a poor CYP2D6 metabolizer: a single case re-exposure study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008, 36 (1), 92-6. [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, E. J.; Poplawski, N. K.; Harrison, J. R.; Fletcher, J. M., Treatment of late-onset nonketotic hyperglycinaemia: effectiveness of imipramine and benzoate. J Inherit Metab Dis 2000, 23 (1), 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Van Hove, J. L.; Vande Kerckhove, K.; Hennermann, J. B.; Mahieu, V.; Declercq, P.; Mertens, S.; De Becker, M.; Kishnani, P. S.; Jaeken, J., Benzoate treatment and the glycine index in nonketotic hyperglycinaemia. J Inherit Metab Dis 2005, 28 (5), 651-63. [CrossRef]

- Van Hove, J. L. K.; Coughlin, C., II; Swanson, M.; Hennermann, J. B., Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia. In GeneReviews(®), Adam, M. P.; Feldman, J.; Mirzaa, G. M.; Pagon, R. A.; Wallace, S. E.; Amemiya, A., Eds. University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993-2025, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved.: Seattle (WA), 1993.

- Coughlin, C. R., 2nd; Tseng, L. A.; Abdenur, J. E.; Ashmore, C.; Boemer, F.; Bok, L. A.; Boyer, M.; Buhas, D.; Clayton, P. T.; Das, A., et al., Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy due to α-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis 2021, 44 (1), 178-192. [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaie, L.; Klomp, L. W.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M. E.; Spaapen, L. J.; Haagen, A. A.; Dorland, L.; de Koning, T. J., Expanding the clinical spectrum of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34 (1), 181-4. [CrossRef]

- van der Crabben, S. N.; Verhoeven-Duif, N. M.; Brilstra, E. H.; Van Maldergem, L.; Coskun, T.; Rubio-Gozalbo, E.; Berger, R.; de Koning, T. J., An update on serine deficiency disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis 2013, 36 (4), 613-9. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin Ii, C. R.; Gospe Jr, S. M., Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy: Current perspectives and questions for future research. Annals of the Child Neurology Society 2023, 1 (1), 24-37. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, C. R., 2nd; Swanson, M. A.; Spector, E.; Meeks, N. J. L.; Kronquist, K. E.; Aslamy, M.; Wempe, M. F.; van Karnebeek, C. D. M.; Gospe, S. M., Jr.; Aziz, V. G., et al., The genotypic spectrum of ALDH7A1 mutations resulting in pyridoxine dependent epilepsy: A common epileptic encephalopathy. J Inherit Metab Dis 2019, 42 (2), 353-361. [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, T.; Venghaus, A.; Zerres, K., Cystinuria: an inborn cause of urolithiasis. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2012, 7 (1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Pak, C. Y.; Fuller, C.; Sakhaee, K.; Zerwekh, J. E.; Adams, B. V., Management of cystine nephrolithiasis with alpha-mercaptopropionylglycine. J Urol 1986, 136 (5), 1003-8. [CrossRef]

- Gillion, V.; Saussez, T. P.; Van Nieuwenhove, S.; Jadoul, M., Extremely rapid stone formation in cystinuria: look out for dietary supplements! Clin Kidney J 2021, 14 (6), 1694-1696. [CrossRef]

- Sahota, A.; Tischfield, J. A.; Goldfarb, D. S.; Ward, M. D.; Hu, L., Cystinuria: genetic aspects, mouse models, and a new approach to therapy. Urolithiasis 2019, 47 (1), 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, S.; Cil, O., Cystinuria: An Overview of Diagnosis and Medical Management. Turk Arch Pediatr 2022, 57 (4), 377-384. [CrossRef]

- Sebastio, G.; Sperandeo, M. P.; Andria, G., Lysinuric protein intolerance: reviewing concepts on a multisystem disease. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2011, 157c (1), 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Piña-Garza, J. E.; James, K. C., Ataxia. In Fenichel's Clinical Pediatric Neurology (Eighth Edition), 8 ed.; Piña-Garza, J. E.; James, K. C., Eds. Elsevier: Philadelphia, 2019; pp 218-237.

- Nyhan, W. L.; Rice-Kelts, M.; Klein, J.; Barshop, B. A., Treatment of the Acute Crisis in Maple Syrup Urine Disease. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 1998, 152 (6), 593-598. [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, D.; Crushell, E.; Hughes, J.; Ryan, S.; Rogers, Y.; Borovickova, I.; Mayne, P.; Riordan, M.; Awan, A.; Carson, K., et al., Maple syrup urine disease: Clinical outcomes, metabolic control, and genotypes in a screened population after four decades of newborn bloodspot screening in the Republic of Ireland. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2021, 44 (3), 639-655. [CrossRef]

- Rajantie, J.; Simell, O.; Rapola, J.; Perheentupa, J., Lysinuric protein intolerance: a two-year trial of dietary supplementation therapy with citrulline and lysine. J Pediatr 1980, 97 (6), 927-32. [CrossRef]

- Kleta, R.; Romeo, E.; Ristic, Z.; Ohura, T.; Stuart, C.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Dave, M. H.; Wagner, C. A.; Camargo, S. R. M.; Inoue, S., et al., Mutations in SLC6A19, encoding B0AT1, cause Hartnup disorder. Nature Genetics 2004, 36 (9), 999-1002. [CrossRef]

- Kravetz, Z.; Schmidt-Kastner, R., New aspects for the brain in Hartnup disease based on mining of high-resolution cellular mRNA expression data for SLC6A19. IBRO Neuroscience Reports 2023, 14, 393-397. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. B.; Prabhu, A. S., Hartnup disease. Indian J Dermatol 2008, 53 (1), 31-2. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, T.; Faust, H.; Abou Jamra, R.; Pott, C.; Kluge, M.; Rumpf, J. J.; Then Bergh, F.; Beblo, S., Adult Neuropsychiatric Manifestation of Hartnup Disease With a Novel SLCA6A19 Variant: A Case Report. Neurol Genet 2024, 10 (6), e200195. [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M. S.; Gupta, V., Hartnup Disease. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Kölker, S.; Christensen, E.; Leonard, J. V.; Greenberg, C. R.; Boneh, A.; Burlina, A. B.; Burlina, A. P.; Dixon, M.; Duran, M.; García Cazorla, A., et al., Diagnosis and management of glutaric aciduria type I--revised recommendations. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34 (3), 677-94. [CrossRef]

- Rai, S. P., Glutaric aciduria type1: CT diagnosis. J Pediatr Neurosci 2009, 4 (2), 143. [CrossRef]

- Vester, M. E. M.; Bilo, R. A. C.; Karst, W. A.; Daams, J. G.; Duijst, W. L. J. M.; van Rijn, R. R., Subdural hematomas: glutaric aciduria type 1 or abusive head trauma? A systematic review. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology 2015, 11 (3), 405-415. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Pillay, R. S., Striatal necrosis in type 1 glutaric aciduria: Different stages in two siblings. Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences 2011, 6 (2).

- Lipkin, P. H.; Roe, C. R.; Goodman, S. I.; Batshaw, M. L., A case of glutaric acidemia type I: Effect of riboflavin and carnitine. The Journal of Pediatrics 1988, 112 (1), 62-65. [CrossRef]

- Seccombe, D. W.; James, L.; Booth, F., L-Carnitine treatment in glutaric aciduria type I. Neurology 1986, 36 (2), 264-264. [CrossRef]

- Kölker, S.; Garbade, S. F.; Boy, N.; Maier, E. M.; Meissner, T.; Mühlhausen, C.; Hennermann, J. B.; Lücke, T.; Häberle, J.; Baumkötter, J., et al., Decline of Acute Encephalopathic Crises in Children with Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency Identified by Newborn Screening in Germany. Pediatric Research 2007, 62 (3), 357-363. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K. A.; Puffenberger, E. G.; Robinson, D. L.; Morton, D. H., Type I glutaric aciduria, part 1: Natural history of 77 patients. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 2003, 121C (1), 38-52. [CrossRef]

- Boy, N.; Mühlhausen, C.; Maier, E. M.; Ballhausen, D.; Baumgartner, M. R.; Beblo, S.; Burgard, P.; Chapman, K. A.; Dobbelaere, D.; Heringer-Seifert, J., et al., Recommendations for diagnosing and managing individuals with glutaric aciduria type 1: Third revision. J Inherit Metab Dis 2023, 46 (3), 482-519. [CrossRef]

- Foran, J.; Moore, M.; Crushell, E.; Knerr, I.; McSweeney, N., Low excretor glutaric aciduria type 1 of insidious onset with dystonia and atypical clinical features, a diagnostic dilemma. JIMD Rep 2021, 58 (1), 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Tondo, M.; Calpena, E.; Arriola, G.; Sanz, P.; Martorell, L.; Ormazabal, A.; Castejon, E.; Palacin, M.; Ugarte, M.; Espinos, C., et al., Clinical, biochemical, molecular and therapeutic aspects of 2 new cases of 2-aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase deficiency. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2013, 110 (3), 231-236. [CrossRef]

- Houten, S. M.; te Brinke, H.; Denis, S.; Ruiter, J. P. N.; Knegt, A. C.; de Klerk, J. B. C.; Augoustides-Savvopoulou, P.; Häberle, J.; Baumgartner, M. R.; Coşkun, T., et al., Genetic basis of hyperlysinemia. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2013, 8 (1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Marinella, G.; Pascarella, F.; Vetro, A.; Bonuccelli, A.; Pochiero, F.; Santangelo, A.; Alessandrì, M. G.; Pasquariello, R.; Orsini, A.; Battini, R., Hyperlysinemia, an ultrarare inborn error of metabolism: Review and update. Seizure - European Journal of Epilepsy 2024, 120, 135-141. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. R.; van Karnebeek, C. D. M., Inborn errors of metabolism. Handb Clin Neurol 2019, 162, 449-481. [CrossRef]

- Hart, C. E.; Race, V.; Achouri, Y.; Wiame, E.; Sharrard, M.; Olpin, S. E.; Watkinson, J.; Bonham, J. R.; Jaeken, J.; Matthijs, G., et al., Phosphoserine aminotransferase deficiency: a novel disorder of the serine biosynthesis pathway. Am J Hum Genet 2007, 80 (5), 931-7. [CrossRef]

- Guilmatre, A.; Legallic, S.; Steel, G.; Willis, A.; Di Rosa, G.; Goldenberg, A.; Drouin-Garraud, V.; Guet, A.; Mignot, C.; Des Portes, V., et al., Type I hyperprolinemia: genotype/phenotype correlations. Hum Mutat 2010, 31 (8), 961-5. [CrossRef]

- Bender, H. U.; Almashanu, S.; Steel, G.; Hu, C. A.; Lin, W. W.; Willis, A.; Pulver, A.; Valle, D., Functional consequences of PRODH missense mutations. Am J Hum Genet 2005, 76 (3), 409-20. [CrossRef]

- Clelland, C. L.; Read, L. L.; Baraldi, A. N.; Bart, C. P.; Pappas, C. A.; Panek, L. J.; Nadrich, R. H.; Clelland, J. D., Evidence for association of hyperprolinemia with schizophrenia and a measure of clinical outcome. Schizophr Res 2011, 131 (1-3), 139-45. [CrossRef]

- Mitsubuchi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Endo, F., Biochemical and clinical features of hereditary hyperprolinemia. Pediatrics International 2014, 56 (4), 492-496. [CrossRef]

- Namavar, Y.; Duineveld, D. J.; Both, G. I. A.; Fiksinski, A. M.; Vorstman, J. A. S.; Verhoeven-Duif, N. M.; Zinkstok, J. R., Psychiatric phenotypes associated with hyperprolinemia: A systematic review. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2021, 186 (5), 289-317. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, D.; Häberle, J.; Rubio, V.; Giunta, C.; Hausser, I.; Carrozzo, R.; Gougeard, N.; Marco-Marín, C.; Goffredo, B. M.; Meschini, M. C., et al., Understanding pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase deficiency: clinical, molecular, functional, and expression studies, structure-based analysis, and novel therapy with arginine. J Inherit Metab Dis 2012, 35 (5), 761-76. [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, S.; Gardeitchik, T.; Kouwenberg, D.; Kluijtmans, L.; Wevers, R.; Morava, E., Long-term clinical outcome, therapy and mild mitochondrial dysfunction in hyperprolinemia. J Inherit Metab Dis 2014, 37 (3), 383-90. [CrossRef]

- Balfoort, B. M.; Buijs, M. J. N.; ten Asbroek, A. L. M. A.; Bergen, A. A. B.; Boon, C. J. F.; Ferreira, E. A.; Houtkooper, R. H.; Wagenmakers, M. A. E. M.; Wanders, R. J. A.; Waterham, H. R., et al., A review of treatment modalities in gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina (GACR). Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2021, 134 (1), 96-116. [CrossRef]

- Häberle, J.; Boddaert, N.; Burlina, A.; Chakrapani, A.; Dixon, M.; Huemer, M.; Karall, D.; Martinelli, D.; Crespo, P. S.; Santer, R., et al., Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012, 7, 32. [CrossRef]

- Häberle, J.; Shahbeck, N.; Ibrahim, K.; Hoffmann, G. F.; Ben-Omran, T., Natural course of glutamine synthetase deficiency in a 3year old patient. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2011, 103 (1), 89-91. [CrossRef]

- Spodenkiewicz, M.; Diez-Fernandez, C.; Rüfenacht, V.; Gemperle-Britschgi, C.; Häberle, J., Minireview on Glutamine Synthetase Deficiency, an Ultra-Rare Inborn Error of Amino Acid Biosynthesis. Biology (Basel) 2016, 5 (4). [CrossRef]

- Häberle, J.; Shahbeck, N.; Ibrahim, K.; Schmitt, B.; Scheer, I.; O’Gorman, R.; Chaudhry, F. A.; Ben-Omran, T., Glutamine supplementation in a child with inherited GS deficiency improves the clinical status and partially corrects the peripheral and central amino acid imbalance. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2012, 7 (1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Alfadhel, M.; Alrifai, M. T.; Trujillano, D.; Alshaalan, H.; Al Othaim, A.; Al Rasheed, S.; Assiri, H.; Alqahtani, A. A.; Alaamery, M.; Rolfs, A., et al., Asparagine Synthetase Deficiency: New Inborn Errors of Metabolism. JIMD Rep 2015, 22, 11-6. [CrossRef]

- Sacharow, S. J.; Dudenhausen, E. E.; Lomelino, C. L.; Rodan, L.; El Achkar, C. M.; Olson, H. E.; Genetti, C. A.; Agrawal, P. B.; McKenna, R.; Kilberg, M. S., Characterization of a novel variant in siblings with Asparagine Synthetase Deficiency. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2018, 123 (3), 317-325. [CrossRef]

- van Wegberg, A. M. J.; MacDonald, A.; Ahring, K.; Bélanger-Quintana, A.; Beblo, S.; Blau, N.; Bosch, A. M.; Burlina, A.; Campistol, J.; Coşkun, T., et al., European guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of phenylketonuria: First revision. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2025, 145 (2), 109125. [CrossRef]

- Altman, G.; Hussain, K.; Green, D.; Strauss, B. J. G.; Wilcox, G., Mental health diagnoses in adults with phenylketonuria: a retrospective systematic audit in a large UK single centre. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2021, 16 (1), 520. [CrossRef]

- ten Hoedt, A. E.; de Sonneville, L. M.; Francois, B.; ter Horst, N. M.; Janssen, M. C.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M. E.; Wijburg, F. A.; Hollak, C. E.; Bosch, A. M., High phenylalanine levels directly affect mood and sustained attention in adults with phenylketonuria: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34 (1), 165-71. [CrossRef]

- Gersting, S. W.; Staudigl, M.; Truger, M. S.; Messing, D. D.; Danecka, M. K.; Sommerhoff, C. P.; Kemter, K. F.; Muntau, A. C., Activation of phenylalanine hydroxylase induces positive cooperativity toward the natural cofactor. J Biol Chem 2010, 285 (40), 30686-97. [CrossRef]

- Trefz, F. K.; Burton, B. K.; Longo, N.; Casanova, M. M.; Gruskin, D. J.; Dorenbaum, A.; Kakkis, E. D.; Crombez, E. A.; Grange, D. K.; Harmatz, P., et al., Efficacy of sapropterin dihydrochloride in increasing phenylalanine tolerance in children with phenylketonuria: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pediatr 2009, 154 (5), 700-7. [CrossRef]

- Camp, K. M.; Parisi, M. A.; Acosta, P. B.; Berry, G. T.; Bilder, D. A.; Blau, N.; Bodamer, O. A.; Brosco, J. P.; Brown, C. S.; Burlina, A. B., et al., Phenylketonuria Scientific Review Conference: state of the science and future research needs. Mol Genet Metab 2014, 112 (2), 87-122. [CrossRef]

- Burton, B. K.; Grange, D. K.; Milanowski, A.; Vockley, G.; Feillet, F.; Crombez, E. A.; Abadie, V.; Harding, C. O.; Cederbaum, S.; Dobbelaere, D., et al., The response of patients with phenylketonuria and elevated serum phenylalanine to treatment with oral sapropterin dihydrochloride (6R-tetrahydrobiopterin): a phase II, multicentre, open-label, screening study. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007, 30 (5), 700-7. [CrossRef]

- Hennermann, J. B.; Roloff, S.; Gebauer, C.; Vetter, B.; von Arnim-Baas, A.; Mönch, E., Long-term treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin in phenylketonuria: treatment strategies and prediction of long-term responders. Mol Genet Metab 2012, 107 (3), 294-301. [CrossRef]

- Scala, I.; Concolino, D.; Casa, R. D.; Nastasi, A.; Ungaro, C.; Paladino, S.; Capaldo, B.; Ruoppolo, M.; Daniele, A.; Bonapace, G., et al., Long-term follow-up of patients with phenylketonuria treated with tetrahydrobiopterin: a seven years experience. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2015, 10 (1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Hydery, T.; Coppenrath, V. A., A Comprehensive Review of Pegvaliase, an Enzyme Substitution Therapy for the Treatment of Phenylketonuria. Drug Target Insights 2019, 13, 1177392819857089. [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, O.; Daha, M.; Longo, N.; Knol, E.; Müller, I.; Northrup, H.; Brockow, K., Pegvaliase: Immunological profile and recommendations for the clinical management of hypersensitivity reactions in patients with phenylketonuria treated with this enzyme substitution therapy. Mol Genet Metab 2019, 128 (1-2), 84-91. [CrossRef]

- Harding, C. O.; Amato, R. S.; Stuy, M.; Longo, N.; Burton, B. K.; Posner, J.; Weng, H. H.; Merilainen, M.; Gu, Z.; Jiang, J., et al., Pegvaliase for the treatment of phenylketonuria: A pivotal, double-blind randomized discontinuation Phase 3 clinical trial. Mol Genet Metab 2018, 124 (1), 20-26. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.; Rohr, F.; Splett, P.; Mofidi, S.; Bausell, H.; Stembridge, A.; Kenneson, A.; Singh, R. H., Nutrition management of PKU with pegvaliase therapy: update of the web-based PKU nutrition management guideline recommendations. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2023, 18 (1), 155. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A. M.; Burlina, A.; Cunningham, A.; Bettiol, E.; Moreau-Stucker, F.; Koledova, E.; Benmedjahed, K.; Regnault, A., Assessment of the impact of phenylketonuria and its treatment on quality of life of patients and parents from seven European countries. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015, 10, 80. [CrossRef]

- Bik-Multanowski, M.; Didycz, B.; Mozrzymas, R.; Nowacka, M.; Kaluzny, L.; Cichy, W.; Schneiberg, B.; Amilkiewicz, J.; Bilar, A.; Gizewska, M., et al., Quality of life in noncompliant adults with phenylketonuria after resumption of the diet. J Inherit Metab Dis 2008, 31 Suppl 2, S415-8. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.; Murphy, E.; Maritz, C.; Chan, H.; Ellerton, C.; Carpenter, R. H.; Lachmann, R. H., Dietary treatment of phenylketonuria: the effect of phenylalanine on reaction time. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34 (2), 449-54. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.; Murphy, E.; Maritz, C.; Chan, H.; Ellerton, C.; Carpenter, R. H. S.; Lachmann, R. H., Dietary treatment of phenylketonuria: the effect of phenylalanine on reaction time. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2011, 34 (2), 449-454. [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, J. D.; Fernstrom, M. H., Tyrosine, Phenylalanine, and Catecholamine Synthesis and Function in the Brain123. The Journal of Nutrition 2007, 137 (6), 1539S-1547S. [CrossRef]

- Sara, G.-L.; Alejandra, L.-M. L.; Isabel, I.-G.; Marcela, V.-A., Conventional Phenylketonuria Treatment. Journal of Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Screening 2016, 4, 2326409816685733. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, P.; Matalon, K. M., Nutrition management of patients with inherited disorders of aromatic amino acid metabolism. In Nutrition Management of Patients with Inherited Metabolic Disorders, Acosta, P. B., Ed. Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, Massachusetts, 2010; pp 119-153.

- Webster, D.; Wildgoose, J., Tyrosine supplementation for phenylketonuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013, 2013 (6), Cd001507. [CrossRef]

- Remmington, T.; Smith, S., Tyrosine supplementation for phenylketonuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021, 1 (1), Cd001507. [CrossRef]

- Orzincolo, C.; Castaldi, G.; Scutellari, P. N.; Cicognani, P.; Bariani, L.; Feggi, L., [Ochronotic arthropathy in alkaptonuria. Radiological manifestations and physiopathological signs]. Radiol Med 1988, 75 (5), 476-81.

- Ranga, U.; Aiyappan, S. K.; Shanmugam, N.; Veeraiyan, S., Ochronotic spondyloarthropathy. J Clin Diagn Res 2013, 7 (2), 403-4. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, I. C.; Hoang, T. D.; Vietor, N. O.; Schacht, J. P.; Shakir, M. K. M., Dilemmas in the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in a patient with alkaptonuria: Successful treatment with teriparatide. Clinical Case Reports 2022, 10 (12), e6729. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J. A.; Barshop, B.; Nyhan, W. L.; Leslie, J.; Seegmiller, J. E.; Gruber, H.; Garst, M.; Winter, S.; Michals, K.; Matalon, R., Effects of Ascorbic Acid in Alkaptonuria: Alterations in Benzoquinone Acetic Acid and an Ontogenic Effect in Infancy. Pediatric Research 1989, 26 (2), 140-144. [CrossRef]

- Feier, F.; Schwartz, I. V.; Benkert, A. R.; Seda Neto, J.; Miura, I.; Chapchap, P.; da Fonseca, E. A.; Vieira, S.; Zanotelli, M. L.; Pinto e Vairo, F., et al., Living related versus deceased donor liver transplantation for maple syrup urine disease. Mol Genet Metab 2016, 117 (3), 336-43. [CrossRef]

- Pontoizeau, C.; Simon-Sola, M.; Gaborit, C.; Nguyen, V.; Rotaru, I.; Tual, N.; Colella, P.; Girard, M.; Biferi, M. G.; Arnoux, J. B., et al., Neonatal gene therapy achieves sustained disease rescue of maple syrup urine disease in mice. Nat Commun 2022, 13 (1), 3278. [CrossRef]

- Walther, F.; Radke, M.; KrÜGer, G.; Hobusch, D.; Uhlemann, M.; Tittelbach-Helmrich, W.; Stolpe, H. J., Response to sodium benzoate treatment in non-ketotic hyperglycinaemia. Pediatrics International 1994, 36 (1), 75-79. [CrossRef]

- Shelkowitz, E.; Saneto, R. P.; Al-Hertani, W.; Lubout, C. M. A.; Stence, N. V.; Brown, M. S.; Long, P.; Walleigh, D.; Nelson, J. A.; Perez, F. E., et al., Ketogenic diet as a glycine lowering therapy in nonketotic hyperglycinemia and impact on brain glycine levels. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2022, 17 (1), 423. [CrossRef]

- Bjoraker, K. J.; Swanson, M. A.; Coughlin, C. R., 2nd; Christodoulou, J.; Tan, E. S.; Fergeson, M.; Dyack, S.; Ahmad, A.; Friederich, M. W.; Spector, E. B., et al., Neurodevelopmental Outcome and Treatment Efficacy of Benzoate and Dextromethorphan in Siblings with Attenuated Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia. J Pediatr 2016, 170, 234-9. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kim, D., Toxic Metabolites and Inborn Errors of Amino Acid Metabolism: What One Informs about the Other. Metabolites 2022, 12 (6). [CrossRef]

- van Karnebeek, C. D.; Hartmann, H.; Jaggumantri, S.; Bok, L. A.; Cheng, B.; Connolly, M.; Coughlin, C. R., 2nd; Das, A. M.; Gospe, S. M., Jr.; Jakobs, C., et al., Lysine restricted diet for pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy: first evidence and future trials. Mol Genet Metab 2012, 107 (3), 335-44. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, C. R.; Tseng, L. A.; Bok, L. A.; Hartmann, H.; Footitt, E.; Striano, P.; Tabarki, B. M.; Lunsing, R. J.; Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Gordon, S., et al., Association Between Lysine Reduction Therapies and Cognitive Outcomes in Patients With Pyridoxine-Dependent Epilepsy. Neurology 2022, 99 (23), e2627-e2636. [CrossRef]

- Kölker, S.; Boy, S. P. N.; Heringer, J.; Müller, E.; Maier, E. M.; Ensenauer, R.; Mühlhausen, C.; Schlune, A.; Greenberg, C. R.; Koeller, D. M., et al., Complementary dietary treatment using lysine-free, arginine-fortified amino acid supplements in glutaric aciduria type I — A decade of experience. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2012, 107 (1), 72-80. [CrossRef]

- Segur-Bailach, E.; Mateu-Bosch, A.; Bofill-De Ros, X.; Parés, M.; da Silva Buttkus, P.; Rathkolb, B.; Gailus-Durner, V.; Hrabě de Angelis, M.; Moeini, P.; Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza, G., et al., Therapeutic AASS inhibition by AAV-miRNA rescues glutaric aciduria type I severe phenotype in mice. Mol Ther 2025. [CrossRef]

| Disorder | Treatment | Rationale/ Mechanism |

Dose | Biochemical Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylketonuria (PKU) | Phenylalanine-free amino acid supplements Dietary restriction of phenylalanine |

To limit intake of offending amino acid | Small, frequent doses (3-4) spaced evenly across day [10]. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

| Sapropterin dihydrochloride (Kuvan®) | Synthetic form of cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). | Recommended starting dose in patients is 10 mg/kg body weight/day. Dose is adjusted, usually between 5-20 mg/kg/day, to achieve and maintain blood Phe control [11,12,13]. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

|

| Pegvaliase (Palynziq®) | Recombinant phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) enzyme (patients ≥ 16 yrs) | Recommended starting dose is 2.5mg once per week for 4 weeks. Dose escalated gradually based on tolerability to daily maintenance dose needed to achieve blood Phe control. Maintenance dose is individualised to achieve blood Phe control [9,14,15]. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

|

|

Biopterin defects causing hyperphenylalaninemia [101] |

Dietary restriction of phenylalanine (GTPCH and DHPR deficiency patients). Phenylalanine-free amino acid supplements. | To limit intake of offending amino acid | Small, frequent doses (3-4) spaced evenly across day [10]. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

| Sapropterin dihydrochloride (Kuvan®) (All BH4 deficiency patients) | Synthetic form of cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). | Recommended starting dose in adult patients is 10 mg/kg body weight/day. Dose is adjusted, usually between 5-20 mg/kg/day, to achieve and maintain blood phenylalanine control [8,11,12]. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

|

| l-3,4- dihydroxyphenylalanine/carbidopa (L-DOPA) and 5-OH-Tryptophan |

For neurotransmitter related movement disorders | L-DOPA in 4 divided doses with similar dosing for 5-OH-Tryptophan [16], age-dependent. | LP for CSF neurotransmitters measurement (HVA, 5-HIAA); prolactin levels. | |

| Folinic acid | For movement disorders, to prevent cerebral folate deficiency | 10-15mg/day [16] | Monitoring of CSF folate and folinic acid status | |

|

Hyperphenylalaninemia due to DNAJC12 |

Dietary restriction of phenylalanine. Phenylalanine-free amino acid supplements | To limit intake of offending amino acid | Small, frequent doses (3-4) spaced evenly across day [10]. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

| Sapropterin dihydrochloride (Kuvan®) | Synthetic form of cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). | Recommended starting dose in adult patients is 10 mg/kg body weight/day. Dose is adjusted, usually between 520 mg/kg/day, to achieve and maintain blood Phe control 8, 95, 126. | Blood phenylalanine levels |

|

| L-DOPA and Tryptophan | For neurotransmitter related movement disorder | Starting dose of 2.5mg/kg/day (can be increased to 6mg/kg/day) [17]. |

LP for CSF neurotransmitters measurement (HVA, 5-HIAA) | |

|

Alkaptonuria (AKU) |

Dietary restriction of phenylalanine. Tyrosine/phenylalanine-free amino acid supplements | To limit intake of offending amino acid. | Moderate restriction of natural protein | Plasma amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine) |

| Nitisinone (currently Nitisinone is approved for alkaptonuria treatment in adults only) |

Inhibits 4- hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase |

The recommended dose in the adult AKU population is 10 mg once daily [18,19]. | Plasma amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine) | |

| Bisphosphonate | Inhibit bone resorption by preventing hydroxyapatite breakdown | As clinically indicated | Bone turnover markers (BTMs) |

|

| Teriparatide | Activates PKA- and PKC-dependent signaling pathways | 20mcg/day SC (approved in adults) | BTMs, plasma calcium levels | |

|

Tyrosinemia type I |

Dietary restriction of phenylalanine and tyrosine. Tyrosine/phenylalanine-free amino acid supplements | To limit intake of offending amino acids | Plasma amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, methionine), liver function; blood/urine succinylacetone |

|

| Nitisinone (Nitisinone is approved for tyrosinemia type I treatment in children) |

Inhibits 4- hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase |

Recommended starting dose in adult patients is 1 mg/kg body weight/day. Dose should be adjusted individually. Maximum of dose of 2 mg/kg body weight/day [20,21]. |

Blood tyrosine levels, blood/urine succinylacetone; NTBC drug levels, liver function, alpha-fetoprotein |

|

| Liver transplant | If end-stage liver disease, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma develops | |||

| Tyrosinemia type II | Dietary restriction of phenylalanine and tyrosine. Tyrosine/phenylalanine-free amino acid supplements | To limit intake of offending amino acids | Blood tyrosine and phenylalanine levels | |

| Tyrosinemia type III | A restrictive tyrosine and phenylalanine diet has been suggested during childhood [20], while other authors argue that such restriction is not recommended |

| Disorder | Treatment | Rationale/mechanism | Dose | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Homocystinuria (HCU) due to cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) deficiency |

Methionine-free amino acid supplements. Dietary restriction of methionine/protein. Supplementation of cysteine, B12, folate. |

To limit intake of offending amino acid. | Individualised to patient. | Methionine and cystine levels. B12, folate. |

| Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) (In pyridoxine-responsive patients) | Co-factor of cystathionine β-synthase. | Recommended dose of up to 10 mg/kg/day. Recommended to avoid doses >500mg/day (risk of peripheral neuropathy) [38]. | Plasma tHcy. | |

| Betaine | Betaine donates a methyl group via betaine homocysteine methyl transferase (BHMT). | Recommended starting dose of 3g BID. Can increase up to 200mg/kg/day, rarely benefit to higher dose [38]. |

Plasma tHcy. | |

|

Homocystinuria due to methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency |

Betaine | Betaine donates a methyl group via betaine homocysteine methyl transferase (BHMT). | Recommended starting dose of 3g BID. Can increase up to 200mg/kg/day, rarely benefit to higher dose [38]. |

Plasma tHcy. |

| Aspirin | Antiplatelet therapy post stroke | 40mg/day [41] | Routine monitoring not recommended |

|

| Supplementation of creatine, B6, B12, folate, 5MTHF |

To achieve target plasma tHcy levels. | Creatine (75-100mg/kg/day), B6 (25mg/day), B12 (25mg/day), Folate (4mg/day) 5MTHF (2.4-3.2mg/day) [41] |

Creatinine, B6, B12, folate, 5MTHF levels |

|

|

Methionine S-adenosyltransferase deficiency |

S-adenosyl-L-methionine disulfate tosylate (SAM) supplementation |

For neurological manifestations | 400-800mg BD [42] | SAM concentration in plasma and CSF |

| Methionine-free amino acid supplements. Dietary restriction of methionine/protein |

To limit intake of offending amino acid (*Although may decrease S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) synthesis [108]) | Individualised to patient | Methionine levels. | |

| S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency | Methionine-free amino acid supplements. Dietary restriction of methionine/protein |

To limit intake of offending amino acids. To reduce toxic SAH levels. | Individualised to patient | Methionine levels. |

| Phosphatidylcholine and creatine supplementation | Low levels of creatine and choline in SAH hydrolase deficiency. | Creatine – e.g., 375 mg/kg/d Phosphatidylcholine – e.g., 150mg/kg/d [43] |

Creatinine, choline levels; blood/urine creatine | |

| Cystinosis | Cysteamine | Depletes lysosomal cystine levels | 1.30 g/m2/day; maximum of 1.95 g/m2/day [44] |

WBC cystine assay |

| Symptomatic treatment | Management of symptoms | E.g., ACE inhibitors for proteinuria, kidney transplant in ESRD, HRT for endocrinopathies. |

Depends on symptoms |

| Disorder | Treatment | Rationale/mechanism | Dose | Monitoring | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) |

Synthetic formula with all amino acids except leucine, isoleucine, valine. Valine and isoleucine supplementation. Protein-free foods. |

To limit intake of offending amino acids. | Valine:15- 30mg/kg Isoleucine: 10-30mg/kg [57], individualised to patient |

Plasma levels of BCAAs | |

| Thiamine (Vitamin B1) (In thiamine-responsive patients) |

Increases stability of branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex (BCKDC). | Additional Thiamine challenge of 150 -300 mg/day for one month. Continue thiamine supplementation in responsive patients [53]. |

Plasma levels of BCAAs | ||

| Liver transplantation | Hepatic enzyme replacement |

||||

| Management of acute crises: BCAA-free formula (PO or NG if not tolerating formula), provide all amino acids except leucine, supplement isoleucine and valine [23], reverse catabolism: increase calorie intake - IV calories (typically dextrose at high concentration), may start insulin drip if hyperglycaemic, use of normal or hypertonic saline, avoid hypotonic solutions, mannitol, diuretics, haemodialysis/haemofiltration | |||||

| Methylmalonic acidemia | Protein-restricted diet using synthetic propiogenic-devoid formulas | Reduce MMA production | Urine MMA, plasma amino acid concentrations | ||

| Hydroxocobalamin | Enhance activity of metyhlmalonyl-CoA mutase | 1mg intramuscularly, regular continuation depends on metabolic response [47]. | Urine MMA, plasma amino acid concentrations | ||

| Carnitine | To correct secondary carnitine deficiency | 50-100 mg/kg/day and up to ~300 mg/kg/day divided into 3-4 doses [47]. | Plasma free carnitine level, acylcarnitine profile in dried blood spots | ||

| Metronidazole | Reduce propionate production by gut flora | 10-15 mg/kg/day typically administered in 7–10 day courses every 1–3 months [47]. | Urine MMA, propionylcarnitine | ||

| Disorder | Treatment | Rationale/mechanism | Dose | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-ketotic hyperglycinemia (NKH) |

Ketogenic diet (High in fat and low in carbohydrates) *Must decrease sodium benzoate | Alternate energy source for brain, epilepsy treatment, glycine reduction | Blood glucose and ketones | |

| Sodium benzoate | Forms conjugated metabolite (hippurate) which is excreted by kidneys | Attenuated NKH - 200-550 mg/kg/day Severe NKH - 550-750 mg/kg/day (Maximum dose 16.5g/m2/day) [63]. |

Glycine in plasma and CSF | |

| Dextromethorphan (Gene – drug interactions: CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYPUGT) | Weak, non-competitive inhibitor of NMDA receptors | 3-15mg/kg/day (High individual variability) [64]. | Glycine in plasma and CSF | |

| Pyridoxal phosphate (Active form of vitamin B6) | Co-factor of glycine decarboxylase (GLDC) | Glycine in plasma and CSF | ||

|

PDE-ALDH7A1 |

Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) | Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) is a cofactor of enzymatic reactions involved in neurotransmitter synthesis |

Adults 200–500 mg/day (Maximum dose 500 mg/day) [65]. | Serum/plasma pipecolic acid levels, alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde [AASA] in serum/plasma, urine, or CSF |

| Lysine reduction therapies (LRT) – Lysine restriction, arginine supplementation | Arginine is a competitive inhibitor of lysine transport | Start at 4g/m2/day (Maximum dose 5.5g/m2/day) [65]. | Plasma lysine, arginine | |

| 3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase deficiency | L-Serine and Glycine | Seizure control, correction of behavioural abnormalities. | Infantile 3-PGDH deficiency: 500-700mg L-serine/kg/d and 200- 300mg glycine/kg/d Juvenile 3-PGDH deficiency: 100-150mg L-serine/kg/d [66] |

CSF serine and glycine; plasma serine and glycine |

| Phosphoserine aminotransferase deficiency | L-Serine and Glycine | Prevention of neurological abnormalities in presymptomatic patients | L-serine: 500mg/kg/day Glycine: 200mg/kg/day [67] |

CSF serine and glycine; plasma serine and glycine |

| 3-Phosphoserine phosphatase deficiency | L-Serine | May prevent onset of neurological symptoms | 200-300mg/kg/day [67] |

CSF and plasma serine |

| Disorder | Treatment | Rationale/mechanism | Dose | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cystinuria |

Potassium citrate | Urine alkalisation | Children: 60-80mEq/1.73 m2/d Adults: 60-80mEq/d TDS/QDS [74] |

Urine pH |

| Penicillamine | Increases cystine solubility | Children: 20-30mg/kg/d (max 4000 mg/d) Adults: 1-4 g/d TDS/QDS |

Urine cystine excretion | |

| Tiopronin | Increases cystine solubility | Children: 15-40mg/kg/d (max 1500mg/d) Adults: 800-1500mg/kg/d TDS |

Urine cystine excretion | |

| Alpha-lipoic acid | Increases cystine solubility | Children: 30mg/kg/d (max 1200mg/d) Adults: 1200mg/d BD |

Urine cystine excretion | |

| Captopril | Increases cystine solubility | Children: 1.5-6mg/kg/d (max 150mg/d) Adults: 75-150mg/d TDS |

Urine cystine excretion | |

| Lysinuric protein intolerance | Acute Management | Reduction of protein and caloric supplementation for preventing protein catabolism | Glucose infusion: 10% glucose (in cases of hyperglycemia, consider adding insulin) L-arginine: 100-250mg/kg/d IV Sodium phenylbutyrate: 450-600mg/kg/d in patients <20kg, 9.9– 13.0 g/m2/d in larger patients) Sodium benzoate: 100–250 mg/kg/d PO or IV +/- continuous haemodialysis +/- antibiotics (e.g., neomycin), lactulose, and/or lactobacillus preparation |

Blood ammonia, amino acids in blood/urine, blood glucose |

| Dietary: Protein restriction, vitamin D, iron, zinc, and calcium supplementation, +/- medical foods e.g., protein-free drinks | To prevent hyperammonemia. Zinc, iron, calcium and vitamin D levels tend to be decreased. |

Children: 0.8 −1.5g/kg/d protein intake Adults: 0.5–0.8g/kg/d protein intake [75] |

Amino acid (e.g., lysine, arginine, ornithine, glutamine) analysis in blood/urine. 25(OH)D, iron, zinc, calcium levels. |

|

| L-citrulline | Reduces blood ammonia level, increases in dietary intake, reduction of hepatomegaly |

100mg/kg/d | Blood ammonia level, amino acids | |

| L-arginine | Reduces blood ammonia level |

120–380 mg/kg/d | Blood ammonia level, amino acids | |

| L-carnitine | Secondary carnitine deficiency | 20-50mg/kg/d | Blood carnitine level, amino acids | |

| L-lysine | Increases blood lysine levels | 20-50mg/kg/d | Blood lysine level, amino acids | |

| Nitrogen scavengers | Decreases blood ammonia levels |

Sodium phenylbutyrate: 450– 600mg/kg/d in patients weighing <20kg and 9.9–13.0 g/m2/d in larger patients. Sodium benzoate: 100–250 mg/kg/d |

Blood ammonia levels, plasma amino acids, electrolytes (Sodium) |

|

| Other treatments | Management of osteoporosis, short stature, hyperlipidemia, nephritis, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, ESRF |

Vitamin D and bisphosphonate, GH injection, statins, ACE inhibitors, corticosteroids, whole lung lavage, GM-CSF, renal transplantation |

As per clinical finding | |

| Hartnup disease* | Nicotinamide | Management of dermatological and neurological complications. | 50-300mg PO [76] |

Niacin levels |

| High protein diet | To ameliorate amino acid loss | Individualised to patient | Plasma amino acids (e.g., alanine, serine, glutamine). |

| Disorder | Treatment | Rationale/mechanism | Dose | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Δ1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase deficiency |

Arginine | Increases arginine availability to brain. Improvement of neurodevelopmental and metabolic parameters. |

150mg/kg/d [105] |

Amino acid analysis (proline, ornithine, arginine, citrulline), and ammonia levels. |

|

Hyperprolinemia Type I |

Anti-epileptic medication and schizophrenia medication if required. | |||

| Avoid protein excess | Reduce accumulation of proline or P5C | Plasma amino acids (proline) | ||

|

Hyperprolinemia Type II |

B6 supplementation | Avoid deficiency | E.g., 50-100mg/day [106] | B6 levels |

| Avoid protein excess | Reduce accumulation of proline or P5C | Plasma amino acids, urine organic acids | ||

| Anti-epileptic medication and schizophrenia medication if required. | ||||

| Ornithine δ-aminotransferase deficiency (gyrate atrophy) | Arginine-restricted diet with synthetic amino acid supplementation. | Aim to decrease plasma ornithine levels and slow disease progression. | 10-35g/d protein intake [107] | Ornithine and arginine levels |

| Trial of B6, lysine, and creatine supplementation. | B6 – Aims to stimulate residual enzyme activity. Lysine – May increase kidney excretion of ornithine and arginine. Creatine and precursors – To treat secondary creatine deficiency | B6: 100-1000mg/d [107] | B6 and plasma amino acids; blood/urine creatine | |

|

Hyperornithinemia-hyperammonemia- homocitrullinuria |

Acute management | Stop protein intake for 24h and commence IV 10% Glucose (plus electrolytes). Arginine +/- citrulline supplementation. Ammonia scavengers (sodium benzoate and sodium phenylbutyrate). +/- haemodialysis (if neurological status is deteriorating) |

Glucose dose at appropriate dose to prevent catabolism. Sodium benzoate: 250mg/kg bolus (90–120 min), then maintenance 250-500mg/kg/d (>20 kg, 5.5 g/m2/d) Sodium phenylbutyrate: 250mg/kg bolus (90-120 minutes), then 250-500 mg/kg/d as maintenance [108]. |

Blood ammonia levels, blood glucose. |

| Long-term management | Protein-restricted diet with citrulline or arginine (+/- sodium benzoate or sodium phenylbutyrate) | Protein restriction individualised to patient. Sodium benzoate: ≤ 250mg/kg/d Sodium phenylbutyrate: <20 kg ≤250mg/kg/d, >20 kg 5g/m2/d L-citrulline: 100-200mg/kg/d L-arginine: <20 kg 100-200mg/kg/d, >20 kg 2.5- 6g/m2/d [108] |

Blood ammonia levels, plasma amino acids, urinary orotic acid | |

| Creatine supplementation (if plasma creatine levels low) | To treat secondary creatine deficiency. | Dosed according to degree of creatine deficiency. | Plasma creatinine levels, blood/urine creatine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).