Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

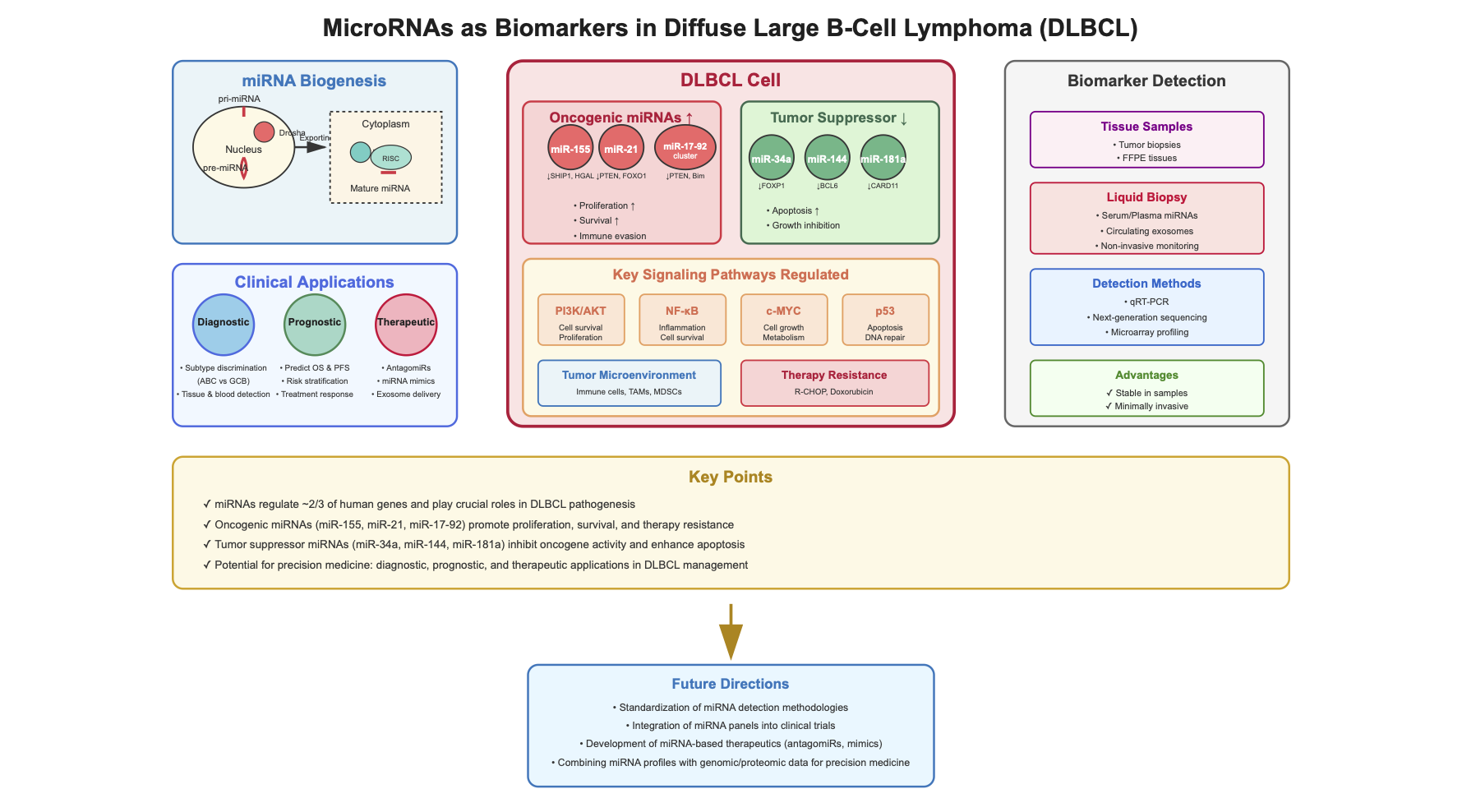

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials/Methods

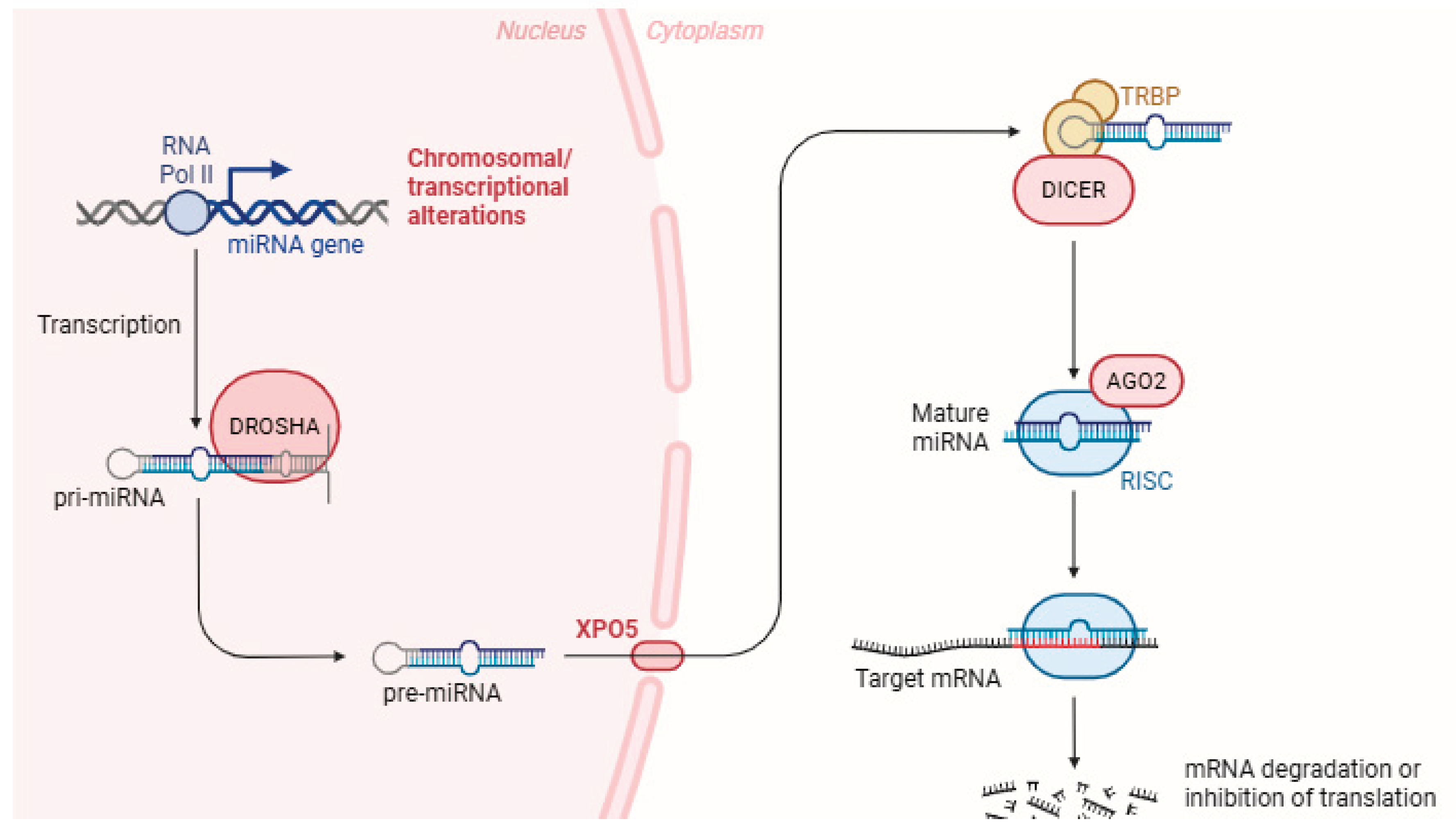

3. miRNAs Biogenesis

4. miRNAs and Their Role in DLBCL Pathogenesis and Prognosis

4.1. miR-155

4.2. miR-21

4.3. miR-34

4.4. miR-17-92

4.5. Other miRNAs of Importance in DLBCL

| miRNAs | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| miR-155-5p | Oncogenic; regulates NF-κB pathway, promotes proliferation, useful for diagnosis and classification | [56,57,58] |

| miR-21-5p | Oncogenic; regulates PI3K/AKT pathway, promotes cell survival, useful for diagnosis | [44,90,95] |

| miR-17-92 | Oncogenic; alters MYC, SHIP expression, promotes tumorigenesis | [122] |

| miR-34a | Tumor suppressor; targets SIRT1, inhibits tumor growth | [51] |

| miR-144 | Tumor suppressor; targets BCL6, inhibits tumor growth | [51] |

| miR-181a | Tumor suppressor; targets CARD11, inhibits tumor growth | [51] |

| miR-124-3p | Tumor suppressor; inhibits NFATc1/cMYC pathway, suppresses proliferation, promotes apoptosis | [91,124] |

| miR-142-5p | Promotes immunosuppressive macrophage phenotype, associated with poor response to immunochemotherapy | [126] |

5. miRNAs and Their Role in Tumor Microenvironment in DLBCL

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teras LR, D.C., Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016, 66, 443–459. [CrossRef]

- Chapuy B, S.C., Dunford AJ, Kim J, Kamburov A, Redd RA, Lawrence MS, Roemer MGM, Li AJ, Ziepert M, Staiger AM, Wala JA, Ducar MD, Leshchiner I, Rheinbay E, Taylor-Weiner A, Coughlin CA, Hess JM, Pedamallu CS, Livitz D, Rosebrock D, Rosenberg M, Tracy AA, Horn H, van Hummelen P, Feldman AL, Link BK, Novak AJ, Cerhan JR, Habermann TM, Siebert R, Rosenwald A, Thorner AR, Meyerson ML, Golub TR, Beroukhim R, Wulf GG, Ott G, Rodig SJ, Monti S, Neuberg DS, Loeffler M, Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Getz G, Shipp MA. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat. Med. 2018, 679–690. [CrossRef]

- Feugier P, V.H.A., Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R, Fermé C, Christian B, Lepage E, Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Gaulard P, Salles G, Bosly A, Gisselbrecht C, Reyes F, Coiffier B. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23, 4117–4126. [CrossRef]

- Coiffier B, L.E., Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P, Reyes F, Lederlin P, Gisselbrecht C. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002, 346, 235–242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfreundschuh M, K.E., Trümper L, Osterborg A, Trneny M, Shepherd L, Gill DS, Walewski J, Pettengell R, Jaeger U, Zinzani PL, Shpilberg O, Kvaloy S, de Nully Brown P, Stahel R, Milpied N, López-Guillermo A, Poeschel V, Grass S, Loeffler M, Murawski N; . MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2011, 11, 1013–1022. [CrossRef]

- Coiffier B, S.C. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: R-CHOP failure-what to do? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2016, 1, 366–378. [CrossRef]

- Tilly, H.; Morschhauser, F.; Sehn, L.H.; Friedberg, J.W.; Trněný, M.; Sharman, J.P.; Herbaux, C.; Burke, J.M.; Matasar, M.; Rai, S.; et al. Polatuzumab Vedotin in Previously Untreated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 351–363. [CrossRef]

- Parry EM, R.S., Okosun J. DLBCL arising from indolent lymphomas: How are they different? . Semin Hematol. 2023, 60, 277–284. [CrossRef]

- Rosenwald A, W.G., Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, Fisher RI, Gascoyne RD, Muller-Hermelink HK, Smeland EB, Giltnane JM, Hurt EM, Zhao H, Averett L, Yang L, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES, Simon R, Klausner RD, Powell J, Duffey PL, Longo DL, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Sanger WG, Dave BJ, Lynch JC, Vose J, Armitage JO, Montserrat E, López-Guillermo A, Grogan TM, Miller TP, LeBlanc M, Ott G, Kvaloy S, Delabie J, Holte H, Krajci P, Stokke T, Staudt LM;. Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002, 346, 1937–1947. [CrossRef]

- Wright GW, H.D., Phelan JD, Coulibaly ZA, Roulland S, Young RM, Wang JQ, Schmitz R, Morin RD, Tang J, Jiang A, Bagaev A, Plotnikova O, Kotlov N, Johnson CA, Wilson WH, Scott DW, Staudt LM. A Probabilistic Classification Tool for Genetic Subtypes of Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma with Therapeutic Implications. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 551–568. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz R, W.G., Huang DW, Johnson CA, Phelan JD, Wang JQ, Roulland S, Kasbekar M, Young RM, Shaffer AL, Hodson DJ, Xiao W, Yu X, Yang Y, Zhao H, Xu W, Liu X, Zhou B, Du W, Chan WC, Jaffe ES, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Campo E, Lopez-Guillermo A, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Delabie J, Rimsza LM, Tay Kuang Wei K, Zelenetz AD, Leonard JP, Bartlett NL, Tran B, Shetty J, Zhao Y, Soppet DR, Pittaluga S, Wilson WH, Staudt LM. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 1396–1407. [CrossRef]

- Sehn LH, S.G. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 842–858. [CrossRef]

- Alaggio R, A.C., Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, Borges AM, Boyer D, Calaminici M, Chadburn A, Chan JKC, Cheuk W, Chng WJ, Choi JK, Chuang SS, Coupland SE, Czader M, Dave SS, de Jong D, Du MQ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Ferry J, Geyer J, Gratzinger D, Guitart J, Gujral S, Harris M, Harrison CJ, Hartmann S, Hochhaus A, Jansen PM, Karube K, Kempf W, Khoury J, Kimura H, Klapper W, Kovach AE, Kumar S, Lazar AJ, Lazzi S, Leoncini L, Leung N, Leventaki V, Li XQ, Lim MS, Liu WP, Louissaint A Jr, Marcogliese A, Medeiros LJ, Michal M, Miranda RN, Mitteldorf C, Montes-Moreno S, Morice W, Nardi V, Naresh KN, Natkunam Y, Ng SB, Oschlies I, Ott G, Parrens M, Pulitzer M, Rajkumar SV, Rawstron AC, Rech K, Rosenwald A, Said J, Sarkozy C, Sayed S, Saygin C, Schuh A, Sewell W, Siebert R, Sohani AR, Tooze R, Traverse-Glehen A, Vega F, Vergier B, Wechalekar AD, Wood B, Xerri L, Xiao W. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [CrossRef]

- Campo E, J.E., Cook JR, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Swerdlow SH, Anderson KC, Brousset P, Cerroni L, de Leval L, Dirnhofer S, Dogan A, Feldman AL, Fend F, Friedberg JW, Gaulard P, Ghia P, Horwitz SM, King RL, Salles G, San-Miguel J, Seymour JF, Treon SP, Vose JM, Zucca E, Advani R, Ansell S, Au WY, Barrionuevo C, Bergsagel L, Chan WC, Cohen JI, d'Amore F, Davies A, Falini B, Ghobrial IM, Goodlad JR, Gribben JG, Hsi ED, Kahl BS, Kim WS, Kumar S, LaCasce AS, Laurent C, Lenz G, Leonard JP, Link MP, Lopez-Guillermo A, Mateos MV, Macintyre E, Melnick AM, Morschhauser F, Nakamura S, Narbaitz M, Pavlovsky A, Pileri SA, Piris M, Pro B, Rajkumar V, Rosen ST, Sander B, Sehn L, Shipp MA, Smith SM, Staudt LM, Thieblemont C, Tousseyn T, Wilson WH, Yoshino T, Zinzani PL, Dreyling M, Scott DW, Winter JN, Zelenetz AD. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: A report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood 2022, 140, 1229–1253. [CrossRef]

- Project., I.N.-H.s.L.P.F. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1993, 329, 987–994. [CrossRef]

- Sehn LH, B.B., Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Hoskins P, Klasa R, Savage KJ, Shenkier T, Sutherland J, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood 2007, 109, 1857–1861. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, S.L., Rademaker AW, Gordon LI, Lacasce AS, Crosby-Thompson A, Vanderplas A, Zelenetz AD, Abel GA, Rodriguez MA, Nademanee A, Kaminski MS, Czuczman MS, Millenson M, Niland J, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Friedberg JW, Winter JN. An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood 2014, 123, 837–842. [CrossRef]

- Jelicic J, J.-J.K., Bukumiric Z, Roost Clausen M, Ludvigsen Al-Mashhadi A, Pedersen RS, Poulsen CB, Brown P, El-Galaly TC, Stauffer Larsen T. Prognostic indices in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A population-based comparison and validation study of multiple models. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 157. [CrossRef]

- Ruppert AS, D.J., Salles G, Wall A, Cunningham D, Poeschel V, Haioun C, Tilly H, Ghesquieres H, Ziepert M, Flament J, Flowers C, Shi Q, Schmitz N. International prognostic indices in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A comparison of IPI, R-IPI, and NCCN-IPI. Blood 2020, 135, 2041–2048. [CrossRef]

- Mikhaeel NG, H.M., Eertink JJ, de Vet HCW, Boellaard R, Dührsen U, Ceriani L, Schmitz C, Wiegers SE, Hüttmann A, Lugtenburg PJ, Zucca E, Zwezerijnen GJC, Hoekstra OS, Zijlstra JM, Barrington SF. Proposed New Dynamic Prognostic Index for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: International Metabolic Prognostic Index. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 2352–2360. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, P.K. Clinical Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Precision Oncology. Cancer Res Treat 2023, 55, 351–366. [CrossRef]

- Wu FT, L.L., Xu W, Li JY. Circulating tumor DNA: Clinical roles in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. 9. Ann Hematol. 2019, 98, 255–269. [CrossRef]

- Arzuaga-Mendez J, P.-F.E., Lopez-Lopez E, Martin-Guerrero I, García-Ruiz JC, García-Orad A. Cell-free DNA as a biomarker in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019, 139, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Tavakkoli M, B.S. 2024 Update: Advances in the risk stratification and management of large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2023, 98, 1791–1805. [CrossRef]

- DP., B. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [CrossRef]

- DP., B. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [CrossRef]

- H., L. MicroRNAs won the Nobel - will they ever be useful as medicines? . Nature 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wightman B, H.I., Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993, 75, 855–862. [CrossRef]

- Lee RC, F.R., Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.C.F., K.K.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 92–105. [CrossRef]

- Chen CZ, L.H. MicroRNAs as regulators of mammalian hematopoiesis. Semin Immunol. 2005, 17, 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Saliminejad K, K.K.H., Soleymani Fard S, Ghaffari SH. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul P, C.A., Sarkar D, Langthasa M, Rahman M, Bari M, Singha RS, Malakar AK, Chakraborty S. Interplay between miRNAs and human diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 2007–2018. [CrossRef]

- Markopoulos GS, R.E., Tokamani M, Chavdoula E, Hatziapostolou M, Polytarchou C, Marcu KB, Papavassiliou AG, Sandaltzopoulos R, Kolettas E. A step-by-step microRNA guide to cancer development and metastasis. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2017, 40, 303–339. [CrossRef]

- Due H, S.P., Bødker JS, Schmitz A, Bøgsted M, Johnsen HE, El-Galaly TC, Roug AS, Dybkær K. miR-155 as a Biomarker in B-Cell Malignancies. Biomed Res Int. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Koumpis E, G.V., Papathanasiou K, Papoudou-Bai A, Kanavaros P, Kolettas E, Hatzimichael E. The Role of microRNA-155 as a Biomarker in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2658. [CrossRef]

- Ha M, K.V. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [CrossRef]

- de Rie D, A.I., Alam T, Arner E, Arner P, Ashoor H; et al. An integrated expression atlas of miRNAs and their promoters in human and mouse. Nat Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 872–878. [CrossRef]

- W., H. MicroRNAs: Biomarkers, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Methods Mol Biol. 1617, 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Denli AM, T.B., Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 2005, 432, 231–235. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon CR, L.H., Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6- methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature 2015, 519, 482–485. [CrossRef]

- Han J, L.Y., Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev 2004, 18, 3016–3027. [CrossRef]

- Okada C, Y.E., Lee SJ, Shibata S, Katahira J, Nakagawa A; et al. A high-resolution structure of the pre-microRNA nuclear export machinery. Science 2009, 326, 1275–1279. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, K.F., Jaskiewicz L, Westhof E, Filipowicz W. Single processing center models for human Dicer and bacterial RNase III. Cell 2004, 118, 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Yoda M, K.T., Paroo Z, Ye X, Iwasaki S, Liu Q; et al. ATP-dependent human RISC assembly pathways. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010, 17, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Chendrimada TP, G.R., Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 2005, 436, 740–744. [CrossRef]

- Westholm JO, L.E.M.m.b.v.s.B.N.-d.j.b.E.J. Mirtrons: microRNA biogenesis via splicing. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1897–1904. [CrossRef]

- Telonis AG, M.R., Loher P, Chervoneva I, Londin E, Rigoutsos I. Knowledge about the presence or absence of miRNA isoforms (isomiRs) can successfully discriminate amongst 32 TCGA cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 2973–2985. [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, A. Circulating microRNAs as Potential Biomarkers in Pancreatic Cancer—Advances and Challenges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023, 24, 13340. [CrossRef]

- Gartenhaus, K.M.-M.a.R.B. Role of microRNA deregulation in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Leuk Res. 2013, 37. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Alsaadi, M.Y.K., Mahmood Hassan Dalhat, Salem Bahashwan,; Muhammad Uzair Khan, A.A., Hussein Almehdar and Ishtiaq Qadri Dysregulation of miRNAs in DLBCL: Causative Factor for Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Prognosis. Diagnostics 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Faraoni I, A.F., Cardone J, Bonmassar E. miR-155 gene: A typical multifunctional microRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1792, 497–505. [CrossRef]

- Bondada MS, Y.Y., Nair V. Multifunctional miR-155 Pathway in Avian Oncogenic Virus-Induced Neoplastic Diseases. Non-Coding RNA 2019, 5, 24. [CrossRef]

- Thai TH, C.D., Casola S, Ansel KM, Xiao C, Xue Y, Murphy A, Frendewey D, Valenzuela D, Kutok JL, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky N, Yancopoulos G, Rao A, Rajewsky K. Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155. Science 2007, 316, 604–608. [CrossRef]

- Mattiske S, S.R., Neilsen PM, Callen DF. The oncogenic role of miR-155 in breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 1236–1243. [CrossRef]

- Costinean S, S.S., Pedersen IM, Tili E, Trotta R, Perrotti D, Ciarlariello D, Neviani P, Harb J, Kauffman LR, Shidham A, Croce CM. Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta are targeted by miR-155 in B cells of Emicro-MiR-155 transgenic mice. Blood 2009, 114, 1374–1382. [CrossRef]

- O'Connell RM, C.A., Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc NatI Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106, 7113–7118. [CrossRef]

- Lunning M, V.J., Nastoupil L, Fowler N, Burger JA, Wierda WG, Schreeder MT, Siddiqi T, Flowers CR, Cohen JB, Sportelli P, Miskin HP, Weiss MS, O'Brien S. Ublituximab and umbralisib in relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2019, 134, 1811–1820. [CrossRef]

- Lossos IS, A.A., Rajapaksa R, Tibshirani R, Levy R. HGAL is a novel interleukin-4-inducible gene that strongly predicts survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2003, 101, 433–440. [CrossRef]

- Dagan LN, J.X., Bhatt S, Cubedo E, Rajewsky K, Lossos IS. miR-155 regulates HGAL expression and increases lymphoma cell motility. Blood 2012, 119, 513–520. [CrossRef]

- Kalkusova K, T.P., Stakheev D, Smrz D. The Role of miR-155 in Antitumor Immunity. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5414. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.M.R., J.L.; O’Connell, R.M. No small matter: Emerging roles for exosomal miRNAs in the immune system. Febs J. 2022, 289, 4021–4037. [CrossRef]

- Alexander M, H.R., Runtsch MC, Kagele DA, Mosbruger TL, Tolmachova T, Seabra MC, Round JL, Ward DM, O'Connell RM. Exosome-delivered microRNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat Commun 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Hiramoto JS, T.K., Bedolli M, Norton JA, Hirose R. Antitumor immunity induced by dendritic cell-based vaccination is dependent on interferon-gamma and interleukin-12. J Surg Res. 2004, 116, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Asadirad A, B.K., Hashemi SM; et al. Dendritic cell immunotherapy with miR-155 enriched tumor-derived exosome suppressed cancer growth and induced antitumor immune responses in murine model of colorectal cancer induced by CT26 cell line. International Immunopharmacology 2022, 104, 108493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D., Wang, X., Song, Y. et al. Exosomal miR-146a-5p and miR-155-5p promote CXCL12/CXCR7-induced metastasis of colorectal cancer by crosstalk with cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Decruyenaere P, O.F., Vandesompele J. Circulating RNA biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A systematic review. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021, 10, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Santillan M, L.-E.A., Arzuaga-Mendez J, Lopez-Lopez E, Garcia-Orad A. Circulating miRNAs as biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A systematic review. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 22850–22861. [CrossRef]

- Huskova H, K.K., Karban J, Vargova J, Vargova K, Dusilkova N, Trneny M, Stopka T. Oncogenic microRNA-155 and its target PU.1: An integrative gene expression study in six of the most prevalent lymphomas. Int J Hematol. 2015, 102, 441–450. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong H, X.L., Zhong JH, Xiao F, Liu Q, Huang HH, Chen FY. Clinical and prognostic significance of miR-155 and miR-146a expression levels in formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded tissue of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Ther Med. 2012, 3, 763–770. [CrossRef]

- Lawrie CH, G.S., Dunlop HM, Pushkaran B, Liggins AP, Pulford K, Banham AH, Pezzella F, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS, Hatton CS, Harris AL. Detection of elevated levels of tumour-associated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008, 141, 672–675. [CrossRef]

- Fang C, Z.D., Dong HJ, Zhou ZJ, Wang YH, Liu L, Fan L, Miao KR, Liu P, Xu W, Li JY. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2012, 91, 553–559. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.X.G., Y.X.; Na, W.N.; Chao, J.; Yang, X. Circulating microRNA-125b and microRNA-130a expression profiles predict chemoresistance to R-CHOP in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Oncol. Lett 2016, 11, 423–432. [CrossRef]

- Inada, K.O., Y.; Cho, Y.; Saito, H.; Iijima, T.; Hori, M.; Kojima, H. Availability of Circulating MicroRNAs as a Biomarker for Early Diagnosis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Open J. Blood Dis. 2015, 48–58.

- Zheng Z, S.R., Zhao HJ, Fu D, Zhong HJ, Weng XQ, Qu B, Zhao Y, Wang L, Zhao WL. MiR155 sensitized B-lymphoma cells to anti-PD-L1 antibody via PD-1/PD-L1-mediated lymphoma cell interaction with CD8+T cells. Mol Cancer. 2019, 18, 54. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.X.G., Y.X.; Na, W.N.; Chao, J.; Yang, X. Circulating microRNA-125b and microRNA-130a expression profiles predict chemoresistance to R-CHOP in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Oncol. Lett 2016, 11, 423–432. [CrossRef]

- Beheshti A, S.K., Vanderburg C, Ravi D, McDonald JT, Christie AL, Shigemori K, Jester H, Weinstock DM, Evens AM. Identification of Circulating Serum Multi-MicroRNA Signatures in Human DLBCL Models. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 17261. [CrossRef]

- Caramuta S, L.L., Ozata DM, Akçakaya P, Georgii-Hemming P, Xie H, Amini RM, Lawrie CH, Enblad G, Larsson C, Berglund M, Lui WO. Role of microRNAs and microRNA machinery in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2013, 3, 152. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal J, S.Y., Huang X, Liu Y, Wake L, Liu C, Deffenbacher K, Lachel CM, Wang C, Rohr J, Guo S, Smith LM, Wright G, Bhagavathi S, Dybkaer K, Fu K, Greiner TC, Vose JM, Jaffe E, Rimsza L, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Delabie J, Campo E, Braziel RM, Cook JR, Tubbs RR, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD, Staudt LM, Gascoyne RD, McKeithan TW, Chan WC. Global microRNA expression profiling uncovers molecular markers for classification and prognosis in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2015, 125, 1137–1145. [CrossRef]

- Zhu FQ, Z.L., Tang N, Tang YP, Zhou BP, Li FF, Wu WG, Zeng XB, Peng SS. MicroRNA-155 Downregulation Promotes Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Oncol Res. 2016, 24, 415–427. [CrossRef]

- Due H, S.P., Bødker JS, Schmitz A, Bøgsted M, Johnsen HE, El-Galaly TC, Roug AS, Dybkær K. miR-155 as a Biomarker in B-Cell Malignancies. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:9513037. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmadvand M, E.M., Pashaiefar H, Yaghmaie M, Manoochehrabadi S, Khakpour G, Sheikhsaran F, Montazer Zohour M. Over expression of circulating miR-155 predicts prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk. Res 2018, 70, 45–48. [CrossRef]

- Koumpis, E.; Georgoulis, V.; Papathanasiou, K.; Papoudou-Bai, A.; Kanavaros, P.; Kolettas, E.; Hatzimichael, E. The Role of microRNA-155 as a Biomarker in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vigorito E, P.K., Abreu-Goodger C, Bunting S, Xiang Z, Kohlhaas S, Das PP, Miska EA, Rodriguez A, Bradley A, Smith KG, Rada C, Enright AJ, Toellner KM, Maclennan IC, Turner M. microRNA-155 regulates the generation of immunoglobulin class-switched plasma cells. Immunity 2007, 27, 847–859. [CrossRef]

- Chan JA, K.A., Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6029–6033. [CrossRef]

- Xu LF, W.Z., Chen Y, Zhu QS, Hamidi S, Navab R. MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) regulates cellular proliferation, invasion, migration, and apoptosis by targeting PTEN, RECK and Bcl-2 in lung squamous carcinoma, Gejiu City, China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 103698. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Z.C., Wang T, You H, Yao R. Curcumin Inhibits the Proliferation, Migration, Invasion, and Apoptosis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Cell Line by Regulating MiR-21/VHL Axis. Yonsei Med J. 2020, 61, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, W.H., Chen H, Liu S, Lu H, Kong D, Huang X, Kong Q, Lu Z. Clinical significance and detection of microRNA-21 in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Chinese population. Eur J Haematol 2014, 92, 407–412. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, L.C. MicroRNA and cancer--focus on apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009, 13, 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Ho KK, M.S., Lam EW. Many forks in the path: Cycling with FoxO. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2300–2311. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, G.L., Pan H, Kan D, Majeski M, Adam SA, Unterman TG. Biochem J. Multiple elements regulate nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of FOXO1: Characterization of phosphorylation- and 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. 2004, 378, 839–849. [CrossRef]

- Go H, J.J., Kim PJ, Kim YG, Nam SJ, Paik JH, Kim TM, Heo DS, Kim CW, Jeon YK. MicroRNA-21 plays an oncogenic role by targeting FOXO1 and activating the PI3K/AKT pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2015, 6, 15035–15049. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, S.X., Zou Q, Wang SP, Tang SM, Zhang GZ. Biological functions of microRNAs: A review. J Physiol Biochem 2011, 67, 129–139. [CrossRef]

- Calin GA, C.C. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 2006, 6, 857–866. [CrossRef]

- Wang WY, Z.H., Wang L, Ma YP, Gao F, Zhang SJ, Wang LC. miR-21 expression predicts prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014, 38, 715–719. [CrossRef]

- Baraniskin A, K.J., Schlegel U, Chan A, Deckert M, Gold R, Maghnouj A, Zöllner H, Reinacher-Schick A, Schmiegel W, Hahn SA, Schroers R. Identification of microRNAs in the cerebrospinal fluid as marker for primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system. Blood 2011, 117, 3140–3146. [CrossRef]

- Mao X, S.Y., Tang J. Serum miR-21 is a diagnostic and prognostic marker of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neuro Sci. 2014, 35, 233–238. [CrossRef]

- Narducci MG, A.D., Picchio MC, Lazzeri C,; Pagani E, S.F., Scala E, Fadda P, Cristofoletti C, Facchiano A, Frontani M, Monopoli; A, F.M., Negrini M, Lombardo GA, Caprini; G., E.a.R. MicroRNA profiling reveals that miR-21, miR486 and miR-214 are upregulated and involved in cell survival in Sezary syndrome. Cell Death Dis 2011, 2, e151. [CrossRef]

- Hermeking, H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2010, 17, 193–199. [CrossRef]

- Chim, C.S.; Wong, K.Y.; Qi, Y.; Loong, F.; Lam, W.L.; Wong, L.G.; Jin, D.Y.; Costello, J.F.; Liang, R. Epigenetic inactivation of the miR-34a in hematological malignancies. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 745–750. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Lin, L. mRNA expression profile analysis reveals a C-MYC/miR-34a pathway involved in the apoptosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells induced by Yiqichutan treatment. Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 2157–2165. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Imani, S.; Wu, M.Y.; Wu, R.C. MicroRNA-34 Family in Cancers: Role, Mechanism, and Therapeutic Potential. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Balatti, V.; Tomasello, L.; Rassenti, L.Z.; Veneziano, D.; Nigita, G.; Wang, H.Y.; Thorson, J.A.; Kipps, T.J.; Pekarsky, Y.; Croce, C.M. miR-125a and miR-34a expression predicts Richter syndrome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Blood 2018, 132, 2179–2182. [CrossRef]

- Asmar, F.; Hother, C.; Kulosman, G.; Treppendahl, M.B.; Nielsen, H.M.; Ralfkiaer, U.; Pedersen, A.; Møller, M.B.; Ralfkiaer, E.; de Nully Brown, P.; et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with combined TP53 mutation and MIR34A methylation: Another "double hit" lymphoma with very poor outcome? Oncotarget 2014, 5, 1912–1925. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Gao, L.; Zhang, S.; Tao, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhu, M. Prognostic significance of miR-34a and its target proteins of FOXP1, p53, and BCL2 in gastric MALT lymphoma and DLBCL. Gastric Cancer 2014, 17, 431–441. [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.C.; Ranjbar, B.; Laursen, M.B.; Falgreen, S.; Bilgrau, A.E.; Bødker, J.S.; Jørgensen, L.K.; Primo, M.N.; Schmitz, A.; Ettrup, M.S.; et al. High miR-34a expression improves response to doxorubicin in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol 2016, 44, 238–246.e232. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Srinivasan, L.; Calado, D.P.; Patterson, H.C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Henderson, J.M.; Kutok, J.L.; Rajewsky, K. Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 2008, 9, 405–414. [CrossRef]

- Mogilyansky, E.; Rigoutsos, I. The miR-17/92 cluster: A comprehensive update on its genomics, genetics, functions and increasingly important and numerous roles in health and disease. Cell Death Differ 2013, 20, 1603–1614. [CrossRef]

- Dal Bo, M.; Bomben, R.; Hernández, L.; Gattei, V. The MYC/miR-17-92 axis in lymphoproliferative disorders: A common pathway with therapeutic potential. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19381–19392. [CrossRef]

- Ota, A.; Tagawa, H.; Karnan, S.; Tsuzuki, S.; Karpas, A.; Kira, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Seto, M. Identification and characterization of a novel gene, C13orf25, as a target for 13q31-q32 amplification in malignant lymphoma. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 3087–3095. [CrossRef]

- Fassina, A.; Marino, F.; Siri, M.; Zambello, R.; Ventura, L.; Fassan, M.; Simonato, F.; Cappellesso, R. The miR-17-92 microRNA cluster: A novel diagnostic tool in large B-cell malignancies. Lab Invest 2012, 92, 1574–1582. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, A.J.; Malumbres, R.; Kozloski, G.A.; Advani, R.; Talreja, N.; Chinichian, S.; Briones, J.; Natkunam, Y.; Sehn, L.H.; Gascoyne, R.D.; et al. MicroRNAs are independent predictors of outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP. Clin Cancer Res 2011, 17, 4125–4135. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Jia, C.; Quan, L.; Zhao, L.; Tian, Y.; Liu, A. Significance of the microRNA-17-92 gene cluster expressed in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 2459–2467. [CrossRef]

- Kwanhian, W., Lenze, D., Alles, J., Motsch, N., Barth, S., Döll, C., Imig, J., Hummel, M., Tinguely, M., Trivedi, P., Lulitanond, V., Meister, G., Renner, C., & Grässer, F. MicroRNA-142 is mutated in about 20% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Medicine 2012, 1, 141–155. [CrossRef]

- Menegatti, J., Nakel, J., Stepanov, Y., Caban, K., Ludwig, N., Nord, R., Pfitzner, T., Yazdani, M., Vilimova, M., Kehl, T., Lenhof, H., Philipp, S., Meese, E., Fröhlich, T., Grässer, F., & Hart, M. Changes of Protein Expression after CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout of miRNA-142 in Cell Lines Derived from Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Larrabeiti-Etxebarria, A., Lopez-Santillan, M., Santos-Zorrozua, B., Lopez-Lopez, E., & García-Orad, A. Systematic Review of the Potential of MicroRNAs in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, F., Marchesi, F., Palombi, F., Pelosi, A., Di Pace, A., Sacconi, A., Terrenato, I., Annibali, O., Tomarchio, V., Marino, M., Cantonetti, M., Vaccarini, S., Papa, E., Moretta, L., Bertoni, F., Mengarelli, A., Regazzo, G., & Rizzo, M. (2021). MiR-22, a serum predictor of poor outcome and therapy response in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. British Journal of Haematology, 195. MiR-22, a serum predictor of poor outcome and therapy response in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. British Journal of Haematology 2021, 195. [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, F., Regazzo, G., Palombi, F., Terrenato, I., Sacconi, A., Spagnuolo, M., Donzelli, S., Marino, M., Ercolani, C., Di Benedetto, A., Blandino, G., Ciliberto, G., Mengarelli, A., & Rizzo, M. Serum miR-22 as potential non-invasive predictor of poor clinical outcome in newly diagnosed, uniformly treated patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: An explorative pilot study. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 37. [CrossRef]

- Kozloski, G., Jiang, X., Bhatt, S., Ruiz, J., Vega, F., Shaknovich, R., Melnick, A., & Lossos, I. miR-181a negatively regulates NF-κB signaling and affects activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma pathogenesis. Blood 2016, 127, 2856–2866. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D., Fang, C., He, W., Wu, C., Li, X., & Wu, J. (2019). MicroRNA-181a Inhibits Activated B-Cell-Like Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Progression by Repressing CARD11. Journal of Oncology 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kozloski, G., Jiang, X., Bunting, K., Melnick, A., & Lossos, I. MiR-181a Is a Master Regulator of the Nuclear Factor-κB Signaling Pathway in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2012, 120, 417. [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, M., Khan, M., Dalhat, M., Bahashwan, S., Khan, M., Albar, A., Almehdar, H., & Qadri, I. Dysregulation of miRNAs in DLBCL: Causative Factor for Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Prognosis. Diagnostics 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Wang, A., Hu, Z., Xu, X., Liu, Z., & Wang, Z. (2016). A Critical Role of miR-144 in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma Proliferation and Invasion. Cancer Immunology Research 2016, 4, 337–344. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Xu, M., Hu, X., Ding, X., Zhang, X., Xu, L., Li, L., Sun, X., & Song, J. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem overexpressing microRNA-124-3p inhibit DLBCL progression by downregulating the NFATc1/cMYC pathway. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Xu, L., Sun, X., Zhao, X., Gao, B., Cheng, Y., Liu, D., Zhao, J., Zhang, X., Xu, L., & Song, J. Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Secreted Exosomes Overexpressing Microrna-124-3p Inhibit DLBCL Progression By Downregulating NFATc1. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Longley, J., Foxall, R., Thirdborough, S., Beers, S., & Cragg, M. MicroRNA manipulation of macrophage polarization in DLBCL to augment antibody immunotherapy. Cancer Reasearch 2024. [CrossRef]

- Koumpis, E.; Papoudou-Bai, A.; Papathanasiou, K.; Kolettas, E.; Kanavaros, P.; Hatzimichael, E. Unraveling the Immune Microenvironment in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Prognostic and Potential Therapeutic Implications. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 7048–7064. [CrossRef]

- Veglia F, S.E., Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [CrossRef]

- Ai L, M.S., Wang Y, Wang H, Cai L, Li W, Hu Y. Prognostic role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prognostic role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1220. [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, E., Białopiotrowicz, E., Szydłowski, M., Prochorec-Sobieszek, M., Juszczyński, P., & Szumera-Ciećkiewicz, A. DEPTOR is a microRNA-155 target regulating migration and cytokine production in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells. Experimental Hematology 2020. [CrossRef]

- CH., L. MicroRNAs and lymphomagenesis: A functional review. Br J Haematol. 2013, 160, 571–581. [CrossRef]

- Medina PP, N.M., Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature 2010, 467, 86–90. [CrossRef]

- Li J, F.R., Yang L, Tu W. miR-21 expression predicts prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. 2015;8(11):15019–24. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015, 8, 15019–15024.

- An G, A.C., Feng X, Wen K, Zhong M, Zhang L, Munshi NC, Qiu L, Tai YT, Anderson KC. Osteoclasts promote immune suppressive microenvironment in multiple myeloma: Therapeutic implication. Blood 2016, 128, 1590–1603. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, L.C., Ju S, Wang Y, Wang H, Zhong R. Myeloma cell adhesion to bone marrow stromal cells confers drug resistance by microRNA-21 up-regulation. Leuk Lymphoma 2011, 52, 1991–1998. [CrossRef]

- De Mattos-Arruda L, B.G., Nuciforo PG, Di Tommaso L, Giovannetti E, Peg V, Losurdo A, Pérez-Garcia J, Masci G, Corsi F, Cortés J, Seoane J, Calin GA, Santarpia L. MicroRNA-21 links epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and inflammatory signals to confer resistance to neoadjuvant trastuzumab and chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 37269–37280. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R., Zheng, Z., Wang, L., Cheng, S., Shi, Q., Qu, B., Fu, D., Leboeuf, C., Zhao, Y., Ye, J., Janin, A., & Zhao, W. A novel prognostic model based on four circulating miRNA in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Implications for the roles of MDSC and Th17 cells in lymphoma progression. Molecular Oncology 2020, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Z, X.P., Wang L, Zhao HJ, Weng XQ, Zhong HJ, Qu B, Xiong J, Zhao Y, Wang XF, Janin A, Zhao WL. MiR21 sensitized B-lymphoma cells to ABT-199 via ICOS/ICOSL-mediated interaction of Treg cells with endothelial cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 82. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).