Submitted:

08 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Rheumatoid Arthritis Background and Review Rationale

1.2. Aims

2.3. Objectives

2.4. Hypothesis

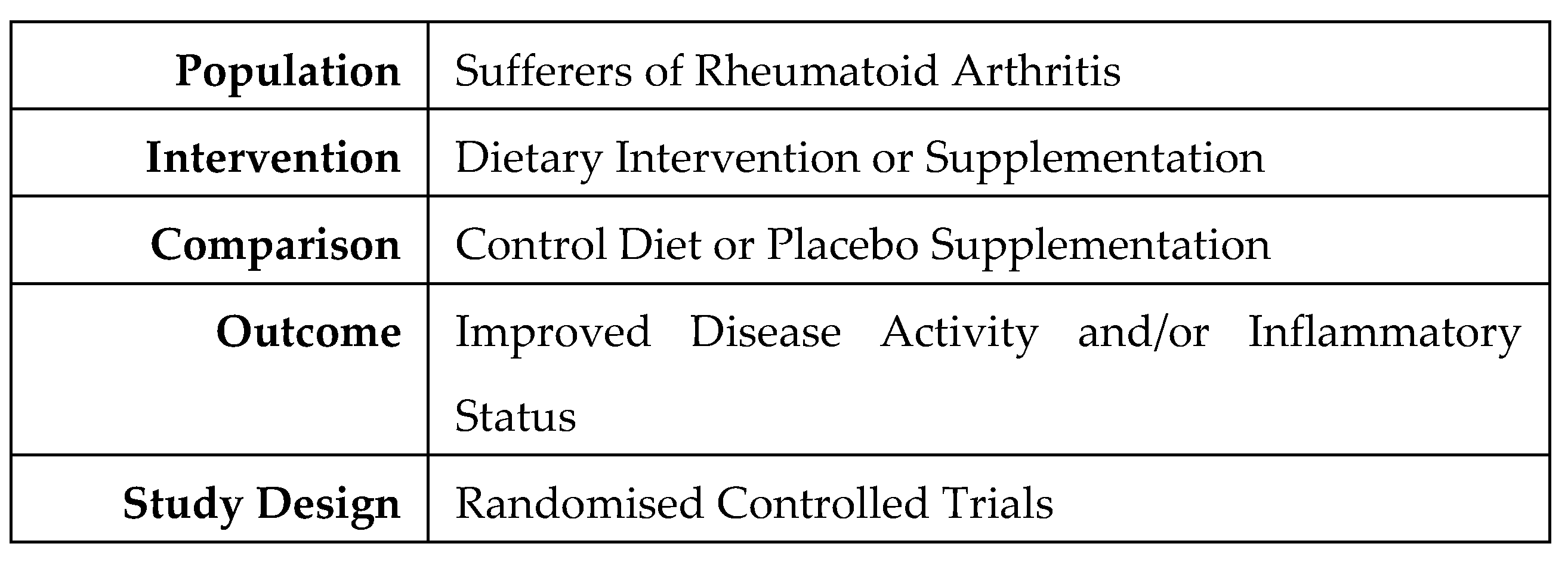

3. Methods

3.1. Protocol

3.2. Outcomes

3.4. Inclusion Criteria

3.5. Exclusion Criteria

3.6. Literature Search Strategy

3.7. Study Selection and Data Extraction

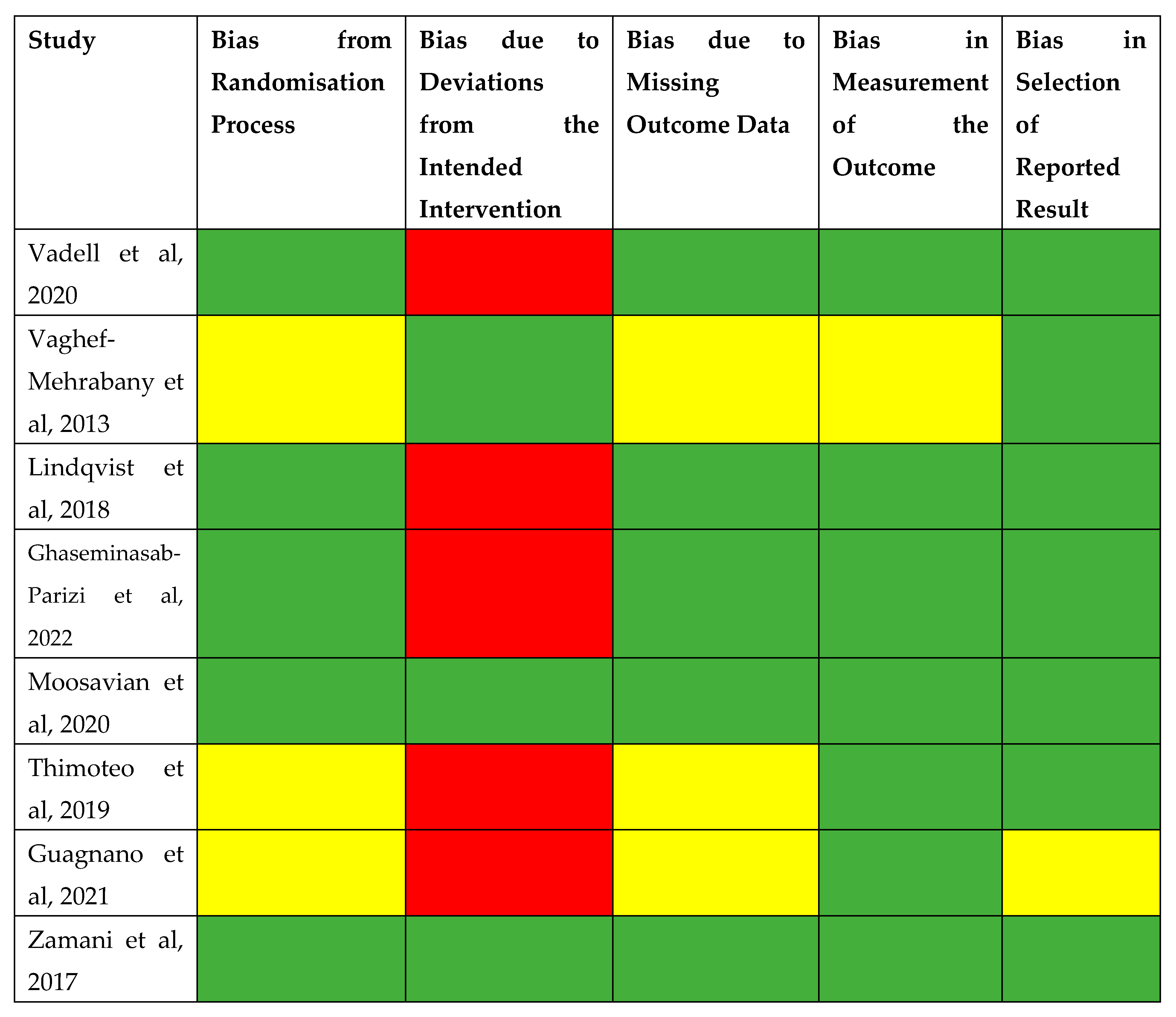

3.8. Risk of Bias Assessment

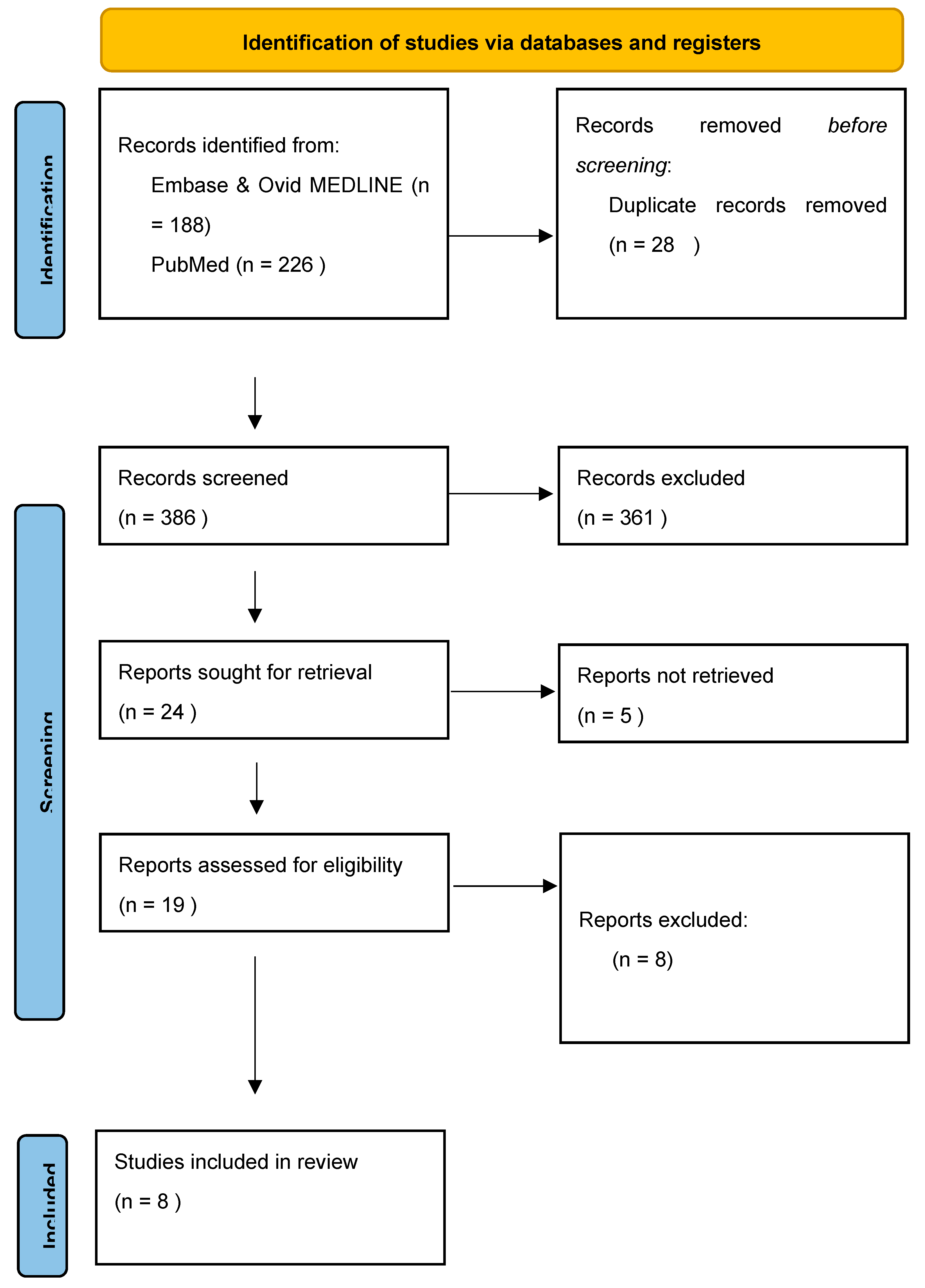

4.1. Study Selection

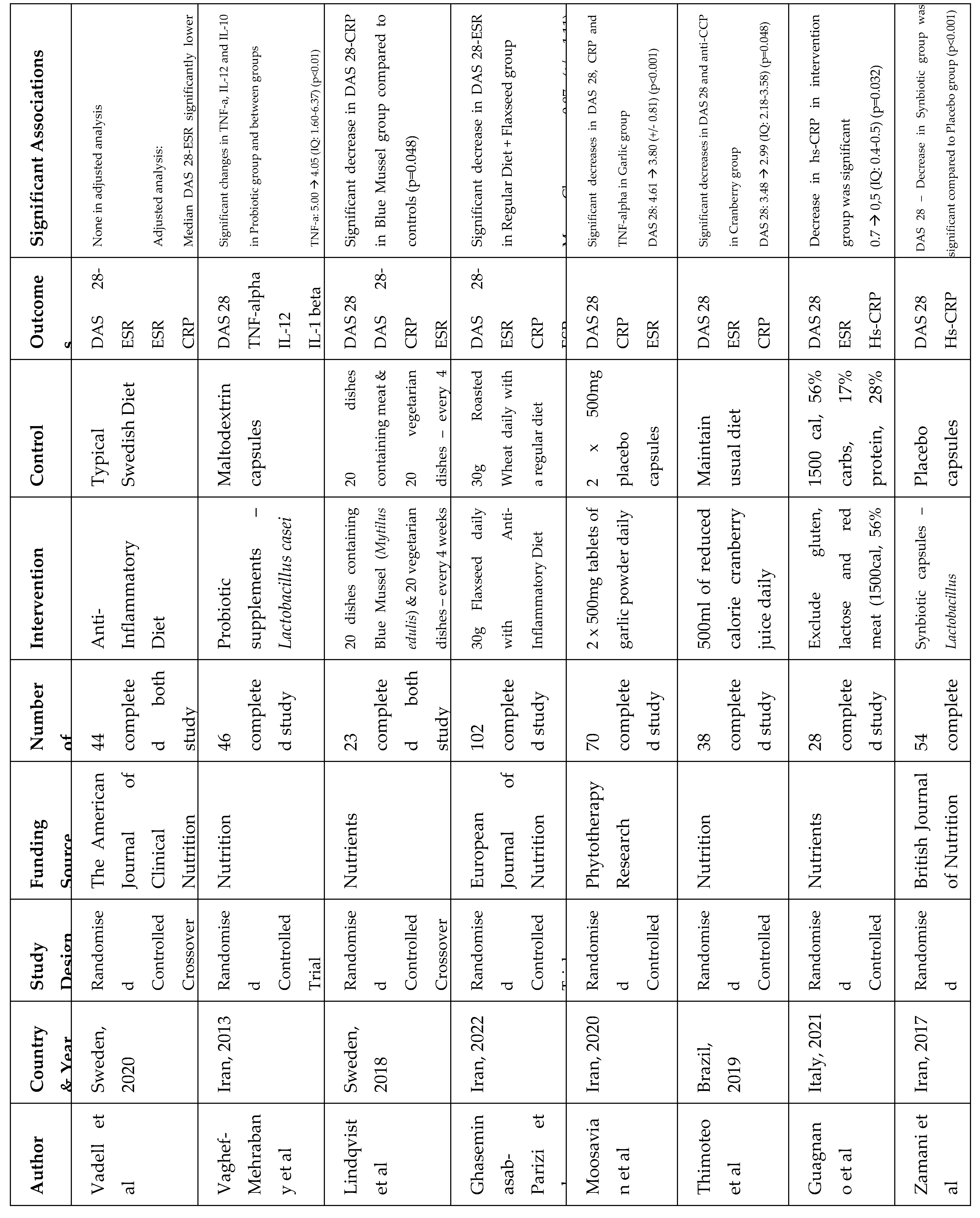

4.2. Study Characteristics

4.3. Dietary Patterns and Nutrients

4.4. Safety and Adverse Events

4.5. Risk of Bias

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

5.3. Relevance to Clinical Practice and Future Research

Appendix

Appendix 1 – Part A: Data Extraction Template

| Study Information | Title |

| Authors | |

| Year & Country | |

| Journal | |

| Study Design | |

| Study Objective | |

| Funding Source | |

| Population | Number of Participants |

| Demographic | |

| Diagnostic Criteria for RA | |

| Inclusion Criteria | |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| Methods | Setting |

| Duration | |

| Dietary Intervention | |

| Control | |

| Randomisation | |

| Blinding | |

| Assessment of Compliance | |

| Outcome Measures | |

| Assessment of Disease Activity | |

| Assessment of Inflammatory Status | |

| Follow Up Period | |

| Results | Disease Activity Score 28 |

| Inflammatory Markers | |

| Secondary Outcomes | |

| Adverse Events | |

| Conclusion | Key Findings |

| Strengths | |

| Limitations | |

| Implications |

References

- Watchman, T. (no date) Rheumatoid arthritis, Zero To Finals. Available at: https://zerotofinals.com/medicine/rheumatology/ra/.

- Gioia C, Lucchino B, Tarsitano MG, Iannuccelli C, Di Franco M. Dietary Habits and Nutrition in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Can Diet Influence Disease Development and Clinical Manifestations? Nutrients. 2020 May 18;12(5):1456. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wong SH, Lord JM. Factors underlying chronic inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis (Nov/Dec 2004) Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz).52(6):379-88. [PubMed]

- Winkvist A, Bärebring L, Gjertsson I, Ellegård L, Lindqvist HM. A randomized controlled cross-over trial investigating the effect of anti-inflammatory diet on disease activity and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: the Anti-inflammatory Diet In Rheumatoid Arthritis (ADIRA) study protocol. Nutr J. 2018 Apr 20;17(1):44. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- NHS, Rheumatoid Arthritis (08/03/2023). Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis/.

- Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center, Rheumatoid Arthritis Pathophysioloy (2019). Available at: https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/rheumatoid-arthritis/ra-pathophysiology-2/.

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [Internet]. Versus Arthritis. (2022Oct15). Available from: https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis/.

- Services for people with rheumatoid arthritis - national audit office (NAO) report [Internet]. National Audit Office (NAO). 2022 (2022Oct19). Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/services-for-people-with-rheumatoid-arthritis/#:~:text=The%20estimated%20cost%20to%20the,%C2%A31.8%20billion%20a%20year.&text=Rheumatoid%20arthritis%20costs%20the%20NHS%20an%20estimated%20%C2%A3560%20million%20annually.

- Arthrits Foundation, DMARDs (no date) Available at: https://www.arthritis.org/drug-guide/dmards/dmards.

- Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center, Rheumatoid Arthritis Pathophysioloy (2019). Available at: https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/rheumatoid-arthritis/ra-pathophysiology-2/.

- Ferro M, Charneca S, Dourado E, Guerreiro CS, Fonseca JE. Probiotic Supplementation for Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Promising Adjuvant Therapy in the Gut Microbiome Era. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jul 23;12:711788. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; a Literature Review. Nutrients. 2015 Nov 5;7(11):9139-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Philippou E, Petersson SD, Rodomar C, Nikiphorou E. Rheumatoid arthritis and dietary interventions: systematic review of clinical trials. Nutr Rev. (09/03.2021);79(4):410-428. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BMJ (OPEN ACCESS) Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- van Riel, PL. The development of the disease activity score (DAS) and the disease activity score using 28 joint counts (DAS28). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014 Sep-Oct;32(5 Suppl 85):S-65-74. [PubMed]

- Ansar W, Ghosh S. Inflammation and Inflammatory Diseases, Markers, and Mediators: Role of CRP in Some Inflammatory Diseases. Biology of C Reactive Protein in Health and Disease. 2016 Mar 24:67–107. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016 Oct 4;4:2050312116671725. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jonathan Kay , Katherine S. Upchurch, ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria, Rheumatology, Volume 51, Issue suppl_6, December 2012, Pages vi5–vi9. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018 Oct;106(4):420-431. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Vadell AKE, Bärebring L, Hulander E, Gjertsson I, Lindqvist HM, Winkvist A. Anti-inflammatory Diet In Rheumatoid Arthritis (ADIRA)-a randomized, controlled crossover trial indicating effects on disease activity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020 Jun 1;111(6):1203-1213. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vaghef-Mehrabany E, Alipour B, Homayouni-Rad A, Sharif SK, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Zavvari S. Probiotic supplementation improves inflammatory status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2014 Apr;30(4):430-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist HM, Gjertsson I, Eneljung T, Winkvist A. Influence of Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis) Intake on Disease Activity in Female Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: The MIRA Randomized Cross-Over Dietary Intervention. Nutrients. 2018 Apr 13;10(4):481. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghaseminasab-Parizi M, Nazarinia MA, Akhlaghi M. The effect of flaxseed with or without anti-inflammatory diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2022 Apr;61(3):1377-1389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosavian SP, Paknahad Z, Habibagahi Z, Maracy M. The effects of garlic (Allium sativum) supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers, fatigue, and clinical symptoms in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2020 Nov;34(11):2953-2962. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimóteo NSB, Iryioda TMV, Alfieri DF, Rego BEF, Scavuzzi BM, Fatel E, Lozovoy MAB, Simão ANC, Dichi I. Cranberry juice decreases disease activity in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2019 Apr;60:112-117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guagnano MT, D'Angelo C, Caniglia D, Di Giovanni P, Celletti E, Sabatini E, Speranza L, Bucci M, Cipollone F, Paganelli R. Improvement of Inflammation and Pain after Three Months' Exclusion Diet in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Nutrients. 2021 Oct 9;13(10):3535. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zamani B, Farshbaf S, Golkar HR, Bahmani F, Asemi Z. Synbiotic supplementation and the effects on clinical and metabolic responses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2017 Apr;117(8):1095-1102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).