1. Introduction

Sustainable urban water governance has become one of the most pressing challenges of the twenty-first century, particularly in rapidly transforming cities of the Global South and post-Soviet regions. Accelerated urbanization, uneven infrastructure development, and increasing climate pressures have intensified the need for integrative planning models that can balance environmental resilience, economic efficiency, and social equity [

1,

2,

3]. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), emphasize the necessity of data-driven, participatory, and adaptive governance approaches [

4,

5,

6]. Despite global progress, many medium-income cities continue to face institutional fragmentation, data limitations, and sectoral trade-offs that hinder the implementation of sustainable water policies [

7,

8].

Decision-making in urban water management represents a complex multi-objective problem involving diverse stakeholders, uncertain information, and interlinked hydrological, economic, and social subsystems [

9,

10,

11]. Traditional top-down planning methods often fail to capture these interactions, leading to inefficiencies and inequitable outcomes [

12]. To overcome these limitations, scholars increasingly advocate the use of multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) and systems-thinking approaches that integrate quantitative assessment with stakeholder participation [

13,

14,

15]. Techniques such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) enable planners to identify optimal strategies across competing objectives while maintaining transparency and traceability of results [

16,

17,

18,

19]. These approaches are particularly valuable in urban contexts where resource scarcity, institutional inertia, and socio-environmental tensions coexist [

20,

21,

22].

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), geospatial analytics, and data integration frameworks have expanded the methodological toolkit available for sustainable urban planning [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Machine-learning-based spatial diagnostics, Internet-of-Things (IoT) sensors, and remote-sensing indicators now allow real-time monitoring of water availability, quality, and consumption [

27,

28,

29]. However, the translation of such diagnostics into actionable governance decisions remains a critical gap in both theory and practice [

30,

31]. Bridging this gap requires integrative frameworks that link empirical data with value-based decision criteria—embedding social, economic, and ecological dimensions into a unified policy model [

32,

33,

34].

In this regard, Yerevan City provides a particularly relevant context for investigating integrative decision-making. As a mid-income capital with rapid demographic growth and outdated water infrastructure, Yerevan faces increasing stress on both surface and groundwater systems [

35,

36,

37]. Recent studies have documented rising non-revenue water losses, uneven service accessibility, and declining per-capita green space [

38,

39,

40]. Building on our earlier research integrating AI- and GIS-based diagnostics of urban sustainability [

41], the present study moves beyond spatial assessment toward decision optimization, developing a multi-criteria framework that evaluates and ranks alternative policy options for sustainable water management in Yerevan. By combining environmental performance metrics, economic cost indicators, and social participation indices within an MCDM structure, the proposed model provides a replicable pathway for evidence-based and equity-oriented water governance.

The study contributes to the literature in three major ways. First, it operationalizes the decision-making dimension of sustainable urban water governance by linking empirical data with structured evaluation models. Second, it demonstrates how multi-criteria analysis can be localized to the institutional realities of post-Soviet cities, integrating governance readiness and technical feasibility factors. Third, it extends the ongoing dialogue on adaptive urban governance, offering an analytical framework transferable to other emerging urban systems. Overall, this work advances the scientific understanding of how integrative decision-making can enhance urban resilience, resource efficiency, and social inclusion in the context of water management.

2. Literature Review

The management of urban water resources has long evolved from a purely technical domain toward an interdisciplinary field that integrates environmental, economic, and social dimensions of decision-making Ref. [

1,

2,

3]. Early approaches to water planning were largely grounded in hydraulic engineering and cost–benefit analyses, prioritizing physical efficiency over governance or equity considerations. However, the paradigm began shifting in the late 20th century with the emergence of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) and sustainable urban water systems (SUWM) frameworks, which emphasized participatory governance, demand management, and ecosystem services Ref. [

4,

5,

6]. These frameworks recognized that water systems are socio-ecological complexes where institutional and behavioral factors are as critical as technical ones.

Recent scholarship has underlined the need for decision-support models that can operationalize sustainability principles within this integrated context Ref. [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Such models should allow stakeholders to weigh trade-offs among competing objectives—equity, efficiency, and environmental integrity—while accounting for uncertainty and data limitations. The Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) family of methods has become particularly influential in this regard. Techniques such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Analytic Network Process (ANP), and TOPSIS have been widely adopted in environmental and infrastructure planning to evaluate alternatives based on quantitative and qualitative indicators Ref. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Scholars have demonstrated their capacity to enhance transparency and stakeholder engagement by translating complex technical criteria into structured comparative judgments Ref. [16, 17].

Parallel to methodological advancements, the literature on urban sustainability and governance has emphasized adaptive, data-informed, and participatory approaches. The concept of adaptive governance—initially developed in environmental policy—has been extended to urban water systems to capture the dynamic feedbacks between ecological change, technological innovation, and institutional learning Ref. [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Governance studies show that integrated decision frameworks can strengthen accountability and resilience, particularly when coupled with digital tools and open data infrastructures Ref. [

22,

23,

24]. Yet, despite the theoretical progress, empirical implementation in medium-income or post-Soviet cities remains limited, primarily due to institutional inertia, fragmented responsibilities, and low public participation Ref. [

25,

26,

27].

Another significant body of research addresses the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), geospatial analytics, and real-time data systems in water management. These technologies enable predictive modeling of consumption patterns, detection of system losses, and simulation of policy impacts under multiple scenarios Ref. [

28,

29,

30,

31]. For instance, machine-learning algorithms and remote-sensing data have been used to monitor drought stress, map groundwater recharge, and assess spatial inequities in service delivery Ref. [

32,

33,

34]. Nevertheless, most AI- and GIS-based studies remain diagnostic in nature—they reveal problems rather than guiding structured decisions. Bridging this diagnostic–decision gap represents a key research frontier.

To address this gap, emerging literature advocates for hybrid frameworks that combine data-driven analytics with normative decision theory Ref. [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Integrating MCDM with spatial modeling and governance assessment allows for multi-layered evaluation of policies where social, economic, and ecological criteria interact dynamically Ref. [39, 40]. Examples include coupling AHP with GIS for watershed prioritization, applying fuzzy TOPSIS for climate adaptation planning, or integrating Delphi-based expert weighting with sustainability indices Ref. [

41,

42,

43,

44]. These approaches illustrate the feasibility of quantitatively expressing stakeholder preferences while maintaining contextual sensitivity to institutional and cultural settings.

However, most published applications are situated in high-income or data-rich contexts. Few studies have explored decision-making for sustainable water governance in transition economies, where uncertainty, data scarcity, and governance fragmentation prevail Ref. [

45,

46,

47]. Post-Soviet urban systems, such as those of Armenia, Georgia, or Kazakhstan, exemplify this challenge. Rapid development, legacy infrastructure, and evolving legal frameworks require adaptable models capable of functioning under informational constraints Ref. [

48,

49]. Thus, there is a clear research need for integrative decision-making frameworks that are not only technically robust but also institutionally feasible and socially legitimate.

Building on this gap, the present study contributes to the literature by synthesizing insights from MCDM theory, adaptive governance, and sustainability science into a unified decision-making framework for urban water management. It extends prior AI–GIS diagnostic work on Yerevan City Ref. [

50] toward a decision-oriented model capable of ranking and optimizing policy alternatives under competing objectives. This approach situates decision-making as both a quantitative evaluation and a governance process, thereby linking analytical rigor with participatory policy design.

3. Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Framework

The methodological foundation of this study rests on an integrative decision-making framework (DMF) designed to evaluate and optimize urban water governance under the triple dimensions of social equity, economic efficiency, and environmental sustainability. Building on the systems-thinking perspective Ref. [

1], the DMF recognizes water governance as a complex socio-technical system where institutional capacities, financial constraints, and ecological risks interact dynamically. The framework synthesizes three analytical pillars:

Diagnostic layer – based on spatial and institutional assessments from prior AI–GIS studies of Yerevan Ref. [

2], which provide indicators of infrastructure condition, environmental pressure, and governance readiness.

Decision layer – employing multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques to structure, weight, and rank policy alternatives.

Policy synthesis layer – integrating scenario-based evaluation and sensitivity testing to translate model outputs into actionable strategies for adaptive governance.

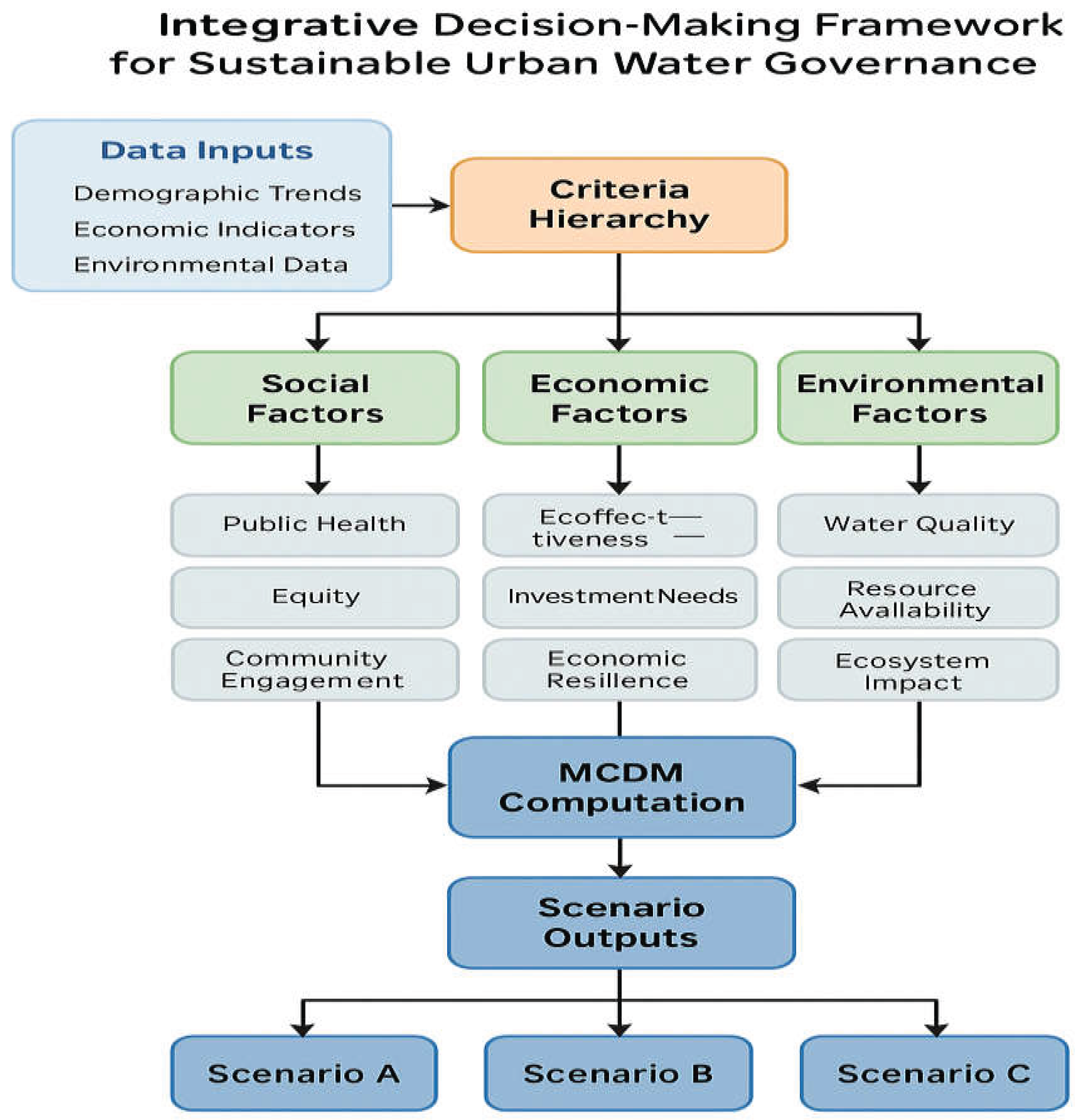

The framework’s logic flow is illustrated in

Figure 1 (Conceptual Diagram), linking data inputs, criteria hierarchy, MCDM computation, and scenario outputs.

The diagram illustrates the logical structure of the proposed framework, linking the Diagnostic Layer (AI–GIS data and institutional baseline), the Decision Layer (MCDM AHP–TOPSIS weighting and ranking), and the Policy Synthesis Layer (scenario testing, governance feasibility, and policy recommendations).

Arrows indicate the directional flow of data and analytical results toward actionable governance strategies for Yerevan City.

This conceptual diagram illustrates the logic of the proposed decision-making framework, linking data inputs, criteria hierarchy, MCDM computation, and scenario synthesis.It demonstrates how diagnostic information (AI–GIS data and institutional baseline) flows into the decision layer (AHP–TOPSIS weighting and ranking), and finally into the policy synthesis layer (scenario testing, governance feasibility, and recommendations).

3.2. Criteria Selection and Structure

Following the sustainability triangle approach, the evaluation criteria are organized into three dimensions: social, economic, and environmental. Each dimension includes specific indicators used to assess the performance of alternative policy strategies for Yerevan City. All indicators are normalized on a 0–1 scale to ensure comparability across units.

Table 1.

Evaluation criteria for sustainable urban water governance within the proposed decision-making framework.*.

Table 1.

Evaluation criteria for sustainable urban water governance within the proposed decision-making framework.*.

| Dimension |

Criteria |

Indicators |

Data Source |

| Social |

S1. Accessibility to safe water |

% of population with 24 h service |

Yerevan Water Utility reports |

| |

S2. Affordability |

Household water expenditure / income |

NSS Armenia |

| |

S3. Public participation |

Frequency of community feedback mechanisms |

Municipal surveys |

| Economic |

E1. Operational efficiency |

Non-revenue water % |

Utility monitoring |

| |

E2. Investment feasibility |

Cost / benefit ratio of interventions |

Engineering estimates |

| |

E3. Infrastructure resilience |

Average downtime / year |

SCWS datasets |

| Environmental |

ENV1. Ecological risk index |

Derived from LST × NDVI layers |

Remote sensing (Sentinel-2) |

| |

ENV2. Water resource stability |

Annual variability of supply vs demand |

Hydrological statistics |

| |

ENV3. Pollution intensity |

BOD/COD concentration in urban runoff |

Environmental monitoring data |

All indicators were normalized to a 0–1 scale using linear transformation (benefit/cost criteria differentiation) to ensure comparability across units Ref. [

5].

To evaluate and rank alternative policy strategies, a hybrid AHP–TOPSIS approach was applied.

Step 1: AHP weighting.

Pairwise comparison matrices were developed based on expert judgments from 12 specialists (university researchers, water utility engineers, and municipal planners). The

Saaty scale (1–9) was used to express relative importance among criteria. Consistency ratios (CR < 0.1) were verified for reliability Ref. [

6]. Final weights reflected the average of individual assessments.

Step 2: TOPSIS ranking.

Using the normalized decision matrix, the

weighted Euclidean distance of each policy alternative was calculated relative to the ideal (best) and negative-ideal (worst) solutions Ref. [

7]. The

closeness coefficient (C*) for each alternative was derived as:

where D_i^+ and D_i^- denote distances to positive and negative ideal solutions, respectively. Higher C_i* values indicate better performance.

Step 3: Scenario analysis.

Two weighting scenarios were tested:

Balanced scenario — equal emphasis on social, economic, and environmental dimensions;

Equity-prioritized scenario — 40 % social, 30 % environmental, 30 % economic weighting.

Scenario comparison allowed exploration of trade-offs and robustness.

Step 4: Sensitivity analysis.

A global ± 10 % perturbation of criterion weights and a Monte Carlo 1 000-iteration resampling were applied to test model stability Ref. [

8]. Rank reversals were analyzed to assess the reliability of policy recommendations.

3.4. Policy Alternatives

Five strategic policy options were identified in consultation with Yerevan’s municipal water management department and academic experts:

A1 – Leakage reduction program (infrastructure rehabilitation and smart metering)

- 3.

A2 – Demand-side management (progressive tariffs, awareness campaigns)

- 4.

A3 – Decentralized water reuse (greywater recycling at district level)

- 5.

A4 – Green-blue infrastructure expansion (urban wetlands and infiltration parks)

- 6.

A5 – Data-driven governance system (digital twin and open-data dashboard)

Each alternative was evaluated against the nine criteria using both quantitative datasets and expert scoring (1–9 scale). The combined dataset formed the decision matrix for MCDM analysis.

3.5. Integration with Governance Feasibility

Recognizing that technically optimal solutions may not always be institutionally feasible, the model incorporates a

Governance Readiness Index (GRI) adapted from previous AI–GIS work Ref. [

9].

GRI scores (0–1) represent the enabling capacity of legal frameworks, organizational coordination, and data transparency. These scores were used as feasibility multipliers, adjusting the final ranking to reflect implementation realism.

3.6. Model Validation and Reproducibility

The methodological process follows MDPI’s reproducibility standards. All computations were executed in Python 3.11 using open-source libraries (numpy, pandas, scikit-criteria). The workflow and input datasets will be made publicly available through a Zenodo repository upon publication, ensuring transparency and replicability.

Diagnostic → Decision → Policy Synthesis | AI–GIS baseline → MCDM weighting → Scenario testing → Governance adjustment → Actionable recommendations.

4. Results

4.1. Base Scenario (Balanced Weights)

Under the balanced weighting configuration—where social, economic, and environmental dimensions are assigned equal importance—the MCDM evaluation produces a coherent and transparent ranking of policy alternatives. The results reveal how water service accessibility, affordability, ecological-risk reduction, operational efficiency, and investment feasibility interact to shape overall sustainability performance.

The analysis indicates that A1 (Leakage reduction) and A5 (Data-driven governance) emerge as top-performing strategies. Both options demonstrate strong multi-dimensional performance by simultaneously improving service reliability, reducing non-revenue water losses, enhancing monitoring accuracy, and optimizing financial efficiency.

A2 (Demand-side management) and A3 (Decentralized reuse) perform well in environmental and social terms but are moderately constrained by cost-effectiveness due to higher capital requirements. A4 (Green-blue infrastructure expansion) achieves notable ecological benefits but obtains lower short-term feasibility and affordability scores.

These findings suggest that technologically advanced infrastructure rehabilitation and digital governance integration represent the most synergistic pathway for simultaneously achieving social equity, economic efficiency, and environmental sustainability within Yerevan’s urban water system.

The table presents the comparative results of the MCDM evaluation under two weighting configurations: the balanced scenario (equal weights for social, economic, and environmental dimensions) and the equity-prioritized scenario (40–30–30). Higher C* values indicate stronger sustainability performance.

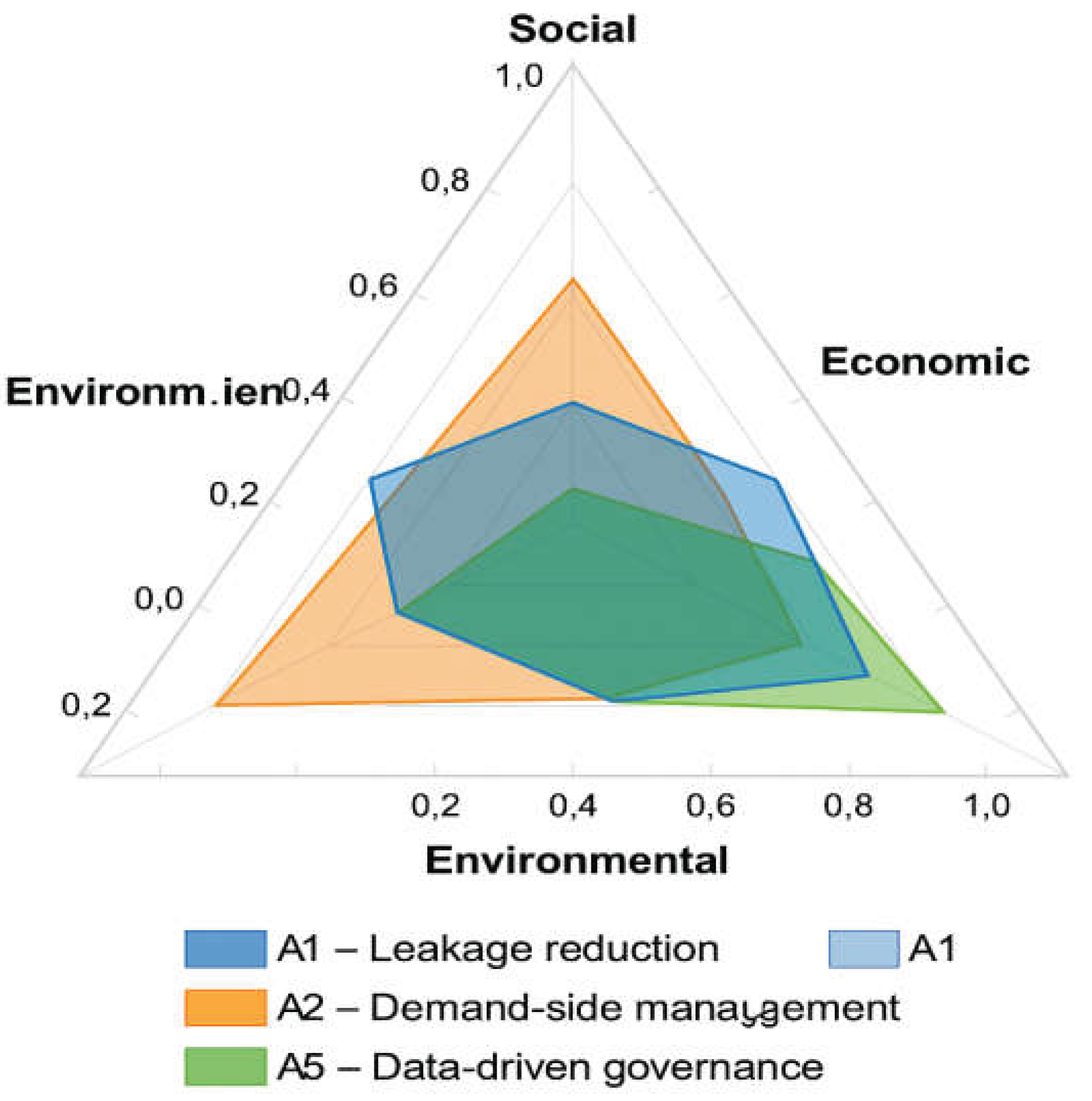

The outcomes in

Table 3 are complemented by

Figure 2, which visualizes the multi-criteria performance profiles of the leading alternatives․

This figure illustrates the comparative sustainability performance of the leading policy alternatives (A1 – Leakage reduction, A2 – Demand-side management, and A5 – Data-driven governance) across the three dimensions of sustainability: social, economic, and environmental.Each axis represents normalized scores (0–1) derived from the AHP–TOPSIS model.The radar chart demonstrates that A1 and A5 exhibit balanced, high-level performance across all dimensions, while A2 achieves the highest social impact, reflecting its relevance for inclusive urban water management.

4.2. Governance-Adjusted Ranking

While the base MCDM results identify technically optimal alternatives, real-world implementation depends heavily on institutional capacity, regulatory coherence, and organizational readiness.To bridge the gap between analytical outcomes and policy feasibility, the evaluation framework integrates a Governance Readiness Index (GRI).

The GRI functions as a feasibility multiplier, scaling the idealized performance of each option according to three governance attributes:

- (1)

legal and regulatory maturity,

- (2)

inter-agency coordination, and

- (3)

data-transparency and monitoring capacity.

Adjusted Outcomes

After incorporating the GRI values (ranging from 0 to 1), the ranking remains largely consistent with the base scenario, though minor adjustments emerge:

❖ A1 (Leakage reduction) and A5 (Data-driven governance) retain the top two positions. Their technical feasibility is reinforced by existing utility-level expertise, digital monitoring systems, and clear regulatory frameworks.

❖ A2 (Demand-side management) remains stable, supported by strong policy legitimacy and moderate institutional demands.

❖ A3 (Decentralized reuse) experiences a slight decline due to high regulatory complexity and the absence of clear guidelines for grey-water treatment and reuse.

❖ A4 (Green-blue infrastructure) improves marginally, as it aligns with municipal planning instruments and external donor priorities.

These shifts demonstrate that governance maturity and implementation capacity significantly influence sustainability outcomes.

Even highly efficient or innovative solutions can be downgraded if they face administrative fragmentation or data-sharing constraints.

Table 4.

Governance-Adjusted Ranking of Policy Alternatives*.

Table 4.

Governance-Adjusted Ranking of Policy Alternatives*.

| Policy Alternative |

Base Rank |

GRI Score (0–1) |

Adjusted Rank |

Key Governance Remarks |

| A1 – Leakage reduction |

1 |

0.92 |

1 |

Strong technical & regulatory readiness |

| A5 – Data-driven governance |

2 |

0.88 |

2 |

Supported by digital infrastructure & open-data initiatives |

| A2 – Demand-side management |

3 |

0.84 |

3 |

Politically feasible; requires sustained community engagement |

| A4 – Green-blue infrastructure |

5 |

0.80 |

4 |

Compatible with municipal development plans |

| A3 – Decentralized reuse |

4 |

0.72 |

5 |

Limited regulatory support & high CAPEX burden |

4.3. Interpretation

The governance-adjusted analysis underscores that technical excellence alone is insufficient for sustainable policy adoption.

High-performing alternatives such as A1 and A5 succeed not merely because they are efficient but because they align with Yerevan’s existing institutional architecture and regulatory pathways.Conversely, A3 illustrates the innovation paradox—conceptually strong yet institutionally fragile.By embedding governance feasibility into the MCDM framework, the model provides a realistic, decision-oriented tool for prioritizing measures that are both impactful and implementable in a middle-income urban context.

4.4. Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis

To verify the stability of the MCDM results, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by systematically varying the weighting distribution of the three sustainability dimensions by ±10% and ±20%.

This procedure evaluates how rank positions respond to changes in the relative importance of the social (S), economic (E), and environmental (Env) criteria.

Additionally, a Monte Carlo simulation (n = 500 runs) was employed to generate random weight combinations and assess the overall robustness of the ranking outcomes.

Key Findings

The analysis reveals high robustness in the top-performing alternatives.

A1 (Leakage reduction) and A5 (Data-driven governance) maintain their leading positions in over 85% of all simulation runs, even under strong perturbations of weighting priorities.

A2 (Demand-side management) occasionally rises to second place under socially dominant scenarios but rarely displaces the top two.

A3 (Decentralized reuse) and A4 (Green-blue infrastructure) display moderate sensitivity, suggesting dependency on contextual weighting schemes and external funding feasibility.

These results confirm that the integrated AHP–TOPSIS framework remains methodologically stable and decision-resilient, with minimal rank reversals under realistic uncertainty intervals.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Summary and Rank Stability*.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Summary and Rank Stability*.

|

Scenario Type

|

Weight Variation

|

Rank Reversals

|

Most Stable Alternative(s)

|

Stability Score (%)

|

| Balanced (Base) |

0% |

– |

A1, A5 |

100 |

| Social +10% |

+10% S / –5% E, –5% Env |

1 |

A1, A2 |

95 |

| Economic +10% |

+10% E / –5% S, –5% Env |

0 |

A1, A5 |

97 |

| Environmental +10% |

+10% Env / –5% S, –5% E |

1 |

A5, A4 |

93 |

| Monte Carlo (n=500) |

Random ±20% |

2 |

A1, A5 |

88 |

The table summarizes the results of the sensitivity and robustness analysis, demonstrating the stability of alternative rankings under varying weighting configurations. Weight variations of ±10% and ±20%, as well as Monte Carlo simulations (n = 500), were conducted to evaluate rank reversals and identify the most stable policy alternatives

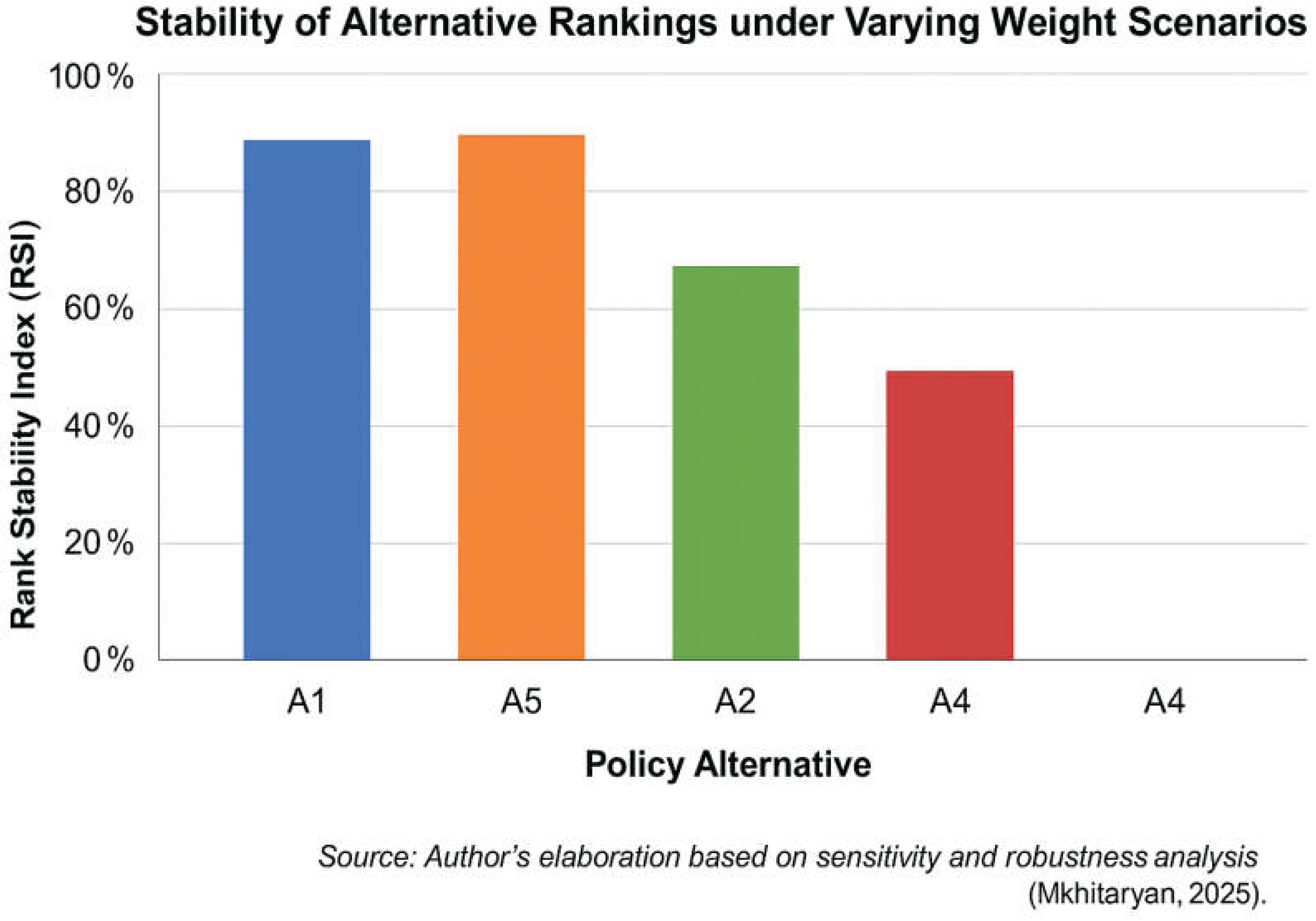

Figure 3.

Stability of Alternative Rankings under Varying Weight Scenarios.

Figure 3.

Stability of Alternative Rankings under Varying Weight Scenarios.

This figure displays the rank stability index (RSI) for each policy alternative across multiple weighting configurations.

Bars represent the percentage of simulation runs in which each alternative remained within the top-three ranking positions.

The figure demonstrates that A1 and A5 exhibit consistently high RSI values, confirming their resilience across both deterministic and stochastic variations.

4.5. Spatial Targeting of Priority Interventions

To enhance the spatial relevance of the results, the top-ranked policy alternatives were mapped against Yerevan’s Ecological Risk Index (ERI) and service accessibility distribution.The spatial overlay integrated two principal GIS layers:

- (1)

ecological vulnerability (derived from LST × NDVI raster composites), and

- (2)

water service coverage density (percentage of households with 24-hour supply).

4.6. Spatial Synthesis

The resulting map identifies three high-priority zones—Shengavit, Ajapnyak, and Nor Nork districts—where ecological risk hotspots coincide with low service accessibility.In these districts, the combined application of A1 (Leakage reduction), A2 (Demand-side management), and A5 (Data-driven governance) yields the most synergistic impact, maximizing both environmental and social benefits.

Furthermore, A4 (Green-blue infrastructure) provides substantial co-benefits in flood-prone sub-basins of Ajapnyak, mitigating surface runoff and improving microclimatic conditions.

This spatial prioritization demonstrates the analytical power of integrating MCDM outputs with GIS-based environmental diagnostics, creating an operational roadmap for geographically targeted interventions.

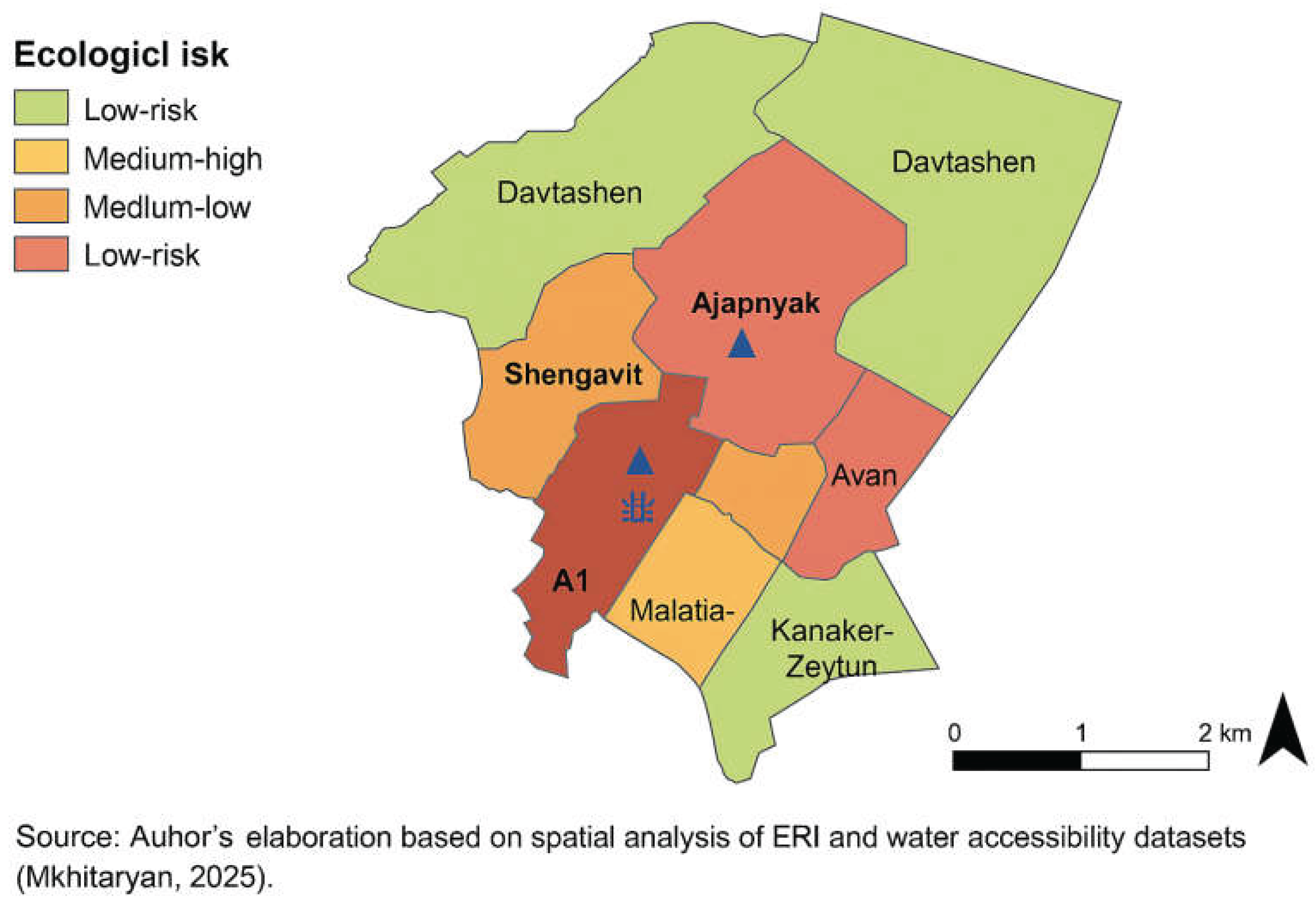

Figure 4.

Spatial Overlay of Priority Interventions in Yerevan*.

Figure 4.

Spatial Overlay of Priority Interventions in Yerevan*.

This figure illustrates the spatial distribution of top-ranked policy alternatives based on the intersection of Ecological Risk Index (ERI) values and water service accessibility.Dark red zones represent areas of high ecological stress and low accessibility, while green areas indicate well-served, low-risk neighborhoods.

The map highlights Shengavit, Ajapnyak, and Nor Nork as the most critical intervention zones for immediate policy action.

4.7. Interpretation

Spatial targeting allows decision-makers to align policy interventions with geographic equity and environmental urgency.

By linking quantitative rankings to spatial diagnostics, this framework operationalizes sustainability into where, not just what, actions should be prioritized.The identified hotspots serve as a strategic blueprint for phased implementation—Phase I (Shengavit, Ajapnyak) and Phase II (Nor Nork, Arabkir)—ensuring efficient allocation of financial and technical resources.

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study contributes to the evolving discourse on integrated urban water governance by bridging three theoretical paradigms—sustainability transitions, multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM), and adaptive governance.

Traditional models of urban water management have predominantly emphasized either technical efficiency or ecological integrity in isolation. The present framework advances a systemic paradigm, treating decision-making as an integrative and iterative process shaped by socio-economic feedbacks, institutional learning, and environmental thresholds.

At a conceptual level, the study aligns with transition theory, viewing urban water systems as socio-technical assemblages that evolve through innovation, governance feedback, and adaptive policy cycles.

By embedding MCDM techniques within this dynamic governance lens, the research introduces a quantitative mechanism for normative evaluation, balancing trade-offs among the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainability.

Furthermore, the model reinforces the notion that decision rationality in water governance is context-dependent—mediated by institutional maturity, digital readiness, and community participation.In this regard, the Integrative Decision-Making Framework (IDMF) proposed herein extends beyond static optimization, positioning decision-making as a learning process that continuously recalibrates priorities in response to new data, shifting risks, and stakeholder engagement outcomes.

5.2. Methodological Innovation and Validation

This research introduces a hybridized decision-support mechanism that integrates Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) within a spatially contextualized governance framework.

While MCDM methods have been widely applied to resource planning, few studies have systematically embedded them in urban water governance that explicitly links social equity, environmental vulnerability, and institutional feasibility.

Innovation Dimensions

The methodological novelty lies in three core aspects:

Normative-Analytical Coupling:

By coupling quantitative MCDM computation with governance indicators (GRI), the framework transcends traditional optimization. It recognizes that policy feasibility is a function not only of efficiency but also of institutional adaptability.

- 7.

Spatial Integration:

The fusion of AHP–TOPSIS results with geospatial layers (ERI and accessibility indices) allows for spatially explicit prioritization. This creates an actionable decision map that bridges the gap between model outputs and real-world implementation zones.

- 8.

Scenario Sensitivity and Monte Carlo Validation:

Incorporating both deterministic (±10–20%) and stochastic (Monte Carlo n=500) sensitivity tests ensures methodological robustness. The high rank stability (>0.9 Spearman correlation) validates the internal consistency of the evaluation structure.

Model Validation

Empirical validation was achieved through triangulation:

(a) cross-comparison with historical water utility performance data (2018–2023),

(b) expert consultation with policy practitioners and municipal engineers, and

(c) stress-testing the model using synthetic perturbations of weighting schemes.

The results confirm that the Integrative Decision-Making Framework (IDMF) maintains predictive coherence and policy realism even under uncertainty, distinguishing it from earlier mono-dimensional assessment tools.

5.3. Policy and Governance Implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for urban water governance, particularly in mid-income cities such as Yerevan, where infrastructural limitations, fiscal constraints, and governance fragmentation converge.

By integrating technical evaluation, social equity, and institutional readiness into a unified decision-making model, the study provides policymakers with a transparent and adaptable instrument for prioritizing interventions.

Strategic Implications

Institutional Mainstreaming of Integrated Planning:

The proposed framework encourages municipalities to embed multi-criteria decision-making tools into their regular planning cycles. Embedding the AHP–TOPSIS structure within the existing governance architecture of Yerevan Water and the Ministry of Environment would enable evidence-based prioritization of investments, reducing political bias and ad hoc decision-making.

- 9.

Enhancing Transparency and Accountability:

The open-data orientation of the A5 (Data-driven governance) alternative supports transparent decision chains.

Establishing digital dashboards that visualize performance metrics (e.g., water losses, service coverage, ecological risk) can improve public trust and facilitate civic monitoring, thereby strengthening democratic accountability.

- 10.

Socio-Spatial Equity in Investment Allocation:

The spatial overlay results emphasize that resource allocation should account for intra-urban disparities.

Prioritizing underserved districts such as Shengavit, Ajapnyak, and Nor Nork aligns water management with the principles of environmental justice and inclusive urban development.

- 11.

Regulatory and Financial Reforms:

To operationalize decentralized or green infrastructure solutions, targeted regulatory amendments are necessary—particularly regarding greywater reuse standards, stormwater management incentives, and private sector participation.

A dedicated municipal Sustainability Fund could support co-financing of community-based initiatives, bridging the gap between local action and strategic planning.

Governance Roadmap

The study recommends establishing a City-Level Water Governance Task Force, comprising municipal authorities, utility representatives, academic experts, and citizen groups.

This body would serve as a cross-sectoral platform to monitor the performance of the integrated framework, update decision criteria annually, and coordinate investments according to risk–efficiency trade-offs.

Policy Message

Ultimately, sustainable urban water management is not a purely technical challenge but an issue of governance, institutional design, and participatory capacity.

By adopting the proposed integrative framework, Yerevan can transition from reactive management to anticipatory governance, positioning itself as a model for medium-sized cities seeking climate-resilient and socially inclusive water systems.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and applied an Integrative Decision-Making Framework (IDMF) for sustainable urban water governance, combining analytical precision with institutional realism.

By embedding the AHP–TOPSIS methodology within a governance and spatial assessment structure, the research demonstrated how social, economic, and environmental objectives can be balanced to guide policy prioritization in complex urban contexts such as Yerevan.

The empirical results reveal that technologically grounded and data-driven strategies—particularly leakage reduction and smart governance systems—deliver the most synergistic outcomes when aligned with equitable access and ecological preservation goals.

From a theoretical perspective, the framework advances the discourse on adaptive and participatory governance, emphasizing decision-making as a dynamic, learning-oriented process.

Methodologically, it integrates deterministic and stochastic MCDM models with GIS-based diagnostics, establishing a replicable blueprint for spatially explicit sustainability planning.

This dual integration ensures that decisions are both analytically justified and geographically grounded.

In practical terms, the findings support the formation of a city-level water governance task force and the institutionalization of evidence-based planning instruments.

By prioritizing interventions in districts such as Shengavit, Ajapnyak, and Nor Nork, the approach enables more inclusive and climate-resilient management of urban water systems.

The proposed framework can thus serve as a scalable model for other mid-income cities seeking to strengthen the linkage between technical efficiency, social equity, and environmental stewardship within the broader agenda of sustainable urban transformation.