Introduction

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is a significant public health issue, with even mild TBI leading to cardiovascular events and fatalities [

1]. Cardiac injury in TBI can be seen with arrhythmias, regional wall motion alteration, troponins, myocardial stunning and even takotsubo cardiomyopathy [

2]. In TBI, autonomic dysregulation results in cardiac arrhythmias. These are commonly associated with prolonged QTc, supraventricular arrhythmias, other studies have shown atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, premature atrial contraction and bradycardia [

3]. We present a rare case of a patient with TBI presenting with multiple episodes of sinus arrest which improved with decreased intracranial pressure.

Case Presentation

A 37-year-old man with no prior medical conditions was brought to the emergency department following a physical assault that involved multiple blows to the head and upper body. On arrival, he was unresponsive, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6 (E1V1M4). His initial vital signs included a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, heart rate of 68 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation of 96% on room air, and a temperature of 98.4 °F (36.9 °C). Due to his reduced level of consciousness and inability to protect his airway, he was intubated and sedated shortly after presentation.

The primary trauma survey revealed no significant thoracic or abdominal injuries, but there was a large contusion over the right temporal area with underlying scalp hematoma. The secondary examination showed visible shoulder deformities bilaterally, with restricted range of motion. Initial laboratory results, including complete blood count, metabolic profile, and arterial blood gas, were within normal limits. Electrolyte levels—particularly potassium, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus—were unremarkable, ruling out metabolic causes for arrhythmia. The toxicology screen was also negative.

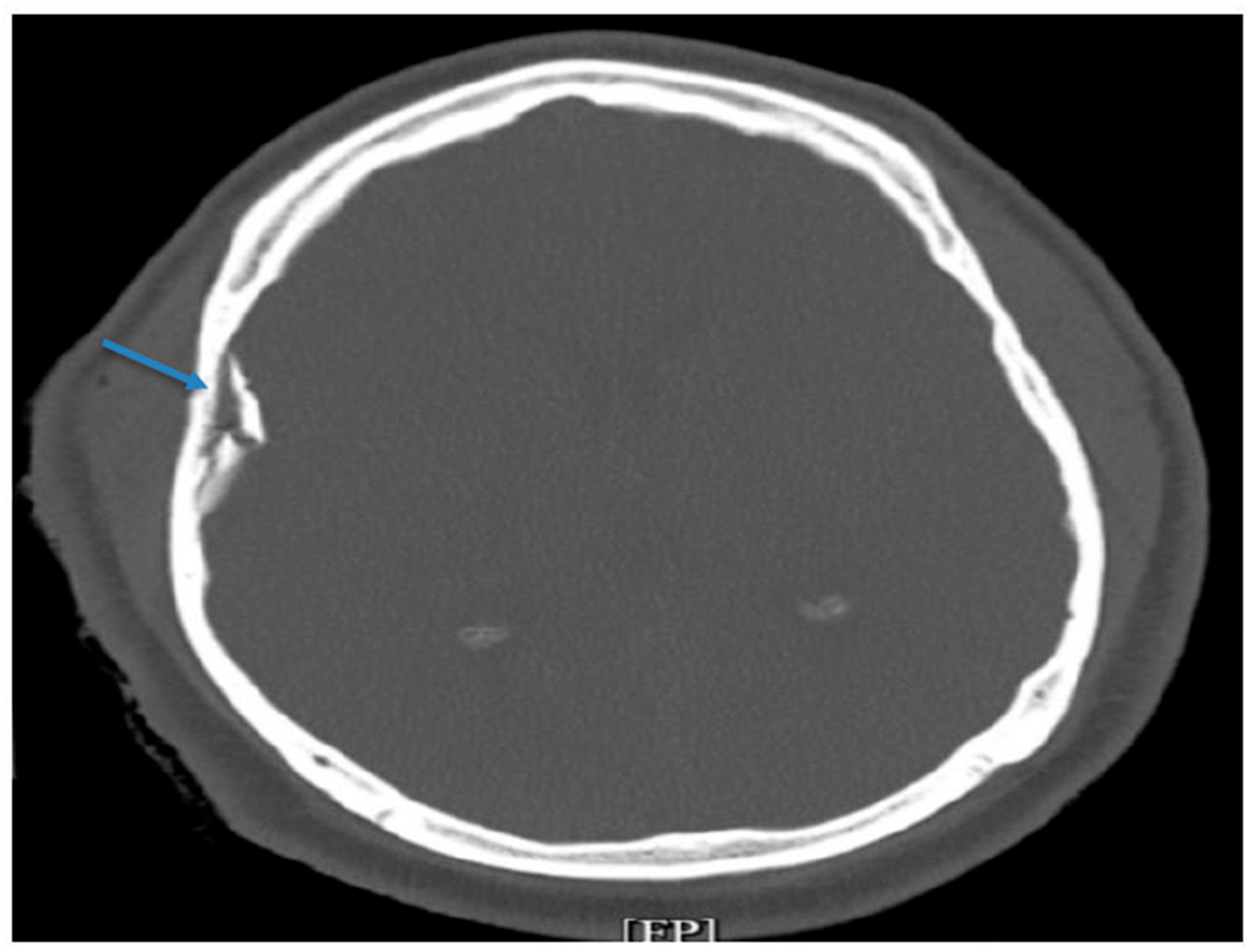

A non-contrast CT scan of the head revealed an acute, depressed, and comminuted right temporoparietal skull fracture with a small associated contusion but no midline shift (Figure 1). There was also mild pneumocephalus and scattered subarachnoid hemorrhage. Additional imaging demonstrated bilateral displaced humeral head fractures with posterior glenohumeral subluxation, consistent with impact injuries sustained during the assault. The neurosurgical team performed an urgent craniotomy with elevation of the right temporal bone fracture and removal of the associated hematoma. An External Ventricular Drain (EVD) was placed intraoperatively to monitor intracranial pressure (ICP) and allow cerebrospinal fluid diversion.

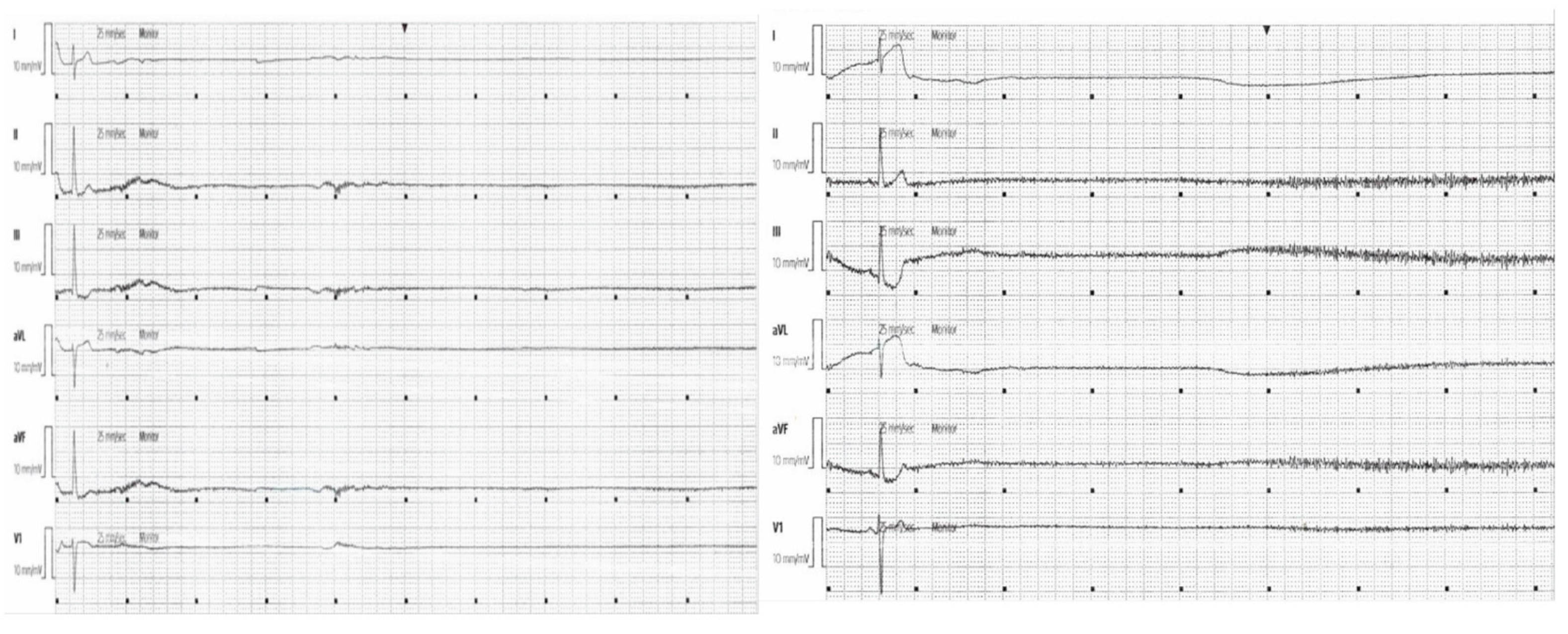

Postoperatively, the patient was admitted to the ICU for continuous neurological and cardiac monitoring. Initial ICP readings were elevated, averaging 22–25 mmHg. Sedation was maintained with propofol and fentanyl, and his blood pressure was closely managed to sustain adequate cerebral perfusion. Approximately 12 hours after admission, the patient developed multiple spontaneous sinus arrest episodes lasting up to 15 seconds as seen on telemetry (Figure 2). During these pauses, his heart rate dropped to zero, accompanied by a loss of arterial pressure tracing, though spontaneous recovery occurred without cardiopulmonary resuscitation. His blood pressure briefly declined to 70/40 mmHg during these episodes. No electrolyte abnormalities, hypoxia, or medication-related causes were identified.

Given the frequency and duration of these sinus arrests, a transvenous pacemaker (TVP) was inserted via the right internal jugular vein to maintain stable cardiac output and cerebral perfusion. Following TVP placement, his mean arterial pressures improved and remained consistently above 80 mmHg. Over the next 72 hours, serial ICP recordings showed progressive improvement, decreasing to 12–15 mmHg, which coincided with the resolution of sinus arrest episodes. This close relationship between elevated ICP and the cardiac conduction disturbance suggested a neurocardiac mechanism.

Once the patient’s intracranial pressure stabilized and EVD drainage decreased, the TVP was successfully discontinued. He remained stable thereafter, maintaining a heart rate of 70–85 beats per minute without further arrhythmias. A repeat echocardiogram demonstrated normal left ventricular function with no signs of myocardial injury.

As his neurological status improved to a GCS of 14, he was extubated and transitioned to spontaneous breathing. Orthopedic evaluation recommended conservative management for his bilateral shoulder fractures, with outpatient follow-up for rehabilitation. After 14 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged home on a 24-hour Holter monitor with outpatient cardiology follow-up.

Figure 1.

CT imaging acute depressed and comminuted right temporoparietal skull fracture (blue arrow).

Figure 1.

CT imaging acute depressed and comminuted right temporoparietal skull fracture (blue arrow).

Figure 2.

Two Cardiac telemetry strips showing sinus arrests greater than 15 seconds each.

Figure 2.

Two Cardiac telemetry strips showing sinus arrests greater than 15 seconds each.

Discussion

TBI patients are usually treated in the ED and admitted to the ICU for treatment based on ICP. In our patient, who had a comminuted fracture, craniotomy was performed, and an EVD was placed which also assisted with ICP monitoring. [

3] The patient was admitted to ICU where EKG and telemetry are used to assess vital function to monitor outcomes. While the effects of various neurological conditions such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke, and seizure on the heart has been well described, the literature of ECG abnormalities around TBI is still evolving [

4]. Although prior studies have assessed EKG changes and arrhythmias associated with TBI, our patient presented with a rare presentation of sinus arrests in this setting.

ECG changes have been associated with severe TBI; however the vast majority are ventricular repolarization disorders, including ST-segment abnormalities, abnormal T-wave, pathological q waves [

3]. Another major category includes conduction disorders with QT prolongation and abnormal QRS complexes. Cardiac arrhythmias are more commonly observed with severely increased ICP but typically supraventricular, mostly seen as sinus tachycardia or sinus bradycardia [

3]. Less commonly seen were occurences of atrial or atrioventricular junctional dysfunction. Keys to understanding the cause of these arrhythmias is the high catecholamine state associated with TBI as well as concomitant myocardial injury [

3,

4,

5].

Following TBI, there is a marked surge in circulating catecholamines, primarily norepinephrine and epinephrine. This drives systemic complications including paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity causing episodic hypertension, tachycardia, hyperthermia, diaphoresis and systemic organ dysfunction. It can even lead to increased cerebral edema amplifying neuroinflammation [

6]. These are one of the reasons why Beta-blockers have been tested for use in TBI, a previous meta-analysis had done significant mortality benefit with use of beta-blockers [

7]. However, in the case of our patient, early use of beta-blockers could have likely worsened his sinus arrests leading to worsened outcomes.

Hypotension is a common instability seen in TBI. Hypotension is an independent predictor of outcome for severe TBI and is significantly associated with increased mortality and is the most amenable to prevention [

8]. Perceived causes intravascular depletion in setting of bleeds, secondary to ICP induced diabetes insipidus, myocardial contusion, or spinal cord injury [

8]. Less commonly as mentioned before could be seen in the setting of bradyarrhythmias including Atrioventricular dysfunction and sinus bradycardia. However at times, the opposite is also seen due to a Cushing’s reaction there is hypertension and bradycardia.

Early use of TVP for the sinus arrests, especially in the TBI setting, likely reduced secondary brain injury by maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion. However, there are limitations to the use of TVP in TBI and Increased ICP as there is little research or description in the literature for its use. Further research on bradyarrhythmias, sinus arrests as well as atrioventricular dysfunctions need to be studied for optimal use of TVP in the setting of TBI.

Conclusion

This case underscores the rare but serious occurrence of sinus arrest following traumatic brain injury and the importance of recognizing neurocardiac dysfunction in this setting. Temporary pacing played a crucial role in maintaining cerebral perfusion until intracranial pressure improved. Further study is needed to guide optimal management, as current evidence remains limited.

Author Contributions

Dr. Krishna Patel & Chris Sani – Primary author; conceptualized, designed, and led the study. • Dr. Asher Gorantla – Assisted with case identification and provided clinical and academic expertise. • Dr. Varshitha T. Panduranga – Contributed to literature review, data analysis, and manuscript editing. • Dr. Usaid Raqeeb– Assisted with acquisition of imaging data and preparation of case presentations. • Dr. Adam S. Budzikowski – Served as mentor; guided study design, manuscript review, and quality assurance. Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Disclosures

No Conflict of interests to disclose.

Funding and Disclosures

This study received no external funding or financial support. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Informed: consent: was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Cardiovascular Division at SUNY Downstate Medical Center and the Interventional Cardiology Team for their continued support and expertise throughout this study.

References

- Hilz, M. J., DeFina, P. A., Anders, S., Koehn, J., Lang, C. J., Pauli, E., Flanagan, S. R., Schwab, S., & Marthol, H. (2011). Frequency analysis unveils cardiac autonomic dysfunction after mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma, 28(9), 1727–1738. [CrossRef]

- Coppalini, G., Salvagno, M., Peluso, L., Bogossian, E. G., Quispe Cornejo, A., Labbé, V., Annoni, F., & Taccone, F. S. (2024). Cardiac Injury After Traumatic Brain Injury: Clinical Consequences and Management. Neurocritical care, 40(2), 477–485. [CrossRef]

- Lenstra, J. J., Kuznecova-Keppel Hesselink, L., la Bastide-van Gemert, S., Jacobs, B., Nijsten, M. W. N., van der Horst, I. C. C., & van der Naalt, J. (2021). The Association of Early Electrocardiographic Abnormalities With Brain Injury Severity and Outcome in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Frontiers in neurology, 11, 597737. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, V., Prathep, S., Sharma, D., Gibbons, E., & Vavilala, M. S. (2014). Association between electrocardiographic findings and cardiac dysfunction in adult isolated traumatic brain injury. Indian journal of critical care medicine : peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 18(9), 570–574. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, V., Manley, G. T., Jain, S., Sun, S., Foreman, B., Komisarow, J., Laskowitz, D. T., Mathew, J. P., Hernandez, A., James, M. L., Vavilala, M. S., Markowitz, A. J., Korley, F. K., & TRACK-TBI Investigators (2022). Incidence and Clinical Impact of Myocardial Injury Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Pilot TRACK-TBI Study. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology, 34(2), 233–237. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Sheng, J., Peng, G., Yang, J., Wang, S., & Li, K. (2017). Early stage alterations of catecholamine and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels in posttraumatic acute diffuse brain swelling. Brain research bulletin, 130, 47–52. [CrossRef]

- Alali, A. S., Mukherjee, K., McCredie, V. A., Golan, E., Shah, P. S., Bardes, J. M., Hamblin, S. E., Haut, E. R., Jackson, J. C., Khwaja, K., Patel, N. J., Raj, S. R., Wilson, L. D., Nathens, A. B., & Patel, M. B. (2017). Beta-blockers and Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Guideline. Annals of surgery, 266(6), 952–961. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, S.H., Arabi, Y.M. Critical care management of severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 20, 12 (2012). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).