1. Introduction

In 2019, about 55% of 55.4 million deaths worldwide were due to 10 causes which included ischemic heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infection, neonatal conditions, broncho-pulmonary cancer, dementia, diarrheal disease, diabetes mellitus, and kidney disease. The leading causes amongst these were ischemic heart disease (16%) followed by stroke (10%). About 12.2 million incident strokes and 101 million prevalent cases of stroke have been reported in 2019 leading to 6.55 million deaths. Most deaths occurred during acute strokes [

1]. Large multicenter population-based studies have reported the requirement of mechanical ventilation (MV) in 10-15% of stroke patients admitted to the hospital. The requirement of MV is higher in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (29-30%) compared to ischemic strokes (8%) [

2]. The prognosis of these ventilated patients is poor with a high frequency of in-hospital and post-discharge mortality [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is also considered a stroke-like illness and accounts for 0.5%-1% of all strokes [

11]. The patients with CVT often present with raised intracranial pressure, and about half of the patients have seizures and parenchymal lesions in the form of infarction, hemorrhagic infarction, or intracerebral hematoma [

12,

13,

14,

15]. There is a paucity of studies evaluating the death and disability of CVT patients requiring MV [

16,

17]. In this communication, we report the predictors of MV in CVT patients requiring ICU admission. We also evaluate the short and long-term outcomes of patients requiring MV compared to those without MV.

2. Material and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of the CVT patients admitted to the ICU. The data were extracted from a prospectively maintained CVT registry from 2010 to February 2022. The study was conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital in India, and the Institute Ethics Committee approved the ethical permission (PGI/BE/774).

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The CVT patients aged ≥ 15 years and admitted to neurology ICU were included. The CVT patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of ≤ 13 were admitted to the ICU. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis was suspected in a patient presenting with new onset headache, seizure, focal neurological deficit, or papilloedema. The diagnosis of CVT was confirmed by an MR venography.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The patients with malignancy, rhino-cerebral fungal infection, organ transplantation, cancer chemo or radiotherapy, children < 15 years, and those with liver, kidney or heart failure were excluded.

2.3. Clinical Evaluation

The demographic information (age, gender, dietary habit) and clinical details were noted. The duration of illness and the presenting symptoms including headache, vomiting, seizure, focal motor deficit, visual loss, diplopia, altered sensorium, and somnolence were recorded. Consciousness was assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). The presence of papilloedema and cranial nerve palsy were recorded. Muscle power was classified on a 0-V Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. Muscle tone, tendon reflexes, sensations, and in coordination were noted.

2.4. Risk Factor Evaluation

Female patients, pregnancy, puerperium and use of oral contraceptive pills were noted. They were evaluated for genetic (factor V Leiden, MTHFR, antithrombin III, protein C and S deficiency) and acquired prothrombotic states ((homocysteine, antiphospholipid antibody; antinuclear antibody, anti-ds-DNA, and screening test for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria). In the patients with hyperhomocysteinemia, serum folic acid and vitamin B12 were measured.

2.5. Investigations

Blood counts, hemoglobin, erythrocytes sedimentation rate at 1st hour, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, bilirubin, transaminase, sodium, potassium, calcium, alkaline phosphatase and albumin were done. A thyroid profile was done in the suspected patients.

2.6. MRI and MR Venography

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging was performed using 1.5/3T MRI machine (Signa GE Medical System, Wisdom, USA). The location and nature of the parenchymal lesion were noted. Contrast MRV was done, and the location and extent of thrombosis of the sinuses were noted. The cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) score was also calculated [

12,

18,

19].

2.7. Mechanical Ventilation

The patients were intubated and mechanically ventilated if they fulfilled the following criteria [

20].

- (a)

PaO2 < 60 mm of Hg on venti musk

- (b)

PaCO2 > 50mm of Hg

- (c)

pH< 7.3

Tracheostomy was done if MV was needed for >15 days. The duration of MV and ventilator-associated pneumonia were noted. The other complications such as pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, bedsore, and septicemia were noted in both MV and non-MV groups.

2.8. Treatment

The patients were treated with low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin 100 unit/kg twice daily) for 10 days. Some patients (who could not afford it financially) received unfractionated heparin (5000 IU intravenously followed by 18 IU/Kg/hour infusion) to keep the APTT at 2.5 times of the control). Thereafter, an anticoagulant (acenocoumarin) was prescribed to maintain INR at 2-3. The patients with seizures received levetiracetam with or without clobazam. Status epilepticus was treated with IV lorazepam followed by levetiracetam or lacosamide. Acetazolamide (250mg thrice daily) with or without a bolus dose of 100ml mannitol was prescribed to the patients with clinical features of raised intracranial pressure. The patients not responding to conventional antiedema treatment underwent hemicraniectomy.

2.9. Outcome

The outcome was defined at 1 month using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). In-hospital death was noted. The surviving patients were followed up at 3 months and their outcomes were categorized as good (mRs 0-2) and poor (mRS 3,4,5) [

18].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The normalcy of data was verified by Wilk Shapiro Test. The demographic, clinical, MRI, MRV duration of hospitalization, complications and outcome between the patients with or without MV were compared by Chi-square test if categorical and independent t-test if normally distributed continuous variables. Continuous but skewed data were compared by Mann-Whitney u test. The variables related to death and 3 months of poor outcome were also evaluated by using a parametric and non-parametric test. The effect size of death and poor outcome in the MV group was calculated. Cox regression analysis was done for evaluation of the hazard ratio of MV in determining death and 3-month poor outcome. The statistical analysis was done using SPSS 20 version software. A variable was considered significant if the exact two-tailed P value was ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

Forty-five CVT patients were admitted to ICU. Their age ranged between 16 and 62 years (median 45 years), and 22 (48.9%) were females. They were admitted after a median of 7 days (range 1-62 days) from their initial symptoms. The presenting symptoms were headache in 40(88.9%), vomiting in 28(62.2%), the focal deficit in 33 (73.3%), and seizure in all (status epilepticus in 16, 35.5%). Risk factors could be detected in 40 (89%) patients. Cranial MRI revealed a parenchymal lesion in 39 (86.7%); pale infarctions in 7 and hemorrhagic infarctions in 32 patients. MR venography revealed the involvement of superficial sinuses in 37 (82.2%), deep in 2(4.4%) and both in 6(13.3%) patients.

3.1. Comparison of MV and Non-MV Patients

18 out of 45 (40%) CVT patients in ICU required MV within 1-3 days of hospitalization. The reason for intubation was raised intracranial pressure in all and 8 patients also had status epilepticus.

3.2. Comparison of Clinical Parameters

The clinical variables including age, gender, and duration of illness, status epilepticus, focal motor weakness and GCS score were not significantly different between the MV and non-MV patients (

Table 1)

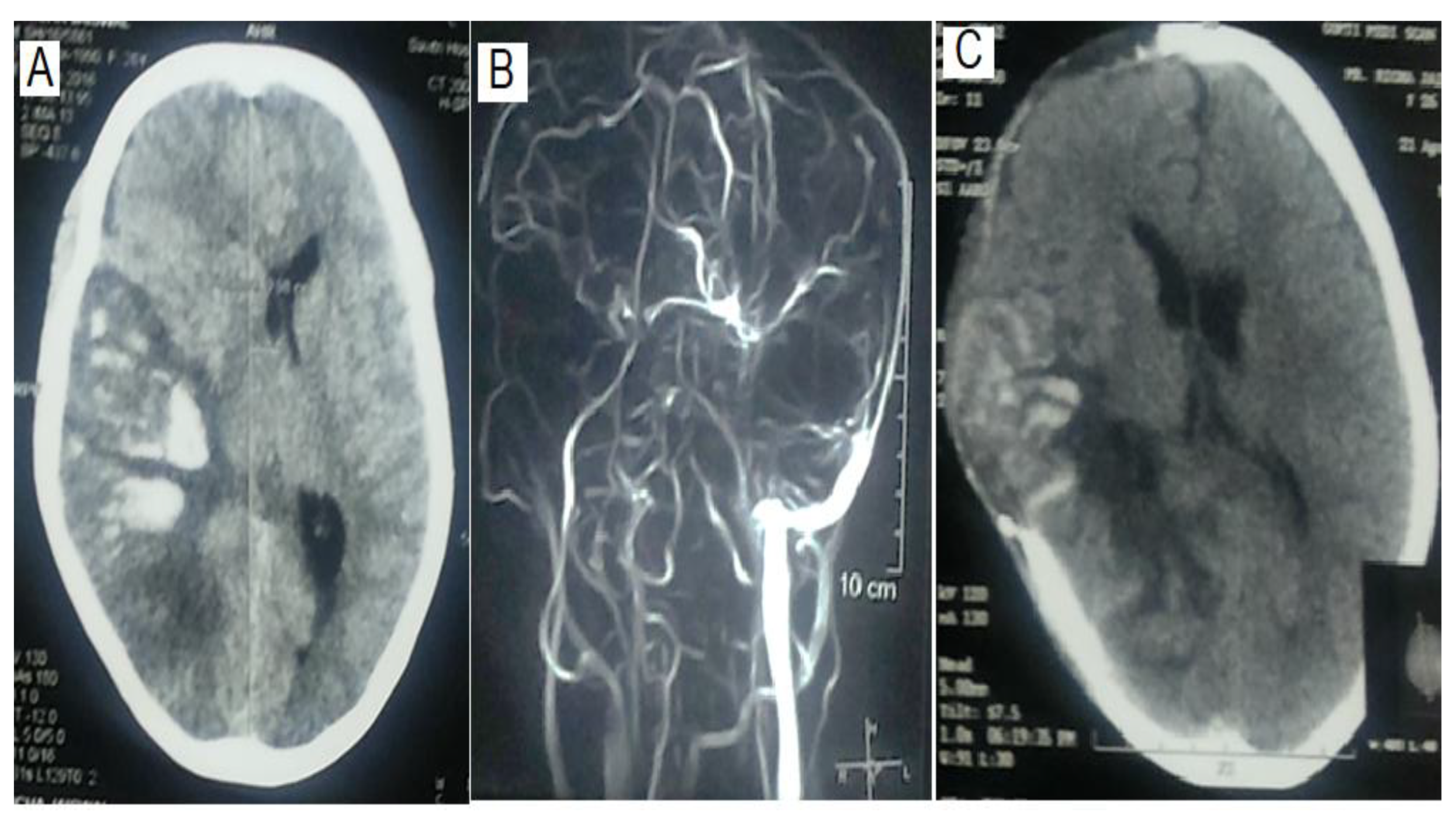

3.3. Comparison of MRV and MRI Findings

The location and extent of thrombosis did not determine the requirement of MV. Both MV and Non-MV groups had comparable numbers of sinus thrombosis (1.33±0.48 vs 1.26± 0.45; P=0.60). Superior sagittal sinus was the commonest site of thrombosis (n=31, 68.9%) followed by transverse (n=29, 64.4%) and sigmoid (n=19, 42.2%), which were also not different in MV and non-MV groups (

Table 2,

Figure 1). The presence of a parenchymal lesion (16 Vs 23; P = 1.00) and frequency of hemorrhagic (15 Vs 17) and pale infarctions (1 Vs 6) were also comparable between MV and non-MV patients (P = 0.21).

3.4. Comparison of Risk Factors

Protein C deficiency was more frequent in the MV group (46% Vs 11.8%; P = 0.04] whereas the frequency of remaining risk factors was insignificant between the groups. The number of risk factors in each patient ranged from none to 5, and 10 patients had more than 2 risk factors. The number of risk factors was insignificantly higher in the non-MV group (1.25± 0.58 Vs 1.67 ± 6.76; p=0.06). The details are presented in

Table 1.

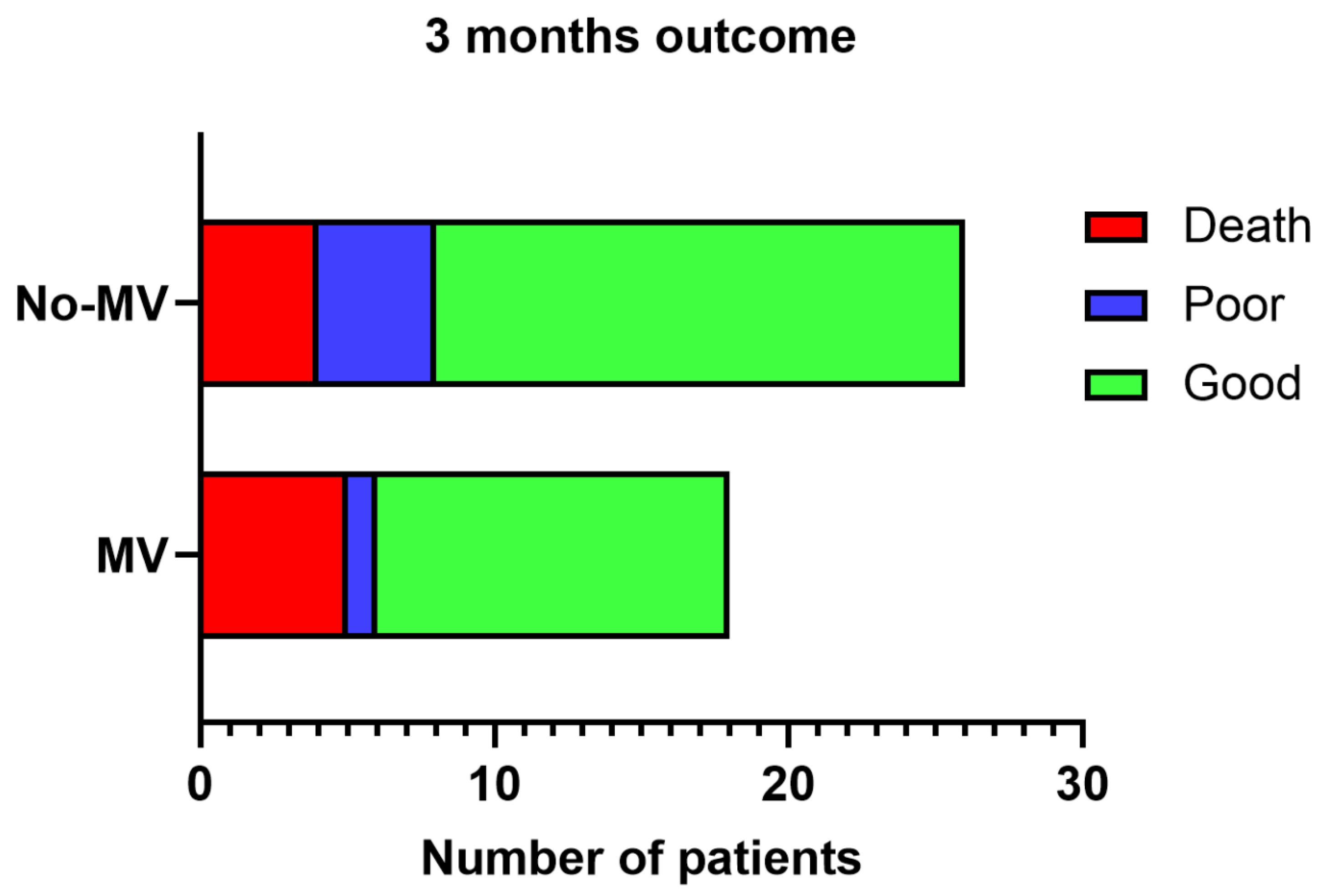

3.5. Outcome

Nine (20%) patients died in the hospital; the MV group had an insignificantly higher frequency of deaths [n=5, (27.8%)] compared to the non-MV [n=4 (14.8%); P=0.45] group. The cause of death was intracranial pressure leading to trans-tentorial herniation. Two of these patients had decompressive surgery, one died and the other survived. The effect size of death in the MV group was 2.2 times as compared to the on-MV group. At 3 months, one patient in the non-MV group lost to follow-up. 30 patients had a good outcome and 5 had poor outcome, which was not significantly different between the MV and non-MV groups (= 0.63;

Figure 2).

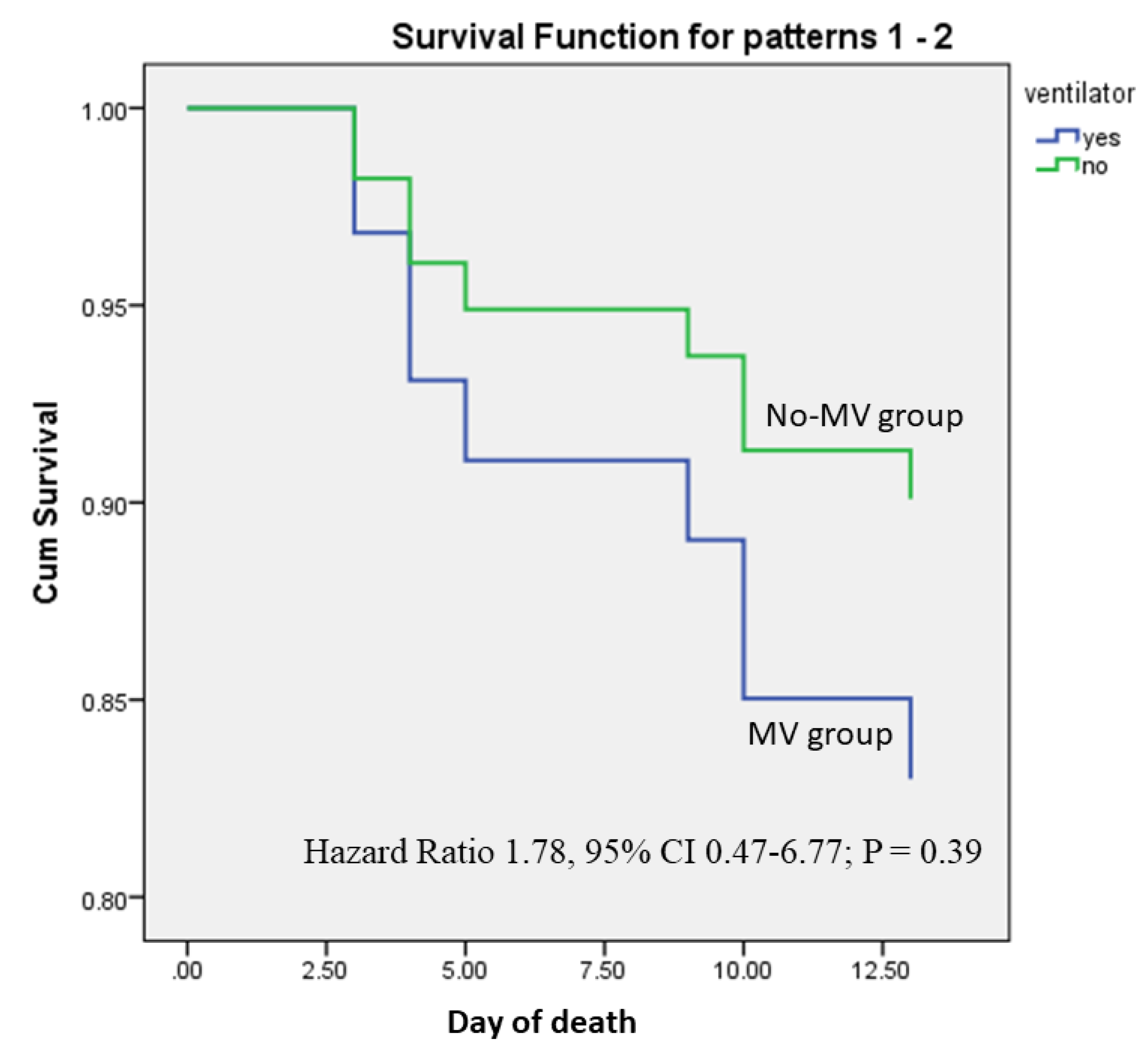

3.6. Predictors of Death

On univariate analysis, the duration of illness was shorter (6.44 ± 5.4 3 days Vs 12.72 ± 14.15 days; P = 0.04) and GCS score was lower (6.89

+ 2.62 vs 9.31

+ 2.95; P = 0.03) in MV compared to non-MV group. The other clinical, MRI, MRV, and risk factors were not associated with death (

Table 3). On Cox regression analysis, the GCS score was independently associated with death (Hazard Ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.59-0.96; P = 0.02) after adjustment of MV and illness duration. The hazard ratio of MV was not significantly related to death (Hazard ratio 1.78, 95% CI 0.47-6.77; P = 0.39;

Figure 3). Admission GCS score (Odds Ratio 0.68; 95% CI 0.51- 0.92; P = 0.02) also predicted poor outcome at 3 months on multivariate analysis. Requirement of MV (OR 1.41; 95% CI 0.24-8.33; P =0.70) however did not predict poor outcome at 3 months after adjustment of the duration of illness, focal motor deficit, status epilepticus, and GCS score.

The duration of MV ranged between 1 and 15 (median 6.5) days. None needed tracheostomy. One patient each developed ventilator-associated pneumonia and septicemia in the MV group and 2 patients developed septicemia in the non-MV group.

4. Discussion

Forty percent of CVT patients admitted to ICU required MV for a median 6 days period. None of the clinical, risk factors, MRI, and MRV changes was related to MV requirement. 20% of patients died and 13.9% had poor recovery at 3 months. The effect size of death was 2.2 in the MV group compared non-MV group, although there was no statistical difference in death and poor outcome between the two groups. The GCS score independently correlated with death and poor outcome at 3 months. There is only one previous study by Soyer et al. on the outcome of CVT patients admitted to ICU. In that study, 37 out of 41 (90%) patients required MV; 10 (27%) patients died and 27 surviving patients improved to an mRS score of 2-4 at 3 months. A focal deficit, type and location of stroke were not associated with death, but raised intracranial pressure was associated with death [

16]. Large population-based studies have reported the requirement of MV in 10-15% of patients with acute stroke; 2.9%-30% of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracerebral hemorrhage, and 8% of patients with ischemic stroke [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The requirement of MV in a cohort of CVT was 13.6% with an overall death in 2% [

21]. The mortality in CVT ranges between 3.4% and 9.9% [

13,

15,

22]. In the present study, the in-hospital mortality rate (20%) was similar to that reported by Soyer et al. This is much lower than other types of strokes in which the in-hospital mortality ranges between 53% and 57% [

3,

4,

5], and one-year mortality ranges between 60% and 92% [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. None of the CVT patients died after discharge in our study. The surviving patients progressively improved, with 87.5% of patients having a good recovery at 3 months (mRS

<2).

The predictors of death in ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are age, comorbidities, GCS score, NIHSS score, size of the stroke, midline shift, herniation, and raised intracranial pressure [

23,

24]. In the present study, a shorter duration of illness and a lower GCS score were associated with death on univariate analysis. However, in multivariable analysis, the GCS score only predicted death and poor outcome at 3 months. In the International

Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis, 624 adult patients with CVT were followed up for a median of 16 months, of whom 8.3% of patients died and 81.6% had a good recovery (mRS

< 2). On multivariate analysis, the predictors of death or dependence were age >37 years, male sex, coma, mental status disorder, hemorrhage on admission CT scan, thrombosis of the deep cerebral venous system, central nervous system infection, and cancer [

13]. In our earlier report, none of the clinical, risk factors, MRI, and MRV changes were related to death and poor outcome [

22]. The extent of thrombosis as assessed by CVST score and the number of parenchymal lesions were also not related to death and 6-months outcome [

20]. A similar observation has also been reported by others [

25,

26]. The mortality predictors in these studies however are unlikely to reflect the result of the present study, because the present cohort included ICU admitted CVT patients only.

Mechanical ventilation did not come out as an independent predictor of death and poor outcome at 3 months in our study. In a study on 31,300 ischemic strokes, the requirement of MV had a hazard ratio of 5.6 for 30 days of mortality [

27], Death in MV patients depends on the reason for intubation and intubation due to respiratory failure and coma had a higher mortality than those requiring intubation due to seizures [

28]. In the present study, 88.9% had seizures and raised intracranial pressure, and intubation was done due to alteration in ABG. The proportion of SE patients was comparable between MV and non-MV group as well as in death and survivor groups.

In a study, the death and disability of CVT patients were not significantly different between SE, self-limiting seizure, and no-seizure groups. At 6 months, 84% of patients with SE, 92.3% with self-limiting seizure, and 94.8% of in the no-seizure group had a good recovery [

20]

. The lower mortality and a better long-term outcome of CVT patients may be due to venous congestion rather than a lack of blood flow as in thrombotic stroke. Both ischemic stroke and CVT may have recanalization of blood vessels [

14,

29]. In a meta-analysis including 694 patients, repeat MRV after a variable time of the event revealed recanalization in 85% of patients [

29]. Complete resolution of the parenchymal lesion at follow-up has also been reported in 13.2% of patients, and they recovered without sequalae [

30]. In the present study, pneumonia and septicemia occurred in very few patients which were comparable in MV and non-MV groups.

5. Limitation

This is a retrospective single-center study carried out in a tertiary care centre. Cerebral venous thrombosis is a rare form of stroke like illness; hence a multicenter prospective study is desirable.

6. Conclusion

Mechanical ventilation is required in 40% of ICU admitted CVT patients. The overall mortality of CVT patients requiring ICU is 20%, and MV is not an independent predictor of death and poor outcome.

Author’s contribution

Jayantee Kalita: Concept, patient management, analyzing and writing the manuscript; Nagendra B Gutti: Data collection and data curation; Prakash C Pandey: Data collection and data curation; Kuntal K Das: Surgical investigation and patient management; Sunil Kumar: Radiological Analysis; Varun K Singh: Data collection and data curation.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Ms. Anam Siddiqui for secretarial help.

Ethical Approval

The study was ethically approved by the Institute Ethics Committee approved the ethical permission (PGI/BE/774).

Informed consent form

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Statement

Data will be available on the reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Montmollin, E. , Terzi, N., Dupuis, C., Garrouste-Orgeas, M., da Silva, D., Darmon, M., Laurent, V., Thiéry, G., Oziel, J., Marcotte, G., Gainnier, M., Siami, S., Sztrymf, B., Adrie, C., Reignier, J., Ruckly, S., Sonneville, R., Timsit, J. F., & OUTCOMEREA Study Group One-year survival in acute stroke patients requiring mechanical ventilation: a multicenter cohort study. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, S.; Mayer, S.A.; Fink, M.E.; Lord, A.S.; Rosengart, A.; Mangat, H.S.; Segal, A.Z.; Claassen, J.; Kamel, H. Mechanical Ventilation for Acute Stroke: A Multi-state Population-Based Study. Neurocritical Care 2015, 23, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, P. , Beasley, R. , Bailey, M., Bellomo, R., Eastwood, G. M., Nichol, A., Pilcher, D. V., Yunos, N. M., Egi, M., Hart, G. K., Reade, M. C., Cooper, D. J., & Study of Oxygen in Critical Care (SOCC) Group. The association between early arterial oxygenation and mortality in ventilated patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Critical care and resuscitation : journal of the Australas. Acad. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 14, 14–9. [Google Scholar]

- Popat, C.; Ruthirago, D.; Shehabeldin, M.; Yang, S.; Nugent, K. Outcomes in Patients With Acute Stroke Requiring Mechanical Ventilation: Predictors of Mortality and Successful Extubation. The American journal of the medical sciences 2018, 356, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schielke, E.; Busch, M.A.; Hildenhagen, T.; Holtkamp, M.; Küchler, I.; Harms, L.; Masuhr, F. Functional, cognitive and emotional long-term outcome of patients with ischemic stroke requiring mechanical ventilation. J. Neurol. 2005, 252, 648–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.; Mendoza, G.; De Georgia, M.; Schellinger, P.; Holle, R.; Hacke, W. Prognosis of stroke patients requiring mechanical ventilation in a neurological critical care unit. Stroke. 1997, 28, 711–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoli, F.; De Jonghe, B.; Hayon, J.; Tran, B.; Piperaud, M.; Merrer, J.; Outin, H. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute ischemic stroke: survival and outcome at one year. Intensive Care Med. 2001, 27, 1141–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milhaud, D. , Popp, J. , Thouvenot, E., Heroum, C., & Bonafé, A. Mechanical ventilation in ischemic stroke. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases: the official journal of Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2004, 13, 183–8. [Google Scholar]

- Burtin, P.; Bollaert, P.E.; Feldmann, L.; Nace, L.; Lelarge, P.; Bauer, P.; Larcan, A. Prognosis of stroke patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 1994, 20, 32–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saposnik, G. , Barinagarrementeria, F., Brown, R. D., Jr, Bushnell, C. D., Cucchiara, B., Cushman, M., deVeber, G., Ferro, J. M., Tsai, F. Y., & American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011, 42, 1158–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, A.I. A Classification Scheme for Assessing Recanalization and Collateral Formation following Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. J. Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2010, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferro, J. M.; Canhão, P.; Stam, J.; Bousser, M.G.; Barinagarrementeria, F. ISCVT Investigators Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke 2004, 35, 664–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Singh, R.K. Do the Risk Factors Determine the Severity and Outcome of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis? Transl. Stroke Res. 2018, 9, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triquenot Bagan, A.; Crassard, I.; Drouet, L.; Barbieux-Guillot, M.; Marlu, R.; Robinet-Borgomino, E.; Morange, P.E.; Wolff, V.; Grunebaum, L.; Klapczynski, F.; André-Kerneis, E.; Pico, F.; Martin-Bastenaire, B.; Ellie, E.; Menard, F.; Rouanet, F.; Freyburger, G.; Godenèche, G.; Allano, H.A.; Moulin, T.; … Le Cam Duchez, V. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: Clinical, Radiological, Biological, and Etiological Characteristics of a French Prospective Cohort (FPCCVT)-Comparison With ISCVT Cohort. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 753110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyer, B.; Rusca, M.; Lukaszewicz, A.C.; Crassard, I.; Guichard, J.P.; Bresson, D.; Mateo, J.; Payen, D. Outcome of a cohort of severe cerebral venous thrombosis in intensive care. Ann. Intensive Care 2016, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, J.; Enblad, P. Neurointensive care of patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and intracerebral haemorrhage. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 2018, 58, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Singh, V.K.; Jain, N.; Misra, U.K.; Kumar, S. Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Score and its Correlation with Clinical and MRI Findings. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2019, 28, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Singh, V.K.; Dubey, D. Predictors and outcome of status epilepticus in cerebral venous thrombosis. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalita, J.; Ranjan, A.; Misra, U.K. Outcome of Guillain-Barre syndrome patients with respiratory paralysis. QJM: monthly journal of the Association of Physicians, 2016, 109, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- \Ruiz-Sandoval, J. L. , Chiquete, E. , Bañuelos-Becerra, L. J., Torres-Anguiano, C., González-Padilla, C., Arauz, A., León-Jiménez, C., Murillo-Bonilla, L. M., Villarreal-Careaga, J., Barinagarrementería, F., Cantú-Brito, C., & RENAMEVASC investigators Cerebral venous thrombosis in a Mexican multicenter registry of acute cerebrovascular disease: the RENAMEVASC study. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2012, 21, 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kalita, J.; Singh, V.K.; Misra, U.K. A study of hyperhomocysteinemia in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 152, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdo, R.; Abboud, H.; Salameh, P.; El Hajj, T.; Hosseini, H. Mortality and Predictors of Death Poststroke: Data from a Multicenter Prospective Cohort of Lebanese Stroke Patients. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2019, 28, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénon, H.; Godefroy, O.; Leys, D.; Mounier-Vehier, F.; Lucas, C.; Rondepierre, P.; Duhamel, A.; Pruvo, J.P. Early predictors of death and disability after acute cerebral ischemic event. Stroke. 1995, 26, 392–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, E.; Trittmacher, S.; Rahimi, A.; Gerriets, T.; Röttger, C.; Siekmann, R.; Kaps, M. Influence of recanalization on outcome in dural sinus thrombosis: a prospective study. Stroke 2004, 35, 544–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.W.; Studer, A.; Arnold, M.; Georgiadis, D. Recanalisation of cerebral venous thrombosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 459–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestanian, E.; Liou, J.I.; Smith, M.A. Long-term survival in older critically ill patients with acute ischemic stroke. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 3107–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyfroidt, G.; Bollaert, P.E.; Marik, P.E. Acute ischemic stroke in the ICU: to admit or not to admit? Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 749–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar de Sousa, D.; Lucas Neto, L.; Canhão, P.; Ferro, J.M. Recanalization in Cereb. Venous Thrombosis. Stroke 2018, 49, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Jain, N.; Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Kumar, S. Significance of recanalization of sinuses and resolution of parenchymal lesion in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Journal of clinical neuroscience: official journal of the Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 2020, 77, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).