1. Introduction

Carotenoids and lipids are two important classes of bioactive metabolites that play essential roles in both cellular physiology and human health. Carotenoids are naturally occurring pigments synthesized by plants, algae, fungi, and numerous microorganisms [

1]. These compounds are responsible for the yellow, orange, and red hues in biological systems and are well known for their potent antioxidant and health-promoting properties [

2]. Among microbial carotenoids, torularhodin—a linear, carboxylated carotenoid with an extended conjugated polyene chain—has recently drawn significant attention for its exceptional antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotective activities [

3,

4,

5]. Compared to β-carotene, torularhodin displays stronger singlet oxygen quenching capacity, greater oxidative stability, and enhanced biological activity, which together underscore its potential as a multifunctional natural compound for food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical applications [

6,

7,

8].

In parallel, microbial lipids—commonly referred to as single-cell oils (SCOs)—have emerged as sustainable alternatives to plant- or animal-derived oils [

9,

10]. These lipids, mainly composed of triacylglycerols enriched with saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, are valuable feedstocks for biofuels, functional foods, and health products [

11,

12]. Importantly, lipids enhance the solubility and stability of hydrophobic antioxidants such as torularhodin, offering synergistic potential in formulation science [

13,

14]. The co-production of torularhodin and lipids within a single microbial platform presents clear bioprocessing advantages—enhanced productivity, simplified downstream extraction, and improved cost-effectiveness—thus aligning well with the goals of the circular bioeconomy [

15,

16].

Traditional sources of carotenoids and lipids rely heavily on plant extraction or chemical synthesis, but these approaches are hampered by long growth cycles, seasonal and land-use constraints, and the need for hazardous reagents [

17]. In contrast, microbial fermentation offers a more sustainable, scalable and controllable route for producing natural bioactives with high purity and reproducibility and allows targeted enhancement via metabolic or process engineering [

18,

19]. Among microbial sources, yeasts of the genus

Rhodotorula are particularly noteworthy for their ability to synthesize both carotenoids—primarily torularhodin, torulene, and β-carotene—and intracellular lipids under stress or nutrient-limited conditions [

20,

21]. These traits make them promising microbial chassis for biotechnological applications across the food, healthcare, and cosmetic industries [

22]. However, the diversity within this genus remains underexplored. While

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa,

R. glutinis, and

R. toruloides have been extensively studied [

18,

23,

24],

Rhodotorula evergladensis is a lesser-known and previously uncharacterized species with unknown biosynthetic potential. To our knowledge, there have been no systematic studies investigating the metabolic, antioxidant, or anti-inflammatory properties of

R. evergladensis. Exploring such non-model species may reveal unique biosynthetic pathways for high-value carotenoids like torularhodin and enrich the microbial platforms available for sustainable production.

In this study, we report the isolation and functional characterization of a novel oleaginous yeast strain, Rhodotorula evergladensis CXCN-6, from the surface of Nymphaea ‘Gorgeous Purple’. The strain exhibited intense reddish-orange pigmentation due to intracellular torularhodin accumulation, along with substantial lipid storage. Through combined spectrophotometric, chromatographic, and functional assays, we demonstrate that CXCN-6 co-produces torularhodin and unsaturated lipids with strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. These findings not only uncover the functional potential of R. evergladensis but also establish it as a promising microbial chassis for the sustainable production of natural multifunctional ingredients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Strain Isolation

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 strain was isolated from the Nymphaea ‘Gorgeous Purple’ of Yunnan-Kweichow Plateau, Kunming, China. The strain collection number of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 is recorded in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (Beijing, China) as CGMCC 7.610. Nymphaea samples were collected in sterile tube. Samples were plated in yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) medium (Yeast extract 10 g/L, Peptone 20 g/L, Dextrose 20 g/L, Agar 15 g/L) and incubated at 28 °C for 2 days. The most reddish-orange colony was purified by five streaking rounds on fresh YPD medium and incubated at 28 °C for 48 h to obtain pure culture. Obtained strains were grown in a YPD medium and incubated at 28 °C for 48 h on rotary shaker at 150 rpm. The purified strains were preserved in 20% glycerol (w/v) at -80 °C for further use.

2.2. Strain Identification

The selected microorganism was identified based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal RNA gene. Genomic DNA was extracted using the TIANamp Yeast DNA Kit Gene (Tiangen Biotech (Bejing) CO., LTD, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The ITS region was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using universal primers ITS1 (5′- TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′- TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′). PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 50 μL using a Bio-Rad T100 thermo-cycler, containing 2 μL of genomic DNA, 25 μL 2x T8 High-Fidelity Master Mix, 2 uL of 10 uM each primer, 19 uL of sterile ultrapure water. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55 °C for 10 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were verified by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and subsequently purified and sequenced by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The obtained ITS rRNA gene sequence (542 bp) was analyzed using the BLASTn algorithm against nucleotide sequences available in the NCBI GenBank and EMBL databases to determine the closest phylogenetic relatives.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

The ITS sequence of

Rhodotorula sp. CXCN-6 was aligned with reference sequences of closely related

Rhodotorula species retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database. Multiple sequence alignment was conducted using ClustalW implemented in MEGA 7 software [

25]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, with 1,000 bootstrap replications to assess the statistical support of each clade. Evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter model. The resulting phylogenetic tree was visualized and annotated in iTOL v6 [

26]. The CXCN-6 isolate clustered closely with

Rhodotorula evergladensis reference sequences (GenBank accession no. FJ008048.1), confirming its taxonomic identification as

R. evergladensis CXCN-6.

2.4. Culture Medium and Extract Preparation

R. evergladensis was grown in the liquid medium (glucose 20 g/L, yeast extract 10 g/L, and peptone 20 g/L, pH 6.0). The growth of seed culture was monitored according to the optical density at 600 nm. When the seed culture reached the stationary phase of growth, the seed culture was inoculated into 3 L medium in a 5 L fermenter at a ratio of 5% and incubated for 96 h at 28 °C, 600 rpm 1.0 vvm, pH 6.0. The 500 mL of high C/N ratio concentrated feed was prepared. After 24 h cultivation, feeding was started. The yeast cells were harvested every 24 h by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The cells were washed twice with the same volume of sterile distilled water, then freeze-dried and weighted for the determination of dry cell weight (DCW).

The freeze-dried cells (100 mg) were hydrolyzed by 1.5 mL of 1 M HCl at 100 °C for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 3 min, then were washed with sterile distilled water. The hydrolyzed cells were gradually mixed with 1 mL acetone, then 0.5 mL ethyl acetate and 0.5 mL petroleum ether with bath ultrasonication shortly. Finally, the mixture was washed with 5 mL sterile distilled water, then centrifuged 4,000 rpm 5 min, and the upper reddish color phase which contains carotenoids and other lipophilic compounds was collected; this extract process was repeated until a colorless pellet was obtained. The collected solvent mixture was dried in a rotary vacuum evaporator, then dissolved in 2 mL hexane [

27]. The dissolved extract sample was centrifuged, filtrated through a 0.45 µm microfilter and stored at -80 °C for further analysis.

2.5. Carotenoid Analysis of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extract

The chromatographic analysis of the carotenoids present in the extract was performed in a reversed-phase High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1260 series, USA) with a DAD detector using a column (C18, 5 µm, 250 × 4.6 mm, Agilent, Cat# 880975-902). The mobile phases were acetonitrile and H

2O (9:1, v/v) as eluent A, and pure ethyl acetate as eluent B. The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–5 min 100% A; 5–15 min 100% B; 15–30 min 100% B, according to the reported method with slight modification [

27]. The column temperature was kept at 30 °C, and the injection volume was 20 µL. Chromatograms were recorded in the range of 490 nm and the OpenLab CDS program was used for data processing. The compounds were identified on the basis of their retention time and UV–Vis spectra compared to torularhodin standard (Carotenature, Switzerland) and β-carotene (CFDA, China, Cat# 100445). The content of torularhodin and β-carotene in the extract sample was calculated by standard curve of HPLC with different concentration of torularhodin and β-carotene standard.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis was performed to further confirm the molecular identity of the carotenoids detected in the HPLC chromatograms. The analysis was conducted using an Agilent 6460 Triple Quadrupole LC–MS system (Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source operated in the positive ionization mode. Chromatographic separation was achieved on the same C18 column under identical gradient conditions as described for HPLC. The APCI parameters were optimized as follows: vaporizer temperature 400 °C, drying gas (N2) temperature 350 °C and flow rate 5 L min⁻¹, corona discharge current 4 µA, nebulizer pressure 40 psi, and capillary voltage 3500 V. The MS data were acquired in full-scan mode within the mass range of m/z 300–700, followed by product ion scan for structural confirmation.

2.6. Lipid Analysis of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extract

The content of total lipids in the extract was calculated using the sulfo-phospho vanillin (SPV) method [

28]. Briefly, 10 µL of extract sample was put into 20 mL glass bottle and dried at room temperature for 20 min to evaporate the solvent. Subsequently, 100 µL of distilled water was added to the extract sample, 2 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid was added to the sample slowly and was heated for 10 min at 100 °C and was cooled for 5 min in ice bath. 5 mL of freshly prepared phospho-vanillin reagent was then added, and the sample was incubated for 15 min at 37 °C incubator shaker at 200 rpm. The optical density (OD) was measured at 530 nm to quantify the lipid content within the sample. The calibration was carried out by treating different concentrations of olive oil with the same method as the sample. Fatty acids were quantified using a QTRAP 6500+ mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) coupled to an ACQUITY premier CSH (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed on an ACQUITY premier CSH column (C18, 1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm, Waters). Briefly, the solvent of 1 mL sample was evaporated at room temperature completely and reconstituted in 150 µL of eluent B. After vortexing and centrifuged, the supernatant was used for injection. The mobile phases consisted of (A) acetonitrile:water (6:4, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid; (B) isopropanol:acetonitrile (9:1, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid. The flow rate was set to 0.3 mL / min, and the injection volume was 2 µL. The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–2.5 min 95-70% A; 2.5–10.5 min 65% A; 10.5–12 min 50% A; 12-15 min 35% A; 15–18 min 1% A; 18-20 min 1% A; 20-20.5 min 1-95% A; 20.5-24 min 95% A. Mass spectrometric detection was carried out using QTRAP 6500+ ESI (-). Source parameters were as follows: source temperature, 550 °C; ion source gas 1, 55; gas 2, 50; curtain gas, 30; and ion spray voltage floating, 4500 V. Data acquisition was performed in scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The calibration was carried out by treating different concentrations of various fatty acid standards. Data acquisition and processing were performed using MultiQuant software (SCIEX).

2.8. Antioxidant Activity Assays

The antioxidant potential of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extracts was evaluated using DPPH, ABTS radical scavenging assays, and an intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay.

2.8.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined following the method of Blois (1958) with minor modifications [

29]. Briefly, 1 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution in ethanol was mixed with 1 mL of CXCN-6 extract at various concentrations (0.03–3.0 mg/mL). The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min, and absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo, USA). Vitamin C (1mg/mL) was used as positive controls. The radical scavenging activity was expressed as the percentage decrease in absorbance compared with the control (without extract).

2.8.2. ABTS Radical Cation Scavenging Activity

ABTS radical scavenging capacity was measured according to the method of Re et al. (1999) [

30]. ABTS•⁺ radicals were generated by mixing 7 mM ABTS solution with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate and incubating the mixture in the dark for 16 h at room temperature. The resulting ABTS•⁺ solution was diluted with ethanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Then, 1 mL of the ABTS•⁺ solution was mixed with 100 μL of CXCN-6 extract at different concentrations (0.3–3.0 mg/mL) and incubated for 6 min in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 734 nm, and scavenging activity was expressed as the percentage inhibition relative to the control. Vitamin C (1mg/mL) was used as positive controls.

2.8.3. Intracellular ROS Assay

Intracellular ROS scavenging activity was assessed using the DCF-DA fluorescent probe in UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells. Human keratinocytes (HaCaT) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO₂. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (1 × 10⁴ cells/well) and pre-treated with CXCN-6 extract (5–100 μg/mL) for 24 h. After washing with PBS, the cells were exposed to UVA irradiation (9 J/cm²) to induce oxidative stress, followed by incubation with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min in the dark. Fluorescence intensity of the oxidized product DCF, representing intracellular ROS levels, was measured using a microplate reader (excitation at 485 nm and emission at 528 nm). In parallel, fluorescent images were captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse, Japan) to visualize intracellular ROS generation. The ROS inhibition rate was calculated relative to untreated and UVA-only control groups.

2.9. Anti-inflammatory Activity Assay

The anti-inflammatory potential of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extract was evaluated using a murine macrophage RAW264.7 cell model. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO₂ incubator. For the assay, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 2 × 10⁵ cells per well and pretreated with different concentrations of CXCN-6 extract (25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) for 2 h before stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 24 h. Vitamin C (50 μM) was used as a positive control. Following incubation, culture supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis. The levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were determined using QuantiCyto® ELISA kits (Proteintech, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermos, USA). Cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay to exclude cytotoxic effects, and all data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from triplicate experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Identification of R. evergladensis CXCN-6

A reddish-orange yeast strain, designated

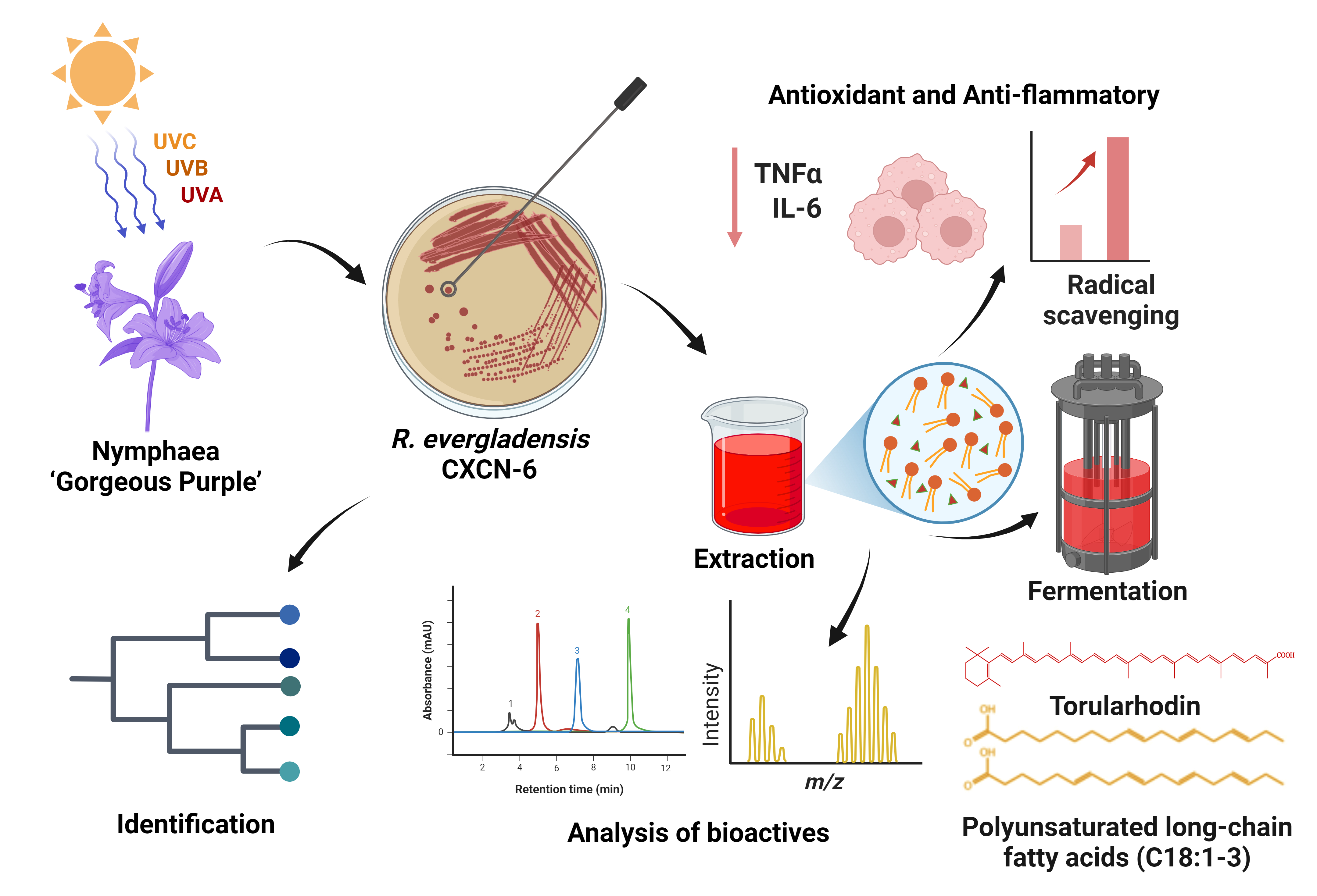

R. evergladensis CXCN-6, was isolated from the surface of the aquatic plant Nymphaea “Gorgeous Purple,” collected from Kunming, Yunnan Province, China—a region characterized by strong ultraviolet (UV) radiation and high solar intensity (

Figure 1). The sampling environment was selected due to its potential to harbor microorganisms adapted to oxidative stress, which may exhibit enhanced carotenoid biosynthesis. Primary isolation was performed on YPD plate after enrichment in liquid YPD medium at 28 °C for 24 h with gentle shaking (150 rpm). After streaking onto YPD plates and incubation at 28 °C for 48 h, colonies of CXCN-6 appeared circular, convex, smooth, and glossy, displaying a distinctive reddish-orange pigmentation indicative of carotenoid accumulation (

Figure 1). The isolate was purified through three successive streaking steps under identical conditions to ensure genetic and phenotypic stability.

For molecular identification of CXCN-6, genomic DNA was extracted. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of ribosomal DNA was amplified using the universal primers ITS1 (5′- TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′- TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′). PCR products (542 bp) were purified and sequenced. BLAST analysis of the ITS sequence revealed ≥ 99% identity with

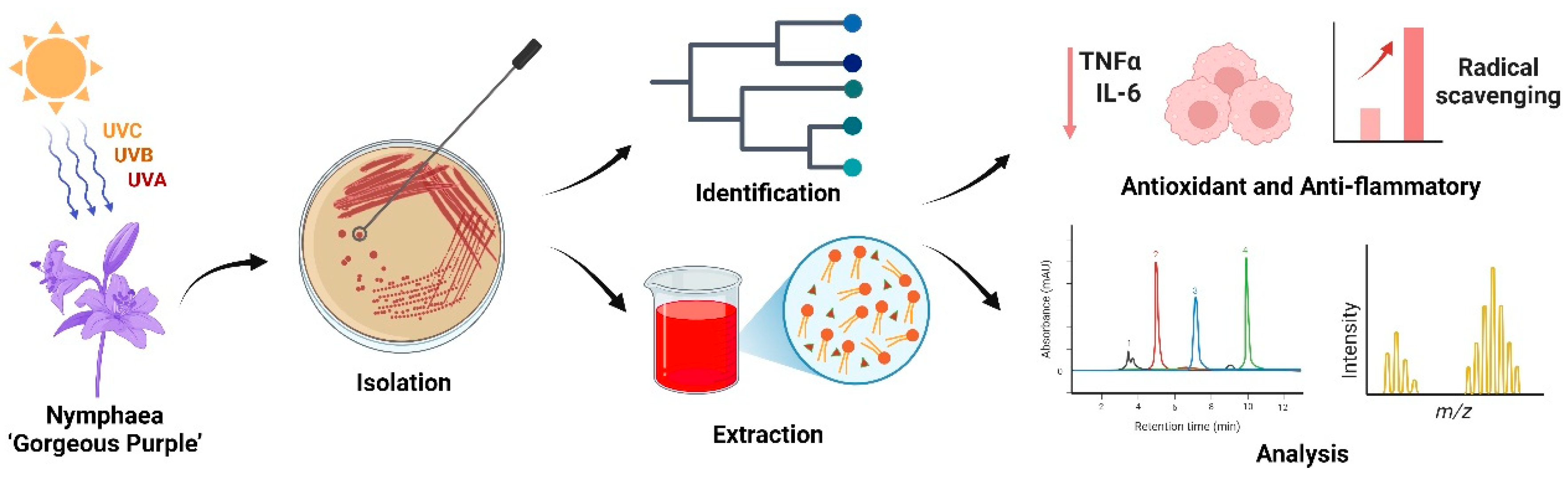

R. evergladensis reference sequences in GenBank (accessions: NR_137709.1). A phylogenetic tree constructed using the neighbor-joining method confirmed that strain CXCN-6 clustered tightly with

R. evergladensis type strains and was distinct from other

Rhodotorula species, including

R. mucilaginosa,

R. glutinis, and

R. minuta (

Figure 2). This confirmed the strain’s identity as

R. evergladensis. To our knowledge,

R. evergladensis remains a relatively uncharacterized yeast species, with scarce reports addressing its metabolic or functional potential. The strain has been deposited in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) under the accession number CGMCC 7.610 for future reference and industrial exploration.

3.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Functional Annotation of R. evergladensis CXCN-6

To comprehensively understand the molecular determinants underlying the unique metabolic plasticity of

R. evergladensis CXCN-6, whole-genome sequencing and functional annotation were performed. Genomic characterization provides fundamental insights into the genetic determinants that enable this strain to simultaneously produce carotenoids and lipids—two biosynthetically demanding secondary metabolites linked to stress adaptation and cellular redox balance [

31]. Understanding its genome organization thus establishes a foundation for exploring metabolic regulation and guiding future strain improvement for industrial applications.

High-quality genomic DNA was sequenced using a hybrid Illumina–Oxford Nanopore platform, ensuring both high accuracy and long-read continuity. The assembled genome comprised approximately 20.72 Mb with a GC content of 62.17%, distributed across 18 scaffolds with an N50 of 1.4 Mb (

Table S1). BUSCO analysis indicated ~90% completeness, confirming high assembly quality suitable for downstream annotation. A total of 6,389 protein-coding genes and 105 tRNA genes were predicted (

Table S2). Functional annotation against KEGG, GO, and COG databases revealed that

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 is enriched in genes related to central carbon metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, and carotenoid formation, suggesting a well-organized metabolic framework supporting dual metabolite synthesis.

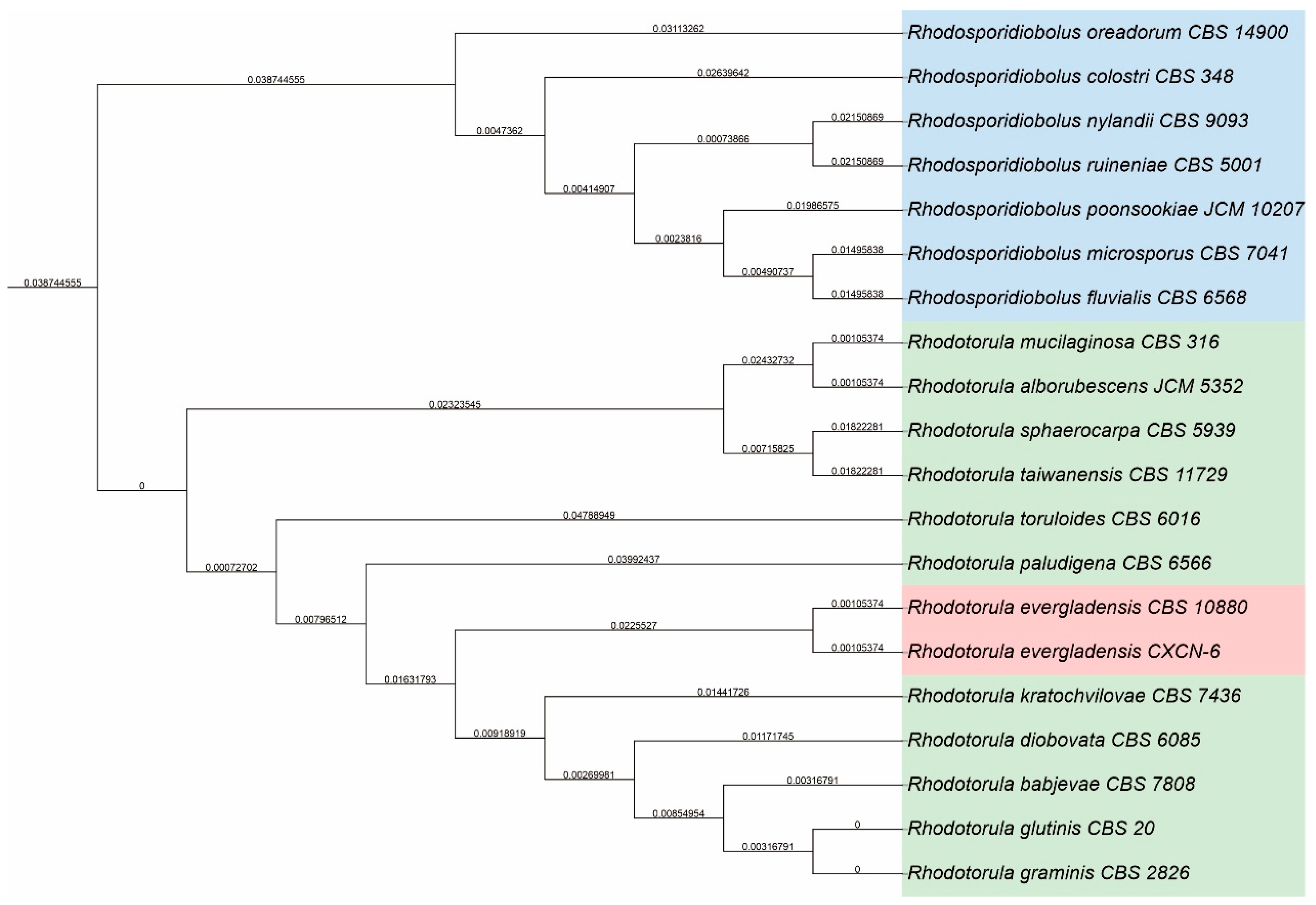

Key genes of the mevalonate (MVA) pathway—such as HMG-CoA reductase, farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase—were identified, providing the precursors for carotenoid biosynthesis. The downstream carotenoid pathway was complete, including

crtB (phytoene synthase),

crtI (phytoene desaturase),

crtY (lycopene cyclase), and

crtA (carotenoid oxygenase), consistent with the observed torularhodin production (

Figure 3). Genes involved in lipid metabolism, including FAS1/FAS2 (fatty acid synthase), ACC1 (acetyl-CoA carboxylase), and multiple desaturases (Δ9, Δ12, Δ15), were also identified, explaining the accumulation of long-chain unsaturated fatty acids (

Figure 3). Moreover, the presence of oxidative stress–related genes, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, supports the coordination between antioxidant defense and carotenoid synthesis. Collectively, these genomic features demonstrate that

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 harbors a complete and well-integrated genetic system for the co-production of carotenoids and lipids, highlighting its potential as a robust and engineerable yeast platform for sustainable biomanufacturing.

3.3. Torularhodin Production and Spectral Characterization in R. evergladensis CXCN-6

The

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 strain exhibited an intense reddish-orange pigmentation in both liquid and solid cultures (

Figure S1), a visual hallmark of

Rhodotorula yeasts that accumulate carotenoids. Pigmentation deepened as cultures entered the stationary phase, suggesting that carotenoid biosynthesis, is growth-associated and stress-responsive. This phenotype was especially pronounced under nutrient-limited conditions, consistent with oxidative-stress–induced upregulation of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways [

22,

32,

33].

CXCN-6 extracts of the intracellular pigments showed a strong absorption maximum at 490 nm (

Figure S2). These spectral features are typical of polyene carotenoids with extended conjugated double-bond systems, confirming the presence of chromophoric molecules such as torularhodin, torulene, and β-carotene. The steady increase in absorption intensity correlated with cell dry weight during culture progression, indicating proportional intracellular accumulation of carotenoids with biomass growth. Quantitative spectrophotometric analysis estimated a total carotenoid content of ~63.56 mg/L, corresponding to ~1.27 mg/g dry cell weight (DCW) under optimized conditions. These levels are comparable to or higher than those reported in

Rhodotorula glutinis and

R. mucilaginosa under similar culture regimes, emphasizing the high pigment productivity of this novel strain [

34].

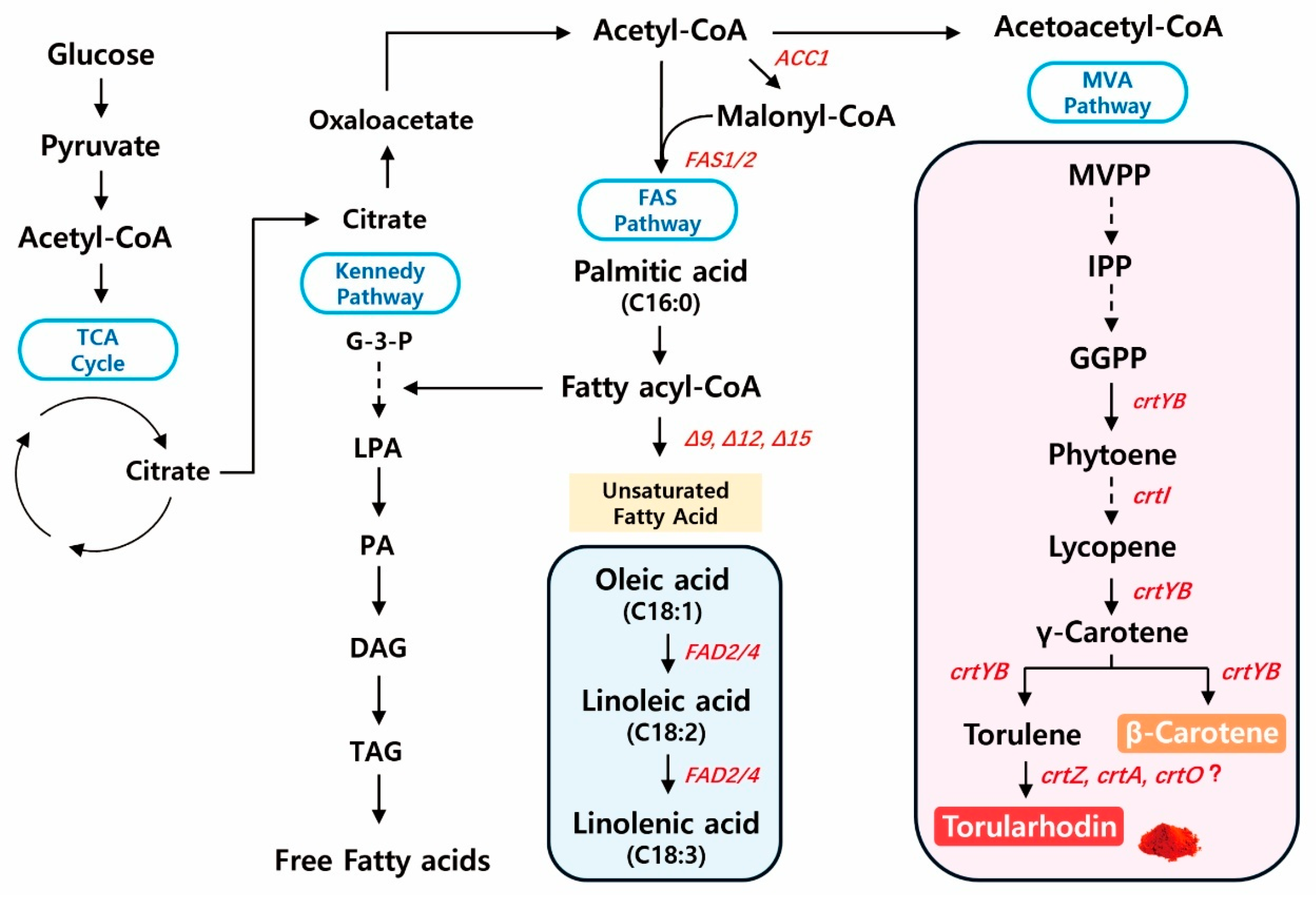

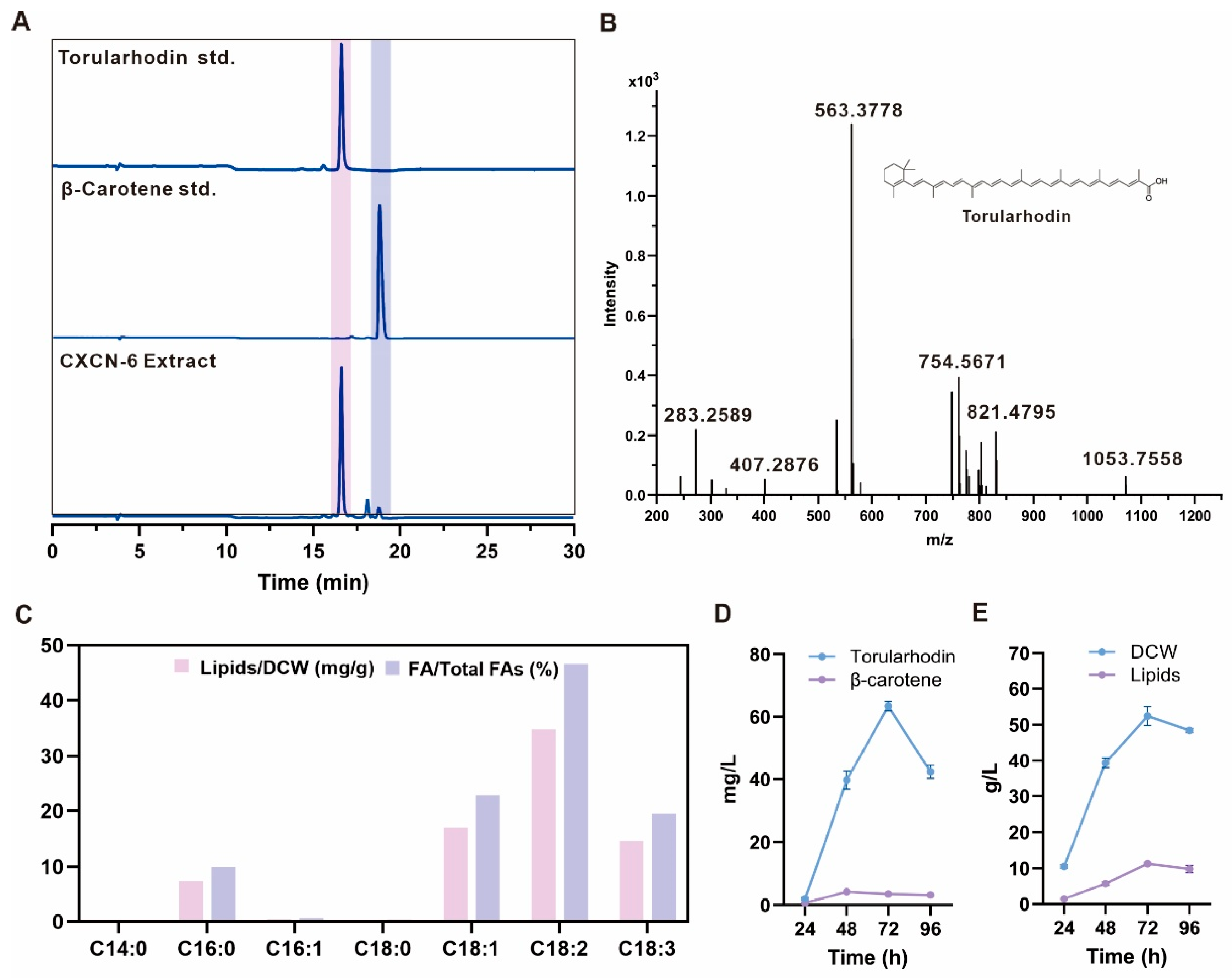

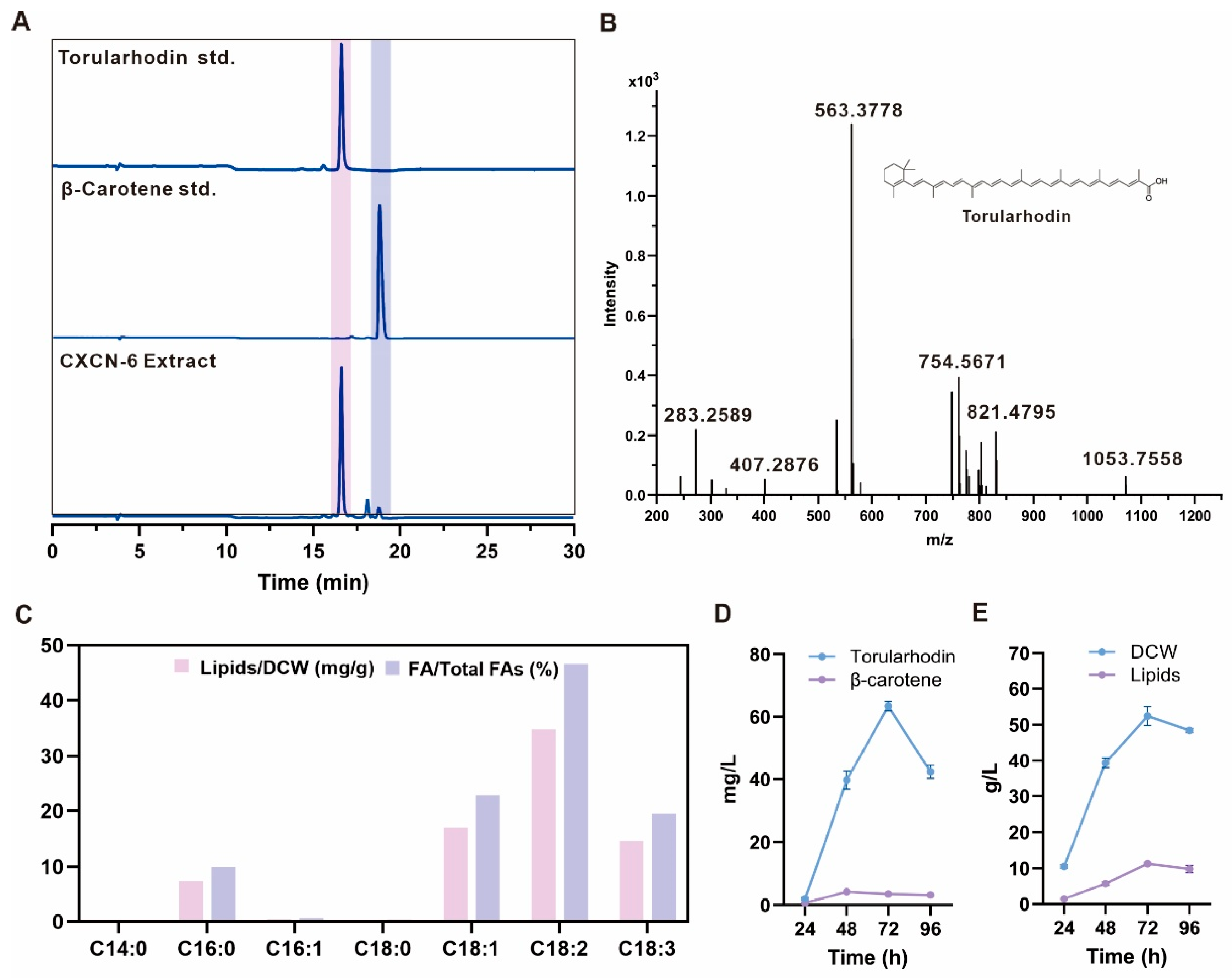

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis using a C18 reverse-phase column (detection at 490 nm) revealed a dominant pigment peak with a retention time identical to the torularhodin standard (

Figure 4A). Two minor peaks, detected at retention times of 18.6 min and 19.5 min, corresponded to β-carotene and torulene, respectively, suggesting their roles as biosynthetic intermediates within the carotenoid pathway (

Figure 4A). Quantitative integration of chromatographic areas indicated that torularhodin accounted for more than 90% of the total carotenoid content, establishing it as the predominant carotenoid pigment synthesized by

R. evergladensis CXCN-6. Further structural verification was achieved through liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis operated in atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI

+) mode. The predominant pigment exhibited a molecular ion peak at m/z 563.4 [M]

+ (

Figure 4B), corresponding to the theoretical molecular weight of torularhodin (C

40H

56O

2, MW = 564.4). This spectral pattern was consistent with previously reported data for torularhodin isolated from

Rhodotorula sp., thereby confirming its structural identity [

22].

3.4. Fatty Acid Profile of R. evergladensis CXCN-6

To further elucidate the metabolic potential of

R. evergladensis CXCN-6, lipid composition was analyzed. Total lipids were extracted for LC–MS analysis [

35]. Chromatographic separation on a reverse-phase C18 column revealed that the lipid fraction was dominated by C18-series fatty acids. The major unsaturated components were linoleic acid (C18:2, 46.6%), oleic acid (C18:1, 22.8%), and α-linolenic acid (C18:3, 19.5%), while palmitic acid (C16:0, 10.0%) represented the main saturated species (

Figure 4C).

This fatty acid profile—rich in polyunsaturated long-chain fatty acids (PUFAs, ~90% of total fatty acids)—is characteristic of stress-tolerant Rhodotorula species and indicates enhanced membrane fluidity and oxidative resilience. The simultaneous accumulation of PUFA-enriched lipids and the potent antioxidant torularhodin underscores the strain’s metabolic synergy and environmental adaptability. These results highlight R. evergladensis CXCN-6 as a metabolically versatile and robust oleaginous yeast suitable for producing nutraceutical, cosmetic, and functional food ingredients.

3.5. Fermentation Performance of R. evergladensis CXCN-6

Fermentation optimization was conducted in a 5-L bioreactor to evaluate production performance under controlled conditions. The defined medium contained 20 g/L glucose, 10 g/L yeast extract, and 20 g/L peptone, with process parameters maintained at 28 °C, 600 rpm, 1 vvm aeration, and pH 6.0 following a high C/N ratio feeding strategy. We first monitored the growth kinetics of CXCN-6 to determine its physiological response during fermentation. The growth curve revealed that biomass accumulation slowed markedly after 72 h, indicating entry into the stationary phase and a potential metabolic shift from primary growth to secondary metabolite biosynthesis (

Figure S3A). To further promote intracellular carotenoid and lipid synthesis, a nutrient-limiting strategy was implemented by terminating the feeding process at 54 h, thereby inducing mild starvation stress known to trigger secondary metabolite accumulation in oleaginous yeasts (

Figure S3B).

Under these optimized conditions, the culture exhibited typical oleaginous yeast kinetics, reaching a maximum dry cell weight (DCW) of 50 g/L at 72 h. The strain produced 63.56 mg/L of torularhodin and 9.83 g/L of total lipids (

Figure 4D,E). On a cell dry weight basis, torularhodin and total lipids reached 1.27 mg/g DCW and 142.6 mg/g DCW, respectively, representing the highest intracellular contents during the fermentation process (

Figure S4). These data demonstrate that nitrogen-limited and oxidative conditions effectively redirected cellular metabolism toward secondary product formation, maximizing the accumulation of both torularhodin and storage lipids.

Compared with the unoptimized shake-flask culture, the total lipid yield increased nearly 13-fold (from 0.733 g/L to 9.83 g/L), while total carotenoid production rose 4.2-fold (from 15.3 mg/L to 63.6 mg/L) (

Table 1). Among the carotenoid components, torularhodin became the predominant pigment, accounting for more than 95% of total carotenoids in the optimized culture, compared with approximately 90% before optimization. In contrast, the yield of β-carotene per dry cell weight (DCW) slightly declined (from 88.9 μg/g DCW to 57.9 μg/g DCW), whereas torularhodin content significantly increased (from 0.77 mg/L to 1.30 mg/L). This inverse trend indicates a metabolic flux shift toward the oxidative branch of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, favoring the conversion of β-carotene and torulene into torularhodin.

Such a shift is likely driven by enhanced activity of carotenoid oxygenases and desaturases under nitrogen-limited and oxidative stress conditions, where reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation acts as a signal to promote carotenoid oxidation. The resulting enrichment of torularhodin not only strengthens the antioxidant capacity of the culture but also reflects a refined stress adaptation mechanism characteristic of high-performance Rhodotorula species. These findings confirm that R. evergladensis CXCN-6 possesses strong metabolic flexibility and productivity, supporting its potential as a robust platform for industrial-scale bioproduction of natural antioxidants.

3.6. Stability of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts

To assess the physicochemical stability of the

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extract, particularly the robustness of torularhodin, the CXCN-6 extract was stored under different temperature and light exposure conditions. Samples were incubated at room temperature (25 °C), 37 °C, and 45 °C for over three months under both light-protected and light-exposed conditions. Remarkably, no visible color fading or pigment degradation was observed throughout the storage period (

Figure S5). The extract retained its characteristic reddish-orange hue, and absorbance spectra around 490 nm showed negligible variation, indicating excellent pigment stability.

The comparable results between light-exposed and dark-stored samples suggest that torularhodin possesses intrinsic photostability and thermal resistance, likely attributable to its extended conjugated double-bond system and terminal carboxyl functional group, which enhance molecular rigidity and oxidative resilience. This exceptional stability distinguishes torularhodin from less oxygenated carotenoids such as β-carotene, which are typically prone to photooxidation and thermal degradation. The stable coloration and spectral integrity of the CXCN-6 extract highlight its suitability for applications requiring color and oxidative stability—such as in nutraceutical, cosmetic, and food formulations.

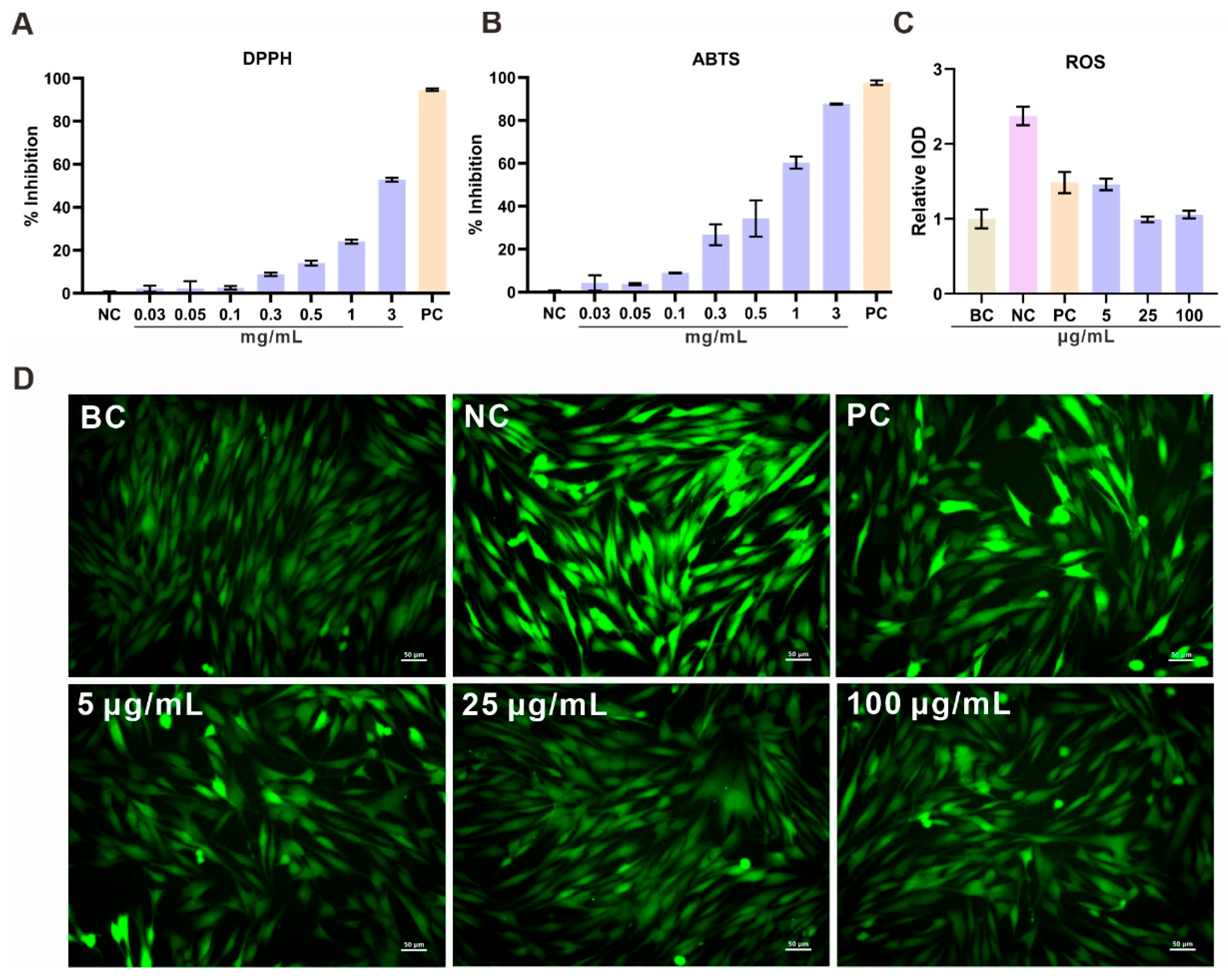

3.7. Antioxidant Activity of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts

The antioxidant potential of the CXCN-6 extract from was comprehensively evaluated using chemical radical scavenging assays (DPPH and ABTS) and a cell-based intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay (

Figure 5). Both chemical assays showed a distinct concentration-dependent response, indicating the presence of active metabolites capable of neutralizing free radicals. In the DPPH assay, the extract displayed progressive scavenging activity, reaching approximately 50% inhibition at a concentration of 3 mg/mL (

Figure 5A). Similarly, in the ABTS⁺· assay, stronger scavenging capacity was observed, with inhibition levels approaching 90% at the same concentration (

Figure 5B).

The strong antioxidant capacity of the CXCN-6 extract may be partially attributed to the presence of torularhodin and unsaturated lipid components, which are known to possess intrinsic redox-balancing properties. Torularhodin, as an oxygenated carotenoid with an extended conjugated double-bond system, has been reported to effectively scavenge reactive oxygen species [

36], while PUFAs could enhance membrane-associated oxidative defense [

37]. These findings suggest that

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 has evolved an effective biochemical defense strategy against oxidative stress, likely reflecting its adaptation to high-UV, oxygen-rich environments. Collectively, the results support CXCN-6 extract as a promising natural antioxidant resource.

To further confirm its cellular antioxidant performance, UVA-induced oxidative stress experiments were conducted in RAW264.7 macrophages using a 9 J/cm² UVA irradiation model. UVA exposure markedly increased intracellular ROS levels, as detected by the DCFH-DA fluorescent probe, indicating oxidative stress. Pre-treatment with CXCN-6 extract significantly reduced intracellular fluorescence intensity in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting effective scavenging of ROS and protection against UVA-induced oxidative injury. At 100 µg/mL, intracellular ROS generation was reduced to less than 40% of the UVA-only control, confirming potent cellular antioxidant activity (

Figure 5C,D).

These results collectively demonstrate that the R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extract possesses both chemical and cellular antioxidant capabilities. The strong scavenging effect is primarily attributed to torularhodin, a carotenoid with high singlet oxygen quenching efficiency, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which contribute to redox homeostasis and membrane stability. The synergistic action of these bioactive components likely underlies the yeast’s intrinsic oxidative stress resistance and supports its potential application in nutraceutical, cosmeceutical, and photoprotective formulations.

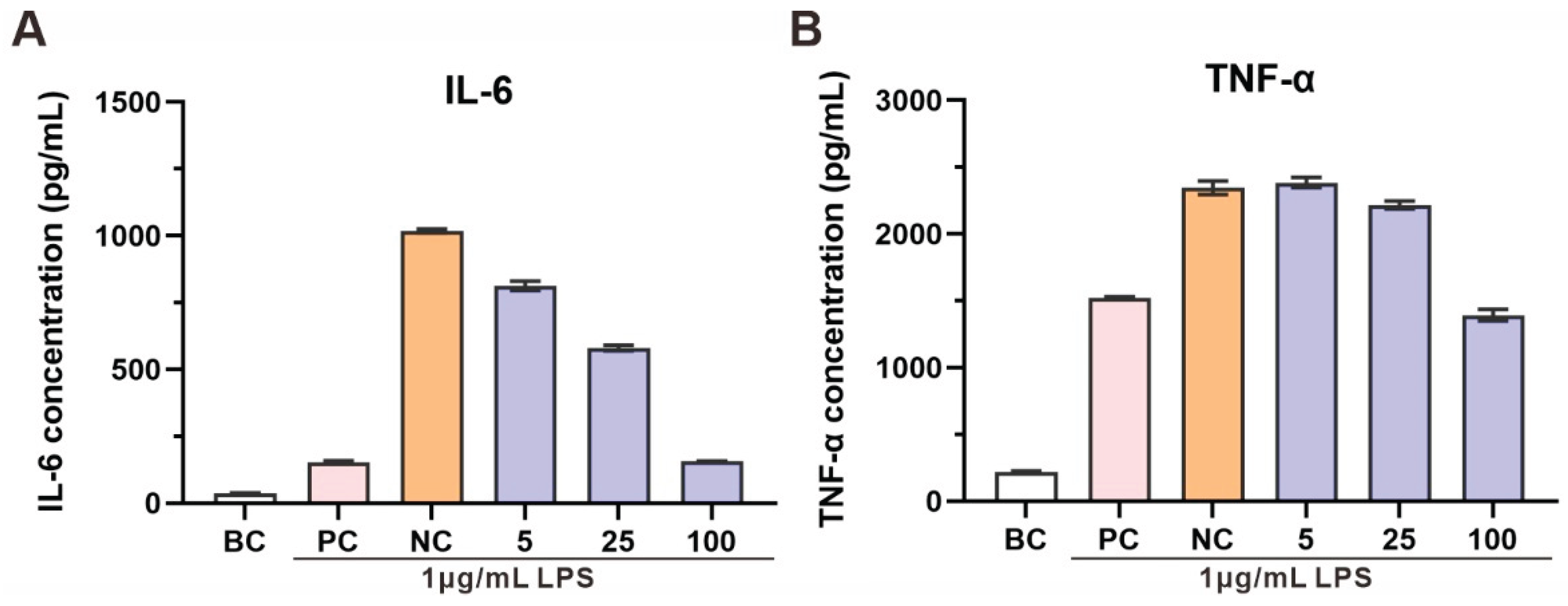

3.8. Anti-inflammatory Activity of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts

The anti-inflammatory effects of the CXCN-6 extract were subsequently examined in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages, a widely used model for evaluating inflammatory responses [

38]. Stimulation with LPS alone induced a pronounced upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), confirming macrophage activation and inflammatory signaling (

Figure 6). Co-treatment with the extract of CXCN-6 markedly and dose-dependently suppressed cytokine secretion (

Figure 6). At 100 µg/mL, IL-6 production decreased by more than 90%, while TNF-α levels were reduced by approximately 40% compared to the LPS-only control group. Importantly, cell viability assays confirmed that the extract exhibited no cytotoxic effects at all tested concentrations, indicating that the observed inhibition of cytokine release resulted from genuine anti-inflammatory action rather than cellular toxicity.

Given the strong antioxidant activity of the extract demonstrated in the UVA-induced oxidative stress model, it is plausible that the reduction of inflammatory cytokines is associated with the attenuation of oxidative stress-mediated signaling pathways. Carotenoids such as torularhodin, known for their potent singlet oxygen and free radical scavenging properties, likely play a central role in modulating intracellular redox balance. Additionally, the presence of PUFAs in the extract may further contribute to anti-inflammatory efficacy by maintaining membrane fluidity and interfering with eicosanoid biosynthesis. Collectively, these results demonstrate that R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extract exerts dual antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities at the cellular level. The coordinated suppression of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines highlights its potential as a valuable natural source for nutraceutical, cosmeceutical, and functional food applications, particularly in formulations aimed at mitigating photooxidative or inflammatory skin damage.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first functional characterization of

R.

evergladensis as a carotenoid- and lipid-producing yeast. The results demonstrate its strong capacity to synthesize torularhodin, a distinctive oxygenated carotenoid featuring an extended conjugated polyene chain and a terminal carboxyl group. Compared with β-carotene and torulene, torularhodin exhibits superior antioxidant activity and oxidative stability, enabling more effective neutralization of singlet oxygen and free radicals [

39,

40,

41]. Its dominance in CXCN-6 implies an active oxidative branch of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, promoting torulene oxidation to torularhodin as part of an adaptive defense mechanism. The genomic detection of carotenoid oxygenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase homologs further supports the presence of this oxygenation module, consistent with previous findings in

Rhodotorula glutinis and

R. mucilaginosa [

8,

42,

43].

In parallel, CXCN-6 accumulated significant amounts of PUFAs—including linoleic (C18:2), oleic (C18:1), and α-linolenic (C18:3) acids—indicative of a highly active desaturation network. Such lipid composition suggests enhanced membrane fluidity, oxidative tolerance, and adaptation to fluctuating environmental stress, properties that are advantageous for industrial biocatalysts [

44]. The coexistence of unsaturated lipid storage and carotenoid production points toward a synergistic metabolic architecture. Specifically, the lipid droplets may serve as a reservoir for hydrophobic pigments, while PUFAs help stabilize torularhodin by limiting peroxidative degradation [

45,

46]. This interplay reflects a coordinated redox homeostasis in

Rhodotorula species, where lipid and carotenoid biosynthesis are co-regulated via shared metabolic intermediates such as acetyl-CoA, NADPH, and ATP under nutrient-limited conditions [

27,

47].

The combined presence of torularhodin and PUFA-rich lipids constitutes a comprehensive antioxidative strategy. Torularhodin scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) and modulates cellular defense signaling through the inhibition of NF-κB activation, leading to a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine production [

48,

49,

50]. At the same time, the accumulation of PUFAs enhances membrane elasticity, regulates permeability, and provides resilience against lipid peroxidation under oxidative stress [

51,

52]. This dual system, involving both enzymatic and non-enzymatic defense mechanisms, likely evolved as an adaptive response to the yeast’s native environment—the exposed, high-UV, and nutrient-variable surface of Nymphaea “Gorgeous Purple” leaves in the high-altitude plateau region of Yunnan. The potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of CXCN-6 extract thus highlight its potential as a valuable bioactive ingredient for health-related industries.

The carotenoid biosynthetic capacity of

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 was notably superior to that of previously reported

Rhodotorula species (

Table 2). Under optimized fermentation conditions, CXCN-6 produced up to 63.6 mg/L of total carotenoids, of which torularhodin accounted for more than 95%. This yield is markedly higher than those documented for other

Rhodotorula yeasts, including

R. glutinis,

R. toruloides, and

R. rubra, which typically produce 1.4–35.6 mg/L under similar cultivation conditions [

46,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. The predominance of torularhodin suggests that CXCN-6 possesses a highly active oxidative branch within the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, enabling efficient conversion from torulene to torularhodin. Such enhanced oxidation capacity may be a result of environmental adaptation, as the strain was isolated from the UV-intense surface of Nymphaea “Gorgeous Purple” leaves in Yunnan. The high-level production of torularhodin therefore reflects both genetic and ecological optimization, establishing

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 as one of the most efficient natural torularhodin producers reported to date and a promising microbial platform for industrial carotenoid biosynthesis.

From a biotechnological perspective, the co-production of torularhodin and PUFA-rich lipids within a single microbial chassis offers significant process and economic benefits. The integration of pigment and lipid biosynthesis enables shared use of key precursors such as acetyl-CoA and glycerol-3-phosphate, improving carbon flux efficiency and overall metabolic economy. This intrinsic coupling enhances carbon conversion and streamlines downstream processing, as both metabolites can be co-extracted from one biomass source. Such integration is particularly attractive for large-scale fermentation, where reduced solvent use, simplified extraction, and minimized waste directly lower production costs and improve sustainability. Furthermore, embedding torularhodin within endogenous lipids enhances pigment stability, oxidative protection, and bioavailability—properties valuable for nutraceutical and cosmetic formulations. Together, these features highlight R. evergladensis CXCN-6 as a promising microbial platform for green biomanufacturing.

Future work should emphasize the genetic and metabolic elucidation of torularhodin biosynthesis through integrative multi-omics approaches—combining genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and fluxomics—to identify rate-limiting steps and key regulatory nodes linking carotenoid and lipid pathways. Engineering strategies that boost precursor supply, such as improving acetyl-CoA flux, NADPH regeneration, and oxygenase activity, could further enhance de novo synthesis of torularhodin and microbial oils [

58,

59]. In parallel, CRISPR-based editing, adaptive evolution, and dynamic regulatory tools may optimize redox balance, stress tolerance, and substrate utilization. Industrially, the use of renewable carbon sources such as lignocellulosic hydrolysates, agricultural residues, or waste glycerol can reduce costs while promoting biowaste valorization and circular bioeconomy development [

60,

61]. Through these combined advances in systems biology and process engineering,

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 holds strong potential for scalable, eco-efficient production of high-value carotenoids and functional lipids.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, R. evergladensis CXCN-6 represents a metabolically versatile yeast capable of simultaneously producing the potent antioxidant torularhodin and PUFA-enriched lipids. Its genomic features, physiological adaptability, and optimized fermentation performance collectively underscore its value as a promising microbial platform for natural pigment and lipid co-production. Through integrated process optimization, metabolic pathway elucidation, and the strategic use of renewable substrates, CXCN-6 could support eco-friendly and scalable production of carotenoids and functional oils. Beyond its industrial relevance, the strain also provides a valuable model for studying oxidative stress adaptation and secondary metabolism in non-conventional yeasts. Continued exploration of its regulatory networks and bioprocess scalability will further enhance its potential applications in nutraceutical, cosmetic, and functional food industries, advancing sustainable biomanufacturing and resource-efficient production of natural bioactives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Z.L. and J.S. H. designed the research. C.P., M.P., Y.G., and T.L. performed experiments. Z. Z., X. J., M. W. and J. C. supported the experiments. Z. L. and C.P. analyzed and interpreted the data. Z.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and contributed to the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as natural functional pigments. J Nat Med 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krinsky, N.I.; Johnson, E.J. Carotenoid actions and their relation to health and disease. Mol Aspects Med 2005, 26, 459–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frengova, G.I.; Beshkova, D.M. Carotenoids from Rhodotorula and Phaffia: yeasts of biotechnological importance. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2009, 36, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kot, A.M.; et al. Torulene and torularhodin: “new” fungal carotenoids for industry? Microb Cell Fact 2018, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moliné, M.; Libkind, D.; van Broock, M. Production of torularhodin, torulene, and β-carotene by Rhodotorula yeasts. Methods Mol Biol 2012, 898, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Libkind, D.; van Broock, M. Biomass and carotenoid pigment production by patagonian native yeasts. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2006, 22, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libkind, D.; Brizzio, S.; van Broock, M. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, a carotenoid producing yeast strain from a Patagonian high-altitude lake. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2004, 49, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; et al. Biosynthetic Pathway of Carotenoids in Rhodotorula and Strategies for Enhanced Their Production. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 29, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsenreither, K.; et al. Production Strategies and Applications of Microbial Single Cell Oils. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringel, M.; et al. Sustainable Lipid Production with Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus: Insights into Metabolism, Feedstock Valorization and Bioprocess Development. 2025, 13, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageitos, J.M.; et al. Oily yeasts as oleaginous cell factories. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 90, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitepu, I.R.; et al. Oleaginous yeasts for biodiesel: current and future trends in biology and production. Biotechnol Adv 2014, 32, 1336–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budilarto, E.S.; Kamal-Eldin, A. The supramolecular chemistry of lipid oxidation and antioxidation in bulk oils. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2015, 117, 1095–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonlao, N.; Ruktanonchai, U.R.; Anal, A.K. Enhancing bioaccessibility and bioavailability of carotenoids using emulsion-based delivery systems. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereti, F.; et al. Green extraction of carotenoids and oil produced by Rhodosporidium paludigenum using supercritical CO2 extraction: Evaluation of cell disruption methods and extraction kinetics. Food Chemistry 2025, 483, 144261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagy, C.U.; et al. Selective recovery and purification of carotenoids and fatty acids from Rhodotorula glutinis using mixtures of biosolvents. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 266, 118548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, P.; Barakova, N.V.; Krivoshapkina, E.F. Selected Methods of Extracting Carotenoids, Characterization, and Health Concerns: A Review. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 5925–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, G.; et al. Enhanced biomass and lipid production by light exposure with mixed culture of Rhodotorula glutinis and Chlorella vulgaris using acetate as sole carbon source. Bioresource Technology 2022, 364, 128139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; et al. Engineered microbial production of carotenoids and their cleavage products: Recent advances and prospects. Biotechnol Adv 2025, 85, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Gómez, L.C.; et al. Biotechnological production of carotenoids by yeasts: an overview. Microb Cell Fact 2014, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Kumar, P.; Kataria, R. Microbial carotenoid production and their potential applications as antioxidants: A current update. Process Biochemistry 2023, 128, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R.S.K.; et al. Exploration of carotenoid-producing Rhodotorula yeasts from amazonian substrates for sustainable biotechnology applications. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2025, 8, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, A.M.; et al. Rhodotorula glutinis-potential source of lipids, carotenoids, and enzymes for use in industries. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 6103–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.K.; Nicaud, J.M.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. The Engineering Potential of Rhodosporidium toruloides as a Workhorse for Biotechnological Applications. Trends Biotechnol 2018, 36, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; et al. MEGA: A biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfeky, N.; et al. Lipid and Carotenoid Production by Rhodotorula glutinis with a Combined Cultivation Mode of Nitrogen, Sulfur, and Aluminium Stress. 2019. 9 2444. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; et al. Rapid quantification of microalgal lipids in aqueous medium by a simple colorimetric method. Bioresource Technology 2014, 155, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant Determinations by the Use of a Stable Free Radical. Nature 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-J.; et al. Whole genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis of oleaginous red yeast Sporobolomyces pararoseus NGR identifies candidate genes for biotechnological potential and ballistospores-shooting. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, A.M.; et al. Effect of exogenous stress factors on the biosynthesis of carotenoids and lipids by Rhodotorula yeast strains in media containing agro-industrial waste. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 35, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda-Martínez, E.; et al. In Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, active oxidative metabolism increases carotenoids to inactivate excess reactive oxygen species. Front Fungal Biol 2024, 5, 1378590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.-T.; et al. Developing Rhodotorula as microbial cell factories for the production of lipids and carotenoids. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; et al. Lipids detection and quantification in oleaginous microorganisms: an overview of the current state of the art. BMC Chemical Engineering 2019, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufka, J.; et al. Exploring carotenoids: Metabolism, antioxidants, and impacts on human health. Journal of Functional Foods 2024, 118, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid status and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation across the lifespan: A cross-sectional study in a cohort with long-lived individuals. Experimental Gerontology 2024, 195, 112531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; et al. Engineering a manganese superoxide dismutase with enhanced thermostability and activity via protein language Models: Toward antioxidant and anti-inflammatory applications in biomedicine and skincare. Free Radic Biol Med 2025, 239, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, S.; et al. Production kinetics and characterization of natural food color (torularhodin) with antimicrobial potential. Bioresource Technology Reports 2023, 24, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; et al. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa-alternative sources of natural carotenoids, lipids, and enzymes for industrial use. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Viñals, N.; et al. Current Advances in Carotenoid Production by Rhodotorula sp. 2024, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperstad, S.; et al. Torularhodin and torulene are the major contributors to the carotenoid pool of marine Rhodosporidium babjevae (Golubev). J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2006, 33, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoz, L.; et al. Torularhodin and torulene: bioproduction, properties and prospective applications in food and cosmetics-a review. 2015, 58, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Fani, A.; et al. Chapter 20 - Aspects of food structure in digestion and bioavailability of LCn-3PUFA-rich lipids, in Omega-3 Delivery Systems, P.J. García-Moreno; et al. Editors. 2021, Academic Press. p. 427-448.

- Danielli, M.; et al. Lipid droplets and polyunsaturated fatty acid trafficking: Balancing life and death. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkáčová, J.; et al. Correlation between lipid and carotenoid synthesis in torularhodin-producing Rhodotorula glutinis. Annals of Microbiology 2017, 67, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tan, T. Lipid and carotenoid production by Rhodotorula glutinis under irradiation/high-temperature and dark/low-temperature cultivation. Bioresource Technology 2014, 157, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; et al. Torularhodin Ameliorates Oxidative Activity in Vitro and d-Galactose-Induced Liver Injury via the Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway in Vivo. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2019, 67, 10059–10068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; et al. Microorganisms: A Potential Source of Bioactive Molecules for Antioxidant Applications. 2021. 26 1142. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; et al. Torularhodin from Sporidiobolus pararoseus Attenuates d-galactose/AlCl3-Induced Cognitive Impairment, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation via the Nrf2/NF-κB Pathway. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2020, 68, 6604–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firsov, A.M.; et al. Deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids inhibit photoirradiation-induced lipid peroxidation in lipid bilayers. J Photochem Photobiol B 2022, 229, 112425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho, C.C.C.R.; Caramujo, M.J. The Various Roles of Fatty Acids. 2018, 23, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varmira, K.; et al. Statistical optimization of airlift photobioreactor for high concentration production of torularhodin pigment. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2016, 8, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, H.; et al. Activation of torularhodin production by Rhodotorula glutinis using weak white light irradiation. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2001, 92, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, R.; et al. Enhancement of Torularhodin Production in Rhodosporidium toruloides by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-Mediated Transformation and Culture Condition Optimization. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; et al. Metabolomic profiling of Rhodosporidium toruloides grown on glycerol for carotenoid production during different growth phases. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 10203–10209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; et al. Lipid and carotenoid production by the Rhodosporidium toruloides mutant in cane molasses. Bioresour Technol 2021, 326, 124816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; et al. Strategies for optimizing acetyl-CoA formation from glucose in bacteria. Trends in Biotechnology 2022, 40, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; et al. Advances and trends for astaxanthin synthesis in Phaffia rhodozyma. Microb Cell Fact 2025, 24, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; et al. Lignocellulosic biomass as promising substrate for polyhydroxyalkanoate production: Advances and perspectives. Biotechnology Advances 2025, 79, 108512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulis, D.B.; et al. Advances in lignocellulosic feedstocks for bioenergy and bioproducts. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Workflow of isolation, characterization, and bioactivity evaluation of R. evergladensis CXCN-6. This schematic summary illustrates the experimental workflow of the study. (1) A pigmented yeast strain, R. evergladensis CXCN-6, was isolated from the surface of Nymphaea “Gorgeous Purple” leaves exposed to intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation in plateau environment. (2) The strain was taxonomically identified based on ITS rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. (3) Intracellular bioactive compounds, including the carotenoid torularhodin and storage lipids, were extracted from cultured biomass. (4) The chemical composition and structure of the metabolites were characterized using HPLC and LC–MS analyses. (5) The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the CXCN-6 extracts were subsequently evaluated through biochemical assays and cell-based functional experiments, confirming their potent ROS-scavenging and cytoprotective effects.

Figure 1.

Workflow of isolation, characterization, and bioactivity evaluation of R. evergladensis CXCN-6. This schematic summary illustrates the experimental workflow of the study. (1) A pigmented yeast strain, R. evergladensis CXCN-6, was isolated from the surface of Nymphaea “Gorgeous Purple” leaves exposed to intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation in plateau environment. (2) The strain was taxonomically identified based on ITS rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. (3) Intracellular bioactive compounds, including the carotenoid torularhodin and storage lipids, were extracted from cultured biomass. (4) The chemical composition and structure of the metabolites were characterized using HPLC and LC–MS analyses. (5) The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the CXCN-6 extracts were subsequently evaluated through biochemical assays and cell-based functional experiments, confirming their potent ROS-scavenging and cytoprotective effects.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 based on ITS rDNA sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replications in MEGA 7. The ITS sequence of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 was aligned with representative sequences of closely related Rhodotorula species retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database. Bootstrap values (%) are indicated at the nodes. Cryptococcus neoformans was used as the outgroup to root the tree. The clustering pattern clearly places strain CXCN-6 within the R. evergladensis clade, confirming its taxonomic identity.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 based on ITS rDNA sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replications in MEGA 7. The ITS sequence of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 was aligned with representative sequences of closely related Rhodotorula species retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database. Bootstrap values (%) are indicated at the nodes. Cryptococcus neoformans was used as the outgroup to root the tree. The clustering pattern clearly places strain CXCN-6 within the R. evergladensis clade, confirming its taxonomic identity.

Figure 3.

Overview of metabolic pathways for torularhodin and unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in R. evergladensis CXCN-6. This schematic illustrates the central carbon metabolism and its branching into carotenoid and lipid biosynthetic routes. Glucose enters the glycolytic (EMP) and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) pathways to generate acetyl-CoA, a key metabolic precursor. Acetyl-CoA serves as the starting substrate for both the mevalonate pathway—leading to isoprenoid intermediates (IPP, FPP, GGPP) and downstream carotenoids including phytoene, lycopene, β-carotene, torulene, and torularhodin—and the fatty acid synthesis pathway generating long-chain and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Enzymes and intermediates involved in the metabolic pathways are highlighted in red. The interconnection between torularhodin and PUFA production reflects shared carbon flux and redox cofactor balance, forming the biochemical basis for co-production of pigments and lipids in R. evergladensis CXCN-6.

Figure 3.

Overview of metabolic pathways for torularhodin and unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in R. evergladensis CXCN-6. This schematic illustrates the central carbon metabolism and its branching into carotenoid and lipid biosynthetic routes. Glucose enters the glycolytic (EMP) and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) pathways to generate acetyl-CoA, a key metabolic precursor. Acetyl-CoA serves as the starting substrate for both the mevalonate pathway—leading to isoprenoid intermediates (IPP, FPP, GGPP) and downstream carotenoids including phytoene, lycopene, β-carotene, torulene, and torularhodin—and the fatty acid synthesis pathway generating long-chain and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Enzymes and intermediates involved in the metabolic pathways are highlighted in red. The interconnection between torularhodin and PUFA production reflects shared carbon flux and redox cofactor balance, forming the biochemical basis for co-production of pigments and lipids in R. evergladensis CXCN-6.

Figure 4.

Carotenoid and lipid profile analysis of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extract. (A) HPLC chromatogram (C18 reverse-phase column, detection at 490 nm) displaying the dominant torularhodin peak (retention time identical to the authentic standard). (B) LC–MS analysis (APCI⁺ mode) confirming torularhodin as the predominant carotenoid with a molecular ion peak at m/z 563.4 [M]⁺, consistent with its theoretical molecular weight (C₄₀H₅₆O₂). (C) LC–MS chromatogram of fatty acid methyl esters extracted from CXCN-6 lipids, revealing a fatty acid profile dominated by linoleic (C18:2), oleic (C18:1), and α-linolenic (C18:3) acids, with palmitic acid (C16:0) as the main saturated component. (D) Time-course of carotenoid production (torularhodin and β-carotene) during 5-L fermentation of R. evergladensis CXCN-6. (E) Time-course of dry cell weight (DCW) and total lipid accumulation during fermentation. DCW increased rapidly during the growth phase and reached a plateau in the late stage, while lipid titers increased markedly in the late phase, reaching ~9.83 g/L at 72 h.

Figure 4.

Carotenoid and lipid profile analysis of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 extract. (A) HPLC chromatogram (C18 reverse-phase column, detection at 490 nm) displaying the dominant torularhodin peak (retention time identical to the authentic standard). (B) LC–MS analysis (APCI⁺ mode) confirming torularhodin as the predominant carotenoid with a molecular ion peak at m/z 563.4 [M]⁺, consistent with its theoretical molecular weight (C₄₀H₅₆O₂). (C) LC–MS chromatogram of fatty acid methyl esters extracted from CXCN-6 lipids, revealing a fatty acid profile dominated by linoleic (C18:2), oleic (C18:1), and α-linolenic (C18:3) acids, with palmitic acid (C16:0) as the main saturated component. (D) Time-course of carotenoid production (torularhodin and β-carotene) during 5-L fermentation of R. evergladensis CXCN-6. (E) Time-course of dry cell weight (DCW) and total lipid accumulation during fermentation. DCW increased rapidly during the growth phase and reached a plateau in the late stage, while lipid titers increased markedly in the late phase, reaching ~9.83 g/L at 72 h.

Figure 5.

Antioxidant Activity of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts. (A) DPPH radical scavenging activity of CXCN-6 extract at concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 3 mg/mL. The scavenging rate increased in a dose-dependent manner, reaching approximately 50% at 3 mg/mL. (B) ABTS⁺· radical scavenging activity of the extract under the same concentration range, showing a stronger response with ~90% inhibition at 3 mg/mL. (C) Intracellular ROS quantification in UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells (9 J/cm²). Cells pretreated with CXCN-6 extract (5–100 μg/mL) displayed significant, concentration-dependent ROS suppression relative to the UVA-only group (n = 3, p < 0.05). Vitamin C (100 μg/mL) and Vitamin E (7 μg/mL) mixture was used as a positive control. (D) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of DCF-DA-stained HaCaT cells. The intense green fluorescence induced by UVA exposure was markedly reduced following extract treatment, indicating intracellular ROS scavenging. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 5.

Antioxidant Activity of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts. (A) DPPH radical scavenging activity of CXCN-6 extract at concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 3 mg/mL. The scavenging rate increased in a dose-dependent manner, reaching approximately 50% at 3 mg/mL. (B) ABTS⁺· radical scavenging activity of the extract under the same concentration range, showing a stronger response with ~90% inhibition at 3 mg/mL. (C) Intracellular ROS quantification in UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells (9 J/cm²). Cells pretreated with CXCN-6 extract (5–100 μg/mL) displayed significant, concentration-dependent ROS suppression relative to the UVA-only group (n = 3, p < 0.05). Vitamin C (100 μg/mL) and Vitamin E (7 μg/mL) mixture was used as a positive control. (D) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of DCF-DA-stained HaCaT cells. The intense green fluorescence induced by UVA exposure was markedly reduced following extract treatment, indicating intracellular ROS scavenging. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Anti-inflammatory Activity of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts. (A) Effect of CXCN-6 extract on interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. LPS treatment markedly increased IL-6 release, whereas co-treatment with the extract (25–100 µg/mL) significantly suppressed cytokine production in a concentration-dependent manner (p < 0.05). (B) Effect of CXCN-6 extract on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) secretion under the same conditions. The extract reduced TNF-α levels by approximately 40% at 100 µg/mL. Vitamin C was used as a positive control. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); asterisks indicate significant differences compared with the LPS group (p < 0.05, *p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

Anti-inflammatory Activity of R. evergladensis CXCN-6 Extracts. (A) Effect of CXCN-6 extract on interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. LPS treatment markedly increased IL-6 release, whereas co-treatment with the extract (25–100 µg/mL) significantly suppressed cytokine production in a concentration-dependent manner (p < 0.05). (B) Effect of CXCN-6 extract on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) secretion under the same conditions. The extract reduced TNF-α levels by approximately 40% at 100 µg/mL. Vitamin C was used as a positive control. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); asterisks indicate significant differences compared with the LPS group (p < 0.05, *p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Comparison of lipid and carotenoid production in R. evergladensis CXCN-6 before and after fermentation optimization.

Table 1.

Comparison of lipid and carotenoid production in R. evergladensis CXCN-6 before and after fermentation optimization.

| CXCN-6 Extract |

Production (mg/L) |

Production/DCW (mg/g) |

| Before optimization |

After optimization |

Before optimization |

After optimization |

| DCW |

20 |

50 |

/ |

/ |

| Total lipids |

733.3 |

7126.7 |

36.7 |

142.5 |

| Torularhodin |

15.3 |

63.6 |

0.77 |

1.3 |

| β-Carotene |

1.8 |

2.9 |

0.08989 |

0.058 |

Table 2.

Comparison of torularhodin production by R. evergladensis CXCN-6 with other Rhodotorula species under various culture conditions.

Table 2.

Comparison of torularhodin production by R. evergladensis CXCN-6 with other Rhodotorula species under various culture conditions.

| Yeast strain |

Carbon source |

Nitrogen source |

Torularhodin |

β-Carotene |

Reference |

|

R. evergladensis CXCN-6 |

Glucose |

Yeast extract, Peptone |

63.6 mg/L |

2.9 mg/L |

This study |

|

R. rubra PTCC 5255 |

Glucose |

Ammonium sulfate |

35.6 mg/L |

1.0 mg/L |

[53] |

|

R. glutinis JMT 21978 |

Glucose |

Yeast extract |

6.6 mg/L |

2.0 mg/L |

[46] |

|

R. glutinis ZHK |

Dextrose |

Yeast extract, Peptone |

1.4 mg/L |

1.7 mg/L |

[54] |

|

R. toruloides A1-15-BRQ |

Glucose |

Ammonium sulfate |

21.3 mg/L |

1.2 mg/L |

[55] |

|

R. toruloides CBS 5490 |

Glycerol |

Yeast extract, Peptone |

19.7 mg/L |

6.8 mg/L |

[56] |

|

R. toruloides M18 |

Glucose |

Yeast extract, Peptone |

8.95 mg/L |

285.5 mg/L |

[57] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).